Significance

We took advantage of a unique experiment, in which anonymous donors gave US$10,000 to each of 200 recipients in seven countries. By comparing cash recipients with a control group that did not receive money, this preregistered experiment provides causal evidence that cash transfers substantially increase happiness across a diverse global sample. These gains were greatest for recipients who had the least: Those in lower-income countries gained three times more happiness than those in higher-income countries. Our data provide the clearest evidence to date that private citizens can improve net global happiness through voluntary redistribution to those with less.

Keywords: happiness, wealth redistribution, inequality, cash transfers, well-being

Abstract

How much happiness could be gained if the world’s wealth were distributed more equally? Despite decades of research investigating the relationship between money and happiness, no experimental work has quantified this effect for people across the global economic spectrum. We estimated the total gain in happiness generated when a pair of high-net-worth donors redistributed US$2 million of their wealth in $10,000 cash transfers to 200 people. Our preregistered analyses offer causal evidence that cash transfers substantially increase happiness among economically diverse individuals around the world. Recipients in lower-income countries exhibited happiness gains three times larger than those in higher-income countries. Still, the cash provided detectable benefits for people with household incomes up to $123,000.

A core goal of economic systems is to improve human well-being by allocating scarce resources. Yet, the world’s richest 10% owns three-quarters of global wealth, while the poorest half owns only 2% (1). Prominent scholars across disciplines have argued that extreme income inequality may vastly undermine the potential happiness of the world’s population (2–4). How much happiness could be gained if the wealthy few redistributed money to a broader swath of the world’s population? To estimate this effect, we examined the total happiness gained when two high-net-worth donors redistributed 2 million US dollars ($2M) of their wealth to 200 individuals around the world.

A great deal of research suggests that individuals earning higher incomes are happier than those earning lower incomes (for a review, see ref. 5), with the strength of this relationship diminishing as income increases (6). Although a few studies have examined the effect of naturally occurring income shocks using longitudinal panel data (7–10), most scholarly work has relied on correlational analyses, which cannot isolate the causal impact of money on happiness. Indeed, people with higher incomes tend to have better health, education, and other advantages linked to greater happiness (11, 12), and being happy may even lead to greater wealth: Happier high-schoolers earn higher incomes a decade later (13).

In recent years, a separate line of research has emerged using randomized controlled trials to test the impact of cash transfers as a form of aid to ameliorate poverty in lower-income nations (see ref. 14 for a review). In this line of work, cash is provided directly to the poor in place of traditional forms of aid, like food or clothing. While these studies broadly support the finding that money provides happiness (15), they have focused on samples living in poverty in lower-income countries, so it is unclear whether the benefits of receiving cash extend beyond the world’s poorest individuals.

Would receiving an influx of cash substantially improve the happiness of individuals in higher-income nations? To address this pressing question, numerous pilot projects examining the effects of cash transfers have been launched in the United States, Canada, Finland, and other countries (see ref. 16 for a review). To the best of our knowledge, only two projects have been completed so far. In Finland, the government provided 560 Euros per month to 2,000 unemployed residents and reported that this program increased their happiness (17). In Canada, 50 homeless individuals received a one-time cash transfer of 7,500 Canadian dollars each, but did not exhibit substantial increases in happiness (18). Another prominent study is currently underway, providing $500 per month for 2 y to 125 low-income households in Stockton, CA. Preliminary results from the first year of the study point to improvements in positive mood (19). Given that these unpublished studies have examined relatively narrow samples, it remains an open question whether providing cash transfers could improve happiness among the broader population.

In this study, we took advantage of a unique experiment, in which two wealthy donors partnered with the organization TED to give away $2M to an economically diverse global sample. Three hundred participants were recruited from three lower-income countries and four higher-income countries and randomly assigned to receive a single cash transfer of $10,000 ($10k) (or not). We assessed participants’ happiness by measuring the three core components of subjective well-being (SWB): satisfaction with life, positive affect, and negative affect (see ref. 5 for an overview). Going beyond previous work, this study allows us to assess the causal impact of cash transfers on happiness across a large and economically diverse sample.

Preregistration

This study was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF) as part of a broader project that investigated a variety of distinct research questions (https://osf.io/f7y6c?view_only=21b6fd74ba75493eaccbe2f534ff82fa). The present paper addresses question 2 in the preregistration. We report all relevant conditions and measures here.

Results

Using Twitter, the TED organization invited adults from Brazil, Indonesia, Kenya, Australia, Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom to apply for a “Mystery Experiment” by completing an initial survey, which included measures of demographics and baseline SWB. Participants were required to be at least “somewhat” fluent in English, with an active Twitter account. They spanned a wide range of ages (M = 34.3, SD = 12.1 Range = 21 to 78) and incomes (Mean = $54,394, Median = $27,580, Min = $0, Max = $400k, SD = $71,650), but were well-educated, (82% had a bachelor’s degree or higher) and liberal-leaning (M = 35.4, SD = 17.9, on a scale from 0 = “left” to 100 = “right”). Participants who were randomly assigned to the cash condition (n = 200) received $10k, which they were instructed to spend within 3 mo as part of the broader project; participants in the control condition (n = 100) did not receive cash transfers. For 3 mo after the cash transfers, participants in both groups completed monthly surveys that included our preregistered measures of SWB. For exploratory purposes, participants also completed an additional survey 6 mo after the cash transfers were delivered.

Cash vs. Control.

As preregistered, we calculated 3-mo averages for participants’ life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect and used multilevel models to test whether changes in each outcome from baseline to the 3-mo mean differed for participants in the cash vs. control groups. We entered condition (0 = control, 1 = cash), time point (0 = baseline, 1 = 3-mo mean), and the Condition × Time Point interaction into models predicting each component of SWB. Time points (level 1) were nested within individuals (level 2), and we used restricted maximum-likelihood estimation with random intercepts that varied across individuals. Significant interactions showed that, compared to control participants, cash recipients became significantly more satisfied with life [b = 0.36, SE = 0.11, t(294.31) = 3.4, P < 0.001], and they experienced greater increases in positive affect [b = 0.29, SE = 0.07, t(294.96) = 4.09, P < 0.001] and larger decreases in negative affect [b = −0.28, SE = 0.08, t(294.87) = −3.70, P < 0.001] across the 3 mo after receiving the cash.* Follow-up analyses examining the slopes of each condition revealed significant increases in each outcome among cash recipients, but no change among control participants (Table 1). These results demonstrate that the cash produced significant benefits for recipients’ emotional experiences and life evaluations.

Table 1.

Simple slopes by condition for each outcome

| Baseline | 1–3 Month | b | df | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| Satisfaction with life | ||||||

| Control | 4.08 (1.41) | 4.18 (1.36) | 0.1 | 294 | 1.19 | 0.23 |

| Cash | 4.21 (1.31) | 4.68 (1.15) | 0.47 | 294 | 7.54 | <0.001 |

| Positive affect | ||||||

| Control | 3.48 (0.70) | 3.46 (0.69) | 0.03 | 294 | 0.49 | 0.63 |

| Cash | 3.59 (0.62) | 3.86 (0.59) | 0.27 | 295 | 6.38 | <0.001 |

| Negative affect | ||||||

| Control | 2.65 (0.73) | 2.73 (0.68) | 0.08 | 294 | 1.32 | 0.19 |

| Cash | 2.58 (0.63) | 2.37 (0.61) | −0.20 | 295 | −4.53 | <0.001 |

| SWB | ||||||

| Control | −0.24 (0.85) | −0.27 (0.86) | −0.03 | 294 | 0.40 | 0.69 |

| Cash | −0.12 (0.74) | 0.21 (0.72) | 0.33 | 295 | 7.40 | <0.001 |

Note: Satisfaction with life was measured on a seven-point scale, while positive affect and negative affect were measured on five-point scales; each of these measures was z-scored and combined to form an index of SWB.

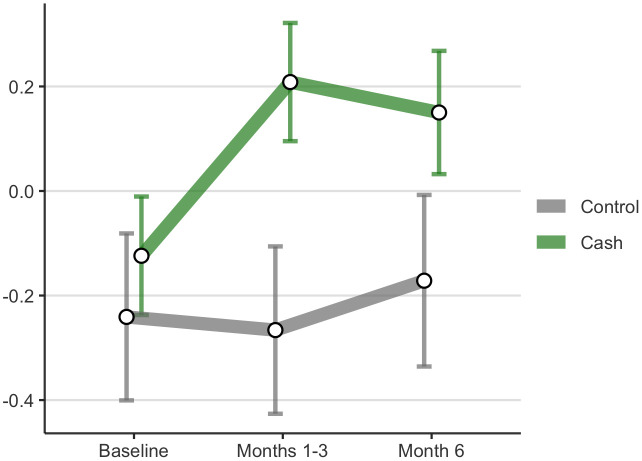

Exploratory analyses using a composite score for SWB (standardizing and combining satisfaction with life, positive affect, and reverse-scored negative affect) showed a similar interaction [b = 0.36, SE = 0.08, t(294.65) = 4.61, P < 0.001], with cash recipients experiencing greater increases in SWB across the 3 mo relative to controls. Another multilevel model comparing changes in SWB from baseline to each timepoint (1, 2, 3, and 6 mo posttransfer) revealed that this effect was consistent at the 1-mo (b = 0.32, P < 0.001), 2-mo (b = 0.36, P < 0.001), and 3-mo (b = 0.45, P < 0.001) time points. Recipients also maintained these gains at 6 mo (b = 0.20, P = 0.019), demonstrating that the cash had enduring benefits for well-being, even several months after the money had been spent (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

SWB over time for the cash and control groups.

Country Income and Household Income.

In additional exploratory analyses, we examined whether people in lower-income countries benefited more from cash transfers than those in higher-income countries. We entered condition (0 = control, 1 = cash), time point (0 = baseline, 1 = 3-mo mean), country income (0 = lower, 1 = higher), and their interaction terms into a multilevel model predicting SWB, clustered by country and individual. A significant three-way interaction indicated that cash recipients in lower-income countries exhibited significantly greater SWB improvements compared to recipients in higher-income countries [b = 0.35, SE = 0.15, t(292.45) = 2.30, P = 0.022]. That said, the improvement in SWB for cash recipients compared to control participants was significant within both lower-income countries [b = 0.54, SE = 0.12, t(141.25) = 4.42, P < 0.001] and higher-income countries [b = 0.19, SE = 0.09, t(151.28) = 1.97, P = 0.05].

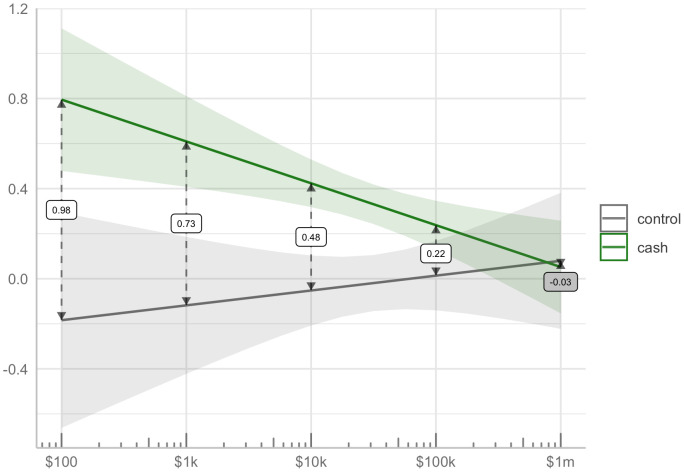

We then repeated these analyses, replacing country income with each participant’s household income (converted to US dollars, adjusted for purchasing power, and transformed to a log scale to account for skew). We found a significant Condition × Time Point × Income interaction [b = 0.11, SE = 0.05, t(288.4) = 2.22, P = 0.027]. To illustrate this effect, we simplified our model by removing time point as a factor and examining changes from baseline to the 3-mo mean as the outcome, which yielded an equivalent Condition × Income interaction [b = 0.11, SE = 0.05, t(288) = 2.23, P = 0.027].† As shown in Fig. 2, cash recipients with lower incomes exhibited greater improvements in SWB [b = −0.08, SE = 0.03, t(193) = −2.95, P = 0.004]; income in the control group was unrelated to improvements in SWB [b = 0.03, SE = 0.04, t(95) = 0.71, P = 0.48]. Our model predicts that participants with annual incomes of $10k would gain almost half of an SD of additional happiness as a result of receiving the cash transfer, and those making $100k would gain almost a quarter. Using an error-rate-adjusted Johnson–Neyman technique (20), we found that significant benefits were still detectable for those making as much as $123k [b = 0.20, SE = 0.10, t(288) = 1.96, P = 0.05].

Fig. 2.

Changes in SWB from before to after cash transfer predicted by log income.

Net Gain in Life Satisfaction.

By combining the present data with preexisting data on life satisfaction, we can roughly estimate how much more life satisfaction $2M provides when redistributed. Across the 3-mo study period, the total life satisfaction of cash recipients increased by 72 points (an average of 0.36 points for each of 200 recipients). Of course, giving up $2M may have decreased the life satisfaction of the two donors. As an approximate point of comparison, we utilized previous research documenting the relationship between net worth and life satisfaction across a large, diverse sample of millionaires (21). Estimates from these data suggest that each donor would have experienced a maximum decrease in life satisfaction of roughly −0.16 points as a result of a $2M decline in net worth (Methods). Thus, the total loss in happiness for the two donors is estimated to be −0.32 points. This suggests that redistributing wealth across our sample provided roughly 225 times more life satisfaction (72 points) than leaving it concentrated in the hands of two wealthy individuals (0.32 points). Of course, this estimate is speculative, given that spending $10k might yield only a temporary benefit for recipients, whereas the donors’ loss in net worth might continue to shape their happiness for many years. At the same time, the loss in net worth could plausibly be offset by the warm glow of giving money away (e.g., ref. 22), pointing to the possibility that donors and recipients are both left better off in terms of happiness.

Discussion

This study provides causal evidence that cash transfers substantially increase happiness across a diverse sample spanning the global socioeconomic spectrum. By redistributing their wealth, two donors generated substantial happiness gains for others. These gains were greatest for recipients who had the least: Those in lower-income countries gained three times more happiness than those in higher-income countries, and those making $10k a year gained twice as much happiness as those making $100k. Still, the cash provided detectable benefits for people with household incomes up to $123k. Given that 99% of individuals earn less than this amount (23), these findings suggest that cash transfers could benefit the vast majority of the world’s population.

Of course, some caution is necessary in interpreting these findings, given that the study did not include nationally representative samples and focused on a limited time period. Although all participants were English-speaking Twitter users who were relatively liberal-leaning and well-educated, this sample was more economically diverse than any previous cash-transfer studies, enabling us to estimate the happiness benefits across a wide range of incomes. That said, our finding that cash transfers improved SWB—but less so for people with higher incomes—is consistent with the law of diminishing marginal utility in economics (24) and with large-scale studies documenting the concave relationship between income and self-reported happiness (e.g., refs. 6 and 25–28).

In interpreting our results, it is also worth noting that participants were instructed to spend the money within 3 mo, which could have intensified the happiness benefits they experienced initially, while diminishing any long-term effects. People typically spend other common windfalls—such as tax refunds and stimulus checks—within a similar time frame (29, 30), however, and most of our participants reported purchasing durable goods and other assets that would have made a lasting impact on their net worth (e.g., cars or home renovations). It is also unlikely that the benefits we observed stemmed only from the thrill of spending, given that participants reported being happier 3 mo after the spending period ended. While the longer-term durability of these effects remains an open question, recent research examining lottery winners in Sweden points to the conclusion that a major windfall can lead to gains in life satisfaction that are detectable over a decade later (10).

It is also possible that receiving the surveys reminded cash recipients of their good fortune or that they intentionally inflated their happiness reports to avoid appearing ungrateful for the donors’ gift. While virtually all cash-transfer studies share this limitation, we attempted to minimize demand characteristics by utilizing dependent measures that asked people about their satisfaction with life in general and the frequency of positive and negative moods, rather than asking them how happy they were about receiving the money. Moreover, if people were motivated to appear grateful, it is unclear why high-income earners were immune from this tendency.

Leaving demand characteristics aside, presenting the cash transfer as a surprise gift from anonymous donors may have genuinely enhanced recipients’ happiness. Indeed, narratives around aid can impact recipients’ feelings and behaviors (31), so cash-transfer programs should be designed with careful attention to framing. The fact that the donors freely chose to give away $2M may also have enhanced the net happiness benefits for the donors themselves. Indeed, past research suggests that people experience a greater hedonic benefit from voluntary giving than from mandatory giving (32–34). This is important, given that many forms of wealth redistribution are enforced by governments, rather than freely chosen by individuals. Still, even when giving is mandatory, people may still experience pleasure from helping others (32). This pleasure may be amplified if cash-transfer programs are framed as an opportunity to reduce inequality, an approach that may be particularly valuable in cultural contexts where people are bothered by inequality (35).

Although large-scale wealth redistribution might be best achieved through government programs, our research demonstrates that private citizens can substantially improve others’ well-being directly through simple cash transfers. This approach is not limited to millionaires. Our data provide the clearest causal evidence to date that the happiness benefits of cash transfers are greatest at lower incomes, highlighting how individuals across the economic spectrum can improve net global happiness through voluntary redistribution to those with less. With 3.4 billion people living off $5.50 a day (36), those with more have a profound opportunity to improve the total happiness of humanity.

Methods

Participants.

Participants were recruited from three lower-income countries, Indonesia (n = 74), Kenya (n = 58), and Brazil (n = 13), as well as four higher-income countries, the United States (n = 83), the United Kingdom (n = 37), Canada (n = 18), and Australia (n = 17). These countries were included because they do not levy gift taxes, which allowed participants to receive the full transfer amount tax-free. As part of TED’s Mystery Experiment, half of the cash recipients were asked to tweet about their experience spending the money, so all participants were also required to have an active Twitter account; this manipulation was not relevant to the current research question and did not have any substantial impact on this study’s primary outcomes, so it is not discussed further. Individuals were also prevented from participating in the study if they were directly connected to members of the TED organization or if they reported that receiving $10k could cause them danger or distress.

Procedure.

Approximately 3 mo after completing the baseline survey, participants received an email that included detailed instructions about the study, tailored to their assigned condition. The email also included a video of Chris Anderson, the head of TED, introducing the project and—for cash recipients only—announcing the $10k gift (see OSF). Participants were required to pass a short quiz assessing their comprehension of the study details before providing consent to participate. Cash recipients received the money in a single payment via PayPal and were told that they could spend the money any way they wanted during the 3 mo, but were asked not to store the money for later use in a savings or investment account. Control participants did not receive a cash transfer, but received $25 for each survey they completed; they were informed that the study included other groups that might receive different amounts of money. Thirty-one control participants reported learning online that others had received cash transfers, but our preregistered analyses remained significant after excluding these participants.

Measures.

Each survey included well-validated measures to capture the three components of SWB. Measures of SWB continue to generate fruitful debate and rely on several key assumptions, including the assumption that there is a linear relationship between actual happiness and self-reported happiness (e.g., refs. 37 and 38). That said, self-report measures of SWB are widely used and have been shown to correspond well with peer reports (39) and to correlate sensibly with other constructs, such as health and social relationships (for reviews of these issues, see refs. 40–42). In the present research, participants reported their satisfaction with life by completing the five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (43); participants rated their agreement with statements such as “I am satisfied with my life” on a scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). Participants also reported their positive and negative affect by completing the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (44), which asks participants to indicate how frequently in the last month they experienced six positive feelings, such as “Happy,” and six negative feelings, such as “Sad,” on a scale from “very rarely or never” (1) to “very often or always” (5). The surveys also included a number of other psychological scales, as well as additional questions about how cash recipients spent the money, but these items are not relevant to the present preregistered research question; The full surveys are available on the OSF. The percentage of surveys completed was consistently high across all timepoints: 1 mo (99%), 2 mo (92%), 3 mo (91%), and 6 mo (86%). Because we pooled across months 1 to 3 in our primary analyses, we were able to include data for 98.4% of participants.

Estimating Life Satisfaction Among Millionaires.

We estimated the expected happiness loss of the donor couple using previous research, which has documented the relationship between net worth and life satisfaction across a diverse sample of more than 2,000 millionaires from 17 countries (21). The authors reported average life satisfaction of millionaires at four levels of wealth: 1.5M to 2.9M, 3M to 7.9M, 8M to14.9M, and 15M+. Individuals with 3M to 7.9M of wealth reported lower life satisfaction (M = 5.81) than those with 8M to 14.9M of wealth (M = 5.97). This decrease of 0.16 points was the largest drop in life satisfaction between any adjacent levels of wealth and, thus, represents the maximum loss in life satisfaction we would expect for each member of the donor couple. The accuracy of these estimates was verified with the author of the original paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Anderson, the TED organization, and the anonymous donors for making this project possible. We also thank Malanna Wheat and Sheila Orfano for managing the Mystery Experiment. We are grateful for constructive feedback on drafts of this work from John Helliwell, Chris Barrington-Leigh, Kristin Laurin, Matthew Lowe, Eric Werker, and Claudio Ferraz.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

*Although we had very little missing data, we repeated our primary preregistered analyses with imputed data for missing values, in line with our analysis plan. Doing so left our primary results substantively unchanged, with all Condition × Time point interactions remaining highly significant (P < 0.001).

†Here, we assume that the effect of condition depends linearly on log-income. To examine this assumption, we added log-income-squared and the interaction of condition and log-income-squared to this model; the fit was not significantly improved [F(2, 288) = 0.54, P = 0.58], suggesting that there was not a significant quadratic effect of log-income on change in SWB.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

To protect participant privacy, the data are not available publicly, but have been prepared to be shared confidentially with permission from the authors and the TED organization. The analysis code can be found at the OSF (https://osf.io/bhgnz/?view_only=e6bdb0f76cf847fc830c7e952287d8e6) (45). Our preregistration and study materials can be found online at the OSF (preregistration: https://osf.io/f7y6c?view_only=21b6fd74ba75493eaccbe2f534ff82fa; (46) and study materials: https://osf.io/h6q4a/?view_only=8482118091be4b0ea4774c13ad03387e) (47). The University of British Columbia research team maintains the cleaned datasets, so R.J.D. will serve as the primary point of contact for data requests. We will confirm permission from TED in response to all requests. Researchers can request data access by emailing R.J.D. at ryandwyer@psych.ubc.ca.

References

- 1.Chancel L., Piketty T., Saez E., Zucman G., World Inequality Report 2022 (2021). https://wir2022.wid.world/. Accessed 13 October 2022.

- 2.Powdthavee N., Burkhauser R. V., De Neve J. E., Top incomes and human well-being: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J. Econ. Psychol. 62, 246–257 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oishi S., Kesebir S., Diener E., Income inequality and happiness. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1095–1100 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sloman P., “How economic inequality might affect a society’s well-being” (video recording, PBS News Hour, 2019). https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-economic-inequality-might-affect-a-societys-well-being.

- 5.Diener E., Lucas R. E., Oishi S., Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra Psychol. 4, 15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevenson B., Wolfers J., Subjective well-being and income: Is there any evidence of satiation? Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 598–604 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuong N. V., Does money bring happiness? Evidence from an income shock for older people. Finance Res. Lett. 39, 101605 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frijters P., Haisken-DeNew J. P., Shields M. A., Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. Am. Econ. Rev. 94, 730–740 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner J., Oswald A. J., Money and mental wellbeing: A longitudinal study of medium-sized lottery wins. J. Health Econ. 26, 49–60 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindqvist E., Östling R., Cesarini D., Long-run effects of lottery wealth on psychological well-being. Rev. Econ. Stud. 87, 2703–2726 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirin R. S., Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 75, 417–453 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godøy A., Jacobs K., “The downstream benefits of higher incomes and wages” (Community Development Discussion Paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston, 2021-1; https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/community-development-discussion-paper/2021/the-downstream-benefits-of-higher-incomes-and-wages.aspx).

- 13.De Neve J. E., Oswald A. J., Estimating the influence of life satisfaction and positive affect on later income using sibling fixed effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 19953–19958 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bastagli F., et al. , “Cash transfers: What does the evidence say? A rigorous review of programme impact and of the role of design and implementation features” (Tech. Rep., ODI, London, 2016).

- 15.McGuire J., Kaiser C., Bach-Mortensen A. M., A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of cash transfers on subjective well-being and mental health in low- and middle-income countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 359–370 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dwyer R. J., Stewart K., Zhao J., “Cash transfer programs in the Global North and Global South” in Using Cash Transfers To Build An Inclusive Society: A Behaviourally Informed Approach, D. Soman, J. Zhao, S. Datta. Eds. (University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2022). Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kangas O., Flour S., Simanainen M., Ylikännö M., Evaluation of the Finnish Basic Income Experiment (The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Helsinki, 2020; julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/162219).

- 18.Dwyer R., Palepu A., Williams C., Zhao J., Unconditional cash transfers reduce homelessness. PsyArXiv [Preprint] (2022). https://psyarxiv.com/ukngr/ (Accessed 13 October 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.West S., Castro Baker A., Samra S., Coltrera E., “Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration preliminary analysis: SEED’s first year” (Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration, Stockton, CA 2021; https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6039d612b17d055cac14070f/t/603ef1194c474b329f33c329/1614737690661/SEED_Preliminary+Analysis-SEEDs+First+Year_Final+Report_Individual+Pages+-2.pdf).

- 20.Esarey J., Sumner J. L., Marginal effects in interaction models: Determining and controlling the false positive rate. Compar. Polit. Stud. 51, 1144–1176 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donnelly G. E., Zheng T., Haisley E., Norton M. I., The amount and source of millionaires’ wealth (moderately) predict their happiness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44, 684–699 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aknin L. B., Dunn E. W., Proulx J., Lok I., Norton M. I., Does spending money on others promote happiness?: A registered replication report. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 119, e15–e26 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giving What We Can, How Rich Am I? (2022) https://howrichami.givingwhatwecan.org/how-rich-am-i?income=85000&countryCode=USA&household%5Badults%5D=1&household%5Bchildren%5D=0. Accessed 13 October 2022.

- 24.Gossen H. H., The Laws of Human Relations and the Rules of Human Action Derived Therefrom (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1983). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jebb A. T., Tay L., Diener E., Oishi S., Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 33–38 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahneman D., Deaton A., High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 16489–16493 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Killingsworth M. A., Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2016976118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Layard R., Nickell S., Mayraz G., The marginal utility of income. J. Public Econ. 92, 1846–1857 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coibion O., Weber M., “How did U.S. consumers use their stimulus payments?” (NBER Working Paper 27693, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA 2020; https://www.nber.org/papers/w27693).

- 30.Vega N., Over a third of Americans plan to spend their tax refund right away, mostly to pay bills. CNBC (2022). https://www.cnbc.com/2022/04/02/most-americans-plan-to-spend-tax-refund-on-essentials.html. Accessed 13 October 2022.

- 31.Thomas C. C., Otis N. G., Abraham J. R., Markus H. R., Walton G. M., Toward a science of delivering aid with dignity: Experimental evidence and local forecasts from Kenya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 15546–15553(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harbaugh W. T., Mayr U., Burghart D. R., Neural responses to taxation and voluntary giving reveal motives for charitable donations. Science 316, 1622–1625 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aknin L. B., et al. , Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104, 635–652 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinstein N., DeHaan C. R., Ryan R. M., Attributing autonomous versus introjected motivation to helpers and the recipient experience: Effects on gratitude, attitudes, and well-being. Motiv. Emot. 34, 418–431 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alesina A., Di Tella R., MacCulloch R., Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? J. Public Econ. 88, 2009–2042 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Bank, “Poverty and shared prosperity 2018: Piecing together the poverty puzzle: Overview” (World Bank, Washington, DC, 2018; https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/poverty-and-shared-prosperity-2018#:~:text=andsharedprosperity).

- 37.Bond T. N., Lang K., The sad truth about happiness scales. J. Polit. Econ. 127, 1629–1640 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oswald A. J., On the curvature of the reporting function from objective reality to subjective feelings. Econ. Lett. 100, 369–372 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diener E., Suh E. M., Lucas R. E., Smith H. L., Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 125, 276–302 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diener E., Inglehart R., Tay L., Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 112, 497–527 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kahneman D., Krueger A. B., Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. J. Econ. Perspect. 20, 3–24 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oswald A. J., Wu S., Objective confirmation of subjective measures of human well-being: Evidence from the U.S.A. Science. 327, 576–579 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diener E., Emmons R. A., Larsen R. J., Griffin S., The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diener E., et al. , “New measures of well-being” in Assessing Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener, Diener E., Ed. (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2009), pp. 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anonymous Contributors. Wealth Redistribution. OSF HOME. https://osf.io/bhgnz/?view_only=e6bdb0f76cf847fc830c7e952287d8e6. Accessed 20 October 2022.

- 46.Anonymous Contributors. Preregistration Document. OSF REGISTRIES. https://osf.io/f7y6c?view_only=21b6fd74ba75493eaccbe2f534ff82fa. Accessed 20 October 2022.

- 47.Anonymous Contributors. Generosity and Spending. OSF HOME. https://osf.io/h6q4a/?view_only=8482118091be4b0ea4774c13ad03387e. Accessed 20 October 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

To protect participant privacy, the data are not available publicly, but have been prepared to be shared confidentially with permission from the authors and the TED organization. The analysis code can be found at the OSF (https://osf.io/bhgnz/?view_only=e6bdb0f76cf847fc830c7e952287d8e6) (45). Our preregistration and study materials can be found online at the OSF (preregistration: https://osf.io/f7y6c?view_only=21b6fd74ba75493eaccbe2f534ff82fa; (46) and study materials: https://osf.io/h6q4a/?view_only=8482118091be4b0ea4774c13ad03387e) (47). The University of British Columbia research team maintains the cleaned datasets, so R.J.D. will serve as the primary point of contact for data requests. We will confirm permission from TED in response to all requests. Researchers can request data access by emailing R.J.D. at ryandwyer@psych.ubc.ca.