Abstract

Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial group in the US, but their health disparities are often overlooked. Although their needs for transplantable organs are substantial, they have the lowest rates of organ donation per million compared to other Americans by race. To better understand Asian Americans’ disposition towards organ donation, a self-administered survey was developed based on formative data collection and guidance from a Community Advisory Board composed of Asian American stakeholders. The instrument was deployed online, and quota sampling based on the 2017 American Community Survey was used to achieve a sample representative (N=899) of the Asian American population. Bivariate tests using logistic regression and the chi-square test of independence were performed. Over half (58.1%) of respondents were willing to be organ donors. A majority (81.8%) expressed a willingness to donate a family member’s organs, but enthusiasm depended on the family member’s donor wishes. Only 9.5% of respondents indicated that the decision to donate their organs was theirs alone to make; the remainder would involve at least one other family member. Other key sociodemographic associations were found. This study demonstrates both the diversity of Asian Americans but also the centrality of the family’s role in making decisions about organ donation. Practice and research considerations for the field are also presented.

Keywords: organ donation, organ transplantation, Asian Americans, decision-making, survey methods

1. INTRODUCTION

Although Asian Americans (AAs) currently comprise 6.8% of the U.S. population [1], they are expected to grow faster than any other single racial group at a rate of 128% over the next 15 years [2]. Yet, addressing inequities in organ donation and transplantation have largely focused on barriers and challenges to donor designation and family authorization among Black and Latinx Americans [3–23]. Few studies have pointed to heightened reluctance about Asian Americans’ willingness for organ donation,[24–29] but these were not generalizable, focused on specific Asian ethnic groups, and do not account for the complexity of the recent Asian American experience. Our collective understanding of the transplant needs of AAs is considerably lower than that for other ethnic minority groups and demands greater attention.

Inequities between AA patients in need of a transplant and other Americans are seen across the spectrum of transplantation outcomes. AAs are overrepresented on the national transplantation waitlist, almost double their proportion of the general population [30]. Although the allocation of transplantable organs relies on histocompatibility rather than racial or ethnic background,[31] recipients with the B blood type are more disadvantaged by a shortage of compatible organs.[26] This blood group type is most commonly found in Asian and African Americans. Further, research has shown that inequity remains although new allocation policies have been implemented to address disparities.[32] In 2021, AAs composed 5.2% of the liver and 9.4% of the kidney transplant waitlists but received only 4.2% and 7.2% of liver and kidney transplants [30]. Median wait times from listing to transplantation are also longer for AAs than those of other groups, with recent data indicating a median wait time of 739 days for liver transplant compared to 374 days for Black Americans [33]. Among the sickest liver patients based on Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores, AAs have the lowest rates of transplantation of any ethnic/racial group in the US [34]. AAs are also more likely than their White counterparts to receive an extended criteria organ [35] and significantly more likely to be hospitalized at time of wait-listing [36], making transplantation less likely [37].

Given AAs’ considerable transplant needs, it would be expected that their enthusiasm for organ donation would be higher. However AAs account for only 2.6% of all deceased donors, with the lowest rates of organ donation per million (14.7, compared to 25.6 for Hispanics, 27.1 for Whites, and 35.4 for African Americans) [38,39]. One review of data from the United Network for Organ Sharing projected that if donation from Asians occurred at the same rate as White donors from 2008 to 2011,[40] an additional 878 organs would have been available for transplantation in that same period,[41] which would have had widespread benefit. Given the persistent shortage of transplantable solid organs, these statistics underscore the need to increase parity between the high transplant needs of AAs and their low rates of donation [1].

The National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices (NSODAP), commissioned by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and conducted by the Gallup Organization, indicates some of the challenges to increasing donation rates among AAs. The 2019 NSODAP surveyed 1,045 Asian American respondents and revealed that 88.2% supported organ donation as a general practice, but only 51.9% would want to donate their organs after death [42]. Fifty-four percent of respondents reported they would donate a family member’s organs if the donor’s wishes were unknown, and more (77.2%) would do so only if donor wishes were known. The survey elucidated AAs’ disposition towards organ donation; however, no sample weighting accommodated the breadth of Asian ethnicities represented in the US population. A more nuanced exploration of the organ donation attitudes and behaviors among a diverse sample of Americans of Asian descent is required to develop culturally and linguistically relevant practices to increase rates of organ donation among AA subgroups.

This report details findings of the largest examination on organ donor disposition among AAs to date. As part of a larger study on attitudes and self-reported behaviors of AAs regarding organ and tissue donation for transplantation, the results presented here comprise a critical knowledge base about AAs’ willingness to donate their own and family members’ organs and tissue upon death. The predominant role of the family is also explored, and key associations between donation disposition and sociodemographic characteristics are identified.

2. METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1. Survey Development

The overall study design was guided by the Tripartite Model of Attitude Structure,[43] as revised by Eagly and Chaiken.[44] The final national survey was the result of formative research and community-engaged efforts to ensure that study implementation was culturally appropriate and targeted to AAs. At the project’s outset, we formed partnerships with local Asian American community organizations and convened a 12-member Community Advisory Board (CAB), which represented the largest AA communities in the Philadelphia metropolitan area. The partner organizations and CAB provided guidance on recruitment procedures and reviewed data collection materials for translational accuracy. To inform survey development, focus group interviews were conducted with AA participants representing multiple ethnic origins, age groups, immigration experiences, and education levels. Focus group findings included themes specific to AA populations, such as primacy of the family, a belief in a black market of organs in their home countries, isolation from mainstream American society, and mistrust of the medical and donation systems [45]. Focus group results were reviewed with the CAB to develop the domains of the national survey.

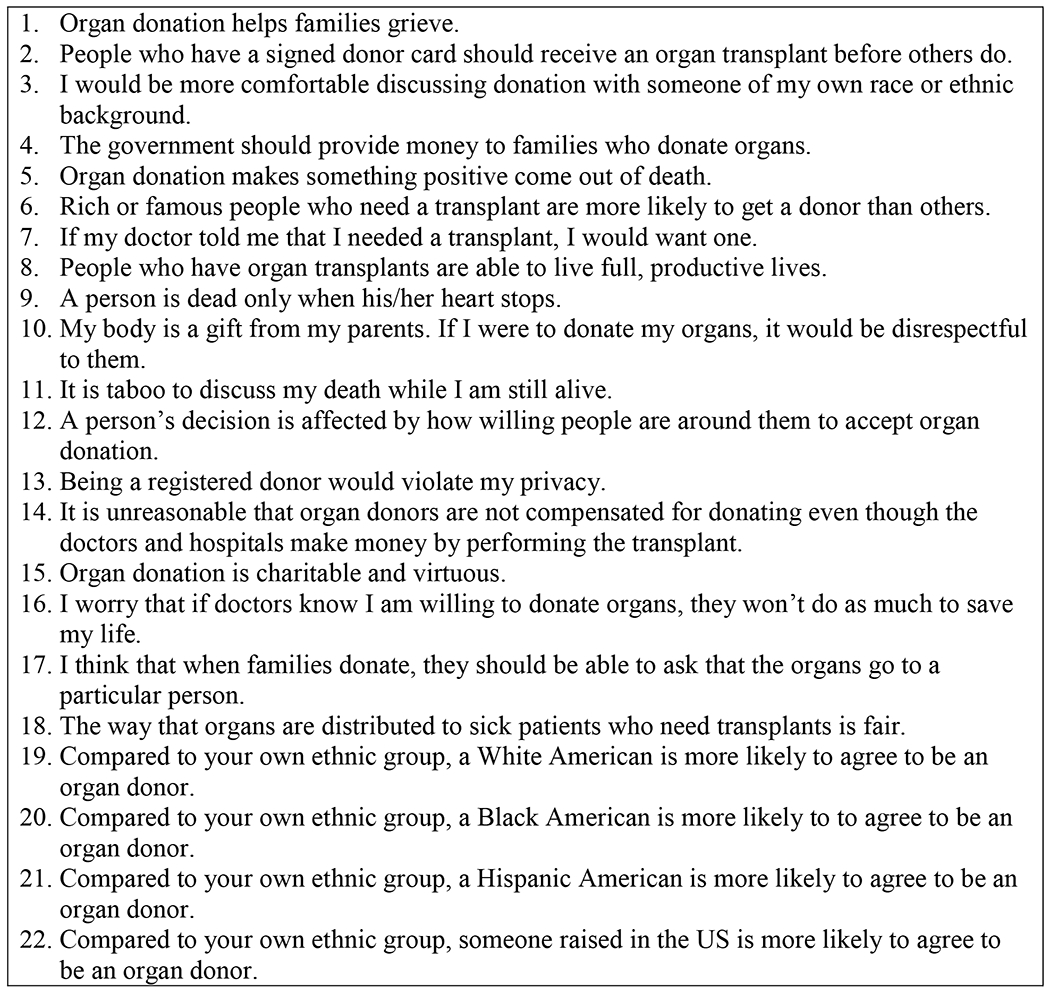

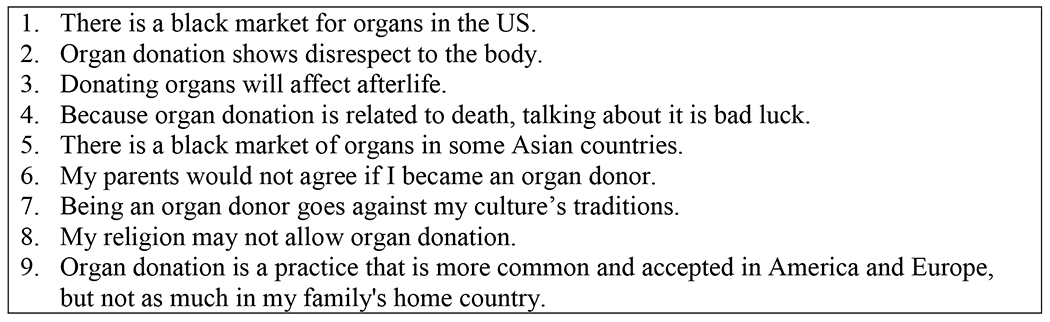

Validated measures from past research were included to facilitate comparisons with other racial/ethnic groups [9,18,46,47]. Slider bars, rather than Likert scales, were used to mitigate social desirability and “courtesy” biases among the target population [48–53]. Slide values ranged from 0 (strong disagreement) to 100 (strong agreement) and addressed beliefs (22 items; range 0-2200) and concerns about organ donation (9 items; range 0-900). Higher belief scores represented a more positive view whereas higher concern scores indicated a greater level of concern about donation. After 2 weeks of beta-testing and CAB input, the final survey was composed of a total of 33 questions with 15 branching follow-up questions. Specifically, there were 13 demographic items, 10 knowledge questions (true/false), 7 yes/no or short answer items regarding organ donor status and preferences, and 3 attitudinal scales containing a total of 38 items.

Respondents were given the option to complete the survey in English, Vietnamese, or simplified Chinese. In consultation with CAB members, the survey was made available in these languages to account for the linguistic needs of potential participants representing Asian ethnicities with the highest representation in the US. Since English is used in an official capacity in the Philippines and for most of South Asia, the survey was not translated into Tagalog or South Asian languages. Vietnamese and simplified Chinese versions of the survey were prepared by a professional translation firm with expertise in healthcare, medical, and research settings. Translations were reviewed by the CAB, whose members made minor adjustments to make phrasing less technical and more understandable.

2.2. Recruitment

Between June and October 2019, an online market research panel hosted and recruited through Qualtrics, Inc. was utilized to target a random and nationally representative sample of adults, who self-identified as Asian American. Participants were compensated directly by Qualtrics based on a format they chose during panel enrollment with the company and earned points for various rewards systems, such as shopping or travel points. Participants were presented with an informed consent statement to which they indicated agreement before being able to proceed to the online survey. The research was deemed exempt by the Temple University Institutional Review Board (#24584).

2.3. Analytical Approach

All statistical estimation procedures, tables, and data preparations were performed using SAS 9.4 with survey procedures to incorporate sample weights into our inferences. Bivariate tests performed included logistic regression and the chi-square test of independence. Scale scores were standardized for interpretation and results were considered significant at α=.05. Quota sampling was used to improve representativeness on the distribution of age and education within specific ethnic groups based on the 2017 American Community Survey of the US Census Bureau. To ensure adequate representation with respect to the underlying US population, we also weighted respondents within their ethnicity by dividing the corresponding age group population percent with same groups percent in the sample. This allows for samples that might have disproportional representations of subgroups to be calibrated to represent the corresponding groups [54].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample

In total, 2,588 responses were gathered in a first (n=1,564) and second wave (n=1,024), spanning 3 and 16 consecutive days, respectively. Average survey completion time was 12.5 minutes, and responses submitted in less than 4 minutes were screened out as a quality control measure (n=1,177). Additional exclusions were made for incomplete surveys (n=62) or those that omitted key demographic data (n=450). Both survey waves were compared for patterns of missingness before they were combined into a final dataset of N=899 observations.

Ethnicities represented in the sample were coded to match the 2017 American Community Survey categories for Asian sub-populations: Chinese (n=204, 22.7%), Filipino (n=163, 18.1%), South Asian (n=139, 15.5%), Korean (n=72, 8.0%), Japanese (n=55, 6.1%), Other Southeast Asian (n=173, 19.2%), and Other Asian/Multi-ethnic (n=93, 10.3%). Half of the sample (50.8%; n=457) was born in the US; 22.0% (n=198) emigrated as children; and 26.5% (n=238) emigrated as adults (Table 1). Nine (1.0%) respondents used the simplified Chinese version of the survey. We used respondents’ Internet Protocol (IP) addresses to assess location of survey completion; respondents were located throughout the United States: Northeast (n=151, 16.8%), South (n=213, 23.7%), Midwest (n=124, 13.8%), and West (n=381, 39.3%). A minority of survey responses (n=30, 3.3%) were associated with non-US IP addresses, but triangulation with other survey items ensured the veracity of these responses and alignment with eligibility criteria for participation.

Table 1.

Sample Sociodemographic Information (N=899)

| 95% Confidence limits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Weighted N (%) | Lower | Upper | |

| Under 55 | 640 (71.2) | 596.0 (66.3) | 63.1 | 69.6 |

| Female | 499 (55.5) | 489.5 (54.5) | 51.2 | 57.8 |

| Post-HS Education | 698 (77.6) | 703.9 (78.3) | 75.6 | 81 |

| Annual Household Income ≤ $40K | 225 (25.0) | 227.8 (25.4) | 22.5 | 28.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Chinese | 204 (22.7) | 204.0 (22.7) | 19.9 | 25.5 |

| Filipino | 163 (18.1) | 163.0 (18.1) | 15.6 | 20.7 |

| South Asian | 139 (15.5) | 139.0 (15.5) | 13 | 17.9 |

| Japanese | 55 (6.1) | 55.0 (6.1) | 4.6 | 7.7 |

| Korean | 72 (8.0) | 72.0 (8.0) | 6.2 | 9.8 |

| Other Asian/Multi-Ethnic | 93 (10.3) | 92.8 (10.3) | 8.3 | 12.3 |

| Other Southeast Asian | 173 (19.2) | 172.8 (19.2) | 16.6 | 21.8 |

| Nativity/Immigration | ||||

| Born in US | 457 (50.8) | 446.2 (49.7) | 46.3 | 53 |

| Raised in US | 198 (22.0) | 200.2 (22.3) | 19.5 | 25.1 |

| Neither | 238 (26.5) | 246.5 (27.4) | 24.4 | 30.4 |

| Religion | ||||

| Buddhist | 140 (15.6) | 141.4 (15.7) | 13.3 | 18.2 |

| Catholic | 196 (21.8) | 198.2 (22.1) | 19.3 | 24.8 |

| Hindu | 85 (9.5) | 81.7 (9.1) | 7.2 | 11 |

| Muslim | 36 (4.0) | 38.7 (4.3) | 2.9 | 5.7 |

| Protestant | 145 (16.1) | 144.8 (16.1) | 13.7 | 18.5 |

| Other | 65 (7.2) | 63.3 (7.1) | 5.4 | 8.7 |

| None | 228 (25.4) | 226.5 (25.2) | 22.4 | 28.1 |

Just over half of the sample was female (55.5%). Three-quarters of the sample (77.6%) reported having some post-high school education. Most respondents (71.2%) were under the age of 55 years; the median age was 36 years. The majority of respondents were married or cohabitating (n=457, 50.8%), and 71.9% (n=646) reported annual household incomes above $40,000. With regard to occupation, 42.8% (n=385) reported full-time employment; 11.6% (n=104) part-time employment; and 12.7% (n=114) were unemployed at the time of the survey. Additional occupational categories included retirees (n=97, 10.8%), students (n=102, 11.4%), and individuals who did not work outside the home (n=90, 10.0%). The single largest religious affiliation was “None” (n=228, 25.4%), followed by Catholicism (n=196, 21.8%), Protestantism (n=145, 16.1%), Buddhism (n=140, 15.6%), Hinduism (n=85, 9.5%), “Other” (n=65, 7.2%), and Islam (n=36, 4.0%; Table 1).

3.2. Willingness to Donate One’s Own Organs and Tissues

Overall, 40.7% (95% CI [37.5, 43.9]) of respondents were registered organ donors, and 58.1% (95% CI [54.8, 61.4]) indicated a willingness to be organ donors upon death (Table 2; refer to this and subsequent tables for confidence intervals around population estimates). Conversely, 20.5% indicated that they would not be organ donors, and 21.4% preferred to defer to the decision to their family.

Table 2.

Willingness to Donate Solid Organs

| 95% Confidence limits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Weighted N (%) | Lower | Upper | ||

| Are you a registered organ donor? | |||||

| Yes | 365.7 (40.7) | 37.5 | 43.9 | ||

| If you were able, would you be willing to donate your organs when you die? | |||||

| Yes | 522.0 (58.1) | 54.8 | 61.4 | ||

| No | 184.0 (20.5) | 17.8 | 23.2 | ||

| Would defer to family | 192.6 (21.4) | 18.7 | 24.2 | ||

| Would you donate a family member’s organs after death? | |||||

| Yes | 264.8 (29.5) | 26.5 | 32.5 | ||

| Yes, if I knew they wanted to donate | 469.9 (52.3) | 49.0 | 55.6 | ||

| No | 164.0 (18.3) | 15.7 | 20.8 | ||

No statistically significant associations were found between ethnicity and the willingness to donate one’s organs, but willingness was associated with respondents’ age, education, income, nativity, and religion (Table 3). Persons under the age of 55 were more willing to be donors than respondents over the age of 55 (61.1% vs. 52.2%; χ2(4)=10.7825, P=0.0329). Those with at least some form of college education expressed a greater willingness to donate (61.5%) than those with less educational attainment (45.8%; χ2(2)=15.2407, P=0.0005) and were also less likely to indicate a preference to defer the decision to family members (19.7% vs. 27.6%). Respondents reporting annual household incomes above $40,000 were more willing to donate their organs (61.0%) than those with lower incomes (52.1%; χ2(4)=9.8103, P=0.0464) and less likely to prefer that their family make the decision (24.2% v. 20.0%). Compared to US-born participants, individuals neither born nor raised in the US were less willing to donate their own organs (50.4% vs. 62.1%) and reported a greater preference for family members to make the decision for them (27.7% v. 18.9%; χ2(6)=14.1737, P=0.0291).

Table 3.

If you were able, would you be willing to donate your organs when you die?

| Yes | No | Would Defer to Family | X2 (DF), P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na (%) | 95% CL | Na (%) | 95% CL | Na (%) | 95% CL | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| Under 55 | 364.1 (61.1) | 57.3 | 64.9 | 104.1 (17.5) | 14.5 | 20.4 | 127.8 (21.4) | 18.2 | 24.6 | X2(4)=10.7825, 0.0329 |

| 55 and over | 155.1 (52.2) | 46.0 | 58.5 | 78.0 (26.3) | 20.8 | 31.7 | 63.9 (21.5) | 16.3 | 26.7 | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 288.0 (58.8) | 54.5 | 63.2 | 94.6 (19.3) | 15.8 | 22.8 | 106.9 (21.8) | 18.2 | 25.5 | NS |

| Male | 234.0 (57.2) | 52.2 | 62.1 | 89.4 (21.9) | 17.7 | 26.0 | 85.7 (21.0) | 16.8 | 25.1 | |

| Education | ||||||||||

| HS or less | 88.4 (45.8) | 38.8 | 52.8 | 51.4 (26.6) | 20.4 | 32.9 | 53.1 (27.6) | 21.2 | 33.9 | X2(2)=15.2407, 0.0005 |

| Post-HS Education | 432.7 (61.5) | 57.8 | 65.1 | 132.6 (18.8) | 15.9 | 21.8 | 138.6 (19.7) | 16.7 | 22.7 | |

| Annual Household Income | ||||||||||

| ≤ $40K | 118.7 (52.1) | 45.5 | 58.7 | 54.0 (23.7) | 18.1 | 29.3 | 55.1 (24.2) | 18.4 | 30.0 | X2(4)=9.8103, 0.0464 |

| > $40K | 392.7 (61.0) | 57.2 | 64.8 | 122.2 (19.0) | 15.9 | 22.1 | 128.7 (20.0) | 16.9 | 23.1 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Chinese | 111.0 (54.4) | 47.5 | 61.3 | 42.4 (20.8) | 15.0 | 26.6 | 50.6 (24.8) | 18.8 | 30.8 | NS |

| Filipino | 89.8 (55.1) | 47.5 | 62.8 | 35.1 (21.6) | 15.2 | 27.9 | 38.0 (23.3) | 16.8 | 29.8 | |

| South Asian | 86.9 (62.5) | 54.0 | 71.1 | 25.1 (18.1) | 11.4 | 24.8 | 27.0 (19.4) | 12.1 | 26.7 | |

| Japanese | 41.0 (74.5) | 62.9 | 86.0 | 10.0 (18.2) | 8.0 | 28.4 | 4.0 (7.3) | 0.4 | 14.3 | |

| Korean | 42.7 (59.3) | 47.9 | 70.7 | 15.2 (21.2) | 11.7 | 30.7 | 14.1 (19.5) | 10.3 | 28.8 | |

| Other Asian / Multi-ethnic | 50.7 (54.7) | 44.5 | 64.8 | 18.3 (19.7) | 11.5 | 27.9 | 23.8 (25.7) | 16.9 | 34.5 | |

| Other SE Asian | 99.9 (57.8) | 50.4 | 65.3 | 37.8 (21.9) | 15.6 | 28.1 | 35.1 (20.3) | 14.2 | 26.4 | |

| Nativity/Immigration | ||||||||||

| Born in US | 276.9 (62.1) | 57.6 | 66.6 | 84.9 (19.0) | 15.4 | 22.7 | 84.3 (18.9) | 15.3 | 22.5 | X2(6)=14.1737, 0.0291 |

| Raised in US | 118.9 (59.4) | 52.5 | 66.3 | 42.2 (21.1) | 15.2 | 26.9 | 39.1 (19.5) | 13.9 | 25.1 | |

| Neither | 124.3 (50.4) | 43.9 | 56.9 | 53.9 (21.9) | 16.6 | 27.2 | 68.3 (27.7) | 21.8 | 33.6 | |

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Buddhist | 72.9 (51.6) | 43.2 | 59.9 | 33.0 (23.3) | 16.2 | 30.4 | 35.5 (25.1) | 17.9 | 32.4 | X2(12)=24.9687, 0.0186 |

| Catholic | 107.8 (54.4) | 47.3 | 61.5 | 46.2 (23.3) | 17.0 | 29.4 | 44.2 (22.3) | 16.4 | 28.2 | |

| Hindu | 60.1 (73.6) | 64.0 | 83.1 | 14.4 (17.7) | 9.3 | 26.0 | 7.2 (8.8) | 2.9 | 14.6 | |

| Muslim | 14.8 (38.3) | 22.0 | 54.5 | 10.0 (25.9) | 11.6 | 40.2 | 13.9 (35.9) | 18.8 | 52.9 | |

| Protestant | 91.6 (63.2) | 55.3 | 71.1 | 21.9 (15.1) | 9.1 | 21.1 | 31.4 (21.7) | 15.0 | 28.4 | |

| Other | 41.2 (65.1) | 53.5 | 76.8 | 9.5 (15.0) | 6.4 | 23.6 | 12.6 (19.9) | 10.1 | 29.6 | |

| None | 133.5 (58.9) | 52.5 | 65.4 | 47.0 (20.7) | 15.4 | 26.1 | 46.0 (20.3) | 15.0 | 25.6 | |

All frequency counts presented are weighted.

The inclination to consult a spiritual advisor before making a personal donation decision was associated with lower rates of donation willingness (52.9% vs. 60.6%; χ2(2)=7.5159, P=0.0235) and higher rates of decisional deferment to family members (27.6% vs. 19.2%). However, religious affiliation overall was varied in its association with donation willingness (χ2(12)=24.9687, P=0.0186). (See Table 3). Individuals who reported their religious affiliation as Hindu expressed the highest willingness (73.6%) to donate their own organs and expressed the lowest preference for family members to make the decision (8.8%). Muslim respondents were the least willing to donate their own organs (38.3%) and the most likely to defer the donation decision to family (35.9%). Of the entire sample, the largest proportion reported no religious affiliation (25.4%).

3.3. Family Involvement in the Donation Decision

Only 9.5% of respondents indicated that they alone would make the decision about organ donation either by registering as an organ donor or by informing their family of their donation wishes (Table 4). A larger proportion (90.2%) reported that at least one other family member would be involved in their decision. Respondents preferring family involvement were more willing to donate their own organs (59.5% v. 44.9%; χ 2(2)=47.2937, P<0.0001) and those of a family member (30.6% v. 19.5%; χ 2(2)=45.7628, P<0.0001) than those who would make the decision independently. Participants who viewed the donation decision as theirs alone to make were considerably more unwilling to donate their own organs (48.2% v. 17.6%) and a family member’s organs (45.3% v. 15.5%). Spouses (55.1%), parents (35.8%), and children (29.8%) were listed as the primary family members who would take part in deciding whether the respondent would be an organ donor upon her/his death.

Table 4.

Family Involvement in the Donation Decision (N=899)

| 95% CL | Willingness to Donate Self | Willingness to Donate Family | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted N (%) | Lower | Upper | X2 (DF), P | X2 (DF), P | |

| Who would make the decision? | |||||

| Self Only | 85.3 (9.5) | 7.5 | 11.5 | X2(2)=47.2937, <0.0001 | X2(2)=45.7628, <0.0001 |

| Family/Other | 810.2 (90.2) | 88.2 | 92.2 | ||

| NR/NA | 3.2 (0.4) | 0 | 0.8 | ||

| Which family members? | |||||

| Spouse | 495.5 (55.1) | 51.8 | 58.4 | X2(2)=8.4442, 0.0169 | NS |

| Parents | 322.1 (35.8) | 32.7 | 39 | NS | NS |

| Children | 267.3 (29.8) | 26.7 | 32.8 | NS | NS |

3.4. Willingness to Donate a Family Member’s Organs and Tissues

Most respondents (81.8%) expressed a willingness to donate a family member’s organs if given the decision, with 52.3% affirming that this was contingent upon knowing the deceased’s intentions and 29.5% answering that they would donate without prior knowledge of the person’s donation wishes (Table 2). In contrast, 18.3% would decline donation on behalf of a family member if approached.

Donation of a family member’s organs and tissue varied significantly by ethnicity (χ2(12)=11.006, P=0.0084; Table 5). Japanese American respondents were the most willing to unequivocally donate an eligible family member’s organs (49.0%), followed by South Asians (38.6%). In contrast, Filipino participants were the most willing to donate a deceased family member’s organs if donation wishes were known (59.5%), followed by Chinese respondents (57.5%). Korean respondents were the least willing (25.6%) to donate their family member’s organs.

Table 5.

If you are responsible for making a family member’s medical decisions, would you donate his/her organs after death if they were eligible?

| Yes | Yes, if I knew they wanted to donate | No | X2 (DF), P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N a (%) | 95% CL | N a (%) | 95% CL | N a (%) | 95% CL | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| Under 55 | 188.5 (31.6) | 28.0 | 35.2 | 306.1 (51.4) | 47.5 | 55.2 | 101.4 (17.0) | 14.1 | 19.9 | NS |

| 55 and over | 73.4 (24.7) | 19.4 | 30.1 | 161.0 (54.2) | 48.0 | 60.4 | 62.6 (21.1) | 16.0 | 26.2 | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 149.7 (30.6) | 26.5 | 34.7 | 253.0 (51.7) | 47.3 | 56.1 | 86.8 (17.7) | 14.4 | 21.1 | NS |

| Male | 115.1 (28.1) | 23.7 | 32.6 | 216.9 (53.0) | 48.0 | 58.0 | 77.2 (18.9) | 14.9 | 22.8 | |

| Education | ||||||||||

| HS or less | 44.3 (23.0) | 17.1 | 28.9 | 98.8 (51.2) | 44.2 | 58.3 | 49.7 (25.8) | 19.6 | 32.0 | X2(2)=11.006, 0.0039 |

| Post-HS Education | 219.5 (31.2) | 27.7 | 34.7 | 370.1 (52.6) | 48.8 | 56.3 | 114.2 (16.2) | 13.4 | 19.0 | |

| Annual Household Income | ||||||||||

| ≤ $40K | 56.8 (24.9) | 19.2 | 30.6 | 129.4 (56.8) | 50.3 | 63.4 | 41.5 (18.2) | 13.2 | 23.3 | NS |

| > $40K | 199.4 (31.0) | 27.4 | 34.6 | 329.6 (51.2) | 47.3 | 55.1 | 114.6 (17.8) | 14.8 | 20.8 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Chinese | 52.1 (25.6) | 19.5 | 31.6 | 117.4 (57.5) | 50.7 | 64.4 | 34.5 (16.9) | 11.6 | 22.2 | X2(12)=11.006, 0.0084 |

| Filipino | 34.9 (21.4) | 15.1 | 27.7 | 97.0 (59.5) | 52.0 | 67.1 | 31.0 (19.0) | 13.0 | 25.1 | |

| South Asian | 53.7 (38.6) | 30.3 | 47.0 | 61.9 (44.6) | 35.9 | 53.2 | 23.4 (16.8) | 10.1 | 23.5 | |

| Japanese | 26.9 (49.0) | 35.8 | 62.2 | 23.1 (41.9) | 28.9 | 55.0 | 5.0 (9.1) | 1.5 | 16.6 | |

| Korean | 20.7 (28.7) | 18.3 | 39.1 | 32.9 (45.7) | 34.1 | 57.2 | 18.5 (25.6) | 15.4 | 35.8 | |

| Other Asian/Multi-ethnic | 28.5 (30.6) | 21.2 | 40.1 | 46.6 (50.2) | 40.0 | 60.5 | 17.7 (19.1) | 11.1 | 27.1 | |

| Other SE Asian | 48.0 (27.8) | 21.0 | 34.5 | 90.9 (52.6) | 45.1 | 60.2 | 33.9 (19.6) | 13.7 | 25.5 | |

| Nativity/Immigration | ||||||||||

| Born in US | 152.0 (34.1) | 29.7 | 38.4 | 224.6 (50.3) | 45.7 | 55.0 | 69.6 (15.6) | 12.2 | 19.0 | X2(4)=12.2610, 0.0189 |

| Raised in US | 56.1 (28.0) | 21.7 | 34.3 | 103.8 (51.8) | 44.8 | 58.9 | 40.4 (20.2) | 14.4 | 25.9 | |

| Neither | 55.0 (22.3) | 16.9 | 27.7 | 138.6 (56.2) | 49.8 | 62.6 | 53.0 (21.5) | 16.2 | 26.8 | |

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Buddhist | 41.1 (29.1) | 21.5 | 36.7 | 73.1 (51.7) | 43.3 | 60.1 | 27.2 (19.2) | 12.6 | 25.8 | X2(12)=26.1375, 0.0136 |

| Catholic | 48.8 (24.6) | 18.6 | 30.7 | 111.7 (56.4) | 49.3 | 63.4 | 37.7 (19.0) | 13.4 | 24.6 | |

| Hindu | 41.3 (50.5) | 39.6 | 61.5 | 26.8 (32.9) | 22.7 | 43.0 | 13.6 (16.6) | 8.0 | 25.2 | |

| Muslim | 10.2 (26.4) | 12.3 | 40.4 | 18.8 (48.5) | 31.4 | 65.6 | 9.7 (25.1) | 10.4 | 39.9 | |

| Protestant | 42.9 (29.6) | 22.1 | 37.1 | 81.5 (56.3) | 48.1 | 64.4 | 20.5 (14.1) | 8.4 | 19.9 | |

| Other | 20.7 (32.6) | 21.1 | 44.2 | 29.0 (45.7) | 33.6 | 57.9 | 13.7 (21.6) | 11.5 | 31.7 | |

| None | 59.9 (26.4) | 20.7 | 32.2 | 127.0 (56.1) | 49.6 | 62.5 | 39.7 (17.5) | 12.6 | 22.5 | |

All frequency counts presented are weighted.

Nativity, higher education, and religion were all significantly associated with the willingness to donate a family member’s organs (Table 5). US-born respondents were more likely to agree to donate without knowing the deceased’s wishes compared to non-US born respondents (34.1% v. 22.3%), who expressed higher refusal rates (21.5% v. 15.6%) and a greater preference for following family wishes (56.2% v. 50.3%; χ2(4)=12.2610, P=0.0189). Compared to participants with less educational attainment, those with at least college-level schooling were associated with lower refusal rates (16.2% v. 25.8%) and a greater willingness to donate a family member’s organs regardless of knowing his/her wishes (31.2% v. 23.0; χ2(2)=11.1006, P=0.0039).

Differences in religious affiliation and the willingness to donate a family member’s organs were observed. Respondents who identified as Hindu represented the largest proportion of those willing to donate regardless of whether their family member’s wishes were known (50.5%). Of all groups, Catholic respondents would most likely donate only if they knew the deceased’s preferences (56.4%). Moreover, participants identifying as Muslim expressed the greatest reluctance to donate their family member’s organs (25.1%).

3.5. Donation-related Beliefs and Concerns

Respondents indicating a willingness to be organ donors themselves held more positive views about organ donation (Z-Score=0.22) than those who were unwilling to donate (Z-Score= −0.41) or those who preferred that their family make the decision (Z-Score= −0.22; Wald χ2(1) = 50.29, < 0.0001) (Table 6). Additionally, participants willing to donate their own organs expressed fewer concerns than unwilling respondents (Z-Score= −0.18 v. Z-Score=0.33; Wald χ2(1) = 31.44, < 0.0001). Positive beliefs about organ donation were also associated with a greater willingness to make the decision for a family member and fewer donation-related concerns (Table 7). Belief scores were highest among those answering that they would without condition make the donation decision for family (Z-Score=0.13), followed by respondents who would consent only if the deceased’s donation wishes were known (Z-Score=0.08; Wald χ2(1) = 14.12, p = 0.0002). The most frequently endorsed beliefs included: “Organ donation makes something positive come out of death.” (M=75.7; Range: 0-100), “If my doctor told me that I needed a transplant, I would want one.” (M=72.1), “Organ donation is charitable and virtuous.” (M=71.7), and “People who have organ transplants are able to live full, productive lives.” (M=71.6). (See Figure 1 for a full list of belief statements.)

Table 6.

Donor Willingness on Belief and Concern Scores

| “If you were able, would you be willing to donate your organs when you die?” | 95% CL | Wald X2 (DF), P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Score | Mean | Lower | Upper | ||

| Belief Score | |||||

| Yes | 0.22 | 1217.1 | 1194.8 | 1239.4 | Wald X2(1)=50.29, < 0.0001 |

| No | −0.41 | 1059.5 | 1028.7 | 1090.3 | |

| Would Defer to Family | −0.22 | 1107 | 1074.7 | 1139.2 | |

| Concern Score | |||||

| Yes | −0.18 | 380 | 362.1 | 397.9 | Wald X2(1)=31.44, < 0.0001 |

| No | 0.33 | 479.1 | 453 | 505.2 | |

| Would Defer to Family | 0.17 | 448 | 425.2 | 470.8 | |

Table 7.

Willingness to Donate Family’s Organs on Belief and Concern Scores

| “Would you donate afamily member’s organsafter death?” | 95% CL | Wald X2 (DF), P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Score | Mean | Lower | Upper | ||

| Belief Scores | |||||

| Yes | 0.12 | 1193.7 | 1160.6 | 1226.9 | Wald X2(1)=14.12, 0.0002 |

| Yes, if I knew they wanted todonate. | 0.08 | 1180.8 | 1159.4 | 1202.1 | |

| No | −0.43 | 1053.3 | 1017 | 1089.7 | |

| Concern Score | |||||

| Yes | 0.02 | 418.3 | 389.5 | 447.1 | Wald X2(1)=13.79, 0.0002 |

| Yes, if I knew they wanted todonate. | −0.11 | 393.7 | 378 | 409.4 | |

| No | 0.27 | 467.4 | 439.3 | 495.5 | |

Figure 1.

Belief Statements

A logistic regression modelling concerns about donation found less concern among respondents who premised donation on knowing their family member’s intent (Z-Score= −0.11) closely seconded by those choosing to donate without the condition of intent (Z-Score=0.02). The greatest level of concern was found among respondents who would not authorize donation of a deceased family member’s organs (Z-Score=0.27; Wald χ2(1) = 13.79, p = 0.0002). The most frequently endorsed concerns included: “There is a black market of organs in some Asian countries.” (M=69.8; Range: 0-100), “There is a black market for organs in the US.” (M=67.3), “Organ donation is a practice that is more common and accepted in America and Europe, but not as much in my family’s home country.” (M=52.6), and “My parents would not agree if I became an organ donor.” (M=42.6). (See Figure 2 for a full list of concern statements.)

Figure 2.

Concern Statements

4. DISCUSSION

This study is the first large scale inquiry of Asian Americans’ willingness to donate their own and their family members’ organs after death. Unsurprisingly, greater positive beliefs about and less concerns with organ donation led to greater willingness to donate [7,21–23,45,55–58]. Other results uncover noteworthy similarities and differences compared to other racial/ethnic groups that have been the focus of previous studies on health disparities in organ donation and transplantation. For instance, like other major racial/ethnic groups in the US, AAs register as posthumous organ donors at lower rates than White Americans [17,42,59], view organ donation as an altruistic and positive act [5,13,60], and report mistrust in the organ donation system [13,61,23]. AAs differed from other marginalized populations in the value placed on family hierarchy and collective decision-making, as described in more detail below. The findings presented here have significant implications not only for practitioners and researchers, but they also reveal critical methodological considerations for conducting survey research among Asian populations.

4.1. Demographic Determinants of Donation

Certain demographic factors appear to impact the willingness of AAs to authorize donation for oneself and one’s family members. Respondents who had some college-level education and were younger than 55 years of age were more likely to donate their own organs and their family member’s organs, which is consistent with trends across the general population [42]. Additionally, those who identified as Hindu were more likely to be willing to donate their own organs and their family member’s organs, which is particularly novel because prior literature has pointed to religious beliefs as prohibitive to organ donation among minority communities [61–63]. In contrast, respondents who identified as Muslim were the most reluctant to donate their own organs and their family member’s organs, but this finding must be approached with caution. Prior research did not find a relationship between religiosity among American Muslims and unwillingness towards organ donation,[64] and another study indicated an overall lack of religious knowledge with regards to organ donation among the Muslim American population rather than abiding by any official religious stance.[65] Therefore, more targeted studies using qualitative methods are warranted to explore the nuances of donation willingness of Hindus and reluctance among Muslim Asians in the US. Moreover, participants who were born or raised in the US were more willing to donate a family member’s organs. This finding corroborates past research showing that organ donation is not strongly received among immigrant populations where acculturation is not high [66,67].

4.2. Centrality of the Family

Although past research has underscored the centrality of the family in donation-related decisions in some minority communities in the US [23,26,67–69], the current study offers a wider view of how donation-related decisions are made among a representative cross section of AAs. Some work among Latinx populations has also pointed to the inclusion of family as important to discussions about organ donation [5]. However, the current study shows that AAs would not only consider the family as part of the donation decision, but they would also tend to concede to the family altogether. For instance, the findings indicate that more than one-fifth of the sample would defer the donation decision to their family, with Muslim respondents endorsing this option more than participants of any other religious affiliation. Furthermore, donation of a family member’s organs would be more acceptable if his/her wishes were known for almost all ethnicities represented in the sample. Thus, this study’s results point to past research indicating that knowing a decedent’s donor wishes is a positive predictor of authorizing donation [47,56,70], and the findings also confirm smaller scale studies that reveal how the family usually supersedes individual positions about medical treatment in specific AA communities [69,71–73].

Previous work in other health contexts has pointed to the role of family among Asians; yet this research is the first to demonstrate organ donation as primarily a collective and family decision with a large representative sample of AAs. Specifically, only 9.5% of the sample indicated that donation would be firmly their individual decision, while the overwhelming majority of participants reported that they would involve spouses, parents, and children in this decision. Additionally, AAs who would seek family input would be more willing donate their own organs and their family member’s organs. Considering AAs’ comparatively lower donation rates and substantial transplant needs, an examination of how traditional notions of individual autonomy may or may not be applicable to Asian Americans within the US organ donation context is warranted.

4.3. Implications for Practice

The explication of the family’s role has critical implications for the family donation discussion at the bedside. Unless the patient indicated her/his consent to donate posthumously via a signed organ donor card, a drivers’ license marked ‘donor’ or by enrolling in a state online registry, current practice among donation professionals from organ procurement organizations (OPOs) relies on obtaining surrogate authorization from the legal next-of-kin at the bedside. Results from our past qualitative research, [45] however, demonstrate that crucial decisions among AAs, such as those about personal or surrogate organ donation, are at times not based solely on individual preference. Rather, donation discussions with AA families may be more successful if particularly influential family members are active participants in the donation discussion and that their concerns are properly addressed. This requires culturally targeted training and resources for OPO staff who may lack successful experience or comfort in approaching AA families for authorization.

Similarly, educational and awareness campaigns targeting AA communities should also account for the family dynamics around the disposition towards medical decision-making. Given the results presented here, rhetoric of national campaigns, such as “Share your Life, Share your Decision” [74], premises donation as an individually autonomous decision and thus may be ill-fitting for an Asian American audience. Our prior work has found that feeling excluded from mainstream American society was a factor in Asian Americans’ lack of enthusiasm for organ donation [45]. Accordingly, campaigns that depict AAs and messaging that align with their cultural values may have impact and appeal. Therefore, these findings offer nuanced dimension for national advocacy organizations like Donate Life America and the National Kidney Foundation in crafting culturally tailored messaging for AA populations. For instance, treating AAs as a homogenous group is ill-advised. As this study demonstrates, developing targeted messaging for specific sub-groups of AA is needed given the variability in willingness to donate and organ donation beliefs and concerns we observed in this study.

4.4. Methodological Considerations

It has been argued that research should accurately and representatively capture the nuances of AA populations [50]; this was the impetus behind the sampling method utilized for this study. In fact, an innovative aspect of this research is that AAs were examined by ethnic group rather than simply a large collective. Furthermore, unlike the general population in the US wherein roughly 70% identifies as Christian [75], just under 38% of the current sample was Christian, and one-quarter of respondents had no religious affiliation. Not only does this composition distinguish the current sample from those of studies about donor willingness among the general population, but the results also reveal the remarkable religious diversity among AAs. In addition, although our sample skews towards younger AAs (i.e. median age is 36), intentional weighting of age within ethnic groups allowed for a relatively representative sample with regards to age, as the median age of Asian Americans was 37.9 in 2019 [76].

In comparing our findings with data reported in the 2019 NSODAP [42], notable differences are observed. First, respondents reported greater willingness to donate their own organs upon death in our study than in the NSODAP (58.1% v. 51.9%) but also considerably less willingness to donate a family member’s organs accounting for both conditions of knowing (52.3% v. 77.2%) and not knowing (29.5% v. 54.0%) the deceased’s wishes. Also, higher levels of educational attainment and younger age were similarly associated with donor willingness among the general population in both studies, but rates of willingness were also significantly lower in our sample. These discrepancies point to the burgeoning need for more culturally targeted data collection procedures and more nuanced representative sampling methods. Indeed, the scant available literature has underscored a tendency of research about AA health to conflate socioeconomic characteristics, immigration, and other relevant experiences [77–81]. Assuring greater nuance will be imperative as this heterogeneous segment of the US population grows and as the public health needs of AAs become more manifest.

The design and development of our national survey, as well as the quality of its findings, can be largely attributed to an active stakeholder body like this study’s Community Advisory Board (CAB). In particular, CAB members provided culturally grounded guidance about the formative research and data that informed the survey and domains of inquiry. They distilled cultural, religious, spiritual, and cosmological concepts that would have otherwise been unknown to the non-native researcher. Such input allowed us to achieve the “thick description,”[82] or the situationally and culturally embedded context, required to translate complex concepts into an acceptable survey instrument for an understudied population. As collaborators, CAB members worked subsequently with the research team to design a culturally targeted social media intervention, aimed at increasing awareness about organ donation among their peers and communities. Results of the intervention are forthcoming.

4.5. Limitations

Despite the unique contributions this study makes to the extant literature on AAs and organ donation, the study is limited. Since the sample was recruited from panelists organized and maintained by Qualtrics, sampling bias is possible. Specifically, panelists are trained to respond to online surveys, which precludes potential individuals without a modicum of familiarity and comfort with internet-based activities.

4.6. Conclusion

This report details the results of the largest study of organ donation willingness among AAs in the US. Using a nationally representative and weighted sample, the findings comprise a body of knowledge about AAs’ perspectives on donating their own organs and their family members’ organs upon death. Asian Americans in this research observe distinct approaches to the concept of organ donation, such as the wide-scale deference to the family in decision-making. Further research should investigate the applicability of traditional notions of autonomy in the context of organ donation among AAs. The study also implements community-engaged methodological approaches in the study design and data collection with underrepresented populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) under grant number R01 DK11488. We thank the study participants for contributing to this research. We are also grateful to our Community Advisory Board Members – Ernest Arcilla, Jay Hilario, Grace Wu Kong, Ferdinand Luyun, Ruth Luyun, Shirley Moy, Jen Ordillas, Denise Schlatter, Stephanie Sun, Hanh Tran, Le-Quyen Vu, and Cecilia Vo – for their leadership and guidance with all aspects of this study. We also thank the Indochinese American Council, the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation, and the Filipino Executive Council of Greater Philadelphia, for their partnership and support of the project.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Availability of Data and Material

Reasonable requests for data will be accommodated by contacting the corresponding author.

Code Availability

Reasonable requests for SAS code will be accommodated by contacting the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Temple University (06/27/2017, #24584).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1.United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey Demographic and Housing Estimates 2020. Accessed March 24, 2022. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=asian&tid=ACSDP5Y2020.DP05

- 2.Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Published online 2014:13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alolod GP, Gardiner H, Agu C, et al. A Culturally Targeted eLearning Module on Organ Donation (Promotoras de Donación): Design and Development. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(1):e15793. doi: 10.2196/15793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salim A, Ley EJ, Berry C, et al. Increasing Organ Donation in Hispanic Americans: The Role of Media and Other Community Outreach Efforts. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(1):71. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvaro EM, Jones SP, Robles ASM, Siegel JT. Predictors of organ donation behavior among Hispanic Americans. Prog Transplant Aliso Viejo Calif. 2005;15(2):149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siminoff LA. Increasing Organ Donation in the African-American Community: Altruism in the Face of an Untrustworthy System. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(7):607. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-7-199904060-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siminoff LA, Saunders Sturm CM. African-American reluctance to donate: beliefs and attitudes about organ donation and implications for policy. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2000;10(1):59–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siminoff LA, Lawrence RH, Arnold RM. Comparison of black and white families’ experiences and perceptions regarding organ donation requests: Crit Care Med. 2003;31(1):146–151. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siminoff LA, Alolod GP, Gardiner HM, Hasz RD, Mulvania PA, Wilson-Genderson M. A Comparison of the Content and Quality of Organ Donation Discussions with African American Families Who Authorize and Refuse Donation. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(2):485–493. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00806-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frates J, Bohrer G. Hispanic perceptions of organ donation. Prog Transplant. 2002;12(3):169–175. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salim A, Berry C, Ley EJ, et al. The Impact of Race on Organ Donation Rates in Southern California. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(5):596–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.06.390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegel JT, O’Brien EK, Alvaro EM, Poulsen JA. Barriers to Living Donation Among Low-Resource Hispanics. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(10):1360–1367. doi: 10.1177/1049732314546869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arriola KRJ, Perryman JP, Doldren M. Moving beyond attitudinal barriers: Understanding African Americans’ support for organ and tissue donation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(3):339–350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callender CO. Organ donation in blacks: a community approach. Transplant Proc. 1987;19(1 Pt 2):1551–1554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callender CO, Hall MB, Branch D. An Aassessment of theEffectiveness of the MOTTEP Model for Increasing Donation Rates and Preventing the Need for Transplantation - Adult Findings: Program years 1998 and 1999. Semin Nephrol. 2001;21(4):419–428. doi: 10.1053/snep.2001.23778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callender CO, Miles PV, Hall MB, Gordon S. Blacks and whites and kidney transplantation: A disparity! but why and why won’t it go away? Transplant Rev. 2002;16(3):163–176. doi: 10.1053/trre.2002.127298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callender CO, Miles PV. Minority Organ Donation: The Power of an Educated Community. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siminoff L, Marshall H, Dumenci L, Bowen G, Swaminathan A, Gordon N. Communicating effectively about donation: an educational intervention to increase consent to donation. Prog Transplant. 2009;19(1):35–43. doi: 10.7182/prtr.19.1.9q02364408755h18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DuBay DA, Ivankova N, Herby I, et al. African American Organ Donor Registration: A Mixed Methods Design Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. Prog Transplant. 2014;24(3):273–283. doi: 10.7182/pit2014936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arriola KRJ, Robinson DHZ, Perryman JP, Thompson N. Understanding the relationship between knowledge and African Americans’ donation decision-making. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(2):242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson DHZ, Arriola KRJ. Strategies To Facilitate Organ Donation among African Americans. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):177–179. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12561214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell E, Robinson DHZ, Thompson NJ, Perryman JP, Arriola KRJ. Distrust in the Healthcare System and Organ Donation Intentions Among African Americans. J Community Health. 2012;37(1):40–47. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9413-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breitkopf CR. Attitudes, beliefs and behaviors surrounding organ donation among Hispanic women. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(2):191–195. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328329255c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pham H, Spigner C. Knowledge and opinions about organ donation and transplantation among Vietnamese Americans in Seattle, Washington: a pilot study. Clin Transplant. 2004;18(6):707–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alden DL, Cheung AHS. Organ donation and culture: A comparison of Asian American and European American beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(2):293–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albright C, Wong L, Cruz M, Sagayadoro T. Choosing to be a designated organ donor on their first driver’s license: actions, opinions, intentions, and barriers of Asian American and Pacific Islander adolescents in Hawaii. Prog Transplant. 2010;20(4):392–400. doi: 10.7182/prtr.20.4.g071t3ku521632n2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park HS, Shin YS, Yun D. Differences between white Americans and Asian Americans for social responsibility, individual right and intentions regarding organ donation. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(5):707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park HS, Smith SW, Yun D. Ethnic differences in intention to enroll in a state organ donor registry and intention to talk with family about organ donation. Health Commun. 2009;24(7):647–659. doi: 10.1080/10410230903242259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park HS, Ryu JY, Oh YJ. Comparisons of Koreans, Korean Americans, and White Americans regarding deceased organ donation. J Health Psychol. Published online August 2018:135910531879371. doi: 10.1177/1359105318793710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). National Data - Transplants in the US by Recipient Ethnicity. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/#

- 31.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. OPTN Policies. Published online April 28, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/eavh5bf3/optn_policies.pdf

- 32.Martins PN, Mustian MN, MacLennan PA, et al. Impact of the new kidney allocation system A2/A2B → B policy on access to transplantation among minority candidates. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(8):1947–1953. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). National Data - Competing Risk Median Waiting Time to Deceased Donor Transplant for Registrations Listed: 2003 - 2014. Published 2020. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/

- 34.Mathur AK, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, Guidinger MK, Merion RM. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to liver transplantation: Race/Ethnicity and Liver Transplant Access. Liver Transpl. 2010;16(9):1033–1040. doi: 10.1002/lt.22108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohandas R, Casey MJ, Cook RL, Lamb KE, Wen X, Segal MS. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in the Allocation of Expanded Criteria Donor Kidneys. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(12):2158–2164. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01430213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathur AK, Schaubel DE, Zhang H, Guidinger MK, Merion RM. Disparities in Liver Transplantation: The Association Between Donor Quality and Recipient Race/Ethnicity and Sex. Transplantation. 2014;97(8):862–869. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000438634.44461.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman KL, Fedewa SA, Jacobson MH, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Association Between Hospitalization and Kidney Transplantation Among Waitlisted End-Stage Renal Disease Patients. Transplantation. 2016;100(12):2735–2745. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callender CO, Koizumi N, Miles PV, Melancon JK. Organ Donation in the United States: The Tale of the African-American Journey of Moving From the Bottom to the Top. Transplant Proc. 2016;48(7):2392–2395. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.02.094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). National Data - Deceased Donors Recovered in the U.S. by Donor Ethnicity. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/#

- 40.Stewart DE, Wilk AR, Toll AE, et al. Measuring and monitoring equity in access to deceased donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(8):1924–1935. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldberg DS, Halpern SD, Reese PP. Deceased organ donation consent rates among racial and ethnic minorities and older potential donors. Crit Care Med. Published online 2013. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318271198c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices, 2019: Report of Findings. :213. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenberg MJ, Hovland CI, McGuire WJ, Abelson RP and Brehm JW, ed, ed. Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Components of Attitudes. In: Attitude Organization and Change: An Analysis of Consistency among Attitude Components. Greenwood Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eagly AH, Chaiken S. The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Soc Cogn 2007;25(5):582. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siminoff LA, Bolt S, Gardiner HM, Alolod GP. Family First: Asian Americans’ Attitudes and Behaviors Toward Deceased Organ Donation. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(1):72–83. doi: 10.1007/s40615-019-00635-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siminoff LA, Traino HM, Genderson MW. Communicating Effectively About Organ Donation: A Randomized Trial of a Behavioral Communication Intervention to Improve Discussions About Donation. Transplant Direct. 2015;1(2):1–9. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siminoff LA, Burant CJ, Ibrahim SA. Racial Disparities in Preferences and Perceptions Regarding Organ Donation. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;0(0):060721075157037-??? doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00516.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson TP, van de Vijver FJR. Social desirability in cross-cultural research. In: Harkness JA, van de Vijver FJR, Mohler PPh, eds. Cross-Cultural Survey Methods. Wiley; 2003:195–204. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park KB, Upshaw HS, Koh SD. East Asians’ Responses to Western Health Items. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 1988;19(1):51–64. doi: 10.1177/0022002188019001004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Islam NS, Khan S, Kwon S, Jang D, Ro M, Trinh-Shevrin C. Methodological issues in the collection, analysis, and reporting of granular data in Asian American populations: historical challenges and potential solutions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1354–1381. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore M, Chaudhary R. Patients’ attitudes towards privacy in a Nepalese public hospital: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6(1):31. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones EL. The Courtesy Bias in South-East Asian Surveys. In: Bulmer M, Warwick DP, eds. Social Research in Developing Countries. Routledge; 1983:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen C, Lee SY, Stevenson HW. Response Style and Cross-Cultural Comparisons of Rating Scales among East Asian and North American Students. Psychol Sci. 1995;6(3):170–175. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lavallée P, Beaumont JF. Why We Should Put Some Weight on Weights. Published online 2015. doi: 10.13094/SMIF-2015-00001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wakefield CE, Watts KJ, Homewood J, Meiser B, Siminoff LA. Attitudes toward organ donation and donor behavior: a review of the international literature. Prog Transpl. 2010;20(4):380–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siminoff LA, Burant C, Youngner SJ. Death and organ procurement: public beliefs and attitudes. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(11):2325–2334. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siminoff L, Mercer MB, Graham G, Burant C. The reasons families donate organs for transplantation: Implications for policy and practice. J Trauma - Inj Infect Crit Care. 2007;62(4):969–978. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000205220.24003.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Howard RJ. Organ donation decision: comparison of donor and nondonor families. Am J Transpl. 2006;6(1):190–198. doi:AJT1130 [pii] 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01130.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kernodle AB, Zhang W, Motter JD, et al. Examination of Racial and Ethnic Differences in Deceased Organ Donation Ratio Over Time in the US. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(4):e207083. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.7083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flemming SSC, Redmond N, Williamson DH, et al. Understanding the pros and cons of organ donation decision-making: Decisional balance and expressing donation intentions among African Americans. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(10-11):1612–1623. doi: 10.1177/1359105318766212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jacob Arriola KR, Perryman JP, Doldren MA, Warren CM, Robinson DHZ. Understanding the Role of Clergy in African American Organ and Tissue Donation Decision-Making. Ethn Health. 2007;12(5):465–482. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robinson DHZ, Klammer SMG, Perryman JP, Thompson NJ, Arriola KRJ. Understanding African American’s Religious Beliefs and Organ Donation Intentions. J Relig Health. 2014;53(6):1857–1872. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9841-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li MT, Hillyer GC, Husain SA, Mohan S. Cultural barriers to organ donation among Chinese and Korean individuals in the United States: a systematic review. Transpl Int. 2019;32(10):1001–1018. doi: 10.1111/tri.13439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Padela AI, Zaganjor H. Relationships Between Islamic Religiosity and Attitude Toward Deceased Organ Donation Among American Muslims. Transplantation. 2014;97(12):1292–1299. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000441874.43007.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hafzalah M, Azzam R, Testa G, Hoehn KS. Improving the potential for organ donation in an inner city Muslim American community: the impact of a religious educational intervention. Clin Transplant. 2014;28(2):192–197. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ríos A, López-Navas AI, García JA, et al. The attitude of Latin American immigrants in Florida (USA) towards deceased organ donation – a cross section cohort study. Transpl Int. 2017;30(10):1020–1031. doi: 10.1111/tri.12997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trompeta JA, Cooper BA, Ascher NL, Kools SM, Kennedy CM, Chen JL. Asian American Adolescents’ Willingness to Donate Organs and Engage in Family Discussion about Organ Donation and Transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2012;22(1):33–70. doi: 10.7182/pit2012328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Jones SP. Organ Donor Registration Preferences Among Hispanic Populations: Which Modes of Registration Have the Greatest Promise? Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(2):242–252. doi: 10.1177/1090198104272251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu J, Wallace DC, McCoy TP, Amirehsani KA. A Family-Based Diabetes Intervention for Hispanic Adults and Their Family Members. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40(1):48–59. doi: 10.1177/0145721713512682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Siminoff LA, Lawrence RH. Knowing patients’ preferences about organ donation: does it make a difference? J Trauma. 2002;53(4):754–760. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200210000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bowman KW, Singer PA. Chinese seniors’ perspectives on end-of-life decisions. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(4):455–464. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00348-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blackhall LJ. Ethnicity and Attitudes Toward Patient Autonomy. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1995;274(10):820. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530100060035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McLaughlin LA, Braun KL. Asian and Pacific Islander Cultural Values: Considerations for Health Care Decision Making. Health Soc Work. 1998;23(2):116–126. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.2.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Molinari A Share Your Life. Share Your Decision: How the Campaign to Increase Organ Donations Provides a Model for Public Health Awareness Efforts. Coalition for Clinical Trials Awareness; 2015. www.CCTAwareness.org [Google Scholar]

- 75.Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI). The 2020 Census of American Religion. Published July 2021. Accessed September 29, 2021. https://www.prri.org/research/2020-census-of-american-religion/

- 76.US Census Bureau. Published 2019. Accessed November 8, 2021. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?tid=ACSSPP1Y2019.S0201

- 77.Ghosh C Healthy People 2010 and Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders: Defining a Baseline of Information. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(12):2093–2098. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.12.2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen MS, Hawks BL. A Debunking of the Myth of Healthy Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9(4):261–268. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.4.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Contreras CA. Addressing Cardiovascular Health in Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: A Background Report. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health. 1999;7(2):95–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (with CD). National Academies Press; 2003:12875. doi: 10.17226/12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trinh-Shevrin C, Islam NS, Rey MJ. Asian American Communities and Health: Context, Research, Policy, and Action. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Geertz C The Interpretation of Cultures. Vol 5019. Basic books; 1973. [Google Scholar]