Abstract

To explore the role of neutrophil phagocytosis in host defense against Bordetella pertussis, bacteria were labeled extrinsically with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or genetically with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and incubated with adherent human neutrophils in the presence or absence of heat-inactivated human immune serum. In the absence of antibodies, FITC-labeled bacteria were located primarily on the surface of the neutrophils with few bacteria ingested. However, after opsonization, about seven times more bacteria were located intracellularly, indicating that antibodies promoted phagocytosis. In contrast, bacteria labeled intrinsically with GFP were not efficiently phagocytosed even in the presence of opsonizing antibodies, suggesting that FITC interfered with a bacterial defense. Because FITC covalently modifies proteins and could affect their function, we tested the effect of FITC on adenylate cyclase toxin activity, an important extracellular virulence factor. FITC-labeled bacteria had fivefold-less adenylate cyclase toxin activity than did unlabeled wild-type bacteria or GFP-expressing bacteria, suggesting that FITC compromised adenylate cyclase toxin activity. These data demonstrated that at least one extracellular virulence factor was affected by FITC labeling and that GFP is a more appropriate label for B. pertussis.

Bordetella pertussis is the obligate human pathogen that causes whooping cough. This organism produces a battery of virulence factors such as pertactin, BrkA, filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), fimbriae, adenylate cyclase toxin, tracheal cytotoxin, pertussis toxin, and dermonecrotic toxin (20). These factors are either adhesins or toxins that mediate colonization of respiratory tract epithelial cells or resistance to host defenses.

Immunity to B. pertussis is mediated through natural infection or vaccination with whole-cell or acellular vaccines. The mechanism of protection, however, is not completely understood (11, 16). Neutralization of pertussis toxin and blocking of bacterial attachment to ciliated cells are likely to be important in immunity, but opsonization, phagocytosis, and bacterial killing also may play a role in protection. We are interested in studying the role of human antibodies against B. pertussis virulence factors in promoting opsonization and phagocytosis.

To measure phagocytosis of B. pertussis by human neutrophils, we needed to develop an assay that distinguished intracellular from extracellular bacteria. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) labeling of microorganisms has been used extensively as a convenient way to visualize bacteria interacting with mammalian cells (4, 8, 9). Basically, bacteria labeled with FITC are incubated with the mammalian cells of interest and then counterstained with ethidium bromide; intracellular FITC-labeled bacteria resist staining with ethidium bromide and remain green, but extracellular ethidium bromide-labeled bacteria appear orange by fluorescence microscopy (4, 8, 9). FITC covalently binds primary amines of amino acids present on the N terminus of proteins and on lysine residues. It labels only amines in the free base (uncharged) state, and a high pH (>8) is used to increase the efficiency of FITC labeling. We were concerned that FITC labeling could give misleading results by either modifying proteins critical to the function of a biologically important protein or affecting the viability of the bacteria. In this study, we compared FITC and green fluorescent protein (GFP) labeling of live B. pertussis to determine whether either labeling procedure had an effect on phagocytosis of opsonized and nonopsonized bacteria.

Labeling bacteria with FITC.

Bacteria were labeled by a modification of the procedure of Hazenbos et al. (8). Bacteria from overnight cultures on Bordet-Gengou agar (BGA; Difco, Detroit, Mich.) were harvested with Dacron swabs (Fisher, Pittsburgh, Pa.), suspended into phosphate-buffered saline, and adjusted to an A600 of 1 or about 2 × 109 bacteria/ml. Bacteria (2 × 108) were transferred to a microcentrifuge tube, pelleted, and suspended in 1 ml of FITC (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) (0.5 mg/ml) in 50 mM sodium carbonate–100 mM sodium chloride at various pH values. Bacteria were incubated for 20 min at room temperature, washed three times in 1 ml of HBSA (Hanks’ buffer [Biowhittaker, Walkersville, Md.] supplemented with 0.25% bovine serum albumin [Sigma] and 2 mM HEPES [Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif.]) at 34,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and then suspended in 100 μl of HBSA.

We examined the effect of pH on FITC labeling and on fluorescence intensity and viability. Bacteria labeled at pH 7.7, 8, 8.5, 9, and 10.5 were easily visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Bacterial survival was determined by plating on BGA; no loss in viability was observed, except at pH 10.5, where <1% survived. The bacteria were labeled at pH 8 for all other experiments.

The effects of ethidium bromide staining also were examined. Bacteria incubated for 5 or 30 min with ethidium bromide (50 μg/ml in Hanks’ buffer) appeared orange with a bright central stain, suggesting that the stain penetrates the membranes and binds to the DNA of B. pertussis. Incubation with ethidium bromide affected bacterial viability; <10% of the wild-type bacteria survived both the 5- and the 30-min treatments.

Labeling bacteria with GFP.

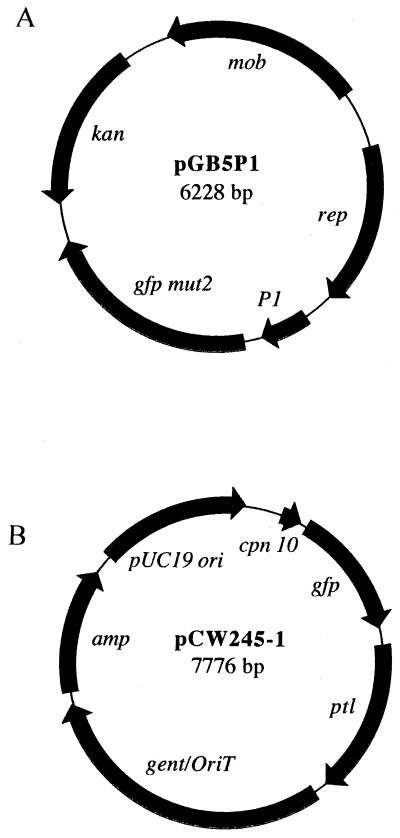

An alternative method, cytoplasmic expression of GFP, has been used to label bacteria to study bacterial interactions with mammalian cells (3, 18). We used two constructs, pGB5P1 and pCW245-1 (Fig. 1), for the cytoplasmic expression of GFP. Plasmid pGB5P1 was introduced into wild-type BP338 (22) by electroporation by a modification of the method of Zealey et al. (25). Briefly, bacteria were grown in 500 ml of Stainer-Scholte (SS) broth at 37°C for 72 h with rotation. Bacteria were harvested (11,350 × g), washed twice in sterile distilled water and once in 272 mM sucrose–15% glycerol (SG), suspended in 10 ml of SG, and stored at −80°C in 600-μl aliquots. Plasmid pGB5P1 DNA (10 μg) was added to competent bacteria, pulsed at 2.5 kV (Bio-Rad Escherichia coli pulser) with an electrode gap of 0.2 cm, transferred to 5 ml of SS broth, and incubated at 37°C for 1 h with rotation. The culture was divided among five microcentrifuge tubes, pelleted at 5,160 × g for 5 min, suspended in 100 μl of SS broth, and plated onto BGA and kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and nalidixic acid (30 μg/ml) to select for resistant electroporants. Plasmid pCW245-1 was introduced into the chromosome of wild-type BP338 and adenylate cyclase toxin mutant BP348 (22) by triparental mating as previously described (19) with the pertussis toxin homologous region, resulting in strains BP338 ptl::pCW245-1 and BP348 ptl::pCW245-1, respectively. Western blot analysis with an S1 monoclonal antibody, C3X4 (14), has shown that recombination at the end of the operon does not affect pertussis toxin expression (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Constructs for GFP expression. (A) pGB5P1. The gfp-mutant 2 gene (2) was cloned as a BamHI-EcoRI restriction fragment into the pBBR1MCS-2 vector (15). A Sau3A restriction fragment that encodes a constitutive B. pertussis promoter was cloned upstream to control gfp expression. (B) pCW245-1. Nucleotides 1 to 251 from the B. pertussis cpm 10 (5) promoter were amplified by PCR, and the product was digested with PstI and HaeIII and then cloned into pGFPuv to control gfp expression, generating pCW211-6. A PstI restriction fragment (nucleotides 11810 to 13025) from the end of the ptl operon was cloned into pUW2139 [pBluescript SK(+) containing gent/oriT], and the resulting construct, pCW204-1, was digested with ApaI and ligated with pCW211-6 to generate pCW245-1. Plasmid CW245-1 was introduced into bacteria by triparental mating as previously described (19), and transformants were selected on BGA, nalidixic acid, and gentamicin (30 μg/ml). Abbreviations: mob, mobilizable gene; rep, plasmid replication; gfp mut2, green fluorescent protein mutant 2; P1, B. pertussis constitutive promoter; kan, kanamycin; cpm 10, chaperonin 10 (B. pertussis GroES homologue); ptl, pertussis toxin liberation; gent/oriT, gentamicin/origin of transfer; amp, ampicillin.

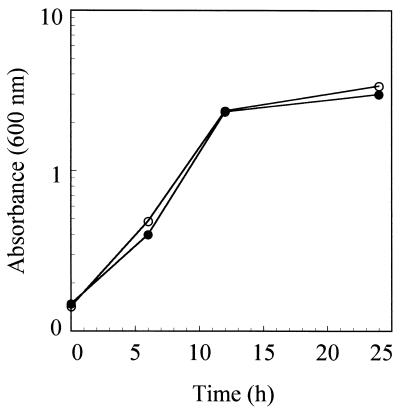

Expression of GFP did not affect bacterial growth. In Fig. 2, the growth rates of wild-type strain BP338 and strain BP338(pGB5P1) expressing GFP were identical. The expression of virulence factors was not affected by GFP expression; BP338(pGB5P1) was hemolytic and expressed pertussis toxin, lipopolysaccharide, pertactin, BrkA, and FHA at levels comparable to those for the parental strain by Western blotting or protein gel electrophoresis (data not shown). BP338 ptl::pCW245-1 also was similar to the wild type in growth rate and protein expression. Therefore, GFP does not seem to adversely affect bacterial growth or gene expression.

FIG. 2.

Effect of GFP on growth. Bacteria from overnight BGA were suspended into SS broth to an A600 of 0.1. Five milliliters of the BP338 and BP338(pGB5P1) suspensions was distributed to BGA containing nalidixic acid and nalidixic acid with kanamycin, respectively, and cultures were incubated at 37°C. Bacteria were harvested at 6, 12, and 24 h and washed, and the absorbance was measured. ○, BP338; ●, BP338(pGB5P1).

Phagocytosis assay.

Human neutrophils were purified as previously described (10) and quantified on a hemacytometer. Neutrophils (5 × 105/well in 1 ml of HBSA) were permitted to adhere to round glass coverslips in 24-well plates for 1 h at 37°C in 5% CO2.

To investigate the role of opsonization by antibodies in the absence of complement, serum sample 13 (24) was heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min. This serum is a previously characterized serum sample from an individual with occupational exposure to B. pertussis and has antibodies to B. pertussis lipopolysaccharide as well as several surface-localized protein virulence factors.

Overnight BGA cultures of wild-type or GFP-expressing bacteria were harvested and labeled with FITC where indicated. Bacteria (3 × 106 in 30 μl) were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes and incubated with human immune serum (30 μl) or HBSA buffer at 37°C for 15 min. Bacterial suspensions were adjusted to 400 μl with HBSA, added to 5 × 105 adherent neutrophils, and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 1 h. The suspensions were aspirated, and the neutrophils were washed once with 1 ml of HBSA to remove unattached bacteria. To stain bound but not ingested bacteria, ethidium bromide (50 μg/ml in 1 ml of Hanks’ buffer) was added for 5 min at room temperature and then removed by aspiration. Neutrophils were fixed and mounted as previously described (17). Phagocytosis was quantified by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy on a Zeiss microscope with a 09 filter set (wide band pass exciter, 450 to 490; long pass emission, 520 and above). Each assay was performed three times in duplicate.

Comparison of labeling treatments.

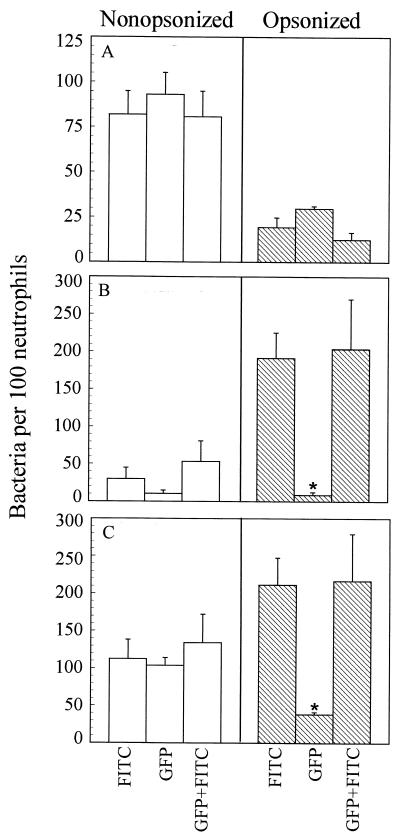

The number of extracellular adherent bacteria was similar for both labeling conditions, about 80 bacteria attached per 100 neutrophils (Fig. 3A, open bars). Interestingly, fewer adherent bacteria were observed following opsonization (Fig. 3A, striped bars), suggesting that adhesin-mediated attachment (i.e., by FHA or pertactin) may be more efficient than Fc-mediated attachment.

FIG. 3.

Effect of labeling treatments on phagocytosis. One hundred consecutive neutrophils were counted by fluorescence microscopy. (A) Number of orange (extracellular adherent) bacteria per 100 neutrophils. (B) Number of green (intracellular; phagocytosed) bacteria per 100 neutrophils. (C) Total association; number of orange and green bacteria per 100 neutrophils. FITC, BP338 labeled with FITC. GFP, BP338(pGB5P1). GFP+FITC, BP338(pGB5P1) labeled with FITC. Data were analyzed by the Student t test. Each bar represents the mean (± standard error of the mean). ∗, significantly different from the FITC labeling treatment (P < 0.05).

Phagocytosis was also examined in the absence of antibodies; about 30 FITC-labeled BP338 bacteria and about 10 GFP-expressing bacteria per 100 neutrophils were phagocytosed (Fig. 3B, open bars). As a point of reference, this is only about 5 and 2% of the total bacterial inoculum, respectively. When FITC-labeled BP338 bacteria were opsonized with heat-inactivated human immune serum, six times more bacteria were phagocytosed (Fig. 3B, striped bars). However, unlike the FITC-labeled bacteria, opsonization with immune serum did not increase the efficiency of phagocytosis of the GFP-expressing bacteria. Total bacterial association is shown in Fig. 3C.

These results suggested that FITC labeling interfered with the ability of B. pertussis to evade phagocytosis. We tested this hypothesis by labeling GFP-expressing BP338 with FITC. The results with these bacteria were comparable to those with the FITC-labeled wild-type bacteria. This is most apparent when phagocytosis of the opsonized bacteria is compared (Fig. 3B, striped bars).

Adenylate cyclase toxin activity assay.

Adenylate cyclase toxin is an important virulence factor for B. pertussis, and without it, B. pertussis is avirulent (7, 21, 23). The toxin enters phagocytic cells, elevates cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels, and subsequently paralyzes immune defenses such as chemotaxis, phagocytosis, superoxide generation, and microbial killing (1, 6, 13). Because FITC-labeled BP338 seemed to have an altered ability to resist phagocytosis, it was possible that FITC labeling modified adenylate cyclase toxin activity. Therefore, adenylate cyclase toxin activity in bacterial suspensions was measured as [α-32P]ATP converted to [32P]cAMP as previously described (12). BP338 and GFP-expressing BP338 had comparable adenylate cyclase toxin activity, but FITC-labeled BP338 adenylate cyclase toxin activity was reduced fivefold (Table 1), suggesting that FITC modified the adenylate cyclase toxin activity. No activity was seen in BP348 ptl::pCW245-2, the adenylate cyclase toxin mutant expressing GFP.

TABLE 1.

Effect of labeling treatments on adenylate cyclase activity

| Organism | pmol of cAMP/min/107 bacteriab |

|---|---|

| BP338 | 5,520 (±425) |

| BP338 plus FITCa | 1,200 (±69)c |

| BP338 ptl::pCW245-1 | 6,840 (±408) |

| BP348 ptl::pCW245-1 | 0 (±4)c |

Bacteria were labeled with FITC at pH 8.

Data in parentheses are standard errors of the means.

Significantly different from BP338 (P < 0.05). Data were analyzed by Student’s t test.

Our studies suggest that FITC labeling compromised at least one extracellular virulence factor, adenylate cyclase toxin. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other proteins were affected. Such alterations allowed neutrophils to efficiently phagocytose B. pertussis, providing misleading results. Clearly, GFP is more appropriate than FITC for labeling B. pertussis and studying interactions with human phagocytes. Therefore, care should be taken when using labeled bacteria in phagocytosis assays. Future studies involving GFP-expressing B. pertussis are in progress to study the role of human antibodies against B. pertussis virulence factors in promoting opsonization and phagocytosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Kidd for her help with blood donations and cell preparations.

This work was supported in part by grant RO1 AI38415 to A.A.W. and AI37639 to S.N.

REFERENCES

- 1.Confer D L, Eaton J W. Phagocyte impotence caused by an invasive bacterial adenylate cyclase. Science. 1982;217:948–950. doi: 10.1126/science.6287574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cormack B P, Valdivia R H, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhandayuthapani S, Via L E, Thomas C A, Horowitz P M, Deretic D, Deretic V. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression and cell biology of mycobacterial interactions with macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:901–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drevets D A, Campbell P A. Macrophage phagocytosis: use of fluorescence microscopy to distinguish between extracellular and intracellular bacteria. J Immunol Methods. 1991;142:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90289-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez R C, Weiss A A. Cloning and sequencing of the Bordetella pertussis cpn10/cpn60 (groESL) homolog. Gene. 1995;158:151–152. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00106-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman R L, Fiederlein R L, Glasser L, Galgiani J N. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase: effects of affinity-purified adenylate cyclase on human polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions. Infect Immun. 1987;55:135–140. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.135-140.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodwin M S, Weiss A A. Adenylate cyclase toxin is critical for colonization and pertussis toxin is critical for lethal infection by Bordetella pertussis in infant mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3445–3447. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3445-3447.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazenbos W L, van den Berg B M, van’t Wout J W, Mooi F R, van Furth R. Virulence factors determine attachment and ingestion of nonopsonized and opsonized Bordetella pertussis by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4818–4824. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4818-4824.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hed J. Methods for distinguishing ingested from adhering particles. Methods Enzymol. 1986;132:198–204. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(86)32008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henson P M, Zanlolari B, Schwartzman N A, Hong S R. Intracellular control of human neutrophil secretion. J Immunol. 1978;121:851–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewlett E L. Pertussis: current concepts of pathogenesis and prevention. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:S78–S84. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199704001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewlett E L, Urban M A, Manclark C R, Wolff J. Extracytoplasmic adenylate cyclase of Bordetella pertussis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:1926–1930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.6.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khelef N, Zychlinsky A, Guiso N. Bordetella pertussis-induced apoptosis in macrophages: role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4064–4071. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4064-4071.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim K J, Burnette W N, Sublett R D, Manclark C R, Kenimer J G. Epitopes on the S1 subunit of pertussis toxin recognized by monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1989;57:944–950. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.944-950.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kovach M E, Elzer P H, Hill S D, Robertson T G, Farris M A, Roop II R M, Peterson K M. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistant cassettes. Gene. 1995;66:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plotkin S A, Cadoz M. The acellular pertussis vaccine trials: an interpretation. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:508–517. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnur R A, Newman S L. The respiratory burst response to Histoplasma capsulatum by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1990;144:4765–4772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valdivia R H, Hromockyj A E, Monack D, Ramakrishnan L, Falkow S. Applications for green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the study of host-pathogen interactions. Gene. 1996;173:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker K E, Weiss A A. Characterization of the dermonecrotic toxin in members of the genus Bordetella. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3817–3828. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3817-3828.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss A A. Mucosal immune defenses and the response of Bordetella pertussis. ASM News. 1996;63:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss A A, Goodwin M S. Lethal infection by Bordetella pertussis mutants in the infant mouse model. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3757–3764. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.12.3757-3764.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss A A, Hewlett E L, Myers G A, Falkow S. Tn5-induced mutations affecting virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1983;42:33–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.33-41.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss A A, Hewlett E L, Myers G A, Falkow S. Pertussis toxin and extracytoplasmic adenylate cyclase as virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:219–222. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss A A, Mobberley P S, Fernandez R C, Mink C M. Characterization of human bactericidal antibodies to Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1424–1431. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1424-1431.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zealey G R, Loosmore S M, Yacoob R K, Boux L J, Miller L D, Klein M H. Gene replacement in Bordetella pertussis by transformation with linear DNA. Bio/Technology. 1990;8:1025–1029. doi: 10.1038/nbt1190-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]