Abstract

We suggest here that Porphyromonas gingivalis DNA may function as a virulence factor in periodontal disease through expression of inflammatory cytokine. The bacterial DNA markedly stimulated in a dose-dependent manner interleukin-6 (IL-6) production by human gingival fibroblasts. The stimulatory action was eliminated by treatment with DNase but not RNase. The stimulatory effect was not observed in the fibroblasts treated with eucaryotic DNAs. The bacterial DNA also stimulated in dose- and treatment time-dependent manners the expression of the IL-6 gene in the cells. In addition, the stimulatory effect was eliminated when the DNA was methylated with CpG motif methylase. Interestingly, a 30-base synthetic oligonucleotide containing the palindromic motif GACGTC could stimulate expression of the IL-6 gene and production of its protein in the cells. Furthermore, the synthetic oligonucleotide-induced expression of this cytokine gene was blocked by pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate and N-acetyl-l-cystine, potent inhibitors of transcriptional factor NF-κB. Gel mobility shift assay showed increased binding of NF-κB to its consensus sequence in the synthetic oligonucleotide-treated cells. Also, using specific antibody against p50 and p65, which compose NF-κB, we showed the consensus sequence-binding proteins to be NF-κB. These results are the first to demonstrate that the internal CpG motifs in P. gingivalis DNA stimulate IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts via stimulation of NF-κB.

Recent studies (8, 11, 17, 21, 31, 34–36, 38, 43, 45, 46) have shown that gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial DNAs are potent stimulators of several inflammatory cytokines both in vivo and in vitro. Interesting studies (34, 35) actually showed in a mouse system that bacterial DNA caused toxic shock by a tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-dependent mechanism. Schwartz et al. (31) also observed that bacterial DNA-induced cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), TNF-α, and macrophage inhibitory protein 2 may play a functional role in lung inflammation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected patients with cystic fibrosis. These observations propose that bacterial DNA may function as a virulence factor of pathogenic bacteria via induction of such cytokines.

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a predominant pathogenic bacterium in periodontal disease (10), an infection characterized by inflammation and destruction of periodontal tissues. Many studies (12–16, 33, 39, 41, 42, 44) have suggested that inflammatory cytokines triggered following this bacterial infection play central roles in the pathogenic mechanism(s) operative in diseases of periodontal tissues. Therefore, it is of interest to examine whether P. gingivalis DNA can stimulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines by human gingival fibroblasts, because it has not yet been demonstrated whether human fibroblasts are DNA-responsive cells, though macrophages, NK cells, and B cells have been shown to respond to bacterial DNA (2, 8, 11, 17–19, 21, 28, 31, 34–36, 38, 43, 45, 46).

In the present study, therefore, we examined whether P. gingivalis DNA can induce IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts. Interestingly, we observed that the bacterial DNA stimulates cytokine expression in gingival fibroblasts through its internal CpG motifs. This observation demonstrates that human fibroblasts are cells responsive to bacterial DNA and suggests that P. gingivalis DNA may play a functional role in the pathogenic mechanism of the organism in periodontal disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Alpha minimal essential medium (α-MEM) was obtained from Flow Laboratories (McLean, Va.), and fetal calf serum was purchased from HyClone (Logan, Utah). [α-32P]dCTP and the megaprimed DNA labeling system were from Amersham Japan (Tokyo, Japan). DNase was obtained from Promega (Madison, Wis.). CpG methylase was from New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, Mass.). Salmon DNA, RNase, pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), and N-acetyl-l-cystine (NAC) were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). H-7 was obtained from Seikagaku Kougyou (Tokyo, Japan). Specific antibodies for p65 and p50 were purchased from Serotec Ltd. (Oxford, England) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif.), respectively.

Preparation of P. gingivalis DNA.

Chromosome DNA of P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 or 381 was prepared and purified by the method of Marmur (23). Briefly, each crude DNA was treated with RNase and proteinase K and extracted 10 times with phenol-chloroform. Then each DNA was precipitated with ethanol, treated with 70% ethanol five times, and finally dissolved in H2O. The DNA content was measured at an optical density of 260 nm with a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Each DNA contained less than 2.5 ng of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/mg of DNA by the Limulus amebocyte assay.

Methylation of P. gingivalis DNA.

The DNA was methylated for 18 h at 37°C with 2 U of CpG methylase per μg of DNA as described previously (2). The methylated DNA was tested to confirm that it was completely protected against digestion with HpaII but not MspI.

Preparation of DNA from eucaryotic cells.

Human and mouse chromosomal DNAs were prepared and purified from human monocytic cell line THP-1 cells and mouse osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1 cells by the same method as used for the preparation of bacterial DNA as described above.

Preparation of human gingival fibroblasts.

Human gingival tissues were cultured in Falcon 30-mm-diameter plastic plates in α-MEM containing 10% fetal calf serum under an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. The medium was changed every 6 days. After a confluent monolayer of cells that had migrated from the gingival tissues had formed, the cells were trypsinized and again grown to confluence. After the fifth passage, typical gingival fibroblasts were harvested and used in this study. The subconfluent gingival fibroblasts on plastic plates with α-MEM were cultured for various times with or without the desired dose of P. gingivalis DNA.

Measurement of IL-6 by human gingival fibroblasts.

The cells were cultured in Falcon 24-well culture plates until a subconfluent monolayer had formed and were then washed with serum-free α-MEM. Next, the cells were either not treated or treated with test samples at various concentrations. The culture supernatants were harvested 24 h later and measured for IL-6 protein with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit utilizing anti-human IL-6 antibody (Genzyme, Cambridge, Mass.).

cDNA hybridization probe.

A plasmid containing human IL-6 cDNA sequences was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.). Also, a plasmid bearing β-actin cDNA was from the Japanese Cell Resource Bank (Tokyo, Japan). The methods used for plasmid preparation were described earlier (22).

Preparation of total RNA and Northern blot analysis.

Subconfluent monolayers were incubated in the presence or absence of test samples at various concentrations and then washed five times with serum-free α-MEM. Thereafter, total RNA was extracted, and expression of the IL-6 gene in the cells was analyzed by the Northern blot assay as described previously (40, 41). β-Actin was used as an internal standard for the quantification of total mRNA on each lane of the gel.

Oligonucleotides.

GAC-30 (5′-ACCGAT-GACGTC-GCCGGT-GACGGC-ACCACG-3′), AGT-30 (5′-ACCGAT-AGTACT-GCCGGT-GACGGC-ACCACG-3′), GAG-30 (5′-ACCGAT-GAGCTC-GCCGGT-GACGGC-ACCACG-3′), and methylated GAC-30 (5′-ACCGAT-GAZGTC-GCCGGT-GACGGC-ACCACG-3′; Z indicates methylcytosine) oligodeoxynucleotides were obtained from Nippon Flour Mills Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of nuclear extracts.

Confluent monolayers in 15-cm-diameter dishes were either not treated or treated with test samples as indicated in the figure legends; their nuclei were then isolated, and the extracts were prepared as described previously (7, 44). Protein concentration was measured by the method of Bradford (6).

Gel mobility shift assay.

The assay was carried out as described previously (7, 44). Briefly, binding reactions were performed with 20 μg of sample protein in 2 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–8 mM NaCl–0.2 mM EDTA–0.8% (vol/vol) glycerol–0.2 mM dithiothreitol–1 μg of poly(dI-dC)–20,000 cpm of a 32P-labeled NF-κB oligonucleotide in a final volume of 20 μl for 20 min at room temperature. Poly(dI-dC) and nuclear extracts were incubated for 10 min on ice before addition of the labeling oligonucleotide. The double-stranded oligonucleotide containing a tandem repeat of the consensus sequence for the binding site -GGGGACTTTCC- for NF-κB was end labeled by the T4 polynucleotide kinase-[γ-32P]ATP method. The unlabeled double-stranded oligonucleotide was used as a competitor.

In some experiments, after addition of specific antibodies for p65 or p50, the reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min on ice.

DNA-protein complexes were electrophoresed on native 5% polyacrylamide gels in 0.25× TBE buffer (22 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 22 mM boric acid, 0.6 mM EDTA). Gels were vacuumed, dried, and exposed to Kodak X-ray film at −70°C.

RESULTS

Stimulatory effect of P. gingivalis DNA on IL-6 production by human gingival fibroblasts.

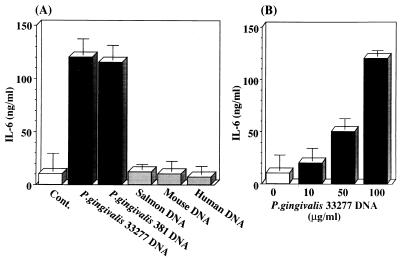

Since it was not known whether bacterial DNA can stimulate cytokine production by human fibroblasts, we examined the stimulatory effect of P. gingivalis DNA on IL-6 production by human gingival fibroblasts. The cells were not treated or treated with P. gingivalis DNAs or eucaryotic DNAs, and then IL-6 in the culture supernatant was measured at 24 h after the start of treatment. As shown in Fig. 1A, chromosomal DNAs derived from two strains (ATCC 33277 and 381) of P. gingivalis stimulated markedly IL-6 production by the cells. However, as we expected, the eucaryotic DNAs tested were unable to stimulate cytokine production. Also, as shown in Fig. 1B, the stimulatory effect of P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 DNA was dose dependent. These data show that P. gingivalis DNA is able to stimulate IL-6 production by human gingival fibroblasts.

FIG. 1.

Stimulatory effect of P. gingivalis DNA on IL-6 production in human gingival fibroblasts. Human gingival fibroblasts were cultured in Falcon 24-well culture plates until subconfluent monolayers had formed, then washed and incubated in serum-free α-MEM, and washed again 24 h later. (A) The cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 100 μg of P. gingivalis DNA or eucaryotic DNA per ml. The culture supernatants were harvested 24 h later, and then IL-6 was measured with an ELISA kit. (B) Confluent monolayers were cultured in serum-free α-MEM supplemented or not with various doses of P. gingivalis 33277 DNA. The culture supernatant was harvested 24 h later and then measured for IL-6 with the ELISA kit as described in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations for triplicate cultures. Cont., control.

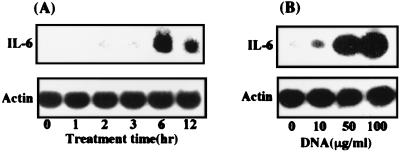

P. gingivalis DNA stimulates expression of the IL-6 gene in human gingival fibroblasts.

Next, using the Northern blot assay, we examined expression of the IL-6 gene in human gingival fibroblasts treated with P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 DNA. The cells were incubated for the desired times in the presence or absence of the bacterial DNA. Figure 2A shows the kinetics of expression of IL-6 mRNA in the bacterial DNA-treated cells. The DNA induced peak expression of the gene in the cells at 6 h after the start of treatment. We also observed that the DNA stimulation of IL-6 gene expression in the cells was dose dependent (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

P. gingivalis DNA stimulates expression of the IL-6 gene in human gingival fibroblasts. Human gingival fibroblasts were cultured in Falcon 10-cm-diameter culture dishes until subconfluent monolayers had formed, then washed and incubated in serum-free α-MEM, and washed again 24 h later. (A) The cells were treated or not with P. gingivalis 33277 DNA at 100 μg/ml for the times indicated, and then total RNA was prepared. (B) Confluent monolayers were treated or not with P. gingivalis 33277 DNA at various doses, and then total RNA was prepared at 6 h after the initiation of treatment. Northern blot analysis was performed with mouse IL-6 and β-actin cDNAs used as probes. An identical experiment independently performed gave similar results.

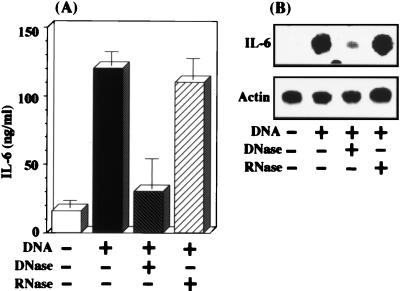

P. gingivalis DNA-stimulated IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts is eliminated by DNase treatment.

To define the stimulatory action of P. gingivalis DNA on IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts, we examined whether the stimulatory activity of the DNA could be eliminated by digesting the DNA with DNase. The cells were not treated or treated with bacterial DNA that had been digested or not for 3 h with DNase at 10 U/ml. We observed that DNA stimulation of IL-6 production by the cells was eliminated completely when the DNA was digested with DNase but not with RNase (Fig. 3A). In addition, the DNA-stimulated expression of the IL-6 gene in the cells was also eliminated by digestion with DNase but not RNase (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

P. gingivalis DNA-stimulated IL-6 expression in the fibroblasts is eliminated by DNase treatment. Confluent fibroblast monolayers were treated or not with P. gingivalis 33277 DNA (100 μg/ml) that had been pretreated or not with DNase (10 U) or RNase (10 μg). (A) The culture media were harvested at 24 h after the initiation of DNA treatment and then measured for IL-6 by use of the ELISA kit. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations for triplicate cultures. (B) Total RNA was prepared at 6 h after the initiation of DNA treatment. Northern blot analysis was performed with mouse IL-6 and β-actin cDNAs used as probes. An identical experiment independently performed gave similar results.

On the other hand, contamination by LPS was not involved in the DNA stimulation of IL-6 expression in the cells, because the stimulatory action was not affected by pretreating the DNA with polymyxin B, a potent inhibitor of LPS (data not shown); moreover, the LPS level in the DNA preparation was far below that required to cause a significant cellular response. Together with data described above, these results demonstrate that P. gingivalis DNA is a potent stimulator of IL-6 expression in gingival fibroblasts.

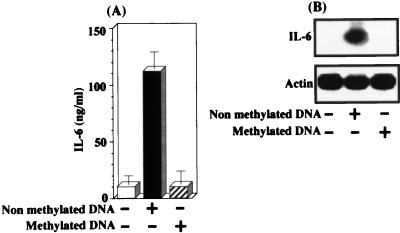

Involvement of palindromic internal CpG motifs in P. gingivalis DNA-stimulated IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts.

Many studies (2, 8, 11, 17, 19, 21, 29, 31, 34–36, 38, 43, 45, 46) have shown involvement of palindromic internal CpG motifs in various biological activities of bacterial DNA for macrophages, B cell, and NK cells. Therefore, it was of interest to demonstrate whether P. gingivalis DNA stimulation of IL-6 expression in the fibroblasts was mediated by the palindromic internal CpG motifs in the nucleic acid. In this regard, since several studies (2, 3, 8, 18, 31, 36) have shown that the CpG motifs in bacterial DNA-induced the biological activities are lost by methylation, we examined this point by using CpG methylase. As shown in Fig. 4, P. gingivalis DNA-stimulated IL-6 expression in the cells was clearly eliminated when the DNA was methylated by the enzyme. These results suggest the involvement of the sequences of palindromic internal CpG motifs in P. gingivalis DNA-stimulated IL-6 expression in the cells.

FIG. 4.

Involvement of palindromic internal CpG motifs in P. gingivalis DNA-induced IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts. Confluent monolayers were incubated in the absence or presence of P. gingivalis 33277 DNA (100 μg/ml) that had been pretreated or not with CpG methylase. (A) The culture media were harvested at 24 h after the initiation of DNA treatment and then measured for IL-6 with the ELISA kit. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations for triplicate cultures. (B) Total RNA was prepared at 6 h after the initiation of DNA treatment. Northern blot analysis was performed with mouse IL-6 and β-actin cDNAs used as probes. An identical experiment independently performed gave similar results.

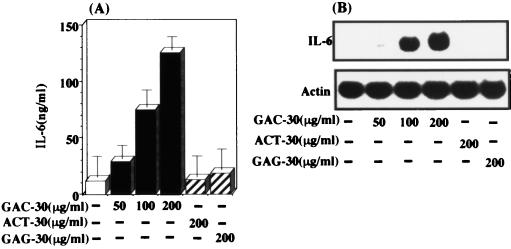

Synthetic palindromic internal CpG motifs are also able to stimulate IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts.

Next, using a synthetic oligonucleotide having CpG motifs, we investigated the stimulatory effect of this oligonucleotide on IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts. As shown in Fig. 5, GAC-30 was able to stimulate IL-6 expression in a dose-dependent manner. However, no such stimulatory effect was observed in the cells treated with control oligonucleotides AGT-30 and GAG-30. In addition, we observed that methylated GAC-30 could not stimulate IL-6 expression (data not shown). These results strongly demonstrate that the palindromic internal CpG motifs function as an important sequence in P. gingivalis DNA-stimulated IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts.

FIG. 5.

Synthetic palindromic internal CpG motifs stimulate also IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts. Confluent monolayers of fibroblasts were incubated in the absence or presence of various doses of 30-mer synthetic oligonucleotides (GAC-30, AGT-30, and GAG-30) as described in Materials and Methods. (A) The culture media were harvested at 24 h after the initiation of the oligonucleotide treatment and then measured for IL-6 by use of the ELISA kit. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations for triplicate cultures. (B) Total RNA was prepared at 6 h after the initiation of treatment. Northern blot analysis was performed with mouse IL-6 and β-actin cDNAs used as probes. An identical experiment independently performed gave similar results.

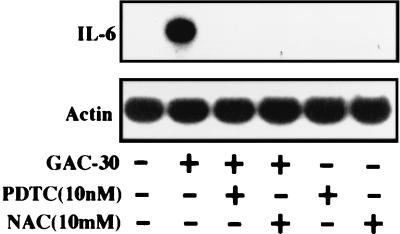

Involvement of transcriptional factor NF-κB in CpG motif-stimulated expression of the IL-6 gene in human gingival fibroblasts.

Several studies (1, 5, 26, 32) have shown that NF-κB functions as a significant transcriptional factor for expression of the IL-6 gene in fibroblasts. Since several studies have demonstrated that the antioxidant PDTC and NAC are potent inhibitors of this transcriptional factor (24, 25, 30, 44), we used both antioxidants to examine whether NF-κB is involved in GAC-30-stimulated expression of the cytokine gene in the cells. Figure 6 shows that GAC-30-stimulated expression of the gene was dramatically inhibited by either inhibitor. Also, these inhibitors were able to eliminate P. gingivalis DNA-stimulated production of the cytokine (data not shown). These data suggested involvement of NF-κB in the CpG motif-stimulated expression of the IL-6 gene in human gingival fibroblasts.

FIG. 6.

Involvement of transcriptional factor NF-κB in synthetic palindromic CpG motif-stimulated expression of the IL-6 gene in human gingival fibroblasts. Confluent fibroblast monolayers were treated or not with various doses of PDTC or NAC for 1 h. Then GAC-30 at 200 μg/ml was added, and total RNA was prepared 6 h later. Northern blot analysis was performed with mouse IL-6 and β-actin cDNAs used as probes. An identical experiment independently performed gave similar results.

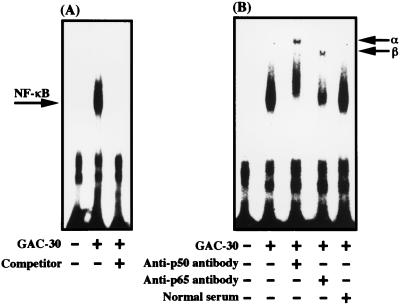

CpG motifs stimulate NF-κB binding to its consensus sequence in human gingival fibroblasts.

Finally, we investigated, using a gel mobility shift assay, whether the CpG motif actually increases NF-κB binding activity in the fibroblasts. Figure 7A shows that GAC-30 markedly increased the NF-κB binding to its consensus sequence in the cells, since the increased NF-κB binding was inhibited by unlabeled oligonucleotide containing the consensus sequence, which was used as a competitor.

FIG. 7.

Synthetic palindromic CpG motifs stimulate NF-κB binding to its consensus sequence in human gingival fibroblasts. Confluent monolayers were incubated in the absence or presence of GAC-30 at 200 μg/ml, and the nuclear proteins were prepared 6 h later. (A) Gel mobility shift assay was performed with 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing the NF-κB consensus sequence. Unlabeled oligonucleotide was used as a competitor. The arrow indicates the position of the DNA and nuclear protein complexes. (B) The nuclear proteins were incubated together with anti-p50 antibody or anti-p65 antibody. Shifted bands of p50 and p65 are indicated by arrows α and β, respectively. An identical experiment independently performed gave similar results.

Since NF-κB is a heterodimer composed by RelA(p65) and NF-κB1(p50) (9, 20, 29), it is important to demonstrate whether the DNA-binding proteins are derived from p65 and p50. Therefore, we examined this point by gel mobility shift assay using specific antibodies against p65 and p50. As shown in Fig. 7B, in extracts treated with the antibodies, the binding proteins were shifted to a position indicating slower migration. In addition, we observed that P. gingivalis DNA also stimulated the specific binding of NF-κB to its consensus sequence (data not shown). These data show that the CpG motifs trigger formation of NF-κB as a transcriptional factor for IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts.

DISCUSSION

P. gingivalis fimbriae and LPS play functional roles as virulence factors in periodontal disease (4, 10, 12–16, 27, 33, 39, 41, 42, 44). On the other hand, since recent studies (8, 11, 31, 34–36, 38, 46) have suggested that bacterial DNA causes inflammation in bacterial infectious diseases via stimulation of production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1, we wished to explore whether P. gingivalis DNA also plays an important role in the pathogenesis of this periodontopathic bacterium. We suspected that this might be the case because P. gingivalis can invade periodontal tissues of periodontal patients with advanced disease (37), and then the invaded bacteria may be destroyed by antibody-dependent cytotoxic action via complement mediation. Consequently, the exposed DNA fragment may stimulate expression of inflammatory cytokines by interacting with fibroblasts in the gingival tissue.

The present study demonstrated that P. gingivalis DNA can stimulate IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts via NF-κB induction and that the stimulatory action is mediated by palindromic internal CpG motifs in the bacterial DNA. This observation is the first to demonstrate that the CpG motifs in bacterial DNA are able to stimulate expression of an inflammatory cytokine in human fibroblasts.

P. gingivalis ATCC 33277- and 381-derived DNAs stimulated in dose-dependent manner IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts. This bacterial DNA-stimulated IL-6 expression was abolished by treatment with DNase but not with RNase. Several earlier studies (11, 21, 34–36, 38) showed that bacterial DNA-stimulated expression of inflammatory cytokines by several kinds of cells was sensitive to DNase. On the other hand, we observed that the stimulatory action of P. gingivalis DNA was not abolished by treatment with polymyxin B, a potent inhibitor of LPS (unpublished data). In this regard, Sparwasser et al. (34, 35) showed that Escherichia coli DNA was able to induce TNF-α expression in peritoneal macrophages from C3H/HeJ mice, which are LPS nonresponders. Therefore, these observations suggest that P. gingivalis DNA itself can stimulate IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts.

As shown in this study, IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts was not stimulated by the eucaryotic DNAs tested. Interestingly, recent studies (3, 35) have suggested that failure of this stimulatory action in eucaryotic DNAs is due to methylation of palindromic internal CpG motifs in their DNA sequences. However, it had still not been demonstrated whether palindromic internal CpG motifs in bacterial DNA are able to stimulate cytokine expression in fibroblasts. Therefore, we examined the involvement of such internal CpG motifs in P. gingivalis DNA-stimulated expression of IL-6 in human gingival fibroblasts and observed that (i) bacterial DNA stimulation of IL-6 expression was eliminated by treatment with CpG methylase, (ii) a synthetic oligonucleotide (GAC-30) having the palindromic sequence GACGTC strongly stimulated IL-6 expression in the fibroblasts but control oligonucleotides (ACT-30 and GAG-30) did not; (iii) methylated GAC-30 also could not stimulate cytokine expression. These observations strongly suggest that the palindromic internal CpG motifs play functional roles in P. gingivalis DNA-stimulated expression of IL-6 in gingival fibroblasts.

It is of importance to explore the signal pathway of the palindromic internal CpG motif-stimulated expression of the IL-6 gene in human gingival fibroblasts. Interestingly, Kimura et al. (17) showed that the palindromic CpG motifs stimulate gamma interferon production by the macrophage cell line J774.1 via scavenger receptors. This observation suggested to us that bacterial DNA and its palindromic internal CpG motifs may induce cellular signal transduction via their receptors on the macrophage cell line. In this regard, since we observed that P. gingivalis DNA- or GAC-30-stimulated expression of the IL-6 gene in human gingival fibroblasts could be inhibited by H-7, a potent inhibitor of serine/threonine kinase (unpublished data), this kinase at least may be involved in the signal pathway of the bacterial DNA or CpG motifs in the cells.

In addition, we focused on which transcriptional factors mediate the CpG motif-stimulated expression of IL-6 in human gingival fibroblasts. Since NF-κB functions as a significant transcriptional factor for expression of the IL-6 gene in several fibroblast cell lines, we examined its possible involvement by testing the effects of PDTC and NAC, NF-κB inhibitors. We observed that either inhibitor strongly blocked the CpG motif-stimulated expression of the IL-6 gene in the cells. In addition, our gel mobility shift assay showed that the CpG motifs were able to increase the specific binding of NF-κB in the cells. These observations strongly suggest that NF-κB is a significant transcriptional factor in the CpG motif-stimulated expression of the IL-6 gene in human gingival fibroblasts. In this regard, Sparwasser et al. (35) and Stacey et al. (36) have shown that the CpG motifs are able to increase NF-κB binding in macrophage cell line ANA-1 cells and in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages. However, we have not yet investigated the signal molecules involved in the CpG motif stimulation of NF-κB in gingival fibroblasts. Therefore, in future experiments, it will be necessary to identify such molecules.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated here that P. gingivalis DNA and its palindromic internal CpG motifs stimulate IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts via stimulation of NF-κB binding and also suggest that this bacterial DNA may function as a virulence factor of the organism in periodontal disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anisowicz A, Messineo M, Lee S W, Sager R. An NF-kappa B-like transcription factor mediates IL-1/TNF-alpha induction of gro in human fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1991;147:520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballas Z K, Rasmussen W L, Krieg A M. Induction of NK activity in murine and human cells by CpG motifs in oligodeoxynucleotides and bacterial DNA. J Immunol. 1996;157:1840–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird P A. CpG-rich islands and the function of DNA methylation. Nature. 1986;321:209–213. doi: 10.1038/321209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bom-van Noorloos A A, van der Meer J W M, van de Gevel J S, Schepens E, MatiJin van Steebergen T J, Burger E H. Bacteroides gingivalis stimulates bone resorption via interleukin-1 production by mononuclear cells. The relative role for B. gingivalis endotoxin. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:409–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1990.tb02338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brach M A, Gruss H J, Kaisho T, Asano Y, Hirano T, Herrmann F. Ionizing radiation induces expression of interleukin 6 by human fibroblasts involving activation of nuclear factor-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8466–8472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Takeshita A, Ozaki K, Kitano S, Hanazawa S. Transcriptional regulation by transforming growth factor β of the expression of retinoic acid and retinoic X receptor genes in osteoblastic cells is mediated through AP-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31602–31606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowdery J S, Chace J H, Yi A K, Krieg A M. Bacterial DNA induces NK cells to produce IFN-gamma in vivo and increases the toxicity of lipopolysaccharides. J Immunol. 1996;156:4570–4575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita T, Nolan G P, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Independent modes of transcriptional activation by the p50 and p65 subunits of NF-kappa B. Genes Dev. 1992;6:775–787. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genco R J, Slots J. Host responses in periodontal diseases. J Dent Res. 1984;63:441–451. doi: 10.1177/00220345840630031601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halpern M D, Kurlander R J, Pisetsky D S. Bacterial DNA induces murine interferon-gamma production by stimulation of interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Cell Immunol. 1996;167:72–78. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanazawa S, Hirose K, Ohmori Y, Amano S, Kitano S. Bacteroides gingivalis fimbriae stimulate production of thymocyte-activating factor by human gingival fibroblasts. Infect Immun. 1988;56:272–274. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.272-274.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanazawa S, Kawata Y, Takeshita A, Kumada H, Okithu M, Tanaka S, Yamamoto Y, Masuda T, Umemoto T, Kitano S. Expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) in adult periodontal disease: increased monocyte chemotactic activity in crevicular fluids and induction of MCP-1 expression in gingival tissues. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5219–5224. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5219-5224.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanazawa S, Murakami Y, Takeshita A, Nishida H, Ohta K, Amano S, Kitano S. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae induce gene expression of neutrophil chemotactic factor, KC, of mouse peritoneal macrophages through protein kinase C. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1544–1549. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1544-1549.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanazawa S, Murakami Y, Hirose K, Amano S, Kitano S. Porphyromonas (Bacteroides gingivalis fimbriae activate mouse peritoneal macrophages and induce gene expression and production of interleukin-1. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1972–1977. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.1972-1977.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawata Y, Hanazawa S, Amano S, Murakami Y, Matsumoto T, Nishida K, Kitano S. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae stimulate bone resorption in vitro. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3012–3016. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.3012-3016.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura Y, Sonehara K, Kuramoto E, Makino T, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T, Kataoka T, Tokunaga T. Binding of oligoguanylate to scavenger receptors is required for oligonucleotides to augment NK cell activity and induce IFN. J Biochem. 1994;116:991–994. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieg A M, Yi A K, Matson S, Waldschmidt T J, Bishop G A, Teasdale R, Koretzky G A, Koretzky D M. CpG motifs in bacteria DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature. 1995;374:546–549. doi: 10.1038/374546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuramoto E, Yano O, Kimura Y, Baba M, Makino T, Yamamoto S, Kataoka T, Tokunaga T. Oligonucleotide sequences required for natural killer cell activation. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1992;83:1128–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1992.tb02734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenardo M J, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: a pleiotropic mediator of inducible and tissue-specific gene control. Cell. 1989;58:227–229. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90833-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipford G B, Sparwasser T, Bauer M, Zimmermann S, Heeg K, Wagner H. Immunostimulatory DNA: sequence-dependent production of potentially harmful or useful cytokines. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3420–3426. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. pp. 365–389. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer M, Caselmann W H, Schluter V, Schreck R, Hofschneider P H, Baeuerle P A. Hepatitis B virus transactivator MHBst: activation of NF-kappa B, selective inhibition by antioxidants and integral membrane localization. EMBO J. 1992;11:2991–3001. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mihm S, Ennen J, Pessara U, Kurth R, Droge W. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication and NF-kappa B activity by cysteine and cysteine derivatives. AIDS. 1991;5:497–503. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyazawa K, Mori A, Yamamoto K, Okudaira H. Transcriptional roles of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-beta, nuclear factor-kappaB, and C-promoter binding factor 1 in interleukin (IL)-1 beta-induced IL-6 synthesis by human rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7620–7627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murakami Y, Iwahashi H, Yasuda H, Umemoto T, Namikawa I, Kitano S, Hanazawa S. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbrillin is one of the fibronectin-binding proteins. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2571–2576. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2571-2576.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato Y, Roman M, Tighe H, Lee D, Corr M, Nguyen M D, Silverman G J, Lots M, Carson D A, Raz E. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences necessary for effective intradermal gene immunization. Science. 1996;273:352–354. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5273.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitz M L, Baeuerle P A. The p65 subunit is responsible for the strong transcription activating potential of NF-kappa B. EMBO J. 1991;10:3805–3817. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schreck R, Meier B, Mannel D N, Droge W, Baeuerle P A. Dithiocarbamates as potent inhibitors of nuclear factor kappa B activation in intact cells. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1181–1194. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz D A, Quinn T J, Thorne P S, Sayeed S, Yi A K, Krieg A M. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA cause inflammation in the lower respiratory tract. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:68–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI119523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibanuma M, Kuroki T, Nose K. Inhibition by N-acetyl-l-cysteine of interleukin-6 mRNA induction and activation of NF kappa B by tumor necrosis factor alpha in a mouse fibroblastic cell line, Balb/3T3. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:62–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sismey-Durrant H J, Hopps R M. The effect of lipopolysaccharide from the oral bacterium Bacteroides gingivalis on osteoclastic resorption of sperm-whale dentine slices in vitro. Arch Oral Biol. 1987;32:911–913. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(87)90106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sparwasser T, Miethke T, Lipford G, Borschert K, Hacker H, Heeg K, Wagner H. Bacterial DNA causes septic shock. Nature. 1997;386:336–337. doi: 10.1038/386336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sparwasser T, Miethke T, Lipford G, Erdmann A, Hacker H, Heeg K, Wagner H. Macrophages sense pathogens via DNA motifs: induction of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated shock. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1671–1679. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stacey K J, Sweet M J, Hume D A. Macrophages ingest and are activated by bacterial DNA. J Immunol. 1996;157:2116–2122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suglie F R. Bacterial invasion and its role in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. In: Hamada S, Holt S C, McGhee J R, editors. Periodontal disease; pathogens and host immune responses. Tokyo, Japan: Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd.; 1981. pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sweet M J, Stacey K J, Kakuda D K, Markovich D, Hume D A. IFN-gamma primes macrophage responses to bacterial DNA. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:263–271. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takada H, Mihara J, Morisaki I, Hamada S. Induction of interleukin-1 and -6 in human gingival fibroblast cultures stimulated with Bacteroides lipopolysaccharides. Infect Immun. 1991;59:295–301. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.295-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeshita A, Imai K, Kato S, Kitano S, Hanazawa S. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 synergism toward transforming growth factor-β1-induced AP-1 transcriptional activity in mouse osteoblastic cells via its nuclear receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14738–14744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeshita A, Murakami Y, Yamashita Y, Ishida M, Fuzisawa S, Kitano S, Hanazawa S. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae use β2 integrin (CD11/CD18) on mouse peritoneal macrophages as a cellular receptor, and the CD18 β chain plays a functional role in fimbrial signaling. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4056–4060. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4056-4060.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tamura L, Tokuda M, Nagaoka S, Takada H. Lipopolysaccharides of Bacteroides intermedius (Prevotella intermedia) and Bacteroides (Porphyromonas) gingivalis induce interleukin-8 gene expression in human gingival fibroblast cultures. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4932–4937. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4932-4937.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tokunaga T, Yano O, Kuramoto E, Kimura Y, Yamamoto T, Kataoka T, Yamamoto S. Synthetic oligonucleotides with particular base sequences from the cDNA encoding proteins of Mycobacterium bovis BCG induce interferons and activate natural killer cells. Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36:55–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watanabe A, Takeshita A, Kitano S, Hanazawa S. CD14-mediated signal pathway of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide in human gingival fibroblasts. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4488–4494. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4488-4494.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T, Kataoka T, Kuramoto E, Yano O, Tokunaga T. Unique palindromic sequences in synthetic oligonucleotides are required to induce IFN and augment IFN-mediated natural killer activity. J Immunol. 1992;148:4072–4076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yi A K, Martin T L, Matson S, Krieg A M. Rapid immune activation by CpG motifs in bacterial DNA. Systemic induction of IL-6 transcription through an antioxidant-sensitive pathway. J Immunol. 1996;157:5394–5402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]