Abstract

Background and Hypothesis

Impaired insight into one’s illness is common in first episode psychosis (FEP), is associated with worse symptoms and functioning, and predicts a worse course of illness. Despite its importance, little research has examined the effects of early intervention services (EIS) on insight.

Designs

This paper evaluated the impact of EIS (NAVIGATE) on insight compared to usual community care (CC) in a large cluster randomized controlled trial. Assessments were conducted at baseline and every 6 months for 2 years.

Results

A multilevel regression model including all time points showed a significant time by treatment group interaction (P < .001), reflecting greater improvement in insight for NAVIGATE than CC participants. Impaired insight was related to less severe depression but worse other symptoms and functioning at baseline for the total sample. At 6 months, the same pattern was found within each group except insight was no longer associated with depression among NAVIGATE participants. Impaired insight was more strongly associated with worse interpersonal relationships at 6 months in NAVIGATE than in CC, and changes in insight from baseline to 6 months were more strongly correlated with changes in relationships in NAVIGATE than CC.

Conclusions

The NAVIGATE program improved insight significantly more than CC. Although greater awareness of illness has frequently been found to be associated with higher depression in schizophrenia, these findings suggest EIS programs can improve insight without worsening depression in FEP. The increased association between insight and social relationships in NAVIGATE suggests these 2 outcomes may synergistically interact to improve each other in treatment.

Keywords: recent onset psychosis, social functioning, RAISE-ETP, schizophrenia

Introduction

Impaired insight into one’s illness is a cardinal feature of schizophrenia, present in the vast majority of persons who are symptomatic. Reduced insight is associated with worse psychosocial functioning,1,2 more severe psychotic, negative, and disorganized symptoms,3–6 and a more guarded prognosis.7,8 However, reduced insight in schizophrenia is also associated with less severe depression,9–11 and better subjective mental health functioning.12–14 This divergence in associations between better insight, better psychosocial functioning, and less severe overall symptoms with the exception of worse depression and subjective well-being has been referred to as the “paradox” of insight.15–17

The importance of impaired insight has also been demonstrated in people who have recently experienced the first episode of psychosis (FEP). Specifically, impaired insight in persons with an FEP has been shown to be related to less severe depression but worse other symptoms and psychosocial functioning,18–20 and to predict a worse course of illness.21,22 However, despite the importance of impaired insight in the early course of schizophrenia, little research has examined the effects of early intervention specialty (EIS) programs on insight. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials of EIS programs found that none of the studies reported the effects of an EIS program on insight.23

The present paper was aimed at evaluating the impact of a well-characterized EIS service, the NAVIGATE program,24 on insight compared to usual community care (CC) in the context of a large cluster randomized controlled trial, the Recovery After Initial Schizophrenia Episode-Early Treatment Program (RAISE-ETP).25,26 In addition, because the NAVIGATE program provides a combination of psychoeducation about psychosis and its treatment (both to individuals and family members), destigmatizing and recovery-oriented messages designed to instill hope, positive psychology to enhance resilience, teaching strategies for coping with symptoms, skills training to improve social relationships, and supports for involvement in work or school, all in the context of helping the person work toward personal goals,24 we explored whether associations between impaired insight and symptoms and psychosocial functioning at baseline changed during treatment for participants in NAVIGATE compared to the usual treatment group.

Methods

The RAISE-ETP study was a cluster randomized control trial with 34 participating sites across 21 states within the United States randomized to provide 1 of 2 types of treatment for a 2-year period: usual CC or an early intervention service, the NAVIGATE program.24,26 CC consisted of the usual treatment offered for FEP patients at the individual site.

The NAVIGATE program includes 4 treatment components (individual resiliency training (IRT), family psychoeducation, collaborative medication management, and supported education and employment), which are implemented by a team that meets weekly to coordinate services and review progress.24 IRT, the individual therapy component, is organized into a series of 14 topic areas (or modules). The first seven of these modules are recommended for all FEP participants (and include orientation, goal setting and treatment planning, psychoeducation, relapse prevention planning, processing the initial psychotic episode, developing resiliency, and building a bridge to one’s goals), while the remaining seven modules are selected by the clinician and client depending on the person’s needs (and include dealing with negative feelings, coping with symptoms, developing good relationships, substance use, nutrition and exercise, smoking, and further development of resiliency).27 For further details see Mueser et al. (2015) and the NAVIGATE training website (https://navigateconsultants.org).

Participants

A total of 404 individuals met inclusion/exclusion criteria and participated in the study. Participant characteristics by treatment group are presented in Table 1. Inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) between the ages of 15 and 40 years, (2) experiencing a FEP, (3) less than 6 months prior cumulative use of antipsychotic medication, and (4) diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, brief psychotic episode, or psychosis not otherwise specified. Exclusion criteria were: (1) diagnoses of substance-induced psychosis, psychosis due to general medication condition, or affective psychosis, (2) clinically significant head trauma or other serious medical conditions, or (3) non-English speaking. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and those who are under 18 provided assent with their parent/guardian providing written consent on their behalf. Institutional review board approval was obtained for all sites and all study practices were overseen by the NIMH Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Community Care | NAVIGATE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age | 23.08 | 4.902 | 23.18 | 5.205 |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | 211.43 | 277.486 | 178.91 | 248.731 |

| N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 120 | 66.3 | 173 | 77.6 |

| Female | 61 | 33.7 | 50 | 22.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 18 | 9.9 | 55 | 24.7 |

| Not Hispanic | 163 | 90.1 | 168 | 75.3 |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 6 | 3.3 | 15 | 6.7 |

| Asian | 6 | 3.3 | 6 | 2.7 |

| Black or African American | 89 | 49.2 | 63 | 28.3 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 |

| White | 80 | 44.2 | 138 | 61.9 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 10 | 5.5 | 14 | 6.3 |

| Divorced/separated | 8 | 4.4 | 14 | 6.3 |

| Never married | 163 | 90.1 | 195 | 87.4 |

| Current student | ||||

| No | 134 | 74 | 188 | 84.3 |

| Yes | 47 | 26 | 35 | 15.7 |

| Currently Employed | ||||

| No | 151 | 83.4 | 195 | 87.4 |

| Yes | 30 | 16.6 | 28 | 12.6 |

Measures

Outcome assessments of clinical and psychosocial functioning, and subjective evaluation were conducted via videoconferencing at baseline and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months later by centrally trained interviewers who were blind to participants’ treatment assignment. The Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV disorders (SCID)28 was used to assess primary psychotic diagnosis, lifetime substance use disorder, and duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) at baseline. Due to the wide range in DUP, a median split (74 weeks) was used to dichotomize participants into low vs high DUP.26,29

Clinical Measures

The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) was used to assess depression.30 The CDSS is a 12-item measure using a Likert scale to measure multiple symptoms of depression over the past week, including interviewer observation.

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)31 was used to measure symptoms over the past week, with the Wallwork 5-factor model32 (including positive, negative, depression, excitement, and disorganization factors) employed for statistical analyses. PANSS ratings are made on a seven-point Likert scale with higher ratings representing more severe symptoms. Insight was measured with the Lack of Judgement and Insight item on the PANSS, which evaluates the person’s unawareness of having a psychiatric condition and the need for treatment. The lowest rating on this item, absent (1), corresponds to individuals who recognize they have a psychiatric disorder that requires treatment (recognition of a specific disorder or diagnosis is not required), and which is reflected by realistic short- and long-term planning. Mild impairment, (2) reflects clear recognition of having a psychiatric disorder but underestimation of its seriousness and implications for treatment and poorly conceived planning, while moderate impairment, (3) reflects only shallow awareness of having a disorder and recognition of symptoms, with need for treatment limited to reduction of distress. Severe levels of impairment (ratings 4–7) correspond to individuals who deny the presence of a current psychiatric disorder and need for treatment, with moderately severe, (4) for those who acknowledge a disorder in the past, severe, (5) for those who deny ever having a disorder but who are compliant with treatment, and extremely severe, and (6) for similar individuals but who are not compliant with treatment. This PANSS item is strongly correlated with other measures of insight,33 including the Birchwood Insight Scale (BIS)34 and the Scale of Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD),35 and has been widely used in research on insight in schizophrenia.36–43

Self-Report Subjective Measures

An abbreviated version of the Stigma Scale44 was used to measure perceptions of mental health stigma. Seven items from the Stigma Scale were used in the RAISE-ETP study to assess experiences of discrimination and their interpretation of how others view them in the context of their mental illness. Six of the items were moderately intercorrelated with each other but not the seventh item, which was dropped in a previous analysis.45 The 6-item measure showed moderate internal consistency (α = 0.72). Mental health well-being was assessed using 18 items from the longer version of the Psychological Well-being Scale46 showing fair internal consistency (α = 0.51). This scale captured ratings of different aspects of well-being such as quality of life, focus on goals, happiness with relationships, and feelings of independence.

The Brief Evaluation of Medication Influences and Beliefs Scale47 is a 4-item scale that assesses attitudes toward antipsychotic medication. Ratings are made on a 7-point Likert scale and measures agreement with the following statements: (1) medication prevents a relapse, (2) side effects from antipsychotics bother me (reverse scored), (3) taking antipsychotic medication is difficult to remember (reverse scored), and (4) I feel supported by my social network to take antipsychotic medication. Higher scores reflect more positive attitudes toward taking medication influences.

Psychosocial Functioning

The Quality of Life Scale (QLS)48 was used to assess functional outcomes including social and role functioning. The QLS is a commonly used 21-item, semi-structured interview comprised of four subscales: intrapsychic foundations, interpersonal foundations, instrumental functioning, and common objects and activities as well as a total score.

Statistical Analyses

We first examined the associations between insight and demographic and diagnostic characteristics in the full sample with Pearson’s correlations for continuous variables and t-tests or one-way analyses of variance for categorical variables. To evaluate whether participants who are in NAVIGATE differed from CC in changes in insight over the 2-year study period, we conducted a three-level mixed-effects linear regression model using the same approach as Kane et al. (2016), with changes in the PANSS insight scores from baseline to the four follow-up assessments (6, 12, 18, and 24 months) as the dependent variables, and treatment group, time, and their interactions as the independent variables, including gender, size, and student status as covariates. We included all timepoints in the analysis and linearized the time variable using a square root transformation26 as the largest treatment effects were previously shown to occur in the first 6 months, with effects generally leveling off following this. Multilevel modeling was used in this analysis given the nested structure of the data and models were fit with random intercepts and slopes for the time at the individual and site level. Analyses were conducted using R Studio (Version 1.2.5) and missing data were accounted for using Restricted Maximum Likelihood.

We next evaluated the associations between insight and the other outcome variables (clinical and psychosocial functioning, subjective experience) at baseline by computing Pearson’s correlations in the total sample. Then, to explore whether the NAVIGATE program influenced the associations between insight and the outcome variables differently than CC, we computed Pearson’s correlations at the 6-month assessment separately within each of the treatment groups. To determine whether the strength of correlations between insight and the other outcome variables at 6 months differed significantly between the 2 interventions, we computed Fisher’s r to Z transformations.

We conducted two post hoc analyses to better understand whether the finding from the previous analysis that insight was significantly more strongly correlated with quality of interpersonal relationships (on the QLS) at 6 months for the NAVIGATE group than the CC group. Since the NAVIGATE intervention was more effective than CC at improving both insight and overall symptom severity, as well as interpersonal relationships,26 these analyses explored whether the increased association between interpersonal relationships and insight in the NAVIGATE group was unique to insight or could be explained by similar increases in the association between relationship quality and other dimensions of psychopathology. First, we computed correlations between QLS interpersonal relationships and the PANSS total score (dropping the lack of insight item) along with the PANSS subscales at baseline for the combined sample, and at 6-month separately for each group, and computing Fisher’s r to Z transformations to test differences in the magnitude of correlations between the groups at 6 months. Second, we evaluated whether improvements in interpersonal relationships and reductions in lack of insight and other dimensions of psychopathology over the first 6 months were more strongly associated in the NAVIGATE group than CC by computing correlations between change scores for these variables separately for the two groups and testing the difference in correlations by computing Fisher’s r to Z transformations.

Results

Two demographic variables were significantly associated with impaired insight. Participants who were current students had more intact insight than those who were not (t = 2.05, P = .041), whereas participants who were living at home had less insight than those living elsewhere (t = −2.54, P = .012). DUP was not related to lack of insight at baseline. A one-way ANOVA comparing schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophreniform disorder on insight was not significant. Lifetime alcohol use was not related to insight at baseline, although there was a marginally significant association between lifetime cannabis use disorder (measured on the SCID as none, subclinical, and clinical) and more impaired insight (χ2 = 17.87, P = .057).

Treatment Effects on Insight

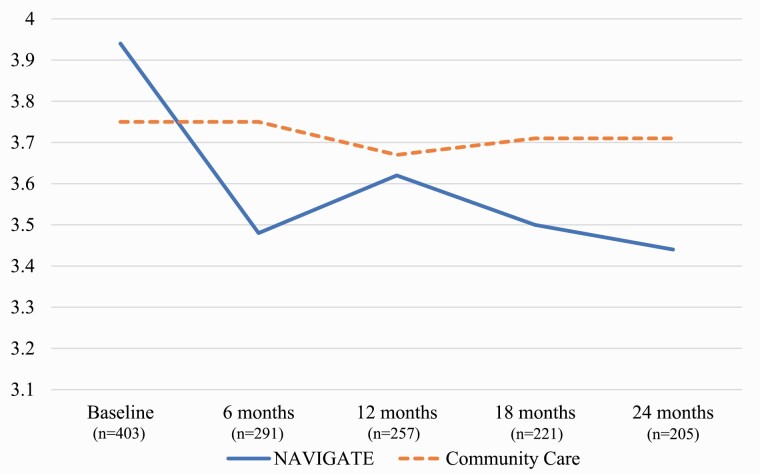

For the multilevel regression model including all timepoints, there was a significant effect of time (P < .001) and a significant interaction between time and treatment group (P < .001) (see table 2 for full details of the model). The results did not change when covariates were excluded from the analysis. The interaction reflected a significantly greater reduction in lack of insight over the study period for the NAVIGATE group than CC, which is depicted in figure 1. Most of the improvement in insight in NAVIGATE occurred during the first 6 months of the study, with more gradual gains over the following 18 months, compared to CC which did not change at all from baseline.

Table 2.

Random and Fixed Effects For Predicting Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Insight

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | St. Error | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.00 | 0.15 | 26.80 | <.001 |

| Gender | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.63 | .53 |

| Student status | −0.24 | 0.11 | −2.15 | .03 |

| Treatment group | −0.12 | 0.13 | −0.93 | .35 |

| Time | −0.09 | 0.02 | −4.70 | <.001 |

| Treatment group: Time | 0.09 | 0.03 | 3.01 | < .001 |

| Random effects | Estimate | SD | ||

| ID: Site (intercept) | 0.45 | 0.67 | ||

| ID: Site (intercept) | 0.83 | 0.17 | ||

| Site (time) | 0.83 | 0.91 |

Fig. 1.

Impaired insight on the PAANSS over time by treatment group.

Symptoms, Functioning, and Subjective Experience Correlates of Insight

Insight at baseline was significantly correlated with all of the outcome measures except stigma. Lack of insight was associated with less severe depression (on both the PANSS and CDSS) and better well-being, but with more severe symptoms on the other PANSS subscales and worse functioning on the total QLS and all its subscales, as well as lower beliefs about the helpfulness of medication. These correlations are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Impairments in Insight at Baseline and Six Month Correlates with Corresponding Demographic, Clinical, and Functional Variables

| Baseline Insight Impairment | 6-Month Insight Impairment |

r to Z | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | NAVIGATE | |||

| r | r | r | Z | |

| PANSS | .342** | .469** | .460** | .090 |

| Negative | .175** | .182** | .305** | -1.027 |

| Positive | .247** | .480** | .411** | .676 |

| Disorganization | .292** | .373** | .358** | .373 |

| Excited | .170** | .383** | .195* | 1.616 |

| Depression | -.132** | -.152 | -.039 | -.895 |

| Quality of Life Scale | -.287** | -.247** | -.388** | 1.233 |

| Intrapsychic Foundations | -.266** | -.251** | -.393** | 1.246 |

| Interpersonal Relationships | -.238** | -.190* | -.412** | 1.927* |

| Common Objects | -.131** | -.100 | -.182* | .700 |

| Role Functioning | -.179** | -.169* | -.171* | .017 |

| Stigma | -.081 | -.072 | .094 | 1.013 |

| Well-being | .133* | .157 | -.085 | 1.910* |

| CDSS | -.144** | -.159 | .034 | 1.524 |

| Medication Beliefs | -.129* | -.141 | -.297** | 1.330 |

Note:

= p < .05;

= p < .01; CC= Community Care; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; CDSS = Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia

Symptoms, Functioning, and Subjective Experience Correlates at 6 Months

The correlations between lack of insight and the other outcomes at 6 months for the CC group were similar to those seen at baseline in the full sample (table 3). For the NAVIGATE group, on the other hand, several correlations were different. Specifically, Fishers r to Z transformations indicated that at 6 months compared to CC, insight was significantly less strongly correlated with well-being in NAVIGATE, but significantly more strongly correlated with interpersonal relationships. Better insight into the illness was more strongly related to worse well-being in the CC group than in the NAVIGATE group at 6 months, whereas better insight was more strongly related to better relationships in NAVIGATE than in CC.

The post hoc analyses examining the correlations between symptom severity on the PANSS and interpersonal functioning on the QLS at 6 months within each of the treatment groups indicated that less severe symptoms (overall and specific subscales) were associated with better social relationships within each of the groups, with no differences between the groups in the strength of any of the correlations (see table 4). Reductions in different dimensions of symptom severity tended to be correlated with improvements in interpersonal relationships in both treatment groups. However, Fisher’s r to Z transformations indicated that two of the correlations in change scores were significantly different between the two groups. First, improvement in insight was significantly correlated with improvement in interpersonal relationships in NAVIGATE but not in CC. Second, improvement in PANSS depression was significantly correlated with improved interpersonal relationships in CC but not NAVIGATE. Relatedly, the difference between treatment groups in the correlation between changes in the CDSS and relationships was marginally significant, with reductions in depression being correlated with improved interpersonal relationships in the CC group but not NAVIGATE.

Table 4.

Correlations between the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) and Interpersonal Relationships on the Quality of Life Scale across both Treatment Groups

| Baseline Interpersonal Relationships | 6-Month Interpersonal Relationships |

r to Z | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | NAVIGATE | |||

| r | r | r | Z | |

| PANSS | -.456** | -.524** | -.610** | 1.061 |

| Negative | -.441** | -.488** | -.613** | 1.505 |

| Positive | -.239** | -.256** | -.301** | .407 |

| Disorganization | -.278** | -.402** | -.375** | -.266 |

| Excited | -.139** | -.115 | -.213** | .842 |

| Depression | -.072 | -.278** | -.151 | -1.114 |

| Lack of insight | -.238** | -.190* | -.412** | 1.927* |

| CDSS | -.167** | -.202* | -.157* | -.388 |

| Change in Interpersonal Relationships from Baseline to 6-Months | r to Z | |||

| CC | NAVIGATE | Z | ||

| Change in PANSS from Baseline to 6-Months | -.372** | -.455** | .837 | |

| Negative | -.352** | -.467** | 1.157 | |

| Positive | -.191* | -.282** | .806 | |

| Disorganization | -.165 | -.230** | .567 | |

| Excited | -.127 | -.089 | -.321 | |

| Depression | -.314** | -.068 | -2.145* | |

| Lack of insight | -.133 | -.355** | 1.982* | |

| CDSS | -.280** | -.097 | -1.59 | |

Note:

= p < .05;

= p < .01; CC= Community Care; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; CDSS = Calgary Depression

Discussion

Participants in the NAVIGATE program, an EIS for persons with FEP, improved significantly more in clinical insight into their illness on the PANSS insight and judgment item than their counterparts (CC) who received usual care. Most of the gains occurred during the first 6 months of the program, with some additional gains over the remaining 18 months. In contrast, participants in CC showed no change in lack of insight from their baseline levels over the 2-year study period, despite improving in all of the symptom subscales of the PANSS over the follow-up period.26

Previous research has shown that people with FEP during an acute episode do improve in insight following pharmacological treatment, but these gains usually occur relatively soon after beginning treatment.20 For example, one study tracked changes in insight in an FEP population over 1 year and found the most pronounced improvement in insight occurred 3 months after initiation of antipsychotic treatment, with few gains thereafter.49 Participants were recruited into the RAISE-ETP study an average of 2 months following their index hospitalization (for the 58.7% of participants who enrolled following a hospitalization), and thus the lack of change in insight in the CC group may be due to the fact that the beneficial effects of antipsychotic medication on insight may have occurred prior to completion of the baseline assessments for the study participants.

Previous randomized controlled studies of EIS programs similar to NAVIGATE have not reported the effects of interventions on the insight.23 One somewhat different program for FEP did report beneficial effects of comprehensive intervention on improved insight. In a randomized controlled trial with 1268 early stage (within the past 5 years) schizophrenia patients, Guo et al. (2010)50 reported that participants who received a program provided one day per month over 12 months which included pharmacological treatment plus psychoeducation, family intervention, social skills training, and cognitive behavior therapy improved more in clinical insight over the year than participants who received pharmacological treatment alone. Improvements in insight both for participants in the NAVIGATE program and those receiving comprehensive treatment in the Guo et al. study may be due to the common elements of psychoeducation provided in both programs. There is growing evidence that psychoeducation about the nature of psychosis and its treatment can have beneficial effects on improving insight into the illness2,17,51 as well as treatment adherence.52 This study’s findings that impaired insight was associated with lower beliefs that medication will be helpful is also in line with prior research on insight, attitudes toward medication, and medication adherence.53,54

Similar to previous research on both FEP and multiepisode schizophrenia populations,9,10,19,20 the present study found that higher levels of clinical insight at baseline were associated with less severe psychotic, negative, disorganized, and excited symptoms, and better psychosocial functioning, but more severe depression and worse well-being. This “paradox” of insight into the illness being related to better functioning and less severe symptoms, but worse subjective experience, has been frequently discussed in the literature.15–17 While similar associations between insight and both depression and well-being were found at the 6-month assessment for participants in CC, among those in NAVIGATE better insight was no longer significantly associated with either worse depression or lower well-being.

There are several reasons why NAVIGATE may have fostered insight into the illness without worsening depression or well-being. First, the overall NAVIGATE program was aimed at supporting self-determination and imbuing hope through the identification of and work toward individual participants’ goals, which often included completing their education, finding or maintaining work, and developing close relationships.24 This focus may have averted the loss of hope associated with understanding the nature of one’s psychiatric illness, which has been found to mediate the effects of insight on depression and well-being.13 Second, psychoeducation was provided in both the family education and IRT components of the NAVIGATE program to provide a positive, recovery-oriented perspective on psychosis, and to avoid negative, “spirit-breaking” messages55 about the illness and its effects on people’s lives. This positive approach may have minimized untoward effects of psychoeducation on improving insight at the cost of worsening mental health well-being, as has been reported in some studies.2,56 Third, the IRT component of NAVIGATE included a specific module on “Processing the Psychotic Episode,” which was aimed at helping individuals develop a personally meaningful narrative about their experience with psychosis to facilitate moving forward with their lives and their goals. As a part of teaching this module, self-stigmatizing thoughts and beliefs that participants had about psychosis were explored, and when present, were actively disputed through the teaching of cognitive restructuring.24,27 Self-stigma about psychosis has been hypothesized to be an important mediator of the effects of insight into the illness and lower mental health well-being.57–59 Fourth, for individuals who had significant symptoms of depression, two additional modules in IRT could be provided, including the “Dealing with Negative Feelings” and “Coping with Symptoms” modules. The skills taught in these modules may have further minimized any effects of increasing insight on worsening dysphoria.

The effects of the NAVIGATE program on improving insight without worsening depression and well-being may be shared by other EIS programs that incorporate similar treatment components. For example, among participants in the EIS program developed by Addington and Addington (2001),60 impaired insight at baseline on the PANSS was significantly correlated with more severe positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and general symptoms, but less severe depression on the CDSS. However, at the 1-, 2-, and 3-year assessments, following improvements in insight, impaired insight was no longer significantly related to depression, while it continued to be related to the severity of other symptoms.61

Aside from the difference between NAVIGATE and CC participants in the associations between insight and depression and well-being at the 6-month assessment, impaired insight was correlated to a similar degree with more severe other symptoms and reduced functioning in most areas between the 2 groups, with one exception: lack of insight was significantly more strongly correlated with the quality of social relationships on the QLS in participants in NAVIGATE (r = −.412) than CC (r =−190). As impaired insight may reflect the overall severity of the illness,62 we explored whether the difference in associations between insight and social relationships between the two groups at 6 months also existed for other symptoms. However, it did not: the severity of other symptoms tended to be correlated with worse social relationships in both groups, with no significant differences between the groups. Examination of the correlations between changes in social relationships and changes in lack of insight and other symptoms over the first 6 months for the two groups provides further evidence for the importance of insight into the illness. Although reductions in most of the symptom dimensions tended to be more strongly correlated with improvements in social relationships in NAVIGATE than in CC, the difference was significant only for the correlation between improved insight and relationships (r = −.355 vs −.133, respectively). Thus, the association between clinical insight and social relationships became significantly stronger over time for the NAVIGATE group than the CC group, and the correlation between changes in insight and relationships was significantly stronger in NAVIGATE than CC, in contrast to all of the other symptom dimensions or overall symptom severity.

The findings indicate that the association between insight into having a psychiatric illness and the quality of social relationships was strengthened in the context of a treatment program (NAVIGATE) that targeted and improved both outcomes. These results raise the possibility that insight and social relationships interacted synergistically over time in response to treatment, with changes in one contributing to changes in the other. For example, improvements in insight may have contributed to better social relationships as individuals’ self-perceptions became more aligned with the perceptions of others, creating a stronger basis for a shared reality within relationships. Gains in the quality of social relationships could have also contributed to improved insight as individuals became closer to and trusted more people, and became more willing to consider their divergent viewpoints, including their perspectives about the individual’s psychiatric illness. In line with this, Koren et al. (2013)63 reported that most of the improvement in insight over the first 6 months of FEP participants in an EIS program occurred due to gains in secondary awareness of the illness, or the ability to appreciate that one’s self-perception is at odds with others. Thus, helping individuals who are recovering from an FEP develop deeper and more meaningful social relationships, including enhancing their capacity to understand others’ perspectives (ie, theory of mind), may foster improved insight into their illness.

One significant limitation of this study was the use of a measure of insight based on a single rating (from the PANSS). For example, the use of a more robust measure of insight, such as the Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD),64 which distinguishes between insight into the illness, symptoms, treatment response, and social consequences, or the BIS,34 which provides a subjective perspective on insight, could have shed more light on the understanding of which dimensions of insight are most strongly correlated with depression (at baseline) and social relationships (at 6 months), which were most sensitive to treatment-related change in the NAVIGATE program. However, we note that the lack of insight item on the PANSS has been shown to be significantly correlated with other measures of clinical insight,33–35 has been used in many other large clinical trials,49,52,65 and was associated with other symptoms and measures of functioning at baseline in this study in a similar way to numerous other studies. Further research is needed to understand the interplay between different dimensions of insight, symptoms, and functioning, and response to EIS treatment in persons recovering from an FEP.

Acknowledgment

We thank all of our core collaborators and consultants for their invaluable contributions, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Executive Committee: John M. Kane, M.D., Delbert G. Robinson, M.D., Nina R. Schooler, Ph.D., Kim T. Mueser, Ph.D., David L. Penn, Ph.D., Robert A. Rosenheck, M.D., Jean Addington, Ph.D., Mary F. Brunette, M.D., Christoph U. Correll, M.D., Sue E. Estroff, Ph.D., Patricia Marcy, B.S.N., James Robinson, M.Ed.

NIMH Collaborators: Robert K. Heinssen, Ph.D., ABPP, Joanne B. Severe, M.S., Susan T. Azrin, Ph.D., Amy B. Goldstein, Ph.D.

Additional contributors to design and implementation of NAVIGATE: Susan Gingerich, M.S.W., Shirley M. Glynn, Ph.D., Jennifer D. Gottlieb, Ph.D., Benji T. Kurian, M.D., M.P.H., David W. Lynde, M.S.W., Piper S. Meyer-Kalos, Ph.D., L.P., Alexander L. Miller, M.D. Ronny Pipes, M.A., LPC-S.

Additional Collaborators: MedAvante for the conduct of the centralized, masked diagnostic interviews and assessments; the team at the Nathan Kline Institute for data management. Thomas Ten Have and Andrew Leon played key roles in the design of the study, particularly for the statistical analysis plan. We mourn the untimely deaths of both. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Haiqun Lin and Kyaw (Joe) Sint to statistical analysis planning and conduct.

We are indebted to the many clinicians, research assistants, and administrators at the participating sites for their enthusiasm and terrific work on the project as well as the participation of the hundreds of patients and families who made the study possible with their time, trust, and commitment.

The participating sites include:

Burrell Behavioral Health (Columbia), Burrell Behavioral Health (Springfield), Catholic Social Services of Washtenaw County, Center for Rural and Community Behavior Health New Mexico, Cherry Street Health Services, Clinton-Eaton-Ingham Community Mental Health Authority, Cobb County Community Services Board, Community Alternatives, Community Mental Health Center of Lancaster County, Community Mental Health Center, Inc., Eyerly Ball Iowa, Grady Health Systems, Henderson Mental Health Center, Howard Center, Human Development Center, Lehigh Valley Hospital, Life Management Center of Northwest Florida, Mental Health Center of Denver, Mental Health Center of Greater Manchester, Nashua Mental Health, North Point Health and Wellness, Park Center, PeaceHealth Oregon/Lane County Behavioral Health Services, Pine Belt Mental HC, River Parish Mental Health Center, Providence Center, San Fernando Mental Health Center, Santa Clarita Mental Health Center, South Shore Mental Health Center, St. Clare’s Hospital, Staten Island University Hospital, Terrebonne Mental Health Center, United Services and University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Pharmacy.

Portions of this research were presented at the 55th Annual Convention of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, New Orleans, LO, November 19, 2021, and Recovery from Serious Mental Illness: A Symposium Honoring the Work of Robert P. Liberman, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, April 27, 2022.

Contributor Information

N R DeTore, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

K Bain, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA.

A Wright, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

P Meyer-Kalos, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Minnesota Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

S Gingerich, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

K T Mueser, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Occupational Therapy, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA.

Funding

This work has been funded in whole or in part with funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and from NIMH under contract HHSN271200900019C.

Disclosures

Drs. Meyer-Kalos and Gingerich are national trainers for the NAVIGATE model. All other authors have no existing conflicts.

References

- 1. Smith TE, Hull JW, Goodman M, et al. The relative influences of symptoms, insight, and neurocognition on social adjustment in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(2):102–108. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199902000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trevisi M, Talamo A, Bandinelli L, et al. Insight and awareness as related to psychopathology and cognition. Psychopathology. 2012;45(4):235–243. doi: 10.1159/000329998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gerretsen P, Takeuchi H, Ozzoude M, Graff-Guerrero A, Uchida H.. Insight into illness and its relationship to illness severity, cognition and estimated antipsychotic dopamine receptor occupancy in schizophrenia: an antipsychotic dose reduction study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sevy S, Nathanson K, Visweswaraiah H, Amador X.. The relationship between insight and symptoms in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xavier RM, Pan W, Dungan JR, Keefe RSE, Vorderstrasse A.. Unraveling interrelationships among psychopathology symptoms, cognitive domains and insight dimensions in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;193:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou Y, Rosenheck R, Mohamed S, et al. Insight in inpatients with schizophrenia: Relationship to symptoms and neuropsychological functioning. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(2-3):376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jacob KS. Insight in psychosis: an independent predictor of outcome or an explanatory model of illness? Asian J Psychiatry. 2014;11:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lincoln TM, Lullmann E, Rief W.. Correlates and long-term consequences of poor insight in patients with schizophrenia. a systematic review. Schizophr Bull. 2006;33(6):1324–1342. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Belvederi Murri M, Respino M, Innamorati M, et al. Is good insight associated with depression among patients with schizophrenia? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2015;162(1-3):234–247. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lysaker PH, Pattison ML, Leonhardt BL, Phelps S, Vohs JL.. Insight in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: relationship with behavior, mood and perceived quality of life, underlying causes and emerging treatments: world psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):12–23. doi: 10.1002/wps.20508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mintz AR, Dobson KS, Romney DM.. Insight in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2003;61(1):75–88. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00316-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooke M, Peters E, Fannon D, et al. Insight, distress and coping styles in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;94(1-3):12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hasson-Ohayon I, Kravetz S, Meir T, Rozencwaig S.. Insight into severe mental illness, hope, and quality of life of persons with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2009;167(3):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Siu CO, Harvey PD, Agid O, et al. Insight and subjective measures of quality of life in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2015;2(3):127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chio FHN, Mak WWS, Chan RCH, Tong ACY.. Unraveling the insight paradox: one-year longitudinal study on the relationships between insight, self-stigma, and life satisfaction among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT.. Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2006;33(1):192–199. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Misdrahi D, Denard S, Swendsen J, Jaussent I, Courtet P.. Depression in schizophrenia: the influence of the different dimensions of insight. Psychiatry Res. 2014;216(1):12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drake RJ, Pickles A, Bentall RP, et al. The evolution of insight, paranoia and depression during early schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2004;34(2):285–292. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mintz AR, Addington J, Addington D.. Insight in early psychosis: a 1-year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2-3):213–217. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Phahladira L, Asmal L, Kilian S, et al. Changes in insight over the first 24 months of treatment in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. 2019;206:394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Drake RJ, Dunn G, Tarrier N, Bentall RP, Haddock G, Lewis SW.. Insight as a predictor of the outcome of first-episode nonaffective psychosis in a prospective cohort study in England. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(01):81–86. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson S, Sathyaseelan M, Charles H, Jeyaseelan V, Jacob KS.. Predictors of insight in first-episode schizophrenia: a 5-year cohort study from India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60(6):566–574. doi: 10.1177/0020764013504561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and Meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):555. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mueser KT, Penn DL, Addington J, et al. The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):680–690. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. The RAISE early treatment program for first-episode psychosis: background, rationale, and study design. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(03):240–246. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-Year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362–372. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15050632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Meyer PS, Gottlieb JD, Penn D, Mueser K, Gingerich S.. Individual resiliency training: an early intervention approach to enhance well-being in people with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatr Ann. 2015;45(11):554–560. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20151103-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID). In: Cautin RL, Lilienfeld SO, eds. The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2015:1–6. doi: 10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Addington J, Heinssen RK, Robinson DG, et al. Duration of untreated psychosis in community treatment settings in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):753–756. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-tyndale E.. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the calgary depression scale. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1993;163(S22):39–44. doi: 10.1192/S0007125000292581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA.. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wallwork RS, Fortgang R, Hashimoto R, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D.. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Quee PJ, van der Meer L, Bruggeman R, et al. Insight in psychosis: relationship with neurocognition, social cognition and clinical symptoms depends on phase of illness. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(1):29–37. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Birchwood M, Smith J, Drury V, Healy J, Macmillan F, Slade M.. A self-report Insight Scale for psychosis: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89(1):62–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tranulis C, Lepage M, Malla A.. Insight in first episode psychosis: who is measuring what? Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008;2(1):34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Keshavan M. Correlates of insight in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(2-3):187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lera G, Herrero N, González J, Aguilar E, Sanjuán J, Leal C.. Insight among psychotic patients with auditory hallucinations. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(7):701–708. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pijnenborg GHM, Spikman JM, Jeronimus BF, Aleman A.. Insight in schizophrenia: associations with empathy. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;263(4):299–307. doi: 10.1007/s00406-012-0373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stratton J, Yanos PT, Lysaker P.. Insight, neurocognition, and schizophrenia: predictive value of the wisconsin card sorting test. Schizophr Res Treatement. 2013;2013:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/696125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cešková E, Přikryl R, Kašpárek T, Kučcerová H.. Insight in first-episode schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2008;12(1):36–40. doi: 10.1080/13651500701422622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grover S, Sahoo S, Nehra R, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A.. Relationship of depression with cognitive insight and socio-occupational outcome in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2017;63(3):181–194. doi: 10.1177/0020764017691314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Santarelli V, Marucci C, Collazzoni A, et al. Could the severity of symptoms of schizophrenia affect ability of self-appraisal of cognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia? Lack of insight as a mediator between the two domains. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;270(6):723–728. doi: 10.1007/s00406-019-01082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lysaker PH, Gagen E, Wright A, et al. Metacognitive Deficits predict impaired insight in schizophrenia across symptom profiles: a latent class analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(1):48–56. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. King M, Dinos S, Shaw J, et al. The Stigma Scale: development of a standardised measure of the stigma of mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190(3):248–254. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mueser KT, DeTore NR, Kredlow MA, Bourgeois ML, Penn DL, Hintz K.. Clinical and demographic correlates of stigma in first-episode psychosis: the impact of duration of untreated psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(2):157–166. doi: 10.1111/acps.13102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(6):1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Warren KA, Golshan S, Perkins DO, Jeste DV.. Brief evaluation of medication influences and beliefs: development and testing of a brief scale for medication adherence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):404–409. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000130554.63254.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT.. The quality of life scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388–398. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pijnenborg GHM, Timmerman ME, Derks EM, Fleischhacker WW, Kahn RS, Aleman A.. Differential effects of antipsychotic drugs on insight in first episode schizophrenia: data from the European First-Episode Schizophrenia Trial (EUFEST). Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(6):808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guo X, Zhai J, Liu Z, et al. Effect of antipsychotic medication alone vs combined with psychosocial intervention on outcomes of early-stage schizophrenia: a randomized, 1-year study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(9):895–904. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pijnenborg GHM, van Donkersgoed RJM, David AS, Aleman A.. Changes in insight during treatment for psychotic disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2013;144(1-3):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim J, Ozzoude M, Nakajima S, et al. Insight and medication adherence in schizophrenia: an analysis of the CATIE trial. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107634. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Beck EM, Cavelti M, Kvrgic S, Kleim B, Vauth R.. Are we addressing the “right stuff” to enhance adherence in schizophrenia? Understanding the role of insight and attitudes towards medication. Schizophr Res. 2011;132(1):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Belvederi Murri M, Amore M.. The multiple dimensions of insight in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(2):277–283. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Deegan PE. Spirit breaking: when the helping professions hurt. J Humanist Psychol. 2000;28(1-–3):194–209. doi: 10.1080/08873267.2000.9976991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cunningham Owens DG, Carroll A, Fattah S, Clyde Z, Coffey I, Johnstone EC.. A randomized, controlled trial of a brief interventional package for schizophrenic out-patients: an interventional package in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103(5):362–369. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chen ESM, Chang WC, Hui CLM, Chan SKW, Lee EHM, Chen EYH.. Self-stigma and affiliate stigma in first-episode psychosis patients and their caregivers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(9):1225–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hasson-Ohayon I, Ehrlich-Ben Or S, Vahab K, Amiaz R, Weiser M, Roe D.. Insight into mental illness and self-stigma: the mediating role of shame proneness. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2–3):802–806. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yanos PT, Lysaker PH, Silverstein SM, et al. A randomized-controlled trial of treatment for self-stigma among persons diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(11):1363–1378. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01702-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Addington J, Addington D.. Early intervention for psychosis: The Calgary early psychosis treatment and prevention program. CPA Bull. 2001:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Saeedi H, Addington J, Addington D.. The association of insight with psychotic symptoms, depression, and cognition in early psychosis: a 3-year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1–3):123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rozalski V, McKeegan GM.. Insight and symptom severity in an inpatient psychiatric sample. Psychiatr Q. 2019;90(2):339–350. doi: 10.1007/s11126-019-09631-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Koren D, Viksman P, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ.. The nature and evolution of insight in schizophrenia: a multi-informant longitudinal study of first-episode versus chronic patients. Schizophr Res. 2013;151(1–3):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Amador XF. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(10):826–836. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950100074007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wiffen B, Rabinowitz J, Fleischhacker W, David A.. Insight: demographic differences and associations with one-year outcome in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2010;4(3):169–175. doi: 10.3371/CSRP.4.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]