Summary

The family is an important contributor to the cultural conditions that support health. Current challenges in family health promotion interventions include programme design that is not always guided by theory and change mechanisms. Multifaceted programmes also make it hard to examine what works for whom, given different family roles and the range of lifestyle behaviour and mechanisms examined within diverse conceptual frameworks and cultures. We performed a scoping review on the heterogeneous literature to map and categorize the models and mechanisms by which a family may promote health behaviours among its members. We searched five electronic databases and grey literature up to 2020. Publications were included if they examined health-promoting behaviours, influences at the family level, and outlined the behavioural mechanisms involved. Two hundred and forty studies were identified. Ecological systems theory, social cognitive theory, family systems theory and the theory of planned behaviour were the frameworks most widely used in explaining either study context and/or mechanism. The most frequently studied family mechanisms involved aspects of family support, supervision and modelling, while some studies also included individual-level mechanisms. Majority of the studies investigated parental influence on the child, while few studies assessed the elderly family member as a recipient or actor of the influences. Studies on African, Asian and Middle Eastern populations were also in the minority, highlighting room for further research. Improving the understanding of context and behavioural mechanisms for family health promotion will aid the development of public health policy and chronic disease prevention programmes, complementing efforts targeted at individuals.

Keywords: family, health behaviour, review, disease prevention, health-promoting environments

INTRODUCTION

The importance of adopting a proactive approach in stemming non-communicable chronic disease (NCD) is necessitated by the global rise in the prevalence of and mortality due to NCDs, such as diabetes and heart disease (World Health Organization, 2014; Naghavi et al., 2017). Without proactive efforts to prevent NCDs, e.g. targeted promotion of healthier lifestyles in the population (Daar et al., 2007), the capacity and sustainability of future healthcare systems may be at risk, especially when combined with ageing populations and shrinking workforces (Beard and Bloom, 2015).

Structural, social and cultural conditions that support health need to be present for effective health promotion (World Health Organization, 2018). The family is well placed to influence such conditions, being one of the significant contributors to an individual’s health status (Mcleroy et al., 1988), with more effect than individual-level factors alone (Ferrer et al., 2005). Changing the values, norms and behaviour patterns in a social unit like the family may create longer-lasting and larger scale behavioural change (Curry et al., 1993; Jennings-Dozier, 1999; Stillman et al., 1999; Secker-Walker et al., 2000). For instance, through modelling of health behaviours, or providing support to improve wellbeing and cope with illness, the family functions as an ecosystem for learning health practices that could last throughout the lifespan (Bomar, 1990). Similarly, the shared household environment, e.g. availability and accessibility of nutritional food or exercise equipment, also influences the health of its members (Davis et al., 2000; Hippisley-Cox et al., 2002). Shared environments that are not conducive to health, together with shared genetic material, may conversely place family members at similar risks for chronic diseases (Seabra et al., 2008). While genetic factors have traditionally been seen as the primary risk source in the family context, spousal concordance for chronic diseases point to the significance of the role of shared environments (Sackett and Holland, 1975; Hippisley-Cox et al., 2002; Agerbo, 2003). Therefore, focussing on both the family and the individual to effect health promotion may prove more synergistic than efforts targeted at the individual alone (Ferrer et al., 2005).

Family health promotion can be defined as ‘the process by which families work to improve or maintain the physical… well-being of the family unit and its members’ (Craft-Rosenberg and Pehler, 2011). The ‘family-level’ processes involve patterns of behaviour within the family with underlying mechanisms (Bomar, 1990; Schwarzer et al., 2011; Tamayo, 2011), e.g. family beliefs and support for healthy lifestyles, demonstrating familial interdependencies and how family members may influence each other in health behaviour (Skelton et al., 2012).

Family health promotion has been examined in various fields (e.g. medicine, sociology, psychology, family therapy, family nursing), giving rise to a heterogeneity of literature that involve terminology, theoretical frameworks, roles of family members involved and health behaviour examined. From the family system’s perspective of how complex familial interactions shape the individual (Bowen, 1966), theoretical adaptations for family health behaviour influence have been wide-ranging and contextualized for segments with different health priorities, including the diverse roles of family members in influencing health behaviours (Rhodes et al., 2020,Rhodes et al. (2020); Michaelson et al., 2021). For example, children have largely been depicted as passive recipients of health influence, with a small number of recent studies recognizing the child as an agent of change within the family (Michaelson et al., 2021). This may point to the association of health behaviour influence with specific roles within the family structure. The types of health behaviours that may be influenced by family members are also varied, e.g. a common theme has been on parental influence on food consumption and physical activity in children, for which systematic reviews have been performed (Brown et al., 2016; Yee et al., 2017). Other themes have been on the influence by family on specific health behaviours, such as alcohol consumption (Hurley et al., 2019), sleep (Bates et al., 2018) and oral hygiene behaviour (De Castilho et al., 2013), using various mechanisms such as parent–child communication, limit setting and modelling. Across these separate streams of research, there is however a lack of comparison and synthesis of theories, mechanisms and roles of health behaviour influence that would aid the understanding of family health promotion and ultimately, the design and development of family health promotion efforts across health behaviours and different cultures.

We thus performed a scoping review with the primary aim to synthesize the broad and heterogeneous literature on the theoretical models and mechanisms of physical health behaviour influence that have been examined in studies (observational or interventional) on family health promotion. Our second aim was to map the roles of family members in relation to the health behaviours of the individual, by examining the potential directions of influence between family members in promoting healthy behaviours. Examples of such directions could include unidirectional influences from parent to child, or reciprocal influences between couples and siblings.

METHODS

Approach

The methodology of this scoping review is based on the framework objectives proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005), and followed the reporting protocol described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Tricco et al., 2018). A scoping review was appropriate, given the breadth and heterogeneity of the literature on the different lifestyle behaviours, family roles and theories applied. In line with other indications for a scoping review (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Munn et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2020), we intended to identify the key factors relating to the concept of family health promotion—the types of theories and behaviour-influencing mechanisms used across different types of health behaviours and cultures, and the pathways of health influence among family members; and to identify gaps in family health promotion research.

Search strategy and information sources

The elements of Population, Concept and Context (PCC mnemonic) were used to guide the search strategy and eligibility criteria (Peters et al., 2020). The Population element was the family living in the same household (Sharma, 2013). The second element of Concept referred to the strategies used to promote health behaviours for the prevention of chronic disease. We were interested in the conceptual explanations and mechanisms of the behavioural influences and the theoretical models/frameworks employed. The Context applied to the search was that the studies must have taken place in natural community settings (i.e. not in institutions).

The electronic databases PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus and PsycInfo were selected as the information sources due to their broad coverage of medico-social literature. Using the search terms identified with the PCC mnemonic, a search syntax was created and customized for each database and can be found in Supplementary File 1. Filters were set to exclude non-human studies and those without abstracts, which generally applies to publications before 1975. 18 June 2020 was the cut-off date for the database searches. In line with a broad review, we did not limit the searches to any publication type, thus non peer reviewed articles (e.g. book chapters) were also considered. There was no language restriction to ensure coverage of studies in all cultural contexts.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (i) examined lifestyle or physical health-related behaviours; (ii) examined health promotion at the family level and (iii) examined models or mechanisms of health promotion.

Articles were excluded if they met any of the exclusion criteria: (i) studies on the management of existing chronic diseases; (ii) studies that only examined the promotion of non-physical health (i.e. mental health, spiritual health); (iii) studies on family members who were not living in the same household; (iv) studies on families living in institutionalized settings (e.g. refugee camp, prison, hospital or long term care facility); (v) studies on communal living arrangements with non-family members (e.g. tenants) and (vi) focussed on infants or toddlers aged 2 years and below. The rationale behind the various exclusion criteria was that the study sought to examine how the average family living in a natural setting may influence or persuade each other to pick up or maintain physical health behaviours, and not as a response to health threats (e.g. diagnosis of a chronic disease within the family), or as part of full caregiving (e.g. with infants). Although non-physical health (e.g. mental health) may affect lifestyle behaviours, studies that only examined the promotion of mental or spiritual health without relating it to physical health were not within the focus of this study and thus excluded.

Selection of articles

Two reviewers (Y.-C.L.H. and C.Z.-H.H.) independently screened the titles and abstracts to determine inclusion status according to the eligibility criteria. Articles which either reviewer judged to have met the inclusion criteria were brought to the full-text screening stage. Two reviewers (D.M. and C.Z.-H.H.) independently screened the full text of articles that passed the title/abstract screen, using the same criteria. Decision conflicts were referred to another independent reviewer (Y.-C.L.H.), who made the final decision blinded to the earlier decisions. Non-English articles were translated into English using Google Translate (https://translate.google.com/).

Data charting process

The data charting form and process were developed collaboratively by the reviewers (C.Z.-H.H., D.M. and Y.-C.L.H.), trialled before implementation and revised to address any data extraction uncertainties. Extraction fields were on publication characteristics (publication period, region/country), study characteristics (study design, participant demographics), targeted lifestyle behaviour, theoretical models/frameworks used, behavioural change mechanisms examined and the direction of health promotion influence studied. The reviewers discussed common themes to categorize the studies. Data from the full-text articles were extracted by two reviewers (D.M. and C.Z.-H.H.). There was regular discussion during the data charting process to clarify definitions and ensure coding consistency.

Synthesis of results

The extracted data were compiled into a single spreadsheet (C.Z.-H.H.) and independently checked (D.M. and Y.-C.L.H.). In line with the descriptive nature of scoping reviews, frequencies and percentages were used to statistically describe the data (Peters et al., 2020). It was not within the purpose of this review to appraise the methodological quality of the articles, as the aim was to map the breadth of the literature and not to evaluate the effectiveness of family health promotion strategies. Critical appraisals for scoping reviews are not generally recommended (Pham et al., 2014; Peters et al., 2020).

RESULTS

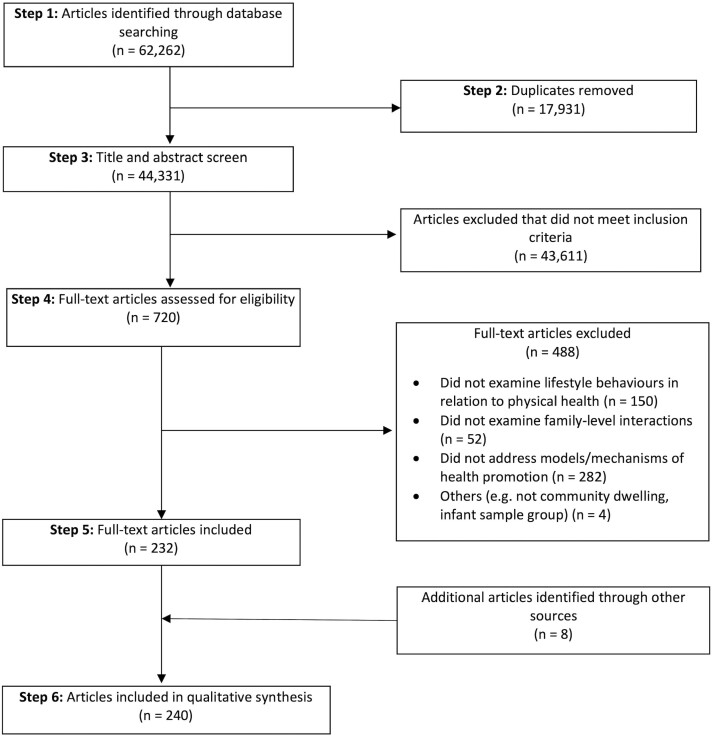

The process from search to analysis took 10 months. An overview of the search, screening and selection process can be found in Figure 1. 62 262 articles were retrieved from the five databases. After de-duplication, 44 331 unique articles were retrieved. 43 611 articles were excluded after the title and abstract screen, and a further 488 articles were excluded after the full-text screen. Two hundred and thirty-two articles were included after the screening procedure (2 were translated from Spanish and Farsi). The list was supplemented by a further 8 articles that were identified through ‘snowballing’ (searching through reference lists), bringing the total to 240 articles for qualitative synthesis. The full list of articles can be found in Supplementary File 2.

Fig. 1:

Flow chart of the selection process.

Period of publication

The included articles were published between 1982 and 2020, with the majority of them published after 2010 (195/240, 81.3%) (Supplementary File 3). Given the search cut-off in June 2020, the publication number for 2020 represented only half that year’s worth. Overall, the results indicate that literature related to health promotion in the family has been given more attention in recent years.

Region and country of publication

Most of the studies were conducted in the Americas (125/252, 29.6%), followed by Europe/Middle East/Africa (63/252, 25.0%) and lastly the Asia-Pacific region (31/252, 12.3%) (Supplementary File 4). Note that studies that were conducted in multiple countries were counted individually for those countries, resulting in a higher total count (n = 252) than the 240 articles included for analysis. When accounting for publications by country, the USA has the most articles (105/252, 41.7%). 13.8% (33/240) of articles did not study a specific country/region (e.g. review papers).

Study design and methodology

The majority were quantitative studies, comprising those with observational (cross-sectional or longitudinal), randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or controlled before–after designs (158/240, 65.8%) (Supplementary File 5). This was followed by qualitative study designs (36/240, 15.0%), including designs such as ethnographic, naturalistic, focus groups or interviews. Other study designs were reviews (20/240, 8.3%), experimental or intervention programme protocols (11/240, 4.6%), theoretical model development (9/240, 3.8%) and mixed design (3/240, 1.3%). Overall, there was a wide variety of study designs observed.

Participant demographics

Of the studies that specified age ranges (140/240, 58.3%), the young segment (children, adolescents) makes up the largest group (96/140, 68.6%). As there was conflict among the articles on the age demarcations of children and adolescents, the children and adolescent groups were combined. Adults (38/140, 27.1%) and the elderly (6/140, 4.3%) constituted the minority of the targeted age segments. The other articles had no specific target age segment (100/240, 41.7%) and either examined a broad range of ages, or the family as a whole. In terms of ethnicity, only 10.4% (25/240) articles focussed on health promotion in families for a specific ethnic group (e.g. African Americans, Latino Americans).

Targeted lifestyle behaviours

There were 319 counts for lifestyle behaviours examined (an article could examine more than one lifestyle behaviour). The types of lifestyle behaviours examined can be found in Supplementary File 6. The most commonly examined behaviours were diet related (137/319, 43.2%), followed by physical activity (117/319, 36.7%). Sedentary behaviours, such watching television and gaming (22/319, 6.9%), miscellaneous health behaviour (e.g. general health maintenance, self-management behaviour) (13/319, 4.1%), smoking (11/319, 3.4%), oral health behaviours such as toothbrushing and flossing (8/319, 2.5%), alcohol consumption (6/319, 1.9%) and sleep (5/319, 1.6%) made up the remainder of targeted behaviours examined.

Theoretical models applied

56.3% (135/240) of the studies used at least one theoretical framework, while the remainder did not explicitly state any model or framework (43.8%, 105/240). (Theories, models and frameworks are used interchangeably.) Of those that used theories in framing their research, we grouped the theories based on how the studies utilized them. ‘Context-only models’ refer to the theories that were used in explaining the context of the study (e.g. usage of the ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1992) to base the individual in the context of socially organized subsystems like the family where there might be mutual influence), while ‘mechanism-only models’ refer to theories used to conceptualize and develop the behaviour-influencing mechanisms [e.g. using the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980) to examine how family members might influence behavioural intent to effect lifestyle changes]. There were also theories used for both context setting and conceptualizing the mechanisms of behaviour influence. Overall, social cognitive theory (SCT) (Bandura, 1986) was the most cited theoretical framework (n = 38), followed by the ecological systems theory (n = 25) and the TPB (n = 22). Forty-two theoretical frameworks were of single use, being cited by only one article within the review. Theoretical frameworks that were family-specific totalled 9, and they included the family systems theory (Bowen, 1966) as the most cited (n = 12), followed by the family ecological model (Davison et al., 2013a) (n = 3). Both these family-based theories were used in setting the context and conceptualizing the mechanisms of behaviour influence. Table 1 shows the categorization of the theoretical frameworks applied in the studies, with studies counted more than once if they used more than one theory.

Table 1:

Theoretical frameworks grouped by purpose of use

| Theoretical framework and purpose of use | n a |

|---|---|

| Context-only usage | 37 |

| Ecological systems theory/framework/model | 25 |

| Developmental health model | 2 |

| Socialisation theory | 2 |

| Bourdieu’s theory of habitus | 1 |

| Coordinated management of meaning | 1 |

| Cultural tailoring | 1 |

| Enduring family socialization model | 1 |

| Family stress model | 1 |

| Health action process approach | 1 |

| Levels of Interacting Family Environmental Subsystems | 1 |

| Lifelong openness model | 1 |

| Model of social control | 1 |

| Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory | 1 |

| Social capital theory | 1 |

| Mechanism-only usage | 67 |

| Theory of planned behaviour | 22 |

| Self-determination theory | 10 |

| Social learning theory | 4 |

| Eccle’s expectancy value theory | 3 |

| Conceptual model of parenting style | 2 |

| Food parenting practice concept map | 2 |

| Health belief model | 2 |

| The youth physical activity promotion model | 2 |

| Adapted information–motivation–behavioural skills model | 1 |

| Behaviour change wheel | 1 |

| Conceptual model of familial approach to the treatment of childhood obesity | 1 |

| Confirmation theory | 1 |

| Daniel’s resiliency theory | 1 |

| Empowerment theory | 1 |

| Exchange theory | 1 |

| Family influence model | 1 |

| Individual and family self-management theory | 1 |

| Information–motivation–behavioural skills model | 1 |

| Integrated model of physical activity parenting | 1 |

| Integrative model of behavioural prediction | 1 |

| Model for intergenerational transfer | 1 |

| Obesity resistance model | 1 |

| Parenting dimension framework | 1 |

| Positive psychology framework | 1 |

| Social development model | 1 |

| Social modelling theory | 1 |

| Social network theory | 1 |

| Theoretical model of parental movement towards action | 1 |

| Theory of family communication patterns | 1 |

| Theory of parent engagement and support, physical activity and academic performance | 1 |

| Transactional model of stress and coping | 1 |

| Transformational leadership theory | 1 |

| Transtheoretical model of change | 1 |

| Usage for both context and mechanism | 60 |

| Social cognitive theory | 38 |

| Family systems theory | 12 |

| Family ecological model | 3 |

| Interdependence theory | 3 |

| Health promotion model | 2 |

| Behavioural choice theory | 1 |

| Developmental niche framework | 1 |

| Dynamic systems theory | 1 |

| Family determinants of health behaviour | 1 |

| Fisher-Owens model of influences on oral health outcomes of children | 1 |

| Matriarchal prevention model | 1 |

| No theoretical framework used | 105 |

Supplementary File 7 provides the list of citations for this table.

a n: counts of usage in studies.

Behaviour-influencing mechanisms investigated

Mechanisms provide explanatory processes or pathways of action for how healthy lifestyles might be promoted among family members. They could be grouped as ‘family-level mechanisms’ or ‘individual-level mechanisms’. Family-level mechanisms describe behaviour-influencing mechanisms in use by the family to effect change in other members, while individual-level mechanisms focus on the internal processes that occur within the individual for the execution of a health behaviour.

A broad range of family-level mechanisms were identified from the literature and grouped together by themes (Table 2). A study could examine more than one mechanism, with each mechanism counted separately. Some listed mechanisms have overlapping meanings, but may not be congruent (e.g. family routine vs. family meal frequency), therefore, we chose to reflect as much as possible the terms used in the studies instead of rephrasing excessively, in order to best represent the meaning of the studies.

Table 2:

Family-level mechanisms by themes

| Mechanisms (family level) | n a |

|---|---|

| Family support | 118 |

| General support for physical activity (social, emotional, participatory, practical) | 31 |

| Parental support for health behaviours (diet, physical activity, oral health) | 22 |

| Autonomy support (being non-judgemental, empathic, responsive to food-related choices, sports and general self-management of health) | 19 |

| Support for healthy eating (fruit and vegetable intake, healthy diet) | 13 |

| Family participation (sports participation, parental engagement) | 13 |

| Social support from partner | 8 |

| Instrumental support (transport, purchase of equipment) | 8 |

| Emotional support (expressing positive emotions, encouragement) | 4 |

| Parental supervision | 86 |

| Parenting style (authoritative, nurturance, structure) | 32 |

| Parental regulation (limit setting, monitoring, supervising, control) | 28 |

| Parenting strategy (rule setting, discipline, reward, encouragement) | 26 |

| Modelling | 78 |

| Parental modelling of healthy eating (fruit and vegetable intake, calcium intake) | 37 |

| Parental modelling of physical activity | 34 |

| General modelling of health behaviours (older sibling or partner as role model, mainly for diet and physical activity) | 7 |

| Feeding | 81 |

| Feeding practices (pressure to eat, restriction, monitoring) | 35 |

| Availability and accessibility of healthy food | 22 |

| Family meal characteristics (frequency, eating at a table, eating with parents, enjoyment) | 19 |

| Meal preparation (healthy meal preparation, family meal preparation) | 5 |

| Health knowledge and awareness | 35 |

| Nutritional knowledge and education | 16 |

| General health knowledge (knowledge to influence healthy habits, health literacy, health education) | 9 |

| Physical activity knowledge and education | 4 |

| Oral health knowledge | 3 |

| Awareness of health risks | 2 |

| Awareness of child behaviour | 1 |

| Family structure and function | 29 |

| Family cohesion | 8 |

| Family roles (spousal role, matriarchal role, parental role for providing meals) | 8 |

| Strength of family relationship (relationship quality) | 6 |

| Family routine | 4 |

| Family resilience and solidarity | 3 |

| Family health culture | 28 |

| Family norms (subjective norms within the family, cultural traditions) | 22 |

| Family health climate (for physical activity and nutrition) | 3 |

| Family sports culture | 2 |

| Family values related to physical activity | 1 |

| Family communication | 27 |

| Parental communication | 12 |

| Supportive communication (responsiveness, positive messages) | 8 |

| Family food discussion | 5 |

| Expressiveness (expressing of feelings, thoughts and opinions) | 2 |

| Health attitudes and beliefs | 21 |

| Health attitudes (family attitudes towards physical activity, parental attitudes towards food) | 12 |

| Health beliefs (behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs) | 9 |

Supplementary File 8 provides the list of citations for this table.

a n: counts of usage in studies.

The most commonly cited mechanisms were within the broad themes of family support (n = 118), family supervision (n = 86) and family modelling (n = 78). Support-related mechanisms ranged from practical support (e.g. transport to sports activities) to social/emotional support in relation to healthy lifestyles (e.g. family encouragement, parental engagement, granting autonomy in food-related choices and sports). Supervision-related mechanisms, mainly related to parental roles, was the next most cited category (parenting style, parental monitoring, parenting strategy), closely followed by modelling-related mechanisms (e.g. a family member being the role model in health behaviours). Given the emphasis on the role of parents among the studies, feeding-related mechanisms were also frequently cited. The other mechanisms cited concerned the themes of knowledge/awareness of health behaviour, family structure and function, family health culture, family communication and health attitudes/beliefs.

Although our focus was on mechanisms used by the family, we also observed that in 20.8% (50/240) of studies, there were individual-level mechanisms identified as complementing family-level mechanisms. In order of citation frequency, they were: self-efficacy (n = 26), health attitudes (n = 16), behavioural intention (n = 15), health beliefs (n = 10), motivation (n = 6), self-esteem (n = 3), health knowledge (n = 2), enjoyment (n = 2) and locus of control (n = 1).

Direction of health promotion influence studied

Table 3 shows the studies that examined specific directions of health influence within the family and Supplementary File 9 gives an overview schematic. The most common direction of influence explored was that of the parent on the child/adolescent (n = 169), followed by the influence of the family unit on an individual family member or vice versa (n = 57). (The ‘family unit’ refers to the collective of family members living in the same household, with no specific member role highlighted.) There were fewer studies between family peers, such as couples (n = 18) and siblings (n = 1). Studies on elderly members of the family were also underrepresented (n = 2), i.e. adult child to elderly parent, and grandparent to grandchild, including a systematic review that found limited studies on the positive effects of grandparents on the grandchild’s health behaviour (Chambers et al., 2017). The direction of influence explored was mainly unidirectional (n = 221). A small number of studies on bidirectional influences (n = 26) were identified, which mostly explored the reciprocal health influence between couples (n = 15).

Table 3:

Directional influences of health promotion efforts within families

| Direction of influence | n a |

|---|---|

| Parent and child/adolescent | 169 |

| Parent > child | 115 |

| Parent > adolescent | 23 |

| Mother > child | 12 |

| Father > child | 6 |

| Parent <> child | 6 |

| Father > daughter | 2 |

| Child > parent | 1 |

| Father <> child | 1 |

| Mother > daughter | 1 |

| Parent <> adolescent | 1 |

| Mother <> adolescent | 1 |

| Family unit and individual | 57 |

| Family > child | 23 |

| Family > individual | 16 |

| Family > adolescent | 10 |

| Family > mother | 2 |

| Family > young adult | 1 |

| Family > elderly | 1 |

| Mother > family | 1 |

| Child > family | 1 |

| Adolescent > family | 1 |

| Family <> adolescent | 1 |

| Couples | 18 |

| Couples <> (including four studies on elderly couples) | 15 |

| Husband > wife | 2 |

| Wife > husband | 1 |

| Others | 3 |

| Sibling > sibling | 1 |

| Adult > elderly parent | 1 |

| Grandparent > grandchild | 1 |

‘>’ refers to the direction of influence and ‘<>’ refers to a reciprocal influence. Supplementary File 10 provides the list of citations for this table.

a n: counts of usage in studies.

Summarized results of RCTs

Although it was not within the purpose of this scoping review to appraise the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions, we nonetheless present a summary of the 23 RCTs in the review (details in Supplementary File 11). Majority of the directional influences examined concerned the influence of the parents/family on the child/adolescent (78.3%, 18/23). Of the lifestyle behaviours targeted in the interventions, dietary behaviours comprised almost half (15/33, 45.5%). Supplementing dietary interventions, five RCTs featured an additional physical activity component to facilitate weight loss outcomes. The other RCTs looked at improving physical activity alone, reducing smoking or reducing alcohol consumption. Two RCTs did not observe any intervention effects (programmes involving parental modelling, feeding, family meals) on health outcomes (body mass index [BMI], weight status) when compared with the control groups. The remaining 21 RCTs were able to provide support for the role of the family in lifestyle intervention leading to improved health outcomes.

DISCUSSION

In this scoping review, we summarized the literature on health promotion within the family, specifically on the use of theoretical models relating the family to health behaviour among individuals, and how individuals’ health behaviour might be influenced through a variety of behavioural mechanisms. We also mapped the roles that family members may play through assessing directions of health behaviour influence between family members that have been examined in the literature, identifying areas for further study.

Theoretical models for family health promotion

Several theoretical frameworks dominated the family health promotion literature. These included SCT (Bandura, 1986), ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1992) and the TPB (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). The theories have been applied to either set the context for investigating the role of the family in health behaviours of the individual (i.e. context theory), and/or to place the investigated mechanisms of how the family might influence individual family members within a school of thought (i.e. mechanisms theory). We also observed several studies that sought to develop new family-specific models that extend from existing theories.

Ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1992) was the most commonly used contextual theory, explaining how the environmental subsystems within which an individual is situated might influence the development of health behaviours (Ndiaye et al., 2013; Bringolf-Isler et al., 2018). The theory acknowledges the interrelation between different settings or systems (e.g. at the macro, meso and micro levels) and how that would shape the development of healthy behaviours. This multilayered framework covers a broad range of factors, and has precipitated the development of other family-specific models like the family ecological model (Davison et al., 2013a) and the Levels of Interacting Family Environmental Subsystems (LIFES) framework (Niermann et al., 2018).

SCT and the TPB, on the other hand, were the most often used theories to explain the mechanisms for family health promotion. These theories take into account the individual’s internalization of environmental factors (e.g. family norms or practices) to achieve a health behaviour change (Bassett-Gunter et al., 2015; Zacarías et al., 2019). Studies that adopted the TPB examined how the family, or more specifically parents, could influence the child to improve their diet or physical activity levels (15 out of 22 studies). The use of SCT has been more wide-ranging, being applied to explain behaviour change in different members of the household and for different study designs (e.g. reviews, RCT and observational studies). Almost half of the studies that applied SCT (18 out of 38) were interventional studies. Although the majority applied the theory to explain mechanisms, there were a few studies that also used SCT to set the context for their investigations, e.g. studies on family meals used measurements guided by SCT and highlighted the role of family meals in shaping healthy dietary practices (Burgess-Champoux et al., 2009; Fulkerson et al., 2015).

While the majority of the studies used general behaviour theories, there was moderate application of family-specific theories, with the most cited being the family systems theory (12 studies) and the family ecological model (3 studies). Family-specific theories look at the interdependencies within the family system and theorize how the family, as a goal-oriented unit, aims towards stability even as it is influenced by interactions internally and externally (Skelton et al., 2012). For example, family systems theory (Bowen, 1966), a foundation for understanding and intervening upon family behaviour, suggests that the family is constantly interacting and evolving through challenges and reorganization, thus any intervention should target the family rather than the individual (Cox and Paley, 1997; Rhodes et al., 2020). Drawing from this perspective and the ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1992), the family ecological model (Davison et al., 2013a) posits that the contexts in which families are embedded will shape parental influence on children’s health behaviours. For example, parenting cognitions, beliefs and behaviours could be affected by family ecological factors, e.g. educational, cultural backgrounds and community factors like social capital. The model suggests that addressing antecedent factors could aid in the understanding of health promotion within the family and the development of effective interventions.

Slightly less than half of the studies included a theoretical framework, suggesting potential barriers to integrating suitable theories. Likewise, a review on the paediatric obesity literature showed limited usage of theories to guide interventions (Skelton et al., 2012). Selecting theories that are consistent with the unit of practice and tested in similar settings and populations may act as a guide to enhance the utility of suitable theories in developing or evaluating health-promoting programmes (van Ryn and Heaney, 1992). In health promotion, the application of family-specific behavioural theories could enhance the understanding of the underlying determinants in the process of health behaviour change for the individual, and guide practitioners to target the appropriate environmental, psychosocial and behavioural attributes to promote health within the family (van Ryn and Heaney, 1992; Kitzman-Ulrich et al., 2010; Pratt and Skelton, 2018).

Mechanisms of family health promotion

Looking beyond mere associations of family behaviour and health outcomes, a key objective of this review was to identify the behavioural mechanisms by which a family could influence the adoption of healthy lifestyles among its members. The behavioural mechanisms were not mutually exclusive and multiple mechanisms were often identified and investigated in the studies. Among family-level mechanisms, family support, supervision and modelling were the most frequently cited. Support-related mechanisms included social/emotional support, co-participation in physical activity and logistical support in the form of transportation or purchasing of healthy foods or sports equipment. Modelling as a mechanism was employed largely for healthy eating and physical activity, two observable activities in the family. Articles that addressed family support and modelling often described the interaction between at least one parent and a child. The supervision mechanisms identified were solely in terms of parental roles, though one could also envision other senior family members (e.g. grandparents or older siblings) employing similar mechanisms, which could be examined or employed in future studies. Nonetheless with almost 70% of the included studies examining parents’ influence on children’s health behaviour, there were unsurprisingly a number of mechanisms specific to parent–child influence, especially if the studies were informed by parent-specific theories. An example is the parenting dimensions framework, which explains how children’s perception of parental responsiveness and demandingness influences their motivational regulation for physical activity (Maccoby and Martin, 1983; Laukkanen et al., 2020). This framework also forms the basis for other parenting models like Darling and Steinberg’s contextual model of parenting style and the integrated model of physical activity parenting, which were used in several studies (Darling and Steinberg, 1993; Hennessy et al., 2010; Davison et al., 2013b; Sohun et al., 2021).

We also identified from the literature individual-level mechanisms that were addressed together with family-level mechanisms. Individual-level mechanisms involve internal or transactional processes that either trigger a health behaviour change, or enable the individual to achieve a health-related goal, e.g. through self-empowerment or self-regulation (Karoly, 1993). Self-efficacy (n = 23) was the most frequently cited individual-level mechanism and was a common construct highlighted in studies that applied SCT or TPB frameworks.

Agents of change within the family

A multitude of roles and pathways exist within the family for influencing the health of individual members, among which parental roles are crucial for baseline health and the nurturing of healthy lifestyles in children (Shields et al., 2019). The importance of parental roles is shown in the high proportion of studies examining this (~70%). Fourteen studies involved mothers as the primary caregiver to influence child health behaviour, especially given the prominent role of the family matriarch in shaping the health behaviours of family members, through mechanisms such as modelling, support and education (Wild et al., 1994). Nevertheless, the need to involve the father in family health promotion efforts has also been pointed out (Hennessy et al., 2010; O’Dwyer et al., 2012; Dailey et al., 2014), and this review identified nine studies that focussed on paternal influences of health behaviour. The different roles undertaken by mothers and fathers also influence the type of interaction between each dyad (e.g. mother–child; father–child), which may elicit different responses from the child. For example, teenage daughters may be more responsive to encouragement from mothers on weight management (Dailey et al., 2014) and children may be more likely to imitate their fathers’ eating and exercise habits (Lloyd et al., 2014; Watterworth et al., 2017). Nonetheless, there needs to be behavioural congruence between parents to ensure a more favourable response from the child (Gevers et al., 2015). For example, improved levels of children’s physical activity were associated with matched contributions of support from both mothers and fathers (Solomon-Moore et al., 2018). Although this could have been due to greater support overall, it suggests the importance of examining the roles of positive co-parenting relationships, which could in turn enhance the relationship between parent and child for more effective health behaviour influence (McHale and Rasmussen, 1998; Solomon-Moore et al., 2018).

While the traditional role of the adult caregiver to influence change in the child has been widely discussed in the literature and adopted in public health interventions (Wyszynski et al., 2011; Bringolf-Isler et al., 2018), the reverse role of the child as an agent of change within the family could be better explored. From this novel perspective, two related studies have described how children in American Indian households have acted as change agents by sharing nutrition and physical activity knowledge, and have encouraged family caregivers to adopt healthy behaviours (Gadhoke, 2012; Gadhoke et al., 2015). Given that these two studies were specific to a minority culture, further research is needed to explore how the identified influencing mechanisms of the child’s resilience, knowledge and self-efficacy, could be generalized to other cultural contexts, particularly cultures with hierarchical traditions, where senior family members may be less receptive to influence from younger members. Our review also identified one study investigating how socio-emotional support from adult children could improve the physical activity levels of their elderly parents (Thomas et al., 2019). As populations age, it is all the more important to harness the strengths of the family in promoting and maintaining the health of the elderly. Thus, the role of adult children to influence healthy behaviours in elderly parents requires further attention.

Given the dynamic and reciprocal nature of family systems (Bowen, 1966), influences of family members may be more than unidirectional. Our review points to a lack of studies exploring the bidirectional nature of health behaviour influence, with only 26 studies examining this relationship. Following the thread of children being change agents, parents may be encouraged to engage in good dietary practices and exercise behaviours when they see their children making healthy lifestyle changes (Dailey et al., 2014). In response, parents may be more likely to maintain such behaviours as a form of encouragement to their children to sustain the healthy habits, thus forming a feedback loop of health influence (Dailey et al., 2014). Exploring the reciprocal relationship in influencing health behaviours may help us better understand family health promotion and its potential multiplier effects, due to the interactions within the family system.

Health promotion among older family members

Our findings have demonstrated that there is a paucity of research specific to health promotion among family members who are elderly (7 out of 240 studies). The studies have explored mutual couple influences (n = 4), grandparents encouraging healthy behaviours in grandchildren (n = 1) or the elderly receiving support from younger family members or the family as a whole (n = 2).

A lack of research on family health promotion roles for the elderly (as change agents and/or as recipients) could be due to several reasons. First, the main type of family structure in modern Western societies, where most research has been done, has been the nuclear family (Bengtson, 2001) and elderly parents are generally not part of the household (Reher and Requena, 2018), contrasting with societies such as those in Asia or Africa, where three generational households are more common (Chambers et al., 2017). Second, in terms of health-promoting behaviours, the focus for the elderly population is often related to their physical functioning, independence in their daily living or self-care activities (Dean and Holstein, 1991). This set of health behaviour is specific to the elderly population and distinct from those of younger groups of people. Motivation to exercise for the elderly may also be influenced strongly by non-familial factors, such as support from friends, the community and the endorsement from a physician (Cousins, 1995; Hu et al., 2021). The perception of social support to partake in physical activity may diminish with age, as the elderly may hold different worldviews about adopting health-promoting behaviour (e.g. assuming that others have given up on them, or adopting a more reactive approach to cope with illness) (Cousins, 1995). Thus, we will need to develop age- and culture-specific strategies for the family to promote health behaviours among older members.

Limitations

As our intention was to assess the extent of research done across health domains, family roles, cultures and including non-empirical studies (e.g. theory development), we did not exclude studies based on methodological quality, common to the purpose and protocol of scoping reviews (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Peters et al., 2020). Therefore, it has to be noted that the quality of the articles included in the review may vary. The diversity of the literature also made it challenging to capture detailed nuances from the evidence extracted, in particular qualitative studies. While evaluating the effectiveness of family health promotion strategies was beyond the scope of this review, we nonetheless observed that the majority of the RCTs (21 out of 23) were able to demonstrate significant intervention effects on various health behaviours (e.g. diet, physical activity) leading to improved health outcomes (e.g. BMI).

Areas for further research and conclusion

The findings from this review point to several areas that could benefit from further research. To design interventions for behaviour change, an understanding of behavioural mechanisms is necessary. Yet we found that many studies did not mention mechanisms explaining the influence of the family on health behaviours (282 of 488 articles excluded at full-text screen). Examples include studies that examined the correlations of parental attributes with children’s health behaviour, but without explanation on how the parental attribute might have influenced the children’s health behaviour. Hence, future studies would benefit from the use of theoretical frameworks and clear description of mechanisms of behavioural change to further explicate effective intervention components that works for specific population groups (Koepsell et al., 1992; Hamilton et al., 2020).

Currently under-represented, more research could be conducted in regions such as Asia, Africa and the Middle East to understand the family roles and mechanisms that work best in these populations. For instance, in Asian culture, adults even when married, are more likely to live with their parents, due to the greater emphasis on family obligation, parental approval and general family allocentrism (Lou et al., 2012). Such Asian communities, e.g. in China may facilitate transmission of behaviours, and the health behaviour propagation appears to be more pronounced among the elderly and in rural areas in China (Hu et al., 2021).

More consideration on behaviour change mechanisms that are effective for adults and the elderly is needed, especially in ageing populations and changing family structures that include more elderly members. For example, there are trends in the West of multigenerational households (Burgess and Muir, 2020; Pilkauskas et al., 2020) and more adult children living with elderly parents (Manacorda et al., 2006; Fry, 2016; Glassman et al., 2019). Since our review points to an under-representation of adult family members as the target of health behaviour influence, there could be further study on how their health behaviours could be supported, e.g. if they hold multiple roles, as a parent or caregiver to their elderly parent, the competing demands could lead to poorer adoption of health behaviours due to shifting the prioritization of health to other family members (Chassin et al., 2010). Although it may appear more promising to focus health promotion efforts on family members during their youth, it does not diminish the need to reciprocally enhance the health potential of adults and the elderly. Therefore, a life-course approach in health promotion should be considered.

To conclude, we have performed a scoping review of models, mechanisms and directions of influence to clarify the heterogeneous literature concerning the role of the family in health promotion. An important next step would be to systematically evaluate what works for what kind of families. This will serve to develop ‘family-sensitive’ health promotion strategies (Sindall, 1997) relevant to context and culture and complement efforts on individuals.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Yi-Ching Lynn Ho, Centre for Population Health Research and Implementation (CPHRI), Singapore Health Services, Singapore; Programme in Health Services & Systems Research, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore.

Dhiya Mahirah, Centre for Population Health Research and Implementation (CPHRI), Singapore Health Services, Singapore.

Clement Zhong-Hao Ho, Centre for Population Health Research and Implementation (CPHRI), Singapore Health Services, Singapore.

Julian Thumboo, Centre for Population Health Research and Implementation (CPHRI), Singapore Health Services, Singapore; Department of Rheumatology & Immunology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; Medicine Academic Clinical Programme, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore.

Funding

This work was supported by National Medical Research Council, Singapore (Grant Ref: NMRC/CG/C027/2017).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Agerbo, E. (2003) Risk of suicide and spouse’s psychiatric illness or suicide: nested case-control study. BMJ, 327, 1025–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980) Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. and O’Malley, L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett-Gunter, R., Levy-Milne, R., Naylor, P., Downs, D., Benoit, C., Warburton, D.et al. (2015) A comparison of theory of planned behavior beliefs and healthy eating between couples without children and first-time parents. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 47, 216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, C. R., Buscemi, J., Nicholson, L. M., Cory, M., Jagpal, A. and Bohnert, A. M. (2018) Links between the organization of the family home environment and child obesity: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 19, 716–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard, J. R. and Bloom, D. E. (2015) Towards a comprehensive public health response to population ageing. Lancet (London, England), 385, 658–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, V. L. (2001) Beyond the nuclear family: the increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bomar, P. J. (1990) Perspectives on family health promotion. Family and Community Health, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, M. (1966) The use of family theory in clinical practice. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 7, 345–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringolf-Isler, B., Schindler, C., Kayser, B., Suggs, L. S. and Probst-Hensch, N. (2018) Objectively measured physical activity in population-representative parent-child pairs: parental modelling matters and is context-specific. BMC Public Health, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992) Ecological systems theory. In Vasta, R. (ed), Six Theories of Child Development: Revised Formulations and Current Issues. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, pp. 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H. E., Atkin, A. J., Panter, J., Wong, G., Chinapaw, M. J. M. and van Sluijs, E. M. F. (2016) Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: a systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obesity Reviews, 17, 345–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, G. and Muir, K. (2020) The increase in multigenerational households in the UK: the motivations for and experiences of multigenerational living. Housing, Theory and Society, 37, 322–338. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess-Champoux, T. L., Larson, N., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Hannan, P. J. and Story, M. (2009) Are family meal patterns associated with overall diet quality during the transition from early to middle adolescence? Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 41, 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S. A., Rowa-Dewar, N., Radley, A. and Dobbie, F. (2017) A systematic review of grandparents’ influence on grandchildren’s cancer risk factors. PLoS One, 12, 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin, L., Macy, J. T., Seo, D. C., Presson, C. C. and Sherman, S. J. (2010) The association between membership in the sandwich generation and health behaviors: a longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, S. O. (1995) Social support for exercise among elderly women in Canada. Health Promotion International, 10, 273–282. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M. J. and Paley, B. (1997) Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft-Rosenberg, M. and Pehler, S. (eds) (2011) Role of families in health promotion. In Encyclopedia of Family Health, Vol. 1. SAGE Publications, Inc., Los Angeles, pp. 912–913. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, S. J., Wagner, E. H., Cheadle, A., Diehr, P., Koepsell, T., Psaty, B.et al. (1993) Assessment of community-level influences on individuals’ attitudes about cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and consumption of dietary fat. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 9, 78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daar, A. S., Singer, P. A., Leah Persad, D., Pramming, S. K., Matthews, D. R., Beaglehole, R.et al. (2007) Grand challenges in chronic non-communicable diseases. Nature, 450, 494–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey, R. M., Thompson, C. M. and Romo, L. K. (2014) Mother-teen communication about weight management. Health Communication, 29, 384–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling, N. and Steinberg, L. (1993) Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. A., Murphy, S. P., Neuhaus, J. M., Gee, L. and Quiroga, S. S. (2000) Living arrangements affect dietary quality for U.S. adults aged 50 years and older: NHANES III 1988–1994. The Journal of Nutrition, 130, 2256–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison, K. K., Jurkowski, J. M. and Lawson, H. A. (2013a) Reframing family-centred obesity prevention using the Family Ecological Model. Public Health Nutrition, 16, 1861–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison, K. K., Mâsse, L. C., Timperio, A., Frenn, M. D., Saunders, J., Mendoza, J. A.et al. (2013b) Physical activity parenting measurement and research: challenges, explanations, and solutions. Childhood Obesity (Print), 9 Suppl(Suppl. 1), S103–S109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Castilho, A. R. F., Mialhe, F. L., De Souza Barbosa, T. and Puppin-Rontani, R. M. (2013) Influence of family environment on children’s oral health: a systematic review. Jornal de Pediatria, 89, 116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean, K. and Holstein, B. E. (1991) Health promotion among elderly. In Badura, B. and Kickbusch, I. (eds), Health Promotion Research. Towards a New Social Epidemiology. WHO Regional Publications, European Series 37, London, pp. 341–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, R. L., Palmer, R. and Burge, S. (2005) The family contribution to health status: a population-level estimate. Annals of Family Medicine, 3, 102–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry, R. (2016) For first time in modern era, living with parents edges out other living arrangements for 18- to 34-year-olds share living with spouse or partner continues to fall. Pew Research Center. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED575479 (last accessed 8 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson, J. A., Friend, S., Flattum, C., Horning, M., Draxten, M., Neumark-Sztainer, D.et al. (2015) Promoting healthful family meals to prevent obesity: HOME Plus, a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadhoke, P. (2012) Structure, Culture, and Agency: Framing a Child as Change Agent Approach for Adult Obesity Prevention in American Indian Households. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Gadhoke, P., Christiansen, K., Swartz, J. and Gittelsohn, J. (2015) Cause it’s family talking to you: children acting as change agents for adult food and physical activity behaviors in American Indian households in the upper midwestern United States. Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark), 22, 346–361. [Google Scholar]

- Gevers, D. W., van Assema, P., Sleddens, E. F., de Vries, N. K. and Kremers, S. P. (2015) Associations between general parenting, restrictive snacking rules, and adolescent’s snack intake. The roles of fathers and mothers and interparental congruence. Appetite, 87, 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman, A., Mcgregor, S. E., Aboderin, I., Bachrach, C. A., Basu, A., Davis, S.et al. (2019) Population bulletin America’s changing population what to expect in the 2020 census, vol. 74. www.prb.org (last accessed 6 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, K., van Dongen, A. and Hagger, M. S. (2020) An extended theory of planned behavior for parent-for-child health behaviors: a meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 39, 863–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy, E., Hughes, S. O., Goldberg, J. P., Hyatt, R. R. and Economos, C. D. (2010) Parent-child interactions and objectively measured child physical activity: a cross-sectional study. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippisley-Cox, J., Coupland, C., Pringle, M., Crown, N. and Hammersley, V. (2002) Married couples’s risk of same disease: cross sectional study. BMJ, 325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F., Shi, X., Wang, H., Nan, N., Wang, K., Wei, S.et al. (2021) Is health contagious? Based on empirical evidence from China family panel studies’ data. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 691746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, E., Dietrich, T. and Rundle-Thiele, S. (2019) A systematic review of parent based programs to prevent or reduce alcohol consumption in adolescents. BMC Public Health, 19, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings-Dozier, K. (1999) Predicting intentions to obtain a Pap smear among African American and Latina women: testing the theory of planned behavior. Nursing Research, 48, 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karoly, P. (1993) Mechanisms of self-regulation: a systems view. Annual Review of Psychology, 44, 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzman-Ulrich, H., Wilson, D. K., George, S. M. S., Lawman, H., Segal, M. and Fairchild, A. (2010) The integration of a family systems approach for understanding youth obesity, physical activity, and dietary programs. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 231–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell, T. D., Wagner, E. H., Cheadle, A. C., Patrick, D. L., Martin, D. C., Diehr, P. H.et al. (1992) Selected methodological issues in evaluating community-based health promotion and disease prevention programs. Annual Review of Public Health, 13, 31–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen, A., Sääkslahti, A. and Aunola, K. (2020) It is like compulsory to go, but it is still pretty nice: young children’s views on physical activity parenting and the associated motivational regulation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, A. B., Lubans, D. R., Plotnikoff, R. C. and Morgan, P. J. (2014) Impact of the ‘Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids’ lifestyle programme on the activity-and diet-related parenting practices of fathers and mothers. Pediatric Obesity, 9, e149–e155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou, E., Lalonde, R. N. and Giguère, B. (2012) Making the decision to move out: bicultural young adults and the negotiation of cultural demands and family relationships. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43, 663–670. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby, E. E. and Martin, J. A. (1983) Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction. In Mussen, P. H. (ed), Handbook of Child Psychology: Formerly Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Manacorda, M., We, A., Becker, S., Bennardo, A., Card, D., Boca, D. D.et al. (2006) Why do most Italian youths live with their parents? Intergenerational, 4, 800–829. [Google Scholar]

- McHale, J. P. and Rasmussen, J. L. (1998) Coparental and family group-level dynamics during infancy: early family precursors of child and family functioning during preschool. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 39–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcleroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A. and Glanz, K. (1988) An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education & Behavior, 15, 351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson, V., Pilato, K. A. and Davison, C. M. (2021) Family as a health promotion setting: a scoping review of conceptual models of the health-promoting family. PLoS One, 16, e0249707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A. and Aromataris, E. (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi, M., Abajobir, A. A., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abd-Allah, F., Abera, S. F.et al. (2017) Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet, 390, 1151–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndiaye, K., Silk, K. J., Anderson, J., Horstman, H. K., Carpenter, A., Hurley, A.et al. (2013) Using an ecological framework to understand parent-child communication about nutritional decision-making and behavior. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 41, 253–274. [Google Scholar]

- Niermann, C. Y. N., Gerards, S. M. P. L. and Kremers, S. P. J. (2018) Conceptualizing family influences on children’s energy balance-related behaviors: Levels of Interacting Family Environmental Subsystems (The LIFES Framework). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dwyer, M. V, Fairclough, S. J., Knowles, Z. and Stratton, G. (2012) Effect of a family focused active play intervention on sedentary time and physical activity in preschool children. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L.et al. (2020) Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18, 2119–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A. and McEwen, S. A. (2014) A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5, 371–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas, N. V., Amorim, M. and Dunifon, R. E. (2020) Historical trends in children living in multigenerational households in the United States: 1870–2018. Demography, 57, 2269–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, K. J. and Skelton, J. A. (2018) Family functioning and childhood obesity treatment: a family systems theory-informed approach. Academic Pediatrics, 18, 620–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reher, D. and Requena, M. (2018) A global perspective: living alone in later life. Population and Development Review, 44, 427–454. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R. E., Guerrero, M. D., Vanderloo, L. M., Barbeau, K., Birken, C. S., Chaput, J. P.et al. (2020) Development of a consensus statement on the role of the family in the physical activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviours of children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17, 74. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00973-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett, D. and Holland, W. (1975) Controversy in the detection of disease. Lancet, 306, 357–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R., Lippke, S. and Luszczynska, A. (2011) Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA). Rehabilitation Psychology, 56, 161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seabra, A. F., Mendonça, D. M., Göring, H. H. H., Thomis, M. A. and Maia, J. A. (2008) Genetic and environmental factors in familial clustering in physical activity. European Journal of Epidemiology, 23, 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secker-Walker, R. H., Flynn, B. S., Solomon, L. J., Skelly, J. M., Dorwaldt, A. L. and Ashikaga, T. (2000) Helping women quit smoking: results of a community intervention program. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 940–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R. (2013) The family and family structure classification redefined for the current times. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 2, 306–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields, L. B. E., Wilson, K. C., Hester, S. T. and Honaker, J. T. (2019) Impact of parenting on the development of chronic diseases in adulthood. Medical Hypotheses, 124, 75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindall, C. (1997) Health promotion and the family. Health Promotion International, 12, 259–260. [Google Scholar]

- Skelton, J. A., Buehler, C., Irby, M. B. and Grzywacz, J. G. (2012) Where are family theories in family-based obesity treatment? Conceptualizing the study of families in pediatric weight management. International Journal of Obesity, 36, 891–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohun, R., MacPhail, A. and MacDonncha, C. (2021) Physical activity parenting practices in Ireland: a qualitative analysis. Sport, Education and Society, 26, 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Moore, E., Toumpakari, Z., Sebire, S. J., Thompson, J. L., Lawlor, D. A. and Jago, R. (2018) Roles of mothers and fathers in supporting child physical activity: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study. BMJ Open, 8, e019732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, F., Hartman, A., Graubard, B., Gilpin, E., Chavis, D., Garcia, J.et al. (1999) The American Stop Smoking Intervention Study: conceptual framework and evaluation design. Evaluation Review, 23, 259–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo, R. (2011) A checklist to define the psychological processes. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 20, 321–327. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/checklist-define-psychological-processes-una/docview/1677638284/se-2 (last accessed 6 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P. A., Lodge, A. C. and Reczek, C. (2019) Do support and strain with adult children affect mothers’ and fathers’ physical activity? Research on Aging, 41, 164–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D.et al. (2018) PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ryn, M. and Heaney, C. A. (1992) What’s the use of theory? Health Education Quarterly, 19, 315–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterworth, J. C., Hutchinson, J. M., Buchholz, A. C., Darlington, G., Randall Simpson, J. A. and Ma, D. W.; Guelph Family Health Study. (2017) Food parenting practices and their association with child nutrition risk status: comparing mothers and fathers. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 42, 667–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild, R. A., Taylor, E. L., Knehans, A. and Cleaver, V. (1994) Matriarchal model for cardiovascular prevention. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 49, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2014) Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/148114/9789241564854_eng.pdf (last accessed 6 May 2022).

- World Health Organization. (2018) Noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (last accessed 6 May 2022).

- Wyszynski, C. M., Bricker, J. B. and Comstock, B. A. (2011) Parental smoking cessation and child daily smoking: a 9-year longitudinal study of mediation by child cognitions about smoking. Health Psychology, 30, 171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee, A. Z. H., Lwin, M. O. and Ho, S. S. (2017) The influence of parental practices on child promotive and preventive food consumption behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacarías, G., Shamah-Levy, T., Elton-Puente, E., Garbus, P. and García, O. P. (2019) Development of an intervention program to prevent childhood obesity targeted to Mexican mothers of school-aged children using intervention mapping and social cognitive theory. Evaluation and Program Planning, 74, 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.