Abstract

Down-regulation of the Th2-like response induced by ovalbumin-alum (OVA/alum) immunization by heat-killed Brucella abortus was not reversed by anti-IL-12 antibody treatment or in gamma interferon (IFN-γ) knockout mice, suggesting that induction of Th1 cytokines was not the only mechanism involved in the B. abortus-mediated inhibition of the Th2 response to OVA/alum. The focus of this study was to determine whether an alternative pathway involves alteration in expression of costimulatory molecules. First we show that the Th2-like response to OVA/alum is dependent on B7.2 interaction with ligand since it can be abrogated by anti-B7.2 treatment. Expression of costimulatory molecules was then studied in mice immunized with OVA/alum in the absence or presence of B. abortus. B7.2, but not B7.1, was up-regulated on mouse non-T and T cells following immunization with B. abortus. Surprisingly, B. abortus induced down-regulation of CD28 and up-regulation of B7.2 on murine CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. These effects on T cells were maximal for CD28 and B7.2 at 40 to 48 h and were not dependent on interleukin-12 (IL-12) or IFN-γ. On the basis of these results, we propose that the IL-12/IFN-γ-independent inhibition of Th2 responses to OVA/alum is secondary to the effects of B. abortus on expression of costimulatory molecules on T cells. We suggest that down-regulation of CD28 following activation inhibits subsequent differentiation of Th0 into Th2 cells. In addition, decreased expression of CD28 and increased expression of B7.2 on T cells would favor B7.2 interaction with CTLA-4 on T cells, and this could provide a negative signal to developing Th2 cells.

Previously, we and others have shown that the heat-inactivated gram-negative bacterium Brucella abortus in mice (in vitro and in vivo) and in humans (in vitro) promotes T-independent antibody responses (3, 13, 14, 29, 39) and production of the Th1 cytokines interleukin-12 (IL-12) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and could serve as a potential carrier for vaccine development in situations requiring a strong Th1-like response for protection against infection (39, 43, 51). As a consequence of Th1 differentiation, B. abortus induces immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) antibodies and cytotoxic T-cell responses in mice (13, 26).

Recently we demonstrated that B. abortus has the ability to abrogate the antigen-specific, IgE-mediated allergic recall response to ovalbumin (OVA) adsorbed to alum (OVA/alum) in vivo when injected together with OVA/alum at the primary immunization (38). The presence of B. abortus in the inoculum increases specific anti-OVA IgG2a and decreases IgE antibodies in this system. This effect of B. abortus on isotype switching correlates with an increase in IFN-γ-producing cells and a decrease in IL-4 producing cells in recall responses to OVA/alum (38). Thus, B. abortus has the ability to alter the cytokine profile from Th2- to Th1-like in memory responses when injected together with OVA/alum at the time of primary immunization. Anti-IL-12 antibody treatment caused a 10-fold decrease in anti-OVA IgG2a levels but did not reverse the ability of B. abortus to inhibit IgE responses to OVA/alum (38), in agreement with previous studies that showed that B. abortus could block polyclonal IgE responses in a partially IFN-γ independent fashion (9). This finding suggested that an additional mechanism, i.e., different from induction of Th1 cytokines, was involved in the B. abortus-mediated inhibition of IgE memory responses to OVA/alum.

Costimulatory signals are important in the activation of T cells to proliferate and secrete cytokines. These signals are delivered by interaction between B7.1 and B7.2 molecules, expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APC), with CD28 or CTLA-4 on T cells (1, 4, 8, 17, 20, 22, 28, 35, 41). More recently, it was shown that CTLA-4 is important for delivering negative signals to T cells (8, 21, 23, 28, 33, 46). It has further been suggested that B7.1 and B7.2 molecules preferentially costimulate production of different cytokines. In some systems, B7.1 elicits Th1 and B7.2 evokes release of Th2 cytokines (6, 11, 12, 16, 22, 24, 34, 37, 40, 42).

It was shown that B7 molecules could be expressed not only on APC but also on T cells (2, 15, 36). The function of these molecules on T cells is not understood. However, in the case of human T cells, this effect may be associated with antigen presentation since human T cells, unlike their murine counterparts, express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and can act as APC (48, 49).

It was shown in our laboratory that B. abortus induces an increase in the expression of B7.1 and B7.2 molecules on human monocytes, constituting evidence that B. abortus can directly activate human APC (50). In addition, B. abortus induces IL-12 production from human monocytes in vitro (50) and mouse spleen cells in vivo (38, 43). One of the major constituents of B. abortus is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and LPS was previously found to induce expression of B7 molecules on human monocytes (50).

Since the mechanisms underlying the ability of B. abortus to convert a Th2 response to a Th1 response in the OVA/alum system are not completely understood and since treatment with anti-IL-12 antibody did not alter the ability of B. abortus treatment to inhibit IgE responses (38), we postulated that the B. abortus effect on OVA/alum responses may be mediated by costimulatory signals which would favor a Th1 rather than a Th2 response. Since Th2 responses appeared to be more dependent on B7.2 interaction with CD28, we predicted that B. abortus treatment may interfere with this interaction or favor the B7.1 interaction with CD28. In this work, we studied B7.1, B7.2, and CD28 expression in mice immunized with OVA/alum alone or in conjunction with B. abortus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) were used at 8 to 12 weeks of age; IFN-γ knockout (KO) mice on a BALB/c background (Jackson Laboratory) were used at 8 to 16 weeks of age. All animals were used in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal use and care.

Immunizations.

Female BALB/c mice were immunized intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 2 μg of chicken OVA fraction V (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in 0.5 ml of Al(OH)3 (OVA/alum). Heat-inactivated B. abortus (Department of Agriculture, Ames, Iowa) was injected i.p. at 108 organisms per mouse. B. abortus-OVA conjugate (contains 2 μg of OVA and 108 B. abortus organisms per 0.2 ml) was injected i.p., 0.2 ml per mouse. The method of conjugation was described previously (38). In some experiments, B. abortus and OVA/alum were injected simultaneously (BA+OVA/alum immunization).

Anti-IL-12 sheep antibody (gift from Genetics Institute, Cambridge, Mass.) was injected i.p. at a dose of 200 μg on day -1 and 200 μg on the day of immunization with OVA/alum. Anti-B7.2 rat antibody (gift from Peter Perrin) was injected i.p. at a dose of 100 μg on day -1 and on the day of immunization. Control mice were injected with sheep or rat IgG (Rockland Inc., Gilbertsville, Pa.).

Cell preparations.

Spleens were removed from mice 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after injection. Pooled spleen single cell suspensions for each time point were made; erythrocytes were lysed with ACK lysing buffer (Biowhittaker), washed, and analyzed. No fewer than four mice per group were analyzed.

Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry.

For immunofluorescence staining, 106 cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate- and phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD28, B7.1, B7.2, and CTLA-4 (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) for 1 h at 4°C. After incubation, cells were washed twice and analyzed by using a FACScan flow cytometer and Lysis II software (Becton Dickinson, Torreyana, Calif.) Propidium iodide was used to identify and exclude dead cells.

To analyze T-cells, non-T-cells, and T-cell subsets for the expression of B7.1, B7.2, or CD28, two-color immunofluorescence staining was performed, and gates were set such that only positively or negatively stained cells on one axis, i.e., CD3+, CD3−, CD4+, and CD8+ were analyzed for fluorescence, with B7.1, B7.2, or CD28 analyzed on the other axis. For control staining, isotype-matched antibodies were used. The median channel fluorescence (MCF) was calculated from linear scales, and ΔMCF represents the MCF for a particular treatment after subtraction of the MCF for the isotype-matched control.

Detection of antigen-specific immunoglobulins in serum.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for IgG1 and IgG2a were performed as previously described (38). Briefly, 96-well Immulon 4 plates (Dynatech, Chantilly, Va.) were coated with 0.2 mg of chicken OVA fraction V (Sigma) per ml in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6). Plates were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Serum samples were plated in serial two-fold dilutions. After overnight incubation at 4°C, plates were washed and anti-mouse heavy-chain (γ2a or γ1) globulin conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, Ala.) was added at 1/500 dilution. Plates were developed with diethanolamine buffer and phosphatase substrate tablets (Kierkegaard & Perry, Gaithersburg, Md.). Results were considered positive if the optical density exceeded the mean + 2 standard deviations of the optical density of preimmune serum from untreated mice for each plate. The method for determination of OVA-specific IgE was kindly provided by Gajewzcyk (11a). Immulon 4 plates were coated with 100 μl of rabbit anti-OVA antiserum (2 μg/ml) in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) and incubated overnight at 4°C. After four washes with PBS–.05% Tween 20 plates were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 3 h at 37°C. After washing, OVA at 10 μg/ml was added, and plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C or overnight at 4°C. Serum samples were then added in two-fold serial dilutions. After incubation at 37°C for 3 h, plates were washed and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse IgE (Pharmingen) was added at 1/1,500 dilution. Plates were developed after 3 h at 37°C with a phosphatase substrate as described above.

ELISPOT assay.

The frequency of IFN-γ-secreting cells was determined by enzyme-linked spot (ELISPOT) assay (38, 44). Briefly, Immulon 2 plates (Dynatech), were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl of the anti-IFN-γ antibody (Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.) at 10 μg/ml in PBS. After washing, wells were blocked for 1 h at 37°C with 200 μl of RPMI 1640–10% fetal calf serum (FCS) per well. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens of mice injected with soluble OVA (10 μg/ml) 4 days prior to ELISPOT assay. Cells were plated for ELISPOT assay and serially diluted twofold. Plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The wells were then washed three times with PBS and three times with PBS–0.05% Tween 20. Biotinylated anti-IFN-γ (Pharmingen) was added at 1 μg/ml in 100 μl of PBS–0.05% Tween 20–5% FCS per well. Plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day plates were washed as before, and streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Pharmingen) at 1/1,500 was added at 100 μl/well. After a 3-h incubation at 37°C, spots in each well were developed with 100 μl of the substrate, 5-bromo-4-chloroindolyl phosphate (Sigma) at 1 mg/ml, dissolved in 0.1 M 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol buffer (Sigma)–0.6% SeaPlaque agarose (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine). Agarose and buffer were boiled and then cooled to 50°C before addition of substrate, which was dissolved gradually in a 50°C water bath, with intermittent swirling. After cooling, plates were left covered and stationary overnight. On the following day, spots were enumerated in each well, using a dissecting microscope. As a positive control, cells were stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma) and added at 5 ng/ml with 1 μM ionomycin, (Calbiochem-Behring Corp., San Diego, Calif.). The investigator was blinded as to the groups being counted.

In vitro culture.

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from naive mice. Cells were cultured at 106 per ml in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO, Grand Island, N.Y.)–5% FCS (HyClone, Logan, Utah) for 40 h in microtiter plates in the presence of air and 5% CO2 and at 37°C. The cells were stimulated by PBS, OVA (50 μg/ml), B. abortus-OVA (108 organisms per ml), and anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml; Pharmingen).

Statistics.

Experiments were repeated at least three times, and each mouse group for each treatment consisted of at least four mice. Representative experiments were used only when all experiments showed similar results. Student’s t test was used to compare groups and generate P values when appropriate.

RESULTS

The in vivo Th2 response to OVA/alum but not the Th1 response to B. abortus is sensitive to blocking by anti-B7.2 antibody treatment.

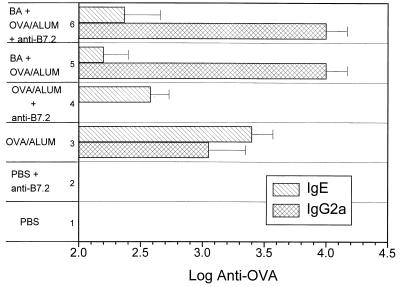

The dependence of Th2 responses on B7.2 costimulation has been shown in several systems (7, 11, 25, 32). It is known that injection of OVA/alum in vivo induces Th2-like response in mice in terms of cytokine production and isotype patterns (38). We demonstrated recently that in vivo administration of B. abortus together with OVA/alum can alter OVA-specific responses in this system from Th2-like to Th1-like (38). To determine what role B7.2 interactions play in Th1 and Th2 responses in the OVA/alum system, we treated OVA/alum- and BA+OVA/alum-immunized mice with anti-B7.2 antibody. OVA/alum alone induced IL-4-dependent IgE but not IgG2a, whereas BA+OVA/alum elicited mainly IFN-γ-dependent IgG2a and no IgE. Treatment with anti-B7.2 antibody decreased the Th2-cytokine-dependent antibody response to OVA/alum (IgE; P <0.05) (Fig. 1). In contrast, the ability of B. abortus to convert the OVA/alum response from Th2-like to Th1-like (i.e., increased IgG2a and decreased IgE) was not affected by anti-B7.2 treatment (Fig. 1). These data support the notion that Th2 development requires B7.2-CD28 interaction whereas Th1 differentiation induced by B. abortus does not.

FIG. 1.

The Th2-like response to OVA/alum is dependent on signaling via B7.2. BALB/c mice were immunized with PBS, OVA/alum, or BA+OVA/alum in the presence of anti-B7.2 or control rat antibody. The mice were boosted 1 month later and bled 10 days after the last injection. Sera from these bleeds were assayed by ELISA for IgG2a and IgE antibodies specific for OVA.

B. abortus immunization in vivo induces expression of B7.2 but not B7.1 molecules on splenic non-T and T cells.

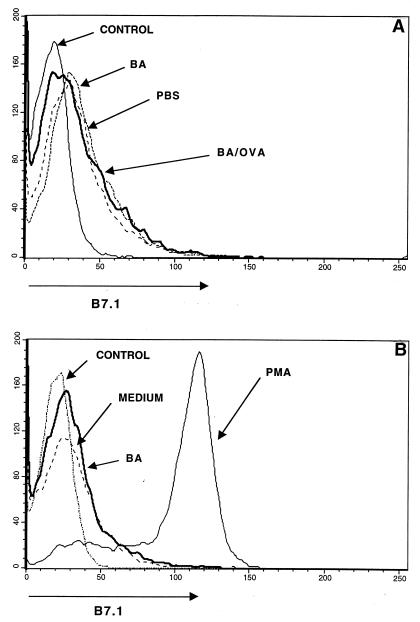

Since the Th2-like response to OVA/alum was B7.2 dependent, we reasoned that the ability of B. abortus to switch the in vivo OVA/alum response from Th2-like to Th1-like was possibly a consequence of B. abortus altering the expression of B7 molecules on APC. We compared the levels of expression of B7.1 and B7.2 on the surface of spleen cells from mice which were immunized with OVA/alum in the absence or presence of B. abortus. As shown in Fig. 2A, spleen cells from mice immunized with B. abortus alone (ΔMCF = 3) or in combination with OVA/alum (ΔMCF = 6) did not show higher levels of B7.1 expression on the surface compared with control mice injected with PBS (ΔMCF = 2). This was not due to lack of staining with the anti-B7.1 antibody, since in vitro PMA-stimulated spleen cells (ΔMCF = 85) clearly showed up-regulation of B7.1 on mouse spleen cells compared to cells treated with medium alone (ΔMCF = 2) (Fig. 2B). Thus, the effect of B. abortus on switching the OVA/alum response from Th2- to Th1-like is unlikely to be due to an increased expression of B7.1 on spleen cells.

FIG. 2.

B. abortus alone and as a conjugate with OVA does not affect B7.1 expression on mouse spleen cells. BALB/c mice were injected with PBS, B. abortus (BA), or B. abortus-OVA (BA/OVA); spleen cells were removed at 48 h, stained with anti-B7.1, and analyzed by flow cytometry (A). (B) Staining of mouse spleen cells after 48 h of stimulation in vitro with medium, B. abortus, or PMA plus ionomycin. The control profile is that obtained when an isotype-matched antibody was added.

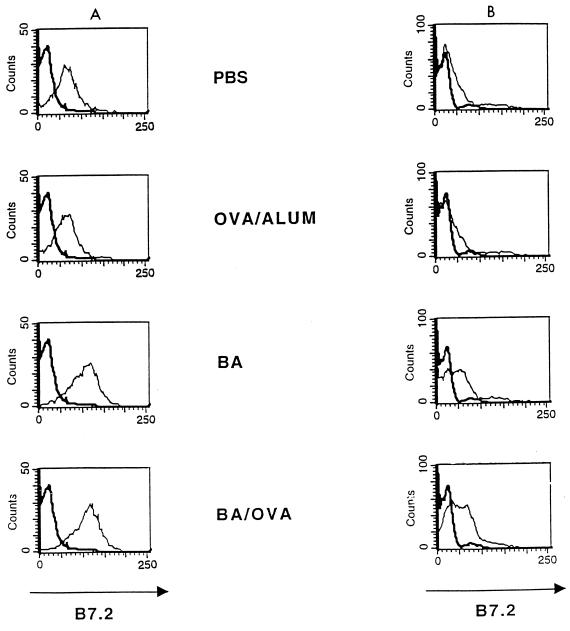

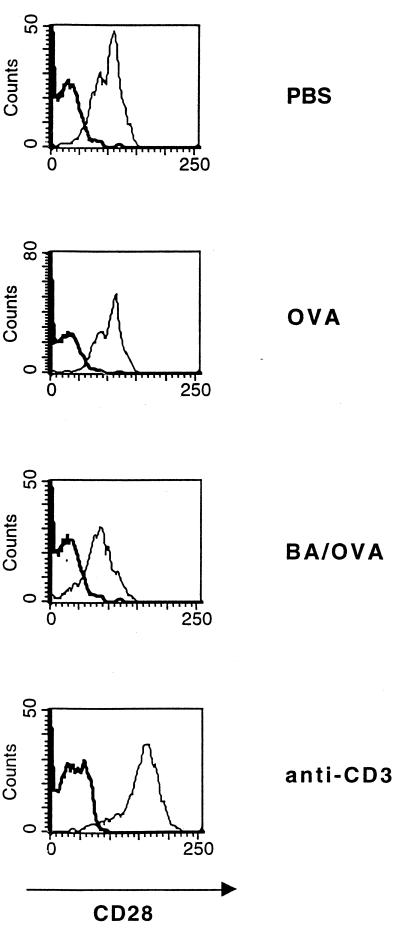

Mice immunized with B. abortus alone or in the presence of OVA/alum demonstrated a higher level of expression of B7.2 than of B7.1 on spleen cells (data not shown). Expression of B7.2 on T and non-T cells was examined by double staining (Fig. 3). Maximal increase in expression of B7.2 on non-T cells was seen at 24 h (ΔMCF of 48 for PBS, 44 for OVA/alum, 88 for B. abortus, and 93 for B. abortus-OVA), with a return to background at 96 h (only 24-h staining is shown in Fig. 3). The increased expression of B7.2 on non-T cells could not explain the ability of B. abortus to down-regulate the Th2 response to OVA/alum, since B7.2 was required for the OVA/alum response.

FIG. 3.

Expression of B7.2 molecules on the surface of T cells is increased by in vivo administration of B. abortus (BA) or B. abortus-OVA (BA/OVA) to BALB/c mice. Spleen cells were removed 24 h after injection. The data represent expression of B7.2 molecules on the surface of non-T cells (A) and of T cells (B).

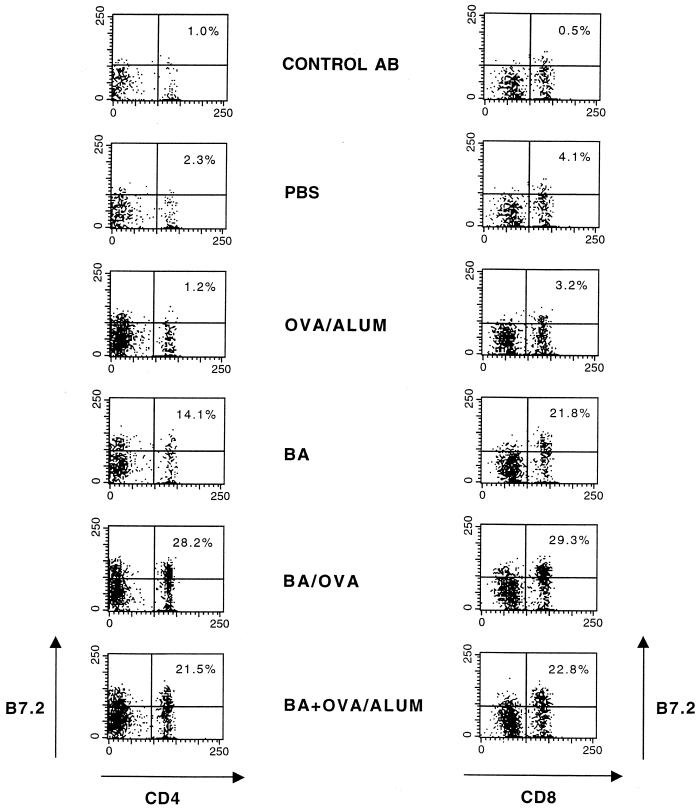

In the case of T cells, B7.2 expression was also increased at 24 h in the presence of B. abortus alone or together with OVA/alum compared with mice immunized with OVA/alum alone (ΔMCF of 10 for PBS, 12 for OVA/alum, 30 for B. abortus, and 41 for B. abortus-OVA). Maximal expression of B7.2 on T cells following treatment with B. abortus or B. abortus-OVA occurred at approximately 40 h (data not shown). To determine whether increased B7.2 following B. abortus occurred in T-cell subsets, CD4+ and CD8+ cells were examined for B7.2 expression following immunization with either B. abortus, B. abortus-OVA or BA+OVA/alum in vivo at 40 h. As shown in Fig. 4, increased percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells stained more brightly for B7.2 after these stimuli than in mice immunized with PBS or OVA/alum. When histograms were generated (data not shown) and cells were gated as CD4+ or CD8+, increases in ΔMCF were seen after immunization with either B. abortus, B. abortus-OVA or BA+OVA/alum in vivo such that the ΔMCF for CD4+ T cells was 23, 66, or 70, respectively, whereas for CD8+ cells the ΔMCF was 45, 68, or 77, respectively. Following treatment with PBS and OVA/alum, the ΔMCF was <5. Thus, both T-cell subsets displayed similar increases in B7.2 expression following immunization with B. abortus, B. abortus-OVA, or BA+OVA/alum.

FIG. 4.

Expression of B7.2 molecules on the surface of T-cell subsets is increased by in vivo administration of B. abortus or B. abortus-OVA. BALB/c mice were injected with control antibody (AB), PBS, OVA/alum, B. abortus (BA), B. abortus-OVA (BA/OVA), or BA+OVA/alum. Spleen cells were removed after 48 h, and expression of B7.2 molecules on CD4+ and CD8+ cells was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The number shown in each upper right quadrant represents the percentage of CD4+ or CD8+ cells that are B7.2 positive.

This effect of B. abortus on increased T-cell expression of B7.2 was unexpected and did offer a possible explanation for the effects of B. abortus on inhibiting Th2 responses to OVA/alum. B7.2 on T cells was shown not to interact with CD28 on T cells but did retain binding to CTLA-4 (15). Since CTLA-4 binding can generate a negative signal (10, 23, 28, 33, 46), this could explain how B. abortus inhibits Th2 cell differentiation.

B. abortus down-regulates the expression of CD28 on splenic T cells.

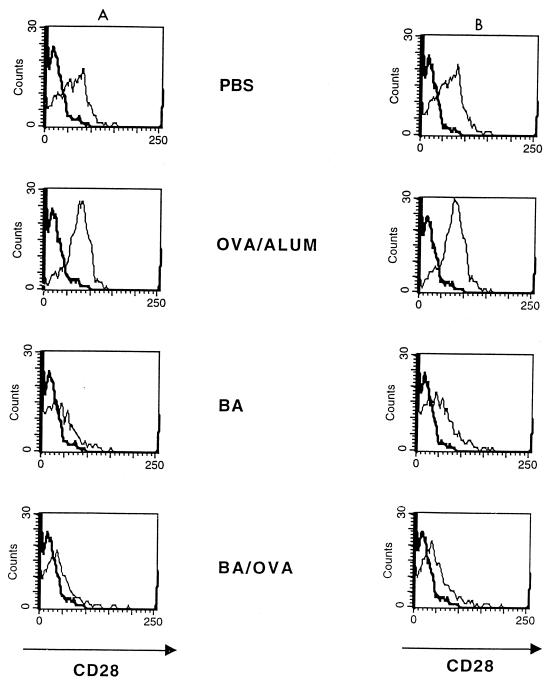

Since B. abortus could also influence Th2 responses by down-regulating expression of CD28 on T cells, surface expression of this molecule following B. abortus treatment was studied. As shown in Fig. 5, at 40 h, B. abortus treatment alone caused a decrease in CD28 expression; this effect was also seen when OVA/alum was injected together with B. abortus (ΔMCF for CD4+ cells of 42 for PBS, 52 for OVA/alum, 11 for B. abortus, and 12 for B. abortus-OVA; corresponding ΔMCF for CD8+ cells, 50, 66, 17, and 16). The effect of BA on CD28 expression was observed at 24 h, was maximal at 48 h, and was no longer apparent by 72 h (kinetic data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Expression of CD28 on the surface of murine spleen cells is decreased in the presence of B. abortus and B. abortus-OVA. BALB/c mice were injected with PBS, OVA/alum, B. abortus (BA), and B. abortus-OVA (BA/OVA). Spleen cells were removed after 48 h, and expression of CD28 on the surface of CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T cells was determined by flow cytometry.

This experiment was repeated in vitro, using anti-CD3 treatment as a positive control to increase CD28 expression on T cells. Figure 6 shows that after 40 h, B. abortus-OVA decreased CD28 expression, whereas anti-CD3 has the opposite effect (ΔMCF of 85 for PBS, 82 for OVA, 48 for B. abortus-OVA, and 107 for anti-CD3). Anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies were used to stain the T cells because they were coated by anti-CD3 during the in vitro culture period. In this same experiment, B. abortus-OVA stimulation increased expression of B7.2 and CD69 on the T cells (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

In contrast to anti-CD3, B. abortus stimulation in vitro down-regulates CD28 expression on T cells. Spleen cells were placed in culture at 106 cells per ml and stimulated with PBS, OVA, B. abortus-OVA (BA/OVA), and anti-CD3 for 40 h. They were then stained with antibodies against CD28, CD4, and CD8. The CD4 and CD8 cells were gated and assessed for CD28 expression.

The effect of B. abortus, and more importantly of B. abortus-OVA, on down-regulating CD28 expression could explain the ability of B. abortus to switch the OVA/alum response from Th2 to Th1 since the Th2 response is dependent on B7.2-CD28 interaction. Furthermore, decreased surface CD28 may favor the interaction of B7.2 on APC or on T cells with CTLA-4 on T cells, which may deliver a negative signal (21, 23, 28, 33, 46).

B. abortus-induced alteration in the expression of costimulatory molecules on T cells is independent of IL-12 and IFN-γ.

We and others have previously shown that B. abortus induces IL-12 mRNA and protein expression in mice (38, 43) and in humans (51). It has been shown that IL-12 increases expression of B7 on B cells (6, 47) and that IL-12 is involved in costimulation of T cells (30). Therefore, it was of interest to determine whether IL-12 played a role in the observed effects of B. abortus on costimulatory molecules. This was investigated by injecting anti-IL-12 together with B. abortus in the presence and absence of OVA/alum and assessing expression of costimulatory molecules on spleen cells.

To verify that anti-IL-12 treatment was effective, we tested its ability to block differentiation of Th1 cells following BA+OVA/ALUM immunization of mice. Anti-IL-12 treatment at the time of immunization decreases the production of IFN-γ-secreting spleen cells responding to OVA in recall responses from 280 ± 74 to background levels (P < 0.05). Mice from the same experiment were examined for costimulatory molecule expression. When B. abortus was added to the OVA/alum inoculum, B7.2+ expression on T cells (ΔMCF) was increased compared to OVA/alum (51 versus 36; Table 1). An increase in B7.2+ T cells was also observed following anti-IL-12 administration to BA+OVA/ALUM-immunized mice, indicating that IL-12 was not required for T-cell up-regulation of B7.2. Administration of anti-IL-12 did not affect the decrease of CD28 expression induced by BA+ OVA/ALUM immunization (Table 1), indicating that the effect of B. abortus on CD28 down-regulation on T cells is also not dependent on the presence of IL-12. Taken together, these results suggest that B. abortus is capable of altering expression of costimulatory molecules on T cells in an IL-12-independent manner.

TABLE 1.

Effects of anti IL-12 on expression of costimulatory molecules

| Treatment | ΔMCFb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD28 on T cells | B7.2 on T cells | B7.2 on non-T cells | |

| OVA/alum + IgG | 48 | 36 | 44 |

| BA+OVA/alum + IgG | 19 | 51 | 88 |

| BA+OVA/alum + anti IL-12 | 25 | 59 | 68 |

BALB/c mice were immunized with the antigens shown, and spleen cells were assessed for expression of CD28 or B7.2 40 h later.

ΔMCF is the MCF for a particular marker after subtraction of the MCF obtained from the background staining with the isotype-matched control antibody. MCFs for the isotype-matched antibody for each treatment were similar. T cells were gated as cells positive for anti-CD3 staining; non-T cells were gated as CD3− cells.

In contrast, anti-IL-12 treatment decreased non-T-cell expression of B7.2 to about 77% of that in the presence of control IgG, indicating that non-T-cell expression of B7.2 elicited by B. abortus was at least partially dependent on IL-12.

Anti-IL-12 treatment blocks IL-12 effects such as development of cells that secrete IFN-γ. To confirm that the effects of B. abortus and B. abortus-OVA on T cells are independent of IFN-γ, the experiments were repeated in IFN-γ KO mice (Table 2). Following B. abortus or B. abortus-OVA immunization T cells from IFN-γ KO mice were capable of up-regulating B7.2 expression, and CD4+ and CD8+ cells exhibited decreased CD28 expression. Thus, the alteration of costimulatory molecules on T cells mediated by B. abortus or B. abortus-OVA, namely, an increase in B7.2 expression and a decrease in CD28 expression, was the same in IFN-γ KO mice as in wild-type mice. Importantly, experiments performed in parallel showed that IgE anti-OVA titers in the IFN-γ KO mice were inhibited by B. abortus (501 ± 13 versus <100; P < 0.05). These results differ from those observed with polymerized OVA, which inhibits IgE responses to OVA/alum, but this inhibition is dependent on IFN-γ (18). Since IFN-γ secretion is mainly dependent on IL-12 in our system, these results are in accord with those obtained with anti-IL-12 and support the notion that an IL-12/IFN-γ-independent pathway is involved in the B. abortus-mediated alteration of costimulatory molecule expression on T cells and inhibition of IgE anti-OVA responses.

TABLE 2.

Expression of costimulatory molecules in IFN-γ KO micea

| Treatment | ΔMCFb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD28 on CD4+ cells | CD28 on CD8+ cells | B7.2 on T cells | |

| OVA/alum | 46 | 62 | 15 |

| B. abortus | 20 | 8 | 29 |

| B. abortus-OVA | 20 | 7 | 30 |

IFN-γ KO mice were immunized with the antigens shown, and spleen cells were assessed for expression of CD28 or B7.2 40 h later.

ΔMCF is the MCF for a particular marker after subtraction of the MCF obtained from the background staining with the isotype-matched control antibody. MCFs for the isotype-matched antibody for each treatment were similar. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were gated by using anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibodies; T cells were gated by staining with anti-CD3.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we showed that a strong Th1 stimulus, provided by B. abortus, was capable of suppressing the Th2-like response to OVA/alum, that the effect of B. abortus on inhibition of IL-4 was only partially reversed by anti-IL-12 antibody treatment, and that inhibition of IgE in the presence of B. abortus occurred even after anti-IL-12 treatment (38). Thus, the ability of B. abortus to induce a Th1-like cytokine pattern (IL-12 and IFN-γ) did not sufficiently explain the inhibitory effect of B. abortus on the Th2-like response to OVA/alum. Several studies have suggested the involvement of the costimulatory molecule B7.1 or B7.2 in directing an immune response toward a Th1 or a Th2 phenotype, respectively (7, 11, 12, 24, 27, 32). Thus, it was of interest to determine whether B. abortus exerted its effects by altering costimulatory molecule expression and whether these effects were IL-12 independent.

We show that OVA/alum responses are dependent on B7.2 interactions, because anti-B7.2 treatment blocks Th2-dependent IgE antibody recall responses to OVA/alum. In contrast, the IgG2a response to BA+OVA/alum was unaffected by anti-B7.2 antibody treatment.

Since B. abortus is a strong Th1 stimulus and inhibits the Th2 response to OVA/alum, we expected it to induce an increase in B7.1 or a decrease in B7.2 expression on APC. However, when B. abortus was administered together with OVA/alum, B7.1 expression remained unchanged whereas B7.2 expression on non-T cells increased. These findings did not explain the effect of B. abortus on down-regulating the Th2-like response to OVA/alum.

Unexpectedly, we found that B. abortus decreased CD28 and increased B7.2 on T cells maximally at 48 h. Thus, these events succeeded initial T-cell activation and may have influenced a later phase when Th0 cells are differentiating into Th1 or Th2 phenotypes. Development of Th2 responses depends on B7.2 interaction with CD28, as shown in this and previous studies (7, 11, 12, 24, 32, 45), and so the decrease in CD28 observed in the presence of B. abortus may have contributed to the B. abortus-mediated switch from Th2 to Th1. Alternatively, down-regulation of CD28 may favor interaction of B7.2 on APC with CTLA-4 on T cells. This latter interaction can provide a negative signal especially in the context of T-cell receptor (TCR) responses to OVA peptides presented by MHC class II (31, 48). The increased expression of B7.2 on T cells may also play a role in down-regulating Th2 responses. Since it has been shown that B7.2 on T cells does not bind CD28 but retains binding to CTLA-4 (15), it may deliver a negative signal via CTLA-4 and prevent Th2 responses.

The observation that there was a small but detectable IgG2a response to OVA/alum suggests that although the predominant responses to OVA/alum is Th2-like, there is a minor Th1-like component, which can be inhibited by anti-B7.2. In contrast, the IgG2a response to BA+OVA/alum not only was 1 log higher than the IgG2a response to OVA/alum but was not inhibited to any extent by anti-B7.2. The ability of B. abortus to induce IgG2a even in the presence of anti-B7.2 suggests that B. abortus, unlike OVA/alum, provides additional signals to T cells, which in terms of Th1 responses bypasses any requirement for B7.2/CD28 and counteracts any negative signaling via CTLA-4. We have shown previously that B. abortus, LPS from B. abortus, and DNA from B. abortus induce Th1-like cytokines from human and murine T cells (reference 50 and 51 and unpublished data). These stimuli, unlike OVA/alum, probably involve T-cell activation via pathways that are TCR and CD28 independent. B. abortus was previously shown to induce Th1-like responses in MHC class II KO mice, which cannot signal via TCR on CD4+ T cells (39).

The inhibition of OVA/alum and lack of inhibition of BA+OVA/alum responses may reflect the requirement of TCR activation for OVA/alum stimulation of T cells, whereas B. abortus can bypass this requirement (39). Negative signaling of T cells by CTLA-4 has been shown to operate by interfering with events downstream to TCR activation, namely, protein kinases ERK and JNK, which are required for IL-2 transcription (6).

The results of these and previous studies suggest that B. abortus, as an adjuvant or carrier, is capable of promoting Th1 responses both by inducing the Th1-like cytokines IL-12 and IFN-γ and by inhibiting emerging Th2-like responses in a manner which is independent of IL-12 and IFN-γ. We propose that the additional pathway used by B. abortus to suppress Th2 responses involves costimulatory signals and relates to the observed effects of B. abortus on T cells, which occurred after initial activation and were characterized by up-regulation of B7.2 and down-regulation of CD28.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison J P. CD28-B7 interactions in T-cell activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:414–419. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azuma M, Yssel H, Phillips J H, Spits H, Lanier L L. Functional expression of B7/BB1 on activated T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;177:845–850. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.3.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betts M, Beining P, Brunswick M, Inman J, Angus R D, Hoffman T, Golding B. Lipopolysaccharide from Brucella abortus behaves as a T-cell-independent type 1 carrier in murine antigen-specific antibody responses. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1722–1729. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1722-1729.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boise L H, Noel P J, Thompson C B. CD28 and apoptosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:620–625. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boussiotis V A, Freeman G J, Gribben J G, Daley J, Gray G, Nadler L M. Activated human B lymphocytes express three CTLA-4 counterreceptors that costimulate T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11059–11063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvo C R, Amsen D, Kruisbeek A M. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) interferes with extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) activation, but does not affect phosphorylation of T cell receptor ζ and ZAP 70. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1645–1653. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corry D B, Reiner S L, Linsley P S, Locksley R M. Differential effects of blockade of CD28-B7 on the development of Th1 or Th2 effector cells in experimental leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1994;153:4142–4148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis J H, Burden M N, Vinogradov D V, Linge C, Crowe J S. Interactions of CD80 and CD86 with CD28 and CTLA4. J Immunol. 1996;56:2700–2709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkelman F D, Katona I M, Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. IFN gamma regulates the isotypes of Ig secreted during in vivo immune response. J Immunol. 1988;140:1022–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn P W, He H, Wang Y, Wang Z, Guan G, Listman J, Perkins D L. Synergistic induction of CTLA-4 expression by costimulation with TCR plus CD28 signals mediated by increased transcription and messenger ribonucleic acid stability. J Immunol. 1997;158:4074–4081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman G J, Boussiotis V A, Anumanthan A, Bernstein G M, Ke X, Rennert P D, Gray G S, Gribben J G, Nadler L M. B7-1 and B7-2 do not deliver identical costimulatory signals, since B7-2 but not B7-1 preferentially costimulates the initial production of IL-4. Immunity. 1995;2:523–532. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Gajewzcyk, D. Personal communication.

- 12.Gause W C, Chen S J, Greenwald R J, Halvorson M J, Lu P, di Zhou X, Morris S C, Lee K P, June C H, Finkelman F D, Urban J F, Abe R. CD28 dependence of T cell differentiation of IL-4 production varies with the particular type 2 immune response. J Immunol. 1997;158:4082–4087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golding B, Inman J, Highet P, Blackburn R, Manischewitz J, Blyveis N, Angus R D, Golding H. Brucella abortus conjugated with a gp120 or V3 loop peptide derived from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 induces neutralizing anti-HIV antibodies, and the V3-Brucella abortus conjugate is effective even after CD4+ T-cell depletion. J Virol. 1995;69:3299–3307. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3299-3307.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golding B, Muchmore A V, Blaese R M. Newborn and Wiskott-Aldrich patient B cells can be activated by TNP-Brucella abortus: evidence that TNP-Brucella abortus behaves as a T-independent type 1 antigen in humans. J Immunol. 1984;133:2966–2971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenfield E A, Howard E, Paradis T, Nguyen K, Benazzo F, McLean P, Hollsberg P, Davis G, Hafler D A, Sharpe A H, Freeman G J, Kuchroo V K. B7.2 expressed by T-cells does not induce CD28-mediated costimulatory activity but retains CTLA4 binding. J Immunol. 1997;158:2025–2034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwald R J, Lu P, Halvorson M J, Zhou X, Chen S, Madden K B, Perrin P J, Morris S C, Finkelman F D, Peach R, Linsley P S, Urban J, Gause W C. Effects of blocking B7-1 and B7-2 interactions during a type 2 in vivo immune response. J Immunol. 1997;158:4088–4096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hathcock K S, Hodes R J. Role of the CD28-B7 costimulatory pathways in T cell-dependent B cell responses. Adv Immunol. 1996;62:131–166. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HayGlass K T, Stefura B P. Anti-interferon gamma treatment blocks the ability of glutaraldehyde polimerized allergens to inhibit specific IgE responses. J Exp Med. 1991;173:279–285. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu C, Chua K, Tao M, Lai Y, Wu H, Huang S, Hsieh K. Immunoprophylaxis of allergen-induced immunoglobulin E synthesis and airway hyperresponsiveness in vivo by genetic immunization. Nat Med. 1997;2:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.June C H, Bluestone J A, Nadler L M, Thompson C B. The B7 and CD28 receptor families. Immunol Today. 1994;15:321–323. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karandikar N J, Vanderlugt C L, Walunas T L, Miller S D, Bluestone J A. CTLA-4: a negative regulator of autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1996;184:783–788. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamura T, Furue M. Comparative analysis of B7-1 and B7-2 expression in Langerhans cells: differential regulation by T helper type 1 and T helper type 2 cytokines. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1913–1917. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krummel M F, Allison J P. CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J Exp Med. 1995;182:459–465. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuchroo V K, Prabhu Das M, Brown J A, Ranger A M, Zamvil S S, Sobel R A, Weiner H L, Nabavi N, Glimcher L H. B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules activate differentially the Th1/Th2 developmental pathways: application to autoimmune disease therapy. Cell. 1995;80:707–718. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kundig T M, Shahinian A, Kawai K, Mittrucker H, Sebzda E, Bachmann M F, Mak T W, Ohashi P S. Duration of TCR stimulation determines costimulatory requirement of T cells. Immunity. 1996;5:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lapham C, Golding B, Inman J, Blackburn R, Manischewitz J, Highet P, Golding H. Brucella abortus conjugated with a peptide derived from the V3 loop of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 induces HIV-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses in normal and in CD4+ cell-depleted BALB/c mice. J Virol. 1996;70:3084–3092. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3084-3092.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenschow D J, Ho S C, Sattar H, Rhee L, Gray G, Nabavi N, Herold K C, Bluestone J A. Differential effects of anti-B7-1 and anti-B7-2 monoclonal antibody treatment on the development of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1145–1155. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linsley P S. Distinct roles for CD28 and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated molecule-4 receptors during T cell activation. J Exp Med. 1995;182:289–292. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mond J J, Sher I, Mosier D E, Blaese R M, Paul W E. T-independent responses in B cell-defective CBA/N mice to Brucella abortus and to trinitrophenyl (TNP) conjugates of Brucella abortus. Eur J Immunol. 1978;8:459–463. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830080703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy E E, Terres G, Macatonia S E, Hsieh C, Mattson J, Lanier L, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Murphy K, O’Garra A. B7 and interleukin 12 cooperate for proliferation and interferon gamma production by mouse T helper clones that are unresponsive to B7 costimulation. J Exp Med. 1994;180:223–231. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nabavi N, Freeman G J, Gault A, Godfrey D, Nadler L M, Glimcher L H. Signaling through the MHC class II cytoplasmic domain is required for antigen presentation and induces B7 expression. Nature. 1992;360:266–268. doi: 10.1038/360266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natesan M, Razi-Wolf Z, Reiser H. Costimulation of IL-4 production by murine B7-1 and B7-2 molecules. J Immunol. 1996;156:2783–2791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez V L, van Parijs L, Biuckians A, Zheng X X, Strom T B, Abbas A K. Induction of peripheral T cell tolerance in vivo requires CTLA-4 engagement. Immunity. 1997;6:411–417. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prabhu Das M R, Zamvil S S, Borriello F, Weiner H L, Sharpe A H, Kuchroo V K. Reciprocal expression of costimulatory molecules, B7-1 and B7-2, on murine T cells following activation. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:207–211. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudd C E. Upstream-downstream: CD28 cosignaling pathways and T cell function. Immunity. 1996;4:527–534. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sansom D M, Hall N D. B7/BB1, the ligand for CD28, is expressed on repeatedly activated human T cells in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:295–298. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sayegh M H, Akalin E, Hancock W W, Russell M E, Carpenter C B, Linsley P S, Turka L A. CD28-B7 blockade after alloantigenic challenge in vivo inhibits Th1 cytokines but spares Th2. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1869–1874. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott D E, Agranovich I, Gober M, Golding B. Inhibition of primary and recall allergen-specific Th2-mediated responses by a Th1 stimulus. J Immunol. 1997;159:107–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott D E, Golding H, Huang L Y, Inman J, Golding B. HIV peptide conjugated to heat-killed bacteria promotes antiviral responses in immunodeficient mice. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:1263–1269. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shanafelt M S, Soderberg C, Allsup A, Adelman D, Peltz G, Lahesmaa R. Costimulatory signals can selectively modulate cytokine production by subsets of CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:1684–1690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sloan-Lancaster J, Evavold B D, Allen P M. Th2 cell clonal anergy as a consequence of partial activation. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1195–1205. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stadecker M J, Flores Villanueva P O. Accessory cell signals regulate Th-cell responses: from basic immunology to a model of helminthic disease. Immunol Today. 1994;15:571–574. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Svetic A, Jian Y C, Finkelman F D, Gause W C. Brucella abortus induces a novel cytokine gene expression pattern characterized by elevated IL-10 and interferon gamma in CD4+ T cells. Int Immunol. 1993;5:877–883. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.8.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taguchi T, McGhee J R, Coffman R L, Beagley K W, Eldridge J H, Takatsu K, Kiyono H. Detection of individual mouse spleen T cells producing IFN-gamma and IL-5 using the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. J Immunol Methods. 1990;28:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90464-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson C B. Distinct roles for the costimulatory ligands B7-1 and B7-2 in T helper cell differentiation? Cell. 1995;81:979–982. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tivol E A, Borriello F, Schweitzer A N, Lynch W P, Bluestone J A, Sharpe A H. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3:541–547. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wyss-Coray T, Mauri-Hellweg D, Baumann K, Bettens F, Grunow R, Pichler W J. The B7 adhesion molecule is expressed on activated human T cells: functional involvement in T-T cell interactions. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2175–2180. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yssel H, Schneider P V, Lanier L L. Interleukin-7 specifically induces the B7/BB1 antigen on human cord blood and peripheral blood T cells and T cell clones. Int Immunol. 1993;5:753–759. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.7.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zaitseva M, Golding H, Manischewitz J, Webb D, Golding B. Brucella abortus as a potential vaccine candidate: induction of interleukin-12 secretion and enhanced B7.1 and B7.2 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 surface expression in elutriated human monocytes stimulated by heat-inactivated Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3109–3117. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3109-3117.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaitseva M B, Golding H, Betts M, Yamauchi A, Bloom E T, Butler L E, Stevan L, Golding B. Human peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells express Th1-like cytokine mRNA and proteins following in vitro stimulation with heat-inactivated Brucella abortus. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2720–2728. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2720-2728.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]