Abstract

To investigate the role of interleukin-5 (IL-5) during Toxoplasma gondii infection, IL-5 knockout (KO) mice and C57BL/6 control mice were infected intraperitoneally with ME49 cysts and the course of infection was monitored. The mortality rate during chronic infection was significantly greater in IL-5-deficient animals, and consistent with this finding, the KO mice harbored a greater number of brain cysts and tachyzoites than did their wild-type counterparts. Although the IL-5 KO animals did not succumb until late during infection, increased susceptibility, as measured by accelerated weight loss, was detectable during the acute stages of infection. The amounts of total immunoglobulin (Ig), IgM, and IgG2b were comparable in both strains, while the amount of IgG1 was much smaller in IL-5 KO mice. Spleen cell production of IL-12 in response to T. gondii antigen was approximately threefold lower in the KO strain, and this decrease correlated with a selective loss of B lymphocytes during culture. A link between the presence of B cells and augmented IL-12 production was established by the finding that after removal of B cells with monoclonal antibody and complement, wild-type- and KO-derived cells produced equivalent levels of IL-12 in response to T. gondii antigen. These results demonstrate a protective role of IL-5 against T. gondii infection and suggest that IL-5 may play a role in the production of IL-12.

The intracellular protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii is a frequently occurring opportunistic pathogen among humans and animals. Infection is characterized by an acute phase and a chronic phase. During acute infection, the tachyzoite form of the parasite replicates intracellularly, rapidly leading to host cell lysis. The released tachyzoites then infect new cells. With the rise of the parasite-specific immune response, tachyzoites are cleared and a chronic phase of infection follows, in which the parasite encysts in the form of long-lived bradyzoites. The cysts are found predominantly within the central nervous system, where they cause little inflammation (28). Nevertheless, intact immune system defenses are required during this stage of infection, as evidenced by the occurrence of toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS patients and in experimental models of immunosuppression (29, 32).

It is well established that T. gondii infection induces a strong cell-mediated immune response. Type 1 cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-12 (IL-12), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) are crucial in protective immunity. The absence of any one of these proinflammatory mediators results in increased mortality as a result of uncontrolled tachyzoite growth (1, 10, 13, 43). It is also clear that type 2 cytokine responses play an important role during T. gondii infection. Thus, infection of IL-4 knockout (KO) mice with T. gondii ME49 leads to increased susceptibility associated with severe inflammation in the central nervous system during chronic toxoplasmosis (48). In addition, infection of IL-10 KO animals results in early death of the mice in association with abnormally high levels of inflammatory cytokines (15, 35).

The type 2 cytokine IL-5 is a homodimeric glycoprotein produced predominantly by activated CD4+ T cells (22). The cytokine has several effects on B lymphocytes. Thus, IL-5 enhances B-cell IL-2 receptor expression and promotes B-cell proliferation and differentiation (49, 51, 52). The cytokine also enhances immunoglobulin A (IgA) production by lipopolysaccharide-stimulated B cells (49) and works with IL-4 to promote IgG1 production (30). Recent studies with IL-5 KO mice have revealed a requirement for this cytokine in B-1-cell development (26). IL-5 is also essential for production and function of eosinophils and serves as an antiapoptotic factor for the latter cells (47).

Although none of the known functions of IL-5 would be predicted to be required to survive T. gondii infection, it has been shown that this type 2 cytokine is induced in the brain, spleen, and mesenteric lymph nodes during the normal course of murine infection (2, 6). The recent construction of IL-5 KO mice allowed us to evaluate host responses to T. gondii infection in the absence of this cytokine. Surprisingly, IL-5 KO animals displayed increased cyst and tachyzoite burdens and accelerated mortality during chronic infection. Splenocytes from infected IL-5 KO mice produced less IL-12 when restimulated with parasite antigen, and this impairment was associated with selective B-cell loss during culture. Our data uncover a previously unknown function for IL-5 as a cytokine which promotes IL-12 production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Swiss-Webster and C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Taconic Farms Inc. (Germantown, N.Y.). Female RAG-1 KO and matched wild-type (WT) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). IL-5−/− animals (C57BL/6 background), originally provided by M. Kopf (Basel Institute for Immunology, Basel, Switzerland), were bred and maintained in the College of Veterinary Medicine animal facility at Cornell University. The animals were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions and were used at 6 to 8 weeks of age. The experiments used both male and female mice as specified.

Parasites and antigen.

The cystogenic T. gondii strain, ME49, was maintained by serial passage in female Swiss-Webster mice. Briefly, the animals were infected by intraperitoneal (i.p.) inoculation of 20 ME49 cysts, and 4 to 6 weeks later their brains were removed and homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cysts were enumerated and either used immediately for experiments or injected i.p. into new Swiss-Webster mice. The virulent parasite strain, RH, was maintained in vitro by twice-weekly passage on human foreskin fibroblasts in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 1% fetal calf serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, Utah), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (both from Life Technologies). Soluble tachyzoite antigen (STAg) was prepared by sonication of RH strain tachyzoites in the presence of protease inhibitors followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g and dialysis against PBS as described elsewhere (31).

RT-PCR and Southern blot analysis.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was carried out essentially as described elsewhere (57) but with minor modifications. To obtain brain and spleen RNA, these organs were removed and homogenized in 2 ml of PBS (brain) or DMEM (spleen), and then 300 μl of homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 7 min at 4°C, resuspended in 1 ml of RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Inc., Friendswood, Tex.), and either snap frozen in a mixture of dry ice and methanol or used immediately for cDNA synthesis. RNA was purified by following the protocols provided by the company. Briefly, 100 μl of chloroform was added to the samples and the mixture was vigorously shaken for 5 min. The samples were incubated for 15 min at room temperature and then centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 × g and 4°C. The upper, aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube, an equal volume of isopropanol was added, and RNA was allowed to precipitate by overnight incubation at −20°C. RNA was pelleted by centrifugation for 15 min at 1,300 × g and 4°C, washed in 95% ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in H2O. The optical density at 260 nm was measured in a spectrophotometer equipped with a UV lamp (DU-50; Beckman Instruments, Inc., Irvine, Calif.) to estimate the RNA concentration.

The RNA samples (10 μg) were reverse transcribed into cDNA in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 200 U of reverse transcriptase, 20 U of RNasin, 40 mA260 random hexamer oligonucleotide, 8 mM dithiothreitol (all from Life Technologies), and 0.25 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). RT was allowed to proceed for 60 min at 37°C followed by 5 min at 90°C. After the reaction, 175 μl of double-distilled H2O was added, bringing the total volume to 200 μl, and the samples were stored at −20°C until used for amplification. A 10-μl volume of cDNA was amplified in a 50-μl reaction volume containing 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.2 μM primers, 1 U of Taq polymerase (Life Technologies), and 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer with 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The primers used for IL-5 were as follows: 5′ primer, GAC-AAG-CAA-TGA-GAC-ACG-ATG-AGG; 3′ primer, GAA-CTC-TTG-CAG-GTA-ATC-CAG-G. The primer sequences for hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) were as follows: 5′ primer, GTT-GGA-TAC-AGG-CCA-GAC-TTT-GTT-G; 3′ primer, GAT-TCA-ACT-TGC-GCT-CAT-CTT-AGG-C (14). The primer sequences for surface antigen 2 (SAG-2) were as follows: 5′ primer, AAC-AGA-AGA-TCT-AAA-ATG-AGT-TTC-TCA-AAG; 3′ primer, GGG-CTA-CAC-AAA-CGT-GAT-CAA-CAA-ACC-TGC. The number of amplification cycles used was 32, 35, and 23 for IL-5, SAG-2 (p22), and HPRT, respectively.

For Southern blotting, 13.2 μl of PCR product was separated on a 1% agarose gel. The gel was incubated for 35 min in denaturing solution (1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M NaOH) followed by 30 min in neutralization solution (1.5 M NaCl, 1 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]). The DNA products were transferred by blotting to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N+; Amersham Life Science Inc., Arlington Heights, Ill.), and cross-linking was performed by UV irradiation (1200 μJ; UV Stratalinker 2400; Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and heating for 2 h at 80°C. Immobilized amplification products were detected by using the enhanced chemiluminescence system as specified by manufacturer (Amersham Life Science Inc.). Briefly, the membranes were hybridized with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled oligonucleotide probes, incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-FITC antibody (Ab), and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent. The probe sequences used were GGG-GGT-ACT-GTG-GAA-ATG-CTA-T for IL-5, GTT-GTT-GGA-TAT-GCC-CTT-GAC for HPRT (14), and CGA-GGA-AGT-TGA-CGA-CTG-TCC for SAG-2.

Spleen cell culture.

Spleens were collected and placed into cDMEM, composed of DMEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), nonessential amino acid solution (0.1 mM), HEPES buffer (10 mM) (all from Life Technologies), and β-mercaptoethanol (50 μM) (Sigma Chemical Co.). After gentle mashing, the resulting single-spleen-cell suspension was centrifuged for 7 min at 1,000 × g, the supernatant was decanted, and erythrocytes were lysed by resuspending the cells in 1 ml of erythrocyte lysis buffer (Sigma Chemical Co.) and incubating them for 30 s. After two washes in cDMEM, the cells were adjusted to 5 × 106/ml and placed into culture with STAg, and after 24 or 96 h at 37°C, supernatants were collected for cytokine measurement.

To remove B lymphocytes from the responder spleen cell population, monoclonal Ab (MAb)- and complement-mediated depletion was used, as previously described (9). Briefly, a single-cell suspension of splenocytes was incubated for 45 min on ice with medium alone as a control or with hybridoma supernatant containing anti-B220 MAb, washed with cDMEM, and incubated for 45 min with rabbit serum as a source of complement (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, N.Y.) at 37°C. This cycle of Ab- plus complement-mediated depletion was repeated once. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis confirmed that 91% of B220+ cells were depleted compared to the control group treated with complement alone. Cells from the control group were counted and adjusted to 5 × 106 cells/ml, and 200 μl of cell suspension was placed into each well of a 96-well plate. To directly compare the cytokine response in the presence and absence of B lymphocytes, the B-cell-depleted population was adjusted to the same volume as the control group and 200 μl of cells was placed into culture. After a 72-h culture with STAg (100 μg/ml), supernatants were collected for cytokine measurement. In some cultures, protein G-purified anti-IL-5 MAb (TRFK.5) and control rat Ig was included.

Cytokine ELISA.

To measure IL-12(p40), cytokine-specific MAb C15.6 and C17.8, kindly provided by G. Trinchieri, Wistar Institute (58), were used. To perform the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), 96-well plates (Corning Costar Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) were coated overnight at 4°C with MAb C15.6 in PBS (10 μg/ml) and then given three washes in PBS containing 0.05% Tween (PBST). The plates were blocked for 2 h at 37°C in PBS plus 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma Chemical Co.), and washed in PBST; then sample supernatants and IL-12 standard (Genzyme Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) were added, and the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed in PBST, biotinylated MAb C17.8 was added, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 90 min. HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Genzyme Corp.) was then added, and the plates were incubated for 60 min at 37°C. Finally, 100 μl of 2,2-azinodi(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonate) substrate (ABTS) (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) was added to each well, and sample absorbances were measured on a Microplate Bio Kinetics reader (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, Vt.) at 405 nm.

IFN-γ was measured in a similar manner to the IL-12 ELISA, using plate-bound anti-IFN-γ MAb HB170, biotinylated anti-IFN-γ MAb XMG1.2 (Pharmingen Inc., San Diego, Calif.), and HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Genzyme Corp.). Sample absorbances were measured at 405 nm following ABTS addition.

TNF-α levels were measured by a mouse-specific TNF-α ELISA kit as specified by the manufacturer (Genzyme Corp.).

Antibody ELISA.

Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture with syringes preloaded with EDTA (Sigma Chemical Co.). Plasma was collected by centrifugation and stored at −70°C until the day of the assay. We coated 96-well plates with STAg in PBS (5 μg/ml) by overnight incubation at 4°C. After blocking at 37°C for 2 h in PBS plus 1% bovine serum albumin, the plates were washed in PBST, serial dilutions of plasma were added, and the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After the plates were washed in PBST, enzyme-conjugated isotype-specific detection Ab were added. To detect total Ig, an HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratory Inc., West Grove, Pa.) was used. IgG1 was detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Pharmingen Inc.). HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2a (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc., Birmingham, Ala.) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM (Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc.) were used for detection of IgG2a and IgM, respectively. HRP- or alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse Ab were used at a 1:1,000 dilution (1-h incubation at 37°C). Finally, 100 μl of ABTS substrate (for HRP-conjugated Ab) or 0.05% p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma Chemical Co.) in diethanolamine buffer (1 M diethanolamine, 0.02% NaN3, 0.01% MgCl2 [pH 9.8]) (for alkaline phosphatase-conjugated Ab) was added to the plates, and the sample absorbances were measured at 405 nm.

Flow cytometric analysis.

After removal of erythrocytes with erythrocyte lysis buffer, spleen cells were washed with FACS buffer (1% fetal calf serum in PBS, 0.1% NaN3), resuspended in 10% normal mouse serum, and incubated on ice for 15 min. After the cells were washed with FACS buffer, FITC-conjugated anti-B220 (Caltag Laboratories, San Francisco, Calif.) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD3, FITC-conjugated anti-NK1.1, FITC-conjugated anti-CD8, and PE-conjugated anti-CD4 (Pharmingen Inc.) were added, and the cells were incubated on ice for 30 min. The cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer, and Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry System, San Jose, Calif.) was used to analyze data.

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed by the Wilcoxon rank sum test for mortality data, two-way analysis of variance for brain cyst numbers, and Student’s t test for percent weight loss. Comparisons with a probability value of <0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

IL-5 is induced during the normal course of T. gondii infection.

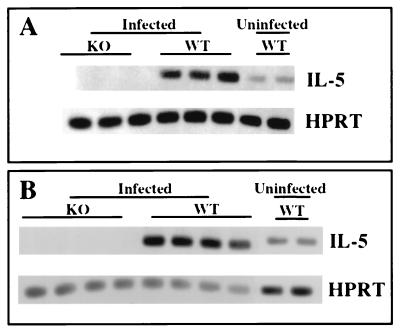

We infected C57BL/6 mice by i.p. injection of 50 ME49 cysts, a dose and route of infection which allow the animals to survive acute-stage disease and establish a chronic infection. As shown in Fig. 1A, IL-5 gene transcripts were up-regulated in the brains of infected animals on day 14 of infection. We similarly found IL-5 up-regulation in the spleens of infected WT mice (Fig. 1B). As expected, IL-5 KO mice displayed no evidence of this cytokine. IL-5 up-regulation was also detected later during infection in the same organs (7 weeks [data not shown]).

FIG. 1.

Up-regulation of IL-5 during T. gondii infection. Male C57BL/6 (WT) or IL-5−/− (KO) mice were infected by i.p. injection with 50 ME49 cysts. Their brains (A) and spleens (B) were removed 14 day later, and expression of IL-5 gene transcripts was assessed by RT-PCR analysis as described in Materials and Methods. In this figure, each band represents a single mouse. This experiment was repeated twice with the same results.

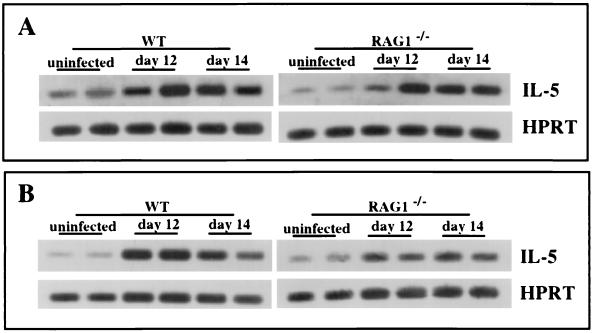

Because T lymphocytes are regarded as a major source of IL-5 (4, 22, 30, 34), we infected RAG-1−/− mice with ME49 and asked whether induction of this cytokine continued to occur. RAG-1 KO animals are unable to use V,D,J recombination during lymphocyte ontogeny and, as a result, fail to generate functional T or B cells (33). Nevertheless, IL-5 induction continues to occur in the brains and spleens of ME49 infected animals (Fig. 2). Flow cytometric analysis confirmed that the infected RAG-1 KO mice did not possess any peripheral T or B lymphocytes (data not shown). We conclude that IL-5 production during infection is not absolutely dependent upon T or B lymphocytes.

FIG. 2.

Expression of IL-5 during T. gondii infection occurs independently of T and B lymphocytes. Female WT (C57BL/6) and RAG-1−/− mice were infected i.p. with 50 ME49 cysts, and on the indicated days postinfection, brains (A) and spleens (B) were removed and IL-5 gene expression was assessed by RT-PCR analysis. Each band represents a single animal. This experiment was performed twice with the same result.

IL-5 KO mice display increased susceptibility to T. gondii infection.

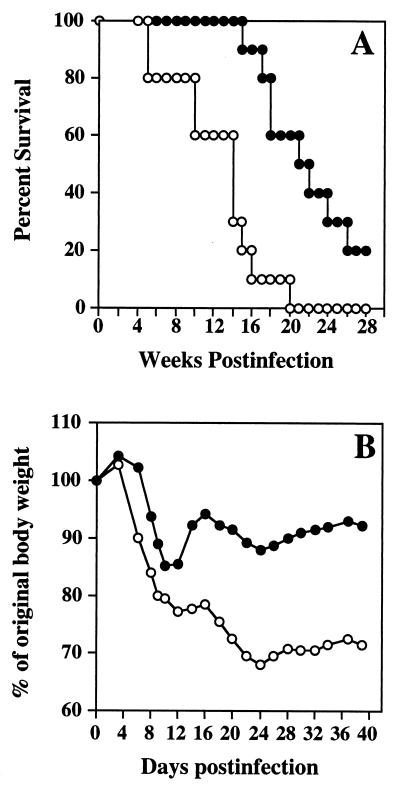

IL-5−/− and WT mice were infected with ME49 to determine the relative ability of the KO strain to resist infection. Figure 3A shows that the KO strain displays increased susceptibility. Thus, by week 19 to 20 after infection, 100% of the IL-5−/− but only 40 to 50% of the WT animals had succumbed.

FIG. 3.

IL-5 KO mice display increased mortality and weight loss during T. gondii infection. (A) Male mice (n = 10 per strain) were infected i.p. with 50 ME49 cysts, and long-term survival was monitored. The statistical significance of these results was determined by the generalized Wilcoxon rank sum test (P = 0.003). (B) The average weight of animals as a percentage of the starting weight during infection is shown (n = 14 per strain). The statistical significance of these results was evaluated by Student’s t test (P < 0.001). Solid circles, WT animals; open circles, IL-5 KO animals. This experiment was repeated four times with essentially identical results.

Although the animals did not begin to die until well into the chronic stage, the increased susceptibility of the KO strain was traceable to earlier times of infection. As shown in Fig. 3B, on day 14 after infection, IL-5−/− and WT animals had lost 23 and only 13% of their body weight, respectively. While WT mice began to regain weight as they proceeded into the chronic stage, this did not occur in the KO animals. Thus, by days 30 to 40 postinfection, the average weight of the IL-5−/− mice was 68 to 78% of their original weight while that of the WT animals was restored to 87 to 92% of their original weight.

Increased parasite levels are associated with IL-5 KO animals.

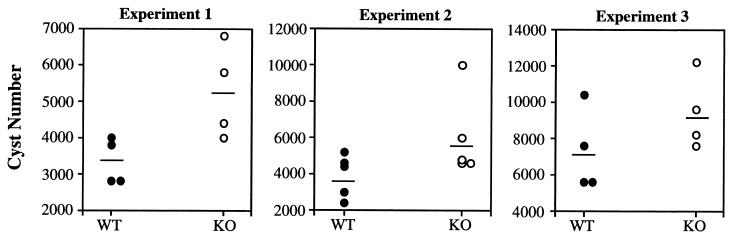

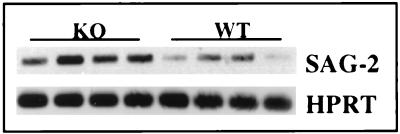

We next asked whether cyst numbers in WT and KO mice differed. As shown in Fig. 4, which displays the results of three experiments, the brains of infected IL-5−/− mice harbored significantly (P = 0.013) greater cyst numbers than did the brains of WT mice during chronic infection. The increased parasite burden was also evident during examination of levels of mRNA for the tachyzoite-specific Ag, p22 (SAG-2). Thus, 7 weeks after infection, a time when the IL-5−/− mice began to die, the p22 mRNA levels were dramatically elevated relative to those in infected C57BL/6 animals (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

IL-5−/− mice display increased numbers of brain cysts relative to WT animals. Groups of male mice (four or five mice per strain) were infected i.p. with ME49 (experiment 1, 20 cysts; experiment 2, 50 cysts; experiment 3, 200 cysts), and 1 month later their brains were removed and the cysts were enumerated. In this figure, each circle represents a single mouse and the horizontal line indicates the average cyst number in each group. The results were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance and found to be statistically significant (P = 0.012).

FIG. 5.

Levels of tachyzoite-specific SAG-2 gene transcripts in the brain are elevated in IL-5 KO animals. Female mice were infected with 50 ME49 cysts, and 7 weeks later their brains removed and the levels of SAG-2 gene transcripts were determined by RT-PCR analysis. Each band in this figure represents the result from a single animal. This experiment was repeated twice with essentially identical results.

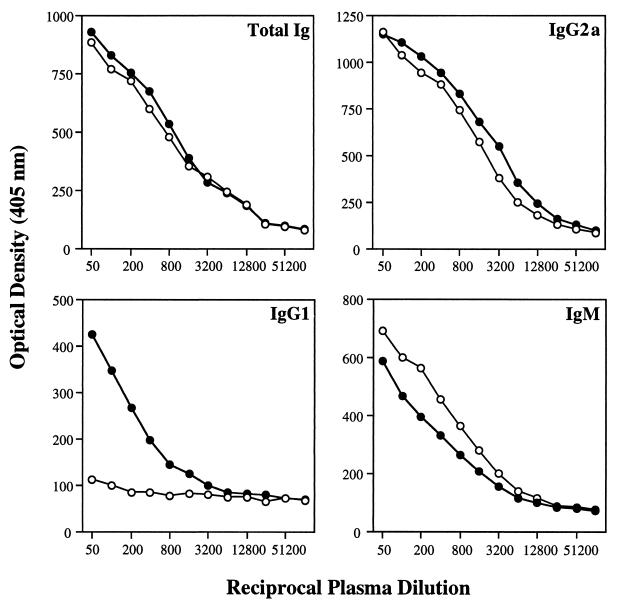

Ab isotype profile of infected mice.

IL-5−/− and WT control mice were bled 7 weeks after infection, and anti-Toxoplasma Ab titers in serum were determined. The levels of total parasite-specific Ig, IgM, and IgG2a were comparable in both mouse strains (Fig. 6). Nevertheless, T. gondii-specific IgG1 was almost totally absent in IL-5 KO mice, consistent with previous reports which indicate that IL-5 enhances IL-4-directed isotype switching to IgG1 secretion (38, 39). In addition, the relatively low IgG1 titer in WT mice (approximately 1/200) compared to the IgG2a titer (approximately 1/1,600) is consistent with the known ability of T. gondii to preferentially induce a strong type 1 cytokine response.

FIG. 6.

Parasite-specific Ab levels in plasma in infected WT and KO mice. Seven weeks following i.p. infection with 50 ME49 cysts, female animals (n = 4 per strain) were bled and assayed for T. gondii-specific Ig by isotype-specific ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. Solid circles, WT mice; open circles, IL-5 KO animals. These results were also obtained in two additional repeat experiments.

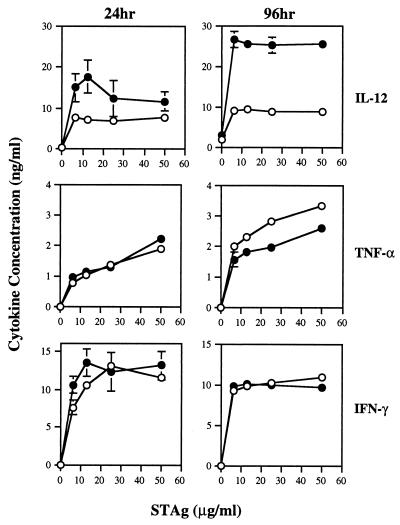

Cytokine profile of infected mice.

Spleen cells from 8-week-infected IL-5−/− and control mice were isolated and incubated with STAg to examine cytokine production in vitro. We measured production at 24 and 96 h after culture initiation. IL-5-deficient and normal mice produced similar amounts of TNF-α and IFN-γ 24 h after culture initiation, while IL-12 levels were slightly elevated in WT mice at this time point (Fig. 7). Although TNF-α and IFN-γ levels remained comparable for both strains after 96 h of culture, the level of IL-12 produced by WT mice was dramatically elevated relative to that produced by the KO strain at the same time and to the cytokine levels in WT mice at 24 h. Thus, while production of IL-12 in the 24-h cultures was similar or identical, by 96 h the values had diverged dramatically as a result of increased WT IL-12 production.

FIG. 7.

Spleen cells from IL-5 KO mice display a specific defect in T. gondii-induced IL-12 production in vitro. At 9 weeks after ME49 infection, spleen cells from WT and KO animals (n = 4 per group) were isolated and stimulated in vitro with STAg (50 μg/ml). At 24 and 96 h after culture initiation, supernatants were collected and assayed for the indicated cytokines by ELISA (see Materials and Methods for details). Solid circles, WT mice; open circles, KO mice. This experiment was repeated three times with the same result.

Phenotypic analysis of spleen cell populations before and after STAg stimulation.

Since control mice produced larger amounts of IL-12 during culture with STAg then did KO mice, we determined if the splenocyte populations in the two strains differed prior to culture initiation. As shown in Table 1, there was no difference between the KO and WT strains in terms of spleen cell populations either before or after infection. In both strains, there was a decrease in the number of CD4+ cells, while other cell types remained approximately equivalent.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic analysis of splenocyte populations in IL-5 KO and WT micea

| Mouse strain | Total no. of cells (107) per spleen expressingb:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B220 | CD3 | CD4 | CD8 | NK1.1 | |

| Noninfected WT | 2.9 ± 0 (37.7% ± 1.1%) | 4.2 ± 0.2 (54.9% ± 0.7%) | 1.8 ± 0.2 (23.8% ± 1.2%) | 1.1 ± 0 (14.2% ± 0.1%) | 0.4 ± 0 (5.8% ± 0.8%) |

| Noninfected KO | 5.7 ± 0.6 (43.4% ± 1.0%) | 6.2 ± 0.7 (47.0% ± 3.5%) | 3.0 ± 0 (23.0% ± 0.5%) | 1.4 ± 0.3 (10.4% ± 1.8%) | 0.7 ± 0 (5.6% ± 0.2%) |

| Infected WTd | 4.3 ± 0.9 (54.9% ± 4.0%) | 2.9 ± 0.1 (37.4% ± 4.1%) | 1.1 ± 0.1 (13.9% ± 2.0%) | 1.0 ± 0.1 (12.6% ± 0.8%) | 0.6 ± 0.1 (7.9% ± 1.4%) |

| Infected KOd | 4.0 ± 1.9 (48.9% ± 4.6%) | 3.1 ± 1.2 (40.8% ± 5.0%) | 1.1 ± 0.1 (12.7% ± 1.4%) | 1.0 ± 0.1 (13.6% ± 1.1%) | 0.6 ± 0.1 (10.2% ± 1.1%) |

Splenocytes were isolated from KO and WT animals (n = 4 per strain) and flow cytometric analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods.

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

The percentage of cells per spleen expressing the indicated marker is given in parentheses.

Animals were infected i.p. with 50 ME49 cysts 8 weeks prior to flow cytometric analysis.

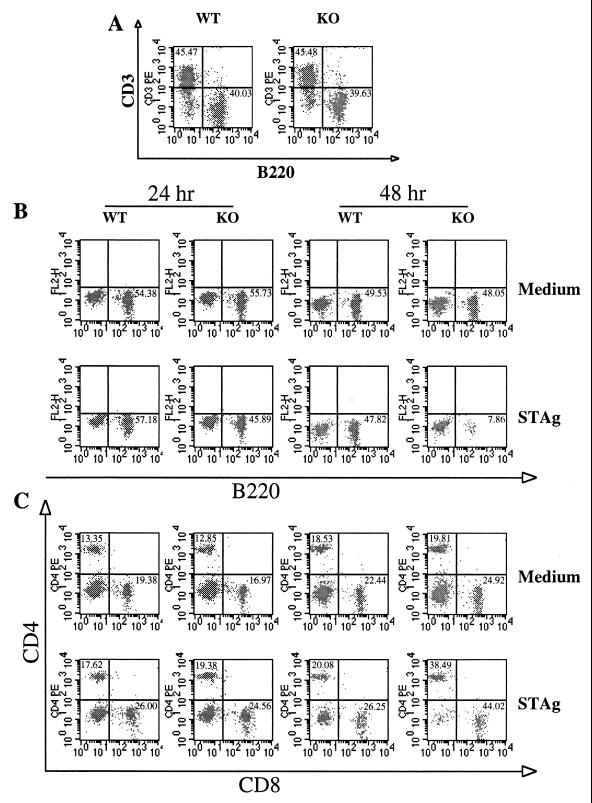

We next asked if spleen cell populations in WT and KO mice differed after in vitro stimulation with STAg. At the start of the experiment, CD3+ and B220+ populations were similar for both infected strains (Fig. 8A). We initiated spleen cell cultures from infected WT and KO mice in the presence of STAg or medium (Fig. 8B). At 24 and 48 h after culture initiation, cells were harvested and subjected to single-color FACS staining with anti-B220 MAb. While B-cell levels in both strains were equivalent after 24 h, by 48 h there was a major decrease in the B220+-cell population of the KO strain. Thus, between 24 and 48 h, the B220+-cell percentage in the KO strain decreased from 46 to 8% of the total STAg-stimulated spleen population. In contrast, the loss of B220+ cells in WT animals was much less dramatic under the same conditions, decreasing from 57 to 48% of the population.

FIG. 8.

Loss of B220+ cells in IL-5−/− animals upon in vitro STAg stimulation. At 5 weeks after ME49 infection, spleens from WT and KO mice (n = 4 mice per group) were isolated. Cells from each strain were pooled and stimulated in vitro with STAg (50 μg/ml). (A) Cell populations stained with a combination of PE-conjugated anti-CD3 and FITC-conjugated anti-B220 at the initiation of cell culture. (B and C) At 24 and 48 h after culture with medium or STAg, cells were harvested and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-B220 (B) or with a combination of FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 and PE-conjugated anti-CD4 (C). This experiment was repeated twice with essentially identical results.

Figure 8C demonstrates that the loss of B cells in cultures of STAg-stimulated IL-5−/− splenocytes was a specific B-cell effect and that it was not due to increased death in the KO population as a whole. Thus, between 24 and 48 h of culture with STAg, the percentage of T cells increased (CD4+ increased from 19 to 38%, and CD8+ increased from 25 to 44%) in the KO strain while T-cell levels in the WT strain remained approximately equivalent. The proportional increase in the T-cell percentage is consistent with a specific B-cell loss (Fig. 8B) in the STAg-stimulated splenocytes from KO mice. Indeed, in terms of absolute number, both strains contain similar numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ cells, while the B220+-cell number in the KO strain decreased (data not shown), again arguing for selective B-cell loss rather than increased T-cell proliferation in the spleen cells from KO mice.

Decreased IL-12 production is associated with B-cell loss.

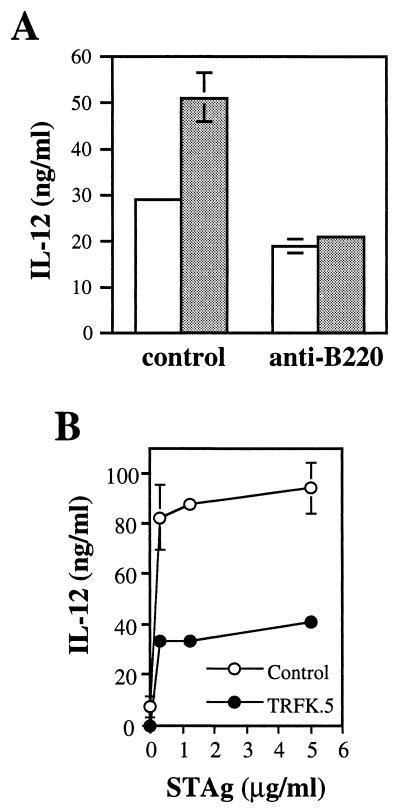

Since lower levels of IL-12 in the cultures of cells from KO mice were associated with selective B-lymphocyte loss in the same culture, this suggested that B cells may normally contribute to IL-12 production in STAg-stimulated cultures. To address this issue, we used anti-B220 MAb and complement to deplete splenocyte populations of B cells in KO and WT mice and examined the ability of the remaining cells to produce IL-12 in response to STAg. As shown in Fig. 9A, the intact splenocyte population in WT mice produced nearly twice the amount of IL-12 as did the splenocytes in KO mice in response to STAg stimulation. However, in the absence of B cells, both strains produced equivalent amounts of IL-12. These results suggest that B cells in the cultures of cells from WT mice promote STAg-induced IL-12 and that in the cultures of cells from KO mice, where the cells do not persist, their contribution is correspondingly reduced.

FIG. 9.

STAg-induced IL-12 production in vitro is partially inhibited by depletion of B220+ cells and IL-5. (A) At 5 weeks after ME49 infection, spleen cells from three WT (shaded bars) and three KO (open bars) mice were collected and pooled, and half of the population was B-cell depleted with anti-B220 MAb and complement while the other half was treated with complement alone. The resulting cells were cultured with STAg (100 μg/ml), and after 72 h the supernatants were harvested and the IL-12 level was measured. (B) Spleen cells from chronically infected WT mice were cultured with the indicated doses of STAg in the presence of 20 μg of TRFK.5 (anti-IL-5 MAb) per ml or the same concentration of control rat Ig. After 96 h, supernatants were harvested and the level of IL-12 was measured. This experiment was repeated twice with essentially identical results.

We also directly examined whether IL-5 was involved in IL-12 production in cultures of parasite-stimulated spleen cells. As shown in Fig. 9B, addition of anti-IL-5 MAb TRFK.5 resulted in a decrease in IL-12 production of approximately 50% relative to that in cultures in the presence of control rat Ig.

DISCUSSION

The type 2 cytokine IL-5 is conventionally associated with helminth infection and allergy (25, 27, 30, 53), and control of intracellular pathogens such as T. gondii is largely controlled by the type 1 cytokines IL-12, TNF-α, and IFN-γ (1, 8, 10, 13, 43). Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that mice deficient for IL-5 production displayed increased susceptibility to the parasite, as measured by accelerated mortality, elevated parasite numbers within the brain, and increased weight loss during acute infection. These results therefore establish a protective role for IL-5 during T. gondii infection.

Although T. gondii is well known as a potent stimulator of type 1 cytokines, overproduction of the same cytokines can be detrimental to the host. However, it is now clear that type 2 cytokine production also is an important component of the host response to this opportunistic pathogen. Thus, mice deficient in IL-10 production display increased mortality, which appears to result from a dysregulated inflammatory cytokine response rather than to an inability to control the parasite (15, 35). The role of IL-4 during T. gondii infection is less clear, although IL-4 KO animals also display increased mortality (41, 48).

Employing RT-PCR-based analysis, we found that IL-5 transcripts were induced in spleens and brains during both the acute stage (days 12 and 14 postinfection) and the chronic stage (7 weeks postinfection). Our data are consistent with previous results, which showed IL-5 mRNA induction in brains and spleens of mice 14 and 90 days after inoculation with the ME49 strain (2). A similar study showed that mesenteric lymph node cells from infected mice produced IL-5 when restimulated in vitro with toxoplasma sonicate as well as with purified T. gondii Ag (6).

Activated CD4+ T cells are regarded as the main source of IL-5 (4, 22, 30, 34), but other subpopulations of T cells, including CD3+ γδ TCR+ T cells in the intestinal mucosa and peripheral CD8+ T cells, can also produce this cytokine (5, 50). In addition, non-T-cell IL-5 sources have been identified, including natural killer cells (53, 54), mast cells (55), Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B cells (24), and eosinophils (3, 11). In the present study, IL-5 mRNA was induced in T. gondii-infected RAG-1−/− mice. Thus, our results strongly suggested that the source of IL-5 in the brains and spleens of infected mice is neither T- nor B-cell derived and that the induction of this cytokine is T- and B-cell independent.

Since IL-5 has effects on B cells and is capable of influencing the Ab isotype repertoire, we compared the plasma Ab response of infected WT and KO animals. The production of parasite-specific total Ig, IgM, and IgG2a was comparable, and the production of IgE was undetectable in both strains. However, T. gondii-specific IgG1 was undetectable in IL-5 KO mice. Our results are consistent with previous reports which suggest that although IL-4 is the critical cytokine in IgG1 isotype switching, B cells require a second signal, provided by IL-5, to secrete this antibody isotype (37–39).

In this study, we used flow cytometry to analyze splenocyte populations and found that the percentage of B and T cells in both strains was comparable in uninfected control and T. gondii-infected mice. When spleen cells from the infected mice were cultured with STAg, there was a selective loss of B220+ cells from the KO strain between 24 and 48 h of culture. At least two possible explanations may account for this. First, in addition to promoting differentiation, IL-5 can promote B-cell proliferation (49, 51, 52). Therefore, it is possible that during STAg restimulation, IL-5 normally acts as a helper factor which serves to sustain B-cell proliferation during extended culture. Second, IL-5 is well known to possess antiapoptotic effects. Thus, the cytokine up-regulates Bcl-2 expression in eosinophils, rendering the cells resistant to inducers of apoptosis (36, 47). In addition, IL-5 blocks anti-IgM-induced apoptosis of immature B-cell lines (21). Therefore, it is possible that IL-5 normally exerts antiapoptotic effects on the B cells present in STAg-stimulated splenocyte populations. We are currently exploring the mechanisms underlying the selective B-cell loss in cell cultures derived from the KO animals.

Of interest is the profile of cytokine production in STAg-stimulated spleen cell cultures. We measured IL-12, IFN-γ, and TNF-α production at 24 and 96 h after culture initiation and found that the amounts of IFN-γ and TNF-α were essentially the same in IL-5−/− and WT animals. However, although both mouse strains produced a comparable amount of IL-12 at 24 h, cells from WT mice produced more IL-12 after 96 h of culture than did cells from the KO strain. Because the divergence of IL-12 production between the two strains generally correlated with the loss of B cells in the KO strain, our results suggest that decreasing B-lymphocyte numbers account for the lower level of IL-12 in the KO strain. Support for this hypothesis comes from our finding that in the absence of B lymphocytes, both KO and WT strains produced a similar amount of IL-12 in response to STAg.

Our results clearly link B-cell loss to lower IL-12 production in cultures of STAg-stimulated splenocytes, but we do not yet understand the mechanism by which this occurs. One possibility is that B cells themselves serve as an IL-12 source in the extended cultures. While IL-12 was originally isolated from a transformed B-cell line (24), it is a matter of controversy whether normal B cells produce IL-12, with evidence both for (7, 45) and against (18, 42).

A second possibility is that B lymphocytes are indirectly involved in IL-12 production, possibly through CD40-CD40 ligand (CD40L)-dependent triggering. In this regard, macrophage and dendritic cells can produce IL-12 through CD40-CD40L interaction (17, 23, 46). Expression of the CD40L on T cells is inducible by activated B cells and can be stabilized by B7/CD28 costimulation (19, 20). Furthermore, B cells themselves are able to express the CD40L under certain conditions (16, 44, 56). Therefore, it is possible that in the splenocyte cultures from WT mice, B cells augment IL-12 production by promoting CD40-CD40L interactions and that the selective B-cell loss in cultures of cells from IL-5−/− mice results in decreased IL-12 production. We are currently directing our efforts to resolving these issues.

We do not know why the IL-5 KO mice display greater susceptibility to T. gondii infection. While splenocytes from these mice clearly produce less IL-12 upon in vitro stimulation, we do not know whether this is a true reflection of the in vivo situation and, if so, whether lower in vivo IL-12 levels result in increased susceptibility to the parasite. We also found that the KO mice produce very little parasite-specific IgG1 after infection. Although it is formally possible that this impairs the ability to survive infection, we think this unlikely, since Ab in general are not believed to be required for resistance to the parasite (12, 40). Regardless of the reason for the death of these animals, our results reveal an unexpected link between endogenous IL-5 production and B-cell-dependent IL-12 production. Uncovering the mechanism underlying this unique observation may provide further insight into the mechanisms of immunity to T. gondii and other microbial pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Susan Bliss for critical review and useful discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander J, Hunter C A. Immunoregulation during toxoplasmosis. Chem Immunol. 1998;70:81–102. doi: 10.1159/000058701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arsenijevic D, Girardier L, Seydoux J, Chang H R, Dulloo A G. Altered energy balance and cytokine gene expression in a murine model of chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E908–E917. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.5.E908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao S, McClure S J, Emery D L, Husband A J. Interleukin-5 mRNA expressed by eosinophils and gamma/delta T cells in parasite-immune sheep. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:552–556. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohjanen P R, Okajima M, Hodes R J. Differential regulation of interleukin 4 and interleukin 5 gene expression: a comparison of T-cell gene induction by anti-CD3 antibody or by exogenous lymphokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5283–5287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardell S, Sander B, Moller G. Helper interleukins are produced by both CD4 and CD8 splenic T cells after mitogen stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2495–2500. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chardes T, Velge-Roussel F, Mevelec M-N, Mevelec P, Buzoni-Gatel D, Bout D. Mucosal and systemic cellular immune responses induced by Toxoplasma gondii antigens in cyst orally infected mice. Immunology. 1993;78:421–429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Andrea A M, Rengarajau M, Valiante N, Chemini J, Kubin M, Aste-Amezaga M, Chan S H, Kobayashi M, Young D, Nickbarg R, Chizzonite R, Wolf S F, Trinchieri G. Production of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF/IL-12) by peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1387–1397. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denkers E Y, Gazzinelli R T. Regulation and function of T cell-mediated immunity during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:569–588. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denkers E Y, Gazzinelli R T, Martin D, Sher A. Emergence of NK1.1+ cells as effectors of immunity to Toxoplasma gondii in MHC class I-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1465–1472. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denkers E Y, Scharton-Kersten T, Gazzinelli R T, Yap G, Charest H, Sher A. Cell-mediated immunity to Toxoplasma gondii: redundant and required mechanisms as revealed by studies in gene knockout mice. In: Kaufmann S H E, editor. Medical intelligence unit: host response to intracellular pathogens. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Co.; 1997. pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desreumaux P, Delaporte E, Clombel J F, Capron M, Cortot A, Janin A. Similar IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF syntheses by eosinophils in the jejunal mucosa of patients with celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;88:14–21. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frenkel J K. Adoptive immunity to intracellular infection. J Immunol. 1967;98:1309–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gazzinelli R T, Denkers E Y, Sher A. Host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii: model for studying the selective induction of cell-mediated immunity by intracellular parasites. Infect Agents Dis. 1993;2:139–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gazzinelli R T, Hieny S, Wynn T, Wolf S, Sher A. IL-12 is required for the T-cell independent induction of IFN-γ by an intracellular parasite and induces resistance in T-cell-deficient hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6115–6119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gazzinelli R T, Wysocka M, Hieny S, Scharton-Kersten T, Cheever A, Kuhn R, Muller W, Trinchieri G, Sher A. In the absence of endogenous IL-10, mice acutely infected with Toxoplasma gondii succumb to a lethal immune response dependent upon CD4+ T cells and accompanied by overproduction of IL-12, IFN-γ, and TNF-α. J Immunol. 1996;157:798–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grammar A C, Bergman M C, Miura Y, Fujita K, Davis L S, Lipsky P E. The CD40 ligand expressed by human B cells costimulates B cell responses. J Immunol. 1995;154:4996–5010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grewal I S, Flavell R A. The role of CD40 ligand in costimulation and T-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 1996;153:85–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guery J C, Ria F, Galbiati F, Adorini L. Normal B cells fail to secrete interleukin-12. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1632–1639. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaiswal A I, Croft M. CD40 ligand induction on T cell subsets by peptide-presenting B cells: implications for development of the primary T and B cell response. J Immunol. 1997;159:2282–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson-Leger C, Christensen J, Klaus G G. CD28 co-stimulation stabilizes the expression of the CD40 ligand on T cells. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1083–1091. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.8.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamesaki H, Zwiebel J A, Reed J C, Cossman J. Role of bcl-2 and IL-5 in the regulation of anti-IgM-induced growth arrest and apoptosis in immature B cell lines. A cooperative regulation model for B cell clonal deletion. J Immunol. 1994;152:3294–3305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlen S, De Boer M L, Lipscombe R J, Lutz W, Mordvinov V A, Sanderson C J. Biological and molecular characteristics of interleukin-5 and its receptor. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;16:227–247. doi: 10.3109/08830189809042996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kehry M R, Hodgkin P D. Helper T cells: delivery of cell contact and lymphokine-dependent signals to B cells. Semin Immunol. 1993;5:393–400. doi: 10.1006/smim.1993.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi M, Fitz L, Ryan M, Hewik R M, Clark S C, Chan S, Louden R, Sherman F, Perussia B, Trinchieri G. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biological effects on human lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170:827–845. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koike M, Takatsu K. IL-5 and its receptor: which role do they play in the immune response? Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1994;104:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000236702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopf M, Brombacher F, Hodgkin P D, Ramsay A J, Milbourne E A, Dai W J, Ovington K S, Behm C A, Kohler G, Young I G, Matthaei K I. IL-5 deficient mice have a developmental defect in CD5+ B-1 cells and lack eosinophilia but have normal antibody and cytotoxic T cell responses. Immunity. 1996;4:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotsimbos A T C, Hamid Q. IL-5 and IL-5 receptor in asthma. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:75–91. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000800012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krahenbul J L, Remington J S. Immunology of toxoplasma and toxoplasmosis. In: Cohen S, Warren K S, editors. Immunology of parasitic infections. London, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1982. pp. 356–421. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luft B J, Remington J S. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:211–222. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahanty S, Nutman T. The biology of interleukin-5 and its receptor. Cancer Investig. 1993;11:624–634. doi: 10.3109/07357909309011681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall A J, Denkers E Y. Toxoplasma gondii triggers granulocyte-dependent, cytokine-mediated lethal shock in d-galactosamine sensitized mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1325–1333. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1325-1333.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCabe R, Remington J S. Toxoplasmosis: the time has come. N Eng J Med. 1988;380:313–315. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198802043180509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson R S, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaionnou V E. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naora H, Altin J G, Young I G. TCR-dependent and -independent signaling mechanisms differentially regulate lymphokine gene expression in the murine T helper clone D10.G4.1. J Immunol. 1994;152:5691–5702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neyer L E, Grunig G, Fort M, Remington J S, Rennick D, Hunter C A. Role of interleukin-10 in regulation of T-cell-dependent and T-cell-independent mechanisms of resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1675–1682. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1675-1682.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochiai K, Kagami M, Matumura R, Tomioka H. IL-5 but not interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) inhibit eosinophil apoptosis by up-regulation of bcl-2 expression. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107:198–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-884.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker S J, Roberts C W, Alexander J. CD8+ T cells are the major lymphocyte subpopulation involved in the protective immune response to Toxoplasma gondii in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;84:207–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb08150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purkerson J M, Isakson P C. Interleukin 5 (IL-5) provides a signal that is required in addition to IL-4 for isotype switching to immunoglobulin (Ig) G1 and IgE. J Exp Med. 1992;175:973–982. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purkerson J M, Isakson P C. A two-signal model for regulation of immunoglobulin isotype switching. FASEB J. 1992;6:3245–3252. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.14.1385241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reyes L, Frenkel J K. Specific and nonspecific mediation of protective immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. Infect Immun. 1987;55:856–863. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.856-863.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts C W, Ferguson D J P, Jebbari H, Satoskar A, Bluethmann H, Alexander J. Different roles for interleukin-4 during the course of Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:897–904. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.897-904.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sartori A, Ma X, Gri G, Showe L, Benjamin D, Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: an immunoregulatory cytokine produced by B cells and antigen-presenting cells. Methods. 1997;11:116–127. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scharton-Kersten T, Denkers E Y, Gazzinelli R T, Sher A. Role of IL-12 in the induction of cell-mediated immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. Res Immunol. 1995;146:539–545. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(96)83029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schattner E J, Mascarenhas J, Reyfman I, Koshy M, Woo C, Friedman S M, Crow M K. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells can express CD40 ligand and demonstrate T-cell type costimulatory capacity. Blood. 1998;91:2689–2697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schultze J L, Michalak S, Lowne J, Wong A, Gilleece M H, Gribben J G, Nadler L M. Human non-germinal center B cell interleukin (IL)-12 production is primarily regulated by T cell signals CD40 ligand, interferon gamma, and IL-10: role of B cells in the maintenance of T cell responses. J Exp Med. 1998;189:1–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shu U, Kiniwa M, Wu C Y, Malizewski C, Vezzio N, Hakimi J, Gately M, Delespesse G. Activated T cells induce interleukin-12 production by monocytes via CD40-CD40 ligand interaction. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1125–1128. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stern M, Meagher L, Savill J, Haslett C. Apoptosis in human eosinophils programmed cell death in the eosinophil leads to phagocytosis by macrophages and is modulated by IL-5. J Immunol. 1992;148:3543–3549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suzuki Y, Yang Q, Yang S, Nguuyen N, Lim S, Leisenfeld O, Kojima T, Remington J. IL-4 is protective against development of toxoplasmic encephalitis. J Immunol. 1996;157:2564–2569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swain S L, McKenzie D T, Dutton R W, Tonkonogy S L, English M. The role of IL4 and IL5: characterization of a distinct helper T cell subset that makes IL4 and IL5 (Th 2) and requires priming before induction of lymphokine secretion. Immunol Rev. 1988;102:77–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1988.tb00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taguchi T, Aicher W K, Fujihashi K, Yamamoto M, McGhee J R, Bluestone J A, Kiyono H. Novel function for intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, Murien CD3+ gamma/delta TCR+ T cells produce IFN-gamma and IL-5. J Immunol. 1991;147:3736–3744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takatsu K, Tominage A, Harada N, Mita S, Matsumoto M, Takahashi T, Kikuchi Y, Yamaguchi N. T cell-replacing factor (TRF)/interleukin 5 (IL-5): molecular and functional properties. Immunol Rev. 1988;102:107–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1988.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vitetta E S, Brooks K, Chen Y W, Isakson P, Jones S, Layton J, Mishra G C, Pure E, Weiss E, Word E, Yuan D, Tucker P, Uhr J W, Krammer P H. T cell derived lymphokines that induce IgM and IgG secretion in activated murine B cells. Immunol Rev. 1988;78:137–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1984.tb00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker C, Checkel J, Cammisuli S, Leibson P J, Gleich G J. IL-5 production by NK cells contributes to eosinophil infiltration in a mouse model of allergic inflammation. J Immunol. 1998;161:1962–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Warren H S, Kinnear B F, Phillips J H, Lanier L L. Production of IL-5 by human NK cells and regulation of IL-5 secretion by IL-4, IL-10, and IL-12. J Immunol. 1995;154:5144–5152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams C M, Coleman J W. Induced expression of mRNA for IL-5, IL-6, TNF-alpha, MIP-2 and IFN-gamma in immunologically activated rat peritoneal mast cells: inhibition by dexamethasone and cyclosporin A. Immunology. 1995;86:244–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wykes M, Poudrier J, Lindstedt R, Gray D. Regulation of cytoplasmic, surface and soluble forms of CD40 ligand in mouse B cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:548–559. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<548::AID-IMMU548>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wynn T A, Eltoum I, Cheever A W, Lewis F A, Gause W C, Sher A. Analysis of cytokine mRNA expression during primary granuloma formation induced by eggs of Schistosoma mansoni. J Immunol. 1993;151:1430–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wysocka M, Kubin M, Vieira L Q, Ozmen L, Garotta G, Scott P, Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 is required for interferon-γ production and lethality in lipopolysaccharide-induced shock in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:672–676. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]