Abstract

Ross syndrome is a rare clinical disorder of sweating associated with tonic pupil and areflexia. There are very few case reports of Ross syndrome in dermatology literature, most presenting with patchy hyperhidrosis. Here, we report two isolated cases who had presented to the emergency department with heat exhaustion. Multidisciplinary evaluations of the first case revealed focal anhidrosis, patchy hyperhidrosis, postural hypotension, absent deep tendon reflex, and tonic pupil while the second case had similar features except for postural hypotension, prompting the diagnosis of Ross syndrome. Presentation of these two patients highlights the importance of a high index of suspicion of dysautonomic disorder, interdisciplinary workup of a case of patchy anhidrosis, or hyperhidrosis, which may get missed in busy outpatient department (OPD) visit.

Keywords: Areflexia, heat exhaustion, postural hypotension, Ross syndrome, tonic pupil

INTRODUCTION

Ross syndrome (RS) is a rare, dysautonomic disorder of the peripheral nervous system of unknown etiology with selective degeneration of cholinergic fibers, characterized by a triad of unilateral or bilateral segmental anhidrosis or hypohidrosis, areflexia or hyporeflexia of deep tendons and tonic pupils.[1] It is postulated that Harlequin and Holmes Adie's syndromes are two extremes of the spectrum, with RS having features of both of them. Sudomotor involvement is an essential component but incomplete RS may not have either Adie pupil or hypo-/areflexia or both.[2] Approximately 80 cases have been reported worldwide, out of that 25 are from India so far.[3] Initial presentation in most of them has been either hyperhidrosis or patchy dryness of a part of the body. Associations with other autonomic dysfunction like headache, palpitation, syncope, diarrhea, and cough are very infrequent.[4] Here, we report two unusual cases who were diagnosed as RS on multidisciplinary evaluation after they presented to the emergency department with a history of heat exhaustion following long-distance running.

Case 1

A 39-year-old male was brought to the emergency room with an episode of syncope following a long run. He had tachycardia (pulse = 120/min), tachypnea (respiratory rate = 26/min), orthostatic hypotension (BP = 90/60 mmHg in sitting position), and patchy hyperhidrosis of the face and extremities. There was a history of a sense of uneasiness, palpitation, and increased sweating in the last 2 months. There was no history of trauma, drug intake, or substance abuse. There was no history suggestive of hypothyroidism, hypertension, diabetes, seizures, or central nervous system involvement. He had taken multiple consultations for dry patches on the body, intolerance to heat, patchy hyperhidrosis, palpitation, and feeling of uneasiness from different specialists without any definitive diagnosis over the past 3 years. Unfortunately, multiple evaluations revolved around his anxiety about the treatment of infertility. Further evaluations revealed absent biceps jerk, sluggish knee, and ankle jerk. There was abnormal Valsalva testing and tilt-table testing showed increased heart rate and increased systolic and diastolic pressure. Ophthalmological examination revealed binocular vision with normal acuity and Schirmer's test, but he had anisocoria (left pupil dilated more than right) and right tonic pupil [Figure 1]. Starch iodine confirmed anhidrosis over the left side of the face, patchy anhidrosis over the left upper limb, lower back with compensatory hyperhidrosis over the right lower limb, right side of the face, and right upper limb. Nerve conduction studies revealed evidence of a mild distal sensory polyneuropathy of the axonal type in the right lower limb. However, his baseline hematological, biochemical laboratory parameters, viral markers, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination, thyroid profile, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), antinuclear antibody (ANA) screening, electrocardiogram (ECG), two-dimensional (2-D) echocardiography, histopathology of anhidrotic skin, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain, and spine were essentially normal.

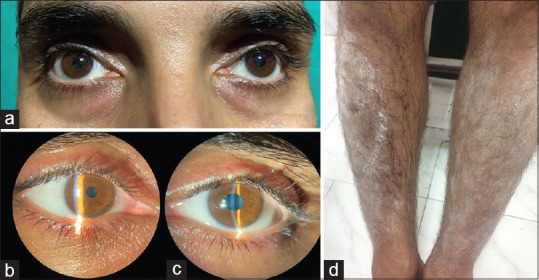

Figure 1.

Anisocoria of the pupil with dilatation of left pupil (a). slit lamp examination following pilocarpine eyedrops confirms dilatation of left pupil (b) with tonic left pupil (c). starch iodine test shows hyperhydrosis over right leg and anhidrosis over left leg (d)

Case 2

A 29-year-old male was brought to the emergency with complaints of weakness, muscle cramps, and a history of loss of consciousness following a long run. He had three similar episodes in the last 6 months. Every episode was diagnosed as a case of heat exhaustion, managed with only supportive care. Even though he did not have any underlying systemic disease, dermatological examination revealed patchy hyperhidrosis over the face, right forearm, right side of the chest, and right leg. There was relative anhidrosis in other areas of the body, which was confirmed by the starch-iodine test [Figure 2]. The deep tendon reflexes at the biceps, knees, and ankles on both sides were sluggish, however, the autonomic function test did not reveal any abnormality. Ophthalmological examination revealed binocular vision with normal acuity and Schirmer test but he had anisocoria (right pupil dilated than left) and left tonic pupil. A detailed investigation like in the first case including a nerve conduction study was essentially normal.

Figure 2.

Illustrates the anisocoria of the pupil with dilatation of the pupil on the right side (a). Starch iodine test shows the change in color on the right side of the face (b) and right forearm in comparison with the left (c)

Based on the characteristic history, patchy anhidrosis, compensatory hyperhidrosis, tonic pupil, sluggish, or absent deep tendon jerk, and absence of any underlying systemic disease, both cases were diagnosed as cases of RS.

DISCUSSION

RS, first described by Alexander Ross in 1958, is a rare dysautonomic disorder, with slight male preponderance but without any specific ethnic predisposition. RS can occur in any age group but has been diagnosed more often in the third decade of life.[1,2] Tonic pupil and hypohidrosis/anhidrosis can be explained by the affection of postganglionic cholinergic fibers projecting to the iris and sweat glands.[5] The pathogenesis of sluggish or lost tendon jerks remains obscure, however, it is suggested that it may be due to degeneration of dorsal root ganglia and spinal interneuron loss. Hyperhidrosis that is usually the presentation of the patients in response to exercise and hot weather is rather a compensatory phenomenon that happens due to the loss of cholinergic M2 inhibitor presynaptic autoreceptors.[6] Although the exact pathomechanism of this disease is unknown, there are few postulations of a causal relationship with autoimmunity, microvascular ischemia, and postinfectious origin.[1,2,3,4] Mishra et al. performed baseline tests (ANA, anti-/anti-SS-B) to rule out autoimmunity in 11 patients, findings suggest that RS may not be of autoimmune origin. Viral infections like cytomegalovirus have been associated with Ross syndrome.[7] Our first case had a history of mumps following which he noticed patchy hyperhidrosis on the face, which gradually progressed to involve other body parts associated with hypohidrosis and dryness. Even though a review of literature by Rajput et al.[8] found an interesting association with diabetes, both cases did not have any other systemic condition. The triad of widespread segmental anhidrosis, tonic pupil, and areflexia with orthostatic hypotension in our first patient showed a possible generalized injury to autonomic and dorsal root ganglia or efferents. Patients of RS often present with patchy hyperhidrosis, but this finding often gets overlooked or missed in busy OPD's. Heat exhaustion could have been prevented if they had been diagnosed earlier or counseled about the condition. Anhidrosis or hyperhidrosis may be due to diabetes, leprosy, polyneuropathy, harlequin syndrome, shy Drager syndrome, and multiple sclerosis but these disorders can easily be excluded as tonic pupil and areflexia are not the features in them. Patchy hyperhidrosis or anhidrosis should be worked up in detail in consultations with dermatologist, ophthalmologist, and neurophysician as RS is often missed or overlooked due to its rarity and unawareness about the condition. Treatment of this condition is largely symptomatic for the predominant symptoms but is often unsatisfactory. A combination of anhidrosis and hyperhidrosis may cause severe derangement of thermoregulation when exposed to strenuous physical exertion leading to heat exhaustion and heat stroke. Patchy hyperhidrosis can be managed with local application of 0.005% glycopyrrolate aqueous cream, iontophoresis, and local instillation of botulinum toxin type A. Troublesome hyperhidrosis, compromising the quality of life may require systemic anticholinergic drugs (glycopyrrolate, propantheline bromide, benztropine, and oxybutynin) and anxiolytics (beta-blockers, amitrypytiline, and fluoxetine) but anticholinergic adverse effects are their limitations. In addition, video-assisted sympathectomy can be attempted in refractory cases.[9] Systemic steroid and intravenous immunoglobulin can be tried if there is associated autoimmune condition.[10] Modifications of the environment, wearing wet clothes during strenuous physical activity, and other preventive coping strategies may prevent heat exhaustion and stroke. Our cases illustrate the importance of a high index of suspicion, simple bedside tests, multispecialty consultations, and detailed clinical evaluation in the diagnosis of this rare condition.

Statement of ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose. The authors confirm obtaining written consent from the patient for publication of the manuscript (including images, case history, and data).

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Neurophysician and Ophthalmologist Base Hospital Delhi Cantt, India.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mishra A, Kharkongor M, Kuriakose C, Georger A, Peter D, Carey R, et al. Is Ross syndrome an autoimmune entity? A case series of 11 patients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2017;44:318–21. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2016.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin RK, Galetta SL, Ting TY, Armstrong K, Bird SJ. Ross syndrome plus: Beyond Horner, Holmmes-Adie, and Harlequin. Neurology. 2000;55:1841–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.12.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwala MK, George L, Parmar H, Mathew V. Ross syndrome: A case report and review of cases from India. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:348. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.182472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacon PJ, Smith SE. Cardiovascular and sweating dysfunction in patients with Holmes-Adie syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:1096–102. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.10.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommer C, Lindenlaub T, Zillikens D, Toyka KV, Naumann M. Selective loss of cholinergic sudomotor fibers causes anhidrosis in Ross syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:247–50. doi: 10.1002/ana.10256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panda S, Verma D, Budania A, Bharti JN, Sharma RK. Clinical and laboratory correlates of selective autonomic dysfunction due to Ross syndrome. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:1500–3. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_151_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagane Y, Utsugisawa K. Ross syndrome associated with cytomegalovirus infection. Muscle Nerve. 2008;38:924–6. doi: 10.1002/mus.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajput CD, Gore SB, Malani SS, Shah SM. Ross syndrome and diabetes mellitus: An interesting association. Clin Dermatol Rev. 2020;4:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullaaziz D, Kaptanoglu AF, Eker A. Hypohidrosis or hyperhidrosis? Ross syndrome. Dermatol Sin. 2016;34:141–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasudevan B, Sawhney M, Vishal S. ANA positivity: A clue to possible autoimmune origin and treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:2746. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.70694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]