Abstract

Internalization of group A streptococcus (GAS) by epithelial cells may have a role in causing invasive diseases. The purpose of this study was to examine the fate of GAS-infected epithelial cells. GAS has the ability to invade A-549 and HEp-2 cells. Both A-549 and HEp-2 cells were killed by infection with GAS. Epithelial cell death mediated by GAS was at least in part through apoptosis, as shown by changes in cellular morphology, DNA fragmentation laddering, and propidium iodide staining for hypodiploid cells. A total of 20% of A-549 cells and 11 to 13% of HEp-2 cells underwent apoptosis after 20 h of GAS infection, whereas only 1 to 2% of these cells exhibited spontaneous apoptosis. We further examined whether streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B (SPE B), a cysteine protease produced by GAS, was involved in the apoptosis of epithelial cells. The speB isogenic mutants had less ability to induce cell death than wild-type strains. When A-549 cells were cocultured with the mutant and SPE B for 2 h, the percentage of apoptotic cells did not increase although the number of intracellular bacteria increased to the level of wild-type strains. In addition, apoptosis was blocked by cytochalasin D treatment, which interfered with cytoskeleton function. The caspase inhibitors Z-VAD.FMK, Ac-YVAD.CMK, and Ac-DEVD.FMK inhibited GAS-induced apoptosis. These results demonstrate for the first time that GAS induces apoptosis of epithelial cells and internalization is required for apoptosis. The caspase pathway is involved in GAS-induced apoptosis, and the expression of SPE B in the cells enhances apoptosis.

Recent studies have opened the new area of bacterium-induced killing of host cells by activation of their intrinsic cell death program, leading to apoptosis. Among the cells examined phagocytic macrophages have been most extensively studied (6, 7, 12, 26, 42). Apoptosis was shown to be induced by a wide range of pathogens, including Shigella flexneri (43), Bordetella pertussis (20), Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (18), Legionella pneumophila (32), Listeria monocytogenes (9), Salmonella typhimurium (31), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (19), Yersinia enterocolitica (35), Corynebacterium diphtheriae (21), Pseudomonas spp. (21), and group A streptococcus (GAS) (23). Apoptosis is characterized by specific morphological changes, including cell shrinkage and chromatin condensation, followed by nuclear and cytoplasmic fragmentation. An early event in apoptosis is the DNA cleavage into multiples approximately 200 bp in length (1). The fragments are thought to represent chromatin DNA that is cleaved between adjacent nucleosomes (41). Several lines of evidence indicate that macrophage apoptosis induced by Shigella, Salmonella, and Yersinia spp. shows a proinflammatory event (12, 27, 35) which has been suggested to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of bacterial infection. Recently, Staphylococcus aureus has been shown to be able to induce apoptosis in both epithelial and endothelial cells (2, 29).

GAS is an important human pathogen that causes infections of pharyngitis, cellulitis, impetigo, and severe invasive diseases such as rheumatic fever, scarlet fever, necrotizing fasciitis, and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (33, 37, 38). We and others have previously reported the invasion of epithelial cells by GAS (8, 13, 24, 30, 39). However, the fate of infected epithelial cells is far from clear. It is of interest to know whether these epithelial cells would undergo apoptosis after GAS invasion. Although the pathogenic factors of GAS are poorly defined, many studies indicate that streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B (SPE B), a cysteine protease, plays a role in severe disease (3, 4, 11, 15, 17, 22, 28, 40). The function of SPE B is similar to that of interleukin-1β (IL-1β)-converting enzyme, which cleaves IL-1β precursor to produce active IL-1β in vitro (16). In addition, purified SPE B protein can induce apoptosis and reduce phagocytic activity in U937 cells (23). SPE B is also involved in the internalization of GAS in epithelial cells (39). In this study, we show that epithelial cell cytotoxicity mediated by GAS occurs at least in part through apoptosis and that GAS internalization is required for this effect. We also show that GAS-induced apoptosis is via the caspase pathway and is enhanced by the presence of SPE B.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and tissue culture cells.

GAS strain A-20 (type M1, T1, OF negative) was recovered from a patient with necrotizing fasciitis. Strain NZ131 (type M49, T14) was kindly provided by D. R. Martin (New Zealand Communicable Disease Center, Porirua). The isogenic speB mutants of A-20 and NZ131 were designated SW507 and SW510, respectively, as previously described (39). All GAS cultures were grown in tryptic soy broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (TSBY). The bacteria were washed once and resuspended in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 108 bacteria/ml. The desired bacterial concentration was adjusted by measuring the optical density at 600 nm and checked by plating serial dilutions of the samples on TSBY agar and counting CFU after incubation overnight at 35°C. All strains were stored at −70°C in TSBY broth with 15% glycerol until testing. Human alveolar carcinoma epithelial cell monolayers (A-549; ATCC CCL-185) and human epidermoid carcinoma epithelial cell monolayers (HEp-2; ATCC CCL-23) were used for all assays and were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; GIBCO Laboratories, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; GIBCO Laboratories), penicillin (100 μg/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (0.25 mg/ml). The cells were subcultured every second day.

Invasion assay.

Invasion assays were performed as previously described (39).

Cytotoxicity assay.

The cytotoxicity assay was based on the method of Patrick et al. (34). In brief, cells (5 × 104 per well) were seeded into a 96-well plate and infected with GAS at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1, 25, 50, or 100 for 2 h. The culture medium was then replaced with fresh culture medium supplemented with 8 μg of penicillin per ml. After a 20-h incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the dye WST-1 (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The microtiter plates were read on a kinetic microplate reader (V-max; Molecular Devices Corporation, Menlo Park, Calif.) at a wavelength of 450 to 650 nm. The percent cytotoxicity was calculated as 100 × (1 − optical density at 450 to 650 nm of infected cells/optical density at 450 to 650 nm of uninfected cells).

A cytotoxicity kinetic assay was done as described above except that cells were infected at an MOI of 100 for 2 h and incubated for 0, 8, and 20 h before the dye WST-1 was added.

Morphological staining.

Cells (5 × 105) were seeded on a glass slide and infected with GAS at an MOI of 100 for 2 h. After incubation for 20 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, the cells were washed three times with prewarmed 1× PBS, fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde in 1× PBS, and incubated for 20 min at room temperature with 1 ml of hematoxylin (Sigma Diagnostics, St. Louis, Mo.). Slides were washed three times with 1× PBS and covered with glycerol-gelatin (Sigma Diagnostics) to prepare permanent samples. Morphological changes of A-549 cells were analyzed by light microscopy after 20 h of incubation. As a negative control, noninfected cells were incubated in DMEM–10% FCS and subjected to the same treatment as the infected cells.

Analysis of DNA fragmentation.

DNA fragmentation gel electrophoresis was analyzed as described previously (25), with modification. A-549 cells (5 × 105 per well) were infected with GAS at an MOI of 100 for 2 h. After 20 h of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the cells were harvested by the addition of 1 ml of 0.1% EDTA. The cells were lysed with lysis buffer (0.2% Triton X-100, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) at room temperature for 10 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was treated with proteinase K (100 μg/ml) for 1 h at 50°C, and then RNase (0.5 μg/ml) was added for 1 h at 50°C. The lysates were extracted twice with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform (1:1, vol/vol) and once with an equal volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1, vol/vol) before precipitation with ethanol. The precipitates were dried and solubilized in 1× TE (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA). Electrophoresis was performed with a 2% agarose gel, and DNA was stained with ethidium bromide. As a negative control, noninfected cells were treated by the same procedure as the infected cells.

Quantitation of apoptotic cells.

Cells infected by GAS were fixed at −20°C with 70% ethanol and then treated with 100 μg of RNase per ml. After being washed once with 1× PBS, cells were stained with propidium iodide (40 μg/ml in 1× PBS; Sigma Diagnostics) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Apoptotic cells were quantified with a flow cytometer (FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.) with excitation set at 488 nm and presented as percentage of hypodipoid cells. To assess whether the bacteria must be viable to induce apoptosis, heat-inactivated bacteria were used for infection as an additional control. Heat inactivation was achieved by heating the bacterial suspension at 95°C for 30 min, and complete inactivation was verified by plating an aliquot on TSBY plates. In some experiments, purified SPE B was added to the cell cultures. The purified SPE B was prepared from GAS NZ131 as previously described (22). Purified SPE B was diluted to 30 μg/ml with 1× PBS and added together with GAS to A-549 cells, which were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The quantitation of apoptotic cells was carried out as described above.

Inhibition of GAS internalization.

Epithelial cells (5 × 104 per well) were seeded in a 24-well plate, and cells were pretreated with 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 μg of cytochalasin D (Sigma Diagnostics) per ml for 90 min before infection. The cells were then infected with GAS at an MOI of 100 for 2 h. The invasion assay and quantitation of apoptotic cells were done as described above.

Caspase inhibitor assay.

Cells (5 × 104 per well) were seeded in a 96-well plate and pretreated with caspase inhibitors (8 μM) for 2 h before infection. Caspase inhibitors used included the caspase-1 inhibitors Z-VAD.FMK and Ac-YVAD.CMK and the caspase-3 inhibitor Ac-DEVD.FMK (Clontech Laboratories Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). Infections were performed at an MOI of 100 for 2 h. Then the culture medium was replaced by fresh medium supplemented with 8 μg of penicillin per ml and caspase inhibitors (8 μM). The rest of the procedure was as described for the cytotoxicity assay.

Statistics.

The difference in percentages of apoptotic cells induced by wild-type strains and isogenic mutants was analyzed by Student’s two-tailed t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Invasion assay.

We previously showed the invasion of A-549 cells by GAS (39). To study the internalization of GAS in other cell lines, we examined the ability of GAS A-20 to invade the human epithelial cell line HEp-2. Monolayers of HEp-2 cells were infected with GAS for 2 h before the addition of penicillin to eliminate extracellular bacteria. The penicillin-protected bacteria were analyzed by lysing the infected cells, and the numbers of intracellular bacteria were determined by plating on TSBY agar. The results showed that the invasion level of A-20 in HEp-2 cells, represented as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) from four separate experiments, was (8.93 ± 0.35) × 104 CFU/ml. The rate of internalization in HEp-2 cells was similar to that reported previously for A-549 cells (39).

GAS-induced cytotoxicity.

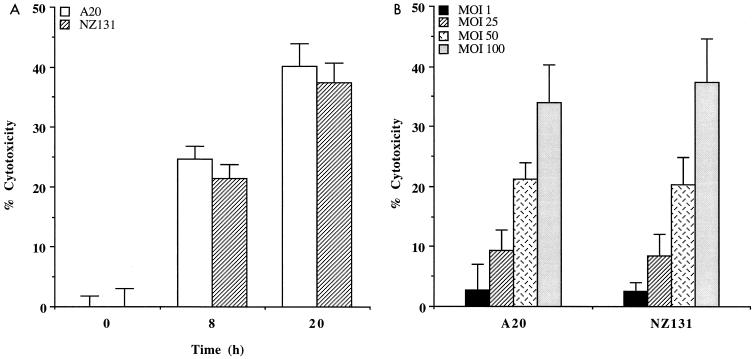

GAS-induced cytotoxicity was determined by measuring of the formazan dye in viable cells. In the presence of viable cells, active mitochondria can cleave the tetrazolium salt WST-1 to produce a soluble formazan salt that can be quantitated with a spectrophotometer. As shown in Fig. 1A, a significant increase of cell death in A-549 cells was observed at 8 and 20 h after treatment with strains A-20 and NZ131. A dose-dependent cytotoxicity in A-549 cells was observed after 20 h of incubation with both strains (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) Effects of time course on cytotoxicity of A-549 cells by GAS. A-549 cells were infected with A-20 for 2 h at an MOI of 100 and incubated for 0, 8, and 20 h before the dye WST-1 was added. (B) Effects of inoculum size on cytotoxicity of A-549 cells by GAS. A-549 cells were infected with various concentrations of GAS at MOIs of 1, 25, 50, and 100 for 2 h before the dye WST-1 was added. Data are from a representative experiment repeated three times. Bars represent mean levels for triplicate cultures ± SEM.

Morphological changes of epithelial cells upon GAS infection.

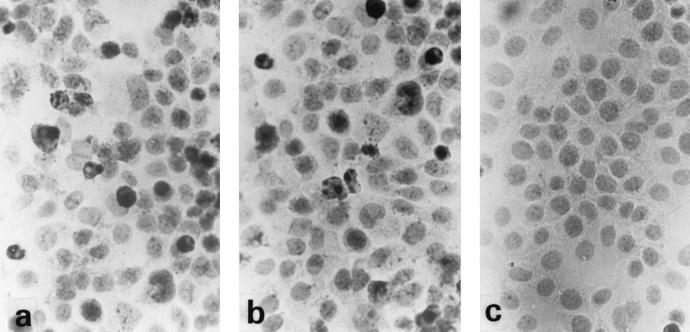

The A-549 cells were infected with A-20 and NZ131 for 2 h prior to penicillin treatment to kill the extracellular bacteria. The cells were fixed, and morphological changes were analyzed by light microscopy following 20 h of incubation. As shown in Fig. 2, a remarkable difference in morphology was observed between infected and noninfected A-549 cells. The infected cells showed a condensed nuclear morphology (Fig. 2a and b), whereas the majority of noninfected cells had a normal healthy appearance with no signs of chromatin condensation (Fig. 2c). Similar morphological changes were observed in infected HEp-2 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effects of GAS on A-549 cell morphology. A-549 cells were infected with A-20 (a) or NZ131 (b) (MOI of 100, 2 h) or were not infected (c). After 20 h, the cells were fixed and stained with hematoxylin. Magnification, ×100.

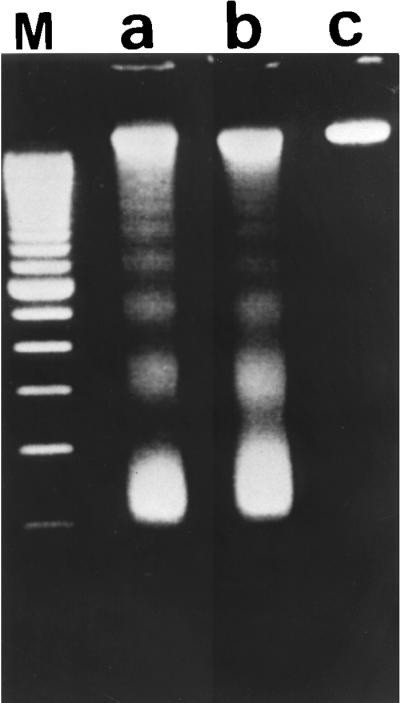

GAS induces DNA fragmentation in epithelial cells.

As described above, the morphological features of infected epithelial cells suggested that these cells may undergo apoptosis. One of the characteristics of apoptosis is the fragmentation of DNA into multimers of 180 to 200 bp. We therefore examined the induction of DNA fragmentation by GAS in the epithelial cells. DNA fragmentation was observed in cells infected with A-20 and NZ131 for 20 h but not in noninfected cells (Fig. 3). Results were similar for HEp-2 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Effects of GAS on DNA fragmentation of A-549 cells. DNA was extracted from A-549 cells infected with A-20 (lane a) or NZ131 (lane b) (MOI of 100, 2 h) or not infected (lane c). Electrophoresis was performed with a 2% agarose gel, and DNA was stained with ethidium bromide. Lane M, 100-bp marker.

Quantitation of apoptotic cells.

The proportions of apoptotic cells in GAS-infected A-549 and HEp-2 cells were further determined by propidium iodide staining. Apoptotic cells were quantified by flow cytometry and presented as percentage of hypodiploid cells. As shown in Table 1, internalization of A-20 and NZ131 by A-549 cells led to apoptosis, whereas heat-inactivated bacteria had no effect. A-20 and NZ131 also induced apoptosis in HEp-2 cells, although at levels lower than in A-549 cells (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

GAS-induced apoptosis in A-549 and HEp-2 cells, monitored by flow cytometry

| Strain | Mean % apoptotic cells ± SEMa (n = 3)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-549

|

HEp-2, untreated | ||||

| No treatment | Heated-inactivated (95°C, 30 min) GAS | Purified SPE B (30 μg/ml) | Cytochalasin D (0.5 μg/ml) | ||

| A-20 | 20.02 ± 0.59 | 1.35 ± 0.21 | 19.35 ± 0.83 | 2.77 ± 0.54 | 11.45 ± 0.99 |

| SW507 | 13.19 ± 0.23** | 1.00 ± 0.42 | 14.63 ± 0.04* | 3.93 ± 0.55 | 6.93 ± 1.07* |

| NZ131 | 20.79 ± 1.03 | 1.60 ± 0.71 | ND | 2.50 ± 0.17 | 13.17 ± 1.24 |

| SW510 | 15.02 ± 0.32** | 1.10 ± 0.14 | ND | 2.53 ± 0.73 | 8.03 ± 0.81* |

| 2.02 ± 0.15 | ND | 1.80 ± 0.26 | 2.28 ± 0.38 | 2.39 ± 0.15 | |

Values were compared between the wild-type strain and its isogenic speB mutant by unpaired t tests: ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01. ND, not done.

Effect of SPE B on GAS-induced apoptosis.

To determine whether SPE B was involved in GAS-induced cell apoptosis, we compared the percentages of apoptotic cells induced by the wild-type strains and their isogenic speB mutants. Wild-type strains A-20 and NZ131 induced levels of apoptosis higher than those induced by isogenic mutants SW507 and SW510 in A-549 cells (Table 1). Statistically significant differences (P < 0.01) between wild-type and mutant strains were noted. A similar observation was made for HEp-2 cells (Table 1). The difference between wild-type strains and isogenic mutants in the ability to induce apoptosis may be due to the difference in numbers of intracellular bacteria. To further test this possibility, purified SPE B was reconstituted in the culture and mixed with GAS prior to the addition of epithelial cells. After a 2-h incubation, the intracellular numbers of the mutant increased to a level similar to that of the wild-type strain (data not shown). However, SPE B reconstitution in the mutant did not cause a significant increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells (Table 1).

Effect of cytochalasin D on GAS-induced apoptosis.

To determine whether bacterial internalization was required for GAS-induced apoptosis, cytochalasin D was used to inhibit internalization. Apoptosis was reduced to the basal levels when A-549 cells were treated with 0.5 μg of cytochalasin D per ml prior to GAS infection (Table 1). Similar results were obtained when 1 and 1.5 μg of cytochalasin D per ml were used (data not shown).

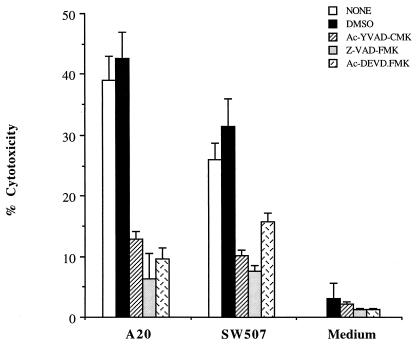

Effect of caspase inhibitors on GAS-induced apoptosis.

To determine whether the caspase pathway was involved in GAS-induced apoptosis, the caspase inhibitors Z-VAD.FMK, Ac-YVAD.CMK, and Ac-DEVD.FMK were added to the cultures. As shown in Fig. 4, the caspase inhibitors alone did not affect cell cytotoxicity after 20 h of incubation. In the presence of caspase inhibitors, A-20-induced death of A-549 cells was reduced by 67, 84, and 76% after treatment with Z-VAD.FMK, Ac-YVAD.CMK, and Ac-DEVD.FMK, respectively. A similar observation was made for the groups infected with isogenic speB mutant SW507 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Effects of caspase inhibitors on cytotoxicity of A-549 cells by GAS. A-549 cells were infected with GAS in the presence or absence of caspase inhibitors (MOI of 100, 2 h). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), the solvent for the caspase inhibitors, was used as a control. Cells were preincubated with caspase inhibitors for 2 h and cultured for an additional 20 h after GAS infection. Data are from a representative experiment repeated three times. Bars represent mean levels for triplicate cultures ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

Although recent evidence suggested that GAS, an extracellular pathogen, can be internalized by epithelial cells (8, 13, 24, 30, 39), the fate of these cells after GAS internalization is not known. In this report, we provide the first evidence that GAS can induce apoptosis in epithelial cells. We stained infected and noninfected cells and compared their morphologies. There were dramatic morphological changes, chromatin condensation, and segmentation of the nucleus, typical characteristics of apoptotic cells (Fig. 2). Furthermore, epithelial cells infected with GAS exhibited a pattern of DNA fragmentation laddering which was linked to the activation of an internucleosomal nuclease in apoptotic cells (Fig. 3). The ability of GAS to induce apoptosis in A-549 cells was inhibited by cytochalasin D, indicating that the bacteria must be within the cell to induce apoptosis (Table 1). A similar observation was made for S. flexneri (43).

To determine if SPE B, a cysteine protease, was involved in GAS-induced apoptosis, we compared the induction of apoptosis in epithelial cells by the wild-type strains and the isogenic speB mutants. The magnitude of apoptosis induced by the mutants was less than that induced by the wild-type strains (Table 1). A plausible explanation for why the speB mutants are less able to induce cell apoptosis is that fewer mutant bacteria than wild-type bacteria invaded the epithelial cells. When purified SPE B and the mutant were cocultured with A-549 cells, the intracellular number of bacteria increased to a level similar to that of the wild-type strain. However, the percentage of apoptotic cells did not increase. These data suggest that intracellular expression of SPE B is necessary to enhance the cell death program in A-549 cells. Whether SPE B is expressed in the epithelial cells after GAS internalization requires further study.

The caspase family of cysteine proteases has been shown to play important roles in regulation of apoptosis and inflammatory response (36). The induction of macrophage apoptosis by S. flexneri was mediated by the binding of IpaB invasin to caspase-1 (5). IpaB binding appeared to upregulate caspase-1 activity, and specific inhibition of caspase-1 prevented Shigella-induced apoptosis. A similar observation was made for S. typhimurium SipB, which is homologous to IpaB and was required for cell death in S. typhimurium-infected macrophages (5, 10, 14). However, initiation of apoptosis was independent of caspase-1 in Y. enterocolitica (35). In this study, we found that the A-20-mediated cytotoxicity of infected cells was reduced by the caspase-1 family of inhibitors (Fig. 4). These data suggested that the caspase-1 activity was upregulated in human epithelial cells after GAS infection. Whether SPE B as a cysteine protease plays a role in increasing caspase-1 activity remains to be determined. However, treatment with caspase-1 inhibitors may also reduce the cytotoxicity mediated by the isogenic speB mutant SW507. Therefore, factors other than SPE B of GAS should also be considered to be involved in caspase-1 activation. In GAS, there is an extracellular region of M protein that is homologous to the corresponding portion of IpaB, and our preliminary study showed that the isogenic M protein mutant caused a level of apoptosis lower than that caused by the wild type. Whether M protein has a caspase-1 binding activity similar to that of IpaB remains to be determined. Besides the activation of caspase-1, this study also demonstrated the involvement of caspase-3 in the apoptotic pathway induced by both wild-type A-20 and its speB mutant SW507. Mechanisms other than caspase-induced apoptosis are also involved in the GAS-induced cytotoxic effect, since 5 to 10% of cytotoxicity remains unaffected by the caspase inhibitors.

Although many pathogenic microorganisms cause apoptosis, most induce apoptosis in macrophage cell lines (6, 12, 42). In Shigella and Salmonella infections, the paradigm of bacterium-induced apoptosis, it was shown that the effects of apoptosis were not only to delete cells but also to initiate inflammation (12, 42). For GAS, there is no direct evidence supporting this hypothesis. However, SPE B can cleave inactive IL-1β precursor (16) and trigger apoptosis in phagocytic cells (23), indicating that apoptosis induced by GAS may be involved in the initiation of inflammation. The ability to kill nonphagocytic cells might be beneficial for survival of the pathogenic microorganisms and invasion of the deeper tissues. Though observed in vitro in only 20% of infected A-549 cells GAS-induced apoptosis may play a role in the pathogenesis of GAS infection. Whether apoptosis in nonphagocytic cells is primarily a strategy developed by GAS for survival and spreading or a defensive response by the host remains unclear. It should be noted that tissue necrosis is a clinical feature characterized primarily in severe streptococcal infections. Whether apoptosis induced by GAS also occurs in vivo remains to be determined.

In summary we have demonstrated GAS-induced epithelial cell death characterized by changes in morphology, fragmentation of DNA, and propidium iodide staining for hypodiploid cells. Internalization of viable bacteria was required for cells to induce apoptosis, and SPE B enhanced the level of apoptosis. Although the mechanism by which GAS induces apoptosis is not yet clear, our data demonstrate involvement of the caspase pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partly supported by grants NSC 87-2314-B006-056 and NSC 88-2314-B006-076 from the National Science Council, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson P. Kinase cascades regulating entry into apoptosis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:33–46. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.33-46.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayles K W, Wesson C A, Liou L E, Fox L K, Bohach G A, Trumble W R. Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus escapes the endosome and induces apoptosis in epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:336–342. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.336-342.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berge A, Bjorck L. Streptococcal cysteine proteinase releases biologically active fragments of streptococcal surface proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9862–9867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns E H, Jr, Marciel A M, Musser J M. Structure-function and pathogenesis studies of Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;418:589–592. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1825-3_136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Smith M R, Thirumalai K, Zychlinsky A. A bacterial invasin induces macrophage apoptosis by binding directly to ICE. EMBO J. 1996;15:3853–3860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Zychlinsky A. Apoptosis induced by bacterial pathogens. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:203–212. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finlay B B, Cossart P. Exploitation of mammalian host cell functions by bacterial pathogens. Science. 1997;276:718–725. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greco R, De Martino L, Donnarumma G, Conte M P, Seganti L, Valenti P. Invasion of cultured human cells by Streptococcus pyogenes. Res Microbiol. 1995;146:551–560. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)80561-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman C A, Domann E, Rohde M, Bruder D, Darji A, Weiss S, Wehland J, Chakraborty T, Timmis K N. Apoptosis of mouse dendritic cells is triggered by listeriolysin, the major virulence determinant of L. monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermant D, Menard R, Arricau N, Parsot C, Popoff M Y. Functional conservation of the Salmonella and Shigella effectors of entry into epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:781–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17040781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herwald H, Collin M, Muller-Esterl W, Bjorck L. Streptococcal cysteine proteinase releases kinins: a virulence mechanism. J Exp Med. 1996;184:665–673. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilbi H, Zychlinsky A, Sansonetti P J. Macrophage apoptosis in microbial infections. Parasitology. 1997;115:S79–S87. doi: 10.1017/s0031182097001790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadoun J, Ozeri V, Burstein E, Skutelsky E, Hanski E, Sela S. Protein F1 is required for efficient entry of Streptococcus pyogenes into epithelial cells. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:147–158. doi: 10.1086/515589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaniga K, Tucker S, Trollinger D, Galán J E. Homologs of the Shigella IpaB and IpaC invasins are required for Salmonella typhimurium entry into cultured epithelial cells. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3965–3971. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3965-3971.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapur V, Maffei J T, Greer R S, Li L L, Adams G J, Musser J M. Vaccination with streptococcal extracellular cysteine protease (interleukin-1 beta convertase) protects mice against challenge with heterologous group A streptococci. Microb Pathog. 1994;16:443–450. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapur V, Majesky M W, Li L L, Black R A, Musser J M. Cleavage of interleukin 1 beta (IL-1 beta) precursor to produce active IL-1 beta by a conserved extracellular cysteine protease from Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7676–7680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapur V, Topouzis S, Majesky M W, Li L L, Hamrick M R, Hamill R J, Patti J M, Musser J M. A conserved Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease cleaves human fibronectin and degrades vitronectin. Microb Pathog. 1993;15:327–346. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato S, Muro M, Akifusa S, Hanada N, Semba I, Fujii T, Kowashi Y, Nishihara T. Evidence for apoptosis of murine macrophages by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3914–3919. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3914-3919.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keane J, Balcewicz-Sablinska M K, Remold H G, Chupp G L, Meek B B, Fenton M J, Kornfeld H. Infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis promotes human alveolar macrophage apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:298–304. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.298-304.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khelef N, Zychlinsky A, Guiso N. Bordetella pertussis induces apoptosis in macrophages: role of adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4064–4071. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4064-4071.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kochi S K, Collier R J. DNA fragmentation and cytolysis in U937 cells treated with diphtheria toxin or other inhibitors of protein synthesis. Exp Cell Res. 1993;208:296–302. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuo C F, Wu J J, Lin K Y, Tsai P J, Lee S C, Jin Y T, Lei H Y, Lin Y S. Role of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B in the mouse model of group A streptococcal infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3931–3935. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3931-3935.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo C F, Wu J J, Tsai P J, Lei H Y, Lin M T, Lin Y S. Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B induces apoptosis and reduces phagocytic activity in U937 cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:126–130. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.126-130.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaPenta D, Rubens C, Chi E, Cleary P P. Group A streptococci efficiently invade human respiratory epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12115–12119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin Y S, Lei H Y, Low T L, Shen C L, Chou L J, Jan M S. In vivo induction of apoptosis in immature thymocytes by staphylococcal enterotoxin B. J Immunol. 1992;149:1156–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindgren S W, Heffron F. To sting or be stung: bacteria-induced apoptosis. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:263–264. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)88832-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindgren S W, Stojiljkovic I, Heffron F. Macrophage killing is an essential virulence mechanism of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4197–4201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukomski S, Streevatsan S, Amberg C, Reichardt W, Woischnik M, Podbielski A, Musser J M. Inactivation of Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease significantly decreases mouse lethality of serotype M3 and M49 strains. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:2574–2580. doi: 10.1172/JCI119445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menzies B E, Kourteva I. Internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by endothelial cells induces apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5994–5998. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5994-5998.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molinari G, Talay S R, Valentin-Weigand P, Rohde M, Chhatwal G S. The fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, SfbI, is involved in the internalization of group A streptococci by epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1357–1363. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1357-1363.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monack D M, Raupach B, Hromockyj A E, Falkow S. Salmonella typhimurium invasion induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9833–9838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Müller A, Hacker J, Brand B C. Evidence for apoptosis of human macrophage-like HL-60 cells by Legionella pneumophila infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4900–4906. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4900-4906.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musser J M, Hauser A R, Kim M H, Schlievert P M, Nelson K, Selander R K. Streptococcus pyogenes causing toxic-shock-like syndrome and other invasive diseases; clonal diversity and pyrogenic exotoxin expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2668–2672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patrick D, Betts J, Frey E A, Prameya R, Dorovini-Zis K, Finlay B B. Haemophilus influenzae lipopolysaccharide disrupts confluent monolayers of bovine brain endothelial cells via a serum-dependent cytotoxic pathway. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:865–872. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.5.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruckdeschel K, Roggenkamp A, Lafont V, Mangeat P, Heesemann J, Rouot B. Interaction of Yersinia enterocolitica with macrophages leads to macrophage cell death through apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4813–4821. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4813-4821.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savill J, Fadok V, Henson P, Haslett C. Phagocyte recognition of cells undergoing apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1993;14:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlievert P M, Assimacopoulos A P, Cleary P P. Severe invasive group A streptococcal disease: clinical description and mechanisms of pathogenesis. J Lab Clin Med. 1996;127:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(96)90161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens D L, Tanner M H, Winship J, Swarts R, Ries K M, Schlievert P M, Kaplan E. Severe group A streptococcal infections associated with a toxic shock-like syndrome and scarlet fever toxin A. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907063210101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai P J, Kuo C F, Lin K Y, Lin Y S, Lei H Y, Chen F F, Wang J R, Wu J J. Effect of group A streptococcal cysteine protease on invasion of epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1460–1466. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1460-1466.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolf B B, Gibson C A, Kapur V, Hussaini I M, Musser J M, Gonias S L. Proteolytically active streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B cleaves monocytic cell urokinase receptor and releases an active fragment of the receptor from the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30682–30687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wyllie A H, Morris R G, Smith A L, Dunlop D. Chromatin cleavage in apoptosis: association with condensed chromatin morphology and dependence on macromolecular synthesis. J Pathol. 1984;142:67–77. doi: 10.1002/path.1711420112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zychlinsky A, Sansonetti P J. Apoptosis as a proinflammatory event: what can we learn from bacteria-induced cell death? Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:201–204. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zychlinsky A, Prevost M C, Sansonetti P J. Shigella flexneri induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Nature. 1992;358:167–168. doi: 10.1038/358167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]