Abstract

Maternal-placental perfusion can be temporarily compromised by Braxton Hicks (BH) uterine contractions. Although prior studies have employed T2* changes to investigate the effect of BH contractions on placental oxygen, the effect of these contractions on the fetus has not been fully characterized. We investigated the effect of BH contractions on quantitative fetal organ T2* across gestation together with the birth information. We observed a slight but significant decrease in fetal brain and liver T2* during contractions.

Keywords: Placental MRI, T2* mapping, fetal organ T2*, Placental T2*, Braxton-Hicks contraction

Introduction

Robust placental function is essential for fetal development and for fetal health during the delivery process. A few earlier human studies demonstrated decreased blood flow in the intervillous space during uterine contractions induced by oxytocin infusion, which amplifies uterine contractions [1,2]. Maternal-placental perfusion can also be temporarily decreased by less intense, spontaneous Braxton Hicks (BH) uterine contractions, which occur throughout pregnancy as shown in rhesus macaques [3] and human studies [4,5]. In fact, Doppler ultrasound studies during BH contractions have shown increased resistance to blood flow in the uteroplacental circulation consistent with reduced maternal inflow [4,5]. This reduced inflow limits placental gas exchange, leading to falling oxygen partial pressures [6] and potential decreased oxygen supply to the fetus. Although no long-term disruption of placental function is expected for normally growing fetuses [7], the phenomenon is important to understand because pregnancies complicated by poor baseline placental function could result in sustained oxygen deprivation to the fetus [5,7]. T2*, measured with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is related to deoxygenated hemoglobin concentration with decreases in T2* corresponding to decreasing oxygenation. Prior MRI studies have shown that BH contractions cause transient decreases in placental T2*, consistent with decreased maternal oxygen supply [8,9]. However, it is unknown if these decreases in placental oxygenation are associated with transient decreases in fetal organ oxygenation in healthy pregnancies. We investigated the change in fetal brain and liver T2* during decreases in placental T2* caused by BH contractions.

Methods

We consented 38 pregnant people (29 normal singleton pregnancies and 9 at higher risk for preeclampsia) between 24 and 38 weeks of gestation. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Boston Children’s Hospital.

Scans were performed on a 3T Skyra scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) while subjects were in the left lateral position. We collected imaging time series (gradient echo - echo planar imaging, TR=4.2s, no breath-hold, multi-echo TE=18.0, 46.82, 75.64ms, in-plane resolution of 3mm×3mm, slice thickness of 3mm, 70 slices, GRAPPA 2, SMS 2) during normoxia (room air) for 5 min.

After signal non-uniformities and motion correction[10], T2* maps were generated by fitting a mono-exponential decay model to the measured intensities and their corresponding echo times. Regions of interest for the uterus, placenta, fetal brain and fetal liver were manually delineated in the reference frame using ITK-SNAP[11]. To estimate uterine volume change, voxel-wise deformation was quantified by computing the determinant of the Jacobian of the transformation generated during inter-volume motion correction. Overall volume change was calculated as a percentage change using average voxel-wise deformations in the uterus over time. To identify decreases in placental T2* associated with contractions, we selected placental T2* decreases occurring simultaneous with more than 4% decrease in entire uterine volume. For these subjects, average T2* in the placenta and fetal organs were computed for two different periods: 1. period without T2* drop (T2*n); 2. period when the deepest T2* drop was observed (T2*c). The change in T2* between period 1 and 2 was computed as (T2*n-T2*c)/T2*n. Student’s one sample t-test (mean change ± standard error) was used to evaluate, separately for each organ, the hypothesis that the mean change in T2* between period 1 and period 2 in that organ was zero. Linear mixed model analysis with restricted maximum likelihood method was used to examine the relationship of the change in T2* to GA at the time of imaging (GAi), and fetal birth weight percentile (BWtile). A separate model was used to examine the relationship of the change in T2* to GAi, GA at the time of delivery (GAd), and fetal birth weight (BW). In this model, the interaction effect of GAd and BW was also included into the model. The uterine volume change was added as a fixed variable in both models. Analyses were performed in Matlab®9.2 (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA).

Results

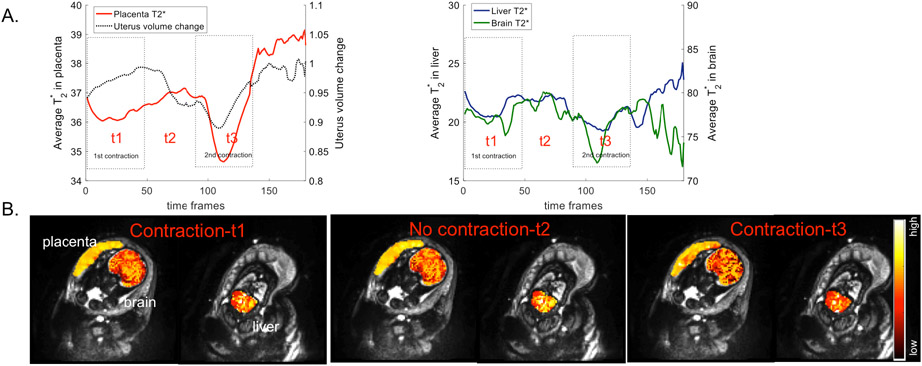

Four datasets were discarded due to artifacts. Data for the remaining 34 subjects were successfully analyzed. Placental T2* decreases occurred with contractions in 12 out of 34 subjects. We performed statistical analysis for 11 out of 12 with available GAd, BW and BWtile. Fig. 1 demonstrates the change in average T2* in the placenta, fetal brain and fetal liver, and the change in the uterine volume over time for a representative subject (Fig. 1A) together with T2* maps at the selected time points during contraction and no contraction periods (Fig. 1B). We observed significant decreases in placental T2* (p≤0.0022), and slight but significant decreases in fetal brain (p≤0.043) and liver T2* (p≤0.05) during contractions for all 11 subjects.

Figure 1.

A. The change in average T2* in the placenta (red), fetal brain (green) and fetal liver (blue), and the change in the uterine volume (black) over time for a representative subject. B. Single slice view of T2* maps in the placenta, fetal brain and liver at the selected time points during contraction (t1, t3) and no contraction (t2) periods for the same subject.

Table 1 summarizes the results of mixed model analysis. For the placentas, there was no significant correlation between the change in T2* and GAi. Although we observed a negative correlation between the change in placental T2* and both GAd and BW (p=0.0004, and p=0.001, respectively), there was no correlation between the change in placental T2* and BWtile. Adding uterine volume change as a fixed variable did not improve any of the correlations. We observed no significant correlation between fetal brain and liver T2* change and GAi, GAd, BW or BWtile with or without adjusting for uterine volume change.

Table 1:

The results of mixed model analysis

| Response variable |

Fixed effect coefficients (estimate±SE) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | GAi (weeks) |

GAd (weeks) |

BW (kg) | GAd:BW | BWtile | Uterine volume change |

||

| Placenta | T2* change | 15.4±2.3, p=0.0004 | −0.004±0.002 p=0.1 | −0.39±0.05, p=0.0004 | 4.28±0.73, p=0.001 | 0.11±0.02, p=0.0009 | - | - |

| T2* change | 15.6±2.2, p=0.0009 | −0.007±0.003 p=0.08 | −0.39±0.05, p=0.0009 | 4.52±0.75, p=0.0017 | 0.11±0.02, p=0.0015 | - | 0.67±0.6, p=0.31 | |

| T2* change | 0.14±0.23, p=0.55 | −0.002±0.007 p=0.77 | - | - | - | 0.0015±0.001 p=0.22 | - | |

| T2* change | 0.32±0.29, p=0.29 | −0.003±0.007 p=0.63 | - | - | - | 0.0002±0.001p=0.9 | −1.1±1.05 p=0.33 | |

| Fetal Brain | T2* change | 0.21±6.4, p=0.97 | 0.002±0.007 p=0.75 | −0.007±0.16 p=0.96 | 0.079±2.06 p=0.97 | 0.002±0.05 p=0.96 | - | - |

| T2* change | 0.33±6.99 p=0.96 | 0.001±0.01 p=0.92 | −0.004±0.17 p=0.98 | −0.22±2.3 p=0.92 | 0.005±0.05 p=0.93 | −0.4±1.89 p=0.84 | ||

| T2* change | 0.015±0.19 p=0.93 | 0.002±0.005 p=0.69 | - | - | - | 0.0003±0.001 p=0.72 | - | |

| T2* change | 0.037±0.26 p=0.88 | 0.002±0.006 p=0.73 | - | - | - | 0.0001±0.001 p=0.9 | −0.13±0.94 p=0.89 | |

| Fetal Liver | T2* change | −6.46±7.67 p=0.43 | 0.001±0.008 p=0.87 | 0.16±0.19 p=0.44 | 2.24±2.47 p=0.39 | 0.05±0.06 p=0.42 | - | - |

| T2* change | −6.16±8.25 p=0.48 | −0.002±0.011 p=0.87 | 0.16±0.2 p=0.46 | 1.88±2.76 p=0.52 | 0.047±0.06 p=0.51 | - | 1.03±2.24 p=0.66 | |

| T2* change | 0.1±0.24 p=0.67 | −0.003±0.007 p=0.77 | - | - | - | 0.001±0.001 p=0.31 | - | |

| T2* change | 0.21±0.32p=0.53 | −0.003±0.008 p=0.7 | - | - | - | 0.0005±0.002 p=0.79 | 0.64±1.19 p=0.6 | |

Discussion and Conclusion

We report the new observation of decreases in fetal brain and liver T2* with BH related decreases in placental T2*. Because the T2* signal corresponds to the relative amount of oxygenated hemoglobin, together these observations demonstrate that BH contractions are associated with transient decreases in placental oxygenation and corresponding transient decreases in fetal brain and liver oxygenation.

This preliminary report has several limitations. First, our sample size and healthy cohort limited our ability to explore relationships between birth weight percentile and contraction associated changes in T2*. T2* mapping for fetal organs was limited by the fetal motion, which was more severe than placental motion. T2* curve fitting was also affected by the inherently low signal from the fetal liver. A larger and more diverse cohort is necessary to better understand the contributions of BH contractions to fetal and placental oxygenation throughout gestation and with placental pathology.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that decreased placental T2* during BH contractions was associated with significant decreases in fetal organ T2*. Future work will focus on optimizing T2* mapping for fetal liver, developing better methods to detect and characterize regional volume change in the uterus during contractions and exploring T2* changes in placental pathologies such as intrauterine growth restriction and pre-eclampsia.

Grant Support

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health (grant numbers: R21 HD106553, R01HD100009, R01EB032708, P41EB015902.)

References

- [1].Borell U, Fernstroem I, Ohlson L, Wiqvist N, INFLUENCE OF UTERINE CONTRACTIONS ON THE UTEROPLACENTAL BLOOD FLOW AT TERM, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 93 (1965) 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Borell U, Fernstroem I, Ohlson L, Wiqvist N, EFFECT OF UTERINE CONTRACTIONS ON THE HUMAN UTEROPLACENTAL BLOOD CIRCULATION: AN ARTERIOGRAPHIC STUDY, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 89 (1964) 881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ramsey EM, Corner GW Jr, Donner MW, Serial and cineradioangiographic visualization of maternal circulation in the primate (hemochorial) placenta, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 86 (1963) 213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oosterhof H, Dijkstra K, Aarnoudse JG, Uteroplacental Doppler velocimetry during Braxton Hicks’ contractions, Gynecol. Obstet. Invest 34 (1992) 155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bower S, Campbell S, Vyas S, McGirr C, Braxton-Hicks contractions can alter uteroplacental perfusion, Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol 1 (1991) 46–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sletten J, Kiserud T, Kessler J, Effect of uterine contractions on fetal heart rate in pregnancy: a prospective observational study, Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand 95 (2016) 1129–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Olofsson P, Thuring-Jönsson A, Marsál K, Uterine and umbilical circulation during the oxytocin challenge test, Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol 8 (1996) 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sinding M, Peters DA, Frøkjær JB, Christiansen OB, Uldbjerg N, Sørensen A, Reduced placental oxygenation during subclinical uterine contractions as assessed by BOLD MRI, Placenta. 39 (2016) 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Abaci Turk E, Abulnaga SM, Luo J, Stout JN, Feldman HA, Turk A, Gagoski B, Wald LL, Adalsteinsson E, Roberts DJ, Bibbo C, Robinson JN, Golland P, Grant PE, Barth WH Jr, Placental MRI: Effect of maternal position and uterine contractions on placental BOLD MRI measurements, Placenta. 95 (2020) 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Abaci Turk E, Yetisir F, Adalsteinsson E, Gagoski B, Guerin B, Grant PE, Wald LL, Individual variation in simulated fetal SAR assessed in multiple body models, Magn. Reson. Med 83 (2020) 1418–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, Smith RG, Ho S, Gee JC, Gerig G, Userguided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability, Neuroimage. 31 (2006) 1116–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]