Abstract

With McCrone’s famous statement in mind, we set out to investigate the polymorphic behavior of a small-molecule dual inhibitor of Rac and Cdc42, currently undergoing preclinical trials. Herein, we report the existence of two polymorphs for 9-ethyl-3-(5-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-3-yl)-9H-carbazole (MBQ-167). These were characterized by differential scanning calorimetry, thermogravimetric analysis, Raman and Infrared spectroscopy, as well as powder and single crystal X-ray diffraction. The results obtained from the thermal analysis revealed that MBQ-167 form II undergoes an exothermic phase transition to form I, making this the thermodynamically stable form. An examination of the Burger-Ramberger rules for assigning thermodynamic relationships in polymorphic pairs indicate that this system is monotropic. The structure elucidation reveals that these forms crystallize in the orthorhombic (Pbca) and monoclinic (P21/n) space groups. A conformational analysis shows that the metastable form (form II) presents the most planar conformation along the significant torsion angles identified. Hirshfeld surface analysis confirms that van der Waals contacts are the primary interactions and only subtle differences in short contacts help differentiate each form. These findings support the notion that polymorphism is prevalent in organic molecules and that one should invest time and money probing possible polymorphs, particularly in early development as in the case of MBQ-167.

Keywords: Polymorphism, Crystallization, Thermal analysis, Vibrational spectroscopy, Powder X-ray diffraction, Crystal structure

1. Introduction

It has been well established that many solids exhibit polymorphism, a phenomena that imparts molecules with the ability to crystallize in more than one crystal structure, (Hilfiker, 2006; Brittain et al., 2009) complicating experimental and computational endeavors to understand, predict and control crystallization in numerous branches of the chemical industry. One branch particularly influenced by the occurrence of polymorphism is pharmaceuticals. Many notorious cases have been documented as a result of drug development and manufacturing mishaps as well as patent litigation involving polymorphism in pharmaceuticals. (Tandon et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2014; Newman and Wenslow, 2016; Chemburkar et al., 2000; Desikan et al., 2005; Lohray et al., 2003; Bernstein, 2020) It has been stated that “every compound has different polymorphic forms, and that, in general, the number of forms known for a given compound is proportional to the time and money spent in research on that compound.” (Bernstein, 2011) A recent study reported that the minimum polymorphism occurrence to be expected is at least 50%. (Cruz-Cabeza et al., 2015) Because different polymorphic modifications can exhibit differences in solubility and bioavailability, (Brittain et al., 2009; U.S., 2007; Censi and Di Martino, 2015; Kobayashi et al., 2000) we set out to investigate the crystal forms of 9-ethyl-3-(5-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-3-yl)-9H-carbazole, better known as MBQ-167, a small-molecule currently undergoing preclinical studies for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. (Humphries-Bickley et al., 2017).

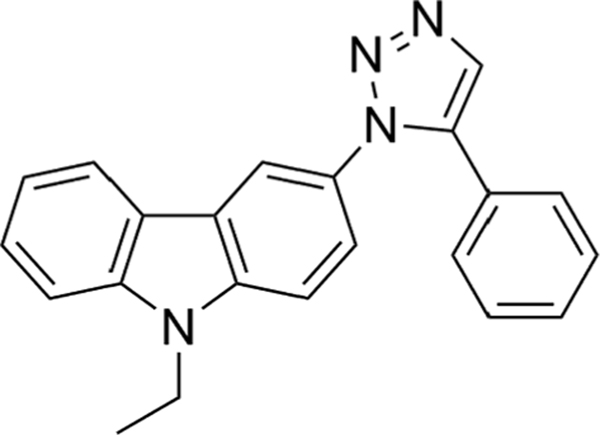

MBQ-167 is a 1,5-disubstituted-1,2,3-triazole derivative with a carbazolyl moiety at the 1-position and a phenyl ring at the 5-position (Fig. 1). (Maldonado et al., 2019) It has been designed to act as a dual inhibitor of Rac and Cdc42, both small GTPases that are involved in the regulation of cell migration. The synthesis and in vitro and in vivo activity of MBQ-167 has been described previously. (Humphries-Bickley et al., 2017; Maldonado et al., 2019).

Fig. 1.

Molecular structure of 9-ethyl-3-(5-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-3-yl)-9H-carbazole (C22H18N4, MBQ-167).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Two batches (MQ7-PD-025-3 and MQ7QRV-001) of 9-ethyl-3-(5-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-3-yl)-9H-carbazole (MBQ-167), were received from MBQ Pharma, Inc. Both batches are reported to have a purity of 99.5% as determined by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis. The CAS Registry Number for MBQ-167 is 2097938-73-1. Ethyl acetate ACS reagent (≥99.5%) and heptane ReagentPlus® (99%) were both purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ethanol (190 proof) ACS/USP Grade was purchased from Pharmco Aaper. Nanopurified water (18.23 MOhm/cm, pH = 5.98, and mV = 57.3) was obtained from the Aries Filter (Gemini). All reagents were used “as received” without further purification.

2.2. Crystallization of MBQ-167 forms I and II

MBQ-167 was obtained by recrystallization of the material from ethanol (MQ7-PD-025-3). This produced the initial and most prevalent form of this compound, MBQ-167 form I. The novel form, MBQ-167 form II, was obtained by recrystallization from 33% (v/v) heptane in ethyl acetate (MQ7QRV-001).

2.3. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Thermal analysis was carried out for MBQ-167 forms I and II to determine the peak melting temperature (Tm) and enthalpy of fusion (ΔHfus) and/or enthalpy of crystallization (ΔHcr) using linear peak baseline. (Menczel and Prime, 2009; Cassel and Behme, 2004) The instrument, a DSC Q2000, from TA Instruments, Inc. is equipped with a RCS40 single-stage refrigeration system. An indium standard (Tm = 156.6 °C and ΔHfus = 0.7832 kcal/mol) was employed for the instrument calibration. Gently powdered MBQ-167 forms I and II were weighed (1.000–3.000 mg) into hermetically sealed Tzero aluminum pans, respectively, using a XP26 microbalance from Mettler Toledo (±0.002 mg). Once sealed, the pans were equilibrated at 25.0 °C for 5 min before heating to 250.0 °C at a rate of 5.0 °C/min and cooled to 25.0 °C at 10.0 °C/min under a N2 atmosphere (50 mL/min). DSC analysis was performed in triplicate (n = 3) and the peak Tm and ΔH were averaged (see Table S1 in the supplementary material). Thermograms were analyzed using a linear baseline on the TA Universal Analysis 2000 software (v. 4.5A).

2.4. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The TGA (TA Instruments, Inc. Q500) was calibrated with a calcium oxalate monohydrate (CaC2O4∙H2O) standard. Between 1.000 and 2.000 mg of gently powdered MBQ-167 forms I and II, respectively, were equilibrated at 25.0 °C for 5 min before heating to 400.0 °C under a N2 atmosphere (60 mL/min) at a rate of 5.0 °C/min. TGA analysis was performed in duplicate (n = 2) and thermographs (see Figure S2 in the supplementary material) were analyzed using TA Universal Analysis 2000 software (v. 4.5A).

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to identify differences among the vibrational modes that characterize the packing of MBQ-167 forms I and II. The FTIR spectra were recorded using a Bruker Tensor-27 attenuated total reflectance (ATR) spectrophotometer between 4000 and 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 averaging 32 scans (1 scan/s). The OPUS Data Collection Program (v. 7.2) was used to collect the FTIR data. A list of the vibrational frequencies (cm−1) for both polymorphic forms can be found in Table S2 of the supplementary material.

2.6. Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra of MBQ-167 forms I and II were collected using a Thermo Scientific DXR2 Raman microscope equipped with a 780 nm laser, 400 lines/mm grating, 50 μm slit, and 3 s exposure time by averaging 32 scans. Spectra were collected at room temperature over the range of 150 to 3200 cm−1 and analyzed utilizing the OMNIC for Dispersive Raman software (v. 9.2.0). The objective lenses used to collect the Raman spectra were 20x and 50x for forms I and II, respectively. Representative Raman spectra and a list of the vibrational modes (cm−1) for both forms can be found in Figure S4 and Table S3 of the supplementary material.

2.7. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis

The diffraction patterns of MBQ-167 forms I and II were generated using a Rigaku XtaLAB SuperNova single microfocus Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5417 Å) source operating at 50 kV and 1 mA equipped with a HyPix3000 X-ray detector. PXRD data collection was performed at 300 and 100 K using an Oxford Cryosystems Cryostream 800 cooler. The powdered samples of MBQ-167 forms I and II were mounted in MiTeGen micro loops with a small amount of paratone oil. Diffractograms were collected over a range between 6 and 40° (in 2θ) with a step size of 0.01° for 120 s and a detector distance of 100 mm using the Gandolfi move experiment for powders. Powder patterns were analyzed using the CrysAlisPRO software (v. 1.171.39.46). A list of the peak positions (°) and percentage relative intensities (%) of both forms at 300 K is provided in Table S4 of the supplementary material.

2.8. Single crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis

Optical microscopy with polarized light was used to evaluate the morphology and crystal quality of the resulting MBQ-167 crystals. Optical micrographs were collected within a Nikon Polarizing Microscope Eclipse LV100N POL, equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi2 camera and NIS Elements BR software (v. 4.30.01). Using a small amount of paratone oil the single crystals for each form were mounted in MiTeGen micro loops. Crystal structures were determined from diffraction data collected using a Rigaku XtaLAB SuperNova single microfocus Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5417 Å) source equipped with a HyPix3000 X-ray detector in transmission mode (50 kV and 1 mA). An Oxford Cryosystems Cryostream 800 cooler was used to collect the data at 300 and 100 K. Data was analyzed using the CrysAlisPRO software (v. 1.171.39.46). All crystal structures of MBQ-167 were solved by direct methods using SHELXS. The refinement was made using full-matrix least squares on F2 within the Olex2 software (v. 1.2). (Dolomanov et al., 2009) All non-hydrogen atoms were anisotropically refined.

2.9. Hirshfeld surface analysis

The Hirshfeld surface analysis was performed to investigate the presence of different intermolecular interactions in the crystal structures of both polymorphic forms of MBQ-167. Employing the crystallographic information files (CIF files) collected at 100 K for each polymorph, the Hirshfeld surface and the 2D fingerprint plots were generated using CrystalExplorer™ (v. 17.5). (Turner et al., 2017) The theory of this analyses is described elsewhere. (Spackman and Jayatilaka, 2009; McKinnon et al., 2007) Hirshfeld surfaces along a, b, and c-axis and the 2D fingerprint plots can be found in Figures S19 and S20 of the supplementary material.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The thermogram of MBQ-167 form I reveals a single endotherm peak at 153.43 ± 0.05 °C (ΔHfus = 7.17 ± 0.09 kcal/mol), which corresponds to the average Tm of this form (Fig. 2a). In contrast to form I, the thermogram of form II shows various thermal transitions illustrated in Fig. 2b. The first endothermic event occurs at 129.89 ± 0.09 °C (ΔHfus = 4.89 ± 0.06 kcal/mol) and is attributed to the average Tm of form II. This is followed by an exothermic event at 143.1 ± 0.6 °C (ΔHcr = −1.3 ± 0.5 kcal/mol), which is attributed to recrystallization from the melt and trailed by a second endothermic transition at 153.65 ± 0.02 °C (ΔHfus = 2.9 ± 0.9 kcal/mol) corresponding to the Tm of form I. Due to overlap among these thermal events, the enthalpies reported here might be taken as estimations. The average Tm and ΔHfus for MBQ-167 form I presented here, is in close agreement with those published in a previous study. (Jiménez Cruz et al., 2021) The average Tm and ΔH for MBQ-167 form II are reported for the first time.

Fig. 2.

Representative DSC thermograms overlay of MBQ-167 (a) form I (black), and (b) form II (blue). The arrows correspond to the direction of the heating (red) and cooling (blue) trend lines in the DSC thermograms.

To determine the thermodynamic relationship between the two polymorphic forms and estimate the relative stability, Burger-Ramberger rules were applied. (Hilfiker, 2006; Burger and Ramberger, 1979) The transition of form II to I observed in Fig. 2b is exothermic. Moreover, both the highest melting point (153.43 ± 0.05 °C vs 129.89 ± 0.09 °C) and heat of fusion (7.17 ± 0.09 kcal/mol vs 4.89 ± 0.06 kcal/mol) are attributed to form I. Therefore, based on the heat of transition and heat of fusion rules the thermodynamic relationship can be classified as monotropic. An additional rule that can be applied to determine thermodynamic relationships is the heat capacity rule, which establishes that “the relationship is monotropic if the polymorph with the higher melting point has the lower heat capacity at a given temperature”. (Hilfiker, 2006) At 25 °C the average heat capacity (Cp) is 0.006829 and 0.01204 J/K for forms I and II, respectively. Dividing the Cp by the average sample size (2.465 and 1.563 mg), the average specific heat capacity (cp) can be calculated for form I (2770 J/kg∙K) and form II (7704 J/kg∙K). This rule also supports that this polymorphic pair is monotropically related. Thus, based on the Burger-Ramberger rules it is proposed that this polymorphic system is monotropically related with form I being the thermodynamically stable form.

3.2. Vibrational spectroscopy analysis of MBQ-167 polymorphs

Representative FTIR and Raman spectra for MBQ-167 forms I and II were collected from 4000 to 400 cm−1 and 3200 to 150 cm−1, respectively. Fig. 3 depicts the FTIR spectra while Raman spectra can be found in Figure S4 of the supplementary material. The vibrational analysis helps to compare both polymorphs based on the identification of differences in the vibrational modes as a result of different packing modes. A shift in the FTIR signal can be observed for the C–H stretching vibrational mode. The C–H stretching mode presents a higher intensity for form I (2976 cm−1) compared to form II (2979 cm−1). In the region from 2000–1500 cm−1 (Fig. 3a), form I displays several bands at frequencies of 1892, 1879, and 1850 cm−1, which represent the C–H bending characteristic of aromatic compounds. (Pavia et al., 2001) In contrast, these bands are not observed in form II. There is also a difference in the C = C bands (carbazole group) between the regions of 1650–1600 cm−1 in form I and 1500–1460 cm−1 in form II. This region is shifted and more pronounced in form I than form II. A strong band representative of C–H bending vibrations can be observed at 1445 cm−1 in form I only (Fig. 3b). The band at 1382 cm−1 can be used for the identification of MBQ-167 form II (Fig. 3b). Moreover, the aromatic amines in the molecular structure of MBQ-167 produce a characteristic band for the C–N stretching mode, which occurs at 1343 and 1321 cm−1 in form I and at 1347 and 1323 cm−1 in form II, respectively. (Pavia et al., 2001) Another significant difference in the vibrational modes of form I, is a characteristic band at 1332 cm−1 (Fig. 3b) that can be observed between the two bands corresponding to the 1,2,3-triazole group (1343 and 1321 cm−1) which is not present in form II (Pavia et al., 2001).

Fig. 3.

Representative FTIR spectra overlay of MBQ-167 form I (black) and form II (blue) with characteristic regions at (a) 2000–1500 cm−1, (b) 1500–1300 cm−1, and (c) 900–700 cm−1. Peaks marked with an asterisk (*) and letter “x” represents unique bands for MBQ-167 form I and form II, respectively.

The terminal methyl group (–CH3) can be identified by the shifted absorption bands at 891 and 883 cm−1 in forms I and II, respectively. A weak band at 852 cm−1, a medium band at 826 cm−1, and a strong band at 800 cm−1 can be used for the identification of form I, while a single band at 812 cm−1 is characteristic in form II (Fig. 3c). Additional characteristic bands for each polymorph are at 764, 752, 733, 625, 534 cm−1 for form I and at 767, 741, 725, 629, 527 cm−1 for form II.

3.3. PXRD analysis

PXRD experiments were performed for the solid-state identification of the two polymorphic forms of MBQ-167. Representative experimental and simulated PXRD patterns of MBQ-167 forms I and II are shown in Fig. 4. From the experimental PXRD patterns, it can be observed that form I presents unique reflections at 7.04, 9.87, 10.49, 12.98, 13.47, 23.18, and 25.20° in 2θ at 300 K. On the other hand, the characteristic reflections for form II are observed at 7.87, 11.00, 12.20, 14.54, and 19.67° in 2θ at 300 K. The PXRD patterns collected at 100 K can be found in Figures S15 and S17 of the supplementary material.

Fig. 4.

The experimental and simulated PXRDs of MBQ-167 forms I (black and grey) and II (dark and light blue) at 300 K. Simulated PXRDs were obtained from the crystallographic information files (CIF files) of the crystal structures solved by SCXRD at 300 K.

A comparison between the experimental and simulated PXRDs for MBQ-167 forms I and II can be used to confirm the phase purity resulting from the crystallization conditions employed to generate each form. Phase selection was achieved as a result of the recrystallization of MBQ-167 in several solvents (ethanol, ethyl acetate, water in ethanol, and heptane in ethyl acetate) within this work. Representative PXRDs of MBQ-167 recrystallized from different pure and binary solvent mixtures can be found in Figure S7 of the supplementary material. These results also agree with previous observations regarding selective crystallization of form I (the absence of concomitant polymorphism (Bernstein et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2007) when MBQ-167 is recrystallized from Class 2 and 3 pure and binary solvents. (Jiménez Cruz et al., 2021) Thus far, form II has only been achieved by the recrystallization of MBQ-167 from 33% (v/v) heptane in ethyl acetate.

3.4. SCXRD analysis

The elucidation of the crystal structure for MBQ-167 forms I and II was conducted initially at 300 K, and then at 100 K to determine if phase changes occur at low temperature. The relatively low reliability factor (Rf) (<6%) values is indicative of the good quality (“fitness”) of each solved crystal structure of MBQ-167 (Harris et al., 1998; Harris, 2003; Wlodawer et al., 2008). No low temperature transformations were observed. The resulting structures show one molecule in the asymmetric unit for each of these polymorphs. The asymmetric units are illustrated in Fig. 5a for forms I and II. The packing motifs along the a, b, and c-axis for each polymorph is shown in Fig. 5b–d for the structures solved at 100 K. The packing motifs from the structures solved at 300 K for both forms can be found in Figures S8 and S9 of the supplementary material. Previous results of MBQ-167 have not focus on the elucidation of the solid-state for this molecular entity.

Fig. 5.

Asymmetric unit of MBQ-167 forms I and II (a) as well as the crystal packing along (b) a-axis, (c) b-axis, and (d) c-axis for structures solved at 100 K.

The crystallographic parameters are listed in Table 1 and the Oak Ridge Thermal Ellipsoid Plots (ORTEPs) of the structurally characterized MBQ-167 forms I and II at 300 and 100 K can be found in Figures S10–S13 of the supplementary material. MBQ-167 form I crystallizes in the orthorhombic space group Pbca. The asymmetric unit connects with four adjacent molecules through short contacts (Fig. 5). The shortest contact is formed between a carbon atom in the phenyl ring of one molecule to nitrogen atom N(1) in the 1,2,3-triazole group of an adjacent molecule (C(5)–H(5)∙∙∙N(1) = 2.626 Å). Additionally, two C∙∙∙H contacts (C(11)∙∙∙ H(13)–C(13) = 2.776 Å) and (C(20)∙∙∙H(13)–C(13) = 2.830 Å) join adjacent molecules. These contacts link adjacent molecules along the b-axis. Two short contacts (N(2)∙∙∙H(1)–C(1) = 2.718 Å) and (C(4)–H(4)∙∙∙ C(7) = 2.819 Å) reinforce the packing of adjacent molecules along the a-axis. A short π∙∙∙π contact (C(18)∙∙∙C(21) = 3.376 Å) is responsible for the packing along the ac-plane joining adjacent molecules.

Table 1.

Summary of crystallographic data for MBQ-167 forms I and II at 300 and 100 K.

| Form | I | I | II | II |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal system | orthorhombic | orthorhombic | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| Space group | Pbca | Pbca | P2 1 /n | P2 1 /n |

| Temperature (K) | 300 (2) | 100 (10) | 300 (10) | 100 (16) |

| a (Å) | 7.7110 (1) | 7.57408 (5) | 12.0906 (2) | 11.8490 (1) |

| b (Å) | 17.9646 (1) | 17.87230 (12) | 9.4280 (1) | 9.3591 (1) |

| c (Å) | 25.2167 (2) | 24.98583 (16) | 16.9628 (2) | 16.9689 (2) |

| α (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β (°) | 90 | 90 | 109.726 (2) | 110.171 (1) |

| γ (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Volume (Å3) | 3493.14 (6) | 3382.23 (4) | 1820.12 (5) | 1766.37 (3) |

| Calc. density (g/cm3) | 1.287 | 1.329 | 1.235 | 1.273 |

| Z | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Z’ | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cu-Kα, Å | 1.5417 | 1.5417 | 1.5417 | 1.5417 |

| Rf (%) | 5.62 | 4.05 | 4.98 | 3.47 |

Abbreviations: Z, number of units in the unit cell; Z’, number of asymmetric units; a, b, c, lengths of the cell edges; α, β, γ, angles between the cell edges; Cu-Kα, copper K-alfa; Rf, reliability factor.

MBQ-167 form II crystallizes in the monoclinic P21/n space group (Table 1). The shortest contact observed occurs between a nitrogen atom N(2) in the 1,2,3-triazole group and a carbon from the phenyl ring (C(6)–H(6)∙∙∙N(2) = 2.626 Å). This contact propagates adjacent molecules along the b-axis shown in Fig. 5c. The packing is reinforced by C∙∙∙H contacts (C(1)∙∙∙H(7)–C(7) = 2.856 Å) between carbon atoms in the 1,2,3-triazole and the phenyl ring. This contact expands the packing of the molecules along the a-axis (Fig. 5b). No other significant intermolecular interactions were observed for this polymorph.

As shown in Table 1, the density of MBQ-167 form I (1.329 g/cm3) is higher than that of form II (1.273 g/cm3) at 100 K. The density rule states that “for a non-hydrogen-bonded system at absolute zero, the most stable polymorph will have the highest density, because of stronger intermolecular van der Waals interactions” (Hilfiker, 2006). The occurrence of a higher number of short contacts for form I than form II, as observed in their crystal structures, supports that form I is the most stable form between these polymorphs at room temperature. The assessment made here with the density rule is in agreement with our discussion above, which related to the Burger-Ramberger rules for estimating thermodynamic relationships.

Conformational analysis of the asymmetric units in the crystal structures solved at 100 K, reveals that the above-mentioned MBQ-167 polymorphs possess strikingly distinct conformations (Table 2). Fig. 6a presents the significant torsion angles (τ) found for MBQ-167 in different colors. The torsion angle (τ) along the triazole and the phenyl ring τ1 is 65.82° in form I while is slightly more planar (35.00°) in form II. Another significant difference occurs along τ2 that also involves the same functional groups. In form II, τ2 is more planar (34.06°) than in form I (67.33°). The torsion angle along τ3 in form I is 10.97° while in form II is −2.09°, indicating the latter is slightly more planar. The adjacent torsion angle τ4 is −11.26° in form I and 2.86° in form II. Lastly, the torsion angle corresponding to τ5, which comprises the carbazolyl group, is highly planar in both polymorphs (2.84° in form I and −0.20° in form II). The overlay of the asymmetric units of MBQ-167 forms I (black) and II (blue) at 100 K can be observed in Fig. 6b. The packing of each structure within the overlay can be found in Figure S18 of the supplementary material.

Table 2.

Summary of significant torsion angles τ (°) in the asymmetric unit of MBQ-167 forms I and II for structures solved at 100 K.

| Atoms in the torsion angle, τ (°) | MBQ-167 | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Form I | Form II | |

| τ1 (C1-C2-C3-C4) | 65.82 | 35.00 |

| τ1′ (C1-C2-C3-C8) | −111.84 | −142.07 |

| τ2 (N3-C2-C3-C8) | 67.33 | 34.06 |

| τ2′ (N3-C2-C3-C4) | −115.02 | −148.86 |

| τ3 (C18-N4-C20-C21) | 10.97 | −2.09 |

| τ4 (C18-N4-C17-C16) | −11.26 | 2.86 |

| τ5 (C10-C11-C12-C13) | 2.84 | −0.20 |

| τ6 (N2-N3-C9-C22) | −107.81 | −113.44 |

| τ7 (N2-N3-C9-C10) | 67.17 | 64.03 |

| τ8 (C2-N3-C9-C10) | −120.75 | −123.98 |

| τ9 (C2-N3-C9-C22) | 64.27 | 58.55 |

Apostrophe (’) refers to the corresponding supplementary angle.

Fig. 6.

(a) Molecular structure of MBQ-167 illustrating the significant torsion angles (τ) represented by different colors; τ1 (blue) = C(1)-C(2)-C(3)-C(4), τ2 (red) = N(3)-C(2)-C(3)-C(8), τ3 (light green) = C(18)-N(4)-C(20)-C(21), τ4 (dark green) = C(18)-N(4)-C(17)-C(16), and τ5 (pink) = C(10)-C(11)-C(12)-C (13). The purple and neon green colors indicate that two torsion angles (τ) overlap. (b) Overlay of the asymmetric units of MBQ-167 forms I (black) and II (blue) at 100 K.

3.5. Hirshfeld surface analysis

CrystalExplorer™ (v. 17.5) was utilized to generate the Hirshfeld surfaces and 2D fingerprint plots based on the crystal structures of the two MBQ-167 polymorphs solved at 100 K. (Turner et al., 2017; Spackman and Jayatilaka, 2009; Spackman and McKinnon, 2002) Van der Waals contacts are the primary interactions observed for both polymorphs. As shown in Fig. 7a, the H∙∙∙H contacts constitute ~45% of all contacts in form I and ~50% in form II. The second most abundant contacts are the C∙∙∙H contacts, which have a higher contribution in form I (37.2%) than in form II (30.4%). In terms of the contributions of the N∙∙∙H contacts to the Hirshfeld surfaces, there are no significant differences between these polymorphs (16.3 vs. 14.1%). The most striking differences are those presented by the π∙∙∙π (2.8%) and N∙∙∙C (2.3%) contacts observed in form II, which are barely present in form I (0.3% for π∙∙∙π and 0.8% for N∙∙∙C). No contribution for the N∙∙∙N contacts is observed in both polymorphs. Fig. 7b displays the Hirshfeld surface of MBQ-167 forms I and II along the a-axis. Hirshfeld surfaces along the b and c-axis can be found in Figure S19 of the supplementary material. The 2D fingerprint plots can be found in Figure S20 of the supplementary material.

Fig. 7.

(a) Percent (%) relative contribution to the Hirshfeld surface of various intermolecular interactions, and (b) Hirshfeld surface of both polymorphs of MBQ-167 along the a-axis.

4. Conclusions

The results presented in this study provide the first insights into the prevalence of polymorphism in MBQ-167, a small molecule dual inhibitor of Rac and Cdc42. To date, this compound has been shown to exist in two polymorphic forms. MBQ-167 forms I and II were characterized through various techniques including thermal analysis, vibrational spectroscopy, PXRD, and SCXRD to understand the thermodynamic relationships between these two polymorphic forms and the structural motifs that make each form unique. From the thermal analysis, it can be concluded that MBQ-167 form II undergoes an exothermic phase transition to form I, making form I the thermodynamically most stable form. Moreover, an examination of the Burger-Ramberger rules for assigning thermodynamic relationships in polymorphic pairs indicate that this is a monotropic system. The vibrational analysis performed using Raman and FTIR serves to identify characteristic vibrations that facilitate the differentiation of the two polymorphic forms. PXRD can be used for the identification between the polymorphs since each form presents a unique diffraction pattern. The crystal structures of MBQ-167 forms I and II, revealed by SCXRD, shows that van der Waals contacts are the primary intermolecular interactions observed for both polymorphs. A Hirshfeld surface analysis served to identify subtle differences in the contributions of intermolecular interactions that characterize each polymorph of MBQ-167. The findings reported in this work support the notion that polymorphism is prevalent in organic molecules and that one should invest time and money probing any given compound, particularly in early development as in the case of MBQ-167.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Gabriel Quiñones Vélez, a member of the Crystallization Design Institute (CDI), for help with the Raman and FTIR data collection and analysis.

Funding

This work was supported primarily by MBQ Pharma, Inc. and partially by the National Institutes of Health - The National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIH-NIGMS) Award No. SC3GM116713 to Dr. Cornelis P. Vlaar. In addition, Jocelyn M. Jiménez Cruz was partially supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Wisconsin - Puerto Rico Partnership for Research and Education in Materials (DMR-1827894). The Rigaku XtaLAB SuperNova X-ray micro diffractometer was acquired through the support of the NSF under the Major Research Instrumentation Program (CHE-1626103). The TGA TA Q500 was obtained through the NSF Grants EPS-100241 awarded to the Puerto Rico Institute for Functional Nanomaterials (IFN).

Abbreviations:

- τ

Torsion angles

- HPLC

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

- v/v %

volume/ volume percent

- DSC

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

- Tm

peak melting temperature

- ΔHfus

enthalpy of fusion

- ΔHcr

enthalpy of crystallization

- TGA

Thermogravimetric Analysis

- CaC2O4∙H2O

calcium oxalate monohydrate

- FTIR

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

- ATR

Attenuate Total Reflectance

- PXRD

Powder X-ray Diffraction

- Cu-Kα

copper K-alfa

- SCXRD

Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction

- CIF files

crystallographic information files

- Cp

heat capacity

- cp

specific heat capacity

- Rf

reliability factor

- ORTEPs

Oak Ridge Thermal Ellipsoid Plots

- Z

number of units in the unit cell

- Z’

number of asymmetric units

- a, b, c

lengths of the cell edges

- α, β, γ

angles between the cell edge

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jocelyn M. Jiménez Cruz: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Cornelis P. Vlaar: Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Torsten Stelzer: Investigation, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Vilmalí López-Mejías: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121064.

Reference

- Hilfiker R, 2006. Polymorphism in the Pharmaceutical Industry; Hilfiker R, Raumer M. von, Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. 10.1002/9783527697847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brittain HG, Byrn SR, Lee E, 2009. Polymorphism in Pharmaceutical Solids Vol. 192. 10.3109/9781420073225-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R, Tandon N, Thapar RK, 2018. Patenting of polymorphs. Pharm. Pat. Anal. 7 (2), 59–63. 10.4155/ppa-2017-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos OMM, Reis MED, Jacon JT, Lino M.E.d.S., Simões JS, Doriguetto AC, 2014. An evaluation of the potential risk to the quality of drug products from the Farmácia Popular Rede Própria. Brazilian J. Pharm. Sci. 50 (1), 1–24. 10.1590/S1984-82502011000100002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman A, Wenslow R, 2016. Solid form changes during drug development: good, bad, and ugly case studies. AAPS Open 2 (1). 10.1186/s41120-016-0003-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chemburkar SR, Bauer J, Deming K, Spiwek H, Patel K, Morris J, Henry R, Spanton S, Dziki W, Porter W, Quick J, Bauer P, Donaubauer J, Narayanan BA, Soldani M, Riley D, McFarland K, 2000. Dealing with the impact of ritonavir polymorphs on the late stages of bulk drug process development. Org. Process Res. Dev. 4 (5), 413–417. 10.1021/op000023y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan S, Parsons RL, Davis WP, Ward JE, Marshall WJ, Toma PH, 2005. Process development challenges to accommodate a late-appearing stable polymorph: a case study on the polymorphism and crystallization of a fast-track drug development compound. Org. Process Res. Dev. 9 (6), 933–942. 10.1021/op0501287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lohray B, Banerjee K, Panikar A, 2003. Contributory patent infringement and the pharmaceutical industry. J. Intellect. Prop. Rights 08 (4), 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J. Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals, 2nd ed.; Lecomte C, Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2020; Vol. 77. 10.1107/S2052520621000494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J, 2011. Polymorphism – a perspective. Cryst. Growth Des. 11 (3), 632–650. 10.1021/cg1013335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Cabeza AJ, Reutzel-Edens SM, Bernstein J, 2015. Facts and fictions about polymorphism. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44 (23), 8619–8635. 10.1039/c5cs00227c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. ANDAs: Pharmaceutical Solid Polymorphism. Chemistry, Manufacturing and Controls Information. J. Generic Med. 2007, 2 (3), 264–269. 10.1057/palgrave.jgm.4940078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Censi R, Di Martino P, 2015. Polymorph impact on the bioavailability and stability of poorly soluble drugs. Molecules 20 (10), 18759–18776. 10.3390/molecules201018759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Ito S, Itai S, Yamamoto K, 2000. Physicochemical properties and bioavailability of carbamazepine polymorphs and dihydrate. Int. J. Pharm. 193 (2), 137–146. 10.1016/S0378-5173(99)00315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries-Bickley T, Castillo-Pichardo L, Hernandez-O’Farrill E, Borrero-Garcia LD, Forestier-Roman I, Gerena Y, Blanco M, Rivera-Robles MJ, Rodriguez-Medina JR, Cubano LA, Vlaar CP, Dharmawardhane S, 2017. Characterization of a dual Rac/Cdc42 inhibitor MBQ-167 in metastatic cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16 (5), 805–818. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado María del Mar, Rosado-González Gabriela, Bloom Joseph, Duconge Jorge, Ruiz-Calderón Jean F., Hernández-O’Farrill Eliud, Vlaar Cornelis, Rodríguez-Orengo José F., Dharmawardhane Suranganie, 2019. Pharmacokinetics of the Rac/Cdc42 inhibitor MBQ-167 in mice by supercritical fluid chromatography-tandem Mass Spectrometry. ACS Omega 4 (19), 17981–17989. 10.1021/acsomega.9b0164110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menczel Joseph D., Prime R. Bruce (Eds.), 2009. Thermal Analysis of Polymers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cassel RB, Behme R, 2004. A DSC method to determine the relative stability of pharmaceutical polymorphs. Am. Lab. 36 (16). http://www.tainstruments.com/pdf/literature/TP003_DSCMethodforStabilityofPharmaceuticalPolymorphs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov OV, Bourhis LJ, Gildea RJ, Howard JAK, Puschmann H, 2009. {\it OLEX2}: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42 (2), 339–341. 10.1107/S0021889808042726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner MJ, McKinnon JJ, Wolff SK, Grimwood DJ, Spackman PR, Jayatilaka DMS, 2017. CrystalExplorer 17. 10.1107/S1600576721002910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spackman MA, Jayatilaka D, 2009. Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm 11 (1), 19–32. 10.1039/b818330a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon JJ, Jayatilaka D, Spackman MA, 2007. Towards quantitative analysis of intermolecular interactions with Hirshfeld surfaces. Chem. Commun. 37, 3814–3816. 10.1039/b704980c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Jiménez, Jocelyn M, Vlaar Cornelis P., López-Mejías Vilmalí, Stelzer Torsten, 2021. Solubility measurements and correlation of MBQ-167 in neat and binary solvent mixtures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 66 (1), 832–839. 10.1021/acs.jced.0c00908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger A, Ramberger R, 1979. On the polymorphism of pharmaceuticals and other molecular crystals. I. Mikrochim. Acta 72 (3–4) (1979) 259–271. 10.1007/BF01197379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavia Donald L., Lampman Gary M., Kriz GS Introduction to Spectroscopy; Harcourt College Publishers: Fort Worth, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J, Davey RJ, Henck JO, 1999. Concomitant polymorphs. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 38 (23), 3440–3461. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IS, Lee AY, Myerson AS, 2007. Concomitant polymorphism in confined environment. Pharm. Res. 25 (4), 960–968. 10.1007/s11095-007-9424-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KDM, Johnston RL, Kariuki BM, 1998. The genetic algorithm: foundations and applications in structure solution from powder diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 54 (5), 632–645. 10.1107/S0108767398003389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KDM, 2003. New opportunities for structure determination of molecular materials directly from powder diffraction data. Cryst. Growth Des. 3 (6), 887–895. 10.1021/cg030018w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodawer A, Minor W, Dauter Z, Jaskolski M, 2008. Protein crystallography for non-crystallographers, or how to get the best (but not more) from published macromolecular structures. FEBS J. 275 (1), 1–21. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spackman MA, McKinnon JJ, 2002. Fingerprinting intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals. CrystEngComm 4 (66), 378–392. 10.1039/b203191b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.