Abstract

Purpose:

In the current work, the RBE of a 212Pb conjugated anti-HER2/neu antibody construct has been evaluated, in vitro, by colony formation assay. The RBE was estimated by comparing two absorbed dose-survival curves: the first obtained from the conjugated 212Pb experiments (test radiation), the second obtained by parallel experiments of single bolus irradiation of external beam (reference radiation).

Materials and Methods:

Mammary carcinoma NT2.5 cells were treated with (0-3.70) kBq/ml of radiolabeled antibody. Non-specific binding was assessed with addition of excess amount of unlabeled antibody. The colony formation curves were converted from activity concentration to cell nucleus absorbed dose by simulating the decay and transport of all daughter and secondary particles of 212Pb, using the Monte Carlo code GEANT 4.

Results:

The radiolabeled antibody yielded an RBE of 8.3 at 37 % survival and a survival independent RBE (i.e., RBE2) of 9.9. Unbound/untargeted 212Pb-labeled antibody, as obtained in blocking experiments yielded minimal alpha-particle radiation to cells.

Conclusions:

These results further highlight the importance of specific targeting towards achieving tumor cell kill and low toxicity to normal tissue.

Keywords: alpha-particle, LET radiation, RBE, radiosensitivity

Introduction

Radiopharmaceutical Therapy (RPT), and particularly, alpha-particle emitter RPT (αRPT) has gained considerable recent attention as a novel treatment approach that has the potential to overcome limitations of current, widely used cancer therapeutics (Thorp-Greenwood & Coogan 2011; Yong & Brechbiel 2015; Kasten et al. 2018; Sgouros et al. 2020). Alpha-emitter RPT delivers highly potent, short-ranged (50-100 μm) alpha-particle emissions. Their traversal through tissue results in a very high-density energy deposition pattern, characterized as high linear energy transfer (LET). The resulting ionization pattern leads to complex DNA damage, including double strand breaks (DSB), single strand breaks (SSB) and DNA base damage. The predominant mode of lethal damage are the DNA DSBs, that are more difficult to repair than the ones caused by other agents (Sgouros et al. 2010; Eccles et al. 2011; Nikitaki et al. 2016). Accordingly, the energy deposition pattern leads to biological effects per unit absorbed dose that are greater than would be observed for beta-particle or photon (i.e., low LET) radiation. This increased biological effect per unit absorbed dose is represented as the relative biological effectiveness (RBE); RBE is defined as the absorbed dose ratio of a reference radiation to a test radiation that leads to a particular biological endpoint (Barendsen et al. 1960; Barendsen & Beusker 1960; Elgqvist et al. 2014; R. Meredith et al. 2014; Milenic et al. 2015). Assessment of the RBE for different αRPTs targeting different cancers is essential to establishing absorbed dose vs response relationships in patients that are applicable across all RPTs. The latter is necessary for implementing a treatment-planning approach to delivering αRPT and also allows for dosimetry-driven combination αRPT with β-particle emitting RPT or with external beam radiotherapy.

Amongst the many alpha-particle emitting radionuclides that could be utilized for αRPT, a relatively small number currently have the practical features such as a reasonable half-life (~hours to weeks), required radiolabeling stability and yield, and availability that can support widespread clinical use in an economically feasible manner (Thorp-Greenwood & Coogan 2011). Lead-212 (212Pb), a beta-particle emitter, has a half-life of 10.64 hours and is the parent nuclide of 212Bi, an alpha-particle emitter with a half-life of 60.6 minutes. Therefore, by using 212Pb the time to deliver the alpha-particles to the tumor cells is extended and the required administered activity is reduced relative to the amount required if 212Bi itself were to be administered (Milenic et al. 2015).

RBE values for 212Pb are limited, and those that exist were not obtained using cell-targeting αRPT agents (Rotmensch et al. 1989; Azure et al. 1994; Howell et al. 1994). In the current work, the RBE of a 212Pb conjugated anti-rat HER2/neu antibody construct has been evaluated, in vitro. A recently published approach to specifying RBE is applied that removes the dependence of RBE on the chosen surviving fraction (Hobbs et al. 2014).

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Instruments

Cell Line: The rat HER-2/neu expressing cell line used for the in vitro studies was derived from spontaneous mammary tumors in female neu-N mice (Reilly et al. 2000; Reilly et al. 2001; Song et al. 2008). Media: The NT2.5 cell line was cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Corning, Manassas, VA, USA) with 20.0 % Fetal Bovine Serum, FBS (Corning, Manassas, VA, USA), 1.2 % HEPES (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland, UK), 1.0 % L-glutamine (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland, UK), 1.0 % Minimum Essential Medium Non-Essential Amino Acids, MEM NEAA (Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA), 1.0 % sodium pyruvate (Gibco, Grand Island, New York, USA), 0.02 % insulin, human recombinant, zinc solution (Gibco, India) and 0.02 % gentamicin sulfate (MP Biomedicals, USA), at 37°C in 5 % CO2. Antibody: The anti-human/rat HER2/neu monoclonal antibody, 7.16.4, was used (BioXCell, West Lebanon, New Hampshire, USA). Chelators: p-SCN-Bn-TCMC (2-(4-isothiocyanotobenzyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraaza-1,4,7,10-tetra-(2-carbamoylmethyl)-cyclododecane) and p-SCN-Bn-DTPA (S-2-(4-Isothiocyanatobenzyl)-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid) were purchased from Macrocyclics Inc., Plano, Texas, USA. Lead-212, 212Pb was purchased from OranoMed, Plano, Texas, USA and In-111, was purchased from MDS Nordion (Vancouver, BC, Canada). Activity determinations were performed using a gamma well counter (PerkinElmer 2470, WIZARD2 Automatic Gamma Counter, Massachusetts, USA). The rest of the chemicals used for the experiments were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (Saint Louis, Missouri, USA) or Thermo Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, USA), unless otherwise specified. All aqueous solutions were prepared with ultrapure water.

Radiolabeling

The 7.16.4 anti-HER2/neu antibody was conjugated to the DTPA chelator for 111In radiolabeling and to the TCMC chelator for 212Pb labeling. The antibody was conjugated to the bifunctional chelators TCMC and DTPA using freshly made buffer solutions. An aliquot of each chelator was dissolved in carbonate buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3 and 5 mM Na2CO3.H2O for TCMC; 500 mM NaHCO3, 21.2 mM Na2CO3.H2O and 1.5 M NaCl for DTPA, pH 9 and 8 respectively), made with double-distilled water, in order to make a 10 mg/ml solution (Westrøm et al. 2017). Then the amount of the antibody needed for conjugation was mixed with 1.7-fold volume excess of the conjugation buffer and vortexed. Twenty and 40-fold molar excess of the TCMC and DTPA chelator solutions, respectively, were added to the antibody solution and left overnight, at room temperature to react. The antibody-chelator mixture was purified by centrifuging three times at 3500 rpm for 12-14 minutes each time, using centrifugation buffer (0.15M NaCl and 0.02 M NaOAc, pH 7). The protein concentration was determined by Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, Delaware, USA). The conjugated antibodies were tested and could be used when properly preserved at 4 °C, for at least 3 weeks.

The Pb-212 radiolabeling was carried out by mixing the radioactive material, 212Pb, which was received in a mixture of NH4OAc and ascorbic acid solution, with the conjugated antibody in a 37:1 (kBq of 212Pb:μg of conjugated antibody) ratio, at 37 °C, for at least 15 minutes. The 111In labeling was performed in a 148-185:1 [111In]InCl3 to conjugated antibody ratio, at 37 °C, for at least 30 minutes. The radiolabeled antibody was then purified by centrifugation. The resulting yield and radiochemical purity were determined by instant Thin Layer Chromatography (iTLC with silica gel impregnated paper, German Science) analysis using the gamma well counter (Baidoo et al. 2013; Schneider et al. 2013; R.F. Meredith et al. 2014a; Westrøm et al. 2017; Stallons et al. 2019).

Immunoreactivity Assay

NT2.5 cells were trypsinized, counted, centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 3 minutes to form a cell pellet and resuspended in medium, in order to prepare 2 identical microcentrifuge tubes containing 5-6 x106 cells/100 μl each. 8 or 100 ng of the radiolabeled antibodies 212Pb-TCMC-7.16.4 or 111In-DTPA-7.16.4, respectively, were added to the first tube, following a 30-minute incubation period, at 4 °C for both tubes. The cells were centrifuged to form cell pellets and the supernatant fraction was transferred to the second tube for another 30-minute incubation period, at 4 °C. Both cell pellets were washed twice with PBS and the medium, washes and cell pellets were collected and counted in the gamma well counter. The % immunoreactive fraction of the labeled antibody was estimated by dividing the sum of the activity in both cell pellets by the total activity of the samples collected (Gustafsson-Lutz et al. 2017).

Saturation Binding

Binding was assayed, by seeding NT2.5 cells into two 24-well plates at a density of 1.5x105 cells per well and allowing them to attach overnight. The next day the cells were washed with PBS, fresh medium was added and then half of the wells were blocked, with 10 μg/ml of either unlabeled conjugated or unconjugated Ab. The plates were then incubated for at least 30 minutes, at 4 °C. To obtain an accurate measure of cell surface binding sites, we incubated the cells at 4 °C to prevent internalization. Afterwards, all cells were treated with one of seven different concentrations (0.25-25) nM of the radiolabeled antibody (111In-DTPA-7.16.4, 3 replicates per condition). The plates were incubated for 3-4 hours, at 4 °C. Post-incubation, the cells were washed twice with PBS and then lysed with 0.5 % of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The cell solutions were pipetted off in gamma counting tubes and then counted for activity.

We used the Pierce BCA Protein assay to determine the protein concentration of the cell lysates. The Michaelis-Menten equation was fitted to the binding curve to estimate maximum specific binding, Bmax and the equilibrium dissociation constant, KD.

In vitro Proliferation Assay

A high throughput colorimetric cell proliferation assay was performed, utilizing the tetrazolium salt WST-8. NT2.5 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1000 cells per well and allowed to attach overnight. After overnight incubation, the medium was removed and half of the cells were blocked with 10 μg/ml of either unlabeled conjugated or unconjugated Ab, and for the other half fresh medium was added to the wells. The cells were then incubated overnight. The reduction in proliferation due to radiolabeled antibody exposure was determined following treatment of the cells with serially diluted 212Pb-TCMC-7.16.4 (0-7.40 kBq/ml). The cells were continuously incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 at 37°C for up to 5 days. Each day post-treatment, the cells of a 96-well plate were treated with the colorimetric cell viability kit (CCVK-I, PromoCell GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) for one hour. Cell absorbance was subsequently measured using a plate reader at 450/620 nm (Spectrophotometer Plate Reader, Beckman Coulter AD340C). The absorbance (450 nm) of the dye formazan is proportional to the number of metabolically active cells and thus the proliferation assay was used as a high throughput measure of cell number and a surrogate of the colony formation assay (Yard et al. 2019).

In vitro Colony Formation Assay (CFA)

The colony formation assay was performed as previously described (Yu, Lu, Jessie R. Nedrow, et al. 2020). Mammary carcinoma NT2.5 cells were seeded into two six-well plates at a density of 0.7x106 cells per well and allowed to attach overnight. The next day the old medium was removed from the wells of one of the plates and the cells were blocked with 10 μg/ml of unlabeled Ab. Five hours later, the cells in both six-well plates were treated with (0, 0.185, 0.370, 0.925, 1.85 and 3.70) kBq/ml of radiolabeled antibody (212Pb-TCMC-7.16.4), respectively. Following overnight incubation (24 hours), the medium was removed, the cells were washed twice with 1000 μl of PBS, trypsinized (2.5 % trypsin) and replated (100-10,000 cells/well depending on the dose) in six-well plates; having 6 replications per condition. The cells were continuously incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5 % CO2 at 37°C for 7 days. Visible colonies were washed twice with PBS and stained with 0.5 % crystal violet in methanol. Colonies containing over 50 cells were manually counted.

Fluorescent and Phase Contrast Imaging for Cell and Nuclei Radii Determination

NT2.5 cells were seeded in a six-well plate at a density of 0.05-8x106 cells per well and allowed to attach and proliferate for 3 days. Once the confluency of the cells reached 40-60 %, the cells were washed, treated with the fluorescent Hoechst 33342 dye and incubated in 5 % CO2, at 37°C for 20 minutes. The cells were then washed twice with PBS, counted, trypsinized and resuspended in 0.6 ml fresh medium per 0.6-0.8x106 cells. Aliquots of the single cell suspension were transferred into cell counting chamber slides for imaging (Nikon epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Nikon Intensilight C-HGFI lamp, Melville, NY). The images were processed using the Nikon Imaging Software Elements. Average numbers of cell and nuclei radii were used for the absorbed dose calculations below.

Absorbed Dose and Relative Biological Effectiveness

The colony formation curves were converted from activity concentration to cell nucleus absorbed dose by simulating the decay and transport of all daughter and secondary particles of 212Pb using the Monte Carlo code GEANT 4 (version 10.06 patch 2) (Allison et al. 2016). To this end, cells and their nuclei were idealized as concentric spheres with radii of (8.8 and 4.1) μm, respectively, as determined by the fluorescent and phase contrast imaging described above. The total number of cells in each well was estimated as the number of seeded cells, which were subsequently allowed to proliferate for 24 hours. The cell doubling time was set to 26 hours as determined by counting experiments (Karimian et al. 2020). To confirm the total number of cells a control plate was seeded. The cells in the control plate were left to proliferate for the same amount of time as the cells used in the colony formation assay. Twenty four hours later (i.e., equal to time between seeding and treatment), the control plate was used to determine the protein concentration (number of cells), utilizing the Pierce BCA Protein assay kit. The cells were maximally spaced out over the surface of the well in a regular hexagonal pattern.

The 212Pb-TCMC-antibodies were assumed to be in one of three possible locations: unbound in the medium, bound to a cell membrane, or internalized into the cytosol. The S-values for each of these compartments to the nucleus in the target cell (self-dose) and from neighboring cells (cross-dose) were calculated by running simulations, in which all energy (except recoil energy) deposited in the nucleus was tallied, divided by the nucleus mass, and averaged over the total number of simulated decays to arrive at each specific S-value. At least 1 million primary decays were simulated per cell for each source, except for the S-value for unbound antibodies, for which 100 million primary decays in the media were simulated. Cut value for each particle was set to 1 meter, speeding up calculations, and essentially simplifying the alpha particle physics model to the continuous slowing down approximation. The S-values for membrane and cytosol self-dose were validated by direct comparison to the corresponding values in MIRDcell (Vaziri et al. 2014).

To obtain the actual absorbed dose, the time-integrated activity in each compartment needed to be estimated. The number of membrane-bound antibodies per cell was estimated for each experimental condition using simple equilibrium equations for antibody binding, and the parameters KD and Bmax, as measured with the saturation binding assay. KD was corrected for differences in immunoreactivity between 212Pb-antibody and 111In-antibody (Denoël et al. 2019). In addition, internalization was accounted for (59.2 %) (Song et al. 2008). All remaining unbound antibodies were assumed to be uniformly distributed in the well plate media. Incubation times and antibody specific activity were used to calculate the time integrated activity (TIA; i.e. total number of decays) in each compartment. Specifically, as the surface bound and internalized antibodies were assumed to remain in their locations for the entire duration of the experiment (i.e. 8 days), the TIA was calculated for that period. Conversely, the contributions of cross dose and media dose were assumed to stop after the first post-treatment washing step and replating, which were after 24 hours. The TIA in each compartment and the corresponding S-values were multiplied and then summed to yield absorbed dose for each experimental condition. A monoexponential function was fit to the resulting absorbed dose-survival data.

The RBE was estimated by comparing the absorbed dose-survival curve obtained following external beam experiments using the same cell line, reported previously by our lab (Yu, Lu, Jessie R Nedrow, et al. 2020). RBE values at 10, 37 and 50 % surviving fractions were calculated, as was RBE2 (κ / (α + 2*β)) (Hobbs et al. 2014). This formalism dispenses with the need to specify RBE at a given absorbed dose or equivalently, level of cell kill.

Statistical Analysis

The experiments were performed at least in triplicate and are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The softwares GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, California, USA), as well as SAAM II (The Epsilon Group, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA) were used for graph plotting and statistical analyses (t-test, ANOVA and calculation of uncertainties).

Results

Radiolabeling and Immunoreactive Fraction

The radiochemical yield was > 95 % for the 212Pb, therefore, no further purification was needed. The specific activity was 37.0±0.7 kBq/μg (0.064 kBq/μl). The labeling yield for 111In was equal to 95 % and the radiochemical purity was ≥ 99 %. The specific activity was equal to 170.2±2.6 kBq/μg (0.358 kBq/μl).

The immunoreactive fraction of the 212Pb-antibody as measured, in vitro, against 7.16.4 cells, ranged between 52-61 % and is in agreement with other published results for 212Pb-TCMC-antibodies (Westrøm et al. 2017). The immunoreactivity of 111In-antibody ranged between 70-77 %.

Binding Sites and Affinity

In Figures 1A and 1B the total, non-specific and specific bindings of the rat HER-2/neu expressing cells are represented as a function of the 111In radiolabeled antibody concentration. The curve representing the specific binding was fitted (R2 = 0.99) and the maximum specific binding (Bmax) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) were 0.2712 fmol/1000 cells and 1.344 fmol/1000 cells, respectively. The binding assay gave 1.6x105 receptors per cell, which is in agreement with the literature (Song et al. 2008). The binding constant calculated for the 111In construct was corrected for differences in immunoreactivity to project binding of the 212Pb construct.

Figures 1:

(A) HER-2/neu expressing cell line treated with 111In-DTPA-7.16.4 (0.25-25) nM, in the absence (Total Binding) or presence (Non-specific Binding) of excess amount of unlabeled Ab. (B) Specific binding data, calculated by subtracting non-specific from total binding. The experiments were carried out in triplicates and the values represent the mean ± standard deviation.

In vitro Proliferation Assay

Figures 2 depict the results of the cell proliferation assay and more specifically the absorbance of the tumor cells as a function of incubation time (Figures 2A–C) or activity concentration of the 212Pb-conjugated anti-HER2/neu antibody (Figures 2D and 2E). Twenty-one hours after the end of overnight incubation with 212Pb-TCMC-7.16.4 activity concentrations ranging from 0.185 to 2.78 kBq/ml, the cell number starts at approximately 86 to 90 % of the control value (Figures 2A and 2B). By 5 days, this range of activity concentrations yields cell numbers that are 74 % (for 2.78 kBq/ml) to 84 % (for 0.185 kBq/ml) of control. At activity concentrations of 3.70 and 7.40 kBq/ml, the cell number drops to approximately 50 % of control by day 5. At 3.70 kBq/ml the drop becomes apparent after the 3rd day and decreases more gradually over the next two days. Cells exposed to 7.40 kBq/ml exhibit reduced proliferative capacity from 24 to 48 hours so that the cell level at 48 h is already at 50 % of control. As shown on Figure 2C, these effects occur only when the cells are specifically targeted. The effect of untargeted radiation combined with high concentration of anti-HER2/neu antibody is reflected in the approximately 20 % reduction in cell number after 5-days of growth across all activity concentrations examined.

Figures 2:

Proliferation of NT2.5 tumor cells. (A) Absorbance, (B) relative to the non-treated controls’ absorbance of the cells and (C) absorbance post overnight incubation with 10μg/ml unlabeled antibody, as a function of incubation time for different 212Pb-conjugated anti-HER2/neu antibody activity concentrations (0-7.40 kBq/ml). (D-E) % Proliferating fraction of NT2.5 tumor cells after 5 days of incubation (D) without blocking and (E) with blocking using 10 μg/ml of cold Ab, as a function of activity concentration (0-7.40 kBq/ml); no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) across the different activity concentrations and untreated cells was observed. At least three replications for each condition were used and the values represent the mean ± standard deviation.

Figures 2D and 2E show the quantitative results of the WST-8 cell proliferation assay performed after 5 days of incubation with increasing amount (0-7.40 kBq/ml) of labeled Ab, for blocked and non-blocked cells. A statistically significant decrease in proliferative capacity is observed for all doses in Figure 2D, with the lowest proliferating fraction noted for the highest dose-group and being equal to 46.1 % compared to the control (p ≤ 0.001). Blocking with 10 μg/ml of cold (unlabeled) antibody eliminated the dose-response relationship at day 5 (p > 0.05) (Figure 2E).

In vitro Colony Formation Assay

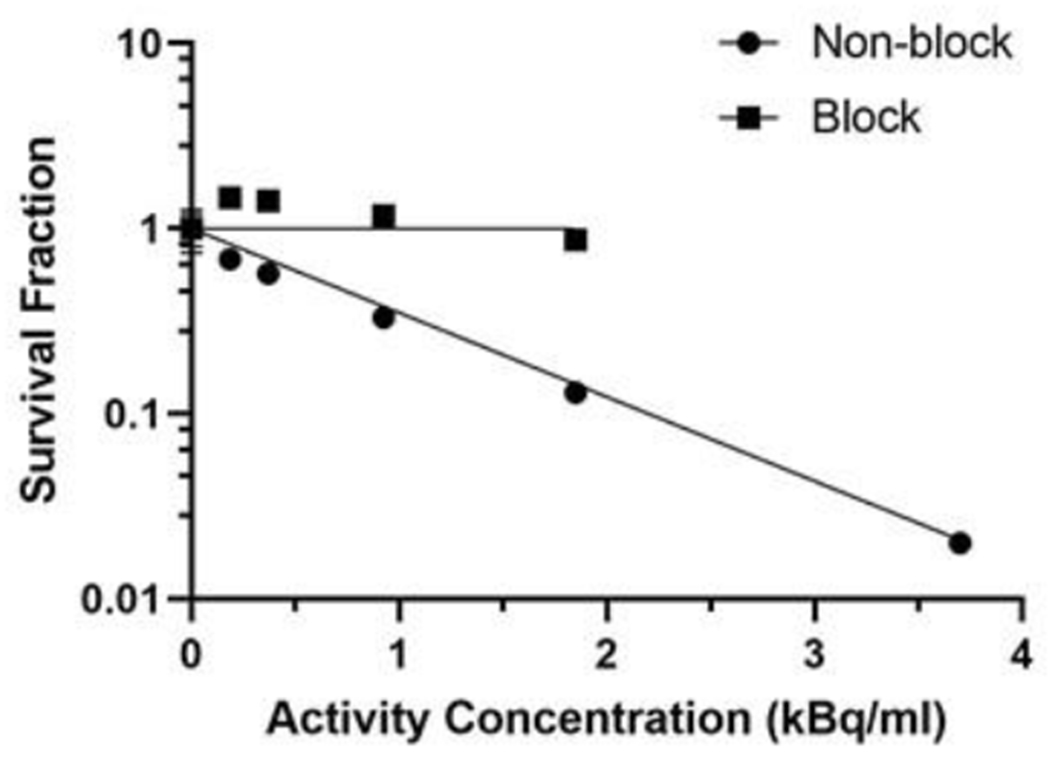

The colony formation assay provides a readout on the ability of irradiated cells to form colonies. Figure 3 shows colony formation results for cells incubated overnight with different activity concentrations. Specificity of the results was evaluated by CFA of cells exposed to a 5-h incubation of 10 μg/ml unlabeled antibody prior to the overnight radiolabeled antibody incubations. At the highest activity concentration (3.70 kBq/ml) the number of colonies were too high to yield an accurate count. The activity concentration of labeled construct required to reduce colony formation to 50 %, was 0.662 kBq/ml; obtained by monoexponential curve fitting (κ = 1.047±0.165 (kBq/ml)−1, R2 = 0.95) (Barendsen et al. 1960).

Figure 3:

Colony formation assay showing the effect of high LET radiation treatment, 212Pb-TCMC-7.16.4 (0-3.70 kBq/ml), on the survival of NT2.5 tumor cells. The experiments were carried out in 6 replicates and the values represent the mean ± standard deviation. Error bars for all points on the plot except first are less than 9%.

In vitro RBE determination

The S-values for each compartment, as estimated with the GEANT Monte Carlo simulations are shown in Table 1. A direct validation with a similar sized MIRDcell model is given in the supplemental Tables 1S and 2S. The resulting absorbed dose vs survival curve is shown in Figure 4. A monoexponential function was fitted through the absorbed dose-survival data (κ = 2.784±0.041 Gy−1; R2 = 0.94). Figure 4 also shows CFA data from external beam (Yu, Lu, Jessie R Nedrow, et al. 2020). The reference data were fitted to a linear-quadratic function (α = 0.169±0.025 Gy−1; β = 0.056±0.003 Gy−2; R2 = 0.99) and were also transformed to a log-linear relationship using the EQD2 formalism (Bentzen et al. 2012; Hobbs et al. 2014). Using these two data sets, RBE2 was calculated as 9.9. The RBE at 10, 37 and 50 % surviving fraction was 6.1, 8.3 and 9.3, respectively.

Table 1:

S-values for each compartment. The alpha particles and combined beta and gamma contributions specified separately.

| Alpha particles (Gy/Bq) | Beta and gamma contributions (Gy/Bq) | |

|---|---|---|

| Medium dose | 9.25E-10 | 4.82E-11 |

| Cross dose | ||

| Cell surface | 9.71E-5 | 1.20E-6 |

| Cytosol | 9.76E-5 | 1.2E-6 |

| Self dose | ||

| Cell surface | 1.20E-2 | 2.86E-4 |

| Cytosol | 2.27E-2 | 5.96E-4 |

Figure 4:

Absorbed dose-survival curves for current 212Pb-labeled antibody studies (blue line), reference (0.08 Gy/min) XRT (green curve) and linear-dose response to equivalent 2 Gy per fraction XRT dosing (red line). RBE2(α/β) is the ratio of κ / (α + 2β).

Discussion

Alpha-particle emitters are of increasing interest as cancer therapeutics. Lead-212, a beta-particle emitter, has been developed as a targeted “generator” to deliver alpha-particles originating from the decay of 212Bi. Lead-212 radioconjugates have been used in patients to target HER2/neu expressing peritoneal metastases and, more recently, to target somatostatin receptor positive tumors (R.F. Meredith et al. 2014b; R. Meredith et al. 2014; Stallons et al. 2019; Delpassand et al. 2019). Preclinical studies using 212Pb conjugates have investigated targeting multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, brain cancer metastases and metastatic prostate cancer (Banerjee et al. 2020; Maaland et al. 2020; Quelven et al. 2020).

The dense (i.e., high) linear energy transfer (LET) deposition pattern of alpha-particle tracks results in a greater biologic effect per unit absorbed dose than low LET radiation. This relative biological efficacy (RBE) is typically measured by comparing clonogenic survival of cells irradiated by the α-emitter relative to a low LET radiation, such as external beam photons.

The increased interest in clinical and preclinical use of 212Pb for cancer therapy makes RBE measurements important in understanding absorbed dose vs response results. The few RBE measurements for 212Pb used either unconjugated 212Pb or 212Pb localized in the cell nucleus or injected into mouse testes (Rotmensch et al. 1989; Azure et al. 1994; Howell et al. 1994). Using unconjugated 212Pb, Rotmensch et al. (1989), reported RBE values of 2.07 and 4.43 for ovarian carcinoma cell lines OVC-1 and OVC-2, respectively; corresponding radiosensitivity values (κ = 1/D0) were 1.33 and 1.43 Gy−1. They also examined the RBE of 212Bi and found values of 1.83 and 2.53 for the same cell lines with corresponding radiosensitivities of 1.18 and 1.05 Gy−1. The reference low LET radiation used in these studies was delivered over 18 hours with 250 kVp x-rays at a dose rate of 0.08 Gy/min.

The studies by Azure et al. (1994), yielded an RBE of 4 for 37% survival of Chinese hamster lung fibroblast, V79 cells; 137Cs gamma (662 keV) rays were used as the low LET reference radiation. A radiosensitivity of 1 Gy−1 was reported. The same group measured an RBE of 4.7 in mouse testes, using 37% testicular spermhead survival as the biologic endpoint (Azure et al. 1994).

In the present study the clonogenic and proliferation growth capacities of NT2.5 mouse mammary carcinoma tumor cells have been evaluated following incubation with 212Pb-labeled antibody that targets the rat version of the HER2/neu receptor expressed on these cells. An irradiator delivering 225 kVp x-rays at a dose rate of 1.24 Gy/min was used for the low LET colony formation assays. Since the low-LET curve is not log-linear, values at commonly used surviving fractions have been calculated to enable comparison with prior studies. The RBE at 10, 37 and 50 % surviving fraction was 6.1, 8.3 and 9.3, respectively. The RBE at 37 % survival is typically reported, accordingly the 8.3 RBE is comparable to the RBE values reported above. The difference in RBE herein reported compared to the other studies is most likely due to differences in the distribution of decays relative to cellular geometry and also potentially to differential cellular radiosensitivity to the low LET radiation. Our cell model consists of perfectly concentric cells, which is an obvious simplification of adherent cell monolayers, which can exhibit some variability in volume between cells and non-spherical geometries (Tamborino et al. 2020). This is, however, a simplification which is commonly used for modelling, including for the MIRD reference MIRDcell. We have validated our Monte Carlo simulations by direct comparison to MIRDcell, which resulted in a maximum difference of about 2 %. Future work will have to elucidate the effect of more realistic geometries on absorbed dose estimations. Furthermore, since the mechanism and impact of bystander effects is still under investigation (Boyd et al. 2006; Prise & O’Sullivan 2009; Ladjohounlou et al. 2019; Bellia et al. 2019) and no formalism for evaluating RBE that incorporates bystander effects has been described, we have opted to measure RBE as it has traditionally been evaluated – i.e., without consideration of bystander effects. This allows us to make comparisons with other RBE reports.

The low LET radiation in our studies is characterized by the linear-quadratic function parameters, α = 0.169±0.025 Gy−1; β = 0.056±0.003 Gy−2 giving α/β = 3.02 Gy, a value that is more characteristic of late responding normal tissues. Data that has emerged from hypofraction studies is suggesting that the alpha-beta ratio for breast cancer is much closer to values associated with normal tissues (Group et al. 2008; Freedman et al. 2013). The log-linear curve obtained for cells incubated with 212Pb conjugated targeting antibody gave a radiosensitivity of 2.784 Gy−1. This much greater radiosensitivity is consistent with the higher RBE value obtained.

According to Thomas et al. (2007), some cell lines are remarkably radioresistant to low-LET giving an RBE of 14 for bovine aortic endothelial cells, conversely, a porcine cell line was characterized by hypersensitivity to low-LET and yielded a much lower RBE value of 1.6 (Thomas et al. 2007). This could be attributed to cell physiology changes affecting survival post-treatment in different species, more than that of direct DNA damage. Other RBE values derived from in vitro studies according to literature reports, ranged between 3-5 (Feinendegen & McClure 1997).

Using a previously published formalism that “linearizes” the linear-quadratic dose response relationship for low LET radiation by expressing the dose delivered into the response expected by delivering the total dose as 2-Gy per fraction equivalents (EQD2) (Hobbs et al. 2014), an RBE value of 9.9 is obtained. This RBE2 value is independent of the survival fraction chosen at which the RBE is calculated. To reduce confusion as to which value is cited, the RBE2 is recommended for future reporting of RBE evaluations.

Yard et al. (2019), recently reported the median RBE at 37 % survival for a large number of tumor cell lines, following exposure to 223Ra, as 9.7. The alpha-particle energies emitted by 223Ra and its daughters include lower energy 5.6 to 5.7 MeV alphas, these are emitted at higher initial LETs than the higher energy 6 and 8.8 MeV alphas emitted by 212Bi (Sgouros et al. 2010). The LET along the particle track determines the complexity of DNA double strand breaks and correspondingly the RBE. In addition, differences in the decay distribution relative to the cellular geometry could contribute to the higher RBE of 223Ra; unlike antibody-conjugated 212Pb, 223Ra is not localized on the cell surface or intracellularly. Ballangrud et al. (2004), reported radiosensitivity (absorbed dose for 37 % survival) values for both low and high LET radiation (Cs-137 and 225Ac-conjugated antibody), respectively for three breast cancer cell lines, MCF7, MDA-MB-231 and BT-474. To obtain radiosensitivity to high LET radiation of the three cell lines that would not be influenced by binding to HER2/neu sites a non-specific antibody was used. The RBE values calculated from the data provided in this study are 2.8, 2.6 and 4.7 for MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and BT-474, respectively (Ballangrud et al. 2004).

In our similar experimental conditions, with excess amount of unlabeled antibody, no significant absorbed dose-dependent reduction in clonogens or cellular proliferation was observed. In the presence of high concentration of the unlabeled anti-HER2/neu antibody an approximately 20 % reduction in cell number was observed across all activity concentrations during the proliferation assay, which is consistent with the anticipated effects of HER2/neu-targeting antibodies (Park et al. 2010; Wulbrand et al. 2013). Furthermore, as reported in Table 1, the dose contribution of the unbound labeled antibodies (i.e. media contribution) to the absorbed dose, relative to the bound and internalized fraction, is orders of magnitude smaller. The lower activity concentrations used here, combined with the shorter half-life of 212Pb relative to 225Ac, result in absorbed dose contributions of the media which are at least 57 times lower than what is reported by Ballangrud, et al.

This is relevant regarding normal tissue toxicity and shows that, in the studied range of activity concentrations, untargeted αRPT yields minimal alpha-particle radiation to cells, which is consistent with the experimental observations. The short range of alpha-particles and the rapid decrease in solid angle as the decay occurs in the incubation medium (or extracellularly) likely explain the negligible toxicity of untargeted 212Pb. These results imply a target to normal organ absorbed dose advantage that could be an order of magnitude greater than would be predicted by the average absorbed dose.

Conclusion

Antibody-conjugated 212Pb targeting cell-surface HER2/neu receptors on a murine mammary carcinoma cell line yielded an RBE of 8.3 at 37 % survival and a survival independent RBE (i.e., RBE2) of 9.9. Unbound 212Pb-labeled antibody, as obtained in blocking experiments yielded negligible radiation induced cell kill. These results re-enforce the importance of specific targeting to achieve tumor cell kill and the potential low toxicity of αRPT for non-reactive tissues.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant: R01 CA116477.

Biographies

Dr. Ioanna Liatsou is a Research Associate at the Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine, Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, and is a member of the Sgouros RTD Lab. Dr. Liatsou received her Bachelor of Science in Chemistry and her Master of Science and Ph.D. in Radioanalytical Chemistry with honors, from the University of Cyprus. She is a radiochemist with a wide range of expertise in radioanalytical chemistry and radiopharmaceutical therapy and her work is currently focused on targeted cancer therapy with the use of alpha particle emitter radiopharmaceuticals (αRPTs).

Dr. Jing Yu was a postdoc research fellow at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, and is now a Scientist at Johnson & Johnson. She received her bachelor degree in Chemical and Pharmaceutical Engineering at Southeast University, China. Dr. Yu earned her master degree in Pharmaceutical Science at Kanazawa University from Japan and Ph.D. degree in Chemistry from Kansas State University. Her research focused on cancer diagnosis and treatment with peptides and antibodies labelled with radio isotopes or fluorescence.

Dr. Remco Bastiaannet is a Research Associate at the Radiological Physics Department in the Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Science at Johns Hopkins Medicine. Dr. Bastiaannet received his Master of Science in Biomedical Engineering from the University of Twente and his PhD in the Medical Physics of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine from the University of Utrecht, The Netherlands. Dr. Bastiaannet’s research interests center on the quantification of radiation absorbed dose and dose-effect relationships in vivo, in vitro and in silico.

Dr. Zhi Li is a senior research specialist at the Radiopharmaceutical Therapy and Dosimetry (RTD) Lab, Department of Radiology, Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Li received his PhD in Shanghai Brain Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences in 2001. He joined the Department of Neuroscience at Hopkins as a postdoc in 2002 and was a research associate in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery before joining the RTD Lab.

Dr. Robert Hobbs is an Associate Professor and has been a member of the Department of Radiology at Johns Hopkins since 2006. Dr. Hobbs’ primary appointment is in the department of Radiation Oncology, where he works in the clinic as an ABR certified Medical Physicist. Dr. Hobbs earned his undergraduate degrees (DEUG, Licence, Maîtrise) in Physics from the Université Louis Pasteur in Strasbourg, France, with a year spent at the Universität Wien (Vienna, Austria) as an ERASMUS exchange student. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of New Mexico in high energy Physics before joining the Sgouros lab as a post-doc in 2006. In 2011, he joined the department of Radiation Oncology as a Medical Physics resident. He received his ABR certification in 2014. Dr. Hobbs has been elected member of the MIRD (Medical Internal Radiation Dose) Committee and ais chair of the AAPM radiopharmaceutical therapy sub-committee (RPTSC).

Dr. Julien Torgue graduated from Florida Institute of Technology with a B.S. in Biochemistry, 2003, and a Ph.D. in molecular Biology, 2007. Dr. Torgue was elected member of the Macrocyclics board of directors in July 2015 and has been the Chief Scientific Officer at Orano Med, since 2010.

Dr. George Sgouros is a Professor in the Johns Hopkins Medicine Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, Department of Radiation Oncology and Department of Oncology and a member of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center. His research focuses on modelling and dosimetry of internally administered radionuclides with a particular emphasis on patient-specific dosimetry, alpha-particle dosimetry, and mathematical modelling of radionuclide therapy. Dr. Sgouros is Director of the Radiological Physics Division of the Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Science. Dr. Sgouros received his undergraduate degree in applied physics from Columbia University. He earned his Ph.D. from Cornell University and performed a fellowship in medical physics at Sloan Kettering Institute, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York. Dr. Sgouros joined the Johns Hopkins faculty in 2003.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts or competing interests to disclose.

References

- Allison J, Amako K, Apostolakis J, Arce P, Asai M, Aso T, Bagli E, Bagulya A, Banerjee S, Barrand G, et al. 2016. Recent developments in Geant4. Nucl Instruments Methods Phys Res Sect A Accel Spectrometers, Detect Assoc Equip [Internet]. 835:186–225. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168900216306957 [Google Scholar]

- Azure MT, Archer RD, Sastry KSR, Rao DV, Howell RW. 1994. Biological effect of lead-212 localized in the nucleus of mammalian cells: Role of recoil energy in the radiotoxicity of internal alpha-particle emitters. Radiat Res. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baidoo KE, Milenic DE, Brechbiel MW. 2013. Methodology for labeling proteins and peptides with lead-212 (212Pb). Nucl Med Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballangrud ÅM, Yang W-H, Palm S, Enmon R, Borchardt PE, Pellegrini VA, McDevitt MR, Scheinberg DA, Sgouros G. 2004. Alpha-Particle Emitting Atomic Generator (Actinium-225)-Labeled Trastuzumab (Herceptin) Targeting of Breast Cancer Spheroids. Clin Cancer Res [Internet]. 10(13):4489 LP–4497.http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/10/13/4489.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee SR, Minn I, Kumar V, Josefsson A, Lisok A, Brummet M, Chen J, Kiess AP, Baidoo K, Brayton C, et al. 2020. Preclinical evaluation of 203/212Pb-labeled low-molecular-weight compounds for targeted radiopharmaceutical therapy of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barendsen GW, Beusker TL. 1960. Effects of different ionizing radiations on human cells in tissue culture. I. Irradiation techniques and dosimetry. Radiat Res. 13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barendsen GW, Beusker TL, Vergroesen AJ, BUDKE L. 1960. Effects of different radiations on human cells in tissue culture. II. Biological experiments. Radiat Res. 13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellia SR, Feliciani G, Duca M Del, Monti M, Turri V, Sarnelli A, Romeo A, Kelson I, Keisari Y, Popovtzer A, et al. 2019. Clinical evidence of abscopal effect in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treated with diffusing alpha emitters radiation therapy: a case report. J Contemp Brachytherapy [Internet]. 11(5):449–457. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31749854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen SM, Dörr W, Gahbauer R, Howell RW, Joiner MC, Jones B, Jones DTL, Van Der Kogel AJ, Wambersie A, Whitmore G. 2012. Bioeffect modeling and equieffective dose concepts in radiation oncology-Terminology, quantities and units. Radiother Oncol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd M, Ross SC, Dorrens J, Fullerton NE, Tan KW, Zalutsky MR, Mairs RJ. 2006. Radiation-Induced Biologic Bystander Effect Elicited In Vitro by Targeted Radiopharmaceuticals Labeled with α-, β-, and Auger Electron–Emitting Radionuclides. J Nucl Med [Internet]. 47(6):1007 LP–1015. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/47/6/1007.abstract [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpassand E, Tworowska I, Shanoon F, Nunez R, Flores L II, Muzammil A, Stallons T, SAIDI A, Torgue J. 2019. First clinical experience using targeted alpha-emitter therapy with <sup>212</sup>Pb-DOTAMTATE (AlphaMedix <sup>TM</sup>) in patients with SSTR(+) neuroendocrine tumors. J Nucl Med [Internet]. 60(supplement 1):559 LP–559. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/60/supplement_1/559.abstract [Google Scholar]

- Denoël T, Pedrelli L, Pantaleo G, Prior JO. 2019. A robust method for assaying the immunoreactive fraction in nonequilibrium systems. Pharmaceuticals. 12(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles LJ, O’Neill P, Lomax ME. 2011. Delayed repair of radiation induced clustered DNA damage: friend or foe? Mutat Res [Internet]. 711(1–2):134–141. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21130102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgqvist J, Frost S, Pouget J-P, Albertsson P. 2014. The potential and hurdles of targeted alpha therapy - clinical trials and beyond. Front Oncol [Internet]. 3:324. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24459634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinendegen LE, McClure JJ. 1997. Alpha-emitters for medical therapy - Workshop of the United States Department of Energy. Denver, Colorado, May 30-31, 1996. In: Radiat Res. [place unknown]. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman GM, White JR, Arthur DW, Allen Li X, Vicini FA. 2013. Accelerated fractionation with a concurrent boost for early stage breast cancer. Radiother Oncol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group ST, Bentzen SM, Agrawal RK, Aird EGA, Barrett JM, Barrett-Lee PJ, Bentzen SM, Bliss JM, Brown J, Dewar JA, et al. 2008. The UK Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy (START) Trial B of radiotherapy hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet (London, England) [Internet]. 371(9618):1098–1107. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18355913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson-Lutz A, Bäck T, Aneheim E, Hultbom R, Palm S, Jacobsson L, Morgenstern A, Bruchertseifer F, Albertsson P, Lindegren S. 2017. Therapeutic efficacy of α-radioimmunotherapy with different activity levels of the 213Bi-labeled monoclonal antibody MX35 in an ovarian cancer model. EJNMMI Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs RF, Howell RW, Song H, Baechler S, Sgouros G. 2014. Redefining Relative Biological Effectiveness in the Context of the EQDX Formalism: Implications for Alpha-Particle Emitter Therapy. Radiat Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell RW, Azure MT, Narra VR, Rao DV. 1994. Relative biological effectiveness of alpha-particle emitters in vivo at low doses. Radiat Res. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimian A, Ji NT, Song H, Sgouros G. 2020. Mathematical modeling of preclinical alpha-emitter radiopharmaceutical therapy. Cancer Res. 80(4):868–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasten BB, Oliver PG, Kim H, Fan J, Ferrone S, Zinn KR, Buchsbaum DJ. 2018. (212)Pb-Labeled Antibody 225.28 Targeted to Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan 4 for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Therapy in Mouse Models. Int J Mol Sci [Internet]. 19(4):925. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29561763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladjohounlou R, Lozza C, Pichard A, Constanzo J, Karam J, Le Fur P, Deshayes E, Boudousq V, Paillas S, Busson M, et al. 2019. Drugs That Modify Cholesterol Metabolism Alter the p38/JNK-Mediated Targeted and Nontargeted Response to Alpha and Auger Radioimmunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res [Internet]. 25(15):4775 LP–4790. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/25/15/4775.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maaland AF, Saidi A, Torgue J, Heyerdahl H, Rozgaja Stallons TA, Kolstad A, Dahle J. 2020. Targeted alpha therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with the anti-CD37 radioimmunoconjugate 212Pb-NNV003. PLoS One. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith R, Torgue J, Shen S, Fisher DR, Banaga E, Bunch P, Morgan D, Fan J, Straughn JM Jr. 2014. Dose escalation and dosimetry of first-in-human α radioimmunotherapy with 212Pb-TCMC-trastuzumab. J Nucl Med [Internet]. 55(10):1636–1642. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25157044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith RF, Torgue J, Azure MT, Shen S, Saddekni S, Banaga E, Carlise R, Bunch P, Yoder D, Alvarez R. 2014a. Pharmacokinetics and imaging of 212Pb-TCMC-trastuzumab after intraperitoneal administration in ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith RF, Torgue J, Azure MT, Shen S, Saddekni S, Banaga E, Carlise R, Bunch P, Yoder D, Alvarez R. 2014b. Pharmacokinetics and Imaging of 212 Pb-TCMC-Trastuzumab After Intraperitoneal Administration in Ovarian Cancer Patients .Cancer Biother Radiopharm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenic DE, Molinolo AA, Solivella MS, Banaga E, Torgue J, Besnainou S, Brechbiel MW, Baidoo KE. 2015. Toxicological Studies of 212Pb Intravenously or Intraperitoneally Injected into Mice for a Phase 1 Trial. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) [Internet]. 8(3):416–434. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26213947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitaki Z, Nikolov V, Mavragani IV, Mladenov E, Mangelis A, Laskaratou DA, Fragkoulis GI, Hellweg CE, Martin OA, Emfietzoglou D, et al. 2016. Measurement of complex DNA damage induction and repair in human cellular systems after exposure to ionizing radiations of varying linear energy transfer (LET). Free Radic Res [Internet]. 50(sup1):S64–S78. 10.1080/10715762.2016.1232484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SG, Jiang Z, Mortenson ED, Deng L, Radkevich-Brown O, Yang X, Sattar H, Wang Y, Brown NK, Greene M, et al. 2010. The therapeutic effect of anti-HER2/neu antibody depends on both innate and adaptive immunity. Cancer Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prise KM, O’Sullivan JM. 2009. Radiation-induced bystander signalling in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer [Internet]. 9(5):351–360. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19377507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quelven I, Monteil J, Sage M, Saidi A, Mounier J, Bayout A, Garrier J, Cogne M, Durand-Panteix S. 2020. 212Pb α-radioimmunotherapy targeting CD38 in multiple myeloma: A preclinical study. J Nucl Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly RT, Gottlieb MBC, Ercolini AM, Machiels JPH, Kane CE, Okoye FI, Muller WJ, Dixon KH, Jaffee EM. 2000. HER-2/neu is a tumor rejection target in tolerized HER-2/neu transgenic mice. Cancer Res. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly RT, Machiels JPH, Emens LA, Ercolini AM, Okoye FI, Lei RY, Weintraub D, Jaffee EM. 2001. The collaboration of both humoral and cellular HER-2/neu-targeted immune responses is required for the complete eradication of HER-2/neu-expressing tumors. Cancer Res. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotmensch J, Atcher RW, Hines J, Grdina D, Schwartz JS, Toohill M, Herbst AL. 1989. The development of α-emitting radionuclide lead 212 for the potential treatment of ovarian carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider NR, Lobaugh M, Tan Z, Sandwall P, Chen P, Glover SE, Cui L, Murry M, Dong Z, Torgue J, Spitz HB. 2013. Biodistribution of 212Pb conjugated trastuzumab in mice. In: J Radioanal Nucl Chem. [place unknown] [Google Scholar]

- Sgouros G, Bodei L, McDevitt MR, Nedrow JR. 2020. Radiopharmaceutical therapy in cancer: clinical advances and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgouros G, Roeske JC, McDevitt MR, Palm S, Allen BJ, Fisher DR, Brill AB, Song H, Howell RW, Akabani G, et al. 2010. MIRD Pamphlet No. 22 (abridged): radiobiology and dosimetry of alpha-particle emitters for targeted radionuclide therapy. J Nucl Med [Internet]. 51(2):311–328. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20080889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Shahverdi K, Huso DL, Wang Y, Fox JJ, Hobbs RF, Gimi B, Gabrielson KL, Pomper MG, Tsui BM, et al. 2008. An immunotolerant HER-2/neu transgenic mouse model of metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallons TAR, Saidi A, Tworowska I, Delpassand ES, Torgue JJ. 2019. Preclinical investigation of 212Pb-DOTAMTATE for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in a neuroendocrine tumor model. Mol Cancer Ther. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamborino G, De Saint-Hubert M, Struelens L, Seoane DC, Ruigrok EAM, Aerts A, van Cappellen WA, de Jong M, Konijnenberg MW, Nonnekens J. 2020. Cellular dosimetry of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-[Tyr3]octreotate radionuclide therapy: the impact of modeling assumptions on the correlation with in vitro cytotoxicity. EJNMMI Phys [Internet]. 7(1):8. 10.1186/s40658-020-0276-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Tracy B, Ping T, Baweja A, Wickstrom M, Sidhu N, Hiebert L. 2007. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of alpha radiation in cultured porcine aortic endothelial cells. Int J Radiat Biol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp-Greenwood FL, Coogan MP. 2011. Towards translation of 212Pb as a clinical therapeutic; getting the lead in! Dalt Trans. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri B, Wu H, Dhawan AP, Du P, Howell RW. 2014. MIRD Pamphlet No. 25: MIRDcell V2.0 Software Tool for Dosimetric Analysis of Biologic Response of Multicellular Populations. J Nucl Med [Internet]. 55(9):1557 LP–1564. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/55/9/1557.abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westrøm S, Generalov R, Bønsdorff TB, Larsen RH. 2017. Preparation of 212Pb-labeled monoclonal antibody using a novel 224Ra-based generator solution. Nucl Med Biol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulbrand C, Seidl C, Gaertner FC, Bruchertseifer F, Morgenstern A, Essler M, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R. 2013. Alpha-Particle Emitting 213Bi-Anti-EGFR Immunoconjugates Eradicate Tumor Cells Independent of Oxygenation. PLoS One. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yard BD, Gopal P, Bannik K, Siemeister G, Hagemann UB, Abazeed ME. 2019. Cellular and genetic determinants of the sensitivity of cancer to α-particle irradiation. Cancer Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong K, Brechbiel M. 2015. Application of (212)Pb for Targeted α-particle Therapy (TAT): Pre-clinical and Mechanistic Understanding through to Clinical Translation. AIMS Med Sci [Internet]. 2(3):228–245. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26858987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Lu R, Nedrow Jessie R, Sgouros G. 2020. Response of breast cancer carcinoma spheroids to combination therapy with radiation and DNA-PK inhibitor: growth arrest without a change in α/β ratio. Int J Radiat Biol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Lu R, Nedrow Jessie R, Sgouros G. 2020. Response of breast cancer carcinoma spheroids to combination therapy with radiation and DNA-PK inhibitor: Growth arrest without a change in α/β ratio. Int J Radiat Biol [Internet].:1–23. 10.1080/09553002.2020.1838659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.