Abstract

Background: Latino men who have sex with men (LMSM) experience HIV and behavioral health disparities. Yet, evidence-based interventions, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and behavioral health treatments, have not been equitably scaled up to meet LMSM needs. To address quality of life and the public health importance of HIV prevention, implementation strategies to equitably scale-up these interventions to LMSM need to be developed. This study identifies themes for developing culturally grounded implementation strategies to increase the uptake of evidence-based HIV-prevention and behavioral health treatments among LMSM. Methods: Participants included 13 LMSM and 12 stakeholders in Miami, an HIV epicenter. Feedback regarding the content, design, and format of an implementation strategy to scale-up HIV-prevention and behavioral health services to LMSM were collected via focus groups (N = 3) and individual interviews (N = 3). Themes were inductively identified across the Health Equity Implementation Framework (HEIF) domains. Results: Analyses revealed five higher order themes regarding the design, content, and format of the implementation strategy: cultural context, relationships and networks, navigation of health information and systems, resources and models of service delivery, and motivation to engage. Themes were applicable across HEIF domains, meaning that the same theme could have implications for both the development and implementation of the implementation strategy. Conclusions: Findings highlight the importance of addressing culturally specific factors, leveraging relational networks, facilitating navigation of health systems, tailoring to available resources, and building consumer and implementer motivation in order to refine an implementation strategy for reducing mental health burden and achieving HIV health equity among LMSM.

Plain Language Summary

Latino men who have sex with men (LMSM) are diagnosed with HIV and experience mental health and substance use problems more than their non-Latino/non-MSM peers. This means there is a disparity: one group is burdened by a disease more than another group. There are interventions, like pre-exposure prophylaxis and mental health/substance use treatment that can address this disparity. But, LMSM do not have enough access to these. This means there is a healthcare disparity: one group does not have as much access to healthcare as another group. The purpose of this study was to create a program to help LMSM get these services and consider how to implement it. LMSM and potential implementers talked about factors to consider in developing this program and implementation. They said the program and implementation need to (1) consider the cultural context in which LMSM are embedded, (2) leverage LMSM and implementers’ networks, (3) increase LMSM and implementers’ ability to navigate complex health systems, (4) be tailored to the resources available to consumers and implementers, and (5) build consumer and implementer motivation. These factors are important to address when developing and implementing programs to help LMSM get HIV-prevention and behavioral health treatments.

Keywords: equity, HIV-AIDS, behavioral health services, Latino, LGBTQ populations, marginalized populations, qualitative methods, scale-out

Latino men who have sex with men (LMSM)1 face substantial HIV disparities. For example, LMSM experienced 22% of all new HIV diagnoses in 2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Yet, evidence-based interventions, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), have not been sufficiently scaled up and out to LMSM (Blashill et al., 2020; Harkness et al., 2021b; Kimball et al., 2020). PrEP use in the past year was reported by only 28% of US-born LMSM (Trujillo, 2019). This gap in the successful implementation and dissemination of PrEP perpetuates HIV disparities (Pinto et al., 2018) and inhibits progress toward the Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) plan (Fauci et al., 2019).

LMSM are also impacted by behavioral health (i.e., mental health and substance use) disparities, which worsen HIV disparities. The synergistic nature of HIV and behavioral health disparities is a “syndemic,” whereby both epidemics, situated in social inequities, synergistically worsen one another (Singer et al., 2006, 2017). In addition to behavioral health disparities, one type of syndemic driver, LMSM simultaneously navigate the impacts of racism and homophobia, which add to and amplify the multiplicative effects of HIV and behavioral health disparities (Mizuno et al., 2012). The additive impact of syndemic drivers, including but not limited to behavioral health problems, is associated with sexual behavior that can lead to HIV acquisition (Martinez et al., 2016; Mizuno et al., 2012). Yet, as with PrEP, evidence-based behavioral health treatments are insufficiently scaled up and out to LMSM. Among LMSM diagnosed with a mental health disorder, less than half received treatment (Burns et al., 2015), underscoring the need to link LMSM to treatment.

Prior research has identified barriers to LMSM’s PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatment uptake. Psychosocial (e.g., depression, substance use, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence) and structural (e.g., incarceration, unstable housing, poverty) syndemic drivers are associated with lower PrEP use among LMSM (Blashill et al., 2020). PrEP, HIV, and mental health stigma are pervasive barriers that impede PrEP use, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatment among LMSM (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Lelutiu-Weinberger & Golub, 2016; Solorio et al., 2013). Low perceived need or relevance of services can also impede PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatment among LMSM (Breslau et al., 2017; Cook et al., 2014; Harkness et al., 2021a).

Additionally, our formative research (the DÍMELO study) with LMSM and stakeholders (individuals who delivered HIV-prevention and behavioral health treatments to LMSM in South Florida) identified barriers and facilitators that need to be addressed to increase the reach of these services to LMSM. The qualitative aim of DÍMELO included LMSM (∼50% born outside the United States) and stakeholders and identified implementation determinants (Harkness et al., 2021a) using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Damschroder et al., 2009). Key determinants of HIV-prevention and behavioral health treatment use among LMSM included complexity of service access, perceived benefits of services, policies influencing service availability, patient needs and resources that could affect service use (e.g., transportation, education, immigration status, mental health/substance use), peer influence (e.g., peer stigma vs. normalization), LMSM and provider knowledge, provider/organizational relationships (e.g., stigma vs. affirmation, trust, personalism), and the availability of services. The quantitative aim of DÍMELO surveyed 290 LMSM in South Florida (∼50% born outside the United States) and identified additional determinants of LMSM’s demand for PrEP and behavioral health treatments (Harkness et al., Manuscript Under Review). For PrEP, key facilitators included knowledge, self-efficacy, community norms, and navigation support, whereas low perceived need was a barrier. For behavioral health treatment, key facilitators included a medical provider or personal contact recommending treatment, perceived need, and community norms, knowledge, and attributing mental health concerns to one’s environment or culture. In contrast, those who relied on family/friend support were less likely to engage in behavioral health treatment.

To address the ongoing, synergistic HIV and behavioral health disparities affecting LMSM, multilevel implementation strategies are needed that will: (1) increase LMSM demand for PrEP and behavioral health treatments and (2) equip implementers to deliver consumer-facing implementation strategies to increase LMSM demand for PrEP and behavioral health treatments. Here, we define implementation strategies as “methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of a clinical program or practice,” (Proctor et al., 2013, p. 2) with PrEP and behavioral health treatments being the clinical interventions. The current study’s goal is to engage in formative research to refine the consumer-facing and implementer-facing components of one potential implementation strategy to improve the reach of HIV-prevention and behavioral health treatments to LMSM, which we call “Dime Más” (“Tell me More”). Further, we seek to develop the implementation strategy with substantive community input, with community defined as both potential consumers of Dime Más, HIV-prevention services, and behavioral health treatments, as well as potential implementers of Dime Más. This is consistent with Pinto and colleagues’ (2021) guidance, who articulate the need for community engagement to be integrated more fully into existing dissemination and implementation models and efforts.

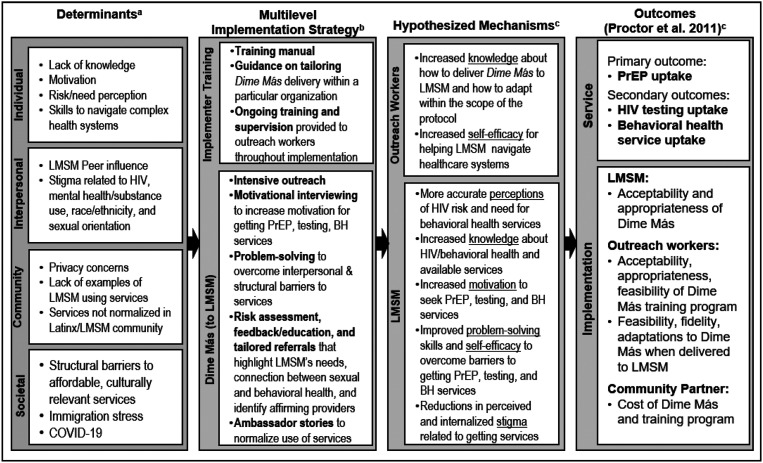

Based on our findings from the DÍMELO study (Harkness et al., Manuscript Under Review, 2021), we developed an initial framework for this implementation strategy, including a consumer-facing and provider-facing component (see Figure 1). We entitled the consumer-facing component, which aims to increase consumer demand, Dime Más. As shown in Figure 1, based on our findings from DÍMELO, we developed a preliminary version of Dime Más. The preliminary version is one session (approximately 60 min with three brief monthly boosters to balance ongoing engagement with feasibility) in which an LMSM outreach worker would utilize motivational interviewing, problem-solving, healthcare needs assessment and tailored referrals, and peer ambassador stories to increase LMSM consumers’ PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatment uptake. The implementation strategy was anticipated to take place in community health clinics (i.e., locations where outreach workers are already employed). Of note, although Dime Más unifies evidence-based behavior change techniques such as motivational interviewing (Naar-King et al., 2012; Outlaw et al., 2010), problem-solving (Gardner et al., 2014), peer education and linkage (Shangani et al., 2017), and self-affirmation (Walton & Cohen, 2011), Dime Más has not yet been tested on its own. The preliminary components of Dime Más were developed based on findings from the DÍMELO study; the current study seeks to refine Dime Más using LMSM and stakeholder feedback to enhance its impact and feasibility, while also identifying themes that could apply to other implementation strategies to achieve similar goals.

Figure 1.

Implementation research logic model.aImplementation determinants were identified in the DÍMELO study (Harkness et al., 2021).bThe focus of the current project is to conduct formative research to refine the implementation strategy.cHypothesized mechanisms and outcomes will be assessed in a subsequent pilot trial.

With the development of the preliminary version of Dime Más, there was a simultaneous need to develop an implementer-level component of the implementation strategy to facilitate delivering Dime Más. A key issue when researchers develop health promotion programs to increase consumers’ uptake of a clinical intervention is that implementation is not considered in the planning phase (Wisdom et al., 2014). This is evidenced by the traditional translational pathway, in which programs are developed, tested in controlled efficacy trials, followed by effectiveness trials, and finally, implementation trials (Brown et al., 2017). There is often a “voltage drop” with each step of the translational pathway (Chambers et al., 2013). As such, our goal in developing Dime Más is to consider implementation from the outset by centering the voices of potential implementers and LMSM consumers. Therefore, the current study also examined stakeholders’ (defined in this study as individuals who work with LMSM in HIV-prevention or behavioral health services in the Miami area) perspectives regarding potential implementation barriers and facilitators for Dime Más in their setting and sought feedback on strategies to implement Dime Más in their settings. As such, the findings suggest strategies needed to implement Dime Más and programs like it in community settings.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants included 13 LMSM and 12 stakeholders across three focus groups and three individual interviews. Focus groups (N = 3) were held in English and Spanish for LMSM (n = 2) and in English for stakeholders (n = 1). Three stakeholders who were not available to participate in the focus group were interviewed individually. LMSM were recruited via social media advertisements, a consent-to-contact database, and word of mouth. Stakeholders were recruited through our community partner network.

Eligible LMSM (a) identified as Latino/Hispanic, (b) identified themselves as a man who has sex with men (including gay, bisexual, and other MSM), (c) were between 18 and 39 years, (d) spoke English/Spanish, (e) self-reported HIV-negative or unknown HIV status, and (f) resided in the Miami area. Eligible stakeholders (a) were 18 to 65 years old and (b) worked with LMSM in HIV-prevention or behavioral health in the Miami area. Inability to provide consent, risk of harm from the study, or having a medical or psychiatric condition that would interfere with participation (determined as needed by PI, a licensed psychologist) were exclusion criteria.

Recruitment took place from December 2020 to April 2021. Prospective participants completed a phone screen and were scheduled if eligible. Some who consented to participate did not end up participating (N = 11). Following our IRB-approved protocol, participants reviewed consent information (e.g., study procedures, risks/benefits, voluntariness) within REDCap and checked “Yes, I consent to participate,” before completing study procedures via REDCap (demographic survey) and videoconferencing (interviews). Following participation, focus group participants received $50 and individual interviewees received $25.

Data collection

Demographic surveys

Demographic surveys assessed race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, and other key demographics. LMSM were asked about employment status, nativity, and citizenship. Stakeholders provided information about their organizational role.

Focus groups and interviews

Semi-structured focus group interview guides (see Supplemental File) were developed to assess the extent to which the initial version of Dime Más was acceptable, appropriate, and feasible to LMSM and stakeholders, and refinements to align Dime Más with the needs and priorities of LMSM and stakeholders. We adapted the focus group guide for individual interviews with stakeholders to ensure representation of stakeholders (e.g., across levels of organization and different organizations). Although the interview guides were not pilot tested, revisions were made based on feedback from research team members before administration. The first author wrote the first draft of the interview guide, which was iteratively revised across a series of consultations with coauthors with expertise in implementation science, health disparities, and HIV prevention. Feedback resulted in changes such as adding questions to probe the acceptability and appropriateness of specific innovative components of Dime Más (e.g., the peer ambassadors, the need for implementers to be LMSM) and streamlining the interview guide to reduce participant burden while still obtaining key information.

Interviewers first explained the purpose of the interview, which was to develop a program to increase PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatment uptake among LMSM in South Florida, and ensure this program addresses the needs and priorities of potential consumers and implementers. We presented the initial version of Dime Más, including its content, format, and design, and the basic framework of the training for Dime Más implementers. Participants were asked about the acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility of Dime Más. Stakeholders were probed about implementing Dime Más, including implementation barriers and facilitators within their settings. Focus groups and interviews were conducted via videoconferencing and lasted approximately 90 min and 30–60 min, respectively. Although transcripts were not shared with participants, LMSM and stakeholders were given the option to provide additional comments after the interview via a web-link or email (none elected to do so). Only participants and interviewers were present for data collection.

Research team

Five research team members conducted the focus groups and individual interviews. Interviewers varied by gender/sexual orientation (cisgender heterosexual women and cisgender sexual minority men), race/ethnicity (Latina/o, White), and academic training/discipline (psychologist/faculty in public health, doctoral students in public health and psychology, and research assistants in psychology). We strived to “match” interviewers with participants. For example, LMSM focus groups were conducted by interviewers with shared identity concerning sexual orientation, gender, and/or ethnicity. Bilingual/bicultural interviewers carried out the Spanish-language focus group. Stakeholder interviews were conducted by team members who delivered HIV-prevention and behavioral health treatments. Although the degree to which qualitative interviewers reflect “insider” versus “outsider” status has been debated in the literature in terms of benefits and drawbacks (Hoong Sin, 2007; Wray & Bartholomew, 2010), we had a team of researchers with shared experiences and therefore elected to leverage the potential benefits of this in terms of building trust and engagement while also utilizing reflexive engagement to address the reality that all interviewers still brought their lived experiences which may have shaped their probing and interpretation of participant responses.

The first author developed the team based on their academic backgrounds and commitments to health equity among sexual minority and Latino/a/x2 communities. Most team members conducted prior research and/or had preexisting relationships with local stakeholders, facilitating recruitment, and rapport. Some participants previously participated in the DÍMELO study (Harkness et al., Manuscript Under Review, 2021) and were aware of the team’s goals and research. Although all team members had prior experience conducting qualitative research on HIV and behavioral health among LMSM, the first author provided initial training on the interview guide and analytic approach. Analyses were carried out by the first author and two doctoral students (second and third authors) and verified by all team members. Team meetings provided opportunities to practice reflexivity (Morrow, 2005) surrounding the extent to which our identities and experiences influenced our interviewing and data analysis approach.

Qualitative analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. Two qualitative analytic approaches were used: the framework and the general inductive approaches. The framework approach, recommended for qualitative implementation research (National Cancer Institute, 2018), involves applying an existing framework to analyze qualitative data. In our case, the Health Equity Implementation Framework (HEIF; Woodward et al., 2019, 2021) served as the framework. This framework articulates domains that impact the implementation of an innovation, including (a) the innovation itself, (b) the consumers of the innovation, (c) the implementers of the innovation, (d) the clinical interaction between implementers and consumers, (e) the inner context in which the innovation is delivered, and (f) the outer context in which consumers, implementers, and inner contexts are situated.

We combined the framework approach with the general inductive approach (Thomas, 2006). Using this approach allowed us to identify emergent themes from the qualitative data that were mapped onto the HEIF domains. Two analysts repeatedly reviewed the transcripts and independently identified lists of codes and their corresponding HEIF domains. The lead author then reviewed transcripts and analyst notes to develop the codebook. The codebook formed a matrix, with codes (later consolidated into higher order themes) identified on the vertical axis and the HEIF domains on the horizontal axis. Each code could intersect with any HEIF domains (Table 1). The analysts then independently applied the codebook to the transcripts. The lead author reviewed for consensus and documented in NVivo 12. Where there was disagreement between analysts, the team discussed to consensus and added/revised codes. Throughout the data collection process, we were coding the data and tracking thematic saturation. Evidencing saturation, no new codes were added for the final three transcripts (Guest et al., 2016). In other words, as we were collecting and coding data from the first three transcripts, new codes emerged, whereas we stopped identifying new codes in the final three, which informed us that we had reached saturation and could discontinue enrolling new participants. Upon coding completion, the team identified five major content themes within which the codes were consolidated. Of note, we utilized several recommended methods for enhancing the trustworthiness of our qualitative findings, including using multiple coders for all transcripts, including a multidisciplinary team with a range of lived experiences/identities, implementing a reflexive consensus-building process with a third analyst at each coding meeting, using coding disagreements and unique perspectives to enrich the analysis, and transparently reporting our analytic approach (Armstrong et al., 1997; Hemmler et al., 2020; Mays & Pope, 2000; Morrow, 2005; Saldana, 2015; Sweeney et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Codebook matrix.

| Higher order themes | Codes | Health Equity Implementation Framework Domains | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Innovation (Dime Más Protocol) | II. Clinical encounter | III. Patient | IV. Provider (Implementer) | V. Inner context | VI. Outer context | ||

| Cultural Context | Stigma | Dime Más needs to reduce stigma about services, as well as HIV and mental health. | Stigma should be addressed in the clinical encounter. | LMSM experience high HIV and mental health stigma, which interferes with use of services. | There is high stigma in Latino/a/x communities and countries of origin, and an overall legacy of HIV stigma. | ||

| Affirmation and Cultural Competence/Relevance | Dime Más needs to be culturally tailored and relevant; must tailor to LMSM’s needs and cultural barriers. | Need to have open, validating, sex-positive communication during the clinical encounter. | LMSM’s identity (e.g., cultural background, sexual orientation, outness, age) influences use and awareness of services. | Implementers need to be affirming and culturally competent (e.g., understand subcommunities of LMSM). | Organizations need to be LGBTQ-affirming and culturally competent. | Outreach efforts to LMSM need to be affirming, culturally relevant, and “on brand.” | |

| Language | Dime Más needs to be available in multiple languages (i.e., English, Spanish, Portuguese) to reach all LMSM; need to refer to other services available in multiple languages. | LMSM want to feel able to express themselves in whatever language they are most comfortable in. | Implementers should be competent delivering Dime Más and answering questions in English and Spanish. | Have a multilingual infrastructure within the organization (e.g., materials in Spanish, bilingual staff). | Different dialects of Spanish, colloquial terms in different countries, different concepts can be described in different languages. | ||

| Immigration | Dime Más needs to address immigration concerns (e.g., refer to organizations that offer services to immigrants, inform participants they can get services regardless of immigration status, tailor to immigrant LMSM, remind that it is safe to get services in terms of immigration status). | Specific emphasis should be placed on reiterating the safety of engaging in Dime Más, PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatment. | LMSM are concerned about their immigration status, impeding access and willingness to seek services. | LMSM immigrants have few legal protections. | |||

| Privacy and Confidentiality | Dime Más needs to be delivered with a focus on confidentiality, privacy. Should refer to organizations that provide confidential/private services. | Privacy protocols need to be communicated in the clinical encounter (including informed consent), not breached. | LMSM are worried about their privacy in the context of seeking services. | Organizations should establish confidentiality rules between staff. | |||

| Relationships and Networks | Relationships and Client-Centeredness | Dime Más needs to be driven by LMSM needs, have some flexibility, focused on relating to clients, have different ways of being delivered based on learning style (e.g., visual, auditory). | Need to establish rapport, mutual respect, meet clients where they are at with regard to their goals (e.g., not pushing PrEP), maintaining an ongoing relationship and following up to build rapport. | Implementers need to provide client-centered care, including empathy training, relationship building, support. | |||

| Latino MSM community | Dime Más should leverage peer influence/norms (e.g., ambassador stories to reach different groups, testimonials; encourage participants to share knowledge through personal networks). | Word of mouth from peers/family/friends may increase uptake; LMSM turn to peers to make decisions about getting services/products; LMSM not as well connected may not get the message though. | Implementer being LMSM may or may not help to normalize services and engage LSMM (must be invested in community if not members though). | Social media, media that the LMSM community consumes, and public LMSM spaces (e.g., pride, bars/clubs, etc.) can be used to broaden advertising and reach. | |||

| Networks and Communications | Dime Más needs to be developed in collaboration with community implementers. | LMSM’s trust of institutions that developed and are delivering Dime Más and clinical interventions impacts use. | Clinics in Miami are insufficiently networked, making cross-organization referral hard (e.g., clinics don’t know what other clinics offer); need to have collaboration with multiple organizations to reach LMSM via Dime Más implementation. | ||||

| Navigation of Health Information and Systems | Knowledge and Information | Dime Más needs to provide accurate and simple/clear information about sexual/behavioral health and services (e.g., explain how PrEP works and whether condoms are needed still; define behavioral health; information on all services available—PrEP, testing, BH; education on possible side effects of PrEP). | Balance out education (facts, information) with exploration of LMSM’s preferences, opinions, and feelings about services. | LMSM may not have knowledge/education about options for services, may have misinformation about resources (e.g., myths about PrEP). | (A) Outreach staff need knowledge about Dime Más and

available resources to implement it. Strategies could

include developing protocols for implementation, providing

training materials, conducting training and supervision,

maintaining ongoing communication with the study

team. (B) Outreach staff need to know basic information about HIV-prevention and behavioral health services in general and at their organization (not specific to Dime Más) and be able to communicate this to LSMM. |

Latino/a/x community overall does not have as much knowledge about HIV/behavioral health and available resources. | |

| Burdensomeness and Complexity | Dime Más and services need to be convenient, easy to access (e.g., rapid PrEP). LMSM need follow-up from provider to ensure they understood the information and obtained services. | After an initial clinical encounter, there needs to be follow-up to ensure the services were obtained despite any challenges. | Implementers need to implement programs that have some degree of flexibility and adaptability (e.g., not just for one population, not overly rigid protocol); providers are already highly burdened. | (A) Need to develop documentation systems and workflows to

help with the implementation of Dime Más and reduce

complexity/burdensomeness of adopting and maintaining this

new program (e.g., check-ins from research staff to ensure

implementation is running smoothly). (B) Dime Más needs to fit into the existing infrastructure of the organization/not be too burdensome to implement |

Healthcare systems are overall complex and hard to navigate; guidelines on who is “eligible” for services can prohibit access. | ||

| Resources and Models of Service Delivery | Available resources | LMSM often have limited time and availability to participate/get services; limited resources (e.g., no car, no smartphone). | Implementers need a tool for knowing what free or low-cost services other organizations provide. | Some organizations have unique resources that would be helpful for LMSM (e.g., Uber) whereas others are less resourced (e.g., smaller organizations). | Degree to which services in Miami are available at low to no cost; degree of external funding influences available resources. | ||

| Technology and Telehealth | Option should be available for Dime Más and clinical services to be delivered via remote models. | LMSM would like telehealth for a variety of reasons (e.g., protects privacy). | Organizations are adapting to telehealth due to COVID-19 | The overall healthcare system is adapting to telehealth due to COVID-19 | |||

| Motivation to Engage | Motivation and Self-Efficacy | Dime Más should involve activities to build motivation (e.g., goal setting). | Implementers need to feel motivated and efficacious to implement a program. | Leadership in an organization is motivated to implement a program. | |||

| Rewards and Reinforcement | Dime Más should involve the delivery of a reward for participation (e.g., financial, certificate of completion). | Implementers should receive recognition or reinforcement for being trained in/delivering Dime Más (e.g., a certificate). | Clinics would need financial support for adopting and implementing Dime Más at a clinic level. | ||||

| Trialability | Implementers would benefit from trying Dime Más themselves (e.g., role play) to enhance their skills. | Organizations need to be able to pilot the intervention and give feedback before full-scale implementation. | |||||

| Value Added | Perception that Dime Más will be acceptable and appropriate/meet the unique needs of LMSM compared to other programs. | Perception that Dime Más will have value added at the organizational level; will be a useful tool. | Perception that Dime Más complements other available resources in Miami; meets a need in the overall community. | ||||

Note. The content themes (displayed vertically) were derived via the general inductive approach, whereas the implementation domains were adopted from the Health Equity Implementation Framework. Cells within this matrix represent the intersection of content themes and Health Equity Implementation Framework domains and were the level at which coding was conducted. Blank cells refer to content themes that were not observed in a particular implementation domain.

Results

Participant demographics

LMSM ranged in age from 22 to 37. Most identified as gay (92%) and White Latino (92.3%). The majority were born outside the United States (i.e., Chile, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Nicaragua, Venezuela), and about half were US citizens.

Stakeholders ranged in age from 18 to 62, and most identified as Latino/a. Stakeholders included outreach workers, PrEP navigators, HIV test counselors, administrative assistants, managers, directors, and supervisors. Complete demographics are in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics.

| Demographic characteristic | Latino MSM (N = 13) | Stakeholders (N = 12) |

|---|---|---|

| Racea | ||

| White | 12 (92.3%) | 10 (83.3%) |

| Asian | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Black/African American | 0 (0%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Native American | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Decline to answer | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino/a/x | 13 (100.0%) | 9 (75.0%) |

| Haitian/Creole or Afro-Caribbean Black | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino or Haitian/Creole or Afro-Caribbean Black | 0 (0%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Gender identity | ||

| Male | 13 (100.0%) | 11 (91.7%) |

| Female | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Gay | 12 (92.3%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| Bisexual | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Heterosexual | 0 (0%) | 4 (25.0%) |

| Queer | 0 (0%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Not listed | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Education level | ||

| Some college | 5 (38.5%) | 5 (41.7%) |

| College/university | 8 (61.5%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| High school diploma | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Languages comfortable speakinga | ||

| English | 8 (61.5%) | 12 (100.0%) |

| Spanish | 11 (84.6%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time (More than 30 h) | 12 (92.3%) | |

| Looking for work | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Income (past month) | ||

| Less than $200 | 1 (7.7%) | |

| $200–$499 | 1(7.7%) | |

| $500–$999 | 1 (7.7%) | |

| $1000–$1999 | 2 (15.4%) | |

| $2000 or more | 8 (61.5%) | |

| Insurance status | ||

| ACA | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Medicaid only | 1 (7.7%) | |

| PVT/HMO from work/spouse | 5 (38.5%) | |

| Uninsured | 4 (30.8%) | |

| Nativity | ||

| US | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Chile | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Colombia | 4 (30.8%) | |

| Dominican Republic | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Mexico | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Nicaragua | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Venezuela | 2 (15.4%) | |

| US citizenship status | ||

| US citizen | 6 (46.2%) | |

| Permanent resident | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Awaiting residency | 2 (15.4%) | |

| Student visa | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Expired visa | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Temporary protected immigrant (DACA/dreamer) | 1 (7.7%) | |

| Role within organizationa | ||

| Outreach worker | 2 (16.7%) | |

| PrEP Navigator | 5 (41.7%) | |

| HIV test counselor | 6 (50.0%) | |

| Administrative Assistant | 1 (8.3%) | |

| Manager | 1 (8.3%) | |

| Director | 2 (16.7%) | |

| Supervisor | 3 (25.0%) | |

| Another role | 1 (8.3%) | |

| Years in role | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.58 (6.87) |

Note that total may add up to more than 100% because participants could check all that apply.

Qualitative findings

Here, we present our findings organized by higher order themes in which the relevant codes (in italics) and HEIF domains are described. Table 1 summarizes the codebook, and Table 3 provides quotations (numbered quotations can be matched to Table 3).

Table 3.

Example quotations illustrating content themes across implementation domains.

| Content theme | Code | Implementation domaina | Quotation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | |||

| Cultural Context | Stigma | X | X | Q1: I think specifically, especially in the Latino MSM community, there is a lot of stigma toward HIV, towards testing, toward PrEP. These are conversations that I have daily with different clients that I think, in order for us to make a dent and reduce, for example, Miami Dade and Broward County being number one and two for new HIV infections, I think that anything that we do to minimize stigma is a great first step. (Stakeholder, PrEP Navigator, HIV Test Counselor, & Supervisor) | ||||

| Affirmation and Cultural Competence/Relevance | X | Q2: I think these programs you’re carrying out, focused on the gay community, are super important and will benefit us in a great way, because we’re going to think, “you know, these people are just like me,” you know, “these are people who have the same fears, the same anxiety of knowing the information and I know that if I’m going to be asked, it’s not because I’m gay.” No, clearly we’re going to think, “you know, I accept myself for who I am and I’ll ask for information because I want to look after my health and protect those around me.” (LMSM, North American nativity outside the US, mid-30’s) | ||||||

| X | Q3: [The implementer of Dime Más should] have, maybe some background working with the community. I have experienced in the past that if I go to a regular doctor that is not part of a health center that works with the community, sometimes even when you talk about certain topics with them, they make faces or they take a moment and they're like, “Oh, you’re–” I don't know, talking about like anal sex. And for them it's kind of taboo, because it's just not part of their day-to-day language or it’s not something that they talk about every day. So, more than language and being comfortable with all the topics that we may want to talk with our doctor, providers, or the person who is taking my blood or whatever, they have to be just people who feel comfortable working with the LGBTQ + community. (LMSM, US nativity, late-30’s) | |||||||

| Language | X | X | Q4: I do believe language is important because it's a big barrier when it comes to getting the services. If I want to ask a million questions to my doctor, I want my doctor to fully understand what I'm asking and be able to explain in detail what I want to know about whatever question I may have. So, I think language is important, but not the sexual orientation or they don't have to be gay or part of the community, I feel it’s more like they have to feel comfortable with the language. (LMSM, US nativity, late-30’s) | |||||

| X | X | Q5: I need a Spanish-speaking navigator…Right now I’m the only one of the teams that speaks Spanish (Stakeholder, PrEP Services Coordinator) | ||||||

| Immigration | X | X | Q6: As someone in the Latino community, I understand the feeling of doubts, those who just arrived here, 2, 3, 4 years ago or those who just got here and jumped off the plane, are also full of doubts. For one, we’re facing a country that provides more freedom in comparison to the Latino countries we come from, so in my personal case, one gets here with certain repression, like, “I can’t open up, I can’t say I’m gay, and if I am, where could I get a test, and what should I do if I’ve had sex?” All in all, one gets here influenced by this taboo, not letting one ask the first friend you make here, “Hey, where can I get an HIV test?” So, I think this information is really important, and apparently, they’re putting it out there… I’ve even noticed PrEP billboards, I think divulging it is crucial so that all of those who are unaware of how this works—and as the other guys here just mentioned—and to know it has nothing to do with migration status, and that it doesn’t affect because I used to think it did. I used to think, “What if this affects my migration status? What are they going to say? That I’m dangerous for this country, that I’m misbehaving, they won’t want me here, they’ll kick me out of this country.” So, all of these doubts would lead me to not look into it. Once I attended an interview similar to this one, but in person, where they said, “No, that has nothing to do with it, it won’t affect the migration status or anything.” That’s when I said, “Alright, I’m in.” (LMSM, South American nativity, late-20’s) | |||||

| Privacy and Confidentiality | X | X | Q7: However, having the information [about where to get PrEP] and then being able to count the number of people who are up-to-date with that information or want to get tested or receive treatment, that is where the confidentiality comes in. Many of us are shy, we’re embarrassed… interacting with many people to come to a solution can overwhelm us…So, if a more confidential system were put in place, where people would have access to this, and keep their anonymity, so to speak, because it’s something we care about, it’s something that matters so, anything related to that can be scary… (LMSM, Central American nativity, early-30’s) | |||||

| Relationships and Networks | Relationships and Client-Centeredness | X | X | Q8: I think that whenever I have a client, specifically, I try to tell them, “I'm not a drug pusher, I'm not trying to get you to take anything that you don't find necessary for yourself. But why don't we sit down and review your sexual history and see if this is an option? My sole purpose is to provide you with tools that would assist you in protecting yourself.” It's not necessarily to just reinforce the idea of a pill is always going to be the answer. (Stakeholder, Outreach Worker, PrEP Navigator, & HIV Test Counselor) | ||||

| Latino MSM community | X | X | Q9: [Referring to peer ambassador idea] Especially with the Latino community, because we are very, like, “Oh, my friend told me that I can go to this place or my cousin or the friend of a friend is going to a place where he's getting access to PrEP, oh, he told me that I can go there and it’s safe and it’s good and it's easy and it’s fast, now I want to go there.” So, I know social media, it's important. I know media is important. But like when it comes to the Latinx community, we’re almost like the rumor starter, like someone told me that I can go there, so I will go there. And that's very important inside the community, and that is, for me, I believe is a very effective way to give the information. (LMSM, US nativity, late-30’s) | |||||

| X | Q10: I think that’s when it’s important for the workers to identify themselves with us, because if I’ve slept with 44, and someone comes and says, “I’ve slept with 33”, that’s going to sound normal in my head. But if you’re a hetero, for example, and you tell them that, what will they say? “Look at this fag, he slept with 50” and then they’ll go and laugh… that’s why in my opinion, workers who identify with us, perhaps not gay, but who are very committed to us, will keep these problems at bay, about what they said or what they didn’t say, because they won’t care, they’re just identified with us. (LMSM, South American nativity, late-20’s) | |||||||

| Networks and Communications | X | Q11: We have to know how to…that I can call upon my fellow partner agency, and let them know, “Listen, I have a patient that I've been working with. He's having a barrier with transportation and via Zoom. He has Metro PCS; he doesn't have a smartphone.” Whatever barrier he has. “Can you continue this client-centered conversation with them? Can you follow up on me that this client went to your visit?” We tend to want to keep patients and sometimes patients, they don't show up. They're no shows. We need to know how to work with agencies and collaborate and on behalf of clients. (Stakeholder, HIV Test Counselor) | ||||||

| Navigation of Health Information and Systems | Knowledge and Information | X | Q12: Having easier access to the information and explaining everything that happens in words that are easier to understand. When one starts reading the information, one will start getting confused with the scientific terminology, people who don’t have knowledge about that will get confused and disinterested. So, perhaps making it simpler, with everything included…negative side effects, positive effects, advantages and disadvantages in an easy-to-digest way. I think this way people would have an easier understanding of the information, especially for those who aren’t informed. (LMSM, South American nativity, early-30’s) | |||||

| X | Q13: [Describing the support they would need to implement Dime Más] Material that we can easily distribute to the clients. Maybe training sessions that we could provide our specific staff so that our staff knows what to talk about. Just talking points, material marketing, resources that we could use to maybe even connect some of our clients together. For example, if we have outreach or whatnot that we could do that's specific to the program. Things like that. (Stakeholder, Outreach Worker, PrEP Navigator, & HIV Test Counselor) | |||||||

| Burdensomeness and Complexity | X | Q14: Yes, I think it's specifically, one aspect that feels to me that is really going to drive the point home with the clients would be the following up. I feel after most interventions happen, it's very important to follow up with clients to make sure that they're reminded of what they say they're going to do or what services they're looking for. Because I do see a lot of falling off the use of services when you don't follow up with your clients…A week later, you just follow up through a text. I think is so far the best form to just keep something because most people don't just listen to a voicemail, or they ignore it. But if they see a text, it's something that they can read easily. I think that that's so far, the best form of following up with clients. (Stakeholder, Outreach Worker, PrEP Navigator, HIV Test Counselor, & Administrative Assistant) | ||||||

| X | Q15: So, for instance, you know [our current HIV-prevention program at our organization]. Well, we just created that and, in some ways, is nothing more than an articulation of what's already out there. It's just a toolbox of HIV-prevention strategies by having the logo and the music. There's actually music that is associated with it, and all these things people associated as being an intervention. But part of the reason why we went that way is because I realize it's so much less complex than Many Men Many Voices or Mpowerment or what the CDC wants now. (Stakeholder, Director) | |||||||

| X | X | Q16: Something that I've experienced with previous programs that we've tried implementing…It sometimes felt like we didn't get enough support. We didn't get enough material. We didn't get resources at our disposal to be able to facilitate what was being asked of us. It's a disappointing situation because it's like, the one that loses out really is the client, right? Because you have this opportunity to provide them something, but it's not being supported well enough. (Stakeholder, Outreach Worker, PrEP Navigator, & HIV Test Counselor) | ||||||

| Resources and Models of Service Delivery | Available resources | X | Q17: Talking about resources, I think it would be great if in designing that process, if we work on the interagency referral process that there's a part in which we can document resources that every organization has in a way to be able to refer to each other. For instance, at [our organization] we have an overhead program that is very heavily funded, meaning that any agency wants to refer someone to us, we can get that client picked up by an Uber at no cost to the client. We've had a lot of money put into that account. That's an example of a resource that we have that another agency may not have, and so on and so forth. Knowing what those resources are is one step, and being able to design the process so that we can take advantage and continuously do those resources to be able to refer to each other, I think has a lot of potential… (Stakeholder, Director) | |||||

| Technology and telehealth | X | Q18: Last year, with all the COVID situation, I started using Telle Doc that is an app that you can have a doctor appointment from home to your phone. And I feel like some, a service like that but when it comes to navigators, will be amazing. Maybe there is an app or a website where I can go and say, “Okay, this is what I need. And the navigator, through my phone can tell me, “Okay, these are the services available in your community, if you need these, you can go to this bar.” But not just giving me an address and giving me a phone number, it’s giving me, maybe helping me to make an appointment or helping me to engage with that organization that is going to help me with whatever issue I'm having. (LMSM, US nativity, late-30’s) | ||||||

| Motivation to Engage | Motivation and Self-Efficacy | X | Q19: Then when the worker is burnt out, he’s not going to work as well or motivated—or not motivated. Motivation, honestly, is garbage. The worker’s not going to do their job understanding the impact that that is going to have on that person. He’s going to do something like filling out the paperwork… (Stakeholder, Manager) | |||||

| Rewards and Reinforcement | X | Q20: If you put Dime Más under the name of UM [University of Miami] and give away specialized training with a special certificate for outreach workers or health workers, man, you’re going to get people. You’re going to get managers there (Stakeholder, Manager). | ||||||

| Trialability | X | Q21: One of the things that we usually—and has worked for us with new initiatives like that—is to establish a pilot at the beginning. The pilot can be something as simple as, for instance, we have counselors in different locations, in different offices, not going full scale yet because it's a new initiative. As much as we're going to think that we've got everything covered, that we've thought about everything, documenting at the beginning how people respond to it? What are the barriers? What is the feedback from staff? There's value in doing it, let's say at one location, or with a small group of staff and clients, or with all the staff, but with a few clients. Or all the staff at one location. Whatever we decide it may be, and document in that case with you, as a supervisor for [Dime Más]. Documenting the feedback, and from that step, seeing how to go to full implementation. That has worked for us. (Stakeholder, HIV Test Counselor) | ||||||

| Value Added | X | Q22: I think [Dime Más] will be great as an extra tool that we can use because it's good to always hear what other people are doing. Refresh your program. Maybe something that you're not doing and you can start doing. It's always good to have a refresh or a new idea, implement it. A way that maybe if you're having barriers, constant barriers with patients and you can implement, you can give us a tool that can better that barrier and reduce those barriers and help us fulfill our job duties in an easier way. And get our numbers every month, and have people coming in with less STI s and less infections, which is great. But we also can identify those people who are at high risk in a better way. I think for my agency…we will welcome you to give us more tools that we have already implemented, but we will definitely use your tools as well. (Stakeholder, HIV Test Counselor) | ||||||

Implementation domain that the quote refers to (Implementation domains: I = Innovation, II = Clinical Encounter, III = Patient, IV = Provider, V = Inner Context, VI = Outer Context).

Cultural context

Due to the HIV, mental health, and sexual orientation/behavior stigma that LMSM experience within their communities, they suggested that Dime Más have a component to reduce HIV and mental health stigma (Q1). They described the importance of the clinical encounter, in which Dime Más is delivered, to be nonstigmatizing (e.g., Dime Más implementer using nonstigmatizing language to talk about mental health). Given that LMSM’s intersecting identities could influence the use of services, participants felt Dime Más needed to be affirming and culturally competent/relevant, accomplished by culturally tailoring to LMSM (Q2). Participants viewed the name “Dime Más” favorably, based on their impression that it was relatable and affirming for LMSM across identities. They also described the need for Dime Más implementers, implementing organizations, and outreach efforts to be affirming and culturally competent (Q3).

Language and immigration were additional cultural context factors that were important to consider in developing and implementing Dime Más. Participants underscored the need for Dime Más to be available in multiple languages (i.e., English and Spanish, but Portuguese and Haitian Creole could further extend reach), Dime Más implementers being bilingual, and having PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health referrals to Spanish-speaking providers (Q4, Q5). Due to LMSM’s immigration fears and lack of legal protections (Q6), participants explained the importance of Dime Más being tailored to address these immigration concerns by referring to providers who specifically serve immigrant communities, ensuring LMSM know they can legally access these services regardless of their immigration status, and making clear that Dime Más is inclusive of immigrants.

Because of the context in which LMSM seek services—including stigma and immigration fears—participants discussed the importance of privacy and confidentiality when participating in Dime Más and accessing services. They described the importance of Dime Más being presented to LMSM as confidential and referring to organizations that prioritize confidentiality (Q7). They also described the importance of organizations that implement Dime Más and other healthcare services establishing confidentiality rules, as some participants described experiences when their information was shared unnecessarily between staff, resulting in mistrust.

Relationships and networks

Participants explained that relationships and client-centeredness and leveraging relationships within the Latino MSM community were key to developing and implementing Dime Más. They explained that Dime Más needs to be client-centered and flexibly delivered, such that implementers honor LMSM’s own goals and focus on building and maintaining rapport (Q8). Relationships within the LMSM community and peer influence could also facilitate the development and implementation of Dime Más. Participants explained that word of mouth is a powerful influencer on the uptake of services among LMSM and that LMSM turn to their peers to make decisions about healthcare services to use or avoid. Given this, participants were enthusiastic about having “peer ambassadors” within Dime Más who could influence LMSM’s PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatment uptake (Q9). They underscored the importance of peer ambassadors being relatable and reflecting the diversity of LMSM (e.g., language, race, employment status, sexual orientation, gender expression, nativity, citizenship). Although participants generally agreed peer ambassadors would be important as a component of Dime Más, they were mixed on whether Dime Más implementers needed to identify as LMSM and also in some cases expressed concerns about the feasibility of always having an LMSM implementer. There was, however, consensus that if an implementer was not LMSM, they needed to be trained to communicate affirmation and respect (Q10).

Two additional considerations related to networks and communications arose related to the continued development and implementation of Dime Más. First, participants indicated Dime Más would be well received due to its affiliation with an academic institution and because it was developed in partnership with community organizations. Second, participants (mostly stakeholders) described the need to bridge networks between HIV and behavioral health organizations in Miami to implement Dime Más. Stakeholders explained that their organization might not have the resources to meet every LMSM’s needs, therefore if they implemented Dime Más, they wanted to be networked with other HIV and behavioral health organizations to deliver HIV and behavioral health treatments to LMSM (Q11).

Navigation of health information and systems

Due to a lack of access to knowledge and information, participants felt that HIV-prevention and behavioral health services could be burdensome and complex for both LMSM and stakeholders to navigate. Given the lack of access to knowledge and information about PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatments, they felt Dime Más needed to provide clear and accurate information to fill knowledge gaps, address misinformation, and enhance LMSM’s ability to navigate the healthcare system (Q12). To enhance Dime Más implementers’ knowledge and ability to navigate LMSM through the healthcare systems via Dime Más, they needed workflows, materials for outreach and delivering Dime Más, interactive and engaging training, supervision, and ongoing support from the study team (Q13).

Given the burdensomeness and complexity of the healthcare system, participants described the need for Dime Más to be simple and easy to access for LMSM (e.g., accessible in multiple ways, not overly time-consuming), and for Dime Más to simplify the process of obtaining PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatments. For example, they felt that after the initial Dime Más session, implementers should follow up with LMSM to address barriers they encountered to getting services and reduce the complexity of navigating these challenges, with some likening this to case management (Q14). Burdensomeness and complexity were also a consideration for implementers and within organizations. Stakeholders made suggestions for reducing the complexity and burden of implementing Dime Más, including creating flexible protocols, ensuring Dime Más integrates with the existing infrastructure of the organization, and receiving support from the Dime Más developers when implementing (Q15, Q16).

Resources and models of service delivery

The resources available to LMSM, implementers, and organizations within the local community were a concern for the development and implementation of Dime Más. Given the lack of available resources some LMSM may have (e.g., phone, time, transportation, financial), participants underscored the need for Dime Más implementers to be able to refer LMSM to free services and other support services that can facilitate access (e.g., free transportation to their clinics; Q17). Organizations also needed the financial resources and support to implement Dime Más, with participants commenting on the variability in resources within different organizations and the influence of external funding (e.g., CDC funding priorities) on resources. One resource that participants felt particularly strongly about was technology and telehealth, which they felt were more available in the context of COVID-19 and could facilitate the implementation of Dime Más (Q18).

Motivation to engage

Motivation and self-efficacy were additional considerations in developing and implementing Dime Más. Participants recommended Dime Más include activities, such as goal setting, to increase LMSM’s motivation to obtain PrEP, HIV testing, and behavioral health treatments. Participants also described the importance of attending to Dime Más implementers’ motivation (Q19) and building implementation motivation among leadership (e.g., ensuring managers and supervisors are motivated to implement Dime Más and invest in staff training). One way of building motivation was to provide rewards and reinforcement for participating in and implementing Dime Más. For example, participants suggested providing training certificates for implementers and organizations (Q20). Another strategy for building motivation and self-efficacy would be to leverage trialability, including offering implementers firsthand experience with Dime Más as part of their training and piloting Dime Más before proceeding to full-scale implementation (Q21). The degree to which Dime Más would add value for consumers, organizations, and the overall community could also influence implementation motivation, with many noting that it would add value by enhancing the reach of needed services to LMSM (Q22).

Discussion

Our findings inform refinements to one multilevel implementation strategy to scale up and out HIV-prevention and behavioral health treatments to LMSM, while also highlighting themes potentially relevant to developing other implementation strategies for the same purpose and demonstrating a community-engaged approach to doing so. The applicability of our findings beyond refining Dime Más is underscored by the fact that the EHE plan calls for implementation research to enhance the reach of evidence-based tools such as PrEP and HIV treatment to populations most impacted by the HIV epidemic (Fauci et al., 2019). As such, our findings and overall approach could be utilized to inform implementation research efforts aligned with the EHE plan. Finally, this project illustrates one approach to designing for implementation; Dime Más is being developed to meet both consumer and implementer/organizational needs, which may prevent a “voltage drop” (Chambers et al., 2013) as Dime Más proceeds through the translational pathway.

Pinto and colleagues (2021) describe the need for dissemination and implementation research models to include constructs of community engagement, and the relative gap between the community engagement and the dissemination/implementation literatures. Although our findings inform refinements to the implementation strategy that we are currently developing and other potential implementation strategies to achieve similar goals, another contribution of this work is that it demonstrates a community-engaged approach to developing an implementation strategy. Specifically, we included both consumer and implementer perspectives to shape the development and implementation plan for Dime Más, reflecting the strategy of “communication” identified by Pinto and colleagues. We will further expand on this community engagement as we refine Dime Más, seeking ongoing feedback from our Community Advisory Board of LMSM and implementing partners, reflecting Pinto and colleagues’ strategies of partnership exchange, leadership, and collaboration.

Our findings support many elements of the initial version of Dime Más (Figure 1), while also informing refinements. For example, we originally planned to include a peer ambassador component of Dime Más based on our DÍMELO findings and others’ research suggesting the importance of peer influence among racially/ethnically diverse MSM (Mutchler et al., 2015; O’Donnell et al., 2002; Quinn & Voisin, 2020). The current study suggests the need to expand and formalize the peer ambassador component to a greater extent than planned, which may also help address the stigma frequently discussed in the current study.

Similarly, we planned to provide Dime Más implementers with a referral list to enable tailored referrals based on LMSM’s needs (e.g., clinics that would not identify them as MSM, could deliver PrEP remotely, had bilingual providers, offer free transportation). We learned through the current study that this component also needs to be more robust and tailored to the local LMSM community. We are now in the process of developing a navigation tool, tailored to the needs of LMSM and stakeholders, to ensure they can identify local resources aligned with their needs. Based on our findings, we anticipate including within this tool a “review” feature that allows LMSM to comment on the degree to which organizations met their needs (e.g., were affirming, culturally competent, helpful). This tool can be used independently or within Dime Más and similar implementation strategies.

Additional refinements to Dime Más are informed by the convergence of the “available resources” and “cultural context” themes we identified. For example, given that some LMSM had privacy concerns linked to stigma (also observed by Harkness et al., 2021b), as well as a potential lack of resources to access in-person services, combined with the increased availability and infrastructure for telehealth, we plan to offer Dime Más as both an in-person and remote service, depending on participant preference. This is consistent with other research suggesting remote service delivery can enhance reach for behavioral and sexual health services among certain sexual minority men (Rogers et al., 2020; John et al., 2017), whereas others may prefer in-person (Turner et al. 2019). Although these findings are specifically relevant to Dime Más, they can inform the development of other implementation strategies with similar goals.

The findings also informed key decisions for implementers. Although we originally planned only to have LMSM implementers, our findings suggest this may not always be feasible. This echoes findings of minor improvements in care outcomes or overall perception of care for patients who were administered care from providers of the same race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation (see Cabral & Smith, 2011; Maramba & Nagayama Hall, 2002; O’Shaughnessy & Speir, 2018; Shin et al., 2005). Our findings suggested it would be ideal for LMSM to be implementers; however, non-LMSM could implement Dime Más if they were LGBTQ-affirming and skilled in working with Latino clients. At least some implementers in each organization implementing Dime Más need to be Spanish-speaking to ensure reach to monolingual Spanish-speaking LMSM. A related concern is considering the resources available within an inner setting before implementing Dime Más, a well-documented implementation determinant (Damschroder et al., 2009). Stakeholders raised important points such as the extent to which they had Spanish-speaking staff who could serve as implementers, the time existing staff had to implement a more intensive program like Dime Más, and the constraints placed upon them given the need to deliver services for which they received higher rates of reimbursement. As such, an addition to the provider-level implementation strategy is building a formal “implementation readiness assessment” to be conducted during the “preparation phase” (Aarons et al., 2011) of implementing Dime Más. Relatedly, we plan to conduct a cost analysis of Dime Más within our future pilot trial to understand the resources needed for implementation.

Secondarily, we observed that themes identified in this study, including cultural context, relationships and networks, and navigation of health information and systems are linked and can be addressed simultaneously through Dime Más and related implementation strategies. For example, enhancing LMSM’s ability to navigate health information and systems and increasing their awareness of their peers’ use of services may address stigma and further facilitate access to affirming resources. This is consistent with findings that among LMSM, stigma is associated with lower PrEP use intentions, an effect that PrEP knowledge may protect against (Hernandez Altamirano et al., 2020).

Despite this study’s strengths, it had limitations. Although we had broad representation from LMSM born in several countries outside the United States and with different citizenship statuses, White Latino MSM were represented to a greater extent than any other group. Despite being reflective of the demographics of Miami (Miami-Dade Matters, 2021) and the limitations of assessing race among Latino/a/x people as we did in the current study (Allen et al., 2011), we are working to increase the representation of non-White LMSM and exploring other ways of assessing race among Latino participants. Additionally, data were largely collected through focus groups, which have limitations, including potentially limiting dissenting viewpoints. Finally, we note that the interview guide included some direct questions that were less open-ended than our prior formative work (Harkness et al., 2021a), which evaluated barriers and facilitators to PrEP, HIV testing and behavioral health treatment in a more open-ended manner. Based on feedback from experts in intervention development and implementation science on our team, we needed to ask direct questions about specific components of Dime Más, given our goal of refining it using community and stakeholder feedback before developing a prototype. However, we acknowledge that asking direct questions in a qualitative interview can be limiting.

We also note the strengths and future directions for this research. We used an innovative analytic approach, integrating domains from an established implementation framework with inductively identified themes. This approach builds on guidance from Woodward and colleagues (2019, 2021) for integrating health equity into implementation science research and could be used in other health equity implementation research. Given the “voltage drop” often seen along the translational pathway (Chambers et al., 2013), this research centers the perspectives of both consumers and implementers, providing insights into how to tailor the consumer-facing component to LMSM needs and facilitate the implementation of Dime Más. Finally, our process in developing and refining Dime Más and the training program is iterative and multiphased. Based on the current findings, we will develop a prototype of Dime Más and the training program and theater test it with LMSM and stakeholders; this will provide another opportunity for feedback and alignment with community needs, resources, and priorities. Finally, although the current study guided refinements to Dime Más and the corresponding training program, the identified themes are potentially applicable to other implementation strategies that seek to achieve similar goals.

In summary, the current study identified LMSM and stakeholder perspectives regarding a multilevel implementation strategy to scale up and out HIV-prevention and behavioral health treatments to LMSM. The findings reveal the need for program developers, evaluators, and implementers to consider the needs of LMSM and stakeholders while developing and refining the implementation strategy. The study also illustrates a novel qualitative data analysis approach that integrates an established implementation science framework and allows for the inductive identification of themes.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-irp-10.1177_26334895221096293 for Refining an implementation strategy to enhance the reach of HIV-prevention and behavioral health treatments to Latino men who have sex with men by Audrey Harkness, Elliott R. Weinstein, Alyssa Lozano, Daniel Mayo, Susanne Doblecki-Lewis, Carlos E. Rodríguez-Díaz, C. Hendricks Brown, Guillermo Prado and Steven A. Safren in Implementation Research and Practice

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Daniel Hernandez Altamirano, Jaislene Viñas, and Michaela Larson for their assistance with this project. The authors also thank every participant in the study.

Note that we use “men who have sex with men” (MSM), a behavioral term that includes gay, bisexual, and other sexual minority men.

Note that we are following guidance from del Río-González (2021) who recommends using “Latino/a/x” to refer to the overall community, whereas we use “Latino” when specifically referring to men.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Safren receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Guilford Publications, and Springer/Humana press for books on cognitive behavioral therapy. Dr. Harkness receives royalties from Oxford University Press for a book related to LGBTQ-affirmative mental health treatment.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by K23MD015690 (Harkness), as well as author time supported by K24DA040489 (Safren). Additional research support was provided by U54MD002266 (Behar-Zusman), P30MH116867 (Safren), and P30DA027828 (Brown). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iDs: Audrey Harkness https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2290-9904

Elliott R. Weinstein https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5085-7470

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Aarons G. A., Hurlburt M., Horwitz S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen V. C., Lachance C., Rios-Ellis B., Kaphingst K. A. (2011). Issues in the assessment of “race” among Latinos: Implications for research and policy. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 33(4), 411–424. 10.1177/0739986311422880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D., Gosling A., Weinman J., Marteau T. (1997). The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: An empirical study. Sociology, 31(3), 597–606. 10.1177/0038038597031003015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill A. J., Brady J. P., Rooney B. M., Rodriguez-Diaz C. E., Horvath K. J., Blumenthal J., Morris S., Moore D. J., Safren S. A. (2020). Syndemics and the PrEP cascade: Results from a sample of young Latino men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(1), 125–135. 10.1007/s10508-019-01470-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J., Cefalu M., Wong E. C., Burnam M. A., Hunter G. P., Florez K. R., Collins R. L. (2017). Racial/ethnic differences in perception of need for mental health treatment in a US national sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(8), 929–937. 10.1007/s00127-017-1400-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. H., Curran G., Palinkas L. A., Aarons G. A., Wells K. B., Jones L., Collins L. M., Duan N., Mittman B. S., Wallace A., Tabak R. G., Ducharme L., Chambers D. A., Neta G., Wiley T., Landsverk J., Cheung K., Cruden G. (2017). An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annual Review of Public Health, 38, 1–22. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns M. N., Ryan D. T., Garofalo R., Newcomb M. E., Mustanski B. (2015). Mental health disorders in young urban sexual minority men. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(1), 52–58. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral R. R., Smith T. B. (2011). Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 537–554. 10.1037/a0025266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2014–2018 (No. 25). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-25-1.pdf?deliveryName = FCP_2_USCDCNPIN_162-DM27706&deliveryName = USCDC_1046-DM27774

- Chambers D. A., Glasgow R. E., Stange K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8(1), 117. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook B. L., Zuvekas S. H., Carson N., Wayne G. F., Vesper A., McGuire T. G. (2014). Assessing racial/ethnic disparities in treatment across episodes of mental health care. Health Services Research, 49(1), 206–229. 10.1111/1475-6773.12095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Río-González A. M. (2021). To Latinx or not to Latinx: A question of gender inclusivity versus gender neutrality. American Journal of Public Health, 111(6), 1018–1021. 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauci A. S., Redfield R. R., Sigounas G., Weahkee M. D., Giroir B. P. (2019). Ending the HIV epidemic: A plan for the United States. JAMA, 321(9), 844–845. 10.1001/jama.2019.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner L. I., Giordano T. P., Marks G., Wilson T. E., Craw J. A., Drainoni M.-L., Keruly J. C., Rodriguez A. E., Malitz F., Moore R. D., Bradley-Springer L. A., Holman S., Rose C. E., Girde S., Sullivan M., Metsch L. R., Saag M., Mugavero M. J., & Retention in Care Study Group (2014). Enhanced personal contact with HIV patients improves retention in primary care: A randomized trial in 6 US HIV clinics. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 59(5), 725–734. 10.1093/cid/ciu357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G., Bunce A., Johnson L. (2016a). How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. 10.1177/1525822X05279903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness A., Lozano A., Bainter S., Mayo D., Rogers B. G., Prado G., Safren S. A. (Manuscript Under Review). Engaging Latino Sexual Minority Men in PrEP and Behavioral Health Care: Barriers, Facilitators, and Potential Implementation Strategies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Harkness A., Satyanarayana S., Mayo D., Smith-Alvarez R., Rogers B. G., Prado G., Safren S. A. (2021a). Scaling up and out HIV-prevention and behavioral health services to Latino sexual minority men in South Florida: Multilevel implementation barriers, facilitators, and strategies. AIDS Patient Care & STDs, 35(5), 167–179. 10.1089/apc.2021.0018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness A., Weinstein E. R., Atuluru P., Mayo D., Vidal R., Rodriguez-Diaz C. E., Safren S. A. (2021b). Latinx sexual minority men’s access to HIV and behavioral health services in south Florida during COVID-19: A qualitative study of barriers, facilitators, and innovations. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 31(1), 9–21. 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 707–730. 10.1037/a0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmler V. L., Kenney A. W., Langley S. D., Callahan C. M., Gubbins E. J., Holder S. (2020). Beyond a coefficient: An interactive process for achieving inter-rater consistency in qualitative coding. Qualitative Research, 22(2), 194–219. 10.1177/1468794120976072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]