Abstract

Background

Gyirong Valley known as the “Back Garden of the Himalayas” is located in the core area of the Everest National Nature Reserve. It is also one of the important ports from ancient Tibet to Kathmandu, Nepal, since ancient times. Over the years, the Tibetans of Gyirong had accumulated sufficient traditional knowledge about local plant resources. However, there is almost no comprehensive report available on ethnobotanical knowledge about the local people. The purposes of this study were to (1) conduct a comprehensive study of wild plants used by Tibetan people in Gyirong Valley and record the traditional knowledge associated with wild useful plants, (2) explore the influence of Tibetan traditional culture and economic development on the use of wild plants by local people, and (3) explore the characteristics of traditional knowledge about wild plants of Tibetans in Gyirong.

Methods

Ethnobotanical data were documented through free listings, key informant interviews and semi-structured interviews during fieldwork. The culture importance index and the informant consensus factor index were used as quantitative indices.

Results

In total, 120 informants (61 women and 59 men) and 3333 use reports and 111 wild plant species belonging to 39 families and 81 genera were included. These use reports were then classified into 27 categories belonging to three major categories. The use category that contained the most plant species was edible plants (62), followed by medicinal plants (32) and economic plants (22), and other uses (71). Plants with high CI included Allium prattii, Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora, Gymnadenia orchidis, Rhododendron anthopogon and Fritillaria cirrhosa. Thirty-six species of plants in the catalog of Gyirong and Yadong were the same, but only 17 species were the same in Gyirong and Burang. There were only 11 overlapping species between all the three regions.

Conclusion

Tibetans of Gyirong have rich and unique knowledge about plant use, and wild edible and medicinal plants play an important role in the nutrition and health protection of local people. However, traditional knowledge is slowly being lost and is being hit by modern tourism. In the future, more attention needs to be paid to the important role of traditional knowledge in biodiversity conservation.

Keywords: Himalayas, Biodiversity hotspots, Tibetan, Traditional knowledge, Environmental conservation

Background

Since antiquity, wild plants have been used for food, medicines, fuel and many other purposes [1, 2]. The collection and consumption of wild plants is an important livelihood part of people living in the underdevelopment area [3–10]. Geography and culture influence the way humans choose to use plants in their behavior and knowledge [11]. However, traditional knowledge is also losing due to the loss of traditional culture and conversion of forest ecosystems to other types of land use, which may be completely lost in future development [12, 13]. Therefore, it is important to record and preserve the traditional plant knowledge associated with plants.

China has a long history of using native plants and a large quantity of recorded knowledge on useful plants [14]. Research on traditional knowledge of wild useful plants is very rich in China, especially in the southwest region [15–18]. The studies here have promoted the recording and protection of traditional plant knowledge, resulting in important guiding significance for the future response to climate change and food and medicine shortages [19].

Tibetans are one of the 56 ethnic minorities in China, mainly living in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, with an average altitude of over 4000 m [20, 21]. They have extensive knowledge of wild useful plants [22–26]. As one of the nations living in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau for generations, Tibetans can adapt to the harsh climate on the plateau, which is inseparable from the use of wild plants, while it is still relatively lacking research. Ethnobotanical research on Tibetans in China is mainly concentrated in Yadong and Purang in the Himalayas, Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan in western China [22, 27–33]. As for foreign countries, they are mainly concentrated in Nepal, Bhutan and other regions [32, 34–39]. Compared with the huge distribution range of Tibetans, the scope of research on Tibetans is still very narrow; thus, we need more ethnobotanical researches about Tibetans.

Gyirong Valley, known as the “Back Garden of the Himalayas” is located in the core area of the Everest National Nature Reserve to the south of Shigatse City in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, and the main ethnic group is Tibetan in here [40]. The Gyirong Valley has been an important communication channel between China and South Asian countries since ancient times. It can be said that the Valley has filled half of the history of Tibet [9, 40].

Due to the unique topographical features and history, the Tibetans of Gyirong have accumulated rich traditional knowledge of wild and available plants. This traditional knowledge may have been influenced by Tibetan medicine culture and economic development. The purposes of this study were to (1) conduct a comprehensive study of wild plants used by Tibetan people in Gyirong Valley and record the traditional knowledge associated with wild useful plants, (2) explore the influence of Tibetan traditional culture and economic development on the use of wild plants by local people, and (3) explore the characteristics of traditional knowledge about wild plants of Tibetans in Gyirong.

Method

Study area

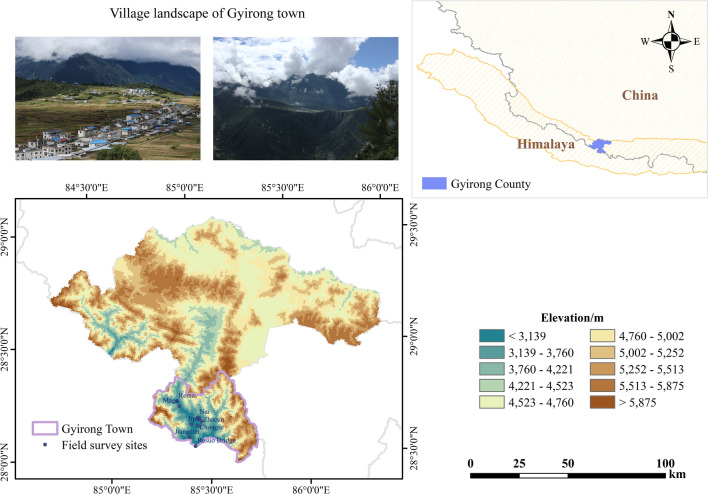

Gyirong Town is located in the southwest of Shigatse City, Tibet Autonomous Region of China, in the core area of Mount Everest Reserve, and adjacent to Nepal in the south (Fig. 1). The average temperature is 10–13 °C, an annual precipitation of 230–370 mm, and more than 200 frost-free days annually. The vegetation types are mainly mountain coniferous forest and mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forest. It is known as the “back garden of the Himalayas” [23, 40, 41].

Fig. 1.

Map showing the location

The traditional trade between China and Nepal has a long history. The Gyirong Valley has been an important communication channel between China and South Asian countries since ancient times. Since the Han and Tang Dynasties, there have been silk trade traffic routes from mainland China through Tibet, Nepal (known as Nibala in ancient times) and India. Among them, Gyirong is one of the important ports from ancient Tibet to Kathmandu, Nepal [42, 43]. Therefore, Indian and Nepalese styles can still be observed in some temple buildings. Until now, the Tibetans of Gyirong Valley still maintain the traditional customs of transnational trade and intermarriage.

Tibetans in Gyirong

Tibetans, one of the 56 ethnic groups in China, are divided into three regions according to dialects, namedas Ü-Tsang, Kham and Amdo. The Tibetans in Gyirong Town belong to the Ü-Tsang dialect area [44]. According to local government reports, the livelihood of the local people is dependent on forests and other natural resources apart from agricultural and animal production. Local Tibetans have rich traditional knowledge, such as handicrafts and medicinal plant knowledge [9, 23, 41]. The traditional production practices of the Gyirong Tibetans are agriculture and grazing. The main crops are Hordeum vulgare, Solanum tuberosum, Fagopyrum tataricum and rapeseed. The traditional diet of the Tibetans in Gyirong is mainly tsampa, dairy products, and butter tea.

Field survey and data collection

The field surveys were conducted between August 2019 and September 2021. Firstly, field study permission was obtained from the local community committee and government authority. Then, we explained our purpose to local governments and requested assistance from them. Because many Tibetans in the study area cannot speak Mandarin fluently, the fieldwork was performed with the assistance of local guides who were employed with the help of local community leaders.

The snowball sampling method was used to select experts who specialize in using plants for healing and make a living using traditional plant knowledge, such as herb dealers, veterinarians and traditional healers. A randomized household interview method was used to select other informants. Data were collected through individual semi-structured interviews conducted from local 120 informants, which constitutes the classic method in ethnobiology (Table 1). All interviews were conducted in the Tibetan language, which was translated into Mandarin by local guides. All field studies were conducted with the consent of informants. The wild useful plants and related traditional knowledge were documented. The following are the questions in the semi-structured interviews:

Would you mind listing some wild plants you have used in the Tibetan language?

How to use these plants, food, medicine, fodder or other purposes?

Which plant parts were used, roots, stems, leaves or other parts?

Why do you use this species?

What time do you collect this plant?

Table 1.

Characteristics of informants

| Characteristics | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Communities | ||

| Chongse | 5 | 4.2% |

| Jiangcun | 9 | 7.5% |

| Jipu | 16 | 13.3% |

| Langjiu | 9 | 7.5% |

| Maga | 20 | 16.7% |

| Nai | 22 | 18.3% |

| Rema | 18 | 15.0% |

| Resuo bridge | 3 | 2.5% |

| Zhacun | 18 | 15.0% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 61 | 50.8% |

| Male | 59 | 49.2% |

| Age | ||

| Below 20 | 5 | 4.2% |

| 20–29 | 12 | 10.0% |

| 30–39 | 19 | 15.8% |

| 40–49 | 27 | 22.5% |

| 50–59 | 26 | 21.7% |

| 60–69 | 21 | 17.5% |

| 70–79 | 7 | 5.8% |

| Above 80 | 3 | 2.5% |

The questions were designed to collect data on the (1) vernacular names of the plants, (2) use categories, (3) used parts, and (4) preparation and administration methods.

The specimens were collected from the field of the survey with the help of the key informants and all materials were labeled with numbers and local names. We use Chinese pinyin to encode local names. Photographs of each plant were taken. All specimens were kept in the herbarium of the Kunming Institute of Botany (KUN). The Flora of China was used to help identify the plants [45], and The Plants of the World Online was used to ensure the Latin name of the plants [46].

Data analysis

We adopted the cultural important index (CII) and the informant consensus factor index (FIC) as ethnobotanical indices. All information about wild used plants was organized into a “use report” list consisting of three parts: informant, plant and use category [47, 48]. The criteria for the use categories of plants mainly refer to The Economic Botany Data Collection Standard (EBDCS) [48].

The cultural important index (CII) was the sum of the proportion of informants that mentioned each of the use categories for a given species [49]. In other words, CII represents the diversity of plant uses and the degree of recognition of information sources for each use category. This index is used to quantitatively evaluate the importance of a certain plant to Tibetan of Gyirong from the perspective of comprehensive value.

The calculation formula is as follows:

NC is the total number of use categories and N is the total number of informants. CII ranges between 0 and the number of all use categories, and the index is greater than 1 if the number of mentions of the plant is greater than the total number of informants. A higher CII value indicated the multiple uses of a species and a higher degree of recognition

The informant consensus factor index (FIC) was developed by Trotter [50]. FIC was used to evaluate the degree of consensus among the population about how to treat a particular disease. The calculation formula is as follows:

where Nur is the number of use reports from the informants for a particular disease and Nt is the total number of plant species used to treat the disease. The FIC values range between 0 and 1. A higher FIC means that different herbalists have a higher consensus on the plant species used for certain use categories.

Results

The diversity of wild plants used by locals

Tibetan people living in Gyirong Valley use a variety of wild plants. A total of 111 wild plant species, including scientific names, vernacular names, usage, used part, the number of UR and CII. All the information of these plants is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of plants used by the Tibetan people in Gyirong

| Botanical taxon | Botanical family | Local name(s) | Voucher | Parts used | Local use (No. of URs) and preparation | UR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chenopodium album L | Amaranthaceae | Lei1; niu1; niu1-che1-ma1 | QTB-JL-42 | Leaves | Food: vegetable (14), used to make bun or fry | 14 | 0.111 |

| Allium chrysanthum Regel | Amaryllidaceae | Guo1-ba1 | QTB-JL-21 | Roots | Food: vegetable (20), used to make bun or fry; seasoning (7), cook it with pork and potatoes | 27 | 0.214 |

| Allium fasciculatum Rendle | Amaryllidaceae | Ou1-ga1 | QTP-EBT-3050 | Aerial parts | Food: vegetable (10), used to make bun or fry; seasoning (7), cook it with pork and potatoes | 17 | 0.135 |

| Allium prattii C.H.Wright | Amaryllidaceae | Ru1-ba1; ri1-guo1 | QTP-EBT-3009 | Aerial parts | Food: vegetable (126), used to make bun or fry; seasoning (9), cook it with pork and potatoes | 141 | 1.119 |

| Allium przewalskianum Regel | Amaryllidaceae | Ri1-guo1; zen1-bu1 | QTP-EBT-3200 | Leaves | Food: seasoning (19), as part of the dip; economic (1), be sold in stores | 20 | 0.159 |

| Allium wallichii Kunth | Amaryllidaceae | Ru1-guo1 | QTB-JL-55 | Aerial parts | Food: seasoning (6), cook it with pork and potatoes or as part of the dip | 6 | 0.048 |

| Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels | Apiaceae | Dang1-gui1 | QTB-JL-41 | Roots | Medicine: tonic (3), cook it with meat | 3 | 0.024 |

| Carum carvi L | Apiaceae | Guo1-nie1 | QTB-JL-63 | Leaves; seeds | Food: vegetable (25), the leaves are cooked with other ingredients; seasoning (35), use seeds to make a dip or a sausage; medicine: gastralgia (5), seed soak in water | 65 | 0.516 |

| Chaerophyllum villosum Wall. ex DC | Apiaceae | Da1-ga1-li1 | QTB-JL-20 | Leaves | Economic (3), be sold in stores; food: seasoning (1), cook its leaves with meat; fodder (1): the leaves are used to feed cattle | 5 | 0.040 |

| Heracleum candicans Wall. ex DC | Apiaceae | Jiong4-wa1-dong1-bu4 | QTB-JL-43 | Aerial parts | Medicine: headache (1); soak in water | 1 | 0.008 |

| Aralia sp. | Araliaceae | Jia1-ra3-cei3-ma1 | QTB-JPG-10 | Leaves | Food: vegetable (2), cook vegetable | 2 | 0.016 |

| Aralia tibetana G.Hoo | Araliaceae | Dai1-ga1-ni1 | QTB-JL-46 | Whole plant | Fodder (5): the leaves are used to feed cattle | 5 | 0.040 |

| Panax pseudoginseng Wall | Araliaceae | San1-jing1 | QTP-EBT-3084 | Roots | Medicine: tonic (30), soak in water; economic (25): be sold in stores | 55 | 0.437 |

| Polygonatum cirrhifolium (Wall.) Royle | Asparagaceae | ra3-mu1-xia3-jia1 | QTB-JL-1 | Aerial parts; roots | Food: vegetable (26), cook vegetable; economic (8), be sold in store; medicine: nephropathy (11), roots soak in water or make soup | 35 | 0.278 |

| Polygonatum sibiricum Redouté | Asparagaceae | Rang3-ma1-xia-jia1 | QTB-JL-26 | Roots; aerial parts | Medicine: tonic (15), roots soak in water or make soup; food: vegetable (45), cook vegetable; economic (12), be sold in store; fodder (3): used to feed cattle | 75 | 0.595 |

| Artemisia calophylla Pamp | Asteraceae | Bang1-ma1 | QTB-JL-50 | Aerial parts | Ritual use (4), used to burn in incense burner; medicine: rheumatism (72): used it to sweat steaming or leaves soak in water to drink | 76 | 0.603 |

| Artemisia japonica Thunb | Asteraceae | Kang1-ba1 | QTB-JL-59 | Aerial parts | Ritual use (60), used to burn in incense burner; medicine: detoxification (23), soak in water; economic (4): be sold in store | 87 | 0.690 |

| Artemisia younghusbandii J. R. Drumm. ex Pamp | Asteraceae | Sang1-kang3-ba1 | QTB-JL-49 | Aerial parts | Ritual use (4), used to burn in incense burner; medicine: rheumatism (4), used it to sweat steaming or leaves soak in water to drink | 8 | 0.063 |

| Galinsoga parviflora Cav | Asteraceae | Cuo1-ma1 | QTP-JPG-6 | Whole plants | Fodder (1): used to feed cattle | 1 | 0.008 |

| Leontopodium souliei Beauverd | Asteraceae | Ba1-wa1 | EBT-PL-99 | Leaves | Tool (2), used it to start a fire | 2 | 0.016 |

| Saussurea tridactyla Sch.Bip. ex Hook.f | Asteraceae | Gang3-la1-mei3-duo3 | QTB-JL-66 | Whole plants | Economic (36), be sold in store; medicine: arthrophlogosis (46): soaked in water | 82 | 0.651 |

| Taraxacum sikkimense Hand.-Mazz | Asteraceae | se4-ji4-mei3-duo3 | QTB-JL-110 | Whole plant | Medicine: endocrine (3), soaked in water; economic (2), be sold in store | 5 | 0.040 |

| Impatiens bicornuta Wall | Balsaminaceae | Po1-zi1 | QTB-JL-73 | Seeds | Varnish (12), used to polish furniture | 12 | 0.095 |

| Impatiens falcifer Hook.f | Balsaminaceae | Po1-zi1 | QTB-JL-15 | Seeds | Varnish (14), used to polish furniture | 14 | 0.111 |

| Impatiens scabrida DC | Balsaminaceae | Po1-zi1 | QTB-JL-70 | Seeds | Varnish (13), used to polish furniture | 13 | 0.103 |

| Impatiens sulcata Wall | Balsaminaceae | Po1-zi1 | QTB-JL-62 | Seeds | Varnish (11), used to polish furniture | 11 | 0.087 |

| Berberis angulosa Wall. ex Hook.f. & Thomson | Berberidaceae | jiu1-bo1; jiu1-le1-bu1 | QTB-JL-113 | Leaves; fruits; branches | Medicine: diarrhea (1), soaked in water; food: fruit (7), raw; fuelwood (2): used to burn | 10 | 0.079 |

| Berberis aristata DC | Berberidaceae | jiu1-lu1-xin1 | QTB-JL-28 | Fruits; branches | Fuelwood (3), used to burn; food: fruit (2), raw | 5 | 0.040 |

| Berberis xanthophlaea Ahrendt | Berberidaceae | giu1-lu1; giu1-le1-bu1; gei1-lu1-mi3-xia4 | QTB-JL-27 | Barks; fruits | Dyes (10), used to dye wool yellow; food: fruit (4), raw | 14 | 0.111 |

| Stauntonia angustifolia (Wall.) R.Br. ex Wall | Berberidaceae | pa1-ji1 | QTP-JPG-2 | Fruits | Food: fruit (2), raw | 2 | 0.016 |

| Betula utilis D.Don | Betulaceae | da4-ge1-ba1 | QTB-JL-7 | Burls; branches; stems | Medicine: diabetes (8), soak in water; economic (2), be sold in store; fuelwood (14), used to burn; craft (7), used to make Tibetan traditional wooden bowls; ritual use (8), used to burn in incense burner; tool (6), used to make cooking utensils | 37 | 0.294 |

| Onosma hookeri C.B. Clarke | Boraginaceae | Guo1-mu1-mu1-zi1 | QTP-EBT-3052 | Roots | Medicine: hair follicle (4), soaked in canola oil and apply to the head; eczema (4); ritual use (7), used to burn in incense burner; economic (1), be sold in store | 16 | 0.127 |

| Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik | Brassicaceae | Du1-yang1 | QTB-JL-34 | Aerial parts | Food: vegetable (8), cooked vegetable | 8 | 0.063 |

| Thlaspi arvense L | Brassicaceae | Mang3-ru1 | QTB-JL-35 | Leaves | Food: vegetable (10), cooked vegetable | 10 | 0.079 |

| Cannabis sativa L | Cannabaceae | Si1-ma1 | QTB-JL-78 | Barks | Tool (8); fodder (4), used to feed cattle | 12 | 0.095 |

| Dipsacus asper Wall. ex C.B. Clarke | Caprifoliaceae | Lang1-zhu1-ma1 | QTP-EBT-3053 | Aerial parts | Fodder (1), used to feed cattle | 1 | 0.008 |

| Lonicera sp. | Caprifoliaceae | se4-le4-qin1-mei3-duo3 | EBT-PL-42 | Flowers | Economic (2), be sold in store | 2 | 0.016 |

| Nardostachys jatamansi (D.Don) DC | Caprifoliaceae | Bang1-bu4 | QTB-JL-123 | Roots | Ritual use (87), used to burn in incense burner; economic (1), be sold in store; medicine: relieving cough and asthma (4), soaked in water | 92 | 0.730 |

| Coriaria terminalis Hemsl | Coriariaceae | da1-lu1 | QTP-EBT-3005 | Fruits | Food: fruit (1), raw | 1 | 0.008 |

| Rhodiola himalensis (D. Don) S.H. Fu | Crassulaceae | suo3-la1-ma3-bu4 | QTB-JL-124 | Stems | Medicine: tonic (20), hypertension (28), soaked in water; economic (19), be sold in store; ritual use (3), used to burn in incense burner | 70 | 0.556 |

| Cyclanthera pedata (L.) Schrad | Cucurbitaceae | ra3-ru1 | QTB-JPG-12 | Fruits | Food: vegetable (7), cooked vegetable | 7 | 0.056 |

| Herpetospermum pedunculosum (Ser.) C.B. Clarke | Cucurbitaceae | sei1-lei1; sei1-lei1-mei3-duo3 | QTB-JL-22 | Flowers; fruits | Medicine: diarrhea (12), powder; veterinary medicine: diarrhea (3), powder | 15 | 0.119 |

| Solena heterophylla Lour | Cucurbitaceae | ma1-ma1-dong4-cei1 | QTB-JL-80 | Fruits | Food: fruit (6), raw | 6 | 0.048 |

| Trichosanthes lepiniana (Naudin) Cogn | Cucurbitaceae | ka1-ge1-di1 | QTB-JL-24 | Seeds | Medicine: fever (1), poder; economic (1), be sold in store | 2 | 0.016 |

| Juniperus indica Bertol | Cupressaceae | xiu1-bai1 | QTB-JL-57 | Branches; stems | Ritual use (67), used to burn in incense burner; fuelwood (7), used to burn; craft (6) | 80 | 0.635 |

| Juniperus tibetica Kom | Cupressaceae | xiu1-bo1 | QTB-JL-64 | Branches; stems | Ritual use (38), used to burn in incense burner; fuelwood (22), used to burn; craft (20), used to make Tibetan traditional wooden bowls; food: fruit (2), raw | 82 | 0.651 |

| Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum (Desv.) Underw. ex A. Heller | Dennstaedtiaceae | da1; da1-gu1; dai1-ga1; da1-li1 | QTB-JL-10 | Leaves | Food: cooked vegetable (86) | 86 | 0.683 |

| Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb | Elaeagnaceae | ra1-lu1 | QTB-JL-18 | Fruits | Food: fruit (43), raw | 43 | 0.341 |

| Hippophae salicifolia D.Don | Elaeagnaceae | da1-ru1 | QTB-JL-16 | Fruits; branches | Food: fruit (21), raw; seasoning (14), fruit juice is used as a substitute for vinegar; medicine: arthrophlogosis (3), the juice is used to smear the joints; fuelwood (1), used to burn | 39 | 0.310 |

| Rhododendron anthopogon D. Don | Ericaceae | po1-lu1 | QTB-JL-115 | Branches; flowers | Ritual use (91), used to burn in incense burner; fuelwood (1), used to burn; medicine: eyes ache (4), arthrophlogosis (4), flowers are used to soak water; beverage (6), soak in water; economic (4), be sold in store | 110 | 0.873 |

| Rhododendron arboreum Sm | Ericaceae | mei3-duo1 | QTB-JL-30 | Branches; stems | Fuelwood (7), used to burn; craft (9), used to make Tibetan traditional wooden bowls | 16 | 0.127 |

| Rhododendron lepidotum Wall. ex G. Don | Ericaceae | su1-lu1 | QTB-JL-114 | Branches | Ritual use (15), used to burn incense burner | 15 | 0.119 |

| Euphorbia micractina Boiss | Euphorbiaceae | ta3-lu1-ma1 | QTB-JL-85 | Leaves | Medicine: poisons (2) | 2 | 0.016 |

| Cicer microphyllum Benth | Fabaceae | pu3-gui3 | EBT-PL-13 | Fruits | Food: fruit (2), raw | 2 | 0.016 |

| Quercus semecarpifolia Sm | Fagaceae | bai1-luo4 | QTB-JL-25 | Stems; branches; leaves | Ritual use (2), used to burn in incense burner; craft (15), used to make Tibetan traditional wooden bowls; fuelwood (48); fodder (5), used to feed cattle; food: starch (4), cooked fruit | 74 | 0.587 |

| Gentiana veitchiorum Hemsl | Gentianaceae | bang1-jie1-mei3-duo3 | QTP-EBT-3024 | Whole plant | Medicine: fever (18), soaked in water | 18 | 0.143 |

| Swertia cordata (Wall. ex G. Don) C.B. Clarke | Gentianaceae | di1-ge1-da1 | QTP-EBT-3111 | Aerial parts | Medicine: fever (10), soak in water; economic (2); veterinary medicine (1), soak in water | 13 | 0.103 |

| Isoetes hypsophila Hand.-Mazz | Isoetaceae | pa1-xia4 | QTP-JPG-3 | Leaves | Food: vegetable (25), cooked vegetable | 25 | 0.198 |

| Juglans regia L | Juglandaceae | da1-ba1 | QTB-JL-88 | Fruits; stems; branches | Dyes (23), pericarp used to dye the container black; ritual use (9), used to burn in incense burner; food: fruit (9), raw; craft (30), used to make Tibetan traditional wooden bowls; fuelwood (12), used to burn | 83 | 0.659 |

| Elsholtzia fruticosa (D.Don) Rehder | Lamiaceae | ma1-zei1 | QTB-JL-48 | Aerial parts | Ritual use (12), used to burn in incense burner; fuelwood (5), used to burn | 17 | 0.135 |

| Nepeta densiflora Kar. & Kir | Lamiaceae | pi1-ba4 | QTP-EBT-3060 | Aerial parts | Fodder (3), used to feed cattle | 3 | 0.024 |

| Fritillaria cirrhosa D.Don | Liliaceae | bai1-mu4 | QTP-EBT-3012 | Bulbs | Medicine: tonic (40), stew or soak in water; cold (20); economic (45), be sold in store; veterinary medicine (1), soak in water; food: fruit (2), raw | 108 | 0.857 |

| Malva verticillata L | Malvaceae | jiang4-ba1-la1-mu1 | QTB-JL-36 | Roots; leaves | Food: vegetable (25), cooked vegetable | 25 | 0.198 |

| Paris polyphylla Sm | Melanthiaceae | bo1-luo3 | QTP-EBT-3085 | Arieal parts | Ritual use (11), used to burn in incense burner; medicine: stomachache, soaked in water or wine (10); economic (2), be sold in store; vegetable (28), cooked vegetable | 51 | 0.405 |

| Gastrodia elata Blume | Orchidaceae | tian3-ma3 | QTP-JPG-3292 | Roots | Economic (29), be sold in store; medicine: headache (6), cardiopathy (40), slice and soak in water or stew; food: vegetable (2), used to make soup with chicken | 77 | 0.611 |

| Gymnadenia orchidis Lindl | Orchidaceae | wang1-bu1-la1-ba1 | QTB-JL-56 | Roots | Medicine: pulmonary disease (5), soak in water or wine; burn (32), acne (38), used to daub affected area; economic (31); ritual use (10), raw materials for making Tibetan incense | 116 | 0.921 |

| Phytolacca acinosa Roxb | Phytolaccaceae | Wo1-yang1 | QTB-JL-84 | Leaves | Food: vegetable (13), cooked vegetable | 13 | 0.103 |

| Larix potaninii var. himalaica (W.C.Cheng & L.K.Fu) Farjon & Silba | Pinaceae | Long3-xin1 | QTP-JPG-7 | Branches; stems | Fuelwood (4), used to burn; craft (9), used to make Tibetan traditional wooden bowls | 13 | 0.103 |

| Pinus wallichiana A.B.Jacks | Pinaceae | Nong1-xin1; tang3-xin1 | QTB-JL-39 | Branches; stems | Fuelwood (44), used to burn; craft (7), used to make Tibetan traditional wooden bowls; ritual use (11), used to burn in incense burner; food: vegetable (7), cooked vegetable | 73 | 0.579 |

| Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora (Pennell) D.Y.Hong | Plantaginaceae | di1-da1; hong1-lei1 | QTB-JL-67 | Roots | Medicine: cold and fever (107), soaked in water; economic (18), be sold in store; veterinary medicine: fever (3), soak in water | 128 | 1.016 |

| Plantago asiatica L | Plantaginaceae | wo1-ma1-ka1 | QTP-EBT-3117 | Aerial parts | Medicine: hypertension (4), soaked in water; food: vegetable (3), cooked vegetable | 7 | 0.056 |

| Plantago asiatica subsp. densiflora (J.Z.Liu) Z.Y.Li | Plantaginaceae | ou3-ma1-ka3 | QTB-JL-12 | Leaves; roots | Medicine: hypertension (2), soaked in water; food: vegetable (3), cooked vegetable | 5 | 0.040 |

| Avena fatua L | Poaceae | sei1-za1-ba1 | QTB-JPG-11 | Aerial parts | Fodder (1), used to feed cattle | 1 | 0.008 |

| Fargesia sp. | Poaceae | niu1-dong1 | QTB-JL-118 | Stems | Economic (1), be sold in store; food: vegetable (66), cooked vegetable; craft (19), used to make bamboo plaits; ritual use (6), used to burn in incense burner; fuelwood (2), used to burn; fodder (7), used to feed cattle | 101 | 0.802 |

| Poaceae sp. | Poaceae | zang4-ong1-bu4 | QTP-JPG-8 | Whole plant | Fodder (7), used to feed cattle | 7 | 0.056 |

| Fagopyrum esculentum Moench | Polygonaceae | bai1-bi1-ya1 | QTB-JL-60 | Arieal parts | Fodder (3), used to feed cattle | 3 | 0.024 |

| Fallopia denticulata (C.C.Huang) Holub | Polygonaceae | a1-lang1-ba1-lang1 | QTB-JL-122 | Aerial parts; roots | Fodder (2), used to feed cattle; medicine: diarrhea (5), hair follicle (2), soak in water | 9 | 0.071 |

| Koenigia tortuosa (D.Don) T.M.Schust. & Reveal | Polygonaceae | nia1-luo1 | QTB-JL-4 | Aerial parts; stems | Dye (6), used to dye wooden bowls or clothes yellow; fodder (8), used to feed cattle; food: fruit (4), raw | 18 | 0.143 |

| Pteroxygonum denticulatum (C.C.Huang) T.M.Schust. & Reveal | Polygonaceae | ren3-bu1 | QTB-JL-45 | Aerial parts | Fodder (2), used to feed cattle | 2 | 0.016 |

| Rheum australe D. Don | Polygonaceae | qu1-wa1; jiong1 | QTB-JL-3 | Stems; roots | Fruit (17), raw eat tender stem; dye (53), used to dye wooden bowls or clothes yellow | 70 | 0.556 |

| Rumex nepalensis Spreng | Polygonaceae | xiu1-ma1 | EBT-PL-86 | Aerial parts | Fodder (2), used to feed cattle | 2 | 0.016 |

| Aconitum jilongense W.T.Wang & L.Q.Li | Ranunculaceae | beng3-ga1 | QTB-JPG-1 | Roots | Medicine: diarrhea (24), soak in water | 24 | 0.190 |

| Clematis rehderiana Craib | Ranunculaceae | ba1-ji1-ma1 | EBT-PL-84 | Leaves | Food: vegetable (2), cooked vegetable | 2 | 0.016 |

| Delphinium kamaonense Huth | Ranunculaceae | jia1-bei1-mei1-duo1 | QTB-JL-37 | Aerial parts | Fodder (1), used to feed cattle | 1 | 0.008 |

| Eriocapitella rivularis (Buch.-Ham. ex DC.) Christenh. & Byng | Ranunculaceae | cei1-di1-ma1 | QTB-JPG-9 | Aerial parts | Fodder (1), used to feed cattle | 1 | 0.008 |

| Gymnaconitum gymnandrum (Maxim.) Wei Wang & Z.D.Chen | Ranunculaceae | zen1-du1; du3-wa1-ten3-du1 | QTP-EBT-3097 | Roots | Medicine: poisons (16), rheumatism (16), soaked in water and apply to the affected area; economic (4), be sold in store | 36 | 0.286 |

| Berchemia flavescens (Wall.) Wall. ex Brongn | Rhamnaceae | bo1-ge1-da4 | QTB-JL-93 | Fruits | Food: fruit (45), raw | 45 | 0.357 |

| Argentina anserina (L.) Rydb | Rosaceae | chu1-ma1 | QTP-EBT-3055 | Roots | Food: starch (60), cooked and eat with yogurt or rice | 60 | 0.476 |

| Chaenomeles thibetica T.T.Yu | Rosaceae | bai1-la1 | QTB-JL-109 | Fruits | Food: fruit (19), raw; fuelwood (3), used to burn | 22 | 0.175 |

| Fragaria nubicola (Lindl. ex Hook.f.) Lacaita | Rosaceae | long1-mei1; sei1-duo1-zhe3-xin1 | QTB-JL-9 | Fruits; stems | Fruit (83), raw; ritual use (3), used to burn in incense burner | 86 | 0.683 |

| Griffitharia vestita (Wall. ex G.Don) Rushforth | Rosaceae | na1-zi1 | QTB-JL-5 | Fruits; branches | Food: fruit (55), raw; fuelwood (1), used to burn; ritual use (2), used to burn in incense burner | 58 | 0.460 |

| Prinsepia utilis Royle | Rosaceae | bu1-long1-che4-mang1 | QTB-JL-38 | Seeds | Economic (9), be sold in store | 9 | 0.071 |

| Prunus holosericea (Batal.) Kost | Rosaceae | a1-lu1-ba3-lu1 | QTB-JL-91 | Fruits | Food: fruit (6), raw | 6 | 0.048 |

| Prunus mira Koehne | Rosaceae | kang3-bu4 | QTB-JL-69 | Fruits | Food: fruit (53), raw | 53 | 0.421 |

| Rosa macrophylla Lindl | Rosaceae | sei1-duo1 | QTB-JL-29 | Branches; fruits | Fuelwood (3), used to burn; food: fruit (11), raw | 14 | 0.111 |

| Rosa sericea Lindl | Rosaceae | gu1-jiu1-ma1; gun1-zhong1 | QTB-JL-17 | Fruits; branches | Food: fruit (91), raw; fuelwood (1), used to burn; medicine: digestion (1), raw | 94 | 0.746 |

| Rubus aurantiacus Focke ex Sarg | Rosaceae | ni1-na1 | QTB-JL-14 | Fruits | Food: fruit (6), raw | 6 | 0.048 |

| Rubus austrotibetanus T.T.Yu & L.T.Lu | Rosaceae | nia1-lang1 | QTB-JL-82 | Fruits | Food: fruit (55), raw | 55 | 0.437 |

| Rubus biflorus Buch.-Ham. ex Sm | Rosaceae | nie1-sen1; nia1-lang1 | QTB-JL-83 | Fruits | Food: fruit (9), raw | 9 | 0.071 |

| Rubus niveus Thunb | Rosaceae | nia1-lang2 | QTB-JL-13 | Fruits | Food: fruit (68), raw | 68 | 0.540 |

| Thomsonaria ochracea (Hand.-Mazz.) Rushforth | Rosaceae | ca1-le1-ba1 | QTB-JL-92 | Branches | Fuelwood (17), used to burn; tool (3), used to make handle; ritual use (1), used to burn in incense burner | 21 | 0.167 |

| Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim | Rutaceae | ei1-ma1 | QTB-JL-8 | Fruits; seeds | Food: seasoning (83), vegetable (14), cooked it with meat; economic (3), be sold in store; medicine: endocrine (3), raw or soak in water; fuelwood (1), used to burn | 104 | 0.825 |

| Salix babylonica f. babylonica | Salicaceae | jiang1-ma1 | QTB-JL-108 | Branches | Fodder (5), used to feed cattle; fuelwood (3), used to burn; ritual use (3), used to burn in incense burner | 11 | 0.087 |

| Salix trichocarpa C.F. Fang | Salicaceae | lang1-ma1 | QTB-JL-47 | Branches; flowers; stems | Fuelwood (15), used to burn; ritual use (14), used to burn in incense burner; fodder (1), used to feed cattle; craft (3), used to make wooden bowl; food: vegetable (2), flower buds can be fried and eaten | 35 | 0.278 |

| Schisandra elongata (Blume) Baill | Schisandraceae | gong1-zhu1 | QTB-JL-117 | Fruits | Food: fruit (7), raw | 7 | 0.056 |

| Tamarix chinensis Lour | Tamaricaceae | ong1-bu4 | QTB-JL-18 | Branches | Ritual use (1), burned to sacrifice to the dead | 1 | 0.008 |

| Taxus wallichiana Zucc | Taxaceae | sei1-ge1-xia4 | QTB-JL-31 | Branches; fruits | Fuelwood (11), used to burn; food: fruit (5), raw | 16 | 0.127 |

| Urtica ardens Link | Urticaceae | suo3-wa1 | QTP-JPG-5 | Leaves | Food: vegetable (36), cooked vegetable | 36 | 0.286 |

| Urtica urens L | Urticaceae | suo3-wa1 | QTP-JPG-4 | Leaves | Food: vegetable (23), cooked vegetable | 23 | 0.183 |

| Viburnum cotinifolium D. Don | Viburnaceae | gei1-jiu1-ma1 | QTB-JL-51 | Fruits | Food: fruit (4), raw | 4 | 0.032 |

| Viburnum nervosum D. Don | Viburnaceae | ka3-la1-suo1 | QTB-JL-102 | Fruits | Food: fruit (6), raw | 6 | 0.048 |

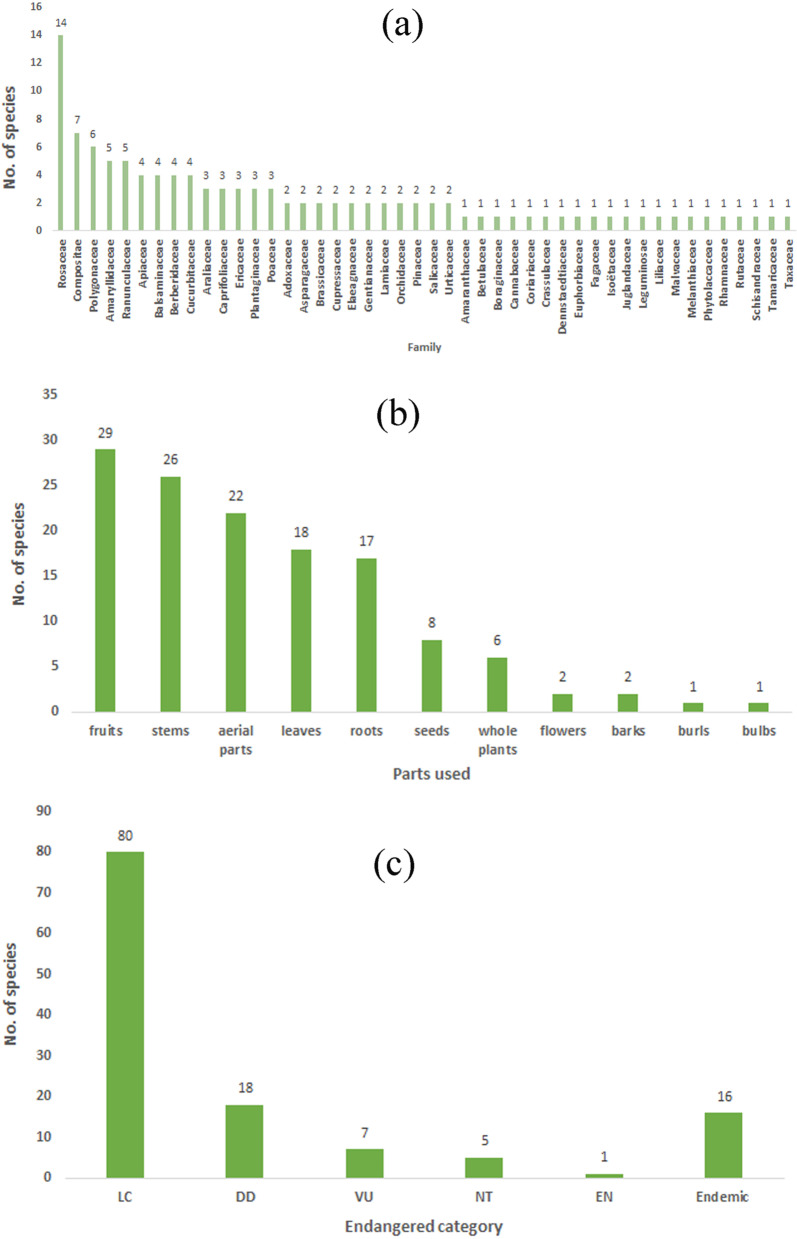

The taxonomic types of wild plants used by Tibetan people included angiosperms (104 species), gymnosperms (5) and ferns (2). These plants belong to 39 families and 81 genera. Rosaceae (14) was the most represented family, followed by Compositae (7) and Polygonaceae (6) (Fig. 2a). The life forms of these plants are mostly herbs (64), followed by trees (19), shrubs (19) and vines (8).

Fig. 2.

Diversity of wild plants used by locals. a diversity of families; b diversity of used parts; c threatened species, LC = least concerned, DD = data deficient, VU = vulnerable, NT = near-threatened, EN = endangered

The use parts are diverse, including fruits, roots, leaves, stems, whole plants, aerial parts, bulbs, barks, seeds, pericarps and tubers. The most used parts are fruits (29 species), followed by stems (25) and roots (17) (Fig. 2b).

Among all wild useful plants, there are 13 endangered plant species, of which Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora is endangered (EN) level. Seven species are vulnerable (VU) levels. Five species are near-threatened (NT) levels. Among these 13 species, three species are economic plants, and the others were edible and medicinal plants. In addition, there are 16 species endemic to China among all useful plants [51] (Fig. 2c).

The diversity of wild edible plants

Wild edible plants (WEPs) were the most frequently used in all categories with 62 edible species belonging to 33 families, and the main used parts of WEPs are fruits and stems. The use categories of WEPs include fruits, vegetables, seasonings, food substitutes and tea substitutes (Table 3). Among these, fruit is the most frequently used (30 species), followed by wild vegetables (27). The most frequently reported species were Allium prattii (135), followed by Zanthoxylum bungeanum (97), Rosa sericea (91), Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum (86) and Fragaria nubicola (83) (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Use categories

| Local use | Secondary use categories | Ns | URs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edible plants | 62 | 1533 | |

| Fruits | 30 | 617 | |

| Seasonings | 9 | 173 | |

| Vegetables | 27 | 677 | |

| Beverages | 1 | 6 | |

| Starches | 1 | 60 | |

| Medicinal plants | 32 | 614 | |

| Poison | 2 | 18 | |

| Inflammation | 1 | 32 | |

| Poisonings | 1 | 23 | |

| Infections | 2 | 11 | |

| Digestive system disorders | 7 | 53 | |

| Respiratory system disorders | 4 | 134 | |

| Nutritional disorders | 5 | 108 | |

| Endocrine system disorders | 2 | 6 | |

| Muscular–skeletal system disorders | 5 | 142 | |

| Genitourinary system disorders | 2 | 19 | |

| Skin disorders | 4 | 48 | |

| Veterinary medicine | 4 | 8 | |

| Nervous system disorders | 2 | 7 | |

| Circulatory system disorders | 4 | 74 | |

| Eyes | 1 | 4 | |

| Economic plants | Improve livelihoods | 22 | 261 |

| Other use | 69 | 1037 | |

| Tools | 5 | 21 | |

| Crafts | 10 | 123 | |

| Dyes | 4 | 87 | |

| Fodders | 20 | 63 | |

| Fuelwoods | 19 | 215 | |

| Ritual plants | 24 | 528 |

Fig. 3.

The most frequently reported edible plants a Allium prattii; b Zanthoxylum bungeanum; c Rosa sericea; d Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum; e Fragaria nubicola

The diversity of wild medicinal plants and evaluation of medicinal plants based on FIC

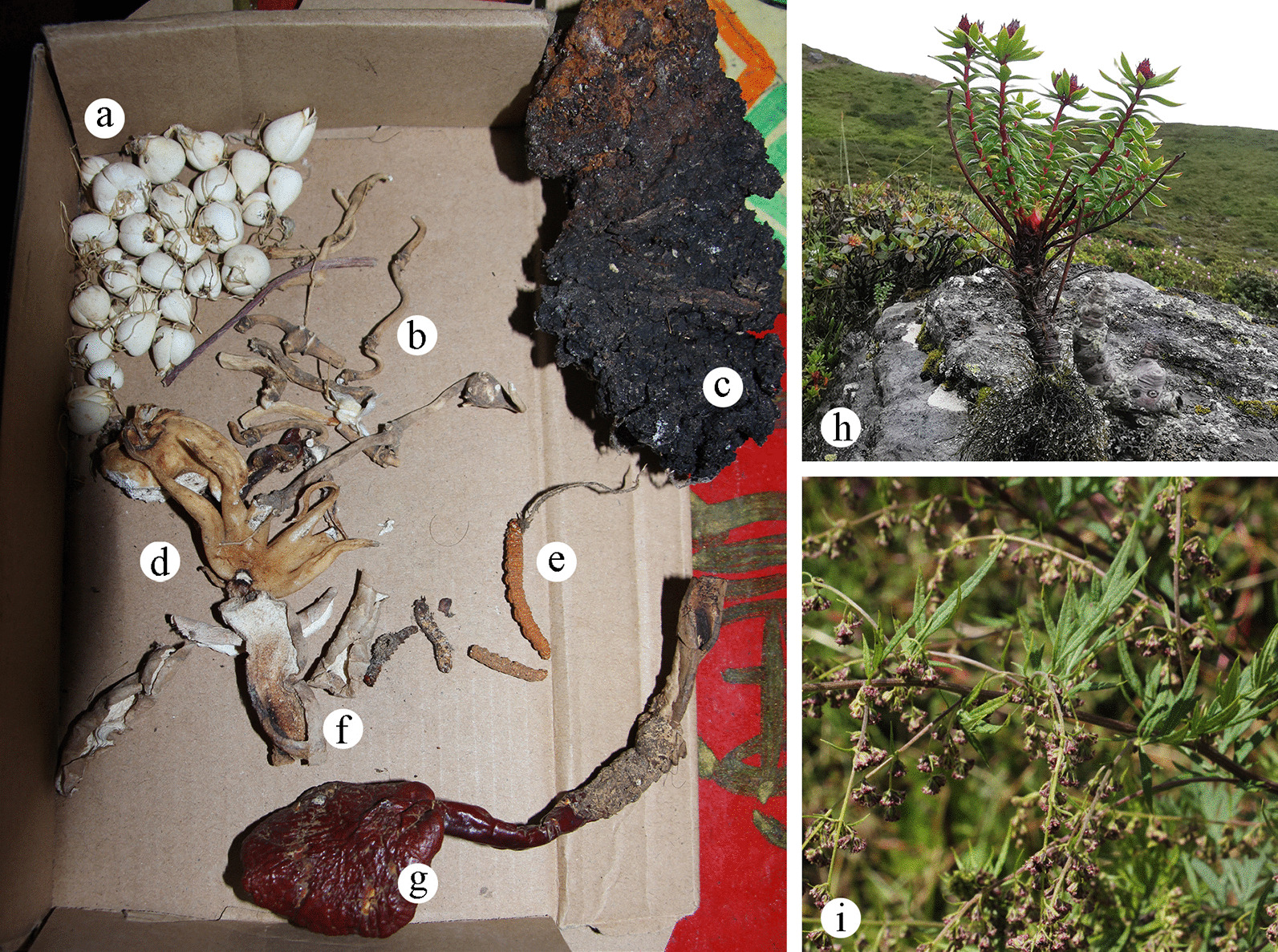

Wild medicinal plants are the second largest category of wild plants used by the Tibetan people of Gyirong town. These plants belong to 22 families and have been documented to treat 15 different types of human diseases. The most frequently mentioned were muscular–skeletal system disorders, followed by respiratory system disorders (Table 3). The family with the most species was Compositae (5 species). The main medicinal parts were roots. The most frequently reported species were Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora (107 use reports), followed by Gymnadenia orchidis (75), Artemisia calophylla (72), Fritillaria cirrhosa (61), Rhodiola himalensis (48) and Gastrodia elata (46) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Some medicinal plants in the study area. a Fritillaria cirrhosa; b Panax pseudoginseng; c Betula utilis; d Gymnadenia orchidis; e Ophiocordyceps sp.; f Gastrodia elata; g Ganoderma sp.; h Rhodiola himalensis; i Artemisia calophylla

The FIC results for the 27 use categories ranged from 0.5714 to 0.9774, and the values of the FIC were the highest for respiratory system disorders (0.9774), followed by muscular–skeletal system disorders (0.9716), and the lowest for veterinary medicine (0.5714), followed by endocrine system disorders (0.8000) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Evaluation of medicinal plants based on FIC

| Categories of diseases | FIC |

|---|---|

| Poison | 0.9412 |

| Inflammation | – |

| Poisonings | – |

| Infections | 0.9000 |

| Digestive system disorders | 0.8846 |

| Respiratory system disorders | 0.9774 |

| Nutritional disorders | 0.9626 |

| Endocrine system disorders | 0.8000 |

| Muscular–skeletal system disorders | 0.9716 |

| Genitourinary system disorders | 0.9444 |

| Skin disorders | 0.9362 |

| Veterinary medicine | 0.5714 |

| Nervous system disorders | 0.8333 |

| Circulatory system disorders | 0.9589 |

| Eyes | – |

Wild economic plants

A total of 22 wild plants were used as economic plants (Table 3), and the most frequently reported species were Fritillaria cirrhosa. Wild economic plants are an important source of local income (Fig. 5a). A variety of economic plants are sold in local shops (Table 5). In addition to plants, there are Cordyceps sp. and wild Ganoderma sp. (Table 5).

Fig. 5.

Other use categories. a some economic plants are sold in shops; b some plants used to “Sang”; c fodder plants; d fuelwoods

Table 5.

A price list from a shop in Gyirong

| Botanical taxon | Local name(s) | Parts | Price (RMB/500 g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim | ei1-ma1 | Fruits | 50/500 g |

| Allium przewalskianum Regel | zen1-bu1 | Leaves | 50/500 g |

| Gastrodia elata Blume | tian3-ma3 | Roots | 1200/500 g |

| Polygonatum sibiricum F.Delaroche | rang3-ma1-xia-jia1 | Roots | 190/500 g |

| Gymnadenia orchidis Lindl | wang1-bu1-la1-ba1 | Roots | 500/500 g |

| Rhodiola himalensis (D. Don) S.H. Fu | suo3-la1-ma3-bu4 | Roots | 150–750/500 g |

| Fritillaria cirrhosa D.Don | bai1-mu4 | Bulbs | 700–1000/500 g |

| Rhododendron anthopogon D. Don | po1-lu1 | Flowers | 50/500 g |

| Pinus wallichiana A.B.Jacks | tang3-xin1 | Pollen | 500/500 g |

| Carum carvi L | guo1-nie1 | Seeds | 50/500 g |

| Taraxacum sikkimense Hand.-Mazz | se4-ji4-mei3-duo3 | Whole plant | 80/500 g |

| Solanum tuberosum L | a3-lou3 | Tuber | 25/500 g |

| Capsicum annuum L | ku1-sa1 | Fruits | 50/500 g |

| Ganoderma sp. | po1-lu4-xia1-mo4 | Fruiting body | 600–1200/500 g |

| Cordyceps sinensis (BerK.)Sacc | ya1-za1-gong1-bu4 | Fruiting body | 30–50/piece |

| Wooden spatulas | 10/piece | ||

| Wooden bowls | 80–250/piece | ||

| Bamboo products | 150–300/piece | ||

| Gourd ladle | 25/piece | ||

| Tibetan incense powder | 15 yuan/jar |

Other use categories

In total, 71 plants from other use categories, including ritual plants (24), fodders (20), fuelwoods (19), craft plants (10), tools (5) and dyes (4) (Table 3).

Tibetans burn some plants in their daily life to pray for happiness. A total of 22 wild plants were used for ritual use (Fig. 5b), and the most frequently reported species were Rhododendron anthopogon.

A total of 21 plant species were used as fodders (Fig. 5c), and the most frequently reported species were Polygonum tortuosum, followed by Fargesia sp. and Poaceae sp. Animal husbandry is one of the local important industries. In addition to grazing in pastures, local Tibetans also collect some plants and store them before the withered period arrives to supplement nutrition for livestock.

In addition, a total of 30 wild plants were used as fuelwood (Fig. 5d), tools, dyes and crafts. Among them, the most frequently reported is Rheum australe, which is used to dye clothes and wooden bowls. The locals collect its roots, dry them in the sun, boil them in water and put them in wooden bowls to dye them red. The making of wooden bowls is a symbolic handicraft culture of the Gyirong. They collect the stems of dead birch or cypress trees and process them into wooden bowl handicrafts, which is more well documented in our previous study [9].

Comparison of wild useful plants between Tibetan ethnic groups in different areas

We mainly compared the differences in wild useful plant species among Gyirong (with a total of 110 species), Burang (with a total of 75 species) [27] and Yadong (with a total of 121 species) [22]. The results showed that 36 species of plants in the catalog of Gyirong and Yadong were the same, but only 17 species were the same in Gyirong and Burang. In addition, there were only 11 overlapping species between all the three regions. In general, the wild useful plant resources in Gyirong and Yadong are more abundant and similar than in Burang (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of wild useful plants between three Tibetan ethnic groups. a The natural landscape of Yadong; b the natural landscape of Buran; c the natural landscape of Gyirong; d Venn diagram of three communities

Discussion

Natural environment and culture influence indigenous plant knowledge

Firstly, these differences might be caused by the distribution of the plants. The research areas are not the same size, and the geographical and climatic environments and vegetation types are different [52]. Gyirong and Yadong include tropical to subtropical climate, and the main vegetation type is coniferous broad-leaved mixed forest (Fig. 6). However, Burang Town belongs to the temperate arid climate, and the main vegetation types are desert grassland (Fig. 6) [53]. Although there are differences in the utilization of plants in the three areas, there are still some plants that reflect the common preferences of them. For example, Carum carvi, an important wild vegetable and seasoning in Tibetan regions, ranked top 5 in CII value in all three regions. The use of Tibetan incense plants such as Juniperus indica and Rhododendron anthopogon also reflects the common cultural characteristics of the Tibetan people. In addition, Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora and Saussurea tridactyla also show the current situation of the spread of plant culture driven by the economy [22, 27].

To sum up, different natural environments may lead to different plant utilization. For example, there are obvious differences between Yadong, Gyirong and Burang, and each region has its own special plant knowledge. Previous studies have noted that geographical isolation could contribute to the preservation of diverse cultural traditions of local people in Himalayan regions [54] and could help preserve diverse traditional botanical knowledge. Our study also shows that the same cultural groups have common cultural preferences, for example, 11 plant species are shared across the three areas.

Important wild useful plants

Based on the results of the CII quantitative analysis, we evaluated the top five wild plants that are important in the daily life of Tibetans in Gyirong Town.

Allium prattii C.H.Wright (CII = 1.071) is an important edible plant in Gyirong. Its young leaves and bulbs can be consumed as wild vegetables, and its fruits and flowers can be eaten as seasonings. A local woman said:

Ri guo (A. prattii) is a very delicious seasoning, you can use it for stewing potatoes or meat. There's a lot of it on the mountain that we pick it for consuming or selling.

This reflects two aspects of the plant, the first is that it is a delicacy that locals enjoy. In addition, it is easy to obtain. This plant is widely distributed in the Himalayas of China and northern India and Nepal [55]. It is also used as an edible plant in other areas. For example, it has the same usage as Gyirong in Yadong County, Tibet [22]. In Litang, Sichuan, China, the Tibetans also use the fresh bulb of the plant as a wild vegetable and spice [32]. In addition, it is also used to increase appetite and treat digestive system diseases, which was recorded in the Tibetan medical scripture “Jing Zhu Ben Cao” [56].

Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora (Pennell) D. Y. Hong (CII = 1.016) has important practical and economic value, which also drives the local people to collect it. Locals grind the dried root and drink it with boiling water to treat inflammation or fever. The plant is mainly distributed in the eastern Himalayas, at the junction of China and Nepal [55]. Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora was widely used by the locals to treat cold. This plant was first recorded in the “Si Bu Yi Dian and was mainly used to treat fever [23, 57]. According to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, this plant can treat many diseases [42]. In the Yadong County of the Himalayas and Maithili region of eastern Nepal, it is used by locals to treat fever and headaches with high consensus [30].

Gymnadenia orchidis Lindl. (CII = 0.921), its root is an important tonic, the local people cook it with chicken, duck or milk, which can nourish the body. It is a traditional Tibetan medicinal plant for nourishing which was documented in “Jing Zhu Ben Cao” [56]. It was first recorded in the Tibetan medical work “Four Medical Canons” born in the eighth century AD [23]. The roots also were sold to increase income.

Rhododendron anthopogon D. Don(CII = 0.873)is an important ritual plant for “Sang” (People burn some plants in the morning to pray for a peaceful day) [58], the distribution range of R. anthopogon is almost all over the Himalayas, so is relatively easy to obtain [55]. An informant mentioned:

“We have to burn incense plants every morning, which smell good and can refresh us.”

When we ask what plants are best. He replied:

“Polu (R. anthopogon) is the best.”

The local Tibetans collect the old leaves of R. anthopogon and sun-dry them as materials for “Sang.” In addition to R. anthopogon, Juniperus indica and Artemisia sp. are important materials for “Sang.” R. anthopogon is also a beverage plant for local people to drink and sell. Its flowers are collected and sun-dried and then soaked in water to drink. It has a unique flavor, but drinking too much will cause headaches, which may be related to the toxic ingredients contained in it. According to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, its flowers and leaves are used separately in Tibetan medicine, and its flowers can be taken as tea, which has a good curative effect on asthma and chronic bronchitis [59].

The bulbs of Fritillaria cirrhosa D. Don (CII = 0.857) were used by the locals to treat colds and coughs, and the main processing method is decoction. In addition, F. cirrhosa is also an important economic plant and a veterinary medicinal plant. It is recorded in the Chinese “Materia Medica and Tibetan Medicine Volume” that F. cirrhosa has the effect of resolving phlegm and relieving cough [23]. Fritillaria cirrhosa, which has high commercial value, has been excessively and indiscriminately harvested. As a result, its resources are declining sharply, and it is on the verge of extinction [60].

In particular, of these top five plant species, four were driven by economic value and one was driven by culture. This reflects to a certain extent that the main driving force for the spread of plant utilization knowledge is the economy.

The state of traditional knowledge of wild useful plants in Gyirong

Tibetans of Gyirong have a wealth of knowledge. Most of the people who have acquired knowledge among the Tibetans of Gyirong are middle-aged, and these people have more voice and power in social life. Young people are reluctant to learn traditional plant knowledge [9]. Therefore, with the development of social economy and time, traditional knowledge is slowly disappearing or changing into other forms, such as knowledge about the economic plants. Protecting and documenting preexisting botanical knowledge is important and urgent.

Traditional wild plants’ knowledge of local Tibetans is also heavily influenced by traditional Tibetan medicine and tourism [9, 26]. The plant knowledge of the Tibetans in Gyirong is influenced by the traditional Tibetan medicine culture. In the cataloging of this study, 26 species were documented in traditional Tibetan medicine books [23]. In addition, locals sell many wild plants in the store, including various seasonings and medicines, and these products are mainly aimed at tourists. With the development of commerce, the excessive collection of plants has caused a certain degree of damage to the local ecological environment [61].

Local people not only use wild plants to meet their own needs but can also profit from wild plants. According to local government statistics on the basic situation of the township, the understory economy of wild plants has become an important source of economic income for locals. For example, Fritillaria cirrhosa and Neopicrorhiza scrophula are suffering from exhaustive collection. In addition, there are 11 other plant species under different levels of protection, but these plants are not protected because of commercialization [51].

Gyirong Tibetans have a rich traditional knowledge of wild plants, which has been influenced by the traditional Tibetan medicine culture. With the development of the social economy, their traditional knowledge of plants has also been affected by tourism culture, and the economy has gradually become the important driving force of wild plant collection.

The relevance of this study for the development of the local community

Locally, the economy has become the main driver of the use of local plants. This phenomenon, if not restricted, may lead to the overharvesting of wild plants. Although local people obtain permits before collecting the fungus, there are no special management measures for collecting other wild plants. It is worth noting that the impact of the current tourism economy has made local traditional knowledge increasingly narrow. Previous studies have shown that biodiversity loss not only negatively affects the ecology and environment, but also culture, with profound implications for cultural resilience and biocultural diversity conservation efforts [62]. Therefore, if local communities want to achieve sustainable use of wild economic plants, we should not only pay attention to the protection of biodiversity, but also pay attention to the importance of traditional culture [63]. Local communities should carry out protection activities from the aspects of the restricted collection of economic plants and recording and publicizing traditional knowledge.

Although wild edible plants can provide additional nutritional supplements to local people, we should also pay attention to the possible harm of some plants when they are consumed. According to previous reports, Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum is a nutritious wild vegetable. If it is not soaked for enough time and cooked, the toxic carcinogens contained in the plant will not be removed [64, 65]. It contains Anthraquinones (AQs) in Rheum australe. An increasing number of studies have reported that AQs induce nephrotoxicity [66]. The young leaves of Phytolacca acinosa are used as wild vegetables, but the red roots of it are poisonous and inedible [55]. Therefore, the food safety of wild edible plants should also be an issue for community development.

Conclusion

Gyirong has rich plant diversity and a long history and culture. This study is the first systematic cataloging and evaluation work using ethnobotanical survey and research methods in Gyirong. This study enriched the ethnobotanical study of the Himalayan region, and 111 wild plant species used in local Tibetan daily life were recorded. Multiple uses of these plants were analyzed, and the most culturally significant species of the local Tibetan people were identified by quantitative methods. Medicinal and edible plants play a significant role for the local Tibetan people in household-level food and health.

Based on the comparison study, the use of wild plants differed sharply among different areas, which might be attributed to the various geographical environments and vegetation types. In addition, people in different Tibetan communities retain similar plant use preferences. Botanical traditional knowledge of Tibetan in Gyirong is also heavily influenced by the traditional Tibetan medicine culture and tourism. In the future, we should pay more attention to the reasonable protection of cherished plants and promote the inheritance and development of traditional knowledge.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the informants for sharing their knowledge with us. We thank Professor Pei Shengji for his technical guidance. In addition, we thank Mr. Xu Haikun for being an auto driver in the wild works.

Author contributions

WYH organized the study team and provided technical support. GCA and DXY executed the research plan. GCA identified the specimen and wrote the manuscript. HHB, ZY and WYH collected the data. YHZ participated in the drawing of the map in the article. WYH reviewed the manuscript. All authors took part in the fieldworks. All authors were involved in the drafting and revision of the manuscript and approved the final revision.

Funding

The study was funded by “The Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (No. 2019QZKK0502).”

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors asked for permission from the local authorities and the people interviewed to carry out the study.

Consent for publication

The people interviewed were informed about the study’s objectives and the eventual publication of the information gathered, and they were assured that the informants’ identities would remain undisclosed.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chang-An Guo and Xiaoyong Ding contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Chang-An Guo, Email: guochangan@mail.kib.ac.cn.

Xiaoyong Ding, Email: dingxiaoyong@mail.kib.ac.cn.

Huabin Hu, Email: huhb@xtbg.ac.cn.

Yu Zhang, Email: zhangyu2@mail.kib.ac.cn.

Huizhao Yang, Email: yanghuizhao@mail.kib.ac.cn.

Yuhua Wang, Email: wangyuhua@mail.kib.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Balick MJ, Cox PA. Plants, people, and culture: the science of ethnobotany. New York: Scientific American Library; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tardío J, Pardo-De-Santayana M, Morales RJ. Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain. Bot J Linn Soc. 2006;152(1):27–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2006.00549.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frazee L, Morris-Marano S, Blake-Mahmud J, Struwe L. Eat your weeds: edible and wild plants in urban environmental education and outreach. Plant Sci B. 2016;62(2):72–84. doi: 10.3732/psb.1500003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Z, Lu XP, Lin FK, Naeem A, Long CL. Ethnobotanical study on wild edible plants used by Dulong people in northwestern Yunnan, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2022;18(1):1–21. doi: 10.1186/s13002-022-00501-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin Y, Wang SP, Zhang JY, Zhuo ZY, Li XR, Zhai CJ, et al. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Gaomi. China J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;265:113228. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senku JE, Okurut SA, Namuli A, Kudamba A, Tugume P, Matovu P, Wasige G, Kafeero HM, Walusansa A. Medicinal plant use, conservation, and the associated traditional knowledge in rural communities in Eastern Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2022;50(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s41182-022-00428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bahru T, Kidane B, Tolessa A. Prioritization and selection of high fuelwood producing plant species at Boset District, Central Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical approach. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s13002-021-00474-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geng YF, Hu GX, Ranjitkar S, Wang YH, Bu DP, Pei SJ, Ou XK, Lu Y, Ma XL, Xu JC. Prioritizing fodder species based on traditional knowledge: a case study of mithun (Bos frontalis) in Dulongjiang area, Yunnan Province, Southwest China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017 doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0153-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding XY, Guo CA, Hu HB, Wang YH. Plants for making wooden bowls and related traditional knowledge in the Gyirong Valley, Tibet, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2022;18(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13002-022-00514-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huai HY, Fu WZ. Advances of ethnobotany of non-timber forest products. J Plant Resour Environ. 2006;15(3):65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaoue OG, Coe MA, Bond M, Hart G, Seyler BC, McMillen H. Theories and major hypotheses in ethnobotany. Econ Bot. 2017;71(3):269–287. doi: 10.1007/s12231-017-9389-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonti M. The co-evolutionary perspective of the food-medicine continuum and wild gathered and cultivated vegetables. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2012;59(7):1295–1302. doi: 10.1007/s10722-012-9894-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eoin LN. Ethnoecology: losing traditional knowledge. Nat Plants. 2016;2(8):16125. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhuang H, Wang C, Wang YN, Jin T, Huang R, Lin ZH, Wang YH. Native useful vascular plants of China: a checklist and use patterns. Plant Divers. 2021;43(2):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pld.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pei SJ. Review on two decades development of ethnobotany in China. Acta Bot Yunn. 2008;30(4):505–509. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1143.2008.00505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li GH, Long CL. New advances in ethnobotany. Sci. 2019;2:5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pei SJ. Ethnobotany of China: review and prospect. Chin Acad Med Mag Org. 2003;2:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pei SJ. A preliminary study on ethnobotany of Xishuangbanna. Trop. Plant. Reser. 1981;20:16–30.

- 19.Pieroni A, Nebel S, Quave C, Münz H, Heinrich M. Ethnopharmacology of liakra: traditional weedy vegetables of the Arbëreshë of the Vulture area in southern Italy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;81(2):165–185. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma V, Varshney R, Sethy NK. Human adaptation to high altitude: a review of convergence between genomic and proteomic signatures. Hum Genom. 2002 doi: 10.1186/s40246-022-00395-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu TY. The Qinghai–Tibetan plateau: how high do tibetans live? High Alt Med Biol. 2001;2(4):489–499. doi: 10.1089/152702901753397054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo CA, Ding XY, Addi YW, Zhang Y, Zhang XQ, Zhuang HF, Wang YH. An ethnobotany survey of wild plants used by the Tibetan people of the Yadong River Valley, Tibet, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2022;18(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s13002-022-00518-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.An Editoal Commi of the Adminstration Bure of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Chinese Matea Medica (Zhonghua Bencao). Shanghai: Shanghai Science& Technology Press. 2000; ISBN: 7-5323-6628-6.

- 24.Zhao YH. Magical tibetan culture. Beijing: The Ethnic Publishing House; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mh D. Customs and superstition of tibetans. London: The Mitre Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salick J, Byg A, Amend A, Gunn B, Law W, Schmidt H. Tibetan medicine plurality. Econ Bot. 2006;60(3):227–253. doi: 10.1663/0013-0001(2006)60[227:TMP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding XY, Guo CA, Zhang X, Li J, Jiao YX, Feng HW, Wang YH. Wild plants used by tibetans in Burang Town, characterized by alpine desert meadow, in Southwestern Tibet, China. Agronomy-Basel. 2022;12(3):704. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12030704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Longzhu DJ, Kang JH, Sheng Z, La B. Ethnobotanical study onTibetan substituting tea plants in Banma Area. Qinghai Chin Wild Plant Resour. 2020;39(8):80–85. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang DD, Chen X, Atanasov AG, Yi X, Wang S. Plant resource availability of medicinal Fritillaria species in traditional producing regions in Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang J, Kang YX, Ji XL, Guo QP, Jacques G, Pietras M, Luczaj N, Li DW, Łuczaj Ł. Wild food plants and fungi used in the mycophilous Tibetan community of Zhagana (Tewo County, Gansu, China) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2016;12:21. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0094-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang YX, Łuczaj Ł, Kang J, Wang F, Hou JJ, Guo QP. Wild food plants used by the Tibetans of Gongba Valley (Zhouqu county, Gansu, China) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boesi A. Traditional knowledge of wild food plants in a few Tibetan communities. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10(1):75. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Dao Z, Yang C, Liu Y, Long CL. Medicinal plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-la, Yunnan, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunwar RM, Nepal BK, Kshhetri HB, Rai SK, Bussmann RW. Ethnomedicine in Himalaya: a case study from Dolpa, Humla, Jumla and Mustang districts of Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wangchuk P, Pyne SG, Keller PA. An assessment of the Bhutanese traditional medicine for its ethnopharmacology, ethnobotany and ethnoquality: textual understanding and the current practices. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148(1):305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wangyal JT. Ethnobotanical knowledge of local communities of Bumdeling Wildlife Sanctuary, Trashiyangtse. Bhutan Ind J Tradit. 2012;11(3):447–452. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12030704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wangchuk P, Yeshi K, Jamphel K. Pharmacological, ethnopharmacological, and botanical evaluation of subtropical medicinal plants of Lower Kheng region in Bhutan. Integr Med Res. 2017;6(4):372–387. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunwar RM, Fadiman M, Cameron M, Bussmann RW, Thapa-Magar KB, Rimal B, Sapkota P. Cross-cultural comparison of plant use knowledge in Baitadi and Darchula districts. Nepal Himalaya J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14:40. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0242-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wangchuk P, Tobgay T. Contributions of medicinal plants to the Gross National Happiness and Biodiscovery in Bhutan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0035-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang YF. Millennium gyirong. China Tibetology Publishing House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li JJ. Gyirong: Paradise valley in the heart of the Himalayan Mountains: the natural splendor of the back garden of Mount Gyirong valley. Tibet Geogr. 2012;4:26. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu SH, Yan JZ, Zhang YL, Peng T, Su KC. Exploring the evolution process and driving mechanism of traditional trade routes in Himalayan region. Acta Geogr Sin. 2021;76(9):2157–2173. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duojie CD. On the ancient Tibet traffic route of the Silk Road. Chin Cul Trad Mod. 1995;4:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeLancey S. Lhasa dialect. In: Thurgood G, LaPolla RJ, editors. Sino-Tibetan languages. London: Psychology Press; 2003. pp. 270–288. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The information system of Chinese rare and endangered plants. http://www.iplant.cn/rep/ Accessed in 2019.

- 46.Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. The Plants of the World Online. Published on the internet. https://powo.science.kew.org/.

- 47.Reyes-Garcia V, Huanca T, Vadez V, Leonard W, Wilkie D. Cultural, practical, and economic value of wild plants: a quantitative study in the Bolivian Amazon. Econ Bot. 2006;60(1):62–74. doi: 10.1663/0013-0001(2006)60[62:CPAEVO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cook FEM. Economic botany data collection standard. The International Working Group on taxonomic databases for plant sciences (TDWG) by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 1995. ISBN: 0947643710.

- 49.Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Cultural importance indices, a compara-tive analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria Northern Spain. Econ Bot. 2008;62:24–39. doi: 10.1007/s12231-007-9004-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Troter R, Logan M. Informant consensus: a new approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In: Etkin NL, editor. Indigenous medicine and diet: biobehavioural approaches. New York: Redgrave Bedford Hills; 1986. pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Information System of Chinese Rare and Endangered Plants (ISCREP). https://www.plantplus.cn/rep/.

- 52.Yang J, Chen WY, Fu Y, Yang T, Luo XD, Wang YH, Wang YH. Medicinal and edible plants used by the Lhoba people in Medog County, Tibet, China. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu ZY. Vegetations in China. Beijing: Science Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farooquee NA, Saxena KG. Conservation and utilization of medicinal plants in high hills of the central Himalayas. Environ Conserv. 1996;23(1):75–80. doi: 10.1017/s0376892900038273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Editoral Committee of Flora of China, Flora of China. Beijing, Science Press; 2013.

- 56.Dimaer D. Jing Zhu Ben Cao. Qinghai Nationalities Publishing House; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yusui Y, Li DM. Si Bu Yi Dian. Qinghai People's Publishing House; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li ML, Xu JC. The “Wei sang” custom of Tibetan families in Yunnan-Taking two Tibetan communities in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture as an example. Ethno- nat’lStudies. 2007;169(06):46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou XL, Lai YX, Wu NZ, Huang S. Studies on chemical constituents of the flowers from Rhododendron anthopogon. J Pharmacal Sci West Chin. 2009;25(2):132–134. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo SL. A review of the research on the cherished medicinal plant Fritillaria cirrhosa. Tibet Technol. 2020;12:2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-3403.2020.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang XZ, Yang YP, Piao SL, Bao WK, Wang GX. Ecological change on the tibetan plateau. Chin SciEngine. 2015;60(32):3048. doi: 10.1360/N972014-01339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seyler BC, Gaoue OG, Tang Y, Duffy DC, Aba E. Collapse of orchid populations altered traditional knowledge and cultural valuation in Sichuan, China. Anthropocene. 2020;29:100236. doi: 10.1016/j.ancene.2020.100236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Camara-Leret R, Fortuna MA, Bascompte J. Indigenous knowledge networks in the face of global change. PNAS. 2019;116(20):9913–9918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821843116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Y, Wujisguleng W, Long CL. Food uses of ferns in China: a review. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81(4):263–270. doi: 10.5586/asbp.2012.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Łuczaj Ł. Edible ferns of the world: ethnobotany, foraging and cooking. Independently published. 2022. ISBN: 979-8424507571.

- 66.Liu P, Wei HW, Chang JH, Miao GX, Liu XG, Li ZS, Liu LY, Zhang XR, Liu CZ. Oral colon-specific drug delivery system reduces the nephrotoxicity of rhubarb anthraquinones when they produce purgative efficacy. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14(4):3589–3601. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.