Abstract

Thirteen independent clones that encode Borrelia burgdorferi antigens utilizing antiserum from infection-immune rabbits were identified. The serum was adsorbed against noninfectious B. burgdorferi B31 to enrich for antibodies directed against either infection-associated antigens of B. burgdorferi B31 or proteins preferentially expressed during mammalian infection. The adsorption efficiency of the immune rabbit serum (IRS) was assessed by Western immunoblot analysis with protein lysates derived from infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi B31. The adsorbed IRS was used to screen a B. burgdorferi expression library to identify immunoreactive phage clones. Clones were then expressed in Escherichia coli and subsequently analyzed by Western blotting to determine the molecular mass of the recombinant B. burgdorferi antigens. Southern blot analysis of the 13 clones indicated that 10 contained sequences unique to infectious B. burgdorferi. Nucleotide sequence analysis indicated that the 13 clones were composed of 9 distinct genetic loci and that all of the genes identified were plasmid encoded. Five of the clones carried B. burgdorferi genes previously identified, including those encoding decorin binding proteins A and B (dbpAB), a rev homologue present on the 9-kb circular plasmid (cp9), a rev homologue from the 32-kb circular plasmid (cp32-6), erpM, and erpX. Additionally, four previously uncharacterized loci with no known homologues were identified. One of these unique clones encoded a 451-amino-acid lipoprotein with 21 consecutive, invariant 9-amino-acid repeats near the amino terminus that we have designated VraA (for “virulent strain-associated repetitive antigen A”). Since all the antigens identified are recognized by serum from infection immune rabbits, these antigens represent potential vaccine candidates and, based on the identification of dbpAB in this screen, may also be involved in pathogenic processes operative in Lyme borreliosis.

Lyme disease, caused by various strains of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (referred to as B. burgdorferi throughout this report), is a multistage disorder that presents initially as a flu-like illness and, if untreated, can progress to a chronic state, characterized predominantly by arthritic manifestations in affected individuals in the United States (19, 29, 41–44). As yet, few virulence determinants have been identified for B. burgdorferi even though significant differences have been detected in the plasmid DNA profiles of infectious and noninfectious isolates of in vitro cultivated B. burgdorferi (37, 50). A significant amount of work has been devoted to the identification of plasmid-encoded proteins associated with an infectious phenotype (10, 31, 32). However, identification and characterization of infection-associated proteins have been difficult inasmuch as protein profiles of whole-cell lysates derived from infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi isolates show only subtle variations, even when resolved by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (31). This observation suggests that the genes encoding infection-associated proteins are poorly expressed during in vitro cultivation or that the techniques used for detection were not sensitive enough to account for the slight differences in protein content between the infectious and noninfectious cells. More recently, we (40) and others (8, 31) have analyzed differences in the antigenic profiles from infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi to identify infection-associated antigens expressed during in vitro cultivation and those expressed preferentially during infection (1, 10, 13, 47).

In this report, we describe the use of infection-derived immune rabbit serum (IRS) enriched for antibodies directed against infection-associated antigens to identify cloned genes encoding these molecules from B. burgdorferi phage λ expression libraries. Using this approach, we have identified 13 independent clones. Nucleotide sequence analysis, in conjunction with the recently completed B. burgdorferi genome project (18), indicated that all the clones identified in our screen were plasmid borne and were restricted to nine genes including those encoding the previously described decorin binding proteins A and B (9, 24–26). Inasmuch as the antigens identified in this screen are recognized by serum from infection-immune rabbits, these molecules may serve as a subset of targets for antibody-dependent killing and, as such, may have utility as alternative immunogens to protect against Lyme borreliosis. Additionally, the identification of the decorin binding proteins suggests that other antigens identified in this screen may provide insight into the pathogenesis of Lyme disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31 was used in all studies described in this report. B. burgdorferi was cultured at 32°C in a 1% CO2 atmosphere in BSK II medium (4) supplemented with 6% normal rabbit serum (Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, Ark.). Clonal isolates of B. burgdorferi were isolated by plating agarose overlays containing dilutions of B. burgdorferi as previously described (32). All infectious isolates used were passaged no more than seven times in vitro, and they infect both mice and rabbits (16). The B. burgdorferi B31 noninfectious isolate used in this study has been passaged several hundred times in vitro and has previously been shown to be noninfectious in both mice and rabbits (16).

Escherichia coli ER1647, BM25.8, and BL21 (λDE3) pLysE were purchased from Novagen Inc., Madison, Wis. Strain ER1647 (F− fhuA2 Δ(lacZ)r1 supE44 recD1014 trp31 mcrA1272::Tn10 his-1 rpsL104 xyl7 mtl2 metB1 Δ(mcrC-mrr)102::Tn10 hsdS[rK12− mK12−]) was used for propagating phage λEXlox (Novagen Inc.). Phage λ overlays were plated with 1% Bacto Tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 0.5% NaCl in 0.6% agarose. Strain BM25.8 (F′ [traD36 lacIq lacZΔM15 proAB] supE thi Δ(lac-proAB) [P1] Cmr r− m− λimm434 Kanr) was used for Cre-mediated in vivo excision of plasmid DNA from λEXlox. The rescued plasmids (designated pEX) were isolated from BM25.8 by alkali lysis and were used to transform competent strain BL21 (λDE3) pLysE. The subsequent transformants were then used to express genes encoding B. burgdorferi antigens. All E. coli strains were grown in Luria broth at 37°C with aeration or on either Luria broth or 2× YT agar at 37°C. E. coli was grown in appropriate antibiotics at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 50 μg/ml.

Serum preparation.

Passage 4 B. burgdorferi B31 (4 × 103 cells) was inoculated intradermally into the shaved backs of New Zealand White rabbits, and after approximately 7 to 10 days, lesions similar to erythema migrans (EM) were observed (16). Punch biopsy specimens obtained in and around the location of the EM lesions contained infectious B. burgdorferi as assessed by growth of spirochetes in BSK II medium (16). Additional punch biopsies and necropsy of selected rabbits were conducted over the next 2 months to determine whether the organisms persisted in the skin and viscera, respectively (16). It should be noted that the rabbits were not subjected to antibiotic therapy at any stage of the infection. When organisms were no longer detected in the skin punch biopsy specimens, the rabbits were challenged with 107 cells of passage 4 B. burgdorferi B31. Previous studies indicated that the absence of B. burgdorferi in punch biopsy specimens correlated with the systemic clearance of the spirochetes from the viscera (16). The challenged rabbits did not develop EM lesions, and no culture-positive B. burgdorferi was obtained from either skin punch biopsy specimens or viscera. Serum from these infection-immune rabbits was designated IRS.

To reduce the population of antibodies in IRS that recognize common antigens between infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi and enrich for antibodies specific for infection-associated antigens, we adsorbed IRS with noninfectious B. burgdorferi B31 prepared as described by Gruber and Zingales (23). Briefly, 0.5 liter of noninfectious B. burgdorferi B31 (approximately 1.0 × 1011 to 1.5 × 1011 cells) was grown to late log phase and pelleted at 5,800 × g for 20 min at 5°C, the supernatant was removed, and the resulting pellet was suspended in an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4). The sample was split into two 250-ml volumes; half was autoclaved at 22 lb/in2 and 121°C for 1 h, and the other half was incubated with 0.5% (wt/vol) formaldehyde at 37°C for 2 h with vigorous shaking. Each sample was then centrifuged separately at 5,800 × g for 20 min, washed with an equal volume of PBS, and repelleted as described above. The pellets were then resuspended in 100 ml of PBS, combined, and centrifuged as indicated above, and the final pellet was then resuspended in 15 ml of PBS. For adsorption, 1-ml volumes of the above preparation were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was decanted, and the pellet was combined with 1 ml of IRS. IRS was incubated with the noninfectious B. burgdorferi B31 isolate for 8 h or overnight with rocking at 4°C, after which the insoluble B. burgdorferi fraction was pelleted and the subsequent supernatant was transferred to a new tube for readsorption. This process was repeated until the adsorbed IRS lost reactivity with noninfectious B. burgdorferi B31 as determined by Western immunoblotting (see below).

Construction of the B. burgdorferi λEXlox library.

Chromosomal, linear plasmid, and circular plasmid DNA was isolated from infectious B. burgdorferi B31 passage 4 as previously described (20). Linear and circular plasmid DNA was separated on a CsCl density gradient and enriched as previously described (20) or purified with tip 500 Maxi-prep columns from Qiagen Corp. (Chatsworth, Calif.). All three DNA isolates were digested separately with dilutions of ApoI, and DNA fragments, ranging in size from 0.5 to 4 kb, were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, cut from the gel, purified from the gel with GeneClean (Bio 101, San Diego, Calif.), and ligated to phosphatase-treated λEXlox arms that have EcoRI ends (Novagen). The resulting ligations were packaged in vitro into phage λ by using the Gigapack Gold kit from Stratagene Inc. (San Diego, Calif.) and subsequently amplified to obtain phage lysates on the order of 1 × 1010 to 5 × 1010 PFU per ml. Phage lysates were maintained and stored as outlined by the manufacturer.

To determine whether our libraries were representative, we used antibodies specific for either endoflagella, OspD, or EppA to screen our B. burgdorferi chromosomal, linear plasmid, and circular plasmid libraries, respectively. The Clarke-Carbon formula was used to determine whether each library was representative. Genes that mapped to the telomere-like ends of the chromosome and linear plasmids were absent from their respective libraries.

Screening of the B. burgdorferi expression library.

Nitrocellulose filters (137 mm in diameter) were preincubated in 10 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), dried, and then overlaid separately onto plates (15 by 150 mm) containing approximately 3,000 plaques from each B. burgdorferi phage λ library. After a 4-h incubation at 37°C, the filters were removed and washed with PBS (pH 7.4) to remove excess bound agar and bacteria. The filters were then processed as a conventional Western immunoblot to identify immunoreactive plaques (see below). Briefly, adsorbed immune rabbit serum (see above and references 16 and 40) was incubated with the filters at a dilution of 1:500 in PBS containing 5% powdered milk and 0.2% Tween 20 (PM-PBS-T). After incubation, the filters were washed with PBS–0.2% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and then incubated with a 1:2,500 dilution of goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin with conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in PM-PBS-T. The filters were then washed extensively with PBS-T, and the specific antibody-antigen interaction was identified with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system from Amersham Corp. (Arlington Heights, Ill.). Immunoreactive plaques were selected and rescreened as described above to ensure that a clonal isolate was obtained.

Characterization of recombinant infection-associated clones.

Plasmids encoding B. burgdorferi antigens were isolated as described by Novagen, using E. coli BM25.8 (see above for the genotype) and were designated pEXC, pEXL, or pEXS for those isolated from the chromosomal, linear plasmid, or supercoiled circular plasmid libraries, respectively. The plasmids were then isolated from strain BM25.8 by alkali lysis and used to transform BL21 (λDE3) pLysE. BL21 (λDE3) pLysE cells containing individual pEX plasmids were grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.5) and induced with 0.4 mM IPTG for 2 h at 37°C. The cells were then pelleted, washed with PBS (pH 7.4), and resuspended in Laemmli final sample buffer (28) to a final concentration of 0.01 OD600 unit per μl. Protein from 0.05 to 0.1 OD600 unit of cells was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidine fluoride (Immobilon-P; Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.), and processed for immunoblotting as described below.

Immunoblotting.

Western immunoblotting was conducted essentially as described previously (40). Antisera to DbpA and DbpB were generously provided by Betty Guo and Magnus Höök, Institute of Biosciences and Technology, Texas A&M University, Houston, Tex. Antisera specific for OspD and VlsE were generous gifts from Steven Norris, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, Tex. Monoclonal antibody H9724, specific for B. burgdorferi endoflagella, was generously provided by Alan Barbour, University of California, Irvine, Calif. The adsorbed serum from infection-immune rabbits was prepared as described above. Infection-derived mouse serum was obtained by inoculating mice with 104 CFU of low-passage B. burgdorferi B31 intradermally. After 3 months, the mice were bled and sera from six mice were pooled. Human sera were generously provided by Alan Steere, Tufts University, and were from patients that had documented cases of chronic Lyme borreliosis.

The primary antibodies used were diluted as follows: anti-DbpA, anti-DbpB, and anti-OspD at 1:5,000, anti-EppA (10) at 1:2,000, anti-EF at 1:25, and adsorbed IRS at 1:500 to 1:1,500. Both the mouse and human sera were diluted 1:1,000. Secondary antibodies or protein A conjugated to HRP were purchased from Amersham Corp. Donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin-HRP, sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin-HRP, and protein A-HRP were used at dilutions of 1:5,000, 1:2,500, and 1:1,000, respectively. All blots were developed with the ECL system.

Southern blotting.

Linear or supercoiled, circular plasmid DNA was digested to completion with either EcoRI or HindIII, and the DNA was resolved on 0.8% agarose gels, transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) via capillary transfer overnight, and then cross-linked to the membrane by exposure to UV light for 5 min. Random primed probes were prepared by using the Gene Images kit from Amersham. Briefly, the pEX clones (i.e., template) were diluted to 40 ng/μl in sterile H2O, boiled for 5 min, and placed immediately in a wet ice bath. A 25-μl volume of the appropriate template (i.e., 1 μg) was then added to a collection of random decamer primers, a nucleotide mix containing dATP, dGTP, dTTP, dCTP, dUTP conjugated to fluorescein, and 5 U of Klenow fragment. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and the reaction was continued overnight at room temperature in the dark. After the overnight transfer and cross-linking indicated above, the blot was incubated in 10 ml of prehybridization buffer (75 mM sodium citrate–0.75 M sodium chloride [5× SSC], 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Hammersten’s casein [United States Biochemical, Cleveland, Ohio], 5% dextran sulfate [Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.]) for 1 h at 65°C. During the prehybridization step, the probe was diluted in 5 ml of hybridization buffer (same as the prehybridization buffer listed above), boiled for 5 min, and, following the prehybridization step, added immediately to the blot and incubated at 65°C for 4 h. After 4 h, the probe was removed and stored at −80°C. The blot was rinsed with low-stringency wash buffer (2× SSC, 0.1% SDS) at room temperature followed by two additional 15-min washes at 65°C. The blot was then washed twice in high-stringency wash buffer (0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 65°C for 15 min. The blot was washed in buffer 1 (0.1 M Tris HCl [pH 7.5], 0.15 M NaCl) and then incubated overnight at 4°C in blocking buffer (buffer 1 containing 0.5% Hammersten’s casein). The blot was subsequently incubated for 1 h in blocking buffer containing a 1:1,000 dilution of anti-fluorescein conjugated to HRP (Amersham). After 1 h, the blot was washed five times with buffer 1, developed with the ECL system, and exposed to Kodak XAR-5 film for 10 to 30 min.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of a 2-kb fragment containing the vraA locus (i.e., clone L3) has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF019082.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Preparation of adsorbed immune rabbit serum.

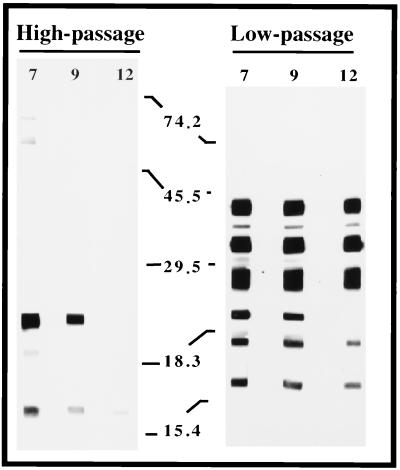

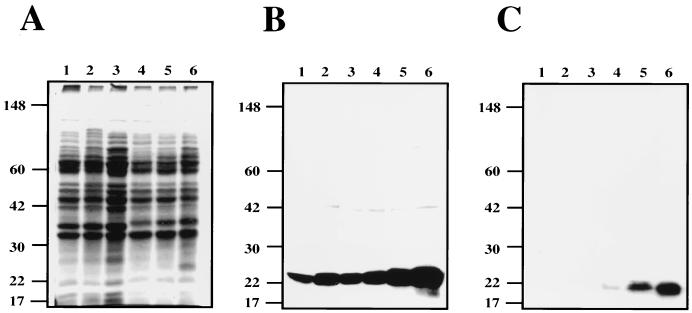

To develop a reagent that would preferentially identify B. burgdorferi antigens that are associated with infectious isolates, we used noninfectious B. burgdorferi B31 to adsorb serum from immune rabbits that were resistant to challenge with 107 CFU of infectious B. burgdorferi B31 passage 4. We then used the adsorbed serum as the primary antibody in a Western blot assay to assess the clearance of antibodies that recognize common antigens by probing whole-cell protein lysates from both in vitro-cultivated noninfectious and infectious (passage 7) B. burgdorferi. As shown in Fig. 1, after either seven or nine adsorptions, some immunoreactive bands were still observed in the noninfectious isolate, although significantly more bands were observed from the infectious isolate. After 12 adsorptions against noninfectious B. burgdorferi, no immunoreactive bands were observed in the noninfectious B. burgdorferi blot, but a subset of antigens retained strong reactivity in the infectious samples, indicating that these are infection-associated antigens (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Demonstration that adsorbed IRS is cleared of common antibodies and contains antibodies specific for infection-associated antigens. IRS was adsorbed as described in Materials and Methods and used as a primary antibody against proteins lysates from either passage 5, infectious strain B31 B. burgdorferi (left) or high-passage, noninfectious strain B31 B. burgdorferi (right). The low-passage and high-passage antigen strips contained protein from 2.5 × 107 and 1 × 108 whole-cell equivalents, respectively. The numbers listed horizontally indicate the number of adsorptions against noninfectious strain B31 B. burgdorferi. Vertical numbers indicate the molecular masses of markers in kilodaltons.

The three major infection-associated antigens had molecular masses of 29, 35, and approximately 40 to 43 kDa. We have retrospectively determined that the highest-molecular-mass, major-infection associated antigen observed by Western blot analysis is VlsE (approximately 40 to 43 kDa [Fig. 1]) (reference 51 and data not shown). Although VlsE is a major immunogen in the rabbit, we did not identify clones encoding this antigen, suggesting that vlsE and other analogous loci located near the telomere-like ends are missing from our chromosomal and linear plasmid libraries. Alternatively, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of our recombinant clones, including those carrying vlsE, were toxic when expressed in E. coli and were subsequently lost during or after the in vivo excision step. The 40- to 43-kDa range observed most probably reflects the fact that the protein lysate used for immunoblotting was derived from a nonclonal population of infectious B. burgdorferi containing different VlsE variants. The 29-kDa antigen is the previously described infection associated lipoprotein, OspD (31). This was determined by screening 20 clones derived from infected C3H/HeJ mouse skin. Infected tissue was grown in liquid medium and plated to isolate individual colonies. Of the 20 clones tested, 4 lacked the 38-kb linear plasmid (lp38), the plasmid known to carry ospD. Additionally, protein lysates from these clones analyzed by Western blotting with antibody specific for OspD showed no immunoreactive species. Subsequent two-dimensional PAGE demonstrated that these clones lacked a spot that immunoreacted with antibody to OspD (data not shown). The 35-kDa antigen has not been definitively identified but most probably represents a p35/p37 paralogous family member (13, 18).

A similar type of analysis was conducted by Carroll and Gherardini (8) to identify antigens that were associated with infectious strains. The profile reported in their study contrasts with what we have observed, perhaps due to the differences pertaining to the sera which were used; that is, the serum used in this study was acquired after approximately 5 months from infection-immune rabbits (16, 40), whereas the serum used in their study was isolated from rabbits at 4 weeks postinfection (8).

Identification and characterization of cloned antigens.

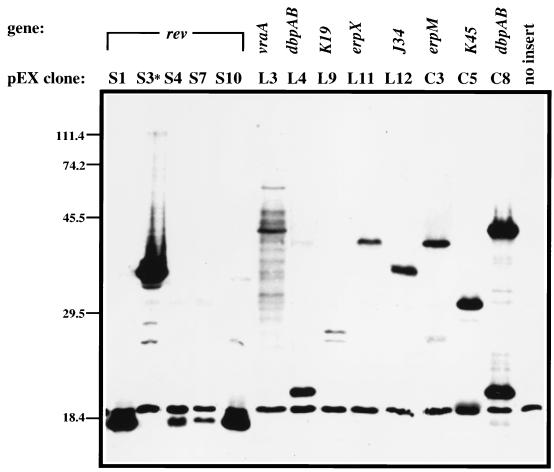

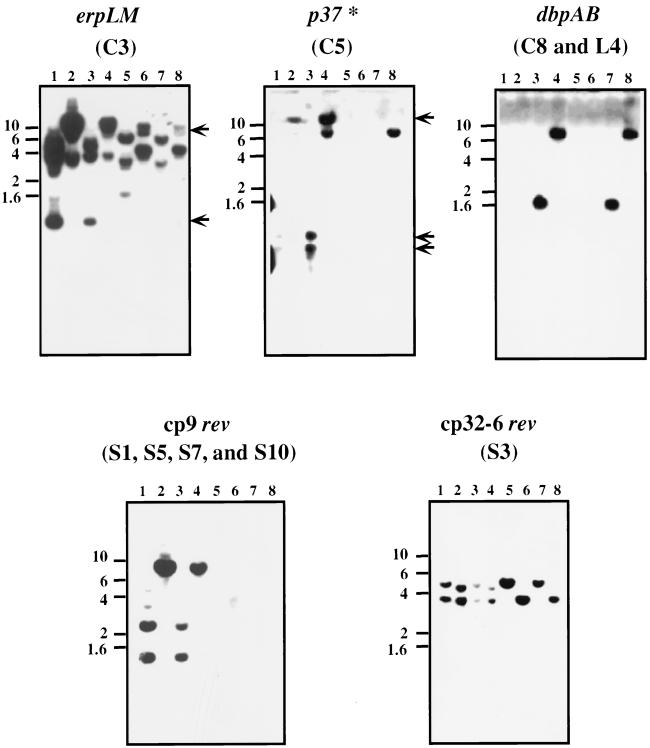

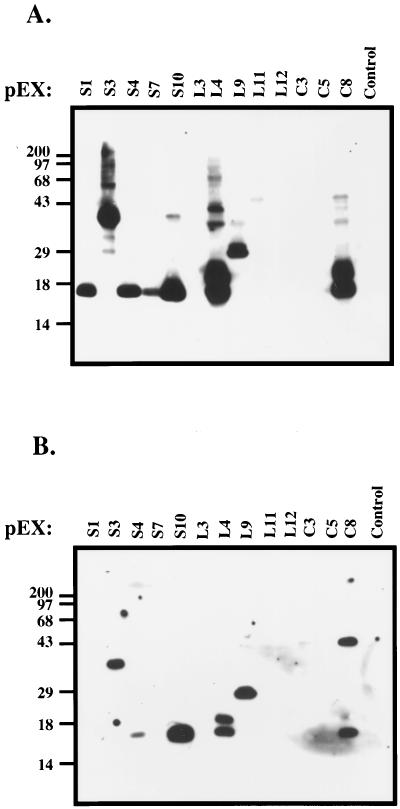

Clones identified in our expression library screen were further analyzed to determine the molecular mass of the recombinant antigens. As shown in Fig. 2, the clones identified encoded proteins that were antigenic, ranging in molecular mass from approximately 18 to 70 kDa. Sequence analysis indicated that the 13 immunoreactive clones encoded nine putative infection-associated antigens and had insert sizes ranging from 302 to 4,343 bp (Table 1 gives a summary). Nucleotide sequence analysis indicated that the 13 clones remaining were composed of nine distinct genes. Seven of the nine genes identified in our screen are carried by plasmids that have been shown by previous investigators (10, 20, 32, 37, 50, 51) and in this study to be lost during in vitro cultivation, while the other two, carrying the genes encoding decorin binding proteins A and B (dbpAB) and the erpX gene, are located on plasmids common to both infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi B31 (Fig. 3, erpX and dbpAB panels), suggesting that dbpAB and erpX are preferentially expressed in the rabbit. The Southern blot data shown in Fig. 3 demonstrates the utility of our screen in terms of identifying loci that are infection associated or expressed in vivo. Therefore, such methodology should be applicable to other systems that are genetically intractable like B. burgdorferi.

FIG. 2.

Molecular mass of recombinant antigens encoded by expression library clones. Immunoreactive clones were identified from phage λ libraries and inserts encoding the antigens excised in vivo as described in Materials and Methods. The clones were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, blotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and incubated with adsorbed immune rabbit serum. Each lane is labeled with the pEX clone designation assigned to each immunoreactive recombinant (see Table 1 for a summary). The asterisk above clone S3 indicates that it contains the rev insert from cp32-6. Vertical numbers indicate the molecular masses of markers in kilodaltons.

TABLE 1.

Summary of expression clones identified

| pEX clone | Plasmid DNAa | Position ofb:

|

Insert size (bp) | TIGR designationc | Genetic locus | Infection associatedd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T7g10 end | SP6 end | ||||||

| S1 | cp9 | 7139 | 5940 | 1,199 | BBC10 | reve | + |

| S3 | cp32-6 | 16838 | 16537 | 301 | BBM27 | revf | + |

| S4 | cp9 | 6866 | 5940 | 926 | BBC10 | reve | + |

| S7 | cp9 | 7551 | 5940 | 1,611 | BBC10 | reve | + |

| S10 | cp9 | 6866 | 6190 | 676 | BBC10 | reve | + |

| L3 | lp28-4 | 7076 | 9712 | 2,636 | BBI16 | vraA | + |

| L4 | lp54 | 17068 | 15035 | 2,033 | BBA24,A25 | dbpAB | − |

| L9 | lp36 | 12084 | 14038 | 1,954 | BBK19 | NDg | + |

| L11 | lp56 | 31373 | 29408 | 1,965 | BBQ47 | erpX | − |

| L12 | lp38 | 26454 | 23852 | 2,602 | BBJ34 | ND | + |

| C3 | cp32-7 | 25206 | 28010 | 2,804 | BBO39,O40 | erpLM | ± |

| C5 | lp36 | 24866 | 29209 | 4,343 | BBK45 | p37h | ± |

| C8 | lp54 | 17177 | 15035 | 2,142 | BBA24,A25 | dbpAB | − |

Indicates the plasmid location of the insert obtained; designation of plasmids is based on TIGR nomenclature. cp, circular plasmid; lp, linear plasmid.

Indicates the exact nucleotide location of the ApoI site in the B. burgdorferi genome in accordance with the TIGR numbering system for the plasmid indicated; also indicates the orientation of the insert relative to the T7 and SP6 sequencing primers that flank the EcoRI site of the pEXlox vector.

See reference 48 for details.

Indicates whether the putative candidate is infection associated at the DNA level; +, DNA fragments are infection associated only; ±, some DNA fragments are infection associated and some are not; −, DNA fragments are indistinguishable between infectious and noninfectious isolates.

rev carried by BBC10 on cp9.

rev carried by BBM27 on cp32-6.

ND, no homologues; genes are uncharacterized.

BBK45 is homologous to the previously characterized p37 locus encoded by BBK50.

FIG. 3.

Southern blot analysis of expression library clones. Southern blot analyses of plasmid DNA derived from infectious (passage 4) and noninfectious B. burgdorferi B31 are shown. Purified circular and linear plasmid DNA was digested with either HindIII or EcoRI, Southern blotted, and probed with the plasmid clone containing the antigen indicated above each frame. The vertical numbers refer to the sizes of markers in kilobase pairs. Arrows indicate bands specific for DNA from infectious B. burgdorferi that are recognized by the erpLM-containing pEXC3 and BBK45-containing pEXC5 probes. The asterisk in panel p37 indicates that this locus is related to the p35/p37 paralogous gene family (48). Lanes: 1 and 2, circular plasmid DNA from passage 4 infectious B. burgdorferi cut with HindIII and EcoRI, respectively; 3 and 4, linear plasmid DNA from passage 4 infectious B. burgdorferi cut with HindIII and EcoRI, respectively; 5 and 6, circular plasmid DNA from high-passage noninfectious B. burgdorferi cut with HindIII and EcoRI, respectively; 7 and 8, linear plasmid DNA from high-passage noninfectious B. burgdorferi cut with HindIII and EcoRI, respectively.

Previous studies have shown a correlation between the loss of a subset of plasmids and a loss of infectivity in animal models of infection (37, 50), suggesting that plasmid-borne genes are required for the infectious phenotype. More recently, Norris et al. has shown that one can discriminate between B. burgdorferi of high- and low-infectivity phenotypes within a nonclonal population of B. burgdorferi based, in part, on the presence of a 28-kb linear plasmid now designated lp28-1 (32), which contains the antigenically variable locus vlsE1 (51). Other independent studies have identified antigens expressed preferentially in vertebrate infection (10, 13, 26, 49), notably ospE or ospE-related proteins (erp genes) (11, 46) and ospF homologues (2). This report incorporates an additional important aspect not evaluated in previous studies, i.e., the use of antibodies from an infected and immune animal to identify antigens either specific for or expressed preferentially in infectious isolates of B. burgdorferi. Inasmuch as the rabbit is the only small-animal model that results in infection-derived immunity in the absence of antibiotic treatment to clear the primary infection and since several studies have indicated the importance of antibodies in B. burgdorferi clearance (5, 27), the genes identified by this approach may have significance to protective immunity. Along these lines, adsorbed immune rabbit serum preferentially binds to the surface of infectious B. burgdorferi (40) and mediates complement-dependent killing of infectious B. burgdorferi (15). Additionally, the identification in our screen of decorin binding protein, a known adhesin of B. burgdorferi (24), supports the likelihood that additional antigens identified in this screen may be important in the pathogenesis of Lyme borreliosis. The following subheadings provide details on the clones identified.

(i) rev (BBC10 [cp9] and BBM27 [cp32-6]).

Nucleotide sequence data, coupled with the recently completed B. burgdorferi genome project, indicated redundancy within our screen for both the rev and dbpAB loci. The rev locus was cloned independently seven times, and the dbpAB locus was cloned twice. Of the seven rev clones isolated, six mapped to the 9-kb circular plasmid (cp9), a previously described B. burgdorferi infection-associated plasmid (10, 37, 50). Two of the six cp9 rev clones were identical and as such have been eliminated from further analyses. Previously, rev had been associated only with cp32 plasmids (21, 36); however, not until the completion of the genomic sequence was it revealed that infectious B. burgdorferi contained three copies of rev that mapped to cp9, cp32-1, and cp32-6 (18, 48). pEX clones S4, S7, and S10 all contain the rev locus found on the 9-kb circular plasmid (cp9) that is distinct from but homologous to the rev loci located by the 32-kb circular plasmids. The cp9 Rev protein is 175 amino acids in length, as opposed to its 160-amino-acid cp32 Rev paralogue. cp9 Rev and cp32 Rev are 37% identical and 51% similar at the amino acid level; however, cp9 Rev contains domains near both the amino and carboxy termini that are unique (data not shown). Whether these domains define an immunodominant infection-associated epitope(s) specific for cp9 Rev is not known. As expected, the Southern blot with either the S1, S4, S7, or S10 clones as probes indicates that cp9 rev is a infection-associated gene enriched for in our circular DNA fractions (Fig. 3, cp9 rev panel).

The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) database indicates that B. burgdorferi B31 contains seven copies of cp32 and that two of these plasmids, cp32-1 and cp32-6, contain the rev locus (48). Clone S3 makes an in-frame fusion to the T7 gene 10 protein, adding 81 residues from cp32 Rev to 260 amino acids of the T7 gene 10 protein (Fig. 2), resulting in the formation of an approximately 38-kDa recombinant fusion protein. This particular rev clone corresponds to the locus reported recently by Gilmore and Mbow (21). Sequence analysis indicated that clone S3 contains the fragment from cp32-6 containing rev that is specific to infectious B. burgdorferi (designated BBM27 by TIGR); however, the S3 probe also recognizes the rev locus present on cp32-1 (designated BBP27 by TIGR). This was determined by analyzing the nucleotide sequences of cp32-1 and cp32-6 present in the TIGR database and comparing the predicted restriction fragments containing rev with the fragments we visualized in our Southern blot analyses (Fig. 3, panel S3). The 3.3-kb EcoRI and 5.5-kb HindIII bands observed in the lanes containing DNA from noninfectious B. burgdorferi correspond to rev-containing fragments from cp32-1, while the lanes containing DNA derived from infectious B. burgdorferi have rev-containing fragments from cp32-1 as well as the 4.7-kb EcoRI and 3.7-kb HindIII rev bands specific for cp32-6. Sequence analysis of clone pEXS3 indicated that the nucleotide sequence matches in its entirety the cp32-6 rev sequence (data not shown). These results, taken together, indicate (i) that clone S3 encodes cp32-6 rev and (ii) that cp32-1 and cp32-6 are both present in our infectious isolates of B. burgdorferi B31 whereas cp32-6 is missing from our noninfectious B. burgdorferi isolate, indicating that it is an infection-associated plasmid. Curiously, the cp32-6 rev probe did not recognize the cp9 rev locus; however, in contrast, cp9 rev did weakly hybridize with the rev-containing 5.5-kb and 3.7-kb HindIII fragments from cp32-1 and cp32-6, respectively (Fig. 3, cp9 rev panel, lane 1).

Although Porcella et al. reported that Rev encoded by B. burgdorferi 297 was processed by a leader peptidase I cleavage site (36), our studies suggest that Rev is processed by leader peptidase II at the lipoprotein consensus sequence VISC for cp9 Rev (residues 19 to 22 of the precursor protein) and VMAC for cp32 Rev (residues 17 to 20 of the precursor protein). More recently, Gilmore and Mbow reported on the cp32 rev locus from B. burgdorferi B31 and demonstrated that serum from patients with documented Lyme infection recognize the Rev protein, suggesting that Rev may have use both as a protective immunogen and in diagnostic applications (21). We are currently in the process of testing the efficacy of Rev in this context.

(ii) vraA (BBI16; lp28-4).

pEXL3 encoded a novel lipoprotein antigen, found only in infectious isolates of B. burgdorferi B31 (Fig. 3, vraA panel), that contains 21 consecutive 9-amino-acid repeats near the amino terminus of the mature protein. Based on this characteristic, we have designated this protein VraA (for “virulent strain-associated repetitive antigen A”). The vraA locus (BBI16 in the TIGR nomenclature [48]) maps to lp28-4 and belongs to a large paralogous gene family (18, 48). However, vraA is distinct from the rest of the paralogous family due to the repetitive units (data not shown). Although we cannot be certain that our screen was exhaustive, it is curious that none of the other paralogues were identified. Since the proteins within this paralogous gene family have significant similarity at their amino and carboxy termini, the most likely choice for the antigenic domain is the repetitive segment. Along these lines, we have prepared fusion proteins and antisera to the (i) mature full-length VraA, (ii) amino-terminal half (containing the repeat units), and (iii) carboxy-terminal half (lacking any of the repeat units) and have determined that the repetitive region is the antigenic domain (3). We are currently evaluating whether the repetitive domain of VraA has any biological activity.

(iii) erp clones: erpM (BBO40; cp32-7) and erpX (BBQ47; lp56).

Two of the immunoreactive clones mapped to erp loci: pEXC3 contained erpM and pEXL11 contained erpX. The erpM locus maps to cp32-7 (designated BBO40 by TIGR [48]), and erpX maps to lp56 (designated BBQ47 by TIGR [48]). Southern blot analysis indicated that the erpM-containing probe recognized sequences from the low-passage, infectious B. burgdorferi B31 as well as sequences unique to the high-passage, noninfectious isolate (Fig. 3, erpLM panel). By accessing the cp32-7 sequence, one can predict which EcoRI and HindIII fragments should hybridize to DNA derived from infectious B. burgdorferi when incubated with the 2,804-bp pEXC3 probe in a Southern blot assay. An EcoRI restriction digest should yield a single 11,532-bp fragment, whereas a HindIII digest should yield 4,675-, 3,744-, 994-, and 111-bp fragments. These predictions are in good agreement with the Southern profile of DNA derived from infectious B. burgdorferi shown in Fig. 3, excluding the weakly reactive 3-kb band in the HindIII digest (Fig. 3, erpLM panel, lane 1) and the 3.5-kb fragment in the EcoRI digest (Fig. 3, erpLM panel, lane 2), which probably reflect hybridizing segments in other cp32 sequences relative to non-erp sequences found in pEXC3. While reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis with erpM primers amplified fragments from both infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi strains, different sizes were detected, suggesting either that the primers recognize common sequences in several cp32 plasmids or that all or some of the cp32-7 sequences are also found in the noninfectious isolates (data not shown). Longer exposures of the Southern blot shown in Fig. 3 (erpLM panel) would seem to suggest the former hypothesis, inasmuch as reactive fragments were also identified in lanes corresponding to the noninfectious isolate, albeit to a lesser extent. However, the different restriction pattern observed for DNA from infectious samples relative to DNA from noninfectious isolates (Fig. 3, erpLM panel, lanes 5 to 8) would suggest either that the cp32-7 sequences have undergone a recombination event or that the pattern observed may be due to the non-erp sequence on the pEXC3 insert. Further studies with erpLM alone as a probe should reconcile these possibilities.

The erpX locus was identified in both the infectious and noninfectious samples (Fig. 3, panel L11), indicating that it is not an infection-associated gene. Although the erpX probe preferentially recognizes linear plasmid DNA, DNA from our circular plasmid sample also hybridizes to the erpX probe, presumably due to related erp sequences on the cp32 plasmids. Subsequent RT-PCR analysis with erpX-specific probes (data not shown) indicated that a transcript is synthesized at low levels in both infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi. This observation is consistent with the recent report by Stevenson et al., who detected a transcript in a Northern blot when total RNA was isolated from B. burgdorferi grown at 35°C, even though no ErpX expression was observed (46). We have independently cloned erpX into an expression vector, overproduced and purified recombinant ErpX, and used this molecule to immunize rabbits. The polyclonal antiserum obtained recognizes nanogram amounts of the recombinant ErpX protein but does not detect native ErpX from protein derived from as many as 3 × 108 infectious or noninfectious B. burgdorferi whole cells grown at 32 or 37°C (data not shown), suggesting that the erpX transcript is not translated, that the level of native ErpX made is well below nanogram amounts, or that ErpX is preferentially synthesized within the infected host, i.e., the rabbit. Further studies are required to reconcile whether translational regulation is operative during in vitro cultivation of B. burgdorferi or whether erpX is significantly upregulated in vivo.

Although the identification of genes like erpX (and dbpAB [see below]), which are found in both infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi, would seem to invalidate the selectivity of our screen, the isolation of erpX in our antibody-based screen can be explained by differential expression of B. burgdorferi genes in vitro relative to arthropod or mammalian hosts. That is, if erpX is not expressed during in vitro cultivation in either infectious or noninfectious B. burgdorferi but is derepressed in infectious B. burgdorferi upon infection of the mammalian host and is antigenic, antibodies would be generated against ErpX. Subsequent adsorption against noninfectious B. burgdorferi, which does not express erpX, would not remove antibodies against ErpX, resulting in their presence in the final adsorbed IRS reagent. Use of this reagent against a B. burgdorferi expression library could then result in the identification of erpX clones.

It is curious that additional erp genes other than erpM and erpX were not also identified in our screen, inasmuch as these genes, or their alleles in other strains of B. burgdorferi, have been identified as encoding in vivo-induced antigens by other investigators (11, 46). Additionally, Erp proteins have significant similarity at the amino acid level, implying that antigenic Erp proteins should have common epitopes. One possible explanation for the limited number of Erp proteins identified in our screen is the lack of a comprehensive screen. This seems unlikely since we had significant redundancy for clones containing rev (i.e., the pEXS series clones). Another possibility is related to differential expression of erp genes in the rabbit relative to murine or human hosts. Nevertheless, it is interesting that ErpM is the most closely related to ErpX of all of the Erp proteins characterized, suggesting that these proteins have related epitopes and that perhaps the identification of clones encoding these antigens may be due to the recognition of common epitopes. Again, we are not certain that continued screening of immunoreactive clones would not yield inserts encoding ErpB2, ErpJ, and ErpD, since all three of these Erp proteins are also similar to both ErpM and ErpX (40 to 46% identity and 49 to 56% similarity relative to ErpX [data not shown]). All of these Erp proteins also contain repetitive sequences, and therefore, in light of the identification of another highly repetitive antigen in our screen (VraA), it is tempting to speculate that the repeat units are defining the epitopes recognized by the adsorbed IRS. For example, ErpX contains five consecutive 5-amino-acid domains (DATGK) located at residues 23 to 47 of the precursor protein that distinguishes it from ErpM (48) as well as from ErpB2, ErpJ, and ErpD. Alternatively, the stretch between residues 91 and 154 of ErpX differs significantly from that in the other Erp proteins, suggesting that this may be an immunoreactive domain (48). Further characterization is required to determine which of these regions specify the ErpX-specific epitope(s) as well as the epitope(s) that defines the recognition of ErpM in our screen.

(iv) dbpAB (BBA24 and BBA25; lp54).

Clones containing dbpAB were identified twice independently in our screen (encoded by pEXL4 and pEXC8). It should be noted that clone pEXC8 encodes an in-frame fusion of the T7 gene 10 protein to most of DbpB, resulting in the production of the approximately 50-kDa species observed in Fig. 2 (Table 1 gives details). Inasmuch as the genes encoding decorin binding protein A and B are observed in both infectious and noninfectious isolates of B. burgdorferi (Fig. 3), the identification of dbpAB clones in our screen would seem to contradict the infectivity-associated specificity of our screen. However, our data suggest that DbpB is made at very low levels in noninfectious cells grown at 37°C yet is derepressed significantly in infectious B. burgdorferi cells grown at 37°C, i.e., conditions that simulate vertebrate infection (Fig. 4C). Therefore, when infectious B. burgdorferi enters the mammalian host, dbpAB is probably upregulated and DbpA and DbpB are synthesized and processed by the rabbit immune system, resulting in a significant humoral response to these antigens. In contrast, during in vitro cultivation at 32 or 37°C, noninfectious cells make very low levels of DbpB (Fig. 4) yet synthesize an appreciable amount of DbpA. Thus, when noninfectious cells with little DbpB on their surface were used to adsorb out common antibodies, antibodies generated against DbpB were not eliminated. Antibodies to DbpB presumably resulted in the isolation of the dbpAB-containing clones pEXL4 and pEXC8 (Fig. 2). Recently, Hagman et al. demonstrated that dbpA and dbpB are contained on a single polycistronic mRNA, suggesting that the low levels of DbpB made may be due to translation-regulatory mechanisms (25). As indicated above for erpX, the identification of genes found in both infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi does not invalidate our screen. We contend that the different classes of clones identified expose the bias inherent to our antigen-based screen and further highlight the complexity of gene expression when in vitro cultivated B. burgdorferi is compared with host-adapted B. burgdorferi.

FIG. 4.

Temperature regulation of dbpA and dbpB. Protein lysates derived from B. burgdorferi B31 noninfectious cells (lanes 1 through 3) and infectious cells (passage 4; lanes 4 through 6) grown at 23°C (lanes 1 and 4), 32°C (lanes 2 and 5), or 37°C (lanes 3 and 6) were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue (A) or immunoblotted and probed with antiserum specific for either DbpA (B) or DbpB (C). Numbers on the left refer to the molecular mass of protein markers (in kilodaltons).

(v) Additional, uncharacterized infection-associated loci.

The additional three loci identified in this report have been designated BBK19, BBK45, and BBJ34 by TIGR (18). The TIGR genome sequence indicates that BBK19 and BBK45 map to lp36 and that BBJ34 maps to lp38. Our assignment of the genetic loci encoding these antigens is based on the correlation between the molecular mass of these antigens observed in Fig. 2 and the potential open reading frames present on these cloned inserts (Table 1) (18). The BBJ34 antigen shows 24% identity and 40% similarity to a 50-kDa surface-exposed lipoprotein from Mycoplasma hominis that has adhesin activity and is a phase-variable antigen (7). Whether BBJ34 functions as an adhesin in B. burgdorferi has yet to be determined. No homologues have been identified, and no function has been attributed to the gene product of BBK19. By comparison, BBK45 is one of four genes that comprise a paralogous gene family (18). Paralogous family 75 (18) contains BBK45, BBK46, BBK48, and BBK50. Of these loci, only BBK50 has been previously characterized and corresponds to the p37 locus characterized by Fikrig et al. (13). Alignment of BBK45 and BBK50 indicates that these two P37 proteins have 38% identity and 52% similarity at the amino acid level (data not shown). Fikrig et al. demonstrated that BBK50 is preferentially expressed within an infected mouse but not during in vitro cultivation of B. burgdorferi and confers passive protection against B. burgdorferi challenge. In contrast, our RT-PCR results indicate that BBK45 is expressed during in vitro cultivation of infectious B. burgdorferi (data not shown). Since we do not have a monospecific antibody reagent against BBK45 P37, we do not know whether our P37 protein is synthesized in vitro. Alternatively, it is possible that p37 transcription is similar to that reported for the erp genes, where transcription does not necessarily guarantee that translation of the corresponding protein will ensue (46). Whether the P37 homologue encoded by BBK45 is regulated in this manner remains to be elucidated.

Southern blot data obtained with BBJ34 and BBK19 as probes indicates that these genes are definitive infection-associated loci (Fig. 3, panels J34 and K19). In contrast, Southern blots obtained with pEXC5 as a probe indicate that p37-like sequences are also present in noninfectious B. burgdorferi. This is most probably due to the additional genes present on the BBK45-containing pEXC5 plasmid, including BBK40, BBK41, BBK42, BBK43, and BBK44. Of these five additional loci, BBK40 belongs to the paralogous gene family 113, which contains numerous genetic loci, some of which are present on plasmids common to noninfectious B. burgdorferi strains (48).

Relation of infection-associated and non-infection-associated antigens to pathogenesis and protective immunity.

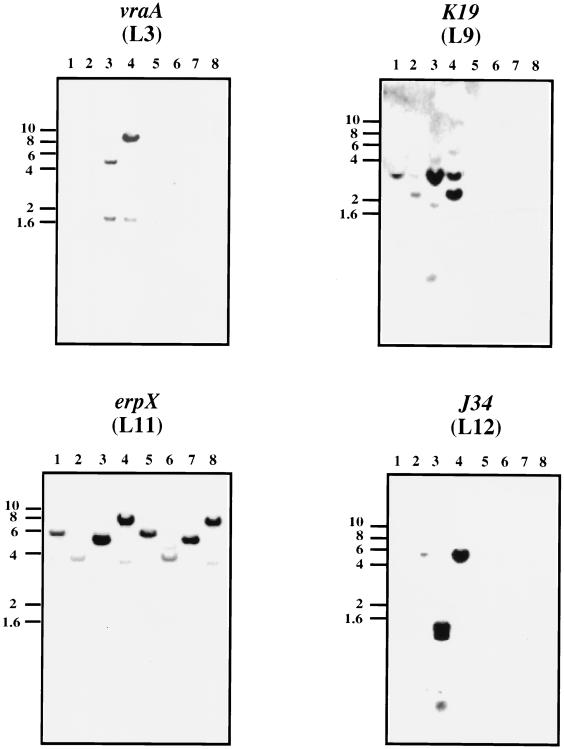

Recently, several investigators have demonstrated that the ospA locus is downregulated in vertebrates (6, 9, 30) or under conditions where ticks have fed to repletion on a murine host (12, 38). Experimental evidence supports the contention that antibodies directed against OspA kill B. burgdorferi within the midgut of an infected tick when ticks obtain a blood meal from a mammalian host (14). As such, OspA is now purported to be an arthropod-specific vaccinogen (12) and has been tested in human trials (39, 45). Recently, it was determined that OspA and a human leukocyte antigen share a cross-reactive epitope, suggesting that antibodies against OspA recognize an autoantigen which may contribute to some of the autoimmune pathologic findings associated with chronic arthritic manifestations (22). Since OspA is downregulated in the vertebrate host and since the kinetics of OspA turnover are not well understood, we, along with others (11, 13, 17, 26, 33–35), have suggested that additional vaccine candidates, either separately or in combination with OspA, should be evaluated to determine their ability to protect against the population of OspA-less B. burgdorferi that would not be cleared by OspA antibodies. The type of screen described in this study, involving antibodies directed against antigenic proteins in the rabbit, i.e., expressed within a rabbit mammalian host that develops complete immunity to challenge reinfection (16), provides an alternate approach to identify potential second-generation vaccine candidates. Furthermore, the rabbit humoral response appears to be qualitatively and quantitatively more robust than the immune response elicited by other animal models, most notably C3H/HeJ and HeN mice, as well as chronically infected humans. This can be assessed qualitatively by evaluating the immunoreactivity in a Western blot assay of the recombinant antigens identified in this screen with antiserum from chronically infected humans or pooled mouse sera (Fig. 5) relative to the antigens recognized by the adsorbed rabbit antiserum (Fig. 2). Differences in the humoral response between these serum samples include (i) the two Erp antigens (ErpM and ErpX), which are weakly recognized by the human and pooled mouse sera, and (ii) the cp9 Rev antigen, which is recognized by the human serum (Fig. 5A) but is identified only in clones S3, S4, and S7 when probed with the pooled mouse sera (Fig. 5B). Three of the antigens recognized by the adsorbed rabbit serum but not detected by serum from a chronically infected human or by pooled mouse sera are the p37 homologue (BBK45), the antigen encoded by the BBJ34 locus, and what we have described as VraA (BBI16). Our preliminary data indicates that the VraA antigen also protects against B. burgdorferi infection, suggesting that the clearance of B. burgdorferi from infected rabbits may be mediated in part by the immune response against this and perhaps other antigens identified in our screen (data not shown). Along these lines, Hanson et al. have recently shown that decorin binding protein A, an antigen found in both infectious and noninfectious B. burgdorferi strains and also identified in this study, protects against experimental Lyme borreliosis in the mouse model of infection (26).

FIG. 5.

Recognition of B. burgdorferi recombinant antigens by infection-derived human sera (A) and pooled mouse sera (B). The samples shown were processed as described in Materials and Methods. Each lane is labeled with the pEX clone designation assigned to each immunoreactive recombinant (see Fig. 2 and Table 1 for a summary). Vertical numbers indicate the molecular masses of markers in kilodaltons.

With the advent of the B. burgdorferi genome project and the existing DNA array technology, it is now possible to assess differential gene expression in B. burgdorferi by simulating conditions within the arthropod vector or mammalian hosts. We are in the process of addressing these issues experimentally, more specifically in regard to the expression of the infection-associated genes identified in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ellen Shang, Cheryl Champion, and Maria Labandeira-Rey for helpful discussions and Yi-Ping Wang, Xiao-Yang Wu, and Jason Barranco for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Research Service Award AI-09117 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) (to J.T.S.), a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association (to J.T.S.), NIAID training grant AI-07323 (to J.T.S. and D.M.F.), Public Health Service (PHS) grants AI-21352 and AI-29733 (both to M.A.L.), and PHS grant AI-37312 (to J.N.M.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins D R, Bourell K W, Caimano M J, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. A new animal model for studying Lyme disease spirochetes in a mammalian host-adapted state. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:2240–2250. doi: 10.1172/JCI2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akins D R, Porcella S F, Popova T G, Shevchenko D, Baker S I, Li M, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Evidence for in vivo but not in vitro expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein F (OspF) homologue. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, E. A., and J. T. Skare. Unpublished data.

- 4.Barbour A G. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J Biol Med. 1984;57:521–525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barthold S W, Bockenstedt L K. Passive immunizing activity of sera from mice infected with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4696–4702. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4696-4702.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barthold S W, Fikrig E, Bockenstedt L K, Persing D H. Circumvention of outer surface protein A immunity by host-adapted Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2255–2261. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2255-2261.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boesen T, Emmersen J, Jensen L T, Ladefoged S A, Thorsen P, Birkelund S, Christiansen G. The Mycoplasma hominis vaa gene displays a mosaic gene structure. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:97–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll J A, Gherardini F C. Membrane protein variations associated with in vitro passage of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1996;64:392–398. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.392-398.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassatt D R, Patel N K, Ulbrandt N D, Hanson M S. DbpA, but not OspA, is expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi during spirochetemia and is a target for protective antibodies. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5379–5387. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5379-5387.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Champion C I, Blanco D R, Skare J T, Haake D A, Giladi M, Foley D, Miller J N, Lovett M A. A 9.0-kilobase-pair circular plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi encodes an exported protein: evidence for expression only during infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2653–2661. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2653-2661.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das S, Barthold S W, Giles S S, Montgomery R R, Telford III S R, Fikrig E. Temporal pattern of Borrelia burgdorferi p21 expression in ticks and the mammalian host. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:987–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI119264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Silva A M, Telford III S R, Brunet L R, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi OspA is an arthropod-specific transmission-blocking Lyme disease vaccine. J Exp Med. 1996;183:271–275. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fikrig E, Barthold S W, Sun W, Feng W, Telford III S R, Flavell R A. Borrelia burgdorferi P35 and P37 proteins, expressed in vivo, elicit protective immunity. Immunity. 1997;6:531–539. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fikrig E, Telford III S R, Barthold S W, Kantor F S, Spielman A, Flavell R A. Elimination of Borrelia burgdorferi from vector ticks feeding on OspA-immunized mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5418–5421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foley, D. M., D. R. Blanco, M. A. Lovett, and J. N. Miller. Unpublished data.

- 16.Foley D M, Gayek R J, Skare J T, Wagar E A, Champion C I, Blanco D R, Lovett M A, Miller J N. Rabbit model of Lyme borreliosis: erythema migrans, infection-derived immunity, and identification of Borrelia burgdorferi proteins associated with virulence and protective immunity. J Clin Investig. 1995;96:965–975. doi: 10.1172/JCI118144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foley D M, Wang Y P, Wu X Y, Blanco D R, Lovett M A, Miller J N. Acquired resistance to Borrelia burgdorferi infection in the rabbit. Comparison between outer surface protein A vaccine- and infection-derived immunity. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:2030–2035. doi: 10.1172/JCI119371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischmann R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J, Venter J C, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Monco J C, Benach J L. Lyme neuroborreliosis. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:691–702. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giladi M, Champion C I, Haake D A, Blanco D R, Miller J F, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Use of the “blue halo” assay in the identification of genes encoding exported proteins with cleavable signal peptides: cloning of a Borrelia burgdorferi plasmid gene with a signal peptide. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4129–4136. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.13.4129-4136.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilmore R D, Jr, Mbow M L. A monoclonal antibody generated by antigen inoculation via tick bite is reactive to the Borrelia burgdorferi Rev protein, a member of the 2.9 gene family locus. Infect Immun. 1998;66:980–986. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.980-986.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross D M, Forsthuber T, Tary-Lehmann M, Etling C, Ito K, Nagy Z A, Field J A, Steere A C, Huber B T. Identification of LFA-1 as a candidate autoantigen in treatment- resistant Lyme arthritis. Science. 1998;281:703–706. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5377.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruber A, Zingales B. Alternative method to remove antibacterial antibodies from antisera used for screening of expression libraries. BioTechniques. 1995;19:28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo B P, Norris S J, Rosenberg L C, Höök M. Adherence of Borrelia burgdorferi to the proteoglycan decorin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3467–3472. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3467-3472.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagman K E, Lahdenne P, Popova T G, Porcella S F, Akins D R, Radolf J D, Norgard M V. Decorin-binding protein of Borrelia burgdorferi is encoded within a two-gene operon and is protective in the murine model of Lyme borreliosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2674–2683. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2674-2683.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanson M S, Cassatt D R, Guo B P, Patel N K, McCarthy M P, Dorward D W, Höök M. Active and passive immunity against Borrelia burgdorferi decorin binding protein A (DbpA) protects against infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2143–2153. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2143-2153.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson R C, Kodner C, Russell M. Passive immunization of hamsters against experimental infection with the Lyme disease spirochete. Infect Immun. 1986;53:713–714. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.713-714.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Logigian E L, Kaplan R F, Steere A C. Chronic neurologic manifestations of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1438–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011223232102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montgomery R R, Malawista S E, Feen K J, Bockenstedt L K. Direct demonstration of antigenic substitution of Borrelia burgdorferi ex vivo: exploration of the paradox of the early immune response to outer surface proteins A and C in Lyme disease. J Exp Med. 1996;183:261–269. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norris S J, Carter C J, Howell J K, Barbour A G. Low-passage-associated proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi B31: characterization and molecular cloning of OspD, a surface-exposed, plasmid-encoded lipoprotein. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4662–4672. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4662-4672.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norris S J, Howell J K, Garza S A, Ferdows M S, Barbour A G. High- and low-infectivity phenotypes of clonal populations of in vitro-cultured Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2206–2212. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2206-2212.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philipp M T. Studies on OspA: a source of new paradigms in Lyme disease research. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:44–47. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Philipp M T, Johnson B J. Animal models of Lyme disease: pathogenesis and immunoprophylaxis. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90800-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Philipp M T, Lobet Y, Bohm R P, Jr, Roberts E D, Dennis V A, Gu Y, Lowrie R C, Jr, Desmons P, Duray P H, England J D, Hauser P, Piesman J, Xu K. The outer surface protein A (OspA) vaccine against Lyme disease: efficacy in the rhesus monkey. Vaccine. 1997;15:1872–1887. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porcella S F, Popova T G, Akins D R, Li M, Radolf J D, Norgard M V. Borrelia burgdorferi supercoiled plasmids encode multicopy tandem open reading frames and a lipoprotein gene family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3293–3307. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3293-3307.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwan T G, Burgdorfer W, Garon C F. Changes in infectivity and plasmid profile of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, as a result of in vitro cultivation. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1831–1836. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.1831-1836.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwan T G, Piesman J, Golde W T, Dolan M C, Rosa P A. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2909–2913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sigal L H, Zahradnik J M, Lavin P, Patella S J, Bryant G, Haselby R, Hilton E, Kunkel M, Adler-Klein D, Doherty T, Evans J, Molloy P J, Seidner A L, Sabetta J R, Simon H J, Klempner M S, Mays J, Marks D, Malawista S E. A vaccine consisting of recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface protein A to prevent Lyme disease. Recombinant Outer-Surface Protein A Lyme Disease Vaccine Study Consortium. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:216–222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skare J T, Shang E S, Foley D M, Blanco D R, Champion C I, Mirzabekov T, Sokolov Y, Kagan B L, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Virulent strain associated outer membrane proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Investig. 1995;96:2380–2392. doi: 10.1172/JCI118295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steere A C. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:586–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908313210906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steere A C. Musculoskeletal manifestations of Lyme disease. Am J Med. 1995;98:44S–51S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steere A C, Batsford W P, Weinberg M, Alexander J, Berger H J, Wolfson S, Malawista S E. Lyme carditis: cardiac abnormalities of Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:8–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steere A C, Malawista S E, Snydman D R, Shope R E, Andiman W A, Ross M R, Steele F M. Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three connecticut communities. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:7–17. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steere A C, Sikand V K, Meurice F, Parenti D L, Fikrig E, Schoen R T, Nowakowski J, Schmid C H, Laukamp S, Buscarino C, Krause D S. Vaccination against Lyme disease with recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface lipoprotein A with adjuvant. Lyme Disease Vaccine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:209–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevenson B, Bono J L, Schwan T G, Rosa P. Borrelia burgdorferi Erp proteins are immunogenic in mammals infected by tick bite, and their synthesis is inducible in cultured bacteria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2648–2654. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2648-2654.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suk K, Das S, Sun W, Jwang B, Barthold S W, Flavell R A, Fikrig E. Borrelia burgdorferi genes selectively expressed in the infected host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4269–4273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The Institute for Genomic Research Web Sitea. copyright date. [Online.] http://www.tigr.org/tdb/CMR/gbb/htmls/SplashPage.html. [14 July 1999, last date accessed.] 16 October 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wallich R, Brenner C, Kramer M D, Simon M M. Molecular cloning and immunological characterization of a novel linear-plasmid-encoded gene, pG, of Borrelia burgdorferi expressed only in vivo. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3327–3335. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3327-3335.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu Y, Kodner C, Coleman L, Johnson R C. Correlation of plasmids with infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto type strain B31. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3870–3876. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3870-3876.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J R, Hardham J M, Barbour A G, Norris S J. Antigenic variation in Lyme disease borreliae by promiscuous recombination of VMP-like sequence cassettes. Cell. 1997;89:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]