Abstract

Background

Black and Hispanic patients are less likely to receive cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) than White patients. Medicaid expansion has been associated with increased access to cardiovascular care among racial and ethnic groups with higher prevalence of underinsurance. It is unknown whether the Medicaid expansion was associated with increased receipt of CRT by race and ethnicity.

Methods and Results

Using Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Data State Inpatient Databases from 19 states and Washington, DC, we analyzed 1061 patients from early‐adopter states (Medicaid expansion by January 2014) and 745 patients from nonadopter states (no implementation 2013–2014). Estimates of change in census‐adjusted rates of CRT with or without defibrillator by race and ethnicity and Medicaid adopter status 1 year before and after January 2014 were conducted using a quasi‐Poisson regression model. Following the Medicaid expansion, the rate of CRT did not significantly change among Black individuals from early‐adopter states (1.07 [95% CI, 0.78–1.48]) or nonadopter states (0.79 [95% CI, 0.57–1.09]). There were no significant changes in rates of CRT among Hispanic individuals from early‐adopter states (0.99 [95% CI, 0.70–1.38]) or nonadopter states (1.01 [95% CI, 0.65–1.57]). There was a 34% increase in CRT rates among White individuals from early‐adopter states (1.34 [95% CI, 1.05–1.70]), and no significant change among White individuals from nonadopter states (0.77 [95% CI, 0.59–1.02]). The change in CRT rates among White individuals was associated with the timing of the Medicaid implementation (P=0.003).

Conclusions

Among states participating in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Data State Inpatient Databases, implementation of Medicaid expansion was associated with increase in CRT rates among White individuals residing in states that adopted the Medicaid expansion policy. Further work is needed to address disparities in CRT among Black and Hispanic patients.

Keywords: affordable care act Medicaid expansion, cardiac resynchronization therapy, health disparities, heart failure

Subject Categories: Disparities, Health Equity, Health Services

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CRT±D

cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without defibrillator

- HCUP SID

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Data State Inpatient Databases

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without defibrillator rates increased significantly in White patients in early‐adopter states, but not in White patients in nonadopter states.

There were no significant changes in cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without defibrillator implantation in Black and Hispanic patients in both early‐ and nonadopter states.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Elimination of racial and ethnic disparities in cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without defibrillator implantation may require multidimensional system‐ and population‐wide policy interventions exceeding expansion of current insurance eligibility and coverage.

Heart failure (HF) is a major cause of morbidity and death among US adults. 1 It disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic patients. 1 , 2 Black patients have the highest age‐adjusted annual hospitalized HF incidence, 1 HF prevalence, and mortality risk. 1 , 2 Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) improves HF morbidity and mortality independent of patient race and ethnicity. 3 Nevertheless, Black and Hispanic patients are less likely than White patients to receive CRT. 2 , 3 Suboptimal use of CRT with or without defibrillator (CRT±D) in Black and Hispanic patients likely contributes to disproportionately poor HF outcomes. Given the rising costs of HF care, 1 there is an ethical imperative to increase CRT use among Black and Hispanic patients.

Uninsurance limits health care access, 4 which may contribute to underuse of CRT±D and disparate HF mortality in uninsured patients. This is of particular importance for Black and Hispanic populations, which have higher proportions of uninsurance than White individuals. 4 , 5 CRT‐eligible uninsured patients are less likely to receive CRT. 6 , 7 Advances in US health policy may help. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion narrowed uninsurance disparities across US racial subgroups, 8 increased access to quality health care, 4 , 5 , 9 and was associated with reduced HF hospitalization among Medicaid beneficiaries 10 and increased heart transplant listings among Black patients in early‐adopter states. 11

It is unclear whether the ACA Medicaid expansion was associated with increased CRT±D rates according to race and ethnicity. Using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Data State Inpatient Databases (HCUP SID) from 19 states and Washington, DC, we assessed the association between state adoption of Medicaid expansion and census‐adjusted CRT±D implantation rates for Black, Hispanic, and White patients with Medicaid insurance.

METHODS

Data Source

Deidentified HCUP SID were used to identify patients who received CRT±D between 2013 and 2015. The data from the HCUP SID encompass 97% of all hospital discharges in participating states. It contains unadjusted data on patient demographics including age (≥20 years), sex, self‐identified race and ethnicity, insurance type, primary and secondary diagnoses, and procedures. The HCUP SID is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and was developed to inform health care policy at the national, state, and community level. 12 This study was approved by the HCUP SID and participating states. This study was also deemed exempt for human subjects review by the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board. Data are not publicly available, and requests for data should go to HCUP SID.

Study Population

The study methodology has been published before. 13 Patients aged ≥20 years with a hospitalization discharge documenting CRT±D implantation were included in the study (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision [ICD‐9 and ICD‐10] codes for CRT±D are included in Data S1). This study included only non‐Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and non‐Hispanic White patients because additional racial and ethnic groups had insufficient patient numbers to analyze in the study. Race and ethnicity were administratively captured for each participating HCUP SID. Patients were excluded from the study for missing race and ethnicity. The hospital discharge quarter and year were used for the timing of the procedure because the exact date of the procedure during the time of hospitalization was not available across states.

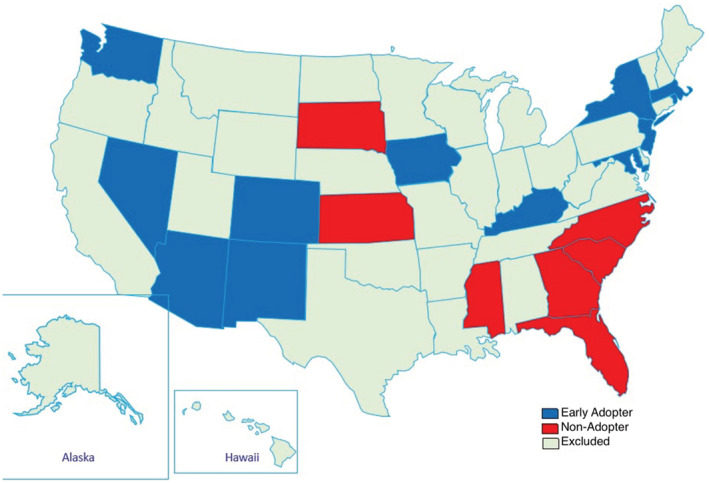

Nineteen states and Washington, DC were selected. Patients with a diagnosis code of CRT±D implants were identified and stratified by ACA Medicaid expansion adopter status (early adopter versus nonadopter [Figure 1]). The early‐adopter states group (n=12 states plus Washington, DC) comprised states that expanded Medicaid coverage by January 2014, and the nonadopter states group (n=7 states) comprised states that did not implement Medicaid expansion by December 2014. The remaining states were excluded (Data S2) for reasons that have been previously published. 13 Exclusions included adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion after January 2014 and/or adoption with lower coverage (n=7 states), missing data on patient race (n=4 states), lack of participation and/or data availability via HCUP SID at time of data purchase in spring of 2018 (n=16 states), and prohibitive costs (n=4 states). CRT±D rates by race were adjusted for differences in state populations using US Census Bureau annual estimates. 11

Figure 1. State groups stratified by Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion adopter status.

Adopter status is depicted by blue and red colors for early‐adopter states and nonadopter states, respectively.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change in census‐adjusted rates of CRT±D implants in Medicaid recipients by race and adopter status (early adopter versus nonadopter) before and after implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion in January 2014. As a secondary outcome, we compared these proportional changes between state groups (early adopter versus nonadopter), for each race and ethnicity (non‐Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non‐Hispanic White).

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of Medicaid CRT±D recipients grouped by adopter status were compared using χ2 tests. Quarterly counts of CRT±D procedures between 2013 and 2015 were stratified by race and ethnicity and Medicaid adopter status (early adopter versus nonadopter). Census estimates from July 1 of each study year (2013–2015) were obtained for patients aged ≥20 years, and the sums of these estimates were tabulated separately for race and ethnicity and state group (early adopter versus nonadopter). Assuming July 1 as the midpoint of the year and taking the midpoint of each quarter as the date, quarterly estimates were obtained through linear interpolation.

Estimates of CRT±D rates and changes in rates were based on a quasi‐Poisson regression model with terms for race and ethnicity (non‐Hispanic Black, Hispanic, or non‐Hispanic White), state group (early adopter or nonadopter), and time (pre‐ or post‐ACA implementation, January 2014) as well as all 2‐ and 3‐way interactions of these terms and an offset for census population size. A similar model was run without any race main effect (or interactions) to estimate overall changes by state group. Predicted CRT±D rates were standardized to rates per 100 00 people. Analyses were conducted in R version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). 14

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

Among CRT±D Medicaid recipients, 1061 were from early‐adopter states and 745 from nonadopter states (Table 1). Most patients in both state groups were aged 50 to 64 years. State groups differed in distribution of patients among races and ethnicity (P=0.0004), with a smaller proportion of Black patients in early‐adopter states than nonadopter states (25.9% versus 34.5%). The distribution of patients among zip code income quartiles also differed between early‐adopter and nonadopter states (P<0.0001), with early‐adopter states having a higher proportion of patients in zip codes with the highest quartile of median incomes (22.4% versus 3.1%) and a lower proportion in zip codes with the lowest quartile of median income (38.1% versus 53.4%). There was a higher proportion of metropolitan residents among patients in early‐adopter states than nonadopter states (91.33% versus 84.03%; P<0.0001). Early‐adopter states had a smaller proportion of patients with ischemic heart disease (49.67% versus 56.24%) and obesity (17.34% versus 21.88%) than nonadopter states.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy±Defibrillator Medicaid Beneficiaries (2013–2015)

| Characteristic | Early adopter, n=1061 (%) | Nonadopter, n=745 (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | 0.62 | ||

| 20–34 | 53 (5.00) | 44 (5.91) | |

| 35–49 | 214 (20.17) | 155 (20.81) | |

| 50–64 | 667 (62.87) | 469 (62.95) | |

| 65+ | 127 (11.97) | 77 (10.34) | |

| Sex | 0.91 | ||

| Women | 362 (34.12) | 256 (34.36) | |

| Race and ethnicity | 0.0004 | ||

| Non‐Hispanic Black | 275 (25.92) | 257 (34.50) | |

| Hispanic | 244 (23.00) | 147 (19.73) | |

| Non‐Hispanic White | 542 (51.08) | 341 (45.77) | |

| Zip code income quartile* | <0.0001 | ||

| 1, lowest | 404 (38.08) | 398 (53.42) | |

| 2 | 215 (20.26) | 216 (28.99) | |

| 3 | 206 (19.42) | 108 (14.50) | |

| 4, highest | 236 (22.24) | 23 (3.09) | |

| Residence type | <0.0001 | ||

| Metropolitan | 969 (91.33) | 626 (84.03) | |

| Nonmetropolitan | 92 (8.67) | 119 (15.97) | |

| Heart failure | 0.24 | ||

| Systolic | 716 (67.48) | 468 (62.82) | |

| Diastolic | 26 (2.45) | 21 (2.82) | |

| Other | 191 (18.00) | 155 (20.81) | |

| None | 128 (12.06) | 101 (13.56) | |

| Anemia | 148 (13.95) | 133 (17.85) | 0.02 |

| Coagulation defects | 17 (1.60) | 9 (1.21) | 0.49 |

| Atrial arrhythmia | 343 (32.33) | 240 (32.21) | 0.96 |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 258 (24.32) | 204 (27.38) | 0.14 |

| Complete atrioventricular block | 142 (13.38) | 87 (11.68) | 0.28 |

| Left bundle‐branch block | 365 (34.40) | 233 (31.28) | 0.16 |

| Right bundle‐branch block | 29 (2.73) | 19 (2.55) | 0.81 |

| Cardiac arrest | 44 (4.15) | 38 (5.10) | 0.34 |

| CKD | 190 (17.91) | 149 (20.00) | 0.26 |

| ESRD | 15 (1.41) | 8 (1.07) | 0.53 |

| COPD | 152 (14.33) | 151 (20.27) | 0.0009 |

| Diabetes | 357 (33.65) | 249 (33.42) | 0.92 |

| Depression | 90 (8.48) | 53 (7.11) | 0.29 |

| Hypertension | 704 (66.35) | 521 (69.93) | 0.11 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 527 (49.67) | 419 (56.24) | 0.01 |

| Obesity | 184 (17.34) | 163 (21.88) | 0.02 |

Ventricular arrhythmia includes ventricular fibrillation, flutter, tachycardia, and paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia. Other heart failure represents unspecified heart failure diagnosis; none represents cardiac resynchronization therapy±defibrillator without diagnosis of heart failure. CKD indicates chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; and ESRD, end‐stage renal disease.

The zip code income quartile represents the median household income for the patient's zip code.

Outcomes

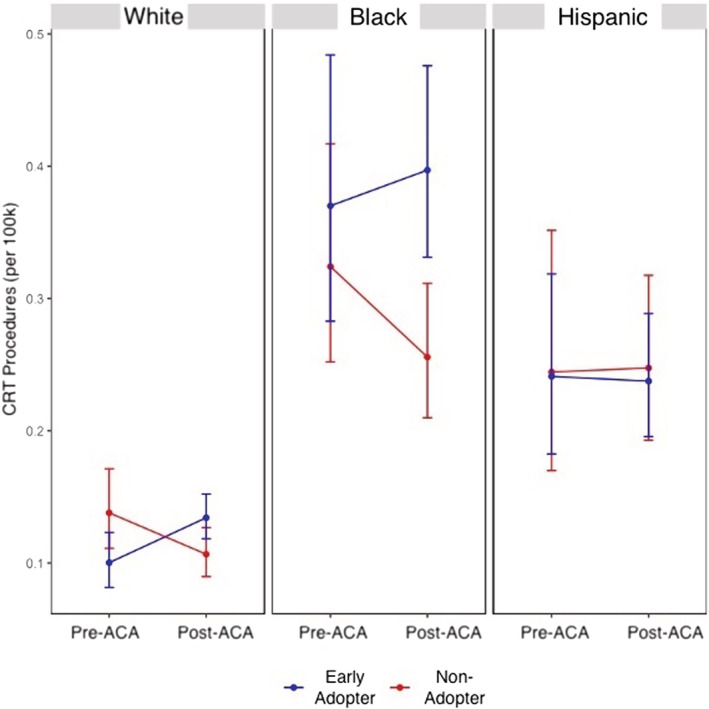

There was no significant proportional change in CRT±D rates post‐ACA versus pre‐ACA implementation among Black patients from early‐adopter states (1.07 [95% CI, 0.78–1.48]; pre‐ 0.37/100 000 to post‐ACA 0.40/100 000; P=0.67; Table 2, Figure 2) or nonadopter states (0.79 [95% CI, 0.57–1.09]; pre‐ 0.32/100 000 to post‐ACA 0.26/100 000; P=0.15). The rate of change post‐ versus pre‐ACA was not significantly different between early‐ and nonadopter state groups (P=0.19).

Table 2.

Association of ACA Medicaid Expansion With CRT±D Rates by Race and Ethnicity of Medicaid Beneficiaries

| Race and ethnicity | Average CRT rate per 100 000 (95% CI) | Proportional rate change (point estimate) after ACA Medicaid expansion of January 2014 (95% CI)* | Relative proportional rate change in CRT±D (95% CI)† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early adopter | Nonadopter | Early adopter | Nonadopter | ||||

| Pre‐ACA | Post‐ACA | Pre‐ACA | Post‐ACA | ||||

| Non‐Hispanic Black | 0.37 (0.28–0.48) | 0.40 (0.33–0.48) | 0.32 (0.25–0.42) | 0.26 (0.21–0.31) | 1.07 (0.78–1.48) | 0.79 (0.57–1.09) | 1.36 (0.86–2.15) |

| Hispanic | 0.24 (0.18–0.32) | 0.24 (0.20–0.29) | 0.24 (0.17–0.35) | 0.25 (0.19–0.32) | 0.99 (0.70–1.38) | 1.01 (0.65–1.57) | 0.97 (0.56–1.70) |

| Non‐Hispanic White | 0.10 (0.08–0.12) | 0.13 (0.12–0.15) | 0.14 (0.11–0.17) | 0.11 (0.09–0.13) | 1.34‡ (1.05–1.70) | 0.77 (0.59–1.02) | 1.73§ (1.20–2.50) |

ACA indicates Affordable Care Act; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; and CRT±D, cardiac resynchronization therapy±defibrillator.

Proportional rate change in CRT±D=(CRT±D population rate post‐ACA implementation)/(CRT±D population rate pre‐ACA implementation).

Relative proportional rate change=(adopter states rate change in CRT±D after ACA implementation)/(nonadopter states rate change in CRT±D after ACA implementation).

P=0.02.

P=0.003.

Figure 2. Association between Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion and cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without defibrillator (CRT±D) rates by race and ethnicity of Medicaid beneficiaries.

Dots represent model estimates of CRT±D rates by race pre‐ and post‐ACA Medicaid expansion in adopter (blue, n=1061) and nonadopter (red, n=745) states. Vertical lines represent 95% CIs.

Similarly, there was no significant proportional change in CRT±D implants among Hispanic patients post‐ versus pre‐ACA implementation in early‐adopter states (0.99 [95% CI, 0.70–1.38]; pre‐ 0.24/100 000 to post‐ACA 0.24/100 000; P=0.93; Table 2, Figure 2) or nonadopter states (1.01 [95% CI, 0.65–1.57]; pre‐ 0.24/100 000 to post‐ACA 0.25/100 000; P=0.96). Furthermore, the rate of change (post‐ versus pre‐ACA) in CRT±D implants was not significantly different between early‐adopter and nonadopter states (P=0.92).

White patients in early‐adopter states had a 34% proportional increase in CRT±D implants post‐ versus pre‐ACA implementation (1.34 [95% CI, 1.05–1.70]; pre‐ 0.10/100 000 to post‐ACA 0.13/100 000; P=0.02), but no significant proportional change in CRT±D implants was observed among White patients in nonadopter states (0.77 [95% CI, 0.59–1.02]; pre‐ 0.14/100 000 to post‐ACA 0.11/100 000; P=0.07; Table 2, Figure 2). In addition, the proportional change was significantly different between early and nonadopter state groups (P=0.003), with 73% greater proportional change in early‐adopter states (relative proportional change, 1.73 [95% CI, 1.20–2.50]).

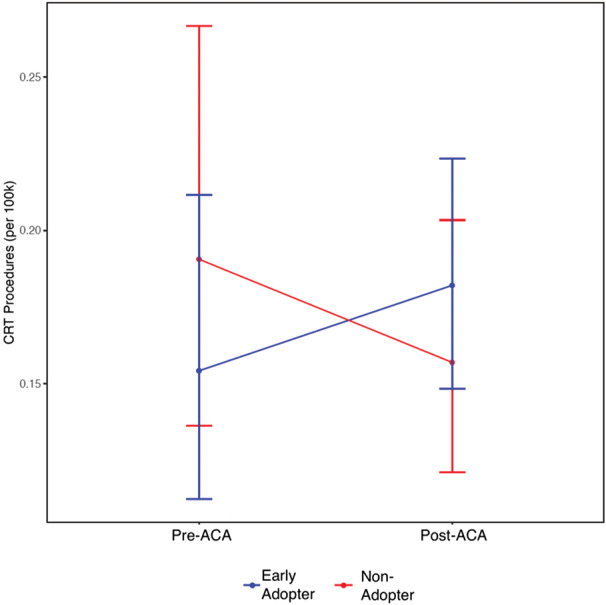

Analysis of overall CRT±D rates by adopter state group without stratification of Medicaid recipients by race and ethnicity (post‐ versus pre‐ACA in early‐ and nonadopter states) showed no significant proportional change in CRT±D rates after Medicaid expansion in early‐adopter (1.18 [95% CI, 0.81–1.72]; pre‐ 0.15/100 000 to post‐ACA 0.18/100 000; P=0.39) and nonadopter (0.82 [95% CI, 0.54–1.26]; pre‐ 0.19/100 000 and post‐ACA 0.16/100 000; P=0.37) groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Overall cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with and without defibrillator (CRT±D) rates by adopter state group (without race and ethnicity) pre‐ and post‐Medicaid expansion.

Dots represent model estimates of overall CRT±D rates by adopter state group pre‐ and post‐Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion in adopter (blue) and nonadopter (red) cohorts. Vertical lines represent 95% CIs.

DISCUSSION

In this HCUP SID study to assess the effects of ACA Medicaid expansion on CRT±D rates by race and ethnicity in US adults aged ≥20 years from 19 states and Washington, DC, Medicaid expansion was associated with 34% increase in CRT±D implants among White patients from early‐adopter states but no significant change among White patients from nonadopter states. There were no statistically significant changes in CRT±D rates among Black or Hispanic patients in either state group. From our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the role of Medicaid expansion on CRT±D implants by race and ethnicity in Medicaid beneficiaries.

This HCUP SID study adds to published data demonstrating the ACA Medicaid expansion did not narrow racial and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular care. 10 , 13 , 15 Both eligible Black and Hispanic individuals remain statistically less likely to receive CRT than White individuals. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 These results are in contrast to the observed increase in transplant listings among Black patients from early‐adopter states, 11 lower cardiovascular mortality in early‐adopter states, 20 and reported narrowing of racial disparities following the Medicaid expansion. 8 , 9 Even so, uninsurance ethnic disparities worsened for Hispanic populations in early‐adopter states after Medicaid expansion. 8

There were significant demographic differences in the distribution of CRT±D Medicaid beneficiaries between adopter and nonadopter states (Table 1). Some of these differences might be a function of state adopter status (early adopter versus nonadopter). Geographical politics and clinical decision making may contribute to care delivery as observed for other treatments. 21 Implementation of the individual mandate for people with preexisting conditions, coverage through the insurance marketplace, tax credits for reduced insurance premium and copays, and media attention and publicity of the Medicaid expansion contributed to increased enrollment. 8 , 22 Enrollment of the previously ineligible (positive spillover effects) and those who were previously eligible and crowd‐out effects (the privately insured switching to Medicaid) probably affected early‐adopter and nonadopter states differently. 22

Although this study could not investigate causality for the observed CRT rates by race and ethnicity after Medicaid implementation, inferences can be drawn from the study findings. Unequal coverage for Medicaid recipients because of variable state‐level policies on coverage, including subspecialty cardiovascular care, 23 , 24 potentially created gaps in care that disproportionately impacted Black and Hispanic populations. The higher number of Medicaid‐eligible White patients 8 likely explained the increase in CRT±D implants among White individuals in early‐adopter states after the ACA implementation. Medicaid expansion increased insurance coverage and health care access to life‐saving therapies including CRT among White populations in early‐adopter states.

Greater increases in CRT±D among Black and Hispanic populations would be anticipated after Medicaid expansion given the higher uninsurance proportions. 8 However, there was no increase in CRT±D implants among Black and Hispanic populations, which suggests that decisions to implant CRT±D expand beyond having insurance. Structural/systemic racism promoting differential racial and ethnic access to specialist cardiovascular care including CRT likely contributed to lower CRT rates in Black and Hispanic populations. 3 , 25 , 26 , 27 Related factors may have contributed to lower CRT implantation among Black and Hispanic patients such as physician bias, untrustworthy health care system, inadequate shared patient decision making, and patient comorbidities. 2 , 28 , 29

There is an urgent need for federal, state, and institutional policies to address equity. Broadening access to insurance with universal coverage may be a step in the right direction, but additional changes are needed to prevent racial and ethnic populations from receiving systematic disparate levels of care.

Support for implementation research must be strengthened to identify alternatives to existing system‐level policies that perpetuate delivery of poor‐quality health care to patients of color. Quality improvement targets should include improving patient–physician communication, 29 increasing racial and ethnic patient–physician concordance for minoritized patient groups, developing a trustworthy health care system as defined by patients, and eradicating impact of clinician and health care team bias upon clinical care delivery. 2 Development and implementation of effective interventions may require community, academic/hospital, and political partnerships empowered with resources to create changes in health care delivery.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, lack of participation of some states in the HCUP SID may limit generalizability of these study results to the rest of the US population. Notwithstanding, HCUP SID data were adjusted for differences in state populations using the US Census Bureau annual estimates, and the observed CRT trends were consistent with national trends. 3 Second, we were not able to adjust for individual patient risk factors and comorbidities, which may affect CRT eligibility and impact study results because state census data lacked information on state‐level disease prevalence. In addition, we did not adjust for patient‐level factors (sex, income, residence) and health care professional‐/physician‐level factors that can influence CRT uptake.

CONCLUSIONS

Among Medicaid beneficiaries in the HCUP SID study, Medicaid expansion was associated with increased CRT±D implants among White patients in early‐adopter states but did not improve racial disparities in CRT±D implants. Multifaceted system‐ and population‐wide interventions exceeding Medicaid expansion are needed to eliminate racial disparities in CRT±D implants. Implementation research targeting causes of the underlying structural and systemic barriers to CRT access may help narrow existing disparities in CRT±D implantation.

Sources of Funding

Dr Breathett received support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant numbers R56HL159216, K01HL142848, and L30HL148881. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosures

None reported.

Supporting information

Data S1

This article was sent to N. A. Mark Estes III, MD, Guest Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Presented in part at ACC.21: American College of Cardiology's 70th Annual Scientific Session & Expo, a virtual experience, May 15–17, 2021, and published in abstract form [J Am Coll of Cardiol. 77;784 or https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735‐1097(21) 02143‐4].

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.122.026766

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 8.

References

- 1. Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, Boehme AK, Buxton AE, Carson AP, Commodore‐Mensah Y, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145:e153–e639. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mwansa H, Lewsey S, Mazimba S, Breathett K. Racial/Ethnic and gender disparities in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2021;18:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s11897-021-00502-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sridhar ARM, Yarlagadda V, Parasa S, Reddy YM, Patel D, Lakkireddy D, Wilkoff BL, Dawn B. Cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9:e003108. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tolbert J, Orgera K, Damico A. Key Facts about the Uninsured Population. KFF. 2020.

- 5. Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity: the Potential Impact of the Affordable Care Act . KFF. 2013.

- 6. Ahmed I, Merchant FM, Curtis JP, Parzynski CS, Lampert R. Impact of insurance status on ICD implantation practice patterns: insights from the NCDR ICD registry. Am Heart J. 2021;235:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel NJ, Edla S, Deshmukh A, Nalluri N, Patel N, Agnihotri K, Patel A, Savani C, Patel N, Bhimani R, et al. Gender, racial, and health insurance differences in the trend of implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator (ICD) utilization: a United States experience over the last decade. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39:63–71. doi: 10.1002/clc.22496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McMorrow S, Long SK, Kenney GM, Anderson N. Uninsurance disparities have narrowed for Black and Hispanic adults under the affordable care act. Health Aff. 2015;34:1774–1778. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Aff. 2018;37:944–950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wadhera RK, Maddox KEJ, Fonarow GC, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA, DeVore AD, Hernandez AF, Yancy CW, Bhatt DL. Association of the affordable care act's medicaid expansion with care quality and outcomes for low‐income patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circ: Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004729. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.11.suppl_1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Breathett K, Allen LA, Helmkamp L, Colborn K, Daugherty SL, Khazanie P, Lindrooth R, Peterson PN. The affordable care act medicaid expansion correlated with increased heart transplant listings in African‐Americans but not Hispanics or Caucasians. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. HCUP‐US Home Page . Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/

- 13. Breathett KK, Knapp SM, Wightman P, Desai A, Mazimba S, Calhoun E, Sweitzer N. Is the affordable care act medicaid expansion linked to change in rate of ventricular assist device implantation for blacks and whites? Uninsurance disparities have narrowed for Black and Hispanic adults under the affordable care act. Circ: Heart Failure. 2020;13:e006544. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing . Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.r‐project.org/

- 15. Breathett KK, Xu H, Sweitzer NK, Calhoun E, Matsouaka RA, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC, DeVore AD, Bhatt DL, Peterson PN. Is the affordable care act medicaid expansion associated with receipt of heart failure guideline‐directed medical therapy by race and ethnicity? Am Heart J. 2022;244:135–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Farmer SA, Kirkpatrick JN, Heidenreich PA, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Groeneveld PW. Ethnic and racial disparities in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eapen Z, Al‐Khatib S, Lopes R, Wang Y, Bao H, Curtis J, Heidenreich P, Hernandez A, Peterson E, Hammill S. Are Racial/Ethnic gaps in the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy narrowing? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1577–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Capers Q, Sharalaya Z. Racial disparities in cardiovascular care: a review of culprits and potential solutions. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2014;1:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0021-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Piccini JP, Hernandez AF, Dai D, Thomas KL, Lewis WR, Yancy CW, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC. Use of cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circulation. 2008;118:926–933. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.773838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khatana SAM, Bhatla A, Nathan AS, Giri J, Shen C, Kazi DS, Yeh RW, Groeneveld PW. Association of Medicaid expansion with cardiovascular mortality. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:671–679. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Breathett K, Knapp SM, Carnes M, Calhoun E, Sweitzer NK. Imbalance in heart transplant to heart failure mortality ratio among African American, Hispanic, and White patients. Circulation. 2021;143:2412–2414. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sommers BD, Kenney GM, Epstein AM. New evidence on the affordable care act: coverage impacts of early Medicaid expansions. Health Affairs. 2014;33:78–87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Manthous CA, Sofair AN. On Medicaid and the affordable care act in connecticut. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87:583–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dorner SC, Jacobs DB, Sommers BD. Adequacy of outpatient specialty care access in marketplace plans under the affordable care act. JAMA. 2015;314:1749–1750. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Breathett K, Yee E, Pool N, Hebdon M, Crist JD, Yee RH, Knapp SM, Solola S, Luy L, Herrera‐Theut K, et al. Association of gender and race with allocation of advanced heart failure therapies. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011044. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, Liang L, Al‐Khatib SM, Curtis LH, LaBresh KA, Yang CW, Albert NM, Peterson ED. Sex and racial differences in the use of implantable cardioverter‐defibrillators among patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;298:1525–1532. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.13.1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Breathett K, Yee E, Pool N, Hebdon M, Crist JD, Knapp S, Larsen A, Solola S, Luy L, Herrera‐Theut K, et al. Does race influence decision making for advanced heart failure therapies? J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013592. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Churchwell K, Elkind MSV, Benjamin RM, Carson AP, Chang EK, Lawrence W, Mills A, Odom TM, Rodriguez CJ, Rodriguez F, et al. Call to action: structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e454–e468. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas KL, Zimmer LO, Dai D, Al‐Khatib SM, Allen LaPointe NM, Peterson ED. Educational videos to reduce racial disparities in ICD therapy via innovative designs (VIVID): a randomized clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2013;166:157–163.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1