Summary

Background

Food environments have been recognised as highly influential on population diets. Government policies have great potential to create healthy food environments to promote healthy diets. This study aimed to evaluate food environment policy implementation in European countries and identify priority actions for governments to create healthy food environments.

Methods

The Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI) was used to evaluate the level of food environment policy and infrastructure support implementation in Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain in 2019–2021. Evidence of implementation of food environment policies was compiled in each country and validated by government officials. National experts evaluated the implementation of policies and identified priority recommendations.

Findings

Finland had the highest proportion (32%, n = 7/22) of policies shaping food environments with a “high” level of implementation. Slovenia and Poland had the highest proportion of policies rated at very low implementation (42%, n = 10/24 and 36%, n = 9/25 respectively). Policies regarding food provision, promotion, retail, funding, monitoring, and health in all policies were identified as the most important gaps across the European countries. Experts recommended immediate action on setting standards for nutrients of concern in processed foods, improvement of school food environments, fruit and vegetable subsidies, unhealthy food and beverage taxation, and restrictions on unhealthy food marketing to children.

Interpretation

Immediate implementation of policies and infrastructure support that prioritize action towards healthy food environments is urgently required to tackle the burden of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases in Europe.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 774548 and from the Joint Programming Initiative “A Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life”.

Keywords: Food environments, Obesity, Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), Public health policies, Healthy food environment policy index (Food-EPI), Europe

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Effective government policies and actions are key to create healthy food environments that enable healthy diets and reduce the pervasive levels of obesity, diet-related non-communicable disease (NCD), and their related inequalities.9

The EU, Article 168 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the Farm to Fork Strategy, the EU Action Plan on childhood obesity 2014-2020, the European Child Guarantee, the EU cancer beating plan and the WHO European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015-2020 indicate that more ambitious food environment policies are required for countries to achieve global nutrition targets. However, there is a lack of evidence on the level of implementation of food environment policies across Europe. The European Economic Area (EEA) countries currently lack a harmonized systematic overview and evaluation of policy implementation to create healthier food environments and improve population nutrition.

The International Network for Food and Obesity/Non-communicable Diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support (INFORMAS) has developed the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI) as a tool and process for national governments to assess their policies, identify and prioritise policy and infrastructure support actions for the creation of healthy food environments.

Previous research at the European Union level showed that there is much potential for the EU to improve its policies influencing food environments. This study identified strategic priority actions focused on improving food environments which are required to reduce obesity and NCDs in the EU.23 However, the study did not assess the policies and infrastructure support implemented at country level. Although some European countries have implemented food and nutrition policies, a focus on more ambitious and mandatory policies is required to create healthy food environments. The status quo shows there is insufficient knowledge on how countries across Europe could improve their food environment policies to reduce the rising levels of obesity and NCDs.

Added value of this study

This is the first study to systematically assess and monitor the level of food environment policy and infrastructure support implementation in European countries using a validated and adapted tool.

The study provided an ‘upstream’ perspective of the policies and infrastructure support systems that influence the food environments and dietary choices, for the prevention of obesity and NCDs in 11 European countries. The process of consultation with experts allowed an accurate picture of policy action and gaps and helped identify relevant and feasible policy actions for the improvement of food environments across European countries. The creation of an evidence document for each of the participating European countries provides a useful resource for government and non-government sectors wishing to examine policy gaps, coherence and compliance of food environment and public health nutrition policies in European countries.

Implications of all the available evidence

The process of monitoring progress in the implementation of food environment policies will contribute to establish healthier food environments that enable healthier diets and reduce the burden of obesity and NCDs. Addressing the burden of diet-related NCDs and improving population nutrition requires a systems approach. A comprehensive intervention package should be implemented including a wide range of structural population level policy actions. Public health nutrition interventions should operate effectively within the overall food, system and national, European, and global economies and align with policies across food systems. It is necessary for national and local governments to develop and implement effective policies to improve food environments and reduce related socioeconomic inequalities and to provide equitable access to healthy food choices for all.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

More than half of the European adult population have overweight or obesity.1 The obesity epidemic is a major public health concern as it significantly increases the risk of diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular disease, type-2 diabetes, and some types of cancer, as well as mental health problems.2 For society, unhealthy diets and diet-related NCDs lead to substantial direct and indirect costs that strain healthcare systems and social resources.3 The economic burden of NCDs in the EU is increasing with annual healthcare costs exceeding €300 billion, plus an additional €200 billion due to productivity losses and informal care costs.4 Further, large socioeconomic inequalities in overweight and obesity are observed. People with a lower educational level are more likely to be living with overweight and obesity than those with a higher educational level in most European countries,5 and a widening of absolute socioeconomic inequalities in obesity prevalence has been observed in 15 European countries.6

The rise of overweight, obesity and diet-related NCDs over the past decades, and the widening of inequalities in these outcomes, have been associated with a growing exposure to obesogenic food environments in Europe and globally. Food environments encompass people's surroundings in terms of structure, economy, policies, sociocultural factors, and opportunities and conditions.7 Over the past decades, ultra-processed, energy-dense and nutrient poor food products have become more available, heavily promoted, and relatively more affordable compared to fresh, minimally, or unprocessed foods, creating obesogenic food environments, which limit access to healthy affordable diets and are a product of policy action or inaction across multiple sectors.8 With this, unhealthy food environments have become major drivers of inequalities in poor population diets, overweight, obesity and diet-related NCDs.

Despite the commitment to address obesity and diet-related NCDs as part of the European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020, health inequalities across Europe continue to widen.10 National governments are the major stakeholders with the greatest capacity to modify food environments and population diets.9,11 Effective policies can improve food environments, that in turn improve population's nutritional status and prevent overweight, obesity, and diet-related NCDs. Improving food environments has been found more effective in decreasing socioeconomic inequalities in diets and health than individual focused measures (e.g., nutritional education, healthy eating campaigns).12 Some European countries have taken action to improve the healthiness of food environments.13,14 However, an integrated policy approach and replacing voluntary policies with effective restrictions to improve food environments is required.

In the EU, Article 168 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union states that a high level of human health protection shall be ensured in the definition and implementation of all EU policies and activities.15,16 In addition, the Farm to Fork Strategy,17 the EU Action Plan on childhood obesity 2014-2020,18 the European Child Guarantee,19 the EU cancer beating plan,20 and the WHO European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–202010 indicate that more ambitious food environment policies are required for countries to achieve global nutrition targets.10 However, there is a lack of evidence on the level of implementation of food environment policies across Europe EEA countries currently lack a harmonized systematic overview and evaluation of policy implementation to create healthier food environments and improve population nutrition.9

In addition, the World Health Organization has stated the importance of monitoring and benchmarking food environments and policies around the globe to make progress in the improvement of the food environment and therefore reduce the prevalence of obesity and NCDs.21 The INFORMAS7 has developed the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI) as a tool and process for national governments to assess their policies, identify and prioritise policy and infrastructure support actions for the creation of healthy food environments.7

Although some European countries have implemented food and nutrition policies, a focus on more ambitious and mandatory policies is required to create healthy food environments. In addition, there is insufficient knowledge on how countries across Europe could improve their food environments and how present policies could be improved. Therefore, this study aimed to assess differences between European countries in their level of implementation of food environment policies and infrastructure support for policy development and implementation, and to determine the differences in their prioritized actions to create healthy food environments.15

Methods

This research is part of two EU funded consortia: the Policy Evaluation Network (PEN)22 to advance the evidence base for public policies impacting on dietary behaviour, physical activity, and sedentary behaviour in Europe (JPI Healthy Diet for a Healthy Life) and the Science & Technology in childhood Obesity Policy (STOP), a Horizon 2020-funded project to tackle childhood obesity, with the aim to expand and Consolidate the multi-disciplinary evidence base upon which effective and sustainable policies can be built to prevent and manage childhood obesity. The former, PEN, encompassed the countries of Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, and Poland whilst STOP included Estonia, Finland, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain. Thus, the participating countries in this research were the result of partnerships established for these two projects.

Study design

A pooled level analysis of the level of implementation of food, environment policies and infrastructure support for policy development and implementation was undertaken. In addition, key government recommendations were identified and prioritised using an adapted Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI) in eleven European countries: Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain over the period of 2019–2021.

Study procedure

The established Food-EPI tool and process was the framework that guided the study in each country. Slovenia and Portugal aligned the Food-EPI process with the evaluation of national Food and Nutrition action plans.

The Food-EPI tool includes seven policy domains that represent key aspects of food environments—food composition, food labelling, food promotion, food prices, food provision, food retail, and food trade and investment and six infrastructure support domains—leadership, governance, funding and resources, monitoring and intelligence, platforms for interaction and health in all policies. The original tool contains 47 good practice indicators; however, it was adapted to the context of each country and the total numbers of indicators varied but incorporated the directions necessary to improve the healthiness of food environments and to help prevent obesity and diet-related NCDs. The full list of good practice indicators is provided in the Supplementary Material.

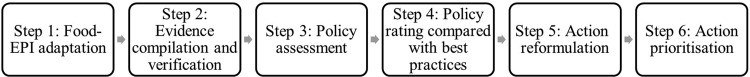

To develop country-specific versions of the Food-EPI, a process of six steps was undertaken (Figure 1). Evidence on the implementation of food policies was collected, summarised in an evidence document, and verified by national governmental officials. Based on this evidence document, the level of implementation of food environment policies was assessed considering the extent of policy implementation and coverage at national level compared to international best practice examples.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the Food-EPI process.

In each participating country, a mixed-methods design was used to rate the level of implementation of policies and infrastructure support and recommended actions were formulated by experts and prioritised according to importance and feasibility.

Participants: National expert panels

Expert panels encompassed academics, public administration officials and NGOs specialized in public health and/or nutrition. They participated in an online or in-person rating survey and workshops or surveys to identify recommendations and their level of priority. Experts were selected based on their area of expertise, ensuring they had the relevant knowledge of nutrition, public health, food research, and/or health policy. Purposive sampling was undertaken to select the experts and invite them to the workshops. A representative number of experts from government, academia, and NGOs was sought to ensure different perspectives and areas of expertise when evaluating the relevant policies. To account for assessment differences an inter-rater reliability assessment (explained in the descriptive analysis section) was undertaken.

Experts needed to consent to take part in the panel and declare the existence of potential conflicts of interest (Supplementary Material). Representatives from industry were excluded in the Food-EPI process except in Finland, where the Finnish Food and Drink Industries' Federation and Finnish Grocery Trade Association participated in the workshops, and in Slovenia, where an umbrella organisation of the national food processors Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia participated in the workshops.

Compilation and verification of evidence document

For each good practice indicator, evidence for the existence and degree of implementation of national policies was collected for each of the participating countries. This evidence included policies, legislations and implemented government programmes. Sources that were searched to collect the evidence included direct government contacts, government websites, and other research related websites. All identified national policies relating to each Food-EPI indicator were summarized into a policy evidence document for each country and verified by governmental officials.

Rating the extent of implementation compared with best practice examples

Experts were provided with rating instructions, the evidence document, and international best practices. The best practice examples included a description of cases where there was a successful implementation of a policy aimed at improving the food environment and preventing obesity and diet-related NCDs in particular countries.

The best practices were selected based on their strength (e.g. using independent nutrient profiling criteria) and comprehensiveness (e.g. including a broad range of age groups, food groups, media, settings or regions). The rating of the extent of policy implementation was carried out based on the comprehensive evidence document, containing details about implementation of policies and actions, validated by government officials, and based on best practice examples from other countries to consider as potential benchmarks or points of reference. The experts compared the evidence of implementation as per the evidence document with the best practice exemplars for a indicator. The best practice examples included description of cases where there was a successful implementation of a policy aimed at improving the food environment and preventing obesity and diet-related NCDs in particular countries.

A five-point Likert scale was used to evaluate the implementation of policies, with 1 = 0–20% implementation (=very low), 2 = 20–40% implementation (=low), 3 = 40–60% implementation (=medium), 4 = 60–80% implementation (=fair), and 5 = 80–100% implementation (=high). Germany was the only country using a four-point Likert scale: non-existent or very low (<25% of implementation); low (25% to <50% of implementation); medium 50% to <75% of implementation); high (75% to <100% of implementation). A ‘cannot rate’ option was also included. The precise number of Food-EPI indicators varied by country; however for this study, 26 policy and 24 infrastructure support indicators were addressed to ensure homogeneity.

Whilst the ratings were subjective and based on expert perception, the experts took the evidence document into consideration in their assessment. Afterwards, inter-rater reliability, or how well experts agree on the assessment, was conducted, also by stakeholder group (academia versus NGO/civil society).

Action and prioritization workshops

One, or more workshops were organized by each country and in some cases, the use of additional online rating surveys (e.g., the Netherlands) were used in the study in which members of the expert panel were asked to identify concrete policy actions for governments on the policy and infrastructure support domains that would improve food environments. The proposed actions were then compiled and prioritized according to their importance and achievability. For importance, countries considered the need (i.e., size of the implementation gap), impact (i.e., the effectiveness of the action on improving food environments and diets), equity (i.e., progressive/regressive effects on reducing food/diet related health inequalities), and other positive and negative effects. For achievability, countries considered the relative feasibility, (i.e. how easy or hard the action is to be implemented); acceptability (i.e. the level of support from key stakeholders including government, the public, public health, and industry); affordability (i.e. the cost of implementing the action); and efficiency (i.e. the cost-effectiveness of the recommended action). In addition, some countries considered the equity aspects of the policy actions.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics of the expert panels in each country were used to characterize the different country expert panels according to sample size, composition, and response rates. Indicator rating means were used to determine an overall percentage of implementation per indicator and domain, categorized into the following levels of implementation: very low (<25%); low (25% to <50%); medium 50% to <75%); high (75% to <100%). Inter-rater reliability of the ratings across experts was measured for each country using AgreeStat 2015.6.2 through the Gwet AC2. Limitations have been associated with the Kappa statistic such as Kappa's tendency to overcorrect for chance-agreement in the presence of high prevalence rates (i.e., highly skewed data). Due to such issues, Gwet proposed a new chance corrected agreement coefficient.

The priority actions for each of the policy and infrastructure support domain sub-components were calculated as the proportion of the total number of prioritized actions in each country. We identified the level of implementation of the Food-EPI indicators (very low, low, medium, high) for each of the recommended priority actions by experts. This allowed the identification of the prioritized actions which targeted policy or infrastructure implementation gaps in each country. The top policy and infrastructure support actions in each country were extracted and compared.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the article.

Results

Characteristics of experts and response rates across countries

The number of experts in each panel ranged from 9 in Estonia to 55 in Germany. Response rates were around 50% in most of the countries, although this was substantially higher for Germany (76%) and Portugal (66%) and lower for Poland (33%), Slovenia (27%), and Estonia (20%). The expert panels across the countries were varied, with proportion of experts from academia ranging from 12% (Finland) to 76% (Poland) and percentage of experts from NGO and other organizations ranging from 30% to 52%, and the percentage of policy experts ranging from 0% to 56% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of expert panels across European countries implementing the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (2020-2021).

| Country | Year | Experts invited(N) | Response rate ratingsN (%) | AcademiaN (%) | NGO & other civil society organizationsN (%) | Policy experts or other stakeholdersN (%) | Response rate actionsN (%) | Response rate prioritizationN (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonia | 2020–21 | 46 | 9 (20) | 14 (30) | 24 (52) | 8 (17) | 9 (20) | 9 (20) |

| Finland | 2020 | 57 | 34 (60) | 7 (12) | 18 (32) | 32 (56) | 24 (42) | 29 (51) |

| Germany | 2019–20 | 72 | 55 (76) | 29 (53) | 15 (27) | 11 (20) | 37 (67) | 29 (53) |

| Ireland | 2019 | 40 | 20 (50) | 8 (40) | 8 (40) | 4 (20) | 17 (85) | 19 (95) |

| Italy | 2021 | 12 | 12 (40) | 17 (58) | 13 (42) | 0 (0) | 12 (40) | 12 (40) |

| the Netherlands | 2020 | 52 | 28 (54) | 12 (43) | 10 (36) | 6 (21) | 28 (100) | 21 (75) |

| Norway | 2019 | 80 | 38 (48) | 24 (63) | 10 (26) | 4 (11) | 34 (89) | 21(55) |

| Poland | 2020 | 63 | 21 (33) | 16 (76) | 4 (19) | 4 (19) | 11 (52) | 11 (52) |

| Portugal | 2021 | 32 | 21 (66) | 14 (43) | 17 (52) | 2 (5) | 15 (47) | 13 (41) |

| Slovenia | 2021 | 70 | 19 (27) | 19 (27) | 21 (30) | 30 (43) | 21 (30) | 21 (30) |

| Spain | 2021 | 50 | 31 (62) | 18 (36) | 26 (52) | 6 (12) | 28 (56) | 28 (56) |

Inter-rater reliability assessment

The inter-rater reliability, measured through the Gwet AC2, for the Food-EPI rating process was lowest in Slovenia (0·29; 95%CI = 0·17–0·40), followed by Ireland (0·38; 95%CI = 0·19–0·58), Poland (0·36; 95%CI = 0·35–0·38), Norway (0·37; 95%CI = 0·28–0·46), Portugal (0·40; 95%CI = 0·29–0·50), Italy (0·44; 95%CI = 0·25–0·63), Finland (0·45; 95%CI = 0·35–0·55), Spain (0·49; 95%CI = 0·39–0·59), Estonia (0·52; 95%CI = 0·39–0·64), the Netherlands, (0·57; 95%CI = 0·51–0·62), and Germany (0·64; 95%CI = 0·58–0·69).

Level of implementation of policies on food environments and infrastructure support for policy development and implementation

Table 2 presents examples of high level policy or infrastructure implementation. All countries scored better on the implementation of infrastructure support than on the implementation of policies to create health-promoting food environments. Of all policy domains, ‘retail’ was rated with the lowest level of implementation compared to the other policy domains, and ‘health in all policies’ was rated with the lowest level of implementation for the infrastructure support domain (Table 3).

Table 2.

Examples of high level policy implementation.

| Domain | Example |

|---|---|

| Policies | |

| Food composition | In Finland, the Decree of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry on declaring certain foods high-salt (10/2014), food packaging must be labelled as "high salt" or "high in salt" if the salt content of the food is exceeded. Government Decree (54/2012) on the criteria for supporting the meals of university students: granting of a state subsidy to student restaurants to reduce the price of a student meal (meal-specific subsidy). The prerequisite is e.g., that the student meal meets general health and nutritional requirements. Finland has developed a Nutrition Commitment, which is a tool for food sector and industrial food product design. The voluntary nutrition commitment can be made in eight different content areas that are subject to key change objectives in the nutrition recommendation. In Portugal, an extended commitment to reformulate salt, sugar, and trans fatty acids content in different food product categories was signed in May 2019. The protocol was established between the Directorate-General of Health, the National Health Institute, the Portuguese Association of Distribution Companies, and the Federation of the Portuguese Agri-Food Industry. |

| Food labelling | Low level of implementation among all countries. |

| Food marketing | In Portugal, the Law No. 30/ 2019 of 23 April introduces restrictions on advertising to children under 16 years old of food products and drinks containing high energy value, salt, sugar, saturated fatty acids, and trans fatty acids content. The law covers schools, public playgrounds and a 100 m-radius around these places; television, on-demand media services, and radio, in the 30 minutes preceding and following children's programmes, as well as programmes with an audience of at least 25% below 16 years old; cinemas, in movies for children under 16; and websites, social networks, and mobile applications where the contents are intended for children under 16 years of age. The food and beverage products must meet the nutritional criteria defined in the Portuguese Nutrient Profile Model, developed by the Directorate-General of Health, based on WHO Regional Office for Europe Nutrient Profile Model. |

| Food prices | From February 2017, Portugal implemented an excise duty on drinks containing added sugar or other sweeteners. The revenue from the application of the tax is allocated to the National Health Service Budget. The Law No. 71/2018 of 31 December - State Budget for 2019 - introduced a revision to this tax, creating new taxation tiers to allow this measure to continue encouraging food industry to reduce sugar in these drinks. |

| Food provision | In Finland, national nutrition guidelines exist for several population groups (for example: for early education, schools, and for elderly) and several voluntary support tools like Heart Symbol in healthy foods, nutrition commitment for industry, and other stakeholders as well as the School Lunch Diploma are at place. Portugal has legislation on food provision in school and on food supply for Healthcare Institutions. In 2016, the Order No. 7516-A/2016 determined the conditions for the limitation of unhealthy products in vending machines, available in the institutions of the Ministry of Health. By the end of 2017, the Order No. 11391/2017 extended the limitation of unhealthy products based on the nutritional profile defined by the National Healthy Eating Promotion Program to bars, cafeterias, and buffets, in the same institutions. More recently, in August 2021, the Order No. 8127/2021 extended the limitation of unhealthy products to school buffets and vending machines of public educational establishments of the Ministry of Education. |

| Food retail | Low level of implementation among all countries. |

| Infrastructure Support | |

| Leadership | According to the Constitution of Finland Public Authorities shall ensure adequate social and health services for all and promote the health of the population. Health Care Act's 30·12·2010/1326 purpose is to promote and maintain the health, well-being, ability to work and function and social security of the population and reduce health inequalities between population groups. Finland has national nutrition guidelines for several population groups (for example for early education, schools, and for elderly). Portugal has, since 2017, an Integrated Strategy for the Promotion of Healthy Eating, that was published by an Order of the Assistant Secretary of State for Health, the Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Rural Development, the Minister of the Sea, the Secretary of State for Fiscal Affairs, the Secretary of State for Local Authorities, the Secretary of State for Education, the Assistant Secretary of State for Commerce, the Secretary of State for Industry, and the Secretary of State for Tourism (Order No. 11418/2017, of 29 December). This strategy aims to place ‘healthy eating in all public policies” and has the mission to encourage adequate food consumption and the consequent improvement of the nutritional status of citizens, with direct impact on the prevention and control of chronic diseases. |

| Governance | Finnish legislation's (e.g., Administrative Law 434/2003, Act on the Publicity of the Activities of Authorities. 21·5·1999 / 621) purpose is to implement and promote good governance and legal security in administrative matters and to promote the quality and efficiency of administrative services. National nutrition recommendations are based on a joint Nordic scientific assessment of the evidence and are published on the website. Finland also have Current Care Guidelines, e.g., for obesity. Recommendations are independent and research based. |

| Monitoring | In Finland, several approaches and supporting mechanisms to monitor nutrition such as national food composition data base, national health examination surveys for adults to monitor overweight and food habits, surveys/questionnaire surveys to assess food habits of both adults and children and national register data on children's weight and height exist. |

| Funding | Low level of implementation among all countries. |

| Platforms | The Finnish government program coordinates and commits various branches of government and actors. Legislation, e.g., Health Care Act 30.12.2010/1326 obliges the various sectors of the municipality to cooperate in promoting health and well-being. Finland has advisory boards, e.g., National Nutrition Council and Public Health Advisory Board. |

| Health in all policies | In Finland, the principle of Health in all policies must be considered in all decision-making. All legislation must consider the assessment of the effects of laws on the health and well-being of the population. |

Table 3.

Level of policy and infrastructure support implementation in European Countries.

|

Level of implementation (very low 0<25% (dark red); low 25<50% (red); medium 50<75% (yellow); high 75<100% (green), compared to international best practices for the Food-EPI policy and infrastructure support domains.

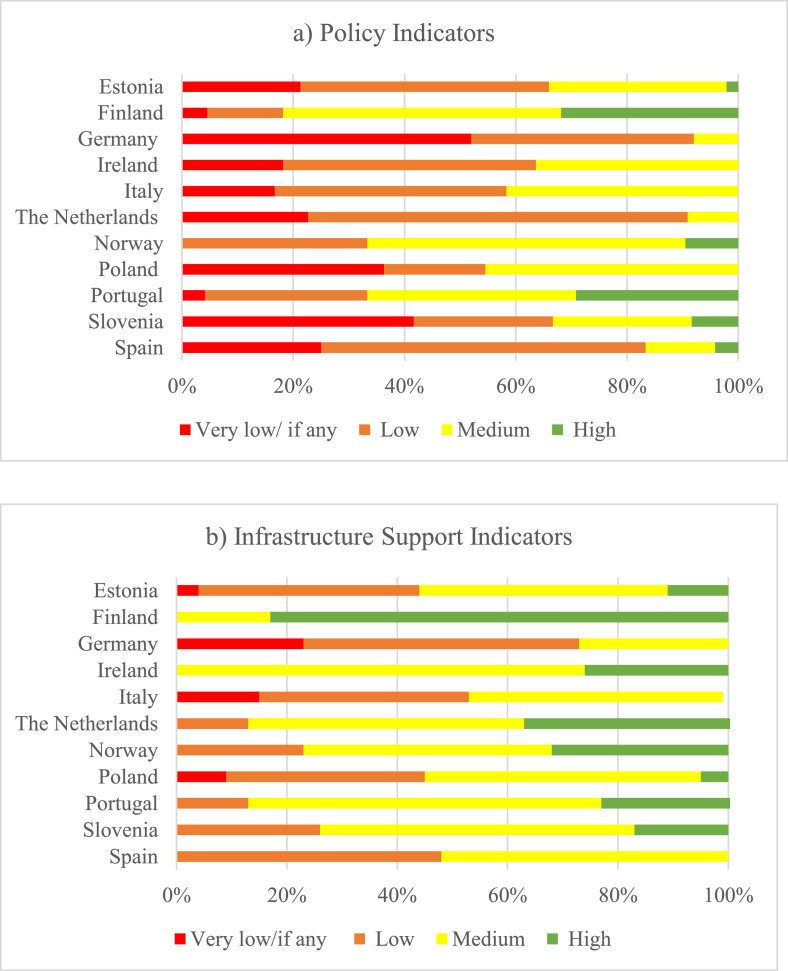

Most countries had either ‘very low if any’ or ‘low’ implemented policy indicators (Figure 2a). Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Poland had no indicators ranked as ‘high’. Unlike the other countries, none of the Norwegian policies were scored as ‘very low if any’ implementation. Noticeably, Slovenia and Poland had the highest proportion of policy indicators rated as “very low/if any” while Germany (64%, n = 15), the Netherlands (68%, n = 16) and Spain (58%, n = 14) had the highest proportion of policy indicators with a ‘low’ implementation. Finland, Norway, and Portugal had the highest proportion of policy indicators with ‘high’ implementation (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Proportion of policy (a) and infrastructure support (b) indicators with 'very low if any', 'low', 'medium' or 'high' implementation in each country compared to international best practices.

When categorizing the indicator scores to level of implementation compared to international best practice regarding the infrastructure domains (Figure 2b), most countries had a ‘medium’ level of implementation. It is noticeable that all Finnish and Irish infrastructure support indicators were either rated at ‘medium’ or ‘high’ implementation. In Germany, Italy, and Spain, none of the infrastructure support indicators were rated at a high level of implementation. In four of the countries (Estonia, Germany, Italy, and Poland), at least one infrastructure support indicator was rated as “very low/if any”.

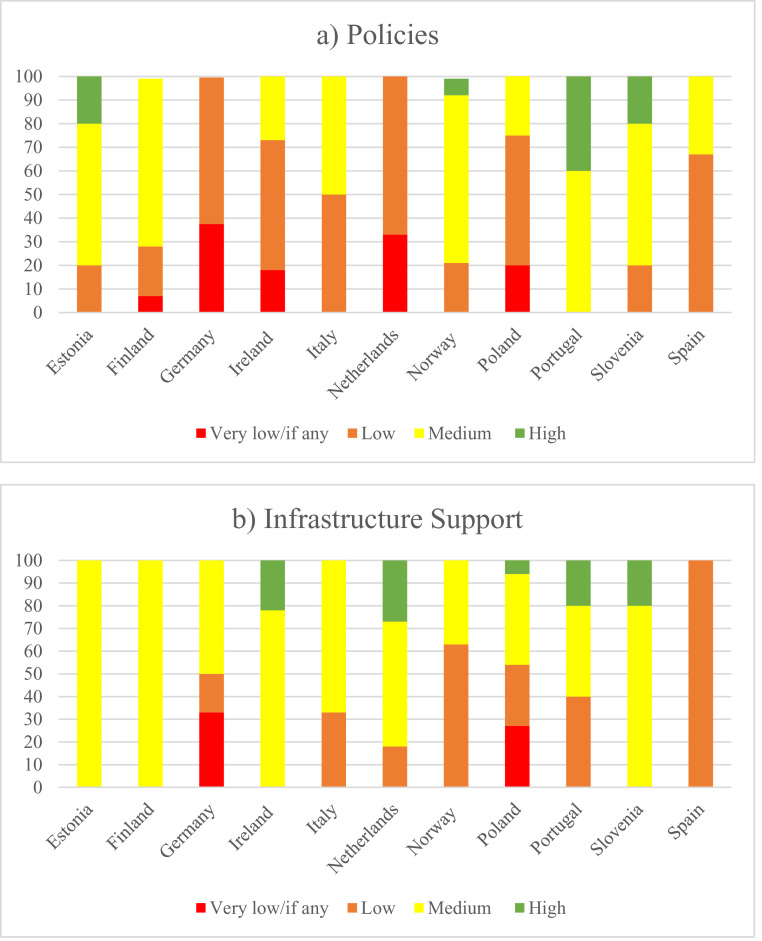

Proposed and prioritized policy and infrastructure support actions

Figure 3a illustrates the recommended policy actions as a proportion of the total number of actions prioritized in each country. In most countries, most actions recommended were related to food provision policies: Estonia (63%), Ireland (27%), Italy (20%), Germany (38%), Poland (28%), and Slovenia (40%). Noticeable, some countries actions were proposed related to all policy domains (e.g., Finland, Ireland, Germany, Norway, Poland), whereas in other countries' fewer domains were dominant (e.g., Estonia, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Slovenia).

Figure 3.

Actions in each sub-component of the policy (a) and infrastructure support (b) domains expressed as a proportion of the total number of actions (in brackets) prioritized in each country. COMP: Food composition; LABEL: Food labelling; PROMO: Food promotion; PRICE: Food prices; PROV: Food provision; RETAIL: Food retail; TRADE: Food trade and investment; LEAD: Leadership; MONIT: Monitoring and assessment; FUND: Funding and resources; PLAT: Platforms for interaction; HIPA: Health in all policies.

Figure 3b illustrates the recommended infrastructure support actions as a proportion of the total number of infrastructure support actions prioritized in each country. In the Netherlands, Norway, Ireland, and Germany, actions were proposed related to all infrastructure domains. Estonia only proposed actions related to funding, while in half of the participating countrie's actions related to health in all policies were proposed.

Across policy and infrastructure support domains, the total number of actions prioritized varied from 5 to 40 per country. Across the total of 212 actions proposed for policy and infrastructure support, 32 were for food provision, 21 were for food promotion, 12 for food composition, 16 for food labelling, 22 for food prices and 21 for food retail. Regarding infrastructure support domains, 15 were for funding, 17 for governance, 18 for leadership, 19 for monitoring, 9 for platforms for interaction, and 9 were for health in all policies (Supplementary Material).

For all countries most of the prioritized policy actions were for indicators which were rated at either low (20–33%) or medium (20–67%) level implementation, while Slovenia, Estonia, and Portugal (20–40%) also proposed some actions for indicators which were already rated at the level of best practice. Similar results were found for the priority actions related to infrastructure support across countries (Figure 4a, b and Supplementary Material).

Figure 4.

Proportion of priority actions for policy (a) and infrastructure support (b) indicators rated at different levels of implementation using the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index.

Countries focused mainly on targeting healthy food provision particularly in school settings, regulating food promotion and marketing especially to children, and to implement unhealthy food and beverage taxation systems. Table 4 and Table 5 list the top policy and infrastructure support actions prioritized in each country.

Table 4.

The top prioritized policy actions for each participating country.

| No. | Priority actions | Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Finlanda | ||

| 1 | Making the nutritional quality of a meal a requirement for a tax-subsidized lunch or food benefit. | Composition |

| 2 | Exploring the possibility of introducing a national mandatory labelling system for packaged foods on the front of the food packaging, indicating the nutritional value of the product and a mandatory national (the Heart Symbol or similar) nutrition labelling system in fast food restaurants to communicate nutritionally better meal options. | Labelling |

| 3 | Exploring the possibilities for national legislation and enforcement of such legislation and self-regulation regarding the marketing of unhealthy foods to children. Prohibiting the marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children by law. Investigating children's exposure to the marketing of unhealthy foods in the digital environment. Adding the use of minimum nutritional quality requirements as a procurement criterion in the supplement of the state contribution of the promotion of well-being and health used for municipalities and provinces. Monitoring children's exposure to the marketing of unhealthy foods in different operational environments. | Promotion |

| 4 | Exploring fiscal measures and other measures that would allow the price of vegetables to fall. Introducing a health-based taxation on food/foodstuff. | Prices |

| 5 | Restricting the sale and supply of unhealthy foods by legislative means in the living environment of young people and children, such as at school and in hobbies. Developing recommendations and guidelines for grocery stores to create a selection environment conducive to health-promoting choices, for example through product placement and presentation. |

Retail |

| 6 | Encouraging the food industry and public / private food service operators to improve the nutritional quality of their products by adopting the use of the Heart Symbol. Exploring the possibilities of making the Heart Symbol system free of charge for users. Clarifying the legislation regarding the criteria for free school and student meals so that it would be mandatory to take nutrition recommendations into account. | |

| Irelandb | ||

| 1 | Implement nutrition standards for all schools including tuck shops operating therein. All school-based health promotion programmes should be delivered by health professionals. An inter-school nutrition forum should be established on the promotion of healthy food choices within the school environment, with support from appropriate governing bodies. | Provision |

| 2 | Establish a committee with a cross-governmental structure to monitor and evaluate food-related income support programmes for vulnerable population groups. | Prices |

| 3 | Ringfence revenue from tax on unhealthy foods to improve public health initiatives and provide healthy food subsidies targeted at disadvantaged groups in the community. | Prices |

| 4 | Introduce zoning legislation “No Fry Zones” to prohibit the placement of unhealthy food outlets within 400m of primary and secondary schools. | Retail |

| 5 | Implement a comprehensive policy on nutrition standards for food and beverage provision in public sector. Monitoring of existing policies and guidelines for effectiveness in provision and promotion of healthy food choices should be conducted. | Provision |

| Germanya | ||

| 1 | Mandatory, publicly funded implementation of the nutrition standards of the German Nutrition Society in schools and kindergartens and waiving of fees for parents. The nutrition standards include specifications for the main meals offered, other food and beverages available on the school premises, characteristics of the dining rooms and the arrangement of communal meals. Furthermore, it includes the provision of sufficient financial resources (e.g., under a federal investment program), professional support, and training opportunities. | Provision |

| 2 | Reduced value-added tax rate on healthy foods and increased value-added tax rate on unhealthy foods. | Prices |

| 3 | Introduction of a tax on SSBs based on sugar content and use of the revenue for health promotion (e.g., improvement of catering for school and day-care). | Prices |

| 4 | Ban on advertisement of unhealthy foods directed at children, including all forms of advertising (television, internet, print and outdoor advertising, point-of-sale advertising, direct marketing, packaging, and advertising in kindergartens, schools, playgrounds and other sports and recreational facilities frequented by children) and based on an appropriate nutrient profile model (e.g., the model of the WHO European Regional Office). | Promotion |

| 5 | Mandatory implementation of the nutrition standards of the German Nutrition Society in public institutions, such as public offices, clinics, senior citizen facilities and universities. The nutrition standards include specifications for the main meals offered, other food and beverages available on the school premises, characteristics of the dining rooms and the arrangement of communal meals. Furthermore, it includes the provision of sufficient financial resources (e.g., under a federal investment program), professional support, and training opportunities. | Provision |

| The Netherlandsb | ||

| 1 | Ensure that the new product improvement system, in continuation of the agreement on product composition improvement, meets at least the following requirements:

|

Composition |

| 2 | Ban all forms of marketing (Article 1 of the Dutch Advertising Code) aimed at children under the age of 18 years old for foods that fall outside the Dutch healthy dietary guidelines (i.e., the Wheel of Five) (an advertisement is aimed at children when the advertisement reaches an audience consisting of 10% children under 18 or more), via:

|

Promotion |

| 3 | Increase the prices of unhealthy foods such as sugar-sweetened beverages, for example via a proven effective VAT-increase or excise tax. | Prices |

| 4 | Formulate clear rules and regulations for caterers, quick service restaurants, supermarkets, and shops to increase the relative availability of healthy foods (with sufficient fibre, vitamins, and/or minerals) compared to the total food product availability. | Retail |

| 5 | Decrease the prices of healthy foods such as fruit and vegetables, for example by reducing the VAT to 0% (when this is possible with the new European legislation). | Prices |

| 6 | Finance food-related income support, for example by providing vouchers to people below a certain income level to purchase healthy foods free of charge (such as fruits and vegetables, such as the Healthy Start programme in the UK). | Prices |

| Norwayb | ||

| 1 | Actively use fiscal policies to shift consumption from unhealthy to healthy foods. This includes to:

|

Prices |

| 2 | Step up efforts to create healthy food environments and make healthy choices easy in public settings. This includes to:

|

Provision |

| 3 | Order all municipalities to offered a simple school meal (which at least consists of free school fruit), with room for local adaptation and with state part-financing. | Provision |

| 4 | Demand clearer results in the ongoing public-private partnership (Letter of Intent with the food sector) to achieve the goals set in the agreement and make food stores healthier. This includes to:

|

Retail |

| 5 | Introduce a legal regulation of the marketing of unhealthy food and drink targeting children. Or alternatively, put pressure on the industry so that the guidelines in the Food Industry Professional Committee (MFU) become stricter than today and are, to a greater extent, in accordance with WHO recommendations. The latter will involve a re-assessment of the exceptions in the MFU guidelines regarding packaging, placement in supermarkets, and sponsorship. |

Promotion |

| Polanda | ||

| 1 | Introduce a clear and simple labelling system for food products, including information on salt/sugar/trans fats. | Labelling |

| 2 | Prepare the emission of information campaigns that are thoroughly prepared from the sociological and psychological point of view, preceding the introduction of food policy regulations. | Promotion |

| 3 | Modify the Ordinance of the Minister of Health on groups of foodstuffs intended for sale to children and adolescents in education system units and the requirements to be met by foodstuffs used as part of mass nutrition of children and adolescents in these units, in a way that specifies requirements consistent with nutritional requirements and recommendations. | Provision |

| 4 | Modify school curricula by adding a subject or at least a compulsory thematic block “nutritional education”. | Provision |

| 5 | Change the VAT matrix in a way that unequivocally promotes low-processed foods and healthy food choices. | Prices |

| Estoniaa | ||

| 1 | Training client servants on nutrition. | Provision |

| 2 | Support and incentivise businesses to improve availability, placement, and prominence of healthy foods in stores and services. | Retail |

| 3 | Restricting the advertising of products high in saturated fat, sugar, and energy content through different media and settings. | Promotion |

| 4 | Promote the advertising of healthy food options, in particular raw materials like fresh fruit and vegetables. | Promotion |

| 5 | Provide campaigns, practical guidelines, tools, training, and instructions to support healthy food choices by the general public. | Funding |

| Sloveniaa | ||

| 1 | Maintaining and upgrading school nutrition. | Provision |

| 2 | Improving the situation on student nutrition (new guidelines, vouchers). | Provision |

| 3 | Employment, training, and education of staff in public institutions in the field of nutrition. | Provision |

| Spaina | ||

| 1 | Current standards require improvement. According to the WHO criteria should be more ambitious and be aligned to products that are most consumed and available in Spain, and according to their nutritional information. Monitoring of the progress in the establishment of these standards should be carried out. | Composition |

| 2 | To implement a clear mandatory front of pack labelling system. | Labelling |

| 3 | To implement plain packaging policies and ban the use of cartoons or celebrities as well as food endorsement for unhealthy foods. | Promotion |

| Italya | ||

| 1 | Upgrading school menu. | Provision |

| 2 | Reformulation of food products. | Composition |

| Portugalb | ||

| 1 | Extend the plan in force in Portugal regarding the food products reformulation, involving the food service outlets. This plan should encompass the definition of short and medium-term priorities and objectives. | Composition |

| 2 | Reduce taxes on healthy foods (pulses, fruit, and vegetables). | Prices |

| 3 | Define a nutrient profile model which will work as the foundation for the implementation of measures to promote healthy eating environments (food products reformulation, taxation of unhealthy foods, among others). | Composition |

| 4 | Ensure the effective implementation of the existing guidelines for food provision in schools by defining a model to monitor the compliance with the standards/guidelines in place. | Provision |

| 5 | Propose an amendment to the Value Added Tax (VAT) to include other criteria for assigning VAT rates. Besides the criteria of essentiality, it is proposed to consider the food products’ nutrient profile and/or their inclusion in a healthy dietary pattern. | Prices |

Prioritization based on importance and achievability.

Prioritization based on importance, achievability, and equity.

Table 5.

The top prioritized infrastructure support actions for each participating country.

| No. | Priority actions | Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Finlanda | ||

| 1 | Interfering the lobbying in the food environment. | Governance |

| 2 | Launching a national nutrition monitoring for children and young people. | Monitoring |

| 3 | Funding the research of monitoring the implementation of nutrition recommendations and research related to it. The development of a holistic and health-promoting nutrition is considered in research funding priorities. Integrating a nutrition guidance and low-threshold lifestyle groups into service activities provided by social services and non-profit organizations. Taking the financial possibilities for healthy eating into account in families with children when assessing the need for social benefits. |

Funding and resources |

| 4 | Investing in long-term sustainability in funding systems for research on the food environment and NCDs. | Funding and resources |

| Irelanda | ||

| 1 | Create a committee which monitors implementation of policies and procedures that ensure open and transparent approaches in the development and reviewing of food and nutrition policies and within the legislative process. | Governance |

| 2 | An Taoiseach to demonstrate visible leadership and commitment to the “Obesity Policy and Action Plan 2016-2025 (OPAP)” and commit to garnering cross-party support for the policy. | Leadership |

| 3 | Establish a formal platform between government and civil society - encompassing community groups, NGOs, academia, and The Citizens’ Assembly to increase engagement and participation in the planning and implementation of food and public health policies. | Platforms for Interaction |

| 4 | Establish a forum consisting of local and national government, policy experts, public health experts, and academia to facilitate information-sharing and knowledge transfer. The forum would identify priority areas and implement evidence-based policies to improve the food environment and population health outcomes. | Platforms for Interaction |

| 5 | The government to prioritize an evidence-informed national food and nutrition policy with explicit consideration given to the health impacts on vulnerable groups in Ireland and the determinants of health. This requires cross-departmental commitment to reducing health inequalities. | Health in all policies |

| No. | Germanya | |

| 1 | Improved evaluation of existing and planned measures for the promotion of healthy nutrition, by providing financial resources and creating appropriate structures for independent and scientifically based evaluations. | Monitoring and intelligence |

| 2 | Improved monitoring of dietary behaviour and status through the provision of sufficient funding for regular, comprehensive, and nationally representative surveys of dietary behaviour and status (including body weight, purchasing and food preparation, food culture, and nutrition literacy), with particular attention to risk groups and reducing social inequalities. | Monitoring and intelligence |

| 3 | Improved exchange of knowledge and experiences and improved cooperation between policy, practice, and science by creating appropriate structures and procedures. | Platform for interaction |

| 4 | Strengthen nutrition-related content in the education of relevant professional groups, including educators, teachers, physicians, medical assistants, and nurses. | Funding and resources |

| 5 | Improved monitoring of food environments, including monitoring of the nutritional composition of processed foods, the extent of food advertising, food prices, and food availability in selected settings (including kindergartens, schools, universities, company cafeterias, hospitals, rehabilitation clinics, retirement homes, meals on wheels, and food banks). This includes providing sufficient financial resources for regular and close-meshed, comprehensive, and nationally representative surveys. | Monitoring and intelligence |

| No. | The Netherlandsb | |

| 1 | Develop a government-wide national prevention policy and implementation plan containing universal, selective, indicated, and care-related prevention measures, aimed at, among other things, healthy food consumption and the reduction of diet-related (chronic) diseases among the entire population. Address the physical, socioeconomic, and digital living environment so that it contributes to the promotion of health and underlying socioeconomic determinants of unhealthy food consumption (e.g., poverty, stress). Make all ministries co-owners of this policy and encourage the collaboration between the ministries in this field. | Leadership |

| 2 | Support local governments with developing and implementing prevention measures aimed at a healthy food consumption, a healthy food environment and the reduction of diet-related (chronic) diseases. | Platforms for interaction |

| 3 | Develop concrete, measurable targets regarding prevention measures (preferably integrated in a national prevention policy), aimed at a healthy food consumption, a healthy food environment and the reduction of diet-related (chronic) diseases, which can be tested by an independent organization (RIVM) and make the total overview of the achieved and not achieved results on these targets publicly available. | Monitoring and intelligence / Governance |

| 4 | Increase the budget for universal, selective, indicated, and care-related prevention in the national budget, with at least 10% of the health care budget going to prevention in the first four years and gradually reversing the financing pyramid for health care (with most of it going to prevention instead of curative care). | Funding and resources |

| 5 | Develop an instrument for reporting about the food availability in supermarkets, shops, quick service restaurants, and catering that shows the share of healthy foods in relation to the total food product range, and make binding agreements with the involved parties (local governments, schools, hospitals, food producers etc.) about monitoring and reporting thereof. | Monitoring and intelligence |

| No. | Norwayb | |

| 1 | Demonstrate clear, knowledge-based, and coherent political leadership in public health and nutrition policies This includes to:

|

Leadership |

| 2 | Ensure that there is access to qualified nutrition and food competence in the public sector.This means that the authorities:

|

Funding and resources |

| 3 | Ensure that nutrition is strengthened as part of public health actions and that "health in all policies" is implemented at all levels.This includes to:

|

Health in all policies |

| 4 | Monitor the compliance with the national Norwegian Guidelines for Food and Meals in schools, kindergartens, and after-school clubs, including in school canteens and kiosks. | Monitoring and intelligence |

| 5 | Ensure long-term financing of effective and health promoting nutrition and public health work in counties and municipalities.This includes to:

|

Funding and resources |

| Polanda | ||

| 1 | Introduce a system of trainings on the healthy eating rules addressed to people responsible for feeding children (including cooks, authorizing officers, parents). | Governance |

| 2 | Promotion of the principles of healthy eating using the marketing tools, media campaigns, and influencers. | Governance |

| 3 | Introduce reimbursed dietitian services at the level of primary health care and specialist care. | Funding and resources |

| 4 | Regulate in a legal manner the profession of dietitian. | Governance |

| 5 | Facilitate the availability of fruit and vegetables in schools and workplaces. | Leadership |

| Italya | ||

| 1 | Education of the general population on a healthy and balanced diet. | Governance |

| 2 | Increase funding for nutrition. | Funding and resources |

| Spaina | ||

| 1 | Mandatory industry regulation should be established as current strategies are based on voluntary regulations which have not worked. | Leadership |

| 2 | To develop monitoring systems for the monitoring of food composition and promotion of unhealthy foods in the media. | Monitoring |

| Sloveniab | ||

| 1 | Strengthening communication with the public. | Governance |

| 2 | Improving cooperation mechanisms. | Platform for interaction |

| Estoniaa | ||

| 1 | Provide campaigns, practical guidelines, tools, training, and instructions to support healthy food choices by the public. | Funding and resources |

| Portugala | ||

| 1 | Strengthen the strong and visible political support to improve food environments, to improve population nutrition, and to prevent and control diet-related NCDs and their inequalities. | Leadership |

| 2 | Include the healthy eating promotion programme in the basic portfolio of primary healthcare services. | Funding and resources |

| 3 | Set indicators for regular monitoring of dietary intake, nutritional status and health outcomes related to food and nutrition. (MONIT 2 and 3). | Monitoring and intelligence |

| 4 | Improve the nutrition and public health workforce by adjusting the ratio of nutritionists in Primary Health Care and by integrating at least one nutritionist in each Public Health Unit at primary health care level. | Funding and resources |

| 5 | Include, in national programmes on nutrition and healthy eating, the most vulnerable population groups, namely the elderly, pregnant women, children, adolescents, and immigrants, as priority action groups. | Leadership |

Prioritization based on importance and achievability

Prioritization based on the action's importance achievability and its contribution to equity

Policy actions

In all countries, except Poland, Estonia, Slovenia and Spain, the top recommended actions for national governments included the implementation of price increases on unhealthy foods and beverages. Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, Finland, and Portugal prioritized recommended actions on lower healthy food prices. Ireland and the Netherlands recommended to support food-related income support among vulnerable populations as a top priority recommendation (Tables 3 and 4).

Regarding food provision, experts in Ireland, Germany, Norway, Poland, Slovenia, Italy, and Portugal prioritized recommended actions concerning the implementation of nutrition standards in schools, including the provision of healthy school meals and foods. Ireland, Germany, and Poland proposed adequate school-based health promotion/nutrition-education, and experts in Ireland, Germany, Norway, Slovenia, Italy, and Portugal prioritized the recommendation of implementing standards for nutrition provision in public sectors/institutions, including in schools. Regarding food provision, in the Netherlands, experts recommended as a top priority action the formulation of clear rules and regulations concerning increased availability of healthy foods for food retailers, quick service restaurants, caterers, and other out-of-home settings.

In Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Estonia, Finland, and Spain, recommendations focused on food promotion actions which included the banning of marketing of foods for children that fall outside the healthy dietary guidelines. Polish experts proposed to develop information campaigns to explain the introduction of food policy regulations using a socio-ecological and psychosocial approach.

Irish, Norwegian, Finnish, and Estonian experts prioritized actions in relation to food retail environments including for example the introduction of zoning legislation for ‘no fry zones’, to prohibit the placement of unhealthy food outlets within 400 metres of primary and secondary schools in Ireland, and a demand for clearer results in the ongoing public-private partnership to achieve goals to make food stores healthier in Norway.

Polish, Spanish, and Finish experts prioritized the introduction of a clear front-of-pack labelling system. In the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, and Portugal, experts prioritized a top action concerning food composition, recommending the reformulation and more ambitious targets and standards.

Infrastructure support actions

Regarding infrastructure support, experts in Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, and Spain prioritized recommended actions regarding leadership (Table 4). In Ireland, Norway, and Portugal, experts recommended to demonstrate leadership and commitment to obesity prevention and public health policies, whereas in the Netherlands experts recommended to the development of a government wide national prevention agreement and implementation plan. At a more practical leadership level, Polish experts recommended to show leadership by increasing the capacity of people responsible for facilitating the availability of healthy foods in schools and workplaces. Spanish experts recommended to show leadership by means of mandatory industry regulations. In Portugal, experts recommended including the most vulnerable population groups as priority action groups in national programmes on nutrition and healthy eating.

In Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Finland, Italy, and Estonia, experts included recommendations in the top priority actions in the areas of funding & resources. Germany, Norway, and Poland recommended to the allocation of funding and resources to implement nutrition education in curricula of all relevant professions (Germany), nutrition competence in the public sectors (Norway), provide campaigns and tools for the public (Estonia), for nutrition in general sense (Italy), or to reimburse dietician services (Poland). Dutch experts recommended the national government to increase their budget for prevention as proportion of the national health care budget. Portuguese experts recommended including the healthy eating promotion programme in the basic portfolio of primary healthcare services, while improving their nutrition and public health workforce.

Experts in Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, Norway, Spain, and Finland recommended actions regarding monitoring in their top prioritized actions. In Germany, experts recommended to improve the evaluation of existing and planned measures for the promotion of healthy nutrition in general, whereas in Norway, this recommendation was targeted at monitoring compliance with the national Norwegian guidelines for food for children in all relevant settings.

Portuguese and Finish experts recommended to set indicators for regular monitoring of dietary intake and nutritional health outcomes. Monitoring the status of the food environments was a top prioritized recommended action by experts in Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, this recommendation targeted food stores and caterers. Dutch experts also recommended to make agreements with involved stakeholders about a monitoring structure and to develop measurable targets to gain insight into the implementation of policies aimed at improving food environments.

Platforms for Interaction was included in the top priority action areas in Ireland, Germany, the Netherlands, and Slovenia. Experts in Ireland and Germany recommended actions to establish engagement and knowledge transfer between government, civil society, and public health experts (Ireland) and policy, practice, and research (Germany). Dutch experts recommended national policy makers to support local governments with developing and implementing prevention measures. Slovenian experts recommended to improve cooperation mechanisms.

In Ireland, Poland, Slovenia, Italy, and Finland actions related to governance were included in the top recommended priority actions. In Poland, three of the top recommended prioritized actions related to governance. Polish experts recommended to broaden community participation when formulating healthy eating policies for children, the inclusion of marketing principles when formulating health promotion campaigns, and legislation of the regulation of the dietitian profession. In Ireland, prioritized action included the adoption of open and transparent approaches by the national government in the development and reviewing of nutrition policies and within the legislative process. In Finland, experts recommended to interfere lobbying in the food environment. Italian and Slovenian experts recommended to strengthening either education or communication.

Experts in Ireland and Norway identified actions related to health in all policies in their top prioritized actions. In Ireland, this addressed the recommendation to obtain a cross-departmental commitment to reducing diet-related health inequalities. In Norway, it addressed the use of health impact assessments of all policies that may impact the food environment or public health nutrition as well as requirements for local level policy makers.

Discussion

This is the first study assessing the level of food environment policy and infrastructure support implementation while identifying priority actions in European countries. In the 11 participating countries, infrastructure support systems were implemented to a larger extent than policies directly related to improving food environments. Apart from Finland, Norway, and Portugal, all countries had predominantly ‘low’ to ‘very low’ implementation scores for policies which directly shape food environments.

The results of this study are consistent with the Food-EPI study conducted in the EU and top priorities align with the priorities of national countries.23 While experts in each of the countries explicitly formulated and prioritized actions to improve food environments and public health nutrition, and to prevent diet-related NCDs for their national governments, this study highlights some shared key top prioritized action areas among the included European countries (Tables 3 and 4). While we highlight the top priority areas in each country, all recommended actions, which have been identified for the countries by means of this research project, should be considered collectively and should not be seen as stand-alone actions (Supplementary Material).

Prior studies indicated that there is a preference for the majority of countries to implement evidence-based policies to prevent NCDs;24 however, the implementation of preventive policies remains relatively low, and progress is slow, though some small improvements have been observed in recent years. Monitoring studies should specifically address government actions on food environments which is consistent with the results of the present study.24

School food environments have previously been associated with spaces that can provide children with the opportunity to develop healthy dietary patterns that can be transferred into adulthood.25 In this study, many participating countries highlighted the importance of focusing on the improvement of school food environments. European countries specifically highlighted the need to regulate marketing to children and the introduction of nutrition and food-related subjects in educational institutions. Countries also indicated the importance of the provision of healthy school meals and to regulate and monitor food procurement.

Regarding the recommendation to regulate food marketing, especially towards children, successful lessons can be taken from Quebec, Canada, where unhealthy food advertising bans resulted in lower childhood obesity rates compared to other Canadian provinces.15 Concerning food labelling, all participating countries ranked it with a low level of implementation. Although back of pack nutritional labelling is widely and successfully implemented in the participating European countries, this was due to the lack of front-of pack labelling implementation. Participating countries expressed the need for front-of-pack labelling for consumers to clearly identify unhealthy food items. Best-practice examples of food labelling that could be implemented in European countries include the Nutri-Score26 and warning labels successfully implemented in Chile, and now being followed by other countries.27 Additionally, fiscal policies were identified as important and feasible priorities. Although multiple countries have begun implementing sugar-sweetened beverage taxes,28 country experts also expressed the need to increase tax rates which are often too low, expanding the tax base to include unhealthy ultra-processed foods, to ensure that tax revenues are directed toward public health or human capital investments, and to implement healthy food subsidies (e.g., vegetables) to enable consumers to be able to shift towards healthy dietary patterns.

Beyond the level of policy implementation, it is important to assess the impact of implemented policies. Not all implemented policies have been well evaluated. An example is the effectiveness of the School Fruit Scheme on improving children's and parent's dietary habits. A recent evaluation indicated that the majority of Member States/Regions observed a positive impact of the scheme on children's fruit and vegetables consumption.29

With the Farm to Fork (F2F) strategy being published in 2020,21 the EU has made progress proposing actions that make it easier for member states to adopt healthier and sustainable food environments.23 Some of the actions proposed in the included studies are in line with actions mentioned in the F2F, although a more comprehensive, thorough, and integrated set of actions have been proposed by the Food-EPI experts to improve food environments in Europe, the F2F harmonizes policy actions both addressing climate change and public health.23 Actions also overlap with the assessment of EU-level policies report15 and the Improving dietary intake and achieving food product improvement WHO report,30 where a focus on children is considered an important steppingstone in the prevention of obesity and NCDs, and additionally suggests that EU enforcement and focus on improving food environments is highly recommended. Moreover, some of the expert recommendations, such as the regulation of processed foods, overlap with the WHO ‘Best Buys’ interventions, which include ultra-processed, energy-dense, and nutrient poor product reformulation, such as the elimination of trans fatty acids and food portion size reduction.31 An integrated and unified policy bringing together, under a common umbrella, a range of sectorial policies affecting food production and consumption for Europe is critical for food system transformations.

This requires coherence across policy areas and governance levels. An adaptive pathway approach is also required to facilitate a thorough transition of food systems, which incorporates food democracy, and novel democratic mechanisms into the decision-making.19

Among infrastructure support domains, compliance, and monitoring, health in all policies were a contended issue. Although many forces contribute to unhealthy dietary patterns, obesity, and NCDs, food industry behaviours such as marketing unhealthy foods to children, promoting large portions and between-meal snacks, and exploiting schools for commercial gain, have raised calls for government regulation and require urgent preventive actions which involve policy compliance, monitoring, and the prioritisation of health-in-all-policies to improve population health by coordinating action across health and non-health sectors.32,33

The WHO explicitly encourages member states to monitor nutrition and health status by strengthening and expanding nationally representative health and nutrition surveys. Regular monitoring through health and nutrition surveys ensures successful policy implementation and allows impact assessment and identification of concern areas and inequality, thereby contributing to the improvement of food environments and the prevention of obesity and NCDs.34 The current food environments across the studied European countries require monitoring and further investigation to identify areas for improvement and develop a policy to tackle pressing concerns related to unhealthy diets, obesity, and NCDs.

For example, Slovenia has tested the option to use the Food-EPI study for the mid-term evaluation of the national food and nutrition action plan (FNAP), creating a window of opportunity to repeat the Food-EPI process for the final evaluation in five years.

Taking into account the concerning obesity and NCDs prevalence in the participating European countries, the identified evidence on the level of implementation of food environment policies and expert recommendations, must be considered as important tools to improve and regulate the food environment, and contribute to the reduction of obesity and NCDs.35,36

Strengths and limitations

The Food-EPI tool and process is an established method which provided an ‘upstream’ perspective of the policies and infrastructure support that influence the food environment and dietary choices, for the prevention of obesity and NCDs,37 and was thoughtfully adapted to the European context. The process of consultation with experts allowed an accurate picture of policy action and gaps and helped identify relevant and feasible policy actions for the improvement of food environments. Having carried out the first Food-EPI in the participating European countries, this will allow the reapplication of the Food-EPI tool in the future to measure progress over time.

The creation of an evidence document for each of the participating European countries provides a useful resource for government and non-government sectors wishing to examine policy gaps and coherence. Limitations of the study included minor international dissimilarities in the study procedures (e.g., use of different Likert scale ranges) and the different approaches undertaken to carryout workshops due to COVID-19 containment-and-health policies, enforcing meeting and travel restrictions. Only Ireland and Norway were able to follow the original study protocol. Nevertheless, approaches adopted in the other countries were carefully planned and remained closely aligned with the steps and aims of the study. Similar to other expert panel studies, the different background of experts could have affected their answers. This should be considered when interpreting these results. Inter-rater reliability scores are higher in some countries than others and the types of expert participants differ across countries. Finally, the degree of implementation in the 11 countries was not directly compared by the same experts but assessed independently by separate national expert panels. Some panels may have been more critical than others, limiting the comparability of results.

Next steps

A final and important phase of the Food-EPI process involves the distribution of the recommendations to policy makers or the uptake of recommendations by public health organisations who advocate for policy change and infrastructure support to improve the food environment.37 It is important to ensure accountability and maintain forward momentum despite changes in government leadership and other dynamic contextual factors. Follow-up studies will be key to demonstrating the development and strength of food environment policies occurring in the participating European countries. Monitoring progress in the implementation of food environment policies will contribute to the establishment of healthier food environments that enable healthier diets and reduce the burden of obesity and NCDs. Future research should seek understanding of the underlying reasons for the implementation gaps identified in each country. It is known that political ideology, extensive lobbying of the food industry with conflicting interests, and limited capacity or funding of civil society organizations to apply pressure on political action are obstacles for the implementation of market restrictive policies.16 Yet, we lack clear insight on effective food system transformations overcoming the barriers that impede improvement of nationwide and supranational food environments that, in turn, will enable healthier diets.

Conclusion

The assessment of the level of implementation of food environment policies and infrastructure support by key experts in this study shows there is a vast potential for European countries to improve their policies and infrastructure support influencing food environments. Immediate implementation of policies and infrastructure support that enable healthy food options are required to tackle the burden of obesity and NCDs in European countries.

Contributions

Pooled level analysis

Maartje Poelman, Elisa Pineda, Janas Harrington and Stefanie Vandevijvere led the pooled level analysis across eleven European Countries. MP and EP wrote a first draft of the report and JH and SV contributed to drafting the final report. All co-authors read, provided feedback and approved the final manuscript.

Germany

Peter von Philipsborn led the research. Peter von Philipsborn and Karin Geffert developed the methodology, collected, and analysed the data, interpreted the results, and wrote the first draft.

Ireland

Janas Harrington led the research. Janas Harrington, Charlotte Griffin and Clarissa Leydon with Stefanie Vandevijvere formulated the research questions and designed the study. CG and JH compiled the evidence document. JH drafted the list of experts. CL invited the experts and compiled and analysed the online rating survey. JH facilitated the expert panel workshop. CL complied and analysed the prioritisation survey. CL in collaboration with JH drafted the final report.

The Netherlands

Sanne Djojosoeparto, Carlijn Kamphuis, Maartje Poelman, and Stefanie Vandevijvere formulated the research questions and designed the study. SD collected the evidence regarding the policies and infrastructure support influencing food environments. SD in collaboration with MP and CK drafted the evidence document. SD, in collaboration with MP, and CK drafted a list of experts. SD invited the experts. SD, in collaboration with MP and CK, set up the rating, selection, and prioritisation surveys. SD, in collaboration with CK and MP, conducted the expert workshops. SD analyzed the data from the surveys and the expert workshops. SD, together with MP and CK, had the lead in writing this manuscript. SV critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Norway