Abstract

Background

Acteoside, a water-soluble active constituent of diverse valuable medicinal vegetation, has shown strong anti-inflammatory property. However, studies on the anti-inflammatory property of acteoside in complement-induced acute lung injury (ALI) are limited. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the anti-inflammatory activity of acteoside in cobra venom factor (CVF)-stimulated human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC) and in ALI mice model.

Methods

In this study, we investigated the effects of acteoside (20, 10, and 5 μg/mL) in vitro in CVF induced HMECs and the activity of acteoside (100, 50, and 20 mg/kg/day bodyweight) in vivo in CVF induced ALI mice. Each eight male mice were orally administered acteoside or the positive drug PDTC (100 mg/kg/day) for 7 days before CVF (35 μg/kg) injection. After injection for 1 h, the pharmacological effects of acteoside were investigated by spectrophotometry, pathological examination, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and immunohistochemistry.

Results

In vitro, acteoside (20, 10, and 5 μg/mL) reduced the protein expression of adhesion molecules and pro-inflammatory cytokines and transcriptional activity of NF-κB (P < 0.01). In vivo studies showed that acteoside dose-dependently alleviated lung histopathologic lesion, inhibited the production of the protein content of BALF, leukocyte cell number, lung MPO activity, and expression levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and ICAM-1, and suppressed the C5b-9 deposition and NF-κB activation in CVF-induced acute lung inflammation in mice (P < 0.05, 0.01).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that acteoside exerts strong anti-inflammatory activities in the CVF-induced acute lung inflammation model and suggests that acteoside is a potential therapeutic agent for complement-related inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Complement, Inflammatory cytokines, Adhesion molecules, Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC)

Complement; Inflammatory cytokines; Adhesion molecules; Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB); Human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC).

1. Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a clinically acute respiratory disease with high mortality, which seriously threatens the survival and life quality of patients [1]. Despite the rapid development of critical care medicine, the treatment of ALI remains unknown. ALI is a respiratory disorder with acute inflammation characterized by the injury of pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells and pulmonary edema [2]. The pathogenesis of ALI is complex and diverse. It is accepted that high levels of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) are consistently associated with ALI similar to other respiratory syndromes such as sepsis or viral respiratory infections including SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, H5N1 influenza, and MERS-CoV [3, 4]. In addition, considerable evidence has demonstrated that the complement system which is an evolutionarily conserved component of innate immunity plays a crucial role in the pathophysiological processes of ALI for several decades [5]. Complement is a major component of innate immunity in host defense activated via three pathways, namely, the classical, alternative, and lectin pathways [6]. In general, the complement system is activated in response to foreign pathogens to perform its physiological function. However, excessive activation of complement could cause tissue/organ damage [7, 8], particularly the over-activation of the alternative pathway, which plays an important role in a series of disorders [9]. The activation of these three pathways requires engagement of the alternative pathway through “amplification loop” to induce tissue injury in vivo [9]. ALI is a disorder with disruption of the lung microvascular endothelium [2]. Endothelium damage increases capillary permeability and allows an influx of protein-rich fluid into the alveolar space [10]. It has been reported that intravascular systemic activation of complement can lead to ALI, with the main site of injury being vascular endothelial cells [6, 15]. The pathogenesis of this damage is related to stimulation of neutrophils, sequestration within capillaries of activated leukocytes promoting the release of several toxic meditators such as pro-inflammatory cytokines, and subsequent damage of microvasculature endothelial cells [11]. Therefore, exaggerated activation of complement is responsible for ALI and this injury is apparently related to damage of endothelial cells caused by the generation from neutrophils of toxic products.

Cobra venom factor (CVF), a specific complement alternative pathway activator, is a protein purified from cobra venom [12]. CVF can be used as an experimental tool to study the pathogenesis of diseases in laboratory animals. Several studies have shown that intravenous injection of CVF can trigger a systemic complement activation, resulting in acute inflammation response and changes in lung function and morphology, which are characterized by increased permeability between pulmonary capillary endothelial cells and alveolar epithelial cells, and the accumulation of a large amount of edema fluid in the alveolar space, which is rich in a variety of inflammatory cells dominated by neutrophils to increase ALI [13, 14, 15, 16]. Previously, we also have successfully constructed ALI mouse model using CVF as reflected by increases in inflammatory mediators in the lung and morphological evidence of lung damage [13]. Thus, the CVF-mediated ALI model could be used in exploring the pathological changes and effective medications of lung injury.

Acteoside, a water-soluble phenylethanol glycoside compound, is the major active component of many valuable medicinal plants such as Ligustrum purpurascens (kudingcha tea), Rehmannia glutinosa, Scrophularia ningpoensis, and Cistanche deserticola, which are widely used as traditional folk medicines in Asia [17, 18]. Some studies confirm that acteoside exhibits antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects [19]. Based on previous reports, acteoside can exert protective effects against ALI induced by lipopolysaccharide by regulating the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway and reducing the levels of pro-inflammatory mediators [1]. Complement has been involved in the various models of ALI [13]. However, the role of acteoside on complement-related ALI has not been reported. It is unknown whether acteoside is also effective in ALI induced by complement activation and how acteoside may function to protect this delicate tissue. Therefore, this study aims to characterize the therapeutic effects of acteoside in a CVF-induced model of acute lung inflammation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

CVF was self-prepared by our laboratory group as described previously [20]. In brief, the crude venom of Naja atra was isolated by sequential column chromatography (SP Sephadex C-25, Q Sepharose HP, and Sephacryl S-200). The purified CVF was homogeneous under nonreducing SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The purified CVF was separated in aliquots and stored at -80 °C until use. Pyrrolidinedithiocarbamic acid (PDTC) was obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Cat. No. S1809, Shanghai, China). Acteoside was obtained from Chengdu Alpha Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Cat. No. AF8060401, Chengdu, China).

2.2. Cell culture and treatments

Immortalized human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC) were presented by Dr. Jin Yang, who worked in Kunming Institute of Zoology in Chinese Academy of Sciences (Kunming, China) [21]. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 100% humidity. Cells were placed into 96-well plates (Corning) at 1 × 105 cells per well overnight. When grown to 70%–80% density, the cells were washed three times with Ca2+ and Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) and then supplemented with 90 μL of RPMI 1640 medium and pre-incubated with 10 μL of different concentrations of acteoside or warm PBS for 2 h; 30 μL of cell supernatants was then removed, and 30 μL of CVF-activated complement (CAC) products was added. The incubation products of CVF and inactivated normal human serum (INHS) were set as the control group. The final concentration of acteoside was adjusted to 20, 10, and 5 μg/mL based on the pre-experiment cytotoxicity test. After 6 h of incubation with CAC [23], culture supernatants and cell lysates were collected for biochemical assay of intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1, Cat. No. EK0370), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1, Cat. No. EK0537), and E-selectin (Cat. No. EK0501) using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer's recommendation.

In measuring interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) concentrations, the washed cells maintained in 180 μL of RPMI 1640 medium were pre-treated with 20 μL of different concentrations of acteoside. After pre-incubation for 2 h, 30 μL of CAC stimulation was added and incubated for 48 h. After incubation with CAC for 48 h [22], the levels of IL-6 (Cat. No. EK0410) and TNF-α (Cat. No. EK0525) in the medium were measured using ELISA kits.

2.3. Preparation of complement alternative activation products

CVF (6.5 × 104 U/L) was mixed with NHS in a 1:1 ratio and incubated in a 37 °C water bath for 30 min to prepare CAC products. The solution was prepared before cell treatment. The mixed incubates of CVF and INHS (incubated for 30 min at 56 °C) were set as the negative control.

2.4. Effects of acteoside on the transcriptional activity of NF-κB after exposure of HMEC to CAC

2.4.1. Plasmid preparation

Fifty microliters of DH5α (Cat. No. CW0808, CoWin Biosciences, Beijing, China) was added with 1 ng of NF-κB plasmid (Cat. No. N1111, Promega, USA) and internal reference recombinant plasmid. The tubes were placed on an ice water bath for 30 min and immediately transferred to a hot water bath (42 °C) for 90 s. Afterward, the tubes were placed on the ice water bath for 3 min. Then, 950 μL of Luria-Bertani (LB) broth without ampicillin was added and mixed by shaking gently for 1 h. The mixture was centrifuged immediately at 2000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed from the tubes; the bacterial pellet was resuspended in 0.35 mL of freshly prepared LB broth and placed on plates overnight at 37 °C in an incubator. Individual colonies of the transformed Escherichia coli strain were selected, and 3 mL of LB broth supplemented with 25 mg/mL of ampicillin was inoculated for amplification. The expression of the NF-κB plasmid and internal reference recombinant plasmid was extracted using the plasmid extraction kit (Cat. No. D0029, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. The concentration was detected by Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, USA).

2.4.2. Relative transcriptional activity of NF-κB by dual-luciferase reporter assay

Cells were seeded into black 96-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells per well for overnight growth. Cells were then washed three times with warm serum-free RPMI 1640 medium and then supplemented with 90 μL of RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and transfected according to the instructions of the Liposome Transfection Kit (Cat. No. C0526, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Ten microliters of the transfection mixture containing 88 ng of NF-κB expression plasmid, 45 ng of internal reference plasmid, and 0.2 μL of liposome reagent was added to each well for 16 h. Then, the supernatant was removed, 90 μL of RPMI 1640 medium and 10 μL of different concentrations of acteoside or warm PBS was added for 2 h. Thirty microliters of cell supernatants was removed, and 30 μL of CAC stimulation was added for 4 h [22]. The mixed incubates of CVF and INHS were set as the negative control. Fluorescence intensity was detected by the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Cat. No. E1910, Promega, USA), and the relative nuclear transcription activity (Ra) was calculated according to the following formula:

| Ra = (R1treat/R2 treat) / (R1control/R2 control) × 100 |

where R1 is the value of Firefly luciferase, and R2 is the value of Renilla luciferase.

2.5. Animals

Four-week-old Kunming male mice were obtained from the Animal Resources Center of Third Military Medical University (Chongqing, China). Filter top cages were used with four mice in each cage and kept in a barrier animal facility with a climate-controlled environment with 12 h light/dark cycles. All mice were fed chow provided by the Guizhou Laboratory Animal Engineering Technology Center (Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang, China).

2.6. Induction of ALI in mice and treatment protocol

Forty-eight mice were randomly divided into six groups (n = 8 per group): the control group (Control), CVF group (CVF), acteoside 100 mg/kg + CVF group (acteoside 100 mg/kg), acteoside 50 mg/kg + CVF group (acteoside 50 mg/kg), acteoside 20 mg/kg + CVF group (acteoside 20 mg/kg), and PDTC 100 mg/kg + CVF group (PDTC, as a positive control). The mice were subjected to a tail vein injection of CVF (35 μg/kg body weight, dissolved in sterile PBS with PH 7.4) to specifically activate the complement alternative pathway [13, 23] and establish the ALI model in mice. The control mice were injected with sterile PBS. Before inducing the model, the animals were orally pretreated with acteoside prepared in 0.2% carboxymethylcellulose sodium (CMC-Na, Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Corp., Shanghai, China) for 7 days. The vehicle-treated control group received equal volume of 0.2% CMC-Na. On the seventh day, mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg) 1 h after CVF or PBS challenge. The serum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), and lung tissues in each group were collected for analysis as described previously [13].

2.7. Inflammatory cell counting and protein concentration determination in BALF

The BALF was centrifuged at 2000 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min to pellet the cells. The BALF supernatant was thoroughly mixed, and the total protein concentration was tested using the BCA assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).The cell pellets were resuspended in ice-cold PBS. After excluding the dead cells by trypan blue staining, the total number of inflammatory cells in BALF was determined using a hemocytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

2.8. MPO assay and ELISA of BALF and serum

The superior and middle lobes of the right lung were collected and homogenized for the detection of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (an indicator of neutrophil accumulation) [24, 31] following a test kit protocol (Cat. No. A044-1-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). Cytokines in BALF and serum were determined with mouse ELISA kits (Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) for IL-6 (Cat. No. EK0411), TNF-α (Cat. No. EK0527), and ICAM-1 (Cat. No. EK0371).

2.9. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

The lower lobe of the right lung was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, and embedded for histopathologic detection with hematoxylin-eosin staining and the protein examination of C5b-9 and phosphorylated NF-κB p65 with immunohistochemical method. The lung injury score was performed as reported previously [13, 25]. The primary mouse monoclonal C5b-9 (dilution 1:200; Cat. No. sc-66190, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Paso Robles, CA, USA) and phospho–NF–κB p65 antibodies (dilution 1:500; Cat. No. sc-135769, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used to assess the protein expression of C5b-9 and phosphorylated NF-κB p65 in the lung tissue. The phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 was measured semi quantitatively by detecting the total positive area under the microscope with Image-Pro plus image analysis software. The C5b-9 deposition score range was 0–4 points: 0 represented no staining, and 1, 2, 3, and 4 denoted low, moderate, high, and very high staining, respectively.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences between groups were evaluated by analyses of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by the LSD's test as post-hoc comparison of means in SPSS 18.0. Statistical differences were considered to be significant at P < 0.05. The graphing were performed using the GraphPad Prism 8 Software (San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

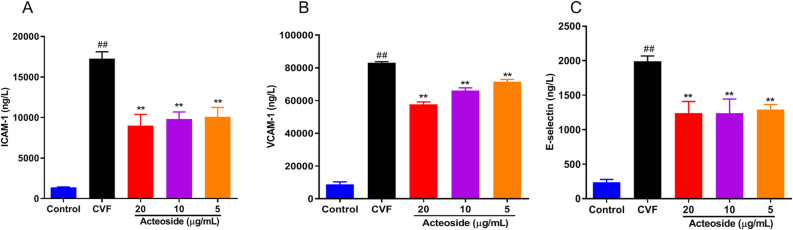

3.1. Acteoside reduces the release of adhesion molecules in HMEC induced by CAC

Endothelial cells that undergo stimulation with complement are characterized by the elevated expression of intercellular adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin [26, 27, 28]. Our previous studies showed that the peak concentrations of the above adhesion molecules in the cell supernatant occurred at 6 h after HMEC incubated with CAC [23, 30]. Thus we pretreated HMEC with various concentrations of acteoside for 2 h and then stimulated cells with CAC for 6 h to evaluate the potential anti-inflammatory effects of acteoside on ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin production in CAC-stimulated HMEC. As shown in Figures 1A-C, CAC-induced release of adhesion molecule markedly increased (P < 0.01). Acteoside could significantly decrease CAC-induced production of ICAM-1 (Figure 1A), VCAM-1 (Figure 1B), and E-selectin (Figure 1C) in HMEC in a concentration-dependent manner (P < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Effects of different concentrations of acteoside on the adhesion molecule expression of HMEC induced by CAC. HMEC were pre-treated with different concentrations (20, 10, and 5 μg/mL) of acteoside for 2 h and then incubated with 30 μL of cobra venom factor (CVF)-activated complement (CAC) products for 6 h. The levels of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (A, ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (B, VCAM-1), and E-selectin (C) in the medium were determined by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Values represented the means ± SEM (n = 3). #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 were compared with the control group; ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 were compared with the CVF group.

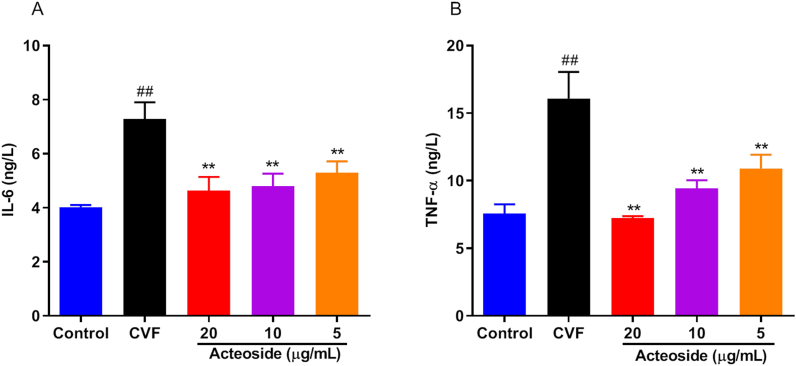

3.2. Acteoside inhibits the inflammatory mediator expressions of HMEC induced by CAC

The increased expression of adhesion molecules can promote the adherence of the inflammatory cells such as IL-6 and TNF-α, which are the main components of inflammation. Our previous studies showed that the peak concentrations of the inflammatory cytokines in the cell supernatant occurred at 48 h after HMEC incubated with CAC [22, 29]. Therefore, we tested the inhibitory effects of acteoside on the protein expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in CAC-induced HMEC for 48 h by ELISA. As shown in Figures 2A and B, the incubation of CAC-induced HMEC statistically and significantly increased IL-6 and TNF-α release. Acteoside downregulated the levels of IL-6 (Figure 2A) and TNF-α (Figure 2B) in HMEC in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.01), which showed a trend similar to the release of adhesive molecules. These data indicated the effect of acteoside on reducing inflammatory response in endothelial cell.

Figure 2.

Effects of different concentrations of acteoside on the inflammatory mediator expression of HMEC induced by CAC. HMEC were pre-treated with different concentrations (20, 10 and 5 μg/mL) of acteoside for 2 h and then incubated with 30 μL of cobra venom factor (CVF)-activated complement (CAC) products for 48 h. Interleukin-6 (A, IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (B, TNF-α) in the medium were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Values represented the means ± SEM (n = 3). #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 were compared with the control group; ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 were compared with the CVF group.

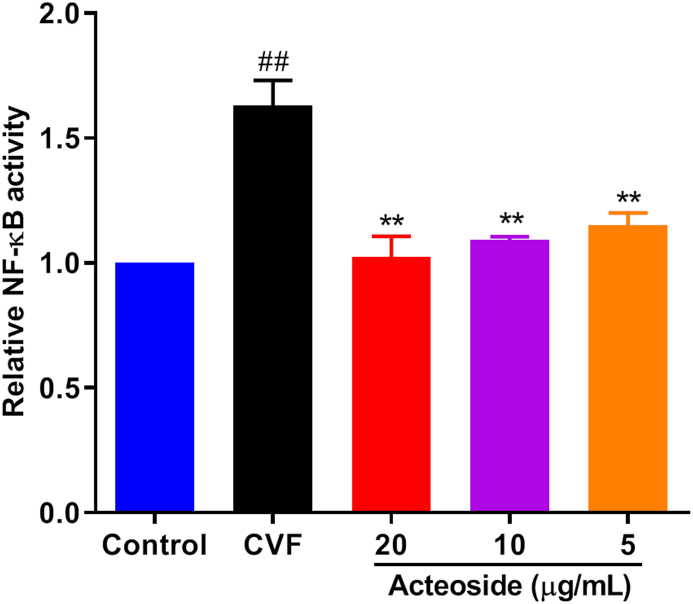

3.3. Effects of acteoside on the transcriptional activity of NF-κB after exposure of HMEC to CAC

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) serves as a transcriptional factor to regulate pro-inflammatory mediators in activated endothelial cell and plays a pivotal role in inflammatory diseases [30]. Therefore, HMEC were incubated with CAC for 4 h to investigate the mechanism of impaired lung-protective ability by acteoside, and the transcriptional activity of NF-κB was detected by Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay. As shown in Figure 3, pretreatment with different concentrations of acteoside resulted in a significant (≥29.5%) decrease in NF-κB translocation compared with PBS-pretreated HMEC (P < 0.01), which indicated that the transcription of NF-κB was inhibited by acteoside in the stimulated endothelial cells.

Figure 3.

Effects of different concentrations of acteoside on the transcriptional activity of NF-κB after exposure of HMEC to CAC. HMEC were plated in 96-well plates overnight and then transfected with the NF-κB expression plasmid and liposome reagent. Then, the cells were pre-treated with different concentrations (20, 10, and 5 μg/mL) of acteoside for 2 h and incubated with 30 μL of cobra venom factor (CVF)-activated complement (CAC) products for 4 h. The luciferase activity was measured by the dual-luciferase reporter assay system. Values represented the means ± SEM (n = 3). #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 were compared with the control group; ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 were compared with the CVF group.

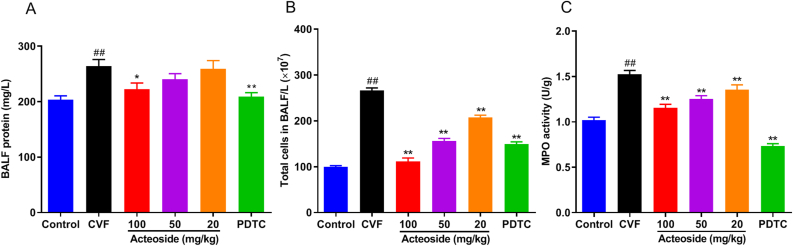

3.4. Acteoside decreases CVF-induced protein level increase, inflammatory cell extravasation in BALF, and pulmonary MPO activity

Given that acteoside exerted anti-inflammatory activities in microvascular endothelial cells, studies were extended to determine whether acteoside could affect CVF-induced inflammation in animal model of ALI. The BALF protein concentration is a commonly used indicator of pulmonary vascular permeability, which is an important characteristic of ALI. As shown in Figure 4A, CVF-challenged mice showed a significant increase of 22.9% in the BALF protein concentration when compared with CVF-challenged mice, and the level was significantly (P < 0.05, 0.01) decreased by acteoside pretreatment at a concentration of 100 mg/kg (15.7% reduction) and PDTC (20.9% reduction). No significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed in mice pretreated with 50 and 20 mg/kg of acteoside compared with CVF-challenged mice (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Acteoside suppresses the protein concentration and cell counts in BALF and inhibits neutrophil infiltration in lung tissues. Mice were orally pretreated with different concentrations (100, 50, and 20 mg/kg/day) of acteoside or PDTC (100 mg/kg/day) or vehicle for 7 days. On the seventh day, CVF (35 μg/kg) was administered via tail vein injection for 1 h, and lung tissues and BALF were then collected. The total protein concentration (A) and cell counts (B) in BALF were assessed. The superior and middle lobe of the right lung was excised to detect lung MPO activity (C). Results were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8). ##P < 0.01 was compared with the control group; ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 were compared with the CVF group. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; PDTC, pyrrolidinedithiocarbamic acid; CVF, cobra venom factor; MPO, myeloperoxidase; SEM, standard error of the mean.

We also detected amounts of total leucocytes in BALF and pulmonary MPO activity (an indicator of neutrophil infiltration [24, 31]). Compared with control mice, after 1 h of vein injection of CVF to mice, the counts of leucocytes (Figure 4B) and pulmonary MPO activity (Figure 4C) evidently increased, which indicated the presence of inflammatory cells and neutrophils recruitment in the lung. Compared with the CVF-challenged mice, mice pretreated with acteoside (100, 50, and 20 mg/kg) or 100 mg/kg of PDTC showed a significant (P < 0.01) reduction in leucocyte counts by 58.2%, 41.3%, 22.1%, and 43.9%, respectively (Figure 4B), and inhibition of CVF-induced MPO activity in mouse lungs by 23.7%, 17.8%, 11.1%, and 52%, respectively (Figure 4C). These results suggested that acteoside could attenuate lung edema and inflammation in a dose-dependent manner in CVF-challenged ALI mice.

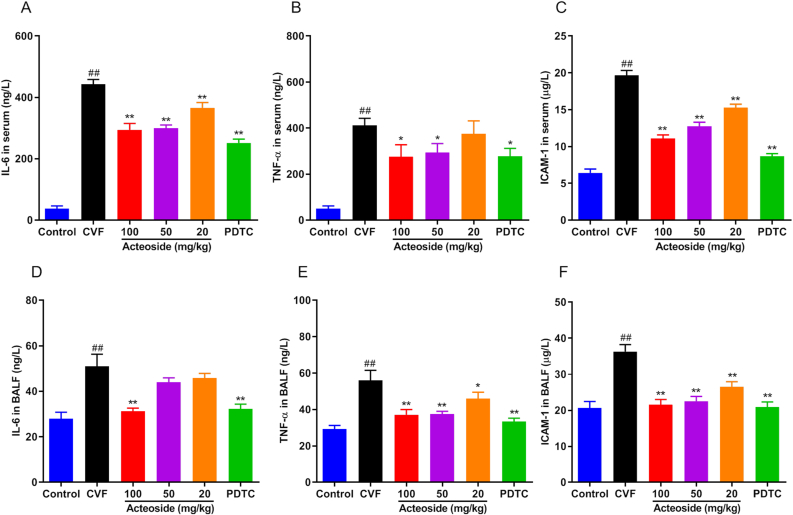

3.5. Acteoside reduces the high-level of CVF-induced inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in serum and mouse BLAF

We detected the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and ICAM-1 in serum and BALF by ELISA to evaluate the anti-inflammatory effect of acteoside on CVF-induced ALI. IL-6 and TNF-α are two of the most important cytokines at the early stage of inflammation, which play a vital role in ALI [32], while ICAM-1 participates in leukocyte recruitment into areas of inflammation [28]. As shown in Figures 5A-F, we found that the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and ICAM-1) in the serum and BALF of mice 1 h after CVF challenge were significantly increased (P < 0.01). Pretreatment with acteoside or PDTC evidently (P < 0.05, 0.01) down-regulated the CVF-induced IL-6, TNF-α, the ICAM-1 levels in mouse serum (Figures 5A-C) and BALF (Figures 5D-F). These data suggested that acteoside could reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in the serum of CVF-challenged mice in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 5.

Acteoside reduces inflammatory mediators and adhesion molecules in serum and BALF of ALI mice. Before administration with CVF to induced ALI, mice were orally pretreated with different concentrations (100, 50, and 20 mg/kg/day) of acteoside or PDTC (100 mg/kg/day) or vehicle for 7 days. Serum and BALF were collected 1 h after CVF (35 μg/kg) i.v. injection for the ELISA detection. A–C: IL-6, TNF-α, and ICAM-1 levels in serum; D–F: IL-6, TNF-α, and ICAM-1 in BALF. Results were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8). #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 were compared with the control group; ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 were compared with the CVF group. ALI, acute injury lung; CVF, cobra venom factor; PDTC, pyrrolidinedithiocarbamic acid; IL-6, interleukin-6; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; ICAM-1, intracellular adhesion molecule; SEM, standard error of the mean.

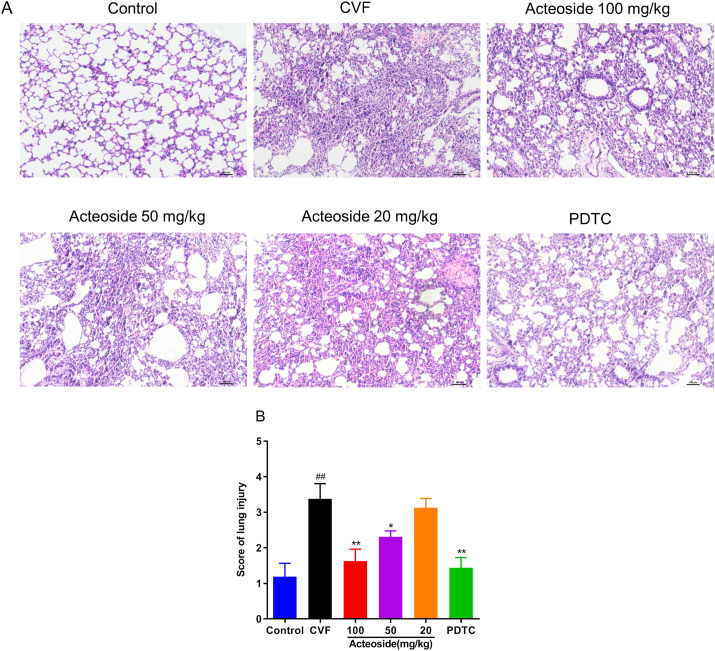

3.6. Acteoside attenuates CVF-induced lung pulmonary histopathological injury in mice

We next investigated the effects of acteoside on lung histopathology in mice challenged with CVF by complement activation. The lung tissues were harvested 1 h after CVF stimulation for pulmonary morphological observation (Figure 6A). Significant pathological changes, including pulmonary interstitial edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, and alveolar wall thickening, were observed in the lung tissues of CVF-challenged mice (P < 0.01) (Figures 6A and B). As expected, PDTC as positive control showed a significant reduction in the total score compared with CVF-challenged mice (Figure 6B). Pretreatment with acteoside (100 and 50 mg/kg) resulted in marked (P < 0.05, 0.01) reductions in the pathological score (Figure 6B). The data indicated the idea that acteoside was effective in suppressing CVF-induced lung injury.

Figure 6.

Histological examination of the lung tissue. (A) Mice were orally pretreated with different concentrations (100, 50, and 20 mg/kg/day) of acteoside or PDTC (as positive control, 100 mg/kg/day) or vehicle for 7 days. CVF (35 μg/kg) was then administered via tail vein injection for 1 h, and lung tissues were collected and subjected to H&E staining for histological evaluation (10×). (B) Lung injury score was graded from 0 (normal) to 4 (maximal damage) based on the severity of each indication, including alveolar congestion, hemorrhage, infiltration of leukocytes in the lung tissue, and thickness of the alveolar wall/hyaline membrane formation. Results were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8). #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 were compared with the control group; ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 were compared with the CVF group. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; ALI, acute injury lung; CVF, cobra venom factor; PDTC, pyrrolidinedithiocarbamic acid; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; SEM, standard error of the mean.

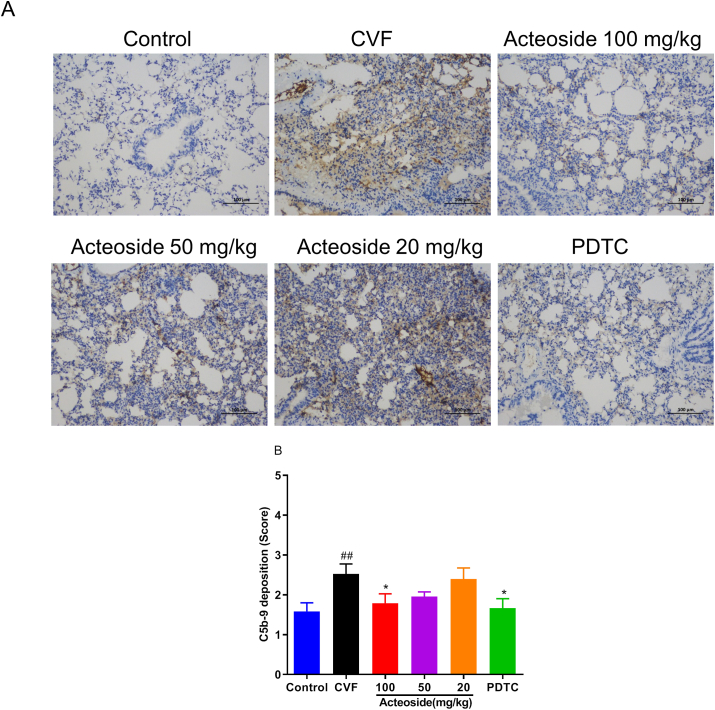

3.7. Acteoside inhibits the pulmonary C5b-9 deposition induced by CVF

Excessive activation of the alternative pathway of complement activation may lead to harmful amounts of the complement terminal component C5b-9, a potent activation product [33]. In the current experiment, the C5b-9 deposition in the lung tissue was examined to evaluate whether complement alternative pathway was overactivated. The results in Figures 7A and B showed that the C5b-9 deposition significantly increased in lung from CVF-treated mice (P < 0.01). Compared with mice challenged with CVF, pretreated with 100 mg/kg of acteoside and PDTC showed marked (P < 0.05) reductions of 29.01% and 33.96% in C5b-9 deposition, respectively (Figures 7A and B).

Figure 7.

Acteoside inhibits the C5b-9 deposition in lung tissue. The C5b-9 deposition was determined by immunohistochemistry, and the positive cells were marked by tan or brown (20×) (A). The scores was shown as mean ± SEM (n = 7–8) (B). ##P < 0.01 was compared with the control group; ∗P < 0.05 was compared with the CVF group. CVF, cobra venom factor; SEM, standard error of the mean.

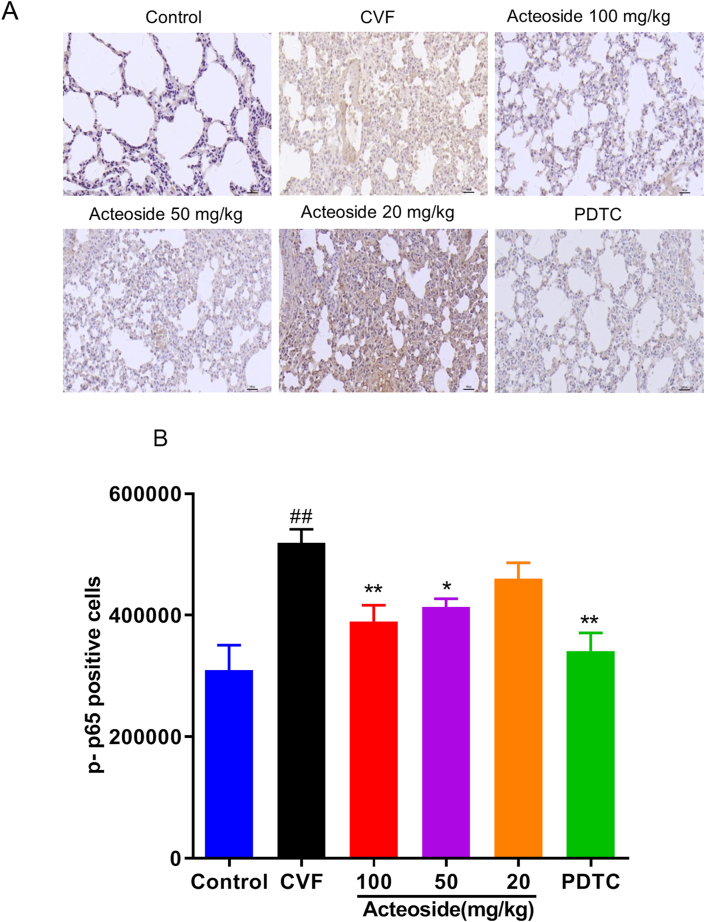

3.8. Acteoside suppresses the pulmonary NF-κB activation induced by CVF

Previous studies have shown that CVF could activate the expression of NF-κB in mouse lung tissue and lead to phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 [13]. Consistent with our previous result, CVF significantly increased the phospho–NF–κB p65 protein expression to 40.3% compared with control mice (P < 0.01) by immunohistochemistry (Figures 8A and B). Mice pretreated with 100 and 50 mg/kg of acteoside developed significantly less expression with 24.97% and 20.31% decrease, respectively, compared with mice challenged with CVF (P < 0.05, 0.01) (Figures 8A and B). As a positive drug, PDTC (100 mg/kg) significantly reduced CVF-triggered phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 with a 34.3% decrease (P < 0.01) (Figures 8A and B).

Figure 8.

Acteoside inhibits the expression of phosphorylated NF-κB p65 in lung tissue. NF-κB p65 phosphorylation was checked by immunohistochemistry, and the positive cells were presented by tan or brown (40×) (A). Results were quantified and presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8) (B). #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 were compared with the control group; ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 were compared with the CVF group. CVF, cobra venom factor; SEM, standard error of the mean.

4. Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that acteoside improved complement-induced lung injury and inhibited neutrophil infiltration and the release of inflammatory mediators in the lung. Moreover, the results indicated that the protective effect of acteoside on the ALI is highly related to the inhibition of NF-κB signaling activation.

ALI is an acute respiratory disorder characterized by acute pulmonary microvascular endothelial inflammation and intimal injury [2, 13], which are associated with inflammatory cascade reaction and a variety of inflammatory mediators and effector cells. In general, despite frequent exposure to invading pathogens, the lung is free of infection and inflammation primarily because of various defense systems such as complement system, which locally promotes pathogen clearance [34]. As an innate immune defense system, the complement system can be activated through three major pathways, namely, classical, lectin, and alternative, to protect the host from pathogenic challenge when an insult occurs in the lung [34]. However, inappropriate activation of complement may contribute to inflammatory response and tissue damage [12, 35]. The symptoms of ALI include excessive transepithelial neutrophil migration and the release of pro-inflammatory, cytotoxic mediators [10]. Exaggerated activation of complement can lead to neutrophil activation, sequestration, and adhesion to the pulmonary capillary endothelium, which results in damage of vascular endothelial cells and ALI [11]. The complement system has been proven to be extensively involved in various models of ALI [36, 37, 38, 39, 40]. Experimental and clinical evidence suggests that the activation of complement plays a pivotal role in the development of ALI [41].

CVF, a complement alternative-activating protein purified from cobra venom, can be used as an experimental tool to study the pathogenesis of ALI in laboratory animals. It can bind to factor B to form the CVF,B pro-convertase, which activates the complement alternative pathway and generates complement activation products, such as C3a, C5a, and C5b-9 (complement terminal component) [12], to induce ALI. The complement-activating pattern of CVF in the mouse model has a close resemblance to the observed complement activation in the pathological conditions of humans [13]. In addition, given that the engagement of the alternative pathway is necessary for these three activation pathways to induce lung tissue injury, we used CVF to study the mechanism of acteoside in preventing acute lung inflammation model induced by the activation of the complement alternative pathway in mice.

Intravascular activation of complement with CVF results in ALI, which has been quantitated on the basis of the stimulation of neutrophils, sequestration within capillaries of activated leukocytes, and subsequent damage of endothelial cells [15]. There is an increase in the permeability of the alveolar-capillary barrier in the early phase of ALI, which allows for an influx of fluid into the alveoli. Endothelium injury can increase capillary permeability, allow an influx of protein-rich fluid into the alveolar space, and promote the formation of pulmonary oedema [10]. Therefore, vascular endothelial cells are the chief target of injury for the activation of the complement system in acute lung inflammation processes [15]. As endothelial cells can express complement factors, regulators, and their receptors [42, 43], the endothelium may be markedly affected to produce complement deposition, leading to cell activation, expression of adhesion molecules (e.g., ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin), and release of cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6) [44]. During the process, NF-κB is activated, and NF-κB p65 triggers translocation to the nucleus to induce the expression of genes encoding for adhesion molecules and inflammatory cytokines on the activated endothelium [45]. Our previous study showed that the NF-κB signaling pathway was activated after CVF incubation products were added to microvascular endothelial cells, which were manifested by the upregulation of nuclear transcriptional activity, followed by changes in adhesion molecule expression and a series of inflammatory cytokines [22]. Therefore, based on the important role of microvascular endothelial cells in the pathogenesis of ALI, we first used HMEC in vitro to conduct the effects of acteoside on the inflammatory response and nuclear transcriptional activity caused by complement activation products (Figures 1, 2, and 3). The results showed that endothelial cells stimulated by CAC products could induce the upregulation of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin (Figures 1A-C) and the release of IL-6 and TNF-α (Figures 2A and B). Acteoside at different concentrations could significantly inhibit the upregulation of nuclear transcription activity (Figure 3) and the expression of adhesion molecules (Figures 1A-C) and inflammatory mediators (Figures 2A and B) in vitro. These results suggest that acteoside can down-regulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting the transcriptional activation of NF-κB, and further inhibit or reduce the inflammatory response, which indicates that acteoside has a certain intervention effect on the inflammatory response of HMEC induced by complement activation.

Based on the anti-inflammatory activities of acteoside in in vitro HMEC stimulated by CVF, the CVF-induced ALI model in mice was used to examine whether acteoside affected inflammation of ALI induced by complement activation accompanied with the high expression of complement terminal component C5b-9 deposition. In the present study, our data showed that acteoside significantly inhibited IL-6, TNF-α, and ICAM-1 production in serum and BALF (Figures 5A-F) as well as the inflammatory protein cell extravasation into BALF and MPO activity (Figures 4A-C) in lung tissue of mice in a dose-dependent manner. Meanwhile, acteoside markedly alleviated inflammatory infiltration and pathological changes (Figures 6A and B) and the C5b-9 deposition (Figures 7A and B) in lung tissue of mice. These results demonstrate that the inhibitory activity of acteoside against lung pulmonary histopathological injury induced by complement activation attributables to the suppression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecule expression.

The transcription factor NF-κB is upstream of the synthesis of acute phase pro-inflammatory mediators [31]. In resting cells, NF-κB is located in the cytoplasm, and it is bound with IκBα. When cells are stimulated by extracellular pro-inflammatory cytokines, NF-κB is released from the cytoplasm and then translocated into the nucleus, resulting in the expression of inflammatory genes such as adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin) and cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) [46]. Wang et al. reported that pretreatment or after-treatment with acteoside significantly inhibited phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 in the lung tissues in LPS-induced ALI mice [1]. In the present study, consistent with the inhibition of NF-κB activation by acteoside in LPS-induced ALI mice, we found that pretreatment with acteoside could also significantly decrease the phosphorylation level of NF-κB p65 in the nucleus in CVF-stimulated ALI mice (Figure 8 A and B). These data indicated that the inhibition of inflammatory mediators and cytokines by acteoside might be mediated by blocking the NF-κB in CVF-stimulated ALI mice. The Janus tyrosine kinase 2 (JAK2) signaling pathway is an important pathway activated by inflammation, which participates in many physiological processes [47]. The activation of the JAK2 pathway has been observed in ALI [47, 48]. It has been reported that JAK2 can be activated to a peak at 2 min after HMEC exposed to CAC [49]. AG490 is a well-known JAK2 inhibitor. The strong inhibitory effect of AG490 on the JAK2 pathway resulted in the inhibition of NF-κB p65 phosphorylation in HMEC exposed to CAC in vitro [50], which illustrated JAK2 may be an upstream regulatory site in the NF-κB and JAK2 regulatory network involved in inflammatory responses to complement activation stimulated HMEC. In addition, Qiao et al. [51] reported that acteoside was able to inhibit inflammatory response via JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Therefore, we speculate that JAK2 may be a more important regulatory locus for acteoside in CVF-induced ALI. It is no doubt that the detailed protective mechanism of acteoside for complement activated ALI needs to be further investigated.

5. Conclusion

The study confirmed the anti-inflammatory property of acteoside in complement-stimulated HMEC and complement-induced ALI in the mouse model. The protective effect of acteoside against ALI may be related to the inhibition of CVF-induced NF-κB activation, the decrease of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules and inflammatory cell infiltration, and the improvement of tissue impairment. Collectively, our study enriches the anti-inflammatory mechanism of acteoside and potentially has clinical application for ALI and other complement-driven inflammatory diseases.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Qing-Xiong Yang; Qian-Yun Sun: Conceived and designed the experiments.

Jing Guo: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Qiao-Zhou Liu: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Fang-Juan Zhu: Performed the experiments.

Min Li; Jiao Li; Li Guo: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

Qian-Yun Sun was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [U1812403], Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou Province [QKHRC [2016] 4018, QKHPTRC [2016] 5625, QKHPTRC [2019] 5702].

Qing-Xiong Yang was supported by State Key Laboratory of Functions and Applications of Medicinal Plants, Guizhou Medical University [No. FAMP201705K].

Jing Guo was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou Province [No. QKHJC [2017] 1115].

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [31760091].

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

Qian-Yun Sun, Email: sunqy@hotmail.com.

Qing-Xiong Yang, Email: yangqx@gznu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Wang J., Ma C.H., Wang S.M. Effects of acteoside on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in acute lung injury via regulation of NF-kappaB pathway in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015;285(2):128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthay M.A., Zimmerman G.A. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: four decades of inquiry into pathogenesis and rational management. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005;33(4):319–327. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salton F., Confalonieri P., Campisciano G., et al. Cytokine profiles as potential prognostic and therapeutic markers in SARS-CoV-2-induced ARDS. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11(11):2951. doi: 10.3390/jcm11112951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson J.G., Simpson L.J., Ferreira A.M., et al. Cytokine profile in plasma of severe COVID-19 does not differ from ARDS and sepsis. JCI Insight. 2020;5(17) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.140289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins R.A., Russ W.D., Rasmussen J.K., Clayton M.M. Activation of the complement system in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1987;135(3):651–658. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandya P.H., Wilkes D.S. Complement system in lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014;51(4):467–473. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0485TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunkelberger J.R., Song W.C. Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res. 2010;20(1):34–50. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holers V.M. The complement system as a therapeutic target in autoimmunity. Clin. Immunol. 2003;107(3):140–151. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thurman J.M., Holers V.M. The central role of the alternative complement pathway in human disease. J. Immunol. 2006;176(3):1305–1310. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mowery N.T., Terzian W.T.H., Nelson A.C. Acute lung injury. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2020;57(5):100777. doi: 10.1016/j.cpsurg.2020.100777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosmann M., Ward P.A. Role of C3, C5 and anaphylatoxin receptors in acute lung injury and in sepsis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012;946:147–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0106-3_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogel C.W., Fritzinger D.C. Cobra venom factor: structure, function, and humanization for therapeutic complement depletion. Toxicon. 2010;56(7):1198–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo J., Li M., Yang Y., et al. Pretreatment with atorvastatin ameliorates cobra venom factor-induced acute lung inflammation in mice. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020;20(1):263. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-01307-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagio T., Nakao S., Matsuoka H., et al. Inhibition of neutrophil elastase activity attenuates complement-mediated lung injury in the hamster. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;426(1-2):131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Till G.O., Johnson K.J., Kunkel R., Ward P.A. Intravascular activation of complement and acute lung injury. Dependency on neutrophils and toxic oxygen metabolites. J. Clin. Invest. 1982;69(5):1126–1135. doi: 10.1172/JCI110548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Till G.O., Ward P.A. Systemic complement activation and acute lung injury. Fed. Proc. 1986;45(1):13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He J., Hu X.P., Zeng Y., et al. Advanced research on acteoside for chemistry and bioactivities. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2011;13(5):449–464. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2011.568940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu X., He W., Zhang H., et al. Acteoside: a lipase inhibitor from the Chinese tea Ligustrum purpurascens kudingcha. Food Chem. 2014;142:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alipieva K., Korkina L., Orhan I.E., Georgiev M.I. Verbascoside--a review of its occurrence, (bio)synthesis and pharmacological significance. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014;32(6):1065–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Q.Y., Chen G., Guo H., et al. Prolonged cardiac xenograft survival in Guinea pig-to-rat model by a highly active cobra venom factor. Toxicon. 2003;42(3):257–262. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(03)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye Q.L., Sun Q.Y., Li M. Inflammatory mediators releasing and apoptosis of endothelial cell induced by cobra venom metalloproteinase atrase A (in Chinese) Chin. Pharmacol. Bull. 2009;25(8):1001–1006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J., Guo J., Li M., Sun Q.Y. Intervention effect of tetramethylpyrazine on inflammatory response of endothelial cells induced by activated complement alternative pathway (in Chinese) Chin. Pharmacol. Bull. 2019;35(1):90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proctor L.M., Strachan A.J., Woodruff T.M., et al. Complement inhibitors selectively attenuate injury following administration of cobra venom factor to rats. Int. Immunopharm. 2006;6(8):1224–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldblum S.E., Wu K.M., Jay M. Lung myeloperoxidase as a measure of pulmonary leukostasis in rabbits. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985;59(6):1978–1985. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.59.6.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schingnitz U., Hartmann K., Macmanus C.F., et al. Signaling through the A2B adenosine receptor dampens endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. J. Immunol. 2010;184(9):5271–5279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilgore K.S., Shen J.P., Miller B.F., et al. Enhancement by the complement membrane attack complex of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced endothelial cell expression of E-selectin and ICAM-1. J. Immunol. 1995;155(3):1434–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozada C., Levin R.I., Huie M., et al. Identification of C1q as the heat-labile serum cofactor required for immune complexes to stimulate endothelial expression of the adhesion molecules E-selectin and intercellular and vascular cell adhesion molecules 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92(18):8378–8382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward P.A. Role of complement, chemokines, and regulatory cytokines in acute lung injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1996;796:104–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb32572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Q.Y., Li M., Ye Q.L., Li H.L. Endothelial cell activation and injury induced by complement alternative pathway (in Chinese) Chin. Pharma. Bull. 2012;28(7):925–929. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahman A., Fazal F. Blocking NF-κB: an inflammatory issue. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2011;8(6):497–503. doi: 10.1513/pats.201101-009MW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liaudet L., Pacher P., Mabley J.G., et al. Activation of poly (ADP-Ribose) polymerase-1 is a central mechanism of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;165(3):372–377. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.3.2106050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z., Luo Z., Bi A., et al. Compound edaravone alleviates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017;811:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmid E., Warner R.L., Crouch L.D., et al. Neutrophil chemotactic activity and C5a following systemic activation of complement in rats. Inflammation. 1997;21(3):325–333. doi: 10.1023/a:1027302017117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolger M.S., Ross D.S., Jiang H., et al. Complement levels and activity in the normal and LPS-injured lung. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2007;292(3):L748–759. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00127.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markiewski M.M., Lambris J.D. The role of complement in inflammatory diseases from behind the scenes into the spotlight. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171(3):715–727. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClintock S.D., Hoesel L.M., Das S.K., et al. Attenuation of half sulfur mustard gas-induced acute lung injury in rats. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2006;26(2):126–131. doi: 10.1002/jat.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun S.H., Wang H.B., Zhao G.Y., et al. A role for complement in paraquat-induced acute lung injury. Mol. Immunol. 2010;47(13):2212–2213. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang R., Xiao H., Guo R., et al. The role of C5a in acute lung injury induced by highly pathogenic viral infections. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2015;4(5):e28. doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu X., Yao D., Bao L., et al. Ficolin A derived from local macrophages and neutrophils protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by activating complement. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2020;98(7):595–606. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zambelli V., Rizzi L., Delvecchio P., et al. JMV5656, a short synthetic derivative of TLQP-21, alleviates acid-induced lung injury and fibrosis in mice. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;62 doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2020.101916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Till G.O., Morganroth M.L., Kunkel R., Ward P.A. Activation of C5 by cobra venom factor is required in neutrophil-mediated lung injury in the rat. Am. J. Pathol. 1987;129(1):44–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Acosta J., Qin X., Halperin J. Complement and complement regulatory proteins as potential molecular targets for vascular diseases. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 2004;10(2):203–211. doi: 10.2174/1381612043453441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Langeggen H., Pausa M., Johnson E., et al. The endothelium is an extrahepatic site of synthesis of the seventh component of the complement system. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2000;121(1):69–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01238.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karpman D., Stahl A.L., Arvidsson I., et al. Complement interactions with blood cells, endothelial cells and microvesicles in thrombotic and inflammatory conditions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015;865:19–42. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18603-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zoja C., Buelli S., Morigi M. Shiga toxin triggers endothelial and podocyte injury: the role of complement activation. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2019;34(3):379–388. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3850-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pahl H.L. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18(49):6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao X., Zhao B., Zhao Y., et al. Protective effect of anisodamine on bleomycin-induced acute lung injury in immature rats via modulating oxidative stress, inflammation, and cell apoptosis by inhibiting the JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021;9(10):859. doi: 10.21037/atm-21-1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cao F., Tian X., Li Z., et al. Suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome by erythropoietin via the EPOR/JAK2/STAT3 pathway contributes to attenuation of acute lung injury in mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11:306. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H.L., Sun Q.Y., Li M., Shi J.S. Activation of NF-κB, p38MAPK, and JAK2 in endothelial cells induced by activated complement alternative pathway and intervention by inhibitors (in Chinese), Chin. J. Cell Biol. 2013;35(6):836–841. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li C.S., Sun Q.Y. Effect of three chemical molecules on adhesion molecules expression in HMECs induced by activated complement alternative pathway (in Chinese) Chin. Pharmacol. Bull. 2015;31(10):1421–1426. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qiao Z., Tang J., Wu W., et al. Acteoside inhibits inflammatory response via JAK/STAT signaling pathway in osteoarthritic rats. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2019;19(1):264. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.