Abstract

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) may present as a multi-organ disease with a hyperinflammatory and prothrombotic response (immunothrombosis) in addition to upper and lower airway involvement. Previous data showed that complement activation plays a role in immunothrombosis mainly in severe forms.

The study aimed to investigate whether complement involvement is present in the early phases of the disease and can be predictive of a negative outcome.

We enrolled 97 symptomatic patients with a positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 presenting to the emergency room. The patients with mild symptoms/lung involvement at CT-scan were discharged and the remaining were hospitalized. All the patients were evaluated after a 4-week follow-up and classified as mild (n. 54), moderate (n. 17) or severe COVID-19 (n. 26). Blood samples collected before starting any anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive therapy were assessed for soluble C5b-9 (sC5b-9) and C5a plasma levels by ELISA, and for the following serum mediators by ELLA: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12p70, IFNγ, IFNα, VEGF-A, VEGF-B, GM-CSF, IL-2, IL-17A, VEGFR2, BLyS. Additional routine laboratory parameters were measured (fibrin fragment D-dimer, C-reactive protein, ferritin, white blood cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, platelets, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen). Fifty age and sex-matched healthy controls were also evaluated.

SC5b-9 and C5a plasma levels were significantly increased in the hospitalized patients (moderate and severe) in comparison with the non-hospitalized mild group. SC5b9 and C5a plasma levels were predictive of the disease severity evaluated one month later. IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, IL-10 and complement split products were higher in moderate/severe versus non-hospitalized mild COVID-19 patients and healthy controls but with a huge heterogeneity. SC5b-9 and C5a plasma levels correlated positively with CRP, ferritin values and the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio.

Complement can be activated in the very early phases of the disease, even in mild non-hospitalized patients. Complement activation can be observed even when pro-inflammatory cytokines are not increased, and predicts a negative outcome.

Keywords: Complement, Cytokines, Covid-19, Disease severity, Disease outcome

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) displays a bimodal presentation with the first phase characterized by flu-like symptoms and the second one associated with pneumonia and multi-organ damage. The final clinical outcome is heterogeneous. While most of the patients display a mild or moderate upper airway illness not requiring hospitalization, some develop severe disease and to life-threatening acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [[1], [2], [3]]. These complications are largely due to immune dysregulation with a hyperinflammatory and prothrombotic response (immunothrombosis) triggered by the SARS-CoV-2 virus and sustained by different pathogenic mechanisms [4,5].

Besides the high circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. Interleukin [IL]-6) there is growing evidence that complement activation plays a crucial role [6] as suggested by increased plasma levels of activation products (soluble C5b9 [sC5b-9], C5a) and complement deposits in the affected tissues of COVID-19 patients [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]]. This finding is consistent with the complement involvement reported in several viral diseases including infections with other coronaviruses [[27], [28], [29]] and the suggested protective effects of complement blockade on COVID-19 [6].

Moreover, complement activation is associated with endotheliopathy, increased necrosis markers and disease severity with a trend to normalization in remission [8,30]. Altogether this finding supports that inflammation, and in particular complement activation, is crucial in COVID-19 pathogenesis and may be used as a predictive tool.

Predicting the risk of severe COVID-19 would be useful to direct limited health resources toward patients at the highest risk requiring more intensive management. Age, male sex, genetic markers and comorbidities (e.g. obesity, diabetes, immunosuppression) are well-known variables affecting the final outcome of the disease and predictive of more severe disease [31,32].

While the studies on the predictive markers of disease aggressiveness have been largely performed in severe/hospitalized patients, much less information is available for mild COVID-19 in the early phase of the disease. The aim of our study was to assess whether complement is already activated at the presentation of the disease with different severity and whether the plasma levels of complement activation products can predict the clinical outcome and in particular the extent of lung involvement. Therefore, we searched for relationships between circulating levels of markers of inflammation and complement activation at baseline, and COVID-19 severity (classified as mild, moderate and severe) after a follow-up of four weeks. Since treatment may potentially affect the biological parameters, only patients whose blood samples were obtained before receiving any anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive drugs were included in the study.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients

We studied 97 symptomatic patients presenting to the emergency room (ER) of Reggio Emilia Hospital between 9th March 2020 and 22nd April 2020 for suspected COVID-19 during the outbreak peak. These patients were prospectively followed-up. The inclusion criteria were age > 18 years and a diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed by a positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 in at least one biological sample; the exclusion criteria were an infectious disease other than SARS-CoV2, previous or current autoimmune diseases, and pregnancy.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, the diagnostic protocol for these patients included nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs for RT-PCR, blood tests, chest X-rays, and CT scans in cases of positive X-ray findings or negative X-rays but highly suggestive clinical features. Starting from March 13, 2020, each radiologist completed a routine CT report and a structured report that included the presence/absence of ground-glass opacities and consolidations, and the extent of pulmonary lesions using a visual scoring system (< 20%, 20–39%, 40–59%, ≥ 60%) [33]. CTs performed between March 9 and March 13, 2020 (before the introduction of the structured report) were retrospectively reviewed by two expert chest radiologists (L.S. and G.B.) to collect the same parameters described above.

A multidisciplinary team (pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists, intensive care specialists and emergency physicians) established a six-class classification based on patient features, vital signs, medical history, symptoms, blood test results and instrumental findings to manage patients presenting to the ER [34]. Six clinical phenotypes were identified. Patients belonging to the first two clinical phenotypes (Phenotypes 1 and 2A) were discharged and referred to the preventive medicine and public health department for follow-up and advised to home quarantine and symptomatic therapy. These patients usually had a fever, with or without respiratory symptoms, with SpO2 > 95% in room air and respiratory rate < 25 breaths per minute, with or without radiological evidence of pneumonia (usually <20% of lung parenchymal involvement at CT-scan), and with a negative walking test. All other patients were hospitalized.

The demographic characteristics of the enrolled patients are reported in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients.

| Non-hospitalized (n = 54) | Hospitalized (n = 43) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Gender, %F (n) | 59.30 (32) | 26.20 (11) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 50.50 (15.8) | 61.70 (12) |

| Lung damage, % (n) | ||

| Parenchymal involvement | ||

| <20% | 100.00 (54) | 5.90 (1) |

| 20–60% | 0.00 (0) | 73.90 (31) |

| >60% | 0.00 (0) | 23.20 (11) |

| Ground glass | 71.70 (33/46) | 97.05 (42) |

| Area of parenchymal consolidation | 30.40 (14/46) | 74.80 (32) |

The clinical outcome was evaluated after a 4-week follow-up period and the patients were classified as mild (n.54), moderate (n. 17) or severe COVID-19 (n. 26). Mild cases included patients with phenotypes 1 and 2A patients, who during the follow-up had stable disease and were not hospitalized; patients presenting with phenotypes 2B and 3 at ER admission and not worsening during the follow-up were considered moderate COVID-19. These patients were hospitalized and responded to conventional patients O2 therapy. Phenotypes 4 and 5 at ER admission or patients presenting with milder disease, but worsening during the follow-up, were considered severe cases. These patients were hospitalized and were admitted to sub-intensive units or to the intensive care unit dedicated to COVID-19 patients requiring non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) or intubation.

The healthy control group comprised 50 healthy subjects: 35 men and 15 women with a median age 54 years, range 35–65. Samples were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic and randomly selected to match sex and age of the patients fom the archives of IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano.

On the day of admission or on the following day, antecubital vein blood samples were collected into EDTA tubes for the measurement of sC5b-9 and C5a, and in serum tubes for the measurement of the cytokines. Within two hours, the samples were centrifuged at 2000 ×g for 15 min at room temperature, and then the plasma aliquots were immediately frozen and stored at -80C° until testing. Serum/plasma samples from these patients have been collected before starting any therapy that could potentially affect the immune parameters under investigation. Most of the hospitalized patients with moderate/severe COVID19 were treated with tocilizumab and/or glucocorticoids.

The results of the following laboratory parameters were obtained from the patients' clinical records: fibrin fragment D-dimer, C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, white blood cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, platelets, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and fibrinogen.

The study was approved by the Area Vasta Emilia Nord (AVEN) Ethics Committee on 28 July 2020 (protocol number 855/2020/OSS/AUSLRE – COVID-2020- 12371808) and was carried out in conformity with the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and the code of Good Clinical Practice.

2.2. Complement activation products

The plasma levels of sC5b-9 and C5a were measured using solid-phase assays (MicroVue Complement SC5b-9 Plus EIA kit, MicroVue Complement C5a EIA, Quidel Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA) as previously described [7,8]. Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) were respectively 6.8% and 13.1% for sC5b-9 and < 12% for C5a. The lower detection limit was 3.7 ng/ml for sC5b-9 and 0.01 ng/ml for C5a. The following cutoffs [95th percentile] were calculated in the group of healthy subjects: 411.50 ng/ml for sC5b-9 and 15.53 ng/ml for C5a respectively.

2.3. Cytokine detection

We performed multi-analyte profiling of 17 soluble mediators in patients' and controls' serum samples using the automated microfluidic analyzer ELLA (BioTechne, Minneapolis, MN, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Based on the assay dilution factor, the following panels were analyzed: panel 1) IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα; panel 2) IL-4, IL-10, IL-12p70, IFNγ; panel 3) IFNα, VEGF-A, VEGF-B, GM-CSF; panel 4) IL-2, IL-17A, VEGFR2, BLyS. Intra- and inter-assay CVs were < 8%.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients. Unless otherwise indicated, all data are given as median [25th and 75th percentiles]. Differences among unmatched groups were assessed by applying a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test and pairwise comparisons were adjusted by using Dunn's post hoc test.

Spearman's test was performed to assess the correlation between continuous variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. The association between COVID-19 outcome (moderate/severe vs mild) and complement split products was investigated by performing a multivariable logistic model. Age and comorbidities were identified as confounders and included in the model. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Statistical analysis was performed using R statistical package version 4.0.5 for Windows [35].

3. Results

3.1. Patients

Of the 97 patients included in the study, 54 were classified as mild, 17 as moderate, and 26 as severe COVID-19 according to the scoring method detailed in the section Materials and Methods. Compared to non-hospitalized patients, those who were hospitalized were older, more likely to be males, and had greater lung parenchymal involvement, areas of ground-glass opacity, and parenchymal consolidation. Only one patient with lung involvement <20% was initially discharged but then hospitalized a few days after the first visit to the hospital and eventually classified as moderate.

Table 2 reports the therapies carried out in the three groups during the follow-up. All the severe patients who underwent intubation, had been previously treated with NIV.

Table 2.

Therapies carried out in the included patients.

| Mild (n = 54) | Moderate (n = 17) | Severe (n = 26) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapy, % (n) | |||

| NIV | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 96.2 (25) |

| Intubation | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 38.5 (10) |

| TCZ + GCs + Anticoagulants | 0.0 (0) | 5.9 (1) | 42.3 (11) |

| TCZ + Anticoagulants | 0.0 (0) | 52.9 (9) | 42.3 (11) |

| GCs + Anticoagulants | 0.0 (0) | 11.8 (2) | 7.7 (2) |

| Anticoagulants | 3.7 (2) | 29.4 (5) | 7.7 (2) |

NIV: non-invasive ventilation; TCZ: Tocilizumab; GCs: glucocorticosteroids; Anticoagulants: only 2 patients were on Vitamin K antagonists and the remaining were on prophylactic heparin.

3.2. Laboratory profile of the patients at admission

Blood samples from all the patients were collected before starting the treatment to avoid any drug interference with the biological parameters to analyse.

Table 3 reports the hematological and inflammatory parameters of the included patients.

Table 3.

Hematological and inflammatory parameters of the cohort.

| Parameter | Mild |

Moderate |

Severe |

Normal ranges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 54) | (n = 17) | (n = 26) | ||

| D-dimer ng/ml | 306 [221 to 458] | 998 [446 to 1320] | 1171 [527 to 3031] | <500 |

| CRP mg/dl | 0.34 [0.05 to 1.06] | 8.01 [5.84 to 13.88] | 17.2 [12.82 to 26.31] | 0.00– - 0.50 |

| Ferritin ng/ml | 152 [64 to 330] | 906 [633 to 1100] | 602 [342 to 1664] | 30– - 400 |

| PT ratio | 0.98 [0.93 to 1.03] | 1.02 [1.01 to 1.10] | 1.11 [1.06 to 1.16] | 0.84– - 1.20 |

| aPTT ratio | 1.02 [0.92 to 1.12] | 1.13 [1.04 to 1.19] | 1.11 [0.97 to 1.25] | 0.86– - 1.20 |

| Fibrinogen | 365 [318 to 442] | 574 [509 to 631] | 646 [520 to 722] | 165– - 350 |

| Leukocytes x103/μl | 5.60 [4.34 to 7.23] | 6.71 [5.31 to 9.76] | 6.56 [5.45 to 8.34] | 4.80– -10.80 |

| Neutrophils x103/μl | 3.80 [2.70 to 5.50] | 4.60 [4.00 to 8.30] | 6.60 [5.50 to 8.30] | 1.50– - 6.50 |

| Lymphocytes x103/μl | 1.40 [1.10 to 1.80] | 0.90 [0.70 to 1.40] | 0.60 [0.50 to 0.90] | 1.20– - 3.40 |

| Monocytes x103/μl | 0.40 [0.30 to 0.50] | 0.30 [0.20 to 0.50] | 0.20 [0.20 to 0.40] | 0.20– - 0.60 |

| Platelets | 226 [195 to 277] | 209 [163 to 264] | 237 [219 to 319] | 130– - 430 |

| x103/μl |

3.3. Complement activation product levels predict disease severity

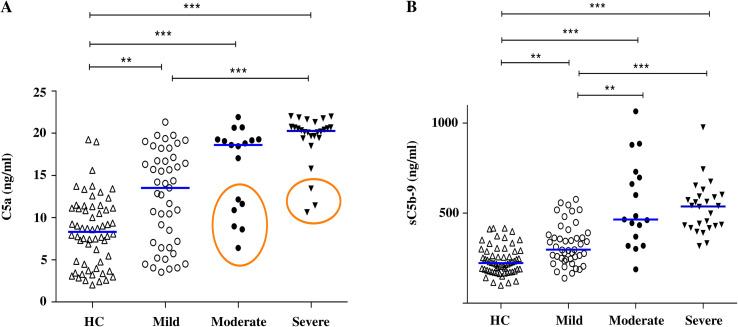

Plasma levels of soluble sC5b-9 and C5a in the moderate and the severe subgroups of COVID-19 patients were significantly higher than in the healthy controls, consistent with the data reported in our previous study [8]. In particular, some moderate/severe patients display plasma levels of C5a lower than the cutoff. However, most of these patients (six out of nine) had high levels of sC5b-9 (Supplementary Table A.1). The data presented in Fig. 1 also show that the plasma levels of C5a and SC5b-9 were significantly higher in the mild group of COVID-19 patients as compared to the healthy controls.

Fig. 1.

Complement activation products in Covid-19 patients. Distribution of C5a (A) and sC5b-9 (B) levels in the mild, moderate and severe COVID-19 groups, and in the healthy controls (HC). The bars are the median values. The circles identify samples with C5a levels lower than the cutoff (15.53 ng/ml). ** p < 0.001, *** p < 0.0001.

The plasma levels of C5a and sC5b-9 at admission were predictive of the disease severity evaluated one month later.

As reported in Table 1 moderate/severe disease was associated with older age and was more frequent in males. Patients with ≥1 concomitant comorbidity were older than patients without (61.5 ± 13.5 vs 47.3 ± 13.6, p < 0.0001) and were equally distributed among male and female patients. Therefore, the male gender and the presence of ≥1 comorbidity increased the risk of moderate/severe COVID-19. C5a and sC5b-9 plasma levels predicted the disease severity also after adjusting for gender, and the presence of comorbidities (p = 0.02 and p < 0.001, respectively).

3.4. Cytokine levels

IL-6, IL-10, and TNFα serum levels were significantly higher in all three patients' sub-groups versus the healthy controls (Fig. 2 ). When the hospitalized moderate/severe patients were grouped together, the serum levels of IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNFα were substantially higher than those in the non-hospitalized mild group even though with large variability (data not shown). There were no significant differences in serum levels of IL-1β, IFNγ, IL-12p70, IL-4, GM-CSF, IFNα, VEGF-A, VEGF-B, BLyS, IL-17A, IL-2, and VEGFR2 between the examined groups.

Fig. 2.

Cytokine quantification in Covid-19 patients. Serum levels of IL-6, IL-10, IL-8 and TNFα in the mild, moderate and severe COVID-19 groups and healthy controls. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001, *** p < 0.0001.

3.5. Correlation between complement activation products and cytokines

The levels of IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, IL-10 and complement activation products were higher in hospitalized (moderate/severe) versus non-hospitalized (mild) COVID-19 patients and healthy controls. However, the analytical data displayed a huge variability. Fig. 3 shows the levels of IL-6 and C5a (A) or sC5b-9 (B) in the three clinical subgroups of patients. The complement activation product levels were widely distributed particularly in the mild and the moderate subgroups, suggesting that complement activation is not necessarily associated with the increase of the prototype pro-inflammatory cytokine (i.e. IL-6) in COVID-19 patients. Comparable results were found for the relationship between complement activation products and the other cytokines (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Relationship between complement activation products and IL-6 in Covid-19 patients. Analytical data of C5a (A) or sC5b-9 (B) and of IL-6 levels in the three patients' subgroups. Vertical dotted lines correspond to C5a (A) or sC5b-9 (B) cutoff. Horizontal dotted lines correspond to IL-6 cutoff levels.

3.6. Correlation between complement activation product levels and other laboratory parameters

SC5b-9 and C5a plasma levels correlated positively with CRP values (r = 0.714 [95%CI: 0.578 to 0.811], p < 0.0001 and r = 0.633 [95%CI: 0.472 to 0.754], p < 0.0001 respectively). A comparable correlation was also found between sC5b-9, C5a levels and ferritin (r = 0.645 [95%CI: 0.477 to 0.767], p < 0.0001; r = 0.551 [95%CI: 0.357 to 0.700], p < 0.0001). Levels of both CRP and ferritin have been reported to increase during the hyper-inflammatory state of COVID-19 [36].

Levels of both sC5b9 and C5a significantly correlated also with another parameter of COVID-19 severity such as the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (r = 0.497 [95%CI: 0.304 to 0.651] p < 0.0001 and r = 0.450 [95%CI: 0.246 to 0.615] p < 0.0001 respectively).

4. Discussion

The present study shows that the plasma levels of complement activation products are increased in COVID-19 patients extending similar findings previously reported in another cohort of patients recruited in the North of Italy [7,8]. In addition, the data reveal that: (i) complement can be activated in the very early phases of the disease and in mild non-hospitalized patients; (ii) complement activation occurs even when pro-inflammatory cytokines are not increased, and (iii) the measurement of complement activation products before anti-inflammatory therapy predicts a negative outcome.

Complement activation in COVID-19, particularly in severely ill patients in whom immunothrombosis represents the main pathogenic mechanism [6]. In fact, the activation of the complement cascade has been associated with parameters of endothelial damage and necrosis markers [8,30]. These finding together with the known ability of complement to induce neutrophil activation and chemotaxis, activation, and to promote NET formation support the crucial role played by this system in thrombus formation, particularly in lung microcirculation [6,37]. Although pro-inflammatory cytokines may also contribute, recent studies have shown that a significant number of patients have low serum levels of cytokines and manifest cytokine-independent disease progression, in contrast with high complement activation markers [8,38,39]. These findings suggest that the two inflammatory pathways can be distinct. The demonstration of increased complement activation products at the beginning of the disease and even in the not hospitalized mild variants is consistent with the possibility that inflammation may not solely dependent on the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

The mechanism of complement activation in COVID-19 patients has not been fully elucidated. SARS-CoV-2 was reported to activate complement through the N-protein that binds MASP-2 thereby activating the lectin pathway of the complement cascade [40,41]. In vitro studies have also shown that spike proteins (subunits S1 and S2) of SARS-CoV-2 may activate the alternative pathway [[41], [42], [43]]. In addition, complement was found to be activated via the classical pathway by antibodies against the viral RBD and by antibodies to self-antigens in tissues damaged by the virus [25,44]. Another study reported that an inducible cell-intrinsic C3 convertase was generated in respiratory epithelial cells during infection with SARS-CoV-2 [45].

The endothelial injury in COVID-19, especially in severe cases, has similarities to that reported in other thrombotic microangiopathies in which a genetic predisposition for complement activation plays a pathogenic role in combination with a triggering factor leading to thrombosis and tissue damage [46,47]. A genetic predisposition toward complement activation has also been reported in severe COVID-19 which may contribute to the final pathogenic scenario [[48], [49], [50]].

Complement activation products proved to be predictive markers of the disease outcome evaluated after four weeks of follow-up after excluding any interference of variables, such as age, gender, and co-morbidities, that are well known to represent negative predictors. Moreover, the fact that the blood samples were collected from the patients before starting treatment rules out any interference of concomitant anti-inflammatory therapies.

It is worth noting that the levels of sC5b-9 appear to be a more reliable marker of in vivo complement activation being high in a few patients whose C5a levels fell within the normal range. This finding is consistent with data in our previous studies [7,8] and can be explained by the fact that soluble sC5b-9 is a more stable complex that remains in the fluid phase in comparison with anaphylatoxin C5a which can be cleared and recycled by C5a receptors with different kinetics [51,52].

The crucial role of complement activation is further supported by the correlation between the C5a and C5b9 levels and the values of well-known markers of inflammation in COVID-19 such as CRP and ferritin [36]. The same is also true for the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio which has been reported as an additional marker of inflammation and a negative prognostic factor [53].

In conclusion, the measurement of complement activation products and their kinetics is emerging as a useful tool for stratifying patients at higher risk of severe disease and for optimizing appropriate utilization of the health system resources during a pandemic situation.

Funding

This work was funded by Ministero della Salute, Italy, Ricerca Corrente to PLM, Ricerca sul Covid-19 COVID-2020-12371808 to CS and PLM; and by Foundation for Research in Rheumatology FOREUM

Statement of ethics approval

The Ethics Committee at the Area Vasta Emilia Nord (AVEN) approved the study (protocol number 855/2020/OSS/AUSLRE – COVID-2020-12371808). All the participants gave their informed consent.

Author contribution

PLM, SC, MOB and CS: study design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data and manuscript drafting. PAL and FP: analysis and interpretation of data. LS and GB: analysis and interpretation of radiological data. All authors: providing data and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval of the submitted version.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2022.103232.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knight J.S., Caricchio R., Casanova J.L., Combes A.J., Diamond B., Fox S.E., et al. The intersection of COVID-19 and autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2021;131 doi: 10.1172/JCI154886. e154886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson E., Reynolds G., Botting R.A., Calero-Nieto F.J., Morgan M.D., Tuong Z.K., et al. Single-cell multi-omics analysis of the immune response in COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021;27:904–916. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01329-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afzali B., Noris M., Lambrecht B.N., Kemper C. The state of complement in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22:77–84. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00665-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cugno M., Meroni P.L., Gualtierotti R., Griffini S., Grovetti E., Torri A., et al. Complement activation in patients with COVID-19: a novel therapeutic target. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:215–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cugno M., Meroni P.L., Gualtierotti R., Griffini S., Grovetti E., Torri A., et al. Complement activation and endothelial perturbation parallel COVID-19 severity and activity. J Autoimmun. 2021;116 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102560. 102560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carvelli J., Demaria O., Vély F., Batista L., Chouaki Benmansour N., Fares J., et al. Association of COVID-19 inflammation with activation of the C5a-C5aR1 axis. Nature. 2020;588:146–150. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramlall V., Thangaraj P.M., Meydan C., Foox J., Butler D., Kim J., et al. Immune complement and coagulation dysfunction in adverse outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2020;26:1609–1615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1021-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peffault de Latour R., Bergeron A., Lengline E., Dupont T., Marchal A., Galicier L., et al. Complement C5 inhibition in patients with COVID-19 - a promising target? Haematologica. 2020;105:2847–2850. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.260117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holter J.C., Pischke S.E., de Boer E., Lind A., Jenum S., Holten A.R., et al. Systemic complement activation is associated with respiratory failure in COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:25018–25025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010540117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alosaimi B., Mubarak A., Hamed M.E., Almutairi A.Z., Alrashed A.A., AlJuryyan A., et al. Complement anaphylatoxins and inflammatory cytokines as prognostic markers for COVID-19 severity and in-hospital mortality. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.668725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savitt A.G., Manimala S., White T., Fandaros M., Yin W., Duan H., et al. SARS-CoV-2 exacerbates COVID-19 pathology through activation of the complement and Kinin systems. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.767347. 767347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam L.K.M., Reilly J.P., Rux A.H., Murphy S.J., Kuri-Cervantes L., Weisman A.R., et al. Erythrocytes identify complement activation in patients with COVID-19. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2021;2021(321):L485–L489. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brasen C.L., Christensen H., Olsen D.A., Kahns S., Andersen R.F., Madsen J.B., et al. Daily monitoring of viral load measured as SARS-CoV-2 antigen and RNA in blood, IL-6, CRP and complement C3d predicts outcome in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2021;59:1988–1997. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2021-0694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber S., Massri M., Grasse M., Fleischer V., Kellnerová S., Harpf V., et al. Systemic inflammation and complement activation parameters predict clinical outcome of severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Viruses. 2021;13:2376. doi: 10.3390/v13122376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma L., Sahu S.K., Cano M., Kuppuswamy V., Bajwa J., McPhatter J., et al. Increased complement activation is a distinctive feature of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Immunol. 2021;6 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abh2259. eabh2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu J., Gerber G.F., Chen H., Yuan X., Chaturvedi S., Braunstein E.M., et al. Complement dysregulation is associated with severe COVID-19 illness. Haematologica. 2022;107:1095–1105. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.279155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcos-Jiménez A., Sánchez-Alonso S., Alcaraz-Serna A., Esparcia L., López-Sanz C., Sampedro-Núñez M., et al. Deregulated cellular circuits driving immunoglobulins and complement consumption associate with the severity of COVID-19 patients. Eur J Immunol. 2021;51:634–647. doi: 10.1002/eji.202048858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charitos P., Heijnen I.A.F.M., Egli A., Bassetti S., Trendelenburg M., Osthoff M. Functional activity of the complement system in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a prospective cohort study. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.765330. 765330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senent Y., Inogés S., López-Díaz de Cerio A., Blanco A., Campo A., Carmona-Torre F., et al. Persistence of high levels of serum complement C5a in severe COVID-19 cases after hospital discharge. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.767376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng W., Hornung R., Xu K., Yang C.H., Li J. Complement C3 identified as a unique risk factor for disease severity among young COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Sci Rep. 2021;11:7857. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82810-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magro C., Mulvey J.J., Berlin D., Nuovo G., Salvatore S., Harp J., et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macor P., Durigutto P., Mangogna A., Bussani R., De Maso L., D’Errico S., et al. Multiple-organ complement deposition on vascular endothelium in COVID-19 patients. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1003. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9081003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfister F., Vonbrunn E., Ries T., Jäck H.M., Überla K., Lochnit G., et al. Complement activation in kidneys of patients with COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.594849. 594849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostrycharz E., Hukowska-Szematowicz B. New insights into the role of the complement system in human viral diseases. Biomolecules. 2022;12:226. doi: 10.3390/biom12020226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang R., Xiao H., Guo R., Li Y., Shen B. The role of C5a in acute lung injury induced by highly pathogenic viral infections. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2015;4 doi: 10.1038/emi.2015.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Y., Lu K., Pfefferle S., Bertram S., Glowacka I., Drosten C., et al. A single asparagine-linked glycosylation site of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein facilitates inhibition by mannose-binding lectin through multiple mechanisms. J Virol. 2010;84:8753–8764. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00554-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laudanski K., Okeke T., Siddiq K., Hajj J., Restrepo M., Gullipalli D., et al. A disturbed balance between blood complement protective factors (FH, ApoE) and common pathway effectors (C5a, TCC) in acute COVID-19 and during convalesce. Sci Rep. 2022;12:13658. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-17011-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Severe Covid-19 GWAS Group, Ellinghaus D., Degenhardt F., Bujanda L., Buti M., Albillos A., et al. Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1522–1534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2020283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J.J., Dong X., Liu G.H., Gao Y.D. Risk and protective factors for COVID-19 morbidity, severity, and mortality. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2022;Jan19:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s12016-022-08921-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Besutti G., Ottone M., Fasano T., Pattacini P., Iotti V., Spaggiari L., et al. The value of computed tomography in assessing the risk of death in COVID-19 patients presenting to the emergency room. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:9164–9175. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-07993-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galli M.G., Djuric O., Besutti G., Ottone M., Amidei L., Bitton L., et al. Clinical and imaging characteristics of patients with COVID-19 predicting hospital readmission after emergency department discharge: a single-Centre cohort study in Italy. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. 2008. http://www.R-project.org ISBN 3-900051-07-0.

- 36.Samprathi M., Jayashree M. Biomarkers in COVID-19: an up-to-date review. Front Pediatr. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.607647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vassallo A., Wood A.J., Subburayalu J., Summers C., Chilvers E.R. The counter-intuitive role of the neutrophil in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Br Med Bull. 2019;131:43–55. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldz024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abers M.S., Delmonte O.M., Ricotta E.E., Fintzi J., Fink D.L., de Jesus A.A.A., et al. An immune-based biomarker signature is associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients. JCI Insight. 2021;6 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.144455. e144455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leatherdale A., Stukas S., Lei V., West H.E., Campbell C.J., Hoiland R.L., et al. Persistently elevated complement alternative pathway biomarkers in COVID-19 correlate with hypoxemia and predict in-hospital mortality. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2022;211:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s00430-021-00725-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali Y.M., Ferrari M., Lynch N.J., Yaseen S., Dudler T., Gragerov S., et al. Lectin pathway mediates complement activation by SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.714511. 714511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niederreiter J., Eck C., Ries T., Hartmann A., Märkl B., Büttner-Herold M., et al. Complement activation via the lectin and alternative pathway in patients with severe COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.835156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu J., Yuan X., Chen H., Chaturvedi S., Braunstein E.M., Brodsky R.A. Direct activation of the alternative complement pathway by SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins is blocked by factor D inhibition. Blood. 2020;136 doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008248. 2080–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boussier J., Yatim N., Marchal A., Hadjadj J., Charbit B., El Sissy C., et al. Severe COVID-19 is associated with hyperactivation of the alternative complement pathway. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.11.004. 550–6.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarlhelt I., Nielsen S.K., Jahn C.X.H., Hansen C.B., Pérez-Alós L., Rosbjerg A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibodies mediate complement and cellular driven inflammation. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.767981. 767981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan B., Freiwald T., Chauss D., Wang L., West E., Mirabelli C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 drives JAK1/2-dependent local complement hyperactivation. Sci Immunol. 2021;6 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abg0833. eabg0833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meroni P.L., Borghi M.O. Antiphospholipid antibodies and COVID-19 thrombotic vasculopathy: one swallow does not make a summer. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1105–1107. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chaturvedi S., Braunstein E.M., Yuan X., Yu J., Alexander A., Chen H., et al. Complement activity and complement regulatory gene mutations are associated with thrombosis in APS and CAPS. Blood. 2020;135:239–251. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delanghe J.R., De Buyzere M.L., Speeckaert M.M. Genetic polymorphisms in the host and COVID-19 infection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1318:109–118. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-63761-3_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valenti L., Griffini S., Lamorte G., Grovetti E., Uceda Renteria S.C., Malvestiti F., et al. Chromosome 3 cluster rs11385942 variant links complement activation with severe COVID-19. J Autoimmun. 2021;117 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102595. 102595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stravalaci M., Pagani I., Paraboschi E.M., Pedotti M., Doni A., Scavello F., et al. Recognition and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 by humoral innate immunity pattern recognition molecules. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:275–286. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01114-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hetland G., Pfeifer P.H., Hugli T.E. Processing of C5a by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:456–462. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.4.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hetland G., Moen O., Bergh K., Högäsen K., Hack C.E., Mollnes T.E., et al. Both plasma- and leukocyte-associated C5a are essential for assessment of C5a generation in vivo. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1076–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)01255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarkar S., Khanna P., Singh A.K. The impact of neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio in COVID-19: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Intensive Care Med. 2022;37:857–869. doi: 10.1177/08850666211045626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.