Abstract

Drawing on network learning theory, it investigates the effect of small and medium-sized enterprises' (SMEs) experience of using foreign and domestic social network services (SNS) and foreign and domestic platforms (such as B2B digital platforms) on their international orientation. We further examine the moderating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the relationship between digital experience and international orientation. Empirical results from a sample of 373 observations from 250 Chinese SMEs show that their use of foreign SNS and B2B digital platforms has a stronger positive impact on their international orientation than their use of domestic SNS and B2B digital platforms. Even with the COVID-19 pandemic, SMEs' use of foreign SNS still has a stronger positive impact on their international orientation than their use of domestic SNS. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic mitigates the positive impact of their use of both foreign and domestic platforms on their international orientation. This study presents some interesting theoretical and practical implications for SMEs' digitalization and internationalization.

Keywords: International orientation, Network learning theory, Social network services, Digital platforms, COVID-19 pandemic, Small and medium-sized enterprises

1. Introduction

Our understanding of both social media and platform networks (i.e., digitalization) (Bai et al., 2021; Chuang, 2020; Slotte-Kock and Coviello, 2009; Tortora et al., 2021; Adomako et al., 2021) and the internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Alayo et al., 2019; Bai et al., 2021; Gerschewski et al., 2018; Stoiana et al., 2018) has improved considerably in the past two decades, yet empirical research at the interface of these two phenomena is acutely absent. This scarcity of research is surprising, considering the rapid pace with which firms are adopting social media and platform networks for various reasons (e.g., increase brand awareness, enhance performance, internationalization strategy design, etc.) (Stallkamp and Schotter, 2021) and the socio-economic contributions of SMEs to employment, wealth creation, investment, innovation and international trade (Knight, 2000; Park and Ghuari, 2015). Most multinational enterprises (MNEs) encompass large organizations (Stoiana et al., 2018), but a new change starts to enter the scene and it can be characterized by the emergence of small and medium-sized multinationals with the prevalence of globalization (Su et al., 2020). Upholding this assertion, Odlin and Benson-Rea (2017) state that SMEs have made an appearance, competing with other firms in the global arena. Similarly, Knight (2000) also highlights that globalization and the emergence of internationally active SMEs are key worldwide phenomena.

Beyond this, the world economy is still deep in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is undeniable that the upended landscape will influence firms' behavior in terms of their intent to internationalize. However, we are still blind to the pandemic's impact on firm outcomes, highlighting the importance of our paper. COVID-19 has been an inordinate catalyst in fast-tracking the existing global trend of embracing modern technology, leading to transformation in business behavior, work patterns, and corporate strategies. Functioning as a detonator, COVID-19 has triggered firms to adopt and expand their use of digitalization while they pursue internationalization, alongside presenting foreseen and unforeseen opportunities, challenges, and costs (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021b). Thus, in an attempt to develop our knowledge in this area, the aim of this research is to explore the impacts of digitalization on SMEs' internationalization and the moderating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the association between digital experience and SMEs' international orientation (IO). To achieve the research objective, we attempt to answer the question, “how does digital-related experience affect SMEs' IO and has the COVID-19 pandemic had an effect on this relationship?”. We hereby employ network learning theory, expecting that our results will particularly contribute to the specific literature stream at the intersection of internationalization and digitalization research. This series of affirmations is elaborately described in detail below.

International business continues to experience rapid development and expansion due to the internationalization of firms and the emergence of internet-based technologies, such as social networking services (SNS) and digital platforms (Bai et al., 2021). These two factors combine to enhance the flow of information and technology, toppling barriers and opening up markets for business expansion and immersion in diverse locations (Park and Ghuari, 2015). In particular, the development of SNS and digital platforms has in itself facilitated faster communication channels and network learning through the dissemination of information at such a rapid pace that instantaneous reactions and technology flows have become commonplace in the global economy (Lee and Trimi, 2021). Meanwhile, global business continues to expand unabated as foreign direct investment (FDI) stocks and flows grow, particularly with the increased awareness of small and medium-sized MNEs' activities across the world (Luo, 2006). Although some skeptics (for instance, Garg, 2021) insist that the arguments for and evidence of globalization are somewhat exaggerated, the phenomenon of increasing FDI can be confirmed by objective facts and data (Paul and Benito, 2018). For instance, the outward stock value of FDI transactions grew from US$1.8 trillion/year in 1990 to US$7.4 trillion in 2000 and US$19.9 trillion in 2010. By 2020, this had more than doubled as worldwide FDI activities reached US$41.4 trillion (UNCTAD, 2009, UNCTAD, 2021). In addition, the internationalization of firms, e.g., through FDI, continues to show increasing competitive intensity, with competition in the development of internet-based technologies deepening in particular as the utilization of a market strategy alone does not guarantee a firm's competitiveness (Chuang, 2020).

Due to this trend, digitalization-based information has become more readily available, and consequently, small and medium-sized MNEs' interest in digitalization is increasing steadily, with them trying to integrate it at numerous levels of their business processes (Semrau and Sigmund, 2012). Thus, one of the main areas of interest developed in the global economy at the impetus of those firms is perhaps the SNS and digital platform business. They are increasingly tasked with building organizational competitiveness not merely to enhance their performance but indeed to ensure their survival. This is especially true for SMEs as they commonly suffer from a lack of organizational assets (Stoiana et al., 2018), which indicates the value of studies exploring them. There is no longer a single sole pursuit for corporations, but rather through their network (e.g., social media and digital platform networks) there is an ever-increasing level of attention being paid to catch up with other firms in the learning race (Park and Ghauri, 2011). As this change has happened over time, the importance of the role of SNS and platform businesses has evolved, as witnessed in the international business arena. Thus, it is reasonable to state that the continuing growth of SNS and digital platforms does not solely influence large conglomerate companies, but also affects the strategic vision that characterizes many small and medium-sized multinationals (Bai et al., 2021). Moreover, due to their pivotal role in achieving the internationalization of business, such networks, both at home (i.e., domestic SNS and digital platforms) and abroad (i.e., foreign SNS and digital platforms), have proliferated as new and adaptive means and concepts have emerged. The purpose behind the use of these networks has also changed, particularly for SMEs, from simply gathering customers within an internet environment to pursuing the firm's internationalization at large and having a positive impact globally (Li and Zhang, 2007).

However, interestingly, it is hard to find previous studies dealing with the precise effects of social media (i.e., SNS) and platform networks and their contributions to firm internationalization (Bai et al., 2021). While the business associated with SNS and internet platforms (e.g., B2B platforms) is increasingly being mentioned as a promising industry (Lee and Trimi, 2021), a large body of research has merely focused on the IT sector (e.g., Shore et al., 2018) or specific programs developed in response to internet development (e.g., Chen and Macredie, 2010). In addition, it is even harder to discover extant empirical studies examining the relationships between such networks and firm internationalization. The even more serious problem resides in the fact that, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has simultaneously examined the influences of both network learning and digitalization on SME internationalization in the international business domain.

This study seeks to fill these gaps in the current body of research by examining SMEs' utilization of SNS and B2B digital platforms and identifying the impacts of both networks on the firms' international orientation (IO) (the definition of IO is given in Section 3.2). The filling of those voids in the relevant literature is a valuable empirical contribution of this paper. We also try to further contribute empirically by examining the moderating role of the COVID-19 pandemic in these relationships (i.e., the effects of the pandemic on the association between digital-related experience and SMEs' IO). Furthermore, by incorporating the COVID-19 pandemic into a global value chain (GVC) network structure setting, our study provides new theoretical insights on the pandemic's impact on SMEs' IO, which has been scarcely examined in the previous literature. More specifically, based on a sample of 373 responses from 250 Chinese SMEs, this empirical study provides a greater understanding of the effects of networks and the pandemic on SMEs and the extent to which they interact with the firms' IO. In tackling the research objectives, this research also theoretically endeavors to contribute to the network learning theory, digitalization, and SME internationalization literature.

2. Research context and relevant definitions

In this study, IO is defined as “the degree to which international firms actively explore new business opportunities in foreign markets and commit appropriate resources for international operations” (Bagheri et al., 2019, p. 129). The digital platform is “the digital information technology that supports information exchange activities with partners” (Cenamor et al., 2019, p. 200). A B2B digital platform, which is a focus of this study, is an online marketplace that connects a seller firm and a buyer firm. Transactions on the online market occur by negotiating, and both parties (i.e., the seller firm and the buyer firm) communicate using tools provided by the platform, such as online instant chat (Jean et al., 2020). For example, Alibaba.com is a digital transaction platform that connects suppliers and purchasing firms around the world (Hänninen, 2020). In our research context, we define digital platforms as online transaction platforms featuring an online marketplace that facilitates actual transactions between suppliers and buyers by connecting them (Jean et al., 2020).

In this study, we define SNS “as a web-based service that allows individuals and organizations to create own profiles, establish connections with other users and view connections established by themselves and by others” (Pogrebnyakov, 2017, p. 46). Social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, facilitate information sharing that transpires through the network and the social ties of users, helping to foster strong relationships (Hänninen, 2020; Scuotto et al., 2017; Chuang, 2020). Also, social media acts as “new digital tools' agility” in that it “represents a key business imperative to communicate with stakeholders, to collaborate with customers or develop new products, by generating and sharing social information associated with the capabilities of information processing” (Tortora et al., 2021, p. 194).

The use of SNS and participation in B2B digital platforms comprise a learning process, specifically the network-learning process of firms that allows them to accumulate digital knowledge-related experiences, such as finding knowledge via SNS, acquiring the skills to find knowledge, and transferring knowledge (Nguyen et al., 2015). To explore the relationship between SMEs' digital-related experience and their IO in the context of China, this study classifies SMEs' digital-related experience as SMEs' foreign and domestic SNS experience and foreign and domestic platform experience (such as B2B digital platforms).

SMEs' use of foreign SNS refers to foreign-based SNS, such as Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook, whereas SMEs' use of domestic SNS refers to locally based (Chinese) SNS, such as Renren Net, Weibo, and Kaixin Net (Williams et al., 2020). In line with our definition of SMEs' use of foreign SNS and domestic SNS, we define SMEs' use of foreign platforms as the use of foreign-based digital platforms, e.g., foreign B2B digital platforms such as eWorldTrade, ECPlaza, Fiber2Fasion, and TradeKey. In contrast, SMEs' use of domestic platforms refers to the use of locally based (Chinese) digital platforms, such as Alibaba, Made-in-china.com, China.cn, DIYTrade, and ECVV. In general, SNS are mainly used for information searching and marketing, whereas B2B digital platforms provide the settings for the actual transactions (Scuotto et al., 2017; Eggers et al., 2017; Jean et al., 2020; Fraccastoro et al., 2021a). Therefore, since SNS and B2B digital platforms are likely to furnish different kinds of experiences and knowledge, they may represent digital-related experiences with different functionalities (Kim, 2020).

Over the last two decades, SMEs have become important economic actors in the Chinese market (Jean et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020). However, they have recently faced the dramatic transformation introduced by digital technologies and their applications in both domestic and foreign SNS and digital platforms (Jean et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020). Today's economic landscape on this digital technology frontier reflects the shifting forces and forms of globalization (McKinsey, 2014; Strange, 2019). Of course, this phenomenon is not limited to China (Wang et al., 2016; Woetzel et al., 2017), and almost all countries are experiencing similar situations (Banalieva and Dhanaraj, 2019; Chen et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the Chinese “digital landscape” as the new phenomenon has attracted scholarly and practical attentions (Chen et al., 2015) for the following reasons.

National borders often imply different languages, cultures, and regulatory environments, whereas networks are considered borderless in the digital world. Nevertheless, we witness that the network effects of some platforms are geographically bounded (e.g., in China) (Stallkamp and Schotter, 2021). We chose China since the country's cultural and political borders are salient even in digital environments. For instance, the government has a propensity to control and censor internet firms and their digital content (Liu et al., 2018; Chong et al., 2018; Katsikeas et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020). Thus, China, which has a huge digital market that international internet firms cannot neglect, provides an excellent research context for investigating the impact of SMEs' foreign and domestic SNS experience and foreign and domestic platform experience.

China's digital economy market size is $52.4 trillion, the second-largest in the world after the U.S., with Germany, Japan, and the U.K. making up the remaining top five countries (Yu, 2021). The global economy has suffered a global recession due to the COVID-19 pandemic, yet the global e-commerce market is an exception, becoming even more lively as untact consumption has increased worldwide. Especially in China, e-commerce already accounted for more than 50% of global retail sales on the Internet, and the COVID-19 pandemic has increased this share by affecting the relationships between Chinese SMEs' use of foreign versus domestic SNS, use of foreign versus domestic digital platforms, and IO. Thus, our examination of the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic is truly significant in the context of contemporary Chinese SMEs.

3. Theoretical background and hypotheses development

3.1. Network learning theory

The experiences to which a firm is exposed through its relationships in its networks (e.g., social media and digital platform networks) considerably influence its characteristics and behaviors. For instance, firms' rich business networks allow them to access new strategic resources (e.g., knowledge assets) spread throughout the GVC and may thus help them to accumulate unique entrepreneurial capabilities in their internal reservoir, thereby logically strengthening their organizational competitiveness and motivating them to expand their business trajectory (Xiao et al., 2020). The evidence that networks other than business interlocks influence firms' behavioral tendencies suggests that the network effect discussed above is a general phenomenon and not limited to specific network contexts (Su et al., 2020). In general, networks can not only serve as key avenues for consultation and direct attention to new practices, but can also ease the acquisition of knowledge that is unavailable internally and act as normative pressures for firms to engage in different operational activities.

These dialogs also imply that network linkages can function as conduits that allow firms, especially those suffering from a lack of experience and a weak institutional environment, to seize chances to obtain valuable resources, such as necessary information, strategic expertise, and new market access opportunities (Li and Zhang, 2007; Semrau and Sigmund, 2012). In this vein, compared to large emerging market firms (Aulakh et al., 2000; Peng et al., 2004; Uhlenbruck et al., 2003) or conventional SMEs from developed economies (Brouthers et al., 2009; Lu and Beamish, 2001), this explanation holds, for instance, for Chinese SMEs in that they are canonical examples that typically experience institutional and resource disadvantages. This archetypal weakness of Chinese SMEs may force them to actively seek external knowledge assets through network learning and attain opportunities for market expansion through networks (Xiao et al., 2020).

Networks are often considered an important source of learning (e.g., Beckman and Haunschild, 2002; Gibb et al., 2017), and interest in such organizational learning at the level of the network is called “network learning” (Easterby-Smith et al., 2000). Knight and Pye (2005, p. 371) define network learning as the “learning by a group of organizations as a group” and “[i]n this specifically network-centered view, changing network-level properties, such as shared practices and processes, would indicate network learning”. Their definition of network learning implies that learning through networks is a useful means for firms to acquire efficient skills from other firms or synthesize existing information with new external knowledge, because “organizations are collections of overlapping knowledge systems each of which may be embedded within a wider occupational community” (Araujo, 1998, p. 331). As such, inter-firm networks are knowledge-sharing vehicles whereby member firms utilize the network to transmit knowledge, amass it in their “knowledge warehouse” or “knowledge reservoir”, and apply it to commercial ends. In doing so, they avoid many of the costs implied in knowledge transactions across markets. This series of illustrations clearly informs us that firms can gain various information and knowledge resources by networking with other firms, which provides learning opportunities within a wider community (Park and Ghauri, 2011).

3.2. International orientation, SMEs and digital experience

To reiterate, IO refers to the degree to which a firm actively seeks new business opportunities in overseas markets and tries to invest appropriate resources in its international operations (Bagheri et al., 2019; Knight and Kim, 2009). Firms with a high IO tend to have the vision and proactive organizational culture to develop specific resources to achieve their goals in foreign markets (Knight and Kim, 2009). In particular, the IO of SMEs is regarded as the core foundation of internationalization (Williams et al., 2020), and a firm's success in overseas markets depends on its IO (Bagheri et al., 2019). Firms with a higher IO are better able to recognize unique foreign market opportunities and better identify threats abroad than firms with a low IO (Bagheri et al., 2019). SMEs with high-level international business experience are able to increase specific decision-making activities and practices to recognize opportunities in overseas markets and are thus linked to successful internationalization achievements (Knight and Cavusgil, 2004). In relation to this, numerous researchers have emphasized that the successful internationalization of SMEs is essential for their growth and survival (Bagheri et al., 2019; Taiminen and Karjaluoto, 2015; Knight and Kim, 2009). Previous studies have also reported a positive relationship between IO and SME performance in foreign markets (Knight and Kim, 2009; Bagheri et al., 2019).

Digital-related experience plays a more pivotal role for an emerging market SME (ESME) in increasing its competitiveness than it does for developed-market SMEs. Specifically, the former is a conventional example that experiences a lack of strategic resources and knowledge, and thus it is more motivated to learn through networks than the latter. That is, for SMEs that lack the resources and experience required for internationalization, the experience derived from the use of digital platforms provides access to a wide range of overseas market knowledge quickly and cheaply, allowing them to enter overseas markets with relative ease (Jin and Hurd, 2018; Mathews et al., 2016). However, even though digital experience has a significant impact on the IO of SMEs experiencing barriers to foreign market entry, such as a lack of foreign market knowledge and experience, related studies are rare.

Only limited studies have examined how digital experience influences traditional firms' international strategies (Jean et al., 2020; Mathews et al., 2016; Kim, 2020). Furthermore, the influences of both the social media and digital platform networks on the IO of SMEs have rarely been investigated. While Williams et al.'s (2020) study was among the first to recognize the impact of SNS use on the IO of Chinese internet SMEs, they did not examine the impact of the use of B2B digital platforms on the same. Furthermore, their sample comprised high-tech internet SMEs, which can differ from general SMEs in terms of digital capabilities (Cenamor et al., 2019; Kim, 2020). Integrating the knowledge acquired through the use of social media and digital platforms into a firm's overall strategy provides a critical asset that helps the firm to maintain its competitiveness (Nguyen et al., 2015). From this point of view, the previous literature that relates digital platforms to internationalization mainly discusses the advantages of digital platforms, such as cost efficiency and global reach (Jin and Hurd, 2018; Hänninen, 2020; Rialp-Criado and Rialp-Criado, 2018), but a more important aspect is that digital platforms provide a potential network learning opportunity for firms. Therefore, based on the network learning perspective, this study investigates SMEs' use of SNS and B2B digital platforms and identifies the impacts of both their social media and platform business networks on their IO.

3.2.1. SMEs' use of foreign versus domestic SNS

Extending the logic of network theory to the context of social media and digital platforms, we argue that SMEs' digital experiences, such as the experience of foreign SNS use, can enhance their IO through network learning. Based on network theory, SMEs' use of their SNS experience can be regarded as network learning in that they learn through a socially networked platform and accumulate the acquired knowledge assets.

With this logic, we predict that knowledge assets acquired through the socially networked use of foreign SNS will have a positive effect on the IO of SMEs due to internationalized network learning. Also, the use of domestic SNS may have a less positive impact on IO due to the more limited nature of domestic social networks. SNS offer highly interactive platforms on which participants become network members and interact through web-based applications (Rialp-Criado and Rialp-Criado, 2018; Aichner and Jacob, 2015). SNS also connect individuals and groups and allow networks to be built based on individual or company profiles (Eggers et al., 2017). Due to the interactive nature of SNS, firms share and exchange information with customers as well as create new content (Aichner and Jacob, 2015; Tsimonis and Dimitriadis, 2014). The characteristics of SNS enable a network to be formed through the voluntary connection of its participants, while the need for fewer information-sharing steps contributes to the creation of a network in which content is easily distributed to more people (Tsimonis and Dimitriadis, 2014). Hence, by creating pages or business accounts on social media platforms, such as Facebook, firms can be exposed to various countries and gain opportunities to interact with consumers from various cultures (Pogrebnyakov, 2017).

The use of SNS allows SMEs to discover and meet unknown customer needs and discover future trends (Eggers et al., 2017). SMEs can also use SNS to establish relationships with existing and new customers as well as discover solutions for product improvement or new product or service ideas through discussions between customers or external parties on an online business network (Tsimonis and Dimitriadis, 2014; Hultman et al., 2021). The experience gained by SMEs through online interaction reduces the psychic distance by providing an opportunity to understand the behaviors and preferences of foreign consumers and gain insight into the environmental differences of overseas markets (Jin and Hurd, 2018). Therefore, learning through social media networks can be a useful means for SMEs to acquire diverse information and efficient skills from customers and other firms as well as synthesize existing information with external new knowledge, which in turn may impact IO. IO represents the dominant mindset of a firm and is guided by what it has learned about overseas markets (Williams et al., 2020). As a result, the foreign SNS experience of SMEs becomes a source of learning that is highly likely to have a positive effect on SMEs becoming more internationally oriented.

Meanwhile, even though the networks of foreign and domestic SNS play a pivotal role in shaping the IO of SMEs, we argue that SMEs' use of foreign SNS has a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic SNS. The usage characteristics of SNS may be different for each country, and thus can reflect different cultural aspects (Li, 2014). According to Williams et al. (2020), as an example, the use of Chinese SNS involves different features compared to foreign SNS in that the former are more collectivist and locally oriented. In fact, according to previous research, foreign SNS, such as Facebook, have a greater effect on linking social capital more strongly than emerging market domestic SNS, such as Renren, which are more relevant to maintaining social capital in the home country (Li and Chen, 2014). In other words, domestic SNS help to maintain strong local social capital, while foreign SNS do not (Williams et al., 2020). Also, emerging market SMEs (ESMEs) may have a “linguistic distance” (Dow and Karunaratna, 2006) or “language friction” (Joshi and Lahiri, 2015) relating to foreign languages such as English, so they are likely to feel more comfortable using domestic SNS than foreign SNS, which encourages them to settle for the status quo. Because SMEs find it difficult to invest time and manpower in both forms of SNS due to resource constraints, if an SME is entrenched in its use of domestic SNS, there is a high possibility that its commitments related to the business network will continue to be domestically oriented.

In summary, when an SME uses domestic SNS, the network it hereby establishes is more likely to be locally oriented than when using foreign SNS. In this case, it is highly likely that the flow of internationally related knowledge will be reduced. Therefore, we predict that SMEs' use of foreign SNS will have a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic SNS.

Hypothesis 1

SMEs' use of foreign SNS has a stronger positive impact on their international orientation than their use of domestic SNS.

3.2.2. SMEs' use of foreign versus domestic B2B digital platforms

Firms enjoy location advantages by performing value chain activities in dispersed countries, and recent advances in digital technology have facilitated the coordination and control necessary for firms' GVC activities (Verbeke, 2020). Recently, many firms have formed virtual value chains by participating in digital transaction platforms (Hänninen, 2020). China is part of the huge global network governance and is in charge of a key supply hub (Qin et al., 2020). Therefore, we can assume that Chinese SMEs using foreign digital platforms are highly likely to serve as supply chains for key raw materials and intermediate goods for many MNEs. Likewise, if SMEs use foreign B2B digital platforms, there is a high possibility that they will frequently interact with overseas buyers. The network business ties created in this process can help SMEs establish strategic partnerships with other actors in the world market based on mutual benefits (Katsikeas et al., 2020).

From a business network perspective, the business network acts as the most important knowledge source and instrument for SMEs in the process of internationalization (Bai et al., 2021; Sandberg, 2014; Jin and Jung, 2016; Sendawula et al., 2020). The information flow between customers and suppliers in the business network, expedited through the digital platform, is highly likely to have a positive effect on the IO of SMEs. Business networks serve as a system of co-learning or knowledge circulation that shapes an SME's international strategy. They also provide opportunities to gain strategic information and knowledge about numerous organizations located outside of direct business relationships (Bai et al., 2021; Pagani and Pardo, 2017, Pagani and Pardo, 2017; Sandberg, 2014). Thus, an SME “may create new knowledge through exchange in its network of interconnected relationships (Johanson and Vahlne, 2009, p. 1414)”, and informal or formal business networks created through digital platforms may function as such a vehicle.

Exposure to international markets is related to the development of IO (Martineau and Pastoriza, 2016), and experience with foreign customers on a foreign digital platform reduces psychic distance, which can represent a barrier to internationalization decision-making, operation, and expansion (Jin and Hurd, 2018; Deng et al., 2022). These knowledge assets can act as a vehicle to bypass barriers related to communication and interaction with foreign business partners (Katsikeas et al., 2020; Fraccastoro et al., 2021b), helping SMEs to become more internationally oriented. Also, by experiencing international transactions via foreign digital platforms, SMEs can learn how to search for and select suitable buyers or agents in various overseas markets (Katsikeas et al., 2020). SMEs can also gain experiential knowledge of linguistic barriers, cultural differences, and differences in consumer behavior (Jean et al., 2020; Goldman et al., 2021). Furthermore, SMEs can better integrate their supply chains in international markets, and dealing with orders from foreign customers can also bring in skills that make SMEs more effective and efficient in terms of manufacturing and delivery in the GVC network (Katsikeas et al., 2020).

An SME's participation in a business network through a foreign-based B2B digital platform serves as a valuable knowledge resource for the identification and utilization of overseas market opportunities (Katsikeas et al., 2020). By allowing new foreign market knowledge to be accumulated, the liabilities of foreignness can be reduced, helping to remove psychological barriers to internationalization (Jin and Hurd, 2018; Mathews et al., 2016; Wang, 2020). In this way, B2B digital platforms provide SMEs with interaction and learning opportunities about international markets and transactions (Hänninen, 2020; Katsikeas et al., 2020; Jean et al., 2020; Caputo et al., 2022); hence, the use of foreign B2B digital platforms is likely to have a positive impact on IO.

Even though networks involving both foreign B2B digital platforms and domestic B2B digital platforms play a pivotal role in the IO of SMEs, we argue that SMEs' use of foreign B2B digital platforms has a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic B2B digital platforms. Domestic B2B digital platforms provide SMEs with opportunities to integrate supply chain networks to develop supply chain efficiencies, demand forecasting, and efficient logistics information management as well as reduce cycle times (Chong et al., 2018). In addition, digital platforms allow SMEs to sell their products to many customers at a lower cost than traditional retail channels (Jin and Hurd, 2018; Deng et al., 2022). In fact, most firms participating in B2B digital platforms are SMEs, and thus SMEs, particularly those with limited resources, need to improve their value chains through the use of B2B digital platforms (Chong et al., 2018).

However, domestic platforms have limited connectivity with overseas customers, and most customers using them are likely to be local business customers. Therefore, the global connections of a GVC network through foreign platforms will have a stronger positive impact on IO than transactions made in the local part of the GVC network through domestic platforms. Based on the aforementioned arguments, we predict that SMEs' use of foreign platforms will have a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic platforms.

Hypothesis 2

SMEs' use of foreign platforms has a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic platforms.

3.2.3. The moderating role of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic is an environmental disaster that is “a type of extreme-context disruptive crisis, ‘unique, unprecedented, or even uncategorizable’” (Sarkar and Clegg, 2021, p. 243). COVID-19 is affecting the global business ecosystem, including global and local businesses, and is regarded as a major exogenous disaster that has changed the competitive landscape of both SMEs and large organizations (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021, Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021).

Due to the sudden upheaval in the business environment disaster caused by COVID-19, many firms are experiencing financial difficulties (Brown et al., 2020). Moreover, the disaster is engendering environmental shocks from various aspects, including in the corporate work environment and international HRM (Caligiuri et al., 2020), global supply management (Sodhi and Tang, 2021), and the economies, institutions, and strategies of multinational firms (Hitt et al., 2021). Against the backdrop of COVID-19, many countries' lockdown policies have had a significant impact on the global business ecosystem and local businesses in terms of GVC, leading in particular to firms' rapid conversion to digitalization (Hitt et al., 2021; Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021, Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021, Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021; Wang and Sun, 2020).

We predict that knowledge acquisition via digitalization will still allow the network learning phenomenon to continue, even under the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we argue that despite the pandemic, SMEs' use of foreign SNS will still have a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic SNS. Due to the economic and social shock of the pandemic, firms are experiencing a sharp decline in production and performance, with the notable exclusion of some industries: Online retailers and various digital service providers are emerging as winners (Verbeke, 2020). Meanwhile, COVID-19 is having an excessive impact on SMEs due to their limited resources, e.g., human and financial resources, compared to large firms (Juergensen et al., 2020).

From a knowledge acquisition perspective, in a situation where cross-border movement is limited and constrained, such as in a pandemic, digital platforms become more important as a tool for SMEs' information search activities. In fact, SNS are regarded as a useful tool for information acquisition, and previous studies have demonstrated that the main motive for using SNS is information acquisition (Williams et al., 2020; Chang and Zhu, 2012).

Particularly in a situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic, SMEs can obtain internationally relevant knowledge, e.g., on foreign market conditions or foreign customers' preferences, through foreign SNS in an easy and cost-efficient manner (Rialp-Criado and Rialp-Criado, 2018; Parveen et al., 2016). In addition, the actual business linkages of overseas SNS networks allow firms to obtain desired knowledge or information about overseas markets or ways to access new markets (Hamill and Gregory, 1997; Williams et al., 2020). Rialp-Criado and Rialp-Criado (2018) argue that SNS help firms operate international business by improving international communication, efficiency in market transactions, the satisfaction and loyalty of overseas customers, and the development of international network relations. Indeed, according to a study by Arnone and Deprince (2016), SNS promote the creation and development of relationships between international partners, such as customer distributors and importers. Furthermore, an SNS-based network is a kind of knowledge-sharing vehicle, and the various types of knowledge acquired from the different participants can increase the absorptive capacity or learning opportunities within a wider community of SMEs (Bagheri et al., 2019; Park and Ghauri, 2011). In fact, Williams et al. (2020) highlight the learning benefit of social networks via SNS in that continuous participation in social media provides a continuous opportunity for contemplation and progressively develops knowledge resources. Taken together, networking through foreign SNS provides a pathway to actively interact with players in overseas markets, so that even in situations where physical movement is difficult, e.g., due to COVID-19, this may help SMEs to identify or seize opportunities abroad.

In light of the claim that SNS can be internationalized as an “internationalization space”, similar to what occurs in the physical world (Pogrebnyakov, 2017), we see that network learning still occurs despite the COVID-19 crisis. Also, notwithstanding the pandemic, the network learning phenomenon will continue, even without the transaction of goods, and thus it can be expected that the positive impact of SMEs' use of foreign SNS on IO will continue. Based on the aforementioned arguments, we predict that even with the COVID-19 pandemic, SMEs' use of foreign SNS will still have a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic SNS.

Hypothesis 3

Under the COVID-19 pandemic, SMEs' use of foreign SNS still has a stronger positive impact on their international orientation than their use of domestic SNS.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has prevented cross-border transactions due to, e.g., countries' blockade policies, port and border closures, air travel and transportation restrictions, delays in customs processing, and increased trade costs. Therefore, SMEs are more likely to interact with foreign firms through foreign digital platforms, such as by searching for information about opportunities in overseas markets or exchanging information. In fact, digital platforms have a positive effect on export performance by providing functions such as information sharing and communication (Kim, 2020). However, even if the information is searched for and exchanged over a digital platform, there is still a high possibility that the will for internationalization will be lower as it is difficult to make actual transactions.

With the collapse of GVCs due to the pandemic, the use of digital platforms is likely to have a negative impact on SMEs' IO. COVID-19 is a rare exogenous shock to firms that rely on international commercial linkages, including MNEs and SMEs as global supply partners (Verbeke, 2020). The COVID-19 crisis has had a faster and greater impact on SMEs than large businesses because SMEs have less inventory or supplier networks and find it more difficult to source from new suppliers (Borino et al., 2021). In addition, SMEs that previously had a competitive edge by relying heavily on low-cost outsourcing abroad were especially severely affected by the COVID-19-related collapse of logistics and international transportation, which complicated international outsourcing (Etemad, 2021).

As COVID-19 has spread rapidly to the global supply chain, countries such as Germany, Italy, the U.S., and China – often referred to as the major economies when discussing the GVC hub – saw their production activities seriously disrupted, and thus international trade has shrunk considerably (Baldwin and Tomiura, 2020). In particular, in the global economy, emerging markets such as China typically function as a central manufacturing pivot for global business operations, and they have had a serious impact on their regional value chains and GVCs as COVID-19 caused production to grind to a halt (Qin et al., 2020). In addition, B2B digital platforms do not have a proper role in this context due to the localization and regionalization of GVCs. Therefore, it is expected that the negative impact of the use of domestic platforms on SMEs' IO will be stronger than the impact of their use of foreign platforms.

Indeed, recent studies have shown that globalization is slowing, with regionalization filling the void (Wang and Sun, 2020). In addition, it is expected that in order to reduce exposure to risks, such as supply chain risks to exogenous shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic, the regionalization or localization of GVCs will be strengthened by firms diversifying their production locations or supply chains and firms returning to their home countries (Buatois and Cordon, 2020; Enderwick and Buckley, 2020). In fact, it has been reported that some international firms are already planning to re-shore their production bases to other countries or home countries (Qin et al., 2020).

In fact, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the pace of digitalization has continued to accelerate with the shift from offline to online. Online platforms are becoming increasingly dominant in the market as people are reluctant to make face-to-face contact out of fear of infection. Exemplifying this, several Chinese firms (e.g., Alibaba, Jingdong, and Pindudo) are in fierce competition for the huge e-commerce market. In addition, as firms must continue to create sustained value, emerging market firms are expanding their domestic supply chains for the smooth procurement of intermediate goods and parts and to reduce risks. Therefore, it can be expected that SMEs' use of domestic platforms increases their likelihood of being more locally oriented. SMEs have faced difficulties in responding to the pandemic because they lack human resources or the ability to manage such a crisis (Klein and Todesco, 2021). SMEs, in particular, lack both the experience and preparation to tackle the COVID-19 crisis and the ability to quickly change business models to accommodate new routines and processes (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021, Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021, Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2021). In this vein, the COVID-19 pandemic is mitigating the positive impact of SMEs' use of both foreign and domestic platforms on their IO. This negative impact is stronger for SMEs' use of domestic platforms than their use of foreign platforms due to the base effect of an already narrower GVC network of domestic platforms compared to foreign platforms.

Hypothesis 4

The COVID-19 pandemic has a stronger negative moderation effect on the relationship between SMEs' use of domestic platforms and their IO than the relationship between their use of foreign platforms and their IO.

4. Data and methods

4.1. Sample and data collection

In line with the previous literature (e.g., Lee et al., 2010), we used a mixed methods research design, including both preliminary qualitative interviews and a quantitative survey design, in a single study. We began the study with preliminary interviews as a qualitative approach. The purpose of our interviews comprised understanding the basic information of the SNS and digital service ecosystems for Chinese SMEs, checking and developing the questionnaire items, considering the relationships among potential variables, and designing potential hypotheses. Thus, we used an unstructured interview protocol instead of a semi-structured one. Then, we collected quantitative data from detailed and reliable surveys of Chinese SMEs. We employed the two sequential steps of this mixed methods design because this allowed us to address the complexity of the phenomena under study.

Accordingly, in order to understand the SNS and digital service platform ecosystems, we conducted interviews with 32 senior managers (CEOs, VPs, general managers, deputy general managers, managing directors, product directors, marketing directors or operations directors) from 26 SMEs in Beijing, Guangdong, and Shanghai (see Table 1 of the descriptions of these interviews). Based on our interviews, we obtained information on the SNS and digital platform use practices of these Chinese SMEs. Moreover, although we adopted the measurement items for our dependent variable from Knight and Kim's (2009) established scale, we reconfirmed the Knight and Kim's measurement items) by undertaking these interviews as well. Based on our preliminary interviews, for the independent variables, we developed the survey items via the established procedure of translation and back-translation from/to English to/from Chinese (Brislin, 1986). This was performed by two bilingual professors at a prestigious university in China, with the aim of confirming the conceptual equivalence of the independent variables and addressing the bias (Li and Atuahene-Gima, 2001) and the consistency with existing studies (e.g., Williams et al., 2020). Then, we pretested the survey instrument (i.e., the questionnaire designed to obtain quantitative responses) with 29 SMEs in Beijing, Guangdong, and Shanghai to acquire feedback on the 21 responses from the pilot study and to ascertain whether the quality of these responses was appropriate to proceed with our survey. Last, we refined the questions in our questionnaire based on our interviews and pretest.

Table 1.

Descriptions of interviews.

| Firm | Interviewee # | Location | Date | Duration | Industry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SME A | 1 | Beijing | 2 July 2019 | 2 h | Electrical equipment and components |

| 2 | SME B | 1 | Beijing | 3 July 2019 | 1 h 30 min | Computers, communication and other electronic equipment |

| 3 | SME C | 1 | Beijing | 3 July 2019 | 1 h 40 min | Electrical equipment and components |

| 4 | SME D | 2 | Beijing | 4 July 2019 | 2 h 30 min | Electrical equipment and components |

| 5 | SME E | 2 | Beijing | 5 July 2019 | 2 h 30 min | Computers, communication and other electronic equipment |

| 6 | SME F | 1 | Beijing | 11 July 2019 | 2 h 10 min | Photographic, medical and optical goods |

| 7 | SME G | 1 | Beijing | 12 July 2019 | 1 h 50 min | Electrical equipment and components |

| 8 | SME H | 1 | Beijing | 16 July 2019 | 1 h 30 min | Computers, communication and other electronic equipment |

| 9 | SME I | 1 | Beijing | 18 July 2019 | 2 h | Chemicals and allied products |

| 10 | SME J | 1 | Beijing | 23 July 2019 | 2 h 10 min | Machinery |

| 11 | SME K | 1 | Beijing | 26 July 2019 | 1 h 40 min | Food and beverage |

| 12 | SME L | 1 | Guangzhou | 30 July 2019 | 2 h 10 min | Photographic, medical and optical goods |

| 13 | SME M | 3 | Guangzhou | 1 August 2019 | 2 h 30 min | Apparel and leather |

| 14 | SME N | 1 | Guangzhou | 2 August 2019 | 2 h 10 min | Pulp and paper |

| 15 | SME O | 1 | Guangzhou | 5 August 2019 | 2 h | Plastics and rubber |

| 16 | SME P | 1 | Guangzhou | 7 August 2019 | 1 h 50 min | Advertising |

| 17 | SME Q | 1 | Guangzhou | 8 August 2019 | 1 h 40 min | Transportation equipment |

| 18 | SME R | 1 | Guangzhou | 13 August 2019 | 1 h 20 min | Machinery |

| 19 | SME S | 2 | Shenzhen | 14 August 2019 | 2 h | Transportation equipment |

| 20 | SME T | 1 | Shenzhen | 15August 2019 | 1 h 30 min | Transportation equipment |

| 21 | SME U | 1 | Shenzhen | 19 August 2019 | 1 h 30 min | Textile |

| 22 | SME V | 1 | Shenzhen | 19 August 2019 | 1 h 50 min | Textile |

| 23 | SME W | 1 | Shenzhen | 21 August 2019 | 1 h 40 min | Machinery |

| 24 | SME X | 2 | Shenzhen | 22 August 2019 | 2 h | Machinery |

| 25 | SME Y | 1 | Shanghai | 23 August 2019 | 1 h 40 min | Advertising |

| 26 | SME Z | 1 | Shanghai | 23 August 2019 | 1 h 50 min | Health |

From the list of 2361 SME population located in multiple regions in China, we randomly selected 1547 firms from 12 subnational regions1 using a simple random sampling technique (for reference, the list of SMEs was obtained from one of the leading companies providing marketing and survey services in China). To enable our results to be generalized, we selected from both developed and less-developed subnational regions in order to balance the heterogeneities of the regions in our sample. 34 trained staff from the headquarters and local branches of the Chinese survey partner, which had the contact details of the target firms, participated and helped to administer the survey. We performed two-by-two waves of surveys during the second half of 2019 (face-to-face or emails before the COVID-19 pandemic) and during the first half of 2020 (only emails during the COVID-19 pandemic) to reflect the differentials in Chinese SMEs' use of foreign versus domestic SNS, use of foreign versus domestic digital platforms, and IO between these two periods. As stated above, our respondents in these four survey waves were senior managers (e.g., founders, CEOs, VPs, general managers, deputy general managers, managing directors, product directors, marketing directors or operations directors). Our survey procedure provided reliable and quality-based survey information/data, which is consistent with the traditional survey procedure protocol in emerging markets such as China (Jean et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2005). Following Gaur et al.'s (2018) advice that collaboration with professional local organizations can be an efficient means to collect reliable, valid information in that Chinese respondents are often reluctant to share information with outsiders, our surveys were conducted with the help of a leading company providing marketing and survey services in China. Our questionnaire was approved by a research ethics committee of a prestigious South Korean university before our initial survey, and the committee confirmed that our questionnaire items did not touch upon any human rights violation issues.

For the first wave of our survey during the second half of 2019, we received 413 usable, complete responses from the 1547 SMEs we originally targeted. After omitting 51 responses from micro-sized firms (n < 10) due to a mismatch with our definition of an SME (a reported firm size of between 10 and 500 total employees) (Knight, 2000),2 362 were left as complete responses, resulting in a response rate of 23.4%. However, as we sought a time lag between the independent variables and the dependent variable of at least 30 days but no more than 37 days, we performed the second wave of our survey during the second half of 2019, gathering 250 complete responses, resulting in a response rate of 16.2%.

In early February 2020, with the COVID-19 lockdown in Wuhan, China, we decided to investigate the impact on the relationships between the variables. Thus, after the COVID-19 shutdowns started in China in early 2020, we commenced the third wave of our survey with the 250 SMEs from which we had received usable, complete responses during the second wave. We gathered 156 complete responses, resulting in a response rate of 10.08%. However, as before we sought a time lag between the independent variables and the dependent variable of at least 25 days but no more than 30 days; hence, we performed the fourth wave of our survey with the 156 firms from which we had received complete responses in the third wave of our survey during the first half of 2020. We gathered a sample of 123 responses from the fourth wave of our survey, resulting in a response rate of 7.95% of the originally targeted SMEs. In summary, to examine the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, we used 250 responses from the first and second waves of our surveys before the COVID-19 pandemic and 123 responses from the third and fourth waves of our surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, the final sample size is 373 responses from 250 Chinese SMEs as unbalanced panel data.

Our data reflect the various features of Chinese SMEs using foreign and domestic SNS and platforms. The mean age of the final sample of SMEs was 5.92 years, allowing us to consider these firms as relatively new startups. The mean number of full-time employees for the final sample was 108.28. The mean number of online B2B markets with which the SMEs of the final sample engaged was 2.28, displaying their high engagement with B2B digital platforms. The industries of the final sample were various, with 41.5% of SMEs active in the high-tech industries, such as electrical equipment/components, computers, communication and other electronic equipment, chemicals and allied products, transportation equipment, machinery, and photographic, medical and optical goods. The remaining SMEs were in the food and beverage, plastics and rubber, textile, apparel and leather, pulp and paper, health, packaging, and advertising industries. Table 2, Table 3 respectively report the distribution across the regions in China and the industries of our sample.

Table 2.

The distribution of regions in China for our samples.

| Region | Initial target sample (SME #) | Final sample (SME #) | Final sample (response #) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anhui | 73 | 9 | 15 |

| 2 | Beijing | 348 | 74 | 113 |

| 3 | Guangdong | 282 | 45 | 63 |

| 4 | Guizhou | 39 | 7 | 7 |

| 5 | Hebei | 91 | 13 | 21 |

| 6 | Hunan | 55 | 8 | 12 |

| 7 | Jiangsu | 217 | 27 | 44 |

| 8 | Jilin | 14 | 3 | 3 |

| 9 | Liaoning | 51 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | Shandong | 187 | 28 | 43 |

| 11 | Shanghai | 38 | 6 | 8 |

| 12 | Zhejiang | 152 | 22 | 35 |

| Total | 1547 | 250 | 373 |

Table 3.

The distribution of industries for our final sample.

| Industry | Response # | SME # | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Electrical equipment and components | 37 | 23 |

| 2 | Computers, communication and other electronic equipment | 17 | 11 |

| 3 | Chemicals and allied products | 25 | 14 |

| 4 | Transportation equipment | 18 | 15 |

| 5 | Machinery | 51 | 38 |

| 6 | Photographic, medical and optical goods | 5 | 3 |

| 7 | Food and beverage | 32 | 19 |

| 8 | Plastics and rubber | 46 | 28 |

| 9 | Textile | 59 | 40 |

| 10 | Apparel and leather | 49 | 35 |

| 11 | Pulp and paper | 15 | 12 |

| 12 | Health | 13 | 9 |

| 13 | Packaging | 2 | 1 |

| 14 | Advertising | 4 | 2 |

| Total | 373 | 250 |

Finally, we tested for non-response bias by grouping the early versus late responses for each wave of our survey and performed a t-test for the demographic variables (the number of total employees and total sales) (Armstrong and Overton, 1977). We found non-significant results (p > 0.05), indicating that there is no threat of a non-response bias in the present research.

4.2. Measurements

In order to capture our main variables, we utilized the following operationalization of the survey-based variables based on a seven-point Likert scale. First, our dependent variable is international orientation, based on Knight and Kim's (2009) established scale of IO. In order to check the unidimensionality of the operationalized measure for IO, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis with the eleven measurement items established by Knight and Kim (2009). Each item designed in the main survey was grouped except for five measurement items, and only one factor was deducted as it had an eigenvalue greater than one. These five excluded measurement items, namely (1) a cautious posture in international decision-making situations, (2) international exploration via incremental steps, (3) top management's international business experience, (4) management's communication of information, and (5) vision and drive of top management, showed relatively low factor loadings, which affected the reliability of the dependent variable; hence, these five items were deleted. After we conducted an exploratory factor analysis and reliability verification of the sample data, we statistically re-investigated based on discriminant validity and convergent validity and performed a confirmatory factor analysis (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). No item was deleted in this confirmatory factor analysis since the level of significance of the measured dependent variable's factor score was under 0.001. Hence, based on the subsequent model refinement and these exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, six out of the eleven measurement items were utilized in our analysis. Table 4 displays the results of this confirmatory factor analysis. In addition, to verify internal consistency, we also computed Cronbach's alpha coefficient and confirmed that it was 0.929, demonstrating a cutoff of over 0.6, which is the standard cut-off value of internal consistency (Nunnally and Berstein, 1994). Further, we tested the CR (composite reliability) and AVE (average variance extracted), and the results (CR = 0.944; AVE = 0.739) showed that the constructs exceeded the standard acceptance levels (CR > 0.7; AVE > 0.5), and thus every measured item was confirmed to have convergent validity (Hair et al., 2005).

Table 4.

Measurement and confirmatory factor analysis results.

| Constructs and measures (loading) |

|---|

| International orientation (1 = not at all; 7 = to an extreme extent) (CR = 0.944; AVE = 0.739) Please indicate the extent to which degree of your internationalization orientation: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SME's use of foreign SNS vs. domestic SNS (1 = not at all; 7 = to a great deal) |

| To what extent does your firm use (this) foreign SNS? |

| To what extent does your firm use (this) Chinese SNS? |

| SME's use of foreign platform vs. domestic platform (1 = not at all; 7 = to a great deal) |

| To what extent does your firm use (this) foreign platform? |

| To what extent does your firm use (this) Chinese platform? |

Second, our independent variables for Hypothesis 3 are foreign SNS use and domestic SNS use, each measured using single questions, namely “To what extent does your firm use (this) foreign SNS?” and “To what extent does your firm use (this) Chinese SNS?”, based on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = not at all; 7 = to a great extent) (see Table 4). Examples of foreign SNS included Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn, while Chinese SNS included Renren Net, Weibo, and Kaixin Net. These measurements are in line with Williams et al. (2020).

Third, our independent variables for Hypothesis 4 are foreign platform use and domestic platform use; these two variables were measured using single questions, namely “To what extent does your firm use (this) foreign platform?” and “To what extent does your firm use (this) Chinese platform?”, based on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = not at all; 7 = to a great extent). Foreign B2B digital platforms included eWorldTrade, ECPlaza, Fiber2Fasion, and TradeKey, while Chinese B2B digital platforms included Alibaba, Made-in-china.com, China.cn, DIYTrade, and ECVV. These measurements are also in line with Williams et al. (2020).

Fourth, as a moderating variable, COVID-19 pandemic was measured by a dummy variable. If the responses were gathered during the COVID-19 pandemic period, ‘1’ was assigned, and if they were gathered before the COVID-19 pandemic period, ‘0’ was assigned.

Fifth, we also included seven control variables that have the potential to affect the IO of Chinese SMEs. We controlled for founder's international experience by measuring the natural logarithm of the yearly period of time spent working and living abroad (outside of China) of a founder. This control variable can influence young firms' posture on international market orientation and international strategic decision-making (Nielsen and Nielsen, 2011); in other words, the longer a founder's international experience, the more likely the SME is to be internationally oriented. Beijing was controlled for as the location of an SME, and it is one of the important locations for SMEs; thus, in our sample, 30% of SMEs (n = 113/373) are located in Beijing. Beijing is also one of the representative technology hubs in China, so this factor can influence SMEs' IO due to the potential for these Chinese SMEs' innovativeness (Wang and Wu, 2016). Firm ownership was controlled, too, since the ownership of a firm can influence its potential for innovativeness (Choi et al., 2011) and the extent of its mentality toward the outside world (Williams et al., 2020). Following the previous literature (Williams et al., 2020), we utilized four categories of firm ownership, namely private firms, state-owned enterprises, collectives, and joint ventures with foreign firms. Firm size was controlled, and this variable was a natural logarithm of the number of total employees of each firm. Firm age was also controlled, and this variable was a natural logarithm of the yearly age of each firm. A firm's size can affect its IO since a broader scope of total employees means that it has either wider domestic or overseas experience, or both, than a smaller firm (Child et al., 2017). Next, prior performance (over the previous three years) was controlled (Williams et al., 2020). To measure this subjective performance perception, we utilized a five-item, seven-point Likert scale to assess the after-tax return on assets (ROA), after-tax return on investment (ROI), sales growth rate, market share, and competitive position for the three years prior to t (Lee et al., 2010). High-tech industries was controlled and measured as a dummy variable. If an SME was a high-tech industry, ‘1’ was assigned, and ‘0’ otherwise. Larger and older SMEs are likely to have more tangible and intangible resources and experience than smaller and younger ones, and if their prior performance is higher, they are likely to have more resources and capabilities, as well as more confidence, to pursue more aggressive actions in international markets. In addition, SMEs in high-tech industries tend to have a higher level of innovativeness and more innovation capabilities when entering international markets since several international markets need high-tech products and components due to the demands of digitalization and industry 4.0 — especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, these controls are predicted to have positive impacts on the IO of Chinese SMEs.

4.3. Common method bias (CMB)

Our data may suffer from common method bias since this study was based on self-reports (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Accordingly, we employed a series of remedies suggested by Park et al. (2014) and Podsakoff et al. (2003) to address this problem. First, we collected separate responses with time gaps between answering the questionnaire by conducting the different survey waves. This was based on the procedural remedy aiming “to create a temporal separation by introducing a time lag between the measurement of the predictor and criterion variables” (Podsakoff et al., 2003, p. 887). Second, since CMB can occur under the condition of “obtaining the measures of both predictor and criterion variables from the same rater or source” (Podsakoff et al., 2003, p. 887), to operationalize the moderating variable of the COVID-19 pandemic, we used objective, secondary information on the event of the COVID-19 pandemic from different sources, including mass media. Third, we also re-sent the same questionnaire to different senior managers of 50 sample firms whose executives had responded to our earlier survey. We obtained 21 responses, and we did not uncover any significant differences between the two participants from each firm (Park et al., 2014, p. 972).

In addition, as the fourth remedy, we also performed a statistical test, namely Harman's single-factor test, on the items included in our model to confirm the minimum presence of CMB (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). If CMB exists in the data, either a single factor will emerge from a factor analysis of all measurement items included in the study or one general factor will account for most of the variance. However, the factor analysis revealed that neither of these was the case; specifically, the factor analysis revealed that the first of these (Eigenvalue = 4.64) explains 46.37% of the total variance, i.e., less than 50% of the total variance. Therefore, the factor analysis did not indicate the presence of a single background factor and thus it supports the validity of the data.

5. Results

The descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for the variables are shown in Table 5 . Because the highest correlation coefficient is 0.49 (p < 0.01), and this correlation is the one between an independent variable (foreign SNS use) and the dependent variable (IO), there is less concern of multicollinearity. Further, because the highest variance inflation factor (VIF) is 1.74, which is within the general acceptance level of 10 (Kennedy, 1992; Neter et al., 1985; Studenmund, 1992) as well as the stricter acceptance level of 5.3 that Hair et al. (1999) propose, we have confirmed that there is no collinearity problem influencing the data analysis. The correlation coefficients between foreign SNS use and IO (r = 0.49, p < 0.01), between foreign platform use and IO (r = 0.43, p < 0.01) and between domestic platform use and IO (r = 0.23, p < 0.01) are all positive and significant; meanwhile, the correlation coefficient between domestic SNS use and IO is negative and significant (r = −0.47, p < 0.01). These results are consistent with Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2. In contrast, the moderating variable (COVID-19 pandemic) is not significantly correlated with the independent variables (foreign versus domestic SNS use and foreign versus domestic platform use).

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation matrix.

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | International orientation | 4.33 | 0.99 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | SME's use of foreign SNS | 4.62 | 1.15 | 0.49⁎⁎ | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3 | SME's use of domestic SNS | 4.26 | 1.13 | −0.47⁎⁎ | 0.34⁎⁎ | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4 | SME's use of foreign platform | 3.63 | 1.33 | 0.43⁎⁎ | 0.24⁎⁎ | 0.23⁎⁎ | 1 | |||||||||

| 5 | SME's use of domestic platform | 4.57 | 1.24 | 0.23⁎⁎ | 0.12⁎ | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.12⁎ | 1 | ||||||||

| 6 | COVID-19 pandemic | 0.33 | 0.47 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 1 | |||||||

| 7 | Founder's international experience (ln) | 0.26 | 0.49 | 0.07 | 0.12⁎ | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1 | ||||||

| 8 | Beijing | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.21⁎⁎ | 0.18⁎⁎ | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.12⁎ | 0.01 | 0.06 | 1 | |||||

| 9 | Firm ownership | 1.36 | 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| 10 | Firm size (ln) | 4.68 | 1.77 | 0.19⁎⁎ | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.36⁎⁎ | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.22⁎⁎ | 0.12⁎ | 0.14⁎⁎ | 1 | |||

| 11 | Firm age (ln) | 1.78 | 0.97 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.13⁎⁎ | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 1 | ||

| 12 | Prior performance | 4.57 | 1.21 | 0.34⁎⁎ | 0.17⁎⁎ | 0.08 | 0.13⁎⁎ | 0.15⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.29⁎⁎ | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 1 | |

| 13 | High-tech industries (Dummy = 1) | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.16⁎⁎ | 0.14⁎⁎ | 0.03 | 0.25⁎⁎ | −0.16⁎⁎ | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.12⁎ | 0.25⁎⁎ | 0.17⁎⁎ | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1 |

Note: N = 373.

p < 0.05 (two-tailed significance levels).

p < 0.01 (two-tailed significance levels).

The regression results with standard errors and t-statistics corrected by White's heteroskedastic consistent covariance matrix used to test the hypothesized models are displayed in Table 6 . Model 1 includes the control variables only, Model 2 includes the main effects with all the independent and moderating variables, Model 3 includes the interaction terms between foreign SNS use and the COVID-19 pandemic and between domestic SNS use and the COVID-19 pandemic, and Model 4 includes the interaction terms between foreign platform use and the COVID-19 pandemic and between domestic platform use and the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, Model 5 is a full model, thus it contains all the variables and interaction terms.

Table 6.

Regression analysis results for international orientation.

| Variables | Hypo. | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | Sig. | β | SE | Sig. | β | SE | Sig. | β | SE | Sig. | β | SE | Sig. | ||

| Control variables | ||||||||||||||||

| Founder's international experience (ln) | 0.028 | 0.095 | 0.553 | 0.047 | 0.075 | 0.200 | 0.049 | 0.075 | 0.188 | 0.046 | 0.075 | 0.208 | 0.050 | 0.075 | 0.170 | |

| Beijing | 0.096 | 0.109 | 0.059 | 0.033 | 0.088 | 0.415 | 0.027 | 0.088 | 0.504 | 0.034 | 0.087 | 0.394 | 0.028 | 0.087 | 0.480 | |

| Firm ownership | 0.010 | 0.102 | 0.843 | 0.007 | 0.081 | 0.859 | 0.013 | 0.081 | 0.746 | 0.018 | 0.080 | 0.638 | 0.023 | 0.080 | 0.545 | |

| Firm size (ln) | 0.176 | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.052 | 0.022 | 0.197 | 0.055 | 0.022 | 0.171 | 0.047 | 0.022 | 0.241 | 0.054 | 0.022 | 0.175 | |

| Firm age (ln) | 0.016 | 0.046 | 0.721 | 0.007 | 0.051 | 0.892 | 0.011 | 0.051 | 0.830 | 0.021 | 0.050 | 0.667 | 0.028 | 0.050 | 0.565 | |

| Prior performance | 0.414 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.041 | 0.392 | 0.040 | 0.040 | 0.416 | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.426 | 0.034 | 0.040 | 0.478 | |

| High-tech industries (Dummy = 1) | 0.120 | 0.098 | 0.014 | 0.032 | 0.081 | 0.433 | 0.034 | 0.081 | 0.399 | 0.038 | 0.080 | 0.344 | 0.040 | 0.080 | 0.312 | |

| Independent variables | ||||||||||||||||

| SME's use of foreign SNS | Hypothesis 1 | 0.444 | 0.049 | 0.000 | 0.369 | 0.059 | 0.000 | 0.420 | 0.049 | 0.000 | 0.327 | 0.059 | 0.000 | |||

| SME's use of domestic SNS | −0.101 | 0.051 | 0.082 | −0.168 | 0.060 | 0.015 | −0.114 | 0.050 | 0.048 | −0.155 | 0.059 | 0.023 | ||||

| SME's use of foreign platform | Hypothesis 2 | 0.292 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.296 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.343 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.362 | 0.036 | 0.000 | |||

| SME's use of domestic platform | 0.118 | 0.032 | 0.004 | 0.127 | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.200 | 0.039 | 0.000 | 0.226 | 0.040 | 0.000 | ||||

| Moderating Variable | ||||||||||||||||

| COVID-19 pandemic | −0.007 | 0.104 | 0.895 | −0.063 | 0.340 | 0.695 | −0.648 | 0.407 | 0.001 | −0.460 | 0.444 | 0.030 | ||||

| Interactions | ||||||||||||||||

| SME's use of foreign SNS ∗ COVID-19 | Hypothesis 3 | 0.445 | 0.099 | 0.052 | 0.535 | 0.098 | 0.018 | |||||||||

| SME's Use of Domestic SNS ∗ COVID-19 | −0.377 | 0.099 | 0.078 | −0.217 | 0.100 | 0.312 | ||||||||||

| SME's use of foreign platform ∗ COVID-19 | Hypothesis 4 | −0.241 | 0.059 | 0.028 | −0.294 | 0.061 | 0.010 | |||||||||

| SME's use of domestic platform ∗ COVID-19 | −0.461 | 0.062 | 0.002 | −0.540 | 0.066 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Diagnostics | ||||||||||||||||

| N | 373 | 373 | 373 | 373 | 373 | |||||||||||

| R2 | 0.263 | 0.545 | 0.550 | 0.559 | 0.567 | |||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.249 | 0.529 | 0.532 | 0.542 | 0.548 | |||||||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.263 | 0.545 | 0.550 | 0.559 | 0.567 | |||||||||||

| F-statistic | 18.594 | 0.000 | 35.870 | 0.000 | 36.210 | 0.000 | 37.444 | 0.000 | 38.941 | 0.000 | ||||||

Notes: Standard errors and t-statistics corrected by White's heteroskedastic consistent covariance matrix. Standardized beta coefficients reported. All tests are two-tailed.

As can be seen in Model 1, Chinese SMEs located in Beijing (β = 0.096, p = 0.059) have a larger firm size (β = 0.176, p = 0.000) and higher prior performance (β = 0.414, p = 0.000), while Chinese SMEs in high-tech industries (β = 0.120, p = 0.014) are positively and significantly associated with IO. These findings support our predictions.

Hypothesis 1 assumes that SMEs' use of foreign SNS has a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic SNS. In Model 2, foreign SNS use is positively and significantly associated with IO (β = 0.444, p = 0.000), whereas domestic SNS use is negatively and significantly associated with IO (β = −0.101, p = 0.082). These results are in line with those of Models 3–5. Thus, these results consistently and strongly support Hypothesis 1. To test the significance of these results in Model 2, we conducted a beta slope test and the result was significant (Tdiffer = 9.564, p = 0.000); hence, Hypothesis 1 is consistently supported.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that SMEs' use of foreign platforms has a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic platforms. In Model 2, both foreign platform use and domestic platform use are positively and significantly associated with IO (βFplatform = 0.292, p = 0.000; βDplatform = 0.118, p = 0.004), but the beta coefficient is larger for foreign platform use than for domestic platform use, and the significance level of foreign platform use is higher than that of domestic platform use. Furthermore, these results are in line with those of Models 3–5. Thus, these results consistently support Hypothesis 2. To test the significance of the results in Model 2, we also conducted a beta slope test, and the result was significant (Tdiffer = 3.991, p = 0.000), thus consistently supporting Hypothesis 2.

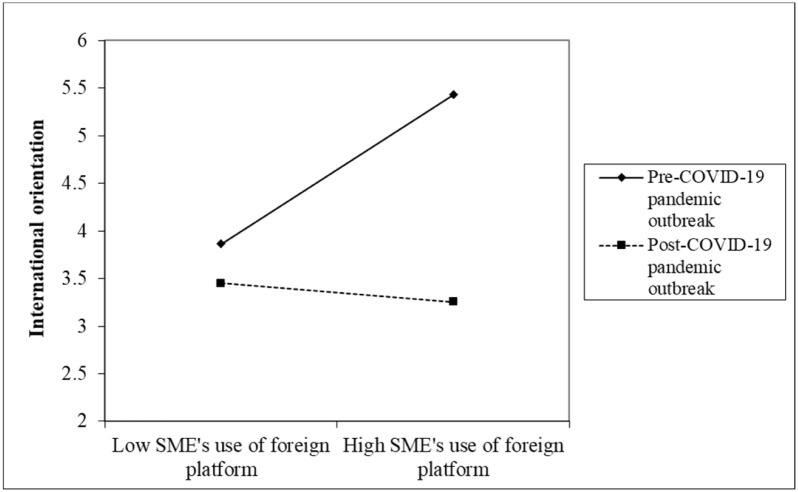

Hypothesis 3 predicts that even under the COVID-19 pandemic, SMEs' use of foreign SNS still has a stronger positive impact on their IO than their use of domestic SNS. In Model 3, the interaction term between SMEs' use of foreign SNS and the COVID-19 pandemic is positively and significantly associated with IO (β = 0.445, p = 0.052), whereas the interaction term between SMEs' use of domestic SNS and the COVID-19 pandemic is negatively and significantly associated with IO (β = −0.377, p = 0.078). Thus, the results in Model 3 support Hypothesis 3. Further, in Model 5, the interaction term between foreign SNS use and COVID-19 is positively and significantly associated with IO (β = 0.535, p = 0.018), while the interaction term between domestic SNS use and COVID-19 is negatively but non-significantly associated with IO (β = −0.217, p = 0.312); thus, Hypothesis 3 is consistently supported. To test the significance of these results in Model 3, we conducted a beta slope test and the result was significant (Tdiffer = 3.721, p = 0.000), thereby consistently supporting Hypothesis 3. To facilitate the interpretation of these interaction effects, we graph them in Fig. 1a, Fig. 1b (Aiken and West, 1991), which also consistently support Hypothesis 3.

Fig. 1a.

Interaction effect between SME's use of foreign SNS and COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 1b.

Interaction effect between SME's use of domestic SNS and COVID-19 pandemic.

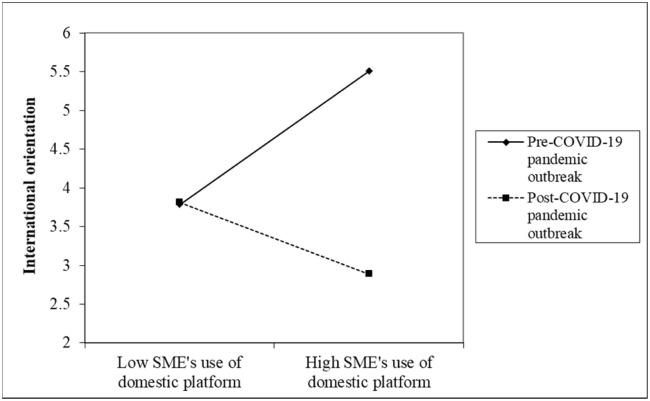

Hypothesis 4 predicts that the COVID-19 pandemic has a stronger negative moderation effect on the relationship between SMEs' use of domestic platforms and their IO than the relationship between their use of foreign platforms and their IO. In Model 4, the interaction terms between both SMEs' use of foreign platforms and the COVID-19 pandemic (β = −0.241, p = 0.028) and SMEs' use of domestic platforms and the COVID-19 pandemic (β = −0.461, p = 0.002) are negatively and significantly associated with IO. However, the beta coefficient of the interaction term between domestic platform use and COVID-19 is larger than that between foreign platform use and COVID-19, and the significance level of the interaction term between domestic platform use and COVID-19 is higher than that between foreign platform use and COVID-19. These results are also in line with those in Model 5, thereby consistently supporting Hypothesis 4. To test the significance of the results in Model 4, we performed a beta slope test and the result was non-significant (Tdiffer = 0.927, p = 0.355), thus weakly supporting Hypothesis 4. Fig. 2a, Fig. 2b illustrate these interaction effects graphically. Fig. 2a, Fig. 2b consistently support Hypothesis 4.

Fig. 2a.

Interaction effect between SME's use of foreign platform and COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 2b.

Interaction effect between SME's use of domestic platform and COVID-19 pandemic.

6. Discussion and conclusion