Abstract

Activation of a telomere maintenance mechanism is key to achieving replicative immortality. Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT) is a telomerase-independent pathway that hijacks the homologous recombination pathways to elongate telomeres. Commitment to ALT is often associated with several hallmarks including long telomeres of heterogenous lengths, mutations in histone H3.3 or the ATRX/DAXX histone chaperone complex, and incorporation of non-canonical telomere sequences. The consequences of these genetic and epigenetic changes include enhanced replication stress and the presence of transcriptionally permissive chromatin, which can result in replication-associated DNA damage. Here, we detail the molecular mechanisms that are critical to repairing DNA damage at ALT telomeres, including the BLM Helicase, which acts at several steps in the ALT process. Furthermore, we discuss the emerging findings related to the telomere-associated RNA, TERRA, and its roles in maintaining telomeric integrity. Finally, we review new evidence for therapeutic interventions for ALT-positive cancers which are rooted in understanding the molecular underpinnings of this process.

Keywords: Telomere, ALT, TERRA, Chromatin, Cancer

1. Introduction

Telomeres are protective structures that cap the ends of linear chromosomes and are comprised of TTAGGG repeats bound by a six-subunit protein complex, termed Shelterin [1]. The Shelterin complex facilitates the formation of a T-loop to guard against DNA repair protein activity and prevent chromosome end fusions. However, due to the end-replication problem, telomeres in somatic cells shorten at a steady rate with every cell division and represent an intrinsic clock that regulates the replicative lifespan of the cell. Once telomeres shorten beyond the “Hayflick Limit”, they can induce cell cycle arrest i.e., senescence, to protect from neoplastic transformation. However, mutations that inactivate checkpoint proteins can restart the cell cycle despite the presence of critically short telomeres. Such unchecked proliferation often leads to cell death due to mitotic errors or engagement of an autophagy-driven mechanism that eradicates potentially tumorigenic cells [2]. However, cells can activate a telomere maintenance mechanism and escape cellular crisis. The primary pathway of telomere maintenance involves the reactivation of TERT, the catalytic component of the telomerase reverse transcriptase holoenzyme [3]. Telomerase can then add telomeric repeats to critically short telomeres to promote faithful cellular division and sustained viability. However, some cells activate a TERT-independent pathway involving homologous recombination (HR) pathways that coordinate and mediate telomere extension that sustains their survival and proliferation. This pathway was subsequently named Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres (ALT) [4].

2. ALT origins: re-laying the foundations of telomeric chromatin

The origin of ALT has been mysterious. Perhaps the simplest consideration of when, why, and how of ALT activation is simply to view it as an adaptive response to failing to re-activate telomerase. Indeed, type-I/II survivor ALT yeast strains were largely derived from telomerase mutant yeast strains [5]. ALT-like telomere maintenance was also observed in late-generation telomerase deficient mouse cells [6]. Along these lines, comparative transcriptomics revealed a TERT repression gene expression signature in ALT cancer cells derived from mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) derived lineages [7]. However, genetic aberrations in chromatin modifiers have emerged as a common feature of human cancer cells in which ALT is active. The most predominant alterations are inactivating mutations in the α-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX) and death-domain-associated protein (DAXX) histone H3.3 chaperone complex [8]. ATRX and DAXX form a multifunctional complex that in addition to H3.3 deposition at telomeres [9,10], and other GC-rich chromosomal domains, regulates transcription of specific gene groups like imprinted and zinc finger (ZnF) genes and genes on the inactive X-chromosome [11–14]. ATRX-DAXX is also involved in genome maintenance through its purported helicase activity that mitigates the formation of non-B-form DNA structures like G-quadruplexes and RNA: DNA hybrids termed R-loops [13,15].

The range of mutations in ATRX and DAXX in cancer is extensive [16]. The most prevalent ATRX mutations are missense or truncating mutations [17], but many other mutations that also inactivate these proteins have been detected in cancer genome sequencing [16,17]. There has been considerable debate as to whether ATRX mutations are predictive of ALT [18]. ATRX mutations are detected in melanoma that do not activate ALT. These tumors up-regulate telomerase through TERT promoter mutations (TPMs) or trans-activation of TERT expression [19]. TERT reactivation might occur earlier during tumorigenesis and thus suppress the selective pressures that lead to ALT. Consistent with this, ATRX-DAXX loss and ALT activation tend to be rare in primary tumors and more frequently detected in latent developing and relapsed meta-static tumors [20–23]. Furthermore, there are a significant number of ALT tumors with wild-type ATRX suggesting other pathways of ALT acquisition. However, cancer proteomics studies uncovered several such ALT tumors where ATRX or DAXX protein levels were drastically reduced implying that epigenetic mechanisms might regulate ATRX and DAXX expression and contribute to ALT activation [24]. ATRX and DAXX mutations are mutually exclusive and present in distinct tumor subtypes and categories [8,16]. For example, ATRX inactivation and ALT are more prevalent in grade II astrocytoma brain tumors. In contrast, DAXX mutations are frequent in advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine (PanNETs) [8]. DAXX also forms a secondary chromatin modifier/histone deposition complex by partnering with SETDB1 and KAP1 to deposit H3.3 at endogenous retroviral elements (ERVs) scattered throughout the non-coding genome [25,26]. Thus, DAXX inactivation creates a unique scenario that inactivates two distinct chromatin regulatory complexes which surely has repercussions for the etiology and pathogenicity of those ALT tumors.

Both ATRX-DAXX and DAXX-SETDB1-KAP1 complexes are associated with H3.3 deposition and heterochromatin-dependent silencing [9, 25,26]. Accordingly, targeted disruption of either ATRX or DAXX results in chromatin decompaction and loss of heterochromatin-associated histone modifications (e.g., H3K9me3) at telomeres and ALT activation [27]. Similarly, disrupting Anti-Silencing factor 1a and 1b (ASF1a-b) histone H3 chaperones, and thereby chromatin assembly, could provoke ALT in otherwise non-ALT human cell lines [28]. These findings point to defects in chromatin assembly and histone H3.3 deposition at telomere as a cause of ALT activation. Indeed, ATRX-DAXX inactivation and ASF1a-b depletion caused replicative stress that would be repaired through homology-directed repair mechanisms. Accordingly, the re-expression of ATRX or DAXX proteins in ALT cancer cell lines can suppress replication stress and restore histone H3.3 levels at telomeres [29,30]. Thus, there is ample evidence that ATRX and DAXX loss is an important factor that causes or leads to ALT.

More nuanced, but nonetheless significant, alterations in telomeric chromatin also contribute to ALT activation. Where the targeted disruption of ATRX or DAXX is not sufficient to lead to ALT in cancer cell types, other factors or conditions are required [31,32]. In glioma, ATRX inactivation and ALT frequently coincide with mutations in IDH1 (IDH1-R132H) that cause the production of the oncometabolite D2-hydroxyglutarate that inhibits DNA and histone demethylases [31, 33,34]. Mutations in SETD2 and MEN1 chromatin modifiers have also been identified in PanNETs [22,35]. Pediatric brain tumors like diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) harbor ‘onco-histone’ H3.3 mutations that frequently coincide with ATRX loss and ALT [36,37]. K27M, K36M and G34R/V onco-histone mutations cause systemic changes in chromatin modification by re-directing histone lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) like EZH2 and SETD2 or histone lysine demethylases (KDM) from modifying these or adjacent lysines [38]. One recent study reported that 100% of glioma with H3.3G34R onco-histone mutation, which prevents H3.3K36 methylation, showed the ALT phenotype [39]. Another study using an ATRX-p53-TERT null mouse embryonic stem cell model showed that the H3.3G34R mutation was necessary for ALT acquisition [32]. H3.3G34R deregulates the activity of KDM4B, which not only demethylates H3K36 but also H3K9, the major lysine targeted during heterochromatin formation. Intriguingly, overexpression of KDM4B which would remove H3K9 methylation and thereby heterochromatin at telomeric chromatin was shown to suppress ALT. This discovery joins others suggesting that deregulated H3K9 methylation, or mechanisms driven by the SETDB1 lysine methyltransferase lead to the formation of atypical heterochromatin at telomeres, is important in either activating or maintaining ALT in ATRX-mutated cells [40]. Together, these findings indicate that the alterations in chromatin assembly and the epigenetic landscape at telomeres may facilitate ALT induction or maintenance. Taken together, these studies strongly implicate chromatin mismanagement in creating the conditions necessary for ALT to be activated.

3. Features and Mechanisms of ALT

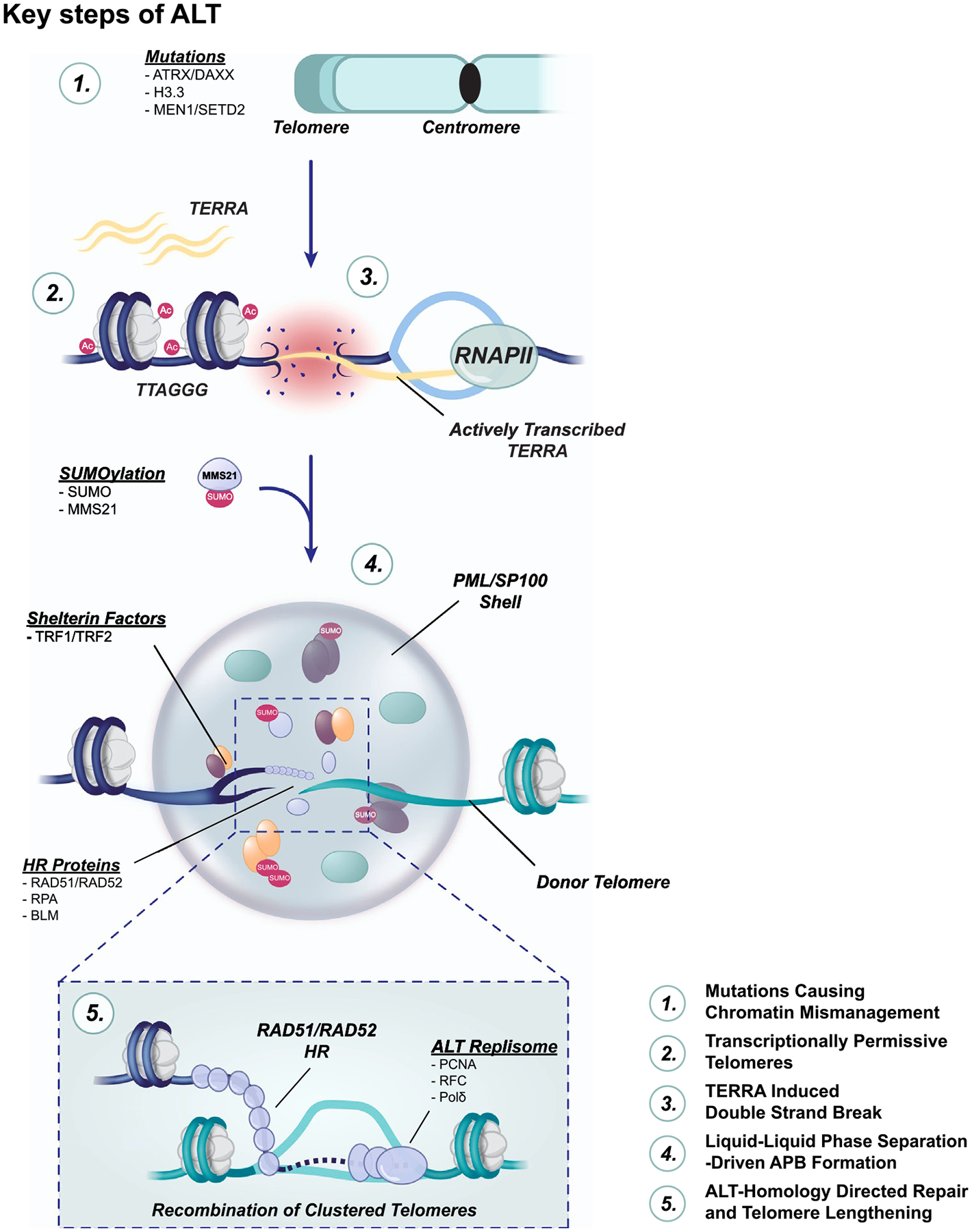

Likely stemming from mutations in key chromatin modifiers like ATRX-DAXX, the increased transcription of TERRA lincRNA and presence of TERRA at telomeres appears to create telomere instability and other defects in telomere replication that promote ALT. This may then set the stage for clustering of telomeres within sub-nuclear structures known as ALT-associated PML bodies (APBs) that is guided by RAD51 or RAD52-mediated homologous recombination and liquid-phase separation involving protein SUMOylation. These events can culminate in telomere extension via multiple, and possibly redundant, DNA synthesis pathways. Recent developments that have advanced our mechanistic understanding of these key steps of ALT (Fig. 1) will be discussed in the next sections.

Fig. 1.

The key features and stages of ALT telomere maintenance. Mutations in chromatin modifiers ATRX-DAXX, histone H3.3, MEN1 and SETD2 are frequent in ALT cancer cells. As a result, decondensed chromatin at telomeres is rich in euchromatin histone marks (i.e., H3K9ac) and transcription of TERRA. TERRA can promote replication stress at ALT telomeres leading to collapsed replication forks and DNA breaks. Those broken telomeres are trafficked and encased in phase-separated condensates within the nucleus that are formed through SUMO-SIM interactions among PML, telomeric and HR proteins. These structures, ALT-associated PML bodies (APBs), seem to be integral for telomere DNA synthesis that follows RAD51 or RAD52 dependent homologous recombination that sets the stage for telomere extension by the ALT replisome: PCNA-RFC1–5-Polδ.

3.1. The curious case of APBs

Shortly after the discovery of ALT in mammalian cells, it was found that ALT cancer cells harbor unique subnuclear telomere structures called ALT-associated PML bodies (APBs) [41]. APBs have become a defining hallmark of cancer cells that activate ALT and APB detection by evolving methodologies is used to determine whether patient-derived tumors may have activated ALT. Despite their biomedical importance as a potential ALT biomarker, the precise role and mechanism of APB formation in ALT cancer cells have remained enigmatic. APBs represent the sequestration of multiple telomeres together with subunits of Shelterin (TRF1 and TRF2) and for HR proteins (RAD51, RAD52, RPA and BLM) within PML nuclear bodies [41,42]. The association with HR factors implied that APBs could be ‘recombination factories’ where HR processing of telomeres occurs. Indeed, recent evidence indicates that RAD52-dependent telomere DNA synthesis requires mature and intact APBs [43]. Early studies revealed that APB formation is dynamic and involves assembly-disassembly during the cell cycle that peaks during G2-phase [44]. The frequency of APB formation is relatively low but consistent among populations of cancer cells [41]. However, APB frequency is highly correlated with the levels of endogenous telomere instability and APB levels can be enhanced by exposing cells to DNA damaging or replicative stress agents that promote HDR [45–48]. Conversely, lowering of APB frequency often correlates with impaired ALT-HDR. Thus, APBs provide a molecular rheostat of ‘ALT activity’.

Several studies identified SUMOylation (Small ubiquitin-like modifier) as being crucial for APB formation, linking it with the trafficking of SUMO-targeted telomere-associated proteins to PML bodies [44,49,50]. More recent studies showed that SUMO-driven APB formation involves biophysical behaviors that mimic liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) [51,52], a process that establishes sub-nuclear compartments to facilitate various cellular processes including RNA metabolism, transcription and DNA repair [53]. Non-covalent interactions between SUMO and SUMO-interaction motifs (SIMs) within PML, multiple PML-associated proteins (e.g., SP100), telomeric (TRF1, TRF2) and HR factors (BLM) are key factors that enable LLPS-mediated APB condensation. For instance, artificial tethering or chemical dimerization of SUMO-SIM modules was shown to stimulate LLPS-driven APB formation and telomere clustering. Similarly, tethering of PML-subunit IV to telomeres stimulated APB formation, telomere clustering and telomere DNA synthesis which required POLD3 and the helicase activity of BLM [50]. Interestingly, tethering the BLM interacting protein, RMI1, to telomeres bypassed the requirement for PML in stimulating DNA synthesis [54]. The implication of the latter may be that a critical function of APBs is to merely sequester BLM, and probably other HR factors, at telomeres to facilitate HDR. Of note, SUMO E3 Ligases such as MMS21 and PIAS4 have key roles in ALT [49,50], likely through targeting of HR and DNA repair proteins. For example, MMS21-dependent SUMOylation was shown to stabilize RAD51AP1, a RAD51 accessory factor with an apparent specialized role in HR and telomere DNA synthesis [55]. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the sequestration of HR factors within PML bodies alters their biophysical properties, conferring the pro-recombinogenic activities necessary for ALT.

While SUMOylation is clearly an important factor in LLPS-driven APB formation, other post-translational factors are surely involved. ADP-ribosylation is well-established in LLPS-dependent initiation of the DNA damage response (DDR) [56]. Here, PARP1 mediated poly-ADP-ribosylation (PARylation) fosters the rapid assembly of early-response DDR factors at DSB sites that are later released through de-PARylation by the PAR Glycohydrolase, PARG. Even though a role for ADP-ribosylation in LLPS-directed APB formation has not been formally shown, PARP1 and PARG regulated localization of LLPS factors, like the FET proteins (FUS-EWS1-TAF15), NONO and RBMX1, to telomeres and TRF1-FokI DSBs was shown suggesting their involvement at early stages of ALT [57,58]. Given the importance of PARP1 as a therapeutic target in cancer [59], understanding the role of PARP and its links with SUMO in LLPS at telomeres should be of interest. Lastly, members of the Shelterin complex can drive LLPS [60]. However, rather than compartmentalizing telomeres for DNA repair, a surprising outcome of biophysical optogenetic experiments revealed that LLPS of Shelterin serves as a shield against uncontrolled DNA repair and selectively grants access of DNA repair proteins to telomeres. Therefore, LLPS-driven mechanisms could be a determinant of HDR pathway choice and timing of ALT-HDR. Further elucidating the mechanisms that contribute to LLPS to telomeres in ALT cancer cells, identifying the factors involved, and uncovering its functional contribution will be of significance.

3.2. Re-branding the ALT mechanism

Several breakthrough studies have begun to unmask the molecular details of the ALT-associated HDR mechanisms. Taking cues from the HO-endonuclease system that is used to model break-induced replication (BIR) in yeast, an analogous system, TRF1-FokI, that anchored the FokI endonuclease at telomeres through fusion with TRF1 generated DNA breaks provided a means to artificially but synchronously stimulate ALT-HDR [61]. After TRF1-FokI cleavage, telomeres exhibited enhanced nuclear dynamics typical of RAD51-dependent homology search and pairing with homologous donor sequences as seen during HR. What was observed was remarkable. Whereas the damaged telomere exhibited enhanced mobility, it often pairs with a less mobile telomere. What controls this is unclear. But it could be linked with F-actin dynamics that were described in other contexts of HDR [62]. Furthermore, the involvement of meiosis-specific factors Hop2-Mnd1 provided a novel twist to this process and suggested that the ALT-HDR mechanism might be a derivation of both somatic and meiotic HR processes.

Subsequent assessment of this system revealed the loading of PCNA by RFC1–5 and the DNA polymerase delta (Polδ) and its subunits POLD3 and POLD4 are critical drivers of this ‘break-induced telomere DNA synthesis’ (BITS) [63]. Interestingly, even though BITS can initiate at breaks formed anywhere along the tract of telomere duplex, once initiated it proceeds to the end of the template strand and generates hyper-extended telomeres. But in addition, the induction of telomere breaks enabled direct loading of PCNA-RFC-Polδ ‘ALT-replisome’ that did not require RAD51. Subsequent studies showed that RAD52, another DNA recombinase, can also localize to TRF1-FokI-induced telomere breaks predominately in the G2/M phases of the cell cycle when BITS is maximal [64]. This RAD52 dependent pathway seems to be primarily responsible for telomere extension during G2-phase and RAD52 KO ALT cells appear to exhibit telomere shortening [43]. The circumstances that dictate the ‘choice’ of utilizing RAD51 or RAD52 dependent pathway are unclear. RAD51-mediated loading of the ALT-replisome is slower which may be due to the migration of telomeres that is required to bring telomeres within proximity [61,63]. Like RAD51, RAD52 can promote strand invasion and D-loop formation in vitro. But in contrast with RAD51, which requires an available sister chromatid, RAD52 dependent strand invasion can occur between intra-telomeric substrates (i.e., located within the same telomere). Further investigations of the mechanisms that distinguish RAD51- and RAD52-dependent telomere DNA synthesis in ALT are ongoing.

But telomere DNA synthesis at ALT telomeres has additional complexities Telomere extension at ALT telomeres involves conservative replication and is like break-induced replication (BIR) [65,66]. As with DNA synthesis primed from DNA breaks, BIR occurs in G2-phase and requires POLD3 and POLD4 subunits of Polδ, as well as RAD52. Surprisingly, exposing cells to G-quadruplex stabilizing ligands (Pyridostatin) or overexpression of oncogenic stressors like Cyclin E caused spontaneous telomere DNA synthesis in early mitosis [67]. Such mitotic DNA synthesis (MiDaS) also depends on RAD52 and other ALT factors like BLM, SMC5/6 and SLX4. However, in contrast to BITS and BIR, the contribution of MiDaS to ALT telomere extension may be minimal and even counterproductive in certain instances [64]. On the one hand, MiDaS that is directed by RAD52 could be a salvage mechanism to suppress the detrimental effects of deregulated BITS or BIR. Yet, in the event of persistent replicative stress in early mitosis or cleavage of HDR intermediates by the SLX1–4, MUS81-EME1, XPF-ERCC1 (SMX) complex, MiDaS that is not driven by RAD52 has been observed [64]. Thus, by re-appropriating HR proteins, multiple mechanisms appear to have evolved to preserve telomeres in ALT cancer cells. Although dictated by subtle temporal differences in cell-cycle phasing, these modalities of telomere DNA synthesis appear to functionally converge in maintaining functional telomeres to ensure the secure passage of ALT cancer cells through mitosis.

3.3. Reining in the BTR complex is key to productive ALT

BLM is a RecQ helicase that has a multitude of functions in HR [68, 69]. BLM localizes to telomeres in normal, ALT and non-ALT cells, but accumulates within APBs in ALT cells [70–73]. BLM was among the very first factors to be identified as ‘essential’ for ALT. BLM deficiency impairs APB formation and prevents the generation of extra-chromosomal telomere DNA species such as C-circles [28,43,47], another important potential biomarker of ALT activity in cancer cells [74]. Complete disruption of BLM expression in ALT cell lines led to a unique pattern of progressive telomere shortening[54]. Conversely, stable overexpression of BLM overexpression caused telomere hyper-extension [75]. BLM was also shown to be required for ALT activation through either Anti-Silencing Function 1a-b (ASF1a-b) depletion [28] or infection Kaposi-Sarcoma Herpesvirus (KSHV) infection [76] of non-ALT cells. As mentioned above, tethering BLM at telomeres can also directly lead to HDR-directed telomere DNA synthesis [51,54]. Thus, BLM is required for the establishment and maintenance of ALT.

BLM localization at telomeres requires TOP3a (TOPIIIα) and RMI1, with whom it forms the BTR (BLM-TopIIIa-RMI1) complex, or ‘dissolvasome’, that removes Holliday Junctions and other DNA intermediates formed during HR [77]. In addition, the BTR complex, and especially BLMs helicase activity, is critical for telomere DNA synthesis [54]. BLM and the BTR complex might facilitate Polδ-dependent DNA synthesis via branch migration [75], perhaps acting in conjunction with RAD54 [78]. Several important studies revealed that the FANCM DNA translocase regulates branch migration activity of BLM and the BTR complex during ALT[47,48,79]. FANCM depletion hyper-activated ALT, manifested by extreme levels of APB formation and telomere DNA synthesis. This DNA synthesis depended on the presence of BLM, and thus BTR, and was catalyzed through a non-productive RAD52 pathway that did not extend telomeres. Instead, FANCM deficient cells accumulated high levels of C-circles, R-loops and replicative stress that presumably cause the ensuing systemic cell death. Interestingly, domain analysis revealed that FANCMs fork remodeling activity is critical to restricting unchecked BLM-mediated DNA synthesis in ALT cells [47]. This intermolecular relationship further solidified the finding that FANCM and BLM exhibit synthetic lethality [80].

Interestingly, restricting unchecked BLM activity is not specific to FANCM. The MutSα complex was found to limit BLM at ALT telomeres by regulating heteroduplex rejection [81], a mechanism that prevents premature DNA synthesis initiation at similar but not identical DNA sequences [82]. MutSα complex deficiency caused hyperextension of telomeres with the expansion of variant telomere repeat sequences (e.g., TCAGGG, TGAGGG), a likely consequence of premature HR and DNA synthesis initiation within variant-rich distal telomere sequences, that is then further promoted by BLM. However, this hyper-extension phenotype was suppressed by co-depletion of BLM. Intriguingly, MutSα and FANCM deficiency elicited opposing phenotypes. In contrast with the phenotype seen with FANCM deficiency [48], loss of MutSα led to telomere extension and increased APB frequency, without affecting the levels of C-circles or cell viability [81]. The implication is that unlicensed BLM mediated DNA synthesis that can be either tolerable or intolerable, and that selective and specific targeting of the BLM-FANCM network could be therapeutically preferential.

Finally, one of the most striking roles of the BTR complex at ALT telomeres includes its antagonizing relationship with the SLX1–4, Mus81-EME1, XPF-ERCC1 (SMX) complex at ALT telomeres [75]. Namely, the loss of the BTR complex causes an increase in telomere sister chromatid exchanges (T-SCEs) which are driven by the SMX complex. Recent evidence indicates that the balance between the resolution and dissolution activities of BLM and the SMX complex, respectively, during recombination at ALT telomeres can be regulated by SLX4 interacting protein (SLX4IP). SLX4IP can inhibit BLM gene transcription to regulate its cellular levels, and functions with SLX4 to prevent hyper recombination between ALT telomeres [83]. In fact, combined loss of SLX4 and SLX4IP can enhance several ALT hallmarks, such as APBs, which can be rescued by co-depletion of BLM. Together, these findings indicate that the BTR complex’s role at ALT telomeres appears to be important to facilitate telomere synthesis and prevent telomere sister chromatid exchanges, and despite its multiple roles, its activity needs to be heavily regulated to preserve telomere integrity.

3.4. Emerging evidence of TERRA directed ALT

TERRA (telomere repeat-containing RNA) is a long-noncoding RNA (lincRNA) comprised of G-rich telomeric tandem repeats (5’-UUAGGG-3’) [84,85]. TERRA transcription by RNA Polymerase II initiates from cryptic CpG promoters located within sub-telomeric regions and has been linked to regulating chromatin structure and protein recruitment dynamics at telomeres [86]. In normal and telomerase expressing cells, TERRA levels begin to decrease in S-phase and are lowest as cells pass through G2-phase [87]. However, in ATRX-DAXX mutant ALT cells, this cell cycle-dependent regulation is abrogated, and TERRA accumulates at telomeres in the G2 phase [86]. TERRA can hybridize with complementary telomere DNA sequences forming R-loops that act as impediments to normal telomere replication and promote stochastic DNA damage which is evident at telomeres in ALT cancer cells. Factors linked with R-loop mitigation, including the RNA endonuclease RNaseH1, are present in ALT cells to mitigate excess R-loop formation [88]. The first clues that TERRA may contribute to ALT came from observations that depletion of RNaseH1 led to an overwhelming accumulation of TERRA R-loops and a profound increase in replication stress at ALT telomeres. Conversely, overexpression of RNaseH1 reduced R-loop levels, attenuating ALT activity leading to telomere shortening [88]. More recently, through the use of Transcription Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs) targeting the CpG rich tandem repeats that drive telomeric transcription, short-term depletion of TERRA abrogated markers of replication stress and DNA damage that are typical at ALT telomeres [89]. These data strongly suggest that TERRA is a destabilizing force that enhances replicative stress or telomere damage that triggers ALT-HDR.

One of the outstanding questions regarding TERRA is centered around its origin. Where TERRA transcription initiates and executes its function are important mechanistic questions. Nascent TERRA could form R-loops co-transcriptionally, in cis, and cause DNA breaks or replicative stress in situ [88,89] (Fig. 2A). However, several groups have provided evidence of TERRA transcripts originating from either one or many different telomeres [90–92] or transcribed from plasmid-based systems, associating with distinct chromatin domains in trans [93] (Fig. 2A-C). RNA transcripts such as TERRA can directly interact with HR factors to stimulate recombination by promoting the formation of HR intermediates (Fig. 2D). Indeed, TERRA directly interacts with RAD51 and BRCA2 to catalyze strand invasion and formation of R-loops as well as D-loops [93,94]. Another study described RAD51-associated protein 1 (RAD51AP1)-dependent catalysis of unique DNA-RNA HR intermediates termed DR-loops [95]. Here RNA bound to RAD51AP1 was shown to promote the formation of an R-loop, which then serves as a template for RAD51-mediated D-loop during strand invasion. Although evidence of RAD51AP1 in binding TERRA or promoting DR-loops at telomeres has not been reported, it begs the question of whether RAD51AP1 mediates ALT through modulation of TERRA and if there are other proteins that coordinate TERRA invasion of telomeric DNA [55]. These studies have created the exciting scenario of TERRA cooperating with the HR machinery to direct the key steps of ALT. Beyond this new role in HR, lincRNAs like TERRA provide scaffolds for DNA repair factors and modulate chromatin structure to facilitate nuclear activities. Given the significant amount of TERRA that associates with chromatin, understanding the precise role(s) of TERRA, at the telomere and possibly at non-telomeric loci, will be of major interest in coming years. Understanding the precise mechanism of TERRA strand invasion may yield the discovery of critical unknown ALT factors and chromatin remodelers as well as potential non-telomeric sites of TERRA activity (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Outstanding Questions Surrounding TERRA. The telomeric-specific long noncoding RNA molecule, TERRA, has been linked to DNA repair, regulation of telomeric protein localization, as well as other cellular processes. Despite recent advances, certain aspects of TERRA regulation and activity remain unclear. A) It is unknown whether TERRA exerts its regulatory functions at telomeres as it is actively transcribed (in cis) or post-transcriptionally at other telomeres (in trans). B) TERRA transcription is posited to be initiated at many sub-telomeres. Characterization and classification of the specific sub-telomeres of origin will be crucial to understanding TERRA function. C) Telomeric DNA sequences can occur outside of telomeres (shown in orange). It is unknown whether mature TERRA can localize to these genomic regions and execute its regulatory roles. D) A comprehensive characterization of the factors necessary for RNA strand invasion and R-Loop formation is needed. Understanding the formation TERRA: DNA hybrids may provide key insight into the relationship between R-loops, DR-Loops, and ALT-specific HR.

4. Fatal ALTtraction: Emerging therapeutic interventions for ALT

Given their indelible association with cancer, there have been considerable investments made in determining ways to target telomere maintenance mechanisms, particularly telomerase, as cancer therapies. Yet, unlike telomerase which is expressed in healthy stem and germ cells as well as cancer cells, ALT is only active in cancer cells. This and its association with a spectrum of predominantly untreatable cancers make ALT an attractive target for therapy development. As discussed in previous sections, one of the breakthrough outcomes of mechanistic studies of ALT has been the realization that exploiting the FANCM-BLM interaction could be hugely significant in treating ALT cancers [47,48,79]. Overexpression of a 28 amino acid micropeptide of the FANCM protein was sufficient to sequester BLM and cause selective cytotoxicity of ALT cancer cells, as opposed to telomerase expressing cells that were relatively unaffected [47] (Fig. 3). Clearly, developing cell-penetrating and bioactive micropeptides that induce this outcome in ALT cells is highly desirable.

Fig. 3.

Synthetic Lethality Strategies for ALT Cancers. (Top) FANCM-BLM Synthetic Lethality. ALT telomeres harbor DNA secondary structures that are difficult to replicate across, e.g., G4 quadruplexes, that can lead to the formation of stalled replication forks. FANCM is required for fork reversal and to facilitate fork restart. Loss of FANCM leads to fork collapse which needs to be repaired in a Bloom helicase (BLM)-dependent manner. Thus, combined FANCM and BLM deficiencies lead to a failure to repair collapsed form and loss of cellular viability. (Below) ALT/ATRX Synthetic Lethality. (Top left) Due to the prevalence of loss of function mutations in the ATRX/DAXX histone chaperone complex in ALT cancer cells, several strategies for targeting these cancers have been focused on developing synthetic lethality strategies for ATRX/DAXX deficiency. Evidence from sequencing analyses of neuroblastomas indicates that MYCN amplification is incompatible with ATRX/DAXX-deficiency. In fact, MYCN amplification in ATRX/DAXX-deficient cells results in DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction. (Top right) Both PARP inhibitors (PARPi), ATR inhibitors (ATRi) and Wee1 kinase inhibitors (Wee1i) are currently in clinical trials for different cancers due to their ability to induce replication-associated DNA damage and dampen the DNA repair response to stalled replication forks, respectively. ALT telomeres harbor transcriptionally permissive chromatin and replicative stress burden. Thus, combinatorial treatment of ATRX-deficient cells with both PARPi and ATRi amplifies the replication stress to toxic levels and limits cellular viability. Wee1 kinase inhibition may synergize with ATRX loss to impair the G2/M checkpoint leading to replicative stress. (Below Left) Newly synthesized telomeric DNA needs to be appropriately chromatinized before cell division. A recent study reported that the HIRA-complex is indispensable for depositing histone H3.3 in ATRX mutated ALT cancer cells. Thus, this compensatory complex has emerged as a possible therapeutic target. (Below Center) ATRX/DAXX-deficient are sensitive to infection by the ICP0-deficient Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)– 1 since ATRX inhibits the expression of viral proteins. ATRX-deficient ALT cells also harbor specialized nuclear structures called ALT-associated PML bodies (APBs). (Below Right) TSPYL5 localizes to APBs and inhibits USP7, thus preventing the proteasomal degradation of POT1, a critical member of the Shelterin complex that ensures telomere integrity. Thus, depleting TSPYL5 causes a loss of viability of ALT cancer cells due to telomere destabilization.

Other recent efforts have largely been focused on finding synthetic lethal opportunities with ATRX/DAXX. Several lessons about the compatibility of ATRX with other pathways have come from neuroblastoma (NB). MYCN amplification is a main driver of high-grade neuroblastoma, found in ~40% of cases [96]. Interestingly, a significant subset of MYCN negative NB exhibit ALT and harbor ATRX-DAXX inactivating or loss of function mutations [97–99]. Overexpression of MYCN in these ATRX-deficient NB cells led to DNA fragmentation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and transcriptional changes indicating that MYCN amplifications cause synthetic lethality with ATRX mutations [100]. Since MYCN amplification can have varied effects, the effect that causes this intolerance to ATRX deficiency remains to be identified (Fig. 3). In addition to their susceptibility to MYCN, there have been several reports in which ATRX-mutant NB cells exhibited sensitivity to chromatin modifier inhibition (EZH2i) [101] or DNA repair factor inhibition. Most notably, PARP and ATM inhibition have been shown to expedite the elimination or ALT NB cells and overcome resistance to first-line therapies [102,103].

PARP inhibitors have shown immense biomedical value in the treatment of breast, ovarian, and a growing spectrum of other cancers [59]. The rationale for redeploying PARP inhibitors and other DNA repair factor inhibitors in the ALT arena is supported by the heightened burden of DNA damage and cell-cycle deregulation that is evident in ALT cancer cells. Recent evidence showed that Olaparib (Lynparza) and Talazoparib caused cell death in ATRX-mutant ALT cancer cells as opposed to telomerase expressing cancer cells [58,103–105]. PARP inhibitors were also found to enhance cell death in irinotecan-sensitive ATRX-mutant ALT neuroblastoma cell lines [103]. Furthermore, a chemogenomic screen identified that ALT cancer cell lines show similar increased sensitivity to combined treatment with Talazoparib or Olaparib with newly developed ATR inhibitors (Zimmerman et al., Cell Reports/in press (M. Zimmerman personal communication). This is particularly notable considering the potential utility of ATR inhibitors in ALT therapeutics [106–108].

Synthetic lethal CRISPR screening of isogenic control and ATRX-knockout cells identified the Wee1 G2/M checkpoint kinase as another potential vulnerability of ATRX-mutant ALT cancer cells that could be explored [109] (Fig. 3). Many other potential hits have emerged from CRISPR-guided synthetic lethal screening of ATRX-KO cells. One screen identified 57 other genes as being essential important for the survival of ATRX-KO cells [109]. These included members of the SMC5/6 complex that was previously linked with ALT telomere maintenance [49] and the HIRA-UBN1-CABIN1-ASF1a (HUCA) histone H3.3 histone chaperone complex [110]. A key caveat of this CRISPR screen was the sole investigation of ATRX- deficient cells, but not ALT per se [109]. Additionally, how these studies extend to ALT cancer cells that harbor mutations in DAXX or H3.3 remain unknown. However, a proteomics-based screen also identified the HIRA subunit of the HUCA complex as a synthetic lethal partner of ATRX-deficient ALT cancer cells [58]. This study showed that in ATRX-deficient ALT cancer cells adopt HIRA-mediated H3.3 deposition to compensate for the loss of ATRX-DAXX and that HIRA is required to sustain ALT-HDR (Fig. 3). Notably, the family of Tousled-like kinases (TLKs) that regulate H3.3 deposition through HIRA have also been associated with supporting ALT cells survival by dampening innate immune signaling in ALT cells [111]. This would further support the major role of the HIRA, and its adjacent factors, as having crucial roles in ALT. However, like other essential chromatin modifiers, that have since proven to be targetable (e.g., EZH2) HIRA and other members of the HUCA complex are often categorized as genes that are essential for survival. Yet, strategies to disrupt cognate interactions of these factors that are necessary for histone deposition are starting to emerge [112,113]. These could have benefits in targeting ATRX-DAXX or H3.3 mutant cells by preventing unwarranted and/or discrepant H3.3 deposition at genes that drive oncogenesis. Overall, by taking advantage of the ATRX-DAXX deficiency of ALT cancers a myriad of targets has emerged. Defining new and more selective targets, as well as tailoring those that already exist, could have important consequences for targeting most ALT cancers.

In addition to the findings of these chemogenomic and proteomic screening methods, several independent paths to ALT cell elimination are being explored. For instance, PML has long been known to be a target for herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) replication (Fig. 3). A mutant strain of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) that lacks the ICP0 protein infects ATRX-deficient cells with greater efficiency than wild-type ATRX-expressing counterparts [114]. Intriguingly, the susceptibility was attributed to the loss of ATRX-mediated control of PML expression that diminished PML cellular levels. This finding indicated that the susceptibility of cancer cells to oncolytic herpes viruses may provide powerful tools either as independent biomarkers of ALT or ATRX-functionality, as well as in virus-guided delivery of select agents. Another report that used transcriptomic arrays to identify uniquely upregulated genes in ALT but not telomerase expressing cancer cells found TSPYL5 as a potential candidate for synthetic lethality therapy in ALT cancer cells [115]. TSPYL5 interacts with POT1 sequestered within APBs which may protect against USP7-mediated degradation of POT1. In the absence of TSPYL5, USP7 can freely degrade POT1, triggering telomere dysfunction and inducing cell death (Fig. 3). Indeed, ALT cancer cells were more susceptible to TSPYL5 depletion compared to telomerase expressing cells. This suggests that factors like TSPLY or others that become sequestered within PML bodies in ALT cells could be targeted by E3 ligase-based protein degraders.

The breakneck pace at which new targets are being identified reflects the urgency to meet a dire clinical need to treat those cancers that rely on ALT, many of which have been essentially untreatable despite years of intense efforts. Before the trials of potential therapies inevitably materialize, diagnostics and practices that consider and categorize the ALT (or telomerase) status of cancers, as was proposed for some cancers that rely on telomere maintenance mechanisms, should be ameliorated. Indeed, multiple optogenetic and genomics-based diagnostic approaches are being pursued [74,116–119]. Tractable and reliable ALT diagnostics will be highly beneficial for cancer diagnosis, but also for risk stratification and treatment course determination. Developments in the next years should see those methods of ALT, and/or ATRX-DAXX detection, come to the fore with clinical trials of new targets inevitably to follow.

5. Concluding Remarks

It has been an incredibly exciting few years in ALT biology, underscored by several breakthrough discoveries. So much more is known about the mechanisms that regulate ALT have been uncovered and essential mediators have been identified. Novel strategies with real potential will be tested in potentially treating ALT tumors. Yet, it still seems that we are only scratching the surface of ALT. The complexity of this is underscored by the involvement, or transient usurping, of factors involved in multiple DNA repair mechanisms. Of course, further insights of the mechanisms that drive ALT will be explored. Our knowledge of TERRA as a driving force in ALT is beginning to emerge but its functional interactions with the HR machinery is a new twist. While TERRA appears to trigger ALT-HDR, it may also facilitate and maintain HR intermediates that are essential conduits for efficient telomere extension. There is much to learn about the factors that regulate TERRA’s role in this novel context. As is the involvement of LLPS-driven APB formation which in large respects, remains enigmatic. Similarly, understanding the complexity of the epigenetic and chromatin alterations wrought by the loss of ATRX-DAXX, and other chromatin modifiers such as oncohistones, and their impact on the ALT mechanism is an important challenge. Navigating these problems and open questions will be crucial for the discovery of additional therapeutic ALT-specific interventions.

Acknowledgments

We thank laboratory members for their critical reading of the manuscript. R.B is a recipient of the Hillman Postdoctoral Fellowship for Innovative Cancer Research. M.L.L is the recipient of the John S. Lazo Cancer Pharmacology Fellowship from the Department of Pharmacology & Chemical Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Research funding was provided to investigators from the following agencies: R.J.O. NCI/#R01CA207209, R37CA263622, and American Cancer Society #RSG-18–038-01-DMC.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Maciejowski J, de Lange T, Telomeres in cancer: tumour suppression and genome instability, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 18 (2017) 175–186, 10.1038/nrm.2016.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nassour J, Radford R, Correia A, Fusté JM, Schoell B, Jauch A, et al. , Autophagic cell death restricts chromosomal instability during replicative crisis, Nature 565 (2019) 659–663, 10.1038/s41586-019-0885-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, et al. , Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer, Science 266 (1994) 2011–2015, 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bryan TM, Englezou A, Dalla-Pozza L, Dunham MA, Reddel RR, Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines, Nat. Med 3 (1997) 1271–1274, 10.1038/nm1197-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lundblad V, Blackburn EH, An alternative pathway for yeast telomere maintenance rescues est1- senescence, Cell 73 (1993) 347–360, 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90234-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hu J, Hwang SS, Liesa M, Gan B, Sahin E, Jaskelioff M, et al. , Antitelomerase therapy provokes ALT and mitochondrial adaptive mechanisms in cancer, Cell 148 (2012) 651–663, 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lafferty-Whyte K, Cairney CJ, Will MB, Serakinci N, Daidone M-G, Zaffaroni N, et al. , A gene expression signature classifying telomerase and ALT immortalization reveals an hTERT regulatory network and suggests a mesenchymal stem cell origin for ALT, Oncogene 28 (2009) 3765–3774, 10.1038/onc.2009.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Heaphy CM, de Wilde RF, Jiao Y, Klein AP, Edil BH, Shi C, et al. , Altered telomeres in tumors with ATRX and DAXX mutations, –425, Science 333 (2011) 425, 10.1126/science.1207313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goldberg AD, Banaszynski LA, Noh K-M, Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Stadler S, et al. , Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions, Cell 140 (2010) 678–691, 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Noh K-M, Stadler SC, Allis CD, Daxx is an H3.3-specific histone chaperone and cooperates with ATRX in replication-independent chromatin assembly at telomeres, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. a 107 (2010) 14075–14080, 10.1073/pnas.1008850107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Valle-Garcia D, Qadeer ZA, McHugh DS, Ghiraldini FG, Chowdhury AH, Hasson D, et al. , ATRX binds to atypical chromatin domains at the 3’ exons of zinc finger genes to preserve H3K9me3 enrichment, Epigenetics 11 (2016) 398–414, 10.1080/15592294.2016.1169351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Voon HPJ, Hughes JR, Rode C, De La Rosa-Velázquez IA, Jenuwein T, Feil R, et al. , ATRX Plays a Key Role in Maintaining Silencing at Interstitial Heterochromatic Loci and Imprinted Genes, Cell Rep. 11 (2015) 405–418, 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Law MJ, Lower KM, Voon HPJ, Hughes JR, Garrick D, Viprakasit V, et al. , ATR-X syndrome protein targets tandem repeats and influences allele-specific expression in a size-dependent manner, Cell 143 (2010) 367–378, 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sarma K, Cifuentes-Rojas C, Ergun A, Del Rosario A, Jeon Y, White F, et al. , ATRX directs binding of PRC2 to Xist RNA and polycomb targets, Cell 159 (2014) 869–883, 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nguyen DT, Voon HPJ, Xella B, Scott C, Clynes D, Babbs C, et al. , The chromatin remodelling factor ATRX suppresses R-loops in transcribed telomeric repeats, EMBO Rep. 18 (2017) 914–928, 10.15252/embr.201643078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dyer MA, Qadeer ZA, Valle-Garcia D, Bernstein E, ATRX and DAXX: mechanisms and mutations, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 7 (2017), a026567, 10.1101/cshperspect.a026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sieverling L, Hong C, Koser SD, Ginsbach P, Kleinheinz K, Hutter B, et al. , Genomic footprints of activated telomere maintenance mechanisms in cancer, 733–13, Nat. Commun 11 (2020), 10.1038/s41467-019-13824-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].de Nonneville A, Reddel RR, Alternative lengthening of telomeres is not synonymous with mutations in ATRX/DAXX, Nat. Commun 12 (2021) 1552–1554, 10.1038/s41467-021-21794-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Huang FW, Hodis E, Xu MJ, Kryukov GV, Chin L, Garraway LA, Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma, Science 339 (2013) 957–959, 10.1126/science.1229259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].de Wilde RF, Heaphy CM, Maitra A, Meeker AK, Edil BH, Wolfgang CL, et al. , Loss of ATRX or DAXX expression and concomitant acquisition of the alternative lengthening of telomeres phenotype are late events in a small subset of MEN-1 syndrome pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, Mod. Pathol 25 (2012) 1033–1039, 10.1038/modpathol.2012.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Singhi AD, Liu T-C, Roncaioli JL, Cao D, Zeh HJ, Zureikat AH, et al. , Alternative lengthening of telomeres and loss of DAXX/ATRX expression predicts metastatic disease and poor survival in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, Clin. Cancer Res 23 (2017) 600–609, 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Roy S, LaFramboise WA, Liu T-C, Cao D, Luvison A, Miller C, et al. , Loss of chromatin-remodeling proteins and/or CDKN2A associates with metastasis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and reduced patient survival times, e8, Gastroenterology 154 (2018) 2060–2063, 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hackeng WM, Brosens LAA, Kim JY, O’Sullivan R, Sung Y-N, Liu T-C, et al. , Non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: ATRX/DAXX and alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) are prognostically independent from ARX/PDX1 expression and tumour size, Gut (2021), 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hartlieb SA, Sieverling L, Nadler-Holly M, Ziehm M, Toprak UH, Herrmann C, et al. , Alternative lengthening of telomeres in childhood neuroblastoma from genome to proteome, 1269–18, Nat. Commun 12 (2021), 10.1038/s41467-021-21247-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hoelper D, Huang H, Jain AY, Patel DJ, Lewis PW, Structural and mechanistic insights into ATRX-dependent and -independent functions of the histone chaperone DAXX, 1193–13, Nat. Commun 8 (2017), 10.1038/s41467-017-01206-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Elsässer SJ, Noh K-M, Diaz N, Allis CD, Banaszynski LA, Histone H3.3 is required for endogenous retroviral element silencing in embryonic stem cells, Nature 522 (2015) 240–244, 10.1038/nature14345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Li F, Deng Z, Zhang L, Wu C, Jin Y, Hwang I, et al. , ATRX loss induces telomere dysfunction and necessitates induction of alternative lengthening of telomeres during human cell immortalization, Embo J. 38 (2019), e96659, 10.15252/embj.201796659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].O’Sullivan RJ, Arnoult N, Lackner DH, Oganesian L, Haggblom C, Corpet A, et al. , Rapid induction of alternative lengthening of telomeres by depletion of the histone chaperone ASF1, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 21 (2014) 167–174, 10.1038/nsmb.2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Clynes D, Jelinska C, Xella B, Ayyub H, Scott C, Mitson M, et al. , Suppression of the alternative lengthening of telomere pathway by the chromatin remodelling factor ATRX, 7538–11, Nat. Commun 6 (2015), 10.1038/ncomms8538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yost KE, Clatterbuck Soper SF, Walker RL, Pineda MA, Zhu YJ, Ester CD, et al. , Rapid and reversible suppression of ALT by DAXX in osteosarcoma cells, 4544–11, Sci. Rep 9 (2019), 10.1038/s41598-019-41058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mukherjee J, Johannessen T-C, Ohba S, Chow TT, Jones L, Pandita A, et al. , Mutant IDH1 cooperates with ATRX loss to drive the alternative lengthening of telomere phenotype in glioma, Cancer Res. 78 (2018) 2966–2977, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Udugama M, Hii L, Garvie A, Cervini M, Vinod B, Chan F-L, et al. , Mutations inhibiting KDM4B drive ALT activation in ATRX-mutated glioblastomas, 2584–11, Nat. Commun 12 (2021), 10.1038/s41467-021-22543-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jiao Y, Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Rasheed AB, Heaphy CM, de Wilde RF, et al. , Frequent ATRX, CIC, FUBP1 and IDH1 mutations refine the classification of malignant gliomas, Oncotarget 3 (2012) 709–722, 10.18632/oncotarget.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Diplas BH, He X, Brosnan-Cashman JA, Liu H, Chen LH, Wang Z, et al. , The genomic landscape of TERT promoter wildtype-IDH wildtype glioblastoma, 2087–11, Nat. Commun 9 (2018), 10.1038/s41467-018-04448-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Chan CS, Laddha SV, Lewis PW, Koletsky MS, Robzyk K, Da Silva E, et al. , ATRX, DAXX or MEN1 mutant pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are a distinct alpha-cell signature subgroup, 4158–10, Nat. Commun 9 (2018), 10.1038/s41467-018-06498-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu X-Y, Jones DTW, Pfaff E, Jacob K, et al. , Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma, Nature 482 (2012) 226–231, 10.1038/nature10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang D-A, Jones DTW, Konermann C, et al. , Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma, Cancer Cell 22 (2012) 425–437, 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lewis PW, Müller MM, Koletsky MS, Cordero F, Lin S, Banaszynski LA, et al. , Inhibition of PRC2 activity by a gain-of-function H3 mutation found in pediatric glioblastoma, Science 340 (2013) 857–861, 10.1126/science.1232245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Minasi S, Baldi C, Gianno F, Antonelli M, Buccoliero AM, Pietsch T, et al. , Alternative lengthening of telomeres in molecular subgroups of paediatric high-grade glioma, Childs Nerv. Syst 37 (2021) 809–818, 10.1007/s00381-020-04933-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gauchier M, Kan S, Barral A, Sauzet S, Agirre E, Bonnell E, et al. , SETDB1-dependent heterochromatin stimulates alternative lengthening of telomeres, Sci. Adv 5 (2019) eaav3673, 10.1126/sciadv.aav3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yeager TR, Neumann AA, Englezou A, Huschtscha LI, Noble JR, Reddel RR, Telomerase-negative immortalized human cells contain a novel type of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) body, Cancer Res 59 (1999) 4175–4179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Draskovic I, Arnoult N, Steiner V, Bacchetti S, Lomonte P, Londoño-Vallejo A, Probing PML body function in ALT cells reveals spatiotemporal requirements for telomere recombination, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. a 106 (2009) 15726–15731, 10.1073/pnas.0907689106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhang J-M, Yadav T, Ouyang J, Lan L, Zou L, Alternative lengthening of telomeres through two distinct break-induced replication pathways, e3, Cell Rep. 26 (2019) 955–968, 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chung I, Leonhardt H, Rippe K, De novo assembly of a PML nuclear subcompartment occurs through multiple pathways and induces telomere elongation, J. Cell. Sci 124 (2011) 3603–3618, 10.1242/jcs.084681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fasching CL, Neumann AA, Muntoni A, Yeager TR, Reddel RR, DNA damage induces alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) associated promyelocytic leukemia bodies that preferentially associate with linear telomeric DNA, Cancer Res 67 (2007) 7072–7077, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cox KE, Maréchal A, Flynn RL, SMARCAL1 Resolves Replication Stress at ALT Telomeres, Cell Rep. 14 (2016) 1032–1040, 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lu R, O’Rourke JJ, Sobinoff AP, Allen JAM, Nelson CB, Tomlinson CG, et al. , The FANCM-BLM-TOP3A-RMI complex suppresses alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT), 2252–14, Nat. Commun 10 (2019), 10.1038/s41467-019-10180-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Silva B, Pentz R, Figueira AM, Arora R, Lee YW, Hodson C, et al. , FANCM limits ALT activity by restricting telomeric replication stress induced by deregulated BLM and R-loops, 2253–16, Nat. Commun 10 (2019), 10.1038/s41467-019-10179-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Potts PR, Yu H, The SMC5/6 complex maintains telomere length in ALT cancer cells through SUMOylation of telomere-binding proteins, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 14 (2007) 581–590, 10.1038/nsmb1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zhang J-M, Genois M-M, Ouyang J, Lan L, Zou L, Alternative lengthening of telomeres is a self-perpetuating process in ALT-associated PML bodies, e4, Mol. Cell 81 (2021) 1027–1042, 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Min J, Wright WE, Shay JW, Clustered telomeres in phase-separated nuclear condensates engage mitotic DNA synthesis through BLM and RAD52, Genes Dev. 33 (2019) 814–827, 10.1101/gad.324905.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zhang H, Zhao R, Tones J, Liu M, Dilley RL, Chenoweth DM, et al. , Nuclear body phase separation drives telomere clustering in ALT cancer cells, Mol. Biol. Cell 31 (2020) 2048–2056, 10.1091/mbc.E19-10-0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Banani SF, Lee HO, Hyman AA, Rosen MK, Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 18 (2017) 285–298, 10.1038/nrm.2017.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Loe TK, Li JSZ, Zhang Y, Azeroglu B, Boddy MN, Denchi EL, Telomere length heterogeneity in ALT cells is maintained by PML-dependent localization of the BTR complex to telomeres, Genes Dev. 34 (2020) 650–662, 10.1101/gad.333963.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Barroso-González J, García-Expósito L, Hoang SM, Lynskey ML, Roncaioli JL, Ghosh A, et al. , RAD51AP1 Is an essential mediator of alternative lengthening of telomeres, e7, Mol. Cell 76 (2019) 11–26, 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Altmeyer M, Neelsen KJ, Teloni F, Pozdnyakova I, Pellegrino S, Grøfte M, et al. , Liquid demixing of intrinsically disordered proteins is seeded by poly(ADP-ribose), 8088–12, Nat. Commun 6 (2015), 10.1038/ncomms9088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Petti E, Buemi V, Zappone A, Schillaci O, Broccia PV, Dinami R, et al. , SFPQ and NONO suppress RNA:DNA-hybrid-related telomere instability, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 1001–1014, 10.1038/s41467-019-08863-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hoang SM, Kaminski N, Bhargava R, Barroso-González J, Lynskey ML, García-Expósito L, et al. , Regulation of ALT-associated homology-directed repair by polyADP-ribosylation, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 27 (2020) 1152–1164, 10.1038/s41594-020-0512-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Slade D, PARP and PARG inhibitors in cancer treatment, Genes Dev. (2020), 10.1101/gad.334516.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Jack A, Kim Y, Strom AR, Lee DSW, Williams B, Schaub JM, et al. , Compartmentalization of telomeres through DNA-scaffolded phase separation, e9, Dev. Cell 57 (2022) 277–290, 10.1016/j.devcel.2021.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Cho NW, Dilley RL, Lampson MA, Greenberg RA, Interchromosomal homology searches drive directional ALT telomere movement and synapsis, Cell 159 (2014) 108–121, 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Schrank BR, Aparicio T, Li Y, Chang W, Chait BT, Gundersen GG, et al. , Nuclear ARP2/3 drives DNA break clustering for homology-directed repair, Nature 559 (2018) 61–66, 10.1038/s41586-018-0237-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Dilley RL, Verma P, Cho NW, Winters HD, Wondisford AR, Greenberg RA, Break-induced telomere synthesis underlies alternative telomere maintenance, Nature 539 (2016) 54–58, 10.1038/nature20099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Verma P, Dilley RL, Zhang T, Gyparaki MT, Li Y, Greenberg RA, RAD52 and SLX4 act nonepistatically to ensure telomere stability during alternative telomere lengthening, Genes Dev. 33 (2019) 221–235, 10.1101/gad.319723.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Roumelioti F-M, Sotiriou SK, Katsini V, Chiourea M, Halazonetis TD, Gagos S, Alternative lengthening of human telomeres is a conservative DNA replication process with features of break-induced replication, EMBO Rep. 17 (2016) 1731–1737, 10.15252/embr.201643169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Min J, Wright WE, Shay JW, Alternative lengthening of telomeres can be maintained by preferential elongation of lagging strands, Nucleic Acids Res 45 (2017) 2615–2628, 10.1093/nar/gkw1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Min J, Wright WE, Shay JW, Alternative lengthening of telomeres mediated by mitotic DNA synthesis engages break-induced replication processes, Mol. Cell. Biol 37 (2017) 405, 10.1128/MCB.00226-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wu L, Hickson ID, The Bloom’s syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination, Nature 426 (2003) 870–874, 10.1038/nature02253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wechsler T, Newman S, West SC, Aberrant chromosome morphology in human cells defective for Holliday junction resolution, Nature 471 (2011) 642–646, 10.1038/nature09790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Barefield C, Karlseder J, The BLM helicase contributes to telomere maintenance through processing of late-replicating intermediate structures, Nucleic Acids Res 40 (2012) 7358–7367, 10.1093/nar/gks407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Acharya S, Kaul Z, Gocha AS, Martinez AR, Harris J, Parvin JD, et al. , Association of BLM and BRCA1 during telomere maintenance in ALT cells, PLoS ONE 9 (2014), e103819, 10.1371/journal.pone.0103819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Déjardin J, Kingston RE, Purification of proteins associated with specific genomic Loci, Cell 136 (2009) 175–186, 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].García-Expósito L, Bournique E, Bergoglio V, Bose A, Barroso-González J, Zhang S, et al. , Proteomic profiling reveals a specific role for translesion DNA polymerase η in the alternative lengthening of telomeres, Cell Rep. 17 (2016) 1858–1871, 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Henson JD, Cao Y, Huschtscha LI, Chang AC, Au AYM, Pickett HA, et al. , DNA C-circles are specific and quantifiable markers of alternative-lengthening-oftelomeres activity, Nat. Biotechnol 27 (2009) 1181–1185, 10.1038/nbt.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Sobinoff AP, Allen JA, Neumann AA, Yang SF, Walsh ME, Henson JD, et al. , BLM and SLX4 play opposing roles in recombination-dependent replication at human telomeres, Embo J. 36 (2017) 2907–2919, 10.15252/embj.201796889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Lippert TP, Marzec P, Idilli AI, Sarek G, Vancevska A, Bower M, et al. , Oncogenic herpesvirus KSHV triggers hallmarks of alternative lengthening of telomeres, 512–11, Nat. Commun 12 (2021), 10.1038/s41467-020-20819-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].West SC, Blanco MG, Chan YW, Matos J, Sarbajna S, Wyatt HDM, Resolution of recombination intermediates: mechanisms and regulation, Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol 80 (2015) 103–109, 10.1101/sqb.2015.80.027649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Mason-Osann E, Terranova K, Lupo N, Lock YJ, Carson LM, Flynn RL, RAD54 promotes alternative lengthening of telomeres by mediating branch migration, EMBO Rep. 21 (2020), e49495, 10.15252/embr.201949495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Pan X, Chen Y, Biju B, Ahmed N, Kong J, Goldenberg M, et al. , FANCM suppresses DNA replication stress at ALT telomeres by disrupting TERRA R-loops, Sci. Rep 9 (2019) 19110–19114, 10.1038/s41598-019-55537-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Pan X, Drosopoulos WC, Sethi L, Madireddy A, Schildkraut CL, Zhang D, FANCM, BRCA1, and BLM cooperatively resolve the replication stress at the ALT telomeres, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. a 114 (2017) E5940–E5949, 10.1073/pnas.1708065114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Barroso-González J, García-Expósito L, Galaviz P, Lynskey ML, Allen JAM, Hoang S, et al. , Anti-recombination function of MutSα restricts telomere extension by ALT-associated homology-directed repair, Cell Rep. 37 (2021), 110088, 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Jiricny J, The multifaceted mismatch-repair system, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 7 (2006) 335–346, 10.1038/nrm1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Panier S, Maric M, Hewitt G, Mason-Osann E, Gali H, Dai A, et al. , SLX4IP antagonizes promiscuous BLM activity during ALT maintenance, e11, Mol. Cell 76 (2019) 27–43, 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Azzalin CM, Reichenbach P, Khoriauli L, Giulotto E, Lingner J, Telomeric repeat containing RNA and RNA surveillance factors at mammalian chromosome ends, Science 318 (2007) 798–801, 10.1126/science.1147182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Schoeftner S, Blasco MA, Developmentally regulated transcription of mammalian telomeres by DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II, Nat. Cell Biol 10 (2008) 228–236, 10.1038/ncb1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Nergadze SG, Farnung BO, Wischnewski H, Khoriauli L, Vitelli V, Chawla R, et al. , CpG-island promoters drive transcription of human telomeres, Rna 15 (2009) 2186–2194, 10.1261/rna.1748309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Porro A, Feuerhahn S, Reichenbach P, Lingner J, Molecular dissection of telomeric repeat-containing RNA biogenesis unveils the presence of distinct and multiple regulatory pathways, Mol. Cell. Biol 30 (2010) 4808–4817, 10.1128/MCB.00460-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Arora R, Lee Y, Wischnewski H, Brun CM, Schwarz T, Azzalin CM, RNaseH1 regulates TERRA-telomeric DNA hybrids and telomere maintenance in ALT tumour cells, 5220–11, Nat. Commun 5 (2014), 10.1038/ncomms6220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Silva B, Arora R, Bione S, Azzalin CM, TERRA transcription destabilizes telomere integrity to initiate break-induced replication in human ALT cells, 3760–12, Nat. Commun 12 (2021), 10.1038/s41467-021-24097-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Chu H-P, Cifuentes-Rojas C, Kesner B, Aeby E, Lee H-G, Wei C, et al. , TERRA RNA antagonizes ATRX and protects telomeres, e16, Cell 170 (2017) 86–101, 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Montero JJ, López-Silanes I, Megías D, Fraga MF, Castells-García Á, Blasco MA, TERRA recruitment of polycomb to telomeres is essential for histone trymethylation marks at telomeric heterochromatin, 1548–14, Nat. Commun 9 (2018), 10.1038/s41467-018-03916-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].López de Silanes I, Graña O, De Bonis ML, Dominguez O, Pisano DG, Blasco MA, Identification of TERRA locus unveils a telomere protection role through association to nearly all chromosomes, 4723–13, Nat. Commun 5 (2014), 10.1038/ncomms5723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Feretzaki M, Pospisilova M, Valador Fernandes R, Lunardi T, Krejci L, Lingner J, RAD51-dependent recruitment of TERRA lncRNA to telomeres through R-loops, Nature 587 (2020) 303–308, 10.1038/s41586-020-2815-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Vohhodina J, Goehring LJ, Liu B, Kong Q, Botchkarev VV, Huynh M, et al. , BRCA1 binds TERRA RNA and suppresses R-Loop-based telomeric DNA damage, 3542–16, Nat. Commun 12 (2021), 10.1038/s41467-021-23716-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Ouyang J, Yadav T, Zhang J-M, Yang H, Rheinbay E, Guo H, et al. , RNA transcripts stimulate homologous recombination by forming DR-loops, Nature 594 (2021) 283–288, 10.1038/s41586-021-03538-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Maris JM, Recent advances in neuroblastoma, N. Engl. J. Med 362 (2010) 2202–2211, 10.1056/NEJMra0804577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Peifer M, Hertwig F, Roels F, Dreidax D, Gartlgruber M, Menon R, et al. , Telomerase activation by genomic rearrangements in high-risk neuroblastoma, Nature 526 (2015) 700–704, 10.1038/nature14980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Ackermann S, Cartolano M, Hero B, Welte A, Kahlert Y, Roderwieser A, et al. , A mechanistic classification of clinical phenotypes in neuroblastoma, Science 362 (2018) 1165–1170, 10.1126/science.aat6768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Koneru B, Lopez G, Farooqi A, Conkrite KL, Nguyen TH, Macha SJ, et al. , Telomere maintenance mechanisms define clinical outcome in high-risk neuroblastoma, Cancer Res 80 (2020) 2663–2675, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Zeineldin M, Federico S, Chen X, Fan Y, Xu B, Stewart E, et al. , MYCN amplification and ATRX mutations are incompatible in neuroblastoma, Nat. Commun 11 (2020) 913–920, 10.1038/s41467-020-14682-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Qadeer ZA, Valle-Garcia D, Hasson D, Sun Z, Cook A, Nguyen C, et al. , ATRX in-frame fusion neuroblastoma is sensitive to EZH2 inhibition via modulation of neuronal gene signatures, e9, Cancer Cell 36 (2019) 512–527, 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Koneru B, Farooqi A, Nguyen TH, Chen WH, Hindle A, Eslinger C, et al. , ALT neuroblastoma chemoresistance due to telomere dysfunction-induced ATM activation is reversible with ATM inhibitor AZD0156, Sci. Transl. Med 13 (2021), 10.1126/scitranslmed.abd5750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].George SL, Lorenzi F, King D, Hartlieb S, Campbell J, Pemberton H, et al. , Therapeutic vulnerabilities in the DNA damage response for the treatment of ATRX mutant neuroblastoma, EBioMedicine 59 (2020), 102971, 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Fazal-Salom J, Bjerke L, Carvalho D, Boult J, Mackay A, Pemberton H, et al. , PDTM-33. ATRX loss confers enhanced sensitivity to combined parp inhibition and radiotherapy in paediatric glioblastoma models, Neuro-Oncol. 20 (2018) vi210–vi211. [Google Scholar]

- [105].Mukherjee J, Pandita A, Kamalakar C, Johannessen T-C, Ohba S, Tang Y, et al. , A subset of PARP inhibitors induces lethal telomere fusion in ALT-dependent tumor cells, Sci. Transl. Med 13 (2021), 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc7211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Flynn RL, Cox KE, Jeitany M, Wakimoto H, Bryll AR, Ganem NJ, et al. , Alternative lengthening of telomeres renders cancer cells hypersensitive to ATR inhibitors, Science 347 (2015) 273–277, 10.1126/science.1257216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Laroche-Clary A, Chaire V, Verbeke S, Algéo M-P, Malykh A, Le Loarer F, et al. , ATR inhibition broadly sensitizes soft-tissue sarcoma cells to chemotherapy independent of alternative lengthening telomere (ALT) status, –7488, Sci. Rep 10 (2020) 7488, 10.1038/s41598-020-63294-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Deeg KI, Chung I, Bauer C, Rippe K, Cancer cells with alternative lengthening of telomeres do not display a general hypersensitivity to ATR inhibition, Front Oncol. 6 (2016) 186, 10.3389/fonc.2016.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Liang J, Zhao H, Diplas BH, Liu S, Liu J, Wang D, et al. , Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screen reveals selective vulnerability of ATRX-mutant cancers to WEE1 inhibition, Cancer Res 80 (2020) 510–523, 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Burgess RJ, Zhang Z, Histone chaperones in nucleosome assembly and human disease, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 20 (2013) 14–22, 10.1038/nsmb.2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Segura-Bayona S, Villamor-Payà M, Attolini CS-O, Koenig LM, Sanchiz Calvo M, Boulton SJ, et al. , Tousled-like kinases suppress innate immune signaling triggered by alternative lengthening of telomeres, Cell Rep. 32 (2020), 107983, 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Bakail M, Gaubert A, Andreani J, Moal G, Pinna G, Boyarchuk E, et al. , Design on a rational basis of high-affinity peptides inhibiting the histone chaperone ASF1, e10, Cell Chem. Biol 26 (2019) 1573–1585, 10.1016/j.chembiol.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Gasparian AV, Burkhart CA, Purmal AA, Brodsky L, Pal M, Saranadasa M, et al. , Curaxins: anticancer compounds that simultaneously suppress NF-κB and activate p53 by targeting FACT, 95ra74–95ra74, Sci. Transl. Med 3 (2011), 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Han M, Napier CE, Frölich S, Teber E, Wong T, Noble JR, et al. , Synthetic lethality of cytolytic HSV-1 in cancer cells with ATRX and PML deficiency, J. Cell. Sci 132 (2019), jcs222349, 10.1242/jcs.222349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Episkopou H, Diman A, Claude E, Viceconte N, Decottignies A, TSPYL5 depletion induces specific death of ALT cells through USP7-dependent proteasomal degradation of POT1, e6, Mol. Cell 75 (2019) 469–482, 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Idilli AI, Segura-Bayona S, Lippert TP, Boulton SJ, A C-circle assay for detection of alternative lengthening of telomere activity in FFPE tissue, STAR Protoc. 2 (2021), 100569, 10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Claude E, de Lhoneux G, Pierreux CE, Marbaix E, de Ville de Goyet M Boulanger C, et al. , Detection of alternative lengthening of telomeres mechanism on tumor sections, 32–16, Mol. Biomed 2 (2021), 10.1186/s43556-021-00055-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Frank L, Rademacher A, Mücke N, Tirier SM, Koeleman E, Knotz C, et al. , ALT-FISH quantifies alternative lengthening of telomeres activity by imaging of single-stranded repeats, Nucleic Acids Res (2022), 10.1093/nar/gkac113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Chen Y-Y, Dagg R, Zhang Y, Lee JHY, Lu R, Martin La Rotta N, et al. , The C-circle biomarker is secreted by alternative-lengthening-of-telomeres positive cancer cells inside exosomes and provides a blood-based diagnostic for ALT activity, Cancers (Basel) 13 (2021) 5369, 10.3390/cancers13215369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]