Abstract

Introduction

Mobile exercise apps for smartphones have been used with intervention measures to increase physical activity. This study aimed to identify and evaluate the quality of fitness apps for smartphones that were used to increase the level of physical activity and improve the overall health of healthy adults.

Methods

The systematic review was performed in five electronic databases EMBASE, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Academic Research Premier e Cochrane Reviews, and Trials. The search terms were grouped into three categories according to the principles of population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes. The following includes examples of the group terms: population (healthy adults), intervention (smartphone apps), and outcomes (physical activity level).

Results

Of the 3924 potential articles, 74 were read for full-text analysis. Only seven studies were included in the review. The methodological evaluation of the studies and the apps’ quality showed that only one study and one app were evaluated with good quality. All studies used a type of application to improve the level of physical activity (measured by the number of daily steps), reporting an increase and improvement in some general health indices (calorie expenditure, weight, BMI) in healthy adults, regardless of frequency and duration of intervention and applications.

Conclusion

We cannot say that the use of smartphone applications improves the level of physical activity and general health. The low methodological quality of the studies and the possibility to evaluate the applications used (Mars Scale) due to the lack of technical standardization presented in the studies, despite the app used showing positive results in all studies.

Keywords: Mobile apps, smartphone, exercise, physical activity, mobile health

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 23% of the adult population is sedentary, and up to 5 million deaths per year could be prevented if the population were more active.1 The global cost of physical inactivity was estimated at $54 billion per year in direct health care in 2013, with $14 billion attributable to loss of productivity.1–3 Physical inactivity accounts for 1–3% of health care costs, excluding costs associated with mental health and musculoskeletal conditions.4,5 The entity relates a sedentary lifestyle to the absence of physical activity and considers an active adult individual to be one who practices moderate and vigorous exercise activity for a minimum weekly time of 150 to 300 minutes; according to the WHO “All physical activity is beneficial and can be performed as part of work, sport, and leisure, or transportation, but also through dancing, playing, and everyday household chores such as gardening and cleaning,” reinforcing the guidelines published in 2020 that any movement matters.1,2

As preventive measures, the WHO points out four directions: create active societies, which involve stimulating knowledge about the benefits of physical activity; create F spaces such as open parks; encourage stimulation programs in diversified environments such as home, school, and finally, promote active systems from political actions and training of professionals.1–5 In all these actions we can observe the stimulus to the individual's autonomy and the integration with new technologies in the search for improvement in their quality of life.4–6 However, Michie's Behaviour Change Taxonomy describes that effectivities interventions need to go beyond content to include mode and context of delivery beyond the competence of those delivering, which will have a greater impact on results.7

Such integration has gained strength from one of the most disruptive technological revolutions of our time, with the use of smartphones—the Smartphones and other smart wearable devices, which carry mobility in themselves, and constitute personal consultants through hundreds of apps of various utilities, which aim to facilitate access to information on topics of varied interest to their users.3,8,9 This growth in technology and connectivity has brought to daily routines more ease, agility and convenience so that we remotely solve almost everything with just one “click.”10,11 On the other hand, these changes cause the population to move less, so they become more sedentary and accumulate a large burden of diseases, consequences of physical inactivity.12–14 With this technological change, tools have also been created to solve this issue of physical inactivity through smartphone exercise apps.10,13–15

In 2012, the volume of apps downloaded on smartphones surpassed 40 billion, and the forecast is that this number will reach 300 billion.8 The fitness apps market alone grew from US$ 1.8 billion to US$ 2.2 billion between 2016 and 2017.8,9,12 These apps teach, encourage, and monitor self-practice of physical activity, without the need of a specific place or professional to practice exercise, so that the user has total freedom to choose the time, place, type of exercise, and time to perform the physical activity.14,15 Currently, there are thousands of mobile self-workout apps for Smartphones, which involve the most varied types of physical activities; they are easily accessible, many are free, and are available to anyone who has a Smartphone; however, despite being obtained (through downloads) from Smartphones, user compliance is none, low or falls into disuse in a short time of use.8,9,13–16

As demonstrated, despite the large growth in mobile exercise apps for smartphones and the emergence of research on interventions to increase physical activity levels, reduce sedentary behavior, and improve these users’ overall health and quality of life. The characteristics of exercise programs and user adherence strategies (motivation, competition, incentives, and behavior techniques) are presented in the application studies.

Study question: Do exercise apps help to change physical activity levels and improve the overall health of users? What are smartphone exercise apps described in the scientific literature for healthy individuals? What are the strategies used by these applications to deliver physical exercise programs?

The study aims to identify and evaluate smartphone physical exercise apps to improve physical activity levels and overall health. We will also describe and analyze the types of strategies, interventions, and technological models used by these apps. And demonstrate the results obtained using technology in the physical activity level and general health.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review and its procedures were planned, conducted, and reported according to the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.17 The review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews.18

Search strategy

Five databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Academic Research Premier, and Cochrane Reviews and Trials) were systematically searched to identify relevant studies. Boolean operators were used to expand, exclude, or join keywords in the search using the terms “AND,” “OR,” and “NOT.” Studies in more than one database were classified as duplicates and counted only once.

The search terms were grouped into three categories according to the principles of population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes. The following includes examples of the group terms: population (healthy adults), intervention (smartphone apps), and outcomes (physical activity level). The groups of words used for search strategies can be seen in Appendix 1. The first search was started in February 2020, and the last search was completed on 13 July 2022.

Eligibility of studies

Inclusion criteria

Randomized and nonrandomized controlled trial studies from the last 10 years of publication without language restriction were included. Searches were updated before final analyses. Studies were selected that used smartphone application tools for physical activity and to improve general health in healthy adults. Individuals who used the technology included in the studies must be healthy, sexes female or male, and be 18 or more years of age.

Exclusion criteria

The excluded studies comprised the following criteria: individuals with any disease or comorbidity, children or the elderly, the use of non-applications of Smartphones (Desktop (computer), SMS sending (Short Message Service)), and those without a direct relationship to the theme verified by reading the title and abstract.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of interest were physical activity level, general health, quality of life, adhesion strategies and encouragement of physical activity, and the quality rate of the apps used.

Regarding the level of physical activity, the following information was considered relevant: duration of physical activity programs; frequency (weeks, days, hours, and minutes); metabolic equivalent of task, to measure the caloric expenditure during the exercises; and a number of daily steps, which may have been assessed through self-report, questionnaires, and data analysis such as pedometer, accelerometer, maximum oxygen consumption, field tests such as the 6-minute walk test, walk test, and submaximal fitness tests.19,20

The effects on improving individuals’ health were evaluated through the physical results: weight, height, body mass index (BMI), abdominal circumference, and eating habits.21 Changes in eating habits resulting in better health conditions were analyzed through daily, weekly, and monthly dietary intake that can be self-reported or through a questionnaire.22 Relevant quality of life data was analyzed through studies that present generic and specific quality of life questionnaires.21,23

The authors considered strategies for exercise adhesion or improvement through intervention designs based on behavior change theories such as self-determination theory, social cognitive theory, and transtheoretical model among others.21,24

The quality of the self-exercise apps used was evaluated through the identification of the app, nomenclature, technological model, and description of the application, following the criteria of the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS).25

Study evaluation

Duplicates were removed, then two independent reviewers (AN and RRBTM) analyzed the titles and abstracts of the studies. Eligible articles (full text) were electronically formatted and analyzed according to the eligibility criteria. Included studies were assessed for risk of bias (high, low, or unclear) using Cochrane Collaboration criteria.25 In cases where consensus was not reached, a third reviewer was consulted (RSP). Regarding the classification of concerning studies with,expect to “selective reporting,” the judgment criteria provided by the Cochrane Collaboration were followed. The results of the selection were exported to the ENDNOTE® X6 software.

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the studies

The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized clinical trials (the Cochrane “Risk of Bias” Tool 2—RoB 2.0)26 was used for quality assessment of the included studies. RoB 2.0 provides a framework for considering the risk of bias in the findings of any trial. It is designed hierarchically: answers to flagging questions elicit what has happened and provide the basis for domain-level judgments about the risk of bias.26

The tool is structured into five domains through which bias can be introduced into the outcome. These were identified based on empirical evidence and theoretical considerations. Because the domains cover all types of biases that can affect the results of randomized clinical trials, each one is mandatory, and no other domain should be added. The five domains for individually randomized trials (including cross-over trials) are: (1) bias arising from the randomization process; (2) bias due to deviations from intended interventions; (3) bias due to missing outcome data; (4) bias in outcome measurement; and (5) bias in the selection of the reported outcome.26

The inclusion of signaling questions within each bias domain is a key feature of RoB 2. Signaling questions aim to elicit information relevant to a bias risk assessment. They aim to be reasonably factual in nature. The answers to these questions feed into algorithms that we have developed to guide users of the tool to judgments about the risk of bias. The response options for the signaling questions are: (1) Yes; (2) Probably Yes; (3) Probably Not; (4) No; and (5) No information.26

The tool includes algorithms that map the answers to the signaling questions into a proposed bias risk judgment for each domain. The possible risk of bias judgments are (1) Low risk of bias: The study is considered low risk of bias for all domains for this outcome, (2) Some concerns: The study is judged to raise some concerns in at least one domain for this outcome, but not to be at high risk of bias for any domain, (3) High risk of bias: The study is judged to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain for this outcome Or the study is judged to have some concerns for several domains in a way that substantially reduces confidence in the outcome. The word “judgment” is important in assessing the risk of bias. In particular, algorithms provide proposed judgments, but users should check them and change them if they feel it is appropriate.26

Methodological quality assessment of apps

App quality was assessed using the MARS25 which is composed of 23 items grouped into six categories: 1 category addresses the rating of apps (including target age range, technical aspects included, the focus of the app, and strategies used), 4 categories relate to app characteristics (engagement, functionality, aesthetics, quality and credibility of information), and 1 category addresses the subject app quality. All items are measured on a 5-point scale (1 = inadequate to 5 = excellent). A score for each domain is calculated as the average of the items in that domain; an overall score is calculated as an average across the domains. The app of the quality assessment will be conducted independently by two reviewers (all authors contributed). Disagreement between the two reviewers by 1 point was resolved by taking the average of the two assessments. Disagreement by more than 1 point was resolved by discussion and/or consensus with a third reviewer.25

Data extraction

The authors worked independently, using the standardized form adapted from the Cochrane Collaboration model27 for data extraction, considering: (1) aspects of the study population profile; (2) intervention used with the use of apps: types of exercise, duration; weeks, days, hours, minutes, and daily steps; (3) measurement of physical activity level: accelerometers, physical activity monitoring and step counter; (4) follow up; (5) loss of follow up; (6) sedentary lifestyle variables assessed; (7) general health improvement, such as physical assessment, weight, height, BMI, abdominal circumference, and eating habits (8) apps used and their motivation and adherence strategies, such as authors’ reports through the intervention designs based on behavior change theories such as self-determination theory, social cognitive theory and (9) results obtained.

Results

Study features and methodological quality

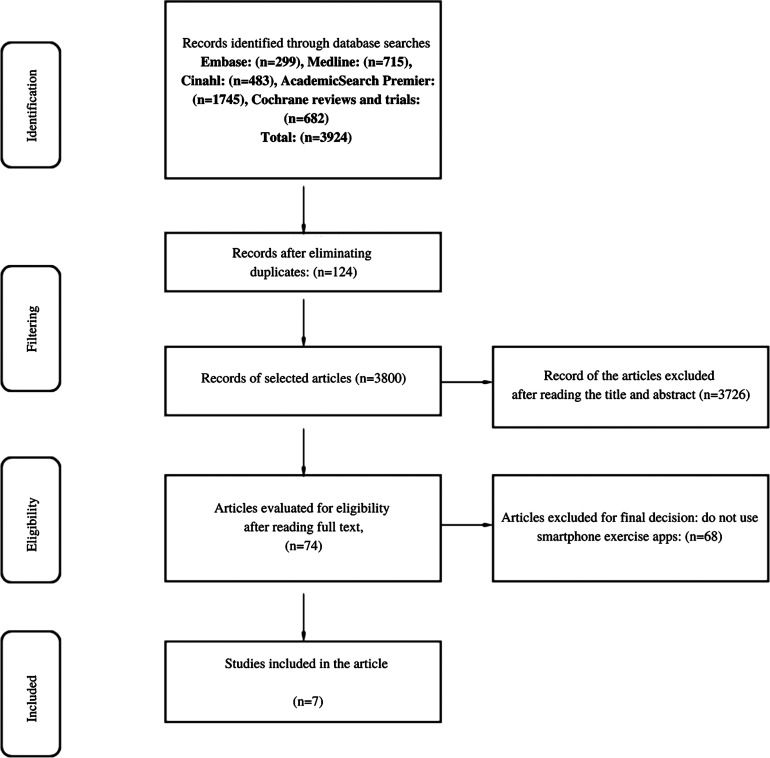

From the searches performed with the established criteria, 3924 potentially eligible articles were located, where 124 were duplicates, leaving 3800 articles. After reading all titles and abstracts respecting the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 74 studies were selected for analysis by full text, leaving seven for data extraction, presented below in the detailed flowchart of the systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review process.

All seven included studies were randomized controlled trials; after being evaluated for methodological quality, only one study was rated as good (King et al., 2016),28 three studies were rated with some concern (Balk-Møller et al., 2013,29 Fanning et al., 2016,28 Recio-Rodriguez et al., 201630) and three as weak (Glynn et al., 2014,31 Hanque et al., 2020,33 Harries et al., 201632).

Participants

The sample of the studies ranged from 84 to 833 participants. More than 1800 individuals were evaluated in the seven included studies, in which the mean age was 42 years. The study by Harris et al. (2016),31 included only male individuals. The studies by Balk-Møller et al. (2013)28 and Recio-Rodriguez et al. (2016)29 included only females. According to the year of publication of the seven studies, four were published in 2016 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of physical exercise interventions and outcome measures.

| Author/year/country | Participants | Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | Frequency/duration | Physical activity level (results) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King et al. 201627—EUA | N = 95, both sexes, aged 45 or older—divided into four groups. | Social Group social support for behavior change was emphasized through on-screen avatars that reflected the current level of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Interaction between participants. | Effective group used a bird-shaped avatar to demonstrate how active or sedentary the user was throughout the day. | Analytic Group used personalized and quantitative goal setting, behavioral feedback, informational cues that promote behavior change, and problem-solving strategies aimed at barriers to behavior change. problem-solving strategies aimed at barriers to behavior change. |

Control (monitoring) | 8 Weeks/minimum 30 minutes per day. | Results indicate significant improvements through the apps about increased physical activity and changes in sedentary behavior. P-values for differences between arms = 0.04–0.005. Social app vs. control: d = 1.05, CI = 0.44, 1.67; social app vs. affected app: d = 0.89, CI = 0.27, 1.51; social app vs. analytic app: d = 0.89, CI = 0.27, 1.51 |

Users who used social apps (Group B) showed a significantly higher increase in moderate to vigorous activity levels than users of the other apps |

| Fanning et al. 201628—EUA | N = 116, both sexes, aged 30–54 years—divided into four groups. | Monitoring, instant feedback, bi-weekly feedback, knowledge, guided goal setting, points-based, and feedback. | Monitoring, instant feedback, bi-weekly feedback, knowledge and guide goal setting. | Monitoring, instant feedback, bi-weekly feedback, knowledge, points-based, and comments. | Monitoring, instant feedback, bi-weekly feedback, knowledge | 12 Weeks/minimum of 30 minutes per day—5 × a week of aerobic activity and 2x a week of strength training | The study demonstrated a significant increase in the level of moderately vigorous physical activity during the intervention MVPA (min) (baseline:34.88 (1.62)) Follow-up :46.77 (1.65) 95% CI: 0.42, 0.97 | All individuals increased moderately vigorous physical activity by more than 11 minute daily. Those with point-based feedback demonstrated even higher levels of moderately vigorous physical activity and more favorable psychosocial and app use outcomes across the intervention. |

| Balk-Møller et al. 201329—Denmark | N = 566 both sexes, average age 47 years, divided into two groups. Note: Only the results of the women were shown. | Intervention through the SoSu-life application. | Control (No intervention). | NR | NR | 16 to 38 weeks/not reported | App showed a greater reduction in body weight, fat percentage, and abdominal circumference in healthcare staff

Body weight (kg): SoSu-life −1.44 (0.26) Control Mean (SE) 0.10 (0.19) (95% CI) −1.54 (−2.18 to −0.90) P-value: <.001 Body fat percentage : SoSu-life : −0.70 (0.21) Control Mean (SE: 0.04 (0.16) (95% CI): −0.81 (−1.35 to −0.27) P-value: 003 Waist Circumference (cm) SoSu-life : −1.40 (0.47) Control Mean (S: −0.51 (0.37) (95% CI) : −1.05 (−2.26 to 0.16) P-value: .09 |

The web-based and app-based tool SoSu-life had a modest but beneficial effect on body weight and body fat percentage compared to the control group. |

| Recio-Rodriguez et al. 201630—Spain | N = 833 both sexes, average age 54 years, divided into two groups. Note: Only the results of the women were shown. | Participants received training in the use of an app to promote the Mediterranean diet and increase PA | Intervention consisted of standardized counseling on PA and Mediterranean diet, with delivery of printed support material (leaflet) at the session. | NR | NR | 3 months/7 days per week | An increase in PA was observed in both groups (although higher in app + counseling). Intervention group (mean 29, 95% CI 5–53 minutes/week; P = .02), Counseling group only (mean 17.4, 95% CI − 18 to 53 minutes/week; P = .38) |

Leisure AFMV increased more in the app + counseling than in the counseling only group, although no difference was found when comparing the increase between the two groups. |

| Glynn et al. 201431—Ireland | N = 90 of both sexes, average age 44 years (mostly women) | Participants received physical activity goals, information about the benefits of exercise, and information about how to use the app to achieve the goal | Participants received only physical activity goals and information about the benefits of exercise (they did not receive information on how to use the goal functions of the APP). | NR | NR | 8 weeks/30 minutes of walking per day (10,000 steps). | It was found that using the app significantly increases the level of physical activity and, if continued, should result in long-term health benefits. Step count: Control group: −386 (3281 steps) Intervention group: 1631 (3842 Steps) P-value: 0.025 |

A simple smartphone app significantly increased (for both groups) physical activity during 8 weeks in a primary health care facility population |

| Harries et al. 201632—United Kingdom | N = 165 males, aged between 18 and 40 years. | Control group (no feedback and no access to the active interelements of the App. | Individual feedback group (feedback on the participant and own steps) | Social feedback group (feedback on the participant, own steps and the average steps taken by other people in their group). | NR | 8 Weeks/application goals | Always-on smartphone apps that provide step counting can increase physical activity in young to middle-aged men. Step counting: Individual feedback group 60% higher ( = 0.474, 95% CI = 0.166–0.782) Social feedback group 69% Higher ( = 0.526, 95% CI = 0.212 − 0.840). |

Always-on smartphone apps that provide step counting can increase physical activity in young to early middle-aged men, but providing social feedback has no apparent incremental impact. |

| Hanque et al. 202033 Multicentric Europe | N = 84, both genders, with a mean age of 39 years. (Only 27 participants completed the study). | Participants was done using the iGO application. (Only 20 participants completedthe study). | The control group was conducted using a paper diary. (Only seven participants completed the study). | NR | NR | 4 weeks/1000 stages of 10 minutes | The mHealth application supported users to increase their physical activity in the workplace. Amount of steps: Intervention group: (mean):6.15 Control group (mean):4.30 P = 0.033 |

This study demonstrates how even a simple mHealth app can help employees increase their physical activity at work. |

NR: Not Reported.

Characteristics, strategies, and measurement type of the apps

Seven studies used smartphone apps to increase participants’ physical activity levels and general health. Only four studies (Balk-Møller et al., 2013,29 Glynn et al., 2014,31 Harries et al., 2016,32 and Haque et al., 2020)33 listed the apps used; SoSu-life, Accupedo-Pro Pedometer, bActiveApp and iGO App respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of smartphone app to physical exercise.

| Authors | App | Measurement for physical activity level | Technical description of the application | Nomenclature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| King et al.27 | Three apps (no name): A physical activity/sedentary behavior app. | Smartphone accelerometer (android system) | There was no description of the application's name—only that the android system used it | SedentaryBehaviorApp |

| Fanning et al.28 | Four (unnamed) entry-level apps containing four features (monitoring, instant feedback, weekly biofeedback, knowledge) | Actigraph Accelerometers (Actigraph, Pensacola, FL;Model GT1 M) | There was no description of the name of the four apps—only that it was used by android or IOS system | Self-Monitoring App |

| Balk-Møller et al.29 | SoSu-life is a web and app-based workplace health promotion tool to aid weight loss, social well-being, and health professionals. The basic features of the tools were self-reporting of diet and exercise, personalized feedback, suggestions for activities and programs, and practical tips and tricks. | Self-report with calculation made through calorie measurement | Tool developed specifically for this purpose. There is no platform (Android or IOS)—a search was performed, without success in finding the application. | Intervention Apps |

| Recio-Rodriguez et al.30 | App (no name) easy-to-use interface for recording food and exercise. | Smartphone Accelerometer and AccelerometerActiGraph GT3X (ActiGraph, Halimar, FL, USA). For activities without the device | The app was developed by software engineers in collaboration with nutritionists and PA specialists, with an easy-to-use interface for recording food and exercise. | App to increase physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet/app to standard counseling on increasing physical activity (PA) |

| Glynn et al.31 | The Accupedo-Pro Pedometer App (available at www.accupedo.com) | Smartphone App Pedometer | The Accupedo-Pro Pedometer App (available at www.accupedo.com) was chosen for the study because it achieved the highest score during a selection process using the desired already established criteria for promoting physical activity smartphone apps | App: to increase physical activity in primary care |

| Harries et al.32 | App: bActiveApp = Monitoring app (number of steps, calories, and distance) | App Accelerometer | To remove the effects of variability between different hardware and software platforms, the app was installed on identical phones, and these were provided to the pants participants, who had to agree to put their Subscriber Identity Module (SIM) cards into the study phones and use them as their primary cell phones during the study. | App that recorded steps continuously, without the need for user activation. Smartphone app and increased physical activity |

| Haque et al.33 | Persuasive mHealth app called iGO | Smartphone accelerometer sensor (Samsung®) | Persuasive and gamified mHealth app was developed to encourage employees to walk more often and break up long periods of sitting during working hours | App: to increase physical activity through game elements and motivation results (exercise, walking, and weight management) |

The general characteristics of the apps and strategies used in the seven studies analyzed were monitoring28 recording (steps, calories, distance walked, exercise diary, and diet)29,30,33 feedback,28 biofeedback,28 individual and collective goals,27 socializing,27,33 where the goal was to increase the level of physical activity,27,28,30 weight loss,29 and change sedentary behavior.27

The level of physical activity was measured using an accelerometer,27,28,30,32,33 pedometer)31 and self-report.29 Regarding the physical activity implemented in the studies, these were only guided and recommended through established goals and device reminders. There was no guided exercise protocol through the app (Table 2).

Quality assessment of apps

Of the seven studies evaluated, only the study by Glynn et al.31 contained the information necessary to assess the app using the MARS scale; the other six studies did not include even the basic information for the evaluation, as shown in Table 3. The app used by Glynn et al.31 obtained the following mean scores Engagement (4.6), Functionality (4.75), Aesthetics (5.0), and Information (4.14), leading to an app quality score of 4.6 on a scale of 1 to 5, demonstrating that the app used is of good quality.

Table 3.

Evaluation of apps by the MARS scale.

| Authors | App name | Rating this version | Developer | N ratings this version | Version | Last update | Cost–basic version | Platform | Brief description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King et al.27 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Android | Three apps with an analytical, social and affective framework |

| Fanning et al.28 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Self-Monitoring App (monitoring, feedback, education) |

| Balk-Møller et al.29 | SoSu-life | NR | Mobile fitness | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | SoSu-life, a tool for health promotion in the workplace |

| Recio-Rodriguez et al.30 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | App to standard advice on increasing physical activity |

| Glynn et al.31 | App Accupedo-Pedometer | NR | Corusen LLC | 25 | 4.3.1 | 2022 | Free/Pro Version—US$9.90/year | Android/IOS | It automatically retrains your walk |

| Harries et al.32 | App: b Active App | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | App that continuously logs steps |

| Haque et al.33 | Aplicativo iGO | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | mHealth app for physical activity motivation |

Duration of interventions and frequency of physical activity sessions

The duration of the interventions in the seven studies ranged between 4 and 12 weeks, with 8 weeks being the time of the interventions in three of the studies.27,31,32 The frequency and duration of each physical activity session varied: three studies27,28,31 used a period of 30 minutes a day, another study duration was of 10 minutes a day, one study 30 used a duration of seven days a week and two others.29 One study 33 did not specify the duration only reported as goals of the application32 (Table 1). Despite this difference in the intervention time duration of the physical activity sessions, all studies increased physical activity level after using apps.

Characteristics and effects of interventions on physical activity level

All seven studies demonstrated increased participants’ physical activity levels with smartphone apps (Table 1). The study by King et al. (2016)27 reported a significant increase in physical activity levels and overall health within eight weeks using an app with social interaction strategies compared to the other three study arms. On the other hand, in the study by Fanning et al. (2016),28 had a significant increase of more than 11 minutes per day of moderately vigorous physical activity during the 12-week intervention using apps that combined monitoring, feedback, and education. Balk-Møllere et al., 201329 demonstrated a healthier lifestyle with a reduction in body weight, fat percentage, and abdominal circumference when compared to the control group in a 38-week program using a web-based app with a competition strategy between participants. Recio-Rodriguez et al. (2016)30 obtained an increase in physical activity level in both groups (intervention by standard counseling app to increase physical activity level and counseling only) when measured by questionnaire. Still, there was no significant difference between the groups. After 3 months with accelerometer measurement, there was a reduction in physical activity level in both groups. Glynn et al., 2014 31 utilized an app to increase physical activity level with detailed instructions on how to achieve the goals, for 8 weeks, demonstrating a significant improvement of 1029 steps per day in favor of the intervention. Harries et al. (2016)32 used a step counter app with feedback goal-stimulating strategies. And found that after 8 weeks of intervention the individual feedback group was greater than the social feedback group, however, this difference between groups was not statistically significant. Hanque et al. (2020)33 demonstrated that in four months an easy-to-use app with simple participant stimulation through messages and daily goals helped employees increase physical activity at work by raising their level of walking (compared to using a paper diary).

Effects of interventions on general health and quality of life

Three studies27,32,33 demonstrated some type of gain, even if indirect, in the general health and quality of life of the participants. King et al. (2016)27 reported the post-intervention satisfaction of participants who used the apps, in which they helped to remind them (71%), motivate them (69%), and reduce time-taking throughout the day (74%,). Balk-Møllere et al. (2013)29 showed a greater reduction in body weight (−1.01kg, P = .03), fat percentage (−0.8%, P = .03) and abdominal circumference (−1.8 cm, P = .007) when compared to the control group. The study by Harries et al. (2016)32 also obtained indirect gains in relation to physical activity and quality of life in the intervention group with a 60% to 69% gain over the control group in the number of daily steps Haque et al. (2020)33 found a potential outcome for overall health and quality of life showing a trend of weight loss in the intervention group.

Discussion

The results of this review showed evidence of the benefit of using apps to increase the level of physical activity and overall health of healthy adults, regardless of the time and frequency of the intervention, regardless of the type of app.27–33 Although only one study of the seven included in the review showed good methodological quality, all of them reported an improvement in the level of physical activity in their results.27 These findings demonstrate that only the stimulus of the guided practice of physical activity, which was the main objective of the apps, already brings gains for the health of individuals.28–33 However, regarding the methodological quality of the seven studies, only one study was classified as good (King et al. 2016),27 and three studies28–30 were rated as having some concern of bias (out of five criteria evaluated, three raised concern) and three studies31–33 were rated as weak (out of five criteria evaluated, four were rated as low) such as Risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions (effect of assignment to intervention), Effect of adhering to intervention, Missing outcome data, Risk of bias in the measurement of the outcome, demonstrating that although the studies found satisfactory results regarding the increased level of physical activity with the use of apps, we cannot state that these are reliable evidence.

The seven studies reported varied duration and frequency of interventions, with the duration of 8 weeks27,31,32 and the frequency of 30 minutes daily27,28,31 being the doses reported in three studies. Studies34 have shown that after 12 weeks of duration, interventions using physical activity apps begin to fall into disuse. This may explain the success rate of the interventions used in the seven studies, in which most used a duration of 8 weeks.27,31,32 The duration of the interventions in these three studies is in accordance with the minutes per week of exercise for a person to be considered active, according to the World Health Organization (150 to 300 minutes per week).1,2

Despite the variations in the duration and frequency of interventions used, all the studies increased the level of physical activity regardless of the app. Still, the lack of basic, technical, and detailed information on the apps, such as name, manufacturer, platform used, and operating system, made the technical evaluation of the apps unfeasible, making it difficult to reproduce the studies. Physical activity was only monitored and stimulated in the interventions performed, and there was no exercise protocol performed directly with the participants, for example, apps that use guided and exemplified self-exercise, through real or virtual video-classes (performed by an “avatar”) simulating the real movements of physical activity, guided by a standardized exercise protocol.

Despite the satisfactory results of the studies, some primordial points regarding the app used must be reviewed and understood so that it is possible to improve and implement new strategies for using these apps. For instance, the lack of standardization regarding the nomenclature used in studies performed using smartphone apps, a fact demonstrated in our search where only four studies29,31–33 listed the name of the apps used, but when these apps were searched in the platforms, only one application30 was available for the general public, thus making the clinical reproduction of these studies unfeasible. In addition, app's name, basic technical information such as version, version classification, developer, last update, cost of the version, the platform used, and brief description25 should be demonstrated in studies that use this technology. Based on our results, we suggest that the physical activity apps used in the studies contain the basic items of the MARS25 scale, which evaluates the apps.

These facts reinforce the importance of this study, in which we sought to identify interventions that used apps to increase physical activity when self-management of health is so necessary and important. Moreover, with the COVID-19 Pandemic, lockdown, and social distancing measures, people started exercising at home, and there was a large increase in the use of self-management apps, which teach and practically guide the user to perform physical activities safely and more effectively.35 With a greater demand for technology and advances and innovations at a faster speed than expected, there has been a change in the laws and regulations for distance health care (Virtual), medical, psychological, physiotherapeutic, and physical education services, showing that the use of technology is a worldwide trend, with no turning back.

The study limitations were that of the seven studies included, six of them had a methodological character and we were not able to evaluate the quality of the applications (MARS scale) due to the lack of technical standardization of the seven studies. Therefore, it was not possible to say in a concrete way that smartphone applications increase the physical activity level and improve the general health of healthy adults. Another point is the use of applications in these studies, which are characterized only by the monitoring of individuals and not by the application of physical exercises in a guided way. Thus, new studies should be designed with better methodological quality and standardization of technical information about the applications used and therefore carry out a quality assessment. A meta-analysis was not considered for this study, after the evaluations of the delivery of physical exercise interventions by apps. This is because there was a low quality of evidence and poor quality of application components.

Future studies should be conducted for apps that use other intervention strategies such as guided self-exercise since it is a new model of practice, promotion, and guidance of physical activity following the current technology. Studies that used smartphone apps to promote physical activity demonstrated improvement in physical activity levels and general health in healthy adults. Regarding the evaluation of the applications used, they did not have technical standardization points on how to be described in the studies, so that we can evaluate their usability and feasibility in day-to-day practice.

Conclusion

Apps used to increase the level of physical activity in healthy adults demonstrated gains after 4 weeks of intervention, with secondary improvement in quality of life through satisfaction results, body weight reduction, and increased caloric expenditure, but there is little standardization of apps and technology used, which makes it difficult for the user to understand which app and intervention.

Appendix 1

Search strategy

Five databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Academic Research Premier, and Cochrane Reviews and Trials) were systematically searched to identify relevant studies. Boolean operators were used to expand, exclude or join keywords in the search using the terms “AND,” “OR,” and “NOT.” Studies that were found in more than one database were classified as duplicates and counted only once. The search terms were grouped into three categories according to the principles of population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes. The following includes examples of the group terms: population (healthy adults), intervention (smartphone apps), and outcomes (physical activity level). The groups of terms used for search strategies can be seen in Table 1. The first search was started in February 2020 and the last search was completed on 13 July 2022.

Table A1.

Search procedure, key topics, and terms.

| Topic | Basic search scheme |

| Population | Adults* OR healthy adults* OR of age* OR older people* |

| Intervention | Smartphone* OR smartphone app* OR smartphone applications* OR telephone* OR telephone app* OR telephone applications* OR cell phone*OR cell phone app* OR cell phone applications* OR phone * OR phone app* OR phone applications*OR tablet* OR mobile* OR mobile application* OR mobile applications* OR mobile app* OR mobile health* OR internet* |

| Outcomes | Activity * activity level* OR physical exercise* OR exercise* OR physical mobility* OR movement* OR muscle strength* OR bodybuilding* OR sedentary behavior* OR sedentary lifestyle* OR practice of physical activity*) |

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: Conceptualization: AN and RSP. Formal analysis: AN and RRBTM. Writing—original draft: AN and RSP. Writing—review and editing: AN, RRBTM, BCB, and RSP. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (grant number 001).

ORCID iD: Rosimeire Simprini Padula https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0903-770X

References

- 1.WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566045/ (accessed Dec 102020).

- 2.WHO. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf (accessed Feb 1 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2016; 388: 1311–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sagner M, Katz D, Egger G, et al. Lifestyle medicine potential for reversing a world of chronic disease epidemics: from cell to community. Int J Clin Pract 2014; 68: 1289–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garry JE, Andrew FB, Stephan RR. The emergence of the lifestyle medicine as a structure approach for management of chronic disease. MJA – The Medical Journal of Australia 2009; 190: 143–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreira MWL, Rodrigues JJPC, Korotaev V, et al. A comprehensive review on smart decision support systems for health care. IEEE Syst J 2019; 13: 3536–3545. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston Met al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013; 46: 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lymberis A, Dittmar A. Advanced wearable health systems and applications: research and development efforts in the European Union. IEEE Eng Med BiolMag 2007; 26: 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocha TAH, Fachini LA, Thumé E, et al. Mobile health: new perspectives for healthcare provision. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2016; 5: 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tibes CMS, Dias JD, Zem-Mascarenhas SH. Mobile applications developed for the health sector in Brazil: an integrative literature review. RevistaMineira de Enfermagem 2014; 18: 471–478. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee M, Lee SH, Kim T, et al. Feasibility of a smartphone-based exercise program for office workers with neck pain: an individualized approach using a self-classification algorithm. ArchPhysMedRehabil 2017; 98: 80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lunde P, Nilsson BB, Bergland A, et al. The effectiveness of smartphone apps for lifestyle improvement in noncommunicable diseases: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong FY. Influence of pokémon go on physical activity levels of university players: a cross-sectional study. Int J Health Geogr 2017; 16: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Ortiz L, Recio-Rodriguez JI, Agudo-Conde C, et al. Long-term effectiveness of a smartphone app for improving healthy lifestyles in general population in primary care: randomized controlled trial (evident II study). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018; 6: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehra S, Visser B, Dadema T, et al. Translating behavior change principles into a blended exercise intervention for older adults: design study. JMIR Res Protoc 2018; 7: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mascarenhas MN, Chan JM, Vittinghoff E, et al. Increasing physical activity in mothers using video exercise groups and exercise mobile apps: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta- Analyses (PRISMA). PRISMA checklist; 2018, http://prisma-statement.org/ (accessedFeb 10 2020).

- 18.International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO). National Institute for Health Research; 2018, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed Feb 10 2020).

- 19.Bardus M, van Beurden SB, Smith JR, et al. A review and content analysis of engagement, functionality, aesthetics, information quality, and change techniques in the most popular commercial apps for weight management. Int J BehavNutrPhysAct 2016; 13: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tudor-Locke C, Han H, Aguiar EJ, et al. How fast is fast enough? Walking cadence (steps/min) as a practical estimate of intensity in adults: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med 2018; 52: 776–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J BehavNutr Phys Act 2016; 13: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Su C, Ouyang YF, et al. Secular trends in sedentary behaviors and associations with weight indicators among Chinese reproductive-age women from 2004 to 2015: findings from the China health and nutrition survey. International Journal of Obesity 2020; 44: 2267–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rollo S, Antsyginaa O, Mark S, et al. The whole day matters: understanding 24-h movement guideline adherence and relationships with health indicators across the lifespan. J Sport Health Sci 2020; 9: 493–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oftedal S, Vandelanotte C, Duncan MJ. Patterns of diet, physical activity, sitting and sleep are associated with socio-demographic, behavioural, and health-risk indicators in adults. Int J Environ Res PublicHealth 2019; 16: 2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015; 3: e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J 2019; 366: l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cochrane Community. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2018. RevMan 5,http://community.cochrane.org/help/tools-and-software/revman-5 (accessed Feb 152020).

- 28.King AC, Hekler EB, Grieco LA, et al. Effects of three motivationally targeted mobile device applications on initial physical activity and sedentary behavior change in midlife and older adults: a randomized trial. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0156370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fanning J, Roberts S, Hillman CH, et al. A smartphone “app"-delivered randomized factorial trial targeting physical activity in adults. Behav Med 2017; 40: 712–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balk-Møller NC, Poulsen SK, Larsen TM. Effect of a nine-month web- and app-based workplace intervention to promote healthy lifestyle and weight loss for employees in the social welfare and health care sector: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Recio-Rodriguez JI, Agudo-Conde C, Martin-Cantera C, et al. Short-term effectiveness of a mobile phone app for increasing physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet in primary care: a randomized controlled trial (EVIDENT II study). J Med Internet Res 2016; 18: e331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glynn LG, Hayes PS, Casey M, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application to promote physical activity in primary care: the SMART MOVE randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 2014; 64: e384–e391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harries T, Eslambolchilar P, Rettie R, et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone app inincreasing physical activity amongst male adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haque S, Kangas M, Jämsä T. A persuasive mHealth behavioral change intervention for promoting physical activity in the workplace: feasibility randomized controlled trial. JMIR Form Res 2020; 4: e15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Northey JM, Cherbuin N, Pumpa KLet al. et al. Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2018; 52: 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.George G, Lakhani KR, Puranam P. What has changed? The impact of COVID pandemic on the technology and innovation management research agenda. Journal of Management Studies. Research Collection Lee Kong Chian School of Business 2020; 57: 1754–1758. [Google Scholar]