Abstract

Background

Black Americans have a disproportionately increased risk of diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease, and higher associated morbidity, mortality, and hospitalization rates than their White peers. Structural racism amplifies these disparities, and negatively impacts self-care including medication adherence, critical to chronic disease management. Systematic evidence of successful interventions to improve medication adherence in Black patients with diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease is lacking. Knowledge of the impact of therapeutic alliance, ie, the unique relationship between patients and providers, which optimizes outcomes especially for minority populations, is unclear. The role and application of behavioral theories in successful development of medication adherence interventions specific to this context also remains unclear.

Objective

To evaluate the existing evidence on the salience of a therapeutic alliance in effective interventions to improve medication adherence in Black patients with diabetes, hypertension, or kidney disease.

Data Sources

Medline (via PubMed), EMBASE (OvidSP), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCOhost), and PsycINFO (ProQuest) databases.

Review Methods

Only randomized clinical trials and pre/post intervention studies published in English between 2009 and 2022 with a proportion of Black patients greater than 25% were included. Narrative synthesis was done.

Results

Eleven intervention studies met the study criteria and eight of those studies had all-Black samples. Medication adherence outcome measures were heterogenous. Five out of six studies which effectively improved medication adherence, incorporated therapeutic alliance. Seven studies informed by behavioral theories led to significant improvement in medication adherence.

Discussion/Conclusion

Study findings suggest that therapeutic alliance-based interventions are effective in improving medication adherence in Black patients with diabetes and hypertension. Further research to test the efficacy of therapeutic alliance-based interventions to improve medication adherence in Black patients should ideally incorporate cultural adaptation, theoretical framework, face-to-face delivery mode, and convenient locations.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, medication adherence, African Americans

Introduction

Black Americans suffer from a higher burden of diabetes,1,2 hypertension,4 and kidney disease than their White counterparts.3,4 Compared to White Americans, Black Americans in the United States have a 1.6-fold higher risk of diagnosed diabetes and a 2-fold higher risk of death from diabetes,5 a 1.4-fold higher risk of hypertension,6 and a 4-fold higher prevalence of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).7 In addition to an increased burden of these chronic conditions, Black Americans experience worse clinical outcomes associated with these conditions including a 2.3-fold higher likelihood of hospitalization for lower limb amputations, 1.3-fold higher risk of visual impairment secondary to diabetes, 3-fold higher risk of hospitalizations from uncontrolled diabetes without complications,5 and a 1.3-fold higher risk of death from heart disease, compared to their White peers.6 Further, Black American veterans with moderate kidney disease have approximately 3-fold faster rate of progression to ESKD4 and a 1.3-fold higher mortality risk compared to their White peers.8 This disparity in clinical outcomes is due in part to greater barriers to self-management of diabetes,9 hypertension10 and kidney disease among the Black Americans, including poor medication adherence, which are all intertwined with structural racism.11

In general, medication adherence is very complex. This is in part related to the broad spectrum of, and absence of standard terminologies used to describe adherence. Examples of such terminologies include compliance, persistence, and discontinuation.12 A vast array of factors are associated with medication adherence including condition-related factors, patient-related factors, therapy-related factors, health system-related factors, social determinants of health13,14 psychosocial factors,15 provider-related factors16 and others that add to the complexity. Distinct racial disparities in these factors are well documented and Black Americans are disproportionately burdened with these factors.15 The concept of medication adherence is further complicated by the multiplicity of measurement methods in existence.12 Medication adherence assessment methods can be classified as subjective (ie patients’ self-reported adherence behavior) or objective (ie measurement of dose counts, pharmacy records, electronic monitoring of medication use and clinical outcomes).12 Medication adherence assessment methods also include direct and indirect methods of assessment. These include direct observation of therapy, measurement of drug/metabolite or biological marker levels versus patients’ questionnaires, patients’ diaries, pill counts, prescription refills, electronic medication monitors, respectively, as well as assessing consequences of therapy such as measurement of physiologic markers and assessment of patients’ clinical response.12

Poor medication adherence has been directly linked to increased risk of stroke from hypertension,17 increased morbidity and mortality from hypertension,17 diabetes18 and kidney disease,19 and greater healthcare cost.18 Black patients report lower rates of medication adherence than White patients,20 and given that medication adherence is a modifiable behavior,11 it is an important target for interventions to reduce persistent racial disparities in these chronic cardiometabolic conditions. There is, however, a gap in knowledge identifying and confirming effective interventions to improve medication adherence in Black patients with diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease.

Factors affecting medication adherence include patient and relationship-related factors, especially therapeutic alliance.21 Therapeutic alliance or “collaborative bond” between patients and providers is a key component of successful interventions targeting improvement in medication adherence.21 It is especially important in interventions designed for Black patients and others who have reported a lower perception of their providers’ support of autonomy in self-care.22 Therapeutic alliance recognizes patient’s individual background, beliefs, and lifestyle, and adapts treatment plans to satisfy unique socio-cultural needs of diverse patients.23 To our knowledge, no report to date focuses on describing therapeutic-alliance-based interventions to improve medication adherence in Black patients with diabetes, hypertension, or kidney disease.

This systematic review aims to evaluate the existing evidence on the salience of a therapeutic alliance for the development of effective interventions to improve medication adherence in Black patients with diabetes, hypertension, or kidney disease. Interventions designed to change health behavior are more likely to be effective when they are informed by behavioral theory.24 These include interventions designed to improve medication adherence in chronic illness.24–26 In addition to characterizing the role of therapeutic alliance in interventions to improve medication adherence in Black patients with diabetes, hypertension, or kidney disease, this systematic review also highlights the use of behavioral theories to inform the intervention.

Research Design and Methods

Guided by the tenets of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist, we conducted a Systematic Review based on definitions used by the Cochrane Collaboration.27 It was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (Registration number – CRD42020148049).

Study Eligibility Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they were randomized clinical trials or pre-post intervention studies of interventions to improve medication adherence in kidney disease, diabetes, or hypertension. The search was limited to articles published between January 2009 and May 2022 (the initial search covered articles published between 2009 and December 2020 while an updated search covered articles published between January 2021 and May 2022). Studies were eligible if they were published in English, reported a medication adherence outcome, were conducted in adults older than 18 years, and included a minimum of 25% “Black” or “African American” participants.

Search Strategy/Source

Electronic database searches were performed by a Health Sciences Information expert (HL). Electronic databases included Medline (via PubMed), EMBASE (OvidSP), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCOhost), and PsycINFO (ProQuest). Standard underlying index terms and alternative variations of Medline MeSH terms were used including “Minority Health” or “African Americans” or “Black” or “Race Factors” and “Diabetes Mellitus” or “Hypertension” or “Kidney Failure, Chronic” or “Renal Insufficiency, Chronic” or “Renal Dialysis” and “Therapeutic Alliance” or “Motivational Interviewing” or “Social Support” or “Directive Counseling” or “Patient Care Team” or “Patient Care Management” or “Self Management” and “Medication adherence” or “Hypoglycemic agents” or “Antihypertensive Agents” and “Medication adherence” (see Supplemental Material). Titles were screened to remove duplicate papers. Guided by the inclusion criteria, independent review of titles and abstracts was done by two independent reviewers (RD, CB) who identified articles for inclusion in the final review. Any disagreements were resolved through discussions involving all co-authors until consensus was reached. References of included articles were searched to identify any papers which may have been omitted by the database searches.

Data Extraction

Study authors developed a standard data extraction form which was used to document pertinent information from the selected studies. It included study title, authors, journal and publication year, study design, primary clinical condition, co-morbidities, sample size, proportion of patients with kidney disease, study duration, intervention type, intervention dose, underlying health behavioral theory, incorporation of therapeutic alliance, medication adherence measure, medication adherence as primary outcome, results, and significant improvement. Incorporation of therapeutic alliance was documented for studies which included components of therapeutic alliance even if not explicitly described as such. One author (RD) documented this information while a second author (CB) reviewed the papers and confirmed the accuracy of the documentation in the extraction form. Any differences were reviewed and resolved by all co-authors.

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

A modified version of Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2.0) tool28,29 was used by the authors for assessment of bias in included randomized control trials. Similarly, a modified version of the Cochrane Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool29,30 was used for assessment of bias in pre-post interventions (see Supplemental Material). Two authors (RD, CBP) independently assigned risk of bias scores to the included studies, and a third author (EU) verified that scores matched.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Data synthesis and analysis was descriptive, performed in accordance with published guidance,27 and involved detailed description of all included studies using the described data extraction criteria. Given the expected heterogeneity in measures of medication adherence, a narrative synthesis was used to summarize the outcomes of included interventions, the existence and details of therapeutic alliance, and the inclusion of underlying behavioral theories. Description of emerging patterns, as well as strengths and limitations of this systematic review, was included.

Results

Search Results

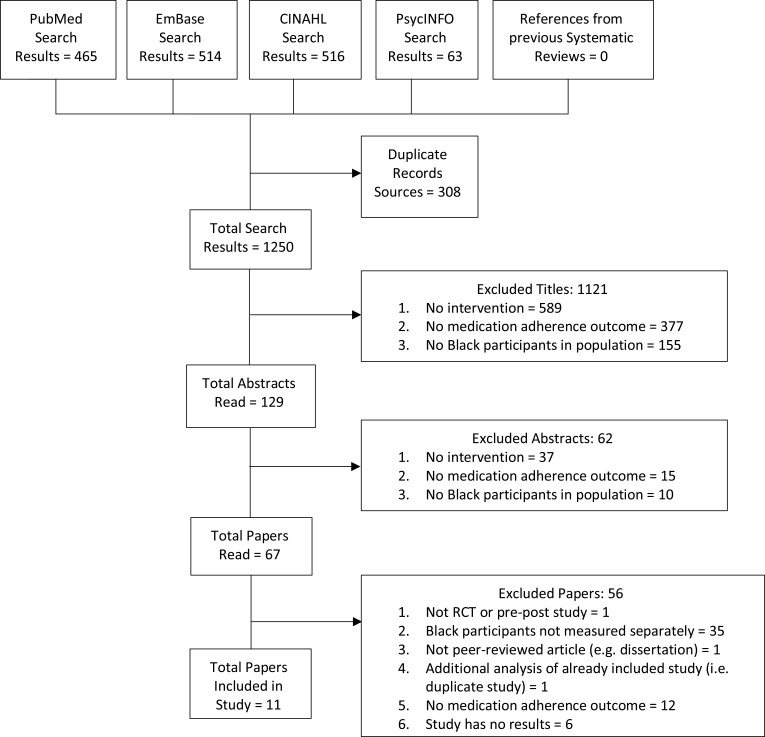

The search yielded 1558 results. Additional hand search of references from related systematic reviews yielded no additional results. Duplicate records (n = 308) were excluded resulting in 1250 citations out of which 1121 titles were excluded. A total of 129 abstracts were selected and read based on a review of the titles using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 67 papers were deemed eligible for further review, out of which 11 papers fully met all the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The main reasons for excluding the other papers were failure to include medication adherence as an outcome, failure to report study results by race or unavailability of study results (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing initial search results (2009–2020).

Study Design and Characteristics

Duration of Interventions ranged from 6 weeks to 18 months. Each study had measurements at baseline and at the end of the intervention except for two of the studies with post-intervention measurements done 6 months after the intervention conclusion. Ten of the selected studies were randomized control trials (RCT) or cluster randomized trials,31–40 while the remaining study was a pre-post study.41 One of the studies was conducted in an academic medical center31 while the others were conducted in various non-academic locations including a local church in Southeastern United States,41 a primary care office in West Philadelphia,32 a Pharmacy in Wisconsin,38 a community health center in New Jersey,39 an Emergency Department in Washington, DC34 and a safety net primary care clinic in New York City.40 All but two studies had an all-Black / African American patient population, with the remaining two studies34,39 having over 95% of the participants identify as Black/African American. One of the studies was restricted to African American women.31 Selected studies had a sample size ranging from 12 to 1039. Almost half of the studies focused on medication adherence specific to diabetes31–34,41 or hypertension.35–39 while one of the studies targeted medication adherence in the context of both diabetes and hypertension.40 None of the studies exclusively targeted improvement in medication adherence in kidney disease. Three of the studies excluded patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or ESKD;31,33,38 while two of the studies included 2.5%37 and 3.5%36 of patients with CKD or ESKD, respectively. Information related to CKD or ESKD was either unknown or non-applicable to the other studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Title | A Culturally Targeted Self-Management Program for African Americans with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | A Virtual World Verses Face-to-Face Intervention Format to Promote Diabetes Self-Management Among African American Women: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial | Integrating Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Depression Treatment Among African Americans | Randomized Trial of a Lifestyle Intervention for Urban Low-Income African Americans with Type 2 Diabetes | The Synergy to Enable Glycemic Control Following Emergency Department Discharge Program for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: Step-Diabetes | A Culturally Adapted Telecom System to Improve Physical Activity, Diet Quality and Medication Adherence Among Hypertensive African-Americans: A Randomized Control Trial | A Randomized Controlled Trial of Positive-Affect Intervention and Medication Adherence in Hypertensive African Americans | Counseling African Americans to Control HTN | Improving Refill Adherence and HTN Control in Black Patients: Wisconsin TEAM Trial | Utilizing a Mobile Health Intervention to Manage HTN in an Underserved Community | Development and Evaluation of a Tailored Mobile Health Intervention to Improve Medication Adherence in Black Patients With Uncontrolled Hypertension and Type 2 Diabetes: Pilot Randomized Feasibility Trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Collins-McNeil et al (2012)41 | Rosal et al (2014)31 | Bogner et al (2010)32 | Lynch et al (2019)33 | Magee et al (2015)34 | Migneault et al (2012)35 | Ogedegbe et al (2012)36 | Ogedegbe et al (2012)37 | Svarstad et al (2013)38 | Zha et al (2019)39 | Schoenthaler et al (2020)40 |

| Study Design | Pre/Post | 2 arm RCT | RCT | Single Blind RCT | RCT | 2 arm RCT | 2 arm RCT | 2 -arm Cluster RCT | Cluster Randomized Trial | RCT | RCT |

| Condition Addressed | Diabetes | Diabetes | Diabetes | Diabetes | Diabetes | HTN | HTN | HTN | HTN | HTN | HTN DM |

| Setting | Southeastern US, Church | Massachusetts, Boston Medical Center, Online/Clinic | West Philadelphia, Primary Care Office | Cook County, IL, Clinic/Phone | Emergency Department | Telephone | New York City, NY, Telephone | New York City, NY | Wisconsin, Pharmacies | Rutgers, NJ, Community Health Center | Primary Care Clinic in New York |

| Inclusion Criteria | Self-identify as African American, diagnosis of T2DM, written/verbal comprehension, consent | African American Women (identified from EMR), T2DM, age >18 years, English-speaking, HbA1c > 8% | AA, Age >50, A1C >7 or Rx Hypoglycemic Agent, Dx Depression or Rx Antidepressant | AA, Age >18, Uncontrolled T2DM (A1c >7.0%), seen in past 12 months at CCHHS primary care clinic, available for sessions | ED Visit (any reason), T2DM, Age >18 years, Able to check BG | African American (self-report), Dx HTN, current rx for anti-hypertensive medication, 1 office visit in past 12 mo., 2 elevated clinical BP reading in past 2 mo., and Age >35 years Excluded: if MMAS-7 was 7 out of 7 | AA/Black (Self-identify), English speaker, dx of HTN, and 1 antihypertensive medication | AA/Black (Self-identify), care at CHC location, uncontrolled HTN, English speaker | Black (Self-identify), Age >18 years, receive rx at Walgreens or aurora pharmacy, mean BP > 140/90, able to read, able to return for 6 visits | Age 18–64 years, resided in public housing unit, dx with uncontrolled HTN (BP 140/90 5 separate times in 2 mo.), taking anti-hypertensive medication, owned/used compatible mobile device, and read/speak English | Self-identified as Black; ≥ 18 years; English-speaking; no psychiatric comorbidity; received care at the primary care clinic; uncontrolled HTN (BP>140/90nor >130/80 with DM or kidney disease; and/or uncontrolled T2D with HbA1c on ≥ 2 visits in the past 1 year + 1 CV risk factor; non-adherent to anti-HTN or anti-DM med |

| Co-Morbidities | N/A | N/A | Depression: 100% | Heart Disease: 4.7% Hypertension: 91% |

HTN: 58.4% Heart Disease: 13.9% Microvascular Complications (retinopathy, neuropathy and kidney disease): 31.7% Other: 46.5% |

Diabetes: 38.3% Stroke: 7.7% | Renal Disease: 3.5% Diabetes: | Diabetes: 36.3% Stroke: 12/5% Congestive | Diabetes: 24.7% | N/A | Diabetes 72.1% Stroke 14% |

| % Black | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 96 | 100 |

| Intervention Sample | 12 | 89 | 58 | 196 | 101 | 169 | 256 | 1039 | 576 | 25 | 21 |

| % with CKD/ESRD | N/A | Excluded | N/A | Excluded | Unknown | N/A | 3.50% | 2.50% | Excluded | N/A | 4.70% |

| Intervention | Church based DSME | CDC/NIH “Power to Prevent” program | Integrated care manager collaborated with physician | Lifestyle Improvement through Food and Exercise (LIFE): culturally tailored DSME | ED DSME Survival Skills | Automated Telephone Linked Care for HTN in AA | Patient Education Enhanced by Positive Affect Induction and Self Affirmation | Multilevel Intervention | Pharmacist TEAM intervention | Mobile Health Intervention | Tailored Mobile Health Intervention |

| Intervention Theory | N/A | Social Cognitive Theory | Integrated Care | N/A | Integrated Care | Social Cognitive Theory Trans-theoretical Model of Behavioral Change Motivational Interviewing | Social Cognitive Theory | Chronic Care Model | Health Collaboration Model | N/A | Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills (IMB) |

| Dosing | 1 session/week for 2hrs over 6 weeks. Practice self-management behaviors for additional 6 weeks. |

1st session individual, 90 min 8 weekly group session, 90 min |

(3) 30 min in-person sessions (2) 15 min telephone monitoring contacts Over 4-week period |

28 group sessions over 12 mo. Weekly for first 4 mo. Biweekly for second 4 mo. Monthly for the third 4 mo. |

Intervention visits were at 24 to 72 hrs., 2, and 4 wks. 90-day phone call | 1 call per week for 32 weeks 3 calls introduced targeted behavior and role in BP control 12 calls targeting physical activity 9 calls targeting DASH diet 8 calls targeting medication adherence |

Control: Educational Workbook and Bi-monthly telephone calls to assess confidence Intervention: Educational Workbook + Bi-monthly calls, + 2 Positive Affirmations per call |

4 modules targeting pt. education 6 behavioral lifestyle counseling sessions 1 Free BP Monitor (suggested take 2x daily/3x a week) |

6 pharmacist visits with Brief Medication Questionnaire forms (assess barriers targeted in trial) Take-home toolkit (BP recording card, 7-day medication box, pedometer to enforce lifestyle change) | iHealth BP7 Wireless Blood Pressure Wrist Monitor | One-time completion of tailoring survey based on IMB adherence questionnaire, individualizing adherence profile, and a personalized list of interactive adherence-promoting modules |

| Control vs Experimental | N/A | Control: Face-to-Face Curriculum Intervention: Virtual World Curriculum | Control: Usual Care Intervention: Integrated Care Manager | Control: Standard Care (2 DMSE in 6 mo.) Intervention: LIFE Approach | Control: Usual ED Care Intervention: DSME Survival Skills | Control: Usual Care Intervention: Telephone Linked Care | Control: Patient EducationIntervention: Patient Education + Positive Affirmation | Control: Usual Care | Control: Patient Information Booklet | Control: Standard Care | Control: Active Control Group: Completion of tailoring survey + completion of unrelated health education modules |

| Study Duration | 12 weeks | 4 months | 6 weeks | 18 months | 12 weeks | 12 months | 12 months | 12 months | 12 months | 6 months | 3 months |

| Results | Pre: n (9), 50–100% Adherence Post: n (10), 50–100% Adherence | Control: −8.6% Adherence Change Intervention: +1.2% Adherence Change | Control (>80% adherent to oral anti-DM n (%)): 24.1% Intervention (>80% adherent to oral anti-DM, n (%)): 62.1% | Medication Adherence, n (%) Low to high (C @12m) 24.0 (I @12m) 10.1 (C @18m) 21.1 (I @18m) 14.4 Stayed the same (C @12m) 61.0 (I @12m) 74.8 (C @18m) 65.3 (I @18m) 67.0 High to low (C @12m) 15.0 (I @12m) 15.2 (C @18m) 13.7 (I @18m)18.6 |

Subjects in low adherence category (MMAS >2), n (%) (C @ Baseline) 45% (I @ Baseline) 60% (C @ Week 4) 53% (I @ Week 4) 35% | Within-Group Chang Scores from Baseline to End of Intervention Control: +0.26 Intervention: +0.45 | Control: 36% Adherence Intervention 42% Adherence | Mean of MMAS-4 Baseline, 6mo, 12 mo. Control: 1.18, 1.05, 0.98 Intervention: 1.01, 0.87, 0.77 | (C @ 6mo) (I @ 6mo) 34% 60% (C @ 12mo) (I @ 12mo) 44% 62% |

(C @ Baseline) (I @ Baseline) 64.75 64.85 (C @ 6mo) (I @ 6mo) 61 69.17 |

Both groups showed significant improvements in adherence (mean 1.35, DD 1.60; P<0.001) and SBP (−4.76mmHg; P = 0.04) with no between-group differences (P=0.50 and P=0.10) No significant differences in DBP and HBA1c |

Abbreviations: RCT, randomized clinical trial; HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; BP, blood pressure; CV, cardiovascular; DSM, diabetes self-management education.

Risk of Bias

The overall risk of bias was judged to be either “medium risk” or “low risk” for the included studies (see Supplemental Box 1). Using the modified version of the RoB 2.0 tool, seven of the RCTs were “low risk” while the remaining three were “medium risk”. The pre-post study was found to be “low risk” using the modified version of the ROBINS-I tool. The most common risk of bias was from blinding and loss of data for the RCTs, and bias in measurement of exposures and outcomes, or bias due to deviations from interventions in the pre-post study (See Table 2 and Supplemental Material).

Table 2.

Risk of Bias

| Author | Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Blinding | Completion of Outcome Data | Similarity of Groups at Baseline | Loss of Data | Total Points | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosal et al (2014)31 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | Med |

| Bogner et a (2010)32 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Low |

| Lynch et a (2019)33 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Low |

| Magee et a (2015)34 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Med |

| Migneault et al (2012)35 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Low |

| Ogedegbe et a (2012)36 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Low |

| Ogedegbe et a (2012)37 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | Med |

| Svarstad et a (2013)38 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Low |

| Zha et a (2019)39 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Low |

| Schoenthaler et al (2020)40 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Low |

| Author | Baseline Confounding | Selection Bias | Bias in Measurement of Exposures and Outcomes | Bias due to Deviations from Intended Interventions | Selective Reporting of Analyses or Outcomes | Bias due to Missing Data | Total Points | Risk Level |

| Collins McNeil et al (2012)41 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Low |

Interventions

The interventions addressing improvement in medication adherence in diabetes were mostly culturally tailored meaning that they were designed to both address medication beliefs and match patients’ needs and preferences.40 These culturally tailored interventions varied in the location, mode of delivery (group-based versus individual or virtual versus face-to-face), and content. For instance, culturally targeted diabetes self-management education (DSME), was delivered as a church-based group intervention which included stress management, coping skills and physical activity41 in one study. In contrast, culturally appropriate curriculum was initially delivered in an individual session with subsequent follow-up group sessions, delivered in a community setting and augmented with peer supporter phone calls.33 Yet another study integrated culturally tailored individualized educational programming delivered in a primary care provider’s office to improve medication adherence to oral hypoglycemic agents and antidepressants for concurrent management of diabetes and depression,32 while another study focused on the delivery of culturally tailored intervention through virtual versus face-to-face format.31 The sessions focused on optimizing self-efficacy, outcome expectations and behavioral self-management skills such as goal setting, tracking self-management behaviors and glucose level, and problem solving.31 Informed by a preceding formative phase consisting of qualitative interviews to tailor the intervention to the needs of the target population, another study used a tailored mobile health intervention.40 This consisted of a tablet-delivered tailoring survey, an individualized adherence profile, and a personalized list of interactive adherence-promoting modules including informational, motivational, and behavioral strategies.40 Lastly, a different study which was not culturally tailored, centered on the integration of delivery of concise, provider-delivered DSME in the emergency room with timely titration of antihyperglycemic agents using an evidence-based algorithm.34

Cultural tailoring of interventions was less commonly done in the studies targeting medication adherence improvement in the context of hypertension, and only two out of the five studies included a culturally tailored multi-behavior intervention delivered in an individualized and automated format35,40 with one of those two studies being the one study which simultaneously targeted improvement in medication adherence in diabetes and hypertension.40 A couple of the studies prioritized patient education either in combination with behavioral lifestyle telephone/group counseling sessions delivered in an interactive, computerized format,37 or integrated with positive-affect induction and self-affirmation.36 Other studies were centered on monitoring and sharing of blood pressure data either through mobile health technology39 or use of self-reported surveys paired with toolkits which incorporate checklist for documenting and tracking barriers, with simple algorithms for addressing barriers, and structured process for providing feedback to physicians.38

Six interventions were delivered either through a tablet,40 virtual online platform,31 mobile app,39 culturally adapted automated phone calls,35 phone calls enhanced with positive affirmations,36 and behavioral group counseling phone calls.37 The remaining five studies included a face-to-face intervention component.32–34,38,41 Additional details of the intervention type, frequency and duration are provided in Table 1.

Health Behavior Theories and Therapeutic Alliance

Interventions grounded in behavioral theory were tested in 8 of 11 studies. Three of these studies applied social cognitive theory,31,35,36 while two of them were rooted in integrated care.32,34 Other theoretical models noted in the selected studies include the transtheoretical model of behavior change,35 chronic care model,37 information-motivation-behavioral skills model40 and health collaboration model.38 All except three of the studies35,36,40 incorporated various forms of therapeutic alliance. Details of the health behavior theories and inclusion of therapeutic alliance are provided in Tables 1 and 3.

Table 3.

Study Outcome

| Study | Authors | Adherence Measure | Therapeutic Alliance | Favorability | Significance (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Culturally Targeted Self-Management Program for African Americans with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Collins-McNeil et al (2012)41 | Diabetes Self-Care Practices Measurement Questionnaire (DSCPM) | Yes | Post-Intervention | Yes |

| A Virtual World Verses Face-to-Face Intervention Format to Promote Diabetes Self-Management Among African American Women: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial | Rosal et al (2014)31 | Self-reported 24-hour recall | Yes | Intervention (Virtual World) | No |

| Integrating Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Depression Treatment Among African Americans | Bogner et al (2010)32 | Medication Event Monitoring System Caps | Yes | Intervention | Yes |

| Randomized Trial of a Lifestyle Intervention for Urban Low-Income African Americans with Type 2 Diabetes | Lynch et al (2019)33 | MMAS-8 Questionnaire | Yes | Control | Yes |

| The Synergy to Enable Glycemic Control Following Emergency Department Discharge Program for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: Step-Diabetes | Magee et al (2015)34 | MMAS-8 Questionnaire | Yes | Intervention | Yes |

| A Culturally Adapted Telecom System to Improve Physical Activity, Diet Quality and Medication Adherence Among Hypertensive African Americans: A Randomized Control Trial | Migneault et al (2012)35 | 7 item-version of MMAS-8 | No | Intervention | No |

| A Randomized Controlled Trial of Positive-Affect Intervention and Medication Adherence in Hypertensive African Americans | Ogedegbe et al (2012)36 | Electronic pill monitors, proportion medication doses | No | Intervention | Yes |

| Counseling African Americans to Control HTN | Ogedegbe et al (2012)37 | MMAS-4 Questionnaire | Yes | Intervention | No |

| Improving refill adherence and HTN control in black patients: Wisconsin TEAM trial | Svarstad et al (2013)38 | % of patients with good refill adherence (80% PDC) | Yes | Intervention | Yes |

| Utilizing a Mobile Health Intervention to Manage HTN in an Underserved Community | Zha et al (2019)39 | Medication Adherence Self-Efficacy Scale | Yes | Intervention | No |

| Development and Evaluation of a Tailored Mobile Health Intervention to Improve Medication Adherence in Black Patients with Uncontrolled Hypertension and Type 2 Diabetes: Pilot Randomized Feasibility Trial | Schoenthaler et al (2020)40 | MMAS-8 Questionnaire | No | Intervention | No |

Abbreviations: MMAS, Morisky Medication Adherence Scale; PDC, prescription days covered.

Outcome Assessment

Medication adherence outcome measures were heterogenous across the studies. Three of the studies used objective adherence measurement methods including the medication event monitoring system caps,32 electronic pill monitors36 and refill adherence data review.38 The remaining eight studies used patient-reported outcome measures such as 24-hour recall31 or self-reported medication adherence scales.33–35,37,39–41 Improvement in medication adherence was the primary outcome in six of the studies. Two of the studies had a diabetes-specific focus,32,41 while four of the six studies had a primary outcome of improvement in medication adherence in the management of hypertension.35,36,38,39

Outcome Efficacy

More than half of the studies were effective in improving at least one of the medication outcomes measures.32–34,36,38,41,42 The remaining studies did not demonstrate statistically significant improvement in medication adherence.31,35,37,39,40 Four out of the five diabetes-specific studies showed significant improvement in medication adherence;32–34,41 however, only two out of the five hypertension-specific studies demonstrated significant improvement in medication adherence.36,38 Three out of the four interventions which were delivered either through a virtual online platform,31 mobile app,39 tablet40 or phone calls37 did not show significant improvement in medication adherence. Of the six studies that demonstrated significant medication adherence improvement, five of them included a face-to-face intervention component,32–34,38,41 while the intervention in the remaining study included calls enhanced with positive affirmations.36 Therapeutic alliance was incorporated in five out of the six studies that demonstrated significant improvement in medication adherence.32–34,38,41 Two studies which were informed by the integrated care model were successful at improving medication adherence.32,34 See Table 3 for details of outcome assessment and efficacy.

Discussion

There is a limited number of available studies focused on interventions to improve medication adherence among Black patients, which exposes an unmet need in chronic disease management. Almost all the studies that demonstrated statistically significant improvement in medication adherence involved face-to-face interactions and incorporated therapeutic alliance.32–34,38,41 Interventions informed by theoretical models grounded in therapeutic alliance such as the integrated care model32,34 and the health collaboration model38 were successful at improving medication adherence. Limited available data shows that contrary to the outcomes of the majority of the hypertension-focused studies, most of the diabetes-focused studies led to improvement in medication adherence.32–34,41 Despite its association with increased morbidity and mortality, we found very limited published studies measuring improvement in medication adherence in Black patients and almost no studies include patients with CKD or ESKD.36,37

There is a critical need to address the gap in knowledge of interventions to improve medication adherence among Black patients by designing studies with cohorts dedicated to Black participants, or including a representative sample of Black study participants; reporting results by race; and using interventions which incorporate therapeutic alliance. Most of the studies included in this systematic review incorporated therapeutic alliance and almost all the studies which demonstrated significant improvement in medication adherence, involved a therapeutic relationship between patients and providers, which may be particularly important in Black patients who tend to have a higher degree of medical mistrust.43 Effective behavior change interventions are contingent upon the development of a shared understanding of the behavioral problem, agreement on the management plan and tasks, and development of a collaborative bond between the patient and provider ie, therapeutic alliance. Weak therapeutic alliance and poor insight are associated with poor medication adherence,21 and conversely, strong therapeutic alliance facilitates patient activation,44 which in turn is useful for addressing racial and ethnic disparities in health.45 Therapeutic alliance is a core component of adherence studies in Black Americans,29 and it should be an integral part of studies targeting improvement in medication adherence in Black patients.

Compared to those without, interventions with a face-to-face component resulted in significant improvement in medication adherence in this systematic review of Black patients. The one study which did not include face-to-face interactions but resulted in significant improvement in medication adherence, included calls enhanced with positive affect/thoughts.36 Therefore, integrating therapeutic alliance, into non-face to face or virtual interactions, may be a key consideration for optimizing success when designing medication adherence behavior change interventions for Black patients.46 The success of medication adherence interventions for Black patients with diabetes has been limited by access and socioeconomic barriers, distrust of the healthcare system, and lack of cultural tailoring of interventions. Most of the studies in this review which focused on therapeutic alliance, occurred in a variety of locations outside of the traditional medical office visit location, and likely more convenient for the patients including a local church,41 a pharmacy,38 a community health center,39 and an Emergency Department.34 These studies addressed patients’ access to barriers, and facilitated their trust in the intervention, in part by prioritizing choice of locations. The benefits of therapeutic alliance in addressing medication adherence in Black patients, can be further enhanced by cultural adaptation of interventions.47 For instance, Black patients may have unique perceptions of management of hypertension which need to be recognized and addressed such as, the notion that hypertension can be controlled with pickle juice or managed with “cultural treatments”, passed down from one generation to another.48

Intervention development was informed by behavioral theories in most of the included studies. The integrated care model or health collaboration model is a combination of behavioral and primary health care, which enhances therapeutic alliance by ensuring shared understanding among all team members to further deepen the relationship between patients and their providers. The three studies informed by the integrated care model,32,34 or the health collaboration model resulted in improved medication adherence.38 While no conclusions can be drawn from this observation, it is important to note that the integrated care model or health collaboration method is centered on patient-centered, evidence-based team care, which integrates the fundamental components of therapeutic alliance. One of the studies40 was informed by the information-motivation-behavioral (IMB) skills model49 which posits that medication adherence depends on an individual’s level of regimen-specific-information, motivation to adhere, and behavioral skills. The study40 did not demonstrate any statistically significant improvement in medication adherence although IMB has been successfully applied to predict and identify intervenable determinants of diabetes medication adherence.50 A couple of the studies were informed by the social cognitive theory, which is a theoretical paradigm based on the assumption that expectations, thoughts, and beliefs are shaped by one’s social environment and influence behavior. Not much inference can be made from the observation that two31,35 out of the three studies informed by the social cognitive theory did not demonstrate any improvement in medication adherence. However, it is worthwhile to note that social cognitive theory has been found to be “weakly predictive” of medication adherence in depression, and likely needs to be bolstered by therapeutic-alliance-based theories such as the integrative model.51 This underscores the importance of therapeutic alliance in the development of successful medication adherence interventions.

The success rate of most diabetes-focused interventions in this systematic review exceeds that of the hypertension-focused studies. While this could reflect some publication bias, existing literature52 identifies hypertension as an independent predictor of non-adherence.52 Patients with hypertension reportedly tend to be less committed to their prescribed therapy than those with diabetes due to the asymptomatic nature of hypertension, a lack of appreciation of the connection between any emerging symptoms related to the diagnosis of hypertension, and difficulty in visualizing long-term consequences.53 The lack of awareness of the need for life-long treatment is highlighted as an additional reason for lower medication adherence rates in hypertension.52 Targeted efforts to study and intervene upon medication adherence in Black patients with hypertension is of utmost importance given the prevalence of more severe and resistant hypertension in Black patients,54 and lower hypertension control rates in Black adults compared to White adults in part due to variable medication adherence.55 Interventions to mitigate these disparities in hypertension would likely be more successful with use of therapeutic alliance-based and culturally tailored strategies, including face-to-face delivery mode, convenient and trusted locations, and tailored communication to improve medication adherence in Black patients with hypertension.56 Future studies targeting improvement in medication adherence in hypertension should prioritize such approaches.

In this systematic review, a limited proportion of studies (27%) used objective measures of medication adherence and these studies demonstrated improvement in medication adherence in this patient population. The rest of the studies used self-report patient outcome measures (24-hour recall or medication adherence scales) which are considered subjective. Perhaps, these subjective measures may be more popular due to logistics and study constraints. However, it has been recently highlighted that due to the inherent advantages and disadvantages of subjective and objective methods of medication adherence measurement, a combination of at least two of those methods is recommended.12

The higher prevalence of ESKD in the Black community7 and existing racial disparities in medication adherence in kidney disease57 emphasize the need for future studies to target higher rates of enrollment of Black patients with kidney disease. This will allow us to better study and intervene upon medication adherence in this patient population living with multiple comorbid conditions.

Strengths

This systematic review addresses a gap in existing knowledge on medication adherence in Black patients with diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease. The strengths of this systematic review include its scientific rigor, advanced methods to evaluate for bias, and unique study criteria especially the assessment of inclusion of therapeutic alliance and incorporation of theoretical frameworks in the design of medication adherence interventions. Study findings highlight several effective interventions in this patient population and emphasize the need for integration of therapeutic alliance in medication adherence interventions.

Limitations

The 25% cut-off for proportion of Black participants in studies included in this Systematic Review was somewhat arbitrary, and it was based on the notion that it reflected enough Black representation in the sample to inspire confidence that findings could be extrapolated to the population of interest. However, despite this modest cut-off, this systematic review highlights the limited number of studies targeting improvement in medication adherence in Black patients despite the justifiable need in this area. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of measures of adherence and outcomes in these studies, which increases the risk that any observed improvement in medication adherence could be attributed to chance. This heterogeneity also limits the ability to draw quantitative conclusions about improvement in medication adherence across the studies, hence, this Systematic Review leverages the use of narrative synthesis to provide a comprehensive description of the interventions, outcomes, existence and details of therapeutic alliance and theoretical paradigms; and inform hypothesis generation.

Conclusion

First, the findings of this systematic review suggest that interventions designed to improve medication adherence in Black patients with diabetes and hypertension, are likely strengthened when grounded in the principles of therapeutic alliance. Interventions informed by theoretical frameworks such as the integrated care model which incorporate therapeutic alliance, are further strengthened by the development of a strong patient-provider “collaborative bond”, which optimizes outcomes, especially in minority populations including Black patients. Second, when feasible, interventions should ideally be designed to address existing barriers. This warrants thoughtful selection of convenient locations and mode of delivery, including face-to-face interactions or thoughtful integration of human support into virtual/non-face-to-face encounters to potentially strengthen therapeutic alliance and build trust. Third, limited available data suggest that it may be more challenging to achieve improvement in medication adherence in hypertension compared to diabetes; however, more studies are needed in this area. Finally, it is imperative to address the current gap in knowledge about medication adherence in Black patients with kidney disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented as a poster at the 2019 Vanderbilt University Medical Center SRTP program supported by T35DK007383. It was supported in part by NIH NIDDK 1K23DK114566-01A1 (Umeukeje) and NIH 1 R03 DK129626-01 (Umeukeje), NIA-3K02AG059140-02S1 (Bruce) and NIH R01DK03935-01A1 (Cavanaugh). KN is supported in part by NIH research grants ULITR001881, P30AG021684 and P50MD017366. The project described was supported by the National Center for Research Resources, grant UL1 RR025975-01, and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant 2 UL1 TR000445-06. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Spanakis EK, Golden SH. Race/ethnic difference in diabetes and diabetic complications. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(6):814–823. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0421-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiyanbola OO, Kaiser BL, Thomas GR, Tarfa A. Preliminary engagement of a patient advisory board of African American community members with type 2 diabetes in a peer-led medication adherence intervention. Res Involv Engagem. 2021;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00245-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norton JM, Moxey-Mims MM, Eggers PW, et al. Social determinants of racial disparities in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(9):2576. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derose SF, Rutkowski MP, Crooks PW, et al. Racial differences in estimated GFR decline, ESRD, and mortality in an integrated health system. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(2):236–244. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services OoMH. Diabetes and African Americans; 2021. Available from: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=18. Accessed March 15, 2021.

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services C, Office of Minority Health. Heart disease and African Americans; 2021. Available from: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=19. Accessed March 15, 2021.

- 7.National Institutes of Health NIoDaDaKD. 2018 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. United States Renal Data System; 2018. Available from: https://www.usrds.org/2018/view/Default.aspx. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 8.Choi AI, Rodriguez RA, Bacchetti P, Bertenthal D, Hernandez GT, O’Hare AM. White/black racial differences in risk of end-stage renal disease and death. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):672–678. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies M, Elwyn G. Advocating mandatory patient ‘autonomy’ in healthcare: adverse reactions and side effects. Health Care Anal. 2008;16(4):315–328. doi: 10.1007/s10728-007-0075-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyre AD, Krousel-Wood MA, Muntner P, Kawasaki L, DeSalvo KB. Prevalence and predictors of poor antihypertensive medication adherence in an urban health clinic setting. J Clin Hypertens. 2007;9(3):179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06372.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham A, Crittendon D, Konys C, et al. Critical race theory as a lens for examining primary care provider responses to persistently-elevated HbA1c. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113(3):297–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anghel LA, Farcas AM, Oprean RN. An overview of the common methods used to measure treatment adherence. Med Pharm Rep. 2019;92(2):117–122. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seng JJB, Tan JY, Yeam CT, Htay H, Foo WYM. Factors affecting medication adherence among pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of literature. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52(5):903–916. doi: 10.1007/s11255-020-02452-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeam CT, Chia S, Tan HCC, Kwan YH, Fong W, Seng JJB. A systematic review of factors affecting medication adherence among patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(12):2623–2637. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4759-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umeukeje E, Merighi J, Browne T, et al. Health care providers’ support of patients’ autonomy, phosphate medication adherence, race and gender in end stage renal disease. J Behav Med. 2016;39(6):1104–1114. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9745-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umeukeje EM, Osman R, Nettles AL, Wallston KA, Cavanaugh KL. Provider attitudes and support of patients’ autonomy for phosphate binder medication adherence in ESRD. J Patient Exp. 2019;2374373519883502. doi: 10.1177/2374373519883502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey JE, Wan JY, Tang J, Ghani MA, Cushman WC. Antihypertensive medication adherence, ambulatory visits, and risk of stroke and death. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):495–503. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1240-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polonsky WH, Henry RR. Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1299–1307. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S106821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid H, Hartmann B, Schiffl H. Adherence to prescribed oral medication in adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: a critical review of the literature. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14(5):185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie Z, St Clair P, Goldman DP, Joyce G. Racial and ethnic disparities in medication adherence among privately insured patients in the United States. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212117–e0212117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misdrahi D, Petit M, Blanc O, Bayle F, Llorca PM. The influence of therapeutic alliance and insight on medication adherence in schizophrenia. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;66(1):49–54. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.598556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umeukeje E, Wallston K, Lewis J, et al. Health care climate is related to phosphorus control in end stage renal disease. J Investig Med. 2014;62(Issue 2):547. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langer N. Culturally competent professionals in therapeutic alliances enhance patient compliance. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1999;10(1):19–26. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heath G, Cooke R, Cameron E. A theory-based approach for developing interventions to change patient behaviours: a medication adherence example from paediatric secondary care. Healthcare. 2015;3(4):1228–1242. doi: 10.3390/healthcare3041228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sirur R, Richardson J, Wishart L, Hanna S. The role of theory in increasing adherence to prescribed practice. Physiother Can. 2009;61(2):68–77. doi: 10.3138/physio.61.2.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ. 2007;334(7591):455–459. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumrosen C, Desta R, Cavanaugh KL, et al. Interventions incorporating therapeutic alliance to improve hemodialysis treatment adherence in black patients with End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) in the United States: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1435–1444. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S260684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosal MC, Heyden R, Mejilla R, et al. A virtual world versus face-to-face intervention format to promote diabetes self-management among African American women: a pilot randomized clinical trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2014;3(4):e54. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogner HR, de Vries HF. Integrating type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression treatment among African Americans: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(2):284–292. doi: 10.1177/0145721709356115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynch EB, Mack L, Avery E, et al. Randomized trial of a lifestyle intervention for urban low-income African Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1174–1183. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04894-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magee MF, Nassar CM, Mete M, White K, Youssef GA, Dubin JS. The synergy to enable glycemic control following emergency department discharge program for adults with type 2 diabetes: step-diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(11):1227–1239. doi: 10.4158/ep15655.Or [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Migneault JP, Dedier JJ, Wright JA, et al. A culturally adapted telecommunication system to improve physical activity, diet quality, and medication adherence among hypertensive African-Americans: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(1):62–73. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9319-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogedegbe GO, Boutin-Foster C, Wells MT, et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect intervention and medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):322–326. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogedegbe G, Tobin JN, Fernandez S, et al. Counseling African Americans to control hypertension: cluster-randomized clinical trial main effects. Circulation. 2014;129(20):2044–2051. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.113.006650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svarstad BL, Kotchen JM, Shireman TI, et al. Improving refill adherence and hypertension control in black patients: Wisconsin TEAM trial. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013;53(5):520–529. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2013.12246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zha P, Qureshi R, Porter S, et al. Utilizing a mobile health intervention to manage hypertension in an underserved community. West J Nurs Res. 2019;42:019394591984793. doi: 10.1177/0193945919847937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoenthaler A, Leon M, Butler M, Steinhaeuser K, Wardzinski W. Development and evaluation of a tailored mobile health intervention to improve medication adherence in black patients with uncontrolled hypertension and type 2 diabetes: pilot randomized feasibility trial. JMIR mHealth Uhealth. 2020;8(9):e17135. doi: 10.2196/17135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins-McNeil J, Edwards CL, Batch BC, Benbow D, McDougald CS, Sharpe D. A culturally targeted self-management program for African Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Can J Nurs Res. 2012;44(4):126–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allegrante JP, Peterson JC, Boutin-Foster C, Ogedegbe G, Charlson ME. Multiple health-risk behavior in a chronic disease population: what behaviors do people choose to change? Prev Med. 2008;46(3):247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall GL, Heath M. Poor medication adherence in African Americans is a matter of trust. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(4):927–942. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00850-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laster M, Shen JI, Norris KC. Kidney disease among African Americans: a population perspective. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(5):S3–S7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hibbard JH, Greene J, Becker ER, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities and consumer activation in health. Health Aff. 2008;27(5):1442–1453. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santarossa S, Kane D, Senn CY, Woodruff SJ. Exploring the role of in-person components for online health behavior change interventions: can a digital person-to-person component suffice? J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(4):e144–e144. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McQuaid EL, Landier W. Cultural issues in medication adherence: disparities and directions. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):200–206. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4199-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettey CM, McSweeney JC, Stewart KE, et al. African Americans’ perceptions of adherence to medications and lifestyle changes prescribed to treat hypertension. Sage Open. 2016;6(1). doi: 10.1177/2158244015623595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):462–473. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mayberry LS, Osborn CY. Empirical validation of the information-motivation-behavioral skills model of diabetes medication adherence: a framework for intervention. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(5):1246–1253. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bennett B, Sharma M, Bennett R, Mawson AR, Buxbaum SG, Sung JH. Using social cognitive theory to predict medication compliance behavior in patients with depression in southern United States in 2016 in a cross-sectional study. J Caring Sci. 2018;7(1):1–8. doi: 10.15171/jcs.2018.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jankowska-Polańska B, Karniej P, Polański J, Seń M, Świątoniowska-Lonc N, Grochans E. Diabetes mellitus versus hypertension—Does disease affect pharmacological adherence?. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11(1157). doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karakurt P, Kaşikçi M. Factors affecting medication adherence in patients with hypertension. J Vasc Nurs. 2012;30(4):118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2012.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spence JD, Rayner BL. Hypertension in Blacks. Hypertension. 2018;72(2):263–269. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saeed AD, Yang E. Racial disparities in hypertension prevalence and management: a crisis control? Expert analysis. 2020. [April 6, 2020]. Available from: https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/04/06/08/53/racial-disparities-in-hypertension-prevalence-and-management. Accessed September 29, 2022.

- 56.Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of blood-pressure reduction in black barbershops. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):1291–1301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun K, Eudy AM, Criscione-Schreiber LG, et al. Racial disparities in medication adherence between African American and caucasian patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and their associated factors. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(7):430–437. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]