Abstract

Introduction:

Alopecia areata (AA) manifests as patchy hair loss and intralesional corticosteroid (ILCS) is usual therapeutic choice in limited disease. Microneedling is used for uniform delivery of topical agent to relatively larger areas may prove to be more efficacious than traditional ILCS. The present study prospectively compared microneedling to traditional intralesional delivery of triamcinolone acetonide (TA).

Materials and Methods:

Prospective randomized comparative study in 60 patients of AA restricted to scalp not requiring systemic treatment randomly divided into two equal groups. Group 1 patients underwent microneedling with local application of injectable TA and Group 2 patients were given injectable TA intradermally for a total of three sessions at 3 weeks interval.

Results:

A mean regrowth of 66.36% in Group 1 and 69.75% in Group 2 at week 9 was seen which was comparative with no significant statistical difference between the two groups (P = 0.664). Thirteen patients achieved 100% regrowth at week 9 in Group 1 and 16 patients achieved 50%–99% regrowth in Group 2.

Discussion and Conclusions:

ILCSs have been cornerstone in the treatment of limited AA, but depth of injecting drug cannot be controlled, microneedling whereas is an effective drug delivery system and also causes release of growth factors. In this study, injectable TA used intralesionally and topically with microneedling had nearly similar efficacy in causing regrowth of hair with microneedling resulting in a more uniform but less dense regrowth of hair with lesser adverse effects.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, intralesional corticosteroid, microneedling, triamcinolone acetonide

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common, autoimmune, nonscarring, organ-specific disease manifesting as patchy hair loss.[1,2] Besides spontaneous resolution, AA has relapsing course, treatment is empirical and multitude of treatment options such as local therapies, systemic agents, and biologics are available.[3] Intralesional corticosteroid (ILCS) is usual therapeutic choice in limited disease but has limitation of use only for restricted surface area and may cause a nonuniform pattern of regrowth.

Microneedling is minimally invasive procedure involving controlled superficial puncturing of skin and has been shown to stimulate hair growth in murine model.[3,4] In addition, as drug delivery system, it can be used for uniform delivery of topical agent to relatively larger areas of alopecia at defined depth and decreases inter operator skill variability and subjectivity. Considering these factors, microneedling may prove to be more efficacious than traditional ILCS. The present study prospectively compared microneedling to traditional intralesional delivery of triamcinolone acetonide (TA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective randomized comparative study was conducted with due approval of Institutional Ethics Committee and informed consent of the participants. Sixty patients of AA above 18 years age diagnosed clinically and independently by two dermatologists and fulfilling the inclusion criteria of AA restricted to scalp not requiring systemic treatment were recruited. Patients previously treated for AA in the past 12 weeks or having any autoimmune or systemic illness were excluded.

A detailed pretreatment history and clinical examination was recorded with emphasis on duration, extent, size, and type of AA. Patches of alopecia were mapped on a transparent sheet and a graph sheet to calculate the area of each patch in cm square. Patients were randomly divided into two groups of 30 each for treatment with two different methods and a same dose of injectable TA (10 mg/ml) was used in a dose of 0.1 ml/cm2 area.

Group 1

Patients underwent microneedling with local application of injectable TA. The total calculated dose was divided in two equal parts to be used before and after microneedling. Under aseptic precautions, the dermaroller of needle size 1.5 mm was moved on the scalp patches diagonally, vertically, and horizontally 4–5 times in each direction. The pin point bleeding was taken as the end point. After the procedure, the patient was asked to not wash the treated area for the next few hours.

Group 2

Patients were given injectable TA intradermally with disposable insulin syringe.

All patients received total of three sessions at 3 weeks interval (0, 3, and 6 weeks) and were assessed for clinical improvement at each visit with final assessment done after 3 weeks of last session (9 weeks). Regrowth and response was evaluated with help of a hair regrowth scale. (A0 = no change or further loss, A1 = 1%–24% regrowth, A2 = 25%–49% regrowth, A3 = 50%–74% regrowth, A4 = 75%–99% regrowth, and A5 = 100% regrowth). The patient was also evaluated for uniformity of regrowth and any side effects such as atrophy, telangiectasia, or pigmentary change. Clinical photographs in same position were taken and labelled by specific numbers for each patient before starting the treatment and at each follow-up visit.

The normality of the variables was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test/Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests of normality. The data were analyzed using the comparison of values with Mann–Whitney test for two groups, Wilcoxon signed-rank test for variables and group comparisons using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test (IBM SPSS STATISTICS version 22.0). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The mean age of onset of disease in all the patients was 27.35 ± 8.48 years and was comparable in two study groups (Group 1 – 28.93 ± 9.436; Group 2 – 25.77 ± 7.229). The duration of disease ranged between 1 and 64 weeks, with a mean duration of 13.27 ± 15.5 weeks.

Among 60 patients treated, 56 patients completed the study and were eligible for the analysis. Four patients left the study (three due to development of adverse effects and one due to complete regrowth of hair after the first session).

Mean area of lesions at week 0 was 13.87 cm2 in Group 1 and 10.20 cm2 in Group 2 which decreased to 13.53 cm2 and 8.67 cm2 at week 3 and, 13.38 cm2 and 6.37 cm2 at week 6 and, 11.96 cm2 and 3.60 cm2 at week 9 in the two groups, respectively. The decrease in area was more significant in Group 2 at week 6 itself with P = 0.002.

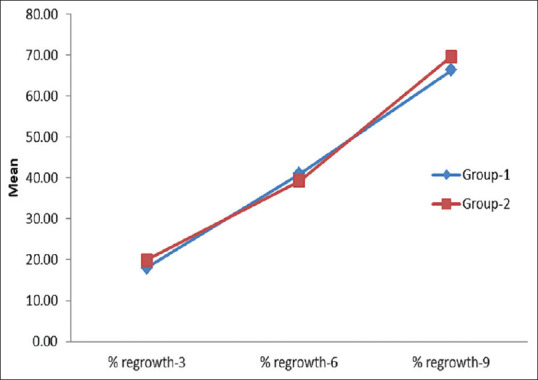

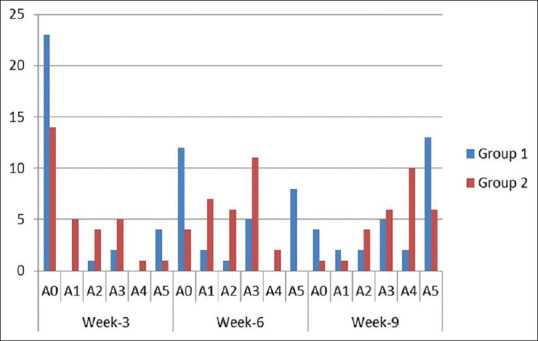

In Group 1, a mean regrowth of 18.07% was observed at week 3, 41.00% at week 6 and 66.36% at week 9. Similarly, in Group 2, 19.97% at week 3, 44.00% at week 6, and 69.75% at week 9. Subsequently, the regrowth was comparative with the treatment methods with no significant statistical difference between the two groups at week 9 (P = 0.664) [Figure 1]. Thirteen patients achieved 100% regrowth at week 9 in Group 1 and 16 patients achieved 50%–99% regrowth in Group 2 [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Trends in percent regrowth observed in Group 1 and Group 2

Figure 2.

Grade distribution of hair regrowth in Group 1 and Group 2

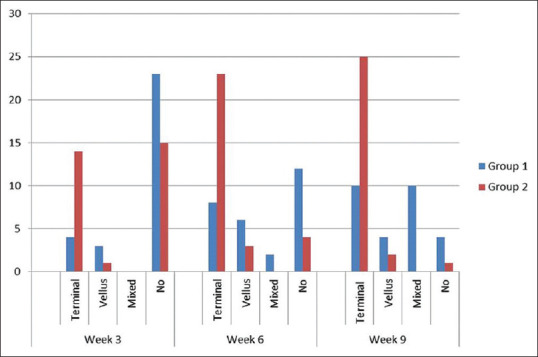

Four patients in Group 1 showed terminal type of hair on regrowth and three vellus type whereas as many as 14 patients showed terminal hair in Group 2 at week 3. At week 6, eight, six, and two patients showed terminal, vellus, and mixed type in Group 1 but 23 patients showed terminal type of hair in Group 2 and only three vellus and none mixed hair. Ten patients each had terminal and mixed regrowth in Group 1 and 25 patients in Group 2 showed terminal hair at week 9 [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Type of hair observed on regrowth in Group 1 and Group 2

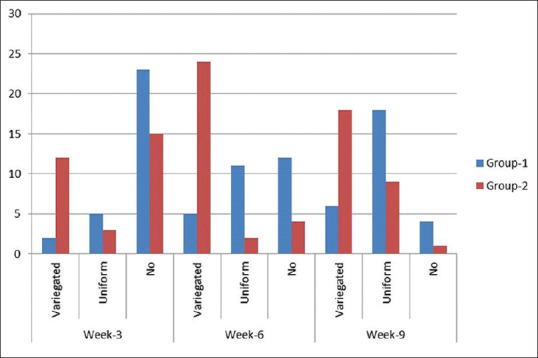

Two patients of Group 1 showed variegated and five uniform regrowth over the patch at week 3, whereas only three patients showed uniform regrowth and 12 with variegated in group 2. Group 1 patients continued to show a uniform regrowth with 11 and 18 patients, respectively, at week 6 and 9 as compared to only two patients showing uniform growth at week 6 and nine at week 9 with majority of them (18) showing a variegated regrowth [Figures 4 and 5].

Figure 4.

Pattern of distribution of regrowth in Group 1 and Group 2

Figure 5.

(a) Group 1 patient showing uniformly distributed sparse terminal hair over the whole patch (b) Group 2 patient showing variegated dense sparse terminal hair over the patch

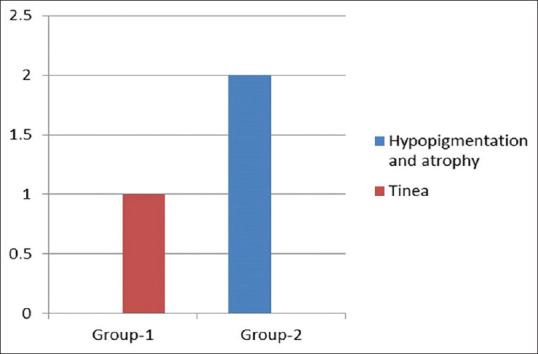

Adverse events were noted in only three patients. One patient in Group 1 developed an erythematous annular scaly plaque of the patch, diagnosed as dermatophyte infection. Other two patients developed hypopigmentation and atrophy over the patch (group 2) [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Adverse effects observed

DISCUSSION

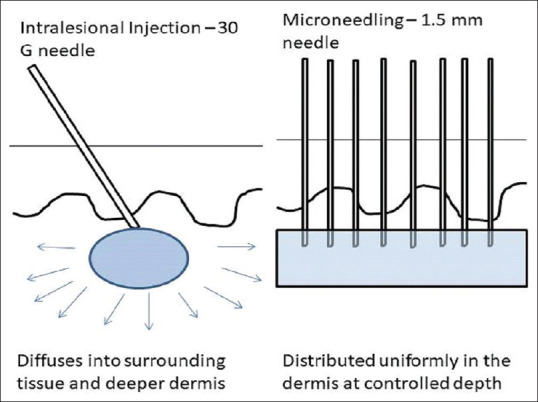

Although ILCSs have been cornerstone in treatment of limited AA, it is often associated with adverse effect of hypopigmentation, atrophy. The depth of injecting drug cannot be controlled, and the results are thus physician dependent.[5]

In the current study, dermaroller of size 1.5 mm has been selected taking reference from a case series where patients of AA were treated with microneedling with TA.[6] Similarly, suspension of TA is preferred as it has small particle size, does not crystallize, re-suspends easily on shaking. Risk of small emboli and vessel occlusion is lesser due to the small particle size and it diffuses partially through the surrounding tissue.

Mean regrowth of 66.36% uniformly distributed over the lesion observed in Group 1 is consistent with two case series defining the role of microneedling in AA by Chandrashekar et al. and Deepak and Shwetha et al.[6,7] In both these case series, treatment-resistant patients of widespread AA were selected and microneedling helped in treatment of a larger area reducing the risk of adverse effects and causing a more uniform distribution of TA resulting in a more uniform regrowth.[8,9] The present study, however, evaluated the response to treatment objectively so the observed regrowth can be solely attributed to effect of microneedling in delivering the drug and stimulating hair growth in patients.

A mean variegated regrowth of 69.75% was seen in patients of intralesional group (Group 2). The variegated regrowth of hair sparing few areas of the lesion was seen due to creation of small depot areas of TA at a distance of 1 cm. ILCS, specifically TA has been used as treatment modality since many years and in different doses. Its efficacy has also been compared with many other treatment options. The results of the present study are consistent with various studies in the patients of AA.[10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]

ILCSs are directly deposited in bolus doses in the papillary dermis from where it may diffuse into the surrounding tissue, thereby exerting its anti-inflammatory action over multiple surrounding hair follicles lying at varying depths in the dermis in the injected area. In addition, intralesional injections are an uncontrolled blind method of injection wherein the depth of injection is manually controlled and dependent upon the expertise of physician. A deeper injection into the dermis may get absorbed into the bloodstream and fail to exert a clinical response, whereas a more superficial injection may result in atrophy.[18] Microneedling acts similarly by creating microchannels through which the drug is delivered directly into the dermis at a uniform predetermined depth corresponding to needle size in microneedling with limited diffusion of TA into the surrounding tissue and deeper follicles [Figure 7]. Difference in grade of regrowth by both the modalities can be attributed to even effect of microneedling over the treated area when compared with ILCS which fail to show regrowth in areas where bolus dose may not have reached. Although in microneedling group, regrowth of hair was 100% in 46.4% patients, it was not dense enough to conceal the original patch and the margins of lesion could still be appreciated and discerned from the surrounding scalp. In contrast, the patients in intralesional group showed a denser regrowth of hair and the margins of lesion merge with the surrounding normal hair and blurring the margins of the patch.

Figure 7.

Pictorial diagram depicting the mechanics of intralesional injection and microneedling

Patients in the microneedling group showed both terminal and vellus type of hair on regrowth. Vellus hair are indicative of early disease remission and inversely related to disease activity as demonstrated by Mahmoudi et al.[19] Vellus hair usually regain their pigment and thickness to become terminal hair which was also seen in our patients.[20] In contrast in intralesional group, most patients showed dense terminal type of hair on regrowth but vellus type of regrowth was also seen in a few patients. The initial type of hair on regrowth is difficult to predetermine and depends on the individual patient. Some show an initial vellus hair which gets pigmented and others directly terminal type of hair on regrowth independent of treatment modality.

Microneedling in addition of acting as an effective drug delivery system also causes release of growth factors such as epidermal growth factors, platelet-derived growth factor due to microinjuries and stimulates hair growth by activating Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway. This stimulatory effect takes longer to develop, and therefore, a longer follow-up might help in appreciating a better regrowth density with microneedling.[4]

The present study did not show any serious adverse effects. Two patients in the intralesional group developed hypopigmentation and atrophy over the patches which is a known adverse effect of ILCSs and has been reported by others.[11,12,16,21,22] One patient in the microneedling group developed a plaque of tinea over the patch and probably developed this secondary fungal infection due to auto-inoculation for lesions of tinea corporis present elsewhere.

In this study, both modalities have shown a clinically significant regrowth of hair; 66.36% in Group 1 and 69.75% in Group 2, with intralesional method showing a better, denser and more acceptable terminal hair response and microneedling group showing a more uniform pattern of regrowth which is less dense resulting in the appreciation of the patch even post treatment.

The present study establishes the preliminary efficacy of microneedling in AA and future research with larger needle sizes (>1.5 mm) and dense needle distribution over the dermaroller may result in a better and deeper penetration of TA and consequent more prompt clinical resolution of AA patches. Furthermore, a longer follow-up with treatment period of at least 3 months may result in better regrowth and help study the relapse rate.

Limitations

The sample size was small and the duration of follow-up was short in both treatment groups. A longer follow-up could have revealed a continued effect in resolution as well as relapse in AA. Patient satisfaction and patient feedback were not evaluated.

CONCLUSIONS

Injectable TA used intralesionally and topically with microneedling has nearly similar efficacy in causing regrowth of hair. Microneedling results in more uniform but less dense regrowth of hair in AA and may have lesser adverse effects as compared to ILCSs but needs to be confirmed in larger study. Longer follow-up with more treatment sessions may result in a better response in both the groups.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilhar A, Etzioni A, Paus R. Alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1515–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1103442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hon KL, Leung AK. Alopecia areata. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2011;5:98–107. doi: 10.2174/187221311795399291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsantali A. Alopecia areata: A new treatment plan. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:107–15. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S22767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YS, Jeong KH, Kim JE, Woo YJ, Kim BJ, Kang H. Repeated microneedle stimulation induces enhanced hair growth in a murine model. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:586–92. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.5.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro J. Current treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S42–4. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2013.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandrashekar B, Yepuri V, Mysore V. Alopecia areata-successful outcome with microneedling and triamcinolone acetonide. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:63–4. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.129989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deepak SH, Shwetha S. Scalp roller therapy in resistant alopecia areata. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:61–2. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.129988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes D. Minimally invasive percutaneous collagen induction. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005;17:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2004.09.004. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serrano G, Almudéver P, Serrano JM, Cortijo J, Faus C, Reyes M, et al. Microneedling dilates the follicular infundibulum and increases transfollicular absorption of liposomal sepia melanin. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:313–8. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S77228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porter D, Burton JL. A comparison of intra-lesional triamcinolone hexacetonide and triamcinolone acetonide in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:272–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb07230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narahari SR. Comparative efficacy of topical anthralin and intralesional triamcinolone in the treatment of alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996;62:348–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuldeep C, Singhal H, Khare AK, Mittal A, Gupta LK, Garg A. Randomized comparison of topical betamethasone valerate foam, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide and tacrolimus ointment in management of localized alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:20–4. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.82123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devi M, Rashid A, Ghafoor R. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide versus topical betamethasone valearate in the management of localized alopecia areata. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25:860–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubeyinje EP. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide in alopecia areata amongst 62 Saudi Arabs. East Afr Med J. 1994;71:674–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubeyinje EP, C’Mathur M. Topical tretinoin as an adjunctive therapy with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide for alopecia areata. Clinical experience in northern Saudi Arabia. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:320. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1997.tb03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganjoo S, Thappa DM. Dermoscopic evaluation of therapeutic response to an intralesional corticosteroid in the treatment of alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:408–17. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.110767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur S, Mahajan BB, Mahajan R. Comparative evaluation of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection, narrow band ultraviolet B, and their combination in alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2015;7:148–55. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.171568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madani S, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:549–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmoudi H, Salehi M, Moghadas S, Ghandi N, Teimourpour A, Daneshpazhooh M. Dermoscopic findings in 126 patients with alopecia areata: A cross-sectional study. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:118–23. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_102_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pratt CH, King LE, Jr, Messenger AG, Christiano AM, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17011. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abell E, Munro DD. Intralesional treatment of alopecia areata with triamcinolone acetonide by jet injector. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:55–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1973.tb06672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahab MA. Results of intralesional triamcinolone in the treatment of alopecia areata. J Bangladesh Coll Phys Surg. 2006;24:110–3. [Google Scholar]