Abstract

Bacteria are keenly sensitive to properties of the surfaces they contact, regulating their ability to form biofilms and initiate infections. This study examines how the presence of flagella, interactions between the cell body and the surface, or motility itself guide the dynamic contact between bacterial cells and a surface in flow, potentially enabling cells to sense physico-chemical and mechanical properties of surfaces. The work focuses on a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) biomaterial coating which does not retain cells. In a comparison of four E. coli strains with different flagellar expression and motility, cells with substantial run-and-tumble swimming motility exhibited increased flux to the interface (three time the calculated transport-limited rate which adequately described the non-motile cells), greater proportions of cells engaging in dynamic nanometer-scale surface associations, extended times of contact with the surface, increased probability of return to the surface after escape and, as evidenced by slow velocities during near-surface travel, closer cellular approach. All these metrics, reported here as distributions of cell populations, point to a greater ability of motile cells, compared with nonmotile cells, to interact more closely, forcefully, and for greater periods of time with interfaces in flow. With contact durations of individual cells exceeding ten seconds in the window of observation, and trends suggesting further interactions beyond the field of view, the dynamic contact of individual cells may approach the minute timescales reported for mechanosensing and other cell recognition pathways. Thus, despite cell translation and the dynamic nature of contact, flow past a surface, even one rendered non-cell arresting by use of an engineered coating, may produce a subpopulation of cells already upregulating virulence factors before they arrest on a downstream surface and formally initiate biofilm formation.

Keywords: bacteria, mechanosensing, contact time, cell populations, residence time, flux

Introduction

Bacterial adhesion or arrest on a surface is usually considered the first step of infection and biofilm formation;1, 2 however, even before they formally adhere, bacteria can be influenced by both nanometric surface contact and by longer range hydrodynamic interactions with a surface. An example of the impact of transient but intimate contact between bacteria and surfaces, swimming cells can travel along and sample surfaces until they reach regions favorable for adhesion and colonization, at which point they arrest.3, 4 This demonstrates that, in quiescence at least, bacteria can experience surface forces of physico-chemical origin as they swim, as long as they approach sufficiently closely to the surface. In contrast, dramatic swimming behaviors dominated by hydrodynamic interactions may not require nanometric contact. For instance, near rigid surfaces, E. coli swim in a clockwise direction (when viewed from the fluid toward the surface)5, 6 but circle oppositely at air-water interfaces,7, 8 a consequence of the no-slip vs slip boundary condition at the wall or free surface, respectively.9–11

The swimming dynamics of E. coli towards, along, and away from minimally adhesive hydrogels was recently found to depend on hydrogel stiffness, with travel along the stiffest materials biasing cells to circle back to the interface in flow.12 This ability of swimming cells to distinguish coating mechanics may require close cell approach to a surface, but it is unclear whether the cell body or the flagella is responsible. Because restrictions in flagellar rotation trigger the upregulation of virulence factors,13–16 because exposure of the cell envelope to interfacial physico-chemistry can initiate separate virulence pathways,17–20 and because surface mechanics influence the frequency and duration of cell-surface encounters,12, 21, 22 it becomes important to understand the extent of surface contact for swimming and flowing bacteria. These close interactions may allow material chemistry and mechanical interactions to produce a population of surface-altered cells of increased virulence even before arrest occurs. Indeed, recent work suggests that P. aeruginosa exposed to a glass surface for ∼20 hours exhibited substantial differences in gene expression and in the ability to interact with the same surface later and after cell division.23 Given the emphasis on reducing bacterial adhesion, for instance through the use of minimally adhesive coatings, this work prompts the question of whether dynamic contact with a nonadhesive surface could be sufficient to prime cells for subsequent surface interactions and biofilm initiation.

Motile E. coli, associated with disease24–27 and biomaterial infections,28 swim using a flagellar bundle. Run and tumble behavior, occurring when one or more flagellar motors temporarily reverses, facilitates chemotaxis. During the run phase for E. coli and other bacteria10, 29–31 cell motion is described as “pushing.” Pushing involves a long range hydrodynamic dipole29, 32 with outward force from the cell ends and inward force towards its sides, with the latter producing attractions between the sides of cells and surfaces, and partially orienting near-surface cells.10 A result of these interactions, non-tumbling E. coli cells can concentrate by about a factor of 5, in a region 10–20 µm from the rigid walls bounding fluid channels that are 100 or 200 µm deep.32 Here the impact of this elevated concentration has not been extended to an understanding of cell concentrations in the region nanometers from the surface, critical to surface sensing, or to the surface collisions themselves. Careful experiments suggest that hydrodynamic attractions, which enable E. coli to travel along glass surfaces in quiescence for extended periods, produce cell-surface separations larger than those of electrostatic and van der Waals forces.33, 34 In some studies, reversal of flagella rotation is critical to produce collisions and adhesion to glass.35 Conversely, surface collisions of Caulobacter crescentus enable cell reorientations that facilitate cell swimming along the surface.36

Beyond the behaviors of swimming bacteria in quiescent conditions, swimming bacteria can become trapped in shear fields, concentrating within the more sharply varying regions of a shear gradient.37 Consequently, shear trapping tends to concentrate cells towards a chamber’s walls but, depending on flow and system geometry, may not be a large effect. Also, flagella-driven cells often orient against flow, enabling them to swim upstream against weak flow, a process called rheotaxis.38, 39

The questions of how flowing motile and non-motile bacteria contact and may sense surfaces motivates studies addressing which parts of cells actually contact a surface during flow, the role of motility, and the influence of a surface on cell travel. In order to understand the potential for sensing of the interface by traveling cells, it is necessary to address the magnitudes and durations of forces on the cell body and appendages as the surface is closely approached. This translates to a need to measure the distances of flowing swimming cells near surfaces, their collisions, velocities, and near-surface residence time distributions. Modeling predicts how elevated near-surface concentrations of cells result from cell fluxes near an interface,32, 36 but these fluxes have not been experimentally quantified nor have the residence of times of near-surface cells been probed. Understanding the chemical and mechanical histories of populations of near-surface cells will facilitate anticipating when virulence factors can be triggered. Pathways requiring short exposures to stressors may be particularly susceptible to intermittent surface contact. Actions triggered by flagellar obstruction, for instance, are recognized to take place on minute-timescales.40–42

The current study addresses the potential for the bacterial flow and dynamic contact with surfaces coated with minimally adhesive poly(ethylene glycol (PEG) end-tethered layers to produce a population of cells whose surface sensing pathways have been initiated, preconditioning the cells for later surface adhesion and biofilm formation. This is an important issue because the great investment in non-adhesive coatings such as PEG and polyzwitterions has been driven by thinking that eliminating bacterial arrest prevents infection. Indeed, it is clear that, even without gravity driving cells towards or away from hydrogels, bacterial dynamics is sensitive to hydrogel stiffness.12 By characterizing cell type-dependent differences in near-wall trajectories, this work probes the influence of cell morphology and motility on dynamic interactions with the PEG-coated wall, potentially arising from hydrodynamic and reversible physico-chemical interactions. The work reports the duration of dynamic cell contact in flow, evidence for substantial dynamic interactions, and the relative sizes of affected cell populations. The study probes dynamic interactions between individual flowing bacteria and a single minimally-adhesive poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-modified wall, contrasting with studies in quiescence or in conditions that allow for two parallel channel walls to interact with individual cells restricting them within close range of surfaces. While cells are not captured on the PEG-coated wall, they do travel along the surface with trajectories suggesting dynamic reversible interactions. We term the surface-influenced portions of trajectories “engagements” due to their parallel with reversibly bound particles and molecules. Cells near the surface reach nanometric separations, bind reversibly and travel on the surface, and later dis-bond depending on cell morphology and motility.

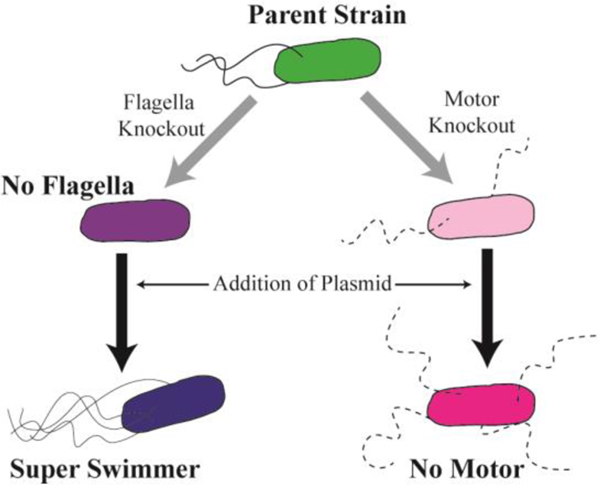

To distinguish the roles of motility and flagella, several E. coli strains, with and without flagella and separately with and without working motors to rotate flagella were compared: “Super Swimmers” are bacteria expressing larger numbers flagella and swimming faster than the parent strain but still exhibiting run-and-tumble behavior; “No Motors” refer to a non-motile version of the Super Swimmers engineered to have non-functioning flagella; and “No Flagella” are engineered from the same “Parent Strain” do not express flagella. In this way, a comparison of Super Swimmer and No Motor strains allows for physicochemical interactions of flagella with the surface, but distinguishes the hydrodynamics of swimming and non swimming strains. Comparison of No Motor and No Flagella strains probes the impact of physicochemical interactions of the cell body versus flagella with the surface. The Parent strain provides an additional control.

We note that the Super Swimmer strain, while probing the impact of motility exhibits the run-and-tumble traits of wild-type cells, and a run speed velocity of 1–6 μm/s. Compared with engineered cells that swim continuously, the swimming character of the Super Swimmer strain might be useful in translations to real-world biofilm formation scenarios.

Material and Methods

Design of Model Bacterial System

A summary schematic of the genetic modifications and strains used in the design of the model E. coli system is shown in Figure 1. The Keio collection was used as the basis for the model E. coli system due to the availability of isogenic mutants.43 E. coli BW25113, E. coli JW1881 and E. coli JW1879 were purchased from the Coli Genetic Stock Center (New Haven, CT). E. coli BW25113 (Parent Strain) is the parent stain of the Keio collection. E. coli JW1881 (No Flagella) is a modified strain with a genetic knockout of the flhD gene which is critical for the growth of flagella.44 E. coli JW1879 is contains a genetic knockout of the motA gene that is necessary for proton-conduction in the flagella motor, yet does not affect flagella synthesis.45 In order to upregulate the growth of flagella, in both isogenic mutant strains, a pflhDC plasmid was cloned into the isogenic mutant strains. Details of plasmid design and procedures have been published previously.12 Incorporated into the No Flagella strain, this plasmid restores and upregulates the motility of the bacteria, producing a Super Swimmer strain. By cloning the same plasmid into the motor mutant strain, flagella growth was upregulated without restoring motility. This strain, called the “No Motor” strain, has a similar number of flagella as the Super Swimmers, but lacks the ability to swim.

Figure 1.

Design of model E. coli system. The Keio collection was chosen due to the availability of single gene knockout mutants. Two mutants, one for flagella and one for flagella motors were chosen. These strains were further modified with the constructed pflhDC+EGFP plasmid to upregulate the growth of flagella.

Bacteria Preparation

Bacteria were grown in overnight at 37°C in Luria- Bertani broth (LB) with antibiotics as required: no antibiotics for the Parent Strain, 50 µg/mL kanamycin for the No Flagella strain, or 50 µg/mL kanamycin and 100µg/mL carbenicillin for the Super Swimmer and No Motor strains. After overnight growth, liquid cultures were restarted using 200 µL of overnight culture in 5mL of LB and same antibiotics. Additionally, in the restarted cultures 50 µL of 20% wt/vol arabinose solution was added to the Super Swimmer and No Motor Strains to induce the flhDC plasmid. These cultures were grown for 4 hours and harvested in the log growth phase.

Bacteria cultures were then washed 3 times (centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 2 min) in pH 7.4 phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (0.008 M Na2HPO4, 0.002 M KH2PO4, and 0.15 M NaCl) and resuspended in the same buffer at a concentration of approximately 1×108 cells/mL, and studied immediately. This concentration is below that where bacteria-bacteria interactions were found relevant at surfaces.46 The concentration was determined using OD600 measurements.

Motility Characterization

We employed a commonly implemented assay to confirm the motility of the bacteria strains.47 Soft gel plates with 0.4% agar in LB media, in 10 cm petri dishes were made immediately before beginning the assay. 2 µL of liquid culture was pipetted into the center of the plate and its location marked. Plates were then incubated at 37ºC for 72 hours. In order to determine relative motility between strains the distance that the bacteria growth front traveled was marked every 24 hours. This motility characterization was conducted throughout this and other studies12 with the four E. coli strains to confirm consistent bacterial behavior. When cultures were streaked from glycerol, typically monthly, the subsequent cultures were confirmed to have identical mobility.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Characterization

After the final growth step described above, bacteria were washed by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 2 minutes in deionized (DI) water 3 times and then fixed in 2.5% glyceraldehyde solution in DI water for 2 hours followed 3 additional washes in DI water. 20µL of resuspended bacteria solution was pipetted onto the center of a piece of a clean silicon wafer and allowed to air dry overnight. Samples were sputter coated (Cressington Sputter Coater 108) with gold for 60 seconds prior to imaging with a FEI Magellan 400 XHR-SEM.

PLL-PEG Brush Surfaces

PLL-g-PEG copolymers were synthesized and characterized as previously described, and upon adsorption to negative surfaces formed PEG layers where PEG tethers were 5000 g/mol.48 The hydrated PEG thickness was near 15 nm.12, 48

To produce these layers on glass slides, microscope slides (Fishers Finest) were etched overnight in concentrated sulfuric acid. This treatment has been shown to produce a pure silica surface.49 Slides were functionalized by flowing a 100 ppm PLL-g-PEG solution in pH 7.4 phosphate buffer (0.008 Na2HPO4 and 0.002M KH2PO4) over the glass surface at a shear rate of 15 s−1 for 10 minutes followed by 10 minutes of flowing buffer. Finally, the flow chamber was rinsed for 10 minutes with the PBS prior to introducing flowing bacteria. The PEG brush layer has been shown not to degrade or come off the surface in the salt concentrations used in the current studies, and it is among the best coatings to resist protein adhesion in-vitro, with amounts of adsorbing fibrinogen below detectible limits of 0.01 mg/m2.21, 50–53

Studies of Bacteria-Surface Interactions in Flow

Studies of interactions between flowing bacteria and surfaces modified with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) brushes were conducted in a custom-built flow cell system in which the test surface comprised one wall of the flow chamber. The microscope was oriented horizontally, and the flow cell was oriented perpendicular to the floor on an optical bench to prevent gravity from contributing to cell-surface interactions. The objective used for these studies was a Nikon Plan Fluor 20x with a numerical aperture of 0.5, having a depth of field of approximately 3.5 µm. Bacteria were flowed across the surface at a shear rate of 15 s−1 for approximately 10 minutes. Data was recorded at 30 fps and analyzed at a rate of 5 fps using FFmpeg software. Manual tracking was conducted using FIJI is just ImageJ. From the positions of individual bacteria in stacks of video frames, velocities of near surface cells were calculated. Further analysis and interpretation follows procedures and modeling that has been described previously,12 with key features explained at appropriate parts of the results.

Unless otherwise indicated, all studies employed at least 3 separate cultures for each bacterial strain, grown on separate days. These data were always sufficiently reproducible that data were combined in comparisons from one strain to another.

Results

Bacteria Characterization

Studies were conducted to establish that the genetic modifications produced the intended morphological features and dynamic behaviors. For the Super Swimmers and No-Motor strains, characterization was published previously12 and data are included here for comparison.

Representative scanning electron micrographs in Figure 2 confirm the presence and absence of flagella in the four strains. The interpretation of the micrographs is limited to a qualitative assessment of the flagella numbers, as we found evidence that specimen preparation for electron microscopy breaks many flagella. The majority of the flagella in the Super Swimmers are well over 5 µm in length and have a defined helical shape. A few, however, are significantly shorter (∼1 µm), likely due to breakage during sample preparation. In both the Super Swimmer and No Motor strains, which contained the flhDC plasmid, a large number of flagella were seen in all micrographs. Many cells had several flagella, though some had a single flagellum. By contrast, with the flhD gene knocked out in the No-Flagella strain, no evidence of any flagella was found in any micrograph. The micrographs of the Parent Strain show few flagella attached to cells. The results indicate that the pflhDC plasmid does upregulate the growth of flagella when compared to the Parent Strain.

Figure 2.

A) Scanning electron micrographs confirming the presence (or absence) of flagella on each of the strains. Flagella attached to cells are highlighted. B) Typical image with many Super Swimmer cells.

A plate motility assay was employed to confirm the motility of the different strains based on the observed colony expansion from an inoculated region at the center of an agar plate.54, 55 Figure 3A presents images of the plates 72 hours after inoculation. The Super Swimmers and the Parent strain exhibit substantial motility with the Super Swimmers reaching the edge of the plate more rapidly, as summarized in Figure 3B. Conversely, the persistently small size of the No-Flagella and No-Motor colonies, with only slight colony expansion due to crowding, is consistent with the intended lack of motility in these strains. The combined micrographs and motility results demonstrate that the No-Motor strain lacks motility despite its multiple numbers of flagella per cell, consistent with the intended non-functioning motors at the base of each flagellum.56 Worth noting, the plate motility assay confirms general swimming activity but does not address the relative sizes of any motile and non-motile populations within a batch.

Figure 3.

A) Motility plates showing the colony sizes at 72 hours for the four strains. B) Relative colony size, normalized on plate radius, as a function of time. No Flagella and No Motor data lie on top of each other in B). Error bars represent standard deviation for N=3 at each time. These data, based on 3 samplings of a single bacterial culture were in quantitative agreement with additional data taken from a separate culture originating from a separate sampling of the glycerol bacterial stocks.

Near-Surface Cell Engagement and Tracking

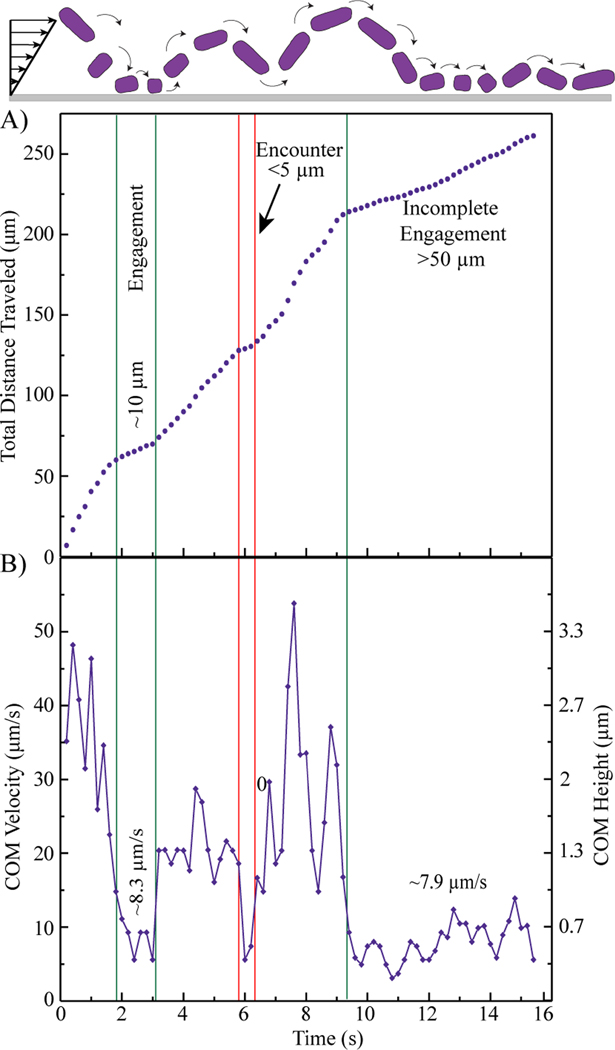

A flow-chamber was oriented so that cells did not settle towards or away from the PEG-coated test surface. In studies of cell behavior, here conducted at a wall shear rate of 15 s−1, flowing cells did not arrest but exhibited runs of near-wall travel, distinct in velocity and velocity fluctuations from free cell motion nanometers further from the wall. Indeed, of the millions of cells flowing through the 700 µm- thick chamber, only a subset of those approached the brush-modified test surface and were visible within the ∼3 µm depth of field of the optics. Cells with slow travel, exhibiting evidence of surface interactions were tracked manually, in the example of Figure 4. The procedure and rationale are similar to the tracking and analysis of motile cells detailed in previous studies,12, 21 with key concepts described below. The example in Figure 4 shows a typical flowing No-Flagella E. coli cell.

Figure 4.

A) Total distance traveled and B) and instantaneous velocity as a function of time for a typical No Flagella E. coli cell traveling near the surface in laminar shear flow with a wall shear rate of 15 s-1.

In, Figure 4 a No-Flagella E. coli cell enters the field of view traveling quickly. After about 2 seconds the cell slows to a velocity of about 8.3 µm/s for a period of 1.2 seconds. It then travels more quickly for about 2.8 seconds before briefly encountering the surface and then traveling quickly once again. After an additional 3 seconds, the cell exhibits a period of protracted slow movement, at about 7.9 µm/s, to the edge of the visible field and then it exits. The differences in cell velocity indicate that, in addition to traveling in the flow direction, the cell is moving perpendicular to the surface, sampling streamlines of different speeds, potentially changing its orientation and experiencing viscous drag and reversible adhesion when it is close to the surface. For cells whose separation from the surface exceeds about 1 (effective) cell diameter, the cell travels at the free stream velocity corresponding to its center of mass (COM), for instance in Figure 4. Closer than this, hydrodynamic interactions between the cell and the wall influence cell velocity. Relevant example calculations and plots can be found in the supporting information of our prior work.12

Specific to the conditions in the current study, when a cell engages the surface through reversible adhesive interactions or viscous drag against the ∼15 nm thick PEG brush, its velocity is reduced below what it would be, moving freely on the same streamline at the same orientation. (With a particle Reynolds number of ∼10−4, cells are dominated by viscous rather than inertial effects, and so bouncing and rebounding is not a suitable explanation for periods of slow movement.) Figure 4 demonstrates that some interactions between a cell and a surface can produce protracted periods of relatively slow near-surface travel. Similar to the example in Figure 4, it was generally the case that when a cell was moving slowly, it exhibited smaller velocity fluctuations than it experienced when it was moving quickly, further evidence of interactions with the PEG brush.

We sought a working guideline to distinguish cells with surface interactions from those moving freely. Then for surface-interacting cells we compared the behaviors of different bacterial strains. With flowing near-surface cells interacting intermittently and reversibly with the surface, we identified “surface engagements” during which the rate of cell travel along the surface was substantially reduced from the velocity expected for a free near-surface cell, evidence for interactions at the surface.

In identifying cells moving slower than the free stream velocity and therefore dynamically engaging the surface, we were guided, in part by Brenner’s treatment of a sphere traveling past a wall in shear flow.57 At a wall shear rate of 15 s−1, a 3 μm -diameter sphere having its surface just nanometers (1–5 nm) from the wall will translate with a velocity of 9–10 μm/s. We considered this velocity as one measure of the minimum free cell travel velocity, below which cells must be interacting with the surface. (We note that other groups have also applied Brenner’s treatment to capsular bacteria.6, 34, 35) Also taken into consideration, for a wall shear rate of 15 s−1, the streamline velocity 2 μm from a surface is 30 μm/s or, 1 μm from the surface the free stream velocity is 15 μm/s. These velocities exceed range of run velocities 4–7 μm/s reported for the current Super Swimmers.12 Thus, the near-surface flow for a wall shear rate of 15 s−1 is strong enough to dominate bacterial movement via swimming, and more than a few microns from the wall, bacterial travel is entirely dominated by the flow. These considerations motivated our categorization of slow-moving cells, traveling less than 9.3 µm/s for a distance of at least 5µm (approximately two body lengths) as being engaged with the surface during their travel. Thus, we analyzed cells having runs of dynamic adhesion that persisted for at least 0.6 s. While some cells may have engaged dynamically, for instance by reversible adhesion, for shorter times these engagements were not trackable with our framing rate and magnification. The 5 µm travel requirement ensures that slight errors in manual tracking did not produce erroneous engagements. The current work employs this working definition to distinguish cells that are freely moving from those whose interactions between the cell body and the surface have influenced and reduced their motion. In this way we consistently identified populations of engaging cells for further study. Comparison of behaviors between different strains provided further evidence for interactions between flagella and the surface.

Based on this definition of an engagement, the cell shown in Figure 4 experiences two engagements plus a shorter encounter that does not qualify as an engagement. The second of the two full engagements extends beyond the field of view and can be counted in the numbers of engagements but could not be included in other analyses such as engagement lengths or average engagement velocity.

While the 9.3 µm/s criterion to define an engagement appears arbitrary, we find that moderate variations in the choice of cut off velocity had minimal impact on the statistics and conclusions reported here, detailed for key cases in the Supporting Information. The effect of choosing a larger cutoff is that there are more engaged cells per unit time and area and somewhat longer engagements; however, the effect is small. For instance, choosing a cut-off velocity of 11 µm /s rather than 9.3 µm/s, in the sample run shown in Figure 4 the additional encounter that previously did not qualify as an engagement would qualify as a short engagement with a length of 5.9 µm. There is no effect on the length of the other complete engagements. The choice of cut off is additionally consistent with the observation that during engagement, we find velocity fluctuations reduced compared to that during cell motion away from the wall. As an example, for the run in Figure 4, the variances of the velocities for the two engagements were 4.2 and 6.2 µm2/s2, while for the periods of time between engagements it was 93 µm2/s2. This difference in variance between the engaged and non-engaged velocities is seen across all the runs. Thus, we proceeded with the working criterion of a 9.3 µm/s cut off to designate which cells were adhesively or frictionally engaged with the surface, warranting further analysis.

Surface Engagement Flux

The numbers of cells engaging the surface per area and time is a distinguishing feature of the different cell types and is defined as the engagement flux. Summarized in Figure 5A, the engagement flux is highly reproducible, suggesting the flux values represent a steady state condition that is achieved after introduction of the cell suspension in flow over the surface. With steady state established, we do not observe cell accumulation on the surface: neither cell arrest nor a growing population of cells moving along the surface. Rather the numbers of cells moving along the surface becomes fixed in time after the start of the experiment, with some arriving and others leaving. It is possible then to conceive the engagement of an individual cell in flow as being analogous to reversible cell capture: a cell comes to the surface and later leaves, but while engaged at the surface it travels downstream.

Figure 5.

A) Flux of engaging cells of different bacterial strains, defined as the number of cells having at least one engagement in the field of view. Data are based on the analysis of 30s segments of video at a time. Analysis of multiple sections (minimum of 3 per strain) of video gave identical fluxes within error bars shown. Y-axis values are corrected to account for batch-batch variations in cell concentration near the working concentration of 108 cells/ml. B) Number of engagements per cell within the 260 µm length of the viewing field. 25–35 bacteria per run were tracked for three runs with each strain and combined. Error bars are standard deviations.

The flux of Figure 5A counts cells having at least one engagement in the field of view and shows that Super Swimmer cells exhibit a far greater engagement flux than other types. Super Swimmers not only arrive to the interfacial region in greater numbers, but also engage the surface in greater numbers compared with less motile and non-motile variants. Previous studies focusing on microns of fluid near a surface have reported higher concentrations of straight swimming motile near-surface bacteria,32 but have not addressed the near-surface cell flux or efficiency of any engagement or reversible adhesion to the surface.

The engagement flux is the analog of the per area capture rate of conventional non-active cells or particles on a sticky surface. In the classical case where diffusing species adhere rapidly to a wall from shear flow, the Leveque treatment predicts the maximum diffusion-limited accumulation, where all diffusers reaching the interface are captured efficiently, that is, as quickly as they arrive.58 More generally, a fraction of the flowing nonmotile cells, diffusing to an interface, engage the surface through slow-forming and/or reversible physicochemical or hydrodynamic interactions. Their accumulation rates or observed fluxes, less than diffusion-limit from the Leveque treatment, occur at a capture or engagement efficiency of less than 100%.

For the non-motile E. coli in this study, the Leveque treatment predicts a diffusion-limited cell accumulation rate of approximately 305 ± 35 cells per min per mm,2 included in Figure 5A as the gray horizontal bar. This estimate employs a free solution diffusion coefficient of approximately 4 ± 0.5 × 10−9 cm2/s for the cells, which were modeled as rods having a length of 2 ± 0.25 µm and a diameter of 0.5 ± 0.1 µm59 and shown to describe the behavior of gently flowing silica rods.60 This estimated transport limit exceeds the flux observed for the non-motile No-Flagella and No-Motor strains as expected, since not all surface encounters might produce engagements per Figure 4. Thus the engagement efficiencies of the non-motile cells are slightly less than 100%. The two motile strains exhibit a higher flux of engaging cells than is seen for passively diffusing cells. Indeed, the diffusive flux of the Super Swimmers and Parent strains exceeds the estimated diffusion-limited rate for cells of these sizes, an indication that cell motility contributes to the numbers of cells reaching and dynamically engaging the surface.

For motile cells the engagement process involves both swimming-enhanced transport to the interface followed by reversible hydrodynamic or physicochemical binding to form the engagement. In the case that hydrodynamic or physico-chemical bonds are formed with 100% efficiency, then the flux values in Figure 5A illustrate how the motility of the two strains enhances their transport, relative to diffusion from the bulk solution to the interface. Conversely if the formation of hydrodynamic or physicochemical bonds with the surface is inefficient, then one would estimate an even greater enhancement of motility to transport swimmers to the interface. Thus, a factor of three represents a lower bound for the impact of run and tumble motility to bring aggressively swimming cells within range to engage the surface.

Important to note is that non-motile populations within batches of the Super Swimmer and Parent cells are not distinguished in the engagement fluxes of Figure 5A. Non-motile fractions will encounter the surface through diffusion and would likely contribute fluxes similar to those of the No-Flagella and No-Motor strains. To the extent that the fluxes in Figure 5A contain some fraction of non-motile cells, the reported fluxes in Figure 5A represent a lower limit for the behavior of motile cells.

Number of Engagements per Cell

Figure 5A counts the numbers of cells reaching and engaging the surface per area and time. Since these engagements are reversible, cells may engage more than once within the field of view, as shown in the example of Figure 4. The numbers of engagements per cell is therefore presented in Figure 5B for the different strains. The Super Swimming cells exhibited much higher numbers of repeat surface engagements when compared with the other strains.

While the other strains had less than 10% of bacteria having 4 or more engagements 30% of the Super Swimmers had 4 engagements in the field of view. About 90% of Super Swimmers had multiple engagements while for the other 3 strains approximately half of the bacteria had only one engagement. While the exact statistics apply to the 260 µm-long field of view, the effective decay function in the repeat engagements is conceptually similar to a correlation function.

It is expected that even cells of the non-motile strains will have some number of repeat surface engagements. In order for the initial surface engagement to occur, a bacterium must first diffuse from the faster moving bulk streamlines to the slower moving near-surface streamlines. A recently disengaged cell may diffuse further from the surface, or it may re-engage. Cells that have diffused some distance from the surface possess a finite probability of returning to the interface where they can re-engage. An observed characteristic of diffusion-controlled repeat surface engagements of particles is a decrease in frequency of occurrence with the increased engagement numbers, as is seen for both the No Flagella and the No Motor strains. The distribution for Parent Strain also shows this characteristic but exhibits a more gradual decay. The Super Swimmers on the other hand display very different behavior in Figure 5B. Once an engaged Super Swimmer cell disengaged the surface, there is a ∼90% chance that it returns to the surface at least once more within the observation window.

Engagement Length and Time

Beyond the influence of motility and flagella on the cell flux to the surface and the numbers of engagements per cell, the bacterial character also affects the nature of the individual cell-surface engagements. One feature of engagements is their length or travel distance down the surface, another is the residence time of a cell on the surface during the engagement.

The distribution of travel distances during individual cell-surface engagements in Figure 6A depends on bacterial strain. Here it is seen that cells lacking flagella have a slightly longer travel distance along the surface compared with motile and non-motile cells containing flagella. This appears to be the case because cells lacking flagella tend to have fewer short-distance engagements compared with the other cells. The Super Swimmer cells are not remarkably different in their travel distance from flagella-containing cells of different motilities. The residence time per engagement in Figure 6B, is also strain-dependent with Super Swimmers and the No Flagella cells having statistically greater residence times than the other strains. No Motor cells have the smallest residence time. It is interesting that the engagement residence times of the Super Swimmers are mostly shorter than the broad distribution of free solution run times of 1–6 seconds reported for this strain,12 suggesting that motor reversal (tumbling) is not the reason for the disengagement of Super Swimmers from the surface.

Figure 6.

A) Distribution of Distance per Engagement. B) Durations of engagements equivalent to a cell’s residence time dynamically interacting with the surface in flow. Solid horizontal line: median; dashed horizontal line: mean; whiskers: range. The boxes bound the 25th-75th percentiles. C) Average velocity per engagement for engagements longer than 15 µm. Median lines are solid, and mean are dashed. Based on a student’s T-test, the *** indicate p < 0.01, that is the means for the different strains are statistically different to at least 99% certainty. The ** indicate p < 0.05 or differences between the pairs of strains indicated, to 95% certainty. In part C, the Super Swimmers differ from each of the other three strains with a t-test giving p< 0.01, while the other three strains are similar to each other. These results combine data for 25–35 bacteria per run with 3 runs per strain grown on different days. Only full engagements are included.

Average Engagement Velocity

Perhaps the most fundamental feature of a bacteria-surface engagement is the velocity at which a cell travels while it is engaged with the surface. Figure 6C summarizes the distribution of cell velocities during individual engagements, combining at least 25 cells per run for three runs with each cell type. Each velocity datum is an average of the instantaneous velocities observed during an engagement, as shown in the example of Figure 4. (If a cell later reengaged after leaving the surface, it produced a second velocity datum.) Engagements with overall travel distances below 15 μm or those entering and exiting the observation window were not included in Figure 6C; the latter due to the potential for averages to be skewed by the initial and final instantaneous velocities for short engagements. We generally observed no correlation between engagement length and velocity, justifying this approach. The key finding in Figure 6C is that average engagement velocity is much slower for the Super Swimmer cells than any of the other strains. The slower velocities of engaged Super Swimmers, combined with their slightly longer residence times cancel out to produce the unremarkable length of engaged travel down these surfaces. Indeed, considering only the distribution of traveled distances overlooks the distinctive features of the Super Swimming cells: their much slower travel along the surface and greater surface engagement times.

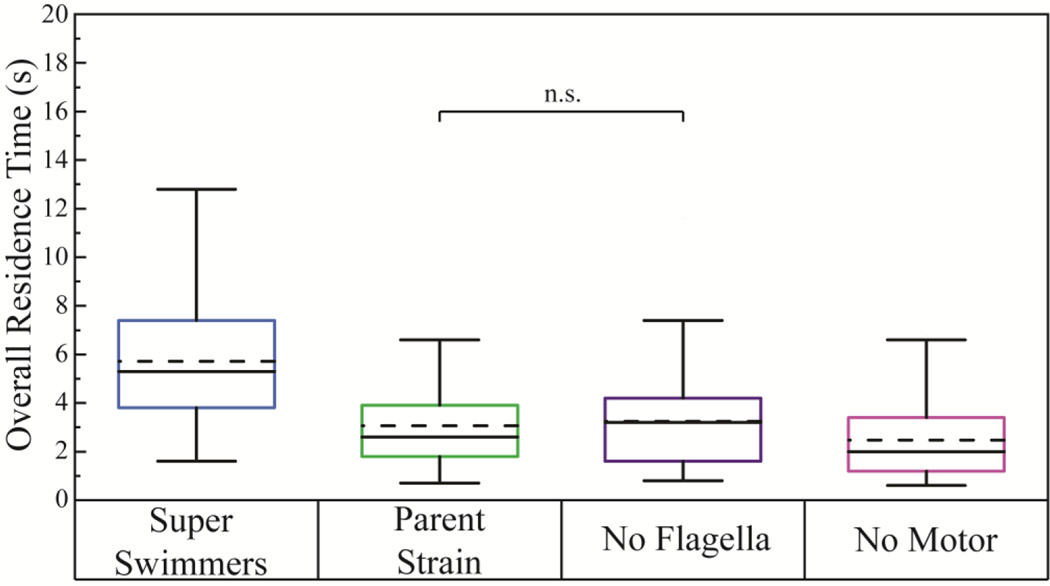

Overall Residence Time

The overall surface residence time of individual cells engaging the surface in the 260 µm field of observation, summing over the times of any multiple engagements, is shown in Figure 7. This metric provides a measure of the times the cells spend in contact with the surface, each having an opportunity to sense its physico-chemistry and mechanics. A bacterium that was engaged with the surface for the entire length of the observable flow cell would have an overall residence time of at least 29 seconds. The chance at such a long engagement in Figure 7 is, however, nearly impossible because we are not able to quantify the durations or average velocities of engagements that crossed into our out of the field of view. Therefore, the data necessarily bias towards shorter residence times, especially when bacteria had long or multiple engagements. Even so, Figure 7 shows that the Super Swimmer cells have longer integrated contact times by a significant amount, on the range of more than twice as much contact time per cell compared with the No Motor strain. Indeed, a substantial population of Super Swimmer cells had an integrated measurable residence time exceeding 10 seconds.

Figure 7.

Overall Residence time. Solid lines are the median value with dashed lines for the mean values. Unless otherwise noted, comparing pairs of strains using a student’s t-test, all strains were different from each other, with p<0.01. Partial engagements (bacteria leaves or enters the field of view while engaged) were included in this analysis. Three runs (each with data for 25–35- cells / run) for bacteria grown on different days for each strain were combined.

Discussion

By quantifying distributions of metrics describing the dynamics of individual near-surface cells, this study considered the possibility that, even without retention, the approach of flowing bacteria to within nanometers of PEG-functionalized surfaces could be sufficient to influence cells, for instance causing them to travel differently, or to prime them, through mechanosensing pathways or those sensitive to physico-chemical surface character, for downstream biofilm formation. The work also demonstrated that motile cells approach non-adhesive surfaces to within nanometers, explaining the ability of moving non-adhering cells to detect differences in the mechanics of chemically similar non-adhesive coatings having similar near-surface hydrodynamics.12 The study also demonstrated how the numbers of bacteria engaging in weak reversible surface interactions is described by classical transport treatment: a diffusion convection model with reversible adsorption for non-motile cells, or enhanced transport for motile cells. This motivates considering three steps for cell engagement: 1) transport to a surface to the point of encounter 2) reversible adsorption (here engagement as cells continue to travel down the surface with flow) and 3) disbonding. The study also quantified repeat reversible interactions for different cell types versus leaving the interfacial region.

Initial Engagement

Without motility, the flux of cells encountering a non-adhesive surface per area and time exhibits excellent agreement, in Figure 5A, with a classical diffusion-convection treatment.58 This is striking and unexpected because, while the classical treatment should describe non-motile cell approach to the region nearest the surface, it is seen to describe the numbers of reversible surface engagements, even though these engagements are representative of dynamic adhesion rather than non-adhesive collisions. The efficiency of “reversible capture” is therefore quite high, and even higher in swimming cells compared with non-motile analogs.

Near Surface Travel

Reversible interactions with a surface cause engaged cells to travel more slowly in flow than non-engaged cells. In Figure 6C cellular features substantially influence the travel velocities of engaged cells, providing clues into their surface interactions, which may include hydrodynamic attractions, reversible physicochemical attractions (eg van der Waals), bonds between different parts of the bacteria and the PEG brush for instance hydrogen bonding (producing rolling61), viscous drag or friction at the brush surface, or in the case of motile cells, swimming opposite the flow or pushing against the wall. Worth noting, Figure 6C reports velocities of entire engagements, with each engagement velocity being relatively constant, distinct from the larger velocity fluctuations before and after engagement. This engagement velocity contrasts with instantaneous velocities at each time step, for instance reported by automated tracking software. By reporting the engagement velocity, insight is gained into the interaction responsible for a particular engagement.

Most notable in Figure 6C is the slow engagement velocity of the Super Swimmers relative to the other strains, seemingly contradictory to the rapid travel of Super Swimmers in the motility plate assay. The slower Super Swimmers travel, deviating the most from free stream velocities suggests that Super Swimmers sustain the greatest interfacial forces to reduce their velocities from what they would otherwise be. Factors contributing to slow Super Swimmer travel at the wall likely include orientation of the cells at least partially against the flow direction. Super Swimmer cells could also be partially oriented towards the wall34 experiencing greater wall friction or physico-chemical interactions compared with the other strains, potentially rendering them more susceptible to mechanosensing and interfacial chemical sensing pathways compared with other cells.

An important point, prior measurements of bacterial swimming near surfaces report cell surface separations exceeding those of the DLVO potential.33 The large numbers of engaged cells in this study were all at separations estimated between 1 and 5 nm from the surface, with the Super Swimmer cells exhibiting the smaller of the separations in that window. The engaged cells in our study also appear to reside closer to the surface than cells swimming in circles in quiescence near solid or fluid interfaces.9–11

As an estimate of the forces that could be experienced by swimming cells, Chattopadhyay et al.62 report a forward swimming thrust force of 0.57 pN for E. coli HCB30 cells. With an approximate cross sectional length of 0.75 μm, a bacterium such as E. coli swimming into a PEG surface would exert a local normal stress, σ = thrust /(cross sectional length)2 of 1 Pa against a surface. Separately, engaged bacteria swimming near a surface experience tangential forces as well, evidenced by cell travel at a different velocity than that of non-engaged cells. Chattopadhyay et al.62 also report a flagellar torque of 5 × 10−19 Nm. With a swimming stroke radius on the order of 0.5 μm, a single flagella impinging on a surface as the cell swims along might impose a local normal stress, σ = (torque/ radius)/ contact area = 1pN / (0.02 μm2)= 50 Pa, where there is a very small contact area of 20 nm (the flagellar diameter) by 1 μm (a contact length) for a segment of one flagella. Future work will determine if these forces are adequate to produce changes in gene expression.

Duration of an Engagement: Disruptive Events

An engaged bacterium will travel along the surface until a disengagement event, such as a Brownian impulse, flagella kick, or an irregular tumble produces cell escape. Therefore the duration of engagements or surface residence times depend on the frequency of these disruptive events at the interface in flow.

Super Swimmers exhibit the longest residence times of the different cell types suggesting that, relative to non-motile or less motile cells, enhanced motility stabilizes cells at nanometric surface separations in flow. Yet, the duration of the engagements is still shorter than the run times between tumbles found for this strain.12 It may be possible that surface interactions influence the timing of motor reversal and flagellar rebundling, or swimming cells may depart the interface as a result of uneven swimming and collisions. Also interesting is that the No-Flagella cells have slightly extended long run times, indicating somewhat stable near-surface travel, likely including rolling motions and Brownian departure from the interface. The No Motor cells, having unbundled flagella may escape the surface through steric repulsions of flagella with the PEG surface. Overall, motility or the lack non-working or weakly working appendages favors longer times exposed to surface conditions.

We know of no previous works describing the duration of dynamic contact times of flowing bacterial cells with surfaces. While the apparent net tendency of motile bacteria and synthetic swimmers to swim towards walls is generally accepted, it is not generally understood how swimming bacteria cells leave an interface. The current report of finite surface engagement times for individual cells is therefore a significant finding. Indeed, in descriptions of the swimming of bacteria towards surfaces,32, 36 there is no mention continued long time cell accumulation, suggesting that bacteria do indeed have a finite residence times.

The significance of the bacterial residence time is also borne out in the distance cells travel along a surface, with the engagement length being the product of the engagement time and the average engagement velocity for each cell. Physically-significant features of contact can, however, be masked if only cell travel distances are reported.

Repeat Engagements and Integrated Engagement Time

Figure 5B demonstrates how, after a cell disengages the surface, motility drives the return of Super Swimmers to the surface, resulting in greater integrated surface interaction times for motile cells in Figure 7. This behavior is absent for the no-motor strain even though their (inactive) flagella could reach the surface from cell body-surface separations of many microns. Given that for Super Swimmers, the distribution of reengagements did not decay to zero after 4 engagements in the 260 µm field of view, it is likely that the same cells further reengaged the surface downstream, experiencing greater integrated engagement (residence) times than reported in Figure 7. The total surface residence times of Figure 7 therefore represent a lower limit for dynamic contact, and a distinguishing feature of highly motile bacteria. Further, the observed integrated surface contact times on the order of ten seconds for a substantial subpopulation of the engaging Super Swimmers begin to approach the known timescales of bacteria mechanosensing.40–42

Conclusions

This work demonstrated that in flow, bacteria traveling past minimally adhesive PEG surfaces experience substantial dynamic surface interactions bringing cell surfaces within nanometers of the PEG layer for extended periods of time, even though the cells do not arrest. This behavior, most pronounced for motile cells, may enable cells to sense surface features and expose them to near-surface physicochemical conditions or forces that initiate pathways associated with biofilm formation. Even though the cells are not retained on the PEG surface, if such pathways are initiated, the cells would be primed for biofilm formation on surfaces they may encounter downstream.

Swimming itself was found to be critical in producing extensive dynamic cell contact (to within 1–5 nm) with a non-adhesive wall in flow, evidenced in a comparison between an E. coli strain engineered for aggressive swimming and expressing greater numbers of flagella versus the parent strain or non-motile variants. Physicochemical interactions between non-active flagella and the surface were found to be insufficient produce such extensive dynamic surface contact. Run and tumble swimming motility, if substantial as evidenced in the Super Swimmer strain, can produce 3 times the flux of cells to the a near-surface region, and aggressive swimming can enable 3 times the cell-surface engagements per area and per unit time compared with non-motile strains. Motility, even in run-and tumble strains, can produce extended periods of engaged dynamic contact of individual cells with the surface for greater amounts of time than experienced by non-motile or weakly swimming cells. Further, after the dynamic surface contact of a cell concludes, swimming enables cells to return repeatedly to the surface, engaging in additional dynamic contact rather than swimming away. In this study 90% of Super Swimmers experienced at least one additional surface engagement within the field of view and 30% of engaging Super Swimmer cells experienced 4 such runs of dynamic contact. As a result of longer individual contact and repeat engagements per cell, motile cells could experience up to ∼10 seconds of dynamic surface contact on a length of surface in the field of view on the order of a quarter of a millimeter. Much more extensive contact likely occurs over the entire surface. The long per-cell dynamic contact time, combined with the larger population of dynamically engaging motile cells points to the possibility that significant numbers of flowing cells are altered by surface contact.

Supplementary Material

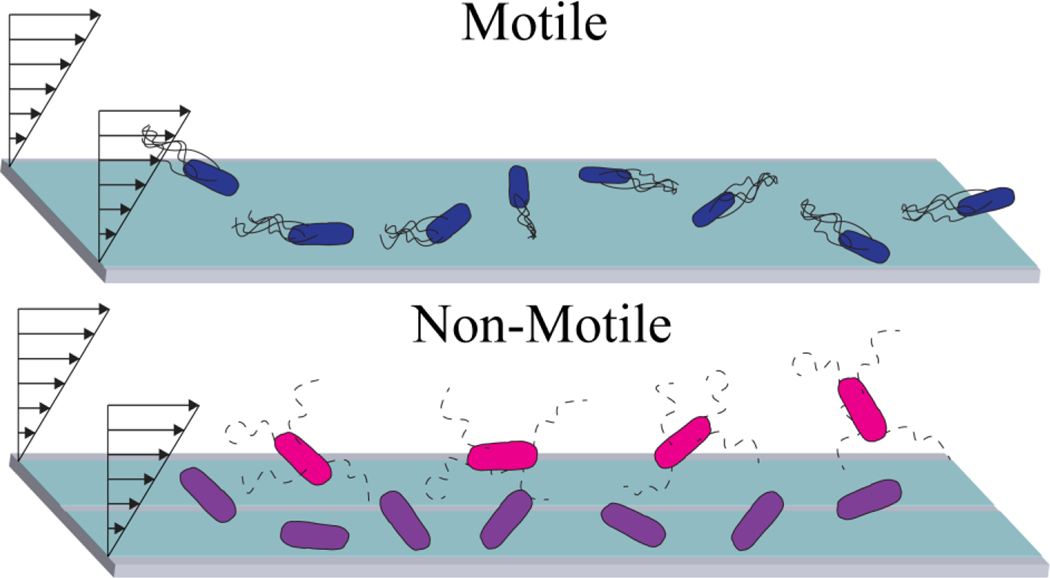

Figure 8.

Schematic of different stages of bacteria engagements. Initial encounters, near surface travel and escape. Flagella bundling reflects the literature models of E. coli swimming. Top: Super swimmers; Bottom: No motor and No Flagella strains

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported by NSF184806 and an NIH traineeship to M.K.S. under NIH National Research Service Award GM008515. The authors thank S. Kalasin for providing the copolymer to make the PEG brush surfaces and V. Raman for preparing bacteria.

References

- 1.O’Toole GA. To build a biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 2687–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costerton JW; Stewart PS; Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infections. Science 1999, 284, 1318–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedlander RS; Vlamakis H; Kim P; Khan M; Kolter R; Aizenberg J. Bacterial flagella explore microscale hummocks and hollows to increase adhesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 5624–5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misselwitz B; Barrett N; Kreibich S; Vonaesch P; Andritschke D; Rout S; Weidner K; Sormaz M; Songhet P; Horvath P; Chabria M; Vogel V; Spori DM; Jenny P; Hardt WD. Near Surface Swimming of Salmonella Typhimurium Explains Target-Site Selection and Cooperative Invasion. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiLuzio WR; Turner L; Mayer M; Garstecki P; Weibel DB; Berg HC; Whitesides GM. Escherichia coli swim on the right-hand side. Nature 2005, 435, 1271–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauga E; DiLuzio WR; Whitesides GM; Stone HA. Swimming in circles: Motion of bacteria near solid boundaries. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 400–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Leonardo R; Dell’Arciprete D; Angelani L; Iebba V. Swimming with an Image. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemelle L; Palierne JF; Chatre E; Place C. Counterclockwise Circular Motion of Bacteria Swimming at the Air-Liquid Interface. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 6307–6308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu JL; Wysocki A; Winkler RG; Gompper G. Physical Sensing of Surface Properties by Microswimmers - Directing Bacterial Motion via Wall Slip. Sci Rep 2015, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez D; Lauga E. Dynamics of swimming bacteria at complex interfaces. Phys. Fluids 2014, 26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morse M; Huang A; Li GL; Maxey MR; Tang JX. Molecular Adsorption Steers Bacterial Swimming at the Air/Water Interface. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, 21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shave MK; Xu Z; Raman V; Kalasin S; Tuominen MT; Forbes NS; Santore MM. Escherichia coli Swimming back Toward Stiffer Polyetheylene Glycol Coatings, Increasing Contact in Flow. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 17196–17206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarter L; Hilmen M; Silverman M. Flagellar Dynamometer Controls Swarmer Cell Differentiation of V. Parahaemolyticus. Cell 1988, 54, 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belas R. Biofilms, flagella, and mechanosensing of surfaces by bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hug I; Deshpande S; Sprecher KS; Pfohl T; Jenal U. Second messenger-mediated tactile response by a bacterial rotary motor. Science 2017, 358, 531–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cairns LS; Marlow VL; Bissett E; Ostrowski A; Stanley-Wall NR. A mechanical signal transmitted by the flagellum controls signalling in Bacillus subtilis. Molecular Microbiology 2013, 90, 6–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown DG; Hong Y. Impact of the Charge-Regulated Nature of the Bacterial Cell Surface on the Activity of Adhered Cells. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology 2011, 25, 2199–2218. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimkes TEP; Heinemann M. How bacteria recognise and respond to surface contact. Fems Microbiology Reviews 2020, 44, 106–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong YS; Brown DG. Variation in Bacterial ATP Level and Proton Motive Force Due to Adhesion to a Solid Surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 2346–2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuk HG; Marshall DL. Adaptation of Escherichia coli O157 : H7 to pH alters membrane lipid composition, verotoxin secretion, and resistance to simulated gastric fluid acid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 3500–3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolewe KW; Kalasin S; Shave M; Schiffman JD; Santore MM. Mechanical Properties and Concentrations of Poly(ethylene glycol) in Hydrogels and Brushes Direct the Surface Transport of Staphylococcus aureus. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces 2019, 11, 320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng QM; Zhou X; Wang Z; Xie QY; Ma CF; Zhang GZ; Gonge XJ. Three-Dimensional Bacterial Motions near a Surface Investigated by Digital Holographic Microscopy: Effect of Surface Stiffness. Langmuir 2019, 35, 12257–12263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee CK; de Anda J; Baker AE; Bennett RR; Luo Y; Lee EY; Keefe JA; Helali JS; Ma J; Zhao K; Golestanian R; O’Toole GA; Wong GCL. Multigenerational memory and adaptive adhesion in early bacterial biofilm communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 4471–4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haiko J; Westerlund-Wikstrom B. The Role of Bacterial Flagellum in Adhesion and Virulence. Biology 2013, 2, 1242–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Besser RE; Lett SM; Weber JT; Doyle MP; Barrett TJ; Wells JG; Griffin PM. An Outbreak fo Diarrhea and Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome from Escherichia Coli 157-H7 in Fresh Pressed Apple Cider Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association 1993, 269, 2217–2220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Ongoing Multistate Outbreak of Eschherichia Coli Serotype O157-H7. Infections Associated with Consumption of Fresh Spinach. Morbid. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2006, 55, 1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scallan E; Hoekstra RM; Angulo FJ; Tauxe RV; Widdowson MA; Roy SL; Jones JL; Griffin PM. Foodborne Illness Acquired in the United States-Major Pathogens. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2011, 17, 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hetrick EM; Schoenfisch MH. Reducing implant-related infections: active release strategies. Chemical Society Reviews 2006, 35, 780–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauga E; Powers TR. The hydrodynamics of swimming microorganisms. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2009, 72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lushi E; Wioland H; Goldstein RE. Fluid flows created by swimming bacteria drive self-organization in confined suspensions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 9733–9738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marchetti MC; Joanny JF; Ramaswamy S; Liverpool TB; Prost J; Rao M; Simha RA. Hydrodynamics of soft active matter. Reviews of Modern Physics 2013, 85. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berke AP; Turner L; Berg HC; Lauga E. Hydrodynamic attraction of swimming microorganisms by surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vigeant MAS; Ford RM. Interactions between motile Escherichia coli and glass in media with various ionic strengths, as observed with a three-dimensional-tracking microscope. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3474–3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vigeant MAS; Ford RM; Wagner M; Tamm LK. Reversible and irreversible adhesion of motile Escherichia coli cells analyzed by total internal reflection aqueous fluorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2794–2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClaine JW; Ford RM. Reversal of flagellar rotation is important in initial attachment of Escherichia coli to glass in a dynamic system with high- and low-ionic-strength buffers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 1280–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li GL; Bensson J; Nisimova L; Munger D; Mahautmr P; Tang JX; Maxey MR; Brun YV. Accumulation of swimming bacteria near a solid surface. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rusconi R; Guasto JS; Stocker R. Bacterial transport suppressed by fluid shear. Nat. Phys. 2014, 10, 212–217. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcos Fu, C. H; Powers TR; Stocker R. Bacterial rheotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 4780–4785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill J; Kalkanci O; McMurry JL; Koser H. Hydrodynamic surface interactions enable Escherichia coli to seek efficient routes to swim upstream. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lele PP; Hosu BG; Berg HC. Dynamics of mechanosensing in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 11839–11844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nord AL; Gachon E; Perez-Carrasco R; Nirody JA; Barducci A; Berry RM; Pedaci F. Catch bond drives stator mechanosensitivity in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, 12952–12957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tipping MJ; Delalez NJ; Lim R; Berry RM; Armitage JP. Load-Dependent Assembly of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. mBio 2013, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baba T; Ara T; Hasegawa M; Takai Y; Okumura Y; Baba M; Datsenko KA; Tomita M; Wanner BL; Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Molecular Systems Biology 2006, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu XY; Matsumura P. The FLHD FLHC Complex, A Transcriptional Activator of the Eschericia-Coli Flagellar Class-II Operons. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 7345–7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen CC; Saier MH. Structural and phylogenetic analysis of the MotA and MotB families of bacterial flagellar motor proteins. Res. Microbiol. 1996, 147, 317–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang B; Gon S; Park M; Kumar KN; Rotello VM; Nusslein K; Santore MM. Bacterial adhesion on hybrid cationic nanoparticle-polymer brush surfaces: Ionic strength tunes capture from monovalent to multivalent binding. Colloid Surf. B-Biointerfaces 2011, 87, 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morales-Soto N; Anyan ME; Mattingly AE; Madukoma CS; Harvey CW; Alber M; Deziel E; Kearns DB; Shrout JD. Preparation, Imaging, and Quantification of Bacterial Surface Motility Assays. Jove-Journal of Visualized Experiments 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gon S; Fang B; Santore MM. Interaction of Cationic Proteins and Polypeptides with Biocompatible Cationically-Anchored PEG Brushes. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 8161–8168. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu ZG; Santore MM. Poly(ethylene oxide) adsorption onto chemically etched silicates by Brewster angle reflectivity. Colloid Surface A 1998, 135, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gon S; Bendersky M; Ross JL; Santore MM. Manipulating Protein Adsorption using a Patchy Protein-Resistant Brush. Langmuir 2010, 26, 12147–12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gon S; Santore MM. Sensitivity of Protein Adsorption to Architectural Variations in a Protein-Resistant Polymer Brush Containing Engineered Nanoscale Adhesive Sites. Langmuir 2011, 27, 15083–15091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kenausis GL; Voros J; Elbert DL; Huang NP; Hofer R; Ruiz-Taylor L; Textor M; Hubbell JA; Spencer ND. Poly(L-lysine)-g-poly(ethylene glycol) layers on metal oxide surfaces: Attachment mechanism and effects of polymer architecture on resistance to protein adsorption. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 3298–3309. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalasin S; Letteri RA; Emrick T; Santore MM. Adsorbed Polyzwitterion Copolymer Layers Designed for Protein Repellency and Interfacial Retention. Langmuir 2017, 33, 13708–13717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kearns DB. A field guide to bacterial swarming motility. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 634–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swiecicki JM; Sliusarenko O; Weibel DB. From swimming to swarming: Escherichia coli cell motility in two-dimensions. Integrative Biology 2013, 5, 1490–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blair DF; Berg HC. The MotA Protein of Escherichia Coli is a Proton-Conducting Component of the Flaggelar Motor. Cell 1990, 60, 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldman AJ; Cox RG; Brenner H. Slow Viscous Motion of a Sphere Parallel to a Plane Wall. 2. Couette Flow. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1967, 22, 653–660. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leveque MA. Les Lois de la Transmission de Chaleur par Convection. Ann. Mines 1928, 13, 201–299. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ortega A; de la Torre JG. Hydrodynamic properties of rodlike and disklike particles in dilute solution. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 9914–9919. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shave MK; Balciunaite A; Xu Z; Santore MM. Rapid Electrostatic Capture of Rod-Shaped Particles on Planar Surfaces: Standing up to Shear. Langmuir 2019, 35, 13070–13077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kalasin S; Santore MM. Near-Surface Motion and Dynamic Adhesion during Silica Microparticle Capture on a Polymer (Solvated PEG) Brush via Hydrogen Bonding. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 334–343. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chattopadhyay S; Moldovan R; Yeung C; Wu XL. Swimming efficiency of bacterium Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 13712–13717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.