Abstract

With a scarcity of research looking at violent and extremist tendencies in primary school children in Pakistan, this study aimed to look at the effects of emotional resilience education through the means of cartoon-based learning. Children have a limited attention span and research on video/cartoon-based literacy projects has indicated greater efficacy with more retention and engagement. The cartoon based on the theme of anti-bullying was used in a 6-week intervention program in an experimental design setup with 120 experimental and 40 control group students recruited from the Islamabad/Rawalpindi area (ages 9–11). The behaviours and awareness about the concepts of physical and verbal bullying, coercion and damaging others’ property, as well as qualitative information about the cartoon themes were assessed before and after the program for pre- and post-test comparison. The cartoon was accompanied with teaching aids, worksheets and activity-based learning. The results indicated that only 3.3% students were aware about bullying and its various types to begin with and after intervention 98.7% understood the concept clearly. Before the intervention, 65.8% students didn’t understand that they were bullies – after the intervention it reduced to 22.5% who thought they were not bullies. Effectiveness of the results from this video literacy program will enable development of more emotional resilience education courses in the curriculum to create a more resilient society in the long run and curb bullying in schools.

Introduction

Using programs and policies to curb violent extremism (VE) has been termed Countering Violent Extremism (CVE). In a much broader context and including pre-emptive approaches before violent tendencies are actualized, the term Preventing Violent Extremism (PVE) is also used. These programs are often institutionalized by national or state infrastructure (Davies, 2018; Stephens et al., 2021). PVE programs and policies are meant to work towards creating an atmosphere in which radicalization is stymied in the upstream or in the ‘breeding ground’ phase (Davies, 2018).

In Pakistan, the social, political, economic and physical infrastructure has been significantly impacted due to terrorism and extremist elements, especially after the events of 9/11 (Nizami et al., 2018). It has the unique problem of both being the frontrunner in the anti-terrorism movement as well as being blamed for sponsoring international terrorism. Therefore, P/CVE programs hold significant importance in the Pakistan region, considering that the war on terror has placed an economic burden of $118 billion in the last 15 years, as per the economic survey of 2015–2016 (Orakzai, 2019). The fear instilled due to terrorism has a psychological impact on the population also, considering the propensity of this region to be exposed to terrorist attacks. In particular, the young and adolescent strata of the society are especially vulnerable as the terrorist attacks have frequently targeted educational institutes (Shah et al., 2018). Paired with the fact that children are already going through accelerated social, physical and psychological changes and are developmentally susceptible, adding extremism and related traumas to the mix makes the situation even more complex. Shaw (2003) has shown that children, when exposed to war-related activities, are expected to have between 10 and 90% of PTSD symptoms, in tandem with other mental health issues which include anxiety, depression, disruptive behaviours as well as physical symptoms. Furthermore, children younger than 12 are three times more likely to develop trauma responses to violent acts, when compared to adolescents and adults (Garbarino et al., 2015). The unfortunate terrorist attack at APS Peshawar in 2014 is a visceral example of how it affected the children’s mental health and traumatized them as a result (Mian, 2016). As described by Mirahmadi (2016), mental illnesses or psychological disturbances are one of the five major push factors towards VE. The vulnerable young population in Pakistan is thus one of the key players in PVE interventions at the national level (Nizami et al., 2018; Orakzai, 2019). It is of utmost significance to support the youth in the strenuous task of finding their identity and developing resilience against VE as individuals, as well as a community in the situation of indigenous extremist beliefs (E. (Lily) Taylor 2018).

With this socio-political and disruptive environment in effect, enhancing the children’s emotional health and psychological wellbeing through educational interventions is posited to be an effective method of developing resilience. One of the approaches towards PVE is enhancing resilience and building cognitive resources in the individual (Aly et al., 2014; Stephens et al., 2021). Education is a suitable option against VE as demonstrated via several targeted programs that bestow opportunities to obtain defensive factors that enhance self-control and resilience in children and young adults (Sebba & Robinson, 2010; Siddiqui et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2017; Theriault et al., 2017). Of note, however, is the paucity of research on the psychological wellbeing of adolescents and school-children in context of terrorism and VE in Pakistan (Shah et al., 2018). In order to deter the involvement of young individuals in extremist groups, education is especially significant (Davies, 2011), and investment in primary education is furthermore emphasized because attitudes and behaviours start to develop at that time (Sas et al., 2020).

As Porche (2016) suggested, emotional intelligence (EI) is one of the prevention strategies to mitigate violence. The implication of EI is that an individual who is good at discerning, understanding, utilizing and managing their own as well as others’ emotions is more likely to be psychosocially adjusted (Mayer et al., 2008). Individuals with higher EI can process events more flexibly due to better regulation capacity and the capability of manoeuvring unfavourable feelings (Zeidner & Matthews, 2018). Moreover, studies have indicated that EI is not an innate quality or inherited, rather it is a skill that is learned and can be increased through training (Alonso-Alberca et al., 2015; Shah et al., 2018) reported that in order to ensure the psychological wellbeing of children and mitigate the fear of terror, counsellors, parents and teachers must contribute towards increasing EI skills. An enhanced EI can lead to lessening of the fear of terrorism through emotional regulation (Shah et al., 2020).

Furthermore, an overall positive relationship has been seen between integrating EI education, as in the case of Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) programs, in pre-adolescent children and their academic performance, their mental well-being and emotional development, social competence and behaviour, as well as better workplace interactions as they grow older (Billings et al., 2014; Osher et al., 2016). In contrast, the inability to regulate emotions is linked not only with inter-personal conflict but with serious disruptive behaviours like aggressive conduct (Lomas et al., 2012). Children with lower emotional competency show violent behaviours with their friends, and their non-involved friends have a better EI skill-set and display more healthy relational dynamics (Elipe et al., 2015).

An important part of cultivating good emotional and social health in children, is to regulate negative or aggressive behaviour - often seen in the form of bullying. Aggression or violent behaviour has a strong influence on the psychosocial adjustment and mental health of both the perpetrators and the victims of it. EI has been shown to affect aggressive behaviour, with a general association of children having a higher EI engaging in lesser aggressive behaviours (physical and verbal) towards their peers. More specifically, when looking at aggression towards particular classmates, which manifests itself as bullying, there has been a negative association observed between emotional competency and bullying tendencies (García-Sancho et al., 2014). More importantly, school bullying (both perpetration and victimization) has been shown to have association with violent behaviour in later life (Ttofi et al., 2012). There is also evidence that young adults that are involved in mass school shootings have a precedent of having been bullied (Peterson Jr, 2015).

By definition, bullying is illustrated as recurrent aggressive behaviour by a perpetrator towards a weaker (physically and psychologically) peer. Bullying in school is especially concerning for not only the victims, but also the teachers, families, psychologists/school counsellors and the relevant health authorities (Gini, 2008). Bullying can be classified as such: a child can either exclusively be a bully, a victim, a bully-victim (both affected by a bully and bullies other children), a bystander (neither a victim nor perpetrator of bullying) (Glew et al., 2005). According to Glew et al. (2005) elementary school-children who are distressed psychologically are likely to be involved with bullying behaviour in some form, and also that children with academic struggles are predisposed to be bully-victims and being victimized by bullies. Early-age risk factors for the perpetration of bullying behaviour in school-children can include insufficient cognitive stimulation at home and emotional support at home (Zimmerman et al., 2005).

Bullying in children can be direct or indirect, and often assumes the characteristic of a group process whereby children take on varying roles, previously categorized as victim, bully, bystander etc. Direct bullying could be physical aggression like hitting, or verbal attacks like name-calling or insulting. Indirect bullying is more covertly accomplished by spreading rumours, denying friendships or creating cliques with the victims being excluded. Research has also demonstrated that generally boys bully more than girls. This has been corroborated in several studies, including those in the Pakistani population (Fleming & Jacobsen, 2010; Karmaliani et al., 2017), but it appears that with increasing age, the balance shifts (Dytham, 2018; Fleming & Jacobsen, 2010). Some other studies have also been conducted in the Pakistani population to establish baseline bullying and aggression behaviour in children and adolescents in specific locations (Fariha & Najam, 2015; Khawar & Malik, 2016). How children assume different roles in the bullying paradigm, and how aggressive they are, is related to their social-emotional skills which include their trait emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and empathy (Kokkinos & Kipritsi, 2012).

School intervention programs to counter aggression and bullying behaviour, including cyber-bullying, have been studied for their effectiveness. Cantone et al. (2015) reported that these intervention programs do have a significant short-term effect on bullying behaviour when controlling for gender, age and socio-economic strata differences. A study by Pérez-Fuentes et al. (2019) studied the relationship between family functioning, EI (stress management) and personal values development - and how the higher these factors scored in a group of high school students, the more non-aggressive they were. A meta-analysis review by Gaffney et al. (2019) demonstrates the effectiveness of school anti-bullying intervention programs, with significant reduction in bullying perpetration by about 19–20%, and bullying victimization by 15–16% approximately.

Prior research indicates that educational programs that utilize multimedia, videos, animations and cartoons are an effective tool to enhance learning (Beheshti et al., 2018; Eker & Karadeniz, 2014; Shreesha & Tyagi, 2016; Taher & Soltani, 2011; Willmot et al., 2012). Students retain information much more effectively when visual learning is the means of instruction (Mayer & Gallini, 1990). This is because multimedia approaches engage both the auditory and visual channels when retaining information for the working memory cognitive load, rather than just one channel used in traditional learning. Maximum student engagement is achieved by making brief videos to minimize mind-wandering, having an accessible dialogue-driven language, enthusiastic tones in the audio and segmented content so that it is relevant and understandable (Brame, 2016). In the context of children, cartoon-based education is an effective source of audio-visual education (Habib & Soliman, 2015). It avoids the pitfalls of traditional classroom learning being monotonous and reduces stress, anxiety and disruptive behaviour in the class (Taher & Soltani, 2011).

With the theoretical knowledge of disruptive childhood emotional health as the consequence of terrorism and VE, and the success of effective educational programs to develop resilience as PVE interventions, the current study undertook a video literacy program to enhance EI in primary school children. The primary research objectives of the study were to:

Conduct a pilot program of using anti-bullying themed animated cartoon (8–10 min long) in order to reduce bullying and aggressive behaviour as a PVE measure, in a sample population of Pakistani primary schools in the Islamabad/Rawalpindi region.

Study the behavioural impact and effectiveness of the program by using parameters from previously established research designs and measurement scale for bullying and victimization, in a pre- and post-test quantitative, as well as qualitative assessment, of students, teachers and parents.

Initiate establishing video-literacy curriculum in primary schools in order to mediate further EI education in the future, after studying the effectiveness of the current intervention.

Methodology

Study Design

Keeping in mind the nature of the study, a quantitative experimental design approach was used for the pre- and post-survey test, however for some qualitative interviews, a multi-method approach was utilized making it a quasi-experimental study design. The qualitative interviews were taken from students, teachers and parents as well to learn more about the subjective changes in behaviour during the intervention. Since the animated cartoons called for daily screening and discussions, the researchers’ observed the student answers to cartoon-related questions to assess their understanding of bullying, as it changed during the course of the intervention.

Selection criteria

A formal agreement was signed with complete transparency of all the research design protocol, with the two (one private and one public) partnering schools in the Islamabad/Rawalpindi region of Pakistan. The schools were selected if (i) they had 80 or more primary school students in order to form 2 required groups for the experimental design, (ii) they permitted the research team to access every gatekeeper (parents, guardians) and take formal consent from children, (iii) they were holding classes online and let the research team observe the students in order to get qualitative data, and (iv) their teachers were willing to be trained to collect worksheet-related qualitative data and share their observations during the intervention period. The parents and students who did not want to partake in the study were excluded. Similarly, if the participating subjects (parents or students) could not join in the video-interventions, and if they had some underlying psychological issues, or were going through a psychological treatment prior to the program, they were also excluded from the final study.

Ethical considerations

Written consent forms were taken from all the participating subjects (children, parents/guardians, teachers) prior to the start of the study. All protocols pertaining to the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. The partnering school’s administrative departments also gave prior ethical approval. All information was kept confidential and only used for the purpose of research. To maintain anonymity, each student was assigned a code for data processing. At the start, to avoid profiling or selection biases, all students were included in the respective grades. Once the approved consent forms were processed, then the students who had consented were included in the final study. Researcher-based bias was avoided by making sure that at least 2 researchers as well as an assigned teacher was always present for daily observation. Therefore, if there was any difference in the daily observations, they were discussed before landing onto the final data. To make sure that the students were not influenced by the researchers being present, they acclimated with the students during the consent-taking to acquaint themselves.

Sample selection

Our final study sample (N = 160), from the two schools was selected after getting ethical approval from school administration, parents, teachers and children. The students were divided into two groups; Experimental (N = 120), and Control (N = 40) (Table 1). Keeping in mind COVID-19 regulations for both institutions, a hybrid one-week on-campus and one-week online model was used for one batch (no difference in treatment, only alternating the batch between online and in-person sessions), while the second batch remained totally online except for one day per week. There was no difference in treatment for the two batches, just that their mode of instruction was dependent on school policy (online or in-person). Both batches make up the total experimental group. The control group of course underwent no intervention. We selected the student’s class-range on the teacher’s recommendations (grade 4 to 5; Table 2).

Table 1.

Number of students in each group (Experimental and Control)

| Groups | Total Students (N = 160) | Male Students (N = 74) | Female Students (N = 86) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | 120 | 59 | 61 |

| Control | 40 | 15 | 25 |

Table 2.

Demographic Information of Both Groups (Experimental and Control)

| Demographic Information | Experimental Group | Control Group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Students | 120 | 40 | |

| Age | 9 years | 19 | 07 |

| 10 years | 80 | 24 | |

| 11 years | 19 | 07 | |

| 12 years | 02 | 02 | |

Experimental design

Both experimental and control group students were assigned by the teachers in separate sections, and a pre-survey questionnaire was administered. The researchers were present during the pre-test phases to acquaint themselves with the students. In the case of the experimental group, a repeated measures intervention was carried out in which the students were subjected daily to the cartoon video for the duration of the study, and then evaluated again at the end with the post-test questionnaire. The control group did not undergo any intervention but did give the pre- and post-test assessment. The phases of the experiment are outlined below:

Pre-test evaluation (scale discussed in Measurement Scale section), of both experimental and control group. Qualitative interviews also taken from teachers (N = 4) and parents/guardians to establish baseline behaviours of students in terms of violent or aggressive behaviour.

Intervention (Daily animated cartoon screening accompanied with related activities spread though out the duration of the program to keep the students motivated and engaged like workbooks, stickers, finger puppets, stick figures of the cartoon characters etc.). Administered for 6 weeks in total, with different activity related to cartoon on each weekday. In order to model behaviour change, the cartoon was repeated 3–5 times a week for repetition effect. Researchers and teachers recorded daily observations. Control group did not receive any intervention.

Post-test evaluation and interviews from both groups, as well as the parents and teachers.

Data processing and analysis.

Intervention design

A group of animators was taken on board beforehand under a non-disclosure agreement to keep the animated cartoons unavailable for public viewing. To develop the bullying and victimization storyline for the cartoon, and keeping in view the 360° effect based on research, a subject matter expert panel was recruited which included clinical psychologists, neuroscientists and EI researchers. Final storylines were vetted by senior Professor of Clinical Psychology with years of professional experience in play therapy. Animators were provided the final approved storylines, for the development of the cartoon, which was then again validated for its contents by the expert panel.

The final cartoons were shown to the experimental group during the intervention phase, and the screening was controlled by the researcher so that access was restricted from all others including parents. Parents were just asked to report on the child’s behaviour, without any biases about the contents of the cartoon, which they were not privy to.

Statistical analysis

Due to the longitudinal nature of the study with pre- and post-test measures, McNemar’s Test for Paired Samples Proportions and Frequency Analyses were done for the quantitative data using SPSS. The thematic analyses from the interviews and qualitative data collected from the intervention-adjacent activities was analysed using NVivo.

Measurement scale

To assess the children’s pre- and post-test awareness of bullying and victimization, and violent tendencies, the revised Olweus Bullying Victimization Questionnaire was used (Olweus, 1993, 1996), without translation as the study cohort was familiar with that level of English comprehension. The scale has been previously validated (Khawar & Malik, 2016; Kyriakides et al., 2006; Solberg & Olweus, 2003). The scale was selected based on its multi-faceted approach towards determining types and levels of bullying, victimization and the bystander effect. The bullying categorization was done according to the scheme followed by Rana et al. (2020).

Results

Quantitative

In order to test the student’s tendencies towards violent and bullying behaviour in their age-group, we administered an array of questions to have a measure of how their behaviour and peer-level bullying and victimization scores change during the course of the intervention. We also assessed the bullying and victimization tendencies in the control group to see if there are any noticeable changes when compared to the students in the experimental group who underwent an intervention focused on the theme of anti-bullying.

At the baseline, we first measured the student’s tendency to be a victim of bullying, and how often they are a bully to others. The majority (46.7%) of the students indicated they were not victims of bullying in the pre-test evaluation, however, the percentage dropped to 42.5% in the post-test, whereby the majority of the responses indicated they have been bullied between once or twice or even 2–3 times in a single month. The frequency of students that reported being victims of bullying by others during the pre-test increased a little bit after the intervention, however the difference was not statistically significant, as the McNemar test showed that the proportions of victims before and after the intervention were the same (N = 120, χ2 = 0.246, p = .620). Similarly, the bullying frequencies in the pre- and post-test evaluation determined how often and how much the students showed perpetration behaviour towards their peers in their interactions. During the pre-test the largest majority overall (65.8%) said that they haven’t ever been bullies to others in the recent past. However, when asked after the intervention period, the frequency of non-bullying answers dropped to 22.5% (N = 120, χ2 = 37.157, p = .000). Table 3 shows the victimization and bullying others’ frequencies in the Experimental group.

Table 3.

Comparison of Victimization and Bullying Frequencies in the Pre- and Post-Test Evaluation in the Experimental Group (N = 120)

| Extent of Victimization | Pre-Test | Post-Test | McNemar’s χ2 (N, p)* | ||

|

Frequency (%) M (n = 59), F (n = 61) |

Victim/Non-Victim Categorization | Frequency (%) M (n = 59), F (n = 61) | Victim/Non-Victim Categorization | ||

| I haven’t been a victim of bullying in the past couple of months |

56 (46.7) M (n = 31) F (n = 25) |

Non-Victim Frequency (%) = 56 (46.7) |

51 (42.5) M (n = 27) F (n = 24) |

Non-Victim Frequency (%) = 51 (42.5) | 0.246 (120, 0.620) |

| It has only happened once or twice |

24 (20.0) M (n = 10) F (n = 14) |

Victim Frequency (%) = 64 (53.3) |

23 (19.2) M (n = 6) F (n = 17) |

Victim Frequency (%) = 69 (57.5) | |

| 2 or 3 times a month |

21 (17.5) M (n = 8) F (n = 13) |

20 (16.7) M (n = 11) F (n = 9) |

|||

| About once a week |

14 (11.7) M (n = 7) F (n = 7) |

18 (15.0) M (n = 10) F (n = 8) |

|||

| Several times a week |

5 (4.2) M (n = 3) F (n = 2) |

8 (6.7) M (n = 5) F (n = 3) |

|||

| Total: | 120 (100) | 120 (100) | |||

| Extent of Bullying Others | Pre-Test | Post-Test | McNemar’s χ 2 (N, p)** | ||

|

Frequency (%) M (n = 59), F (n = 61) |

Bully/Non-Bully Categorization | Frequency (%) M (n = 59), F (n = 61) | Bully/Non-Bully Categorization | ||

| I haven’t bullied another student(s) at school in the past couple of months |

79 (65.8) M (n = 42) F (n = 37) |

Non-Bully Frequency (%) = 79 (65.8) |

27 (22.5) M (n = 16) F (n = 11) |

Non-Bully Frequency (%) = 27 (22.5) | 37.157 (120, 0.000) |

| It has only happened once or twice |

7 (5.8) M (n = 4) F (n = 3) |

Bully Frequency (%) = 41 (34.2) |

30 (25.0) M (n = 13) F (n = 17) |

Bully Frequency (%) = 93 (77.5) | |

| 2 or 3 times a month |

19 (15.8) M (n = 11) F (n = 8) |

31 (25.8) M (n = 15) F (n = 16) |

|||

| About once a week |

13 (10.8) M (n = 2) F (n = 11) |

20 (16.7) M (n = 8) F (n = 12) |

|||

| Several times a week |

2 (1.6) M (n = 0) F (n = 2) |

12 (10) M (n = 7) F (n = 5) |

|||

| Total: | 120 (100) | 120 (100) | |||

* McNemar’s Test for Difference in Proportions of Non-Victims & Victims in Pre- and Post-Test

** McNemar’s Test for Difference in Proportions of Non-Bullies & Bullies in Pre- and Post-Test

In the control group, the frequency of students that reported being victim of bullying by others in the pre-test surprisingly increased , as the McNemar test with binomial distribution showed that the proportions of victims before and after the intervention were statistically different (N = 40, p = .000) This is an interesting phenomena and may point towards the general awareness spread through friends that were in experimental group and were discussing the learning from the anti-bullying programs with their peers. However, students reporting that they have bullied others did not change significantly in the post-test as the McNemar test with binomial distribution showed that the proportions of bullies before and after the intervention were the same (N = 40, p = .052). Table 4 shows the victimization and bullying others’ frequencies in the Control group.

Table 4.

Comparison of Victimization and Bullying Frequencies in the Pre- and Post-Test Evaluation in the Control Group (N = 40)

| Extent of Victimization | Pre-Test | Post-Test | McNemar’s binomial distribution = N, p* | ||

| Frequency (%) | Victim/Non-Victim Categorization | Frequency (%) | Victim/Non-Victim Categorization | ||

| I haven’t been a victim of bullying in the past couple of months | 24 (60) | Non-Victim Frequency (%) = 24 (60) | 3 (7.5) | Non-Victim Frequency (%) = 3 (7.5) | 40, 0.000 |

| It has only happened once or twice | 5 (12.5) | Victim Frequency (%) = 16 (40) | 17 (42.5) | Victim Frequency (%) = 37 (92.5) | |

| 2 or 3 times a month | 5 (12.5) | 16 (40.0) | |||

| About once a week | 4 (10.0) | 2 (5.0) | |||

| Several times a week | 2 (5.0) | 2 (5.0) | |||

| Total: | 40 (100) | 40 (100) | |||

| Extent of Bullying Others | Pre-Test | Post-Test | McNemar’s binomial distribution = N, p** | ||

| Frequency (%) | Bully/Non-Bully Categorization | Frequency (%) | Bully/Non-Bully Categorization | ||

| I haven’t bullied another student(s) at school in the past couple of months | 16 (40) | Non-Bully Frequency (%) = 16 (40) | 26 (65.0) | Non-Bully Frequency (%) = 26 (65.0) | 40, 0.052 |

| It has only happened once or twice | 11 (27.5) | Bully Frequency (%) = 24 (40) | 1 (2.5) | Bully Frequency (%) = 14 (35.0) | |

| 2 or 3 times a month | 7 (17.5) | 7 (17.5) | |||

| About once a week | 4 (10.0) | 6 (15.0) | |||

| Several times a week | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Total: | 40 (100) | 40 (100) | |||

* McNemar’s Test with Binomial Distribution for Difference in Proportions of Non-Victims & Victims in Pre- and Post-Test

** McNemar’s Test with Binomial Distribution for Difference in Proportions of Non-Bullies & Bullies in Pre- and Post-Test

We also asked the students about specific types of bullying and aggressive behaviour, and whether they were victims of it, or the initiators. Table 5 shows the statements highlighting certain types of bullying behaviours, and the student’s responses to those statements in the experimental group (N = 120), while Table 6 shows how frequently the experimental group student initiated these behaviours themselves. Overall, there was not a statistically significant difference in their responses, but they did answer more openly in the post-test evaluation (all p > .05, McNemar’s χ2 Test for difference in proportions of victim/non-victim and bully/non-bully in pre- and post-test used, data not shown).

Table 5.

Pre- and Post-Test responses of the experimental group about different types of bullying and extremist behaviours, as victims of it. Frequencies of male and female responses are indicated

| Victimization Behaviours | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Pre-Test Responses | Post-Test Responses | ||||||||

| 1 (%), (N) | 2 (%), (N) | 3 (%), (N) | 4 (%), (N) | 5 (%), (N) | 1 (%), (N) | 2 (%), (N) | 3 (%), (N) | 4 (%), (N) | 5 (%), (N) | |

| Verbal Bullying: I was called mean names, was made fun of, or teased in a hurtful way |

52.5 M (n = 28), F (n = 35) |

24.2 M (n = 19), F (n = 10) |

13.3 M (n = 5), F (n = 11) |

5.8 M (n = 3), F (n = 4) |

4.2 M (n = 4), F (n = 1) |

56.7 M (n = 31), F (n = 37) |

18.3 M (n = 13), F (n = 9) |

16.7 M (n = 9), F (n = 11) |

5.0 M (n = 6), F (n = 0) |

3.3 M (n = 0), F (n = 4) |

| Physical Bullying: I was hit, kicked, pushed, shoved around or locked indoors |

61.7 M (n = 37), F (n = 37) |

27.5 M (n = 15), F (n = 18) |

3.3 M (n = 2), F (n = 2) |

2.5 M (n = 2), F (n = 1) |

5.0 M (n = 3), F (n = 3) |

57.5 M (n = 29), F (n = 40) |

31.7 M (n = 24), F (n = 14) |

5.0 M (n = 4), F (n = 2) |

2.5 M (n = 1), F (n = 2) |

3.3 M (n = 1), F (n = 3) |

| Damage to Belongings: I had money or other things taken away from me or damaged |

50.0 M (n = 29), F (n = 31) |

24.2 M (n = 11), F (n = 18) |

9.2 M (n = 6), F (n = 5) |

6.7 M (n = 5), F (n = 3) |

10.0 M (n = 8), F (n = 4) |

59.2 M (n = 33), F (n = 38) |

21.7 M (n = 15), F (n = 11) |

11.7 M (n = 8), F (n = 6) |

4.2 M (n = 1), F (n = 4) |

3.3 M (n = 2), F (n = 2) |

| Coercion: I was threatened or forced to do things I didn’t want to do |

71.7 M (n = 39), F (n = 47) |

15.0 M (n = 12), F (n = 6) |

8.3 M (n = 5), F (n = 5) |

2.5 M (n = 2), F (n = 1) |

2.5 M (n = 1), F (n = 2) |

74.2 M (n = 42), F (n = 47) |

18.3 M (n = 12), F (n = 10) |

4.2 M (n = 3), F (n = 2) |

1.7 M (n = 1), F (n = 1) |

1.7 M (n = 1), F (n = 1) |

| Racial/Colour-based bullying: I was bullied with mean names or comments about my race or colour (where I am from, how I look) |

61.7 M (n = 36), F (n = 38) |

16.7 M (n = 9), F (n = 11) |

14.2 M (n = 9), F (n = 8) |

5.0 M (n = 4), F (n = 2) |

2.5 M (n = 1), F (n = 2) |

61.7 M (n = 28), F (n = 46) |

20.8 M (n = 20), F (n = 5) |

14.2 M (n = 9), F (n = 8) |

3.3 M (n = 2), F (n = 2) |

0 |

| Harassment: I was bullied with mean names, comments, or gestures with a sexual/ inappropriate meaning |

70.0 M (n = 44), F (n = 40) |

15.8 M (n = 5), F (n = 14) |

6.7 M (n = 4), F (n = 4) |

5.8 M (n = 4), F (n = 3) |

1.7 M (n = 2), F (n = 0) |

65.0 M (n = 36), F (n = 42) |

18.3 M (n = 15), F (n = 7) |

6.7 M (n = 5), F (n = 3) |

5.8 M (n = 1), F (n = 6) |

4.2 M (n = 2), F (n = 3) |

Table 6.

Pre- and Post-Test responses of the experimental group about different types of bullying and extremist behaviours, as initiators of it. Frequencies of male and female responses are indicated

| Bullying Behaviours | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Pre-Test Responses | Post-Test Responses | ||||||||

| 1 (%), (N) | 2 (%), (N) | 3 (%), (N) | 4 (%), (N) | 5 (%), (N) | 1 (%), (N) | 2 (%), (N) | 3 (%), (N) | 4 (%), (N) | 5 (%), (N) | |

| Verbal Bullying: I called another student(s) mean names, made fun of them, or teased them in a hurtful way |

57.5 M (n = 32), F (n = 37) |

21.7 M (n = 12), F (n = 14) |

11.7 M (n = 8), F (n = 6) |

6.7 M (n = 5), F (n = 3) |

2.5 M (n = 2), F (n = 1) |

69.2 M (n = 37), F (n = 46) |

20.8 M (n = 16), F (n = 9) |

7.5 M (n = 5), F (n = 4) |

1.7 M (n = 1), F (n = 1) |

0.8 M (n = 0), F (n = 1) |

| Physical Bullying: I hit, kicked, pushed, shoved around or locked them indoors |

77.5 M (n = 45), F (n = 48) |

9.2 M (n = 3), F (n = 8) |

10.0 M (n = 8), F (n = 4) |

2.5 M (n = 2), F (n = 1) |

0.8 M (n = 1), F (n = 0) |

79.2 M (n = 45), F (n = 50) |

5.8 M (n = 4), F (n = 3) |

9.2 M (n = 6), F (n = 5) |

1.7 M (n = 1), F (n = 1) |

4.2 M (n = 3), F (n = 2) |

| Damage to Belongings: I took money or other things away from them or damaged their belongings |

73.3 M (n = 43), F (n = 45) |

10.0 M (n = 5), F (n = 7) |

5.8 M (n = 6), F (n = 1) |

7.5 M (n = 4), F (n = 5) |

3.3 M (n = 1), F (n = 3) |

75.8 M (n = 46), F (n = 45) |

12.5 M (n = 6), F (n = 9) |

2.5 M (n = 1), F (n = 2) |

5.8 M (n = 3), F (n = 4) |

3.3 M (n = 3), F (n = 1) |

| Coercion: I threatened or forced them to do things they didn’t want to do |

75.8 M (n = 44), F (n = 47) |

10.0 M (n = 5), F (n = 7) |

5.0 M (n = 3), F (n = 3) |

7.5 M (n = 5), F (n = 4) |

1.7 M (n = 2), F (n = 0) |

75.0 M (n = 42), F (n = 48) |

14.2 M (n = 8), F (n = 9) |

4.2 M (n = 3), F (n = 2) |

5.0 M (n = 4), F (n = 2) |

1.6 M (n = 2), F (n = 0) |

| Racial/Colour-based bullying: I bullied them with mean names or comments about their race or colour (where they’re from, how they look) |

73.3 M (n = 42), F (n = 46) |

11.7 M (n = 8), F (n = 6) |

4.2 M (n = 3), F (n = 2) |

9.2 M (n = 5), F (n = 6) |

1.7 M (n = 1), F (n = 1) |

73.3 M (n = 43), F (n = 45) |

14.2 M (n = 8), F (n = 9) |

5.0 M (n = 4), F (n = 2) |

5.8 M (n = 4), F (n = 3) |

1.7 M (n = 0), F (n = 2) |

| Harassment: I bullied them with mean names, comments, or gestures with a sexual/ inappropriate meaning |

70.8 M (n = 41), F (n = 44) |

11.7 M (n = 6), F (n = 8) |

5.0 M (n = 4), F (n = 2) |

9.2 M (n = 7), F (n = 4) |

3.3 M (n = 1), F (n = 3) |

82.5 M (n = 46), F (n = 53) |

10.8 M (n = 9), F (n = 4) |

0.8 M (n = 0), F (n = 1) |

5.8 M (n = 4), F (n = 3) |

0 |

The victimization and bullying tendencies of the Control Group students (N = 40) demonstrated no variation in their responses either (all p > .05, McNemar’s test with binomial distribution used).,

1: It hasn’t happened to me in the past couple of months, 2: only once or twice, 3: 2 or 3 times a month, 4: about once a week, 5: several times a week.

1: It hasn’t happened to me in the past couple of months, 2: only once or twice, 3: 2 or 3 times a month, 4: about once a week, 5: several times a week.

The experimental group student’s responses with regards to the bystander effect were also assessed. We asked them about other student’s stepping in to take action when a person is being bullied. During the pre-test, 75.8% (46 males, 45 females) of the students indicated that other students almost never step in to take action, while 13.3% (5 males, 11 females) said they help once in a while, 4.2% (4 males, 1 female) indicated that other students step in sometimes and similarly, 4.2% (3 males, 2 females) said they help often, and 2.5% (1 male, 2 females) indicated that other students almost always help. When asked again after the intervention, the student’s responded with 80.0% (45 males, 51 females) saying that other student almost never help, 13.3% (10 males, 6 females) still said that other students help once in a while, 3.3% (2 males, 2 females) indicated help is available sometimes, while only 1.7% (1 male, 1 female) of the responses indicated that other students often help out a person being bullied, or almost always help (also 1.7%, 1 male, 1 female).

Qualitative

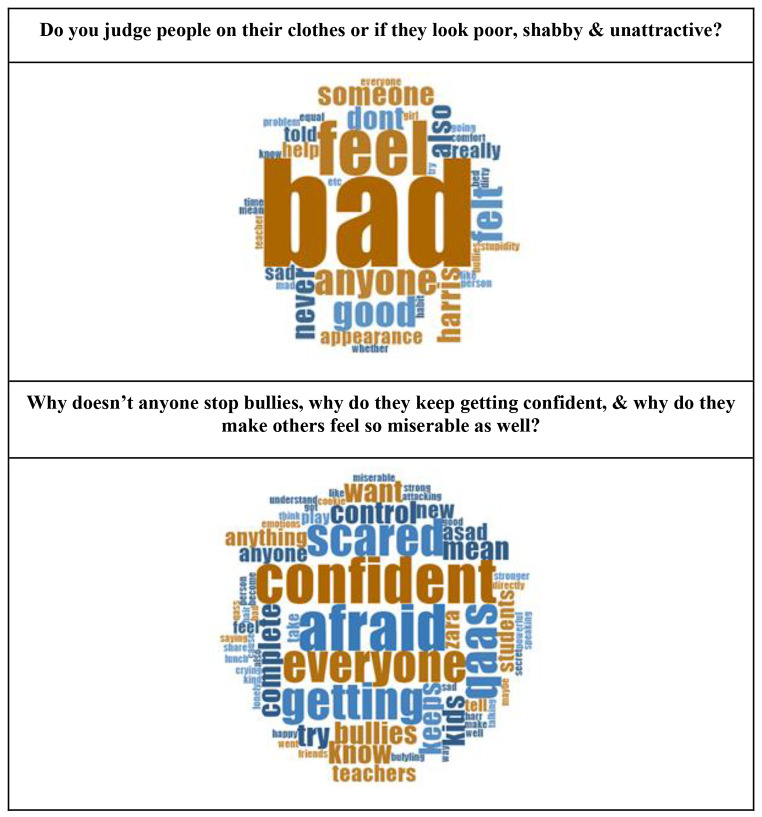

As a baseline qualitative question, we asked the experimental group students if they were aware of what bullying was (Do you know what bullying is?). During the pre-test, only 3.3% of the students indicated that they were aware of bullying, however during the post-test 98.3% replied in the affirmative. To enhance and reinforce the student’s concepts about our intervention paradigms, we also administered activities related to the cartoon’s storylines. One of them was making the student do exercises that allowed them to apply the knowledge they were gaining from the cartoons. We collected qualitative responses from the student this way, which gave an insight into the student’s increasing knowledge about our central themes. Over the 6-week program, we gave the student a multitude of exercises, out of which we selected some to analyse to assess how well the students have understood the central themes of the cartoons and our program. Some of the responses to selected questions are represented here as word clouds in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Experimental Group students’ qualitative responses to questions related to the cartoon themes

As the 6-week intervention progressed, the students became increasingly engaged and started narrating personal examples of bullying, as they saw it portrayed in the cartoon as well. A student observed about their first day of school, “A girl pushed me on my first day. And I didn’t want to have lunch but was forced to do so. The teacher forced me to have lunch.” This led to a discussion about the difference between bullying and being mean, and what it means to take orders from elders. Another student commented “My cousin called me fat. I felt bad.” Similar moral reasoning prompts encouraged the students to critically analyse these situations. When asked about why bullies keep repeating their behaviour (Fig. 1), a student commented, “Because no one stops them that’s why they become confident.” On a discussion about bullies’ motivation, a student said “They think when they bully and control others, the others will listen”. Other students gave much nuanced answers, “Sometimes bullies bully because they are unhappy” and “When a person is alone, they are powerless - can resort to bullying to overcome the loneliness”. Another important observation at the end of the intervention was that students now understood the concept of bullying and were calling out their bullies and reporting them to their peers, parents and teachers as well. When asked about the types of bullying towards the end of the intervention, the students gave several examples such as: “to hurt someone, push someone, hit someone, to take someone’s possessions, take someone’s lunch, to tease someone, call someone with a bad name, to scold someone”. This demonstrates the student’s understanding of different types of bullying including verbal, physical and emotional bullying. When asked to summarize the core concept of the cartoon, some notable responses included, “It’s nothing to be ashamed of or be afraid of to tell someone is bullying us”, “If we see someone being bullied, we should tell someone. Don’t bully ourselves, be kind and understand someone’s feelings” and “We should not insult or bully others. We should stand for ourselves, respect others and make others respect us as well.”

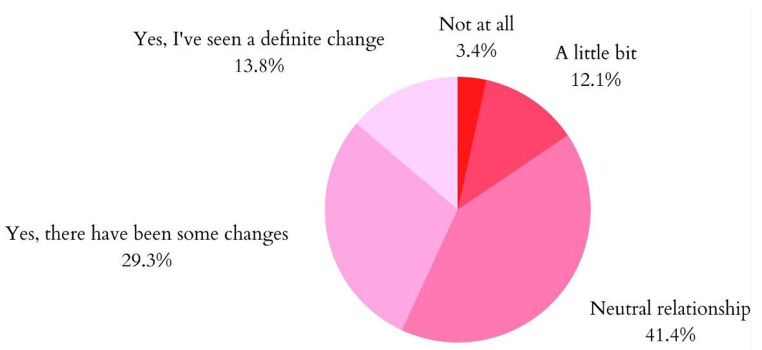

Parents’ qualitative responses

Aside from measuring the children’s responses to questions regarding bullying and victimization, the parents of the children were also assessed in the pre-test and post-test phase. The parents were asked qualitative questions regarding their opinion about their children learning about EI themes like these using the cartoons and video literacy curriculum. We analysed their pre- and post-test responses to the questions to deduce the main themes and recurring answers. Before the intervention, 63% of the parents denied having discussed topics like emotional resilience and bullying at home before. However, after the intervention the percentage dropped to 28%. After the study, we asked the parents “Have you observed any positive changes in your child’s behaviour during and after the activity?” Figure 2 shows their responses, indicating that although the majority did not observe any notable change, there was a shift towards more awareness and understanding as 29.3% indicated that there have been some changes in behaviour. Considering the future impact of this study, we also asked the parents “Do you want to continue this activity for your child in the future with even more themes like anger, anxiety, stress etc.”, to gauge their response on the success of this pilot program. An overwhelming majority of 98% responded in the affirmative.

Fig. 2.

Parent’s post-test response to the question, “Have you observed any positive changes in your child’s behaviour during and after the activity?”

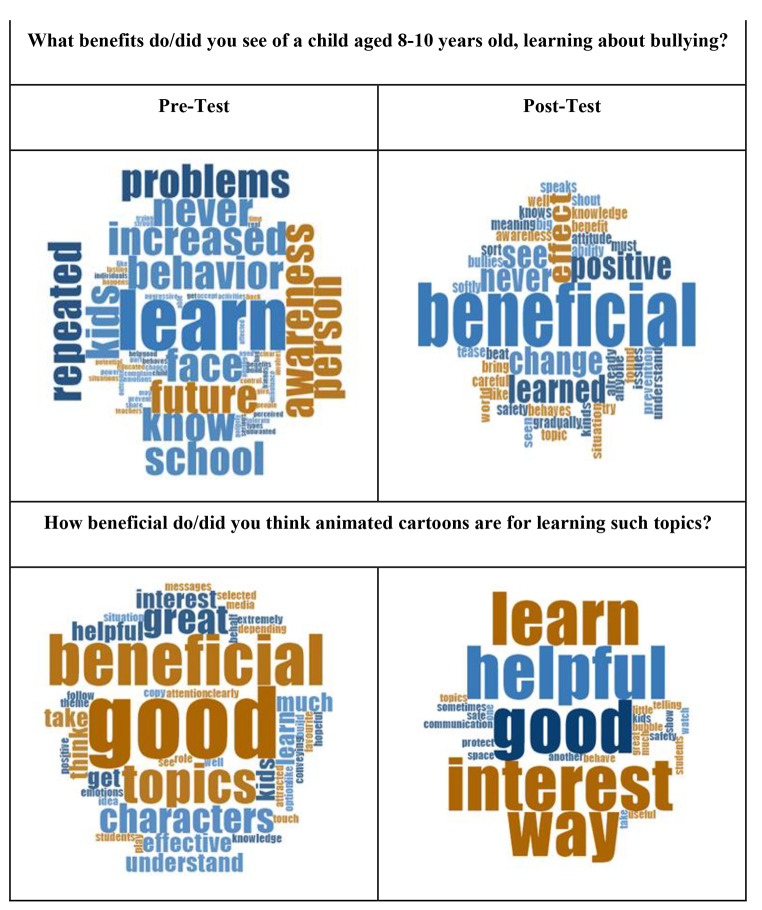

Figure 3 shows the word cloud responses generated from the pre- and post-test responses collected from the children’s parents. One parent commented about the usefulness of learning about bullying, “Children will be able to face such types of situations in the future.” While another parent pointed out that this will give the children more freedom and the right vocabulary to discuss such problem with them, saying “It is good to learn about bullying, so that they can share problems with me about their friends or herself.”

Fig. 3.

Parent’s Word Cloud responses to selected questions in the pre- and post-test evaluation

Teachers’ qualitative responses

Figure 4 shows the frequency of the responses provided by the teachers (data was collected from 4 teachers who were part of the study and supervised the students during their intervention, and assisted in noting daily observations). They indicated whether the student did not improve, moderately improved or improved much after the intervention, when compared to the start of the study. The majority of the students (67.5%) improved much after the intervention according to the teachers.

Fig. 4.

Teacher’s Response Decisions about the experimental group students (N = 120) as they underwent the video literacy intervention program

During the pre-test, the teachers observed that the students were less expressive, less energetic, less active and distracted, shy and unresponsive. These findings and other recurring observations about the student are illustrated in the word cloud in Fig. 5. Other responses like sensitive, bullying, talkative etc. were less observed.

Fig. 5.

Word cloud of teacher’s qualitative responses about the students during the pre-test

The teachers expressed that the students improved after the intervention, as noted during their post-test observations. The majority of post-test responses by teachers included terms like feelings, behaviour, active, change, confident, kind, good behaviour, and sensitive. Responses of bad behaviour, resistant, bullying, inactive etc. were less observed after the intervention. Figure 6 shows the word cloud representing the recurring themes and words used by the teachers to note their observations about the students post-intervention.

Fig. 6.

Word cloud of teacher’s qualitative responses about the students during the post-test

Discussion & conclusion

The results and observations gathered from this experimental design study were very interesting and gave insight for the future of emotional awareness video literacy programs in this region. As Fig. 3 suggests, the parents have indicated that not enough talks are conducted neither at school nor at home on the sensitive topics of developing emotional awareness to know what is bullying and when a child is being victimized. Aside from this, through researcher observations, the children were also very enthusiastic in participating in such an intervention as they hadn’t experienced learning these type of concepts in such detail before. The researchers observed a notable difference in the perception of bullying and understanding of the victimization and perpetration of related behaviours, in the experimental group. In as little as 6 weeks of intervention with a research-based cartoon program, the observations and anecdotal evidence was quite fascinating. 3 out of the 6 weeks were conducted online in order to comply with school and government COVID protocols. After the intervention, the teachers and researchers unanimously observed that the students were more responsive, open and receptive to discussion about the learning concepts in face-to-face discussions. This warrants that if continued in the future, even more differences in behavioural modifications can be observed if the whole study is done in-person without obstacles due to the hybrid mode of learning, provided the health and safety protocols allow it.

Interestingly, this also highlights a key aspect of using video/cartoon medium to enhance learning. As observed in Fig. 3, this type of learning is a valuable and interesting way of imparting such education, according to the parents. But utilizing only cartoons is not enough in this scenario. Having complimentary in-person discussions, moral reasoning questions and answers, role-playing scenarios and other related activities with the children is overall more effective in reinforcing the central themes related to bullying and emotional awareness.

Changes in children’s behaviour was explained through better understanding about the concept of bullying others in the experimental group. We saw how the children reported more bullying behaviour in themselves after the intervention (34.2% vs. 77.5% in the post-test), indicating that they were aware of what bullying entails, and had the emotional awareness to recognize their behaviour. The students in the control group saw no change in their answers about bullying perpetration, as well as no change in their victimization and perpetration behaviours in case of specific types of bullying and aggressive behaviour.

The researchers observed that during the pre-test, the students weren’t able to identify or understand the bullying statements that much and hence showed mixed responses. This was because of their general lack of understanding about the basic concepts of bullying itself. When they underwent the intervention and saw a cartoon with these specific themes presented in storylines that they could relate to, the students were much more responsive and understood the questions and discussions better. They learnt how bullying behaviour could be initiated and what would be the reasons for someone to start this kind of behaviour.

The parents and teachers also communicated that the children were very excited about this program and would patiently wait for the sessions. They also wanted to search for the cartoons themselves on the internet. The need for this type of education is apparent from this. If accessible creative content is developed, the students will engage and participate. One of the parents’ observations was also that a number of students had actively started calling out bullies and perpetrators in their day to day school interactions, as the cartoons showed them that speaking up about being bullied is vital to stop it from happening. The impressive uptake in the post-test awareness of bullying in the experimental group explains that the children were not even aware that they were actually bullied by peers as they thought it was normal before. This research clearly indicated that emotional resilience education with a focus on relevant themes that concern the children like bullying or aggressive behaviour should be part of curriculum and should be reinforced from time to time.

In conclusion, the authors propose continuation of this project on a larger scale with the following recommendations:

The module should be continued for a longer duration with either in-person or online mode of teaching. The hybrid model may run the chance of students losing focus or momentum while switching between modes of instruction.

More themes revolving around the core concept of emotional resilience could be introduced with relevant animated cartoon storylines. These could include base emotions like anger, sadness and happiness. Behavioural modifications can be assessed with evaluation scales relevant to the emotion and behavioural element that is being targeted. Introducing storylines covering basic emotions can ensure that students in this age group get a holistic overview of how to have the language and vocabulary needed to express their emotions, as well as how to regulate them in an emotionally healthy manner.

As part of ongoing research output, a larger sample size can be used in a follow-up study to validate the results of this pilot project.

Building upon the efficacy of this video literacy program, policy change makers and education experts can be approached to incorporate this program into the national curriculum. Academic integration and synchronization with the regulated curriculum will ensure the beneficial effects of building emotional resilience, and developing resilience, in the long run.

Acknowledgement/Funding

This experimental research was funded by the Pakistan Community Resilience Research Network grant (RGIK-14.2) from Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI), Pakistan and Creative Learning, USA. Submission of results and a research paper was a requirement of the granting body.

Authors’ contribution

Dr Faryal Razzaq: Conceptualization, methodology, discussions of results, formatting of paper. General guidelines for the structure. 60% contribution.

Amna Siddiqui: Literature review − 20%.

Sana Ashfaq: Collection of Data and part of literature review: 10%.

Muhammad bin Ashfaq: Collection of Data, part of literature review: 10%.

Competing interests/Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest or conflict of interest. The data analysis was done by the firm CBSR with proper NDA and MoU for a paid task as declared in grant budget.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alonso-Alberca N, San-Juan C, Aldás J, Vozmediano L. Be water: Direct and indirect relations between perceived emotional intelligence and subjective well-being. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2015;67(1):47–54. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aly A, Taylor E, Karnovsky S. Moral Disengagement and Building Resilience to Violent Extremism: An Education Intervention. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. 2014;37(4):369–385. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2014.879379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beheshti M, Taspolat A, Kaya OS, Sapanca HF. Characteristics of Instructional Videos. World Journal on Educational Technology: Current Issues. 2018;10(1):61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Billings CEW, Downey LA, Lomas JE, Lloyd J, Stough C. Emotional Intelligence and scholastic achievement in pre-adolescent children. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;65:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brame, C. J. (2016). Effective Educational Videos: Principles and Guidelines for Maximizing Student Learning from Video Content. CBE Life Sciences Education, 15(4), es6.1-es6.6. 10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cantone E, Piras AP, Vellante M, Preti A, Daníelsdóttir S, D’Aloja E, Bhugra D. Interventions on Bullying and Cyberbullying in Schools: A Systematic Review. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2015;11(1):58–76. doi: 10.2174/1745017901511010058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies L. Learning for state-building: Capacity development, education and fragility. Comparative Education. 2011;47(2):157–180. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2011.554085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, L. (2018). Review of educational initiatives in counter-extremism internationally. What works?.

- Dytham S. The role of popular girls in bullying and intimidating boys and other popular girls in secondary school. British Educational Research Journal. 2018;44(2):212–229. doi: 10.1002/berj.3324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eker, C., & Karadeniz, O. (2014). The Effects of Educational Practice with Cartoons on Learning Outcomes. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(14), 223–234. Retrieved from http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_14_December_2014/25.pdf

- Elipe, P., Rey, R., Del, & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2015). Emotional intelligence in the classroom: An important factor in school violence. In Emotional Intelligence: Current Evidence from Psychophysiological, Educational and Organizational Perspectives.

- Fariha SI, Najam N. Profiles and Patterns of Behavioural and Emotional Problems in School Going Adolescents. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences. 2015;35(2):645–675. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming LC, Jacobsen KH. Bullying among middle-school students in low and middle income countries. Health Promotion International. 2010;25(1):73–84. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney H, Ttofi MM, Farrington DP. Evaluating the effectiveness of school-bullying prevention programs: An updated meta-analytical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2019;45:111–133. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, J., Governale, A., Henry, P., & Nesi, D. (2015). Children and Terrorism (Vol. 29). Retrieved from www.srcd.org/publications/social-

- García-Sancho E, Salguero JM, Fernández-Berrocal P. Relationship between emotional intelligence and aggression: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2014;19(5):584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gini G. Associations between bullying behaviour, psychosomatic complaints, emotional and behavioural problems. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2008;44(9):492–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glew GM, Fan MY, Katon W, Rivara FP, Kernic MA. Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(11):1026–1031. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.11.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib, K., & Soliman, T. (2015). Cartoons’ Effect in Changing Children Mental Response and Behavior. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 3(09), 248. Retrieved from https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation.aspx?paperid=59815

- Karmaliani R, Mcfarlane J, Somani R, Khuwaja HMA, Bhamani SS, Ali TS, Jewkes R. Peer violence perpetration and victimization: Prevalence, associated factors and pathways among 1752 sixth grade boys and girls in schools in Pakistan. Plos One. 2017;12(8):e0180833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khawar R, Malik F. Bullying behavior of Pakistani pre-adolescents: Findings based on Olweus Questionnaire. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research. 2016;31(1):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinos CM, Kipritsi E. The relationship between bullying, victimization, trait emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and empathy among preadolescents. Social Psychology of Education. 2012;15(1):41–58. doi: 10.1007/s11218-011-9168-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakides L, Kaloyirou C, Lindsay G. An analysis of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire using the Rasch measurement model. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;76(4):781–801. doi: 10.1348/000709905X53499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J, Stough C, Hansen K, Downey LA. Brief report: Emotional intelligence, victimisation and bullying in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35(1):207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., & Barsade, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(May 2014), 507–536. 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mayer RE, Gallini JK. When Is an Illustration Worth Ten Thousand Words? Journal of Educational Psychology. 1990;82(4):715–726. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.82.4.715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mian AI. 3.2 Terrorism in Pakistan and its Impact on Children’s Mental Health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;55(10):S5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirahmadi H. Building Resilience against Violent Extremism: A Community-Based Approach. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2016;668(1):129–144. doi: 10.1177/0002716216671303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nizami AT, Hassan TM, Yasir S, Rana MH, Minhas FA. Terrorism in Pakistan: The psychosocial context and why it matters. BJPsych International. 2018;15(1):20–22. doi: 10.1192/bji.2017.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, D. (1996). The revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. University of Bergen, Research Center for Health Promotion.

- Olweus, D. (1993). The Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. British Journal of Educational Psychology Journal of Educational Health, (January 1996), 0–12. 10.1037/t09634-000

- Orakzai SB. Pakistan’s approach to countering violent extremism (CVE): Reframing the policy framework for peacebuilding and development strategies. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. 2019;42(8):755–770. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2017.1415786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Osher D, Kidron Y, Brackett M, Dymnicki A, Jones S, Weissberg RP. Advancing the Science and Practice of Social and Emotional Learning: Looking Back and Moving Forward. Review of Research in Education. 2016;40(1):644–681. doi: 10.3102/0091732X16673595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Jurado, M. D. M. M., Martín, A. B. B., & Linares, J. J. G. (2019). Family functioning, emotional intelligence, and values: Analysis of the relationship with aggressive behavior in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3). 10.3390/ijerph16030478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peterson Jr, B. (2015). Evolutionary Emotional Intelligence for Social Workers: Status and the Psychology of Group Violence. Journal for Deradicalization, 2(2015), 119–137.

- Porche, D. J. (2016). Emotional Intelligence: A Violence Strategy. American Journal of Men’s Health. SAGE Publications Sage CA. 10.1177/1557988316647332 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rana M, Gupta M, Malhi P, Grover S, Kaur M. Prevalence and correlates of bullying perpetration and victimization among school-going adolescents in Chandigarh, North India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;62(5):531–539. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_444_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sas, M., Ponnet, K., Reniers, G., & Hardyns, W. (2020). The role of education in the prevention of radicalization and violent extremism in developing countries. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(6). 10.3390/su12062320

- Sebba J, Robinson C. Evaluation of UNICEF UK’s rights respecting schools award (RRSA) London: UNICEF UK. Citeseer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S. A. A., Yezhuang, T., Shah, A. M., Durrani, D. K., & Shah, S. J. (2018). Fear of terror and psychological well-being: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11). 10.3390/ijerph15112554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shah SJ, Shah SAA, Ullah R, Shah AM. Deviance due to fear of victimization: “emotional intelligence” a game-changer. International Journal of Conflict Management. 2020;31(5):687–707. doi: 10.1108/IJCMA-05-2019-0081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw JA. Children exposed to war/terrorism. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6(4):237–246. doi: 10.1023/B:CCFP.0000006291.10180.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shreesha M, Tyagi SK. Does Animation Facilitate Better Learning in Primary Education? A Comparative Study of Three Different Subjects. Creative Education. 2016;07(13):1800–1809. doi: 10.4236/ce.2016.713183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, N., Gorard, S., & See, B. H. (2017). Non-cognitive impacts of philosophy for children. School of Education, Durham University.

- Solberg ME, Olweus D. Prevalence Estimation of School Bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(3):239–268. doi: 10.1002/ab.10047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens W, Sieckelinck S, Boutellier H. Preventing Violent Extremism: A Review of the Literature. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. 2021;44(4):346–361. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2018.1543144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taher, B., & Rahmatollah Soltani. (2011). &. The Pedagogical Values of Cartoons. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(4), 19–23. Retrieved from https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/RHSS/article/view/1267

- Taylor, E. (2018). (Lily). Reaching out to the disaffected: mindfulness and art therapy for building resilience to violent extremism. Learning: Research and Practice, 4(1), 39–51. 10.1080/23735082.2018.1428109

- Taylor E, Taylor PC, Karnovsky S, Aly A, Taylor N. Beyond Bali”: a transformative education approach for developing community resilience to violent extremism. Asia Pacific Journal of Education. 2017;37(2):193–204. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2016.1240661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Theriault J, Krause P, Young L. Know thy enemy: Education about terrorism improves social attitudes toward terrorists. Journal of Educational Psychology: General. 2017;146(3):305. doi: 10.1037/xge0000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Farrington DP, Lösel F. School bullying as a predictor of violence later in life: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2012;17(5):405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willmot, P., Bramhall, M., & Radley, K. (2012). Using digital video reporting to inspire and engage students. The Higher Education Academy. Citeseer. Retrieved from https://www.raeng.org.uk/publications/other/using-digital-video-reporting

- Zeidner, M., & Matthews, G. (2018). Grace Under Pressure in Educational Contexts: Emotional Intelligence, Stress, and Coping. In Emotional Intelligence in Education (pp. 83–110). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-90633-1_4

- Zimmerman FJ, Glew GM, Christakis DA, Katon W. Early cognitive stimulation, emotional support, and television watching as predictors of subsequent bullying among grade-school children. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(4):384–388. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]