Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is significantly impacting human lives, overburdening the healthcare system and weakening global economies. Plant-derived natural compounds are being largely tested for their efficacy against COVID-19 targets to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection. The SARS-CoV-2 Main protease (Mpro) is considered an appealing target because of its role in replication in host cells. We curated a set of 7809 natural compounds by combining the collections of five databases viz Dr Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical database, IMPPAT, PhytoHub, AromaDb and Zinc. We applied a rigorous computational approach to identify lead molecules from our curated compound set using docking, dynamic simulations, the free energy of binding and DFT calculations. Theaflavin and ginkgetin have emerged as better molecules with a similar inhibition profile in both SARS-CoV-2 and Omicron variants.

Keywords: Main proteases (Mpro), DFT calculation, Dynamics simulation, Binding free energy, Omicron

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The beginning of 2020 took the planet to a virtual impasse with the outbreak of a novel Severe Acute Respiratory Virus Syndrome-Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID 2019) pandemic began in Wuhan province, China, in 2019 and has resulted in unprecedented human deaths worldwide [2]. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) recognized this virus as SARS-CoV-2 on 11th March 2020 due to genetic relation to SARS-CoV infection reported in the year 2003 [1,3]. The first SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan Hu-1 strain evolved genetically [4] during worldwide spread leading to five different variants such as B.1.1.7 (Alpha) detected in the United Kingdom (September 2020), B.1.351 (Beta) in South Africa (May 2020), P.1 (Gamma) in Brazil (November 2020), B.1.617.2 (Delta) in India (October 2020) and B.1.1.529 (Omicron) in South Africa (November 2021) [5]. The COVID virus majorly affects the respiratory system with mild to severe symptoms including watery nose, persistent cough, sore throat, loss of smell or taste, frequently with fever and body pain [2,6,7]. Although antiviral medications (e.g., nirmatrelvir, ritonavir) [8] are being prescribed to alleviate the symptoms, the current practices suggest that vaccine administration boosts the immune system to develop antibodies curbing the COVID infection [2,6,7]. However, the side effects and other related ailments associated with the COVID vaccines are largely unknown and necessitate the pursuit of new antivirals [9].

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are enveloped and positive-stranded RNA viruses belonging to the Coronaviridae family and are categorized into seven major classes based on their genome sequences and serological reactions [10]. This include 229E (Alpha coronavirus), NL63 (Alpha coronavirus), OC43 (Beta coronavirus), HKU1 (Beta coronavirus), MERS-CoV (Beta coronavirus, the causative agent of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, MERS), SARS-CoV (the Beta coronavirus, the agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome, SARS) and SARS-CoV-2 (the novel coronavirus responsible for COVID-19) [11]. Certain CoVs can infect humans (e.g., damage to lungs, difficulty breathing, recurrent fevers, weariness, sadness, anxiety, and chronic memory and attention impairment) while others are only capable of infecting animals (e.g., respiratory tract and olfactory epithelium damage in golden hamster) [12]. Initial reports suggest that bat is the primary host of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in humans while pangolin is an intermediary host [13]. These reports are getting challenged based on emerging pieces of evidence on the genetic and evolutionary relationships among the human, bat and pangolin coronaviruses [14].

In the current situation, it has become necessary to monitor and ultimately eradicate this deadly disease by using an effective vaccine. Several vaccines are available on the market, but it contains some side effects; hence there is a dire need to combat this coronavirus with potential drug or natural inhibitors. CoV infection can be controlled by masking the virus entry into the host cells through the invention of inhibitors protecting the replication and transcription of the virus [15,16]. SARS-CoV-2 encodes both structural and non-structural proteins (NSPs). The structural proteins include envelope (small) membrane protein (E protein), membrane protein (M protein), nucleocapsid protein (N protein) and spike protein (S protein). Some proteases such as main protease (Mpro, NSP5) and Papain-like protease (PLpro, NSP3) are also present [16,17]. A series of NSPs facilitate crucial functions essential for replication, survival and virulence [18]. These include NSP13 (helicase), NSP12 (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, RdRp), NSP14 (N-terminal exoribonuclease and C-terminal guanine-N7 methyltransferase), NSP15 (uridylate-specific endoribonuclease), NSP16 (2′-O-methyltransferase) among others [19].

An ideal strategy to develop drugs for treating COVID-19 is targeting the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro protein that plays a prominent role in viral replication and transcription in host cells [6,20]. Inhibition of Mpro protein is actively pursued in the research community by leveraging the techniques of structure-based drug design and partially due to the absence of human homologs that may constitute a high rate of therapeutic efficacy [16]. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is a cysteine protease (EC 3.4.22.69) belonging to the PA protease clan family. Jin et al., released the first crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (resolution, 2.16 Å) in the Protein Data Bank (PDB, entry: 6LU7) on 5th February 2020 [20]. The functional form of Mpro is a dimer (∼33 kDa), and each monomer (306 amino acid residues) consists of three domains (I to III; domain I - residues 8 to 101, II – 102 to 184, and III – 201 to 303) [16,21]. The active site of Mpro is situated between domains I and II and carry out proteolytic function using the Cys-His catalytic dyad [16]. Both domains I and II are composed of antiparallel β-barrels, and domain III consists of five α-helical strands. The residue Glu166 is responsible for bringing the active site close to the dimer interface that promotes the access of the S1 subsite necessary for ligand binding. Mutation of this residue results in the loss of substrate-induced dimerization [22]. The presence of an oxyanion hole, which is composed of residues Gly143, Ser144, and Cys145, is also notable in stabilizing the transition state during catalysis by protecting the negative charge on the ligand's proximal oxygen atom and enabling hydrogen bond. The active site of Mpro is encompassed by the following residues, Ser46, Gln189, Thr190, Ala191, Pro168, Glu166, Leu141, and Asn142 in addition to the catalytic dyad (Cys145, His41) [16,21].

On 24 November 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized Omicron as a new SARS-CoV-2 variant (B.1.1.529) of severe concern and highly contagious compared to the Delta variant but possesses relatively less severity [23,24]. Despite increased surveillance and vaccination drive, Omicron has spread to 108 nations. A large-scale study is necessary to investigate vaccine-induced immunity after booster administration and adaptation of acquired immunity in Human subjects to circumvent the Omicron variant [25,26]. Researchers obtained the three-dimensional structure of Omicron Mpro harbouring a single mutation P132H to its SARS-CoV-2 counterpart and reported similar catalytic efficiency of antivirals such as GC-376, PF-07321332 (nirmatrelvir), and PF-00835231 [27,28].

Plants have been the primary source of medication since ancient times due to their therapeutic potential and low toxicity. This allowed researchers to use them as initial lead molecules for the drug discovery and development process. Several studies have previously shown that plant-based research might be an effective strategy to identify better leads for COVID-19 medication development [29]. Kumar et al., 2021 tested natural metabolites against COVID-19 Mpro [30]. Pandey et al., 2020 used phytochemicals to target molecules against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. To promote such lead compounds to the pre-clinical stage of drug development, they must be toxic free and thereby selecting a library of natural compounds for such assessment is critical [31]. We selected 7809 natural compounds from Zinc [32], IMPPAT [33], PhytoHub [34], AromaDb [35] and Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical databases [36] with emphasis on physicochemical properties, drug performance rates, targeted proteins, business providers and drug similarity profile. In this study, we used an integrative workflow comprising structure-based virtual screening, DFT calculations, dynamic simulations, and binding free energy calculations to find Mpro inhibitors from our compiled library of natural compounds.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ligand selection

A total of 7809 natural compounds were chosen based on drug-like properties through Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical database, IMPPAT, PhytoHub, AromaDb and Zinc databases. These compounds have favourable ADMET characteristics. The three-dimensional

Structures were extracted in sdf format and polar hydrogen atoms were added. We carried out stereochemistry checks and energy was minimized using the Amber 03 forcefield using 1000 steps of the steepest descent technique with no convergence. The minimized molecules were then saved in.sdf format convenient for further calculations in the YASARA software (academic license) [[37], [38], [39]] [[37], [38], [39]] [[37], [38], [39]].

2.2. Protein selection

The crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 and Omicron Mpro in complex with inhibitors (N3, oxazole-pyrrolidine molecule, resolution 2.16 Å) and K36 (pyrrolidine-sulfonic acid molecule, 2.05 Å) were retrieved from PDB with the entries 6LU7 [16] and 7TOB [40], respectively. Structure files were prepared using the “Clean” module of YASARA Structure (version 19.12.14) which included removing crystallographic waters, atom typing with the Amber03 force field, adding polar hydrogens, assigning charges to titratable amino acids before, and carried out geometry optimization with the steepest gradient approach (100 iterations) [37,41].

2.3. Virtual screening of natural compounds

YASARA Structure (version 19.12.14) was used to perform the virtual screening exercise. The ligand binding site in Mpro proteins was selected based on the location of crystallized ligands (N3 and K36) coordinates. Initially, the coordinates of the crystallized ligand were obtained from PDB, prepared using the “Clean” module of YASARA suite and atom-typed using AMBER03 force field and subsequently redocked to its native position. The prepared 7809 natural compounds were docked into the Mpro active site (20 × 20 × 20 Å grid box size) using the AutoDock Vina technique for pose search, and the AMBER03 force field. Was used to enumerate protein-ligand interactions [42]. Finally, a short energy-minimization step was pursued as a measure of post-docking refinement of docking solutions. Conjugate gradient-based energy minimization was carried out with 100 iterations with no restraint on heavy atoms to ensure the generation of optimal bonds and orders in the docked pose. The YASARA empirical energy function engineered in the YASARA Structure suite was used to score the best poses. A large positive value suggests strong binding of the ligand to its target receptor, which is in direct contrast to conventional scoring functions with negative energy implying better ligand binding [43]. The AMBER3 force field enumerates the intermolecular interactions between the sum of potential energy and solvation energy terms in the free state (receptor and ligand in isolation) and the sum of the same set of energy terms in the complex state (ligand-bound receptor conformation). The top-ranked natural compounds were visualized using ACCELRYS Discovery Studio (DS) visualizer (freeware for academic usage) and analyzed various intermolecular bond formations such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions [44]. The compounds with the highest binding energy with better receptor interactions were selected for further study using the molecular dynamics approach [45]. The following empirical equation was used to calculate the binding free energy ΔG bind:

| ΔG = ΔGvdW+ ΔGHbond+ ΔGelec+ ΔGtor+ ΔGdesol | (1) |

Where ΔG vdW = van der Waals term for docking energy; ΔG Hbond = H bonding term for docking energy; ΔG elec = electrostatic term for docking energy; ΔG tor = torsional free energy term for the compound when the compound transits from unbounded to bounded state; ΔG desol = desolvation term for docking energy.

2.4. Density functional theory calculation of top-scoring molecules

The Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations for the optimization of N3, K36 and best natural hits were performed using Becke's three-parameter hybrid exchange (B3LYP) in the Gaussian 09 (G09 B.01) software package (academic license) [[46], [47], [48], [49]]. The 6–311 g++(d,p) basis set was employed for all compounds. Global electronic descriptors such as softness (S) [50], hardness (η) [[51], [52], [53]], and chemical potential (μ) for selectivity and reactivity of the DFT concept were studied. Further, Frontier molecular orbital (FMOs) difference i.e., the energy difference between Highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) was also calculated [50,54,55]. The B3LYP method with 6–311 g++(d,p)basis sets was used to visualize the HOMO and LUMO profiles. The optimized structure and HOMO-LUMO difference were visualized using GaussView (G09 B.01) software package (academic license). The stability [56], softness (S), hardness (η) and chemical potential (μ) were calculated using the bandgap energy (Eg) as below.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

The maximum hardness principle (MHP) states that the systems in their ground or valence states will tend to arrange themselves to be as hard as possible. The global index is the electrophilicity index (ω), an important term for energy reduction due to the maximum current of the electron between donor and acceptor.

| (6) |

The stabilization energy () calculated as follow.

| (7) |

2.5. Molecular dynamics simulation of top-scoring molecules

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed to evaluate the stability of the Mpro-ligand complexes and the binding ability of ligands [57]. This computational technique, in addition to molecular docking, enabled the study of large conformational shifts as well as the stabilization of protein-ligand complexes [58,59]. The Desmond (Schrödinger, LLC, NY, USA) package was used to run MD simulations [60]. A total of 7 MD simulations were performed with the following molecular configurations, re-docked (N3)-6LU7, theaflavin-6LU7, ginkgetin-6LU7, re-docked (K36)-7TOB, theaflavin-7TOB, and ginkgetin-7TOB for 1 μs time interval each. These ligand-bound Mpro structures were analyzed using the Minimization panel of Desmond to identify the most accurate and energy-minimized structure for MD simulations. The AMBER05 force field with TIP3P (Transferable Intermolecular Potential with 3 Points) solvent model was used with a hybrid approach of steepest descent (100 steps) and L-BFGS (Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno) approaches. Structures that secured energy differences less than 0.1 kcal/mol were retained and subjected as the starting input to MD simulations. Further, the apo-Mpro protein was subjected to MD simulations to account for the comparative analysis of ligand-bound changes. Both receptor-ligand complexes were again prepared using Protein Preparation Wizard for compliance in the Schrodinger's Maestro workspace with default settings and not altering the ligand pose conformation. The periodic simulation box was built with the System Builder module and dissolved with TIP3P water model [61]. The Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations (OPLS) all-atom force field 2005 [62] was employed to apply bonded and non-bonded constraints and neutralized them by adding counter ions and energy minimization with the steepest descent technique (1000 iterations). After reaching equilibrium, an unrestrained protocol was enabled in the NPT ensemble for 1 μs at 300 K and 1.01325 bar (atoms, pressure, and temperature were kept constant). The isotropic Martyna-Tobias-Klein barostat (relaxation time = 2 ps) [63] and the Nosé-Hoover thermostat (relaxation time = 1 ps) were used. The smooth particle mesh Ewald (PME) [64] system with a smooth particle network with the RESPA integrator [65] was used to measure short-range interactions (cut-off = 9 Å) and long-range Coulomb interactions. At an interval of 5 ps, frames were captured to build the simulation trajectory. The system's stability was assessed using various plots for root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), hydrogen bond analysis, radius of gyration (Rg), and torsional bonds [66].

2.6. Binding free energy calculations of top-scoring molecules

The binding free energy of the top-scoring molecules in complex with the target proteins was calculated using the MM/GBSA (molecular mechanics (MM) with generalized Born and surface area continuum solvation (GBSA) with the single trajectory (a trajectory containing single protein-ligand complex) approach [67,68]. The combination of the MM technique with implicit solvation models provides a most accurate ranking of ligands than empirical scoring schemes used in the docking exercise above and is more computationally efficient than rigorous alchemical perturbation methods. The binding free energy (ΔG bind) is composed of three terms, i.e. MM energy term (ΔE MM) is a combination of three different interaction energy terms such as internal energy of the molecular system studied in terms of bond, angle and dihedral energies (ΔE internal), electrostatic (ΔE electrostatic) and van der Waals (ΔE vdw), ii. Solvation energy (ΔG solv) composed of polar (ΔG GB) and non-polar terms (ΔG SA), and iii. Entropy term (-TΔS), a conformation entropy term accounting for the loss of entropy when a ligand in a free state binds to a free state of the target receptor [69]. Although Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) methods are more accurate than GB, the Prime module of the Schrödinger suite features a thorough analysis of the optimized implicit solvent energy terms and physics-based corrected terms for H-bonding, hydrophobic interactions, intramolecular interaction among others in the VSGB 2.0 model [[69], [70], [71]] [[69], [70], [71]] [[69], [70], [71]]. The MM/GBSA calculations were performed upon the 1 μs long MD simulation trajectory obtained for the top-scoring molecules in complex with the target receptors at a frame step size of 10. The following equations (8), (9), (10), (11) were used to quantify the ligand-binding free energy values:

| ΔGbind= Gcomplex– (Greceptor+ ΔGligand) | (8) |

| ΔGbind= ΔH – TΔS ≈ ΔEMM+ ΔGsol– TΔS | (9) |

| ΔEMM= ΔEinternal+ ΔEelectrostatic+ ΔEvdw | (10) |

| ΔGsol= ΔGPB/GB + ΔGSA | (11) |

3. Results

3.1. Virtual screening of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro target

The best natural compounds with the potential to inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro were identified through a virtual screening technique using the YASARA Structure suite. First, the docking accuracy was evaluated by re-docking the two co-crystal ligands N3 (PDB entry: 6LU7) and K36 (7TOB) into their ligand-binding site and measuring the RMSD between the native and docked conformations. The close placement of the redocked ligand to its native positions demonstrated that the dimensions (20 × 20 × 20 Å; 0.375 Å spacing) of the grid box built upon the Mpro targets were sufficient to dock native-like ligands from the compiled natural compound dataset. In addition, the constitution of the catalytic dyad (Cys145 and His41) along with crucial polar and hydrophobic pocket-lining residues within the docking grid confirmed that the intermolecular interactions secured by natural compounds with these Mpro residues will highlight inhibitory functions. After the generation of docking solutions, a post-docking refinement process with a conjugate gradient approach (100 steps) was adopted to generate physically relevant docking conformations. Figure. 1 depicts the dock pose of co-crystallized ligand N3 and 6LU7 protein. The best dock pose with 7.55 kcal/mol binding energy was identified which showed an RMSD of 1.70 Å. The re-docked pose of N3 comprised of 7 H-bonds (with Gly 143, Phe140, His163, His164, Glu166 and Thr190), 1 amide π-stacked (Leu141), 5 π-alkyl (His41, Met49, Leu167, Pro168, and Ala191) contacts, 2 carbon-hydrogen bonds (Met165 and His172), and 1 van der Waals (with Asn142) (Figure. 1). Most of the intermolecular contacts were noted as in crystal pose demonstrating the ability to generate similar interaction profiles with new molecules. The docking validation of Omicron variant Mpro showed that K36 obtained close to near-native pose with a binding energy of 7.80 kcal/mol with an RMSD of 0.32 Å (Table-1 ). The re-docked pose of K36 contained 4 hydrogen bonds with Phe140, His164 and Glu166 and a single covalent bond with Cys145. There were 5 carbon-hydrogen bonds with His164, Met165 and His72, and a single unfavourable donor-donor bond with Gln189 due to steric hindrance, 1 alkyl and 1 π-alkyl bond with His41 and Met49 (Figure. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Interaction of N3 in the binding cleft of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID: 6LU7) of COVID-19 shown in (a) 3 D representation and (b) 2 D representation (for better clarity) describing ligands interactions by formation of various H-bonds and hydrophobic interactions with protein at the active site of the protein.

Table-1.

The calculated binding energy, hydrogen bonds and contacting receptor residues of co-crystal ligand N3 and top-five natural compounds with SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (PDB ID: 6LU7) using YASARA structure.

| Compounds Name | Binding energy [kcal/mol] | Hydrogen bonds | Contacting receptor residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| N3 | 7.55 | 8 | Thr24, Thr25, Thr26, Leu27, His41, Val42, Thr45, Ser46, Met49, Tyr54, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165, Glu166, His172, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189 |

| Theaflavin | 10.04 | 4 | His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165, Glu166, Pro168, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Ala191, Gln192 |

| Ginkgetin | 9.64 | 4 | Leu27, His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, Pro168, His172, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Ala191, Gln192 |

| Hesperadin | 8.47 | 4 | Thr24, Thr25, Thr26, Leu27, His41, Met49, Asn142, Gly143, Cys145, His164, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, Pro168, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Gln192 |

| Withanolide-D | 8.37 | 1 | Thr25, Thr26, Leu27, His41, Ser46, Met49, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His164, Met165, Glu166, Pro168, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Ala191, Gln192 |

| Psoralidin | 8.35 | 4 | His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, His172, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Gln192 |

Fig. 2.

Interaction of K36 in the binding cleft of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant Mpro (PDB ID: 7TOB) of COVID-19 shown in (a) 3 D representation and (b) 2 D representation (for better clarity) describing ligands interactions by formation of various H-bonds and hydrophobic interactions with protein at the active site of the protein.

The 7809 compounds compiled from Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical databases, IMPPAT, PhytoHub, AromaDb and Zinc databases were docked against both SARS-CoV-2 and Omicron Mpro protein targets. The natural compounds were selected based on two aspects, the better binding energy of the compound with the target site with preferential interactions within the S1 subsite and the ability of the compound to recruit the highest number of amino acid residues from the binding cleft of N3. The top five natural compounds that secured interactions with the N3 binding cleft were theaflavin, ginkgetin, hesperidin, withanolide D and psoralidin (Figure. 3 ). According to the ranking based on binding energy, theaflavin has the highest binding energy of 10.04 kcal/mol which was better than N3 and K36 binding energy and found to be interacting with His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165, Glu166, Pro168, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190 and Ala191 (Figure. S1). The intermolecular contacts of N3 dock poses were charted using Discovery Studio Visualizer which included one hydrogen bond, two carbon-hydrogen bonds, one π-sulfur bond (covalent bond), one π- π stacked bond, and one π -π T-shaped bond formation was examined. The second best compound in the ranking order based on binding energy was ginkgetin, which had binding energy of 9.643 kcal/mol and interacted with Leu27, His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, Pro168, His172, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Ala191 and Gln192 residues (Figure. S2). Table-1 and Table-2 list the top-ranked compounds, binding energies, rankings and their amino acid interactions with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro protein.

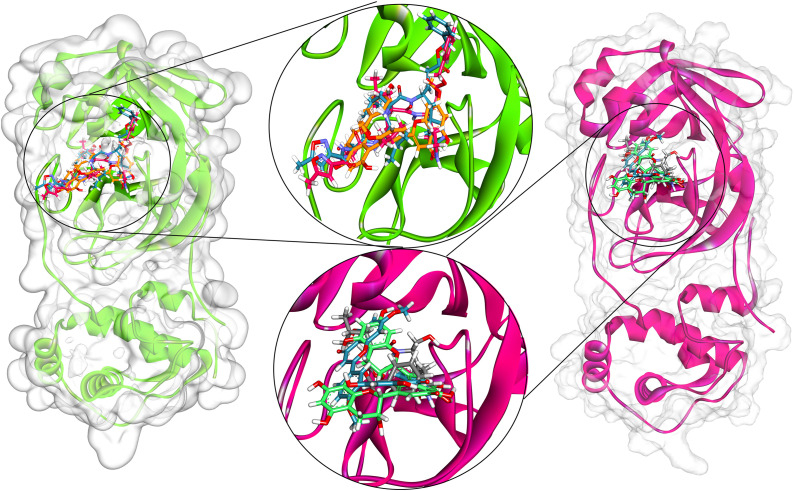

Fig. 3.

Combined docked pose of top-ranked natural compounds with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro PDB ID: 6LU7 and Omicron variant Mpro PDB ID: 7TOB. Interaction of (a) Theaflavin, (b) Ginkgetin, (c) Hesperadin, (d) Withanolide_D and (e) Psoralidin.

Table-2.

The calculated binding energy, hydrogen bonds and contacting receptor residues of co-crystal ligand K36 and top-five natural compounds with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (PDB ID: 7TOB) using YASARA structure.

| Compounds Name | Binding energy [kcal/mol] | Hydrogen bonds | Contacting receptor residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| K36 | 7.80 | 8 | Thr25, Thr26, Leu27, His41, Met49, Pro52, Tyr54, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165, Glu166, His172, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190 |

| Theaflavin | 8.51 | 4 | Thr25, Leu27, His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Ser144, Cys145, His163, His164, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, Pro168, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Ala191 |

| Ginkgetin | 7.80 | 2 | Thr26, His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Ser144, His164, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Ala191 |

| Hesperadin | 7.27 | 3 | Thr24, Thr25, Thr26, Leu27, His41, Met49, Asn142, Gly143, Cys145, His164, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Ala191, Gln192 |

| Withanolide_D | 6.89 | 2 | Thr25, Thr26, Leu27, His41, Ser46, Met49, Ser144, Cys145, His164, Met165, Glu166, Pro168, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190, Ala191, Gln192 |

| Psoralidin | 6.26 | 3 | Thr25, His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His164, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, His172, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189 |

The virtual screening exercise of our natural library was also carried out targeting the Omicron variant of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro protein to study whether the best-ranked natural compounds were able to obtain the best ranks with the Omicron Mpro target. Similar to the SARS-CoV-2 compound ranking, the Omicron Mpro gauged the same set of natural compounds. This includes theaflavin, ginkgetin, hesperidin, withanolide D and psoralidin (Figure. 3) ( Table-2 ). The highest binding energy among the natural compounds was secured by theaflavin with a binding energy of 8.51 kcal/mol with 4 hydrogen bonds (Phe140, Met165, Glu166 and Thr190, 2 π-alkyl bonds (Met49 and Pro168) and 2 π-anion bonds (Glu166) (Figure. S3). Ginkgetin made 2 hydrogen bonds (His163 and Asp187), 1 π-anion bond (Glu166), 2 alkyl bonds (Met49 and Pro168), 2 π-alkyl bonds (Met49 and Met165) with Omicron variant Mpro (Figure. S4). Notably, the interaction profiles of best natural compounds with both SARS-CoV-2 and Omicron Mpro protein revealed common amino acid residues for hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-stacks, π-alkyl and alkyl contacts including (Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His164, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189, Thr190 and Ala191). We also carried out a docking experiment to verify whether the same set of natural compounds generated similar ranks with other SARS-CoV-2 targets. The natural database was screened against other SARS-CoV-2 drug targets such as hemagglutinin-esterase (HE) in complex with 4,9-O-diacetyl sialic acid (PDB entry, 3CL5) and spike receptor-binding domain (RBD) bound with acetylcholinesterase (ACE2, 6M0J). Theaflavin and gingketin were found to be potential binders with both targets. The binding energy of theaflavin with HE target and spike RBD was 6.98 kcal/mol and 6.87 kcal/mol, respectively (Figure. S5). Similarly, gingketin interacted with these targets (8.19 kcal/mol and Figure. S6).

3.2. DFT calculation of crystal and natural compounds

The geometry optimization of N3, K36, theaflavin and ginkgetin was performed in the gas phase and is given in Table-3 and Figure. 4 . The 6–311 g++(d,p)basis sets achieved significantly better energy of optimization indicating more stability of the compounds’ geometry. The HOMO and LUMO energy calculations were done using the 6–311 g++(d,p)basis sets (Table-4 , Figure. S7). Table-4 documents the results of the EHOMO and ELUMO of N3, K36, theaflavin and ginkgetin. Electronic chemical potential (μ) was studied to determine the direction of electron transfer (Figure. S7). The μ of ginkgetin was −3.829 a.u., an electronegative value which was comparatively higher than theaflavin (−4.168 a.u.) and N3 (−4.293 a.u.) implying that electron will certainly be transferred from an occupied orbital to an unoccupied orbital of the ginkgetin molecule to form a stable complex upon binding to Mpro targets in comparison to theaflavin, N3 and K36. In addition, the higher electrophilicity value (ω) of the ginkgetin compared to theaflavin, N3 and K36 highlighted that ginkgetin molecule can acts as a strong donor during ligand binding as well as a contender for tight binding throughout Mpro dynamics. A closer look at the bandgap energy suggests that the theaflavin has lesser energy among others which may exhibit better binding capabilities.

Table-3.

The details of geometry optimization (b3lyp method) of ligands.

| Sr No | Name | Basis set | Optimization Energy (Hartree) |

Fig. No | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | Diff | ||||

| 1 | N3 | 6–31 g(d,p) | −2293.07566 | 0 | S7a |

| 6–311 g(d,p) | −2293.61296 | 0.5373 | |||

| 6–311 g++(d,p) | −2293.65022 | 0.574554 | |||

| 2 | Ginkgetin | 6–31 g(d,p) | −1984.94374 | 0 | S7b |

| 6–311 g(d,p) | −1985.40896 | 0.46522 | |||

| 6–311 g++(d,p) | −1985.4481 | 0.50436 | |||

| 3 | Theaflavin | 6–31 g(d,p) | −2022.17087 | 0 | S7c |

| 6–311 g(d,p) | −2022.66853 | 0.497668 | |||

| 6–311 g++(d,p) | −2022.72206 | 0.55119 | |||

| 6–31 g(d,p) | −1983.19201 | 0 | |||

| 4 | K36 | 6–311 g(d,p) | −1983.6052 | 0.413189 | S1d |

| 6–311 g++(d,p) | −1983.63732 | 0.445313 | |||

Fig. 4.

HOMO-LUMO energy diagram of (a) N3, (b) Theafavin, (c) Ginkgetin and (d) K36.

Table-4.

The HOMO-LUMO details of ligands.

| Sr No. | Ligands | Energy Value (eV) |

Energy Gap (Eg) | Hardness (η) | Softness (S) | Chemical potential (μ) | Electrophilicity index (ω) | Stabilization energy (ΔE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO | LUMO | ||||||||

| 1 | N3 | −6.834 | −1.752 | −5.082 | 2.541 | 0.196773 | −4.293 | 3.626495 | −3.6264953 |

| 2 | Theaflavin | −5.267 | −2.391 | −2.876 | 1.438 | 0.347705 | −3.829 | 5.097789 | −5.0977889 |

| 3 | Ginkgetin | −6.132 | −2.205 | −3.927 | 1.9635 | 0.254647 | −4.1685 | 4.424852 | −4.4248516 |

| 4 | K36 | −6.825 | −1.054 | −5.771 | 2.8855 | 0.17328 | −3.9395 | 2.68925 | −2.6892497 |

3.3. Molecular dynamics simulations of Mpro-ligand complexes

The virtual screening experiment yielded the best-docked complexes which were used to evaluate the conformational stability and time-dependent binding ability of natural ligands in the Mpro catalytic pocket using molecular dynamic simulations [72]. Two pairs of simulations were run by selecting the Mpro target of SARS-CoV-2 and Omicron with best-scored natural compounds together with their respective crystal ligands in re-docked conformations. A total of 6 simulations for Mpro-ligand complexes (SARS-CoV-2: Mpro-N3, Mpro-theaflavin, Mpro-ginkgetin; Omicron: Mpro-K36, Mpro-theaflavin and Mpro-ginkgetin) were carried out for a time period of 1 μs using Schrodinger Desmond package. Furthermore, the apo-Mpro protein (PDB ID: 6Y84) was also subjected to simulations to draw a comparison between ligand-bound and unbound conformational changes. The RMSD measure was computed upon the conformations obtained from the simulation trajectories to study the deviations of ligand binding from its initial reference (docked) pose. Figure. S8 and Figure. S9 illustrate the Cα-RMSD profile for all simulated complexes. The ligands, N3, theaflavin and ginkgetin, experienced little fluctuations in the RMSD profile after 300 ns. Further, the structural comparisons of structures captured at 300 ns with a regular interval of 50 ns with respect to final conformation (1 μs) from the simulation trajectory constituted less than 3 Å RMSD when Cα atoms were aligned. This indicated that the Mpro-ligand complexes attained stabilization and were used to compute the MM/GBSA binding energy for structures belonging to the time interval between 300 and 1000 μs. The RMSD values of N3, theaflavin and ginkgetin for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro were within the range of 9 Å. Contrastingly, Omicron Mpro obtained RMSD in the range of 10 Å for K36 crystal ligand, theaflavin and ginkgetin. The RMSD difference computed over residue index of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and Omicron Mpro variant with apo protein was 0.47 Å and −0.014 Å. This indicates apo and SARS-CoV-2 Mpro have distinct dynamic motions compared to the Omicron variant.

The RMSF evaluative measure locates atoms and amino acid residues experiencing large fluctuations throughout the simulation time. Figure. S10 shows the RMSF profile of simulated SARS-CoV-2 Mpro complexes bound to N3, theaflavin and ginkgetin. Whereas the RMSF profile of Omicron Mpro variant with K36, theaflavin and ginkgetin complexes were presented in Figure. S11. The apo protein was also included to gauze the residue index comparison with both SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and Omicron Mpro variant. RMSF plot shows that gink and Theaflavin bound conformation experienced lesser fluctuation than apo and n3 bound form except for the residue window of 48–60 ns. In a comparison of apo and omicron bound conformation, k36, the and gink experienced less variation in relation to apo form. These residues correspond to loop elements and are located in the N terminal region of the Mpro protein which is in good agreement with earlier reports. The radius of gyration (rGyr) measures the ligand's 'compactness' and is equivalent to its critical depiction of stability during the simulation time. Solvent accessible surface area (SASA) is a measure to study the accessibility of solvent molecules (usually water) towards the protein-ligand complex; the less SASA values indicate less exposure to an aqueous environment and the ability of the complex to preserve hydrophobic core thereby enhancing the stability of complex as a whole [73]. Figure. S12 depicts rGyr and SASA properties of N3, theaflavin and ginkgetin with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. In Theaflavin demonstrates a lower variation than N3 and ginkgetin for rGyr and SASA. As a comparison, the Omicron Mpro variant with K36, theaflavin and ginkgetin complexes were studied which showed similar results for rGyr and SASA (Figure. S13). The intermolecular interactions of N3, theaflavin and ginkgetin were listed in Figure. S14 and Figure. S15 for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and Omicron Mpro, respectively. We observed more than 5 hydrophobic, 15 hydrogen bonds and water bridges in the three simulated complexes of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. We spotted 5 hydrophobic contacts and >15 hydrogen and water bridges in the simulation trajectory of all Omicron Mpro complexes.

3.4. Conservation of intermolecular contacts in molecular dynamics simulations

The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with N3 consisted of hydrophobic interactions in high frequency (Met49, Met165, Leu167, Pro168 and Ala191). It also formed hydrogen bonds with 11 amino acids such as Thr45, Ser46, Asn142, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145, His164, Glu166, Gln189, Thr190 and Gln192. Residues in the sequence window of Thr24 to His163 and Gln 189 to Gln192 formed water bridges. Various types of intermolecular interactions are detected and are shown in Figure. S16. The 2D interaction plots of N3, theaflavin and ginkgetin illustrate the conservation of interactions along the simulation course. The co-crystal ligand N3 retained almost the entire series of crystal interactions including its alkyl moiety interactions with Glu166 (86%) and Gln189 (55%) residues, His164 (water bridges, 56%), and Gly143 (carboxylate group, 35%) (Figure. S16A). The interactions registered in the simulation trajectory are in line with those of dock poses which provides evidence of the tight binding of ligands. The top-ranked theaflavin established 2 hydrophobic interaction with Phe140 (57%), Met165, 2 negative charge with Glu166 (43%) and Asp187 (90%), 1 negatively charged with Arg188 (55%) and 3 polar contacts with Asn142 (64%), Gln189 (30%) and Thr190 (30%) (Figure. S16B). Ginkgetin lost most of the docking-based interactions in the simulations. One polar and hydrophobic interaction was identified with Gln189 and Met165 in 30% frames (Figure. S16C). The co-crystal ligand K36 of Omicron Mpro exhibited hydrophobic contacts with His41 and Met49 residues which were similar to those present in SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and additionally interacted with Leu27, Cys44 (46%), Thr45 (31%), Cys145 (77%) and Glu166 (3%) (Figure. S17A). Theaflavin developed hydrophobic interactions with Gly166 (73%) and Asp187 (59%), while 1 hydrogen bond was formed with His164 (54%) (Figure. S17B). However, ginkgetin maintained only one polar bond with His 41 (34%) (Figure. S17C).

All simulated complexes were analyzed to recognize the structural level integrity and conformational changes at every 100 ns time interval. Figure. S18 shows the interaction analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro bound to N3. A total of 7 hydrophobic and 8 hydrogen bonds were noted at the beginning of the simulation. However, a single covalent bond was developed which was present in the interaction profile of ligand N3. After the completion of 1 μs simulation time, residues such as His41, Met49, Pro168 and Ala191 switched to hydrophobic interactions. In comparison to simulation of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-theaflavin complex, His41, Cys145, Met165, Thr190 and Ala191 built new hydrophobic contacts which were absent in the starting structure (Figure. S19). The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro-ginkgetin complex developed 9 hydrogen and 7 hydrophobic interactions in its initial conformation but tend to maintain only 4 hydrogen bonds at the end of the simulation (Figure. S20). The comparative study of the Omicron Mpro-K36 complex revealed residues such as Gln16, Thr26, Cys44, Ser46, Gly143, Ser144, Cys145 and Glu166 coordinated hydrogen bonds at the completion of simulation (Figure. S21). Theaflavin possessed a huge difference in the interaction list of hydrogen and hydrophobic interactions as shown for SARS-CoV-2 (Figure. S22) and instead created contacts with Ser46, Glu47, Leu50, Cys145, Met165, Pro168, Gly170 and Gln189. Ginkgetin ended with a high number of hydrogen bonds at the end of the simulation. Figure. S23 illustrates the ginkgetin contacts with Arg40, Glu166, Phe185, Val186, Arg188, Thr190 and Gln192 whereas hydrophobic interactions were generated with Cys44, Met49, Met165, Leu167 and Phe181.

3.5. MM/GBSA binding free energy calculation of Mpro-ligand complexes

SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with N3, theaflavin and ginkgetin, and Omicron Mpro in complex with K36, theaflavin and ginkgetin, were used to compute the free energy of ligand binding using the MM/GBSA approach. This was accomplished by performing a post-simulation analysis of captured frames of the trajectory created at the end of the MD simulation (Table-5 and Table-6 ). The structures of Mpro bound to N3, theaflavin and ginkgetin within the time window of 300 ns to 1 μs from their respective simulation trajectory were given as inputs for computing MM/GBSA scores. The ligand N3 has higher binding potency (−80.75 kcal/mol) than theaflavin and ginkgetin with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (Table-5). Ginkgetin was identified as a better binder (−41.54 kcal/mol) of Omicron Mpro among others (Table-6). The comparison of 3D interaction patterns (obtained after 1 μs simulation) of theaflavin bound to Mpro targets of SARS-CoV-2 Alpha and Omicron variants showed that the enhancement in the intermolecular contacts with pocket residues in addition to Glu166 and Asp187 in the Alpha variant (Figure. S16B) is responsible for tight binding whereas sole interactions with Glu166 and Asp187 residues as noted in Omicron variant (Figure. S17B) do not necessarily indicate better binding. This notion was also reflected in the free energy of binding computed using the MM/GBSA approach. Collectively, the increased number of contacts together with Glu166 and Asp187 residues may be the strategy for developing potent Mpro inhibitory molecules.

Table-5.

MM/GBSA profiles of N3, Theaflavin and Ginkgetin in interaction with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

| Ligands | ΔGbind |

Enthalpy (ΔGMM) |

Entropy (ΔGPB) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding free energy (kcal/mol) | van der Waals interactions (kcal/mol) | Coulomb energy (kcal/mol) | Covalent bonding (kcal/mol) | Hbond (kcal/mol) | Lipophilicity (kcal/mol) | Solv_GB (kcal/mol) | |

| N3 | −80.75 | −65.44 | −29.66 | 4.89 | −2.98 | −16.55155505 | 29.85 |

| Theaflavin | −71.33 | −55.52 | −37.35 | 9.09 | −4.39 | −13.29233041 | 33.36 |

| Ginkgetin | −58.52 | −47.86 | −13.85 | 2.22 | −1.15 | −14.08843961 | 19.85 |

Table-6.

MM/GBSA profiles of K36, Theaflavin and Ginkgetin in interaction with the Omicron variant of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro protein.

| Ligands | ΔGbind |

Enthalpy (ΔGMM) |

Entropy (ΔGPB) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding free energy (kcal/mol) | van der Waals interactions (kcal/mol) | Coulomb energy (kcal/mol) | Covalent bonding (kcal/mol) | Hbond (kcal/mol) | Lipophilicity (kcal/mol) | Solv_GB (kcal/mol) | |

| K36 | −19.39 | −15.41 | −7.35 | 0.38 | −0.54 | −3.72 | 7.36 |

| Theaflavin | −36.14 | −27.11 | −21.79 | 3.33 | −2.00 | −8.43 | 20.87 |

| Ginkgetin | −41.54 | −32.73 | −11.45 | 2.47 | −0.93 | −8.93 | 13.20 |

4. Discussion

This COVID-19 outbreak is the third devastating global Coronavirus outbreak that has resulted in severe illness and fatalities. CoVs are a sizable virus family that affects a variety of species, including humans. The newly discovered COVID-19 coronavirus, also known as SARS-CoV-2 because of its 89.1% structural similarity to the MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, has very high transmissibility to spread throughout humans [74]. One of the twelve proteins targeted for CoV regulation, Mpro is one of the most crucial targets due to its significance in genetic transcription and replication. The structures of SARS-CoV2 Mpro co-crystalized with different ligands (N3 and K36) formed the basis for providing crucial intermolecular contacts and aided in developing new compound leads. In this present study, N3 and K36 were used as reference molecules to assess the efficacy of identified natural compounds using a rigorous computational approach with inhibition potential. Further, the native ligands as well as identified compounds were investigated for their potential to acquire similar molecular properties at the DFT level to validate independently the potential to inhibit Mpro. The HOMO-LUMO energy profile gives an overview of the bandgap energy responsible for energy transfer and indicates inhibitory potential matching those of co-crystallized ligands [75]. Some previously developed compounds for SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV include Hesperetin, Calmidazolium, Cinanserin, Aza-peptide epoxides, FL-166, 8c, 2a, and 4o [76,77].

A potential solution for an accelerated clinical trial of a lead compound to suppress SARS-CoV-2 targets is to identify bioactive compounds with better ADMET profiles by conducting theoretical studies at a high-throughput scale. Arya et al., recently suggested Procainamide, Tetrahydrozoline, and Levamisole interact with SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease [78]. Theaflavin is a polyphenol abundant in tea and known for its efficacy against lung cancer. Various computational and in vitro studies showed significant inactivation of the SARS-CoV-2 targets using natural compounds [[79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85]] [[79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85]] [[79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85]]. A flavone with anti-adipogenic, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, and neuroprotective properties is ginkgetin [86]. By inhibiting the cell cycle, inducing apoptosis, encouraging autophagy, and addressing various out-of-control signaling pathways like JAK/STAT and MAPKs, it reduces the growth of cancer. Additionally, it prevents neuron apoptosis, eliminates cerebral microhemorrhage, lowers neurologic impairments, and offers effective neuroprotection against oxidative stress-induced cell death. It also contains leishmanicidal, antiplasmodial, antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal effects. In vitro studies have demonstrated that Ginkgo biloba considerably lowers the risk of atherosclerosis, cancer, neurodegenerative, hepatic, autoimmune, and influenza diseases [87]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated through experimentation that ginkgetin is capable of inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 targets, including the Omicron form [85]. We believe that a rigorous computational approach combining molecular docking, dynamic simulations, free energy calculations of ligand binding and DFT analysis narrows down from a large library to a sizeable amount of small molecular leads with better ADMET properties. Natural compounds which have been tested for other physiological conditions can be repurposed to assess their antiviral properties and can be tested against different variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Author approvals

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript, and that it hasn't been accepted or published elsewhere.

Funding

The research work has not been granted any fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary Information files).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106318.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Acter T., Uddin N., Das J., Akhter A., Choudhury T.R., Kim S. Evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: a global health emergency. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;730 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sifuentes-Rodríguez E., Palacios-Reyes D. Covid-19: the outbreak caused by a new coronavirus. Bol. Med. Hosp. Infant. Mex. 2020;77:47–53. doi: 10.24875/BMHIM.20000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorbalenya A.E., Baker S.C., Baric R.S., de Groot R.J., Drosten C., Gulyaeva A.A., Haagmans B.L., Lauber C., Leontovich A.M., Neuman B.W., Penzar D., Perlman S., Poon L.L.M., Samborskiy D., Sidorov I.A., Sola I., Ziebuhr J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: the species and its viruses – a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.07.937862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcés-Ayala F., Araiza-Rodríguez A., Mendieta-Condado Edgar, Rodríguez-Maldonado Abril P., Wong-Arámbula C., Landa-Flores M., Carlos Del Mazo-López J., González-Villa M., Escobar-Escamilla N., Fragoso-Fonseca David E., María, Esteban-Valencia C., Lloret-Sánchez L., Dayanira, Arellano-Suarez S., Nuñez-García Tatiana E., Nervain, Contreras-González B., Cruz-Ortiz N., Ruiz-López A., Fierro-Valdez Miguel Á., Regalado-Santiago D., Martínez-Velázquez N., Mederos-Michel M., Vázquez-Pérez J., Martínez-Orozco José A., Becerril-Vargas Eduardo, Salas J., Hernández-Rivas Lucía, López-Martínez I., Luis Alomía-Zegarra J., López-Gatell Hugo, Barrera-Badillo G., Ramírez-González E. Full genome sequence of the first SARS-CoV-2 detected in Mexico. Arch. Virol. 2020;165:2095–2098. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04695-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ n.d.

- 6.Bhardwaj V.K., Singh R., Sharma J., Rajendran V., Purohit R., Kumar S. Identification of bioactive molecules from tea plant as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1766572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li P., Wang Y., Lavrijsen M., Lamers M.M., de Vries A.C., Rottier R.J., Bruno M.J., Peppelenbosch M.P., Haagmans B.L., Pan Q. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is highly sensitive to molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, and the combination. Cell Res. 2022;32:322–324. doi: 10.1038/S41422-022-00618-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goss A.L., Samudralwar R.D., Das R.R., Nath A. ANA investigates: neurological complications of COVID-19 vaccines. Ann. Neurol. 2021;89:856. doi: 10.1002/ANA.26065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gohar U.F., Iqbal I., Shah Z., Mukhtar H., Zia-Ul-Haq M. COVID-19: recent developments in therapeutic approaches. Altern. Med. Interv. COVID- 2021;19:249–274. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-67989-7_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leao J.C., Gusmao T.P. de L., Zarzar A.M., Leao Filho J.C., Barkokebas Santos de Faria A., Morais Silva I.H., Gueiros L.A.M., Robinson N.A., Porter S., Carvalho A. de A.T. Coronaviridae—old friends, new enemy. Oral Dis. 2022;28:858–866. doi: 10.1111/ODI.13447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frere J.J., Serafini R.A., Pryce K.D., Zazhytska M., Oishi K., Golynker I., Panis M., Zimering J., Horiuchi S., Hoagland D.A., Møller R., Ruiz A., Kodra A., Overdevest J.B., Canoll P.D., Borczuk A.C., Chandar V., Bram Y., Schwartz R., Lomvardas S., Zachariou V., tenOever B.R. SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters and humans results in lasting and unique systemic perturbations post recovery. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022 doi: 10.1126/SCITRANSLMED.ABQ3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakraborty C., Bhattacharya M., Nandi S.S., Mohapatra R.K., Dhama K., Agoramoorthy G. Appearance and re-appearance of zoonotic disease during the pandemic period: long-term monitoring and analysis of zoonosis is crucial to confirm the animal origin of SARS-CoV-2 and monkeypox virus. 2022. Https://Doi.Org/10.1080/01652176.2022.2086718. 42 119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Liu P., Jiang J.Z., Wan X.F., Hua Y., Li L., Zhou J., Wang X., Hou F., Chen J., Zou J., Chen J. Are pangolins the intermediate host of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)? PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PPAT.1008421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H., Yang M., Ding Y., Liu Y., Lou Z., Zhou Z., Sun L., Mo L., Ye S., Pang H., Gao G.F., Anand K., Bartlam M., Hilgenfeld R., Rao Z. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:13190–13195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835675100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y., Yu J., Wang L., Yang K., Liu F., Jiang R., Yang X., You T., Liu X., Yang X., Bai F., Liu H., Liu X., Guddat L.W., Xu W., Xiao G., Qin C., Shi Z., Jiang H., Rao Z., Yang H. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S., Nyodu R., Maurya V.K., Saxena S.K. Morphology, genome organization, replication, and pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) 2020. 23–31. [DOI]

- 18.Patel C.N., Goswami D., Sivakumar K., Pandya H.A. Repurposing of anticancer phytochemicals for identifying potential fusion inhibitor for SARS-CoV-2 using molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Bakhshandeh B., Jahanafrooz Z., Abbasi A., Goli M.B., Sadeghi M., Mottaqi M.S., Zamani M. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2; Consequences in structure, function, and pathogenicity of the virus. Microb. Pathog. 2021;154 doi: 10.1016/J.MICPATH.2021.104831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yadav R., Chaudhary J.K., Jain N., Chaudhary P.K., Khanra S., Dhamija P., Sharma A., Kumar A., Handu S. Role of structural and non-structural proteins and therapeutic targets of SARS-CoV-2 for COVID-19. Cells. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/CELLS10040821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai W., Zhang B., Jiang X.-M., Su H., Li J., Zhao Y., Xie X., Jin Z., Peng J., Liu F., Li C., Li Y., Bai F., Wang H., Cheng X., Cen X., Hu S., Yang X., Wang J., Liu X., Xiao G., Jiang H., Rao Z., Zhang L.-K., Xu Y., Yang H., Liu H. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. https://www.science.org n.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bhardwaj V.K., Purohit R. Targeting the protein-protein interface pocket of Aurora-A-TPX2 complex: rational drug design and validation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1772109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng S.C., Chang G.G., Chou C.Y. Mutation of Glu-166 blocks the substrate-induced dimerization of SARS coronavirus main protease. Biophys. J. 2010;98:1327. doi: 10.1016/J.BPJ.2009.12.4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.C.C.-19 R. Team SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant — United States, December 1–8, 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021;70:1731. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM7050E1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma V., Rai H., Gautam D.N.S., Prajapati P.K., Sharma R. Emerging evidence on Omicron (B.1.1.529) SARS-CoV-2 variant. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:1876–1885. doi: 10.1002/JMV.27626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramakrishnan M.S., Patel A.P., Melles R., Vora R.A. Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome: findings from a large northern California cohort. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2021;5:850–854. doi: 10.1016/J.ORET.2020.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaku C.I., Bergeron A.J., Ahlm C., Normark J., Sakharkar M., Forsell M.N.E., Walker L.M. Immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 breakthrough infections: to change the vaccine or not? Sci. Immunol. 2022;7:8891. doi: 10.1126/SCIIMMUNOL.ABQ5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ullrich S., Ekanayake K.B., Otting G., Nitsche C. Main protease mutants of SARS-CoV-2 variants remain susceptible to nirmatrelvir. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2022;62 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2022.128629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santhi V.P., Masilamani P., Sriramavaratharajan V., Murugan R., Gurav S.S., Sarasu V.P., Parthiban S., Ayyanar M. Therapeutic potential of phytoconstituents of edible fruits in combating emerging viral infections. J. Food Biochem. 2021;45 doi: 10.1111/JFBC.13851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar A., Choudhir G., Shukla S.K., Sharma M., Tyagi P., Bhushan A., Rathore M. Identification of phytochemical inhibitors against main protease of COVID-19 using molecular modeling approaches. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39:3760–3770. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1772112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.P. Pandey, J.S. Rane, A. Chatterjee, A. Kumar, R. Khan, A. Prakash, S. Ray, J. Subhash, R. B#, Targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein of COVID-19 with naturally occurring phytochemicals: an in silico study for drug development, (n.d.). 10.1080/07391102.2020.1796811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.ZINC − A Free Database of Commercially Available Compounds for Virtual Screening | Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, (n.d.). https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/ci049714%2B (accessed July 3, 2022). (2005):45(1), 177-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Mohanraj K., Karthikeyan B.S., Vivek-Ananth R.P., Chand R.P.B., Aparna S.R., Mangalapandi P., Samal A. IMPPAT: a curated database of Indian medicinal plants, phytochemistry and therapeutics. Sci. Rep. 2018;81(2018):1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22631-z. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.PhytoHub V1.4 A new release for the online database dedicated to food phytochemicals and their human metabolites - human Nutrition Unit. https://hal.laas.fr/UNH/hal-01607427 (n.d.)

- 35.Kumar Y., Prakash O., Tripathi H., Tandon S., Gupta M.M., Rahman L.U., Lal R.K., Semwal M., Darokar M.P., Khan F. AromaDb: a database of medicinal and aromatic plant's aroma molecules with phytochemistry and therapeutic potentials. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1081. doi: 10.3389/FPLS.2018.01081/BIBTEX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duke J.A. 2017. Handbook of Phytochemical Constituents of GRAS Herbs and Other Economic Plants. Herbal Reference Library, Handb. Phytochem. Const. GRAS Herbs Other Econ. Plants. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krieger E., Darden T., Nabuurs S.B., Finkelstein A., Vriend G. Making optimal use of empirical energy functions: force-field parameterization in crystal space. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 2004;57:678–683. doi: 10.1002/PROT.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Land H., Humble M.S., YASARA A tool to obtain structural guidance in biocatalytic investigations. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1685:43–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7366-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krieger E., Nther Koraimann G., Vriend G. Increasing the precision of comparative models with YASARA NOVA-a self-parameterizing force field. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Sacco M.D., Hu Y., Gongora M.V., Meilleur F., Kemp M.T., Zhang X., Wang J., Chen Y. The P132H mutation in the main protease of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 decreases thermal stability without compromising catalysis or small-molecule drug inhibition. Cell Res. 2022;325(32):498–500. doi: 10.1038/s41422-022-00640-y. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krieger E., Darden T., Nabuurs S.B., Finkelstein A., Vriend G. vol. 57. Wiley Online Libr; 2004. pp. 678–683. (Making Optimal Use of Empirical Energy Functions: Force-Field Parameterization in Crystal Space). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel C.N., Georrge J.J., Modi K.M., Narechania M.B., Patel D.P., Gonzalez F.J., Pandya H.A. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening of catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors to combat Alzheimer's disease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2018;36:3938–3957. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2017.1404931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.A M., VK S., D M.K., M M., SP K., SK K., RS U., U A., S S. Silico prediction, characterization, molecular docking, and dynamic studies on fungal SDRs as novel targets for searching potential fungicides against Fusarium wilt in tomato. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/FPHAR.2018.01038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel C.N., Jani S.P., Jaiswal D.G., Kumar S.P., Mangukia N., Parmar R.M., Rawal R.M., Pandya H.A. Identification of antiviral phytochemicals as a potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) inhibitor using docking and molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 2021;111(11):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99165-4. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krieger E., Vriend G. New ways to boost molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2015;36:996–1007. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frisch A. 1996. Gaussian 09W Reference. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sztain T., Amaro R., McCammon J.A. Elucidation of cryptic and allosteric pockets within the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021 doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00140. acs.jcim.1c00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The Structure of Small Molecules and Ions. Springer US; 1988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dizaji N.J., Nouri A., Zahedi E., Musavi S.M., Nouri A. Regioselectivity of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions between aryl azides and an electron-deficient alkyne through DFT reactivity descriptors. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017;43:767–782. doi: 10.1007/s11164-016-2663-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suvitha A., Venkataramanan N.S., Mizuseki H., Kawazoe Y., Ohuchi N. Theoretical insights into the formation, structure, and electronic properties of anticancer oxaliplatin drug and cucurbit[n]urils n = 5 to 8. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2010;66:213–218. doi: 10.1007/s10847-009-9601-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fakhari S., Nouri A., Jamzad M., Arab-Salmanabadi S., Falaki F. Investigation of inclusion complex of metformin into selective cyclic peptides as novel drug delivery system: structure, electronic properties, AIM, and NBO study via DFT. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2021;68:67–75. doi: 10.1002/jccs.202000304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koopmans T. Über die Zuordnung von Wellenfunktionen und Eigenwerten zu den Einzelnen Elektronen Eines Atoms. Physica. 1934;1:104–113. doi: 10.1016/S0031-8914(34)90011-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pearson R.G. Chemical hardness and density functional theory. J. Chem. Sci. 2005;117:369–377. doi: 10.1007/BF02708340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houk K.N. The frontier molecular orbital theory of cycloaddition reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 1975;8:361–369. doi: 10.1021/ar50095a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kohn W., Becke A.D., Parr R.G. Density functional theory of electronic structure. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:12974–12980. doi: 10.1021/jp960669l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geerlings P., De Proft F., Langenaeker W. Conceptual density functional theory. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:1793–1873. doi: 10.1021/cr990029p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J.D., Impey R.W., Klein M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;79:926. doi: 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jorgensen W.L., Tirado-Rives J. The OPLS potential functions for proteins. Energy minimizations for crystals of cyclic peptides and crambin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:1657–1666. doi: 10.1021/ja00214a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryabov V.A. Constant pressure–temperature molecular dynamics on a torus. Phys. Lett. 2006;359:61–65. doi: 10.1016/J.PHYSLETA.2006.05.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Braga C., Travis K.P. A configurational temperature Nosé-Hoover thermostat. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;123 doi: 10.1063/1.2013227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marsili S., Signorini G.F., Chelli R., Marchi M., Procacci P. ORAC: a molecular dynamics simulation program to explore free energy surfaces in biomolecular systems at the atomistic level. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:1106–1116. doi: 10.1002/JCC.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar Y., Singh H., Patel C.N. Silico prediction of potential inhibitors for the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 using molecular docking and dynamics simulation based drug-repurposing. J. Infect. Public Health. 2020;13:1210–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kollman P.A., Massova I., Reyes C., Kuhn B., Huo S., Chong L., Lee M., Lee T., Duan Y., Wang W., Donini O., Cieplak P., Srinivasan J., Case D.A., Cheatham T.E. Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Essmann U., Perera L., Berkowitz M.L., Darden T., Lee H., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. doi: 10.1063/1.470117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang J., Hou T., Xu X. Recent advances in free energy calculations with a combination of molecular mechanics and continuum models. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2006;2:287–306. doi: 10.2174/157340906778226454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang D., Lazim R. Application of conventional molecular dynamics simulation in evaluating the stability of apomyoglobin in urea solution. Sci. Rep. 2017;71(7):1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep44651. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Massova I., Kollman P.A. Combined molecular mechanical and continuum solvent approach (MM- PBSA/GBSA) to predict ligand binding. Perspect. Drug Discov. Des. 2000;18:113–135. doi: 10.1023/A:1008763014207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hou T., Wang J., Li Y., Wang W. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 1. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:69–82. doi: 10.1021/CI100275A/SUPPL_FILE/CI100275A_SI_001.PDF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Genheden S., Ryde U. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Sun H., Li Y., Tian S., Xu L., Hou T. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 4. Accuracies of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methodologies evaluated by various simulation protocols using PDBbind data set running title: accuracies of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA evaluated by a large dataset. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. Accept. Manuscr. (n.d.). 2014;16(31):16719–16729. doi: 10.1039/C4CP01388C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li J., Abel R., Zhu K., Cao Y., Zhao S., Friesner R.A. The VSGB 2.0 model: a next generation energy model for high resolution protein structure modeling. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2011;79:2794–2812. doi: 10.1002/PROT.23106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mhatre S., Naik S., Patravale V. A molecular docking study of EGCG and theaflavin digallate with the druggable targets of SARS-CoV-2. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;129 doi: 10.1016/J.COMPBIOMED.2020.104137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ohgitani E., Shin-Ya M., Ichitani M., Kobayashi M., Takihara T., Kawamoto M., Kinugasa H., Mazda O. Significant inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro by a green tea catechin, a catechin-derivative, and black tea galloylated theaflavins. Mol. 2021;26(2021):3572. doi: 10.3390/MOLECULES26123572. 3572. 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maiti S., Banerjee A. Epigallocatechin gallate and theaflavin gallate interaction in SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein central channel with reference to the hydroxychloroquine interaction: bioinformatics and molecular docking study. Drug Dev. Res. 2021;82:86–96. doi: 10.1002/DDR.21730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Banerjee A., Kanwar M., Maiti S. Theaflavin-3′-O-gallate a black-tea constituent blocked SARS CoV-2 RNA dependant RNA polymerase active-site with better docking results than remdesivir. Drug Res. 2021;71:462–472. doi: 10.1055/A-1467-5828/ID/R2020-12-2197-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goc A., Sumera W., Rath M., Niedzwiecki A. Phenolic compounds disrupt spike-mediated receptor-binding and entry of SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-virions. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0253489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Takeda Y., Tamura K., Jamsransuren D., Matsuda S., Ogawa H. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 inactivation activity of the polyphenol-rich tea leaf extract with concentrated theaflavins and other virucidal catechins. Molecules. 2021;26 doi: 10.3390/MOLECULES26164803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bauer R., Katanic Stankovic J.S., Lin S., Wang X., Wai-Lun Tang R., Chun Lee H., Hin Chan H., A Choi S.S., Ting-Xia Dong T., Wing Leung K., Webb S.E., Miller A.L., Wah-Keung Tsim K. The extracts of polygonum cuspidatum root and rhizome block the entry of SARS-CoV-2 wild-type and omicron pseudotyped viruses via inhibition of the S-protein and 3CL protease. Mol. 2022;27(2022):3806. doi: 10.3390/MOLECULES27123806. 3806. 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kreiser T., Zaguri D., Sachdeva S., Zamostiano R., Mograbi J., Segal D., Bacharach E., Gazit E. Inhibition of respiratory RNA viruses by a composition of ionophoric polyphenols with metal ions. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15 doi: 10.3390/PH15030377/S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dey D., Hossain R., Biswas P., Paul P., Islam M.A., Ema T.I., Gain B.K., Hasan M.M., Bibi S., Islam M.T., Rahman M.A., Kim B. Amentoflavone derivatives significantly act towards the main protease (3CL PRO/M PRO) of SARS-CoV-2: in silico admet profiling, molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, network pharmacology. Mol. Divers. 2022 doi: 10.1007/S11030-022-10459-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xiong Y., Zhu G.H., Wang H.N., Hu Q., Chen L.L., Guan X.Q., Li H.L., Chen H.Z., Tang H., Ge G.B. Discovery of naturally occurring inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro from Ginkgo biloba leaves via large-scale screening. Fitoterapia. 2021;152 doi: 10.1016/J.FITOTE.2021.104909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Murugesan S., Kottekad S., Crasta I., Sreevathsan S., Usharani D., Perumal M.K., Mudliar S.N. Targeting COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) main protease through active phytocompounds of ayurvedic medicinal plants - emblica officinalis (Amla), Phyllanthus niruri Linn. (Bhumi Amla) and Tinospora cordifolia (Giloy) - a molecular docking and simulation study. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021;136 doi: 10.1016/J.COMPBIOMED.2021.104683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Raj V., Lee J.H., Shim J.J., Lee J. Antiviral activities of 4H-chromen-4-one scaffold-containing flavonoids against SARS-CoV-2 using computational and in vitro approaches. J. Mol. Liq. 2022;353 doi: 10.1016/J.MOLLIQ.2022.118775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Park J., Park R., Jang M., Park Y.I., Park Y. Coronavirus enzyme inhibitors-experimentally proven natural compounds from plants. J. Microbiol. 2022;603(60):347–354. doi: 10.1007/S12275-022-1499-Z. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Antonopoulou I., Sapountzaki E., Rova U., Christakopoulos P. Inhibition of the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 (M pro) by repurposing/designing drug-like substances and utilizing nature's toolbox of bioactive compounds. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022;20:1306–1344. doi: 10.1016/J.CSBJ.2022.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Adnan M., Rasul A., Hussain G., Shah M.A., Zahoor M.K., Anwar H., Sarfraz I., Riaz A., Manzoor M., Adem Ş., Selamoglu Z. Ginkgetin: a natural biflavone with versatile pharmacological activities. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020;145 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sati S.C., Joshi S. Antibacterial activities of Ginkgo biloba L. Leaf extracts. Sci. World J. 2011;11:2237. doi: 10.1100/2011/545421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary Information files).