Abstract

The present study explores the impact of smartphone use on course comprehension and the psychological well-being of students during class. Students in four classes (N = 106) were assigned to either a control group or quasi-experimental group. Students in the quasi-experimental group were instructed to place their smartphones on the front desk upon entering the class, while the control group had no instructions regarding smartphone use. Students filled out a brief survey about their course comprehension and psychological state (anxiety and mindfulness) during class. Results indicated that students whose smartphones were physically removed during class had higher levels of course comprehension, lower levels of anxiety, and higher levels of mindfulness than the control group. This study gives a comprehensive picture of the impact of smartphone use on students’ psychological well-being in the classroom. The findings can aide educators in curriculum design that reduces technology use in order to improve the student learning experience.

Keywords: Smartphones, College students, Course comprehension, Learning, Student mindfulness, Student anxiety

The smartphone has become an integral part of society, including our educational and professional lives. Smartphone use is highest amongst people aged 18–29, and therefore is highly represented in the University setting. Statistics show that 97% of students own a smartphone (Pew Research Center, 2021), and 95% of students bring that smartphone to class (Tindell & Bohlander, 2012). Given the frequency of smartphone use in the college student population, it is not surprising ample research has investigated smartphone use in the University setting – both inside and outside the classroom. There is a large body of literature that looks at smartphone use and academic performance. Smartphone is associated with lower GPA’s, both in self-reports (Ibrahim et al., 2018; Katz & Lambert, 2016; Kim et al., 2019), and actual GPA (Hawi & Samaha, 2017). Research has also found that smartphone use is associated with poor sleep quantity (Demirci et al., 2015), life satisfaction (Lachmann et al., 2018), and anxiety, loneliness, and depression (Boumosleh & Jaalouk, 2017) in college students.

Within the classroom, smartphones can often be a cause of distraction, as students use the phone during class to check social media (Gupta & Irwin, 2016), multi-task (Sana et al., 2013), or contact friends (Tindell & Bohlander, 2012). These activities deflect from instruction, and impede student learning. Although a substantial body of research has found that cell phone use in the classroom is associated with lower academic achievement (e.g. Amez & Baert, 2020), fewer studies have examined the effects of cell phone use on students’ psychological well-being in the classroom setting, and even fewer have examined the impact of cell phone use using a quasi-experimental paradigm. The present study aims to further explore the impact that the smartphone has on course comprehension, and expand the research by investigating how smartphone use in the classroom impacts the psychological well-being of students during class.

Research on smartphones in the classroom is mixed, and primarily focuses on academic performance. On one hand, when used properly, smartphones are associated with better academic performance. The convenience of the smartphone allows students to access the internet anywhere, letting them connect with information, assignments, and e-mails related to school almost instantly (Lepp et al., 2014). Also, social networking sites and online applications contribute to easy communication amongst students and the professor, which allows for seamless collaboration (Chen & Ji, 2015). Some research has found that the more students engage in course-related activities on their phone, the more likely they are to seek out additional information to comprehend the material (Rashid & Asghar, 2016).

On the other hand, the smartphone is often a distraction for students, which takes away from the classroom experience and retention of information. The smartphone can serve as a source of entertainment for students, rather than a working instrument. It has been found to draw students’ attention away from study time and time spent on homework and assignments (Junco & Cotton, 2012), ultimately taking away from the learning experience. Given this information, it is not surprising that smartphone use is associated with lower self-reported (Ibrahim et al., 2018; Katz & Lambert, 2016; Kim et al., 2019), and actual GPA (Hawi & Samaha, 2017; see Amez and Baert (2020) for full literature review).

There is ample research on the smartphones’ impact on academic performance, but less is known about its potential impact on course-related psychological well-being. Anxiety is particularly problematic among college students, as it often impedes the learning experience (Mazzone et al., 2007). 60.8% of college students report feeling overwhelming amounts of anxiety last year alone (American College Health Association, 2022).

In general, research has found a negative correlation between smartphone use and psychological well-being, specifically in anxiety and depression (e.g. Demirci et al., 2012). While the majority of this research have examined smartphone use and overall levels psychological well-being, some studies have examined this relationship in the classroom setting. Again, the literature has found a negative relationship (e.g. Boumosleh & Jaalouk, 2017) Two, not mutually exclusive, explanations for this relationship have been suggested. One, the barrage of alerts on our phone and constant streams of information creates feelings of anxiousness, and distraction from the lecture (Al-Furaih & Al-Awidi, 2021). Two, smartphones in the class can create anxiety due to FOMO, or fear of missing out (e.g. Yildirim & Correia, 2015), as students notice other things going on amongst friends while they are in-class. Given these distractions, removing the smartphone from the classroom experience will likely reduce student anxiety (Stankovic et al., 2021).

Research has also found that mindfulness – defined as the quality or state of being conscious or aware of present surroundings—can significantly reduce anxiety (Hoffman et al., 2010). This is particularly true in the classroom. Mindfulness during lectures has been found to be associated with better grades (Caballero et al., 2019), and better overall psychological health while learning (Mahfouz et al., 2018). With the distraction of the smartphone, it is likely that smartphone use reduces students’ mindfulness during lectures, inhibiting the learning experience and increasing anxiety.

Due to the conflicting research on the effects of smartphone use in the classroom, the current study seeks to clarify and expand the impact of academic achievement by investigating the effects of smartphone use on course comprehension using a quasi-experimental procedure. In addition, we hope to explore the effects of smartphone use on psychological well-being – operationally defined as classroom anxiety and mindfulness. In the present study, students were assigned to either a quasi-experimental group, where students were instructed to leave their smartphone on the windowsill / desk of the instructor as they entered the class – ensuring a physical distance from their phone – or a control group, where they received no instructions on smartphone use. Students then completed a survey to measure levels of course comprehension and psychological well-being based on these conditions. The present study tested three hypotheses:

H1: Based on previous research, students who were physically distanced from their cell phones would be less distracted, and therefore have significantly higher rates of course comprehension then students in the control group.

H2: Students who were physically distanced from their cell phones would be less distracted and more engaged in the lecture, therefore having lower levels of anxiety then students in the control group.

H3: Students who were physically distanced from their cell phones would be less distracted, and therefore have significantly higher rates of mindfulness then students in the control group.

Methods

Participants

Participants were undergraduate students at the [BLINDED], a primarily undergraduate institution in New York City. Four content courses in the Behavioral Sciences Department were selected for participation in the study in Spring 2020. The courses included were Introduction to Sociology (n = 54), Dynamics of Violence (n = 18), Educational Psychology (n = 21), and Health Psychology (n = 15). There were 36 participants (33%) in the quasi-experimental group, and 72 in the control group (67%).

The participants (N = 108) included 59 females (55%) and 49 males (45%). Of this total, 44 were Asian American (41%), 32 identified as White / Caucasian (30%), 11 identified as Latinx or Hispanic (10%), 11 identified as Black / African American (10%), and 10 were unidentified (10%). Students ranged in age from 18 to 47 (M = 20.2, SD = 3.6). Ethical approval was granted by [BLINDED] Review Board (Protocol number: ESB 1520).

Procedure

Of the four behavioral science courses, two courses – Introductory Sociology and Dynamics of Violence – were treated as controls. Students in these courses did not receive any instructions or specific restrictions on their smartphone use. Educational Psychology and Health Psychology were assigned as the quasi-experimental condition. At the beginning of class each day, students were instructed to place their phones on a desk at the front of the classroom before the lecture was given. The phones could not be physically on them or accessed throughout the duration of the course. In the beginning of March 2020 – after six weeks of in-person participation in the course—all students completed a self-report survey that measured their course comprehension, mindfulness, and anxiety throughout the course.

Instruments

Course comprehension

A 10-item questionnaire was created, which specifically assessed how engaged the student felt in the course material during the course. Sample items included, “I feel confident in my knowledge of the course material,” or “It is clear to me what concepts I do not understand after the lecture.” Questions ranged on a scale from “1” – strongly disagree – to “5” – strongly agree. The items were averaged and reliability was very good (α = 0.86). A reliability analysis was conducted, and was best when all 10 items were included in the scale. In addition, a principal component analysis was conducted to investigate construct validity. All ten items had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 and the cumulative variance explained was 50.08%. See Appendix 1 for questions.

Anxiety

A 7-item questionnaire was created, which specifically assessed students’ anxiety during class. Sample items included “During class, I feel nervous, anxious, or on edge” or “During class, I have trouble relaxing.” Questions ranged on a scale from “1” – not at all – to “5” – all the time. The items were averaged and reliability was very good. (α = 0.93). A reliability analysis was conducted, and was best when all 7 items were included in the scale. In addition, a principal component analysis was conducted to investigate construct validity. All seven items had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 and the cumulative variance explained by the 7 items was 71.49%. See Appendix 2 for questions.

Mindfulness

A 10-item questionnaire was created which specifically assessed students’ mindfulness during their respective course. Sample items included, “I take notes on autopilot, without truly processing the information” and “I am focused on outside responsibilities or tasks during class.” Questions ranged on a scale from “1” – strongly disagree – to “5” – strongly agree. The items were averaged and reliability was very good. (α = 0.94). A reliability analysis was conducted, and was best when all 10 items were included in the scale. In addition, a principal component analysis was conducted to investigate construct validity. All ten items had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of 1 and the cumulative variance explained was 64.49%. See Appendix 3 for questions. See Table 1 for correlations between study variables.

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations, means, & standard deviations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | Means | Standard Deviations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Course Comprehension | –- | 3.97 | 0.58 | ||

| 2. Mindfulness | .48** | –- | 3.87 | 0.87 | |

| 3. Anxiety | -.18 | -.32** | –- | 1.72 | 0.89 |

N = 106. * p < .05, ** p < .01 indicates a significant difference between groups

Results

Smartphone use and course comprehension

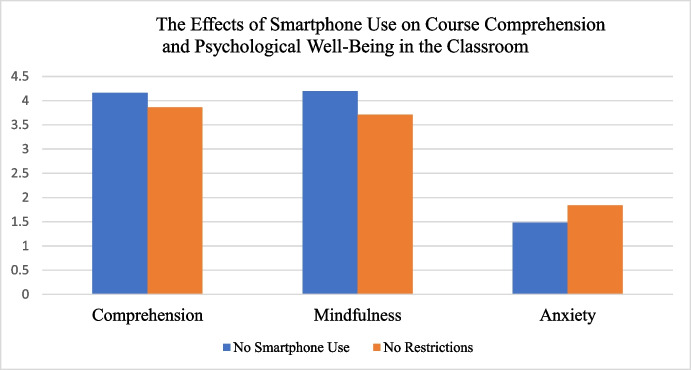

An independent sample t-test examined the effect that smartphone use in the classroom had on overall course comprehension. Results indicated statistically significant differences in course comprehension, t(106) = -2.55, p = 0.01, d = 0.56. The quasi-experimental group had significantly higher levels of course comprehension (M = 4.16, SD = 0.56) than the control group (M = 3.86, SD = 0.56).

Smartphone use and anxiety

An independent sample t-test examined the effect that smartphone use in the classroom had on anxiety during the course. Results indicated statistically significant differences in course anxiety, t(106) = 2.27, p = 0.03, d = 0.88. The experimental group had significantly lower levels of anxiety (M = 1.48, SD = 0.67) than the control group (M = 1.84, SD = 0.97). See Fig. 1 for results.

Fig. 1.

The effects of smartphone use on course comprehension and psychological well-being in the classroom

Smartphone use and mindfulness

An independent sample t-test examined the effect that smartphone use in the classroom had on overall mindfulness during class. Results indicated statistically significant differences in mindfulness, t(106) = -2.84, p = 0.01, d = 0.84. The experimental group had significantly higher levels of mindfulness (M = 4.19, SD = 0.73) than the control group (M = 3.71, SD = 0.89). See Fig. 1 for mean comparisons between study variables.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to explore whether smartphone use impacts course comprehension and the psychological state of students in the classroom. Results found that students who physically removed their smartphones from them throughout the duration of the class had significantly higher levels of comprehension and mindfulness in the course. In addition to that, students without their smartphones had significantly lower levels of anxiety. The data provides preliminary evidence that limiting cell phone use creates a more positive psychological state for students, and in turn, may yield more positive learning outcomes (e.g. Bóo et al., 2020).

The negative association between cell phone use and course comprehension is consistent with previous studies (see e.g. De Shields & Riley, 2019; Kuznekoff & Titsworth, 2013). This finding adds to the growing body of literature that suggests that distracted students perform worse in the classroom. However, previous research has largely been correlational, leaving open the possibility of alternative explanations. The present study provides quasi-experimental evidence that smartphone use has a causal and negative influence on classroom experience. Additionally, the present study adds to the literature that cell phone use increases anxiety in the classroom and reduces mindfulness. This finding is consistent with Lepp et al. (2014), that also identified a negative association between cell phone use and college students’ general level of anxiety. These findings provide preliminary evidence that the presence of cell phones in the class negatively affects student perceptions of their classroom experience.

It should be noted that the results from this study are prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, which may change the nature of psychological well-being in the classroom. Anxiety in the classroom prior to the COVID-19 pandemic focused on school work and grades, whereas post-pandemic may focus on transmission of diseases, vaccinations, and social anxiety due to lack of exposure to social settings. Future studies may investigate psychological well-being of students in the classroom post the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations

The conclusions we can draw are limited by the design of the study and the measures we used. With respect to study design, the participants came from four distinct classes, and different instructors taught each of those classes and the number of participants in each group were not equal. Although each class was a content class in the Behavioral Science Department, future studies may investigate the effects of smartphones in the classroom using the same classes or a single instructor in order to avoid potential confounds. Additionally, our design only examined whether smartphones affect the classroom experience across students. Future studies can include a baseline assessment of the outcomes at the beginning of the semester and again at the end to examine whether smart phones in the classroom have a within-student effect.

The outcomes of the study relied on self-report data from non-validated questionnaires. Self-report data can be biased and future studies should include objective measures of course comprehension (e.g., grade in class) and psychological well-being (e.g., current use of antidepressant drugs). While self-report measures have limitations, the bias associated with these measures were evenly distributed across conditions, therefore the effect of condition cannot be explained by reliance on self-report data. The use of non-validated questionnaires also limits the validity of the results. Future studies can use the items from the present study and items from validity measures to ensure high convergent validity. While many valid and reliable measures of anxiety and mindfulness exist, none perfectly fit the aim of the present study— to examine these constructs confined to the experience in one specific classroom. Thus, questionnaires were created to fit the study design. Only items with face validity were included, and each item was meant to examine the larger construct directly and clearly. Additionally, the high reliability scores suggests that these items were testing a single construct.

Conclusion

The results from our study provide evidence that the use of smartphones in the classroom has a negative effect on levels of course comprehension and the psychological state of students during lecture. Given the psychological state of students is imperative to creating a positive learning environment (Febrilia et al., 2011), it is important that educators make informed decisions about technology use in the classroom, in order to maintain a high-quality learning experience. Something as simple as limiting smartphone use during scheduled class time can have an impact on the well-being of students, and in turn, create a better learning environment.

Biographies

Melissa Huey

is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at New York Tech. She received her master’s in Psychology from City College of New York, and her doctorate in Experimental Psychology from Florida Atlantic University. Her research is focused on the psychological well-being of students in the University classroom.

David Giguere

is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at California State University-Sacramento. He received his doctorate in Experimental Psychology from Florida Atlantic University. His research interests focuses on biligualism and its role in executive function.

Appendix 1 – Course comprehension

1 – Strongly disagree

2 – Disagree

3 – Neutral

4 – Agree

5 – Strongly agree

I am learning a lot in this course.

I feel confident in my knowledge of the course material.

It is clear to me what concepts I do not understand after lecture.

I feel like I can apply the knowledge I learn in this course to new situations.

I have developed new study strategies that have helped me learn the material.

I feel like I can apply what I learn in this course to life outside of school.

I often feel confused after class (reverse-coded).

I feel like I am able to identify points of confusion.

I have been able to learn from my successes and struggles in this course

I feel confident explaining most of the concepts or principles learning in this course to someone else

Appendix 2 – Anxiety

1 – Strongly disagree

2 – Disagree

3 – Neutral

4 – Agree

5 – Strongly agree

During class, I feel nervous, anxious, or on edge.

During class, I am not able to stop or control worrying.

During class, I often worry too much about different things.

During class, I have trouble relaxing.

During class, I am so restless that it’s hard to sit still.

During class, I become easily annoyed or irritable.

During class, I feel worried that something bad will happen.

Appendix 3 – Mindfulness

1 – Strongly disagree

2 – Disagree

3 – Neutral

4 – Agree

5 – Strongly agree

Although I am in class, I am often not paying attention

My mind if rarely focused on what is going on in class.

In class, it seems as I am running on autopilot without much attention to what the professor is saying.

I am often focused on outside responsibilities or tasks during class.

I take notes on autopilot, without truly processing the information.

During class, I find myself preoccupied with the future or the past.

Often in class I am listening, but not fully engaged in the material.

In class, I am often doing other activities.

I find it difficult to pay attention to what’s happening during class.

I often think about class as an opportunity to do other work.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript conception. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Dr. Melissa Huey. The manuscript was prepared by Drs. Melissa Huey and David Giguere. All authors have read an approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics

All procedures performance in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at New York Institute of Technology (IRB Protocol Number: ESB 1520). All participants included in the study were given a consent form prior to participation.

Financial interests

The authors have no financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Melissa Huey, Email: mhuey@nyit.edu.

David Giguere, Email: giguere@csus.edu.

References

- Al-Furaih SA, Al-Awidi HM. Fear of missing out (FoMO) among undergraduate students in relation to attention distraction and learning disengagement in lectures. Education and Information Technologies. 2021;26(2):2355–2373. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10361-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association: National College Assessment. (2022, Spring). Publications and Reports: Retrieved from https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-III_SPRING_2022_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf

- Amez S, Baert S. Smartphone use and academic performance: A literature review. International Journal of Educational Research. 2020;103:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bóo SJ, Childs-Fegredo J, Cooney S, Datta B, Dufour G, Jones PB, Galante J. A follow-up study to a randomised control trial to investigate the perceived impact of mindfulness on academic performance in university students. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2020;20(2):286–301. doi: 10.1002/capr.12282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boumosleh J, Jaalouk D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students - a cross sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero C, Scherer E, West MR, Mrazek MD, Gabrieli CF, Gabrieli JD. Greater mindfulness is associated with better academic achievement in middle school. Mind, Brain, and Education. 2019;13(3):157–166. doi: 10.1111/mbe.12200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen RS, Ji CH. Investigating the relationship between thinking style and personal electronic device use and its implications for academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;52:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Shields S, Riley CW. Examining the correlation between excessive recreational smartphone use and academic performance outcomes. Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice. 2019;19(5):36–47. doi: 10.33423/jhetp.v19i5.2279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci K, Akgönül M, Akpinar A. Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2015;4(2):85–92. doi: 10.1556/2006.4.2015.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febrilia I, Warokka A, Abdullah HH, Indonesia C. University students' emotional state and academic performance: New insights of managing complex cognitive. Journal of e-Learning and Higher Education. 2011;2011:1–15. doi: 10.5171/2011.879553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Irwin JD. In-class distractions: The role of Facebook and the primary learning task. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55:1165–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawi NS, Samaha M. The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Social Science Computer Review. 2017;35(5):576–586. doi: 10.1177/0894439316660340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(2):169–175. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim NK, Baharoon BS, Banjar WF, Jar AA, Ashor RM, Aman AA, Al-Ahmadi JR. Mobile phone addiction and its relationship to sleep quality and academic achievement of medical students at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2018;18(3):Article e00420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junco R, Cotton SR. No A 4 U: The relationship between multitasking and academic performance. Computers & Education. 2012;59(2):505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.12.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L, Lambert W. A happy and engaged class without cell phones? It’s easier than you think. Teaching of Psychology. 2016;43(4):340–345. doi: 10.1177/0098628316662767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Kim R, Kim H, Kim D, Han K, Lee PH, Mark G. Understanding smartphone usage in college classrooms: A long-term measurement study. Computers & Education. 2019;141:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznekoff JH, Titsworth S. The impact of mobile phone usage on student learning. Communication Education. 2013;62(3):233–252. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2013.767917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann, B., Sindermann, C., Sariyska, R. Y., Luo, R., Melchers, M. C., Becker, B., ..., & Montag, C. (2018). The role of empathy and life satisfaction in internet and smartphone use disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 398-403. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lepp A, Barkley JE, Karpinski AC. The relationship between cell phone use and academic performance in a sample of US college students. SAGE Open. 2014;5(1):1–9. doi: 10.1177/2158244015573169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahfouz J, Levitan J, Schussler D, Broderick T, Dvorakova MA, Greenberg M. Ensuring college student success through mindfulness-based classes: Just breathe. College Student Affairs Journal. 2018;36(1):1–16. doi: 10.1353/csj.2018.0000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matar Boumosleh J, Jaalouk D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction university students-A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone L, Ducci F, Scoto MC, Passanti E, D’Arrigo VG, Vitello B. The role of anxiety symptoms in school performance in a community sample of children and adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2021). Mobile fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ on 6th of August, 2021.

- Rashid T, Asghar HM. Technology use, self-directed learning, student engagement and academic performance: Examining the interrelations. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;63:604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sana F, Weston T, Cepeda NJ. Laptop multitasking hinders classroom learning for both users and nearby peers. Computers & Education. 2013;62:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic, M., Nesic, M, Cicevic, S., & Shi, Z. (2021). Association of smartphone use with depression, anxiety, stress, sleep quality, and internet addiction. Empirical evidence from a smartphone application. Personality and Individual Differences, 168. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110342

- Tindell DR, Bohlander RW. The use and abuse of cell phone and text messaging in the classroom: A survey of college students. College Teaching. 2012;60(1):1–9. doi: 10.1080/87567555.2011.604802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim C, Correia A. Exploring the dimensions of nomophobia: Development and validation of a self-reported questionnaire. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;49:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]