Using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Yu et al. described a significant percentage of acanthocytes in peripheral blood from a subgroup of patients (four out of 40) diagnosed with Huntington's Disease (HD) (Yu et al., 2022). Applying whole-exome sequencing as well as clinical reasoning the authors excluded both genetic and other causes for their finding of elevated acanthocyte numbers. The authors conclude that their findings highlight the complexity and diversity of HD.

Increased acanthocytes have been identified as a useful diagnostic finding in conditions with huntingtonism (Feigin and Talbot, 2014) that in the past were grouped under “neuroacanthocytosis syndromes,” an umbrella term to be employed with greatest care (Walker and Danek, 2021). We have concerns that Yu et al.'s report will add to the pre-existing confusion that we have been attempting for several years to dispel regarding diagnosis and classification of these disorders.

Introduced by Karl Singer, acanthocytes, defined by their “thorny” appearance (Greek akantha = thorn), “show several, irregularly spaced, relatively large, coarse, spiculate projections from the surface of the cell, which vary in length and width.” This appearance was felt to be clearly different from the shape of “normal erythrocytes, becoming crenated by exposure to hypertonic salt solutions” (Singer et al., 1952). The term, “echinocyte” (Greek echinos = sea urchin), was introduced to denote “the crenated, spiculated form” of normal erythrocytes “produced by alterations in the intra- or extracellular environment.” The acanthocytes of abetalipoproteinemia (previously denoted as a “neuroacanthocytosis” disorder), in contrast, on SEM were found to “display four to eight large, smooth surface projections from an irregular central mass.” (Bessis and Lessin, 1970). The additional terms “spur cells” (Smith et al., 1964) and “burr cells” (likened “to the prickly envelope of a burr”; Schwartz and Motto, 1949), were declared redundant (Brecher and Bessis, 1972). Normal erythrocytes exposed to appropriate stress to induce echinocyte formation were classified into three stages: echinocytes type I—irregularly contoured disks; II—flat cells with spicules; III—ovoid or spherical cells with 10–30 spicules evenly distributed over the surface (Brecher and Bessis, 1972). Once SEM became the standard for classification (Bessis et al., 1973), Redman et al. further proposed to classify acanthocytosis-prone erythrocytes (as seen in the McLeod phenotype) in five stages based on the shapes they assumed under native and experimental conditions: I—normal discocyte; II—stomatocyte with cuplike invagination; III stomatocyte with many smaller, deep invaginations; AI—acanthocytes I with irregular surfaces; AII—ovoid acanthocytes, with several projections or spicules (Redman et al., 1989).

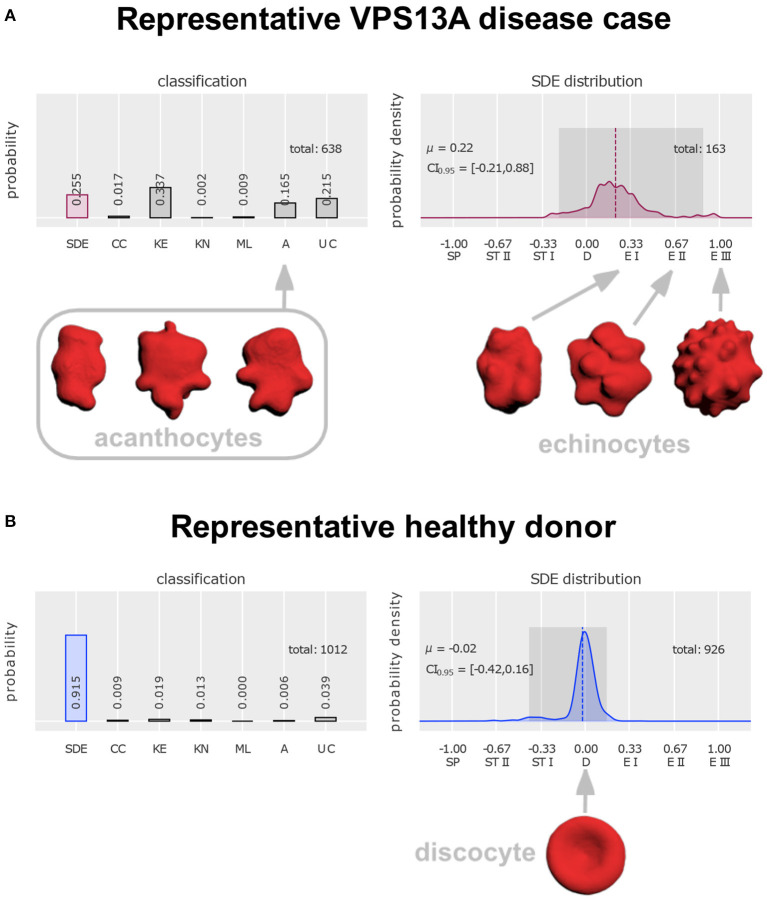

The International Council for Standardization in Hematology currently makes recommendations for visual classification of stained blood films (Palmer et al., 2015), which are, however, less precise in comparison to the above discussions based on SEM. There is a trend to facilitate diagnosis by automation (Kamentsky, 1973) with the goal of obviating these often tricky and time-consuming classificatory decisions by human observers. We recently proposed a protocol for confocal imaging with artificial neural networks that had been trained on six classes of abnormal erythrocytes (acanthocytes included) and a continuous scale of erythrocyte shape transitions (discocyte to echinocyte, or to spherocyte via stomatocyte, respectively; see Figure 1; Simionato et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

Distinction of acanthocytes from echinocytes based on 3D confocal images and classification with artificial neural networks [figure modified from Rabe et al. (2021)]. To arrive at these classifications, a drop of blood was dropped directly (i.e., without anticoagulant exposure) from the blood-drawing needle tip into glutaraldehyde for fixation (Abay et al., 2019), followed by staining with Cell Mask deep red and confocal microscopic imaging (Quint et al., 2017). Artificial intelligence-based classification allows unbiased automated analysis, including a “stomatocyte-discocyte-echinocyte” (SDE) classification on a continuous scale (instead of in discrete classes). For design and validation of the artificial neural network see (Simionato et al., 2021). (A) Classification of erythrocytes from a patient with genetically proven VPS13A disease (chorea-acanthocytosis). The first column on the left reflects the fraction of cells that follow the SDE sequence that erythrocytes show under appropriate environmental conditions. Their distribution is plotted in the right diagram. Its zero value denotes perfect discocytes (D) and positive or negative deviations correspond to echinocytosis (E I–E III) and spherocytosis (SP)/stomatocytosis (ST I–ST II), respectively. Examples of echinocyte types I to III are depicted on the right. The left diagram represents abnormal cell shapes, namely cell clusters (CC), keratocytes (KE), knizocytes (KN), multilobate cells (ML), acanthocytes (A), and unclassifiable cells (UC). Examples of acanthocytes are depicted on the left. (B) Erythrocyte classification of a representative healthy donor and depiction of a perfect discocyte. For patient (A) and control a total of 638 and 1,012 erythrocytes, respectively, were analyzed. In the control a majority of 91.5% conformed with the SDE range (only 25.5% in the patient). There were 16.5% acanthocytes in the patient sample. Apart from detection of a few acanthocytes (0.6%) also in the control, the patient displayed various other irregularly shaped cells (keratocytes, knizocytes, multilobate cells, and unclassifiable cells) in greater abundance (59.3%) than the control (7%). Further, the probability density of the patient's SDE distribution and that of the control differ considerably—due to the presence of echinocytes in the patient that are almost completely absent in the control.

In their SEM study Yu et al. defined acanthocytes as contracted erythrocytes “with a number of irregularly spaced thorny surface projections” and considered them abnormal if their occurrence exceeded 3%. The blood samples had been freshly fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for SEM, the resultant images being analyzed by a board-certified pathologist. Yu et al. concluded that the spectrum of HD may include red blood cell acanthocytosis. The occurrence of acanthocytes outside the limit of normal has so far been thought to be incompatible with a diagnosis of HD and must therefore be interpreted with caution. Three aspects of their work ought to be reflected in particular: (1) difficulties in classification of misshapen erythrocytes; (2) consideration of previous work; (3) role of acanthocyte testing for clinical diagnosis in general.

As already mentioned, the distinction of acanthocytes from other shapes of erythrocytes can be difficult as their definitions may appear insufficient in the individual case. We wonder why Yu et al. relied on the expertise of only one single rater. In contrast, four experienced raters (LK, GS, AS, RHW) in unison identified the majority of non-discocytes in the SEM images of Yu et al. as echinocytes (stages E I or E II, see Figure 1 below). The spicules appeared too small and too regular to classify these cells as acanthocytes. Upon application of our cell shape classification method with artificial neural networks the existence of clear differences between acanthocytes and echinocytes was confirmed (Figure 1; Rabe et al., 2021). The main advantage of this approach is that “prototypes” (e.g., acanthocytes vs. echinocytes) are used for training of the network, which extracts main features and applies criteria for shape classification independent from individual raters.

Earlier studies of erythrocyte morphology in HD failed to detect acanthocytes (Butterfield et al., 1977; Markesbery and Butterfield, 1977; Zanella et al., 1980; Dubbelman et al., 1981; McCormack et al., 1982; Beverstock, 1984; Sassone et al., 2009). Most recently, this was the case in 13 HD patients in whom Storch et al.'s standard technique was applied (Anderson et al., 2017). The systematic prospective reader-blinded analysis of acanthocytosis in movement disorders by Storch et al. is still the de facto standard (albeit without EM confirmation; Storch et al., 2005). Their protocol recommends using isotonically diluted blood samples as unfixed wet preparation and analysis with phase contrast microscopy. The higher sensitivity than that of previous protocols results from the higher susceptibility of acanthocytes to echinocytic stress (here isotonic dilution) in comparison to erythrocytes from healthy donors. According to this protocol, abnormally shaped cells must not exceed a proportion of 6.3% of total erythrocytes (specificity 0.98; sensitivity 1.0). As phase contrast microscopy cannot easily distinguish acanthocytes from echinocytes, all erythrocytes “with spicules, which were irregular in shape and orientation/distribution (corresponding to type AI/AII acanthocytes and echinocytes in Redman's classification using SEM)” were classified as “abnormal.” This implies that this cut-off is robust independently of the exact shape classification. Ever since, Storch's method is highly recommended for acanthocyte testing and would have served as the control method of choice for the samples analyzed by Yu et al. It should also be mentioned that among the five HD patients of Storch et al. none showed significant acanthocytosis.

On a more general level, the current discussion relates to the various obstacles encountered when acanthocyte determinations are performed for clinical diagnosis. The respective approaches are heterogeneous and cut-off values are not universally agreed upon. More appropriate methods such as Storch et al.'s or SEM, along with respective expertise, are not available everywhere. Artifacts (resulting from technique and human factors in shape classification) seem common and can lead to both false positive and false negative results. Furthermore, in a single patient the number of acanthocytes can vary over time, including total absence (Malandrini et al., 1993; Sorrentino et al., 1999; Bayreuther et al., 2010).

The use of acanthocytosis as diagnostic tool in huntingtonism clearly needs great caution and should be supported by the clinical context and other laboratory findings including elevation of creatine kinase and liver enzymes. Decreased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) emerges as a much simpler indirect indicator of acanthocytosis and may be a possible diagnostic biomarker (Darras et al., 2021; Rabe et al., 2021).

To sum up, we strongly doubt that the authors' conclusion is warranted, and suspect that it only serves to contribute to confusion in the literature. It would have required appropriate controls, i.e., use of alternative methods such as the wet blood smear technique (Storch et al., 2005), the use of artificial networks for discrimination of acanthocytes from other abnormally shaped erythrocytes (Simionato et al., 2021), or proxy ESR measurements (Darras et al., 2021). This discussion highlights the phenotypic complexity of the neurodegenerative/neurogenetic disorders characterized by chorea.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

KP was supported by the Rostock Academy of Science (RAS).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Glenn Irvine who sadly passed away, and Ginger Irvine, the founders of the Advocacy for Neuroacanthocytosis Patients (www.naadvocacy.org), and to Susan Wagner and Joy Willard-Williford as representatives of NA Advocacy USA (www.naadvocacyusa.org).

References

- Abay A., Simionato G., Chachanidze R., Bogdanova A., Hertz L., Bianchi P., et al. (2019). Glutaraldehyde - a subtle tool in the investigation of healthy and pathologic red blood cells. Front. Physiol. 10, 514. 10.3389/fphys.2019.00514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D. G., Carmona S., Naidoo K., Coetzer T. L., Carr J., Rudnicki D. D., et al. (2017). Absence of acanthocytosis in Huntington's disease-like 2: a prospective comparison with Huntington's disease. Tremor. Other Hyperkinet. Mov. 7, 512. 10.5334/tohm.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayreuther C., Borg M., Ferrero-Vacher C., Chaussenot A., Lebrun C. (2010). Chorea-acanthocytosis without acanthocytes. Rev. Neurol 166, 100–103. 10.1016/j.neurol.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessis M., Lessin L. S. (1970). The discocyte-echinocyte equilibrium of the normal and pathologic red cell. Blood 36, 399–403. 10.1182/blood.V36.3.399.399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessis M., Weed R. I., Leblond P. F. (1973). Red cell shape – Physiology, Pathology, Ultrastructure. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin. 10.1007/978-3-642-88062-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beverstock G. C. (1984). The current state of research with peripheral tissues in Huntington disease. Hum. Genet. 66, 115–131. 10.1007/BF00286586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecher G., Bessis M. (1972). Present status of spiculed red cells and their relationship to the discocyte-echinocyte transformation: a critical review. Blood 40, 333–344. 10.1182/blood.V40.3.333.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield D. A., Oeswein J. Q., Markesbery W. R. (1977). Electron spin resonance study of membrane protein alterations in erythrocytes in Huntington's disease. Nature 267, 453–455. 10.1038/267453a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darras A., Peikert K., Rabe A., Yaya F., Simionato G., John T., et al. (2021). Acanthocyte sedimentation rate as a diagnostic biomarker for neuroacanthocytosis syndromes: Experimental evidence and physical justification. Cells 10, 40788. 10.3390/cells10040788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbelman T. M., de Bruijne A. W., Van Steveninck J., Bruyn G. W. (1981). Studies on erythrocyte membranes of patients with Huntington's disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 44, 570–573. 10.1136/jnnp.44.7.570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigin A., Talbot K. (2014). Expanding the genetics of huntingtonism. Neurology 82, 286–287. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamentsky L. A. (1973). Cytology automation, in Advances in Biological and Medical Physics, Vol. 14, eds J. H. Lawrence and J. W. Gofman (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ), 93–161. 10.1016/B978-0-12-005214-1.50007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malandrini A., Fabrizi G. M., Palmeri S., Ciacci G., Salvadori C., Berti G., et al. (1993). Choreo-acanthocytosis like phenotype without acanthocytes: clinicopathological case report. A contribution to the knowledge of the functional pathology of the caudate nucleus. Acta Neuropathol. 86, 651–658. 10.1007/BF00294306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markesbery W. R., Butterfield D. A. (1977). Scanning electron microscopy studies of erythrocytes in Huntington's disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 78, 560–564. 10.1016/0006-291X(77)90215-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack M. K., Ullman J., Lazzarini A. (1982). Altered red cell osmotic fragility in Huntington disease (HD). Am. J. Med. Genet. 11, 53–59. 10.1002/ajmg.1320110108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer L., Briggs C., McFadden S., Zini G., Burthem J., Rozenberg G., et al. (2015). ICSH recommendations for the standardization of nomenclature and grading of peripheral blood cell morphological features. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 37, 287–303. 10.1111/ijlh.12327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quint S., Christ A. F., Guckenberger A., Himbert S., Kaestner L., Gekle S., et al. (2017). 3D tomography of cells in micro-channels. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 103701. 10.1063/1.4986392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe A., Kihm A., Darras A., Peikert K., Simionato G., Dasanna A. K., et al. (2021). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and its relation to cell shape and rigidity of red blood cells from chorea-acanthocytosis patients in an aff-label treatment with dasatinib. Biomolecules 11, 50727. 10.3390/biom11050727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman C. M., Huima T., Robbins E., Lee S., Marsh W. L. (1989). Effect of phosphatidylserine on the shape of McLeod red cell acanthocytes. Blood 74, 1826–1835. 10.1182/blood.V74.5.1826.1826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassone J., Colciago C., Cislaghi G., Silani V., Ciammola A. (2009). Huntington's disease: the current state of research with peripheral tissues. Exp. Neurol. 219, 385–397. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. O., Motto S. A. (1949). The diagnostic significance of burr red blood cells. Am. J. Med. Sci. 218, 563–566. 10.1097/00000441-194911000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionato G., Hinkelmann K., Chachanidze R., Bianchi P., Fermo E., van Wijk R., et al. (2021). Red blood cell phenotyping from 3D confocal images using artificial neural networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1008934. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer K., Fisher B., Perlstein M. A. (1952). Acanthrocytosis; a genetic erythrocytic malformation. Blood 7, 577–591. 10.1182/blood.V7.6.577.577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A., Lonergan E. T., Sterling K. (1964). Spur-cell anemia: hemolytic anemia with red cells resembling acanthocytes in alcoholic cirrhosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 271, 396–398. 10.1056/NEJM196408202710804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino G., De Renzo A., Miniello S., Nori O., Bonavita V. (1999). Late appearance of acanthocytes during the course of chorea-acanthocytosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 163, 175–178. 10.1016/S0022-510X(99)00005-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch A., Kornhass M., Schwarz J. (2005). Testing for acanthocytosis A prospective reader-blinded study in movement disorder patients. J. Neurol. 252, 84–90. 10.1007/s00415-005-0616-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. H., Danek A. (2021). “Neuroacanthocytosis” - overdue for a taxonomic update. Tremor. Other Hyperkinet. Mov. 11, 1. 10.5334/tohm.583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Lu Y., Wang F., Xie B., Meng X., Tang Y. (2022). Acanthocytes identified in Huntington's disease. Front. Neurosci. 16, 913401. 10.3389/fnins.2022.913401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanella A., Izzo C., Meola G., Mariani M., Colotti M. T., Silani V., et al. (1980). Metabolic impairment and membrane abnormality in red cells from Huntington's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 47, 93–103. 10.1016/0022-510X(80)90028-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]