Abstract

Background

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the perceptions of clinical faculty while working with medical students in a novel setting of virtual care following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Activity

A survey of faculty, fellows, and residents was conducted to assess educators’ perceptions of virtual teaching before trying it and after 3 months of experience.

Results

Perceived effectiveness of teaching students acute care significantly improved as did perceived effectiveness of teaching chronic care.

Discussion

We anticipate that continued experience and comfort with virtual platforms would boost this perception further, allowing faculty development to be honed for optimal teaching in this new paradigm.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40670-022-01685-9.

Keywords: Telemedicine, Education, Faculty, Perception

Background

While virtual care has seen a significant rise over the last 5 years [1], the COVID-19 pandemic catapulted the use of telemedicine [2, 3]. In this new landscape, medical students need to learn how to conduct telemedicine visits, develop a good “webside” manner [4], and be assessed and evaluated within a virtual context. Since the pandemic began, many studies have examined telemedicine teaching related to curriculum development [5–8] and student feedback [7, 9]. Our study focused on the perspective of the teachers. Understanding the initial impressions and experiences of teaching physicians with telemedicine is critical. Their experiences will influence their level of adoption [10, 11] and the success of a curriculum [12].

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the perceptions of clinical faculty while working with medical students in a novel setting: virtual care. Our hypothesis was that the change to virtual teaching would be met with low perceived effectiveness by faculty but would increase with continued exposure to virtual care.

Activity

Context

University of Michigan medical school’s Family Medicine clerkship is a 4-week required core clerkship. Students were removed from clinical care in March 2020 and returned in June 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The length of the clerkship was shortened to 3 weeks from June to December 2020 to compensate for lost time. Shortened 3-week rotations were previously shown to have similar outcomes in terms of student satisfaction, National Board of Medical Examiners subject tests, and clinical skills [13].

Students were expected to participate in both in-person visits and virtual visits. Physicians were given basic information regarding the use of shared phone and video visits. They were also given access to virtual meeting spaces (Zoom™ or Bluejeans™ platforms) where they were able to complete precepting and teaching outside of patient visits.

Participants

All faculty physicians, fellows, and resident physicians in the University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine were invited to participate.

Data Collection

Participants completed an anonymous, Qualtrics web survey in June 2020 prior to return of students. Participants were then invited to complete the same survey in August 2020, following 3 cohorts of student clerkships. Along with demographic data, we asked about perceived effectiveness of telehealth format in teaching medical students various forms of care including acute care, chronic care, and health promotion/preventive care (HPP) (see ESM Appendix A for complete survey).

Data Analysis

We analyzed average scores of perceived effectiveness of teaching using Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney tests (T-tests were not used because the variables are not normally distributed) and utilized Fisher’s exact test for categorical distributions. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

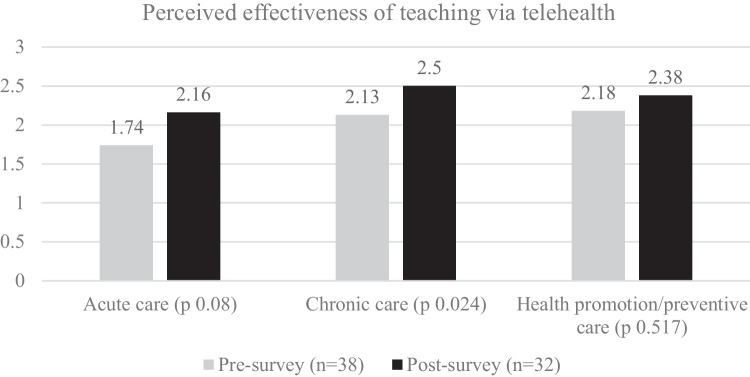

Of 137 possible participants, 38 responded to the pre-survey (27.7%) and 32 to the post-survey (23.4%). Participants in the pre-survey and post-survey were compared by demographics with no significant differences found by gender, academic rank, years since medical school, primary clinical site, comfort using electronic health records, experience with telehealth sessions prior to June 8, 2020, average clinic sessions per week, or average patients per session. Perceived effectiveness of teaching students acute care via telehealth format significantly improved from average score 1.74 (0.64) to 2.16 (0.57) (p-value: 0.008) (Fig. 1). Further, perceived effectiveness of teaching chronic care also significantly improved from 2.13 (0.62) to 2.50 (0.67) (p-value: 0.024). While there was a slight increase, perceived effectiveness in teaching HPP did not show significant change, from average 2.18 (0.83) to 2.38 (1.01) (p-value: 0.517).

Fig. 1.

Perceived effectiveness of teaching via telehealth

Discussion

This study explored educators’ experiences teaching medical students during virtual-based care. The hypothesis was that our faculty would have improved perception of teaching in the virtual setting with additional exposure. Overall, our data showed that with experience educators felt more effective teaching acute and chronic care in a virtual setting. This confirmed our hypothesis that while there would be initial concern, satisfaction would improve with continued exposure. We did not, however, find statistical difference in perceived efficacy of teaching HPP. This could be attributed to a high baseline confidence in ability to teach these concepts without being physically present or due to true need to teach these concepts in an in-person encounter.

Our study has several limitations. We are a single-family medicine department, further limited by a low response rate. The intervention was also limited to 3 months which may have limited generalization to long-term satisfaction. Furthermore, use of less-experienced resident physicians as preceptors may have led to lower perceived effectiveness of teaching. A 2015 survey of family medicine residents showed residents receive less than 8 h of instruction on how to teach [14]. Finally, some faculty may have completed the post survey with minimal or no experience working with students in a virtual setting and their perceptions of (including biases) and own experience with virtual patient care may have impacted the findings.

Virtual teaching is a skill that will need to be mastered by all medical educators and it is critically important that we continue to consider our teaching physicians’ perceptions of and experiences in this format as we move forward in this new paradigm.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed by University of Michigan IRB and granted exemption from formal review (HUM00182107).

Informed Consent

N/A.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Barzansky B, Etzel SI. Medical schools in the United States, 2018–2019. JAMA. 2019;322(10):986–995. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iancu AM, Kemp MT, Alam HB. Unmuting medical students’ education: utilizing telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(7):e19667. 10.2196/19667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(7):1132–1135. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teichert E. Training docs on ‘webside manner’ for virtual visits. 2016. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20160827/MAGAZINE/308279981/training-docs-on-webside-manner-for-virtual-visits. Accessed 7 Nov 2020.

- 5.Aungst TD, Patel R. Integrating digital health into the curriculum-considerations on the current landscape and future developments. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120519901275. doi: 10.1177/2382120519901275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stovel RG, Gabarin N, Cavalcanti RB, Abrams H. Curricular needs for training telemedicine physicians: a scoping review. Med Teach. 2020;42(11):1234–1242. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1799959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker C, Echternacht H, Brophy PD. Model for medical student introductory telemedicine education. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(8):717–723. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2018.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waseh S, Dicker AP. Telemedicine training in undergraduate medical education: mixed-methods review. JMIR Med Educ. 2019;5(1):e12515. doi: 10.2196/12515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sartori DJ, Olsen S, Weinshel E, Zabar SR. Preparing trainees for telemedicine: a virtual OSCE pilot. Med Educ. 2019;53(5):517–518. doi: 10.1111/medu.13851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4–12. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16674087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeJong C, Lucey CR, Dudley RA. Incorporating a new technology while doing no harm, virtually. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2351–2352. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks E, Turvey C, Augusterfer EF. Provider barriers to telemental health: obstacles overcome, obstacles remaining. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(6):433–437. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monrad SU, Zaidi NLB, Gruppen LD, Gelb DJ, Grum C, Morgan HK, Daniel M, Mangrulkar RS, Santen SA. Does reducing clerkship lengths by 25% affect medical student performance and perceptions? Acad Med. 2018;93(12):1833–1840. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al achkar M, Davies MK, Busha ME, Oh RC. Resident-as-teacher in family medicine: a CERA survey. Fam Med. 2015;47(6):452–8. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.