Abstract

Enterococcus faecium is a ubiquitous opportunistic pathogen that is exhibiting increasing levels of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Many of the genes that confer resistance and pathogenic functions are localized on mobile genetic elements (MGEs), which facilitate their transfer between lineages. Here, features including resistance determinants, virulence factors and MGEs were profiled in a set of 1273 E. faecium genomes from two disparate geographic locations (in the UK and Canada) from a range of agricultural, clinical and associated habitats. Neither lineages of E. faecium , type A and B, nor MGEs are constrained by geographic proximity, but our results show evidence of a strong association of many profiled genes and MGEs with habitat. Many features were associated with a group of clinical and municipal wastewater genomes that are likely forming a new human-associated ecotype within type A. The evolutionary dynamics of E. faecium make it a highly versatile emerging pathogen, and its ability to acquire, transmit and lose features presents a high risk for the emergence of new pathogenic variants and novel resistance combinations. This study provides a workflow for MGE-centric surveillance of AMR in Enterococcus that can be adapted to other pathogens.

Impact

In the last couple of decades, Enterococcus faecium has become a major public-health concern because of its ability to acquire a diversity of antimicrobial and environmental resistance factors (the resistome) through a variety of mobile genetic elements (the mobilome). Through the deployment of a novel genomic analysis pipeline, designed to characterize genetic elements based on geography, habitat and phylogenetic relatedness, we provide evidence that movement of the E. faecium mobilome and resistome is largely unconstrained by within-species phylogeny, habitat or geography. We identify a clinically associated clonal expansion that is most likely a new ecotype with pathogenic potential and specialized to clinical and human habitats. Similar examples of niche specialization leading to population differentiation have been documented in other bacterial pathogens, and our study provides a blueprint for antimicrobial resistance surveillance and genome-based monitoring of emerging pathogen types based on evolutionary networks of the resistome and mobilome.

Data Summary

The E. faecium genomes from the UK and Alberta used in this study were first published in Gouliouris et al. [1] and Zaheer et al. [2], respectively. All accessions and associated metadata can be found in Table S1, available in the online version of this article. All software tools used in this work are freely available online. The code to reproduce the results is available at GitHub (https://github.com/beiko-lab/efaecium-niche).

Introduction

Enterococcus faecium is a ubiquitous, Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic microorganism often isolated from a variety of natural environments including soil and water, and host-associated environments including the intestinal tract of humans and animals [3–5]. The presence of E. faecium in the intestinal tract of healthy subjects led to the belief that this microbe was an innocuous commensal, with an occasional role in opportunistic infections [6]. However, following a 1986 outbreak of vancomycin-resistant strains of E. faecalis and E. faecium in a London, UK, hospital [7], since then it has become clear that this bacterium can cause grave illness in humans and readily acquire antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes through lateral gene transfer (LGT). Indeed, enterococci have the ability to share genes within an extended pool of mobile genetic elements (MGEs) [8], allowing them to serve as hubs for the transmission of AMR determinants to both Gram-positive and Gram-negative species [9]. Antimicrobial-resistant enterococci are now a leading cause of hospital-acquired bloodstream and urinary tract infections [6]. According to the World Health Organization, E. faecium is a member of a group of nosocomial pathogens called ‘ESKAPE’ [10] that have been given priority status on the list of pathogens for which new antimicrobials are urgently needed [11]. Up to the early 1990s, most nosocomial enterococcal infections were caused by E. faecalis , while E. faecium was the causative agent of only about 10 % of cases [12]. Over the past two decades, E. faecium infections have been constantly on the rise in the United States [13–15] and in Europe [16–20]. In 2021, Dadashi et al. reported that the global prevalence of E. faecium among enterococcal isolates from clinical infections was 40.6%, with 43.6 % in Asia, 38.0 % in Europe, and 36.8 % in America [21].

Lebreton et al. [22, 23] described how E. faecalis and E. faecium have emerged independently through separate events of LGT driven largely by MGEs. Specifically, in E. faecium , there is a deep split (about 3 000 years ago) between strains commonly present in the microbiota of non-human animals (clade A), which are the ancestors of most of the current clinical, and human-adapted commensal strains (clade B). This split coincides with the loss of many genes related to the catabolism of dietary carbohydrates from clade A strains and the MGE-mediated acquisition of genes encoding amino-carbohydrates typically involved in glycocalyx formation during colonization of intestinal epithelial cells [22, 23]. The authors of these studies hypothesize that this difference in tropism is a reflection of the preferred habitats between these two clades, with clade B mostly community-associated and clade A mainly with hospital-associated enterococci [24]. In studies from the UK by Gouliouris et al. [1] and Alberta, Canada (AB) by Zaheer et al. [2], isolates from agricultural environments clearly separated from clinical ones constituting two distinct clades, supporting the hypothesis that they are specialized to distinct ecological niches. This adaptation also reflects the nature of antimicrobials, heavy metals, and other selective pressures present in each niche. Gouliouris et al. also included a clear split between clade A subclades, A1 and A2, although we do not investigate these subclades in this study [1].

E. faecium is extremely apt at acquiring genes carried by MGEs including plasmids, genomic islands (GIs) and prophages. In fact, the genome plasticity that renders this micro-organism a formidable public-health threat relies mainly on a large number of multifunctional accessory genes that can be laterally transferred between distantly related strains [8]. Plasmids are generally considered the main AMR gene-carrying MGEs in enterococci [25, 26]. Arredondo-Alonso et al. proposed that plasmids could be used to ascertain the niche specificity of E. faecium [27]. However, AMR, heavy-metal resistance (HMR) and virulence factor (VF) genes have also been detected in GIs [28] and prophages [29].

Understanding the relative importance of habitat and geography in shaping the genome and corresponding resistance of E. faecium is vital for guiding antimicrobial use and AMR mitigation strategies. For this reason, we have applied a ‘One Health’ approach to our phylogenomic analysis that considers the emergence, dissemination and transmission of resistance among human, agricultural and environmental isolates. Existing surveillance systems rely heavily on phenotypic data and will benefit from whole-genome sequencing and analysis. The tools employed in this genomic study can connect phylogenetic, habitat and geographic data to the prevalence of the mobilome and associated resistance and virulence genes, improving our knowledge of AMR dynamics in Enterococcus and other pathogens. Here we examine a combined set of 1273 E. faecium genomes from the UK and Alberta, Canada isolated from multiple habitats in order to determine the relationship between habitat, geography and the occurrence and distribution of the mobilome and resistome of this opportunistic pathogen.

Methods

Genome assembly and classification

The dataset for this study encompassed 1766 genomes: 334 E. faecium genomes from Alberta, Canada [2] and 1432 from the UK [1]. These genomes originated from isolates collected from five different sources: clinical (CLIN), agriculture (AGRI), municipal wastewater (WW-MUN), agricultural wastewater (WW-AGR) and natural water sources (NWS). FASTQ files for the AB genomes were retrieved from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (BioProject PRJNA604849), and UK genomes from the European Nucleotide Archive (Table S1). The quality of the FASTQ files was determined using FastQC v0.11.8 [30]; reads were trimmed using fastp v0.23.2 and assembled with Unicycler v0.4.8 [31] using default parameters. The quality of the assemblies was assessed using quast v5.0.2 [32] (Fig. 1a). An NG50 cutoff of 30 000 bp was used to remove low-quality genomes from subsequent analysis.

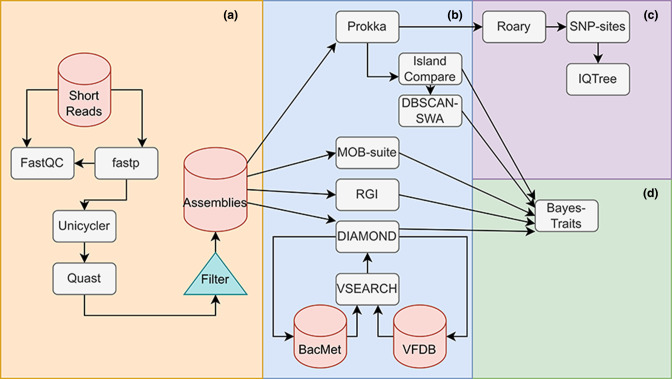

Fig. 1.

Overview of data-processing workflow. (a) Short reads were trimmed using fastp, with quality checks by FastQC before and after trimming. The reads were then assembled using Unicycler and quality checked using quast. (b) The quality-checked assemblies were annotated with Prokka, MOB-suite, RGI and DIAMOND. DIAMOND annotation was performed using the VFDB and BacMet databases. The Prokka annotations were passed to IslandCompare to infer probable GIs. The outputs from IslandCompare were passed to DBSCAN-SWA to infer probable phages. (c) Annotated contigs from Prokka were passed to Roary for pangenome calculation and core-genome alignment. The core-genome alignment’s static sites were removed using SNP-sites and the resultant alignment was passed to IQ-Tree to calculate a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree. (d) All annotated target genes and MGEs were tabulated and passed to BayesTraits for co-evolutionary analysis, performing hypothesis testing for correlated evolution between pairs of features. Acronyms used in the study are summarized in Table S8.

Pangenome characterization and generation of core-genome phylogenies

We constructed a core-genome phylogenetic tree for all of the E. faecium genomes. To do so, genomes were annotated using Prokka version 1.14.6 [33] followed by Roary v3.13.0 to construct a core-genome alignment [34]. As a reference, the genome of E. faecium DO ASM17439v2 was included and E. hirae ATCC9790 ASM27140v2 was used as an outgroup genome in the alignment. Using SNP-sites v2.5.1 a SNP alignment was produced and unambiguous nucleotide frequencies were counted [35]. The resultant SNP alignment and core-genome base frequencies were then used to generate a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree using IQTree v.2.1.4-beta [36] with the general time-reversible model with invariable site plus discrete gamma model (Fig. 1c). One thousand ultrafast bootstrap replicates and 1000 Shimodaira Hasegawa-like approximate likelihood ratio tests (SH-aLRT) were performed [37]. The phylogeny was then visualized using GrapeTree v.1.5.0 [38].

Genomes were assigned to ‘clade A’ and ‘clade B’ based on groEL gene sequences as described in Hung et al. [39]. Briefly, groEL sequences were extracted and sequences corresponding to ‘clade A’ strains E. faecium strain V68, accession MH109129 and ‘clade B’ E. faecium strain 81, accession MH109127 were added as references. Sequences were aligned using mafft v7.490 with default parameters and a maximum-likelihood tree was created with IQTree v2.1.4 using as a model unequal purine/pyrimidine rates with empirical base frequencies and a proportion of invariable sites (TN+F+I). Our assignment of the genomes to the two categories was then guided by the topology of this tree. Habitats, countries of origin, and ‘clades’ were all mapped onto the core genes-based reference tree. ‘Clade B’ was paraphyletic in the reconstructed tree, as a consequence we refer to these two categories as ‘type A’ for ‘clade A’ and ‘type B’ for ‘clade B’.

Prediction of resistance genes and virulence factors

The assembled contigs were used to detect AMR genes, HMR genes and VFs (collectively referred to as target genes) using specific databases for each gene type. AMR genes were detected with the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) (v5.1.0) for the prediction of AMR genes based on homology and SNP models from the Comprehensive Antimicrobial Resistance Database (CARD) v3.1.0 [40]. RGI stratifies matches into three categories using a curated blast bitscore cutoff that reflects known variation within a gene. Matches that score below a designated, target-specific cutoff are assigned to the ‘Loose’ category, while matches above this cutoff are assigned to the ‘Strict’ category. Exact matches are assigned to the ‘Perfect’ category. We limited our analysis to the Strict and Perfect matches. To identify HMR genes and VFs, ORFs present in the assemblies were first annotated using Prodigal v2.6.3 [41]. Subsequently, homology search with an initial E-value threshold of 10 − 20 against two databases, VFDB [42] and BacMet v2.0 [43] was conducted using diamond-blastx v0.9.36 [44]. Results were then filtered by percent identity (60%) and match coverage (60 %). Clusters of highly similar genes (> 95 %) were identified using vsearch v2.17.1 [45] (Fig. 1b).

Prediction of mobile genetic elements

To predict the presence of plasmids in our short-read assemblies, the genomes were analysed with MOB-suite3.0.0 [46] with the v2020-05-05 database. The MOB-suite pipeline scans input assemblies for contigs containing plasmid-related genes (e.g. relaxases and replicases) and repetitive regions, thereby identifying putative plasmid scaffolds. These scaffolds were compared against a database of mobility clusters (MOB-clusters) comprising pre-clustered reference plasmids. The putative plasmids were assigned to MOB-clusters by identifying the minimum Mash distance [47] to a reference plasmid. The output consisted of a single contig sequence per MOB-cluster and an annotation of their host-range predictions, mobility predictions and assignment to a replicase (rep) gene cluster. Contigs larger than 1 kb were examined for the presence of GIs with IslandCompare [48] using the reference genome E. faecium DO ASM17439v2. IslandCompare uses the reference genome to generate an alignment-based concatenated genome from each submitted draft genome. GIs are predicted by two underlying tools, IslandPath-DIMOB [49] and Sigi-HMM [50] that identify regions of the genome with anomalous dinucleotide bias (and at least one mobility gene) and differential codon usage, respectively. IslandCompare also incorporates additional functionality for ensuring the consistency of GI predictions across genomes in multi-genome datasets and clusters the predicted GIs. Following analysis, any GI predictions that corresponded to the region of the genome that could not be aligned to the reference genome were excluded. For GIs present in a relatively large proportion of genomes (> 10 %), a manual assessment was performed for genes annotated in those GIs. One GI that consisted mainly of genes involved in replication was present in nearly all genomes (1208/1273) and excluded from the analysis.

Concatenated genome files generated by IslandCompare were also used for prophage prediction via DBSCAN-SWA [51]. DBSCAN-SWA combines density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) and a sliding window algorithm (SWA) for prophage detection (Fig. 1b).

The taxonomic distribution of predicted genes and MGEs was assessed through a homology search. A reference database of predicted proteins was constructed from 20 100 complete bacterial genomes downloaded from RefSeq on 24 December 2021. DNA sequences of plasmid-associated contigs, GIs, and prophages were compared to this database using diamond-blastx version 2.0.13 with a maximum e-value of 10 − 50, 90 % identity or greater, and minimum subject coverage of 90 %. Only matches with a score of 95 % or greater relative to the best match were retained. Final filtering of results used a minimum percentage identity threshold of 99 %. The taxonomic distribution of matches was extracted from the resulting set of hits.

Sets of target genes that mapped to a given MGE were considered to be co-localized to that MGE. Co-localizations between predicted AMR, VF and HMR genes were identified using python and summarized by gene cluster. Genes that did not localize to any MGE were treated as chromosomal.

Analysis of feature abundance

We tested the hypothesis that E. faecium isolates from different sampling environments have differential abundances of AMR and HMR determinants, VFs and MGEs (hereafter referred to collectively as ‘features’). A three-way factorial ANOVA was performed to determine the extent that features were associated with habitat, geographic location, type and the interactions of these categories.

To perform ANOVA for each feature, the mean number of unique features of each type per genome was calculated. Genomes originating from NWS and WW-AGR isolates were available only in the AB isolates so these genomes were omitted. This resulted in 1203 genomes divided over 12 treatment groups (three habitats, two geographic locations, two types). To account for the unequal number of isolates in each treatment group, we used unweighted marginal mean sum of squares (SS), or type III SS, to calculate our ANOVA statistics [52]. To investigate feature frequency variance in the omitted environments, a two-way ANOVA was performed using the 303 AB genomes with ten treatment groups (five habitats and two types). Where categories were found to be significant at α=0.05, pairwise Tukey’s HSD post-hoc significance testing was performed on within-category group means (Table S2).

Coevolutionary associations of target genes and mobile genetic elements

We investigated the correlation across and within features using phylogenetic profiles. A phylogenetically informed maximum-likelihood approach was used to predict pairs of features with coordinated patterns of gain and loss, using BayesTraits version 3.0 [53]. To characterize the associations of predicted genes and MGEs across the tree, BayesTraits constructs two continuous-time Markov models for each gene/gene, gene/MGE and MGE/MGE pair based on their patterns of presence and absence: one model expresses the likelihood that the pair evolves in a correlated way, and the other the likelihood that they are gained and lost independently [54, 55]. The ratio of these two likelihoods was used to generate a P-value that reflects the statistical significance of their association. Only pairs in which both features occurred in at least three genomes were considered. We also used the BayesTraits likelihood ratio to infer the associations of specific features with type, habitat and geography categories. Because directionality of the association is not determined by BayesTraits, we infer this by referring to the distribution of the genes across the phylogenetic tree, habitat, type and geography using the presence and absence of the features.

The likelihood ratios and P-values corresponding to the gene–gene and gene–environment relationships were represented as network diagrams using Cytoscape (v3.8.2).

Results

Genome assembly and distribution

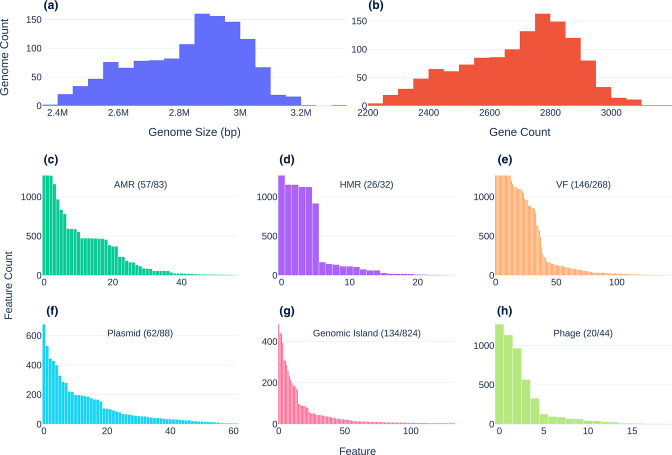

Out of 1766 sequenced genome initially selected for this study, 1273 genome assemblies (i.e. 303 from AB and 970 from the UK) that passed quality-control measures (NG50>=30 000) were selected for further analysis. The NG50 values of accepted genomes ranged from 30 088 to 46 7 1 70 bp, with a mean of 148 contigs (range: 18 to 304). Assembly sizes varied from 2 3 73 576 bp to 3 301 308 bp with a mean value of 2 8 30 264 bp (Fig. 2a) and with a mean GC content of 37.8 % (range from 37.25–38.49 %). The pangenome of the 1273 E. faecium genomes consisted of 26 246 genes (Table S3), including 1101(4.2 %) present in 99–100 % of the genomes (the core genome); 212(0.8 %) in 95–99 % of genomes (the ‘soft core’ genome); 2207 genes (8.4 %) in the ‘shell’ genome (15–95 % of genomes), and 22 726 genes (86.6%) in the ‘cloud’ (less than 15 % of genomes). A total of 382 genes belonging to the AMR (n=82), HMR (n=32) and/or VF (n=268) classes were identified at different frequencies throughout the analysed genomes (Fig. 2b–h). A summary of these results divided by type is included in Fig. S1.

Fig. 2.

Size and count distributions of genomic features. First row: genome size (a) and Pan-genome distribution predicted by Roary (b). (c–h) Histograms showing the abundance of predicted genes and MGEs across the set of all genomes. Second row: frequency distribution of AMR genes (c), HMR genes (d) and VFs (e). Third row: frequency distribution of plasmids (f), GIs (g) and phages (h). Multiple occurrences of a feature in a given genome were counted only once. For clarity, only features detected in at least five genomes were plotted. Plot annotations indicate the number of features plotted and the number of total features detected.

Our analysis of the predicted mobilome identified 1131 sets of MGEs, all of which were part of the accessory genome except for Streptococcus phages predicted by DBSCAN-SWA in 1272 genomes. MOB-suite assigned plasmid-associated contigs to 263 different clusters. Of these, 88 were assigned to reference plasmid clusters and 175 were categorized as novel with 144 (83.2 %) of these associated with UK isolates. Given that many of these novel clusters may be misclassified chromosomal fragments, we did not include these in our subsequent analysis. The 7805 GIs were predicted to constitute 824 groups of GIs with only 15 GI clusters present in more than 10 % of the isolates, 477 of them being unique to single genomes.

Distribution of the resistome, virulence factors, and MGEs by type assignment, geographical origin and habitat

Profiling of these E. faecium genomes revealed a wide diversity of resistance determinants and MGEs. Although E. faecium is globally distributed, high levels of mobility may generate regional differences in the presence of important genes and MGEs. Lineage-based differences in abundance may reflect constraints on mobility between relatively distant isolates, while uneven habitat distributions may be indicative of selective advantage in some habitats relative to others. We assessed these differences using a factorial three-way ANOVA (Table 1). For all features, marginal effects at a threshold of α=0.05 were observed for at least one of the categories (geography, habitat and type). However, in each case at least one significant interaction effect was also observed, which suggests conditionally dependent patterns of association and the need to interpret the main effects with caution. Habitat showed the strongest marginal effects for all features except HMR, with P<10−7 in all other cases. Geography was associated with HMR, VFs and plasmid clusters, but post-hoc significance testing strongly suggested that the HMR relationship (P=4.16×10−5) is an artefact of interaction effects driven by type A agricultural isolates from the UK (Table S2B). AMR and phage showed significant associations with the type A/type B split, although the latter (P=4.69×10−2) was not supported by post-hoc testing. In the two-way ANOVA using Alberta genomes, results were consistent with the three-way ANOVA with the exception of HMR determinant frequencies, which were found to be significantly affected by habitat at P<0.05 (Table 2). Inspection of the HMR frequency post-hoc significance tests indicate that this effect is likely caused by habitat × type interactions, with NWS and CLIN isolates showing significant differences between type A and type B HMR determinant frequencies (Table S2B).

Table 1.

Three-way ANOVA results for 1200 genomes in habitats that were sampled in both AB and the UK. Type III sum-of-squares error was used to account for imbalanced classes. Columns indicate P-values testing differences of mean unique features per genome. Factor1 × Factor2 indicates interaction effects among categories

|

Variable |

AMR |

HMR |

VF |

Plasmid |

GI |

Phage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Type |

6.42×10−04 |

2.36×10−01 |

8.92×10−02 |

5.87×10−01 |

9.59×10−01 |

4.69×10−02 |

|

Habitat |

5.09×10−15 |

7.26×10−02 |

1.29×10−09 |

1.74×10−31 |

5.03×10−40 |

1.14×10−08 |

|

Geo. |

8.34×10−01 |

4.16×10−05 |

2.28×10−04 |

8.76×10−03 |

6.46×10−01 |

7.80×10−01 |

|

Type × habitat |

6.31×10−04 |

2.54×10−02 |

1.46×10−04 |

1.05×10−04 |

5.26×10−07 |

7.41×10−04 |

|

Type × geography |

3.04×10−01 |

6.90×10−01 |

7.12×10−01 |

3.62×10−01 |

4.42×10−01 |

6.11×10−01 |

|

Habitat × geography |

2.20×10−08 |

1.62×10−04 |

6.58×10−01 |

2.50×10−04 |

1.76×10−13 |

1.16×10−03 |

|

Type × geography × habitat |

1.76×10−04 |

4.62×10−01 |

4.88×10−03 |

1.74×10−01 |

2.61×10−03 |

7.04×10−02 |

Table 2.

Two-way ANOVA for 303 AB genome assemblies, performed separately to account for the WW-AGR and NWS habitats exclusive to AB. Type III sum-of-squares error was used to account for imbalanced classes. Columns indicate significance values testing differences of mean unique features per genome. ‘Habitat × type’ indicates the interaction effect of habitat and type categories

|

Variable |

AMR |

HMR |

VF |

Plasmid |

GI |

Phage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Habitat |

2.32×10−40 |

2.48×10−03 |

3.39×10−14 |

2.19×10−62 |

1.61×10−55 |

3.95×10−11 |

|

Type |

2.34×10−07 |

1.21×10−01 |

7.09×10−02 |

4.40×10−01 |

9.50×10−01 |

4.48×10−02 |

|

Habitat × type |

4.71×10−08 |

2.57×10−04 |

2.32×10−05 |

1.76×10−08 |

1.16×10−09 |

1.93×10−03 |

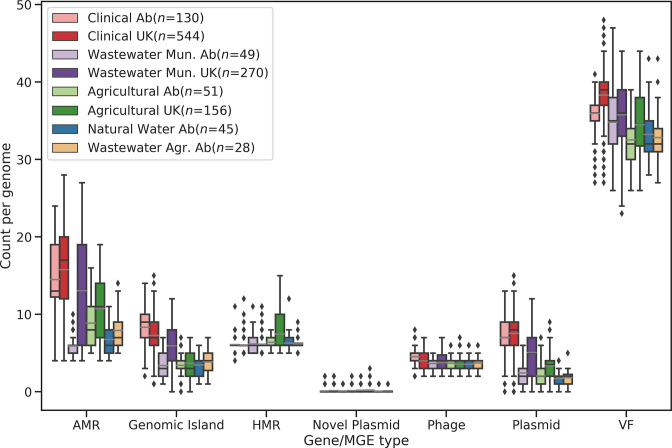

A total of 19599 AMR genes was predicted in the 1273 isolates: removal of duplicates yielded 16 898 genes with a mean occurrence of 13.27 per genome. We observed a large discrepancy between types A (14.3±5.3 predicted AMR genes per genome) and B (5.9±1.6 AMR genes per genome) (Table S4; Figs 3 and S2). Plasmids and GIs showed discrepancies as well, with 6.2±3.0 mean occurrences of distinct plasmid clusters in type A and 2.0±1.3 in type B. GIs were found 7802 times, with 6.5±2.8 of mean occurrences in type A and 3.7±1.6 in type B. Conversely, HMRs, VFs and phages showed similar distributions between types even when genomes were partitioned by geography and habitat.

Fig. 3.

Abundance of features by habitat type and geographic location. ‘AB’ indicates genomes sampled from Alberta, Canada. ‘UK’ indicates genomes sampled from the UK. Counts indicate the number of unique features of a given category found per genome. Bars indicate quartiles. Points/diamonds are considered to be outliers if they fall outside 1.5×the interquartile range. Grey bars indicate mean values.

For AMR genes, plasmids and GIs, the difference in distribution between types A and B was still observed after considering the geographical origin of the samples (Table S4). However, we detected a large variation in the distribution of the AMR genes, plasmids and GIs between UK and AB samples isolated from municipal wastewater. Specifically, the UK type A genomes had 14.3±6.4 AMR genes, 5.5±3.0 plasmids and 6.3±2.3 GIs compared to the AB type A genomes with 6.44±1.9 AMR genes, 2.7±1.9 plasmids and 3.2±1.5 GIs (Table S4). Differences in the distribution of AMR genes, plasmids and GIs between types A and B were also detected across habitats. Specifically, type A CLIN samples from the UK and AB had the highest mean of AMR genes per genome of all the isolates (15.9±4.5 and 15.0±4.0, respectively) with corresponding variation in the relative distributions of plasmids and GIs. Type-wise distributions of specific features are summarized in Table S5. The strong influence of habitat on the distribution of many elements associated with pathogenicity and resistance suggests that while non-clinical settings may act as reservoirs of resistance, the overall abundance of resistance-carrying MGEs is lower relative to settings where antimicrobial use is highest. Conversely, the strength of association with type may reflect barriers to exchange between type A and type B lineages, but may also arise as an artefact of uneven geographical sampling with respect to the two lineages.

Phylogenetic associations of target genes and MGEs

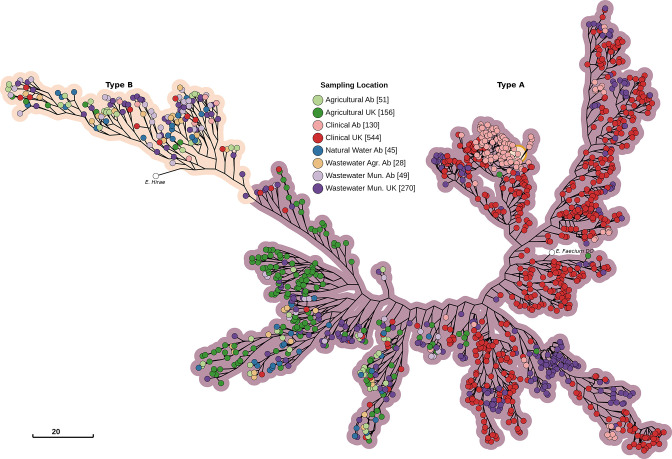

Phylogenetic associations between genetic elements can offer important clues about the forces shaping the structure of a species into populations. For instance, a strong association of a set of genes to a specific clade/type often present in a specific niche, would support the hypothesis that the set of genes is involved in the specialization process. To this purpose, we overlaid the presence/absence pattern of the feature over a reference phylogenetic tree inferred from the 1273 genomes (Fig. 4). Over half of type A was comprised of almost entirely CLIN and WW-MUN isolates (mainly derived from the UK), but two additional subclades possessed isolates from all habitats. Type B encompassed isolates collected from both countries and all five habitats, with environmental and geographical categories constituting monophyletic groups.

Fig. 4.

Maximum-likelihood core-genome phylogenetic tree of 1273 E. faecium genomes with E. hirae ATCC9790 as the outgroup and E. faecium DO ASM17439v2 as the reference genome. The tree was constructed with 1854991 nucleotide sites, 79440 of which were parsimony informative, using the general time reversible substitution model with invariant sites and four Gamma rate categories. Branch lengths are log-transformed and scaled down to 13 % length for improved readability. Nodes are coloured by sampling location, with hue indicating habitat and saturation indicating geography.

Most features were irregularly distributed across the phylogenetic tree (Fig. S1a–f). Relatively few AMR genes were present in type B compared to type A, particularly type A CLIN. Only eatAv, a variant of eatA that confers resistance to multiple antibiotics, was present in the majority of non-clinical subtrees and absent from most CLIN and WW-MUN isolates. Both the vanA and vanB operons were restricted to the CLIN/WW-MUN subtree. Two sets of HMR genes showed strong negative associations, largely mapping onto the type A/type B division; the corresponding genes had the same names (chtR, ruvB, copB and chtS). These clusters may have been divided because of sequence dissimilarity rather than functional differences. Although some VFs were preferentially associated with type A or type B isolates, very few were exclusively confined to one or the other. Some plasmids and GIs were over-represented in the CLIN/WW-MUN type A, and less frequently associated with the non-clinical isolates and type B.

Significant (P-values <0.01) associations were observed for AMR features with geography (18.0%), type (12.5%) and habitat (11.5 %; P<10 − 10) (Fig. S4a). Overall, the strongest positive and negative associations were seen for the CLIN and AGRI habitats, respectively. The vanA genes and genes conferring resistance to aminoglycosides, macrolides, tetracycline, trimethoprim, streptothricin all met this threshold (Table S6). As an example, vanA was prevalent in CLIN genomes but almost never present in AGRI genomes. VFs exhibited associations with habitat, geography and type (Figs S4a, S2c). HMR genes associated more strongly with geographic origin than habitat or type (Fig. S4b). The likelihood ratios of specific feature associations with sampling location are reported in Table S6. The strong positive association of many resistance genes and MGEs with clinical and related habitats supports an adaptive role; however, the distinction is not absolute and nearly all elements show patchy distributions in even the most-similar clinical strains.

Physical location of resistance genes and virulence factors in the genome

The prediction of MGEs from genome assemblies in tandem with target genes allowed us to identify linkages between resistance genes and MGEs, and to assess the diversity of these linkages; i.e. the association of a target gene to more than one mobile element of a given type, or even to elements of different types. These mappings can identify co-localization of target genes and their emerging combinations, along with highlighting the extent of their dissemination potential via LGT as gauged through their association with specific MGEs. Therefore, we determined the localization of the 72786 predicted AMR, HMR and VF genes in the 1273 genomes. A total of 18518 (25.4 %) predicted genes mapped to one or more MGEs, with 20.6 % mapping to plasmids, 5.1 % to GIs and 2.2 % to prophages. There was a total of 102 MGEs with colocalized AMR and VF genes and a total of seven MGEs with both AMR and HMR genes (Table S7).

The dominant plasmid clusters AB369, AC731 and AB173 were identified in 400, 678 and 187 genomes, respectively. Common AMR genes in these plasmids included the vanA operon, sat-4, ermB and the aminoglycoside resistance genes aac(6’)-Ie-aph(2’)-Ia, aad(6) and aph(3’)-IIIa. Six VFs associated with the PilA pilus structure were also frequently found on these plasmids. However, the relative numbers of these genes differed among predicted plasmid clusters, with some containing solely AMR or VF genes. AB756, the fourth most-abundant plasmid cluster, also had substantial numbers of the three aminoglycoside resistance genes mentioned above, ermB, and sat-4, along with lsaE and the tetracycline resistance genes tetL, tetM and tet(W/N/W). AH273, the seventh most-abundant plasmid cluster, contained the HMR genes encoding the UDP-glucose 4-epimerase galE and the copper-translocating ATPase copA.

The most common GIs mainly housed tetracycline- and vancomycin-resistance genes. GI 14 (identified in 186 genomes) was associated with dfrG, tet(W/N/W) and tetM; GI 8 (identified in 310 genomes) with dfrF; and GI 34 (identified in 51 genomes) with the vanB suite of genes. GI 69 was found less frequently than the predominant GIs, being present in 18 genomes and containing ant(9)-Ia, efrA and ermA. Other predicted GIs had aminoglycoside-resistance genes, ermB (a macrolide resistance gene) and sat-4. Predicted VFs in GIs included bsh (VFC36), a bile salt hydrolase, ssaB (VFC39), a Manganese/Zinc ABC transporter substrate-binding lipoprotein precursor, fss3 (VFC42) a fibrinogen binding protein, ecbA (VFC84 and VFC86) a collagen binding protein, and multiple genes involved in capsule formation [epsE (VFC48), gmd (VFC51), cps2K (VFC52)].

Most prophage-associated genes mapped to either annotated ‘ Streptococcus phage’ (1366/1578) or ‘ Enterococcus phage’ (100/1578). Genes that mapped to the predicted Streptococcus phages were similar to those observed in the plasmids and GIs, including those associated with aminoglycoside, erythromycin (ermB), streptothricin (sat-4), and tetracycline resistance. While some common VFs were unique (eg. lap (VFC14), an alcohol dehydrogenase involved in adhesion to the host cells), others were similar to those found to be localized to GIs including bsh (VFC22 and VFC36), fss3 (VFC42), and ecbA (VFC84). Predicted Enterococcus phages had several instances of dfrA42 and bsh (VFC22).

Many of the genes noted above showed biassed associations with the corresponding MGEs. For example, over 93 % of all vanA and tetracycline-resistance genes mapped to predicted plasmids, as were over 80 % of the macrolide and streptothricin resistance genes ermB and sat-4, respectively. However, the gene-centric view also identified rare genes with strong biases including catA8, lnuB, ermT and chloramphenicol acetyltransferases. Over 75 % of vanB and dfrF genes were associated with GIs; other AMR genes with strong biases included optrA (65%) and lnuG (61.9%). The genes most strongly associated with prophages were the collagen-binding MSCRAMM gene (86.5 % of genes), tet(W/N/W) and tetM (61.7 and 40.4%, respectively) and dfrG (33.5%). However, all of these genes were also strongly associated with plasmids, GIs or both. No prophage-specific genes were identified. In general, many resistance genes and virulence factors of greatest concern were found in a variety of combinations and in association with multiple MGEs suggesting a high degree of plasticity that contributes to the wide transmission of multidrug resistance.

Phylogenetic distribution of MGEs

Plasmids and other MGEs can often transmit genes between species and more-distantly related lineages. Many genes and MGEs show patchy distributions within E. faecium and appear to associate more strongly with habitat than phylogeny, which supports a central role for LGT in their dissemination. We used two complementary approaches to assess the phylogenetic range of the elements considered here: one focused on the range of plasmids themselves, the other based on the observed distribution genes that are very similar between E. faecium and other taxonomic groups. We first examined the predicted host-range distributions of all features via direct homology search and host-range prediction feature of MOB-suite to determine the potential for transfer of these features in E. faecium and beyond. MOB-suite predicted a total of 7232 putative plasmids, which grouped into 88 unique MOB-clusters. A total of 4470 plasmid-associated contigs were predicted to be non-mobilizable, while 1782 were predicted to be mobilizable and 980 were predicted to be conjugative. The majority of plasmid-associated contigs (n=5652) were predicted to be specific to Enterococcus . Relatively few plasmid clusters had very narrow or very wide distributions outside of Enterococcus : a total of 358 clusters were associated with some other single genus, while 347 clusters were predicted to occur in phyla other than Firmicutes.

Although plasmid host range was often narrow, individual plasmid-associated genes were often strikingly similar (>99 % identity over at least 90 % of the subject sequence) to genes from other taxonomic groups, even at the phylum level. Of the contigs annotated as cluster AC731 across 678 genomes (36 mobilizable), 206 had at least one aminoglycoside-resistance gene with a high-stringency match outside of Enterococcus , frequently to Staphylococcus , Streptococcus , Campylobacter and members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, while 112 matched at least one gene in the vanA group, often across multiple phyla. Not all plasmids showed evidence of recent LGT. All non-hypothetical genes in plasmid cluster AH273, including a range of metal-associated transporters, had no stringent matches outside of Enterococcus . All the annotated members of this plasmid cluster were predicted by MOB-suite to be non-mobilizable.

Most GIs were dominated by integrases and other signatures of MGEs, and poorly annotated genes with products that include general ABC transporters. The most common GI was found in 484 genomes; over 90 % of these GIs had a suite of genes found in multiple phyla and included toxin-antitoxin and pilin genes, peptidases and annotated ABC transporter permeases. GI 26, found in 88 genomes, had a very high incidence of multiphylum tetM genes. The vanB genes found in GI 34 were nearly identical to those in other Firmicutes such as Staphylococcus , and occasionally in members of Enterobacteriaceae such as Klebsiella . Similarly, prophage genes with stringent matches to groups outside Enterococcus were predominantly associated with mobility and included endonucleases, integrases and transposases. However, over 500 genomes had genes annotated as ermB, with stringent matches to other phyla. A similar number of genomes had at least one aminoglycoside-resistance gene, the most common being ant(6)-Ia. Other common genes involved in transcription included transcription factors and 500 instances of the σ 70 subunit of RNA polymerase. While genes overall appeared to show a broader phylogenetic distribution than predicted plasmid host range would suggest, the localization of many genes to multiple MGEs as demonstrated in the previous section raises the possibility that a gene may enter on a broad host-range MGE then spread to others via recombination.

Distribution and associations of vancomycin-resistance genes

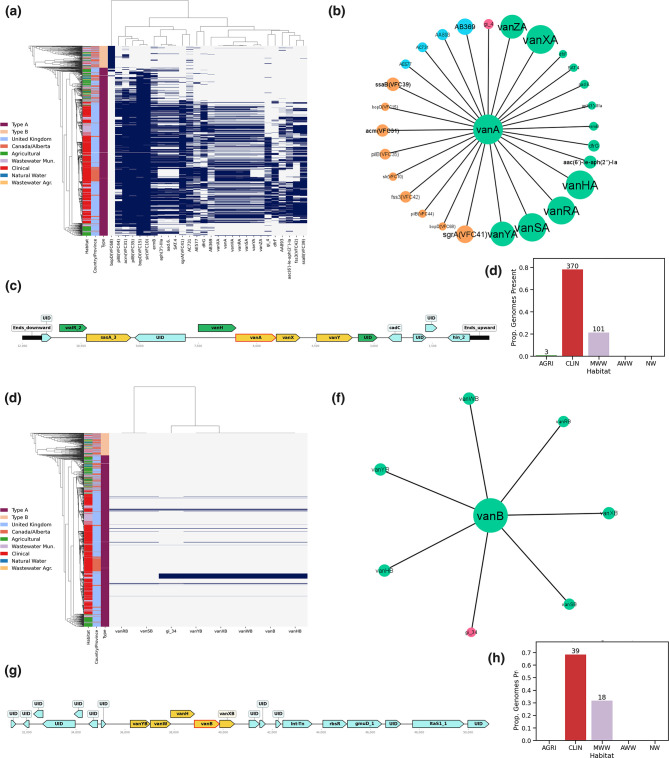

In E. faecium , vancomycin resistance can be conferred by several distinct sets of genes, and the phenotype is generally considered a hallmark of pathogenic enterococci. To understand the distribution and context of vancomycin resistance in the set of genomes, we determined their prevalence by type, habitat, geography and localization to mobile genetic elements. Both the vanA and vanB gene clusters showed a strong association with CLIN and WW-MUN but variable distribution and association with MGEs (Fig. 5). The vanA gene clusters were found to be disproportionately associated with plasmids in both the AB and UK datasets (Table S7). Overall, 458/474 vanA genes were found to colocalize to and associate with several plasmids of which AB369 and AC731 were the most abundant. The vanA genes were primarily identified in CLIN (100/474 AB and 270/474 UK) and WW-MUN samples from the UK (103/474), with only one isolate from UK AGRI sources.

Fig. 5.

Statistical associations and physical localization of vanA (a–d) and vanB (e–h) genes. (a, e) Phylogenetic distribution of van genes and other features with an associated likelihood ratio ≥100. (b, f) Statistical association network of vanA/vanB genes with other features. Gene and MGE colours are consistent with those in Fig. 2. (c, g) Example of gene order on an annotated plasmid (c) and GI (g). Green genes correspond to ‘Perfect’ matches with reference genes in the CARD database, yellow genes are ‘Strict’ hits. (d–h) Distribution of genes by habitat. Bar colours correspond to their habitats as per the legend in (a, e).

Conversely, all of the vanB gene clusters were found in UK genomes and, in 51/57 genomes, these genes colocalized to GIs (Fig. 5). For the remaining 6/57 genomes, the vanB was in the unaligned portion of the genome that was not included in the GI analysis. All of the vanB genes were predicted to fall on a single GI cluster (except for one representative that has a large insertion in the middle of the GI) and contained a Tn916 transposase. The positive association of vanB to GI cluster 34 was also supported (P<10 − 16). The majority (39/57) of vanB genes were in CLIN isolates with WW-MUN isolates composing the remaining 18/57 instances.

Other notable AMR gene classes

Macrolide, tetracycline and aminoglycoside are significant components of multidrug resistance in E. faecium , and we examined their association with different habitats and MGEs, and the differences in distributions of distinct genes and mechanisms. In addition to msrC (Fig. 6), a species-specific gene of E. faecium that confers low-level intrinsic resistance to macrolide and streptogramin B compounds [56], multiple macrolide-resistance genes were identified. The most abundant were ermB, (835/1271; 66%), ermT (14.7%) and ermA (6.7%) (Fig. S5). Some of these genes showed a bias for the CLIN (ermT) or AGRI and WW-AGR (ermA) environments, while ermB was prevalent in all environments except NWS and WW-MUN from AB. The majority of these genes were localized on plasmids, with ermA identified on AB369 (44/47; 94%) ermB mostly associated with AC731 (146/662; 22%) and AB369 (130/662; 20%). In AGRI genomes, ermB was commonly associated with AC730 (37/76; 49%) and AB756 (15/76; 20%). Plasmid clusters AC731 and AB369 were also associated with vanA and ermB. The ermA gene was exclusively associated with type A and the AGRI isolates, while ermB was positively associated with type A, as well as with UK, AGRI, NWS, CLIN and WW-MUN isolates. The ermT gene demonstrated a positive association with type A, UK and CLIN isolates and a negative association with AGRI and NWS isolates.

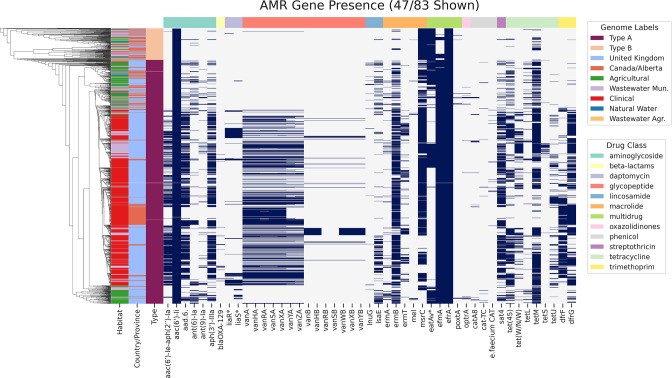

Fig. 6.

Heatmap showing the presence of AMR determinant genes detected in 1273 E. faecium genomes analysed in this study. The y-axis indicates genomes (colour coded by habitat, geography and type) sorted by topology of the core-genome maximum-likelihood tree. AMR determinants (x-axis) are sorted by drug class. * denotes variant versions of intrinsic genes conferring AMR.

Tetracycline-resistance genes were common, often plasmid-associated, in the analysed genomes (Fig. S6). tetM (783/1273; 61.5 %) was most prevalent, followed by tet(45) (455/1273; 35.7 %) in CLIN genomes from the UK. Other tetracycline genes including tet(W/N/W) (236/1273; 18.5 %) and tetU (168/1273; 13.2 %) were found at higher rates in WW-MUN and CLIN genomes from the UK; tetL (90/1273; 7.1 %) was found mostly in agriculture and WW-AGR with higher levels in AGRI genomes in the UK; tetS (37/1273; 2.9 %) was found primarily in WW-MUN and NWS. tet(40) and tetO were both found in UK WW-MUN.

The aac6-Ii gene, responsible for intrinsic aminoglycoside resistance in this species [57], was found in the majority of genomes (1271/1273; 99.8 %) (Fig. 6). Interestingly, a three-gene locus aad(6)-sat4-aph(3’)-IIIa (595/1273; 46.7 %) conferring resistance to aminoglycosides and streptothricin, was present in AGRI, CLIN and WW-MUN isolates at higher prevalence in the UK than AB. A bi-functional protein-coding gene aac(6’)-Ie-aph(2’)-Ia (468/1273; 36.8 %) was also found at higher abundance in the UK CLIN and WW-MUN isolates compared to AB. Both ant(6)-Ia (166/1273; 13.0 %) and ant(9)-Ia (82/1273; 6.4 %) exhibited a higher prevalence in AGRI isolates than isolates from other habitats. A small number of CLIN and WW-MUN isolates from the UK harboured ant(9)-Ia, while corresponding Alberta isolates lacked this gene. Other rarely detected aminoglycoside-resistance genes included apmA (11/156 UK AGRI genomes), aph2-IVa (2/270 UK WW-MUN genomes), aac(6)-Iak (2/544 UK CLIN and 2/270 UK WW-MUN genomes), aac(6)-II (1/544 UK CLIN genomes), aph2-Ie (1/270 UK WW-MUN genomes), and ant(4)-Ib (2/51 AB AGRI genomes).

Heavy-metal and biocide-resistance genes

Heavy-metal resistance plays a fundamental role in the specialization to habitats. Copper-resistance genes were commonly detected in the E. faecium genomes and were a preponderant component of the predicted HMR genes (12/32 gene clusters). The most common were two copB clusters (BacMet clusters 3 and 9) and a copA cluster (BacMet cluster 5). While cluster 3 copB were spread across habitats and countries, the cluster 9 copB were most predominant in AB WW-MUN, AGRI, NWS and WW-AGR isolates and were underrepresented in CLIN and all UK isolates (Fig. S7). The copB genes were all chromsomal except for 2/1155 cluster 3 and 3/137 cluster 9 copB representatives associated with GIs and plasmids, respectively. The copA cluster 5 was also prevalent in all environments, although more so in CLIN isolates and UK WW-MUN. Most copA (549/917) were also predicted to be associated with the chromosome, while 366/917 cases were predicted to be localized to plasmid AH273. Another cluster of copper-resistance genes primarily associated with the agricultural environment in the UK included the genes mco (BacMet cluster 14), tcrB (BacMet cluster 15), tcrA (BacMet cluster 16) and copY/tcrY (BacMet cluster 17). All these genes were strongly associated with one another as well as the plasmid AC726. There were five instances identified where copper genes and mercury-resistance genes were colocalized on a single MGE, with plasmid cluster AD908 involved in three instances. All of these cases were identified in AGRI genomes from the UK.

Virulence factors

Because E. faecium is an opportunistic pathogen, it is difficult to determine which virulence determinants are important from a clinical perspective. For this reason, we analysed the distributions and associations of some of the most common virulence factors. Both the ssaB and fss3 genes have been shown to play a role in adhesion. These genes were primarily identified in CLIN genomes from both countries and WW-MUN genomes from the UK. ssaB was either localized on the chromosome (364/627; 42 %) or on GIs (263/627; 58 %) (Fig. S8). In particular, 59 % (215/263) of the genes were associated with a single GI. An additional 36 % (95/263) were identified on GI 23, which also carried fss3 in 85 % (81/95) of cases. GI 23 was primarily identified in the UK dataset (93/95). fss3 was found in 63 % of UK CLIN genomes, but only 14 % of AB CLIN genomes. Among the remaining fss3 genes not present on GI 23, 37 % (181/483) were present on the chromosome, 27 % (132/483) on other GIs, 18 % (88/483) on regions predicted to be both a GI and a prophage, and one was predicted to be on a non-GI-associated prophage. Both ssaB and fss3 were strongly correlated to each other, clinical-related AMR genes, and MGEs.

A total of 25 VFDB gene clusters were predicted to be pilin genes common to all habitats. The CLIN genomes had the highest prevalence of these genes, and the proportion of UK AGRI isolates with each of these genes was higher than the AB AGRI isolates (Fig. S9). Plasmids were the most common localization site of pilA (929/958; 97.0 %), pilE (1023/1060; 96.5 %) and pilF (881/909; 96.9 %), with the most common colocalized plasmids being AD907 and AC731. The chromosomal pilB gene had a similar prevalence across all datasets and was found on the chromosome.

Discussion

E. faecium , commonly a minor harmless component of the enteric microbiota, has become a leading causative agent of healthcare-associated infections since the early 1980s [58, 59]. The combination of approaches we applied here can augment phenotype-based ‘One Health’ genomic-surveillance workflows for E. faecium and other bacterial pathogens. Using the whole-genome approach the potential for gene transfer and the distributions of genes within and between habitats can be defined.

Genomic epidemiology suggests strong habitat associations but few barriers to transmission

The AB and UK genomes are distributed on the core-genome-based phylogenetic tree independent of type or habitat. This indicates that geographic separation has very little impact on the population structure of E. faecium . There was no significant difference in the abundance of MGEs between types or geographic origin (Tables 1 and 2), which appears to contradict the findings of previous studies that detected significantly higher numbers of MGEs in clade A than in clade B [23, 27, 60]. The phylogenetic approach of BayesTraits suggested that the observed differences were driven by increased MGE abundance in CLIN and WW-MUN isolates (Fig. 3). The lack of observed association with type suggests that MGEs can move between phylogenetically distant E. faecium isolates and that MGEs within populations are similar across continental barriers.

The global patterns of association seen among AMR and VF genes mirrored those of MGEs, with habitat generating the smallest P-values in the ANOVA tests (Tables 1 and 2). Geographic origin showed strong associations only in interactions with habitat for AMR genes and MGEs, likely as a result of intensive use of antimicrobials, which can result in the emergence of multidrug-resistant E. faecium . E. faecium may acquire a multi-drug resistance plasmid in the clinical setting but lose it upon introduction to another habitat [61]. This process can occur rapidly and repeatedly, with habitat serving only as an ecological filter rather than a barrier to transmission. Analysis of the composition of features by groupings of type, habitat and geography supports the division of features based on type and habitat.

Several AMR genes were significantly associated with geography (Table S6). Differences in the sampled hosts between the two geographies might partially explain this observation as the UK AGRI genomes originated from a broad variety of hosts (e.g. chicken, turkey, pig, beef and dairy cattle) while the AB AGRI genome were isolated from beef cattle production sources. Another possible source of this difference might be ascribed to different antimicrobial use in agriculture between Alberta and the UK. As an example, multiple aminoglycoside-resistance conferring genes were among the 80th percentile of co-evolutionary likelihood ratios with geography (Fig. S10). Aminoglycosides are used in the UK, but not Alberta [1, 2]. However, our information about antibiotic use is incomplete, especially for chickens and turkeys [62, 63].

A highly diversified and dynamic accessory genome allows the rapid acquisition of resistance and other traits

Although some of the 88 plasmid clusters and 824 GI sets identified are likely very similar, they are nonetheless different enough in sequence and gene content to be differentiated. The number of unique prophages is likely an underestimate due to the grouping of some phages by name (e.g. ‘ Streptococcus phage’) rather than by homology. Key resistance genes were observed in association with many predicted plasmid clusters. For example, 14 observed clusters had at least one vanA gene. Similarly, multiple clusters showed associations with tetracycline, aminoglycoside and macrolide-resistance genes. The dispersion of genes across multiple clusters likely diminishes the strength of observed associations, such that we may not identify all MGEs that associate with specific genes. Additionally, aggregation of plasmids and GIs into broader clusters (such as plasmid incompatibility groups) and consequently fewer classes might improve our ability to detect important associations. The increased prevalence of many classes of resistance genes and MGEs in the clinical environment suggests that this may be the key focal point of plasmid evolution, with novel combinations forming through recombination events. The lack of geographic barriers, and the apparent ability of E. faecium to move between habitats, suggests that new MGEs will not be limited in their ability to disperse. The clear ability of E. faecium to acquire and disseminate new genes from distantly related species creates additional risks for the emergence of new combinations of AMR determinants.

An emerging clade of pathogenic E. faecium

The groEL-based clade-mapping on our reference tree supports a monophyletic clade A, as described and proposed by Palmer et al. [64], but a paraphyletic ‘clade B’, which has led to our designation of these two groups as ‘types’ rather than clades. Earlier work proposed a division of clade A into a pathogenic subclade A1, and a commensal group specific to non-human animals capable of causing sporadic infections, subclade A2 [23]. Although we use the ‘type’ terminology here to avoid the incorrect use of the term ‘clade’, we recognize that the rooting of a tree can be sensitive to the choice of outgroup, and we cannot conclusively reject the idea that there are indeed two clades. Importantly, none of the analyses we perform here are sensitive to the root; in particular, BayesTraits implements a reversible coevolutionary model and is not sensitive to the position of the root.

However, consistent with recent observations by others, we observed a large group comprised of CLIN and WW-MUN isolates that branched within the larger grouping that included genomes isolated from all habitats (type A); this tree topology has been referred to as a clonal expansion [65, 66]. Importantly, our phylogenetic tree is based on the core genome of our isolates (n=1273) and, therefore, its topology should be less affected by LGT events than a gene-focused or whole-genome tree and thus should better reflect the structure and evolutionary trajectory of E. faecium populations.

Transfer of AMR-carrying MGEs into a recipient group can provide ephemeral advantages that confer a fitness edge in occupying a specific habitat. This is shown by our finding that vanA, dfr and ermT genes are mainly present in the CLIN and WW-MUN habitats where they are essential for survival considering the likely usage of corresponding antimicrobials associated with those setting. The fact that these genes are strongly associated with these habitats by distribution and by the phylogenetic BayesTraits analysis, supports that these genes are important in the process of specialization to these niches. However, our core-genome tree hints at a deeper genetic divergence at play. It suggests that there may be a sub-population adapting to the clinical niche beyond the simple and more plastic advantage provided by MGEs. This is consistent with the observation from Leclerque et al. that members of this clinical expansion are out-competed by other E. faecium clones in natural environments [67] and by Montealegre et al. that strains from type B have higher fitness than type A in the absence of antibiotics [68]. These findings, together with our results, support the hypothesis proposed by Prieto et al. that this clinical clonal expansion is so specialized to its environment that its strains are unfit to populate other environments and niches. This population could get more isolated and drift away from the rest of the species [66]. If the clinical-associated group we detected in our dataset has some level of diversification, it may satisfy the Cohan and Perry [69] definition of an ecotype, with lineage cohesiveness conferred by genetic similarities and distinguished by unique adaptations (e.g. AMR genes) and ecological capabilities. Cohan and Perry hypothesized that periodic selective sweeps reduce genetic variation between the genomes of organisms specialized to certain ecological niches, increasing the differences between these ecotypes and the rest of the named species [69]. However, other authors emphasize the role of recombination in bacterial divergence, which allows for gene-specific sweeps [70].

Other pathogenic species can give some insight into the driving forces shaping the E. faecium population structure we observed. For example, in the last 30 years a new multidrug-resistant genotype, H58, of Salmonella enterica sp . enterica sv. Typhi (S. Typhi) emerged as a clonal expansion and has rapidly spread globally [71]. This clade, like E. faecium , quickly differentiated into major antimicrobial-resistant lineages [72], but, unlike E. faecium , the differentiation has been driven by strong geographical selection [71]. Interestingly and contrary to E. faecium , H58 has a similar fitness to other Salmonella genotypes in absence of antimicrobials and local genetic drift rather than niche specialization is responsible for its diversification. This difference suggests that the E. faecium clinical ecotype is locked into clinical associated environments as competitive exclusion from other strains prevent its expansion [67, 68]. However, relying solely on this niche restriction to guide our surveillance efforts would be a mistake, as recombination events are common in E. faecium [73] and several circulating non-clinical type A strains are likely recombinants between type A and type B [74]. Therefore, it is possible for neglected non-pathogenic strains to acquire the traits necessary to expand to the clinical environment while retaining their cosmopolitan lifestyle.

Towards monitoring of evolving threats

As in many other pathogens, the genomic plasticity of E. faecium effectively creates a reservoir of genes and MGEs that can reshuffle according to environmental pressures and opportunities, with geographic distance, phylogenetic distance and habitat boundaries as no obstacle. Although the analytical pipeline we apply here was effective in detecting environmental and genetic connections, improvements in sampling, sequencing and analysis will be needed to realize the full potential of genomic monitoring. While it makes sense to focus efforts on the sampling of clinical isolates, isolates from other environments need to be collected with appropriate metadata such as local antimicrobial usage and connectivity patterns with other sampling locations.

The limitations of short-read sequencing are well documented, and MGEs are generally more difficult to recover due to the increased abundance of repeat regions [75–77]. Hybrid long-read/short-read assemblies can provide complete or near-complete information about MGE gene content and enrich reference databases to serve as references for short-read assemblies. Future work should also include refinements of the statistical methods used and techniques to identify key genes. For example, contextual information such as gene order can enhance the differentiation of true AMR genes from highly similar false positives. In our analysis, we found that the filtering parameters applied to the analytical outputs are of paramount importance. In fact, after curation, some of the more rare genes we identified proved to be artefacts generated by thresholds that were not stringent enough to root out low levels of sequence contamination or short but unreliable matches to databases.

Conclusion

The genome analyses we present confirm the previous observations detecting a large array of MGEs in E. faecium and reveal a strong evolutionary correlation between these elements and resistance genes. In particular, our phylogenetic-driven analyses support the hypothesis that MGEs are fundamental contributors to the genome plasticity of this species, which is necessary for the specialization to different environmental niches. A crucial example of this phenomenon is the role we detected of AMRs and MGEs in the still incipient emergence of a clinical ecotype from a clonal expansion of type A. While this ecotype is extremely well adapted and proficient at colonizing nosocomial environments, it is poorly fit to survive in the natural environment typical of this species, thus limiting it to a specific niche. However, this barrier to further spread of this ecotype might be ephemeral, potentially overcome by lateral gene transfer from more environmentally robust strains and by introgression of this group’s pathogenic traits into other clades. For this reason, close genome-based monitoring of the genetic make-up of the circulating strains in different environments across the One Health continuum is of paramount importance in the management and control of E. faecium and other evolving pathogens.

Supplementary Data

Funding information

This work was supported by grants from Genome Canada, Research Nova Scotia, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to R.G.B, F.S.L.B. and A.G.M.). K.G. was supported by scholarships from NSERC CREATE, CIHR and Simon Fraser University. R.G.B. is supported by NSERC and the Dalhousie Faculty of Computer Science. F.M. was supported by a Donald Hill Family Fellowship. A.G.M. was supported by a Cisco Research Chair in Bioinformatics and a David Braley Chair in Computational Biology. T.A.M and R.Z. were supported by grants from the Genomics Research and Development Initiative of the Government of Canada and the One Health Major Innovation Fund of the Province of Alberta. Additional funding was provided by the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. The funders played no role in study design, execution or the decision to publish.

Acknowledgements

We thank Henry and Charlie Sanderson for their constant support.

Author contributions

H.S., K.G., F.S.L.B., R.C.F., R.Z. and R.G.B. conceptualized the study. H.S., K.G., A.M., F.M., A.K., C.L., C.N.R., J.H.E.N., J.R., K.B., M.O., B.P.A., A.R.R., A.G.M., F.S.L.B., R.C.F. and R.G.B. contributed one or more of experimental design and execution, development and validation of software, and data analysis. H.S., F.M., T.A.M., S.J.P., K.E.R., T.G. and R.G.B. contributed datasets and/or performed curation of datasets. H.S., K.G., A.M., A.K., R.C.F., R.Z. and R.G.B. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AB, Alberta, Canada; AGRI, agricultural; AMR, antimicrobial resistance; CLIN, clinical; GI, genomic island; HMR, heavy metal resistance; MGE, mobile genetic element; NWS, natural water systems; UK, United Kingdom; VF, virulence factor; WW-AGRI, wastewater agricultural (catchbasin); WW-MUN, wastewater municipal.

All supporting data, code and protocols have been provided within the article or through supplementary data files. Ten supplementary figures and eight supplementary tables are available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Gouliouris T, Raven KE, Ludden C, Blane B, Corander J, et al. Genomic surveillance of Enterococcus faecium reveals limited Sharing of strains and resistance genes between livestock and humans in the United Kingdom. mBio. 2018;9:e01780-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01780-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaheer R, Cook SR, Barbieri R, Goji N, Cameron A, et al. Surveillance of Enterococcus spp. reveals distinct species and antimicrobial resistance diversity across a One-Health continuum. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3937. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanderson H, Ortega-Polo R, Zaheer R, Goji N, Amoako KK, et al. Comparative genomics of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus spp. isolated from wastewater treatment plants. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:20. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1683-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray BE. The life and times of the Enterococcus . Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:46–65. doi: 10.1128/CMR.3.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Müller T, Ulrich A, Ott EM, Müller M. Identification of plant-associated enterococci. J Appl Microbiol. 2001;91:268–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinseth IS, Ovchinnikov KV, Tønnesen HH, Carlsen H, Diep DB. The increasing issue of vancomycin-resistant enterococci and the bacteriocin solution. Probiotics & Antimicro Prot. 2020;12:1203–1217. doi: 10.1007/s12602-019-09618-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uttley AH, Collins CH, Naidoo J, George RC. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Lancet. 1988;1:57–58. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer KL, Kos VN, Gilmore MS. Horizontal gene transfer and the genomics of enterococcal antibiotic resistance. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courvalin P. Transfer of antibiotic resistance genes between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1447–1451. doi: 10.1128/AAC.38.7.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raza T, Ullah SR, Mehmood K, Andleeb S. Vancomycin resistant enterococci: a brief review. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68:768–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Low DE, Keller N, Barth A, Jones RN. Clinical prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility, and geographic resistance patterns of enterococci: results from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program, 1997-1999. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32 Suppl 2:S133–45. doi: 10.1086/320185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oppenheim BA. The changing pattern of infection in neutropenic patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41 Suppl D:7–11. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mundy LM, Sahm DF, Gilmore M. Relationships between enterococcal virulence and antimicrobial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:513–522. doi: 10.1128/CMR.13.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treitman AN, Yarnold PR, Warren J, Noskin GA. Emerging incidence of Enterococcus faecium among hospital isolates (1993 to 2002) J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:462–463. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.462-463.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torell E, Cars O, Olsson-Liljequist B, Hoffman B-M, Lindbäck J, et al. Near absence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci but high carriage rates of quinolone-resistant ampicillin-resistant enterococci among hospitalized patients and nonhospitalized individuals in Sweden. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3509–3513. doi: 10.1128/JCM.37.11.3509-3513.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortún J, Coque TM, Martín-Dávila P, Moreno L, Cantón R, et al. Risk factors associated with ampicillin resistance in patients with bacteraemia caused by Enterococcus faecium . J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:1003–1009. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simonsen GS, Småbrekke L, Monnet DL, Sørensen TL, Møller JK, et al. Prevalence of resistance to ampicillin, gentamicin and vancomycin in Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolates from clinical specimens and use of antimicrobials in five Nordic hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:323–331. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thouverez M, Talon D. Microbiological and epidemiological studies of Enterococcus faecium resistant to amoxycillin in a university hospital in eastern France. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:441–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klare I, Konstabel C, Mueller-Bertling S, Werner G, Strommenger B, et al. Spread of ampicillin/vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium of the epidemic-virulent clonal complex-17 carrying the genes esp and hyl in German hospitals. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:815–825. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-0056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dadashi M, Sharifian P, Bostanshirin N, Hajikhani B, Bostanghadiri N, et al. The global prevalence of daptomycin, tigecycline, and linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium strains from human clinical samples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:720647. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.720647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lebreton F, Manson AL, Saavedra JT, Straub TJ, Earl AM, et al. Tracing the enterococci from paleozoic origins to the hospital. Cell. 2017;169:849–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lebreton F, van Schaik W, McGuire AM, Godfrey P, Griggs A, et al. Emergence of epidemic multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium from animal and commensal strains. mBio. 2013;4:e00534-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00534-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galloway-Peña J, Roh JH, Latorre M, Qin X, Murray BE. Genomic and SNP analyses demonstrate a distant separation of the hospital and community-associated clades of Enterococcus faecium . PLoS One. 2012;7:e30187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegstad K, Mikalsen T, Coque TM, Werner G, Sundsfjord A. Mobile genetic elements and their contribution to the emergence of antimicrobial resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium . Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:541–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadowy E. Linezolid resistance genes and genetic elements enhancing their dissemination in enterococci and streptococci. Plasmid. 2018;99:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arredondo-Alonso S, Top J, McNally A, Puranen S, Pesonen M, et al. Plasmids shaped the recent emergence of the major nosocomial pathogen Enterococcus faecium . mBio. 2020;11:e03284-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03284-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li W, Wang A. Genomic islands mediate environmental adaptation and the spread of antibiotic resistance in multiresistant enterococci - evidence from genomic sequences. BMC Microbiol. 2021;21:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02114-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kondo K, Kawano M, Sugai M. Distribution of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes within the prophage-associated regions in nosocomial pathogens. mSphere. 2021;6:e0045221. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00452-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews S, Krueger F, Segonds-Pichon A, Biggins L, Krueger C, et al. FastQC. Babraham Institute. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, Wong VK, Reuter S, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Page AJ, Taylor B, Delaney AJ, Soares J, Seemann T, et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb Genom. 2016;2:e000056. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic eEra. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoang DT, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:518–522. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Z, Alikhan N-F, Sergeant MJ, Luhmann N, Vaz C, et al. GrapeTree: visualization of core genomic relationships among 100,000 bacterial pathogens. Genome Res. 2018;28:1395–1404. doi: 10.1101/gr.232397.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hung W-W, Chen Y-H, Tseng S-P, Jao Y-T, Teng L-J, et al. Using groEL as the target for identification of Enterococcus faecium clades and 7 clinically relevant Enterococcus species. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alcock BP, Raphenya AR, Lau TTY, Tsang KK, Bouchard M, et al. CARD 2020: antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D517–D525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hyatt D, Chen G-L, LoCascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu B, Zheng D, Jin Q, Chen L, Yang J. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47:D687–D692. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pal C, Bengtsson-Palme J, Rensing C, Kristiansson E, Larsson DGJ. BacMet: antibacterial biocide and metal resistance genes database. Nucl Acids Res. 2019;42:D737–D743. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buchfink B, Reuter K, Drost H-G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2021;18:366–368. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01101-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahé F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ. 2019;4:e2584. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robertson J, Nash JHE. MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Microb Genom. 2018;4 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ondov BD, Treangen TJ, Melsted P, Mallonee AB, Bergman NH, et al. Mash: fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol. 2016;17:1186. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0997-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertelli C, Gray KL, Woods N, Lim AC, Tilley KE, et al. Enabling genomic island prediction and comparison in multiple genomes to investigate bacterial evolution and outbreaks. Microb Genom. 2022;8 doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bertelli C, Brinkman FSL. Improved genomic island predictions with IslandPath-DIMOB. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2161–2167. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waack S, Keller O, Asper R, Brodag T, Damm C, et al. Score-based prediction of genomic islands in prokaryotic genomes using hidden Markov models. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gan R, Zhou F, Si Y, Yang H, Chen C, et al. DBSCAN-SWA: an integrated tool for rapid prophage detection and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.12.199018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Maxwell S. Designing Experiments and Analyzing Data: A Model Comparison Perspective. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barker D, Meade A, Pagel M. Constrained models of evolution lead to improved prediction of functional linkage from correlated gain and loss of genes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:14–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pagel M. Detecting correlated evolution on phylogenies: a general method for the comparative analysis of discrete characters. Proc R Soc Lond, B, Biol Sci. 1994;255:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu C, Wright B, Allen-Vercoe E, Gu H, Beiko R. Phylogenetic clustering of genes reveals shared evolutionary trajectories and putative gene functions. Genome Biol Evol. 2018;10:2255–2265. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hollenbeck BL, Rice LB. Intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms in Enterococcus . Virulence. 2012;3:421–433. doi: 10.4161/viru.21282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]