Abstract

Microparticulate drug delivery system (MDDS) has attained much consideration in the modern era due to its effectiveness in overcoming traditional treatment problems. Microparticles (MPs) are spherical particles of a diameter ranging from 10 μm to 1000 μm. MPs can encapsulate both water-soluble and insoluble compounds. MDDS proved their efficacy in improving drugs bioavailability, stability, targeting, and controlling their release patterns. MPs also offer comfort, easy administration, and improvement in patient compliance by reducing drugs toxicity and dosage frequency. This review elucidates the fabrication techniques, drug release, and therapeutic application of MDDS. Further details concerning the therapeutic applications of antidiabetic drugs-loaded MPs were also reviewed, including controlling drugs release by gastroretention, improving drugs dissolution, reducing side effects, localizing drugs to the site of disease, improving insulin stability, natural products loaded with MPs, sustained drug release, mucosal delivery, and administration routes. Additionally, the current situation and future prospects in developing MPs loaded with antidiabetic drugs were discussed.

Keywords: Microparticles, Antidiabetic drugs, Insulin, Hypoglycemic drugs, Diabetes, Targeting

Introduction

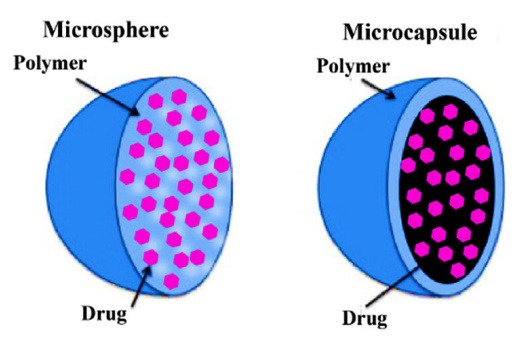

Microparticles (MPs) are small spherical entities with a diameter ranging from 10 μm to 1000 μm, in the form of free-flowing powders. 1 They are developed from different components as inorganic, polymeric, and minerals. In addition, MPs can exist in various structural designs, for example, microgranules, micropellets, microcapsules, microsponges, microemulsions, magnetic MPs and lipid vesicles as liposomes and niosomes. 2 The most common type of MPs are the polymeric MPs, which are made from natural biodegradable or synthetic polymers and designed into two main structures MPs and microspheres. The matrix of the MPs consists of a homogeneous mixture of polymers, copolymer, and active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). Meanwhile, microspheres refer to a core comprised of either solid or liquid surrounded by a coat of distinctly different materials from the core (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of microparticles: a) matrix microparticle; and b) microcapsule

Polymeric MPs mainly comprise polymers which determine their structure and significantly affect their properties. Ideally, polymers should be inert, stable, safe, biodegradable, biocompatible, and low cost. 3 A wide range of polymers is used to prepare MPs derived from numerous natural and synthetic sources. Table 1 shows examples of different types of polymers. 4-6

Table 1. Types of polymers used in microparticle formulations 4-6 .

| Natural Polymers | Synthetic Polymers | |||

| Proteins | Polysaccharides | Waxes | Biodegradable | Non-biodegradable |

| Albumin | Starch | Beeswax | Carboxymethyl cellulose sodium | Fumaryl diketopiperazine |

| Gelatine | Chitosan | Carnauba wax Paraffin | Methylcellulose | Polyethene glycols |

| Casein | Sodium alginate | Hydroxypropyl cellulose | Poly-(N-isopropyl acrylamide) | |

| Whey protein | Poly dextran | Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose | Acrolein | |

| Soy protein | Pectin | Ethylcellulose | Epoxy polymers | |

| Gluten | Sodium hyaluronate | Cellulose acetate butyrate | ||

| Zein | Guar gum | Poly (lactic acid) | ||

| Konjac gum | Polylactic acid-glycolic acid copolymer | |||

| Carrageenans | Polyacrylic acid (Carbopol) | |||

| Agarose | Polymethacrylates | |||

| Tragacanth | ||||

| Gum Arabic | ||||

| Gellan gum | ||||

| Xanthan gum | ||||

The drug released from the MPs can be modulated depending on the nature of the polymer. Loading drugs at higher concentrations into the MPs, i.e., high entrapment efficiency, can be optimized based on the polymer type. 7 In addition, studies proved that particle size directly affects the drug loading capacity, where reduction in particle size leads to a reduction in drug loading capacity and vice versa. 8

Commonly, the surface morphology of the MPs originates from the chemical nature of the particle and the method of MP fabrication. It can be detected by different means, such as scanning electron microscopy. The surface morphology influences the properties of MP, such as wettability and adhesiveness. 9 It was reported that the wettability of MPs is improved upon a higher number of surface asperities and roughness. On the other hand, the surface roughness was found to have an inverse effect on the adhesion of particle. 10 As the surface roughness increases, the pull-off force is significantly reduced, thereby decreasing the adherence properties of the MPs. 11

Another crucial aspect that should be considered during MPs preparation and characterization is electric charge of particles. Zeta potential is the standard analytical method of surface charge determination in a colloidal system. It can be used to determine the long- and short-term stability of the microparticulate colloidal dispersion. The colloidal system with high zeta potential (negative or positive) is regarded as an electrically stable system owing to the repulsive forces between particles. Low zeta potentials systems are at risk of coagulation or flocculation, possibly leading to poor physical stability. 12

Microparticulate drug delivery system (MDDS) attracts attention due to its wide range of beneficial technological characteristics. Compared with the conventional dosage forms, MDDS offers numerous advantages, such as ensuring controlled and prolonged drug release pattern, 7 reducing drugs dose and toxicity, improving drugs bioavailability, and enhancing the solubility of poorly soluble drugs due to their very wide surface area. Furthermore, they protect the drug from the in vitro/in vivosurrounding environment, target the drug to a specific biological site of action, mask the unsuitable taste and odour, and reduce dosing frequency, thus improving patient compliance. 13-19 However, MDDS must be safe for successful clinical applications, perform therapeutic functions, provide comfortable administration routes, and be easily manufactured. The production of the MDDS showed some limitations due to its low reproducibility, costly materials, and manufacturing procedure, as well as some of their components and excipients that degrade into hazardous materials, which could be harmful to the environment. 2 However, many novel microparticulate products are currently in clinical trials; however, some have been made available on the market. Table 2 demonstrates examples of commercially marketed products containing MPs. 20-30

Table 2. Commercially marketed products formulated using microparticles .

| Trade name | Generic name | Pharmaceutical company | Indication | Particle type | Reference |

| Micro-K® Extencaps® | Potassium chloride extended-release | Ther- R.X. corporation | Hypokalemia | Microcapsules | 20 |

| Cotazym® | Pancrelipase | Organon | Pancreatic insufficiency | Microcapsules | 21 |

| Lupron Depot® | leuprolide acetate | Abbott Laboratories | Management of endometriosis | Microspheres | 22 |

| Nutropin Depot® |

Somatropin (rDNA origin) |

Genentech, Inc | Hormone deficiency | Microparticles | 23 |

| Sandostatin® LAR | Octreotide acetate | Novartis | Severe diarrhoea and flushing episodes associated with metastatic carcinoid tumors | Microparticles | 24 |

| Trelstar® | Triptorelin pamoate | Actavis Specialty Pharmaceuticals Co. | Palliative treatment of advanced prostate cancer | Microgranules | 25 |

| Vivitrol® | Naltrexone | Alkermes, Inc. | Prevention of relapse to opioid dependence | Microspheres | 26 |

| Decapeptyl® | Triptorelin pamoate | Ferring Pharmaceuticals | Metastatic prostate cancer | Microparticles | 27 |

|

Risperdal Consta® |

Risperidone | Vetter Pharma Fertigung GmbH & Co. KG. | Antipsychotic | Microspheres | 28 |

| Bydureon® | Exenatide | AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals L.P. | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Microspheres | 29 |

| Signifor® LAR | Pasireotide | Recordati Rare Diseases, Inc. | Acromegaly | Microspheres | 30 |

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has emerged as a global health problem in the past few decades and has been declared the fifth leading reason for mortality in most countries, 31 as DM is deemed a fundamental risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and renal problems. 32 Basically, DM is a chronic hyperglycemic metabolic disorder that occurs due to multiple causes and is characterized by the improper metabolism of fats, carbohydrates, and protein. 33 There are two main types of DM: type 1 and type 2. Absolute deficiency of insulin is the primary cause of type 1 DM. In contrast, impaired insulin secretion, insulin resistance, and increased glucose production are the causes of type 2 DM. Therefore, both DM types can be treated with insulin. However, hypoglycemic drugs can be used to manage type 2 DM. 34

Despite the numerous antidiabetic medications that are flooding into the pharmaceutical market, a complete cure of DM remains unattained mainly due to the serious adverse effects of these drugs, such as hypoglycemia, gastric irritation, nausea, diarrhoea, and injection phobia, among others. 35 Eventually, these drugs will result in poor patient compliance and low adherence to treatment. Therefore, designing a stable and non-invasive drug delivery along with controlled-release could be more therapeutically effective. 36

Most significantly, the literature reported that microparticulate formulations could be promising to maintain a controlled blood concentration of the antidiabetic medications, 37 improve the dissolution and release of drug, 38 and ultimately, enhance their pharmacokinetics and bioavailability. 39 Furthermore, surface modified and mucoadhesive MPs showed advantages in a protective effect against enzymatic degradationand enhancing peptide stability 40 in addition to site-specific drug delivery 36 and gastric retaining. 41

The literature revealed that the field of drug delivery has moved at an unprecedented pace, and a variety of drug delivery systems have taken centre stage over the past decade. Therefore, this review includes an inclusive outline of MDDS and focuses on their therapeutic applications as efficacious carriers for antidiabetic drugs and illustrates the global trend of research conducted in this area.

Fabrication techniques of MDDS

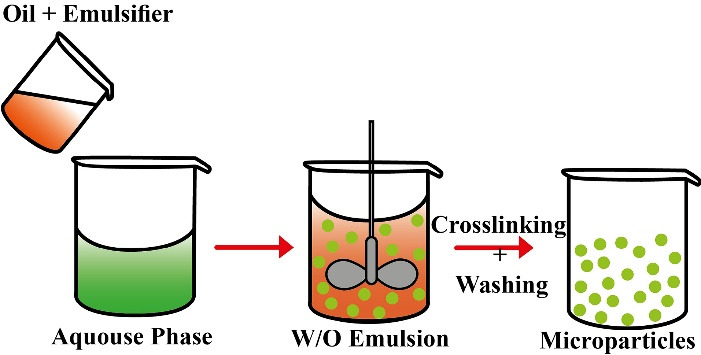

Single emulsion technique

This method is used to prepare natural polymers-based MPs as proteins and carbohydrates. First, the polymer is dissolved in the aqueous medium, followed by its dispersion in a non-aqueous solvent as oil. Then, crosslinking of the dispersion is performed either by heating or using chemical crosslinkers as glutaraldehyde (Figure 2). The type of surfactant favorably influences the particle size, particle charge, surface morphology, drug loading, drug release, and bio-performance of the MPs. 42

Figure 2.

Single emulsion technique for the preparation of microparticles.

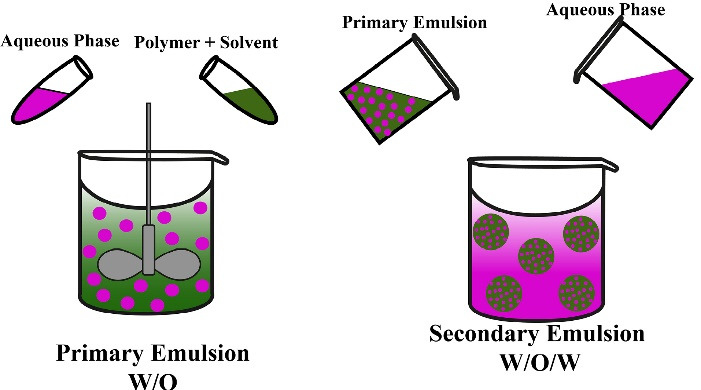

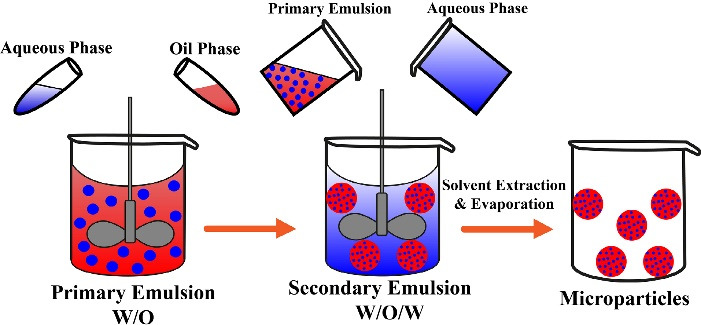

Double emulsion technique

Double emulsion technique comprises the formulation of double emulsions water-in-oil-in-water (w/o/w) or oil-in-water-in-oil (o/w/o). Both natural and synthetic polymers can be incorporated to prepare MPs. The double emulsion w/o/w (Figure 3) is more suitable for water-soluble drugs, peptides, proteins, and vaccines. For example, a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) agonist was successfully encapsulated into the MPs using the double emulsion method. 43

Figure 3.

Double emulsion technique for the preparation of microparticles

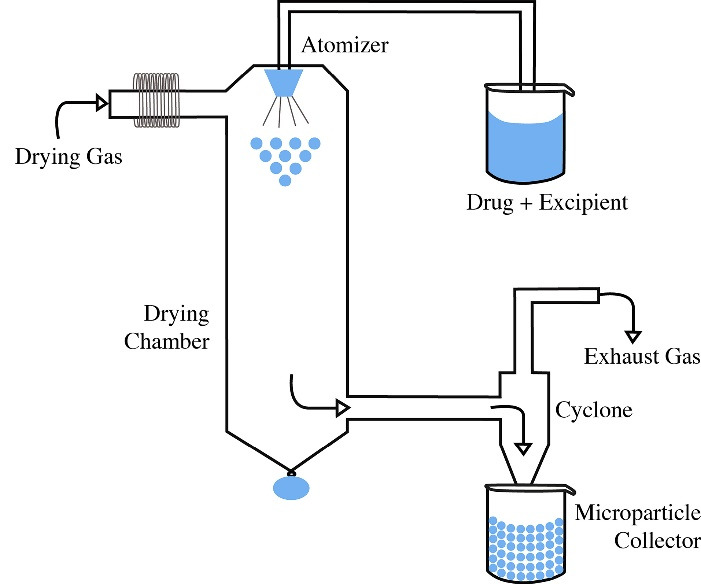

Spray drying technique

Both the polymer and the drug are dissolved in a volatile organic solvent and homogenized in a high-speed homogenizer (Figure 4). Subsequently, the resulting dispersion is sprayed in a hot air stream, where the solvent evaporates instantaneously and the MPs are formed. 44

Figure 4.

Spray drying technique for the preparation of microparticles

Solvent extraction

The solvent extraction or evaporation method is performed by dissolving the drug and the polymer in a suitable organic solvent. The mixture is then dispersed in an aqueous surfactant solution with stirring to form an emulsion. 45 Finally, the MPs are collected after solvent evaporation (Figure 5). The main advantages of this method is the shorter hardening time and direct incorporation of the drug into the MPs.

Figure 5.

Solvent extraction technique for the preparation of microparticles

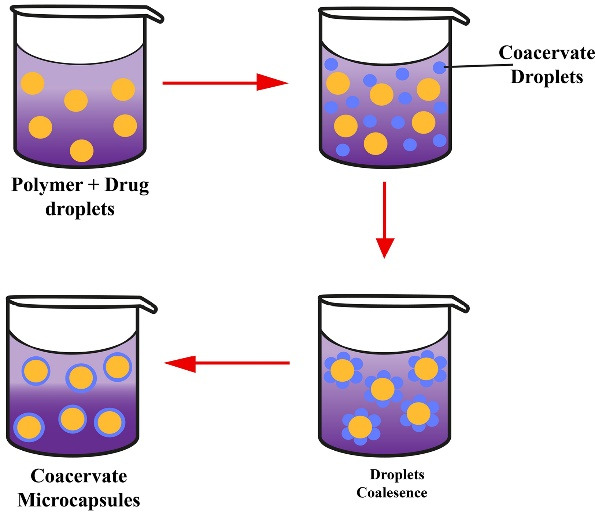

Phase separation coacervation technique

This technique principally prepares the reservoir systems to encapsulate hydrophilic drugs, such as peptides and proteins. Its principle relies on the reduced polymer solubility in the organic phase to form a polymer-rich phase called a coacervate. Then, a third component is added to the system to separate the coacervate, forming two phases: supernatant and polymer-rich phases (Figure 6). In addition, phase separation can be achieved by different techniques such as salt, non-solvent, or incompatible polymer addition. 46

Figure 6.

Phase-separation coacervation technique for the preparation of microparticles

Factors affecting drug release from MDDS

Drug release from MPs is affected by several factors, including:

Drug content

The drug release rate is affected by the amount of drug present in the MP, where the release increases with increasing drug concentration in the MP. 47

Drug physical state

The physical state, molecular dispersion/crystalline structures of a drug affect the drug release kinetics from the MPs. 48

Molecular weight of polymer

The molecular weight of polymer affects its erosion, where the molecular weight is inversely proportional to the release rate. Therefore, as the molecular weight increases, the diffusivity decreases, thus resulting in a lower drug release rate. In addition, many drugs are released by diffusion through water-filled pores, where the polymer degrades to form soluble monomers and oligomers. Hence, there is faster development of these tiny products, with the polymers having a lower molecular weight. 49

Copolymer concentration

The co-monomer ratio in copolymers affects the drug release rate; when a more rapidly degrading monomer is used in the polymer, the release rate increases. Likewise, the release rate depends on the polymer erosion, in which the use of smaller and more soluble monomers will result in increased release rate. 50 Nevertheless, the copolymer composition may be influenced by difference in the phase behavior of polymer or the thermodynamics of encapsulated active ingredient. For example, Zhang et al prepared poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA)-based MPs for the oral delivery of a poorly water-soluble drug, progesterone, to improve its physiological dissolution and bioavailability. It was found that the in vitro drug release was directly influenced by the copolymer composition; hence, the reduction of lactide content of PLGA was able to achieve further drug release. 51

Types of excipients

Excipients have various crucial functions in the formulation; for example, they may influence the release of a drug through various mechanisms and its encapsulation effectiveness. Yanget al improved the encapsulation and uniformity of size distribution of bovine serum albumin (BSA) in MPs by including polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) in the formula. The increased PVA concentration increased the porosity of the MPs and controlled the release of BSA. 52 Jain et al prepared myoglobin MPs-containing mannitol as a stabilizer. Their results showed that the addition of mannitol had improved the release rate of myoglobin by increasing the initial porosity of the MP’s matrix, leading to faster formation of the pore network within the sphere. 53

Nature of the polymer

The type of polymer used in MPs formulation and the functional groups that affect polymer degradation significantly affect its release rate. Polymers are categorized into two types: surface eroding and bulk-eroding. For bulk-eroding polymers, such as PLGA, this type of polymer allows rapid water permeation into the MP matrix, thus causing polymer degradation and a drug burst, where 50% of the drug is released during the first hour of the run, followed by a controlled release. 54 Meanwhile, the surface-eroding polymers as polyanhydrides are made of hydrophobic monomers linked by labile bonds. It resists water penetration and degrades into oligomers and monomers at the polymer/water interface via hydrolysis. The drug release occurs at the surface as the polymer degrades. 55

MPs size

Generally, the size of MPs impacts the loading capacity of the drug into the MPs and the drug release profile. 4 As the particle size decreases, the ratio of their surface area to volume increases, and thus, the diffusion of drug particles and the release rate increases. On the other hand, the small-sized of the MPs results in a higher penetration of water into the particles and their decomposition, causing an immediate burst release of their content rather than the continuous release of the drug from the particle surface. 56

Environmental pH

Some pilot studies have shown that the pH of the medium significantly affects the degree of hydration and swelling of crosslinked hydrophilic polymers. 57 The swelling of the polymer having acidic or basic functional groups depends upon the pH of the surrounding medium relative to the corresponding pKa and pKb values of the functional groups. For instance, in the anionic polymer (e.g. having carboxylic, –COOH functional groups), the ionization of the acidic functional groups results in the production of negative charges on the surface of the polymer that can interact with the opposite positive charges in the medium. In addition, polymer erosion is also affected by the environmental pH. Hence, the swelling and or degradation of the pH-sensitive polymer that controls the drug-release profile from the MPs are affected. 58

Moreover, the degree of ionization of the functional groups on the surface of the polymer and the surface of the mucous membrane, is also influenced by the hydrogen ion concentration in the surrounding medium. Therefore, the time and degree of contact between MPs-including mucoadhesive polymers and the absorption site are influenced. 59 Researchers proved that positively charged polymers, such as chitosan, 60 showed better mucosal adhesive properties than anionic polymers, providing favorable drug release and absorption conditions.

Route of administration

Several formulation concepts are used to manufacture MDDS through different routes of administration, such as the transdermal, oral, ophthalmic, vaginal, and pulmonary for drug inhalation. Each of these routes of administration is characterized by certain physiological factors, such as tissue structure, pH of the medium, permeability barriers, and metabolic enzymes, all of which ultimately govern the release pattern and mechanism of the drug from the microparticulate carriers. 61

Therapeutic applications of antidiabetic loaded microparticles

Since its discovery, MDDS has been extensively investigated and successfully used to encapsulate water-insoluble and water-soluble drugs. In addition, antidiabetic drugs, including insulin, were incorporated into MDDS due to their beneficial properties such as improving therapeutic efficacy, gastroretentive drug release, targeting medicinal compounds, improving insulin stability, reducing side effects, enhancing drugs dissolution, and attaining patient compliance.

Controlled gastroretentive drug release

One of the main methods of improving drug bioavailability is to retain the formulation in the stomach for a long duration. 62 Various antidiabetics-loaded gastroretentive drug delivery systems had been proposed and evaluated (Table 3), including the floating and mucoadhesive MPs. The buoyancy of the MPs can be achieved when their bulk density is less than that of the gastric fluid.

Table 3. Various gastroretentive delivery systems for antidiabetic medications .

| Type of System | Antidiabetic API | References |

| Floating microspheres/microparticles | Repaglinide | 41 |

| Rosiglitazone maleate | 63 | |

| Gliclazide | 64 | |

| Sitagliptin | 65 | |

| Metformin HCl | 66,67 | |

| Effervescent floating tablets | Pioglitazone HCl | 68,69 |

| Metformin HCl | 70,71 | |

| Rosiglitazone HCl | 72 | |

| Non-effervescent floating tablets | Linagliptin | 73 |

| Microsponges/microballons | Mitiglinide calcium | 74 |

| Metformin HCl | 75,76 | |

| Rosiglitazone maleate | 77 | |

| Mucoadhesive matrix tablets | Metformin HCl | 78 |

| Rosiglitazone maleate | 79 | |

| Repaglinide | 80 | |

| Mucoadhesive microspheres | Linagliptin | 81 |

| Glipizide | 82 | |

| In situ hydrogel/superporous hydrogel | Mitiglinide calcium | 83 |

| Rosiglitazone maleate | 84 |

Another approach is preparing hollow MPs, so the formula stays buoyant in the stomach without affecting gastric emptying time and rate. MPs release the drug faster by floating on the gastric content resulting in an increased gastric residence time and controlled plasma concentration. 85 In addition, the distinctive advantages of floating MPs reduce dosage frequencies, and possibility of mucosal adhesion and dose dumping. 86

Dubey et al prepared the floating microspheres to retain metformin in the stomach and continuously release the drug in a controlled manner up to a predetermined time. 87 Other studies followed the same technique to improve repaglinide’s bioavailability and efficacy. 88 Furthermore, Shams et al loaded repaglinide successfully into floating microspheres prepared from different viscosity grades of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) polymer. It was predicted that the prepared repaglinide-loaded floating microscopic globules can provide a novel choice for a safe, economic, and increasingly bioavailable formulation to treat diabetes effectively. 89

On the other hand, metformin hydrochloride was loaded to gastric-mucoadhesive MPs for sustained gastric residence time. Carbopol-934P/ethyl cellulose polymers as mucoadhesive MPs were prepared via the emulsification solvent evaporation technique. Results proved that incorporating metformin into the MPs would increase the drug bioavailability and improve glucose control in diabetic patients. 71

Improving drug dissolution

Oral bioavailability depends on several factors, including aqueous solubility and dissolution rate. Further studies suggested MPs to enhance the solubility and dissolution rate of the lipophilic hypoglycemic drugs. For example, conventional glibenclamide tablets’ low oral bioavailability necessitated a novel formulation, MPs, to improve its low water solubility. 90 Siafaka et al also developed polymeric MPs for oral delivery of glibenclamide using two biocompatible polymers, poly(e-caprolactone) and poly(butylene adipate). The in vitro drug release from the MPs was higher than that of the pure drug and in a sustained pattern ideal for reducing the daily dose of glibenclamide. 14 Tzankov et al investigated the mesoporous silica MPs to improve glimepiride solubility and dissolution rate. The newly developed MPs were investigated in vitro and in vivo and found to possess high loading capacity and safe promising carriers to enhance the solubility of poorly soluble hypoglycemic drugs. 91

Moreover, pioglitazone solubility and dissolution were improved by its incorporation into hydrophilic MPs. The MPs were prepared by spray-drying technique from two water-soluble components, poloxamer 407 and β-cyclodextrin. The spray-dried particles significantly increased the percentage of drug release rate compared to the control, pure pioglitazone. 92

Reducing side effects

Generally, drug side effects are a fundamental obstacle in the development of therapeutic agents. Among various modified drug delivery systems, polymeric MPs are employed to enhance drugs safety and therapeutic activity. For the past few decades, MDDS had been extensively studied on its ability to deliver drug molecules to the target site of action to minimize undesired harmful effects and improve patients’ safety and compliance. 93 For example, Volpatti et al were able to produce glucose-responsive insulin delivery systems in an injectable formulation for blood glucose control and hypoglycemic avoidance. The glucose-responsive delivery system was developed by encapsulating glucose-responsive, acetylated-dextran MPs in porous alginate microgels to improve glycemic control by releasing insulin into the blood, thereby detecting an elevation in the blood glucose levels. 94

Moreover, catechin is a natural molecule that possesses antidiabetic activity, but a significant disadvantage of it is that it causes obesity. To overcome this problem, scientists have encapsulated catechin into Eudragit RS100 MPs. Results showed no signs of obesity in rat models even after 60 days of oral administration. 95 Repaglinide requires frequent administration due to its short half-life, which may cause many adverse effects, as skeletal muscles pain, headache, and gastrointestinal (GI). 96 Sharma et al encapsulated the drug into microspheres to modify the drug release, thereby controlling its concentration for a prolonged duration and reducing its side effects. 41 Ethyl cellulose MPs containing metformin HCl were developed by emulsification solvent evaporation technique. The sustained release of the drug from these MPs was more prominent at a phosphate buffer of pH 6.8 than in the simulated gastric medium. Thus, the authors proposed ethyl cellulose MPs as a convenient carrier for water-soluble hypoglycemic drugs as metformin HCl in managing type 2 DM. 97

Targeting drugs to the site of disease

Magnetic microparticles

The magnetic MPs were employed to localize the drug to the site of the disease. The freely circulating drug was targeted to the receptor site and maintained at the therapeutic concentration for a specific period. This mechanism was achieved by incorporating nano/micromagnets into the polymeric MPs, e.g., chitosan and dextran, and exposing them to an external magnetic field for their immobilization. 98 There are two types of magnetic MPs: therapeutic magnetic MPs and diagnostic magnetic MPs, where the former one was used to deliver proteins, peptides, and chemotherapeutic agents to tumors as liver tumors 99 ; and the latter was used for imaging liver metastases, distinguishing bowel loops from other abdominal structures by forming nano-sized particles super-magnetic iron oxides. 100 The literature is full of studies that report magnetic particulate carriers for delivering antidiabetic medications to a localized disease site. In a previous study, the influence of polymer composition on insulin release was investigated by exposing ethynyl vinyl acetate MPs to the oscillating magnetic field. 101 Insulin-magnetite- PLGA MPs were orally administered to mice in the presence of an external magnetic field. A significantly improved hypoglycemic effect (blood glucose levels reduced to 43.8%) was observed, indicating the efficacy of the magnetic microspheres in oral insulin therapeutics. 102

Moreover, Teply et al prepared the negatively charged insulin-loaded PLGA MPs-complexed with positively charged micromagnets. The complexes were effectively localized in a mouse small intestine in vitro model by an external magnetic field application, indicating that the complexes encapsulating insulin (120 units/kg) were stable. They exhibited long-term blood glucose reduction in the mice groups fitted with magnetic belts and significantly improved insulin bioavailability compared to the control. 103 Alginate-chitosan beads containing magnetite nanoparticles were placed as a system to control insulin release in the presence of an oscillating magnetic field. Beads entrapment efficiency was 35%, and the magnetic field increased three times in the insulin release. 104

pH-Sensitive microparticles

Situ et al prepared insulin-loaded oral bioadhesive MPs coated with a resistant starch-based film to deliver antidiabetic bioactive drugs to the colon. The starch was chemically modified to enhance its stability and resistibility to GI enzymatic degradation. Results proved the MPs’ effectiveness to control the average plasma glucose levels up to 22 hours in diabetic rats. Then further development for the resistant starch-based coat was conducted through its conjugation with concanavalin A glycoprotein. The modified coat showed better colon targeting and maintained the hypoglycemic effect of insulin for 44–52 hours in diabetic rats. 105

Another approach for colon targeting was attempted by preparing sodium alginate MPs containing the bile salts as permeation enhancers. Gliclazide was loaded into sodium alginate MPs containing chenodeoxycholic acid 106 and deoxycholic acid 107 bile salts. The formulations showed extended gliclazide in vitro release profiles and successful colon targeting properties. Leong et al developed pH-responsive carboxymethylated kappa-carrageenan MPs to protect insulin from GI degradation. The prepared formula was further surface-lectin-functionalized to enhance the intestinal mucoadhesion. The surface-modified formulation demonstrated accurate colon targeting and could maintain the hypoglycemic effect for up to 24 hours in diabetic rats. 108 Chitosan-snail mucin MPs were prepared for pH-sensitive oral delivery of insulin. In vitro release profile of insulin was evaluated in two pH environments (pH 1.2 and pH 7.4) in animal models. Results showed retarded release in the acidic medium; however, the continuous release of the alkaline medium was prolonged for up to 12 hours. Animal models controlled the normal average blood glucose levels for up to 8 hours. 40

Improving insulin stability

Insulin instability in the gut limits its administration to the parenteral route only. Several approaches had been proposed to overcome this problem to improve oral insulin stability and bioavailability. For instance, Sajeesh et al complexed methyl-β-cyclodextrin to polymethacrylic acid hydrogel MPs to be tested for oral insulin delivery in diabetic animal models. Cyclodextrin was responsible for stabilizing insulin by reducing its self-aggregation. Results also showed enhancement in insulin’s oral absorption. 109 Carboxymethyl β-cyclodextrin grafted carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogel MPs were found promising for oral insulin administration. 110 Another study was performed by encapsulating insulin into mucinated sodium alginate MPs. The MPs effectively lowered blood glucose levels in rabbit diabetic models after 5 hours of their oral administration. MPs surface modification is another technique that was tried for oral insulin delivery. Chitosan-snail mucin based microspheres were fabricated and loaded with insulin. The loading capacity was high, and the in vitro release was above 80% over 12 hours. The insulin-loaded MPs significantly reduced blood glucose levels in mice compared to the positive control, and the effect continued for 8 hours. 111 Acryl-EZE enteric polymer-coated MPs containing surfactin and iturin lipopeptides could achieve only 7.67% of oral relative bioavailability of insulin. Nevertheless, these MPs maintained the postprandial blood glucose level of about 50% of the initial dose, similar to the subcutaneous injection. 112 In addition, glucan MPs thickened with thermosensitive poloxamer 407 gels were suggested to be potential insulin oral carriers. 113

The multilayer-coated MPs using a layer-by-layer polymers installation was another assessed approach. Balabushevich et al generated the layer-by-layer MPs from dextran sulfate and chitosan polymers. 114 Meanwhile, in another study, the MPs were coated with alternating layers of poly(vinyl alcohol) and poly(acrylamide phenyl boronic acid-co-N–vinyl caprolactam) on the surface of PLGA MPs. 115 Shrestha et al prepared the annealed thermally hydrocarbonized porous silicon (AnnTHCPSi) and undecylenic acid-modified AnnTHCPSi (AnnUnTHCPSi) MPs for oral insulin delivery. The surface of MPs was modified using chitosan to enhance insulin’s intestinal permeation. Insulin intestinal permeation was evaluated in Caco-2/HT-29 cell co-culture monolayers. The chitosan-coated MPs showed a significant improvement in insulin penetration through the cells. 116

Natural products-loaded MPs

Gongronema latifolium is a conventional herbal medicine plant used to treat various diseases, including diabetes. The plant extract was loaded into the solid-lipid MPs with a retention efficiency of 68%. In addition, the mean percentage reduction in blood glucose after oral administration of the extract loaded MPs was 76% and 24.4% compared to the reference glibenclamide, which resulted in 82.6% and 46.7% at 2 and 12 hours, respectively. 117

Catechin a natural molecule that possesses antidiabetic activity. Its low oral bioavailability limits its uses. However, catechin encapsulation into Eudragit RS100 MPs significantly improved its absorption and reduced blood glucose levels in diabetic rats. The blood glucose level of the catechin MP treated group was found to be (119.37 ± 12.46 mg/dL) after 60 days of treatment compared to (206.54 ± 9.54 mg/dL) of the hyperglycemic rats. 95

Berberine active constituent is found in several plants as European barberry, goldenseal, Oregon grape, and tree turmeric. It has attracted much interest in recent years due to its potential as a natural alternative to other synthetic antidiabetic drugs. Unfortunately, the low oral bioavailability is limiting its development for further clinical treatments. Recently, researchers have attempted to improve its oral hypoglycemic effect by incorporating the berberine-phospholipid complex into the phytosomes delivery system. 118 Some bioflavonoids, such as rosmarinic acid from the plant Lamiaceae, had been used as antidiabetic drugs and antioxidants. Rosmarinic acid crosslinked MPs contributed a more substantial inhibitory effect on α-glycosidase along with reduced cytotoxicity and antioxidant activity than the free compound. 119

Sustained drug release

Various strategies were investigated for the extended-release formulations of antidiabetic drugs such as matrix sustained-release tablets, orodispersable tablets, and depots. 120-122 Nevertheless, MDDS had granted great attention to this application. Biodegradable polymeric MPs were used extensively to retard drug release, reduce dosing frequency, and enhance bioavailability and safety. 123 The biodegradable MPs are made from either natural polymers as starch or synthetic polymers, such as PLGA. 124 Biodegradable polymeric MPs swell and form a gel-like structure when in contact with an aqueous medium at the mucous membrane. The rate and extent of the drug release are dependent on the polymer itself and its concentration. The main challenges in the formulation of biodegradable polymeric MPs are drug loading efficiency and drug release controlling. 125

Synthetic polymeric MPs were used as drug delivery vehicles in clinical trials due to their safety and biocompatibility. However, they have some limitations, such as their migration tendency away from the injection site, leading to a potential risk of embolism and further organ damage. 126 Wu et al prepared insulin-loaded porous microspheres to control blood glucose levels for at least 18 days. The carrier acquired a unique glucose sensitivity property due to incorporating glucose oxidase, where insulin was released from the delivery system upon elevated blood glucose levels. 115 For example, exenatide, an antidiabetic drug with a short half-life, was loaded into porous MPs to improve its characteristics. It was reported that the prepared exenatide-loaded porous microspheres had a sustained release for 30 days in rat models. 127

Furthermore, rosiglitazone maleate mucoadhesive microspheres were prepared for achieving controlled drug release. The mucoadhesive microsphere tended to adhere to the mucosal tissue for a prolonged period of 12 hours. 128 In another study, polylactic acid MPs were approved as a successful sustained release delivery system of metformin hydrochloride in the treatment of diabetes. The MPs improved the drug bioavailability and overcame the difficulty of oral tablet swallowing, which could be considered a potential alternative to oral pills. 129

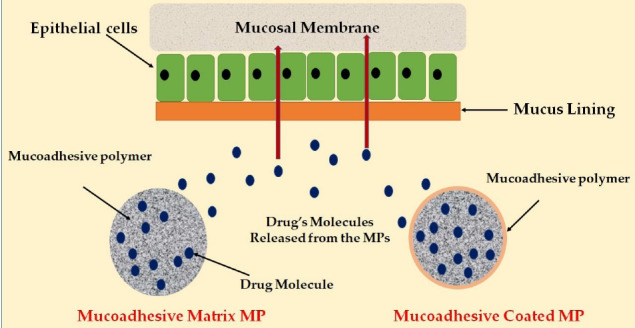

Antidiabetic drugs mucosal delivery

Adhesion describes the sticking and bioadhesion as sticking a drug to the membrane using water-soluble polymers. The mucoadhesive MPs are intrinsically prepared by incorporating a mucoadhesive polymer-based matrix in the formulation or coating the MPs with a mucoadhesive polymer. 130 These MPs have offered several advantages over the conventional formulations, including a prolonged residence time at the application site, controlled drug release, and enhanced drugs permeation and bioavailability. 131 Mucoadhesive MPs may be delivered to different body sites lined with mucous membrane, such as the oral, buccal, ocular, rectal, vaginal, and nasal. Figure 7 displays the mechanism of the drug release from the MPs at the target site of absorption.

Figure 7.

A scheme demonstrates the release of drug’s molecules from the mucoadhesive microparticles at the site of absorption

However, the mucoadhesive efficacy of a dosage form is dependent on various factors, such as the nature of the mucosal tissue and the physicochemical properties of the polymeric formulation. These mucoadhesive agents are typically high molecular weight polymers of high molecular weight and interact with the mucus layer of the mucosa epithelium through hydrogen bonding, ionic, hydrophobic or van der Waals interactions. 132 Table 4 describes several examples of the mucoadhesive MPs on their polymer components, preparation method, administration routes, and aim of the preparation.

Table 4. Examples of antidiabetic drugs-loaded mucoadhesive microparticles .

| API | Delivery system | Polymer(s) | Method of preparation | Route of administration | Aim | Reference |

| Insulin | Hydrogel microparticles | Whey protein/ alginate | Cold gelation technique and an adsorption | Oral | Improvement of intestinal absorption and drug bioavailability | 131 |

| Metformin | Gastroretentive discs | Emulsification, solvent evaporation, and compression | Oral | Gastroprotective formulation to improve therapeutic performance | 132 | |

| Insulin | Microsphere | CP/EC | Spray drying | Nasal |

Non-injectable system for insulin |

133 |

| Insulin | Polyelectrolyte microparticles | Fumaryl diketopiperazine | Aggregation | Oral | Improve bioavailability | 134 |

| Insulin | Hydrogel microparticles | Chitosan and Dextran sulfate | Ionic gelation | Oral | Improve the oral delivery of proteins/peptides | 135 |

| Insulin | Microsphere | Spray drying | Nasal | Improve the systemic absorption | 136 | |

| Insulin | Multicomponent microparticles | PMAA/PEG/chitosan | Layer-by-layer assembly | Oral | Improve bioavailability | 114 |

| Metformin HCl | Microparticle compressed into discs | Chitosan/PVA | Emulsification solvent evaporation | Oral | Controlled drug release and enhancing bioavailability | 88 |

| Insulin | Microspheres | Membrane emulsification | Oral | Improve bioavailability and oral delivery | 137 | |

| Exenatide | Microparticles | Dextran sulfate/Chitosan | Coprecipitation and Micronization | Nasal | Enhanced drugs permeation | 138 |

| Sitagliptin | Microsphere | Carbomer 934P/E.C. | Spray drying | Oral | Controlled drug release | 139 |

| Metformin | Microsphere | Ionic gelation | Oral | Sustained release and enhance absorption | 140 | |

| Repaglinide | Microparticle | Chitosan | Spray drying | Nasal | An alternative route of administration | 141 |

| Glipizide | Microbeads | PAA | Emulsification solvent evaporation | Oral | Prolonged-drug release | 142 |

CP: Carbopol 934; E.C.: Ethylcellulose; PMAA: Polymethacrylic acid; PEG: Polyethylene glycol; PVA: Polyvinyl alcohol; PAA: Polyacrylic acid.

Routes of administration

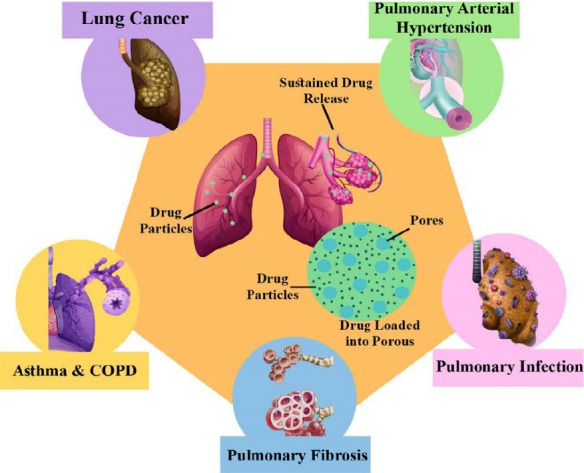

Various options for the administration of antidiabetics were proposed to treat patients with DM. As a result, researchers formulated the antidiabetic drugs-loaded MPs to be delivered in several administration routes for more appropriateness in patients’ perception. For example, the pulmonary route of administration 143 had been used for many decades to deliver drugs for systemic and local applications to treat various respiratory system diseases (Figure 8). Recently, inhaled antidiabetic drugs-loaded MPs have become a highly focused research trend in the pharmaceutical industry. For instance, Rashid et al conducted a study evaluating rosiglitazone-loaded porous microspheres for pulmonary administration. The candidate inhaled formula was non-invasive and successfully released 87% of rosiglitazone within 24 hours. 19

Figure 8.

Pulmonary therapeutic applications and drug targeting of microparticles delivery systems

It is well-known that one of the key factors deciding the drug bioavailability is the residence time at the absorption site. The strategy of using mucoadhesive polymers was employed for this purpose. In a previous study, N-trimethyl chitosan MPs with permeation enhancers were prepared for pulmonary insulin delivery in diabetic rats. Chitosan-based MPs were found pharmacologically efficient and relatively bioavailable compared to subcutaneous administration. The histological examination of the rat’s lung proved the safety of the formula. 144 Hamishehkar et al prepared long‐acting, respirable, biodegradable microcapsules loaded with insulin. The dry powder inhaler formulation was tested on diabetic rats through the pulmonary route. Results showed that the prepared microcapsules had a longer residence time and ability to control blood glucose levels for up to 48 hours. 123

Buccal drug administration was another proposed route for the delivery of the antidiabetic drugs-loaded MPs. The bioadhesive metformin loaded MPs for the oromucosal administration was prepared by Sander et al The prepared formula was tested for its bioadhesive properties using an ex vivo flow retention model. The results indicated improved metformin retention on porcine mucosa, making it the right candidate for the buccal route of administration. 145 Nasal and oral mucoadhesive MPs were the most commonly investigated delivery systems for insulin and oral hypoglycemic drugs. For example, the nasal delivery of insulin-loaded gelatin MPs was investigated in healthy rats. The hypoglycemic effect was assessed for both suspension and dry powder MPs formulations. A significant decrease in blood glucose levels was observed after the dry powder administration. The bioavailability enhancing effect of the mucoadhesive gelatin microspheres was attributed to the long residence time of the MPs at the nasal mucosa besides opening the tight intercellular junctions. 146

Multilayered surface-modified MDDS were suggested for oral insulin delivery. The MPs were prepared via the alternative deposition layer by layer of ferric ions and dextran sulfate at the surface of the microspheres. Insulin hypoglycemic effect was mainly determined by the number of layers and lasted for 12 hours, with ten bilayers deposition. 147 Table 5 displays examples of antidiabetic drugs-loaded polymeric MPs, their component polymer, preparation method, and administration route.

Table 5. Examples of antidiabetic drugs-loaded polymeric microparticles, component polymer, preparation method, and routes of administration .

| Drug Name | Pharmacological class | Polymer(s) | Administration Route | Preparation technique | Reference |

| Liraglutide | GLP-1 analogue | PLGA | Parenteral | W/O/W double emulsion | 148 |

| Exenatide | GLP-1 analogue | PLGA | Parenteral | W/O/W double emulsion | 149 |

| Insulin | Intermediate-acting insulin | PEG-grafted chitosan | Intranasal | Ionotropic gelation | 150 |

| Insulin | Insulins | Sodium alginate/chitosan | Oral | Coacervation phase separation | 137 |

| Metformin | Biguanides | Sodium alginate/chitosan | Oral | Spray-drying | 151 |

| Pioglitazone HCl | Thiazolidinediones | Eudragit RS 100/Eudragit RL 100 | Oral | Solvent evaporation | 152 |

| Glipizide | Sulfonylureas | Eudragit RS 100 -RL 100 | Oral | Emulsion crosslinking | 153 |

| Glipizide | Sulfonylureas | Galactomannan gum | Oral | Emulsion crosslinking | 154 |

| Tolbutamide | Sulfonylureas | Alginate and xanthan gum | Oral | Orifice-ionic gelation and emulsification gelation | 155 |

| Gliclazide | Sulfonylureas | Tamarind seed polysaccharide/alginate | Oral | Ionotropic gelation | 156 |

| Insulin | Insulins | PLA | Oral | Emulsion-solvent evaporation | 157 |

| Insulin | Insulins | Chitosan/PVP | Intranasal | Spray drying | 136 |

| Insulin | Insulins | Sodium alginate | Oral | Spray drying | 158 |

| Insulin | Insulins | Quaternized chitosan | Oral | Emulsification and crosslinking | 159 |

PLGA: Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid); GLP-1: Glucagon-like peptide-1; PEG: Polyethylene glycol; PLA: Poly9lactic acid); PVP: Polyvinyl Alcohol; SPG: Shirasu-porous-glass; W/O/W: Water-in-Oil-in-Water.

Current status and future developments

Despite the global evolution in developing innovative microparticulate systems for the delivery of antidiabetic drugs, there are still numerous challenges due to the wide variations in drug loading, particles characteristics, and manufacturing processes. Therefore, there are few antidiabetic MPs-based products currently available in the market. For example, Bydureon® is a sustained-release injection in a pre-filled pen containing exenatide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, for subcutaneous administration. This depot is produced by AstraZeneca U.K. Limited using microspheres technology, where the drug particles are loaded into PLGA based microspheres. This medication helps to control blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetic patients. 24

Furthermore, to reflect the current status and future developments in this field, relevant patents published on Google Patent.com were also reviewed. Table 6 shows examples of patents/innovations (from year 2000 onwards) of antidiabetic drugs-loaded MPs related to patent applications.

Table 6. Patents-innovations (2000 onward) related to antidiabetic drugs loaded microparticles .

| Patent number | Title | API | References |

| US20040234615A1 | Oral insulin composition and methods of making and using thereof | Insulin | 160 |

| WO2005092301A1 | Insulin highly respirable microparticles | Insulin | 161 |

| US6444226B1 | Purification and stabilization of peptide and protein pharmaceutical agents | Insulin | 162 |

| US20100055194A1 | Pharmaceutical formulations containing microparticles or nanoparticles of a delivery agent | Insulin | 163 |

| WO2013115746A1 | A production method for (effervescent) pharmaceutical compositions comprising an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor (Miglitol) and metformin | Metformin/Miglitol | 164 |

| CN102085355A | Liraglutide long-acting microsphere injection and preparation method thereof | Liraglutide | 165 |

| WO2017107906A1 | Exenatide microsphere preparation and preparation method thereof | Exenatide | 166 |

| CN101658496A | Exenatide release microsphere preparation, preparation method and application thereof | Exenatide | 167 |

| EP2814460B1 | Glucose-responsive microgels for closed-loop insulin delivery | Insulin | 168 |

| WO2015166472A1 | Extended-release liquid compositions of metformin | Metformin | 169 |

| CN106176623A | Metformin hydrochloride PLGA microsphere and its preparation method and application | Metformin | 170 |

| JP2004501188A | Controlled release formulation of insulin and method thereof | Insulin | 171 |

| US20120121707A1 | Tolbutamide particle and preparing method thereof and method of reducing a blood glucose | Tolbutamide | 172 |

| WO2008062470A2 | Stabilized controlled release dosage form of gliclazide | Gliclazide | 173 |

| WO2014128116A1 | A production process for gliclazide formulations | Gliclazide | 174 |

Conclusion

MDDS offer several merits over traditional pharmaceutical dosage forms, such as increasing efficacy, reducing toxicity, and improving patient compliance and comfort. Several methods are used for MPs preparations such as single emulsion, double emulsion, spray drying, solvent extraction, and phase separation coacervation technique. The content and physical state of the drug; polymer’s nature, molecular weight, and concentration; and type of excipients used are the main factors affecting the drug release profile from the MPs. Diabetes is considered a global disease; nevertheless, research and development in drug delivery and disease management are ongoing to improve drugs efficacy and safety. Antidiabetics-laden MPs were created for their unique applications in targeting drugs to a specific site in the body, improving drug dissolution, controlling drug release, reducing side effects, and enhancing bioavailability and stability. The interest in applying MDDS for the treatment of diabetes for administration via different routes is currently increasing. Through the combination of different strategies, the MPs can be effectively placed and used, particularly in cell sorting, diagnosis, genetics, and biological products.

Ethical Issues

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in this paper.

References

- 1.Mahale M, Saudagar R. Microsphere: a review. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2019;9(3 Suppl):854–6. doi: 10.22270/jddt.v9i3-s.2826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavali KV, Kengar MD, Chavan KV, Anekar VP, Khan NI. A review on microsphere and it’s application. Asian J Pharm Res. 2019;9(2):123–9. doi: 10.5958/2231-5691.2019.00020.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song R, Murphy M, Li C, Ting K, Soo C, Zheng Z. Current development of biodegradable polymeric materials for biomedical applications. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:3117–45. doi: 10.2147/dddt.s165440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lengyel M, Kállai-Szabó N, Antal V, Laki AJ, Antal I. Microparticles, microspheres, and microcapsules for advanced drug delivery. Sci Pharm. 2019;87(3):20. doi: 10.3390/scipharm87030020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bale S, Khurana A, Reddy AS, Singh M, Godugu C. Overview on therapeutic applications of microparticulate drug delivery systems. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2016;33(4):309–61. doi: 10.1615/CritRevTherDrugCarrierSyst.2016015798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh MN, Hemant KS, Ram M, Shivakumar HG. Microencapsulation: a promising technique for controlled drug delivery. Res Pharm Sci. 2010;5(2):65–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Say KM. Maximizing the encapsulation efficiency and the bioavailability of controlled-release cetirizine microspheres using Draper-Lin small composite design. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:825–39. doi: 10.2147/dddt.s101900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morita T, Horikiri Y, Suzuki T, Yoshino H. Preparation of gelatin microparticles by co-lyophilization with poly(ethylene glycol): characterization and application to entrapment into biodegradable microspheres. Int J Pharm. 2001;219(1-2):127–37. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Popelka A, Zavahir S, Habib S. Morphology analysis. In: AlMaadeed MA, Ponnamma D, Carignano MA, eds. Polymer Science and Innovative Applications. USA: Elsevier; 2020. p. 21-68. 10.1016/b978-0-12-816808-0.00002-0. [DOI]

- 10. Kasalkova NS, Slepicka P, Kolska Z, Svorcik V. Wettability and other surface properties of modified polymers. In: Aliofkhazraei M, ed. Wetting and Wettability. IntechOpen; 2015. 10.5772/60824. [DOI]

- 11.Cheng W, Dunn PF, Brach RM. Surface roughness effects onmicroparticle adhesion. J Adhes. 2002;78(11):929–65. doi: 10.1080/00218460214510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu GW, Gao P. Emulsions and microemulsions for topical and transdermal drug delivery. In: Kulkarni VS, ed. Handbook of Non-Invasive Drug Delivery Systems. Boston: William Andrew Publishing; 2010. p. 59-94. 10.1016/b978-0-8155-2025-2.10003-4. [DOI]

- 13.Oliveira PM, Matos BN, Pereira PAT, Gratieri T, Faccioli LH, Cunha-Filho MSS, et al. Microparticles prepared with 50-190kDa chitosan as promising non-toxic carriers for pulmonary delivery of isoniazid. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;174:421–31. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siafaka PI, Cağlar EŞ, Papadopoulou K, Tsanaktsis V, Karantas ID, Üstündağ Okur N, et al. Polymeric microparticles as alternative carriers for antidiabetic glibenclamide drug. Pharm Biomed Res. 2019;5(4):27–34. doi: 10.18502/pbr.v5i4.2394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarfraz RM, Ahmad M, Mahmood A, Minhas MU, Yaqoob A. Development and evaluation of rosuvastatin calcium based microparticles for solubility enhancement: an in vitro study. Adv Polym Technol. 2017;36(4):433–41. doi: 10.1002/adv.21625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Situ W, Chen L, Wang X, Li X. Resistant starch film-coated microparticles for an oral colon-specific polypeptide delivery system and its release behaviors. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(16):3599–609. doi: 10.1021/jf500472b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meerovich I, Smith DD, Dash AK. Direct solid-phase peptide synthesis on chitosan microparticles for targeting tumor cells. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2019;54:101288. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ripoll L, Clement Y. Polyamide microparticles containing vitamin C by interfacial polymerization: an approach by design of experimentation. Cosmetics. 2016;3(4):38. doi: 10.3390/cosmetics3040038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rashid J, Alobaida A, Al-Hilal TA, Hammouda S, McMurtry IF, Nozik-Grayck E, et al. Repurposing rosiglitazone, a PPAR-γ agonist and oral antidiabetic, as an inhaled formulation, for the treatment of PAH. J Control Release. 2018;280:113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Micro-K (Potassium Chloride Extended-Release): Uses, Dosage, Side Effects, Interactions, Warning. RxList. https://www.rxlist.com/micro-k-drug.htm#description. Accessed July 5, 2021.

- 21. Cotazym (Pancrelipase). MedBroadcast. https://www.rxmed.com/b.main/b2.pharmaceutical/b2.1.monographs/cps-_monographs/CPS-_(General_Monographs-_C)/COTAZYM.html. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- 22. Lupron Depot 3.75 mg (Leuprolide Acetate for Depot Suspension). Highlights of Prescribing Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/020517s036_019732s041lbl.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2021.

- 23. Nutropin Depot. RxList. https://www.rxlist.com/nutropin-depot-drug.htm. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- 24. Sandostatin LAR Depot. NOVARTIS. https://www.rxlist.com/sandostatin-lar-drug.htm. Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 25. Trelstar. https://www.rxlist.com/trelstar-drug.htm. Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 26. Vivitrol. https://www.rxlist.com/vivitrol-drug.htm. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- 27. Decapeptyl SR 11.25mg (triptorelin pamoate). https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/780/smpc#gref. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- 28. Risperdal Consta. https://www.rxlist.com/risperdal-consta-drug.htm#indications. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- 29. Bydureon. https://www.rxlist.com/bydureon-drug.htm#description. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- 30. Signifor-LAR. https://www.rxlist.com/signifor-lar-drug.htm. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- 31.Misra P, Upadhyay RP, Misra A, Anand K. A review of the epidemiology of diabetes in rural India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;92(3):303–11. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fox CS, Pencina MJ, Wilson PW, Paynter NP, Vasan RS, D’Agostino RB, Sr Sr. Lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease among individuals with and without diabetes stratified by obesity status in the Framingham heart study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1582–4. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Management of Diabetes Federal Bureau of Prisons Clinical Practice Guidelines. http://www.bop.gov/news/medresources.jsp. Accessed March 9, 2021.

- 34. International Diabetes Federation (2013) IDF Diabetes Atlas. 6th Edition, International Diabetes Federation, Brussels. Neuroscience and Medicine. 2013. https://www.scirp.org/(S(i43dyn45teexjx455qlt3d2q))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1559405. Accessed March 9, 2021.

- 35.Shrestha JT, Shrestha H, Prajapati M, Karkee A, Maharjan A. Adverse effects of oral hypoglycemic agents and adherence to them among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Nepal. J Lumbini Med Coll. 2017;5(1):34–40. doi: 10.22502/jlmc.v5i1.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rai VK, Mishra N, Agrawal AK, Jain S, Yadav NP. Novel drug delivery system: an immense hope for diabetics. Drug Deliv. 2016;23(7):2371–90. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.991001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma VK, Mazumder B. Gastrointestinal transition and anti-diabetic effect of Isabgol husk microparticles containing gliclazide. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014;66:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong CY, Al-Salami H, Dass CR. Microparticles, microcapsules and microspheres: a review of recent developments and prospects for oral delivery of insulin. Int J Pharm. 2018;537(1-2):223–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choudhury PK, Kar M. Controlled release metformin hydrochloride microspheres of ethyl cellulose prepared by different methods and study on the polymer affected parameters. J Microencapsul. 2009;26(1):46–53. doi: 10.1080/02652040802130503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mumuni MA, Kenechukwu FC, Ernest OC, Oluseun AM, Abdulmumin B, Youngson DC, et al. Surface-modified mucoadhesive microparticles as a controlled release system for oral delivery of insulin. Heliyon. 2019;5(9):e02366. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma M, Kohli S, Dinda A. In-vitro and in-vivo evaluation of repaglinide loaded floating microspheres prepared from different viscosity grades of HPMC polymer. Saudi Pharm J. 2015;23(6):675–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ni R, Muenster U, Zhao J, Zhang L, Becker-Pelster EM, Rosenbruch M, et al. Exploring polyvinylpyrrolidone in the engineering of large porous PLGA microparticles via single emulsion method with tunable sustained release in the lung: in vitro and in vivo characterization. J Control Release. 2017;249:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Wang J, Qiao F, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Li M, et al. Polymeric non-spherical coarse microparticles fabricated by double emulsion-solvent evaporation for simvastatin delivery. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2021;199:111560. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.111560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deshmukh R, Wagh P, Naik J. Solvent evaporation and spray drying technique for micro- and nanospheres/particles preparation: a review. Dry Technol. 2016;34(15):1758–72. doi: 10.1080/07373937.2016.1232271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grizić D, Lamprecht A. Microparticle preparation by a propylene carbonate emulsification-extraction method. Int J Pharm. 2018;544(1):213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Nimry SS, Khanfar MS. Preparation and characterization of lovastatin polymeric microparticles by coacervation-phase separation method for dissolution enhancement. J Appl Polym Sci. 2016;133(14) doi: 10.1002/app.43277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dey S, Pramanik S, Malgope A. Formulation and optimization of sustained release stavudine microspheres using response surface methodology. ISRN Pharm. 2011;2011:627623. doi: 10.5402/2011/627623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeap EWQ, Ng DZL, Prhashanna A, Somasundar A, Acevedo AJ, Xu Q, et al. Bottom-up structural design of crystalline drug-excipient composite microparticles via microfluidic droplet-based processing. Cryst Growth Des. 2017;17(6):3030–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.6b01701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim KK, Pack DW. Microspheres for drug delivery. In: Ferrari M, Lee AP, Lee LJ, eds. BioMEMS and Biomedical Nanotechnology. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2006. p. 19-50. 10.1007/978-0-387-25842-3_2. [DOI]

- 50.Tabata Y, Langer R. Polyanhydride microspheres that display near-constant release of water-soluble model drug compounds. Pharm Res. 1993;10(3):391–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1018988222324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y, Zhang R, Illangakoon UE, Harker AH, Thrasivoulou C, Parhizkar M, et al. Copolymer composition and nanoparticle configuration enhance in vitro drug release behavior of poorly water-soluble progesterone for oral formulations. Int J Nanomedicine. 2020;15:5389–403. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s257353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang YY, Chung TS, Ng NP. Morphology, drug distribution, and in vitro release profiles of biodegradable polymeric microspheres containing protein fabricated by double-emulsion solvent extraction/evaporation method. Biomaterials. 2001;22(3):231–41. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jain RA, Rhodes CT, Railkar AM, Malick AW, Shah NH. Controlled release of drugs from injectable in situ formed biodegradable PLGA microspheres: effect of various formulation variables. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50(2):257–62. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han FY, Thurecht KJ, Whittaker AK, Smith MT. Bioerodable PLGA-based microparticles for producing sustained-release drug formulations and strategies for improving drug loading. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:185. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia Y, Pack DW. Uniform biodegradable microparticle systems for controlled release. Chem Eng Sci. 2015;125:129–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2014.06.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen W, Palazzo A, Hennink WE, Kok RJ. Effect of particle size on drug loading and release kinetics of gefitinib-loaded PLGA microspheres. Mol Pharm. 2017;14(2):459–67. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shaikh R, Raj Singh TR, Garland MJ, Woolfson AD, Donnelly RF. Mucoadhesive drug delivery systems. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3(1):89–100. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.76478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rizwan M, Yahya R, Hassan A, Yar M, Azzahari AD, Selvanathan V, et al. pH sensitive hydrogels in drug delivery: brief history, properties, swelling, and release mechanism, material selection and applications. Polymers (Basel) 2017;9(4):137. doi: 10.3390/polym9040137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC. Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev. 2016;116(4):2602–63. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rossi S, Ferrari F, Bonferoni MC, Caramella C. Characterization of chitosan hydrochloride--mucin rheological interaction: influence of polymer concentration and polymer: mucin weight ratio. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;12(4):479–85. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(00)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bowey K, Neufeld RJ. Systemic and mucosal delivery of drugs within polymeric microparticles produced by spray drying. BioDrugs. 2010;24(6):359–77. doi: 10.2165/11539070-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abdul Rasool BK, Khalifa A, Abu-Gharbieh E, Khan R. Employment of alginate floating in situ gel for controlled delivery of celecoxib: solubilization and formulation studies. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1879125. doi: 10.1155/2020/1879125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mohan Kamila M, Mondal N, Kanta Ghosh L, Kumar Gupta B. Multiunit floating drug delivery system of rosiglitazone maleate: development, characterization, statistical optimization of drug release and in vivo evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2009;10(3):887–99. doi: 10.1208/s12249-009-9276-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Awasthi R, Kulkarni GT. Development of novel gastroretentive floating particulate drug delivery system of gliclazide. Curr Drug Deliv. 2012;9(5):437–51. doi: 10.2174/156720112802650716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sah SK, Tiwari A, Shrivastava B. Formulation optimization and in-vivo evaluation of floating gastroretentive microsphere of sitagliptin by 32 factorial design. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2016;40(2):198–206. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boldhane SP, Kuchekar BS. Gastroretentive drug delivery of metformin hydrochloride: formulation and in vitro evaluation using 3(2) full factorial design. Curr Drug Deliv. 2009;6(5):477–85. doi: 10.2174/156720109789941641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Choudhury PK, Kar M, Chauhan CS. Cellulose acetate microspheres as floating depot systems to increase gastric retention of antidiabetic drug: formulation, characterization and in vitro-in vivo evaluation. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2008;34(4):349–54. doi: 10.1080/03639040701542531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thulluru A, Mohan Varma M, Setty CM, Anusha A, Chamundeeswari P, Sanufar S. Formulation, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of pioglitazone hydrochloride-effervescent gastro retentive floating hydrophilic matrix tablets. Int J PharmTech Res. 2016;9(7):388–98. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duggi S, Narendra Chary T. Studies on formulation development of gastroretentive drug delivery system for pioglitazone hydrochloride. Int J Pharm. 2014;4(3):241–54. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Senjoti FG, Mahmood S, Jaffri JM, Mandal UK. Design and in-vitro evaluation of sustained release floating tablets of metformin HCl based on effervescence and swelling. Iran J Pharm Res. 2016;15(1):53–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raju DB, Sreenivas R, Varma MM. Formulation and evaluation of floating drug delivery system of metformin hydrochloride. J Chem Pharm Res. 2010;2(2):274–8. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kavitha K, Puneeth KP, Mani TT. Development and evaluation of rosiglitazone maleate floating tablets using natural gums. Int J PharmTech Res. 2010;2(3):1662–9. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jeganath S, Shafiq K, Mahesh P, Kumar S. Formulation and evaluation of non-effervescent floating tablets of linagliptin using low-density carriers. Drug Invent Today. 2018;10(3):322–9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mahmoud D, Shukr MH, ElMeshad AN. Gastroretentive Microsponge as a Promising Tool for Prolonging the Release of Mitiglinide Calcium in Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus: Optimization and Pharmacokinetics Study. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2018;19(6):2519–32. doi: 10.1208/s12249-018-1081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yadav A, Jain DK. Gastroretentive microballoons of metformin: Formulation development and characterization. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2011;2(1):51–5. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.79806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Patel A, Ray S, Thakur RS. In vitro evaluation and optimization of controlled release floating drug delivery system of metformin hydrochloride. Daru J Pharm Sci. 2006;14(2):57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rao MR, Borate SG, Thanki KC, Ranpise AA, Parikh GN. Development and in vitro evaluation of floating rosiglitazone maleate microspheres. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2009;35(7):834–42. doi: 10.1080/03639040802627421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sarkar D, Nandi G, Changder A, Hudati P, Sarkar S, Ghosh LK. Sustained release gastroretentive tablet of metformin hydrochloride based on poly (acrylic acid)-grafted-gellan. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;96:137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Development and evaluation of mucoadhesive microcapsules of rosiglitazone. Kongposh Publications. https://www.kppub.com/articles/may2009/development_and_evaluation.html. Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 80.Vaghani SS, Patel SG, Jivani RR, Jivani NP, Patel MM, Borda R. Design and optimization of a stomach-specific drug delivery system of repaglinide: application of simplex lattice design. Pharm Dev Technol. 2012;17(1):55–65. doi: 10.3109/10837450.2010.513988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prasanthi D, Deepika Y, Rama Devi S. Formulation and evaluation of linagliptin mucoadhesive microspheres. Int Res J Pharm. 2018;9(5):11–7. doi: 10.7897/2230-8407.09567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chowdary KP, Rao YS. Design and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of mucoadhesive microcapsules of glipizide for oral controlled release: a technical note. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2003;4(3):E39. doi: 10.1208/pt040339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mahmoud DB, Shukr MH, ElMeshad AN. Gastroretentive cosolvent-based in situ gel as a promising approach for simultaneous extended delivery and enhanced bioavailability of mitiglinide calcium. J Pharm Sci. 2019;108(2):897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2018.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vishal Gupta N, Shivakumar HG. Preparation and characterization of superporous hydrogels as gastroretentive drug delivery system for rosiglitazone maleate. Daru. 2010;18(3):200–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jain AK, Sahu P, Mishra K, Jain SK. Repaglinide and metformin-loaded amberlite resin-based floating microspheres for the effective management of type 2 diabetes. Curr Drug Deliv. 2021;18(5):654–68. doi: 10.2174/1567201817666201026105611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jain SK, Agrawal GP, Jain NK. A novel calcium silicate based microspheres of repaglinide: in vivo investigations. J Control Release. 2006;113(2):111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dubey M, Kesharwani P, Tiwari A, Chandel R, Raja K, Sivakumar T. Formulation and evaluation of floating microsphere containing anti diabetic drug. Int J Pharm Chem Sci. 2012;1(3):1038–47. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Khonsari F, Zakeri-Milani P, Jelvehgari M. Formulation and evaluation of in-vitro characterization of gastic-mucoadhesive microparticles/discs containing metformin hydrochloride. Iran J Pharm Res. 2014;13(1):67–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shams T, Brako F, Huo S, Harker AH, Edirisinghe U, Edirisinghe M. The influence of drug solubility and sampling frequency on metformin and glibenclamide release from double-layered particles: experimental analysis and mathematical modelling. J R Soc Interface. 2019;16(155):20190237. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2019.0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nnamani PO, Attama AA, Ibezim EC, Adikwu MU. SRMS142-based solid lipid microparticles: application in oral delivery of glibenclamide to diabetic rats. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2010;76(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tzankov B, Voycheva C, Aluani D, Yordanov Y, Avramova K, Tzankova V, et al. Improvement of dissolution of poorly soluble glimepiride by loading on two types of mesoporous silica carriers. J Solid State Chem. 2019;271:253–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jssc.2018.12.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pawar R, Shinde SV, Deshmukh S. Solubility enhancement of pioglitazone by spray drying techniques using hydrophilic carriers. J Pharm Res. 2012;5(5):2500–4. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kadiyala I, Tan E. Formulation approaches in mitigating toxicity of orally administrated drugs. Pharm Dev Technol. 2013;18(2):305–12. doi: 10.3109/10837450.2012.734516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Volpatti LR, Facklam AL, Cortinas AB, Lu YC, Matranga MA, MacIsaac C, et al. Microgel encapsulated nanoparticles for glucose-responsive insulin delivery. Biomaterials. 2021;267:120458. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meena KP, Vijayakumar MR, Dwibedy PS. Catechin-loaded eudragit microparticles for the management of diabetes: formulation, characterization and in vivo evaluation of antidiabetic efficacy. J Microencapsul. 2017;34(4):342–50. doi: 10.1080/02652048.2017.1337248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Repaglinide tablet. DailyMed. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=8e4d76bf-8387-4dc1-b08b-aef6890ec92b. Accessed June 11, 2021.

- 97.Maji R, Ray S, Das B, Nayak AK. Ethyl cellulose microparticles containing metformin HCl by emulsification-solvent evaporation technique: effect of formulation variables. Int Sch Res Notices. 2012;2012:801827. doi: 10.5402/2012/801827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Farah Ahmed FH. Magnetic microspheres: a novel drug delivery system. J Anal Pharm Res. 2016;3(4):1–2. doi: 10.15406/japlr.2016.03.00067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.El-Boubbou K, Ali R, Al-Zahrani H, Trivilegio T, Alanazi AH, Khan AL, et al. Preparation of iron oxide mesoporous magnetic microparticles as novel multidrug carriers for synergistic anticancer therapy and deep tumor penetration. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):9481. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wu LC, Zhang Y, Steinberg G, Qu H, Huang S, Cheng M, et al. A review of magnetic particle imaging and perspectives on neuroimaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2019;40(2):206–12. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kost J, Noecker R, Kunica E, Langer R. Magnetically controlled release systems: effect of polymer composition. J Biomed Mater Res. 1985;19(8):935–40. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820190805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cheng J, Teply BA, Jeong SY, Yim CH, Ho D, Sherifi I, et al. Magnetically responsive polymeric microparticles for oral delivery of protein drugs. Pharm Res. 2006;23(3):557–64. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-9444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Teply BA, Tong R, Jeong SY, Luther G, Sherifi I, Yim CH, et al. The use of charge-coupled polymeric microparticles and micromagnets for modulating the bioavailability of orally delivered macromolecules. Biomaterials. 2008;29(9):1216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Finotelli PV, Da Silva D, Sola-Penna M, Rossi AM, Farina M, Andrade LR, et al. Microcapsules of alginate/chitosan containing magnetic nanoparticles for controlled release of insulin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2010;81(1):206–11. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Situ W, Li X, Liu J, Chen L. Preparation and characterization of glycoprotein-resistant starch complex as a coating material for oral bioadhesive microparticles for colon-targeted polypeptide delivery. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63(16):4138–47. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mathavan S, Chen-Tan N, Arfuso F, Al-Salami H. The role of the bile acid chenodeoxycholic acid in the targeted oral delivery of the anti-diabetic drug gliclazide, and its applications in type 1 diabetes. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2016;44(6):1508–19. doi: 10.3109/21691401.2015.1058807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mooranian A, Negrulj R, Al-Sallami HS, Fang Z, Mikov M, Golocorbin-Kon S, et al. Release and swelling studies of an innovative antidiabetic-bile acid microencapsulated formulation, as a novel targeted therapy for diabetes treatment. J Microencapsul. 2015;32(2):151–6. doi: 10.3109/02652048.2014.958204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Leong KH, Chung LY, Noordin MI, Onuki Y, Morishita M, Takayama K. Lectin-functionalized carboxymethylated kappa-carrageenan microparticles for oral insulin delivery. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;86(2):555–65. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.04.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sajeesh S, Bouchemal K, Marsaud V, Vauthier C, Sharma CP. Cyclodextrin complexed insulin encapsulated hydrogel microparticles: an oral delivery system for insulin. J Control Release. 2010;147(3):377–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yang Y, Liu Y, Chen S, Cheong KL, Teng B. Carboxymethyl β-cyclodextrin grafted carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogel-based microparticles for oral insulin delivery. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;246:116617. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Builders PF, Kunle OO, Okpaku LC, Builders MI, Attama AA, Adikwu MU. Preparation and evaluation of mucinated sodium alginate microparticles for oral delivery of insulin. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;70(3):777–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Xing X, Zhao X, Ding J, Liu D, Qi G. Enteric-coated insulin microparticles delivered by lipopeptides of iturin and surfactin. Drug Deliv. 2018;25(1):23–34. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2017.1413443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Xie Y, Jiang S, Xia F, Hu X, He H, Yin Z, et al. Glucan microparticles thickened with thermosensitive gels as potential carriers for oral delivery of insulin. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4(22):4040–8. doi: 10.1039/c6tb00237d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Balabushevich NG, Pechenkin MA, Shibanova ED, Volodkin DV, Mikhalchik EV. Multifunctional polyelectrolyte microparticles for oral insulin delivery. Macromol Biosci. 2013;13(10):1379–88. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wu JZ, Williams GR, Li HY, Wang DX, Li SD, Zhu LM. Insulin-loaded PLGA microspheres for glucose-responsive release. Drug Deliv. 2017;24(1):1513–25. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2017.1381200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shrestha N, Shahbazi MA, Araújo F, Zhang H, Mäkilä EM, Kauppila J, et al. Chitosan-modified porous silicon microparticles for enhanced permeability of insulin across intestinal cell monolayers. Biomaterials. 2014;35(25):7172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chime SA, Onyishi IV, Ugwoke PU, Attama AA. Evaluation of the properties of Gongronema latifolium in phospholipon 90H based solid lipid microparticles (SLMs): an antidiabetic study. J Diet Suppl. 2014;11(1):7–18. doi: 10.3109/19390211.2013.859212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]