Abstract

Background

Cardiac complications related to COVID‐19 in children and adolescents include ventricular dysfunction, myocarditis, coronary artery aneurysm, and bradyarrhythmias, but tachyarrhythmias are less understood. The goal of this study was to evaluate the frequency, characteristics, and outcomes of children and adolescents experiencing tachyarrhythmias while hospitalized for acute severe COVID‐19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

Methods and Results

This study involved a case series of 63 patients with tachyarrhythmias reported in a public health surveillance registry of patients aged <21 years hospitalized from March 15, 2020, to December 31, 2021, at 63 US hospitals. Patients with tachyarrhythmias were compared with patients with severe COVID‐19–related complications without tachyarrhythmias. Tachyarrhythmias were reported in 22 of 1257 patients (1.8%) with acute COVID‐19 and 41 of 2343 (1.7%) patients with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. They included supraventricular tachycardia in 28 (44%), accelerated junctional rhythm in 9 (14%), and ventricular tachycardia in 38 (60%); >1 type was reported in 12 (19%). Registry patients with versus without tachyarrhythmia were older (median age, 15.4 [range, 10.4–17.4] versus 10.0 [range, 5.4–14.8] years) and had higher illness severity on hospital admission. Intervention for treatment of tachyarrhythmia was required in 37 (59%) patients and included antiarrhythmic medication (n=31, 49%), electrical cardioversion (n=11, 17%), cardiopulmonary resuscitation (n=8, 13%), and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (n=9, 14%). Patients with tachyarrhythmias had longer hospital length of stay than those who did not, and 9 (14%) versus 77 (2%) died.

Conclusions

Tachyarrhythmias were a rare complication of acute severe COVID‐19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents and were associated with worse clinical outcomes, highlighting the importance of close monitoring, aggressive treatment, and postdischarge care.

Keywords: COVID‐19, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C), tachyarrhythmia

Subject Categories: Arrhythmias

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- MIS‐C

multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children

- OC‐19

Overcoming COVID‐19

- SVT

supraventricular tachycardia

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Tachyarrhythmias were rare (1.8%) in a cohort of 3600 children and adolescents with severe acute COVID‐19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children from the OC‐19 (Overcoming COVID‐19) public health registry.

Tachyarrhythmias occurred most frequently in older and sicker patients with cardiac and multisystem involvement and were associated with prolonged hospital length of stay and higher in‐hospital mortality.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Longer‐term surveillance after hospital discharge will be important to better understand the arrhythmic and other cardiac risks after acute COVID‐19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children complicated by tachyarrhythmia.

Children with COVID‐19 are more likely to have asymptomatic or mild disease as compared with adults 1 , 2 , 3 but are still at risk of critical illness. 4 Manifestations of cardiovascular involvement include elevated BNP (B‐type natriuretic peptide), elevated troponin level, ventricular dysfunction, coronary artery aneurysms, pericardial effusion, and arrhythmias. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Only limited data are available on arrhythmias in children following COVID‐19 infection. 5 , 8 Using sentinel surveillance data from the OC‐19 (Overcoming COVID‐19) network, we sought to characterize tachyarrhythmias, including interventions and outcomes in inpatients aged <21 years with acute severe COVID‐19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C).

Methods

Design and Participants

Eligibility criteria and methods for the OC‐19 public health surveillance registry have previously been published. 5 , 6 Patients aged <21 years old hospitalized with SARS‐CoV‐2–related illness admitted to the hospital from March 15, 2020, to December 31, 2021, were screened. Eligible patients had acute severe COVID‐19 (admitted to the intensive care unit or stepdown unit) or MIS‐C (Data S1). 5 , 6 The OC‐19 registry was approved by the central institutional review board at Boston Children's Hospital and granted a waiver of consent. It was reviewed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention policy (45 C.F.R. part 46.102(l)(2); 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq). The authors declare that all data are available in the article and online supplementary material.

Tachyarrhythmia Case Ascertainment and Definitions

Cases were identified on the basis of a report of a tachyarrhythmia during hospital admission documented in the medical record. Tachyarrhythmia was defined as a report of an atrial, junctional, or ventricular arrhythmia meeting prespecified definitions. Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) was defined as narrow or usual complex tachycardia >3 beats with ≥1:1 atrial‐ventricular association, and further classified as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, ectopic atrial tachycardia, or reentrant SVT. Accelerated junctional rhythm was defined as narrow or usual complex tachycardia with ≥1:1 ventricular‐atrial association and rates >100 bpm. Ventricular tachycardia was defined as wide complex tachycardia, and further classified as nonsustained (≥3 consecutive ventricular beats, rate>120 bpm and <30 seconds duration), sustained (>30 seconds or requiring intervention for termination), and ventricular fibrillation.

For cases with a reported arrhythmia, an additional case report form (Data S1) was sent to each center's principal investigator to confirm the diagnosis and collect additional information on the course of arrhythmia and treatments required. Deidentified ECGs were reviewed and classified by consensus of 3 pediatric cardiologists (A.D., K.F., J.N.) when available for review. There was consensus from all 3 reviewers for all cases, and 2 patients were reclassified after central review of ECG tracings.

Cardiac involvement was defined as serum BNP or NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide) ≥1000 pg/mL, elevated troponin based on the upper limit of normal for the site laboratory, left ventricular ejection fraction <55%, or coronary artery aneurysm. 5 If no test was performed, it was considered normal. Left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) was categorized as normal if EF was ≥55%, mild–moderate ventricular dysfunction if EF was 35 to <55%, and severe ventricular dysfunction if EF was <35%; in cases where EF was unavailable, qualitative assessment of ventricular function was used. Coronary artery aneurysm was defined as proximal right coronary artery or left anterior descending coronary z score ≥2.5. 10 When >1 echocardiogram was available, patients were classified on the basis of their worst‐ever EF and highest coronary artery z score during the illness. 11 The Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score is a continuous score between 0 and 24, including respiratory, coagulation, hepatic, cardiovascular, neurologic, and renal organ assessment.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained for clinical characteristics, tachyarrhythmias, and outcomes. Quantitative variables were summarized as median (Quartile 1 [Q1], Quartile 3 [Q3]), and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Patients with and without tachyarrhythmias were compared using the chi‐squared test, Fisher exact test, or Mann–Whitney test where appropriate. A 2‐tailed P value <0.05 was deemed statistically significant. All analyses were performed with R software version 4.0.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics Among All Patients

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 3600 surveillance registry patients meeting inclusion criteria: 2097 (58%) male; median age, [10.1 Q1, Q3: 5.4, 14.8] years, including 1257 (35%) with severe acute COVID‐19 infection and 2343 (65%) with MIS‐C.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Aged <21 Years With and Without Tachyarrhythmias Hospitalized With COVID‐19 or MIS‐C in 63 US Hospitals Participating in the “Overcoming COVID‐19” Public Health Registry, March 15, 2020, to December 31, 2021

| Tachyarrhythmia (n=63) | No tachyarrhythmia (n=3537) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (Q1, Q3) | 15.4 (10.4, 17.4) | 10.0 (5.3, 14.7) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 39 (62) | 2058 (58) | 0.64 |

| Met criteria for MIS‐C | 41 (65) | 2302 (65) | 1.00 |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| White, non‐Hispanic | 16 (25) | 1120 (32) | 0.07 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 29 (46) | 1037 (29) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 14 (22) | 935 (26) | |

| Other, non‐Hispanic | 3 (5) | 215 (6) | |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 230 (7) | |

| Underlying conditions | |||

| At least 1 underlying condition | 36 (57) | 1658 (47) | 0.14 |

| Cardiovascular | 6 (10) | 137 (4) | 0.05 |

| Obesity | 35/60 (58) | 1124/3132 (36) | <0.001 |

| Presentation conditions | |||

| Organ systems involved, median (Q1, Q3) | 5 (4, 6) | 4 (3, 5) | <0.001 |

| Duration of symptoms prehospitalization, median (Q1,Q3) | 4 (3, 5.75) | 4 (3, 6) | 0.88 |

| Initial laboratory values (within 48 h) | |||

| Neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio, median (Q1,Q3)* | 9.00 (4.87, 16.74) | 5.96 (3.00, 101.17) | 0.003 |

| ALT (U/L), median (Q1, Q3)† | 48.0 (22.0, 91.0) | 32.0 (19.0, 58.0) | 0.02 |

| CRP (mg/dL), median (Q1, Q3)‡ | 14.9 (6.2, 28.0) | 12.9 (5.9, 21.0) | 0.17 |

| Troponin (ng/mL), median (Q1, Q3)§ | 0.50 (0.11, 6.75) | 0.08 (0.02, 0.59) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac complications | |||

| Cardiac involvement|| | 51 (81) | 1663 (47) | <0.001 |

| BNP or NT‐proBNP>1000 pg/mL | 33/40 (83) | 1146/1762 (65) | 0.03 |

| Elevated troponin | 42/51 (82) | 700/1939 (36) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiogram performed | 62 (98) | 2669 (75) | <0.001 |

| Normal ventricular systolic function | 20 (32) | 1682 (63) | <0.001 |

| Mild–moderate ventricular dysfunction | 22 (35) | 819 (31) | |

| Severe ventricular dysfunction | 19 (31) | 147 (6) | |

| Unknown ventricular function | 1 (2) | 22 (1) | |

| CAA (RCA or LAD z score ≥ 2.5) | 15 (24) | 256 (10) | <0.001 |

| Pericarditis or pericardial effusion | 25 (40) | 561 (21) | <0.001 |

| Critical care interventions | |||

| Any respiratory support | 51 (81) | 2089 (59) | <0.001 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 33 (53) | 585 (17) | <0.001 |

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation only | 8 (13) | 421 (12) | 1.00 |

| Vasopressor requirement | 52 (84) | 1190 (34) | <0.001 |

| ECMO¶ | 15 (24) | 88 (2) | <0.001 |

| Severity scores first 24 h | |||

| pSOFA, median (Q1, Q3) | 4 (2, 6) | 2 (1, 4) | <0.001 |

| Outcomes | |||

| ICU admission | 61 (97) | 2630 (74) | <0.001 |

| ICU length of stay, d, median (Q1, Q3) | 9 (5, 16) | 3 (2, 6) | <0.001 |

| Hospital length of stay, d, median (Q1, Q3) | 11.5 (7.25, 18.75) | 6 (4, 9) | <0.001 |

| Death | 9 (14) | 77 (2) | <0.001 |

n (%) or median (Q1, Q3); chi‐squared test, Fisher exact test, or Mann–Whitney test where appropriate. ALT indicates alanine transaminase; CRP, C‐reactive protein; BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; CAA, coronary artery aneurysm; RCA, right coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; MIS‐C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; and pSOFA, Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Measured in 60 patients with tachyarrhythmias and 3160 without.

Measured in 56 patients with tachyarrhythmias and 2778 without.

Measured in 41 patients with tachyarrhythmias and 2475 without.

Measured in 37 patients with tachyarrhythmias and 1397 without.

Defined as BNP or NT‐proBNP ≥1000 pg/mL, elevated troponin, systolic ventricular dysfunction or coronary artery aneurysm.

Includes ECMO (veno‐venous and veno‐arterial) at any point during hospitalization, irrespective of indication.

Tachyarrhythmias

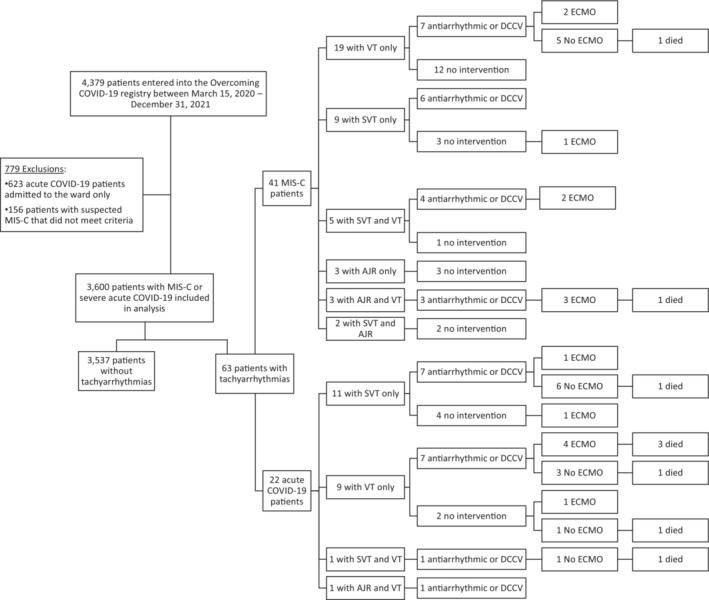

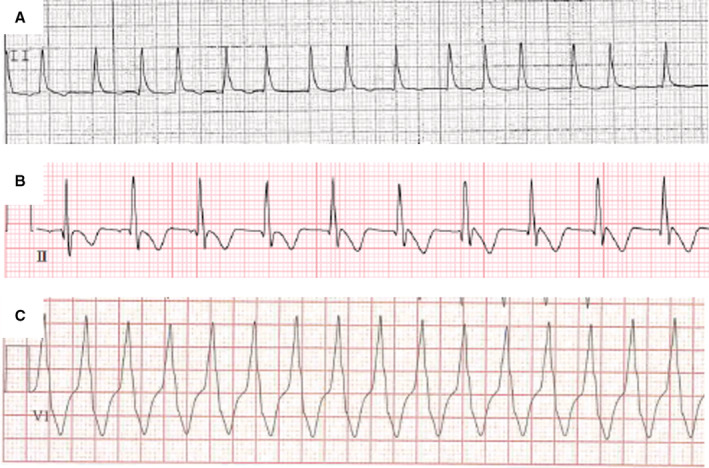

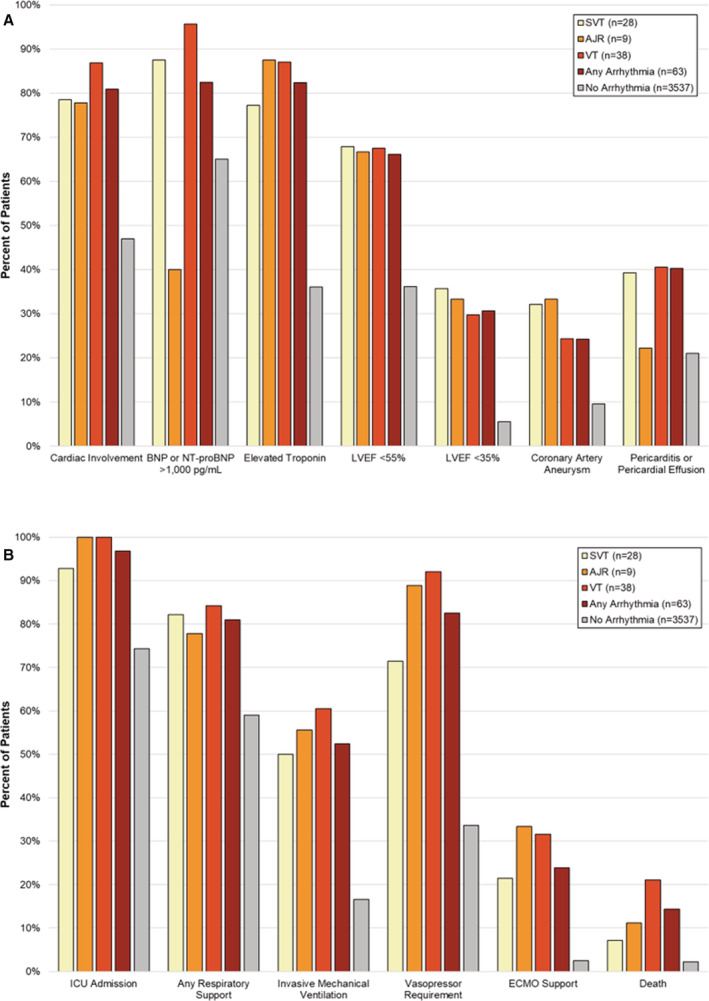

Tachyarrhythmias were reported in 22 (1.8%) registry patients with severe acute COVID‐19 and 41 (1.7%) patients with MIS‐C (Table 1, Table S1). Among patients with tachyarrhythmias, SVT was diagnosed in 28 (44%) patients (reentrant SVT in 2 patients, ectopic atrial tachycardia in 10, atrial flutter in 8, atrial fibrillation in 9, and unclassified in 1), accelerated junctional rhythm in 9 (14%), and ventricular tachycardia (VT) in 38 (60%) (nonsustained in 28, sustained in 11, ventricular fibrillation in 5; Figure 1, Figure 2). Clinical characteristics of patients grouped by type of tachyarrhythmia are shown in Figure 3, Table S2. More than 1 type of tachyarrhythmia was observed in 12 (19%) patients. Two patients (3%) had high‐grade atrioventricular block during hospital admission, in addition to tachyarrhythmias. The diagnosis of tachyarrhythmia was confirmed on 12‐lead ECG in 23 (36%) patients and the remainder by review of hospital record documentation by cardiologists (n=37, 59%) or other medical providers (n=3, 5%; Table S3). Tachyarrhythmias were identified a median of 6 (Q1, Q3: 4, 9.5) days after onset of symptoms and 2 (Q1, Q3: 0, 5) days after hospital admission (Table 2). Tachyarrhythmias resolved at a median of 1 (Q1, Q3: 0, 3; range, 0–37) day after onset.

Figure 1. CONSORT‐like diagram of tachyarrhythmias and outcomes in patients with acute severe COVID‐19 and MIS‐C.

AJR indicates accelerated junctional rhythm; DCCV, direct current cardioversion; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MIS‐C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; and VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 2. Rhythm strip showing (A) atrial fibrillation, (B) accelerated junctional rhythm, and (C) ventricular tachycardia in patients with COVID‐19 and MIS‐C.

MIS‐C indicates multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

Figure 3. Cardiac involvement (A) and outcomes (B) by type of tachyarrhythmia.

AJR indicates accelerated junctional rhythm; BNP, B‐type natriuretic peptide; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; and VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Table 2.

Tachyarrhythmia, Intervention, and Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized With MIS‐C and Acute COVID‐19 in 63 US Hospitals Participating in the “Overcoming COVID‐19” Public Health Registry, March 15, 2020, to December 31, 2021

| All patients (n=63) | Patients with MIS‐C (n=41) | Patients with acute COVID‐19 (n=22) | SVT (n=28) | Accelerated junctional rhythm (n=9) | Ventricular tachycardia (n=38) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days from symptoms to arrhythmia onset | 6 (4, 9.5) | 7 (5, 9) | 5 (2, 14) | 6 (4, 9) | 5 (5, 7) | 7 (4, 12.5) |

| Days from hospitalization to arrhythmia onset | 2 (0, 5) | 2 (1, 4) | 2 (0, 6.25) | 2 (0, 3) | 1 (0.25, 1) | 2 (1, 8.5) |

| Duration of arrhythmia, d | 1 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 4) | 1 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 4) |

| Arrhythmia interventions | ||||||

| None | 26 (41) | 20 (49) | 6 (27) | 9 (32) | 4 (44) | 15 (39) |

| Antiarrhythmic medication | 31 (49) | 17 (41) | 14 (64) | 15 (54) | 3 (33) | 20 (53) |

| Electrical cardioversion | 11 (17) | 5 (12) | 6 (27) | 8 (29) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) |

| CPR | 8 (13) | 4 (10) | 4 (18) | 2 (7) | 2 (22) | 8 (21) |

| ECMO* | 9 (14) | 6 (15) | 3 (14) | 4 (14) | 4 (44) | 8 (21) |

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Discharged home without antiarrhythmic medication | 38 (60) | 28 (68) | 10 (45) | 16 (57) | 6 (67) | 21 (55) |

| Discharged home with antiarrhythmic medication | 14 (22) | 10 (24) | 4 (18) | 8 (29) | 1 (11) | 9 (24) |

| Transferred to other facility | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | 2 (7) | 1 (11) | 0 |

| Died | 9 (14) | 2 (5) | 7 (32) | 2 (7) | 1 (11) | 8 (21) |

n (%) or median (Q1, Q3). CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MIS‐C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; and SVT, supraventricular tachycardia.

Includes ECMO cannulation specifically used for treatment of tachyarrhythmia.

Baseline 12‐lead ECGs were available to review in 22 patients (34%) with tachyarrhythmias, including 10 patients with SVT, 2 patients with accelerated junctional rhythm, and 15 patients with ventricular arrhythmia (Table S4). ST‐segment changes were the most frequent abnormality (n=15, 68%), including T‐wave inversion in 5 patients, ST‐segment elevation in 2 patients, ST‐segment depression in 1 patient, and nonspecific changes in 8 patients. Prolonged corrected QT interval was observed in 8 (24%) patients. Other changes included axis deviation, right bundle branch block, ventricular hypertrophy, first‐degree atrioventricular block, atrial pacing, premature atrial contraction, and atrial enlargement (Table S4). There were no significant differences in baseline ECG among types of arrhythmias, although comparisons are limited by small numbers.

Thirty‐seven patients with tachyarrhythmias (59%) required intervention for arrhythmia, and 26 patients (41%) had no interventions recorded (Table 2). Antiarrhythmic medications were used in 31 (49%) patients and included adenosine in 2 patients, beta‐blockers in 15, calcium channel blockers in 4, lidocaine in 5, procainamide in 4, and amiodarone in 11. Electrical cardioversion was used in 11 (17%) patients, including 8 patients with SVT (atrial fibrillation in 5, atrial flutter in 3) and 4 patients with VT. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was required in 8 (13%) patients, and 9 (14%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support because of refractory arrhythmias (SVT in 4 patients, accelerated junctional rhythm in 4, VT in 8). Antiarrhythmic treatment was most often transient, and 14 (22%) patients were discharged home on antiarrhythmic medication. Antiarrhythmic medication at time of discharge was most often a beta‐blocker (12 patients, 86%); 1 patient was discharged on digoxin and propafenone (class IC) and 1 on amiodarone. There was no significant difference in cardiac involvement or outcomes between patients treated and not treated for tachyarrhythmia (Table S5).

Comparison of Patients With and Without Tachyarrhythmias

Patients with versus without tachyarrhythmias were older (Table 1). The percentage of patients who had at least 1 underlying medical condition did not differ significantly in those with and without tachyarrhythmias; however, more were obese. In patients with tachyarrhythmias, 8 (13%) had preexisting cardiac conditions, including congenital heart disease in 4 (6%), cardiomyopathy in 2 (3%), and arrhythmias in 2 (4%).

Patients with tachyarrhythmias were sicker at the time of hospital admission, with higher Pediatric Sequential Organ Failure Assessment severity scores, more organ systems involved, and a greater frequency of other cardiac complications (Table 1).

Compared with patients without tachyarrhythmias, children with tachyarrhythmias more frequently required intensive care unit admission, mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. Children with tachyarrhythmias had longer hospital length of stay (11.5 [range, 7.25–18.75] versus 6 [range, 4–9] days; P<0.001) and higher in‐hospital mortality (14% versus 2%; P<0.001). In patients with tachyarrhythmias, causes of death were multiorgan failure in 4 (50%) patients, primary cardiac in 2 (25%), and primary respiratory in 2 (25%) (Table S6). All deaths except one occurred in patients with VT (Figure 1). Death in patients with tachyarrhythmias was most common in acute severe COVID‐19 than MIS‐C (P=0.006; Table 2). In patients without tachyarrhythmias, causes of death were primary respiratory in 29 (38%) patients, multiorgan failure in 18 (23%), primary cardiac in 12 (16%), brain death or severe brain injury in 10 (13%), and other in 8 (10%).

Cardiac Involvement and Tachyarrhythmias

Patients with tachyarrhythmias more often had other manifestations of cardiac involvement than those without (81% versus 40%, P<0.001; Table 1); however, 700 (20%) patients without recorded tachyarrhythmias did not have echocardiograms, BNP, or troponin measured (categorized as no cardiac involvement). Patients with tachyarrhythmias more often had ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction <55%), with 30% having severe ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction <35%), coronary artery aneurysms (24%), pericarditis, and pericardial effusion (40%). Coronary artery aneurysms were observed in 37% of patients with MIS‐C and tachyarrhythmia, while no patient with severe acute COVID‐19 had coronary artery aneurysm (Table S1). Although cardiovascular involvement was more frequent in patients with tachyarrhythmias, hemodynamically significant tachyarrhythmias, including sustained VT, were also observed in patients with normal ventricular systolic function on echocardiogram (Table S2).

Tachyarrhythmias in Acute COVID‐19 and MIS‐C

The majority (82%) of patients with acute COVID‐19 who developed tachyarrhythmias had underlying medical conditions compared with a minority (42%) of patients with MIS‐C. Nearly one‐quarter of patients with acute COVID‐19 and tachyarrhythmias had underlying cardiovascular conditions (n=5, 23%), including congenital heart disease in 3 (14%) patients, cardiomyopathy in 2 (9%), and arrhythmia in 2 (9%). Intensive care unit length of stay was significantly longer in patients with acute COVID‐19 versus MIS‐C (18 [Q1,Q3: 6, 28] versus 8 [Q1,Q3: 5, 12] days; P=0.043); however, there was no difference in need for mechanical ventilation (50% versus 54%, P=0.99) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (36% versus 17%; P=0.16). In‐hospital mortality was more frequent in patients with acute COVID‐19 and tachyarrhythmias than MIS‐C (32% versus 5%; P=0.006).

DISCUSSION

In this national multicenter registry of children and adolescents hospitalized with severe complications related to COVID‐19, tachyarrhythmias were infrequent, occurring in 1.8% of patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit for acute severe COVID‐19 and in 1.7% of those hospitalized for MIS‐C. Tachyarrhythmias occurred most frequently in older patients and sicker patients with cardiac or multisystem involvement. Patients with tachyarrhythmias had prolonged hospital length of stay and higher in‐hospital mortality.

There are many possible causes for tachyarrhythmias in children with SARS‐CoV‐2–related illnesses, including hypoxia, myocarditis, myocardial ischemia, electrolyte abnormalities, and medication side effects. 12 Myocardial injury, likely resulting from systemic inflammation, direct viral infection of the heart, hypoxia, stress cardiomyopathy, ischemia, or combination of these factors, 13 , 14 is associated with tachyarrhythmias in children with SARS‐CoV‐2–related illness.

Tachyarrhythmias are frequently reported in non–COVID‐related myocarditis; a large, multicenter series using the Pediatric Health Information System database described tachyarrhythmias in 12% of patients, 15 and a 2‐center series described an incidence of 40% in children with ventricular dysfunction. 16 Myocardial involvement was recorded in 67% of patients with MIS‐C and was likely a cause for tachyarrhythmias. In contrast, 23% of children with severe acute COVID‐19 and tachyarrhythmia had a preexisting cardiac condition, compared with only 2% of patients with MIS‐C. A large, worldwide survey of COVID‐19–associated arrhythmia in adults (69% with underlying cardiac comorbidities) found an incidence of tachyarrhythmia of 14%, highlighting underlying cardiovascular disease as a risk factor. 17 Thus, while tachyarrhythmias were observed in a similar frequency in patients with severe acute COVID‐19 and MIS‐C, underlying mechanisms may differ.

Patients with tachyarrhythmias had worse clinical outcomes, which has also been described in children with non‐COVID viral myocarditis 15 and adults with COVID‐19. 17 Worse outcomes may result from the underlying condition that promoted arrhythmia, such as myocardial injury, or from hemodynamic compromise produced by the arrhythmia itself. Patients with tachyarrhythmias had multiple indicators of higher illness severity on presentation. Regardless of whether adverse outcomes associated with arrhythmias reflect a more severe underlying condition, sequelae of the arrhythmia itself, or an interaction of the 2, the occurrence of arrhythmia in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2–related illness identifies a high‐risk group of patients. The risk of VT or sudden cardiac death following viral myocarditis can be as high as 50% in adults, likely from persistent inflammation or postinflammatory myocardial scar, highlighting the importance of follow‐up. 18 Cases of arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death have also been reported in children following myocarditis, including in patients with normal ventricular function. However, there is no good estimate of the risk, likely because of the rarity of events. The 2021 American Heart Association guidelines recommend avoidance of competitive sports for 3 to 6 months after myocarditis to minimize the risk of life‐threatening arrhythmia, with Holter monitoring and exercise stress testing performed in athletes before they return to sports. 19 Cardiac magnetic resonance may help better understand the long‐term myocardial and arrhythmic risk in patients with significant arrhythmias following SARS‐CoV‐2–related illness.

Limitations of this investigation include that the OC‐19 registry did not capture all eligible patients and may be biased toward the capture of more severely ill patients. Transient and benign episodes could have been underreported, with more serious events requiring intervention being captured. ECG tracings were reviewed and adjudicated when available; however, as hospital telemetry data are not routinely saved, tracings were unavailable for review in most cases because of transient and nonsustained arrhythmias. Missing data may have led to the misclassification of patients. In our adjudication, the 2 cases that were overturned were ectopic atrial tachycardia and atrial fibrillation; both of which can be challenging to distinguish clinically as well. Importantly, none of the patients with ventricular arrhythmias were re‐adjudicated. In patients with underlying cardiac disease, tachyarrhythmias may be related to exacerbation of the underlying condition, and not necessarily COVID‐19 infection. In addition, other factors related to the acute management of acutely ill patients may contribute to arrhythmias, including the use of corrected QT interval prolonging medications and electrolyte abnormalities. Most patients with acute COVID‐19 did not undergo echocardiography (n=807, 64%) or have values for BNP or troponin (n=924, 74%), potentially overestimating differences in cardiac involvement between groups. Because of the lack of long‐term follow‐up, the risk of recurrence of tachyarrhythmias following hospital discharge remains unknown.

CONCLUSIONS

Although tachyarrhythmias are an infrequent complication of SARS‐CoV‐2–related illnesses in hospitalized children and adolescents, they portend poor clinical outcomes. This highlights the importance of close monitoring and aggressive treatment in these patients. Longer‐term surveillance after hospital discharge will be important to better understand the arrhythmic and other cardiac risks after acute COVID‐19 or MIS‐C complicated by tachyarrhythmia.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under a contract to Boston Children's Hospital (#75D30120C07725). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was involved with the design and conduct of the public health investigation and review and approval of the manuscript. They did not collect or manage the data, and they did not analyze the data for this subanalysis or assist with interpretation or prepare the manuscript.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Data S1

Tables S1–S6

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate and thank the many research coordinators at the Overcoming COVID‐19 hospitals who assisted in data collection for this study, as well as the leadership of the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigator's Network for their ongoing support. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr Dionne, C.C. Young, and Dr Randolph had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This manuscript was sent to N.A. Mark Estes III, MD, Guest Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.122.025915

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dong Y, Mo X, Qi X, Jiang F, Jiang Z, Tong S. Epidemiology of COVID‐19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145:e20200702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, Xhang J, Li YY, Qu J, Zhang W, Wang Y, Bao S, Li Y, et al. Chinese pediatric novel coronavirus study team. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1663–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. CDC COVID‐19 Response Team . Coronavirus disease 2019 in children – United States, February 12‐April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:422–426. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Irfan O, Muttalib F, Tang K, Jiang L, Lassi ZS, Bhutta Z. Clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes of paediatric COVID‐19: a systematic review ad meta‐analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:440–448. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feldstein LR, Tenforde MW, Friedman KG, Newhams M, Rose EB, Dapul H, Soma VL, Maddux AB, Mourani PM, Bowens C, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of US children and adolescents with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C) compared with severe acute COVID‐19. JAMA. 2021;325:1074–1087. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, Collins JP, Newhams MM, Son MBF, Newburger JW, Kleinman LC, Heidemann SM, Martin AA, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez‐Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, Kaforou M, Jones CE, Shah P, Ramnarayan P, Fraisse A, Miller O, Davies P, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS‐CoV‐2. JAMA. 2020;324:259–269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dufort EM, Koumans EH, Chow EJ, Rosenthal EM, Muse A, Rowlands J, Barranco MA, Maxted AM, Rosenberg ES, Easton D, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York state. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:347–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, Burns JC, Bolger AF, Gewitz M, Baker AL, Jackson MA, Takahashi M, Shah PB, et al. American Heart Association rheumatic fever, endocarditis, and Kawasaki disease Committee of the Council on cardiovascular disease in the Young; council on cardiovascular and stroke nursing; council on cardiovascular surgery and anesthesia; and council on epidemiology and prevention. Diagnosis, treatment and long‐term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e927–e999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matics TJ, Sanchez‐Pinto N. Adaptation and validation of a pediatric sequential organ failure assessment score and evaluation of the sepsis‐3 definitions in critically ill children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:e172352. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dherange P, Lang J, Qian P, Oberfeld B, Sauer WH, Koplan B, Tedrow U. Arrhythmias and COVID‐19: a review. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6:1193–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F, Gong W, Liu X, Liang J, Zhao Q, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID‐19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anderson BR, Silver ES, Richmond ME, Liberman L. Usefulness of arrhythmias as predictors of death and resource utilization in children with myocarditis. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1400–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miyake CY, Teele SA, Chen L, Motonaga KS, Dubin AM, Balasbramanian S, Balise RR, Rosenthal DN, Alexander ME, Walsh EP, et al. In‐hospital arrhythmia development and outcomes in pediatric patients with acute myocarditis. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coromilas EJ, Kochav S, Goldenthal I, Biviano A, Garan H, Goldbarg S, Kim JH, Yeo I, Tracy C, Ayanian S, et al. Worldwide survey of COVID‐19‐associated arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2021;14:e00958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosier L, Zouaghi A, Barre V, Martins R, Probst V, Marijon E, Sadoul N, Chauvreau S, Da Costa A, Badoz M, et al. High risk of sustained ventricular arrhythmia recurrence after acute myocarditis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:848. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Law YM, Lal AK, Chen S, Chihakova D, Cooper LT Jr, Deshpande S, Godown J, Grosse‐Wortmann L, Robinson JD, Towbin JA. American Heart Association pediatric heart failure and transplantation Committee of the Council on lifelong congenital heart disease and heart health in the Young and stroke council. Diagnosis and Management of Myocarditis in children. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144:e123–e135. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Data S1

Tables S1–S6