Abstract

Introduction:

Numerous studies have indicated that intra-articular steroid injections to the hip are beneficial for their ability to offer short-term pain relief. However, recent studies have drawn concerns that the injections may cause rapidly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip (RPOH) following intra-articular steroid injections. The prevalence of RPOH following intra-articular steroid injections varies widely in the literature.

Objective:

To identify the prevalence of RPOH following intra-articular steroid injections, and to compare baseline characteristics between patients with and without RPOH.

Design:

Case series.

Setting:

Tertiary academic hospital

Patients:

924 patients (median[IQR] age: 59[45–70] years; 579 females) who received an intra-articular hip steroid/anesthetic injection from January 2016 to March 2018 and had available pre- and post-injection imaging (prior to surgical intervention) were included in the study.

Interventions:

Baseline and injection-related data, including demographics, age, body mass index, medical history, laterality, and steroid type, were collected from electronic medical records.

Main Outcome Measures:

Post-injection RPOH was determined via imaging review by a physiatry fellow, followed by an attending physiatrist and a musculoskeletal radiologist to confirm findings.

Results:

The majority of patients received unilateral injections into the hip, and the most common steroids used were triamcinolone and methylprednisolone. Review of pre- and post-injection imaging revealed 26 cases of RPOH, for an overall prevalence of 2.8% (95% CI: 1.9%–4.1%). Compared to those without RPOH, patients with RPOH were significantly older (median[IQR]: 64[60–73] vs. 59[44–70] years, p=0.003) and had a shorter duration of symptoms prior to their injections (median[IQR]: 3[1–6] vs. 12[6–36] months, p<0.001). Adjusted regression analyses showed that age was associated with greater odds of RPOH (OR[95% CI]: 1.04[1.01, 1.07]; p=0.003).

Conclusions:

The prevalence of RPOH following intra-articular steroid injections into the hip was lower than previously reported but still clinically relevant. This should be considered when counseling patients prior to intra-articular hip steroid injections.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Intra-articular steroid injection, Hip

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common joint disorder, with an estimated 250 million cases worldwide1. The World Health Organization approximates that 10% of men and 18% of women older than 60 have symptomatic OA, 80% of whom have some level of functional disability2,3. Clinically, the knee joint is the most common site of OA and accounts for an estimated 85% of OA cases worldwide, followed by the hand and hip1. Nonsurgical treatment of OA includes, but is not limited to, patient education, exercise, physical therapy, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, and intra-articular steroid injections.

As the hip joint is one of the principal weight-bearing joints in the body, the effects of OA can greatly impact quality of life. Risk factors that are associated with hip OA include age, sex, obesity, and genetics. In addition to a progressive loss of articular cartilage, hip OA involves the subchondral bone, ligaments, capsule, synovium, and periarticular muscles1,2. Despite the burden that hip OA has placed on society, research on its etiopathogenesis and treatment lags behind the more common knee OA4. Its complex pathogenesis involves various metabolic, inflammatory, and mechanical factors, which cause the eventual demise of the synovial joint5.

Intra-articular steroid injections to the hip are often performed for patients who have failed other conservative management and/or wish to avoid or delay surgery. These injections may also be performed for diagnostic purposes. Although numerous studies have indicated that these injections are beneficial if only for their ability to offer short-term pain relief, recent studies have drawn concerns that they may cause rapidly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip (RPOH) following intra-articular steroid injections6,7,8,9,10,11.

RPOH significantly impairs joint function for the patient and was first reported in 1970 by Postel and Kerball12. It is considered rare but can lead to total destruction of the joint in as little as 6 months and up to 12 months; clinically, we see cases progress more rapidly. While similar to primary OA, RPOH can be differentiated by the rapid rate and severity of the destruction of the joint, as well as by radiological imaging13. Recent publications have determined the prevalence of RPOH to range from 7% to 44% following intra-articular steroid hip injections8,9,14.

The primary objective of this study was to identify the prevalence of RPOH in patients after receiving intra-articular steroid injections at an orthopedic institution. The secondary objective was to evaluate whether there were differences in baseline factors between patients with and without RPOH.

Methods

Ethics

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. A waiver of consent was obtained, as there was no patient contact, and all data were collected from existing electronic medical records. Imaging review and assessment of RPOH were performed retrospectively. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Patient Screening and Baseline Data

All patients who received an intra-articular injection of a steroid and local anesthetic into the hip between January 1, 2016 and March 1, 2018 by any provider at the hospital and had available pre-injection and post-injection imaging were included in the study. Injections were performed across multiple departments in offices, interventional radiology clinics, or ambulatory surgical centers. Multiple providers performed these injections; clinical trainees may have been involved in the performance of the injections, but only in the presence of an attending physician. Exclusion criteria included incomplete injection data, hip surgery prior to any post-injection imaging, and suspected or confirmed RPOH prior to the intra-articular injection.

Baseline data were collected from electronic medical records and included demographics, radiological data, pain scores, and duration of pain. Pre-injection imaging included radiographs (anteroposterior; n=779), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; n=213), and computed tomography (CT) scans (n=64). Injection data included the type of steroid used and dose given, the type of anesthetic used and dose given, the laterality of the injection, and the injection guidance technique. Post-injection imaging was evaluated for RPOH and included radiographs (anteroposterior; n=702), MRI (n=139), and CT scans (n=158). Some patients had more than one imaging modality at pre-injection or post-injection time points. In 71% of patients, the same imaging modality was used at pre-injection and post-injection time points.

Identification of RPOH

RPOH was identified using a modified classification system that was adapted from the Zazgyva RPOH classification system and was defined as having progressive OA within a 12-month period3,12,15. Grade 1 was defined by a slight narrowing of joint space without any deformation of the femoral head; Grade 2 was defined by the complete disappearance of joint space, a deformed femoral head and acetabulum (loss of sphericity of the femoral head), appearance of cysts in the femoral head or acetabulum, and ascension of the femoral head ≤0.5 cm above the radiological teardrop; Grade 3 was defined by the complete disappearance of joint space, presence of large cysts, partial osteolysis of the femoral head, and ascension of the femoral head >0.5 cm above the radiological teardrop. The same modality of pre- and post-injection imaging was used when possible. In cases where pre- and post-injection imaging differed, CT and/or MRI were examined for abnormalities that would confirm RPOH; these included femoral head collapse, subchondral fracture, and full-thickness cartilage loss.

The initial imaging review was performed by a physiatry fellow. A secondary review was completed by an attending physiatrist. A final review and confirmation of RPOH cases was performed by an attending musculoskeletal radiologist who had 22 years of experience in the field and was blinded to the patients’ medical history. The reviewers were blinded to each other’s findings. Any discrepancies were brought to the attention of the principal investigator and presented to the musculoskeletal radiologist.

Statistical Analysis

All patients who met the eligibility criteria were included in the study. Continuous variables are summarized as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), and categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages. Univariate analysis of baseline categorical variables between patients with and without RPOH was performed with the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate. Comparisons of continuous variables between patients with and without RPOH were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Logistic regression was used to compare the association of age with RPOH. In the adjusted model, sex was included as a confounder. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) are reported. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient Flow

A total of 1,439 patients who underwent intra-articular hip steroid and anesthetic injections with available pre- and post-injection imaging during the aforementioned time period were identified. Post-injection imaging was obtained following a surgical procedure in 515 patients; therefore, these patients were excluded. The remaining 924 patients were included in the study.

Baseline Information

The median (IQR) age and body mass index for all patients were 59 (45, 70) years and 26.2 (23.1, 30.2) kg/m2, respectively. Sixty-four percent of the patients were female (n=579). The duration of hip pain varied widely, with a median of 12 (5, 36) months. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Information and Demographics

| Study Cohort (N=924) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59 (45, 70) |

| Female sex; n (%) | 579 (64.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.2 (23.1, 30.2) |

| Duration of symptoms; months† | 12 (5, 36) |

| Previous oral steroid use; n (%) | 45 (5.1) |

| Fracture on pre-injection imaging; n (%) | 17 (1.8) |

| History of autoimmune disease; n (%) | 149 (16.1) |

| History of allergies; n (%) | 473 (51.2) |

| Additional injections; n (%) | 202 (21.9) |

| Laterality | |

| Bilateral | 43 (4.7) |

| Left | 413 (44.7) |

| Right | 468 (50.6) |

| Guidance | |

| Fluoroscopic | 334 (36.1) |

| Ultrasound | 590 (63.9) |

| Type of steroid in injectate‡ | |

| Triamcinolone | 479 (51.8) |

| Methylprednisolone | 377 (40.8) |

| Betamethasone | 64 (6.9) |

| Dexamethasone | 4 (0.4) |

Results are median (interquartile range), unless otherwise specified.

Duration of symptoms was available for 449 patients.

Steroid doses ranges from 3–12 mg for betamethasone, 40–120 mg for methylprednisolone, and 20–40 mg for triamcinolone. For dexamethasone, all 4 patients received 4 mg.

Injection

The majority of patients (n=881, 95.3%) received unilateral injections. Ultrasound guidance (n=590, 63.9%) was more commonly used, and the most common steroid in the injectate was triamcinolone (n=479, 51.8%), followed by methylprednisolone (n=377, 40.8%). Additional intra-articular hip injections were given to 202 patients (21.9%) (Table 1).

RPOH

Review of pre- and post-injection imaging revealed 26 cases of RPOH, for an overall prevalence of 2.8% (95% CI: 1.9%, 4.1%). Of these 26 cases, 13 (50%) were within 3 months of injection, 7 (27%) were within 3–6 months of injection, 4 (15%) were within 6–9 months of injection, and 2 (8%) were within 9–12 months of injection. Eleven cases (42%) were classified as Grade 2, and 15 cases (58%) were classified as Grade 3. Representative cases showing RPOH within 6 weeks and 6 months post-injection are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. All but 3 cases of RPOH required total hip arthroplasty or resurfacing (n=23; 88%).

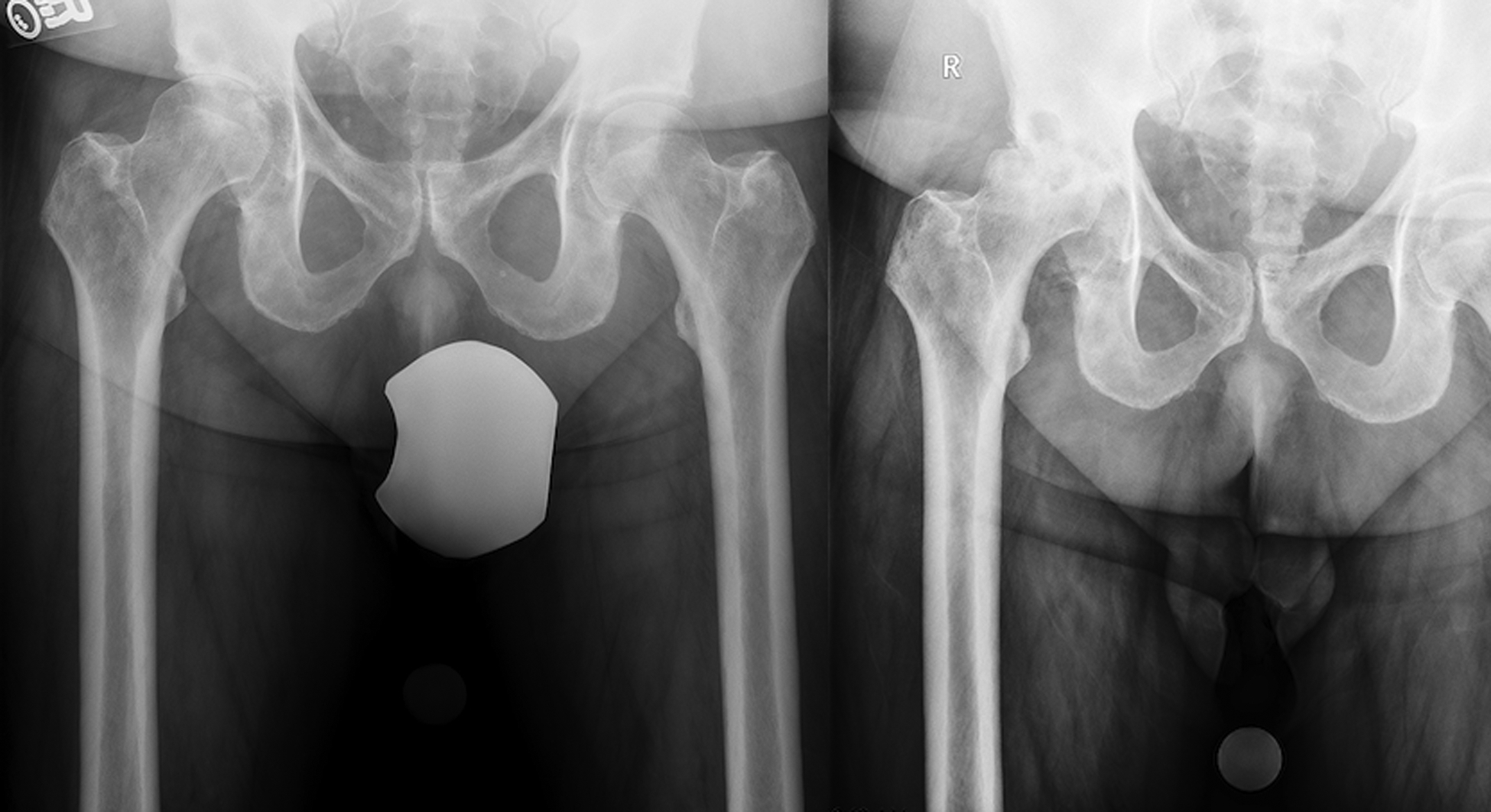

Figure 1.

Representative case showing rapidly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip within 6 weeks post-injection. Initial imaging (A) showed Grade 2 osteoarthritis. Follow-up imaging at 6 weeks post-injection (B) showed disintegration of the femoral head, classified as Grade 3, indicating rapidly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip.

Figure 2.

Representative case showing rapidly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip within 6 months. Initial imaging (A) showed Grade 2 osteoarthritis. Subsequent imaging at 6 months post-injection (B) showed flattening of the femoral head, which was classified as Grade 3, indicating rapidly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip.

A sub-analysis was performed to compare baseline and injection data between patients with and without RPOH. Age and duration of symptoms were the only statistically significant differences between groups. RPOH patients were older and reported a much shorter duration of symptoms than patients without RPOH (p=0.003 and <0.001, respectively) (Table 2). Results from logistic regression show that age was associated with greater odds of RPOH (OR[95% CI]: 1.04[1.01,1.07], p=0.003). Duration of symptoms was not included in the regression model, due to the low number of patients with available data.

Table 2.

Comparison of Baseline and Injection Data between RPOH and Non-RPOH Patients

| RPOH | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=26) | No (n=898) | ||

| Age; years | 64 (60–73) | 59 (44–70) | 0.003 |

| Body mass index; kg/m2 | 28 (24–32) | 26 (23–30) | 0.277 |

| Duration of symptoms; months† | 3 (1–6) | 12 (6–36) | <0.001 |

| Female sex; n (%) | 13 (50) | 566 (63) | 0.176 |

| Previous oral steroid use; n (%) | 1 (4) | 44 (5) | 0.795 |

| Fracture on pre-injection imaging; n (%) | 0 (0) | 17 (2) | 0.479 |

| History of autoimmune disease; n (%) | 5 (19) | 144 (16) | 0.405 |

| History of allergies; n (%) | 12 (46) | 461 (51) | 0.602 |

| Low bone density; n (%) | 5 (19) | 117 (13) | 0.357 |

| Additional injections; n (%) | 5 (19) | 197 (22) | 0.742 |

| Triamcinolone in injectate; n (%) | 15 (58) | 464 (52) | 0.545 |

| Methylprednisolone in injectate; n (%) | 10 (38) | 367 (41) | 0.806 |

| Betamethasone in injectate; n (%) | 1 (4) | 63 (7) | 0.530 |

| Dexamethasone in injectate; n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.4) | 0.733 |

| Ultrasound guidance; n (%) | 17 (65) | 573 (64) | 0.869 |

Results are median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and count (percentage) for discrete variables.

RPOH: rapidly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip

Duration of symptoms was available for 11 patients with RPOH and 438 patients without RPOH.

Discussion

The incidence and etiology of RPOH is not widely studied. The literature has shown varying rates of RPOH in patients who receive intra-articular steroid injections. Simeone et al. reported that 44% (31/70) of hips had progression of OA after an injection, and 17% (12/70) had complete collapse of the hip9. Hess et al. reported that 21% of the patient population suffered from RPOH after an injection to the afflicted hip8. Most recent, Boutin et al. reported that 7.2% of patients had RPOH following intra-articular steroid injections14. Our results indicated a lower rate (2.8%) that is still clinically relevant and is more in line with the expected incidence of RPOH. The etiology of RPOH is not yet known, but it is believed that the pathological mechanisms involved include drug toxicity, cytokine-mediated immunological mechanisms, autoimmune reactions, or subchondral insufficiency fractures13. Furthermore, patients with RPOH were significantly older and had a shorter duration of symptoms, compared to those without RPOH. Age was significantly associated with greater odds of RPOH.

While we found a lower prevalence of RPOH, the relationship between intra-articular injections and RPOH is still unknown. It is very possible that the drug toxicity from the injectate may be playing a role in the destruction of the hip joint. The use of particulate steroids (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide, methylprednisolone, betamethasone) versus non-particulate steroids (e.g., dexamethasone) may play a role, as the studies by Simeone, Hess, and Boutin all reported RPOH following intra-articular injections of particulate steroids8,9,14. Similarly, all 26 patients with RPOH in our study received intra-articular injections of a particulate steroid. However, it is important to note that only 4 patients in the overall cohort received injections containing a non-particulate steroid. In addition, the type of image guidance used may be a factor. Previous studies have focused solely on RPOH following intra-articular steroid injections performed under fluoroscopic guidance8,9,14. In our study, the majority of patients (63.9%) received intra-articular steroid injections under ultrasound guidance. However, there were no differences in the breakdown of ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance between patients with and without RPOH.

Another possibility is that the observed RPOH was a culmination of natural progression of degenerative joint disease. By receiving an injection, the patients may experience pain relief and overload the hip joint, leading to a more rapid progression of OA. We also could have just observed the natural history of OA progression for those individuals. Nonetheless, RPOH was clear in several patients and occurred at a minimum of 6 weeks post-injection. It is important to note that we cannot definitively state that intra-articular steroid injections were the cause of RPOH in these patients.

Limitations

Our findings should be considered with the following limitations. First, the retrospective design of the study did not allow for the systematic collection of clinical information. For example, duration of symptoms was not captured for all patients; thus, it could not be included in the logistic regression model. Second, there is no well-established grading system for RPOH. The established system by Lequesne tracked joint narrowing over a 12-month period15. We also elected to use a hybrid of grading systems based on the Tonnis system and the Zazgyva system to include deformities that could be used in the evaluation of MRI/CT when radiographs were not available for assessments13,15. Third, not all patients had the same pre- and post-injection imaging modalities. However, we opted to include different imaging modalities in order to capture as many patients as possible. Fourth, only patients with both pre- and post-injection imaging were included in the study. There may be more patients who were missed due to the lack of post-injection imaging and did not have RPOH, which would lead to an even lower prevalence of RPOH. Fifth, the exclusion of hip surgery prior to any post-injection imaging may also affect the prevalence of RPOH. Lastly, post-injection imaging that was taken over 1 year after the injection was included in the study.

Conclusions

Our study shows a much lower rate of RPOH after an intra-articular steroid injection than previously reported. The reason for the association is still unknown and requires further study. This is still clinically relevant and should be factored into counseling our patients with hip OA before intra-articular injections. The safety of these injections should be assessed via multi-centered studies at institutions with similar patient size population to determine the true incidence of RPOH following these injections.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Zafir Abutalib for his assistance with the statistical analyses.

Funding:

REDCap use was supported by grant number UL1TR002384 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019; 393(10182):1745–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittenauer R, Smith L, Aden K. Update on 2004 Background Paper: Osteoarthritis. 2013. Available at: https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/priority_medicines/BP6_12Osteo.pdf. Accessed Aug 1, 2021.

- 3.Kovalenko B, Bremjit P, Fernando N. Classifications in Brief: Tönnis Classification of Hip Osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018; 476(8):1680–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alle Deveza L, Eyles JP. Management of hip osteoarthritis. 2021. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-of-hip-osteoarthritis. Accessed November 10, 2021.

- 5.Lespasio MJ, Sultan AA, Piuzzi NS, et al. Hip Osteoarthritis: A Primer. Perm J 2018; 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruse DW. Intraarticular cortisone injection for osteoarthritis of the hip. Is it effective? Is it safe? Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2008; 1(3–4):227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto T, Schneider R, Iwamoto Y, Bullough PG. Rapid destruction of the femoral head after a single intraarticular injection of corticosteroid into the hip joint. J Rheumatol 2006; 33(8):1701–1704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess SR, O’Connell RS, Bednarz CP, Waligora ACt, Golladay GJ, Jiranek WA. Association of rapidly destructive osteoarthritis of the hip with intra-articular steroid injections. Arthroplast Today 2018; 4(2):205–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simeone FJ, Vicentini JRT, Bredella MA, Chang CY. Are patients more likely to have hip osteoarthritis progression and femoral head collapse after hip steroid/anesthetic injections? A retrospective observational study. Skeletal Radiol 2019; 48(9):1417–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Omari AA, Aleshawi AJ, Marei OA, et al. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head after single steroid intra-articular injection. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2020; 30(2):193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kompel AJ, Roemer FW, Murakami AM, Diaz LE, Crema MD, Guermazi A. Intra-articular Corticosteroid Injections in the Hip and Knee: Perhaps Not as Safe as We Thought? Radiology 2019; 293(3):656–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Postel M, Kerboull M. Total prosthetic replacement in rapidly destructive arthrosis of the hip joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1970; 72:138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zazgyva A, Gurzu S, Gergely I, Jung I, Roman CO, Pop TS. Clinico-radiological diagnosis and grading of rapidly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96(12):e6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boutin RD, Pai J, Meehan JP, Newman JS, Yao L. Rapidly progressive idiopathic arthritis of the hip: incidence and risk factors in a controlled cohort study of 1471 patients after intra-articular corticosteroid injection. Skeletal Radiol 2021; 50(12):2449–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lequesne M, Samson M. A functional index for hip diseases. Reproducibility. Value for discriminating drug’s efficacy. Paper presented at: 15th International Congress of Rheumatology1981; Paris. [Google Scholar]