Abstract

Introduction

Tracheostomy in patients with COVID-19 is a controversial and difficult clinical decision. We hypothesized that a recently validated COVID-19 Severity Score (CSS) would be associated with survival in patients considered for tracheostomy.

Methods

We reviewed 77 mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients evaluated for decision for percutaneous dilational tracheostomy (PDT) from March to June 2020 at a public tertiary care center. Decision for PDT was based on clinical judgment of the screening surgeons. The CSS was retrospectively calculated using mean biomarker values from admission to time of PDT consult. Our primary outcome was survival to discharge, and all patient charts were reviewed through August 31, 2021. ROC curve and Youden index were used to estimate an optimal cut-point for survival.

Results

The mean CSS for 42 survivors significantly differed from that of 35 nonsurvivors (CSS 52 versus 66, P = 0.003). The Youden index returned an optimal CSS of 55 (95% confidence interval 43-72), which was associated with a sensitivity of 0.8 and a specificity of 0.6. The median CSS was 40 (interquartile range 27, 49) in the lower CSS (<55) group and 72 (interquartile range 66, 93) in the high CSS (≥55 group). Eighty-seven percent of lower CSS patients underwent PDT, with 74% survival, whereas 61% of high CSS patients underwent PDT, with only 41% surviving. Patients with high CSS had 77% lower odds of survival (odds ratio = 0.2, 95% confidence interval 0.1-0.7).

Conclusions

Higher CSS was associated with decreased survival in patients evaluated for PDT, with a score ≥55 predictive of mortality. The novel CSS may be a useful adjunct in determining which COVID-19 patients will benefit from tracheostomy. Further prospective validation of this tool is warranted.

Keywords: COVID-19, Percutaneous dilational tracheostomy

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is responsible for a worldwide pandemic with almost 200 million cases and over 600,000 deaths in the United States alone.1 Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection have disease severities that range from mild symptoms to life-threatening pulmonary and other organ system manifestations necessitating intensive care unit admissions. These patients often have a complex hospital course with prolonged intubation and multisystem organ failure, requiring tracheostomy, acute dialysis, or even extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). The benefits of tracheostomy when performed during the standard accepted timeframe (less than 10-14 d) in patients requiring long-term mechanical ventilation have been well documented and include decreased sedation needs, improved ventilator weaning, and earlier rehabilitation. These favorable outcomes have been similarly documented in the COVID-19 patient population.2, 3, 4, 5 However, the risk of a tracheostomy procedure as a “super-spreader event” must be weighed against the potential benefits in these critically ill patients. Prior research of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS/SARS-CoV-1) infected patients identified endotracheal intubation as a high-risk procedure, with an odds ratio (OR) of 6.6 for the transmission of the virus.6 Several studies have demonstrated significant risk of infection and contamination with the virus after endotracheal intubation despite the use of personal protective equipment.7 , 8

Because of the well-documented risk to providers performing airway procedures, patient selection becomes paramount. It can be difficult for the acute care surgeon to decide which critically ill patients will survive their COVID-19 hospitalization and thus derive the most benefit from a tracheostomy. To facilitate this clinical decision-making, we used a novel COVID-19 severity score (CSS). The CSS includes patient age and laboratory values of procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP), and D-dimer levels. This score was initially validated to identify high-risk COVID-19 patients who would require inpatient admission, calculating a score of 27 as the cut-off for hospitalization. The scoring system was later adapted to predict disease severity and assess mortality risk in those more critically ill hospitalized patients.9

We hypothesized that patients with higher CSS would be less likely to survive to discharge and sought to determine whether an optimal score can be used to assist with the preoperative evaluation for tracheostomy.

Methods

Study design, participants, and inclusion criteria

We included all SARS-CoV-2–infected mechanically ventilated patients evaluated for percutaneous dilational tracheostomy (PDT) from March to June 2020 at a public tertiary care center, and all patients were followed through August 31, 2021. Patients were selected to undergo tracheostomy based on the clinical judgment of the screening surgeons using the following general parameters: minimum of 6 d of intubation, a fractional inspired oxygen concentration (FiO2) of ≤60%, positive end-expiratory pressure of ≤12, no significant organ dysfunction except acute kidney injury, and minimal vasopressor requirements (<5 mcg/kg/min of norepinephrine, or equivalent). An Institutional Review Board–approved waiver was obtained to assess outcomes after tracheostomy in COVID patients.

Data points and outcome measures

Demographic data, including age, gender, ethnicity, medical comorbidities, and body mass index (BMI) at admission, as well as Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score at the time of tracheostomy consultation, were retrospectively obtained through electronic medical record and recorded for both patients who underwent PDT and those who were screened but not offered PDT. The CSS was calculated using the mean value of all available biomarker data (PCT, CRP, and D-dimer) from admission to tracheostomy or to the time of tracheostomy consult in those not offered PDT. The primary outcome measure was survival to discharge.

Statistical analysis

We performed descriptive statistics for the demographic characteristics of the study population. Continuous normally distributed variables were reported as a mean and standard deviation, whereas skewed variables were reported as a median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were reported as counts and proportions. We used unpaired Student’s t-test for analysis of continuous normally distributed variables and Pearson's chi-squared test for the categorical data. The Mann–Whitney test was used for analysis of continuously skewed data. Two-sided tests were considered statistically significant for P < 0.05. The optimal cut-off value for survival using the biomarker-based CSS score10, 11, 12, 13 was estimated using the R cutpointr library based on the Youden index, sensitivity and specificity, and area under curve (AUC), with a bootstrap estimate for 95% confidence interval (CI). The Youden index is a statistical measure commonly used for biomarkers or biomarker-based tests to evaluate their effectiveness in detecting a disease. It balances the specificity and sensitivity of a test to provide a percentage between 0 and 100, with anything >50% indicating an effective test. It also provides an optimal threshold value or cut-off point. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board.

Results

Fifty-five of the 77 patients evaluated underwent PDT, and the remaining 22 patients were screened and not considered appropriate PDT candidates. The demographic data of these dichotomized groups are presented in Table 1 . There were more patients in the Other ethnicity category (mainly Bangladeshi and South Asian descent) in the group that did not undergo tracheostomy, but there were no other significant differences between the groups in terms of age, gender, ethnicity distribution, medical comorbidities, and BMI at admission. Patients in the group who underwent tracheostomy had statistically significantly lower mean SOFA scores than those who did not undergo the intervention (6.4 versus 10; P ≤ 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic data of tracheostomy and nontracheostomy groups.

| Individual-level variables | Tracheostomy (n = 55) | No tracheostomy (n = 22) | P-value (α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 58.4 (±10.9) | 63.2 (±7.8) | 0.64 |

| Male (%) | 44 (80%) | 14 (63%) | 0.14 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| Black/African American | 16 (29.1%) | 5 (22.7%) | 0.70 |

| Asian | 3 (5.5%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0.86 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 33 (60%) | 11 (50%) | 0.42 |

| Caucasian | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0.85 |

| Others | 1 (1.8%) | 4 (18.2%) | 0.008 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 28 (50.9%) | 14 (63.6%) | 0.71 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 18 (32.7%) | 10 (45.5%) | 0.29 |

| CAD/CHF | 8 (14.5%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0.52 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (18.2%) | 6 (27.3%) | 0.37 |

| Chronic respiratory disease (COPD, asthma) | 6 (10.9%) | 1 (4.5%) | 0.38 |

| CVA/stroke | 4 (7.3%) | 2 (9.1%) | 0.79 |

| Cancer history | 5 (9.1%) | 2 (9.1%) | 1.00 |

| BMI at admission | 30.2 ( ± 7.1) | 28.7 ( ± 7.3) | 0.38 |

| SOFA score at consult | 6.4 ( ± 2.8) | 10 ( ± 2.8) | <0.001 |

Fifty-five of 77 patients underwent tracheostomy. The group who did not receive tracheostomy had significantly higher SOFA scores, 6.4 versus 10, p ≤ 0.001. There were more patients in the Other ethnicity category who did not undergo tracheostomy, one versus four patients, P = 0.008. The groups were otherwise similar.

CAD = coronary artery disease; CHF = congestive heart failure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary diesease; CVA = cerebrovascular accident.

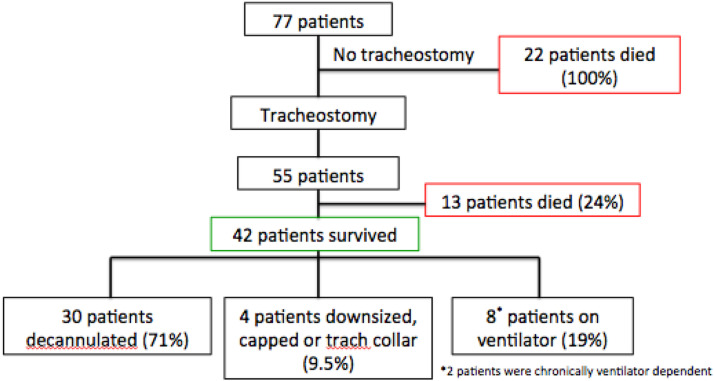

Of those who received a PDT, 76% (42/55) survived to discharge. Conversely, there was 100% mortality (22/22) in the nontracheostomy group. At the time of discharge, 30 patients were decannulated, four patients were downsized, capped or on tracheostomy collar, and the remaining eight survivors had persistent ventilator requirements (Fig. 1 ). One of the patients had a preexisting medical condition requiring chronic ventilator support, and another patient was also ventilator dependent before tracheostomy secondary to an in-hospital arrest. By the end of the study period, an additional three patients were deceased, one from each subgroup of survivors. The patient in the decannulated group died from a newly diagnosed aggressive metastatic cancer. The patient in the ventilator group died from his preexisting medical condition. Fourteen patients were lost to follow-up. Nearly 60% of patients were doing well on chart review, with the majority of those patients in the decannulated group.

Fig. 1.

Outcomes of patients who underwent tracheostomy. Overall survival for all patients was 55%. Of the group who underwent tracheostomy, there was a 76% survival rate. There was 100% mortality in the nontracheostomy group. At the time of discharge, 71% of survivors were decannulated, 9.5% were downsized, capped, or on tracheostomy collar, and 19% had persistent ventilator requirements.

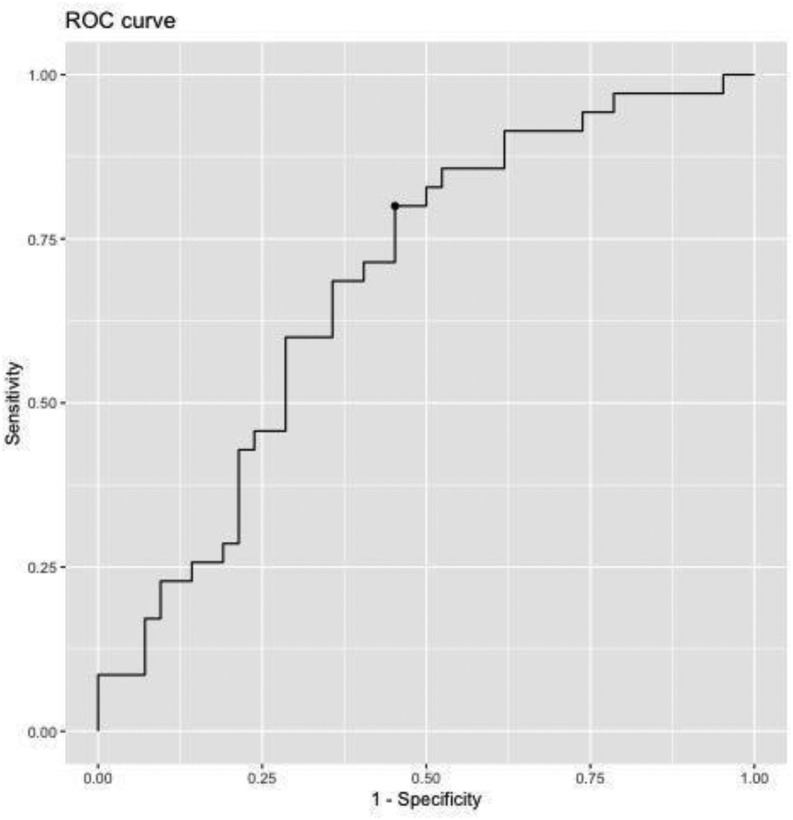

The mean CSS for survivors versus nonsurvivors was significantly lower in the survivor group (CSS 52.4 versus 66.4; 95% CI 4.8-23.2; P = 0.003). The Youden index yielded an optimal CSS cut-off value of 55 (AUC 0.7; 95% CI 43-72; Fig. 2 ). The CSS was associated with approximately 3% less likely log odds of discharge (OR = 0.97; 95% CI 0.94-0.99; P = 0.005), meaning there was a 3% decrease in the likelihood of survival to discharge for each CSS point above 55.

Fig. 2.

Youden index, J-statistic 0.7, 95% confidence interval 43-72. The test has a sensitivity of 0.8 and specificity of 0.6. The optimal cut-point for the CSS was 55, allowing the data to be further analyzed into risk-dichotomized groups, <55 deemed the lower risk group and ≥55 deemed the high risk group.

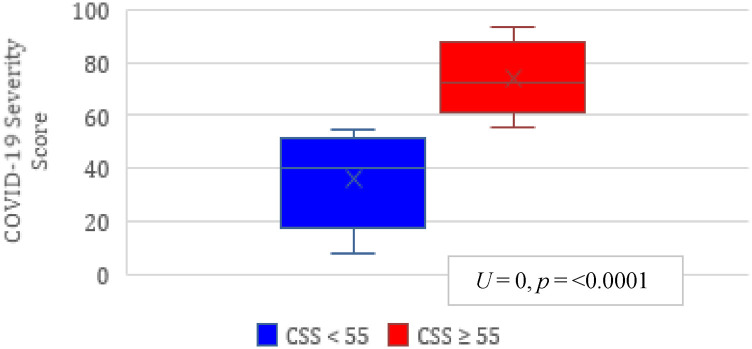

Patients in the two CSS groups, lower risk <55 (n = 31) and high risk ≥55 (n = 46), were demographically similar with respect to gender, ethnicity, medical comorbidities, and admission BMI. The high risk group was significantly older (62.6 y versus 55.7, P = 0.007) and had higher SOFA scores at the time of the tracheostomy consult (8.54 versus 5.84, P = 0.003; Table 2 ). The median CSS was 40 (IQR 27, 49) in the lower risk group and 72 (IQR 66, 93) in the high risk group (U = 0, P = 0.000, r = 0.84; Fig. 3 ).

Table 2.

Demographic data for stratified CSS groups.

| Individual-level variables | CSS <55 (n = 31) | CSS ≥55 (n = 46) | P-value (α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 55.7 (±11.7) | 62.6 (±8.3) | 0.007 |

| Male (%) | 23 (74%) | 35 (76%) | 0.84 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| Black/African American | 9 (29%) | 12 (26%) | 0.77 |

| Asian | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.15 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 16 (51.6%) | 28 (61%) | 0.41 |

| Caucasian | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.34 |

| Other | 1 (3.2%) | 4 (8.7%) | 0.34 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 14 (45%) | 28 (61%) | 0.17 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 9 (29%) | 19 (41.3%) | 0.27 |

| CAD/CHF | 2 (6.5%) | 8 (17.4%) | 0.16 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 4 (12.9%) | 12 (26%) | 0.16 |

| Chronic respiratory disease (COPD, asthma) | 3 (9.7%) | 4 (8.7%) | 0.88 |

| CVA/stroke | 2 (6.5%) | 4 (8.7%) | 0.93 |

| Cancer history | 3 (9.7%) | 4 (8.7%) | 0.88 |

| BMI at admission | 29.3 (±8.1) | 30.1 (±6.5) | 0.66 |

| SOFA score at consult | 5.84 (±3.2) | 8.54 (±2.8) | <0.001 |

Fig. 3.

CSS range by risk stratification group. The median CSS for lower risk group 40 (range 27-49), the median CSS for high risk group 72 (range 66-93). Mann–Whitney U test analysis with U = 0, P < 0.001, r = 0.84. U = 0, P ≤ 0.0001.

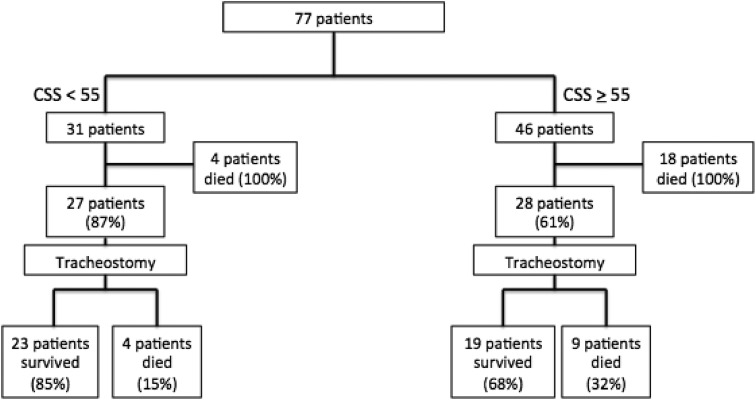

There were a total of 35 deaths in the study population. Eight deaths in the lower CSS group for a survival rate of 74% (23/31) and 27 deaths in the high CSS group for a survival rate of 41% (19/46). In the lower CSS group, 27 of the 31 patients (87%) underwent tracheostomy. Of those, 85% survived to discharge (23/27). Four patients (15%) in the tracheostomy group and all four of the patients in the nontracheostomy group (100%) died. In the high CSS group, 28 of the 46 (61%) patients underwent tracheostomy. Of those, 68% survived to discharge (19/28). Nine patients (32%) who received a tracheostomy died, and all 18 of the patients in the nontracheostomy group (100%) died (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Survival by CSS risk stratification group. A total of 35 deaths with eight in the lower risk group and 27 in the high risk group. Eighty-five percent of the patients who underwent tracheostomy in the lower risk group survived compared with 68% of those in the high risk group. All patients not offered a tracheostomy died.

In comparing the SOFA scores of lower risk and high-risk CSS groups, the score was only significantly different in the patients who underwent tracheostomy and survived (5.04 versus 6.89; P = 0.02). There was no significant difference in the SOFA scores of the two risk groups in patients who underwent tracheostomy and died (7.5 versus 8.5; P = 0.58) or those who did not receive the intervention (8.75 versus 10.3; P = 0.5).

Subset analysis comparing the survivors and nonsurvivors of the high risk group who received a tracheostomy found that patients who survived were significantly younger (59 y versus 68 y; P = 0.008). There was no significant difference in gender, ethnicity, BMI, SOFA score, and number of comorbidities. There was a significant difference of cancer history in the nonsurvivors; however, the sample size was very small and only represented two patients of the 28 (0% versus 22%; P = 0.03; Table 3 ). Overall, patients with a CSS ≥55 had 77% lower odds of survival to discharge (OR = 0.2; 95% CI 0.1-0.7).

Table 3.

Demographics of survivors versus nonsurvivors who underwent tracheostomy in CSS ≥55 group.

| Individual-level variables | Survivors (n = 19) | Nonsurvivors (n = 9) | P-value (α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 59.4 (±8.5) | 68 (±6.6) | 0.008 |

| Male gender (%) | 15 (79%) | 8 (89%) | 0.52 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Black/African American | 6 (32%) | 2 (22%) | 0.61 |

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 13 (68%) | 6 (67%) | 0.93 |

| Caucasian | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Other | 0 | 1 (11%) | 0.14 |

| BMI at admission | 30.6 (±6.7) | 29 (±5.5) | 0.50 |

| SOFA score | 6.9 (±2.2) | 8.6 (±2.5) | 0.11 |

| ≥1 comorbidity | 15 (79%) | 6 (67%) | 0.48 |

| >3 comorbidities | 4 (21%) | 3 (33%) | 0.48 |

| Cancer history (%) | 0 | 2 (22%) | 0.03 |

Nonsurvivors were significantly older, 59 versus 68 y, P = 0.008. Nonsurvivors had significantly more cancer history 0% versus 22%, P = 0.03.

Discussion

With increasing mortality rates around the world from COVID-19 infections, many researchers have attempted to identify factors associated with increased risk of death in an effort to help triage and risk stratify these critically ill patients.

In an effort to delineate risk factors associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients, we used a novel scoring system (CSS) developed specifically for these patients. We applied this scoring system to admitted COVID-19–infected patients who were undergoing tracheostomy evaluation. A higher CSS was associated with decreased survival to discharge in patients, with a CSS ≥55 predictive of mortality. In the subset analysis of the high risk group, age was the only significant factor associated with survival, which correlates with multiple studies citing increasing age as a risk factor for worse outcomes and mortality.

The decision to perform a tracheostomy in this study population was a clinical one and based on conventionally accepted parameters for PDT. The appropriateness of their clinical assessment is mirrored in the survival outcomes presented in Table 3. Of the 55 tracheostomies performed during the study period, there were a total of 13 deaths (24%), with nine of those deaths (69%) occurring in the high-risk CSS group. There was an overall 76% survival rate for the study population based on physician evaluation. This number increases to 85% when risk stratifying the patients retrospectively by their CSSs and analyzing the lower risk group. Based on clinical parameters and surgeon judgment, some patients were not offered an intervention, and there were no survivors in this group. The CSS may serve as an objective evaluation that can guide clinical decision-making and substitute for the advanced training and experience that is otherwise required for such clinical assessments.

The CSS has been validated with outpatient data, using age and three laboratory values, with a score greater than 27 identifying higher risk patients who would require hospital admission and further monitoring (AUC 0.95, 95% CI 0.92-0.98). It was shown to predict mortality among hospitalized patients and could be used to monitor patients over time and track the trend of their biomarkers during their hospital course.

The scoring system was both internally and externally validated (0.95 and 0.97, respectively), reflecting its generalizability for different patient demographics and patient care settings.8

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals relied on biomarker data to guide care plans and treatment protocols, with cytokine biomarkers driving the development of targeted therapies. Biomarkers have also been used to risk stratify or further characterize the severity of a disease or illness. Elevated levels of D-dimer are often seen with thrombotic events, CRP with infection or nonspecific inflammation, and PCT with bacterial infection or sepsis. These values can be trended over a patient's treatment course and used to guide duration of therapy. A study from a group in Wuhan, China, noted a significant increase in biomarker levels such as CRP, D-dimer, and PCT in COVID-19–infected patients who died compared with survivors (AUC 0.87, 0.866, 0.90, respectively).14 Other studies found elevated CRP levels in all deceased critically ill COVID-19–infected patients and elevated D-dimer levels to be a prognostic factor associated with risk of death.15 , 16 In the initial study of the CSS, PCT was also noted to be a predictor of mortality, with both PCT and CRP levels significantly elevated in patients who died from COVID-19 infection compared with survivors (0.05 versus 0.55, P < 0.001 for PCT and 18.5 versus 140.3, P < 0.001 for CRP).17

Using a scoring system initially validated for intensive care unit patients, the SOFA score was co-opted for COVID-19–infected patients with mixed results. Initially developed for sepsis, the SOFA score evaluates six organ systems equally, with only three systems (pulmonary, renal, and hepatobiliary) correlating with mortality in COVID patients. Furthermore, platelet levels may not be the most accurate assessment of the coagulation system dysfunction, and as such, this scoring system may underestimate the significant impact of coagulopathy in this patient population. Some studies found the SOFA score to be a poor marker for mortality prediction,18 whereas others reported strong predictive accuracy.19 , 20 Within our study population, the SOFA score was higher in patients who did not undergo tracheostomy and in the high risk group stratified by the Youden index. Although there was a significant difference in the SOFA score of the patients who underwent tracheostomy and survived in the risk-stratified groups, there was no difference in the groups who underwent tracheostomy and died or in the subset analysis of the survivors in the high risk group, limiting its generalizability and utility in our study population.

The study is limited by its relatively small sample size, with a total of 77 patients. Comparing the patients who received a tracheostomy to those who did not, further risk stratification by the severity score yielded even smaller groups, with unequal sample sizes. No patients survived who did not receive a tracheostomy, which inherently introduces selection bias. Throughout the duration of the study, treatment protocols for COVID-19 were rapidly changing in accordance with guidelines recommendations, which may have also had an undetectable impact on outcomes. Different laboratory values were trended at different points during study period, with not all patients having every data point for each day of their hospitalization. To more accurately reflect the patient's overall clinical status and illness severity throughout their hospital course, all data points available were averaged and used in the score calculator to provide a single CSS. With more available data points, the severity score could be trended over the course of the patient's hospitalization and may help further define those who survive to discharge. The scoring system is limited by maximum input values for the laboratory data, accepting up to a CRP of 300 μg/mL, PCT of 9 ng/mL, and D-dimer of 10,000 ng/mL. Seven patients, all with CSS ≥55, had data values greater than the upper limit for the score calculator, with resulting severity scores lower than expected.

Three of these patients died, and none of them received a tracheostomy.

Conclusions

The novel CSS may be a useful adjunct along with careful clinical evaluation in determining which mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients will benefit from tracheostomy. Further prospective validation of this novel scoring tool is warranted.

Author contributions

A.H. contributed to data collection and analysis, article writing, and critical revisions. L.K. contributed to data collection and analysis, article writing, and critical revisions. C.D., C.H., B.M., J.T.M., and M.M. contributed to data collection and analysis and critical revisions. C.H. contributed to data collection and analysis and critical revisions. V.M. contributed to data analysis and critical revisions. A.U. contributed to data analysis and critical revisions. M.B. contributed to data collection and analysis, article writing, and critical revisions.

Disclosure

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control CDC COVID data tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data- tracker/#datatracker-home Available at:

- 2.Angel L., Kon Z., Chang S., et al. Novel percutaneous tracheostomy for critically ill patients with Covid-19. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:1006–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGrath B.A., Brenner M.J., Warrillow S., et al. Tracheostomy in the Covid-19 era: global and multidisciplinary guidance. Lancet Respir Med 202) 2020;8:717–725. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30230-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breik O., Nankivell P., Sharma N., et al. Safety and 30-day outcomes of tracheostomy for Covid-19: a prospective observational cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:872–879. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosano A., Martinelli E., Fusina F., et al. Early percutaneous tracheostomy in coronavirus disease 2019: association with hospital mortality and factors associated with removal of tracheostomy tube at ICU discharge. A cohort study on 121 patients. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:261–270. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran K., Cimon K., Severn M., et al. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Boghadly L., Wong D.J.N., Owen R., et al. Risks to healthcare workers following tracheal intubation of patients with COVID-19: a prospective international multicenter cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2021;75:1437–1447. doi: 10.1111/anae.15170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman O., Meir M., Shavit D. Exposure to a surrogate measure of contamination from simulated patients by emergency department personnel wearing personal protective equipment. JAMA. 2020;323:2091–2093. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McRae M.P., Dapkins I.P., Sharif I., et al. Managing COVID-19 with a clinical decision support tool in a community health network: algorithm development and validation. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/22033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruopp M.D., Perkins N.J., Whitcomb B.W., Schisterman E.F. Youden index and optimal cut-point estimated from observations affected by a lower limit of detection. Biom J. 2008;50:419–430. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200710415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkins N.J., Schisterman E.F. The Youden index and optimal cut-point correct for measurement error. Biom J. 2005;47:428–441. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fluss R., Faraggi D., Reiser B. Estimation of the Youden index and its associated cutoff point. Biom J. 2005;47:458–472. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200410135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiele C., Hirschfeld G. cutpointr: improved estimation and validation of optimal cutpoints in R. J Stat Softw. 2021;98:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai T., Tu S., Wei Y., et al. Clinical and laboratory factors predicting the prognosis of patients with COVID- 19: an analysis of 127 patients in Wuhan, China. SSRN. 2020;127 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang B., Zhou X., Qiu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of 82 cases of death from COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McRae M.P., Simmons G.W., Christodoulides N.J., et al. Clinical decision support tool and rapid point-of-care platform for determining disease severity in patients with COVID-19. Lab Chip. 2020;20:2075–2085. doi: 10.1039/d0lc00373e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raschke R., Agarwal S., Rangan P. Discriminant accuracy of the SOFA score for determining the probable mortality of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation. JAMA. 2021;325:1469–1470. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S., Yao N., Qiu Y., He C. Predictive performance of SOFA and qSOFA for in-hospital mortality in severe novel coronavirus disease. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38:2074–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez A.C., Dewaswala N., Ramos Tuarez F., et al. Validation of SOFA score in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;158:A613. [Google Scholar]