Abstract

Deletion of both alleles of the Candida albicans CaHK1 gene, which causes cells to flocculate when grown at pH 7.5, a pH comparable to that of mammalian blood, abolishes the ability of the yeast to establish a successful infection in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis. Within 72 h all mice inoculated with the parental C. albicans strain had died. The mice infected with either the heterozygote or revertant strain, either of which harbors only one functional CaHK1 allele, also succumbed to the infection, although survivors were observed for up to 16 days postinfection. However, mice inoculated with the Δcahk1 null strain survived for the course of the infection. These results indicate that CaHK1 is required for the virulence of C. albicans in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis. In contrast, CaHK1 is not required for the virulence of C. albicans in a rat model of vaginal candidiasis.

The incidence of fungal infection has risen significantly, due in part to an increase in the number of individuals immunocompromised by disease or suppressive therapies. Antifungal drugs currently in use primarily exploit differences between the fungal and mammalian cell surface structures, but the overall similarity of the two cell types limits the number of obvious targets. The development of genetic transformation methods and the availability of a well-defined auxotrophic strain of Candida albicans, i.e., CAI4 (16), have provided the potential for defining new pathogenic determinants of this organism which eventually could become targets for anti-infective therapies against C. albicans. In this way, the Mkc1p mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) of the cell integrity pathway (15), the CaHog1p MAPK of the putative HOG pathway (2), and the MAPKs Cek1p (10), Hst7p, and Cst20p (19), which all function in the same filamentation-invasion pathway in C. albicans, have emerged as potential new targets for antifungals since mutations in any of their encoding genes render C. albicans strains less virulent in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis. However, some MAPKs of mammalian cells show a high structural similarity with each of these MAPKs from C. albicans, and eventually, any antifungal compound which inhibits the C. albicans MAPKs could also affect the activities of mammalian MAPKs. Thus, only those kinases which specifically function in C. albicans could be of interest as potential targets for antifungals. In this regard, a new group of protein kinases, which is homologous to the sensor histidine kinase family and response regulators from prokaryotes, has recently been described for C. albicans (1, 5–7, 20, 23). Contrary to the numerous MAPKs present in mammalian cells, only a few of the mitochondrial protein kinases described thus far, such as the branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase (BCKDH kinase) (17, 22) and four pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDH kinase) isozymes (17, 21), exhibit in their C-terminal domains the consensus motifs that characterize histidine kinases. However, recent studies have shown that the BCKDH kinase (and presumably also the PDH kinase isozymes), despite its sequence similarity to histidine kinases, does not function as such and is not involved in any phosphorelay signal transduction pathway similar to that of bacteria or yeast (11). Moreover, the residues of substrates which are phosphorylated by the BCKDH kinase indicate that it functions like a serine kinase (11). Thus, the functional differences between the histidine kinase-like proteins from mammalian cells and the sensor histidine kinases from either bacterial or fungal cells emphasize their potential as specific targets for compounds which can be exploited in the development of antifungals. In fact, several compounds (hydrophobic tyramine derivatives) have recently been reported to inhibit the growth of gram-positive pathogenic bacteria by inhibition of their histidine kinase and/or response regulator two-component signal transduction phosphorelay proteins (3, 4).

In a previous study (5), we identified a gene (CaHK1, GenBank database accession no. AF013273) which encodes a putative sensor histidine kinase of C. albicans. We also constructed a Δcahk1 C. albicans null strain, and the physiological consequences of the lack of CaHK1 were characterized (6). The deletion of CaHK1 gave rise to viable cells which germinate and form hyphae similarly to the parental strain. However, in comparison to the parent, the Δcahk1 null strain flocculated extensively under those growth conditions that induced hypha formation. Because of this phenotype, we postulated that CaHK1 could participate in a signal pathway regulating the expression of a cell surface component (6), which could also be essential for pathogenesis.

In the present study, the ability of a Δcahk1 C. albicans null strain to establish infection in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis as well as in a rat model of vaginal candidiasis has been investigated. The C. albicans strains used in this work (Table 1 provides a detailed genotype description) include a parental control strain (strain CAF2) and three strains in which either one allele (strains CHK11 and CHK23) or both alleles (strain CHK21) have been deleted. Mutant strains were derived from strain CAI4 by established protocols, and their construction has been described previously (6). CHK23 contains one reconstituted CaHK1 allele and is derived from CHK22, a Δcahk1 null Ura− strain in which both alleles were deleted. CHK23 was included in all experiments to ensure that all phenotypic traits observed with CHK21 were due solely to the CaHK1 mutation rather than to unrelated mutations that may have occurred during construction of the Δcahk1 null strain. It should also be noted that the immediate parent of the CaHK1 mutants, strain CAI4, did not serve as a control in these experiments, since its Ura− phenotype renders it avirulent (9). Instead, we used CAF2, a strain from which CAI4 is directly derived and with one functional URA3 allele, similar to the CHK11, CHK21, and CHK23 strains. The generation times (μ), calculated by growing all the strains in YPD (2% dextrose–2% peptone–1% yeast extract) at 28°C and 200 rpm, were not significantly different from one another (P > 0.03) (CAF2, μ = 1.10 ± 0.08 h; CHK11, μ = 1.14 ± 0.06 h; CHK21, μ = 1.39 ± 0.02 h; and CHK23, μ = 1.13 ± 0.07 h). Also, all strains undergo the yeast- to hyphal-stage transition, even though at pH 7.5 the CaHK1 mutants flocculate by interactions along their hyphal surfaces.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains used in this study

In order to investigate whether CaHK1 was required for C. albicans infection in a mouse model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis, each C. albicans strain was grown in YPD medium at 28°C to stationary phase. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in calcium- and magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco-BRL), and suspended to a density of 2 × 106 cells per ml on the basis of hemocytometer counts prior to use. Subsequently, groups of seven male BALB/c mice (18 to 20 g each; Charles River Laboratories) were injected intravenously via the lateral tail vein with 0.5 ml (106 cells) of a cell suspension of either CAF2, CHK11, CHK21, or CHK23. Mice were observed twice daily for signs of morbidity. Mice in a moribund state were euthanized by CO2 inhalation. Concomitantly, each C. albicans strain was used to inoculate 15 additional mice. Five members from each group were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection. One kidney from each mouse was removed at 24 h, fixed in 10% formalin, and prepared for histological examination. After embedding in paraffin blocks, 4-μm-thick sections were cut and affixed to slides. Samples were then stained with periodic acid-Schiff stain and examined by light microscopy. The other kidney, as well as the liver, from each mouse was also excised, weighed, and finally homogenized in 5.0 ml of PBS. The homogenate was diluted in PBS, and aliquots were plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar supplemented with 50 μg of streptomycin per ml to prevent bacterial growth. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 to 36 h, and the numbers of CFU per gram of tissue were then quantitated.

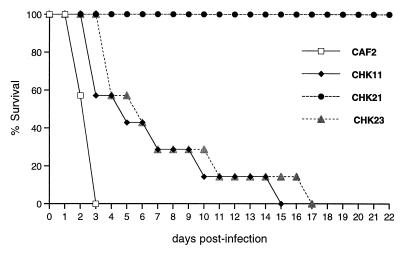

The data presented in Fig. 1 show that all mice infected with CHK21 survived throughout the experiment. In contrast, all mice infected with the parental control (CAF2) succumbed to infection within 3 days, and survival times for mice injected with either the heterozygote (CHK11) or revertant (CHK23) strain were intermediate between that observed for mice inoculated with the parental control strain (CAF2) and that observed for mice inoculated with the null strain (CHK21). Product-limit survival estimates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log rank test was employed to examine the homogeneity of survival curves among the four strains. The overall differences in survival among strains were highly statistically significant (P = 0.0001). Individual comparisons did not vary from the overall pattern: CHK21 > CHK23 ≈ CHK11 (P = 0.0001), CHK21 > CAF2 (P = 0.0004), CHK23 > CAF2 (P = 0.0004), CHK11 > CAF2 (P = 0.009), and CHK23 ≈ CHK11 (P = 0.49). Thus, survival of mice infected with CHK21, CHK11, and CHK23 was greater than that of mice infected with CAF2.

FIG. 1.

Survival of mice following infection with C. albicans CaHK1 mutants.

Quantitative determinations of the level of each C. albicans strain associated with host tissues suggest that CHK21 was slowly cleared from the kidneys and liver (Table 2). Levels of both CHK11 and CHK23 are similar to or slightly lower than that observed for the parental control; both strains persisted in tissues at 72 h. In order to determine the significance of differences observed among strains for each target organ at each of three points in time (24, 48, and 72 h), a general linear-model procedure was used. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was employed to hold the type I error (α) constant at 0.01. In terms of virulence in the liver, several statistically significant differences were seen (at P ≤ 0.01) in recovery of C. albicans (mean log10 [CFU/g]) at each of the time intervals. The following results were obtained: at 24 h, CAF2 > CHK23 > CHK21 and CHK11 > CHK21 (no other comparisons revealed differences); at 48 h, CHK11 > CHK23 or CHK21 and CAF2 > CHK21 (no other comparisons revealed differences); at 72 h, CHK11 and CHK23 > CHK21. CHK11 and CHK23 did not differ from one another. In terms of virulence in the kidney, several statistically significant differences were seen (at P ≤ 0.01) in recovery of C. albicans (mean log10 [CFU/g]) at each of the time intervals: at 24 h, CHK11 > CHK21 (no other comparisons revealed differences); at 48 h, CAF2 > CHK23 > CHK21 and CHK11 > CHK21 (no other comparisons revealed differences); at 72 h, CHK23 and CHK11 > CHK21, and CHK23 and CHK11 did not differ from one another. By 72 h, all mice infected with CAF2 had died.

TABLE 2.

Recovery of C. albicans from infected tissues

| Time postinfection (h) | Strain | Log10 CFU/g (mean ± SD) for:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | Liver | ||

| 24 | CAF2 | 5.21 ± 0.49 | 3.96 ± 0.09 |

| CHK11 | 6.04 ± 0.48 | 3.79 ± 0.06 | |

| CHK21 | 4.12 ± 0.18 | 2.92 ± 0.28 | |

| CHK23 | 4.97 ± 0.85 | 3.49 ± 0.09 | |

| 48 | CAF2 | 6.67 ± 0.69 | 3.32 ± 0.20 |

| CHK11 | 6.40 ± 0.40 | 3.52 ± 0.47 | |

| CHK21 | 3.27 ± 0.58 | 2.34 ± 0.45 | |

| CHK23 | 5.09 ± 0.57 | 2.61 ± 0.12 | |

| 72 | CAF2 | —a | —a |

| CHK11 | 5.87 ± 0.57 | 3.55 ± 0.78 | |

| CHK21 | 2.43 ± 0.27 | 0.36 ± 0.72 | |

| CHK23 | 6.09 ± 0.90 | 2.86 ± 0.60 | |

—, All mice succumbed to CAF2 infection by 72 h.

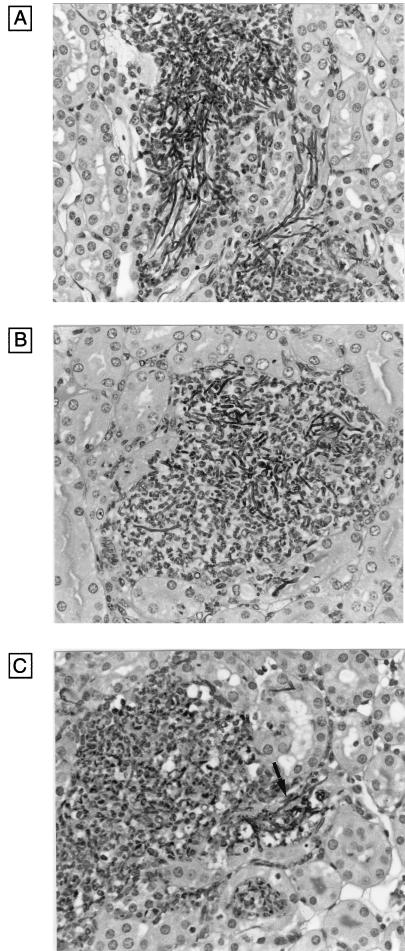

Histological examinations of kidney tissue support these observations. Thus, CAF2 and the strains with one allele deleted (CHK11 and CHK23) showed mycelial growth in infected tissue, but CAF2 formed more extensive hyphae (Fig. 2A) than CHK11 (Fig. 2B) or CHK23. Also, mycelial growth was observed in tissues infected with CHK21, but in comparison to those infected with CHK11 or CHK23, smaller amounts of cells were observed (Fig. 2C), probably because a more effective clearing of the CHK21 strain was performed by phagocytic cells in comparison to the clearing of CAF2 or the strains with one allele deleted, which grew extensively in the tissues and eventually killed the mice.

FIG. 2.

Histological examination of kidneys obtained from mice 24 h after infection with C. albicans CAF2 (A), CHK11 (B), and CHK21 (C). Original magnification, ×400. The arrow indicates hyphae.

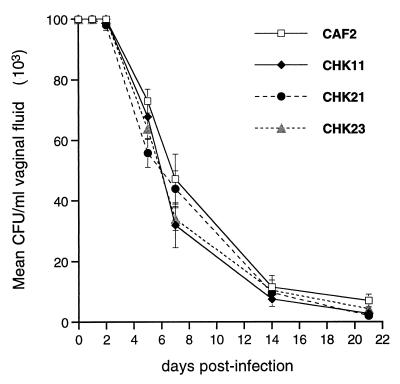

CaHK1 encodes a putative sensor histidine kinase that is likely involved in sensing some signal. In order to investigate whether a CaHK1 null mutant remained avirulent in response to other environmental signals indigenous to a host niche but different from those perceived by the yeast during a hematogenously disseminated infection, a rat model of vaginal candidiasis was made by infecting ovariectomized, estrogen-treated rats with 107 yeast cells of each strain as previously described (13, 14). The results are shown in Fig. 3. Interestingly, infection with either the null mutant (CHK21) or the heterozygous control strains (CHK11 and CHK23) resulted in rates of clearance identical to that for the parental control (CAF2). Thus, for all strains, a sustained vaginal infection was observed during the first 3 days and a gradual decline in the fungal burden was observed over the next 19 days. Also, the kinetics of clearance for each strain was very similar to that reported for other vaginopathic strains (12). Microscopic examinations of vaginal scrapings taken from rats infected with each strain showed the typical yeast forms 1 h after challenge, but after 48 h, each of these strains developed hyphae in a very similar way (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Kinetics of infection and fungus clearance from the vaginas of ovariectomized, estrogen-treated rats challenged on day 0. Error bars, standard errors of the means.

The avirulence of the Δcahk1 C. albicans null strain in a mouse model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis and the virulence of this mutant in a rat model of vaginal candidiasis indicate that the requirement of CaHK1 for the pathogenesis of C. albicans is related to the host niche. Since the virulence of CHK21 in the murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis was restored by reintroduction of a parental copy of CaHK1, it is clear that avirulence of CHK21 in the murine model is directly associated with the loss of the CaHK1 gene. Recently, it has been reported that an alteration of the position of the URA3 selectable marker in some C. albicans mutant strains obtained by the Ura-blaster protocol may cause a change in its level of expression, which could complicate the interpretation of reduced virulence or avirulence of mutants (18). However, determinations of the orotidine 5′-monophosphate (OMP) decarboxylase activities of the CHK11, CHK21, and CHK23 strains did not indicate any difference with respect to the OMP decarboxylase activity of CAF2. In fact, these results as well as the similar growth rates of CAF2 and the CaHK1 mutant strains indicate that the difference in virulence of CAF2 and the CaHK1 mutants could not be due to the position of the URA3 locus in the latter strains, since the three CaHK1 mutants carry the URA3 gene in exactly the same position in the chromosome (6). Furthermore, the virulence of CHK21 in a model of vaginal candidiasis rules out the possibility that the results obtained in the model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis could be due to the slight difference in the generation time between the parental strain (CAF2; μ = 1.10 ± 0.08 h) and the CaHK1 null strain (μ = 1.39 ± 0.02 h). However, we cannot totally exclude the possibility that the small difference in the generation time estimated in vitro between CAF2 and CHK21 resulted in pathogenic differences observed in vivo during the hematogenously disseminated infection. Also, we did not compare the levels of hydrolytic enzymes that are thought to be virulence factors, such as the members of the secreted aspartyl proteinase family (encoded by the SAP1 through SAP9 genes) (8) and the secreted phospholipase activities (8), in the Δcahk1 null and parental strains. Likewise, the adhesion of the Δcahk1 null strain to different host ligands (8) was not measured. Therefore, it is possible that the expression of these factors could have been affected by the lack of CaHK1 in the Δcahk1 null strain in the hematogenously disseminated infection rather than in the vaginal infection. In addition, since Cahk1p may function in signal transduction, it could also play a role in the expression of multiple potential pathogenic factors not related to cell surface constituents.

In summary, our data indicate that the virulence of CHK11 and CHK23 in a murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis is due to the presence of one functional CaHK1 allele, while the avirulence of CHK21 is due to the absence of any CaHK1 allele. Also, CaHK1 is not required for the virulence of C. albicans in a rat model of vaginal candidiasis.

In conclusion, these data indicate a role for CaHK1 in a hematogenously disseminated infection caused by C. albicans. We have previously proposed that CaHK1 may be a component of a phosphorelay system that regulates the expression of a cell surface protein(s) (6). Presently, we have shown that the changes in the cell surface caused by the CaHK1 deletion also affected the ability of a Δcahk1 null strain to invade tissues and cause disease in a host niche-dependent way. This supports the previous observations of others that the host niche regulates the expression of virulence determinants (14) and indicates that CaHK1 could be involved in regulating the expression of some of these determinants. Finally, the absence of functional histidine kinase signal transduction pathways in mammalian cells and the recent reports about compounds which specifically inhibit the activity of these proteins make the histidine kinases of C. albicans, particularly Cahk1p, an attractive target for the development of new antifungal drugs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Public Health Service grant to R.C. (NIH-NIAID-POIAI37751). J.A.C. is a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Educación y Cultura of the Spanish government.

We thank William Fonzi for performing the OMP decarboxylase assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alex L A, Korch C, Selitrennikoff C P, Simon M I. COS1, a two-component histidine kinase that is involved in hyphal development in the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7069–7073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso-Monge R, Navarro-García F, Molero G, Diez-Orejas R, Gustin M, Pla J, Sánchez M, Nombela C. Role of the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1p in morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3058–3068. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3058-3068.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett J F, Goldschmidt R M, Lawrence L E, Foleno B, Chen R, Demers J P, Johnson S, Kanojia R, Fernandez J, Bernstein J, Licata L, Donetz A, Huang S, Hlasta D J, Macielag M J, Ohemeng K, Frechette R, Frosco M B, Klaubert D H, Whiteley J M, Wang L, Hoch J A. Antibacterial agents that inhibit two-component signal transduction systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5317–5322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett J F, Hoch J A. Two-component signal transduction as a target for microbial anti-infective therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1529–1536. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calera J A, Choi G H, Calderone R. Identification of a putative histidine kinase two-component phosphorelay gene (CaHK1) in Candida albicans. Yeast. 1998;14:665–674. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199805)14:7<665::AID-YEA246>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calera J A, Calderone R. Flocculation of hyphae is associated with a deletion in the putative CaHK1 two-component histidine kinase gene from Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1999;145:1431–1442. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calera, J. A., and R. Calderone. Identification of a putative response regulator two-component phosphorelay gene (CaSSK1) from Candida albicans. Yeast, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Chaffin W L, Lopez-Ribot J L, Casanova M, Gozalbo D, Martinez J P. Cell wall and secreted proteins of Candida albicans: identification, function, and expression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:130–180. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.130-180.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole M F, Bowen W H, Zhao X J, Cihlar R L. Avirulence of Candida albicans auxotrophic mutants in a rat model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;126:177–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Csank C, Schroppel K, Leberer E, Harcus D, Mohamed O, Meloche S, Thomas D Y, Whiteway M. Roles of the Candida albicans mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog, Cek1p, in hyphal development and systemic candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2713–2721. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2713-2721.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davie J R, Wynn R M, Meng M, Huang Y S, Aalund G, Chuang D T, Lau K S. Expression and characterization of branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase from the rat. Is it a histidine-protein kinase? J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19861–19867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Bernardis F, Adriani D, Lorenzini R, Pontieri E, Carruba G, Cassone A. Filamentous growth and elevated vaginopathic potential of a nongerminative variant of Candida albicans expressing low virulence in systemic infection. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1500–1508. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1500-1508.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Bernardis F, Cassone A, Sturtevant J, Calderone R. Expression of Candida albicans SAP1 and SAP2 in experimental vaginitis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1887–1892. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1887-1892.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Bernardis F, Muhlschlegel F A, Cassone A, Fonzi W A. The pH of the host niche controls gene expression in and virulence of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3317–3325. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3317-3325.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diez-Orejas R, Molero G, Navarro-García F, Pla J, Nombela C, Sanchez-Perez M. Reduced virulence of Candida albicans MKC1 mutants: a role for mitogen-activated protein kinase in pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:833–837. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.833-837.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonzi W A, Irwin M Y. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris R A, Hawes J W, Popov K M, Zhao Y, Shimomura Y, Sato J, Jaskiewicz J, Hurley T D. Studies on the regulation of the mitochondrial alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase complexes and their kinases. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1997;37:271–293. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(96)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lay J, Henry L K, Clifford J, Koltin Y, Bulawa C E, Becker J M. Altered expression of selectable marker URA3 in gene-disrupted Candida albicans strains complicates interpretation of virulence studies. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5301–5306. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5301-5306.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leberer E, Harcus D, Broadbent I D, Clark K L, Dignard D, Ziegelbauer K, Schmidt A, Gow N A, Brown A J, Thomas D Y. Signal transduction through homologs of the Ste20p and Ste7p protein kinases can trigger hyphal formation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13217–13222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagahashi S, Mio T, Ono N, Yamada-Okabe T, Arisawa M, Bussey H, Yamada-Okabe H. Isolation of CaSLN1 and CaNIK1, the genes for osmosensing histidine kinase homologues, from the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1998;144:425–432. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popov K M, Kedishvili N Y, Zhao Y, Shimomura Y, Crabb D W, Harris R A. Primary structure of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase establishes a new family of eukaryotic protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26602–26606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popov K M, Zhao Y, Shimomura Y, Kuntz M J, Harris R A. Branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase. Molecular cloning, expression, and sequence similarity with histidine protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13127–13130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srikantha T, Tsai L, Daniels K, Enger L, Highley K, Soll D R. The two-component hybrid kinase regulator CaNIK1 of Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1998;144:2715–2729. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-10-2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]