Abstract

Mental health is one of the major causes of disability worldwide, and mental health problems such as depression and anxiety are ranked among the top 25 leading causes of disease burden in the world. This burden is considerable over the lifetime of both men and women and in various settings and ages. This study aims to compare the mental health status of people in China and Pakistan and to highlight the mental health laws and policies during COVID-19 and afterwards. According to the literature on mental health, before the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health problems increased gradually, but during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, an abrupt surge occurred in mental health problems. To overcome mental health disorders, most (but not all) countries have mental health laws, but some countries ignore mental health disorders. China is one such country that has mental health laws and policies and, during the COVID-19 pandemic, China made beneficial and robust policies and laws, thereby succeeding in defeating the COVID-19 pandemic. The mortality rate and financial loss were also lower than in other countries. While Pakistan has mental health laws and general health policies, the law is only limited to paperwork and books. When it came to COVID-19, Pakistan did not make any specific laws to overcome the virus. Mental health problems are greater in Pakistan than in China, and China’s mental health laws and policies are more robust and more widely implemented than those in Pakistan. We conclude that there are fewer mental health issues in China than in Pakistan both before and since the COVID-19 pandemic. China has strong mental health laws and these are robustly implemented, while the mental health law in Pakistan is not applied in practice.

Introduction

Mental illnesses are one of the primary causes of the worldwide health burden. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2019, depression and anxiety were among the top 25 leading causes of disease burden worldwide in 2019.1 This burden is considerable over the lifetime of both men and women and in various settings.2 Perhaps more concerning, despite clear evidence of treatments that minimise their impact, there has been no reduction in the global prevalence or burden of either depression or anxiety since 1990.3 4 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one billion people are presently living with mental problems, 3 million people die from alcohol use each year, while one person dies by suicide every 40 seconds. In the 15–29 years age group, suicide is the fourth leading cause of death.5 6 In low- and middle-income countries, most patients with mental illness do not receive treatment and care due to the lack of facilities. According to the GBD Study 2017, self-harm and mental illness accounted for 8.8% and 16.6% of the global burden of disease, respectively.7 The WHO Mental Health Atlas 2017 reported that less than 2% of the governments’ health budgets were spent on mental health, while a considerable part of these budgets went to specialised mental health hospitals.8

Furthermore, the WHO reported that 75% of countries do not include mental health in their insurance plans. The limited government support for mental health is due to economic conditions. Many people have no access to mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries.9–11 About 50% of mental health disorders start at the age of 14 years, and more than 160 million people require humanitarian aid for mental health due to natural disasters, conflicts or other emergencies. Due to such crises, the patients with mental disorders have doubled. One in five individuals affected by conflicts has a mental health condition.11 In this context, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has aroused many concerns about its impact on mental health, in terms of direct long-term economic effects, psychological effects and social ramifications. Individuals infected by COVID-19 have mortality and significant health consequences.12 Mental health issues increased during the COVID-19 pandemic in different regions and countries, with a global prevalence estimate of 26.9% for anxiety, 36.5% for stress, 24.1% for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 50.0% for psychological distress, 28.0% for depression and 27.6% for sleep problems.13

The comparison provides a clearer picture as to which country had more mental disorders and which country implemented better policies, so that improved policies can be adopted for the betterment of humankind. This study will also provide clear data and will be a guiding tool for further research.

Mental health in China

China’s economic reforms have been enormously successful during the past three decades. On the other hand, rapid urbanisation and economic expansion are posing new difficulties to the country’s mental health system. Mental healthcare has historically been a low priority in China for a variety of reasons, but both the international community and the media have taken a strong interest in these services during the last 5 years. The majority of international specialists have evaluated China’s mental health system using Western criteria, focusing on the infrequent, unfavourable incidents that occur.14

In China, the most common kind of mental disorders is mood disorders with a lifetime prevalence of 7.4%,15 while the disease burden for mental disorders made up 13% of all non-communicable diseases.16 17

According to an epidemiological survey conducted in four Chinese provinces, 17.6% of the participants suffered from mental disorders including depression (6.1%), anxiety disorders (5.6%) and drug use disorders (5.9%).18 According to the WHO, the global recognition rate for mental disorders is roughly 50%, and China’s recognition rate is significantly lower than the global average. Taking depression as an example, in Shanghai only 21% of people recognised that they were depressed. Furthermore, the rate of mental disorder diagnosis and treatment is poor, with only about 150 persons per 100 000 obtaining treatment for major mental disorders on average. Treatment rates for major mental disorders are 17 times higher in high-income countries than in low-income countries.17

Many diseases are episodic, and the chance of relapse is significant.19 Provision of supplementary, customised psychological therapies to manage subthreshold symptoms appears to be critical in reducing impairment and improving quality of life.20 Despite the significant frequency, only one-fifth of people with mood disorders have ever sought treatment from a mental health professional.21 The reasons for China’s significant unmet mental health needs are numerous. There is an unequal distribution of resources between major cities and rural areas, as well as a limited mental health workforce, particularly a shortage of professional social workers and psychological therapists. The high cost of psychological counselling is exacerbated by the lack of medical insurance coverage.22 23 In recent years, the ‘686 Project’, also known as the Central Government Support for Local Management and Treatment of Serious Mental Illness Project, has helped many patients with severe mental illnesses—particularly schizophrenia—to gain more convenient and even free treatment and recovery services. To improve the population’s mental health, more emphasis must be put on bridging the gap experienced by people with non-psychotic diseases.23

In China, mental health resources and service capability are insufficient because of the following: (1) financial investment: the Chinese government’s per capita investment in psychiatric hospitals is about US$1.07,24 compared with US$35.06 in high-income countries during the same period; (2) hospital beds: the number of psychiatric beds in China per 10 000 people is 3.15, compared with 7.13 beds in high-income countries25; (3) professionals: for every 100 000 people in China, there are 3 professionals.25 26 Simultaneously, China has challenges such as attracting mental health professionals and a shortage of vocational rehabilitation personnel. Furthermore, China’s mental health resources are unevenly distributed, with the majority of hospitals and experts clustered in provincial capitals and the more developed eastern regions. It is reported that 47.21% of institutions, 42.06% of mental beds, 48.65% of physicians and 45.25% of nurses are located in 11 eastern provinces. Furthermore, the capacity of mental health staff in grassroots medical facilities is low, and the majority of the personnel are part-time.17 25 26

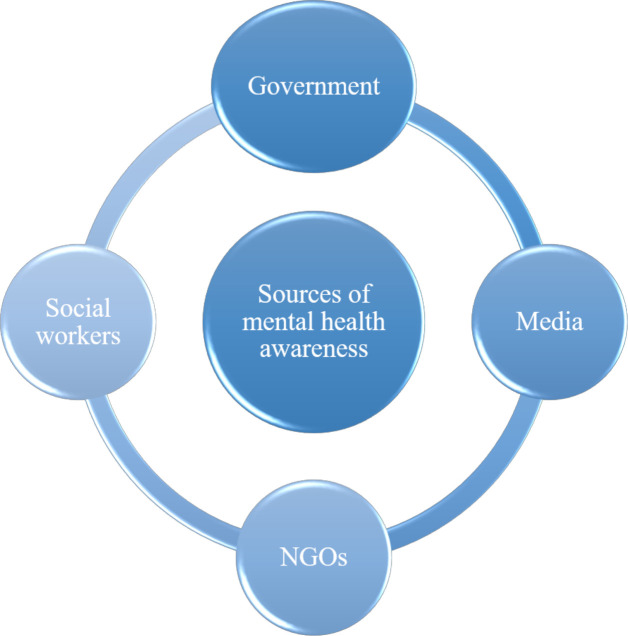

In China, there are only 2.19 licensed psychiatrists and 5.51 licensed nurses per 100 000 people.17 22 There is also a scarcity of counselling psychologists (estimated at 30 000–40 000 in the whole country), with a lack of an official system for accreditation, registration and licensing.27 28 Furthermore, the number of social workers in China is low with a total of roughly one million, and few of them are certified to provide mental health treatments. People’s awareness about mental health and mental health disorders has been increasing. Some of the sources of awareness about mental health are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sources of mental health awareness in China and Pakistan. Government plays an important role, as well as media (social and electronic), different non-government organisations (NGOs) and social workers.

COVID-19 and mental health status in China

The first case of COVID-19 was reported in Wuhan, China, and suddenly the virus spread throughout the globe.29 30 According to surveys of people’s mental health conducted nationwide in China during the COVID-19 pandemic, 35% of those with COVID-19 experienced stress, 30% experienced depression, 34% experienced anxiety and 25.2% experienced PTSD.17 27 31 COVID-19 caused sleep disturbance and PTSD in frontline medical staff as well.32–34 In China, there are approximately one million social workers, which is few for such a large population, and very few are skilled in delivering mental health services. During the pandemic, telehealth was used in universities and hospitals to deliver mental health services to some patients.35 36 Some people may seek help online; however, internet counselling may not be successful for all those who require it, and it can often result in secondary trauma due to the inability to ‘be there’ and ‘know something’.37 Previous reports38 have detailed the technical and logistic issues that mental health therapists face when providing online counselling. Poor mental health literacy, as well as the stigma associated with mental diseases, may play a role in the low use of mental health treatments.17 39 During the COVID-19 pandemic, when the general population was at home in quarantine, social media was the main source of public mental health services, information dissemination and psychological support. Mental health professionals and government workers together actively worked to enhance the mental health resilience of the public and ensure information transparency. To reduce unwarranted anxiety and panic among the public caused by fake news spread through social media, Chinese health experts had daily press conferences to deliver reliable and accurate data and news to the general population about COVID-19. Mental health education was combined with COVID-19 daily updates to increase the awareness of the general public of the pandemic. Scientific articles and books and videos were published to educate people about the pandemic. The main objectives of these publications were to strengthen people mentally.27 40 Books on psychoeducation and mental disorders associated with COVID-19 were also published.41 42 More than 300 mental health hotline services operated online counselling; hospitals and other famous applications offered online self-assessment scales for mental well-being. Telepsychiatry, telepsychology and telecommunication were enhanced to serve the general population on time and to avoid mental health problems and spreading infections.43

According to surveys, the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to cause mental health crises in regions with a large number of confirmed cases and deaths such as in Wuhan.44 Another study observed that 53.8% out of 1210 participants in a study on the psychological impact on the general population of China within the first 2 weeks of the COVID-19 epidemic stated that the pandemic had had a moderate to severe psychological impact on them.45 The quality of sleep and mental health for self-isolating people at home in central China was found to be poor, with high anxiety and low sleep quality. The behavioural and emotional contagions escalated epidemic-related negative affect responses, fear at both collective and individual levels, and psychological distress increased.46–48 The number of psychologically distressed people was greater in areas with high levels of infection than in areas with lower rates of infection and, when the awareness of death from COVID-19 increased, the fear of death anxiety and fear of infection increased in the general population.49 Death anxiety and fear can be managed by an anxiety buffering system.50 China provides facilities to its citizens. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the government built a hospital of 1000 beds in just 10 days to treat patients in Wuhan. The Chinese government also built hospitals for COVID-19 emergencies in just 5 days in some other provinces.51 52

Mental Health Law in China

The first Mental Health Law in China came into effect on 1 May 2013. This was the biggest event in the mental health field in China. The present review introduces its legislative process, its main idea and the principle and essence of formulating this Mental Health Law. Current problems with the law and possible countermeasures are also discussed.17 53 The main points of the law are to give legal rights and standard mental health services to mentally ill persons as well as treatment, prevention and rehabilitation, improve psychological well-being and maintenance of citizens, and take care of the personal safety and dignity, education, medical services and welfare of a person with mental illness. All organisations and individuals must accept and respect mentally ill people and not stigmatise, abuse or humiliate them. Violation of the rights of a mentally ill person is prohibited. The state supports and encourages the technological and scientific diagnosis, prevention, rehabilitation and treatment of mental disorders. Organisations and the government will create opportunities for specific employees and, in case of emergency, give psychological support to the people. In schools, teachers will teach students about psychological well-being and mental health. In jails, prisons and drug rehabilitation centres, the government will provide guidance and counselling. Family members will live in a friendly home environment to alleviate and prevent mental disorders. The government will support media and organisations to promote knowledge about mental health. Persons with severe mental illness will be treated as inpatients. Disabled people’s organisations and rehabilitation organisations will organise activities that meet the rehabilitation requirements for mentally ill people. The high authorities of the state are responsible for implementing the laws and regulations of mental health. The state departments will support and help mental health and give proper financial support to the state budget. A person who is not authorised or registered to treat mental health issues and is found to be practising or treating mental health issues will be issued a letter from the authorities or fined 5000 Chinese Yuan but not more than 10 000 Chinese Yuan.54

COVID-19 and mental health laws in China

The Chinese government made proper guidelines and laws for mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. The main points of these guidelines are that all the municipalities, autonomous regions and provinces are working under the central government in response to the new pneumonia pandemic and all the necessary financial and organisational guarantees will be provided. The national health and mental health societies and associations will mobilise psychologists, psychiatrists and experts with experience in psychological crises. A psychological rescue group will be formed to provide guidance and carry out psychological counselling in an orderly manner. They will treat psychological issues and endorse social stability. For affected people, the government will provide mental health services and try to prevent the psychological impact of the pandemic. They will identify and manage severely mentally ill people to prevent them from impulsive behaviour and suicide. They will assess the population and distinguish high-risk persons from the general population. They will conduct mental health education for the general population and provide proper treatment and psychological intervention for high-risk groups. Rescue teams may work alone or collaborate as a group with a comprehensive medical team. Experts in mental health will conduct research. Online services, as well as psychological workers, and the organisation will be on duty 24 hours a day and 7 days a week. In diagnosing a patient in the initial stage of treatment and isolation, proper treatment and counselling will be started. According to the tolerance level of the patient, truthful and objective communication with the patient should be given to better form a rapport. Convey the information to the relatives of the patient and assist them. In patients with anxiety and respiratory distress, treat the severe respiratory disease first after calming the patient, and also pay attention to their emotional and behavioural disorders. The government arranges training for doctors and nurses to teach them how to deal with depression and anxiety during the outbreak. To eliminate the stress of front-line medical workers, the government provides them with logistic supports and schedule them to go to an isolated area once a month.55 56

Mental health in Pakistan

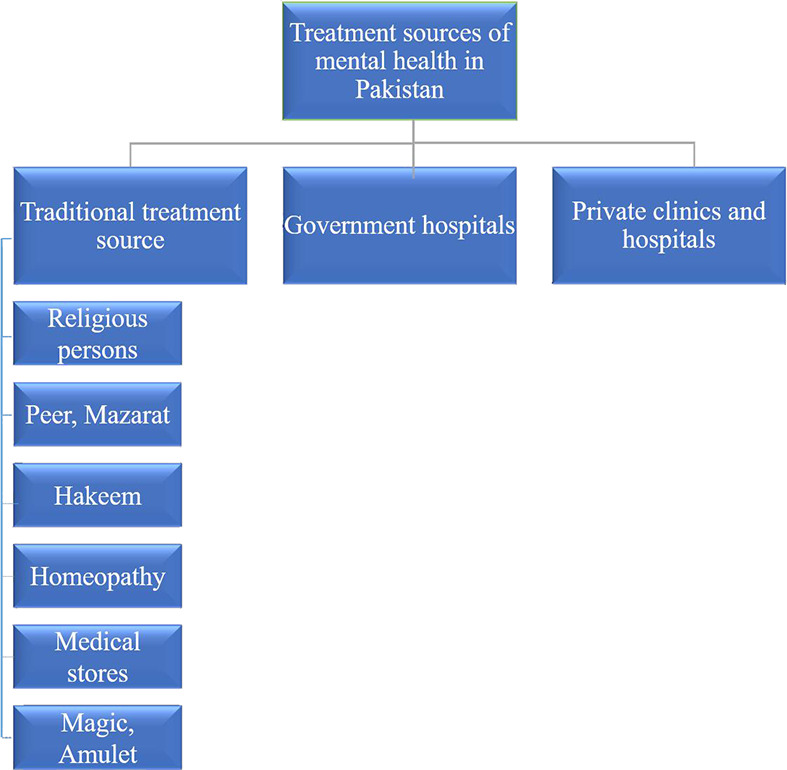

Pakistan is a low-income country and is 34th out of 37 low-income countries.57 The per capita gross domestic product is about US$1375, and the infant mortality rate is 69 deaths per 1000 live births.58 Pakistan has poor mental health and gives mental health a low priority, as in other developing countries.59 Overall, there are more mental health problems in Pakistan and women tend to have more mental health issues than men, possibly due to the low literacy rate among women.60 The WHO published a report in 2012; which showed that 13 337 suicides occurred in Pakistan, the rate was 7.5 per 100 000 people, and the number was more significant in women. The prevalence of suicide increased by 2.6% compared with previous studies conducted in 2000.61 Depression and anxiety were reported in 10%–16% of adults with signs and symptoms ranging from mild to severe, while 10% of the population had mental disorders, of which 1%–2% suffered from severe mental disorders such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.62 While 10%–20% of children and adolescents in Pakistan have behavioural and mental disorders, 9.99 per 1000 people have epilepsy.63–65 Approximately 6.45 million people used illegal drugs, of which 70% were men aged 15–40 years. The most common illegal drugs are chars (marijuana), benzodiazepines, heroin and ice. Pakistan has a high rate of mental disorders, a low literacy rate, a lack of awareness and a cultural stigma around mental illness. People tend to seek help from spiritual healers. There is also a shortage of specialised mental health providers and units, limited financial resources and a low budget for mental health.64 66–68 For the whole population, there are fewer than 500 psychiatrists and only four large psychiatric hospitals and 654 psychiatric units in general hospitals. This ratio creates a big treatment gap, with about 90% of people with common mental disorders being untreated.59 69 Psychiatric beds are about 2.1 per 100 000 people. Children with mental disorders reported difficulties, along with their family members. Of the psychiatric beds, only about 1% are paediatric beds. Outpatient mental health facilities cover about 3729 per 100 000 people, of which only 1% is designated for paediatric services.69 70 In Pakistan, there are avenues through which people seek treatment for mental health. The sources where people seek treatment are shown in figure 2. A comparison of depression, anxiety and drug use between China and Pakistan before the COVID-19 pandemic is shown in table 1.

Figure 2.

Different sources of treatment for mental health problems in Pakistan. The ‘traditional treatment sources’ for mentally-ill persons include consulting religious clergy, peers, mazarat, medical stores, homeopathy and hakeems. Family members bring the person to the clergy, who treats them using religious methods. Some people have strong beliefs about peers (the people who claim to be religious but in fact are not) as well as graves and shrines (mazarat), so most people with mental illness are made to visit these peers and shrines (mazarat) for spiritual healings. However, non-believers consider such treatment as wrong. Illegal medical stores are also very common, especially in rural areas, and the owners of these stores often practice unlicensed treatment.

Table 1.

Mental health in China and Pakistan before the COVID-19 pandemic

| Mental health | China | Pakistan |

| Depression | 6.1% (81.1 million) | 10%–16% (about 27.5 million) |

| Anxiety | 5.6% (74.5 million) | 10%–16% (about 27.5 million) |

| Drug use | 5.9% (78.5 million) | 3.3% (6.45 million) |

Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan

As in the rest of the world, COVID-19 had a similar impact on mental health in Pakistan with an increase in the average level of stress, anxiety and depression.69 The COVID-19 pandemic also had a negative impact on mental health issues such as grief, helplessness, psychological distress, shame, post-traumatic symptoms, anger, stigma, depression, panic attacks, anxiety, loneliness, fear and anger.71 72 Community living depends on family interaction, social support and cultural activities to keep people busy and happy. During the COVID-19 lockdowns, these relationships were cut off, causing feelings of psychological distress, loneliness and negative emotions to develop. People also experienced fear of infection and death, as a result of which symptoms of depression, anger, stress and anxiety developed.71 In Pakistan, lockdowns were enforced in some big cities, which helped to control the infection.73 Mental health can be affected by many factors including psychological well-being, emotional welfare and psychological functioning. While emotional welfare includes uncertainty about this novel disease, it is also impacted by the unpredictability of a new risk (eg, needing to quarantine, social distancing and self-isolation). COVID-19 impaired interpersonal relationships, perpetuating behavioural and emotional disorders, as well as the propensity for being traumatised, and negatively impacted social functioning. Healthcare conditions in Pakistan are deteriorating on a daily basis, necessitating a holistic approach to disease management that addresses both physical and mental health issues.74 A comparison of depression, anxiety and stress between China and Pakistan during the COVID-19 pandemic is shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in China and Pakistan

| Mental health | China | Pakistan |

| Depression | 30% (420.6 million) | 33% (72.9 million) |

| Anxiety | 34% (476.68 million) | 40% (88.4 million) |

| PTSD | 25.2% (353.3 million) | 34.9% (77.1 million) |

| Stress | 35.5% (497.7 million) | 27% (59.6 million) |

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a survey of students was conducted by Salman et al.75 According to this survey, 14.6% of students had severe anxiety and 19.6% had severe obsessions about COVID-19. In the general population, the prevalence of depression was 33%, anxiety was 40% and stress was 27%,76 while the prevalence of PTSD was 34.9%.77 Another survey found that 92.9% of healthcare professionals were aware of COVID-19, and the prevalence of anxiety and depression among them was 4.6% and 14.3%, respectively.75 78

Mental Health Law of Pakistan 2001

After the independence of Pakistan in 1947, the Lunacy Act of 1912 was implemented for the newly created country. The Lunacy Act was implemented previously in the subcontinent. The act emphasises detention rather than treatment and development in therapy, particularly the advent of psychiatric medications. Advocates for the change of this statute were active throughout the 1970s and beyond. In 1992, the Pakistani government suggested new mental health laws and circulated a draft to psychiatrists for feedback. A conference of the Pakistan Psychiatric Society was held in Islamabad (the capital of Pakistan) in 2001, and the Lunacy Act of 1912 was repealed by the Mental Health Act of 2001. The main points of the Mental Health Act of 2001 were to emphasise mental health prevention and promotion as well as protecting the fundamental rights of patients, providing access to mental healthcare, giving proper rights to caregivers and family members, providing involuntary and voluntary treatment to mentally ill people, properly addressing judicial system issues and other law enforcement issues for those with mental illness, providing mechanisms for monitoring and regulating involuntary admission and treatment, and mechanisms for mental health laws into action. Health became a provincial rather than a federal issue with the 18th amendment to Pakistan’s constitution. The Federal Mental Health Authority was dissolved on 8 April 2010 and the responsibilities were transferred to the provinces which were tasked with passing adequate legislation and mental health laws through their assemblies.79–82

Mental Health Law of Pakistan 2010

After the amendment of the constitution on 8 April 2010, the health sector came under the jurisdiction of the provinces. Each province passed a bill for mental health laws in their respective assemblies. The main areas of these laws were the following: (1) the government has to maintain and establish psychiatric facilities for treatment rehabilitation and assessment; (2) separate units for men and women, geriatrics, children and adolescents, substance rehabilitation and those convicted of a criminal offence; (3) community-based mental health services will be established to provide support to persons with mental illness, their families and caretakers.

According to the Act, inpatient treatment was divided into four categories: (1) admission; (2) assessment; (3) treatment; and (4) urgent admission and emergency holding. A patient admitted to a psychiatric facility based on an application for assessment may be held for up to 28 days and not more than 28 days. The patient has the right of one appeal in court within 14 days against the order of detention. After 72 hours from the moment when the patient is admitted to the psychiatric facility, an urgent application is no longer valid. After the recovery of the individual, the guardian or relative will provide a proper application to the magistrate after discharge. The magistrate will take the decision and inquiry about whether to dismiss the application or not. In cases where a foreigner is detained, a patient placement agreement will be reached with the foreign state and the federal government in collaboration with the foreign state will make an application with the agent of a foreign state.80 82–86

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa health policy of 2018–2025

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa created a health policy 2018–2025 to overcome mental health issues. Non-communicable diseases (eg, mental disorders, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and injuries) are the major causes of mortality and morbidity in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. About three decades of sociopolitical instability, violence, dislocation, regional conflict, economic uncertainty and regime change created a high prevalence of mental health disorders. In this policy, there are just a few points pertaining to mental health: (1) the government will improve health services and give packages to health facilities; (2) mental health will be a particular focus area; (3) improve the standard of delivery service in healthcare units; (4) provide proper training to healthcare workers; (5) provide supervision and skills improvement for doctors; (6) provide psychosocial and physical rehabilitation services for people affected by long-term injuries and violence; (7) establish rescue services, psychosocial support services and mental health initiatives to expand coverage and scope; and (8) provide incentives for training in psychiatry, forensic medicine, radiology and pathology.86

Discussion

Developing countries have many challenges in dealing with political, social and economic problems. One challenge is to assure the well-being and health of the people. Governmental healthcare planners also face a lot of challenges in providing nutrition, sanitation, immunisation and clean water. This is why mental health is often a lower priority. Nevertheless, mental health disorders continue to increase in their impact. According to one survey by WHO, depression will be a major cause of disability by 2030, with about 280 million people having depression worldwide.87 COVID-19 has only hastened this trajectory.

The Pakistani government has given a low priority to mental health since the country’s independence. However, the prevalence and incidence of mental health issues have tremendously increased due to terrorism, disruption of the social fabric, insecurity, unemployment, economic problems and political uncertainty. In Pakistan, 39% of the population are living below the poverty level. However, presently there is more awareness about mental health issues among the general population and people are more likely to seek help in a psychiatric clinic. Education and media play an important role in people’s increased awareness of psychiatric issues.88

There is a significant difference between China and Pakistan when it comes to mental health. As mentioned earlier, both are developing countries, but China is making huge progress in finance and other aspects. There are more mental health issues in developing and low-income countries than in developed countries. The majority of the people with mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries receive no treatment. There is also a shortage of medical facilities and psychiatrists. In Pakistan, the number of psychiatrists is very low while the population continues to increase. Quarantined individuals in some provinces of Pakistan had to stay in tents during the COVID-19 pandemic while China was able to construct field hospitals in as little as 10 days.

The lockdown of the whole country to limit infections also increased mental problems. In China, there was a complete lockdown in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. People were isolated and alone in their homes and there was no physical interaction with the outside world, society and relatives. Most of the markets were closed. Because of this, mental health issues increased.89 On the other hand, Pakistan had a semi-lockdown but mental health problems increased because of economic issues. People lost their jobs and wages. Social functions were discontinued and there were no social gatherings. China is a financially stable country, unlike Pakistan. In China, there are online services for the delivery of food and necessities whereas Pakistan has no such online services.90

Comparing the mental health of China and Pakistan during and before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese population had fewer mental health problems than the Pakistani population. In China, there is a law for mental health, which has been implemented and has produced fruitful results. In Pakistan, there is also a law for mental health but it is on paper and yet to be implemented. The Mental Health Law is not implemented and neither the authorities nor practitioners follow the Mental Health Laws. After independence, there was a Lunacy Act for mental health in Pakistan. In 2001, Pakistan made its own Mental Health Law and since 2010, every province has had its own Mental Health Law. From independence to the present time, Pakistan has had Mental Health Laws but, unfortunately, no one ensures that they are followed. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese government made an emergency law for its people, frontline health workers and officials to implement these laws. Everyone followed the law, which is why mental health is better in China than in Pakistan. China first issued a notification to all high authorities to unite and fight against the novel coronavirus. They activated all the relevant departments and authorities to counter the COVID-19 pandemic and provided financial support to these departments to work freely and everywhere in the country wherever they felt there was a deficiency. The government focused on the prevention and control of the disease and also provided psychological support to people affected by COVID-19. The government also focused on frontline medical workers and provided facilities for them. The Chinese government provided isolation centres and treatment facilities to patients with severe mental illness so that they would not harm themselves or others.55 The government also worked on vaccination drives to vaccinate against COVID-19. Finally, China created the COVID-19 vaccine Sinopharm, which was approved by WHO for use on an emergency basis.91 Pakistan has emergency policies but they are not related to mental health. These policies are also not well implemented. There is also a shortage of mental health hospitals and experts. In some general hospitals, there are psychiatric units but even these units lack the much-needed beds.

Conclusion

Mental health issues are present worldwide and are currently on the rise. During the COVID-19 pandemic, an abrupt surge in mental health issues occurred, especially depression, anxiety, stress and PTSD. Pandemic-related mental health issues increased in both China and Pakistan. China’s COVID-19 laws and policies were vigorously implemented and carried out to fight against mental health issues. In contrast, Pakistan did not make any mental health laws or policies for COVID-19.

Biography

S. Mudasser Shah is a PhD Scholar at the Psychosomatics and Psychiatry Department, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China. The author obtained a bachelor's degree of Science and a master's degree of Science (Psychology) from Islamia College University and obtained a master's degree of Philosophy (M.Phil.) in Psychology from Hazara University, Pakistan in 2016. His main research interests include psychosomatics and mood disorders.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceptualisation of study: YY, WJ and SMS. Article search: SMS. Writing original draft and preparation: SMS. Reviewing article: YY, WJ, TS and WX.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators . Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022;9:137–50. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jorm AF, Patten SB, Brugha TS, et al. Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders? Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry 2017;16:90–9. 10.1002/wps.20388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet 2016;387:1672–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00390-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization . Suicide, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 5. World Health Organization . Suicide: one person dies every 40 seconds, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/09-09-2019-suicide-one-person-dies-every-40-seconds [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 6. World Health Organization . Harmful use of alcohol kills more than 3 million people each year, most of them men, 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/21-09-2018-harmful-use-of-alcohol-kills-more-than-3-million-people-each-year-most-of-them-men [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 7. Rathod S, Pinninti N, Irfan M, et al. Mental health service provision in low- and middle-income countries. Health Serv Insights 2017;10:117863291769435. 10.1177/1178632917694350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vigo DV, Kestel D, Pendakur K, et al. Disease burden and government spending on mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, and self-harm: cross-sectional, ecological study of health system response in the Americas. Lancet Public Health 2019;4:e89–96. 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30203-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization . Who highlights urgent need to transform mental health and mental health care, 2022. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-06-2022-who-highlights-urgent-need-to-transform-mental-health-and-mental-health-care [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 10. Saraceno B, Saxena S. Mental health resources in the world: results from Project Atlas of the WHO. World Psychiatry 2002;1:40–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Bank . Mental health: lessons learned in 2020 for 2021 and forward, 2021. Available: https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/mental-health-lessons-learned-2020-2021-and-forward [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 12. Villani L, Pastorino R, Molinari E, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being of students in an Italian university: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Global Health 2021;17:39. 10.1186/s12992-021-00680-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nochaiwong S, Ruengorn C, Thavorn K, et al. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2021;11:10173. 10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu J, Ma H, He Y-L, et al. Mental health system in China: history, recent service reform and future challenges. World Psychiatry 2011;10:210–6. 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00059.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:211–24. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Charlson FJ, Baxter AJ, Cheng HG, et al. The burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in China and India: a systematic analysis of community representative epidemiological studies. Lancet 2016;388:376–89. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30590-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Que J, Lu L, Shi L. Development and challenges of mental health in China. Gen Psychiatry 2019;32:e100053. 10.1136/gpsych-2019-100053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001-05: an epidemiological survey. Lancet 2009;373:2041–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gitlin MJ, Miklowitz DJ. The difficult lives of individuals with bipolar disorder: a review of functional outcomes and their implications for treatment. J Affect Disord 2017;209:147–54. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miziou S, Tsitsipa E, Moysidou S, et al. Psychosocial treatment and interventions for bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2015;14:19. 10.1186/s12991-015-0057-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patel V, Xiao S, Chen H, et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet 2016;388:3074–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00160-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liang D, Mays VM, Hwang W-C. Integrated mental health services in China: challenges and planning for the future. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:107–22. 10.1093/heapol/czx137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang X, Zhang X, Chen X. Happiness in the air: how does a dirty sky affect mental health and subjective well-being? J Environ Econ Manage 2017;85:81–94. 10.1016/j.jeem.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. China Union Medical Press . National health and family planning commission. In: China health and family planning statistical yearbook 2017. GHDx, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shi CH, Ma N. Analysis of mental health resources in China in 2015. Papers of the 16th National Psychiatric Conference of the Chinese Medical Association, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization . Mental health atlas 2017 country profile: China, 2017. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/mental-health-atlas-2017-country-profile-china [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 27. Ju Y, Zhang Y, Wang X, et al. China's mental health support in response to COVID-19: progression, challenges and reflection. Global Health 2020;16:102. 10.1186/s12992-020-00634-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. China Net Radio . The sixth China psychoanalysis conference held in Shanghai. data shows that there is a lack of 430,000 psychological consultants in China, 2019. Available: http://www.cnr.cn/shanghai/tt/20190511/t20190511_524609035.shtml [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 29. Gu Y, Zhu Y, Xu F, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among patients with COVID-19 treated in the Fangcang Shelter Hospital in China. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2021;13:e12443. 10.1111/appy.12443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou X, Liu J, Wang W, et al. China says no towards the second large-scale COVID-19 outbreak: voices from the online public. Gen Psychiatry 2021;34:e100517. 10.1136/gpsych-2021-100517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peng D, Wang Z, Xu Y. Challenges and opportunities in mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Psychiatry 2020;33:e100275. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li L, Wang X, Tan J, et al. Influence of sleep difficulty on post-traumatic stress symptoms among frontline medical staff during COVID-19 pandemic in China. Psychol Health Med 2022;27:1924-1936. 10.1080/13548506.2021.1981411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xi Z. The angel in white has collapsed, who will protect it? 2020. Available: https://m.huxiu.com/article/338242.html [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 34. Business Today . Coronavirus: China starts mental health services for people in trauma, 2020. Available: https://www.businesstoday.in/current/world/coronavirus-china-starts-mental-health-services-for-people-in-trauma-in-fight-against-epidemic/story/396096.html [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 35. Peretti-Watel P, Alleaume C, Léger D, et al. Anxiety, depression and sleep problems: a second wave of COVID-19. Gen Psychiatry 2020;33:e100299. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhuo K, Gao C, Wang X, et al. Stress and sleep: a survey based on wearable sleep trackers among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Psychiatry 2020;33:e100260. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raphael B, Ma H. Mass catastrophe and disaster psychiatry. Mol Psychiatry 2011;16:247–51. 10.1038/mp.2010.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:e15–16. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen Y, Bennett D, Clarke R, et al. Patterns and correlates of major depression in Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study of 0.5 million men and women. Psychol Med 2017;47:958–70. 10.1017/S0033291716002889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:e17–18. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lu L, Wang G. Handbook of practical tips on mental health during Covid-19 epidemic. Peking University Medical Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cheng W, Zhang F, Hua Y, et al. Development of a psychological first-aid model in inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Gen Psychiatry 2020;33:e100292. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen S, Li F, Lin C. Challenges and recommendations for mental health providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the experience of China’s First University-based mental health team. Global Health 2020;16:59. 10.1186/s12992-020-00591-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dong L, Bouey J, Bouey J. Public mental health crisis during COVID-19 pandemic, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26:1616–8. 10.3201/eid2607.200407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17. 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [Epub ahead of print: 06 03 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, et al. Social capital and sleep quality in individuals who self-isolated for 14 days during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in January 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit 2020;26:e923921. 10.12659/MSM.923921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shultz JM, Cooper JL, Baingana F, et al. The role of fear-related behaviors in the 2013-2016 West Africa Ebola virus disease outbreak. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016;18:104. 10.1007/s11920-016-0741-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang X, Chen J. Isolation and mental health: challenges and experiences from China. Gen Psychiatry 2021;34:e100565. 10.1136/gpsych-2021-100565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health 2020;16:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Maxfield M, John S, Pyszczynski T. A terror management perspective on the role of death-related anxiety in psychological dysfunction. Humanist Psychol 2014;42:35–53. 10.1080/08873267.2012.732155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ankel S. A construction expert broke down how China built an emergency hospital to treat Wuhan coronavirus patients in just 10 days, 2020. Available: https://www.businessinsider.com/how-china-managed-build-entirely-new-hospital-in-10-days-2020-2 [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 52. McDonald J . China builds hospital in 5 days after surge in virus cases, 2021. AP News. Available: https://apnews.com/article/beijing-health-coronavirus-pandemic-wuhan-china-c555525ecdaea032b6d1bc1ec2894513 [Accessed 2 July 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shao Y, Wang J, Xie B. The first mental health law of China. Asian J Psychiatr 2015;13:72–4. 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chen H, Phillips M, Cheng H, et al. Mental health law of the People's Republic of China (English translation with annotations): translated and annotated version of China's new mental health law. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2012;24:305–21. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chinese Offical . Notice on issuing the guiding principles for emergency psychological crisis intervention of the novel coronavirus pneumonia epidemic. China, 2020. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3577/202001/6adc08b966594253b2b791be5c3b9467.shtml [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 56. Chinese Offical . Notice on the establishment of a psychological assistance Hotline in response to the epidemic. China, 2020. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s3577/202002/8f832e99f446461a87fbdceece1fdb02.shtml [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 57. Government of Pakistan . Pakistan economic survey 2019-20: finance department, 2020. Available: https://www.finance.gov.pk/survey_1920.html [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 58. Government of Pakistan . Pakistan economic survey 2016-17. economic department, 2016. Available: https://www.finance.gov.pk/survey_1617.html [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 59. Sikander S. Pakistan. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:845. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30387-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shah SM, Jahangir M, Xu W, et al. Reliability and validity of the Urdu version of psychosomatic symptoms scale in Pakistani patients. Front Psychol 2022;13:861859. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.861859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. World Health Organization . Preventing suicide: a global imperative, 2014. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/131056/8/9789241564878_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 62. Ansari I. Mental health Pakistan: optimizing brains. Int J Emerg Ment Heal Hum Resil 2015;17:288. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Khan F, Shehzad RK, Chaudhry HR. Child and adolescent mental health services in Pakistan: current situation, future directions and possible solutions. Int Psychiatry 2008;5:86–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Munawar K, Abdul Khaiyom JH, Bokharey IZ, et al. A systematic review of mental health literacy in Pakistan. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2020;12:e12408. 10.1111/appy.12408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Khatri IA, Iannaccone ST, Ilyas MS, et al. Epidemiology of epilepsy in Pakistan: review of literature. J Pak Med Assoc 2003;53:594–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yaqub F. Pakistan's drug problem. Lancet 2013;381:2153–4. 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61426-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Khan Qulain, Sanober A. "Jinn possession" and delirious mania in a Pakistani woman. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:219–20. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sadiq F, Khan Q. Barriers and challenges to mental health care in Pakistan. Pakistan J Neurol Sci 2021;16:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Javed A, Khan MS, Nasar A, et al. Mental healthcare in Pakistan. Taiwan J Psychiatry 2020;34:6. [Google Scholar]

- 70. World Health Organization . Mental health atlas. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rana W, Mukhtar S, Mukhtar S. Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;51:102080. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ashraf F, Zareen G, Nusrat A, et al. Correlates of psychological distress among Pakistani adults during the COVID-19 outbreak: parallel and serial mediation analyses. Front Psychol 2021;12:647821. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang C, Wang D, Abbas J, et al. Global financial crisis, smart lockdown strategies, and the COVID-19 spillover impacts: a global perspective implications from Southeast Asia. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:643783. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mukhtar S. Pakistanis’ mental health during the COVID-19. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;51:102127. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Salman M, Mustafa Z, Asif N, et al. Knowledge, attitude and preventive practices related to COVID-19 among health professionals of Punjab Province of Pakistan. J Infect Dev Ctries 2020;14:707–12. 10.3855/jidc.12878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Riaz M, Abid M, Bano Z. Psychological problems in general population during covid-19 pandemic in Pakistan: role of cognitive emotion regulation. Ann Med 2021;53:189–96. 10.1080/07853890.2020.1853216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ali DA, Ali IA, Sakharani K, et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among the general population of Karachi during COVID-19 pandemic and its associated factors. J Med 2022;23:36–41. 10.3329/jom.v23i1.57935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Muhammad Alfareed Zafar S, Junaid Tahir M, Malik M, et al. Awareness, anxiety, and depression in healthcare professionals, medical students, and general population of Pakistan during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross sectional online survey. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2020;34:131. 10.47176/mjiri.34.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Punjab Government . Provincial assembly of the Punjab, 2014. Available: http://papmis.pitb.gov.pk/uploads/bills/billpassed_2014_13.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 80. Tareen A, Tareen KI. Mental health law in Pakistan. BJPsych Int 2016;13:67–9. 10.1192/s2056474000001276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gilani AI, Gilani UI, Kasi PM, et al. Psychiatric health laws in Pakistan: from lunacy to mental health. PLoS Med 2005;2:1105–9. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Government of Pakistan . The mental health ordinance 2001. Available: http://punjablaws.gov.pk/laws/430a.html#:~:text=TheMentalHealthOrdinance2001&text=AnOrdinancetoconsolidateand,propertyandotherrelatedmatters [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 83. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa . The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Mental Health Act, 2017. Available: http://kpcode.kp.gov.pk/uploads/2017_17_THE_KHYBER_PAKHTUNKHWA_MENTAL_HEALTH_ACT_2017.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 84. Government of Sindh . Provincial assembly of Sindh notification, 2013. Available: http://www.pas.gov.pk/uploads/acts/SindhActNo.Lof2013.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 85. Government of Balochistan . Balochistan provincial assembly Secretariat, 2019. Available: https://pabalochistan.gov.pk/pab/pab/tables/alldocuments/actdocx/2019-10-30_16:45:35_5c0a1.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 86. Khyber Paktunkhwa . Health policy of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 2018. Available: http://healthkp.gov.pk/public/uploads/downloads-41.pdf [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 87. World Health Organization (WHO) . Depression, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression [Accessed 2 July 2022].

- 88. Gadit AA, Vahidy AA. Mental health morbidity pattern in Pakistan. J Coll Physicians Surg Pakistan 1999;9:362–5. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lu P, Li X, Lu L, et al. The psychological states of people after Wuhan eased the lockdown. PLoS One 2020;15:e0241173. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Torjesen I. Covid-19: mental health services must be boosted to deal with “tsunami” of cases after lockdown. BMJ 2020;369:m1994. 10.1136/bmj.m1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. BBC . Sinopharm: Chinese Covid vaccine gets who emergency approval, 2021. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-56967973 [Accessed 2 July 2022].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository.