Abstract

Oxyluciferin, which is the light emitter for firefly bioluminescence, has been subjected to extensive chemical modifications to tune its emission wavelength and quantum yield. However, the exact mechanisms for various electron-donating and withdrawing groups to perturb the photophysical properties of oxyluciferin analogs are still not fully understood. To elucidate the substituent effects on the fluorescence wavelength of oxyluciferin analogs, we applied the absolutely localized molecular orbitals (ALMO)-based frontier orbital analysis to assess various types of interactions (i.e. permanent electrostatics/exchange repulsion, polarization, occupied-occupied orbital mixing, virtual-virtual orbital mixing, and charge-transfer) between the oxyluciferin and substituent orbitals. We suggested two distinct mechanisms that can lead to red-shifted oxyluciferin emission wavelength, a design objective that can help increase the tissue penetration of bioluminescence emission. Within the first mechanism, an electron-donating group (such as an amino or dimethylamino group) can contribute its highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to an out-of-phase combination with oxyluciferin’s HOMO, thus raising the HOMO energy of the substituted analog and narrowing its HOMO-LUMO gap. Alternatively, an electron-withdrawing group (such as a nitro or cyano group) can participate in an in-phase virtual-virtual orbital mixing of fragment LUMOs, thus lowering the LUMO energy of the substituted analog. Such an ALMO-based frontier orbital analysis is expected to lead to intuitive principles for designing analogs of not only the oxyluciferin molecule, but also many other functional dyes.

Keywords: bioluminescence, fluorescence, substitution, time-dependent density functional theory, energy decomposition analysis

1. Introduction

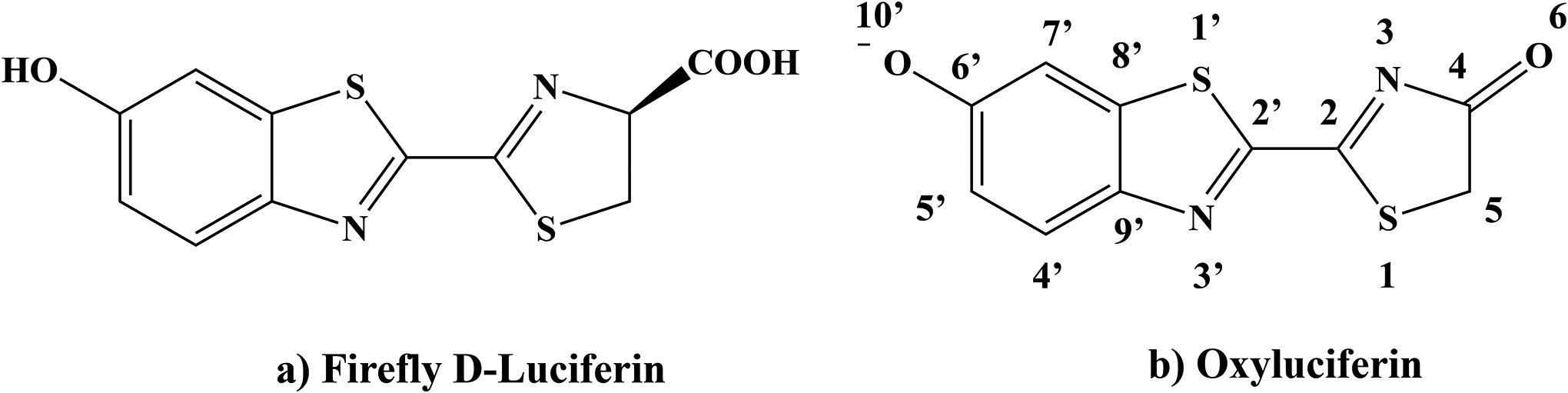

Firefly bioluminescence has fascinated the humankind for thousands of years, but it was not until the late 1950s[1] when the light-emitting process was found to arise from the luciferase enzyme and its natural substrate, which is now commonly called firefly luciferin. The substrate was first purified by Bitler and McElory[1] and then identified by White, McCapra, and Field[2, 3] to be D(−)-2-(6-hydroxy-2-benzothiazolyl)-Δ2-thiazoline-4-carboxylic acid (LUC, Fig. 1a). These efforts allowed them to propose a now widely-accepted bioluminescence mechanism that, in the belly of firefly beetles, the luciferase enzyme catalyzes a reaction of firefly oxyluciferin with ATP and O2 molecules to produce an electronically excited oxyluciferin anion (Fig. 1b), whose relaxation yields the characteristic green-yellow light emission.

Figure 1:

The chemical structures of firefly luciferin (LUC) and oxyluciferin (OLU).

While there were earlier suggestions that either the keto or enol tautomer of oxyluciferin might play a key role in the light emission, the scientific debate persists.[4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] In this work, we will focus on the keto-form of the oxyluciferin (OLU, Fig. 1b).

With firefly bioluminescence (fBL) assays routinely employed in biochemistry research, there is a constant push to shift the emission color from the common green-yellow to the red and near-infrared regions. Luminescence with a longer wavelength is less harmful and can penetrate much deeper into human/animal tissues due to reduced absorption from hemoglobin and other molecules in the tissue. There are two general approaches to modulate the fBL emission wavelengths: chemical modifications to the oxyluciferin fluorophore and environmental changes such as amino acid mutations of the luciferase enzyme.

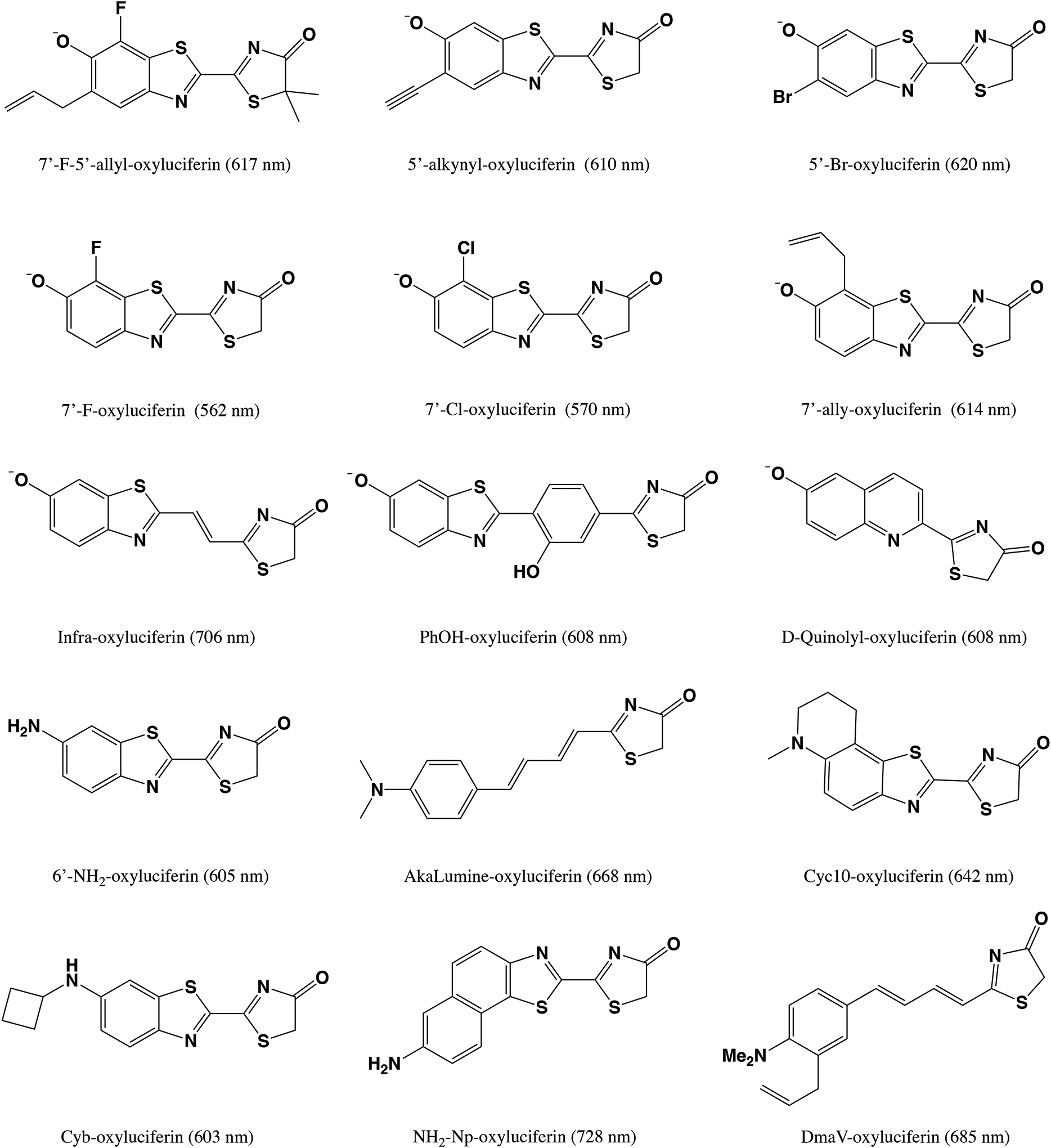

The oxyluciferin emitter can be modified in at least four ways to achieve a substantial red shift in the bioluminescence wavelength. Firstly, the C4’, C5’, and C7’ sites of the benzothiazole ring (see Fig. 1b) can be functionalized with one or more substituents, leading to analogs such as 7’-F-5’-allyl-oxyluciferin,[16] 5’-alkynyl-oxyluciferin,[17] 5’- and 7’-Br-oxyluciferin,[18, 16] 7’-Cl-oxyluciferin,[16] and 7’-allyl-oxyluciferin.[19] Secondly, a conjugated bridge (such as one or multiple double bonds or a conjugate ring) can be inserted between the benzothiazole and 4(5H)-thiazolone moieties to increase the conjugation length, leading to infra-oxyluciferin,[20] PhOH-Luc,[21] etc. Thirdly, the benzothiazole ring can be modified, with examples such as D-quinolyl-oxyluciferin.[22] Lastly, following the design of 6’-amino-oxyluciferin,[23] many other researchers have replaced the 6’-hydroxyl group with other linear or cyclic amino groups, leading to AkaLumine,[24, 25, 26] CycLuc10,[27, 28] Cyb-oxyluciferin,[28] NH2-Np-oxyluciferin,[29] and DmaV-oxyluciferin.[30]

An alternative approach to tune the bioluminescence emission wavelength is to genetically modify the luciferase enzyme.[31, 32, 33, 34, 35] This was inspired by the natural variation of bioluminescence emission colors:[36, 37, 38, 39] north American firefly Photinus pyralis (λem = 560 nm),[40] click beetle Pyrophorus plagiophthalamus (λem = 590 nm),[41] and railroad worm (λem = 630 nm),[42, 35, 43] all with the same oxyluciferin substrate. In the early 2000s, Branchini and coworkers developed a red-emitting (614 nm) mutant of Photinus pyralis luciferase.[33] Later, Kato and coworkers reported a mutant of Luciola cruciata luciferase, which emits in both yellow-green (560 nm) and red region (613 nm) using oxyluciferin as substrate.[31] Prescher and coworkers genetically engineered luciferases to facilitate the bioluminescence emission of the oxyluciferin analogs with C4’ and C7’ substituents. [44, 18, 45] More recently, Miyawaki and coworkers performed laboratory-directed evolution to develop mutated Akaluc luciferases that are most compatible with the AkaLumine luciferin substrate (shown in Fig. 2).[26] Naumov and coworkers provided a comprehensive review of the structural, biochemical, and photophysical properties of beetle bioluminescence in Phrixothrix hirtus.[35, 43]

Figure 2:

Selected oxyluciferin analogs and their bioluminescence wavelengths (in nm).[16, 17, 18, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 28, 29, 30] For PhOH-oxyluciferin, its bioluminescence wavelength was measured with the G2 mutant of luciferase.[21] The bioluminescence wavelength of NH2-Np-oxyluciferin was reported with the CBR2opt luciferase mutant.[29]

In this work, we will focus primarily on the modulation of the emission wavelength via chemical modifications to the oxyluciferin fluorophore. Specifically, we will perform computational modeling of the effect of substituent groups on the fluorophore. We note that computational studies have been performed by several research groups to elucidate bioluminescence mechanism[6, 12, 46, 47, 48, 49, 7, 50] as well as to design novel oxyluciferin analogs.[51, 52, 53, 54]

In 2014, Liu and coworkers reported TDDFT absorption and fluorescence wavelengths of oxyluciferin analogs where the 6’-hydroxyl group of the benzothiazole was replaced with electron-donating substituents.[51] In particular, OMe and N(CH3)2 caused a red-shift in the emission wavelength due to the hyperconjugation effect of the methyl groups, whereas N(CH3)CH=CH2 and N(C6H5)2 groups red-shifted the emission owing to the electron-donating conjugation effect. Later, Liu and coworkers carried out an even more comprehensive computational study of oxyluciferin analogs.[52] They reviewed eight classes of analogs and performed an elaborate screening based on their fluorescence wavelengths obtained from gas-phase TDDFT calculations. The most red-shifted oxyluciferin analog, which was called “star”, was then further analyzed in conjunction with wild-type luciferase and its mutants using QM/MM calculations. Most recently, Navizet and coworkers investigated Benzothiophene-Oxy (nitrogen atom replaced by a methine), Dihydropyrrolone-Oxy (sulfur atom replaced by methylene), and Allylbenzothiazole-Oxy (introduction of an allyl group to the C7’ site) analogs and probed the effects of these substitutions within the protein environment.[53] They reported a good agreement between experimental bioluminescence wavelengths of oxyluciferin analogs and the corresponding computed emission wavelengths based on QM/MM calculations. It has also been suggested by computational studies that some oxyluciferin analogs can serve as effective light-emitting materials in OLED applications. For instance, Min and coworkers replaced the benzothiazolyl ring of oxyluciferin with phenyl, anthryl, or pyrenyl rings and computed the excited-state properties of those analogs, [54] based on which they predicted that oxyluciferin analogs could emit with a variety of colors, such as blue, green, orange, and red.

Inspired by all these experimental and computational research on oxyluciferin analogs, we carried out this work to further elucidate the substituent effects on the oxyluciferin molecule. Specifically, we modified the OLU structure at three different sites, C7’, C5’, and C4’ in Fig. 1b, with 14 functional groups. These included several electron-donating groups with varying Hammett σp constant:[55] CHCH2(−0.04) > OH (−0.37) > NH2(−0.66) > NHCH3 (−0.70) > N(CH3)2 (−0.83). Also included were multiple electron-withdrawing groups: NO2(0.78) > CN(0.66) > CF3(0.54) > COCH3(0.50) > Br(0.23) ~ Cl(0.23) ~ CCH(0.23) > I(0.18) > F(0.06). Out of these compounds to be analyzed in this work, several have already been studied in the past. Urano and coworkers synthesized 7’-fluoro-oxyluciferin and 7’-chloro-oxyluciferin analogs.[16] The oxyluciferin analog with an alkynyl substituent at C5’ were developed and tested by Prescher and coworkers.[17] The same research group later also reported brominated oxyluciferin analogs using C4’, C5’, and C7’ sites.[18] In the aforementioned computational study by Liu and coworkers,[52] the effects of fluorine and hydroxyl groups at C4’ and C7’ positions of oxyluciferin structure were analyzed (See SI Table S11).[52] We also note that the nitro group by itself tends to quench fluorescence, but a nitro-functionalized OLU can serve as a useful precursor for imaging cellular locations and interactions.[56]

In our computational modeling, we assessed the effects of electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents on the excited-state properties of oxyluciferin analogs. In particular, the absolutely localized molecular orbitals (ALMO)-based analysis was carried out on selected mono-substituted oxyluciferin analogs to obtain a detailed picture of the interactions between substrate and substituent orbitals.[57] With the aid of such a fragment molecular orbital-based tool, we sought to unravel basic principles for the engineering of frontier orbitals of oxyluciferin analogs, which can potentially facilitate the design of a more effective bio-imaging toolkit.

2. Computational Methods and Details

2.1. Ground State and Excited State Calculations

All electronic ground-state calculations were performed using the density functional theory (DFT) method,[58, 59, 60] whereas excited-state calculations were carried out using the time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) method.[61, 62, 63] The calculations were performed with the qchem 5.0 software package.[64]

Functionals.

In the main text of this article, computational results (absorption/emission wavelengths and ALMO-based frontier orbital analysis) using the ωB97X-D functional [65] are presented. Three other density functionals (B3LYP,[66, 67, 68] M06–2X,[69] and CAM-B3LYP[70]) were also employed for TDDFT absorption wavelength calculations (See SI Tables S1–S4), among which CAM-B3LYP was also used for emission wavelength calculations (See SI Table S5).

Basis sets and integration grids.

Most of the DFT and TDDFT absorption/emission results were obtained using the 6–311++G** basis set [71] and the SG-1 numerical integration grid,[72] where the latter is a pruned (50, 194) grid [73] (50 radial shells with 194 Lebedev points in each). Additionally, several other basis sets, such as 6–311+G* and aug-cc-pVTZ,[74, 75] were used to compute TDDFT absorption wavelengths of oxyluciferin. As shown in the SI Table S6, relative to the 6–311++G** values, the absorption wavelength of oxyluciferin computed using the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set changed by no more than 2.0 nm. The effect of using a larger integration grid is also marginal, with the computed absorption wavelengths changing by no more than 0.1 nm between SG-1 [72] and a finer (99,590) grid [76] (Table S7). In ALMO-based frontier orbital analysis calculations, the 6–31G(d) basis set[77, 78] was employed.

Implicit solvent models.

In order to account for solvent effect on oxyluciferin anion, we used the polarizable continuum model (PCM) [79, 80] for water molecules, specifically the C-PCM [81, 82, 83] model as implemented in qchem using a smoothly-discretized solvent cavity (with Bondi radii and a scaling factor of 1.2).[84] For absorption energy calculations, ground-state geometry optimizations were carried out using C-PCM, and vertical excitation energies were then computed using TDDFT and the non-equilibrium linear-response C-PCM model.[85, 86, 87] As indicated by the results tabulated in the SI Table S8, the TDDFT absorption wavelengths obtained using C-PCM and IEF-PCM [88, 89] solvent models differed by only 2.3 nm, indicating the marginal difference between these two types of PCM models in capturing the solvation effect on TDDFT excitation energies. To obtain fluorescence emission wavelengths, we also optimized excited-state structures using TDDFT with equilibrium PCM. The solvatochromic effect of various implicit solvents on the absorption and emission wavelengths was also reported in SI Table S9. For example, the emission wavelength of OLU was computed to be 579.1 nm in water (ϵstatic: 78.3; ϵoptical: 1.78), which is a polar solvent. In contrast, a non-polar solvent such as benzene (ϵstatic: 2.27; ϵoptical: 2.25) yielded a blue shift in the emission wavelength (532 nm) of OLU. The effect of explicit water models on the absorption and emission spectra of the oxyluciferin molecule will be discussed in future publications.

Geometry optimization

The convergence criteria for ground state and excited state geometry optimizations were set to 3 × 10−4 a.u. for maximum force, 1.2 × 10−3 a.u. for maximum displacement, and 1.0 × 10−6 a.u. for energy change. The vibrational analyses were performed at the optimized ground-state geometries, which confirmed that these geometries are true minima on the corresponding potential energy surfaces. Different OH- and NHCH3-substituted OLU rotamers were considered and listed in the SI Fig. S1.

2.2. Absolutely-localized Frontier Orbital Analysis

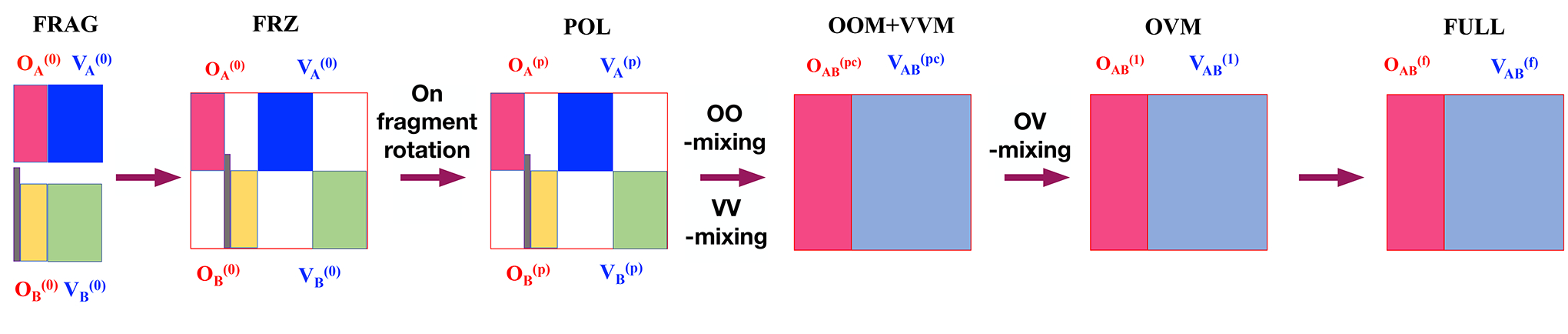

The ALMO-based energy decomposition analysis procedure[90, 91, 92, 93] was previously extended to handle covalently bonded molecular fragments, giving rise to an analysis scheme for substituent effects on the energy and composition of frontier molecular orbitals.[57] Most recently, some of us have employed this analysis tool to elucidate the underlying physics of frontier molecular orbital engineering involved in the design of thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) emitters. [94] Below, we will briefly summarize the procedure of this analysis (see Fig. 3 for a schematic illustration) as implemented within a development version of qchem 5.0.[64]

Figure 3:

ALMO-based scheme for analyzing substituent effects on fluorophore frontier orbitals. “A” and “B” denote the OLU and substituent fragments, respectively. The vertical bar in gray corresponds to the link C–X orbital between two fragments i.e., the single bond connecting the OLU core and the substituent. OA, OB correspond to the occupied orbitals of the fragments A and B respectively, whereas VA, VB correspond to the virtual orbitals of the fragments A and B respectively. OOM, VVM, and OVM correspond to the occupied-occupied mixing, the virtual-virtual mixing, and the occupied-virtual mixing respectively.

Fragment (FRAG) State:

Firstly, we divided a substituted oxyluciferin analog (OLU–Sub) into two fragments — the oxyluciferin core (OLU) and a substituent group (Sub) — to construct the “isolated” fragment orbitals. In order to have both fragments retain a closed-shell electronic structure, the main fragment, in this case, oxyluciferin, was saturated with a hydrogen link atom (Fragment A: OLU–H). Meanwhile, the substituent group was terminated with a phenyl ring (Fragment B: Sub–Ar). The molecular orbitals of each of these fragments were only allowed to be expanded in the atomic orbital basis functions located on the same fragment. After performing self-consistent field (SCF) calculations on each fragment, orbital localization was carried out to identify the localized C–Sub bond orbital (connecting the aryl group and the substituent group (in fragment B) as well as the localized OLU–H bond orbital (from fragment A). These two localized bond orbitals were then tailored and kept frozen during the subsequent SCF calculations on fragments A and B to obtain the other absolutely-localized fragment orbitals on OLU and Sub. For further details, we refer the reader to the Supplementary Information of Ref. 57.

Frozen (FRZ) State:

In order to account for the effects of permanent electrostatics and exchange-repulsion on frontier orbitals, two sets of fragment orbitals (with the OLU–H bond orbital removed) were combined together to obtain an idempotent one-particle density matrix. It is possible to further separate the permanent electrostatics and exchange-repulsion terms,[91] but this is not pursued in this work because our focus lies with the frontier orbitals.

Polarized (POL) State:

In this state, two sets of frozen fragment orbitals are allowed to polarize each other while restricted to stay absolutely-localized on their respective fragments. The orbital relaxations in this step thus include only occupied-virtual mixings within each fragment while leaving the C–Sub bond frozen.

OOM+VVM State:

Diagonalizing the non-vanishing occupied-occupied block of the Fock matrix within the basis of supersystem polarized orbitals, one can obtain the pseudocanonical occupied orbitals and their energies (see Eqs. 9 and 10 in Ref. 57). The occupied-occupied mixing can lead to an increase in the HOMO energy if a substantial out-of-phase combination of fragment occupied orbitals occurs. In order to rigorously capture the virtual-virtual orbital mixing effect, we diagonalize the corresponding block of the Fock matrix within the basis of projected virtual orbitals to obtain pseudocanonical virtual orbitals and their corresponding energies (see Eqs. 11–13 in Ref. 57). A substantial in-phase combination of fragment frontier virtual orbitals can result in a noticeable lowering in the LUMO energy.

OVM State:

After oo- and vv-mixing, a single diagonalization of the Fock matrix is performed to obtain mixing of occupied-virtual orbitals. This step causes a rearrangement of the electron density across the OLU and Sub fragments and potentially produces a net charge transfer. Unlike oo- and vv-mixing, the ov-mixing step can lower the HOMO energy and elevate the LUMO energy.

Full State:

In the final step after the OVM stage, the orbitals will be further relaxed to converge the energy to the absolute minimum obtained from standard DFT calculations. Fully converged orbitals can then be correlated to polarized occupied and virtual orbitals using Eqs. 14–15 in Ref. 57 to obtain orbital-interaction diagrams.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Computed Emission Wavelengths

For oxyluciferin analogs with a single substituent group attached at the C7’, C5’, or C4’ site, our computed emission wavelengths and oscillator strengths are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Computed emission wavelengths (λem, in nm) and oscillator strengths (f) of oxyluciferin and its analogs in aqueous solution at TD-ωB97X-D/6–311++G**/C-PCM level of theory. Substituent groups are ordered according to the wavelengths of the C7’-OLU analogs. Δλem is the difference between the computed emission wavelengths of the unsubstituted oxyluciferin and a substituted OLU analog.

| Group | site C7’ | site C5’ | site C4’ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ em | Δλem | f | λ em | Δλem | f | λ em | Δλem | f | |

| NO2 | 490.5 | −88.6 | 1.232 | 583.7 | 4.6 | 1.009 | 654.0 | 74.9 | 0.635 |

| CN | 517.7 | −61.4 | 1.279 | 564.6 | −14.5 | 1.204 | 587.4 | 8.3 | 1.164 |

| COCH3 | 519.5 | −59.6 | 1.288 | 589.7 | 10.6 | 1.165 | 598.2 | 19.1 | 1.158 |

| CF3 | 528.3 | −50.8 | 1.304 | 560.7 | −18.4 | 1.186 | 575.0 | −4.1 | 1.218 |

| I | 559.0 | −20.1 | 1.269 | 571.7 | −7.4 | 1.342 | 581.9 | 2.8 | 1.186 |

| CCH | 561.0 | −18.1 | 1.236 | 580.6 | 1.5 | 1.337 | 589.5 | 10.4 | 1.181 |

| Br | 561.1 | −18.0 | 1.267 | 569.6 | −9.5 | 1.325 | 579.0 | −0.1 | 1.191 |

| Cl | 563.7 | −15.4 | 1.266 | 568.0 | −11.1 | 1.303 | 577.9 | −1.2 | 1.192 |

| H | 579.1 | 0.0 | 1.270 | 579.1 | 0.0 | 1.270 | 579.1 | 0.0 | 1.270 |

| F | 584.2 | 5.1 | 1.230 | 563.2 | −15.9 | 1.297 | 571.2 | −7.9 | 1.200 |

| CHCH2 | 592.1 | 13.0 | 1.232 | 597.5 | 18.4 | 1.349 | 599.8 | 20.7 | 1.107 |

| OH-2 | 662.7 | 83.6 | 1.089 | 586.0 | 6.9 | 1.388 | 584.2 | 5.1 | 1.164 |

| OH | 665.8 | 86.7 | 1.007 | 574.1 | −5.0 | 1.383 | 579.7 | 0.6 | 1.174 |

| NH2 | 825.8 | 246.7 | 0.793 | 640.9 | 61.8 | 1.402 | 605.7 | 26.6 | 1.031 |

| N(CH3)2 | 882.0 | 302.9 | 0.719 | 645.3 | 66.2 | 1.428 | 608.4 | 29.3 | 1.048 |

| NCH3H | 888.5 | 309.4 | 0.741 | 651.6 | 72.5 | 1.384 | 596.4 | 17.3 | 0.993 |

| NHCH3 | 925.8 | 346.7 | 0.658 | 689.5 | 110.4 | 1.367 | 614.6 | 35.5 | 1.031 |

First, let us compare these wavelengths against available experimental values. Earlier, Urano and coworkers reported the fluorescence wavelength of 7’-F-oxyluciferin to be 540.0 nm, which is 10 nm longer than that of 7’-Cl-oxyluciferin (530 nm) in a basic medium (pH: 10.0).[16] Our TD-ωB97X-D calculations predicted slightly longer emission wavelengths of both analogs: 7’-F-oxyluciferin (584.2 nm) and 7’-Cl-oxyluciferin (563.7 nm), but with a correct trend regarding the spectral shift between the two analogs. In a separate work, Prescher and coworkers found the fluorescence wavelengths of C7’-, C5’-, and C4’-bromine substituted oxyluciferin to be comparable to that of D-luciferin.[18] From our TDDFT calculations, we also observed marginally blue-shifted bromo-oxyluciferin analogs: compared with the emission wavelength of unsubstituted oxyluciferin, the blue shift is 18.0 nm with bromination at C7’, 9.5 nm at C5’, and 0.1 nm at the C4’ site.

As a separate validation of TDDFT calculations on oxyluciferin analogs, we also computed the fluorescence wavelengths of seven C6’ oxyluciferin analogs in the PBS buffer and compared them to the experimental results reported by Miller and coworkers [95] (see SI Table S10). SI Fig. S2B shows a good correlation (R2 = 0.973; y = 0.992x − 0.258) between our computed TDDFT emission wavelengths and the experimental values.

Together, these comparisons confirmed that TDDFT is able to reliably predict spectral shifts of substituted oxyluciferin analogs.

3.1.1. Site C7’

Upon their attachment to the C7’ site, most substituent groups were predicted to cause a substantial shift in the emission wavelength of the chromophore (Table 1 and Fig. 4). Moreover, the spectral shift was strongly correlated with the electron-donating or withdrawing capability of each substituent group, as measured by the Hammett σp constants.

Figure 4:

Computed emission wavelengths (λem) of C7’-functionalized oxyluciferin analogs versus the Hammett σp constants of the corresponding substituent groups. Emission wavelengths were obtained from TD-ωB97X-D/6–311++G**/C-PCM calculations.

Among the electron-donating groups, the 7’-NH2 group was predicted to yield an emission wavelength of 825.8 nm, which amounted to a substantial red-shift of 246.7 nm from that of OLU. Even longer wavelengths were obtained for 7’-NCH3H-oxyluciferin (888.5 nm), its 7’-NHCH3-oxyluciferin conformer (925.8 nm, with the methyl group pointing away from the 6’-oxygen atom), and 7’-N(CH3)2-oxyluciferin (882.0 nm). In these molecules, the methyl group(s) affected the electronic structure mainly through hyperconjugation (see Fig. S10), namely the methyl group(s) of NHCH3 and N(CH3)2 directly contributed p-like orbitals to the HOMO of the modified chromophores. Specifically, due to the out-of-phase combinations between these p-like orbitals and the HOMO of 7’-amino-OLU, the HOMO energy of the full system got further raised from −6.1715 eV (the 7’-NH2 analog) to −6.0137 eV (the 7’-NHCH3 or NCH3H analog) or −6.0027 eV (the 7’-N(CH3)2 analog), thus narrowing the HOMO-LUMO gap and causing a red shift in the emission wavelength (See SI Fig. S10). Unlike these nitrogen-based electron-donating groups, a smaller red shift was obtained for the 7’-hydroxyl analog (662.7 nm and 665.8 nm), which has two conformers (OH and OH–2) with the H atom pointing away from the 6’–oxygen atom in the latter conformation, as well as the 7’-vinyl analog (592.1 nm). This trend in the emission wavelength can be traced to the relatively lower HOMO energies of these two oxyluciferin analogs, −6.5797 eV and −6.6096 eV, respectively.

In contrast, the attachment of electron-withdrawing groups (except for the fluorine substituent) resulted in blue-shifted emission peaks. The 7’-NO2-oxyluciferin analog was found to have the shortest emission wavelength of 490.5 nm. The CN and COCH3 groups at the C7’ site of oxyluciferin yielded emission wavelengths of 517.7 nm and 519.5 nm, respectively, and a slightly longer emission wavelength (528.3 nm) was predicted for the 7’-CF3-oxyluciferin analog. The effect of all four halogens was predicted to be marginal: the I-analog (559.0 nm), Br-analog (561.1 nm), and Cl-analog (563.7 nm) displayed a blue shift of 20.1 nm, 18.0 nm, and 15.4 nm in the oxyluciferin emission spectra, respectively, while the analog with C7’-fluorine substitution (584.2 nm) was predicted to have an emission peak slightly red-shifted by 5.1 nm compared to that of unsubstituted oxyluciferin.

To interpret the emission wavelength shifts caused by these groups, one might consider the charge-transfer (CT) character of the S1 state of the unsubstituted oxyluciferin anion.[10, 96] As shown in Fig. 5, upon the S0 → S1 excitation of the oxyluciferin anion, the net electrostatic potential fitted (ESP) charge transfer (from the benzothiazole ring to the 4(5H)-thiazolone ring) was predicted to be 0.236 e− with TD-ωB97X-D calculations. Intuitively, one would have expected an electron-donating/withdrawing group on the benzothiazole ring to facilitate/hinder the charge transfer to the 4(5H)-thiazolone ring during the S0 → S1 transition, thus reducing/increasing the excitation energy. However, this is not supported by Table S12, where the computed net changes in the Mulliken and ESP charges of the 4(5H)-thiazolone ring of oxyluciferin analogs upon the S0 → S1 transition are shown to be uncorrelated with the electron-donating or withdrawing capabilities of various groups.

Figure 5:

ESP charges for the S1 (top panel) and S0 (bottom panel) states obtained from TD-ωB97X-D/6–311++G**/C-PCM calculations. The relaxed electron density matrix was employed to calculate the ESP charges for the S1 state.

3.1.2. Site C5’

In contrast to the C7’ site, most of the electron-donating and withdrawing groups had a much smaller impact on the emission wavelengths of OLU when attached to the C5’ site. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 6, there is no apparent correlation between the computed emission wavelengths and the Hammett σp constants of the substituents. Out of all substituent groups, only the amino-based electron-donating groups have a noticeable effect on the emission wavelength of C5’–analogs. For instance, The 5’-NHCH3-oxyluciferin analog was found to have the longest emission wavelength of 689.5 nm. Its 5’-NCH3H conformer yielded a shorter emission wavelength of 651.6 nm. Similarly, functionalization with the N(CH3)2 and NH2 groups resulted in red-shifted oxyluciferin analogs emitting at 645.3 nm and 640.9 nm, respectively. The substitution effect of all other electron-donating substituents at the C5’ site of oxyluciferin was marginal. For instance, the 5’-(OH)-oxyluciferin analog (574.1 nm) caused a slight blue shift of 5.0 nm compared to oxyluciferin, whereas its another conformer 5’-(OH-2)-oxyluciferin resulted in a red-shift of 6.9 nm. The emission wavelength of the 5’-vinyl-oxyluciferin analog was predicted to be 597.5 nm, which is 18.4 nm longer than that of the OLU anion.

Figure 6:

Computed emission wavelengths (λem) of C5’-functionalized oxyluciferin analogs versus the Hammett σp constants of the corresponding substituent groups. Emission wavelengths were obtained from TD-ωB97X-D/6–311++G**/C-PCM calculations.

Similarly, unlike the effects of having electron-withdrawing groups at C7’, substitution by these groups at the C5’ site did not cause a significant blue shift in the emission spectra. The substitution of CN and CF3 groups at the C5’ site resulted in marginally blue-shifted oxyluciferin analogs emitting at 564.6 nm and 560.7 nm, respectively. The substitution of all halogens (F, Cl, Br, and I) at the C5’ site also resulted in slightly blue-shifted analogs. On the other hand, the C5’-substituted analogs such as 5’-CH3CO-oxyluciferin (589.7 nm), 5’-NO2-oxyluciferin (583.7 nm), and 5’-ethynyl-oxyluciferin (580.6 nm) actually led to a small red shift (10.6 nm, 4.6 nm, and 1.5 nm, respectively) in the emission wavelengths.

Clearly, these predicted variations in emission wavelengths, which are somewhat irregular, also cannot be explained based on how the charge transfer associated with the S0 →S1 transition of the oxyluciferin anion is facilitated or hindered by these substituents.

3.1.3. Site C4’

Similar to the case of site C5’, there also lacks a clear correlation between the emission wavelengths and Hammett σp constants for C4’-analogs (see Fig. 7). The addition of electron-donating groups, such as NHCH3, N(CH3)2, and NH2 to the C4’ site of oxyluciferin resulted in computed emission wavelengths in the red to orange region at 614.6/596.4 nm, 608.4 nm, and 605.7 nm, respectively. The 4’-OH-oxyluciferin (584.2 nm) and 4’-(OH-2)-oxyluciferin (579.7 nm) analogs displayed even smaller red shifts (5.1 and 0.6 nm) relative to the oxyluciferin anion. The oxyluciferin analog with a C4’-vinyl group was predicted to emit at 599.8 nm, which is 20.7 nm longer than the emission wavelength of OLU.

Figure 7:

Computed emission wavelengths (λem) of C4’-functionalized oxyluciferin analogs versus the Hammett σp constants of the corresponding substituent groups. Emission wavelengths were obtained from TD-ωB97X-D/6–311++G**/C-PCM calculations.

Very surprisingly, the 4’-nitro-oxyluciferin analog was also shown to produce a noticeably red-shifted emission wavelength of 654.0 nm. This is counterintuitive because, as shown in Table S12, an electron-withdrawing NO2 group on the C4’-site of benzothiazole ring hinders the net partial charge transfer from the benzothiazole ring to the 4(5H)-thiazolone ring (0.0682e − for 4-nitro-OLU versus 0.236 e− for OLU) during the S0 → S1 transition, which is presumably causing a blue shift.

Oxyluciferin analogs with a few other electron-withdrawing groups, such as 4’-CH3CO-oxyluciferin (598.2 nm), 4’-CN-oxyluciferin (587.4 nm), 4’-CCH-oxyluciferin (589.5 nm), and 4’-I-oxyluciferin (581.9 nm) also emit at slightly longer wavelengths than oxyluciferin. Meanwhile, other oxyluciferin analogs with electron-withdrawing groups, such as 4’-CF3-oxyluciferin (575.0 nm), 4’-F-oxyluciferin (571.2 nm), and 4’-Cl-oxyluciferin (577.9 nm), were found to be marginally blue-shifted.

Putting together the observations at the three sites, it is clear that the Hammett σp constants can be employed to explain the substituent effects on the spectroscopic properties of a few selected oxyluciferin analogs (mostly C7’-analogs) but become less effective for C5’ and C4’ analogs. This observation also holds for absorption wavelengths computed using various functionals (Figs. S1–S4) and emission wavelengths with the CAM-B3LYP functional (Fig. S5). Most intriguingly, the red shift caused by the electron-withdrawing NO2 group in C4’-nitro-oxyluciferin cannot be rationalized based on the empirical Hammett constants. To shed light on this, below we will pursue an analysis of the frontier orbitals of oxyluciferin analogs.

3.2. Frontier Orbital Analysis

3.2.1. Correlation Between HOMO–LUMO Gap and Emission Wavelength

For oxyluciferin and its analogs, the HOMO–LUMO transition dominates the TDDFT S1 → S0 emission. Specifically, the amplitude for HOMO→LUMO excitation was computed to be 0.985 for the unsubstituted oxyluciferin anion. Among the analogs, the smallest HOMO→LUMO amplitudes of 0.981 were obtained for C7’-CCH−, C7’-CHCH2−, C7’-CN−, and C7’-CH3CO-oxyluciferin analogs, whereas the largest amplitudes of 0.989 were found for the C4’-NO2−, C7’-NHCH3−, and C7’-NHCH3 oxyluciferin analogs (See SI Tables S13–S15).

Given such dominance by the HOMO→LUMO excitation, we plotted the computed HOMO-LUMO gaps (converted to nm) of oxyluciferin analogs and their emission wavelengths in Fig. 8A. A significant correlation (R2 = 0.962) between the HOMO–LUMO gaps and emission wavelengths was observed when the ωB97X-D functional was used. Similarly, the computed HOMO-LUMO gaps using the CAM-B3LYP functional also exhibited a remarkable correlation (R2 = 0.967) with the emission wavelengths (SI Figs. S8–S9). This suggests that, in order to interpret the shifts in the emission wavelengths among various oxyluciferin analogs, it would be beneficial to understand the variation in their HOMO-LUMO gaps.

Figure 8:

(A) HOMO-LUMO gaps (converted to nm) vs. TDDFT emission wavelengths (in nm) of oxyluciferin analogs. (B) HOMO and LUMO orbital contours for oxyluciferin and selected analogs. All results were collected from ωB97X-D/6–311++G**/C-PCM(water) calculations.

Below we shall focus on the effects of NH2 and NO2 groups, both as representative substituents, at the C7’/C5’/C4’ sites of oxyluciferin. As shown in Fig. 8B, the incorporation of the NH2 group at the C7’ site of oxyluciferin reduced the HOMO-LUMO gap from 5.521 to 4.757 eV. Moreover, such a narrowing of 0.764 eV of the gap was caused mostly by the elevation of the HOMO energy by 0.710 eV (from −6.882 to −6.172 eV), while the LUMO energy was lowered marginally by 0.054 eV (from −1.361 to −1.415 eV). In contrast, the attachment of the NO2 group to the C7’-site increased the HOMO-LUMO gap from 5.521 eV to 6.014 eV. The nitro group caused a widening of the HOMO-LUMO gap by 0.493 eV by lowering the HOMO energy by 0.612 eV and the LUMO energy by only 0.119 eV. Surprisingly, when NO2 group was placed at the C4’ site, the HOMO-LUMO gap got reduced by 0.291 eV. For that analog, both HOMO and LUMO were lowered in their energy, but it was the latter (LUMO) that was subjected to a larger shift of −0.503 eV.

This brings up some intriguing questions:(a) how do the amino group orbitals interact with the fluorophore to raise the HOMO energy? (b) why do the nitro group have the opposite effect, namely lowering LUMO energy? and (c) what is causing the aforementioned dramatically different effects upon the attachment of the nitro group at C4’ and C7’ sites? This calls for a qualitative analysis of the underlying interactions between fluorophore and substituent orbitals, which will be provided in the next two subsections within the framework of ALMO analysis as described in Section 2.2 and illustrated in Fig. 3.

3.2.2. Effect of amino group on three sites of OLU

Within the ALMO analysis, the FRZ, POL, and OVM intermediate states all provide a variational upper bound to the FULL SCF energy. The total polarization energy (i.e., the difference between the FRZ and POL states) varied from −2.4 kcal/mol for C4’-, −2.9 kcal/mol for C5’-, to −3.3 kcal/mol for C7’-amino substitution. This suggests that the amino group does not significantly stabilize the analogs through the polarization effect at the three sites. As shown in Fig. 9, the difference between the HOMO energies in the FRAG state and FRZ state is marginal for all three amino-substituted analogs, indicating that the effect of permanent electrostatic/Pauli repulsion is not significant between the amino group and oxyluciferin. Shape-wise, HOMOs and LUMOs of these three analogs remained essentially the same in the FRAG, FRZ, and POL states.

Figure 9:

Effect of the amino group on the HOMO and LUMO of oxyluciferin when attached to the C7’ (panel A), C5’ (panel B), and C4’ (panel C) sites. All results were collected from ALMO-based analysis using the ωB97X-D functional and 6–31G(d) basis set. The orbital energy values were reported in eV. The energies of the intermediate states relative to the full SCF energy of each analog were shown in the parentheses.

As shown in Fig. 9, the extension of both orbitals to the amino group occurred, if at all, through oo-mixing. Specifically, in the case of C7’- and C5’-amino substitutions, the HOMO energy was increased when moving from the POL state to the OOM+VVM state by 0.752 eV (−2.478 vs −3.230 eV) and 0.437 eV (−2.816 vs −3.253 eV), respectively. After such a large increase in the HOMO energy due to oo-mixing, the HOMO energy converges further to the FULL state through ov-mixing. In contrast to the significant changes in HOMO energies associated with the C7’- and C5’-amino analogs, the HOMO energy of the C4’-amino-oxyluciferin only changed minimally (< 0.05 eV) from the POL state to the OOM+VVM state.

On the other hand, the LUMOs and their energies did not change dramatically across the entire ALMO analysis procedure for all three amino-substituted oxyluciferin fluorophores. In the case of C5’- and C4’-amino substitutions, the LUMO energy increased by roughly 0.158 and 0.154 eV, respectively, due to vv-mixing. Meanwhile, the LUMO energy only increased by 0.043 eV for C7’-amino substitution.

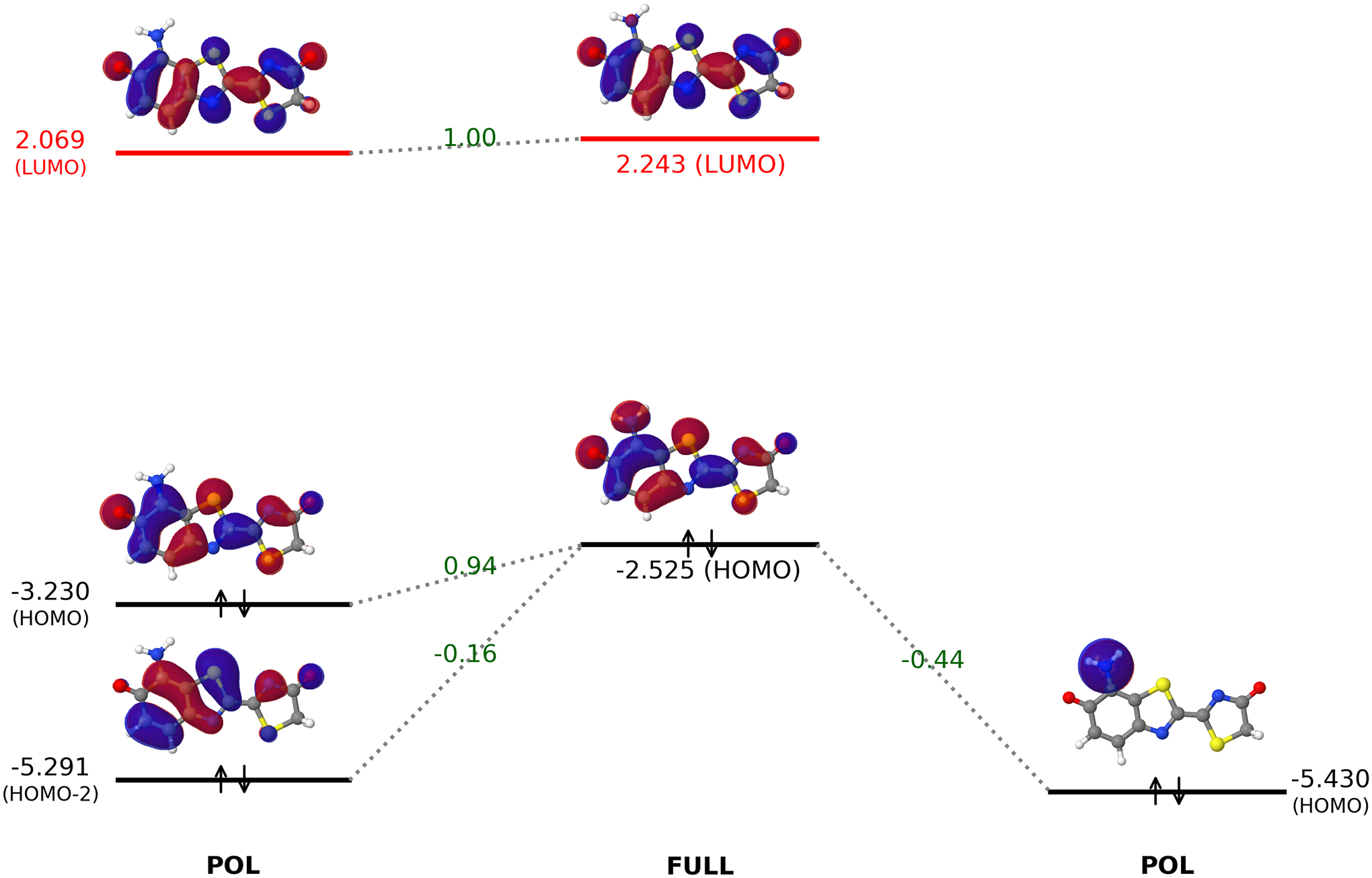

To further understand the effect of amino groups on the oxyluciferin substrate, we projected the frontier orbitals of the fully-converged frontier orbitals of C7’-amino-oxyluciferin onto the absolutely-localized polarized fragment orbitals. In Fig. 10, the interactions between polarized amino and oxyluciferin fragment orbitals that give rise to the full-system HOMO and LUMO were shown along with the corresponding projection coefficients. Clearly, the amino group HOMO undergoes an out-of-phase mixing with the oxyluciferin occupied orbitals (HOMO and HOMO-2), which led to an overall increase in the full-system HOMO energy. As such, a destructive (i.e. antibonding-like) interaction of the HOMO of a fluorophore with the highest occupied orbital of an electron-donating group is the key to the elevation of the HOMO energy.

Figure 10:

Interactions between the polarized oxyluciferin and amino group orbitals to yield the fully converged MOs of 7’-amino-oxyluciferin. The calculations for orbital interaction analysis were performed in the gas–phase using the ωB97X-D/6–31G(d) level of theory. All orbital energies are in eV.

The impact of occupied-occupied orbital mixing on the HOMO-LUMO gap of amino-substituted OLU analogs is more compactly shown in the first column of Fig. 11. Clearly, the strength of the net impact follows the order C7’ > C5’ > C4’, which coincides with the weight of their respective carbon atomic orbitals within the OLU HOMO. Namely, the OLU HOMO, as shown in Figs. 9 and 10, receives the largest contribution from C7’-carbon, followed by C5’-carbon, while C4’-carbon has the smallest contribution. Accordingly, the HOMO energy is raised the most with the C7’-amino group and the least with the C4’-amino group.

Figure 11:

Decomposition of the effects of the amino, methylamino, acetyl, cyano, and nitro groups on the HOMO and LUMO of the oxyluciferin analogs obtained from the ALMO-based analysis. All energy values (in eV) were acquired at the ωB97X-D/6–31G(d) level of theory.

To design new fluorophores featuring smaller HOMO-LUMO gaps, therefore, one should attach strong electron-donating groups to atoms where the HOMO has large weights.

3.2.3. Effect of nitro group on three sites of OLU

Unlike the amino group, the nitro group shifted the HOMO and LUMO energies substantially from the FRAG to the FRZ state. Specifically, the HOMO energy was lowered by 0.913, 0.658, and 0.564 eV, respectively, for C7’-, C5’-, and C4’-nitro-oxyluciferin, as shown in Fig. 12. Meanwhile, the LUMO energy was reduced by 0.413, 0.576, and 0.541 eV, respectively. Such a significant contribution from permanent electrostatics/Pauli repulsion was expected for the nitro substituent, which has a larger dipole moment due to the presence of two electronegative oxygen atoms.

Figure 12:

Effect of the nitro group on the HOMO and LUMO of oxyluciferin when attached to the C7’ (panel A), C5’ (panel B), and C4’ (Panel C) sites. All results were collected from gas–phase ALMO-based calculations using the ωB97X-D functional and 6–31G(d) basis set. The orbital energy values were reported in eV. The energies of the intermediate states relative to the full SCF energy of each analog were shown in the parentheses.

For C7’-nitro substitution, the HOMO energy was raised from −4.102 eV (FRZ) to −3.787 eV (POL) due to the polarization interaction. From this point onward, the HOMO energy gradually shifted back to the full-SCF value of −3.996 eV. Even smaller polarization effect on the HOMO energy was observed for C4’ and C5’-nitro-substituted analogs (−3.804 →−3.698 eV and −3.610 → −3.509 eV, respectively).

As far as the LUMO is concerned, the largest virtual-virtual mixing occurred on the C4’-nitro-oxyluciferin analog, where the LUMO energy was reduced by 0.341 eV (1.914 → 1.573 eV). This is the primary cause for the narrowing of the HOMO-LUMO gap of this analog. In contrast, nitro groups at the C7’ and C5’ sites reduced the LUMO energy by only 0.023 and 0.112 eV, respectively, through vv-mixing. The LUMOs then remained more or less constant after the oo- and vv-mixing stage.

The orbital interaction analysis shown in Fig. 13 revealed that the LUMO+1 orbital of the nitro group was combined with OLU’s LUMO and LUMO+2. The resultant virtual orbital has a lower energy due to the constructive (i.e. bonding-like) combination. Among the three sites, the C4’-carbon is shown in Figs. 12 and 13 to have the most substantial contribution to the isolated (and polarized) fluorophore LUMO and thus lowered the LUMO energy the most. The corresponding vv-mixing then caused the most significant reduction to the HOMO-LUMO gap, as shown in the last column of Fig. 11 and in Fig. 12. Therefore, in order to lower the LUMO energy in frontier molecular orbital engineering, one can attach strong electron-withdrawing groups with unoccupied π* orbitals to sites where the LUMO has large weights.

Figure 13:

Interaction between the polarized oxyluciferin and nitro group orbitals to produce fully converged MOs of 4’-nitro-oxyluciferin. The calculations for orbital interaction analysis were performed at the ωB97X-D/6–31G(d) level of theory. All orbital energies are in eV.

In Fig. 11, in addition to NH2 and NO2 groups, the substituent effects of another electron-donating group, NHCH3, and two other electron-withdrawing groups, COCH3 and CN are shown. Consistent with the predicted emission wavelength results (with a larger basis set and C-PCM solvation model) in Sec. 3.1, the NHCH3 group at the C7’ site substantially narrowed the HOMO-LUMO gap, while smaller changes were observed for the HOMO-LUMO gaps in other cases. The corresponding orbital evolution and interaction analysis diagrams for 7’-NHCH3-OLU and 4’-COCH3-OLU can be found in SI Figs. S11–S12 and S13–S14 respectively.

4. Conclusions

Through a systematic computational study of oxyluciferin analogs with substituent groups at C7’, C5’, and C4’-sites, we found that

Substitution of EDGs (such as NH2, NHCH3, OH groups) at the C7’ position of OLU caused a red shift in the computed emission wavelength, while EWGs (such as NO2 and CN groups) blue-shifted the emission wavelength. There was a strong correlation between the Hammett parameters σp and computed λem for the C7’-OLU analogs.

There was no correlation between σp and computed λem for the C4’- and C5’-OLU analogs. Most surprisingly, the OLU analog with the NO2 group at the C4’ position was predicted to emit at a significantly longer wavelength (by 74.9 nm) compared to that of OLU.

The oo-mixing between the HOMO of the OLU core and the high-lying occupied orbitals of EDGs (such as an amino group) raised the HOMO level and significantly reduced the HOMO-LUMO gap. On the other hand, the vv-mixing between OLU’s LUMO and the lowest-lying virtual orbitals of EWGs (such as a nitro group) lowered the LUMO level and also caused a red-shifted emission.

To summarize, the overall design strategies for fluorophores with red-shifted emission wavelengths are: strong electron-donating groups (such as amino and dimethylamino groups) can be attached to sp2 carbon atoms with a substantial contribution to the fluorophore HOMO, whereas strong electron-withdrawing groups (such nitro and cyano groups) to carbon atoms with a considerable LUMO contribution.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgement

We thank Drs. Yajun Liu, Peng Tao, Zheng Pei, and Shushu Zhang for helpful discussions. YS was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant No. R01GM135392) and the Office of the Vice President of Research and the College of Art and Sciences at the University of Oklahoma (OU). EB expresses his gratitude to NSU and 5-100 Excellence Programme of Russian Ministry of Science and Education. The authors thank the OU Supercomputing Center for Education & Research (OSCER) for the computational resources.

Contributor Information

Vardhan Satalkar, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA.

Enrico Benassi, Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk, 630090, Russia.

Yuezhi Mao, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Xiaoliang Pan, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA.

Chongzhao Ran, Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, Boston, MA 02129, USA.

Xiaoyuan Chen, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine and Faculty of Engineering, National University of Singapore, 117597, Singapore.

Yihan Shao, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA.

References

- [1].Bitler B and McElroy W, “The preparation and properties of crystalline firefly luciferin”, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 72(2), pp. 358 (1957). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].White EH, McCapra F, Field GF, and McElroy WD, “The structure and synthesis of firefly luciferin”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 83(10), pp. 2402 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- [3].White EH, McCapra F, and Field GF, “The structure and synthesis of firefly luciferin”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 85(3), pp. 337 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- [4].Branchini BR, Murtiashaw MH, Magyar RA, Portier NC, Ruggiero MC, and Stroh JG, “Yellow-green and red firefly bioluminescence from 5,5-dimethyloxyluciferin”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 124(10), pp. 2112 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Branchini BR, Southworth TL, Murtiashaw MH, Magyar RA, Gonzalez SA, Ruggiero MC, and Stroh JG, “An alternative mechanism of bioluminescence color determination in firefly luciferase”, Biochemistry 43(23), pp. 7255 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liu F, Liu Y, De Vico L, and Lindh R, “Theoretical study of the chemiluminescent decomposition of dioxetanone”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 131(17), pp. 6181 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Navizet I, Liu YJ, Ferré N, Xiao HY, Fang WH, and Lindh R, “Colortuning mechanism of firefly investigated by multi-configurational perturbation method”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 132(2), pp. 706 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hirano T, Hasumi Y, Ohtsuka K, Maki S, Niwa H, Yamaji M, and Hashizume D, “Spectroscopic Studies of the Light-Color Modulation Mechanism of Firefly (Beetle) Bioluminescence”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 131(6), pp. 2385 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Naumov P, Ozawa Y, Ohkubo K, and Fukuzumi S, “Structure and spectroscopy of oxyluciferin, the light emitter of the firefly bioluminescence”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 131(32), pp. 11590 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen SF, Liu YJ, Navizet I, Ferré N, Fang WH, and Lindh R, “Systematic theoretical investigation on the light emitter of firefly”, J. Chem. Theory Comput 7(3), pp. 798 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hosseinkhani S, “Molecular enigma of multicolor bioluminescence of firefly luciferase”, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 68(7), pp. 1167 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yue L, Liu YJ, and Fang WH, “Mechanistic insight into the chemiluminescent decomposition of firefly dioxetanone”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 134(28), pp. 11632 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pinto da Silva L, Simkovitch R, Huppert D, and Esteves da Silva JCG, “Oxyluciferin Photoacidity: The Missing Element for Solving the Keto-Enol Mystery?”, ChemPhysChem 14(15), pp. 3441 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cheng YY and Liu YJ, “What exactly is the light emitter of a firefly?”, J. Chem. Theory Comput 11(11), pp. 5360 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Berraud-Pache R, Garcia-Iriepa C, and Navizet I, “Modeling Chemical Reactions by QM/MM Calculations: The Case of the Tautomerization in Fireflies Bioluminescent Systems”, Front. Chem 6, pp. 116 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Takakura H, Kojima R, Ozawa T, Nagano T, and Urano Y, “Development of 5’- and 7’-substituted luciferin analogues as acid-tolerant substrates of firefly luciferase”, ChemBioChem 13(10), pp. 1424 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Steinhardt RC, O’Neill JM, Rathbun CM, McCutcheon DC, Paley MA, and Prescher JA, “Design and synthesis of an alkynyl luciferin analogue for bioluminescence imaging”, Chem. Eur. J 22(11), pp. 3671 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Steinhardt RC, Rathbun CM, Krull BT, Yu JM, Yang Y, Nguyen BD, Kwon J, McCutcheon DC, Jones KA, Furche F, and Prescher JA, “Brominated luciferins are versatile bioluminescent probes”, ChemBioChem 18(1), pp. 96 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ikeda Y, Saitoh T, Niwa K, Nakajima T, Kitada N, Maki SA, Sato M, Citterio D, Nishiyama S, and Suzuki K, “An allylated firefly luciferin analogue with luciferase specific response in living cells”, Chem. Commun 54(14), pp. 1774 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jathoul AP, Grounds H, Anderson JC, and Pule MA, “A dual-color far-red to near-infrared firefly luciferin analogue designed for multiparametric bioluminescence imaging”, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 53(48), pp. 13059 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yao Z, Zhang BS, Steinhardt RC, Mills JH, and Prescher JA, “Multicomponent bioluminescence imaging with a π-extended luciferin”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 142(33), pp. 14080 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Branchini BR, “Chemical synthesis of firefly luciferin analogs and inhibitors”, Meth Enzymol 305, pp. 188 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].White EH, Wörther H, Seliger HH, and McElroy WD, “Amino analogs of firefly luciferin and biological activity thereof”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 88(9), pp. 2015 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- [24].Iwano S, Obata R, Miura C, Kiyama M, Hama K, Nakamura M, Amano Y, Kojima S, Hirano T, Maki S, and Niwa H, “Development of simple firefly luciferin analogs emitting blue, green, red, and near-infrared biological window light”, Tetrahedron 69(19), pp. 3847 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kiyama M, Iwano S, Otsuka S, Lu SW, Obata R, Miyawaki A, Hirano T, and Maki SA, “Quantum yield improvement of red-light-emitting firefly luciferin analogues for in vivo bioluminescence imaging”, Tetrahedron 74(6), pp. 652 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [26].Iwano S, Sugiyama M, Hama H, Watakabe A, Hasegawa N, Kuchimaru T, Tanaka KZ, Takahashi M, Ishida Y, Hata J, Shimozono S, Namiki K, Fukano T, Kiyama M, Okano H, Kizaka-Kondoh S, McHugh TJ, Yamamori T, Hioki H, Maki S, and Miyawaki A, “Single-cell bioluminescence imaging of deep tissue in freely moving animals”, Science 359(6378), pp. 935 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mofford DM, Reddy GR, and Miller SC, “Aminoluciferins extend firefly luciferase bioluminescence into the near-infrared and can be preferred substrates over d-luciferin”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 136(38), pp. 13277 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wu W, Su J, Tang C, Bai H, Ma Z, Zhang T, Yuan Z, Li Z, Zhou W, Zhang H, Liu Z, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Du L, Gu L, and Li M, “CybLuc: an effective aminoluciferin derivative for deep bioluminescence imaging”, Anal. Chem 89(9), pp. 4808 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hall MP, Woodroofe CC, Wood MG, Que I, van’t Root M, Ridwan Y, Shi C, Kirkland TA, Encell LP, Wood KV, Löwik C, and Mezzanotte L, “Click beetle luciferase mutant and near infrared naphthyl-luciferins for improved bioluminescence imaging”, Nat. Commun 9(1), pp. 132 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kitada N, Saitoh T, Ikeda Y, Iwano S, Obata R, Niwa H, Hirano T, Miyawaki A, Suzuki K, Nishiyama S, and Maki SA, “Toward bioluminescence in the near-infrared region: tuning the emission wavelength of firefly luciferin analogues by allyl substitution”, Tetrahedron Lett 59(12), pp. 1087 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nakatsu T, Ichiyama S, Hiratake J, Saldanha A, Kobashi N, Sakata K, and Kato H, “Structural basis for the spectral difference in luciferase bioluminescence”, Nature 440(7082), pp. 372 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pozzo T, Akter F, Nomura Y, Louie AY, and Yokobayashi Y, “Firefly luciferase mutant with enhanced activity and thermostability”, ACS Omega 3(3), pp. 2628 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Branchini BR, Southworth TL, Khattak NF, Michelini E, and Roda A, “Red- and green-emitting firefly luciferase mutants for bioluminescent reporter applications”, Anal. Biochem 345(1), pp. 140 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Branchini BR, Ablamsky DM, Murtiashaw MH, Uzasci L, Fraga H, and Southworth TL, “Thermostable red and green light-producing firefly luciferase mutants for bioluminescent reporter applications”, Anal. Biochem 361(2), pp. 253 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Carrasco-López C, Ferreira JC, Lui NM, Schramm S, Berraud-Pache R, Navizet I, Panjikar S, Naumov P, and Rabeh WM, “Beetle luciferases with naturally red- and blue-shifted emission”, Life Sci. Alliance 1(4), pp. e201800072 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zinn KR, Chaudhuri TR, Szafran AA, O’Quinn D, Weaver C, Dugger K, Lamar D, Kesterson RA, Wang X, and Frank SJ, “Noninvasive bioluminescence imaging in small animals”, ILAR J 49(1), pp. 103 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gandelman OA, Church VL, Moore CA, Kiddle G, Carne CA, Parmar S, Jalal H, Tisi LC, and Murray JAH, “Novel bioluminescent quantitative detection of nucleic acid amplification in real-time”, PLoS ONE 5(11), pp. e14155 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Jathoul A, Law E, Gandelman O, Pule M, Tisi L, and Murray J, “Development of a pH-tolerant thermostable photinus pyralis luciferase for brighter in vivo imaging”, In Lapota D, editor, Bioluminescence:Recent Advances in Oceanic Measurements and Laboratory Applications. InTech (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [39].Branchini BR, Southworth TL, Fontaine DM, Davis AL, Behney CE, and Murtiashaw MH, “A photinus pyralis and luciola italica chimeric firefly luciferase produces enhanced bioluminescence”, Biochemistry 53(40), pp. 6287 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Conti E, Franks NP, and Brick P, “Crystal structure of firefly luciferase throws light on a superfamily of adenylate-forming enzymes”, Structure 4(3), pp. 287 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wood KV, Lam YA, and McElroy WD, “Introduction to beetle luciferases and their applications”, J. Biolumin. Chemilumin 4(1), pp. 289 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Viviani VR, Bechara EJH, and Ohmiya Y, “Cloning, sequence analysis, and expression of active Phrixothrix railroad-worms luciferases: relationship between bioluminescence spectra and primary structures”, Biochemistry 38(26), pp. 8271 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Carrasco-López C, Lui NM, Schramm S, and Naumov P, “The elusive relationship between structure and colour emission in beetle luciferases”, Nat. Rev. Chem 5(1), pp. 4 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Jones KA, Porterfield WB, Rathbun CM, McCutcheon DC, Paley MA, and Prescher JA, “Orthogonal luciferase–luciferin pairs for bioluminescence imaging”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 139(6), pp. 2351 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rathbun CM, Porterfield WB, Jones KA, Sagoe MJ, Reyes MR, Hua CT, and Prescher JA, “Parallel screening for rapid identification of orthogonal bioluminescent tools”, ACS Cent. Sci 3(12), pp. 1254 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Orlova G, Goddard JD, and Brovko LY, “Theoretical Study of the Amazing Firefly Bioluminescence: The Formation and Structures of the Light Emitters”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 125(23), pp. 6962 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Min CG, Ren AM, Guo JF, Zou LY, Goddard JD, and Sun CC, “Theoretical Investigation on the Origin of Yellow-Green Firefly Bioluminescence by Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory”, Chem. Eur. J. of Chem. Phys 11(10), pp. 2199–2204 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Milne BF, Marques MAL, and Nogueira F, “Fragment molecular orbital investigation of the role of AMP protonation in firefly luciferase pH-sensitivity”, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 12(42), pp. 14285 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].García-Iriepa C, Zemmouche M, Ponce-Vargas M, and Navizet I, “The role of solvation models on the computed absorption and emission spectra: the case of fireflies oxyluciferin”, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 21(8), pp. 4613 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Navizet I, Liu YJ, Ferré N, Roca-Sanjuán D, and Lindh R, “The Chemistry of Bioluminescence: An Analysis of Chemical Functionalities”, ChemPhysChem 12(17), pp. 3064 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cheng YY, Zhu J, and Liu YJ, “Theoretical tuning of the firefly bioluminescence spectra by the modification of oxyluciferin”, Chem. Phys. Lett 591, pp. 156 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cheng YY and Liu YJ, “Theoretical development of near-infrared bioluminescent systems”, Chem. Eur. J 24(37), pp. 9340 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Zemmouche M, García-Iriepa C, and Navizet I, “Light emission colour modulation study of oxyluciferin synthetic analogues via QM and QM/MM approaches”, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 22(1), pp. 82 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Min CG, Leng Y, Yang XK, Huang SJ, and Ren AM, “Systematic color tuning of a family of firefly oxyluciferin analogues suitable for OLED applications”, Dyes Pigm 126, pp. 202 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hansch C, Leo A, and Taft RW, “A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters”, Chem. Rev 91(2), pp. 165 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- [56].Porterfield WB, Jones KA, McCutcheon DC, and Prescher JA, “A “Caged” Luciferin for Imaging Cell–Cell Contacts”, J. Am. Chem. Soc 137(27), pp. 8656 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Mao Y, Head-Gordon M, and Shao Y, “Unraveling substituent effects on frontier orbitals of conjugated molecules using an absolutely localized molecular orbital based analysis”, Chem. Sci 9(45), pp. 8598 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Parr RG and Yang W, Density-functional theory of atoms and molecules, International series of monographs on chemistry. Oxford Univ. Press; New York, NY: (1994). [Google Scholar]

- [59].Burke K, “Perspective on density functional theory”, J. Chem. Phys 136(15), pp. 150901 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Becke AD, “Perspective: fifty years of density-functional theory in chemical physics”, J. Chem. Phys 140(18), pp. 18A301 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Casida ME, “Time-Dependent Density-Functional Response Theory for molecules”, In Recent Advances in Density Functional Methods Part I., p. 155. World Scientific; (1995). [Google Scholar]

- [62].Dreuw A and Head-Gordon M, “Single-reference ab initio methods for the calculation of excited states of large molecules”, Chem. Rev 105(11), pp. 4009 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Casida M and Huix-Rotllant M, “Progress in Time-Dependent Density-Functional Theory”, Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem 63(1), pp. 287 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Epifanovsky E, Gilbert ATB, Feng X, Lee J, Mao Y, Mardirossian N, Pokhilko P, White AF, Coons MP, Dempwolff AL, Gan Z, Hait D, Horn PR, Jacobson LD, Kaliman I, Kussmann J, Lange AW, Lao KU, Levine DS, Liu J, McKenzie SC, Morrison AF, Nanda KD, Plasser F, Rehn DR, Vidal ML, You ZQ, Zhu Y, Alam B, Albrecht BJ, Aldossary A, Alguire E, Andersen JH, Athavale V, Barton D, Begam K, Behn A, Bellonzi N, Bernard YA, Berquist EJ, Burton HGA, Carreras A, Carter-Fenk K, Chakraborty R, Chien AD, Closser KD, Cofer-Shabica V, Dasgupta S, de Wergifosse M, Deng J, Diedenhofen M, Do H, Ehlert S, Fang PT, Fatehi S, Feng Q, Friedhoff T, Gayvert J, Ge Q, Gidofalvi G, Goldey M, Gomes J, GonzálezEspinoza CE, Gulania S, Gunina AO, Hanson-Heine MWD, Harbach PHP, Hauser A, Herbst MF, Hernández Vera M, Hodecker M, Holden ZC, Houck S, Huang X, Hui K, Huynh BC, Ivanov M, Jász A, Ji H, Jiang H, Kaduk B, Kähler S, Khistyaev K, Kim J, Kis G, Klunzinger P, Koczor-Benda Z, Koh JH, Kosenkov D, Koulias L, Kowalczyk T, Krauter CM, Kue K, Kunitsa A, Kus T, Ladjánszki I, Landau A, Lawler KV, Lefrancois D, Lehtola S, Li RR, Li YP, Liang J, Liebenthal M, Lin HH, Lin YS, Liu F, Liu KY, Loipersberger M, Luenser A, Manjanath A, Manohar P, Mansoor E, Manzer SF, Mao SP, Marenich AV, Markovich T, Mason S, Maurer SA, McLaughlin PF, Menger MFSJ, Mewes JM, Mewes SA, Morgante P, Mullinax JW, Oosterbaan KJ, Paran G, Paul AC, Paul SK, Pavošević F, Pei Z, Prager S, Proynov EI, Rák A, Ramos-Cordoba E, Rana B, Rask AE, Rettig A, Richard RM, Rob F, Rossomme E, Scheele T, Scheurer M, Schneider M, Sergueev N, Sharada SM, Skomorowski W, Small DW, Stein CJ, Su YC, Sundstrom EJ, Tao Z, Thirman J, Tornai GJ, Tsuchimochi T, Tubman NM, Veccham SP, Vydrov O, Wenzel J, Witte J, Yamada A, Yao K, Yeganeh S, Yost SR, Zech A, Zhang IY, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zuev D, Aspuru-Guzik A, Bell AT, Besley NA, Bravaya KB, Brooks BR, Casanova D, Chai JD, Coriani S, Cramer CJ, Cserey G, DePrince AE, DiStasio RA, Dreuw A, Dunietz BD, Furlani TR, Goddard WA, Hammes-Schiffer S, Head-Gordon T, Hehre WJ, Hsu CP, Jagau TC, Jung Y, Klamt A, Kong J, Lambrecht DS, Liang W, Mayhall NJ, McCurdy CW, Neaton JB, Ochsenfeld C, Parkhill JA, Peverati R, Rassolov VA, Shao Y, Slipchenko LV, Stauch T, Steele RP, Subotnik JE, Thom AJW, Tkatchenko A, Truhlar DG, Van Voorhis T, Wesolowski TA, Whaley KB, Woodcock HL, Zimmerman PM, Faraji S, Gill PMW, Head-Gordon M, Herbert JM, and Krylov AI, “Software for the frontiers of quantum chemistry: An overview of developments in the Q-Chem 5 package”, J. Chem. Phys 155(8), pp. 084801 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Chai JD and Head-Gordon M, “Long-Range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom-atom dispersion corrections”, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 10(44), pp. 6615 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Becke AD, “Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior”, Phys. Rev. A 38(6), pp. 3098 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Becke AD, “A new mixing of Hartree-Fock and local density-functional theories”, J. Chem. Phys 98(2), pp. 1372 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lee C, Yang W, and Parr RG, “Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density”, Phys. Rev. B 37(2), pp. 785 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Zhao Y and Truhlar DG, “The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals”, Theor. Chem. Acc 120(1–3), pp. 215–241 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- [70].Yanai T, Tew DP, and Handy NC, “A new hybrid exchange–correlation functional using the Coulomb-Attenuating Method (CAM-B3LYP)”, Chem. Phys. Lett 393(1–3), pp. 51 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- [71].Krishnan R, Binkley JS, Seeger R, and Pople JA, “Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions”, J. Chem. Phys 72(1), pp. 650 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- [72].Gill PM, Johnson BG, and Pople JA, “A standard grid for density functional calculations”, Chem. Phys. Lett 209(5–6), pp. 506 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- [73].Becke AD, “A multicenter numerical integration scheme for polyatomic molecules”, J. Chem. Phys 88(4), pp. 2547 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- [74].Dunning TH, “Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen”, J. Chem. Phys 90(2), pp. 1007 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kendall RA, Dunning TH, and Harrison RJ, “Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions”, J. Chem. Phys 96(9), pp. 6796 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- [76].Dasgupta S and Herbert JM, “Standard grids for higher precision integration of modern density functionals: SG-2 and SG-3”, J. Comput. Chem 38(12), pp. 869 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Hehre WJ, Ditchfield R, and Pople JA, “Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XII. Further extensions of gaussian-type basis sets for use in molecular orbital studies of organic molecules”, J. Chem. Phys 56(5), pp. 2257 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- [78].Hariharan PC and Pople JA, “The influence of polarization functions on molecular orbital hydrogenation energies”, Theor. Chim. Acta 28(3), pp. 213 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- [79].Tomasi J, Mennucci B, and Cammi R, “Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models”, Chem. Rev 105(8), pp. 2999 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Mennucci B, “Polarizable continuum model”, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci 2(3), pp. 386 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- [81].Truong TN and Stefanovich EV, “A new method for incorporating solvent effect into the classical, ab initio molecular orbital and density functional theory frameworks for arbitrary shape cavity”, Chem. Phys. Lett 240, pp. 253–260 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- [82].Barone V and Cossi M, “Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model”, J. Phys. Chem. A 102(11), pp. 1995 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- [83].Cossi M, Rega N, Scalmani G, and Barone V, “Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the c-pcm solvation model”, J. Comput. Chem 24(6), pp. 669 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Lange AW and Herbert JM, “A smooth, nonsingular, and faithful discretization scheme for polarizable continuum models: the switching/gaussian approach”, J. Chem. Phys 133(24), pp. 244111 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Cammi R and Mennucci B, “Linear response theory for the polarizable continuum model”, J. Chem. Phys 110(20), pp. 9877 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- [86].Cossi M and Barone V, “Time-dependent density functional theory for molecules in liquid solutions”, J. Chem. Phys 115(10), pp. 4708 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- [87].Improta R, Barone V, Scalmani G, and Frisch MJ, “A state-specific polarizable continuum model time dependent density functional theory method for excited state calculations in solution”, J. Chem. Phys 125(5), pp. 054103 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Cances E, Mennucci B, and Tomasi J, “A new integral equation formalism for the polarizable continuum model: Theoretical background and applications to isotropic and anisotropic dielectrics”, J. Chem. Phys 107(8), pp. 3032 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- [89].Mennucci B, Cances E, and Tomasi J, “Evaluation of solvent effects in isotropic and anisotropic dielectrics and in ionic solutions with a unified integral equation method: theoretical bases, computational implementation, and numerical applications”, J. Phys. Chem. B 101(49), pp. 10506 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- [90].Khaliullin RZ, Cobar EA, Lochan RC, Bell AT, and Head-Gordon M, “Unravelling the origin of intermolecular interactions using absolutely localized molecular orbitals”, J. Phys. Chem. A 111(36), pp. 8753 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Horn PR, Mao Y, and Head-Gordon M, “Probing non-covalent interactions with a second generation energy decomposition analysis using absolutely localized molecular orbitals”, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 18(33), pp. 23067 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Mao Y, Horn PR, and Head-Gordon M, “Energy decomposition analysis in an adiabatic picture”, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 19(8), pp. 5944 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Mao Y, Loipersberger M, Horn PR, Das A, Demerdash O, Levine DS, Veccham SP, Head-Gordon T, and Head-Gordon M, “From intermolecular interaction energies and observable shifts to component contributions and back again: A tale of variational energy decomposition analysis”, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 72(1), pp. 641 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Pei Z, Ou Q, Mao Y, Yang J, Lande A.d.l., Plasser F, Liang W, Shuai Z, and Shao Y, “Elucidating the electronic structure of a delayed fluorescence emitter via orbital interactions, excitation energy components, charge-transfer numbers, and vibrational reorganization energies”, J. Phys. Chem. Lett 12(11), pp. 2712 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Sharma DK, Adams ST, Liebmann KL, and Miller SC, “Rapid access to a broad range of 6’-substituted firefly luciferin analogues reveals surprising emitters and inhibitors”, Org. Lett 19(21), pp. 5836 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Song CI and Rhee YM, “Development of force field parameters for oxyluciferin on its electronic ground and excited states”, Int. J. Quantum Chem 111(15), pp. 4091 (2011). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.