Abstract

Introduction

Since 2016, the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health has adopted a “Universal Test and Treat” strategy to treat human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). In this test and treat era, access to anti-retroviral therapy (ART) has been rapidly expanded. On the other hand, poor retention of patients on ART remains a serious concern for reaching ART program goals. Thus, this study is targeted at investigating the attrition rate and its predictors among HIV-positive adults following the implementation of the “test and treat” strategy in Ethiopia.

Methods

An institution-based retrospective follow-up study was conducted among 1048 HIV-positive adults receiving ART at public health institutions in Bahir Dar city, Northern Ethiopia. Data were extracted from randomly selected patient charts, entered into Epidata 4.6 and exported to Stata 14.2 for analysis. Kaplan-Meier curve was used to estimate individuals' attrition-free probability at each specific point in time. Both bivariable and multivariable cox regression models were fitted, and variables with a P-value of <0.05 in the multivariable model were considered as significant predictors of attrition.

Results

A total of 1020 (97.3%) study participants were included in the final analysis. The attrition rate of individuals was 15 per 100 person-years of observation (95% CI: 13.5–16.9 per 100 PYO). World Health organization (WHO) stage III/IV clinical diseases (Adjusted hazard ratio/AHR/1.75 (95% CI:1.24–2.48)), Not disclosing HIV-status (AHR 1.6 (95% CI: 1.24–2.05)), rapid initiation of ART (AHR 2.05 (95%CI:1.56–7.69)), No history of ART regime change (AHR2.03 (95% CI: 1.49–2.76)), “1J (TDF_3TC-DTG)” ART regimen (AHR 0.46 (95%CI: 2.18–3.65)), and Poor ART adherence (AHR2.82 (95%CI: 2.18–3.65)) were identified as significant predictors of attrition rate of HIV positive adults.

Conclusion

Following the implementation of the universal test and treat area, the attrition rate of adults living with (HIV) found to be high. Due attention shall be provided to those individuals who didn’t disclose their status, were initiated into ART within seven days, had WHO stage III/IV clinical disease, had poor adherence history, had no regimen change, and are not on 1J (TDF_3TC-DTG) ART regimen type.

Keywords: Attrition rate, Predictors, Test and treat era, Northern Ethiopia

Attrition rate; Predictors; Test and treat era; Northern Ethiopia.

1. Introduction

HIV remains one of the most serious global health threats. At the end of 2021, there were an estimated 38.4 million [33.9–43.8 million] HIV-positive individuals worldwide; of which 36.7 [32.3–41.9 million] were adults [1]. Despite the fact that the burden of the HIV epidemic continues to vary greatly between countries and regions, the WHO African Region remains the most severely affected, making up more than two-thirds of all HIV-positive people globally [1, 2]. To end HIV epidemics by 2030, the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) launched the three “95-95-95” targets for HIV/AIDS in 2014. These three “95-95-95” targets suggest that 95% of HIV-infected individuals should know their status, 95% of individuals who know their status should get access to anti-retro-viral therapy (ART), and 95% of individuals on ART should achieve viral suppression, respectively [3]. In this regard, access to ART has been rapidly expanded both nationally and globally, whereby nearly 28.2 million (74.8%) HIV-positive patients have been receiving it globally [1, 4]. Additionally, ART has shown impressive results in lowering new HIV infection as well as HIV/AIDS-related morbidity and mortality. According to the UNAIDS 2021 report, ART has shown a 32% and 52 % global reduction in the incidence of new HIV infection and HIV/AIDS-related mortality, respectively, since 2010 [4].

On top of the above, in 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the “Universal Test and Treat (UTT)” strategy to enhance the achievement of UNAIDS 2030 goals [5]. The universal test and treat strategy entirely focuses on rapid (within seven days) initiation of ART for all patients living with HIV/AIDS [5, 6, 7]. This strategy was proven to significantly contribute to the acceleration of viral load suppression, restoring immune function, improving quality of life, viral load reduction, and prevention of HIV/AIDS transmission [5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Though meeting the UNAIDS 2nd and 3rd targets demand early ART initiation, ensuring uninterrupted ART service and continuous engagement of patients is also essential for sustained viral suppression and optimal treatment outcome [8]. However, sub optimal adherence and high attrition rate due to either Loss to Follow-up (LTFU), documented death, or stopping ART remain a major public health concern [13]. A systematic review and meta-analysis report in low and middle-income countries revealed that only 65–70% of patients on ART were retained in HIV care at 36 months of initiation of ART [5]. Moreover, the findings of previous studies that investigated the incidence of attrition from ART following the implementation of the test and treat strategy were highly varied. For instance, research in Zimbabwe that looked at predictors of attrition before and after the “test and treat era” found that patients who enrolled in ART after the test and treat era had a 73% higher risk of attrition than their peers [14]. Additionally, Studies in Nigeria [15], Uganda [2, 14], Zimbabwe [16]and South Africa [17] revealed that rapid initiation of ART increases the incidence of attrition through enhancing early LTFU. In Nigeria and South Africa, nearly 34% and 33% of patients who commenced into ART under this era were immediately loss from their regular care [15, 17]. Inversely, in San-Francisco (USA) and Taiwan, the attrition of HIV-positive individuals did not significantly differ between same-day ART initiated and previous standard-based ART initiated HIV-positive patients [12, 18].

High attrition rate from ART is the leading cause of morbidity, mortality, hospitalization, increasing transmission rate, treatment failure, increasing burden of opportunistic infections (OIs), and the emergence of drug resistance HIV-virus (HIVDR) [13]. The main factors contributing to the increased rate of attrition were sex, age, marital status, HIV-disclosure status, lack of social support, functional status, nutritional status, having opportunistic infections, WHO clinical stage, substance abuse status, residence, cotrimoxazole prophylaxis (CPT), drug adherence level, type of ART regimen, and side effects of ART [2, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23].

In Ethiopia, the Universal Test and Treat strategy has been implemented since 2016 [8]. Since then, patients' access to ART has been rapidly expanded, and simultaneously, the mortality rate has been dramatically decreased [9]. However, sub-optimal drug adherence and early ART interruption remain major concerns till now. For instance, the attrition rate of HIV-positive adults receiving ART before the implementation of test and treat strategy at Woldia, Northeast Ethiopia, was 8.36 (95%CI:7.12–9.80) per 100 person-years of observation [22]. On top of that, though there is limited literature, an empirical evidence on the effectiveness of UTT revealed that the 12-month retention level of patients who initiated ART on the same day of diagnosis was significantly lower (75.8%) when compared with those with late after seven days of diagnosis (82%) [24]. Since UTT has begun to be implemented recently, there is a dearth of evidence that addresses the effect of rapid ART initiation on the attrition level of the patient on ART in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aims to assess the incidence of attrition and its predictors of HIV-positive adults receiving ART following the implementation of the test and treat strategy in public health institutions of Bahirdar city.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study design and period

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted among HIV-positive adults who were newly enrolled in ART at public health institutions in Bahir Dar City. The study period for this study was also from November 2016 to December 2021, so the study participants were tracked for a minimum of one month and a maximum of five years.

2.2. Study setting

This study was conducted at public health institutions in Bahir Dar City, Northern Ethiopia. The city is the site of the initial ART service center in Amhara Regional State, where it began offering ART service in 2003 and UTT since November 2016. Bahira Dar City is located 565 km northwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Currently, the city provides ART through 11 functional ART centers (two hospitals and nine health centers). Additionally, the city bears the highest burden of HIV/AIDS patient load in the region, whereby nearly 16,224 individuals were ever enrolled in ART service at those institutions. From the above figure, 3022 HIV-positive patients were newly initiated into ART after the implementation of the “universal treat-all” strategy.

2.3. Study participants

The source population for this study were all adults received ART following the implementation of the “Universal Test and Treat” strategy at public health institutions in Bahir Dar City. The study population were all adults newly initiated into ART from November 2016 to December 2021 at public health institutions in Bahir Dar city. People with an unknown HIV confirmation and ART initiation date, as well as an undefined outcome after their follow-up period, were excluded.

2.4. Sample size determination and sampling technique

The sample size required to conduct this study was calculated using the Log-rank test using STATA (V.14.2) software, comparing two survival rate sample size calculation option. The minimum sample size required for this study was 1048, which is obtained by taking parameters such as power (80%), confidence level (95%), type 1 error (0.05%), survival/event-free probability in the exposed group (76%), and survival/event-free probability in the control group (83%), and an adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) of 1.29, taken from a previous study conducted in Malawi [25]. Then, after taking the unique ART number of all study populations, a computer-generated random sampling method was utilized to select the final study units.

2.5. Study variables

The incidence of attrition rate at a certain point in time is the dependent variable for this study. On the other hand, socio_demographic characteristics (age, sex, level of education, marital status, occupation), baseline and follow-up clinical, immunological and treatment-related characteristics (baseline CD4 count, baseline WHO clinical stage, Baseline Body Mass Index status (BMI), baseline functional status presence of OIs), and behavior related factors (disclosure, adherence level) were considered as determinant factors of the outcome attrition rate.

2.6. Operational definitions

The variables listed below have been given operational definitions to make them easily measurable. “Time to ART initiation” is defined as the time interval stated in a day from the confirmation of HIV status till the patient’s enrollment into ART care. Rapid ART initiation is defined as commencing ART within seven days after confirmation of diagnosis, regardless of the patients WHO clinical staging or CD4+ cell count [5, 6, 8]. Patients were categorized as transferred out when they had a copy of a formal letter that indicated they had been transferred to another ART providing health institution [8]. Patients will be categorized as “retention in care” if they are alive and receiving lifelong ART at their initial ART enrollment site (this excludes patients who were documented as (LTFU), deceased, or transferred out) [6, 8, 21]. Attrition from ART care is the opposite of retention (1-retention), which includes death, LTFU, and undocumented transferred outpatients [8, 21]. The outcome of the patient is categorized as either event (when they develop attrition from ART) or censored (when patients didn’t develop the outcome at the end of the follow-up period). ART drug adherence was defined as the proportion of ART drug dosage taken correctly from a patient’s monthly dose and was graded as good, fair, or poor. As a result, the adherence level will be good if greater than or equal to 95% of the monthly doses are taken properly, fair if it is 85–95%, and poor if less than 85% of the monthly doses are taken correctly. The functional status of the patient is categorized as “working” if the daily activities of people living with HIV/AIDS were not altered due to illness, “ambulatory” if the patient was not fully working but was able to do minor tasks at home; and “bedridden” when the patient remained in bed most of the time [8]. BMI status was calculated by dividing body weight by height squared. It was classified as: normal weight (BMI: 18.5–24.99 kg/m2), under-weight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), and overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) [6,8].

2.7. Data collection instrument and procedures

The data abstraction tool was developed from the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) ART follow-up, the patient intake and monitoring formats. The data was collected by six BSc nurse professionals under the close supervision of two masters in public health professionals. To preserve the validity of data, a one-day training was given for both data collectors and supervisors about the objective of the study, the way to extract relevant data, and how to ensure the confidentiality of patient information.

2.8. Data processing and analysis procedures

Initially, the data were entered into Epi-data 4.6 software and then exported to STATA 14.0 software for cleaning, managing, and undertaking further statistical analysis. Multiple imputations were used to handle missing data using the Multi-variable Chained Equation (MVCE) method. Variables with more than 30% missing records (viral load, hemoglobin level) and that do not satisfy the missing at random assumption of multiple imputations were omitted from management. A sensitivity analysis was done to realize whether or not there had been a significant difference between the original and imputed data output, and no significant difference was observed. Continuous variables were summarized by either mean with standard deviation or median with inter-quartile range (IQR). Proportion was used to summarize categorical data. Tables and graphs were also used to present data. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to determine the attrition free (survival) probability of HIV-positive adults at each specific point in time. Where as, Log-rank test was used to compare attrition free probability between different categories of each explanatory variable.

Schoenfeld residual global proportional hazard (PH) test was used to assess the proportional hazard assumption of the cox-regression model. Besides, the goodness of fit for the final model was checked using the Cox-Snell residual plot. Both bi-variable and multi-variable cox regression models were fitted to identify significant predictors of attrition.

2.9. Ethical considerations

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Bahirdar University, College of Medicine and Health Science, issued an ethical approval with a protocol number 058/2021. Since the study used patient medical record (secondary data) as a source of information, consent from the patient is waived; in its place, a supportive letter was sent from the IRB to each public health institution in Bahirar Dar City. Then a permission letter that affirms the use of patients' charts as a source of information was obtained from the directors of those health institutions. During data collection and entry, patient identifiers (patient’s medical registration number (MRN)) were replaced by new codes. Similarly, the collected data was kept in a locked cabinet and on a computer with a strong password to safeguard its confidentiality.

3. Result

3.1. Results of socio-demographic variables

From a total of 1048 randomly selected HIV-positive people, 1020 (97.3%) were included in the final analysis. Females make up 534 (52.4%) of the participants. The study participants' median age was 32 years old, with an inter-quartile range (IQR 27–40 = 13). Regarding the residence of the study participants, more than two-thirds (734, 72%) were from urban areas, whereas more than one-fourth (272, 26.7 %) had not attended formal education. In addition, about 147 (29.3 %) of individuals were employed either in private or government organizations, followed by daily labourer (107, 20.3 %) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of HIV-positive adults receiving ART service following “Test and Treat strategy” in Bahir dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, November 2016 to December 2021.

| Variables (N = 1020) | Categories | Outcome status |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attrition | Censored | Frequency | % | ||

| Sex | Male | 158 | 328 | 486 | 47.6 |

| Female | 142 | 392 | 534 | 52.4 | |

| Age category | Age 15-24 | 71 | 77 | 148 | 14.5 |

| Age 25-34 | 119 | 314 | 433 | 42.6 | |

| Age 35-45 | 81 | 258 | 339 | 33.2 | |

| Age >45 | 29 | 71 | 100 | 9.8 | |

| Marital status | Married | 130 | 176 | 522 | 51.2 |

| Single | 91 | 177 | 235 | 23.0 | |

| Divorced | 67 | 206 | 219 | 21.5 | |

| Widowed | 12 | 161 | 44 | 4.3 | |

| Residence | Urban | 212 | 522 | 734 | 72.0 |

| Rural | 88 | 198 | 286 | 28.0 | |

| Educational status | No formal education | 93 | 162 | 272 | 26.7 |

| Primary education | 94 | 189 | 268 | 26.3 | |

| Secondary | 78 | 208 | 285 | 27.9 | |

| Tertiary and above | 35 | 161 | 195 | 19.1 | |

| Occupation | Daily-laborer | 74 | 122 | 196 | 19.2 |

| Farmer | 32 | 33 | 65 | 6.4 | |

| Merchant | 44 | 119 | 163 | 16.0 | |

| House-wife | 37 | 109 | 146 | 14.3 | |

| Employed | 70 | 240 | 310 | 30.4 | |

| Student | 14 | 36 | 50 | 4.9 | |

| Others | 29 | 61 | 90 | 8.8 | |

| HIV-Positive family member | Yes | 96 | 327 | 423 | 41.5 |

| No | 204 | 393 | 597 | 58.5 | |

Others: - includes individuals with jobs other than those mentioned (drivers, street adults).

Censored - when patients didn’t develop the outcome at the end of the follow-up period.

3.2. Results of clinical and treatment-related variables

Slightly more than half, 576 (56.5%) of study participants were enrolled into ART rapidly (with in seven days) of confirmation of HIV-diagnosis. Regarding the clinical profile, about 276 (27.1%) and 351 (34.5%) of them were underweight and on WHO stage III/IV clinical disease, respectively. In terms of ART regimen, the majority of them (70.9%) were on the 1e (TDF_3TC_EFV) ART regimen, and only one-fifth of them (25.98%) had ART regimen change history (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical, immunological and treatment-related characteristics of adults receiving ART following ‘Test and Treat strategy” in Bahir dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, November 2016 to December 2021.

| Variables (N= 1020) | Categories | Failure status |

Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Censored | ||||

| Time to ART initiation | Within 7 days | 203 | 373 | 576 | 56.5 |

| After 7 day | 97 | 347 | 444 | 43.5 | |

| baseline WHO clinical stage | Stage I and II | 178 | 491 | 669 | 65.5 |

| Stage III and IV | 122 | 229 | 351 | 34.5 | |

| baseline CD4 category | Greater than 500 | 62 | 157 | 219 | 21.3 |

| From 200 to 499 | 109 | 304 | 413 | 40.5 | |

| <200 | 129 | 259 | 398 | 38.2 | |

| Baseline BMI category | Underweight | 95 | 181 | 276 | 27.1 |

| Normal and/or overweight | 205 | 539 | 744 | 72.9 | |

| Functional status | Working | 224 | 570 | 794 | 77.8 |

| Ambulatory | 58 | 120 | 178 | 17.5 | |

| Bedridden | 18 | 30 | 48 | 4.7 | |

| History of TB/HIV co-infection | Yes | 68 | 143 | 215 | 21.1 |

| No | 232 | 577 | 805 | 78.9 | |

| History of OIs | Yes | 120 | 243 | 363 | 35.5 |

| No | 180 | 477 | 657 | 64.5 | |

| Baseline ART regimen | 1e (TDF_3TC_EFV) | 234 | 486 | 723 | 70.9 |

| 1j (TDF_3TC- DTG) | 29 | 167 | 193 | 18.9 | |

| Others | 37 | 67 | 104 | 10.2 | |

| History of treatment failure | Yes | 17 | 39 | 56 | 5.5 |

| No | 283 | 681 | 964 | 94.5 | |

| History of regimen change | Yes | 75 | 190 | 265 | 26 |

| No | 225 | 530 | 755 | 74 | |

| History of side effects | Yes | 49 | 39 | 88 | 8.6 |

| No | 251 | 681 | 932 | 91.4 | |

| CPT prophylaxis status | Received | 152 | 378 | 530 | 52 |

| Not-received | 148 | 342 | 490 | 48 | |

| IPT prophylaxis status | Received | 157 | 440 | 597 | 58.5 |

| Not_ received | 143 | 280 | 423 | 41.5 | |

Others:- include 1c(AZT-3TC-NVP), 1d(AZT-3TC-EFV), 1f(TDF-3TC-NVP).

ART - Anti-retroviral Therapy, CD4+ cells - Cluster of differentiation cells, CPT-Cotrimoxsazole preventive therapy, IPT- Isoniazid preventive therapy, OIs-opportunistic infections, TB - tuberculosis.

3.3. Result of behavioral characteristics

The majority of the study participants, 676 (66%), disclosed their status to at least one individual who provided necessary support to them. Besides, more than two-thirds of them, 359 (70%), had good adherence status (Table 3).

Table 3.

Behavioral characteristics of HIV-positive adults receiving ART service following “Test and Treat strategy” in Bahir dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, November 2016 to December 2021.

| Variables (N= 507) | Categories | Failure status |

Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Censored | ||||

| Disclosure status | Yes | 151 | 525 | 676 | 66.3 |

| No | 149 | 195 | 344 | 33.7 | |

| Adherence level | Poor/Fair | 150 | 141 | 291 | 28.5 |

| Good | 150 | 579 | 729 | 71.5 | |

Outcome status of the study participants.

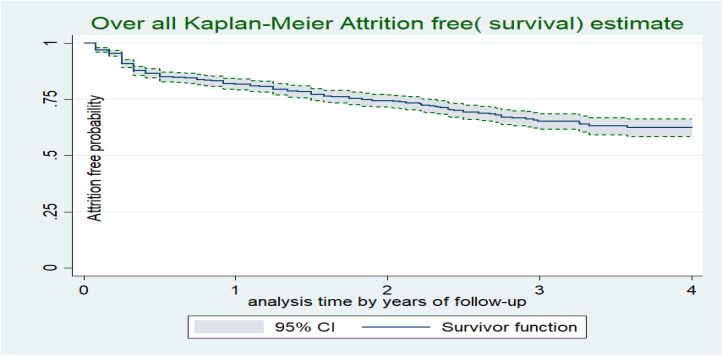

The study participants were followed for a minimum of one month to a maximum of sixty months, providing a total of 2008.79 PYO (24,105 persons-month of observation). The median follow-up time for the study participants was 25 months (IQR 11–36 month). Upon the compilation of the study period, about 300 (29.4%) individuals were not retained in ART care, resulting in an attrition rate of 15 per 100 PYO (95% CI: 13.5–16.9 per 100 PYO). The highest proportion of attrition rate is accounted by LTFU (62.3%), followed by undocumented transfer-out (29%) and death (8.7%). Though the attrition probability of study participants increases as follow up time increases, the highest attrition is observed in the first 06 months of follow up. For instance, the cumulative attrition free (survival) probability was 86.6% (95% CI: 84.3–88.5%) on the first six month, 81.9% % (95% CI; 79%–84%) at the end of twelve month, 70 % (95% CI; 67%–73%) at the end of two years, 76.6% a (95% CI:71.7%–80.7%) at the end of three years month, and 62 % (95%:57–66%) at the end of fifth year of follow-up period (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall attrition free probability of adults receiving ART following “Test and Treat strategy” in Bahir dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, November 2016 to December 2021.

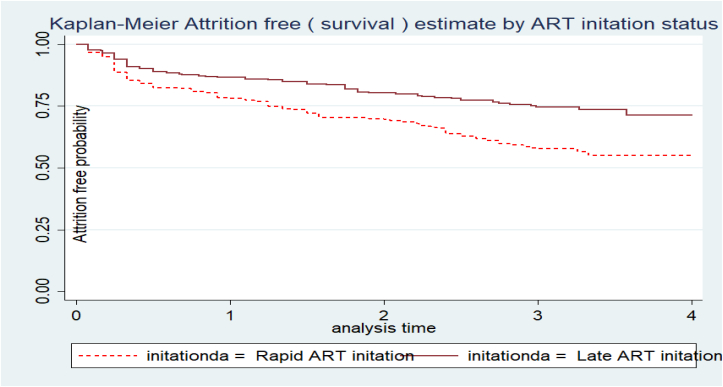

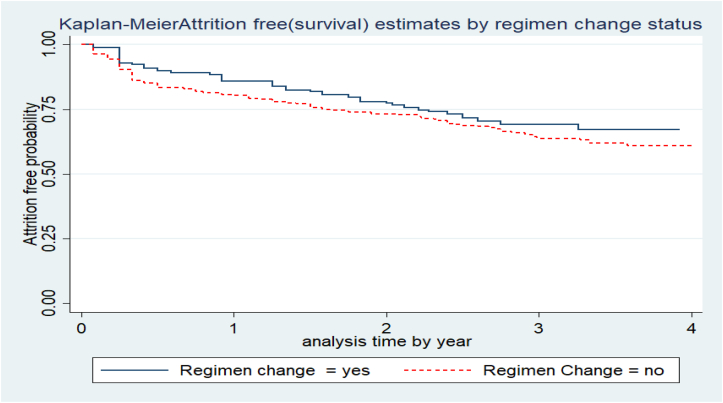

The attrition free probability of study participants differs considerably across various categories of predictors. For instance, the attrition free probability of patients who had no ART regimen change (34%, 95%CI: 27.7%–40%) was lower than those with ART regimen change throughout their ART care (39%, 95%CI: 34.6%–43.9%) (Figure 2). Similarly, those individuals who were initiated into ART rapidly had a higher attrition rate (46%, 95%CI: 40.6–51%) than those who were initiated after seven days of confirmation of diagnosis (27.3%, 95% CI: 22–33%) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Attrition free probability based on ART regimen-change status of adults receiving ART in Bahir dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, November 2016 to December 2021.

Figure 3.

Attrition free probability based on ART initiation time status of adults receiving ART in Bahir dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, November 2016 to December 2021.

3.4. Predictors of attrition rate

During bi-variable cox proportional regression analysis, nineteen variables with p-value < 0.20 were selected for multivariable logistic regression analysis. In the final analysis, the following five variables, namely ART disclosure, ART initiation time, level of adherence, initial ART regimen type, regimen change history, and WHO clinical staging, were obtained as a significant predictors of attrition rate. Hence, the hazard of attrition from ART care among WHO clinical stage III or IV individuals was 1.75 (95% CI: 1.24–2.48) times than their counterparts. HIV-positive adults who enrolled into ART within seven days were almost two times more at risk of attrition from their routine care than those who initiated later (AHR 2.05 (1.57–2.69)). Attrition rate of HIV-positive individuals who had fair/poor ART adherence was 2.82 times more than those who had good ART adherence (AHR 2.82, 95%CI 2.18–3.65). Those patients who had a history of ART regimen change were 2.03 (AHR, 2.03, 95%CI 1.49–2.76) times at risk of attrition from ART compared with their counterparts. Finally, the hazard of attrition from ART among individuals who disclose their status was 1.6 times higher than their counterparts (AHR 1.6, 95%CI 1.24–2.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bi-variable and Multi-variable Cox regression analysis result of predictors of Attrition rate among adults receiving ART in a “test and treat era” in Northwest Ethiopia, November 2016 to December 2021.

| Variables | Catagories | Outcome status |

CHR (95% CI) | AHR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Censored | ||||

| Sex | Male | 158 | 328 | 1.23 (0.98–1.54) | 1.21 (0.91–1.61) |

| Female | 142 | 392 | 1 | 1 | |

| Age category | Age 15-24 | 71 | 77 | 1.71 (1.11–2.64)∗ | 1.19 (0.67–2.11) |

| Age 25-34 | 119 | 314 | .85 (0.56–21.27) | .71 (0.42–1.18) | |

| Age 35-45 | 81 | 258 | .75 (0.49–1.14) | .65 (0.39–1.08) | |

| Age >45 | 29 | 71 | 1 | 1 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 130 | 176 | 1 | 1 |

| Single | 91 | 177 | 1.92 (1.47–2.51)∗ | 1.18 (0.85–1.64) | |

| Divorced | 67 | 206 | 1.24 (0.92–1.66) | 0.78 (0.56–1 .06) | |

| Widowed | 12 | 161 | 0.83 (0.46–1.50) | 0.62 (0.33–1.19) | |

| Educational status | No formal Education | 93 | 162 | 1.94 (1.32–2.87)∗ | 1.41 (0.88–2.28) |

| Primary education | 94 | 189 | 1.92 (1.31–2.86)∗ | 1.26 (0.79–2.02) | |

| Secondary | 78 | 208 | 2.13 (0.99–4.57) | 1.18 (0.75–1.87) | |

| Tertiary and above | 35 | 161 | 1 | 1 | |

| Occupation | Daily-laborer | 74 | 122 | 1 | 1 |

| Farmer | 32 | 33 | 1.33 (0.88 2.01) | 1.32 (0.84–2.08) | |

| Merchant | 44 | 119 | 0.42 (0.39–0.83)∗ | 0.72 (0.49–1.08) | |

| House-wife | 37 | 109 | 0.58 (0.4–0.88)∗ | 0.67 (0.43–1.05) | |

| Employed | 70 | 240 | 0.54 (0.39–0.75)∗ | 0.73 (0.49–1.10) | |

| Student | 14 | 36 | 0.72 (0.42–1.30) | 0.54 (0.23–1.06) | |

| Others | 29 | 61 | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) | 0.80 (0.5–1.30) | |

| HIV-positive family member | Yes | 96 | 327 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 204 | 393 | 1.57 (1.23–1.99)∗ | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) | |

| Time to ART initiation | Within 7day | 203 | 373 | 2.10 (1.67–2.64) ∗ | 2.05 (1.57–2.69)∗∗ |

| After 7 day | 97 | 347 | 1 | 1 | |

| Baseline WHO clinical stage | Stage I and II | 178 | 491 | 1 | 1 |

| Stage III and IV | 122 | 229 | 1.43 (1.14–1.80) | 1.75 (1.24–2.48)∗∗ | |

| Baseline CD4 category | Greater than 500 | 25 | 79 | 1 | 1 |

| From 200 to 499 | 41 | 172 | .84 (0.61–1.14) | 0.87 (0.63–1.23) | |

| <200 | 27 | 163 | 1.14 (0.84–1.55) | 1.24 (0.86–1.80) | |

| Baseline BMI category | Underweight | 95 | 181 | 1 | 1 |

| Normal and overweight | 205 | 539 | 1.23 (0.97–1.58) | 1.00 (0.76–1.33) | |

| History of TB/HIV co-infection | Yes | 68 | 143 | 1.14 (0.87–1.49) | 1.18 (0.83–1.69) |

| No | 232 | 577 | 1 | 1 | |

| History of OIs | Yes | 120 | 243 | 1.21 (0.97–1.53) | 1.13 (0.83–1.55) |

| No | 180 | 477 | 1 | 1 | |

| Disclosure | Yes | 151 | 525 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 149 | 195 | 3.26 (2.15–4.9)∗ | 1.6 (1.24–2.05)∗∗ | |

| History of Regimen Change | Yes | 75 | 190 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 225 | 530 | 1.23 (0.95–1.60) | 2.03 (1.49–2.76)∗∗ | |

| Baseline ART regimen | 1e (TDF_3TC_EFV) | 234 | 486 | 1 | 1 |

| 1j (TDF_3TC- DTG) | 29 | 167 | 0.66 (0.45–0.98)∗ | 0.46 (0.30–0.71)∗∗ | |

| Others | 37 | 67 | 1.22 (0.87–1.73) | 1.24 (0.86–1.80) | |

| IPT status | Received | 152 | 378 | 1 | 1 |

| not_ received | 148 | 342 | 1.34 (1.07–1.69)∗ | 1.16 (0.88–1.52) | |

| CPT status | Received | 157 | 440 | 1 | 1 |

| Not received | 143 | 280 | 1.08 (0.86–1.35) | 1.22 (0.93–1.60) | |

| Adherence level | Good | 150 | 579 | 1 | |

| Poor/fair | 150 | 141 | 3.28 (2.61–4.11)∗ | 2.82 (2.18–3.65)∗∗ | |

| History of drug side effect | Yes | 49 | 39 | 1.49 (1.06–2.07)∗ | 1.023 (0.68–1.55) |

| No | 251 | 681 | 1 | ||

1- Reference category, ∗ statistically significant at bi-variable with 5% level of significance, ∗∗ statistically significant at multivariable with 5% level of significance, CI- confidence interval.

Test of the assumption of Cox-regression analysis.

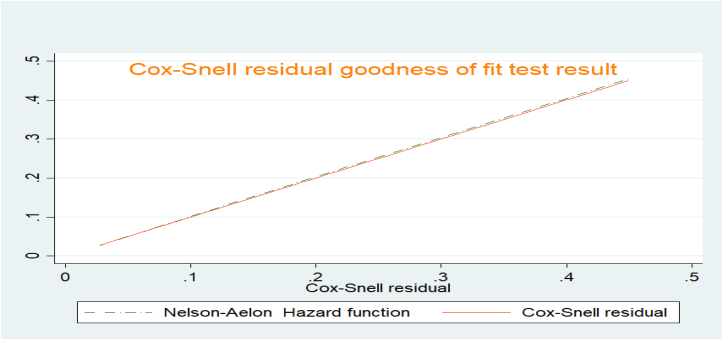

The proportional hazard assumption of the regression analysis was approved by using both graphical results (Log-Log survival probability plot) and statistical tests (Schönfeld residuals proportional hazard (PH) test). Both graphical and statistical methods assure that the proportional hazard assumption of the cox-regression model was satisfied (the P-value of the pH test is 0.108). The Cox-Snell residual plot was used to verify the goodness of fit of the Cox regression model. Based on the finding of the plot, the Cox–Snell residual plot follows the reference line tangentially (within a 45-degree alignment), which confirms that the model is good to fit the data (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cox-snell residual plot showing goodness fit of Cox-regression model among adults receiving ART in Bahir dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, November 2016 to December 2021.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the attrition rate and its predictors following the implementation of the “Universal Test and Treat strategy” in Bahir Dar city, Northern Ethiopia. The overall attrition rate of study participants in this study was 15 per 100 PYO (95 percent CI: 13.5–16.9 per 100 PYO), with the largest incidence occurring during the first six months of therapy. This figure is higher than the previous study undertaken in Ethiopia prior to the commencement of the test and treat era [22]. On the other hand, it is consistent with the previous research findings conducted in Zimbabwe following UTT [14, 16]. The likely explanation for this agreement could be the comparable socioeconomic status and HIV management protocol of the two countries, which indirectly increases the risk of early mortality and loss from ART treatment [26]. On the other hand, this finding is lower when compared with a study conducted between September 1, 2007 and September 1, 2014 at Karama hospital in the Somali region of Ethiopia [27]. The disparity in accessibility and coverage of ART service sites between these places could be the possible reason for the apparent discrepancy. Inadequate access to ART service sites in the Ethiopian Somali region relative to our study area makes the patient go a long distance to access it. In addition, the absence of permanent settlement and the migratory nature of the peoples in the Somali region lead patients on ART not to have regular follow-ups and prematurely die with HIV/AIDS [28].

In the current study, HIV positive adults with WHO stage III/IV clinical disease were nearly two times more at risk for attrition than those with stage I/II clinical disease. This report is in line with prior studies conducted at Debre markos referral hospital in Ethiopia, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria [2, 14, 15, 29]. The observed link could be explained by the fact that individuals with Stage III/IV clinical disease are more likely to die or become bedridden as a result of fatal opportunistic infections such as Cryptococcus meningitis, extra pulmonary TB, and other AIDS-defining disorders [30].

Furthermore, rapid ART initiation was found to be significantly associated with an increasing feature of attrition rate. Indeed, this finding was supported by previous research conducted in Zimbabwe and South Africa [14, 17]. The observed association could be explained by the fact that, because ART is a lifelong therapy, it requires intensive counseling, reassurance, and emotional readiness prior to starting it. In the pre-UTT era, patients were provided with a minimum of three counselling sessions to ensure adequate patient readiness and were retained on ART for the rest of their lives. In this regard, patients who begin ART treatment quickly may not have enough time to go through the aforementioned processes and prepare themselves for lifelong treatment programs. This finally ended up with the early loss of patients from the ART service.

Based on the current study, the adherence level of HIV positive adults was found to be a significant predictor of attrition from routine ART care. The attrition rates of individuals with poor clinical adherence levels were nearly three times greater than their counterparts. The observed finding is supported by research conducted in Woldiya town [22] and Nigeria [31]. Poor ART adherence in HIV-positive patients will result in treatment failure, increased viral load, increased incidence of drug-resistant HIV (DRHIV), opportunistic infections, and death [6, 8, 13]. Indeed, patients with poor drug adherence are more likely to be loss from their routine follow up, which in turn increases the attrition status of HIV positive individuals [32].

HIV positive individuals who are on the recently endorsed ART regimen called “1J (TDF+3TC + DTG)” were 54% less likely to develop attrition than those who are on “1E (TDF + TC + EFV)” ART regimen. This is because, according to the most recent ART guidelines, Deltugravi (DTG) has several advantages over nucleoside reverse transcriptase enzyme inhibitors (NNRTI), including faster viral suppression, faster CD4 cell count recovery, a higher genetic barrier against drug resistance, a lower risk of toxicity, and a lower potential for drug-drug interaction, which finally makes the patient feel well and keeps them on ART for an extended period [33]. This implies that timely regimen change and initiation of HIV positive patients with the latest recommended ART regimen type enhances patient retention.

Finally, the attrition rate of HIV positive patients was higher among HIV positive adults who didn’t disclose their status to at least one family than their counterparts. Prior studies conducted in the pre-UTT era also showed that not disclosing HIV status increases the loss to follow-up of patients on routine ART care [34, 35]. The possible explanation behind this might be due to the fact that individuals who didn’t disclose their status would not get enough social support from their family or the community, so they wouldn’t take their pills regularly without fear and have successful participation in their routine care [36, 37]. This suggests that patients will have a regular follow-up on ART when they get adequate support from their peers or family members.

4.1. Strength of the study

The main strength of this study is the use of relatively large sample size and including multiple health institutions, which will increase the precision of the estimate.

4.2. Limitation of the study

This study has some limitations that should be considered while interpreting its findings. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, we are unable to assess the relationship of some important factors, including viral load, Hemoglobin (Hgb) level, Organ function test, wealth level of the patient, healthcare provider, and institution-level parameters with the attrition status of HIV-positive patients. Secondly, classifying transferred-out patients as attrition may overestimate the research finding because those transferred patients may receive their care at the receiving institution properly.

5. Conclusion and recommendation

In this “Universal Test and Treat era”, the attrition rate of HIV positive adults was found to be high. Though the attrition rate of individuals increases as the follow-up period extends, the majority of them develop the event in the first year of ART initiation. The major factors that increase the attrition rate of HIV-positive patients were rapid ART initiation, being on WHO stage III/IV clinical diseases, not disclosing HIV status, having poor ART adherence, and not having a history of regimen change. On the other hand, being on 1J ART regimen (TDF-3T-GTD) decreases the likelihood of attrition of HIV-positive adults. As a result, we recommend stakeholders to enhance intense adherence counselling and ensure patients' readiness and commitment before initiating ART. Furthermore, future researchers are also encouraged to conduct prospective studies to investigate the relationship between the test-and-treat period and patient outcomes, particularly in low-income settings.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Berihun Bantie, MSc: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Moges Wubneh Abate, MSc; Adane Birhanu Nigat, MSc: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Tekalign Amera Birlie; Tadila Dires, MSc; Tigabu Minuye, MSc; Chalie Marew Tiruneh, MSc; Ermias Sisay Chanie, MSc; Dejen Getaneh Feleke, MSc; Animut Tilahun Mulu, MSc; Melsew Dagne Abate, MSc; Makda Abate; Biruk Demssie, MPH: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Gashaw Kerebeh, MSc; Natnael Moges, MSc: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Awoel Seid Ali; Getenet Dessie: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Tigabinesh Assfaw Fentie, MPH: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

The data that has been used is confidential.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Bahirdar University, College of Medicine and Health Science for allowing us to conduct this study and providing ethical clearance in a timely manner. Next, we want to express our gratitude to the employees at the ART clinic, card room, and management positions in selected public health institutions in Bahirdar town for creating an atmosphere that allowed us to collect the data we needed for this study. Last but not least, we would like to express our gratitude to the data collectors and supervisors for their willingness, dedication, and hard work during data collection for the benefit of this study.

References

- 1.World Health Orgainization (WHO) Health Topics, Summary of the Global HIV Epidemics. 2021. Avaliable on [ https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/hiv-aids.

- 2.United Nations Joint Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Global HIV & AIDS Statistics — Fact Sheet. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet Available on. Cited on [ April, 2022]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) 2016. Report on Early Warning Indicators of HIV Drug Resistance: Technical Report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiwanuka J., Waila J.M., Muhindo K.M., Kitonsa J., Kiwanuka N. Starting antiretroviral therapy within seven days of a positive HIV test increased the risk of loss to follow up in a primary healthcare clinic: a retrospective cohort study in Masaka, Uganda. bioRxiv. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mugavero M.J., Amico K.R., Westfall A.O., Crane H.M., Zinski A., Willig J.H., Dombrowski J.C., Norton W.E., Raper J.L., Kitahata M.M. Early retention in HIV care and viral load suppression: implications for a test and treat approach to HIV prevention. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. (1999) 2012;59(1):86. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318236f7d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiwanuka J., Mukulu Waila J., Muhindo Kahungu M., Kitonsa J., Kiwanuka N. Determinants of loss to follow-up among HIV positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a test and treat setting: a retrospective cohort study in Masaka, Uganda. PLoS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linn K.Z., Shewade H.D., Htet K.K.K., Maung T.M., Hone S., Oo H.N. Time to anti-retroviral therapy among people living with HIV enrolled into care in Myanmar: how prepared are we for ‘test and treat’? Glob. Health Action. 2018;11(1) doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1520473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onoya D., Hendrickson C., Sineke T., Maskew M., Long L., Bor J., Fox M.P. Attrition in HIV care following HIV diagnosis: a comparison of the pre-UTT and UTT eras in South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021;24(2) doi: 10.1002/jia2.25652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutini S., Cahyati W.H., Rahayu S.R. Socio-demographic factors associated with loss to follow up anti retro viral therapy among people living with HIV and AIDS in Semarang city. Publ. Health Perspect. J. 2020;5(3) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birhanu M.Y., Leshargie C.T., Alebel A., Wagnew F., Siferih M., Gebre T., Kibret G.D. Incidence and predictors of loss to follow-up among HIV-positive adults in northwest Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Trop. Med. Health. 2020;48(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s41182-020-00266-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappellini M.D., Motta I. Anemia in clinical practice-definition and classification: does hemoglobin change with aging? Semin. Hematol. 2015;52(4):261–269. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y.-C., Sun H.-Y., Chuang Y.-C., Huang Y.-S., Lin K.-Y., Huang S.-H., Chen G.-J., Luo Y.-Z., Wu P.-Y., Liu W.-C. Short-term outcomes of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive patients: real-world experience from a single-centre retrospective cohort in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown L.B., Havlir D.V., Ayieko J., Mwangwa F., Owaraganise A., Kwarisiima D., Jain V., Ruel T., Clark T., Chamie G. High levels of retention in care with streamlined care and universal test-and-treat in East Africa. AIDS (London, England) 2016;30(18):2855. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makurumidze R., Mutasa-Apollo T., Decroo T., Choto R.C., Takarinda K.C., Dzangare J., Lynen L., Van Damme W., Hakim J., Magure T. Retention and predictors of attrition among patients who started antiretroviral therapy in Zimbabwe’s national antiretroviral therapy programme between 2012 and 2015. PLoS One. 2020;15(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown L.B., Getahun M., Ayieko J., Kwarisiima D., Owaraganise A., Atukunda M., Olilo W., Clark T., Bukusi E.A., Cohen C.R. Factors predictive of successful retention in care among HIV-infected men in a universal test-and-treat setting in Uganda and Kenya: a mixed methods analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tlhajoane M., Dzamatira F., Kadzura N., Nyamukapa C., Eaton J.W., Gregson S. Incidence and predictors of attrition among patients receiving ART in eastern Zimbabwe before, and after the introduction of universal ‘treat-all’ policies: a competing risk analysis. PLOS Global Publ. Health. 2021;1(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joseph Davey D., Kehoe K., Serrao C., Prins M., Mkhize N., Hlophe K., Sejake S., Malone T. Same-day antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased loss to follow-up in South African public health facilities: a prospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with HIV. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020;23(6):e25529. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pilcher C.D., Ospina-Norvell C., Dasgupta A., Jones D., Hartogensis W., Torres S., et al. The effect of same-day observed initiation of antiretroviral therapy on HIV viral load and treatment outcomes in a US public health setting. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. (1999) 2017;74(1):44. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frijters E.M., Hermans L.E., Wensing A.M., Devillé W.L., Tempelman H.A., De Wit J.B. Risk factors for loss to follow-up from antiretroviral therapy programmes in low-income and middle-income countries. AIDS. 2020;34(9):1261–1288. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onoya D., Hendrickson C., Sineke T., Maskew M., Long L., Bor J., Fox M.P. Attrition in HIV care following HIV diagnosis: a comparison of the pre-UTT and UTT eras in South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021;24(2) doi: 10.1002/jia2.25652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray K.R., Dulli L.S., Ridgeway K., Dal Santo L., Darrow de Mora D., Olsen P., Silverstein H., McCarraher D.R. Improving retention in HIV care among adolescents and adults in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2017;12(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox M.P., Rosen S. Retention of adult patients on antiretroviral therapy in low- and middle income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis 2008-2013. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2015;69(1):98–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucciardini R., Fragola V., Abegaz T., Lucattini S., Halifom A., Tadesse E., Berhe M., Pugliese K., Fucili L., Di Gregorio M. Predictors of attrition from care at 2 years in a prospective cohort of HIV-infected adults in Tigray, Ethiopia. BMJ Global Health. 2017;2(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joseph Davey D., Kehoe K., Serrao C., Prins M., Mkhize N., Hlophe K., Sejake S., Malone T. Same-day antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased loss to follow-up in South African public health facilities: a prospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with HIV. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020;23(6):e25529. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alhaj M., Amberbir A., Singogo E., Banda V., van Lettow M., Matengeni A., Kawalazira G., Theu J., Jagriti M.R., Chan A.K. Retention on antiretroviral therapy during Universal Test and Treat implementation in Zomba district, Malawi: a retrospective cohort study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019;22(2) doi: 10.1002/jia2.25239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) List of low and middle income countries. https://wellcome.org/grant-funding/guidance/low-and-middle-income-countries

- 27.Seifu W., Ali W., Meresa B. Predictors of loss to follow up among adult clients attending antiretroviral treatment at Karamara general hospital, Jigjiga town, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Y.C., Sun H.Y., Chuang Y.C., Huang Y.S., Lin K.Y., Huang S.H., Chen G.J., Luo Y.Z., Wu P.Y., Liu W.C., Hung C.C. Short-term outcomes of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive patients: real-world experience from a single-centre retrospective cohort in Taiwan. BMJ Open. 2019 Sep 1;9(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United Nations Joint Program On HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) UNAIDS data. 2020. https://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/resource/unaids-2020-aids-data-book.pdf

- 30.World Health Organization (WHO) 2017. Guidelines for Managing Advanced HIV Disease and Rapid Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy, July 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makurumidze R., Buyze J., Decroo T., Lynen L., de Rooij M., Mataranyika T., et al. Patient-mix, programmatic characteristics, retention and predictors of attrition among patients starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) before and after the implementation of HIV “Treat All” in Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nabukeera-Barungi N., Elyanu P., Asire B., Katureebe C., Lukabwe I., Namusoke E., Musinguzi J., Atuyambe L., Tumwesigye N. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and retention in care for adolescents living with HIV from 10 districts in Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015;15(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pilcher C.D., Ospina-Norvell C., Dasgupta A., Jones D., Hartogensis W., Torres S., et al. The effect of same-day observed initiation of antiretroviral therapy on HIV viral load and treatment outcomes in a US public health setting. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. (1999) 2017;74(1):44. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seifu W., Ali W., Meresa B. Predictors of loss to follow up among adult clients attending antiretroviral treatment at Karamara general hospital, Jigjiga town, Eastern Ethiopia, 2015: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Govere S.M., Kalinda C., Chimbari M.J. Factors influencing rapid antiretroviral therapy initiation at four eThekwini clinics, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03530-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waddell E.N., Messeri P.A. Social support, disclosure, and use of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zürcher K., Mooser A., Anderegg N., Tymejczyk O., Couvillon M.J., Nash D., Egger M., IeDEA and MESH consortia Outcomes of HIV-positive patients lost to follow-up in African treatment programmes. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2017;22(4):375–387. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.