1. Introduction

The disproportionate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on racially and ethnically minoritized individuals[40] has led to a renewed sense of urgency in addressing persistent and widespread disparities in healthcare. Within pain medicine, robust evidence indicates that Black patients report higher levels of acute and chronic pain than White patients[13,14,43]. Similarly, results from over 40 experimental studies[43] have consistently demonstrated moderate to large effects of participant race on experimental pain sensitivity across multiple modalities. Despite clinical and experimental evidence for racial and ethnic differences in pain, Black and Hispanic/Latino/a/x1 patients frequently receive less adequate pain care[12,64,80]. For example, a recent meta-analysis of analgesia prescription rates in emergency departments found that Black and Hispanic/Latino/a/x patients were 34% and 13% less likely, respectively, to receive opioid analgesics for acute pain compared to White patients[44].

The factors contributing to racial and ethnic disparities in pain—and disparities in health more broadly—ultimately stem from the historical and ongoing unequal treatment of racially and ethnically minoritized individuals. Systemic racism creates and perpetuates socioeconomic disadvantage among minoritized individuals[42,88], reduces healthcare access and trust in providers[28], and increases exposure to physical, psychological, and social factors that predict worse health outcomes including pain[33,40,69,75]. System-level changes, including parity in the racial and ethnic diversity of healthcare providers, legal reforms to protect minoritized individuals against systemic racism, and social reforms to increase equity of access to healthcare, are essential to mitigate racial and ethnic disparities in pain and pain management. At the same time, it is important to also seek out more immediate solutions that may be useful for minoritized patients experiencing the effects of systemic racism. In fact, a growing body of evidence points to a proximal contributor to pain disparities that may be addressed in the moment of the clinical encounter: intergroup anxiety – experienced by both providers and patients – associated with racial and ethnic discordance.

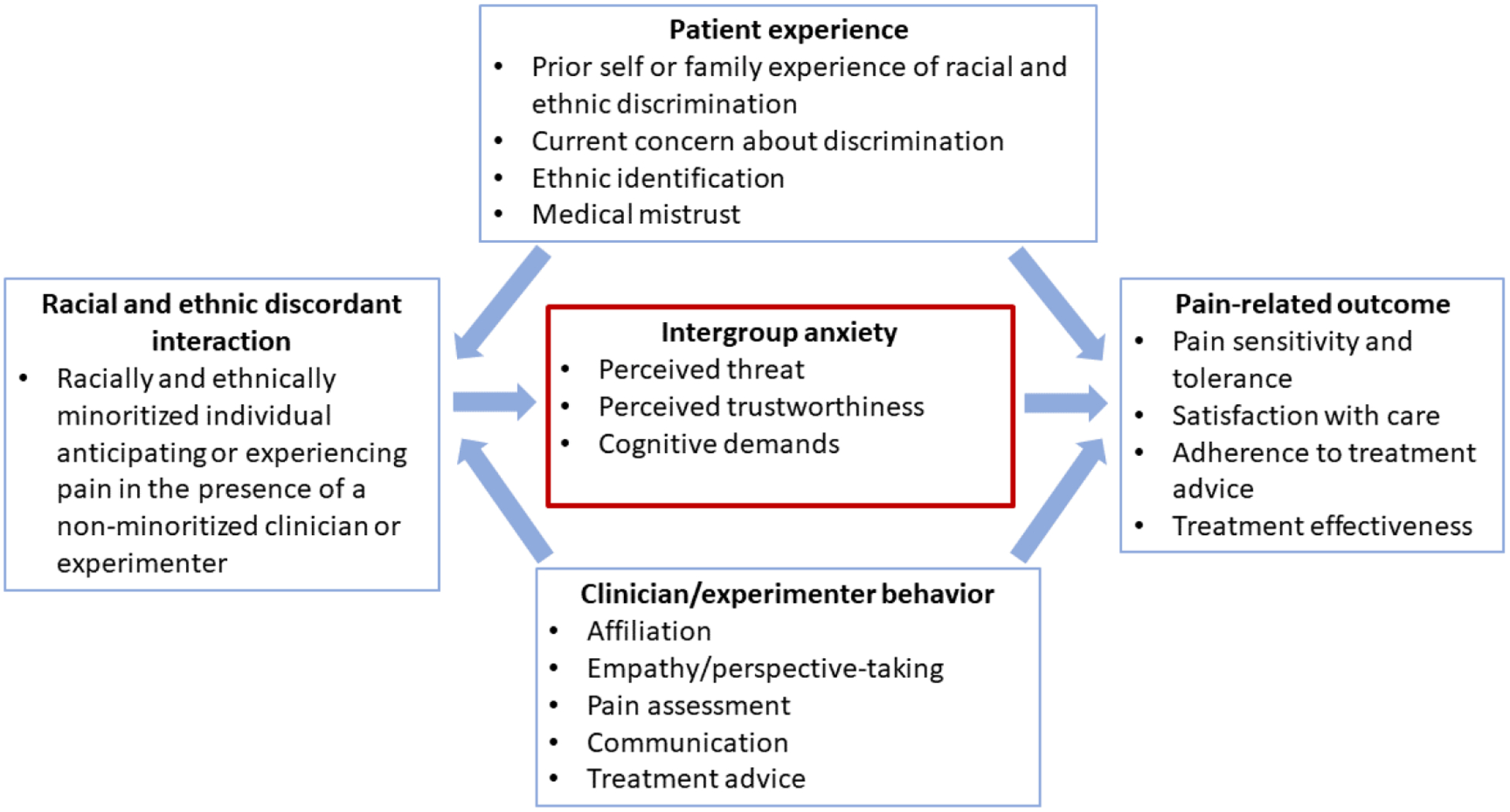

In this review, we outline evidence for the contribution of racial and ethnic discordance to differences in experimental pain and disparities in clinical outcomes. We propose a framework for understanding the impact of racially and ethnically discordant interactions on the pain experienced by minoritized individuals, focusing on the role of intergroup anxiety experienced by minoritized individuals (Figure 1). We identify factors that may moderate intergroup anxiety and discuss potential ways clinicians can reduce the intergroup anxiety experienced by minoritized individuals in racially and ethnically discordant interactions (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship between racial and ethnic discordance and pain.

Table 1.

Evidence-based strategies for reducing intergroup anxiety in racially and ethnically discordant clinical interactions.

| Patient-focused interventions | Interventional targets |

|---|---|

| Affirmation of core values and beliefs |

Reduces perceived interpersonal threat Reduces social anxiety and discomfort |

| Explicit commitment to participation in care, collaboration, and shared decision-making |

Increases sense of agency and control Increases certainty with regards to behavioral scripts |

| Identification of shared beliefs or values | Increases perceived familiarity and trustworthiness of the interaction partner |

| Provider-focused interventions | |

| Explicit commitment to information-giving, listening, patient-engagement, collaboration, and shared decision-making | Positive intergroup contact Reduces perceived risk Increases sense of agency and control Increases trust |

| Perspective taking (“Imagine how patients’ pain affects their lives”) | Reduces implicit race bias in treatment decision-making Increases provider affiliation behavior |

| Explicit commitment to “being on the same team” | Activates common group identity Improves patient-provider trust |

2. The impact of racial and ethnic discordance on experimental and clinical pain outcomes

Recent experimental studies have found that racial and ethnic group differences between experimenter and participant can influence pain, particularly for minoritized participants[3,41,84]. Anderson et al. [3] examined the role of racial and ethnic discordance on pain and its physiological correlates. In simulated clinical interactions, Black patients paired with racially and ethnically discordant doctors had higher pain and pain-related physiological arousal in response to painful heat stimuli. This pattern was not observed in patients who self-identified as Hispanic, who did not perceive discordant doctors as being significantly different from them in ethnicity or appearance. Vigil et al. [84] examined the effect of having a White experimenter on pain sensitivity among participants self-identifying as Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White. Hispanic participants demonstrated higher pain sensitivity after interactions with non-Hispanic White compared to Hispanic experimenters; 0–18% of the variance in pain sensitivity was due to experimenter characteristics.

It is important to note that despite recent evidence for the impact of racial and ethnic discordance on pain sensitivity, experimental findings are mixed. For example, Weisse et al. [85] did not find evidence for a main effect of racial or gender concordance on pain reporting; interestingly, Black participants had higher pain than White participants when reporting to a female experimenter. Evidence for the impact of patient-provider racial and ethnic concordance on health outcomes more broadly is also mixed. A 2009 systematic review indicated that 33% (9/27) of observational studies found evidence for a positive effect of concordance on health outcomes for minoritized U.S. residents, with 30% (8/27) reporting no effect and 37% (10/27) reporting mixed findings[50]. Inconsistent evidence for the impact of racial and ethnic discordance on health outcomes may be partly due to regional differences in race relations and social climate, unmeasured socioeconomic status, variable study quality, and heterogeneous study participants. This inconsistency also suggests that the impact of discordance on health outcomes is context dependent and, thus, potentially modifiable. Given that racially and ethnically discordant medical interactions are the normative experience for minoritized patients[1], and that the underrepresentation of minoritized providers in medicine is actually worsening across most medical specialties[45], it is essential that we take steps to understand the conditions under which racially and ethnically minoritized individuals may be most vulnerable to increased pain in discordant interactions.

3. Understanding the impact of racial/ethnic discordance on pain: The experience of intergroup anxiety among minoritized individuals

Intergroup anxiety is a social dynamic characterized by a trait-level preference for interactions with same-group members, which can in turn influence state-level anxiety and discomfort during interactions with other-group members[32,78]. Intergroup anxiety can be experienced by members of socially dominant groups and by members of minoritized groups[77]. Likewise, it can be experienced by both (White) providers and (minoritized) patients, with implications for health disparities. Regarding the former, in a recent virtual patient study, Grant and colleagues[32] found White physicians with higher trait-level intergroup anxiety experienced more state-level discomfort with Black patients, which subsequently impacted their pain treatment decisions for these patients. This is consistent with findings from the broader healthcare literature. For example, in a survey of over 1,700 physicians, Cunningham and colleagues[21] found a positive association between physicians’ anxiety and their use of patient race in treatment decisions. Providers who experience high intergroup anxiety may adopt a protective self-presentational style and/or otherwise engage with their minoritized patients in an awkward and strained manner[66], thus harming the clinical relationship and provision of care.

Intergroup anxiety is also experienced by minoritized individuals (patients), which is the primary focus of this topical review. It is important to emphasize that intergroup anxiety is not a psychological defect or shortcoming of minoritized individuals. Rather, it is an adaptive response to historical and ongoing examples of societal mistreatment[20]. Experimental research has found that Black individuals, when interacting with White (compared to Black) social partners, perceive the interaction as more stressful[63,70], have heightened physiological arousal and cardiovascular stress responses[55,65], report greater social anxiety[86], and show heightened amygdala activation associated with threat detection[35]. Beyond the lab, studies show that, after adjusting for socioeconomic inequality, Black individuals report higher distrust in White physicians[19,67], likely owing to their experience of racism both within medicine and society at large. This suggests that intergroup anxiety may be a feature of racially and ethnically discordant clinical interactions.

Below, we highlight several social cognitive processes by which intergroup anxiety exacerbates pain among minoritized individuals in racially and ethnically discordant interactions, while acknowledging that a multitude of processes are likely involved[6].

3.1. Intergroup anxiety and the perceived threat of pain

Higher trait intergroup anxiety is associated with greater perceived or experienced threat in racially and ethnically discordant interactions[79]. The exacerbating impact of interpersonal threat on pain sensitivity has long been acknowledged in the chronic pain literature[92,93]. For example, patients with chronic low back pain are more likely to terminate physical activity prematurely after a stressful spousal interaction[68], and increasing the level of perceived social threat increases pain in healthy participants[57]. In clinical settings, Black patients are more likely than White patients to be racially discriminated against in their ability to obtain pain treatment[52], consistent with the well-documented real effects of racial discrimination in healthcare[34]. This suggests that interacting with a racially and ethnically discordant physician is more interpersonally threatening, and consequently pain-evoking, than interacting with a concordant physician.

3.2. Intergroup anxiety and feelings of distrust

Lack of trust is a well-demonstrated consequence of intergroup anxiety[56,89]. Minoritized individuals’ experience of distrust in medical settings, in particular, stems from a history of unequal treatment and documented racial and ethnic discrimination within medical settings[28,42,88]. In turn, lack of trust is associated with higher pain sensitivity in clinical and experimental settings[4,48]. Conversely, people tend to experience less pain in the presence of others who are perceived as trustworthy and empathic sources of social support. For example, exposure to painful stimuli is associated with less pain intensity and unpleasantness when holding the hand (or viewing a photograph) of a trusted other versus a stranger[15,47,49]. Similarly, greater empathy and verbal reassurance from a social partner are associated with lower pain sensitivity[10,31]. To the extent that minoritized patients experience intergroup anxiety in clinical interactions, we expect their level of distrust for healthcare providers to be heightened, and in turn for racial and ethnic differences in pain sensitivity to be exacerbated.

3.3. Intergroup anxiety and the depletion of attentional resources

The magnitude and quality of emotional responses to painful stimuli is in part regulated by cognitive reappraisal, which engages prefrontal cortex regions that inhibit amygdala and medial orbitofrontal cortex activity[53] to generate alternative emotional responses[54]. Critically, the cognitive reappraisal of pain, involving maintaining attention towards or distraction from pain, requires attentional resources[81] which can be consumed by competing cognitive demands[11,76,87]. Research suggests that in response to intergroup anxiety (specifically, responses that involve vigilance against prejudice or discrimination) minoritized group members may experience more stress and engage in more effortful behaviours requiring greater attention, emotion regulation, and self-control. For example, minoritized individuals who were concerned about being the target of prejudice exerted greater effort – verbal and nonverbal – to smooth interactions with White majority-group members[60]. Consequently, to the extent that minoritized individuals seek to reduce intergroup anxiety via impression management, they may have reduced attentional resources to downregulate their experience of pain, potentially exacerbating racial and ethnic differences in pain sensitivity.

4. Factors moderating the experience of intergroup anxiety

The degree to which racially and ethnically minoritized individuals experience intergroup anxiety in interactions with White individuals varies and may be determined by factors related to the individual, context, or behavior of their interaction partner (Figure 1).

4.1. Individual factors

Intergroup anxiety is associated with minoritized individuals’ anticipation of discrimination[65], concerns about being discriminated against[71] and the negative associated repercussions[61], and – relatedly – previous experiences of race-related rejection[51]. Anderson et al. [3] found that the effects of racial and ethnic discordance on pain-related physiological arousal were largest for patients who previously experienced or currently worried about racial discrimination. Importantly, non-white individuals were more likely to fear racial discrimination, particularly if they or their family has experienced discrimination[38]. Hence, while fear of racial discrimination is an individual factor that may contribute to intergroup anxiety and pain in racial an ethnically discordant interactions, it is inextricably linked with individuals’ experience of racial discrimination. Finally, Rahim-Williams et al. [62] measured participants’ degree of ethnic identification using the Multi-group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) Questionnaire[59] and found that the range (tolerance-threshold) of experimental pain sensitivity was associated with the degree of ethnic identification in Black and Hispanic individuals. Hence, it is possible that degree of ethnic identification also moderates the experience of intergroup anxiety.

4.2. Situational factors

Trait level intergroup anxiety is more likely to evoke discomfort, unease, and feelings of distrust in the context of high-risk or high-stress interactions where one’s health and well-being are perceived to be at stake[8,78]. Patients with chronic pain frequently report that clinical encounters, particularly about opioid prescribing, are stressful and anxiety-provoking[7,27,37]. Intergroup anxiety is also amplified by low familiarity with the outgroup interaction partner or interpersonal situation, and a lack of clear behavioral scripts that embody knowledge of stereotyped event sequences[2,9,30]. In these situations, minoritized individuals may anticipate a difficult interaction, further fuelling anxiety and discomfort.

4.3. Experimenter and provider factors

Intergroup anxiety among minoritized individuals may also be amplified by the implicit attitudes and associated behavior of the experimenter or clinician. Implicit race bias in White individuals is associated with nonverbal expressions of discomfort during interactions with minoritized individuals[24]. The perception of interaction partner anxiety or discomfort reduces liking for and trust in the partner, further escalating intergroup anxiety in racially and ethnically discordant interactions[72]. White experimenters and clinicians may also display less empathy for minoritized participants and patients, further contributing to intergroup anxiety[16,23,29,82]. Indeed, in experimental studies assessing ingroup biases in empathic responding to pain in others (typically measured by viewing painful stimuli applied to racial and ethnic ingroup/outgroup models’ hands), White participants demonstrate reduced emotional reactivity and empathic neural responses to the pain of Black participants[5,90]. Healthcare providers are not immune to this bias, as indicated by findings that nursing professionals exhibit pro-White empathy biases to videos of Black and White patients’ expressing genuine pain[25].

5. Discussion

Racial and ethnic disparities in pain occur against the backdrop of historic and ongoing injustices. In this review, we direct the attention of researchers and clinicians to the potential for racially and ethnically discordant interactions to contribute to differences in experimental pain sensitivity and disparities in clinical pain. We have examined experimental evidence – albeit mixed – for the impact of discordant interactions on pain and proposed several possible mediators and moderators to explain variability in these effects. In the following sections, we discuss evidence-based strategies for mitigating intergroup anxiety and, consequently, reducing racial and ethnic disparities in pain.

5.1. Addressing intergroup anxiety in pain: Potential solutions

Minoritized individuals’ experience of intergroup anxiety is unsurprising in consideration of longstanding racial and ethnic injustices. Nevertheless, evidence-based strategies can facilitate more satisfying and productive racially and ethnically discordant interactions. One involves positive intergroup contact[83]. Positive intergroup contact has four key requirements: the interacting groups must be equal status, work toward common goals, experience intergroup cooperation, and have the support of authorities, laws, and/or customs [91]. In the context of pain management, clinicians can facilitate more positive interactions by validating patients’ experience of pain and beliefs about pain[26,46], by giving informational and emotional reassurance[60], by tailoring treatment advice to the needs and goals of the individual patient, and by respecting patients’ autonomy, concerns, and choice[22]. Concerningly, a recent systematic review indicates that positive intergroup contact is rare for Black patients in healthcare settings, who consistently experience poorer communication quality, information-giving, and participatory decision-making than White patients[73]. Hence, clinicians may need to be more intentional in their communication with minoritized patients.

In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Hirsh et al. [39] tested a perspective-taking intervention to reduce racial bias in physicians’ pain treatment decision-making. Physicians in the intervention group received personalized feedback about their bias, experienced real-time dynamic interactions with virtual patients, and watched videos depicting how pain impacts the patients’ lives. After completing the intervention, physicians had 86% lower odds of demonstrating pain treatment bias. Similarly, Drwecki et al. [25] found that an empathy-inducing, perspective-taking intervention that instructed participants to “imagine how patients’ pain affected patients’ lives” yielded a 55% reduction in pain treatment biases in undergraduates and nursing professionals who viewed videos of patients expressing pain.

Interventions targeting clinician and patient behavior may also improve patient-centeredness and increase minoritized patients’ trust. Penner et al. [58] assigned White and Asian physicians and Black patients to either a task designed to activate a common group identity or a control group. To create a sense of “being on the same team,” physicians and patients in the intervention group followed explicit communication guidelines during their consultations (e.g., “try to find things you can agree about”). Four and sixteen weeks later, patients in the intervention group had greater trust in their physician and greater medication adherence.

Losin et al. [48] experimentally manipulated perceptions of similarity and shared group membership between participants playing the roles of clinicians and patients in simulated clinical interactions. When patients believed they were partnered with clinicians on the basis of shared core beliefs and values, they had greater feelings of similarity and trust during the interaction. Notably, patients’ feelings of similarity and trust were associated with reduced pain sensitivity in response to heat stimuli, suggesting that clinician or patient-driven efforts to identify common interests may counteract feelings of distrust that often imbue discordant interactions, in turn reducing pain sensitivity.

The burden for reducing minoritized patients’ experience of intergroup anxiety in clinical encounters ultimately lies with healthcare providers. There are also steps that minoritized patients themselves can take that may prove empowering in racially and ethnically discordant medical encounters. These strategies may even help protect minoritized patients in situations where systemic biases are present and active. For example, Havranek et al. [36] investigated the impact of a values-affirmation exercise on minoritized individuals’ experience of racially and ethnically discordant medical encounters. Patients in the intervention group reflected on a list of values, identified the most personally relevant, and contemplated times when these values were important and why. These patients subsequently asked more questions, provided more medically-relevant information, and expressed greater positive and less negative emotional tone. The values-affirmation exercise in this study and others[17] is thought to reduce minoritized patients’ anxiety and fear of discrimination by refocusing attention away from perceived interpersonal threats and increasing one’s experience of self-integrity[74]. Hence, while the onus of responsibility for reducing minoritized patients’ experience of intergroup anxiety sits with the clinician, minoritized patients may experience increased empowerment and self-integrity through values-affirmation strategies that can be used to improve the quality of discordant patient-provider interactions. Increased effort is needed to test the feasibility and generalizability of interventions to improve clinician-patient interactions, with a specific goal of enhancing the experiences of minoritized patients.

5.2. Conclusion

Intergroup anxiety among racially and ethnically minoritized individuals is an adaptive response to historical and ongoing oppression[20]—not a psychological defect or shortcoming. As a result of continued lack of diversity and representation in medicine[18], minoritized individuals are more likely to experience intergroup anxiety, further magnifying discrimination and oppression perpetuated by medical settings by (White) practitioners. To directly address persistent and widespread disparities in pain among racially and ethnically minoritized patients, researchers and providers must seek to understand and address both the system-level and proximal factors contributing to these disparities at the point of care. In this review, we consider the role of intergroup anxiety experienced in the context of racially and ethnically discordant interactions as one key contributor to observed racial differences in pain. An important limitation of the available research and consequently of this review is the focus on certain racial and ethnic identities (primarily Black and Hispanic or Latino/a/x) to the neglect of other minoritized communities (e.g. Indigenous, Muslim). Further research is needed to better understand the experience of minoritized communities in pain medicine more broadly. These limitations notwithstanding, we hope that this review will result in (a) increased awareness of intergroup anxiety in clinical care, (b) the implementation of strategies to reduce minoritized patients’ experience of threat, feelings of distrust, and attentional demands in racially and ethnically discordant interactions, and (c) improved pain care for minoritized patients in the face of ongoing systemic oppression.

Acknowledgements

Claire Ashton-James and Steven Anderson contributed to this manuscript equally. We would like to thank Anna Hush and Nicholas Avery for their contributions to the development of the ideas discussed in this paper.

Footnotes

The terms Hispanic and Latina/o/x are not interchangeable. We use the term "Hispanic" to reflect the term used by the authors of the specific studies we reviewed. In cases where participants of specific studies have self-identified as "Hispanic/Latino", we have used the term "Hispanic/Latino/a/x" to be gender inclusive. When referring to non-white populations conceptually, not in relation to a specific research study, we use the term "Hispanic/Latino/a/x" in recognition that there are diverse preferences and perspectives on the terms Hispanic and Latino/a/x within these communities.

References

- [1].AAMC. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2018 to 2033. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Abelson RP. Psychological status of the script concept. American psychologist 1981;36(7):715. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Anderson SR, Gianola M, Perry JM, Losin EAR. Clinician-patient racial/ethnic concordance influences racial/ethnic minority pain: Evidence from simulated clinical interactions. Pain Med 2020;21(11):3109–3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ashton-James CE, Forouzanfar T, Costa D. The contribution of patients’ presurgery perceptions of surgeon attributes to the experience of trust and pain during third molar surgery. Pain Reports 2019;4(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Avenanti A, Sirigu A, Aglioti SM. Racial bias reduces empathic sensorimotor resonance with other-race pain. Current Biology 2010;20(11):1018–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Placebo Benedetti F. and the new physiology of the doctor-patient relationship. Physiological reviews 2013;93(3):1207–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bergman AA, Matthias MS, Coffing JM, Krebs EE. Contrasting tensions between patients and PCPs in chronic pain management: a qualitative study. Pain Med 2013;14(11):1689–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Blair IV, Park B, Bachelor J. Understanding intergroup anxiety: Are some people more anxious than others? Group processes & intergroup relations 2003;6(2):151–169. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Britt TW, Bonieci KA, Vescio TK, Biernat M, Brown LM. Intergroup anxiety: A person× situation approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 1996;22(11):1177–1188. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brown JL, Sheffield D, Leary MR, Robinson ME. Social support and experimental pain. Psychosomatic medicine 2003;65(2):276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Buffum MD, Hutt E, Chang VT, Craine MH, Snow AL. Cognitive impairment and pain management: review of issues and challenges. Journal of rehabilitation research and development 2007;44(2):315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Burgess DJ, Nelson DB, Gravely AA, Bair MJ, Kerns RD, Higgins DM, Van Ryn M, Farmer M, Partin MR. Racial differences in prescription of opioid analgesics for chronic noncancer pain in a national sample of veterans. J Pain 2014;15(4):447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Ethnic differences in pain and pain management. Pain management 2012;2(3):219–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Pain 2005;113(1–2):20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Che X, Cash R, Ng SK, Fitzgerald P, Fitzgibbon BM. A systematic review of the processes underlying the main and the buffering effect of social support on the experience of pain. The Clinical journal of pain 2018;34(11):1061–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cikara M, Bruneau EG, Saxe RR. Us and them: Intergroup failures of empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2011;20(3):149–153. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cohen GL, Garcia J, Purdie-Vaughns V, Apfel N, Brzustoski P. Recursive processes in self-affirmation: Intervening to close the minority achievement gap. science 2009;324(5925):400–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Colleges AoAM. Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019: Association of American Medical Colleges; Washington, DC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med 2003;139(11):907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB,George DMMS. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of internal medicine 2002;162(21):2458–2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cunningham BA, Bonham VL, Sellers SL, Yeh H-C, Cooper LA. Physicians’ anxiety due to uncertainty and use of race in medical decision-making. Medical care 2014;52(8):728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Darnall BD, Ziadni MS, Stieg RL, Mackey IG, Kao M-C, Flood P. Patient-centered prescription opioid tapering in community outpatients with chronic pain. JAMA internal medicine 2018;178(5):707–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dovidio JF, Johnson JD, Gaertner SL, Pearson AR, Saguy T, Ashburn-Nardo L. Empathy and intergroup relations. Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior:The better angels of our nature 2010:393–408. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dovidio JF, Kawakami K, Johnson C, Johnson B, Howard A On the nature of prejudice: Automatic and controlled processes. Journal of experimental social psychology 1997;33(5):510–540. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Drwecki BB, Moore CF, Ward SE, Prkachin KM. Reducing racial disparities in pain treatment: The role of empathy and perspective-taking. Pain 2011;152(5):1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Edlund SM, Wurm M, Holländare F, Linton SJ, Fruzzetti AE, Tillfors M. Pain patients’ experiences of validation and invalidation from physicians before and after multimodal pain rehabilitation: Associations with pain, negative affectivity, and treatment outcome. Scandinavian journal of pain 2017;17(1):77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Esquibel AY, Borkan J. Doctors and patients in pain: conflict and collaboration in opioid prescription in primary care. PAIN® 2014;155(12):2575–2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and US health care. Social science & medicine 2014;103:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Forgiarini M, Gallucci M, Maravita A. Racism and the empathy for pain on our skin. Frontiers in psychology 2011;2:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Frable DE, Blackstone T, Scherbaum C. Marginal and mindful: Deviants in social interactions. Journal of personality and social psychology 1990;59(1):140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Goldstein P, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Yellinek S, Weissman-Fogel I. Empathy predicts an experimental pain reduction during touch. The Journal of Pain 2016;17(10):1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Grant AD, Miller MM, Hollingshead NA, Anastas TM, Hirsh AT. Intergroup anxiety in pain care: impact on treatment recommendations made by white providers for black patients. Pain 2020;161(6):1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kaloukalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 2003;4(3):277–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician–patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020;117(35):21194–21200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hart AJ, Whalen PJ, Shin LM, McInerney SC, Fischer H, Rauch SL. Differential response in the human amygdala to racial outgroup vs ingroup face stimuli. Neuroreport 2000;11(11):2351–2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Havranek EP, Hanratty R, Tate C, Dickinson LM, Steiner JF, Cohen G, Blair IA. The effect of values affirmation on race-discordant patient-provider communication. Archives of internal medicine 2012;172(21):1662–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Henry SG, Matthias MS. Patient-clinician communication about pain: a conceptual model and narrative review. Pain Med 2018;19(11):2154–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Herda D The specter of discrimination: Fear of interpersonal racial discrimination among adolescents in Chicago. Social science research 2016;55:48–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hirsh AT, Miller MM, Hollingshead NA, Anastas T, Carnell ST, Lok BC, Chu C, Zhang Y, Robinson ME, Kroenke K. A randomized controlled trial testing a virtual perspective-taking intervention to reduce race and SES disparities in pain care. Pain 2019;160(10):2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hooper MW, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. Jama 2020;323(24):2466–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hsieh AY, Tripp DA, Ji L-J. The influence of ethnic concordance and discordance on verbal reports and nonverbal behaviours of pain. Pain 2011;152(9):2016–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Johnson SS. Equity, justice, and the role of the health promotion profession in dismantling systemic racism, Vol. 34: SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, 2020. pp. 703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kim HJ, Yang GS, Greenspan JD, Downton KD, Griffith KA, Renn CL, Johantgen M, Dorsey SG. Racial and ethnic differences in experimental pain sensitivity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2017;158(2):194–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lee P, Le Saux M, Siegel R, Goyal M, Chen C, Ma Y, Meltzer AC. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: meta-analysis and systematic review. The American journal of emergency medicine 2019;37(9):1770–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: a longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One 2018;13(11):e0207274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Linton SJ. Intricacies of good communication in the context of pain: does validation reinforce disclosure? Pain 2015;156(2):199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].López-Solà M, Geuter S, Koban L, Coan JA, Wager TD. Brain mechanisms of social touch-induced analgesia in females. Pain 2019;160(9):2072–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Losin EAR, Anderson SR, Wager TD. Feelings of clinician-patient similarity and trust influence pain: evidence from simulated clinical interactions. J Pain 2017;18(7):787–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Master SL, Eisenberger NI, Taylor SE, Naliboff BD, Shirinyan D, Lieberman MD. A picture’s worth: Partner photographs reduce experimentally induced pain. Psychological Science 2009;20(11):1316–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Meghani SH, Brooks JM, Gipson-Jones T, Waite R, Whitfield-Harris L, Deatrick JA. Patient–provider race-concordance: does it matter in improving minority patients’ health outcomes? Ethnicity & health 2009;14(1):107–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mendoza-Denton R, Downey G, Purdie VJ, Davis A, Pietrzak J. Sensitivity to status-based rejection: implications for African American students’ college experience. Journal of personality and social psychology 2002;83(4):896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nguyen M, Ugarte C, Fuller I, Haas G, Portenoy RK. Access to care for chronic pain: racial and ethnic differences. J Pain 2005;6(5):301–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ochsner KN, Bunge SA, Gross JJ, Gabrieli JD. Rethinking feelings: an FMRI study of the cognitive regulation of emotion. Journal of cognitive neuroscience 2002;14(8):1215–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in cognitive sciences 2005;9(5):242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Page-Gould E, Mendoza-Denton R, Tropp LR. With a little help from my cross-group friend: Reducing anxiety in intergroup contexts through cross-group friendship. Journal of personality and social psychology 2008;95(5):1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Pagotto L, Visintin EP, De Iorio G, Voci A. Imagined intergroup contact promotes cooperation through outgroup trust. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2013;16(2):209–216. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Peeters PA, Vlaeyen JW. Feeling more pain, yet showing less: the influence of social threat on pain. The Journal of Pain 2011;12(12):1255–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Penner LA, Gaertner S, Dovidio JF, Hagiwara N, Porcerelli J, Markova T, Albrecht TL. A social psychological approach to improving the outcomes of racially discordant medical interactions. Journal of general internal medicine 2013;28(9):1143–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of adolescent research 1992;7(2):156–176. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Pincus T, Holt N, Vogel S, Underwood M, Savage R, Walsh DA, Taylor SJC. Cognitive and affective reassurance and patient outcomes in primary care: a systematic review. Pain® 2013;154(11):2407–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Plant EA. Responses to interracial interactions over time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2004;30(11):1458–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Rahim-Williams FB, Riley JL III, Herrera D, Campbell CM, Hastie BA, Fillingim RB. Ethnic identity predicts experimental pain sensitivity in African Americans and Hispanics. Pain 2007;129(1–2):177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Richeson JA, Sommers SR. Toward a social psychology of race and race relations for the twenty-first century. Annual review of psychology 2016;67:439–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ringwalt C, Roberts AW, Gugelmann H, Skinner AC. Racial disparities across provider specialties in opioid prescriptions dispensed to Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic noncancer pain. Pain Med 2015;16(4):633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Sawyer PJ, Major B, Casad BJ, Townsend SS, Mendes WB. Discrimination and the stress response: psychological and physiological consequences of anticipating prejudice in interethnic interactions. American Journal of Public Health 2012;102(5):1020–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Schlenker BR, Leary MR. Social anxiety and self-presentation: A conceptualization model. Psychological bulletin 1982;92(3):641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Schouten BC, Meeuwesen L. Cultural differences in medical communication: a review of the literature. Patient education and counseling 2006;64(1–3):21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Schwartz L, Slater MA, Birchler GR. Interpersonal stress and pain behaviors in patients with chronic pain. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 1994;62(4):861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Scott W, Jackson SE, Hackett RA. Perceived discrimination, health, and wellbeing among adults with and without pain: a prospective study. Pain 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Shelton JN, Richeson JA. Ethnic minorities’ racial attitudes and contact experiences with white people. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 2006;12(1):149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Shelton JN, Richeson JA, Salvatore J. Expecting to be the target of prejudice: Implications for interethnic interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2005;31(9):1189–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Shelton JN, Trail TE, West TV, Bergsieker HB. From strangers to friends: The interpersonal process model of intimacy in developing interracial friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 2010;27(1):71–90. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, Hernandez MH, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K, Bylund CL. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities 2018;5(1):117–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Sherman DK, Hartson KA. Reconciling self-protection with self-improvement. Handbook of self-enhancement and self-protection 2011;128. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Slavich GM. Social safety theory: a biologically based evolutionary perspective on life stress, health, and behavior. Annual review of clinical psychology 2020;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Smith MT, Edwards RR, McCann UD, Haythornthwaite JA. The effects of sleep deprivation on pain inhibition and spontaneous pain in women. Sleep 2007;30(4):494–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Stephan WG. Intergroup anxiety: Theory, research, and practice. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2014;18(3):239–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Stephan WG, Stephan CW. Intergroup anxiety. Journal of social issues 1985. [Google Scholar]

- [79].Stephan WG, Ybarra O, Rios K. Intergroup threat theory. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [80].Terrell KM, Hui SL, Castelluccio P, Kroenke K, McGrath RB, Miller DK. Analgesic prescribing for patients who are discharged from an emergency department. Pain Med 2010;11(7):1072–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Tracey I, Ploghaus A, Gati JS, Clare S, Smith S, Menon RS, Matthews PM. Imaging attentional modulation of pain in the periaqueductal gray in humans. Journal of Neuroscience 2002;22(7):2748–2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Trawalter S, Hoffman KM, Waytz A. Racial bias in perceptions of others’ pain. PloS one 2012;7(11):e48546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Turner RN, Hewstone M, Voci A, Vonofakou C. A test of the extended intergroup contact hypothesis: the mediating role of intergroup anxiety, perceived ingroup and outgroup norms, and inclusion of the outgroup in the self. Journal of personality and social psychology 2008;95(4):843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Vigil JM, Coulombe P, Rowell LN, Strenth C, Kruger E, Alcock J, Venner K, Stith SS, LaMendola J. The Confounding Effect of Assessor Ethnicity on Subjective Pain Reporting in Women. The Open Anesthesiology Journal 2017;11(1). [Google Scholar]

- [85].Weisse CS, Foster KK, Fisher EA. The influence of experimenter gender and race on pain reporting: does racial or gender concordance matter? Pain Med 2005;6(1):80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].West TV, Shelton JN, Trail TE. Relational anxiety in interracial interactions. Psychological Science 2009;20(3):289–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Wiech K, Seymour B, Kalisch R, Stephan KE, Koltzenburg M, Driver J, Dolan RJ. Modulation of pain processing in hyperalgesia by cognitive demand. Neuroimage 2005;27(1):59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896(0077–8923):173–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Xu L, Sun L, Li J, Zhao H, He W. Metastereotypes impairing doctor–patient relations: The roles of intergroup anxiety and patient trust. PsyCh Journal 2021;10(2):275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Xu X, Zuo X, Wang X, Han S. Do you feel my pain? Racial group membership modulates empathic neural responses. Journal of Neuroscience 2009;29(26):8525–8529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Zagefka H, González R, Brown R, Lay S, Manzi J, Didier N. To know you is to love you: Effects of intergroup contact and knowledge on intergroup anxiety and prejudice among indigenous Chileans. International Journal of Psychology 2017;52(4):308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Zautra AJ, Berkhof J, Nicolson NA. Changes in affect interrelations as a function of stressful events. Cognition & Emotion 2002;16(2):309–318. [Google Scholar]

- [93].Zautra AJ, Hoffman JM, Matt KS, Yocum D, Potter PT, Castro WL, Roth S. An examination of individual differences in the relationship between interpersonal stress and disease activity among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism:Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology 1998;11(4):271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]