Abstract

Trichomonas vaginalis infected with a double-stranded RNA virus undergoes phenotypic variation on the basis of surface versus cytoplasmic expression of the immunogenic protein P270. Examination of batch cultures by flow cytofluorometry with monoclonal antibody (MAb) to P270 yields both fluorescent and nonfluorescent trichomonads. Greater numbers and intensity of fluorescent organisms with surface P270 reactive with MAb were evident in parasites grown in medium depleted of iron. Placement of iron-limited organisms in medium supplemented with iron gave increased numbers of nonfluorescent trichomonads. Purified subpopulations of trichomonads with and without surface P270 obtained by fluorescence-activated cell sorting reverted to nonfluorescent and fluorescent phenotypes when placed in high- and low-iron media, respectively. No similar regulation by iron of P270 was evident among virus-negative T. vaginalis isolates or virus-negative progeny trichomonads derived from virus-infected isolates. Equal amounts of P270 were detectable by MAb on immunoblots of total proteins from identical numbers of parasites grown in low- and high-iron media. Finally, P270 was found to be highly phosphorylated in high-iron parasites. Iron, therefore, plays a role in modulating surface localization of P270 in virus-harboring parasites.

Trichomonosis (14, 17) is the most common nonviral sexually transmitted disease (vaginitis) and is caused by infection with the protist Trichomonas vaginalis (28). Trichomonosis has major health consequences for women, as it is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes (10), enhanced susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus (20, 27) and possibly cervical neoplasia (29).

Experiments aimed at understanding the reported extensive antigenic heterogeneity among T. vaginalis isolates (9, 13, 18, 24) led to the discovery of the property of phenotypic variation (6). This was defined on the basis of surface versus cytoplasmic expression of a repertoire of high-Mr immunogens (1, 2, 4, 5). The monoclonal antibody (MAb) C20A3 recognized an epitope tandemly repeated within the highly immunogenic surface protein termed P270 (6–8). Analyses by flow cytofluorometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of fresh clinical isolates revealed heterogeneous immunoreactivity, such as fluorescent and nonfluorescent subpopulations by indirect immunofluorescence with MAb (4, 6). These reactivities with MAb were similar to those reported for isolates with MAb, with polyclonal experimental sera, or with sera from patients with trichomonosis (8, 9, 13, 18, 24). Based on flow cytofluorometry with MAb, it became evident that two types of isolates occur naturally during infections with T. vaginalis (4). Type I isolates were homogeneous nonfluorescent (negative phenotype) trichomonads that synthesize and express P270 in the cytoplasm. In contrast, type II isolates were heterogeneous and comprised both fluorescent and nonfluorescent subpopulations (positive and negative phenotypes) that were then purified by FACS (6). Each purified subpopulation reverted to the opposite phenotype but only upon long-term daily passage in batch culture (6). It was further demonstrated that both MAb and polyclonal Ab from patients reactive with P270 were lytic for trichomonads with surface P270 in a complement-independent fashion (5, 11). In vivo, among type II isolates from patients, the percent of trichomonads with surface P270 ranged from 0 to ≤10% (4), suggesting that the host environment either eliminates parasites with surface P270 or favors cytoplasmic expression. Finally, the identification of the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus within T. vaginalis organisms established a relationship between virus infection and phenotypic variation (26). The virus is multisegmented (15), and loss of virus from parental type II isolate organisms by batch culture (16, 26) produced virus-negative progeny such as type I isolate parasites that were incapable of surface placement of P270.

The complete sequence of a p270 gene of a fresh clinical isolate was recently reported (23). Furthermore, it has been shown that, except for the number of tandemly repeated units (23), the gene was highly conserved among type I and type II isolates (3). The repeated domain was flanked by 69 bp (23 amino acids) of upstream and 1,185 bp (395 amino acids) of downstream nonrepeat, coding regions (23). The sequences of the repeats within the p270 gene were identical (23). Furthermore, recent analyses revealed that the amino- and carboxy-terminal, nonrepeated regions were identical for P270s of different isolates (4), showing that protein sequences were not responsible for surface versus nonsurface placement of P270 during phenotypic variation and among isolates.

A relationship was established between iron and levels of cytoadherence and amounts of adhesins synthesized by T. vaginalis (21). Insofar as the cytoadherent type II trichomonads synthesizing adhesins were known to lack surface P270 (6, 21), our group hypothesized that iron directly modulated surface placement of P270. In this report I show that growth in low-iron medium promotes surface placement of P270 for virus-infected but not virus-negative parasites. Conversely, growth of virus-positive organisms in high-iron medium, which induces expression of trichomonad adhesins (21), yields parasites without surface P270. It is also shown that high-iron trichomonads highly phosphorylate P270 compared to organisms grown in low-iron medium.

Relationship between iron levels in medium and P270 surface expression among type II isolate trichomonads.

Indirect immunofluorescence with live trichomonads was performed by using established conditions with the MAb C20A3. As seen for two representative experiments, whose results are given in Table 1, the type II clinical isolates T068-II, T066, and AL8 were heterogeneous for surface reactivity with MAb. The numbers of fluorescent trichomonads were always lower when parasites were grown overnight in the complex medium supplemented with iron. In medium depleted of iron, increased numbers of organisms with surface P270 were evident. This dramatic change in the percentage of the opposite phenotype in just three to four generations was unusual; earlier studies involving batch culture required weeks to produce a similar change in fluorescence patterns (6). Importantly, the dsRNA virus is lost among some isolates by daily passage in batch culture (6, 16, 26). An agar clone derived from a single parasite from the virus-positive parental organisms that lost the dsRNA virus (16) was also examined. These virus-negative AL8 progeny and the type I isolate T076 trichomonads were uniformly unreactive with MAb C20A3, as expected (16). As a control to affirm the absence of P270 from the surface of nonfluorescent organisms, a radioimmunoprecipitation (RIP) assay (6, 8) was performed by using MAb and detergent extracts of surface-iodinated type I isolate and virus-negative progeny trichomonads (AL8-N [Table 1]). Only type II isolate trichomonads had 125I-labeled P270 readily immunoprecipitated and detected in autoradiograms after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (6, 8, 19).

TABLE 1.

Relationship between iron and surface expression of P270 on T. vaginalis type I and type II isolatesa

| Isolate, isolate type, and level of iron in medium usedb | % of organisms with surface P270 in indicated exptc

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| T076, I | ||

| Low | 0 | 0 |

| High | 0 | 0 |

| T068-II, II | ||

| Low | 95 | 92 |

| High | 38 | 30 |

| T066, II | ||

| Low | 79 | 83 |

| Replete | 10 | 5 |

| AL8, II | ||

| Low | 89 | 76 |

| High | 20 | 32 |

| AL8-N, virus-negative from AL8d | ||

| Low | 0 | 0 |

| High | 0 | 0 |

Isolates were as defined on the basis of infection by the dsRNA virus (16, 26). Presence or absence of virus was determined using various criteria, as described recently (15). Briefly, dsRNA was detected in agarose gels after electrophoresis of total nucleic acids from T. vaginalis isolates and/or Northern analysis by using either the radiolabeled dsRNA segments or cDNAs corresponding to one of the dsRNA segments of the virus as probes (15).

The normal complex medium of Trypticase–yeast extract–maltose supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated horse serum was used for batch culture of trichomonads (12). Low- and high-iron media were prepared as described before (21), and parasites were grown under each condition for no less than 24 h prior to examination by indirect immunofluorescence. Briefly, low-iron medium was prepared by the addition of 2,2-dipyridal (Sigma Chemical Co., Saint Louis, Mo.) (0.15 mM final concentration) to growth medium. High-iron medium was made by the addition to growth medium of ferrous ammonium sulfate-hexahydrate (Sigma) (0.2 mM final concentration) from a 100-fold stock solution made in 50 mM sulfosalicylic acid.

As additional controls, the expression of unique proteins of T. vaginalis grown under low- versus high-iron medium was compared throughout to ensure the iron status of organisms, as has been repeatedly reported by our group (22). An irrelevant MAb of the same immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) isotype was always used as a negative control for all fluorescence and antibody-based assays. Although only representative experiments are presented here and elsewhere, these and all other experiments were performed no fewer than six times. In all cases, the same trends and relative proportions of reactivity with MAb C20A3 were seen, and differences in the percentages among samples of experiments performed identically never exceeded 5%, showing the reproducible iron modulation of P270 surface placement.

Modulation of P270 surface expression by iron.

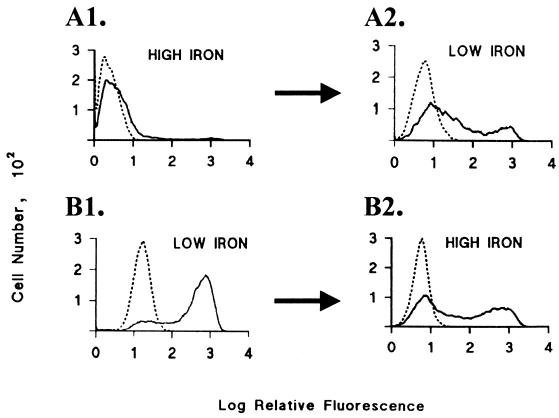

Both subpopulations reactive and unreactive with MAb were purified by FACS (6) of isolate T068-II. Figure 1 presents cytofluorometric patterns of purified subpopulations grown in high-iron medium (panel A1) and low-iron medium (panel B1) with C20A3 MAb (solid lines) and an irrelevant MAb (dotted lines) over a 24-h period (three to four generations). These same trichomonads were then washed and placed in different media and monitored throughout another 24-h period. As seen in Fig. 1A2 and B2, within 6 h, a time period shorter than that required for purified subpopulations in batch culture (12), increased numbers of organisms changed to the opposite phenotype. Importantly, other divalent cations were added to iron-depleted medium, as was done previously by this laboratory (21). No similar change from surface to cytoplasmic expression of P270 as seen in Fig. 1B1 was observed, even after batch cultures were maintained over a period of several days (data not shown). No fluorescence was detected with an irrelevant MAb.

FIG. 1.

Flow cytofluorometry monitoring surface expression of P270 of purified nonfluorescent (A1) and fluorescent (B1) subpopulations of T. vaginalis isolate T068-II grown in media with different levels of iron. FACS to enrich for each phenotype was performed on the heterogeneous trichomonads grown in either low- or high-iron medium, as shown in Table 1. Purified subpopulations were then grown in medium described in Table 1 either supplemented with (A1) or depleted of (B1) iron. Indirect immunofluorescence was performed on live trichomonads with MAb C20A3 that binds to the DREGRD epitope contained within each repeat of the tandemly repeated unit (11) prior to examination by flow cytofluorometry. Solid lines refer to the incubation of parasites with the MAb C20A3, and dotted lines represent the negative control with an irrelevant MAb of the same IgG2a isotype (6, 8). Duplicate cultures of trichomonads shown in panels A1 and B1, grown identically, were then washed and incubated in low-iron (A2) or high-iron (B2) medium for up to 24 h, followed by flow cytofluorometry. Briefly, for FACS, 2 × 106 organisms were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (1, 4–6) before being suspended in hybridoma supernatant containing C20A3 or irrelevant MAb. After incubation with MAb by using established protocols (4–6), FACS was performed on trichomonads by using a Becton Dickinson FACS-IV. Data are presented on the basis of log fluorescence intensity versus parasite number. In this case, the data reflect the use of 2 × 103 cells in the analysis. Similar results were obtained when up to 105 organisms were used, as before (4–6). Flow cytofluorometry as shown here was performed on at least three separate occasions, with similar results.

It has been established that iron induces synthesis of trichomonad adhesins and enhances levels of cytoadherence (21). As another control, comparative experiments monitoring the extent of cytoadherence in relation to expression of surface P270 were performed. As shown for two representative experiments (Table 2), T. vaginalis organisms grown in medium depleted of iron gave levels of cytoadherence lower than those seen for organisms grown in iron-replete medium. It was also noted that the overall extent and intensity of fluorescence was greater for the live parasites grown in low- versus high-iron medium. The established ligand assay was also performed to identify the four adhesins (21). Increased amounts of adhesins mediating cytoadherence were evident in high-iron organisms, and no synthesis was detectable in low-iron parasites. These results reaffirm the alternating expression of at least two groups of proteins on the surface of T. vaginalis (2).

TABLE 2.

Iron and the inverse relationship between adherence and surface expression of P270

| Expt and iron statusa | % Adherent trichomonadsb | % Fluorescent organismsc |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| High | 94 | 35 (low, 2+) |

| Low | 36 | 91 (high, 4+) |

| 2 | ||

| High | 83 | 25 (low, 2+) |

| Low | 46 | 80 (high, 4+) |

The iron status of organisms was determined by 24 h of incubation in either low- or high-iron medium, as has been described previously (21, 22).

The adherence assay employed HeLa cells in monolayer cultures on glass coverslips in 24-well plates incubated with 3[H]thymidine-labeled T. vaginalis organisms. After 30 min, coverslips were washed well in temperature-equilibrated phosphate-buffered saline, and the extent of binding was measured by scintillation spectroscopy. This assay was detailed in an earlier report (21). Percent refers to the total numbers of trichomonads bound to the confluent coverslips, based on the total number added and the specific activity of radiolabeled parasites (21).

Fluorescence for detection of P270 by indirect immunofluorescence was as described in the legend to Table 1. The low, 2+ rating refers to low strength of fluorescence among the positive trichomonads grown in high-iron medium and corresponds to a relative fluorescence between 1 and 2 in Fig. 1A1. In comparison, the high, 4+ rating refers to low-iron medium-grown parasites with an intense signal of fluorescence and corresponds to a relative fluorescence between 2 and 3 in Fig. 1B1.

Phosphorylation of P270 and cytoplasmic expression occurs in high iron.

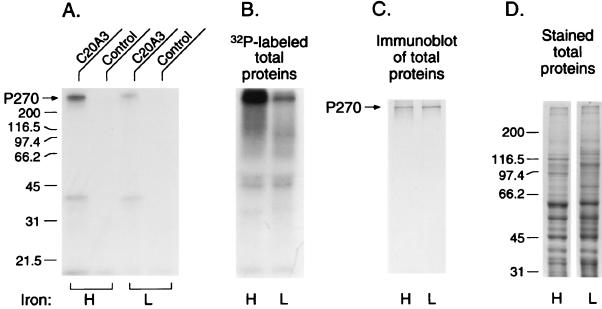

Figure 2A shows P270 bands from autoradiograms after SDS-PAGE (8, 19) of immunoprecipitated P270 from a RIP assay. Detergent extracts were prepared from 107 T. vaginalis T068-II organisms labeled overnight with 1 mCi of [32P]orthophosphate in 15 ml of high- versus low-iron medium. P270 is readily phosphorylated in parasites grown overnight in high- compared to low-iron medium. Similarly, greater intensities of phosphorylated proteins were seen in autoradiograms (Fig. 2B) of the total trichomonad protein gels (Fig. 2D) after SDS-PAGE. Gel lanes contained proteins from equal numbers of parasites. Interestingly, as seen in Fig. 2C, immunoblotting (8, 25) performed on duplicate gels such as those seen in Fig. 2D gave similar intensities of bands immunoreactive with MAb C20A3, indicating that iron levels did not affect the overall relative amounts of P270 within organisms. As a control, fluorograms of 35S[methionine]-labeled trichomonads grown in high- and low-iron media were examined. Similar overall protein patterns were seen, showing that the differences in phosphorylation were not due to toxic effects from the various levels of iron in the medium. As additional controls, duplicate samples handled identically, except that they were not radiolabeled, were monitored by flow cytofluorometry. Patterns of fluorescence for parasites grown in low- and high-iron media were similar to those in Fig. 1A1 and B1 and Table 1. Finally, under identical conditions, phosphorylation was never evident for the adhesins mediating cytoadherence, regardless of the level of iron in the medium (Table 2) (21), which served as an internal control during these assays.

FIG. 2.

Higher levels of phosphorylation of P270 in T. vaginalis organisms grown in high-iron (H) versus low-iron (L) medium. (A) Autoradiograms from RIP assay performed as detailed before (4, 6, 8) by using detergent extracts of [32P]orthophosphate-labeled trichomonads incubated with MAb C20A3 or irrelevant control MAb. Immune complexes were precipitated by using protein A-bearing Staphylococcus aureus (6, 8). All extracts contained N-α-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone to inhibit cysteine proteinases released upon solubilization of parasites. Immunoprecipitated 32P-labeled proteins were then solubilized by boiling S. aureus for 3 min. After bacteria were pelleted, the supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE, and gels were dried for autoradiography, as before (6, 8). (B) SDS-PAGE-autoradiography showing 32P-labeled protein bands of total proteins obtained from high- and low-iron parasites. Total proteins were precipitated by 10% trichloroacetic acid and processed as before prior to electrophoresis (8). (C) SDS-PAGE of total proteins as in panel B was then blotted onto nitrocellulose for probing with MAb C20A3 by using established protocols (8, 25). Control irrelevant MAbs of the same isotype were used as controls and did not give any reactivity with trichomonad proteins on the nitrocellulose blots. (D) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gels of total proteins after SDS-PAGE show the complex patterns for both high- and low-iron medium-grown trichomonads. Changes in patterns, as evidenced in the Mr region between size markers 97.4 (in kilodaltons) and 116.5, are representative of high- and low-iron parasites, respectively. These serve as internal controls to monitor the iron status of trichomonads.

Definitive evidence that iron directly modulates surface expression of P270 among virus-harboring T. vaginalis organisms was lacking in earlier data. This study establishes that iron mediates surface placement of P270 and, not unexpectedly, reaffirms that iron regulates the synthesis and surface expression of the adhesin proteins (21). Furthermore, the relationship between levels of iron in the growth medium and the phosphorylation of P270 is demonstrated (Fig. 2), which may begin to provide a biochemical basis to further elucidate the contribution of the dsRNA virus to the property of phenotypic variation.

The p270 gene of isolate T068-II was recently sequenced (23). This p270 gene has a 333-bp unit which contains the epitope recognized by the MAb, and this domain is tandemly repeated at least 18 times. The nonrepeat coding regions for the 5′ and 3′ ends were 69 nucleotides (23 amino acids) and 1,185 nucleotides (395 amino acids), respectively. More recently, it was learned that the 5′-end nonrepeat, coding regions among p270 genes of different isolates are identical (3). The 3′-end nonrepeat, coding regions among p270 genes were also highly conserved. Furthermore, the repeated element was identical among distinct repeats of the same gene as well as in the p270 genes of different isolates. Therefore, these and earlier results support the notion that phenotypic variation of P270 may be due to factors and variables other than the primary sequence of P270.

Interestingly, the phosphorylation patterns were compared between a representative virus-negative isolate with a high-Mr P270 similar to that of isolate T068-II (Table 1) (23). Results were similar to those shown in Fig. 2. These data may not be surprising, given the highly conserved nature of the p270 genes and proteins. The results also indicate that the phosphorylation machinery is present within trichomonads, regardless of viral infection. These data strongly suggest that the virus directly contributes regulatory factors that allow P270 to mobilize onto the surface of trichomonads.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to John Nguyen for assistance in the various assays and thank Jean Engbring for discussions.

This study was supported by Public Health Service grants AI-39803 and AI-43940 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderete J F. Trichomonas vaginalis phenotypic variation may be coordinated for a repertoire of trichomonad surface immunogens. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1957–1962. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.1957-1962.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderete J F. Alternating phenotypic expression of two classes of Trichomonas vaginalis surface markers. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(Suppl.):S408–S412. doi: 10.1093/cid/10.supplement_2.s408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alderete, J. F. The Trichomonas vaginalis phenotypically varying P270 immunogen is highly conserved except for numbers of repeated elements. Microb. Pathog., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Alderete J F, Demes P, Gombosova A, Valent M, Janoska A, Fabusova H, Kasmala L, Metcalfe E C. Phenotype and protein/epitope phenotypic variation among fresh isolates of Trichomonas vaginalis. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1037–1041. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.5.1037-1041.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alderete J F, Kasmala L. Monoclonal antibody to a major glycoprotein immunogen mediates differential complement-independent lysis of Trichomonas vaginalis. Infect Immun. 1986;53:697–699. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.697-699.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderete J F, Kasmala L, Metcalfe E C, Garza G E. Phenotypic variation and diversity among Trichomonas vaginalis and correlation of phenotype with contact-dependent host cell cytotoxicity. Infect Immun. 1986;53:285–293. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.2.285-293.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alderete J F, Neale K A. Relatedness of structures of a major immunogen in Trichomonas vaginalis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1849–1853. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1849-1853.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alderete J F, Suprun-Brown L, Kasmala L. Monoclonal antibody to a major surface immunogen differentiates isolates and subpopulations of Trichomonas vaginalis. Infect Immun. 1986;53:697–699. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.70-75.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alderete J F, Suprun-Brown L, Kasmala L, Smith J, Spence M. Heterogeneity of Trichomonas vaginalis and discrimination among trichomonal isolates and subpopulations with sera of patients and experimentally infected mice. Infect Immun. 1985;49:463–468. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.3.463-468.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotch M F, Pastorek II J G, Nugent R P, Hillier S L, Gibbs R S, Martin D H, Eschenbach D A, Edelman R, Carey J C, Regan J A, Krohn M A, Klebanoff M A, Rao A V, Rhoads G G. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. Sex Trans Dis. 1997;24:353–360. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dailey D C, Alderete J F. The phenotypically variable surface protein of Trichomonas vaginalis has a single, tandemly repeated immunodominant epitope. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2083–2088. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2083-2088.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diamond L S. The establishment of various trichomonads of animals and man in axenic cultures. J Parasitol. 1957;43:488–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honigberg B M. Trichomonads of importance in human medicine. In: Kreir J P, editor. Parasitic protozoa. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassai T, del Campillo M C, Euzeby J, Gaafar S, Hiepe T H, Himonas C A. Standardized nomenclature of animal parasitic diseases (SNOAPAD) Vet Parasitol. 1988;29:299–326. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(88)90148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khoshnan M A, Alderete J F. Multiple double-stranded RNA segments are associated with virus particles infecting Trichomonas vaginalis. J Virol. 1993;67:6950–6955. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.6950-6955.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khoshnan M A, Alderete J F. Trichomonas vaginalis with dsRNA virus has up-regulated levels of phenotypically variable immunogen mRNA. J Virol. 1994;68:4035–4038. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.4035-4038.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieger J N, Alderete J F. Trichomonas vaginalis and trichomoniasis. In: Holmes K K, Mårdh P-A, Sparling P F, et al., editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger J N, Holmes K K, Spence M R, Rein M F, McCormack W M, Tam M R. Geographic variation among isolates of Trichomonas vaginalis: demonstration of antigenic heterogeneity by using monoclonal antibodies and the indirect immunofluorescence technique. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:979–984. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.5.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laga M, Nzila N, Goeman J. The interrelationship of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection: implications for the control of both epidemics in Africa. AIDS. 1991;5:555–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehker M, Arroyo R, Alderete J F. The regulation by iron of the synthesis of adhesins and cytoadherence levels in the protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis. J Exp Med. 1991;174:311–318. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehker M, Alderete J F. Iron regulates growth of Trichomonas vaginalis and the expression of immunogenic proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:123–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musatovova O, Alderete J F. Molecular analysis of the gene encoding the immunodominant phenotypically varying P270 protein of Trichomonas vaginalis. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:223–239. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su-Lin K E, Honigberg B M. Antigenic analysis of Trichomonas vaginalis strains by quantitative fluorescent antibody methods. Zentbl Parasitenkd. 1983;69:161–181. doi: 10.1007/BF00926952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang C C, Wang A, Alderete J F. Trichomonas vaginalis phenotypic variation occurs only among trichomonads with double-stranded RNA virus. J Exp Med. 1987;166:142–150. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasserheit J N. Interrelationship between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. An overview of selected curable sexually transmitted diseases. WHO Global Programme on AIDS Report; 1995. p. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, Begg C B. Is Trichomonas vaginalis a cause of cervical neoplasia? Results from a combined analysis of 24 studies. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:682–690. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.4.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]