Abstract

Background

Late gadolinium enhancement and left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction on cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) are prognostic markers, but their predictive value for incident heart failure or life‐threatening arrhythmias in acute myocarditis patients is limited. CMR‐derived feature tracking provides a more sensitive analysis of myocardial function and may improve risk stratification in myocarditis. In this study, the prognostic value of LV, right ventricular, and left atrial strain in acute myocarditis patients is evaluated.

Methods and Results

In this multicenter retrospective study, patients with CMR‐proven acute myocarditis were included. The primary end point was occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events: all‐cause mortality, heart transplantation, heart failure hospitalizations, and life threatening arrhythmias. LV global longitudinal strain, global circumferential strain and global radial strain, right ventricular‐global longitudinal strain and left atrial strain were measured. Unadjusted and adjusted cox proportional hazard regression analysis were performed. In total, 162 CMR‐proven myocarditis patients were included (41 ± 17 years, 75% men). Mean LV ejection fraction was 51 ± 12%, and 144 (89%) patients had presence of late gadolinium enhancement. Major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 29 (18%) patients during a follow‐up of 5.5 (2.2–8.3) years. All LV strain parameters were independent predictors of outcome beyond clinical features, LV ejection fraction and late gadolinium enhancement (LV‐global longitudinal strain: hazard ratio [HR] 1.07, P=0.02; LV‐global circumferential strain: HR 1.15, P=0.02; LV‐global radial strain: HR 0.98, P=0.03), but right ventricular or left atrial strain did not predict outcome.

Conclusions

CMR‐derived LV strain analysis provides independent prognostic value on top of clinical parameters, LV ejection fraction and late gadolinium enhancement in acute myocarditis patients, while left atrial and right ventricular strain seem to be of less importance.

Keywords: acute myocarditis, feature tracking, myocardial strain, prognosis—CMR

Subject Categories: Inflammatory Heart Disease, Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), Mortality/Survival, Clinical Studies

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- GCS

global circumferential strain

- GLS

global longitudinal strain

- GRS

global radial strain

- LGE

late gadolinium enhancement

- LTA

life threatening arrhythmias

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular events

Clinical Perspective

What is New?

In this multicenter observational study of 162 acute myocarditis patients, left ventricular strain parameters are independent predictors of major adverse cardiovascular events (longitudinal strain: hazard ratio [HR] 1.07, P=0.02; circumferential strain: HR 1.15, P=0.02; radial strain: HR 0.98, P=0.03); right ventricular and left atrial strain were not.

Late gadolinium enhancement extent was not associated with event‐free survival.

What are the Clinical Implications?

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance is widely recommended and used in patients with suspected myocarditis, and feature‐tracking derived left ventricular strain, which can be easily measured on standard cine images, may improve risk stratification.

The findings of this study support the incremental prognostic value of feature tracking strain in acute myocarditis patients, stressing the need for future research to improve risk stratification.

Acute myocarditis is an inflammatory disease of the myocardium with a great variation in clinical presentation, ranging from subclinical disease to cardiogenic shock and life‐threatening arrhythmias (LTA). 1 Up to 20 percent of patients develop incident heart failure (HF), and/or dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with persistent myocardial dysfunction after an acute episode of myocarditis. 1 Currently, cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) plays a major role in both the diagnostic process and prognostic stratification of myocarditis patients. It provides insight in cardiac function and the extent of cardiac inflammation and/or fibrosis. 1 , 2 , 3 The prognostic value of LGE and LVEF is unclear in acute myocarditis. Whereas some studies suggest that these parameters have prognostic value, 4 , 5 , 6 others did not find LGE extent to be associated with outcome in acute myocarditis. 7 , 8 Consequently, it remains challenging to distinguish patients who are at risk for HF or LTAs, and how to monitor them. 4 , 5 Since inflammation and scarring, which can lead to HF and LTAs in the future, are often only locally present in the myocardium, global functional parameters such as left‐ and right‐ventricular (RV) volumes and EF are less sensitive to detect these subtle changes. The recently developed post‐processing CMR‐technique feature tracking measures myocardial deformation also known as strain. Feature tracking strain can detect more subtle and local changes in cardiac function. 9 In substantial proportions of HF patients with recovered LVEF and relatives of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy with normal LVEF, decreased LV strain values have been detected, which are associated with worse outcome. 10 , 11 The pathophysiological process of acute myocarditis does not only involve the LV but can also cause RV dysfunction. 12 , 13 , 14 Biventricular dysfunction may also predict a worse prognosis, 1 but data about the prognostic value of RV global longitudinal strain (GLS) are lacking. Finally, the prognostic impact of left atrial (LA) functional decline preceding HF remains completely unknown. 15 LA function might be of special interest in acute myocarditis patients, who often do not present with overt HF at initial presentation. LA dysfunction might be a precursor of developing HF in the long term, and as such predict worse outcome. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to perform a comprehensive strain analysis of the heart and to evaluate the prognostic value of CMR‐derived LV, RV, and LA strain parameters in acute myocarditis patients.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Design

Four Dutch clinical centers participated in this retrospective multicenter study: Radboud University Medical Center, Maastricht University Medical Center, Amsterdam University Medical Center, and Erasmus Medical Center. These secondary (or even tertiary) centers are chosen by the study team. All centers are located in urban areas and provide clinical care for both local and referred patients. Suspected acute myocarditis patients who underwent CMR between 2005 and 2019 were identified in local electronic databases by searching for ‘myocarditis’ in the CMR report field. Patients were included based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) ≥1 clinical symptom and ≥1 diagnostic criterium, or ≥2 diagnostic criteria from different diagnostic categories as stated in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) position statement; 1 (2) absence or low pretest probability of significant coronary artery disease (stenosis ≥50%) or known pre‐existing cardiovascular disease that could explain the syndrome; (3) ≥1 diagnostic CMR myocarditis criterium; (4) a maximum time‐frame of 3 months between CMR and hospitalization; and (5) CMR cine images available for offline analysis. Two patients were excluded due to poor quality of the images, 6 patients were lost to follow‐up (Figure S1). Data regarding medical history, clinical presentation and electrocardiography were collected using medical records. The study was performed according to the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local institutional medical ethics committees. Written informed consent was either obtained or waived by the local institutional review board.

Follow‐Up

The primary predefined end point was the combination of all‐cause mortality, heart transplantation, HF hospitalization, and LTAs. Follow‐up data were collected using medical records. End of follow‐up was June 2020. LTAs were defined as ventricular fibrillation (with or without implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator shock), hemodynamic unstable ventricular tachycardia, or sustained ventricular tachycardia with implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator shock.

CMR Acquisition and Analysis

CMR imaging was performed on a 1.5T MRI system (Intera, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). Standard cine images were acquired with electrocardiogram gating during repeated end‐expiratory breath holds with the patient in supine position. Offline post‐processing analyses of all CMR scans were performed on Medis software (Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, The Netherlands). Consecutive short‐axis cine images from base to apex were analyzed to measure LV and RV volumes, LV mass and calculate ventricular EF. Average LA volumes and atrial EF were measured on the 2‐ and 4‐chamber cine images, using the biplane Simpson's area‐length method. 16 LGE images, performed 10–15 minutes after administration of an intravenous bolus of a gadolinium‐based contrast, were acquired using a two‐dimensional, segmented inversion‐recovery prepared gradient echo pulse sequence, with similar views as used for the cine‐images. The presence of LGE was first assessed visually. If present, LGE extent was quantified in the short‐axis images using the full‐width at half maximum technique (in grams, and as percentage of total LV mass) and contours where manually adjusted when needed. 17 Nonspecific RV insertion point fibrosis was excluded from the LGE analysis. 18 Presence of edema on the T2‐weighted images were analyzed. Normal LVEF or RVEF was defined as ≥50%, as stated in the latest guidelines. 19

CMR Feature Tracking Analysis

Two trained independent investigators (JV and AR), blinded to outcome and supervised by a level III CMR physician with >15 years of experience (RN), performed offline strain analyses using dedicated software (Qstrain, Medis BV, version 2.0.48.8. Leiden, the Netherlands). LV‐GLS (on 2‐ and 4‐chamber cine images), RV‐GLS (on 4‐chamber cine images), and LV global circumferential and radial strain (GCS and GRS; on mid‐ventricular short‐axis cine images) were measured. GLS and GCS are both expressed as negative values, and GRS is expressed as a positive value. Endocardial contours were manually drawn in the end‐systolic and end‐diastolic frame, after which the software automatically tracks endocardial contours in all other consecutive frames. Ventricular contraction time was defined as the time to peak. LV‐GCS and LV‐GRS were not available in 5 patients due to insufficient quality. LA phasic strain was measured on the 2‐, and 4‐chamber cine images, and the reservoir (pulmonary venous return during LV systole), conduit (passive filling from the LA to the LV in early and mid‐diastole), and booster strain (LA contraction in late diastole) were measured.

To evaluate the inter‐ and intraobserver variability, a sub analysis of 20 randomly selected CMR scans was performed. Strain analyses of these CMR scans were performed by both investigators and interobserver variability was assessed. In addition, one of the investigators repeated the strain measurements in the same 20 CMR scans, at least 2 weeks after the first measurement, to evaluate intraobserver variability.

Estimation of Strain Reference Values

Current literature does not provide reference values for all strain parameters. JV and AR analyzed CMR‐images of 20 healthy volunteers, matched for age and sex, and free of cardiovascular disease. All volunteers were scanned on a GE Sigma Artist 1.5T MR scanner. The protocol was similar as for the acute myocarditis patients. Reference values were calculated based on the standard deviation (SD) of the average value of both analyzers (<2SD). Reference values are summarized in Table S1.

Statistical Analysis

Variables are displayed as numbers (percentage), mean ± SD or median (interquartile range [IQR]). Comparisons between groups were performed using 𝜒2 tests (or Fisher exact where necessary) for categorical variables, independent samples T‐test for normally distributed, or Mann Whitney‐U test for not normally distributed, continuous variables. Inter‐ and intraobserver variability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were estimated for strain parameters using quartiles and differences were assessed by the log‐rank test. Unadjusted and adjusted cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed to determine the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of all strain parameters (included as continuous parameters). Covariates that are previously suggested to have prognostic value in acute myocarditis (LVEF, RVEF, sex, age, medical history of autoimmune disease, STEMI‐like presentation, presence of septal LGE, and LGE extent 5 , 6 , 7 ) were univariably tested for their significance in this study population, and, when significant, included in the adjusted models (Table S2). Statistical analysis was performed by JV and AR, supervised by KR, using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armon, NY). A P‐value <0.05 was considered the threshold for significance of an association, without correction for multiplicity in this explorative study. RN had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for its integrity and the data analysis.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 162 patients have been included between 2005 and 2019. Clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Male sex predominated (75%), and the median age was 40 [27–54] years. Patients presented with a ST‐elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)‐like presentation in 46% (n=74), with complaints of chest pain and elevated cardiac troponins. Significant coronary artery disease was ruled out in 100 patients (62%) using invasive coronary angiography, in six using coronary computed tomography, and in the remaining patients the clinical pre‐test probability for coronary artery disease was too low to perform coronary imaging.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patient Population

| All (n=162) | No MACE (n=133) | MACE (n=29) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics (162/162) | ||||

| Age (y) | 40 [27–54] | 35 [25–51] | 56 [44–67] | <0.001 |

| Male | 121 (75) | 104 (78) | 17 (59) | 0.03 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 25 ± 4 | 25 ± 4 | 26 ± 5 | 0.57 |

| Medical history (162/162) | ||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 4 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (7) | 0.22 |

| Pericarditis | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 1 (3) | 1.00 |

| Myocarditis | 9 (6) | 8 (6) | 1 (3) | 1.00 |

| Hypertension | 26 (16) | 19 (14) | 6 (21) | 0.41 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 14 (9) | 7 (5) | 7 (24) | <0.01 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6 (4) | 5 (4) | 2 (7) | 0.61 |

| Diabetes | 5 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (10) | 0.04 |

| Autoinflammatory disease | 24 (15) | 17 (13) | 7 (24) | 0.16 |

| Clinical presentation (162/162) | ||||

| Chest pain | 123 (76) | 109 (82) | 15 (52) | <0.01 |

| Dyspnea | 56 (35) | 40 (30) | 14 (48) | 0.08 |

| Collapse | 12 (7) | 7 (5) | 4 (14) | 0.12 |

| Flulike symptoms | 98 (61) | 86 (65) | 12 (41) | 0.02 |

| Fever | 58 (36) | 52 (39) | 6 (21) | 0.06 |

| Use of toxic substances | 9 (6) | 5 (4) | 3 (10) | 0.16 |

| Smoking status | 0.12 | |||

| Never | 112 (69) | 85 (64) | 23 (79) | |

| Former smoker | 20 (12) | 16 (12) | 5 (17) | |

| Current smoker | 30 (19) | 29 (22) | 1 (3) | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 87 ± 27 | 85 ± 22 | 99 ± 44 | 0.02 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 128 ± 24 | 129 ± 24 | 122 ± 22 | 0.22 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 78 ± 16 | 79 ± 16 | 76 ± 17 | 0.42 |

| Killip class | 0.05 | |||

| Class I | 141 (87) | 119 (89) | 22 (76) | |

| Class II | 15 (9) | 9 (7) | 4 (14) | |

| Class III | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| Class IV | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 2 (7) | |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| Creatinine (μmol/L) at admittance (n=159) | 77 [68–91] | 77 [69–90] | 83 [70–104] | 0.11 |

| Elevated troponin (%) (n=154) | 147 (91) | 121 [92] | 25 [86] | 0.16 |

| Creatine kinase, maximum (U/L) (n=142) | 395 [163–836] | 482 [218–886] | 155 [85–324] | <0.01 |

| NTproBNP, maximum (pmol/L) (n=58) | 506 [72–3071] | 371 [57–1693] | 3600 [335–10 473] | 0.02 |

| Leucocytes, maximum (10E9/L) (n=156) | 10.9 [8.0–14.2] | 10.9 [7.9–13.8] | 10.4 [7.4–15.4] | 0.13 |

| C‐reactive protein, maximum (mg/L) (n=156) | 45 [15–123] | 45 [18–129] | 26 [6–113] | 0.01 |

| Electrocardiography (162/162) | ||||

| Conduction disorders | ||||

| High degree AV‐block (2nd or 3rd degree) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1.00 |

| Left bundle branch block | 6 (4) | 3 (2) | 3 (10) | 0.08 |

| Right bundle branch block | 6 (4) | 5 (4) | 1 (3) | 1.00 |

| ST‐segment elevation | 88 (54) | 77 (58) | 12 (41) | 0.14 |

| ST‐segment depression | 38 (24) | 34 (26) | 5 (17) | 0.47 |

| Genetic testing | ||||

| Performed | 12 (7) | 6 (5) | 6 (21) | 0.008 |

| Pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutation | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | |

| Admission (162/162) | ||||

| Admission duration (days) | 7 [4–11] | 6 (4–10) | 9 (6–16) | 0.01 |

| Transfer to intensive care unit | 18 (11) | 15 (11) | 3 (10) | 1.00 |

| Start of immunosuppressive therapy | 23 (14) | 18 (14) | 5 (17) | 0.57 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or number (%).

Abbreviations: BMI indicates body mass index; and MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event.

Almost half of the patients had viral myocarditis (49%). Nine percent had an auto‐immune disease causing the myocarditis and one‐third had an unknown cause. Other less frequent etiologies are summarized in Table S3. EMB was performed in 21 patients (13%) during hospital admission showing signs of active myocarditis. Lymphocytic myocarditis was present in 15 patients (71%). One patient had signs of neutrophilic myocarditis, 2 patients had signs of eosinophilic myocarditis and 2 patients had giant cell myocarditis. The explanted heart of the patient who underwent a heart transplantation showed giant cell myocarditis with progressive myocardial injury.

CMR Parameters and Feature Tracking Parameters

The median time between admission and CMR was 6 (3–9) days. All CMR parameters are described in Table 2. Fifty‐four (33%) patients had reduced LVEF (<50%), and 41 (25%) patients had reduced RVEF (<50%). Biventricular dysfunction was present in 28 patients (17%).

Table 2.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Parameters of Patient Population

| All (n=162) | No MACE (n=133) | MACE (n=29) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional parameters (162/162) | ||||

| Left ventricle | ||||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 51 ± 12 | 53 ± 12 | 46 ± 15 | <0.01 |

| End‐diastolic volume, indexed (mL/m2) | 96 ± 29 | 94 ± 28 | 99 ± 31 | 0.40 |

| End‐systolic volume, indexed (mL/m2) | 49 ± 29 | 46 ± 27 | 56 ± 32 | 0.10 |

| Mass, indexed (g/m2) | 61 ± 15 | 60 ± 15 | 60 ± 18 | 0.95 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 6.6 ± 1.7 | 6.7 ± 1.7 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 0.10 |

| Right ventricle | ||||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 53 ± 9 | 54 ± 8 | 51 ± 13 | 0.17 |

| End‐diastolic volume, indexed (mL/m2) | 86 ± 23 | 86 ± 22 | 81 ± 28 | 0.28 |

| End‐systolic volume, indexed (mL/m2) | 40 ± 15 | 40 ± 14 | 41 ± 21 | 0.88 |

| Left atrium | ||||

| Ejection fraction (%) | 57 ± 11 | 58 ± 10 | 51 ± 14 | <0.01 |

| End‐diastolic volume, indexed (mL/m2) | 44 ± 14 | 19 ± 9 | 23 ± 12 | 0.08 |

| End‐systolic volume, indexed (mL/m2) | 20 ± 10 | 44 ± 13 | 45 ± 17 | 0.65 |

| Late gadolinium enhancement (162/162) | ||||

| Present | 145 (90) | 121 (91) | 24 (83) | 0.20 |

| Distribution | ||||

| Subendocardial/transmural | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Nonischemic, (sub)epicardial | 97 (60) | 86 (65) | 10 (34) | <0.01 |

| Nonischemic, midmyocardial | 107 (66) | 89 (67) | 18 (62) | 0.58 |

| Patchy | 16 (10) | 14 (11) | 2 (7) | 0.74 |

| Right ventricular enhancement | 6 (4) | 4 (3) | 2 (7) | 0.30 |

| Presence of septal LGE | 45 (28) | 35 (26) | 10 (35) | 0.37 |

| Quantification (% of left ventricle) | 5.5 [2.6–8.9] | 5.5 [2.7–9.0] | 4.2 [0.2–8.3] | 0.35 |

| T2 weighted imaging | ||||

| Performed | 158 (97) | 127 (95) | 29 (100) | 0.29 |

| Myocardial edema present | 121 (74) | 102 (77) | 18 (62) | 0.27 |

| Insufficient quality | 7 (4) | 3 (2) | 4 (14) | |

| Pathological pericardial effusion* (162/162) | ||||

| Focal | 25 (15) | 20 (15) | 5 (17) | |

| Global | 12 (7) | 9 (7) | 3 (10) | |

| Amount (maximum in diastole, cm) | 0.76 [0.60–1.09] | 0.78 [0.60–1.09] | 0.66 [0.60–1.33] | 0.77 |

| Strain parameters | ||||

| Left ventricle | ||||

| Global longitudinal strain (162/162) | ||||

| Peak strain (%) | −21 ± 6 | −22 ± 5 | −17 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| Time to peak (% of whole cycle) | 43 ± 8 | 43 ± 7 | 47 ± 13 | <0.004 |

| Global circumferential strain (157/162) | ||||

| Peak strain (%) | −26 ± 8 | −27 ± 8 | −22 ± 8 | <0.003 |

| Time to peak (% of whole cycle) | 42 ± 11 | 41 ± 9 | 49 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| Global radial strain (157/162) | ||||

| Peak strain (%) | 52 ± 18 | 55 ± 17 | 42 ± 20 | <0.001 |

| Time to peak (% of whole cycle) | 59 ± 39 | 55 ± 36 | 75 ± 48 | 0.02 |

| Right ventricle | ||||

| Global longitudinal strain (162/162) | ||||

| Peak strain (%) | −26 ± 7 | −27 ± 7 | −25 ± 6 | 0.20 |

| Time to peak (% of whole cycle) | 43 ± 13 | 42 ± 11 | 43 ± 11 | 0.68 |

| Left atrial phasic strain | ||||

| Reservoir (%) (162/162) | 35 ± 11 | 36 ± 11 | 30 ± 12 | <0.007 |

| Conduit (%) (162/162) | 19 ± 9 | 16.22 ± 5.94 | 15 ± 7 | 0.22 |

| Booster (%) (162/162) | 16 ± 6 | 20 ± 8 | 15 ± 8 | <0.006 |

| Time between admission and CMR (days) (162/162) | 6 [4–10] | 6 [4–10] | 9 [6–16] | 0.009 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or number (%).

Pathological pericardial effusion =>0.5 cm effusion.

CMR indicates cardiovascular magnetic imaging; and MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event.

LV‐GLS was impaired in 45 (28%) patients, LV‐GCS was impaired in 28 (18%) patients, and LV‐GRS was impaired in 61 (39%) patients. RV‐GLS was −26 ± 7 impaired in 20 (13%) patients. In only 15 (10%) patients, both LV and RV‐GLS were impaired, based on the predefined reference values.

LA reservoir strain was impaired in 22 (14%) patients. LA conduit and LA booster were impaired in 19 (12%) and 28 (17%) patients, respectively.

T2 weighted imaging was performed in 158 (97%) patients. Myocardial edema was present on the T2 weighted images in 120 (74%) patients. Nonischemic LGE was observed in 144 (89%) patients, predominantly in the septal or lateral LV wall with either a mid‐wall or (sub)epicardial pattern. LGE quantification was feasible in 138 (96%) patients with LGE and resulted – together with the patients without LGE – in a median of 5.5% of the LV mass (IQR 2.6–8.9%, Table 2).

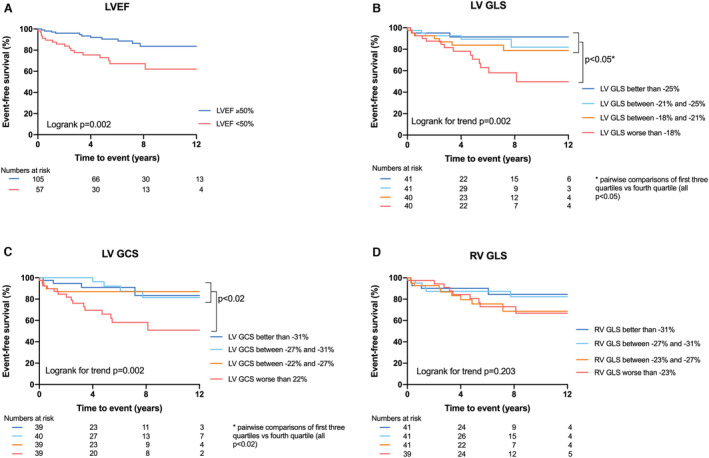

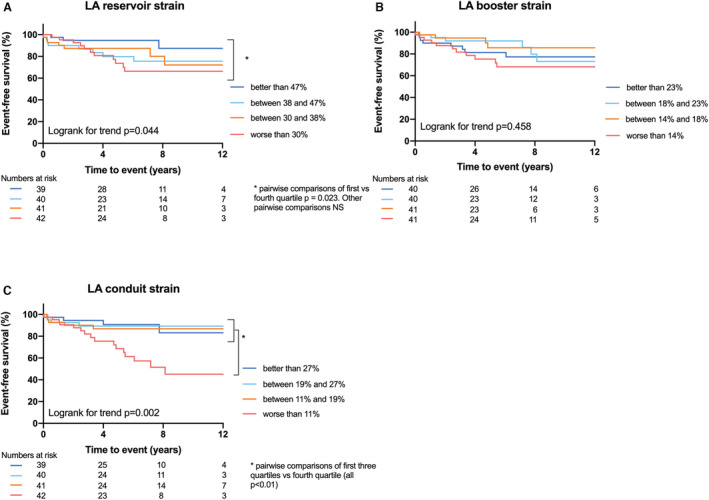

Association Between the Individual Strain Parameters, LVEF, and LGE Extent With Occurrence of MACE

In total, 18% (29/162) of the patients reached the primary end point of MACE (all‐cause death [n=17], heart transplantation [n=1], LTA [n=11], and HF hospitalization [n=7]) during a median follow‐up of 5.5 (2.2–8.3) years (Table S4). Six patients were lost to follow‐up, all after at least 1 year of follow‐up. Patients with LVEF <50% had a worse prognosis compared to patients with LVEF ≥50% (P=0.002, Figure 1A). When we categorized the study population into subgroups of quartile values, all LV strain parameters were associated with prognosis (Log rank for trend: LV‐GLS P=0.002, LV‐GCS P=0.002, LV‐GRS P=0.03, Figure 1B and 1C, Figure S2). Patients with a LV‐GLS worse than −18%, had a worse prognosis compared to patients with better LV‐GLS. Quartiles of RV‐GLS were not differently associated with outcome (P=0.20, Figure 1D). Patients with LA conduit strain worse than 11% (lowest quartile) had a worse prognosis compared to patients with better LA conduit strain (Log rank for trend P=0.002, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of LVEF, LV‐GLS, LV‐GCS and RV‐GLS.

A, Patients with a LVEF <50% have a worse event‐free survival compared to patients with a LVEF ≥50%; B, Patients with LV GLS worse than −18% have a worse event‐free survival compared to patients with better strain values, based on quartiles; C, Patients with LV GCS worse than 22% have a worse event‐free survival compared to patients with better strain values, based on quartiles; and D, RV GLS is not associated with event‐free survival. EF indicates ejection fraction; GCS, global circumferential strain; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LV, left ventricular; and RV, right ventricular.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of LA strain parameters.

A, LA reservoir strain is associated with event‐free survival; B, LA booster strain is not associated with event‐free survival; C, Patients with LA conduit strain worse than 11% have a worse event‐free survival compared to patients with better conduit strain values, based on quartiles. LA indicates left atrial.

Prognostic Value of Strain Measures to Predict MACE

All LV strain parameters, LA reservoir and LA conduit strain were univariably associated with MACE (included as continuous variables, Table 3). After adjustment for age, sex, and LVEF – which were all univariably associated with outcome ‐ only the LV strain parameters remained significant (LV‐GLS: hazard ratio [HR] 1.07, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.14, P=0.02; LV‐GCS: HR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02–1.29, P=0.02; LV‐GRS: HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96–0.99, P=0.03, Table 4, Table S2), indicating that worse strain values result in higher risk for the occurrence of MACE. RV‐GLS and LA strain parameters were not associated with MACE after adjustment (Table 4). To be noted, LGE presence, extent and septal location were not associated with outcome (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariable Association With MACE

| Variables | All patients (n=162) | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age (y) | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 0.40 (0.19–0.84) | 0.015 |

| STEMI‐like presentation | 1.58 (0.74–3.38) | 0.24 |

| Autoinflammatory disease | 0.44 (0.19–1.03) | 0.06 |

| LVEF (%) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.03 |

| RVEF (%) | 0.99 (0.94–1.03) | 0.52 |

| LGE presence | 2.04 (0.78–5.35) | 0.15 |

| LGE quantification (% of LV mass) | 1.00 (0.92–1.10) | 0.96 |

| Presence of septal LGE | 1.29 (0.60–2.79) | 0.51 |

| Left ventricular GLS (%) | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular GCS (%) | 1.07 (1.02–1.11) | 0.004 |

| Left ventricular GRS (%) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | <0.003 |

| Right ventricular GLS (%) | 1.03 (0.98–1.10) | 0.30 |

| Left atrial reservoir strain (%) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | <0.005 |

| Left atrial booster strain (%) | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 0.18 |

| Left atrial conduit strain (%) | 0.94 (0.89–0.98) | <0.006 |

GCS indicates global circumferential strain; GLS, global longitudinal strain; GRS, global radial strain; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; and STEMI, ST‐elevation myocardial infarction.

Table 4.

Adjusted Model for the Prediction of MACE (Adjusted for Age, Sex, and LVEF)

| Strain parameters | All patients (n=162) | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Left ventricular GLS (%) | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 0.019 |

| Left ventricular GCS (%) | 1.17 (1.04–1.32) | 0.009 |

| Left ventricular GRS (%) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.028 |

| Left atrial reservoir strain (%) | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | 0.73 |

| Left atrial conduit strain (%) | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 0.66 |

Each strain parameter was adjusted for age, sex, and LVEF.

EF indicates ejection fraction; GCS, global circumferential strain; GLS, global longitudinal strain; GRS, global radial strain; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event.

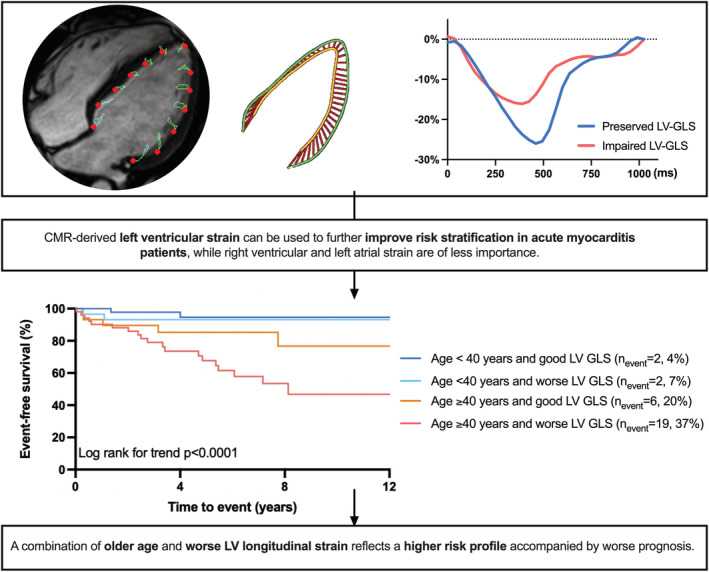

Besides strain, age was the only other independent predictor of outcome in this study population in all models (Table S2). Therefore, we stratified patients into 4 equal subgroups, using the median age of 40 years and the median LV‐GLS value of −22% as cut‐off values (clinical characteristics of the four subgroups are described in Table S5). Patients with older age and worse LV‐GLS had a worse outcome as compared to the other groups (Log rank P<0.001, Figure 3). Patients younger than 40 years, by contrast, tended to have a good prognosis, irrespective of LV‐GLS.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of four risk groups combining age and LV‐GLS.

Good LV‐GLS is defined as LV‐GLS better than −22%, worse LV‐GLS is defined as worse than −22%. Patients that are 40 years or older and have LV‐GLS worse than −22% had a worse outcome as compared to the other groups. Patients younger than 40 years tend to have a good prognosis, irrespective of LV‐GLS. GLS indicates global longitudinal strain; and LV, left ventricular.

Inter‐ and Intraobserver Variability

Interobserver variability was good (LV‐GCS ICC 0.80–0.90) to excellent (LV‐GLS, RV‐GLS, LA reservoir, LA conduit ICC, and LA booster, all ICC ≥0.90) for all strain parameters (Table S6). In addition, intraobserver variability analysis was excellent for all (Table S6).

Discussion

This study evaluated the prognostic impact of CMR myocardial strain analysis of both cardiac ventricles and the LA in acute myocarditis patients. LV strain parameters were independent predictors of MACE in acute myocarditis, even beyond clinical and CMR features such as age, sex, STEMI‐like presentation, LVEF, and LGE. Right ventricular and left atrial strain were not independent predictors of outcome. Patients older than the age of 40 with impaired LV strain had the worst prognosis.

Endomyocardial biopsy is currently the gold standard to diagnose acute myocarditis. 1 However, endomyocardial biopsies are often only performed in tertiary specialized centers and mainly indicated in recurrent or acute myocarditis with progressive or persistent systolic dysfunction. 20 Also, it is limited by small tissue sizes and sampling error. 20 In recent years, CMR has become an important non‐invasive imaging tool for the detection of myocarditis and is described as the non‐invasive gold standard in the Lake Louise Criteria. 2 , 3 , 21 However, these criteria do not provide information regarding the role of CMR in risk stratification of acute myocarditis patients.

CMR feature tracking is a technique that calculates myocardial deformation and detects more subtle and local myocardial dysfunction, even when global EF is normal. 22 Here, CMR feature tracking appears to be an essential feature for risk stratification in acute myocarditis patients. These findings are in line with a first small pilot study of 37 acute myocarditis patients, revealing that CMR‐FT strain parameters are univariable predictors of MACE. 23 The findings from this pilot study were further confirmed by a larger study of 455 myocarditis patients, which showed that LV‐GLS is an independent predictor of prognosis over clinical features, LVEF, and LGE in myocarditis patients. 24 Both studies, however, did not address the prognostic value of RV strain and LA function and had no data regarding long‐term follow‐up. Our data confirm that LV‐GLS is an independent and incremental predictor of long‐term outcome in patients with acute myocarditis.

Biventricular dysfunction is described as a predictor of MACE in ESC guidelines, 1 but data regarding the prognostic value of RV dysfunction or impaired strain in myocarditis are still scarce. RV‐GLS was not associated with outcome in our population, suggesting a limited prognostic role of the RV in acute myocarditis. Interestingly, the prevalence of biventricular dysfunction was relatively low (17%) in this study. Subsequently, most patients had normal RV function and strain. Over the last decade, improvement and increased availability of CMR techniques led to earlier and more frequent diagnosis of acute myocarditis. 3 As a result, less severely ill patients are also being diagnosed with myocarditis, probably explaining the relatively low prevalence of biventricular dysfunction in current myocarditis populations.

Besides ventricular dysfunction, LA‐involvement in myocarditis is an underrepresented phenomenon in the current literature. A study including 30 myocarditis patients revealed impaired LA reservoir and conduit function compared to healthy controls, but its prognostic value was not evaluated. 25 Although LA reservoir and conduit strain predicted MACE in our study population in a univariable analysis, it did not when adjusted for age, male sex, and LVEF. Since CMR was performed shortly after initial presentation, we hypothesize that structural and functional atrial remodeling has not yet occurred. The predictive value of LA strain might become more apparent in a later stage of myocarditis, when diastolic dysfunction or dilated cardiomyopathy may develop.

In our study, LGE presence in the acute phase was not associated with the outcome. This may be because non‐ischemic LGE is one of the major diagnostic criteria for acute myocarditis. Consequently, its prevalence was extremely high (90%) in our study, in line with previous studies. 8 In both ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathies, LGE predicts poor outcome. 26 In the first stage of acute myocarditis, it is hypothesized that LGE also represents patchy distributed cardiac inflammation (edema), which may completely heal over time, 27 besides irreversible fibrosis alone, as is recently pointed out in a meta‐analysis. 8 Here, LGE extent was also not associated with worse outcomes in acute myocarditis. 8 Thus, LGE in the active acute state of myocarditis might be more indicative for myocardial inflammation than end‐stage fibrosis, the latter being associated with worse prognosis.

Clinical Implications

CMR is widely recommended and used in the diagnostic work‐up of patients with suspected myocarditis and feature tracking strain can be easily measured on standard cine images. 2 , 3 , 21 Also, CMR exceeds in accuracy and reproducibility due to high signal‐to‐noise ratio and contrast‐to‐noise ratio compared to echocardiography. 9 In this study, LV strain is a strong predictor of MACE, independent of clinical, and traditional CMR parameters (such as LVEF and LGE presence). Therefore, it is a convenient tool to use in daily clinical practice, and clinicians should consider implementing this in patient management, to better predict which patients develop heart failure or persistent cardiac dysfunction, and to improve patient monitoring. Future studies are needed to validate our findings, to investigate whether the prognostic value of LV‐GLS is influenced by other cardiac markers such as NTproBNP, and to provide optimal software‐independent prognostic cut‐off values.

Study Limitations

Limitations of this study are the lack of availability of EMB and parametric mapping (i.e., T1 or T2 mapping) in most of the patients. However, EMB is not regularly performed in clinical practice and CMR parametric mapping has only been adapted since recent years and therefore long‐term outcome is yet unknown. Four Dutch tertiary centers participated in this retrospective study, introducing a selection or representation bias. However, patients with suspected acute myocarditis are often referred to tertiary, specialized centers for extensive diagnostics and therapy. Moreover, there were no diagnostic codes used to identify patients in the local electronic databases, which might possibly lead to information bias and/or missing data. However, patients were included based on diagnostic criteria from the latest guidelines that are currently applied in clinical practice. Therefore, we believe that this study population represents the general acute myocarditis patient population. We included covariates that are previously described as prognostic markers in acute myocarditis (LVEF, RVEF, sex, age, medical history of autoimmune disease, STEMI‐like presentation, presence of septal LGE, and LGE extent 5 , 6 , 7 ) in the univariable regression analysis, which might introduce a possible bias. The relatively low event rate, however, limits the ability to perform extensive multivariable analysis and the power to detect (more subtle) differences in LA and RV strain in this cohort. Nonetheless, this study is the first to include LA and RV strain parameters, and provides long‐term prognostic information, which is scarce in current literature. To evaluate whether our results are clinically relevant and reproducible besides their statistical significance, external validation in larger, prospective, acute myocarditis studies would be desirable.

Conclusions

CMR‐derived LV strain analysis provides additional prognostic value on top of clinical parameters, LVEF and LGE in acute myocarditis patients, while LA and RV strain do not. A combination of older age and impaired LV longitudinal strain reflects a higher‐risk profile accompanied by worse prognosis.

Sources of Funding

Prof. dr. Nijveldt has received research grants from Biotronik and Philips. Drs. Raafs and prof dr. Heymans have received funding from the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative, an initiative with support of the Dutch Heart Foundation, CVON Arena‐PRIME, 2017–18, and the support of FWO G091018N and FWO G0B593.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S6

Figures S1–S2

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

REFERENCES

- 1. Caforio AL, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, Basso C, Gimeno‐Blanes J, Felix SB, Fu M, Helio T, Heymans S, Jahns R, et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(2636–2648):2648a–2648d. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedrich MG, Sechtem U, Schulz‐Menger J, Holmvang G, Alakija P, Cooper LT, White JA, Abdel‐Aty H, Gutberlet M, Prasad S, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in mjyocarditis: a JACC White paper. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1475–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biesbroek PS, Hirsch A, Zweerink A, van de Ven PM, Beek AM, Groenink M, Windhausen F, Planken RN, van Rossum AC, Nijveldt R. Additional diagnostic value of CMR to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) position statement criteria in a large clinical population of patients with suspected myocarditis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:1397–1407. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jex308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chopra H, Arangalage D, Bouleti C, Zarka S, Fayard F, Chillon S, Laissy JP, Henry‐Feugeas MC, Steg PG, Vahanian A, et al. Prognostic value of the infarct‐ and non‐infarct like patterns and cardiovascular magnetic resonance parameters on long‐term outcome of patients after acute myocarditis. Int J Cardiol. 2016;212:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grani C, Eichhorn C, Biere L, Murthy VL, Agarwal V, Kaneko K, Cuddy S, Aghayev A, Steigner M, Blankstein R, et al. Prognostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance tissue characterization in risk stratifying patients with suspected myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1964–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grun S, Schumm J, Greulich S, Wagner A, Schneider S, Bruder O, Kispert EM, Hill S, Ong P, Klingel K, et al. Long‐term follow‐up of biopsy‐proven viral myocarditis: predictors of mortality and incomplete recovery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1604–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sanguineti F, Garot P, Mana M, O'H‐Ici D, Hovasse T, Unterseeh T, Louvard Y, Troussier X, Morice MC, Garot J. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance predictors of clinical outcome in patients with suspected acute myocarditis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:78. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0185-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Georgiopoulos G, Figliozzi S, Sanguineti F, Aquaro GD, di Bella G, Stamatelopoulos K, Chiribiri A, Garot J, Masci PG, Ismail TF. Prognostic impact of late gadolinium enhancement by cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14:e011492. doi: 10.1161/circimaging.120.011492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pedrizzetti G, Claus P, Kilner PJ, Nagel E. Principles of cardiovascular magnetic resonance feature tracking and echocardiographic speckle tracking for informed clinical use. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:51. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0269-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Verdonschot JAJ, Merken JJ, Brunner‐La Rocca HP, Hazebroek MR, Eurlings C, Thijssen E, Wang P, Weerts J, van Empel V, Schummers G, et al. Value of speckle tracking‐based deformation analysis in screening relatives of patients asymptomatic dilated cardiomyopathy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;13:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Merken J, Brunner‐La Rocca HP, Weerts J, Verdonschot J, Hazebroek M, Schummers G, Schreckenberg M, Lumens J, Heymans S, Knackstedt C. Heart failure with recovered ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1557–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caforio AL, Calabrese F, Angelini A, Tona F, Vinci A, Bottaro S, Ramondo A, Carturan E, Iliceto S, Thiene G, et al. A prospective study of biopsy‐proven myocarditis: prognostic relevance of clinical and aetiopathogenetic features at diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1326–1333. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kindermann I, Barth C, Mahfoud F, Ukena C, Lenski M, Yilmaz A, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Sechtem U, Cooper LT, et al. Update on myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:779–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kindermann I, Kindermann M, Kandolf R, Klingel K, Bultmann B, Muller T, Lindinger A, Bohm M. Predictors of outcome in patients with suspected myocarditis. Circulation. 2008;118:639–648. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.108.769489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Habibi M, Chahal H, Opdahl A, Gjesdal O, Helle‐Valle TM, Heckbert SR, McClelland R, Wu C, Shea S, Hundley G, et al. Association of CMR‐measured LA function with heart failure development. JACC: Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leng S, Tan RS, Zhao X, Allen JC, Koh AS, Zhong L. Validation of a rapid semi‐automated method to assess left atrial longitudinal phasic strains on cine cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance: official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2018;20:71. doi: 10.1186/s12968-018-0496-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Flett AS, Hasleton J, Cook C, Hausenloy D, Quarta G, Ariti C, Muthurangu V, Moon JC. Evaluation of techniques for the quantification of myocardial scar of differing etiology using cardiac magnetic resonance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grigoratos C, Pantano A, Meschisi M, Gaeta R, Ait‐Ali L, Barison A, Todiere G, Festa P, Sinagra G, Aquaro GD. Clinical importance of late gadolinium enhancement at right ventricular insertion points in otherwise normal hearts. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36:913–920. doi: 10.1007/s10554-020-01783-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, Gonzalez‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cooper LT, Baughman KL, Feldman AM, Frustaci A, Jessup M, Kuhl U, Levine GN, Narula J, Starling RC, Towbin J, et al. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;116:2216–2233. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.107.186093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferreira VM, Schulz‐Menger J, Holmvang G, Kramer CM, Carbone I, Sechtem U, Kindermann I, Gutberlet M, Cooper LT, Liu P, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in nonischemic myocardial inflammation: expert recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3158–3176. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Romano S, Judd RM, Kim RJ, Kim HW, Klem I, Heitner JF, Shah DJ, Jue J, White BE, Indorkar R, et al. Feature‐tracking global longitudinal strain predicts death in a multicenter population of patients with ischemic and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy incremental to ejection fraction and late gadolinium enhancement. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:1419–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee JW, Jeong YJ, Lee G, Lee NK, Lee HW, Kim JY, Choi BS, Choo KS. Predictive value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging‐derived myocardial strain for poor outcomes in patients with acute myocarditis. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18:643–654. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2017.18.4.643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fischer K, Obrist SJ, Erne SA, Stark AW, Marggraf M, Kaneko K, Guensch DP, Huber AT, Greulich S, Aghayev A, et al. Feature tracking myocardial strain incrementally improves prognostication in myocarditis beyond traditional CMR imaging features. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:1891–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dick A, Schmidt B, Michels G, Bunck AC, Maintz D, Baeßler B. Left and right atrial feature tracking in acute myocarditis: a feasibility study. Eur J Radiol. 2017;89:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scott PA, Rosengarten JA, Curzen NP, Morgan JM. Late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for the prediction of ventricular tachyarrhythmic events: a meta‐analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1019–1027. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aquaro GD, Ghebru Habtemicael Y, Camastra G, Monti L, Dellegrottaglie S, Moro C, Lanzillo C, Scatteia A, Di Roma M, Pontone G, et al. Prognostic value of repeating cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with acute myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:2439–2448. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S6

Figures S1–S2