Abstract

LHF-535 is a small molecule antiviral currently in development for the treatment of Lassa fever, a zoonotic disease endemic in West Africa that generates significant morbidity and mortality. Current treatment options are inadequate, and there are no approved therapeutics or vaccines for Lassa fever. LHF-535 was evaluated in a lethal guinea pig model of Lassa pathogenesis, using once-daily administration of a fixed dose (50 mg/kg/day) initiating either 1 or 3 days after inoculation with a lethal dose of Lassa virus. LHF-535 reduced viremia and clinical signs and protected all animals from lethality. A subset of surviving animals was rechallenged four months later with a second lethal challenge of Lassa virus and were found to be protected from disease. LHF-535 pharmacokinetics at the protective dose in guinea pigs showed plasma concentrations well within the range observed in clinical trials in healthy volunteers, supporting the continued development of LHF-535 as a Lassa therapeutic.

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Microbiology

Introduction

Lassa fever, an acute viral hemorrhagic fever disease endemic in West Africa, is responsible for a significant disease burden. While the true number of cases is uncertain, public health officials often cite an estimated impact of several hundred thousand cases and several thousand deaths annually1,2. One recent study suggests that Lassa virus, a member of the family Arenaviridae and the etiologic agent of Lassa fever, is one of the highest known zoonotic spillover threats3. The current approach to treating Lassa fever is supportive therapy that is often combined with off-label use of the broad-spectrum antiviral drug ribavirin. However, the efficacy of ribavirin for treating Lassa fever is unproven, and outbreaks of the disease are often associated with high rates of mortality, even among ribavirin-treated patients4. This was acutely evident during a recent outbreak in Nigeria in which the case fatality rate was 21% among patients hospitalized with a confirmed case of Lassa fever and treated with ribavirin5. Recent analyses have questioned the data supporting the clinical effectiveness of ribavirin and have suggested that ribavirin may actually be detrimental, particularly in milder cases6,7. To address the need for better therapeutic options, we are developing LHF-535, a small-molecule antiviral drug candidate that targets the envelope glycoprotein of Lassa virus.

LHF-535 is an analog of the previously characterized benzimidazole derivative ST-1938–11, which acts as an antiviral drug by inhibiting arenavirus entry into host cells. Entry is a multi-step process that is mediated by the viral envelope glycoprotein complex, which consists of a receptor-binding subunit (GP1), a transmembrane fusion subunit (GP2), and a stable signal peptide (SSP) that interacts with GP212. After GP1 binds to a cell surface receptor, the virus is endocytosed and GP2 undergoes a pH-dependent conformational rearrangement that facilitates fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes. LHF-535 and ST-193 are thought to bind to and stabilize an SSP-GP2 prefusion structure, thereby suppressing the rearrangement of GP2 that is necessary for membrane fusion.

LHF-535 has been optimized for pharmacokinetic properties, antiviral potency, and broad-spectrum activity against arenaviruses. The compound has potent activity against lentiviral pseudotype viruses expressing envelope glycoproteins from across the Lassa virus phylogeny or from New World clade B arenaviruses associated with hemorrhagic fever, such as Junín, and Machupo13. In addition, a daily oral dose of LHF-535 at 10 mg/kg protects AG129 mice from a lethal dose of Tacaribe virus, an arenavirus closely related to Junín virus13.

Although chimeric, related, or attenuated viruses are useful for early evaluation of antiviral therapies or for investigating aspects of arenavirus pathogenesis, studies using viruses that are authentic human pathogens provide important validation. Here, we evaluated the antiviral efficacy of LHF-535 in a well-characterized guinea pig model of Lassa fever. In this model, infection of strain 13 guinea pigs with Lassa virus results in a uniformly fatal disease that is characterized by fever, weight loss, interstitial pneumonia, and high viral titers in the lung, spleen, and lymph nodes14,15. This small animal model has been used extensively to characterize candidate medical countermeasures8,16,17. We show that LHF-535 protected 100% of guinea pigs infected with a lethal dose of Lassa virus, even when treatment was initiated 3 days after infection. In addition to surviving the initial infection, LHF-535-treated animals developed protective immunity against rechallenge. These findings support further development of LHF-535 as a new treatment for Lassa fever.

Results

LHF-535 protects guinea pigs against lethal Lassa virus infection

Strain 13 guinea pigs were used to evaluate the antiviral efficacy of LHF-535 when administered 24 or 72 h after infection with a lethal dose of Lassa virus. All animals were acclimated for 3 days in BSL-4 animal housing prior to the start of the study and on Day 0 were infected with a target dose of 1000 pfu of guinea pig-adapted Lassa virus (Josiah strain) by subcutaneous injection. One animal in the control group (Group 1) died after reviving from anesthesia and was excluded from analysis. The remaining animals in the control group received a daily dose of vehicle alone beginning on Day 1 after infection. Animals in the experimental groups received a daily dose of LHF-535 (50 mg/kg) beginning on Day 1 (Group 2) or Day 3 (Group 3) after infection. All surviving animals in each group continued to receive daily treatment until Day 22.

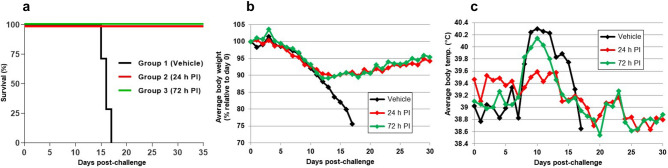

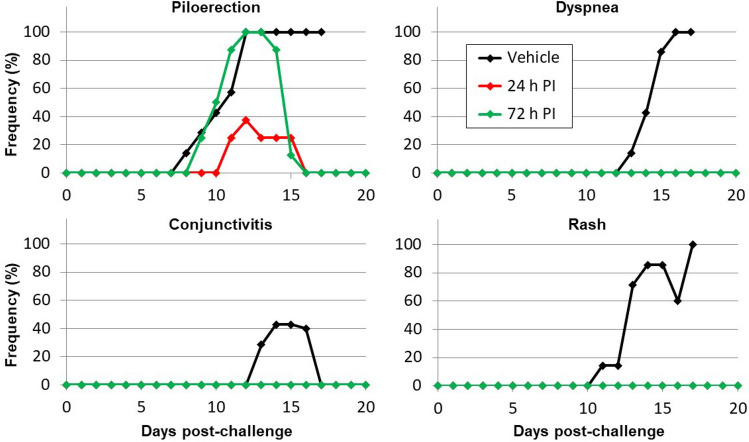

Animals in the control group exhibited progressive weight loss (> 20%), became febrile between Day 8 and Day 10 (body temperature > 39.5 °C), and succumbed to Lassa virus infection between Day 15 and Day 17 (Fig. 1), with a mean time-to-death (MTD) of 16.0 days. Animals treated with LHF-535 initially lost weight and became febrile, but weight loss stabilized by Day 12, and for most animals, fevers resolved by Day 14. All animals treated with LHF-535 survived the infection. Clinical observations for animals in the control group were more frequent than for animals treated with LHF-535 (Fig. 2). The majority of animals in the control group became lethargic, developed a rough coat and rash, and exhibited labored breathing. These clinical signs were absent from animals treated with LHF-535, although transient piloerection was noted.

Figure 1.

Study outcomes. (a) Survival by group (daily LHF-535 administration initiated 24 h post-infection (PI) for group 2 and 72 h PI for group 3); (b) Average body weight; and (c) Average body temperature. Body temperature recorded in one group 3 animal was consistently 2.5 °C lower than the other animals in the group and was excluded from the averages shown here; had it been included, average group 3 temperatures would be 0.3 °C lower.

Figure 2.

Frequency of clinical signs observed following viral challenge by group.

LHF-535 reduces serum viremia

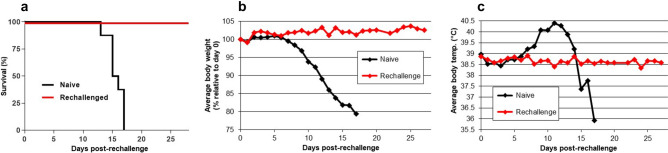

All animals in Group 1 and Group 3 became viremic after infection (Fig. 3). At Day 7, the average (geometric mean) viremia was 2.8 × 103 pfu/ml in the control group and 4.1 × 102 pfu/ml in Group 3. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001). In contrast, no virus was detected in the serum of animals that received LHF-535 1 day after infection (Group 2). At Day 12, the average viremia was 4.8 × 104 pfu/ml in the control group, whereas virus was detected in the serum of only 5 of 8 animals in Group 2, and 3 of 8 animals in Group 3. The differences between groups 1 and 3 and the control group were statistically significant (p < 0.001). No virus was detected in the serum of any LHF-535-treated animal at the study endpoint (Day 35 after infection).

Figure 3.

Viral titers in serum at 7, 12, and 35 days post-infection. The limit of detection (25 pfu/mL) is indicated by the dashed line and short horizontal bars show group medians.

Surviving LHF-535-treated animals are immune to Lassa virus rechallenge

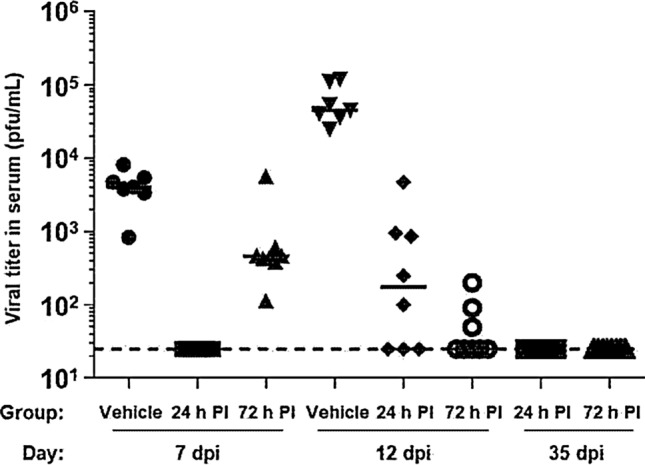

Previous studies have demonstrated that guinea pigs that survive Lassa virus infection develop neutralizing antibodies to the virus8,15. To test whether surviving LHF-535-treated animals develop protective immunity against rechallenge, eight of the surviving animals were held until 120 days after infection (7.5 times the MTD of the vehicle-treated animals), at which time they were again challenged with a lethal dose of Lassa virus. As a control group, eight age-matched naive animals were infected with Lassa virus in the same manner.

All eight of the LHF-535-treated animals that survived the initial infection were protected against rechallenge and exhibited no significant change in body weight or temperature over a 28-day period after infection (Fig. 4). In contrast, animals in the naive control group exhibited progressive weight loss and became febrile, and there was 100% mortality in this group by 17 days after infection, with an MTD of 15.6 days. There were no clinical observations in the rechallenged group except for a single note of piloerection in one animal at ten days post-rechallenge. LHF-535 therefore protected guinea pigs from a lethal dose of Lassa virus, and all surviving animals developed protective immunity against rechallenge with the same virus.

Figure 4.

Study outcomes following rechallenge. (a) Survival by group, comparing outcome of rechallenged animals with age-matched naive controls; (b) Average body weight; and (c) Average body temperature. Body temperature recorded in one rechallenged animal was consistently 2.5 °C lower than the other animals in the group and was excluded from the averages shown here; had it been included, average rechallenged animal temperatures would be 0.3 °C lower.

Pharmacokinetics of LHF-535 in guinea pigs

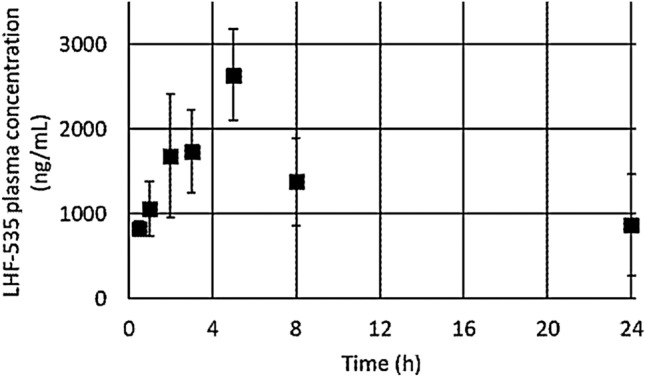

The pharmacokinetics of LHF-535 was evaluated from a single intraperitoneal dose of 50 mg/kg in healthy outbred Hartley guinea pigs using the same formulation as described. Plasma LHF-535 reached a Cmax of 2637 ng/mL at a Tmax of 5 h, generating an average 24-h area under the plasma concentration curve (AUC0–24 h) of 31.7 μg·h/mL (Fig. 5). Intraperitoneal administration of other LHF-535 formulations in guinea pigs have exhibited similar pharmacokinetics. Repeat daily intraperitoneal dosing showed similar AUC0–24 h values after 13 or 20 days (median 50.7 μg·h/mL, N = 8) compared to AUC0–24 h values after the first dose (median 51.0 μg·h/mL, N = 12). Similarly, plasma concentrations at 24 h post-dosing (C24, equivalent to Cmin or trough exposure) following the first dose (average 485 ng/mL, median 243 ng/mL, N = 20) are comparable to those after 7 to 20 daily doses (average 426 ng/mL, median 253 ng/mL, N = 16).

Figure 5.

LHF-535 pharmacokinetics following intraperitoneal administration at a dose of 50 mg/kg in Hartley guinea pigs. Markers indicate average plasma concentration of three animals and error bars denote standard deviation.

Discussion

There are no approved drugs or vaccines to treat or protect against Lassa fever, and the World Health Organization has identified the disease as a top priority for research and development efforts18. Here, we showed that the antiviral drug candidate LHF-535, a small-molecule inhibitor of arenavirus entry, protected strain 13 guinea pigs from a lethal dose of Lassa virus. LHF-535 is an optimized analog of ST-193, which was previously evaluated for antiviral activity against Lassa virus in the strain 13 guinea pig model8. In the prior study, ST-193 was administered by intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 25 or 80 mg/kg/day beginning 1 h prior to a lethal dose of Lassa virus. Both doses of ST-193 provided a similar level of protection, and the overall survival rate for animals treated with ST-193 was 62.5%. The 100% survival rate for LHF-535-treated animals may be due to the increased potency of the optimized drug candidate13.

In addition to surviving Lassa virus infection, LHF-535-treated animals showed fewer clinical signs of disease, including reduced fever, weight loss, and viremia relative to animals treated with vehicle alone. The reduction in viremia was particularly evident, and 3 of 8 animals that received LHF-535 1 day after infection had no detectable virus at any time point evaluated. No infectious virus was detected in the serum of any LHF-535-treated animal at the endpoint of the study. However, more sensitive methods such as RT-PCR might have shown the presence of viral RNA; also, we cannot rule out the possibility of viral persistence in a non-blood compartment such as the central nervous system. The ability of LHF-535 to reduce viremia may be important for treating patients with Lassa fever, where high viral load directly correlates with poor clinical outcome19–21. The effect of LHF-535 on viral load is also in contrast to that of ribavirin, which often mediates only modest effects on viremia in animal models of Lassa fever8,22. In immunocompromised mouse models of Lassa virus infection, ribavirin appears to act by protecting infected cells from dying, which may result in reduced damage to liver tissue22,23.

ST-193-treated guinea pigs that survive Lassa virus infection develop a Lassa-virus-specific IgG2 response starting 21 days after infection, and serum samples from these animals have neutralizing activity against the virus8. Similarly, out-bred Hartley guinea pigs that survive Lassa virus infection also develop neutralizing antibody activity late in convalescence (> 32 days after infection)15. However, the question of whether surviving animals develop protective immunity against rechallenge has not been examined. Here, we showed that surviving LHF-535-treated animals were immune to Lassa virus rechallenge and exhibited no significant change in body weight or temperature after infection.

In humans, survival from Lassa virus infection is thought to produce life-long protective immunity24. Seropositive individuals have Lassa-virus-specific CD4+ T cells, and a T cell response is considered to be essential for controlling Lassa virus infection25,26. Although a neutralizing humoral response is also present in convalescent serum from patients surviving Lassa fever27, the role of neutralizing antibodies in controlling human infections is less clear. High antibody titer does not correlate with recovery21, and passive transfer of survivor plasma does protect against Lassa virus infection28. However, a cocktail of human monoclonal antibodies that target the Lassa virus glycoprotein provides protection in guinea pig and nonhuman primate models of Lassa fever29,30.

LHF-535 protected 100% of guinea pigs when treatment was initiated 3 days after infection. The full duration of the effective treatment window is not known, and alternative dosing regimens remain to be examined. The ability to initiate successful treatment multiple days after infection will be important for treating Lassa fever in humans, where the time from infection to initiation of care is highly variable19. Treatment with ribavirin, the current standard of care for Lassa fever, has been called into serious question6,7. The pharmacokinetics of LHF-535 in guinea pigs corresponding to an efficacious dosing regimen in a lethal challenge model will be informative for guiding a target clinical exposure. Phase I clinical trials of LHF-535 in healthy volunteers, using both single and 14-day dosing, established that exposures in excess of the guinea pig exposures reported here can be safely achieved (manuscript in preparation). Taken together, these results support the further development of LHF-535 as a new treatment for Lassa fever.

Methods

Ethics statement

Research was conducted at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). USAMRIID’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved the protocol in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, Public Health Service (PHS) assurance, and all other Federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The USAMRIID facility is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC) and adheres to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 2011.

Biosafety

All work with Lassa virus and potentially infectious materials derived from animals was conducted in a biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory. Virus inactivation prior to the removal of samples from the BSL-4 laboratory was performed according to USAMRIID standard operating procedures.

Animals

Male and female strain 13 guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) were obtained from the USAMRIID in-house colony; animals ranged in age from 3 to 5 months and in weight from 570 to 780 g at study initiation. Five days prior to the start of the study, the animals were implanted subcutaneously with microchip transponders for identification and temperature measurement. Animals were randomized into 3 groups of 8 animals each, and groups were balanced by weight and sex to minimize bias. Animals were offered standard guinea pig feed and water ad libitum, as well as daily enrichments such as spinach, alfalfa, or fruit. Animal procedures were performed in accordance with recommended set of ARRIVE guidelines.

Virus, challenge inoculum, and plaque assay

A guinea-pig-adapted clinical isolate of Lassa virus (Josiah strain) was used for these studies. The virus originated from a fatal human case of Lassa fever and was adapted to provide uniform lethality in strain 13 guinea pigs14,15. The challenge stock was prepared by propagation in Vero cell culture and screened by polymerase chain reaction using primer sets specific for a variety of to potential contaminating viruses, transmission electron microscopy to evaluate virus particle integrity, endotoxin, mycoplasma, and bacterial contamination assessments, and deep sequencing to identify viral quasi species. The challenge inoculum was prepared by diluting the challenge stock in sterile 0.9% normal saline. The titers of the challenge stock, dilution series, and challenge inoculum were determined by using a neutral-red-based Vero cell plaque assay14. Viral titers in serum collected from animals during the course of the study were also determined by this method.

LHF-535

LHF-535 is a small-molecule compound of the bis-substituted benzimidazole class13. A stock suspension of micronized LHF-535 was prepared at 10 mg/ml in a vehicle consisting of 0.5% Methocel E15 LV (DuPont) and 1% Tween 80 and stored at 4 °C until use. Micronization is used to reduce particle size, improve dissolution rate, and enhance reproducibility. Before use, the suspension was briefly sonicated and allowed to equilibrate to room temperature. Control formulation (vehicle alone) was prepared and stored in parallel.

Antiviral efficacy and rechallenge studies

Guinea pigs were randomized into 3 groups of 8 animals each (4 males and 4 females) and moved to BSL-4 containment 3 days prior to the start of the study (Day − 3). On Day 0, animals were anesthetized and subcutaneously injected with a target dose of 1,000 plaque forming units (pfu) of Lassa virus in 200 μl of normal saline. Animals in the vehicle control group (Group 1) received a daily intraperitoneal injection of formulation buffer alone (5 ml/kg) beginning on Day 1. Animals in the remaining groups received a daily intraperitoneal injection of LHF-535 (50 mg/kg) beginning on Day 1 (Group 2) or Day 3 (Group 3) after infection. For all groups, surviving animals continued to receive daily treatment through Day 22. Animals were observed twice daily and clinical signs were recorded, including piloerection; anorexia, dehydration, or visible weight loss (≥ 10%); rash; orbital exudates (conjunctivitis); ataxia; and dyspnea (labored breathing). Body weight and temperature measurements were recorded daily. Blood samples were collected at Days 0, 7, 12, and at euthanasia. Animals were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of a KAX cocktail (60.6 mg/mL ketamine HCl, 0.6 mg/mL acepromazine maleate, and 6.67 mg/mL xylazine HCl) prior to sampling (0.2 mL KAX) or euthanasia procedures (0.3 mL KAX). Animals were euthanized when humane endpoint criteria (non-ambulatory, respiratory distress, hypothermia, excessive body weight loss) were met in accordance with the IACUC-approved protocol, or at the scheduled study endpoint.

The efficacy study was ended at Day 35. Eight of the surviving LHF-535-treated animals were held until 120 days after infection (4 from each of the two LHF-535 treatment groups), at which time they were rechallenged with a lethal dose of Lassa virus. Eight age-matched naive animals were infected with Lassa virus in the same manner. The methods for virus infection and monitoring of animals after infection were the same as described for the efficacy study. The rechallenge study was ended 28 days after rechallenge with Lassa virus.

Pharmacokinetics

LHF-535 was prepared as described (10 mg/ml) and administered to female Hartley guinea pigs (N = 6) by intraperitoneal injection using a dosing volume of 5 ml per kg body weight for a dose of 50 mg/kg. Serial bleeding (0.2 ml) was performed via saphenous vein, alternating sampling from 3 animals for each time point. Blood was collected in lithium heparin plasma separator tubes and stored on ice until separated into plasma at 14,000 × g for 2 min. at 4 °C. Plasma samples were stored at -20 °C until analysis. Plasma samples were processed for analysis by thawing at room temperature followed by mixing with a tenfold v/v excess of methanol with subsequent filtration through 96-well Phenomenex Phree plates. The filtrates were analyzed by LCMS/MS on a Shimadzu LC-20AD HPLC system coupled to a Sciex API-5000 mass spectrometer. The analytical column (Agilent Poroshell C18; 2.1 × 100 mm) was eluted with a gradient of 5 to 100% Mobile Phase B over 11 min at 0.3 mL/min; Mobile Phase A: 95:5 H2O/CH3CN + 0.1% v/v formic acid; Mobile Phase B: CH3CN + 0.1% v/v formic acid. The LHF-535 concentration was determined by plotting the peak area of the mass spec transition of m/z = 413.2 to 353.2 for each plasma sample versus a standard curve from guinea pig plasma samples spiked with LHF-535 (500 to 50,000 ng/mL). All standards were diluted 1:100 after filtration through the Phree plate, whereas pharmacokinetic samples were diluted as necessary to fall within the concentration range of the standard curve. AUC0–24 h (area under the time-concentration curve for the 24 h period after dosing) was calculated using the average plasma concentration for each time point and a combination linear-log trapezoidal method (linear for segments of the curve in which concentration increases and logarithmic for segments of the curve in which concentration decreases). AUC0–24 h is the sum of the AUC from each of the segments comprising that time span.

Statistical analysis

Appropriate group size was determined to be eight animals per group to ensure adequate (> 80%) statistical power. To determine statistically significant differences between treatment and control groups for plaque assay data, multiple, unpaired t-tests were performed on sequentially collected samples.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by Wellcome Trust Translation Fund award WT-200439/Z/16/Z. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: K.A.C., I.G.M., E.T., K.H.L., K.M.B., S.M.A.; Performed the experiments: K.A.C., E.R.W., J.P.; Analyzed the data: K.A.C., J.P., I.G.M., M.J.K., S.M.A.; Developed reagents/materials/analysis tools: K.A.C., E.R.W., J.P.; Contributed to writing the manuscript: K.A.C., M.J.K., S.M.A.; All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

Data analyzed in this work are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

JP, IGM, EJT, KHL, MJK, KMB, and SMA are or were employees of Kineta. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.McCormick JB. Epidemiology and control of Lassa fever. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1987;134:69–78. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71726-0_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick JB, Webb PA, Krebs JW, Johnson KM, Smith ES. A prospective study of the epidemiology and ecology of Lassa fever. J. Infect. Dis. 1987;155:437–444. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grange ZL, et al. Ranking the risk of animal-to-human spillover for newly discovered viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2002324118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002324118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaffer JG, et al. Lassa fever in post-conflict Sierra Leone. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8:e2748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilori EA, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical features of Lassa fever outbreak in Nigeria, January 1-May 6, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019;25:1066–1074. doi: 10.3201/eid2506.181035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eberhardt KA, et al. Ribavirin for the treatment of Lassa fever: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;87:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salam AP, et al. Time to reconsider the role of ribavirin in Lassa fever. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021;15:e0009522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cashman KA, et al. Evaluation of Lassa antiviral compound ST-193 in a guinea pig model. Antiviral Res. 2011;90:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larson RA, et al. Identification of a broad-spectrum arenavirus entry inhibitor. J. Virol. 2008;82:10768–10775. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00941-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas CJ, et al. A specific interaction of small molecule entry inhibitors with the envelope glycoprotein complex of the Junín hemorrhagic fever arenavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:6192–6200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.196428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.York J, Dai D, Amberg SM, Nunberg JH. pH-induced activation of arenavirus membrane fusion is antagonized by small-molecule inhibitors. J. Virol. 2008;82:10932–10939. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01140-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunberg JH, York J. The curious case of arenavirus entry, and its inhibition. Viruses. 2012;4:83–101. doi: 10.3390/v4010083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madu IG, et al. A potent Lassa virus antiviral targets an arenavirus virulence determinant. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007439. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell TM, et al. Temporal progression of lesions in guinea pigs infected with Lassa virus. Vet. Pathol. 2017;54:549–562. doi: 10.1177/0300985816677153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahrling PB, Smith S, Hesse RA, Rhoderick JB. Pathogenesis of Lassa virus infection in guinea pigs. Infect. Immun. 1982;37:771–778. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.771-778.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cashman KA, et al. Enhanced efficacy of a codon-optimized DNA vaccine encoding the glycoprotein precursor gene of Lassa virus in a guinea pig disease model when delivered by dermal electroporation. Vaccines (Basel) 2013;1:262–277. doi: 10.3390/vaccines1030262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cashman KA, et al. DNA vaccines elicit durable protective immunity against individual or simultaneous infections with Lassa and Ebola viruses in guinea pigs. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017;13:3010–3019. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1382780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Annual review of diseases prioritized under the Research and Development Blueprint. (2018).

- 19.Asogun DA, et al. Molecular diagnostics for Lassa fever at Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, Nigeria: Lessons learnt from two years of laboratory operation. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6:e1839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duvignaud A, et al. Lassa fever outcomes and prognostic factors in Nigeria (LASCOPE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob. Health. 2021;9:e469–e478. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30518-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson KM, et al. Clinical virology of Lassa fever in hospitalized patients. J. Infect. Dis. 1987;155:456–464. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrillo-Bustamante P, et al. Determining ribavirin's mechanism of action against Lassa virus infection. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:11693. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10198-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oestereich L, et al. Efficacy of favipiravir alone and in combination with ribavirin in a lethal, immunocompetent mouse model of Lassa fever. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;213:934–938. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallam HJ, et al. Baseline mapping of Lassa fever virology, epidemiology and vaccine research and development. NPJ. Vaccines. 2018;3:11. doi: 10.1038/s41541-018-0049-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ter Meulen J, et al. Characterization of human CD4(+) T-cell clones recognizing conserved and variable epitopes of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein. J. Virol. 2000;74:2186–2192. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2186-2192.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ter Meulen J, et al. Old and New World arenaviruses share a highly conserved epitope in the fusion domain of the glycoprotein 2, which is recognized by Lassa virus-specific human CD4+ T-cell clones. Virology. 2004;321:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson JE, et al. Most neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies target novel epitopes requiring both Lassa virus glycoprotein subunits. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11544. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCormick, J. B. et al. Lassa fever. Effective therapy with ribavirin. N. Engl. J. Med.314, 20–26 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Cross RW, et al. Treatment of Lassa virus infection in outbred guinea pigs with first-in-class human monoclonal antibodies. Antiviral Res. 2016;133:218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mire CE, et al. Human-monoclonal-antibody therapy protects nonhuman primates against advanced Lassa fever. Nat. Med. 2017;23:1146–1149. doi: 10.1038/nm.4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data analyzed in this work are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.