Abstract

The purpose of this study is to describe the context, curriculum design, and pilot evaluation of the educational program “Sexual and Gender Minority Cancer Curricular Advances for Research and Education” (SGM Cancer CARE), a workshop for early-career researchers and healthcare providers interested in gaining knowledge and skills in sexual and gender minority (SGM) cancer research and healthcare advocacy. A needs assessment of a sample of clinicians and researchers (n = 104) and feedback from an Advisory Board informed the curriculum design of the SGM Cancer CARE workshop. Four SGM-tailored modules, focusing on epidemiology, clinical research, behavioral science and interventions, and community-based participatory approaches, were developed and tested in a 2.5-day virtual format among 19 clinicians and researchers. A fifth module to provide feedback to participants on brief presentations about their SGM cancer research ideas or related efforts was added later. A mixed-methods evaluation comprised of pre- and post-modular online evaluation surveys and virtual focus groups was used to determine the degree to which the workshop curriculum met participant needs. Compared to pre-module evaluations, participants reported a marked increase in SGM cancer research knowledge in post-module scores. Quantitative results were supported by our qualitative findings. In open field response survey questions and post-workshop focus groups, participants reported being extremely pleased with the content and delivery format of the SGM Cancer CARE workshop. Participants did regret not having the opportunity to connect with instructors, mentors, and colleagues in person. The SGM Cancer CARE curriculum was shown to increase the knowledge, skills, and level of preparedness of early-career clinicians and scientists to conduct culturally relevant and appropriate research needed to improve care for SGM persons across the cancer care continuum from prevention to survivorship.

Keywords: Cancer health disparities, Sexual and gender minorities, SGM, LGBTQ, Education and training, Healthcare providers, Researchers

Introduction

Over the last decade, the National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), the American Association of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have called for researchers and clinicians to address disparities in sexual and gender minority (SGM) cancer [1–3]. They identified needs for risk factor reduction, implementation of existing evidence-based cancer prevention strategies, increased early cancer detection, and improved treatment, survivorship, and end-of-life care [1]. Among recommendations to rectify these gaps, ASCO proposed increases in [1] workforce development and diversity, and [2] research strategies to address the diverse needs of SGM individuals receiving “disparate” and “suboptimal” care across the cancer continuum [1]. In response, we published a “National Action Plan to Increase SGM Health Equity Through Research and Provider Training and Education” [4] that identified core competencies to ensure effective training for researchers and healthcare providers interested in conducting SGM cancer research. We then assembled a multi-disciplinary, multi-institutional research team and board of expert advisors with specific expertise in SGM and cancer research, healthcare provision, and SGM community advocacy. In July 2019, we were awarded a National Cancer Institutes R25 “Courses for Skills Development” award to develop a curriculum for researchers and healthcare providers interested in gaining knowledge and skills in SGM cancer research and healthcare advocacy.

Over 2 years, we designed a four-part curriculum for the “Sexual and Gender Minority Cancer Curricular Advances for Research and Education” (SGM Cancer CARE) workshop, pilot testing the curriculum during the Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians (BNGAP) “LGBT Health Workforce Virtual Conference” in April 2021. Here, we describe the context for the curriculum, design of the four key modules, and findings from course evaluations. We also discuss the need to expand this initial curriculum through alternative learning modalities, scientific networks, and coordinated efforts to collect national-level SGM data.

Context

Disparities in cancer incidence and mortality are influenced by interrelated socioenvironmental, economic, and structural factors, including sex assigned at birth, race, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status [5], as well as sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression (1). Cancer risk is likewise associated with sexually transmitted infections (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and human papillomavirus (HPV)) which have disproportionately affected SGM groups [6]. Furthermore, rates of cancer in SGM populations are associated with higher rates of cancer risk behaviors, including tobacco use [7], alcohol consumption [8], obesity [9], and nulliparity [9]. These risk factors, as well as poor access to cancer prevention, screening, and culturally competent care [10], create a disproportionate burden of cancers, particularly those of the anus, cervix, colon and rectum, endometrium, breast, lung, and prostate, reported to be more prevalent among specific SGM groups [6–8].

For SGM groups, gaps exist across the cancer care continuum. Studies indicate that lower cancer screening rates among SGM communities are associated with a higher prevalence of cancer, as well as detection of cancer at later stages [11]. Challenges to early detection are compounded because some SGM populations encounter unique barriers to cancer screening and prevention [12]. For some, previous experiences of discrimination, anti-SGM sentiment, and/or micro-aggressions discourage screening and healthcare-seeking behaviors [12]. SGM individuals may experience “minority stress” [13], when chronic, underlying concerns about prejudice and discrimination relating to their stigmatized identities become internalized. Such negative experiences can be magnified in healthcare settings at the onset of and during cancer treatment, causing SGM individuals to feel unrecognized and unwelcomed and potentially intensifying cancer-related stress [14]. This is particularly relevant for transgender and gender non-conforming individuals who may experience negotiations of gender expectations with multiple providers and others as additional fatiguing barriers to cancer care [15]. In particular, lack of provider knowledge about SGM health has been shown to contribute to SGM reticence to access healthcare, as improvements to SGM-appropriate delivery of cancer care have been slow [16]. A 2016 national survey of more than 450 oncologists from 45 cancer centers demonstrated that gaps in cancer center environments including ineffective sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) data collection, inadequate staff and provider SGM specific knowledge, education and skills, and lack of cultural competence and cultural humility challenge efforts to reduce SGM cancer disparities [16].

Although the Association of American Medicine Colleges (AAMC) published AAMC Recommendations: Institutional Programs and Educational Activities to Address the Needs of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender (GLBT) Students and Patients in 2007 [17], persistent barriers hinder the integration of recommended core competencies into medical education. Researchers suggest that integration of SGM core competencies in medical curricula and standardized tools for consistent evaluation of SGM medical school curricula are lacking [18]. Furthermore, reforms achieved since 2010 to address SGM education have focused on the undergraduate medical level, with insufficient education at graduate medical education, and continuing education levels [19]. To this point, authors of the national survey conducted in 2016 noted that oncologists recognized deficiencies in communication with SGM patients about their care, and highlighted the need to train oncologists and allied health professionals in SGM healthcare needs and SGM affirmative communication skills [20].

Advances across the cancer care continuum and better health outcomes for underserved SGM individuals depend on building the evidence base for high-quality, tailored clinical care. Still, SGM cancer research is extremely limited to the point of being characterized as “in its infancy” [21], and ASCO maintains that research deficits engender “insufficient knowledge about the health care needs, health outcomes, lived experiences, and effective interventions to improve outcomes for SGM individuals” [1]. Historical funding trends of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) inform the “de facto definition of LGB health research as HIV research” [22], and perpetuate gaps in research relevant to improving SGM cancer patient health outcomes, particularly in cancer research not linked to HIV/AIDS.

Educating, training, and connecting career researchers for high-quality, multi-disciplinary SGM cancer studies are urgent. More investigators must be equipped with the tools and resources needed to conduct research that knowingly involves SGM patients. As SGM patients exist within and across all cancer patient populations, research may not focus specifically on SGM health, but cancer care more broadly, and recognition of SGM populations is crucial in identifying and addressing disparities in cancer care. Requisite tools for inclusion of SGM populations in cancer research include SGM cultural competence, strategies to engage SGM individuals in participatory research, skills to compete successfully for grant funding, and experienced consultants and collaborators to facilitate SGM cancer team science. Nevertheless, we are unaware of any educational or training programs in SGM cancer research, and such opportunities are essential to developing patient-centered interventions, a fundamental feature of high-quality oncology care and prevention. The proposed research education program, SGM Cancer CARE, addresses the need for a cadre of trained professionals to strengthen the evidence base needed to improve care across the cancer spectrum for SGM individuals, and will serve as a durable resource to inform future SGM cancer research training nationwide.

Course Development/Methods

Needs Assessment

As a first step in developing the SGM Cancer CARE workshop curriculum, we conducted an educational needs assessment among early-career scientists and clinicians to systematically collect and analyze information to identify, understand, and prioritize gaps in knowledge and skills among these individuals. A 32-item online survey was used to gather information regarding the professional characteristics of the intended audience, including their experience with SGM populations and cancer research, and their topics of interest for inclusion in the SGM cancer research curriculum (Table 1).

Table 1.

Curriculum topics identified as essential or high priority from 7 possible responses (also including moderate priority, neutral, somewhat a priority, low priority, not a priority)

| Curriculum topic | “Essential” or “high priority” |

|---|---|

| Identifying cancer research priorities for sexual minorities | 77.4% |

| Identifying cancer research priorities for gender minorities | 76.9% |

| Identifying mentors to conduct a cancer study or dissemination program for gender minorities | 75.4% |

| Review of current literature on SGM cancer health disparities | 70.2% |

| Identifying mentors to conduct a cancer study or dissemination program for sexual minorities | 67.9% |

| How to build an advisory committee of relevant stakeholders for SGM cancer research | 67.4% |

| How to collect SGM participant data from electronic databases | 61.7% |

| Review of participatory research and community engagement methods | 61.3% |

| How to write SGM-inclusive grant applications | 55.8% |

| How to build a research team for SGM cancer health disparities research | 51.4% |

| Description of funding agencies with SGM cancer research support | 50.6% |

The survey was disseminated to listservs comprised of health professionals with SGM health or cancer research interests from July 20, 2018, to August 3, 2018. A total of 104 individuals completed the survey. Two-thirds of survey participants (n = 78) identified as junior faculty (Assistant Professor or Instructor), or trainee-level health professionals (post-doctorate, resident, or fellow) in the MD/DO, DrPH, or PhD pipeline; 63% reported a current research professional role; and 56% currently work in an academic medical center. Additionally, a large proportion of survey participants reported limited SGM cancer research experience: 47% had never conducted cancer research inclusive of gender minorities, 43% had never conducted cancer research inclusive of sexual minorities, and 30% had never conducted cancer research. Responses from these early-career professionals revealed that in-person training (65%), webinars (65%), and online self-paced modules (65%) were “Very desirable” and “desirable” formats for curricula presentations. These responses suggest that web-based educational presentations built on an in-person workshop curriculum could be a successful strategy to expand educational offerings. Additionally, more than a quarter of survey participants reported having no funding for travel to in-person training on SGM cancer research (27%) indicating that offering travel awards would facilitate increasing the number of professionals learning how to conduct SGM cancer research.

Advisory Board

We shared findings from the needs assessment with our advisory board of eight experts who had experience with SGM populations and in-depth knowledge in multiple key areas, including community-based participatory research, epidemiology, nursing, psychology, clinical medical care, cancer advocacy, and curriculum development. Members were identified due to their national contributions and leadership in SGM and cancer research, as well as through professional contacts to ensure broad and diverse representation. Nearly all members collaborated on curricular module creation, and several were directly involved in teaching modules for, and evaluating, the pilot workshop.

Curriculum Development

Four foundational research areas were developed as key modules for the SGM Cancer CARE workshop: epidemiology and population-level research, clinical cancer research, behavioral science and interventions, and community-based participatory research. Each 90-min module was developed through a collaborative and iterative process that included the following steps: reviewing literature and drafting initial content by the designated project team member; gathering curricula and other resources; initial review by module teams comprised of one or more lead project team members and several advisory board members self-nominated to modules based on expertise; revisions by project team members; design of workshop activities for each module; rehearsals of module delivery with the Advisory Board and an instructional designer; and pilot delivery of modules in a pilot workshop that included facilitated evaluation focus groups. An effort was made to feature as many SGM cancer research examples in every module, as well as to keep the focus on aspects that were unique to conducting SGM cancer research, as they would not likely be learned elsewhere. Common cross-sectional themes tailored to SGM cancer care, consisting of intersectionality, ethical considerations, barriers to research, and best practices, were included across all modules. Participants with shared research interests engaged in interactive breakout sessions developing research questions, and applying discipline specific tools learned in each module to the research questions to reinforce learning and educational principles. Inclusion of breakout rooms likewise created interaction and small group conversations necessary to reduce participant fatigue from prolonged computer video-conference communication, as was interactive chat messaging moderated by workshop instructors to engage participants individually and encourage participant exchanges on the topic during presentations.

Recruiting and Selecting Workshop Participants

The SGM Cancer CARE workshop was promoted through the BNGAP website and member lists, as well as a Twitter account (@SGMCancerCARE) dedicated to the workshop. We instructed workshop applicants to complete an online form capturing contact details, career stage, previous research experience, and workshop expectations. A total of 20 early- and mid-career researchers and clinical care providers from across the USA were selected to participate in the workshop. Participants were diverse by gender identity (15 women, 4 men, 1 genderfluid), sexual identity (11 sexual minorities, 9 heterosexuals), race/ethnicity (15 White, 2 Asian, 2 Hispanic, and 1 Multiracial), geographic location (8 Northeast, 4 West, 3 Southwest, 3 Midwest, and 2 South), professional role (9 health professionals, 7 residents/fellows, and 4 graduate students), and degree (11 PhD, 3 MD/PhD, 3 MD, 2 MSW, and 1 MPH). Participants were also diverse in their research experience: cancer research experience (13 with 0–5 years experience, 4 with 6–10 years experience, and 3 with more than 10 years experience) and SGM research experience (14 with 0–5 years experience, 5 with 6–10 years experience, and 1 with more than 10 years experience), and 9 participants served as an SGM research principal investigator, 8 participants served as a cancer research principal investigator, and one participant had received an R01 grant. There was no fee for attendance, as the virtual format prevented costs associated with renting event space, ordering food, and supplying in-person materials (e.g., name badges, folder).

Piloting the SGM Cancer CARE Workshop

Due to COVID-19 health and safety concerns, a 60-min pre-workshop “meet & greet” social session and the pilot workshop were delivered remotely using the Zoom online meeting platform in April 2021. The workshop consisted of 9 educational contact hours over 3 days. The workshop schedule accommodated participants from all time zones across the country.

The first day began with a welcome and brief orientation to Zoom and features to be used in the workshop (e.g., changing name, annotation toolbar), description of learning objectives and focus, instruction of SGM terminology, and a review of expectations for participation and engagement. Two keynote speakers provided historical and forecasting perspectives of SGM cancer research. Keynotes were followed by the first educational module “Epidemiology & Population-Level Research.” This module included uses and types of epidemiology in health research and public health (including in grantsmanship), orientation to and examples of epidemiologic research among the cancer continuum, introduction to key epidemiological concepts (i.e., selection bias, information bias, confounding, internal/external validity), and the perils of small sample sizes. We discussed the impact of insufficient data collection of sexual orientation and gender identity on SGM cancer research, and we reviewed the availability of nationally representative data resources with SOGI data for potential cancer research.

On the second day, two additional modules were delivered. The “Clinical Cancer Research” module highlighted the importance of including SGM patients in clinical research and defined the scope of clinical trials. This session discussed strategies to include SGM patients in clinical research and outlined specific barriers with possible solutions. After a break, the “Behavioral Science & Interventions in SGM Cancer” module presented frameworks for conducting research with diverse SGM communities, highlighting the importance of addressing intersectionality [5] and minority stress [13] in the design and conduct of SGM cancer research. We presented a variety of behavioral models to guide SGM cancer research and intervention development.

The “Community-Based Participatory Approaches for SGM Cancer Research” module was offered on the third day. This module defined community-based participatory research (CBPR), taught participants how to establish a researcher-SGM community partnership, and use information technology to facilitate community engagement. Emphasis was placed on ethical considerations for engagement of SGM groups in cancer research.

Participants had full access to all workshop materials and educational resources in shared file folders hosted in the cloud via Google Drive. These included a roster of contact information for project team members, enrolled participants, Advisory Board members, and module facilitators; PowerPoint presentations and curricular worksheets; required readings; and additional educational and resource materials.

Evaluation

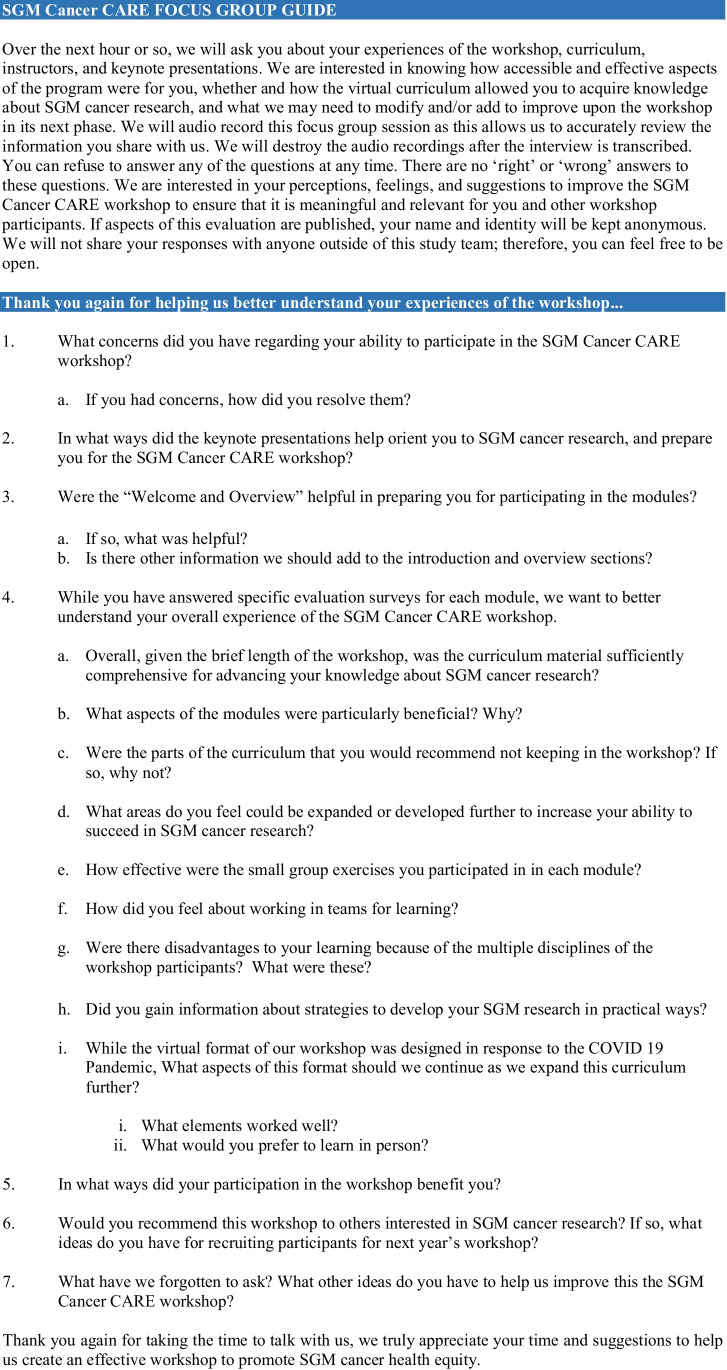

To determine the degree to which the SGM Cancer CARE curriculum met the needs of the participants for whom we designed this workshop, we used a mixed-methods approach (Fig. 1). We collected applicant demographic data including professional stage, experience conducing cancer research, and experience conducting research and/or advocacy with the SGM population to inform baseline metrics for evaluation. Following participation in the initial “Meet and Greet” orientation, participants received a link to an initial REDCap survey to assess effectiveness of recruitment and ease of the workshop application process. Prior to and upon completion of each curricular module, participants received links to pre- or post-curricular REDCap surveys to assess participants’ confidence regarding knowledge of specific SGM cancer care topics covered in the module. The statements in these surveys were anchored at 1 = Not at all confident to 5 = Extremely confident. See Fig. 2 for an example of the pre-post survey used to evaluate the Epidemiology and Population-Level Research Module. We computed average and standard deviation for each survey statement, as well as for the total survey score. Pre/post score differences were also calculated (Table 2). Compared to pre-module evaluations, participants reported marked increases in their confidence about SGM cancer research knowledge in post-module scores regardless of discipline (Fig. 3). Finally, all workshop attendees participated in one of two virtual focus groups designed to better understand participant experiences of the overall SGM Cancer Care workshop, and to elicit suggestions for ways to improve the process, content, and delivery of the workshop (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Mixed-methods assessment of the SGM Cancer CARE workshop

Fig. 2.

Example of post-SGM Cancer CARE workshop evaluation

Table 2.

Total and individual question scores before and after modules

| Module | Max score | Total score [mean (SD)] | Individual questions [mean (SD)] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before module | After module | p | Before module | After module | p | ||

| Behavioral science | 60 | 31.4 (6.7) | 43.0 (8.6) | < 0.0001 | 2.6 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Epidemiology | 35 | 18.2 (7.7) | 28.7 (5.1) | < 0.0001 | 2.6 (1.4) | 4.1 (0.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Clinical research | 25 | 10.6 (4.0) | 18.2 (3.1) | < 0.0001 | 2.1 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Community research | 30 | 16.5 (5.8) | 21.4 (5.2) | < 0.0001 | 2.8 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.0) | < 0.0001 |

Fig. 3.

Distribution of responses before and after SGM cancer CARE modules

Fig. 4.

SGM Cancer CARE focus group guide

Data gathered through open field survey questions and qualitative focus groups noted that the curriculum contained “excellent material,” and that they appreciated “lessons learned” from SGM research experts “who had actually conducted SGM cancer research.” Participants particularly appreciated the pragmatic aspects of the curriculum, including “tangible resources for finding SGM specific information,” how to handle “intersectionality within the research realm,” and how to “ethically build a community advisory board” with multi-level stakeholders, including SGM community organizations, physicians, patients, families, and other key stakeholders. One participant said this workshop “helped [her] to feel more comfortable and confident as a heterosexual, cisgender woman conducting research with SGM communities.” Given the common experience of Zoom fatigue in the context of remote work due to the COVID-10 pandemic, these positive comments are notable, suggesting high levels of engagement. Also notable was the perfect attendance of participants for all 3 workshop days.

In addition, participants commented on, and were pleased with, workshop delivery and process, specifically, the multi-disciplinary, team-based approach to learning. Participants enjoyed working in small groups “…with other disciplines, especially interacting with clinicians,” having time to talk to “amazing faculty,” and engaging with people with “different backgrounds.” Participants were very clear that they would have appreciated having this conference in person, as that would have promoted development of deeper connections, and allowed for continued discussions with faculty, instructors, the Advisory Board, and peers beyond the modular workshop configuration. One participant explained, “I would have liked more casual networking and discussion time among attendees and mentors. I wonder if we would end up with a few multi-site research protocols planned and papers (reviews or secondary data analysis) with attendees and mentors as authors.”

Such comments in our evaluation did offer room for growth and improvement, including further refinement of the modules by (1) lengthening core modules to encourage more group-, problem-, and project-based exercises; (2) adding a fifth module to focus entirely on providing feedback on participants’ projects; and (3) and moving to in-person workshops with virtual follow-ups to maximize hybrid learning models for participants. For the added fifth module, scheduled at a later time, participants presented via Zoom to other participants and Advisory Committee members in a 5 × 5 format (i.e., five slides in 5 min to introduce their research, goals, and aims). Assigned members of the project team and Advisory Board reviewed participant specific aims and NIH biosketch documents in advance and provided real-time comments and critiques to start group discussion during the session. Participants were extremely pleased with the format and several have continued working with their faculty reviewers.

Discussion

The SGM Cancer CARE workshop pilot was a well-received and impactful initiative that advances needed progress in preparing researchers to conduct SGM cancer research. Workshop participants reported significant improvement in their understanding of and their confidence in applying core concepts involved in SGM cancer research. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic preventing the delivery of the SGM Cancer CARE workshop in person, participants highly valued the opportunity to virtually network with and learn from junior and senior researchers with SGM cancer research interests and experience.

Although many graduate health schools and national organizations have developed curricula to prepare clinicians to provide clinical care for SGM populations [23], and the Curriculum for Oncologists on LGBT populations to Optimize Relevance and Skills (COLORS) has launched to improve SGM-related knowledge, attitudes, and clinical practices [24], no other educational efforts focus on SGM cancer research. The SGM Cancer CARE Workshop addresses this gap, translating scholarly recommendations and best practices for the conduct of research with SGM populations [10] into practical research skills including grantsmanship, research design, and ethical conduct, while simultaneously connecting scholars to networks of mentors and collaborators needed to succeed in SGM cancer research.

Workshop Challenges and Opportunities

Primary challenges affecting the launch of the SGM Cancer CARE pilot workshop stemmed primarily from the COVID-19 pandemic. The workshop, originally designed as a 2-day in-person event, was modified to a 3-day virtual format to minimize the fatiguing impact of prolonged computer screen time for participants. All in-person curricula were transformed into online modules, and paper-based evaluations to online surveys, and research poster exhibitions were canceled. Participants missed the opportunities for casual and unscheduled personal and professional engagement with workshop instructors, Advisory Board members, and other participants that facilitate networking and research community building that are difficult to facilitate during virtual events.

However, we also discovered opportunities for the expansion of the SGM Cancer CARE workshop afforded through the virtual format. Holding a virtual workshop removed financial barriers to participation for those with limited travel funds. It likewise allowed participants to continue working, taking care of children, and other activities that they would not have been able to do had they traveled for the conference. The virtual space challenged us to enhance our messaging with participants. We learned to connect throughout the workshop and afterwards crafting relevant messages about participant successes, new SGM cancer research, funding opportunities, collaborative opportunities, and workshop updates to participants. The supportive learning atmosphere we were able to create to facilitate virtual interaction (e.g., modular online curriculum, real-time activities utilizing the “annotate” function, breakout rooms, file-sharing, session recording) allowed us to consider ways to expand the SGM Cancer CARE workshop in a hybrid in-person/virtual format to increase curricular topics and optimize learning opportunities for diverse early-career professionals interested in enhancing their SGM cancer research.

Post-workshop Milestones

Multiple activities and accomplishments result in part from participation in our pilot workshop. Since completion of our workshop, our participants have co-authored 35 peer-reviewed publications on SGM cancer care, with participants serving as the lead or final author for 14 of the 35 publications. Participants also reported presenting their research at 11 national health conferences. Five participants reported receiving new grant funding for their SGM cancer research proposals. One participant was inducted into the NIH’s Independent Research Scholar Program and promoted to Research Fellow in May 2022. Awareness of our involvement in this education initiative during the promotion of the pilot workshop also led to an invited Special Issue for the Annals of LGBTQ Public and Population Health. [25] Twelve articles in this special issue describe strategies and policies that address current gaps in SGM cancer clinical care, education, leadership, and research.

Future Goals

With additional funding recently received from the National Cancer Institute, the SGM Cancer CARE curriculum will be disseminated both in person and virtually across the USA to achieve its goal of fostering a cadre of scientists and clinicians leading SGM cancer research. As a course for skills development, the curriculum will be expanded from updated modules from the pilot workshop with a new module featuring the use of mobile health (mHealth)/electronic health (eHealth) tools for SGM cancer research. The curriculum will also include a seminar series following the workshop to highlight ongoing SGM cancer research presented by established researchers who serve as accessible role models. These include research led by our Advisory Board members on reproductive health and fertility preservation for SGM adolescents and young adults with cancer, SGM cancer elder care, SGM cancer epidemiology, and over time, will also include research led by workshop alumni.

Conclusion

In a pilot test, the SGM Cancer CARE curriculum was shown to increase the knowledge, skills, and level of preparedness of clinicians and scientists for conducting SGM cancer research. Importantly, the evaluation demonstrated that the curriculum was successful in stimulating the interests of professionals with the capacity to make crucial contributions through research to improve cancer care across the continuum from prevention to survivorship. The annual dissemination of the workshop over the next 5 years will provide introduction and orientation to SGM cancer research skills and knowledge to more than two hundred early-career professionals who will subsequently lead innovations to improve the health of SGM populations.

Acknowledgements

The SGM Cancer CARE workshop is funded by a National Cancer Instituted funded R25, “Courses for Skills Development” award (1R25CA240113-01), with additional support provided through an NCI under award 1K22CA237639 to Principal Investigator Irene Tami-Maury. This manuscript is also supported by the Biostatics Shared Resource, facilities supported by the State of New Mexico and a University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center NCI-funded P30CA118100 award. We would like to thank Dr. Karen Parker and the NIH Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office, Liz Margolies and Scout at the National LGBT Cancer Network, and the Geographic Management of Cancer Health Disparities Program funded through the NCI’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities for assisting with recruitment and dissemination of the SGM Cancer CARE workshop.

Footnotes

Miria Kano and Irene Tamí-Maury are co-first authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Miria Kano, Email: mkano@salud.unm.edu.

Irene Tamí-Maury, Email: Irene.Tami@uth.tmc.edu.

References

- 1.Griggs J, Maingi S, Blinder V, Denduluri N, Khorana AA, Norton L, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement: strategies for reducing cancer health disparities among sexual and gender minority populations. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2203–2208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez-Stable (2016) Director’s Message 2016 National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. [Available from: https://nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors-corner/messages/message_10-06-16.html. Accessed 14 July 2022

- 3.The health of lesbian . gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kano M, Sanchez N, Tamí-Maury I, Solder B, Watt G, Chang S. Addressing cancer disparities in SGM populations: recommendations for a national action plan to increase SGM health equity through researcher and provider training and education. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35(1):44–53. doi: 10.1007/s13187-018-1438-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews AK, Breen E, Kittiteerasack P (2018) Social determinants of LGBT cancer health inequities. Semin Oncol Nurs 34(1):12–20. 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Park LS, Hernández-Ramírez RU, Silverberg MJ, Crothers K, Dubrow R. Prevalence of non-HIV cancer risk factors in persons living with HIV/AIDS: a meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England) 2016;30(2):273. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Berg CJ, Weber AA, Vu M, Nguyen J, Haardörfer R, et al. Tobacco use at the intersection of sex and sexual identity in the US, 2007–2020: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(3):415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corte C, Matthews AK, Stein KF, Lee C-K. Early drinking onset moderates the effect of sexual minority stress on drinking identity and alcohol use in sexual and gender minority women. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2016;3(4):480. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boehmer U, Bowen DJ, Bauer GR. Overweight and obesity in sexual-minority women: evidence from population-based data. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1134–1140. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pratt-Chapman ML, Eckstrand K, Robinson A, Beach LB, Kamen C, Keuroghlian AS et al (2022) Developing standards for cultural competency training for health care providers to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual persons: consensus recommendations from a national panel. LGBT Health 9(5). 10.1089/lgbt.2021.0464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Bristowe K, Hodson M, Wee B, Almack K, Johnson K, Daveson BA, et al. Recommendations to reduce inequalities for LGBT people facing advanced illness: ACCESSCare national qualitative interview study. Palliat Med. 2018;32(1):23–35. doi: 10.1177/0269216317705102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haviland K, Burrows Walters C, Newman S. Barriers to palliative care in sexual and gender minority patients with cancer: a scoping review of the literature. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29(2):305–318. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamen C (2018) Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) survivorship. Semin Oncol Nurs 34(1):52–59. 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Alpert AB, Gampa V, Lytle MC, Manzano C, Ruddick R, Poteat T, et al. I’m not putting on that floral gown: enforcement and resistance of gender expectations for transgender people with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(10):2552–2558. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schabath MB, Blackburn CA, Sutter ME, Kanetsky PA, Vadaparampil ST, Simmons VN, et al. National survey of oncologists at National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers: attitudes, knowledge, and practice behaviors about LGBTQ patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7):547–558. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quinn GP, Alpert AB, Sutter M, Schabath MB. What oncologists should know about treating sexual and gender minority patients with cancer. JCO Oncology Practice. 2020;16(6):309–316. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeVita T, Bishop C, Plankey M. Queering medical education: systematically assessing LGBTQI health competency and implementing reform. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1510703. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2018.1510703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pregnall AM, Churchwell AL, Ehrenfeld JM. A call for LGBTQ content in graduate medical education program requirements. Acad Med. 2021;96(6):828–835. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutter ME, Simmons VN, Sutton SK, Vadaparampil ST, Sanchez JA, Bowman-Curci M, et al. Oncologists’ experiences caring for LGBTQ patients with cancer: qualitative analysis of items on a national survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(4):871–876. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudson J, Schabath MB, Sanchez J, Sutton S, Simmons VN, Vadaparampil ST, et al. Sexual and gender minority issues across NCCN guidelines: results from a national survey. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(11):1379–1382. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voyles CH, Sell RL. Continued disparities in lesbian, gay, and bisexual research funding at NIH. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 3):e1. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris M, Cooper RL, Ramesh A, et al. Training to reduce LGBTQ-related bias among medical, nursing, and dental students and providers: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:325. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1727-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seay J, Hicks A, Markham MJ, Schlumbrecht M, Bowman-Curci M, Woodard J, et al. Web-based LGBT cultural competency training intervention for oncologists: pilot study results. Cancer. 2020;126(1):112–120. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kano M, tami-Maury I, Sanchez NF, Chang S (2022) (eds) Sexual and gender minority cancer special issue. Annals of LGBTQ Public and Population Health 3(1–2). 10.1891/LGBTQ-2021-0034