Abstract

Introduction: Mass casualty incidents (MCIs) have a profound impact on health care systems worldwide. Following recent incidents within the United Kingdom (UK), notably terrorist attacks in Manchester and the Grenfell Tower fire in London, there has been a renewed interest in how the UK would cope with a burn MCI. A Burns Incidence Response Team (BIRT) is a new development incorporated into the Burn Annex of the NHS England National Concept of Operation for Managing Mass Casualties. It is a mobile advice team of healthcare professionals with burns expertise who can support the subsequent management of an MCI, and triage effectively. This review assesses the response to disasters worldwide, detailing national structure, and in particular the involvement of burn specialist teams. This review aims to highlight the roles of burns specialists, and their role within the UK. Method: A review of Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, UK government reports, annexes and textbooks was conducted. Results: A search resulted in 826 sources; 42 articles were included in this review, with 9 additional sources. BIRTs are described in the NHS Guideline Concept of Operations for the Management of Mass Casualties: Burns Annex, published September 2020. Conclusions: The implementation of a national burn response plan is a necessary step forward for effective management of these continuing MCIs. The available literature supports the need for preparation and organized response with a centralized control. Increased awareness and understanding of the role of BIRTs is important and highlights the need for specialist input in the long and short term. Factors which may affect the implementation of BIRT’s need to be explored in further detail.

Keywords: Burns response teams, mass casualty incidents, burns disaster

Introduction

Mass casualty incidents (MCIs) can have a large impact upon healthcare systems worldwide. Following recent incidents within the United Kingdom (UK), notably the terrorist attacks in Manchester, and the Grenfell Tower fire in London, there has been a renewed interest in how the UK Emergency and Health Care Systems would cope in the event of an MCI. The World Health Organisation Emergency Medical Team (WHO EMT) has been a leader in the global improvement of emergency response [1]. Every trauma hospital will have a major Incident plan in place when the number, type or complexity of casualties exceeds day to day functioning. An MCI exceeds major incident responses, which “must be augmented with extraordinary measures” [2].

In the UK, burns services are subdivided according to National Burn Care Guidelines into Centres, Units and Facilities [3,4]. There is a relative scarcity of burn resources; this is particularly notable for higher tertiary care such as level three intensive care beds, and paediatric resources. Recent fires within the UK and Europe have highlighted the need for effective planning. Lack of specialist input in the acute presentation can have a profound impact on patient outcome, and small numbers of patients can easily overwhelm the limited burns resources available. A national plan has been put in place covering emergency planning teams with a section dedicated for burns patients. Successful triage of patients may result in better or more effective management and improved allocation of these resources [3].

Throughout the UK there are 30 hospitals with burns services: 13 burns centres, 10 burns units and seven burns facilities. Some of these specialise in paediatric or adult burn care with just under half specialising in both. Only 57% of burns services are co-located within a major trauma centre [3]. Within these hospitals Emergency Preparedness Resilience and Response (EPRR) burns major incident plans aim to provide maximum beds to manage critically unwell burns patients in a major incident [2].

A Burns Incidence Response Team (BIRT) is a development incorporated into the Burn Annex of the NHS England National Concept of Operation for Managing Mass Casualties [3]. It is a mobile advice team of healthcare professionals with burns expertise who can support the subsequent management of an MCI, and triage effectively.

The aims of this review are to assess the response to burn disasters worldwide, describe national structure and the involvement of burn specialist teams. Furthermore, this review will highlight the role of burn specialists and their role in the UK.

Method

A literature search of PubMed, Embase and Web of Science was conducted by author L.A, in January 2022 using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [5]. Resources outside of the databases were considered, and included government literature, burns society and association literature, annexes, textbooks (Advanced Trauma Life Support) and the global terrorism database.

The search terms used were “burn AND disaster preparedness”, “burn AND disaster planning”, “mass casualty AND triage AND burn”, “mass casualty AND burn”, “burn incident response team”, “burn AND disaster and response” and “UK mass casualty incident”.

No date restrictions were set. Articles were limited to those available in the English language. The study included articles which contained information relevant to national, regional, or local organisation of burn MCIs and specialised burn clinical teams. Articles were excluded if they predominantly covered detailed inpatient management, or single hospital in-house experiences. Articles were excluded if they did not include information pertaining to national, regional, or local management of a burn MCI or a burn clinical team. Discrepancies in articles for inclusion were reviewed by a second independent reviewer (Author K.A). The authors have carried out a narrative synthesis of the literature.

Results

The database search yielded 826 articles. Following preliminary screening of titles and abstracts 188 articles were subjected to further scrutiny. A total of 42 articles were included in this review, consisting of retrospective reviews and reports, mixed method studies, and guidelines. No articles describing events in Asia, which detailed national management or specialty teams were identified. An additional nine sources were included resulting in a total of 51 articles highlighted for inclusion [2-4,6-11].

15 articles detail responses to specific burn MCIs (Appendix 1) [12-26]. 13 articles (reviews, guidelines, and mixed method studies) describe national burn plans, or clinical burn teams (Appendix 2) [10,27-37]. 16 additional articles (scientific reviews and guidelines) describe key factors of a burn MCI [38-53].

There was no literature outside of NHS guidelines which specifically discussed BIRTs in the UK. Concept of Operations: The Burns Annex, was published in September 2020 [3]. National burn plans and clinical teams worldwide which were described in literature are outlined below.

International burn plans

USA

The American Burn Association (ABA) plays a major role in the management of regional burns disasters and is involved in collaboration with government services. Specialist interest groups within the ABA provided experience from multiple disciplines and regions [24]. Burns Specialty Teams (BST’s) used to be deployed alongside disaster medical assistance teams. These were multidisciplinary and consist of 15 members with burn experience. Their role was to assist local services and potentially advise on secondary triage and transfers [49,54]. Tiered systems existed within states in isolation such as New York, to coalesce individual agencies and hospitals, however control is centralised through the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response [47,52].

BST’s were retired, perhaps due to their infrequent use and intensive resources, and instead there is a team available known as a Trauma Critical Care Team within the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS) [55].

Australia

The Australian Mass Casualty Burn Disaster Plan (AUSBURNPLAN), as described by Wood et al, is a national plan led by a central national disaster coordinator with aims to minimise parallel communications and aid in the redistribution of patients to health services in the second phase of an MCI [35]. A national database provides information on resource availability, transport, and capacity.

Switzerland

Healthcare throughout Switzerland is fragmented and not managed centrally, however a burn plan was created by emergency medical services, hospitals, disaster/burn specialists and public health officials [37]. Participating hospitals will accommodate a disaster on a national scale and have 24/7 availability of burns specialists who can assist in onsite triage. The participation of burn specialists operates on a voluntary basis. A study showed in 2016 out of 106 hospitals in Switzerland, 92% had disaster planning in place [30].

Netherlands

An article detailing the event in Volendam 2001 described patients being transported to the local hospitals without specific triage, at which the nearest burn centre would manage triage and redistribution [25]. Whilst the pre-hospital triage and communication was described as suboptimal, the triage and further management via burn specialists was deemed effective.

Following a nursing home fire in 2011, pre-hospital triage took place. Patients were transported to appropriate hospitals depending on their injuries and triage trigger [18]. A Major Incident Hospital (MIH) is part of the national disaster plan. It can be functional 30 minutes after activation in the event of a disaster.

Upon arrival of patients to an MIH, a secondary triage was carried out and they are further distributed in accordance with clinical requirements throughout the hospital.

This was completed by a specialist trauma/burn surgeon dependent on the injuries.

Sweden

Sweden’s national burn disaster plan was formulated by the two national burn centres and regional disaster organisations. Once again, following the alert from local services burn centres are made aware, and national coordination allocates resources. Pre-hospital assessment and subsequent triage is determined by emergency care physicians [56].

Belgium

The Belgian Association Burn of Injury (BABI) has central control of a plan which is triggered in an MCI, which is primarily delivered by the military. Activation depends on the early alert from emergency services. Following this, all burn centres available are made aware, with those closest to the incident providing immediate support. Burn teams (B-teams) are employed to advise and triage. They contain burn surgeons, nurses, and anaesthetists. Within Belgium, there are six burn centres and a total of 75 burn beds [27].

European Burns Association

There is a European mass burn casualty response plan which was initiated following the Romanian nightclub fire in 2015. The European Burns Association provide guidelines for secondary triage and management of burns. It aims to support the connection of national plans to the Emergency Response Coordination Centre, which operates under the European Union Civil Protection Mechanism [8]. Burn centres in various countries receive verification following an application and review of the facilities [9]. This generates fluidity for patient transfers and provides a larger resource for mass incidents. Qualifications awarded to clinicians operating under this service facilitate medical practice across borders, acting as a passport throughout Europe.

United Kingdom MCI plan and BIRTs

Within the UK there is an Emergency Preparedness, Resilience and Response (EPRR) framework for the National Health Service (NHS). There is a multidisciplinary team effort to coordinate and support patients during an MCI.

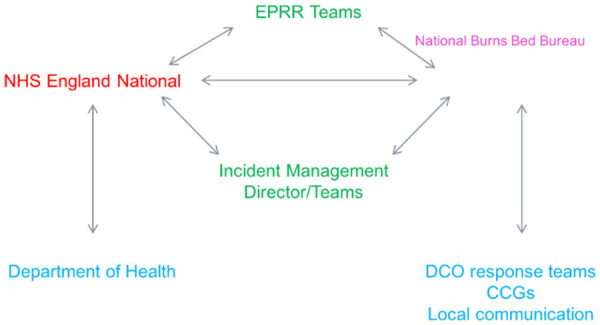

NHS EPRR provide centralised guidelines for MCIs including preparation, communication, integration, and direction for multiple groups such as NHS England, clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and ambulance services (Figure 1) [2]. Furthermore, they provide a Concept of Operations (CONOPS) for the management of MCIs, including burns. CONOPS estimate that an incident involving 20 level three burns patients (patients who require intensive care support) will result in a national incident. CONOPS has prepared a burns annex which aims to ‘describe efficient and effective distribution of a significant number of people receiving burns injuries’, with the additional of a BIRT, a new development in the annex [3].

Figure 1.

The national organisation of mass casualty events, UK.

The implementation of this plan can be subdivided into logistical and clinical cells. The logistical cells are primarily involved in coordinating available staff, including BIRT members, while the clinical cell is involved in clinical burn advice in the initial phases by the Burns Strategic Clinical Lead and coordinating teleconferences to tactically assess burns patient placement and transfer nationally [2].

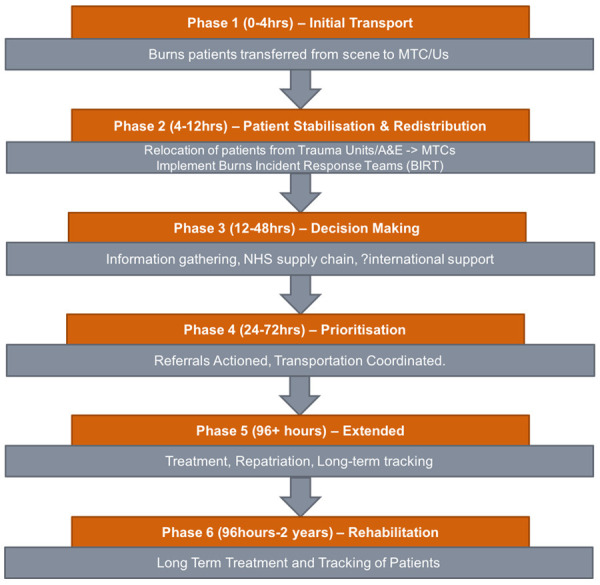

Alerts of MCIs are made through the National Burns Bed Bureau (NBBB). The response moves through phases starting with initial transport of patients from the scene of injury through to ongoing rehabilitation and re-integration of burns survivors (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The phases of management following a mass casualty incident (MCI).

There are a limited number of burns services nationally and therefore major trauma centres (MTCs) and emergency departments would undergo a preliminary triage and assessment of casualties by a burns strategic clinic lead or a BIRT team member if available.

BIRTs would be coordinated through NHS England Management and deployed to local services including those without specialist burn care. Patients would be redistributed via secondary triage to appropriate services, whilst advice is given via BIRT to local services regarding further management. Ideally a BIRT is formed from the same burn service, however members may be acquired from multiple [7]. Members involved within an MCI, will receive a checklist card listing responsibilities and necessary steps involved in their role.

Burns services are responsible for increasing the availability of as many beds/resources as possible and for making decisions regarding appropriate transfer to lower levels of care. At the time of notification of an MCI all burns services will temporarily close to new burns referrals until they are either stepped down or accept casualties.

BIRTs’ main responsibilities are to provide an experienced standardised assessment of burn injuries, allowing appropriate transfer and management of burn patients (Table 1). They provide support to others and advise about appropriate dressings and pain management. Their roles would involve collection of data and demographics using the BIRT Patient Clinical Assessment Forms [7]. It is important to understand that their role is not to be directly involved with transfer or retrieval, but to advise others in doing so; this is to maximise triage potential and most effectively utilise resources ensuring that inappropriate transfer/beds are not consumed.

Table 1.

BIRT person specification [7]

| Burns Incident Response Teams | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Who? | Specialist Burn Surgeon | Specialist Burn Anaesthetist | Specialist Burn Nurse |

| Requirements | Essential | Essential | Essential |

| ● GMC registered burn surgeon | ● GMC registered anaesthetist with burn experience | ● NMC registered nurse > 5 years burn experience | |

| ● Professional indemnity | ● Indemnity | ● Indemnity | |

| ● BIRT Training | ● BIRT Training | ● BIRT training | |

| ● Ability to work at a distance and collaboratively | ● Ability to work at a distance and collaboratively | ● Ability to work at a distance and collaboratively | |

| ●Able to travel | ● Able to travel | ● Able to travel | |

| Desirable | Desirable | Desirable | |

| ● ATLS/ABLS trained or similar | ● ATLS/ABLS trained or similar | ● ALTS/ABLS trained or similar | |

| Role | ● Advise on early management and resuscitation | ● Advise on early management and resuscitation | ● Advise on TBSA/depth assessment of severe burns |

| ● Highlight surgical emergencies | ● Highlight upper and lower airway risk | ● Advise on fluid resuscitation and monitoring | |

| ● Advice for future management | ● Advise on ICU management | ● Advise on debridement and dressings | |

What have previous events taught us?

There is limited literature involving burns disasters in Europe with anecdotal evidence, however some key factors are repeatedly highlighted (Table 2) [57]. Hughes et al, made several recommendations for the management of mass casualties [53].

Table 2.

| Preparation | ● Record of local and national resources including burn beds, dressings, staff and transportation |

| ● Surge capacity solutions should be considered for patients and staff | |

| ● Short- and long-term cost implications | |

| ● Early recognition of an MCI is vital | |

| ● Rapid formulation of response following report of an MCI from first responders | |

| Triage | ● Clear primary and secondary triage protocol, in accordance with ATLS guidelines |

| ● Primary triage may be conducted by non-specialists therefore guidelines are paramount | |

| ● Volunteers on site will encourage disorientation and decrease standardized triage, however should be expected | |

| ● Consider adjunct injuries | |

| ● Specialist triage onsite is unlikely to be effective or sustainable due to limited members of staff, lack of situational experience and increase risk of injury | |

| Hospital Care | ● Specialists should assume managerial roles, in order to care for the greatest number of patients effectively |

| ● Adequate outpatient support will be required in the short and long term, to provide a sustainable response and reduce resource usage | |

| ● “Non-survivable” triage should be determined at the primary hospital |

Preparation

It is important to be aware of available local and national resources, including total number of burns beds, a scarce resource worldwide. If capacity is exceeded, considerations can be given to alternative solutions such as surge increase in beds and staff [49]. Additional knowledge of equipment and supplies available locally and nationally is necessary [40]. Maintaining up to date records of resources will contribute to efficient planning and execution. Knowledge of the medical staff available and their capabilities, as well as transportation resources is vital to disaster management [48].

Any MCI will incur a new financial strain on services through the allocation and use of resources and loss of the normal elective work stream whilst the system deals with the aftermath of the incident; burns patients care typically taking resources and a long time. Consideration for the cost implications on the national service is imperative.

Early recognition of an event by emergency personnel secures time for services to prepare for and establish a response. Good communication becomes even more important in the instance of an unexpected event. Clear lineation of command and responsibility is necessary to maintain control and elicit the most effective response [58]. This is often carried out through a national command structure.

Anticipating workload, for example patients arriving at hospitals via private transportation, provides more time for secondary services to prepare [40]. Transportation to secondary services can involve assistance from various groups such as air ambulance, military and ambulance services, and a centralised managerial approach is considered best practice.

Care will be affected by the education and experience of individuals working within the emergency services, therefore appropriate training in expectation of possible mass events is useful.

Triage

General guidelines for triage of MCIs include categorising the patients into four categories usually at the scene; immediate care needed (red), intermediate or urgent care (within two to four hours, yellow), delayed care (green), and deceased (black) [6].

Effective triage pre-hospital depends on the experience and training of the emergency services and can increase the availability at trauma and burn centres. Clear standardised guidelines are beneficial for non-burn professionals in this environment [37]. Triage may be further complicated by adjunct injuries and trauma [38]. Volunteers may be detrimental to incident management and if not regulated can result in further disorientation [46].

A specialist is advantageous, as correct estimation of burn size, age, depth, and comorbidities have a large impact on further management and the subsequent location of the patient. Avoidance of flooding specialist resources with patients who do not require that level of support, ensure those that do are identified. The state and classification of patients may change over time and therefore triage is a dynamic process. Problems may be encountered such as inexperience in coordinated care in an unfamiliar environment, increased risk of injury to the provider due to location and lack of situational experience [13]. Burns specialists are arguably better utilised providing expertise in secondary care.

Hospital care

Due to the large volume of patients, it is recommended burn specialists assume managerial and advise others, rather than deal with single patients [40]. Initial triage will identify many patients who do not require hospital admission. Therefore, supported outpatient management will be valuable in preserving limited resources.

Discussion

Will there be obstacles for specialist teams?

The coordination of an MCI requires extensive multidisciplinary logistics, communication, and expertise to ensure the efficacy of treatment delivered. Most of the evidence for BIRT’s remains anecdotal and as such there will be certain challenges to consider. The advantages are clear; a team of well-trained individuals who can increase the efficiency of patient management in the long and short term.

Firstly, it is unclear who or how a BIRT members’ normal activities within the NHS would be supported. Financial incurrence at a local and national level should be considered for immediate and long-term management. They will be a resource intensive team with costs if they are to remain a mobile unit. 24/7 cover at short notice is also important to establish, and it is unclear if this should be managed locally or nationally. Currently the plan describes management through the logistical cell of the National EPRR [2,7].

A significant hurdle to face, for most national management is coordinated training of staff. As the team may be recruited from multiple local services, this could provide an extra challenge to communication, during an already stressful experience. It would be important to involve centralized teaching. Simulation training has become a substantial part of medical education and would provide feedback to improve the performance of BIRTs. A recommendation was made by Hughes et al, advising that burn severity should be estimated by total body surface area (TBSA) alone and not include depth assessment [53]. This would help reduce the level of expertise required to triage burns, as depth can often be difficult to assess especially in the immediate hours following injury. There is still scope for inaccuracy in this assessment, and severe full thickness burns may cause more complications depending on location and circumference than higher percentage superficial burns.

Difficulties may arise due to regional differences in hospital/pre-hospital resources, such as IT systems, resulting in disrupted access to records and investigations in an acute setting. For this reason, an NHS ‘passport’ may be useful, which can be nationally recognised to identify staff and allow access to different hospital systems throughout the UK [2,3].

Many members of the BIRT will be motivated individuals, however it is important that they are legally protected. It is important to quantify under these circumstances what indemnity would protect them outside of the normal NHS role and who would fund this. At present indemnity will be covered by the members employing NHS Trust’s Membership of Clinical Negligence Scheme which is administered by NHS Resolution [2,7].

How will previous experiences, affect the UKs national plan?

Evidence to support a national plan exists predominantly from anecdotal experience of MCIs. Recognition of previous limitations experienced worldwide has led to the development of a well-structured emergency plan within the UK. This plan coordinates CONOP’s management of mass casualties with BIRT. This involves early recognition and notification of an event to allow resources to be retrieved and appropriate triage by experienced clinicians (BIRT). This will minimise unwarranted management and transfer. It has been concluded that a senior and experienced burn team should be utilised effectively through appropriate triage of patients rather than aiding resuscitation or transfer [13].

It is unlikely that an MCI will result in burns alone. Many patients may sustain life and limb threatening injuries such as severe head injuries, lower limb injuries and penetrating injuries to chest/abdomen. They will require immediate assessment and management. This would be alongside the BIRT team who may not have the experience to triage these patients therefore a clear plan of liaising between burns clinical leads and major trauma clinical leads is needed. It is unclear if it is feasible for these emergency plans to work seamlessly in parallel [3].

Many MTCs and EDs will have a limited supply of specialised burn dressings/equipment, with most hospitals having a stock which is replenished routinely based on the NHS supply chain system. A hospital should be able to replenish their stock within a five-hour time frame; this should be built into local plans [2]. It is important that MTCs and EDs review their access to burns consumables. Issues may arise when demand exceeds supply. Therefore, it is imperative to consider local stockpiles of burns consumables which can be delivered in conjunction with BIRT teams.

Whilst reviewing burn MCIs in Europe, concerns were raised over infection prevention [1]. If large burns patients require transfer nationally or internationally there is a risk of creating multi-resistant organisms resulting from cross infection. This is difficult to manage, and advice should be sought from local microbiology clinical leads however it may be necessary for the Burns Strategic Clinical Lead to address this when evaluating national/international transfers [2,7].

When moving through the different phases of the MCI response the strain upon staff and resources is evident. This will likely lead to delays, from staff secondments and utilisation of resources such as theatre space for other specialties as well as the burns services. Burn survivor’s journeys will continue past the marked phases of response. Burn injuries can be complex and require prolonged hospital stay, multiple attendances, the involvement of multi-disciplinary teams, rehabilitation, and reintegration into the community. Occupational therapists will form an integral part of patient care and should be integrated into this framework. This journey can last for many years especially with paediatric victims and the resources required to accommodate the prolonged management should be addressed. It is necessary to support staff which can be aided by appropriate pre-incident training including anticipation of what to expect and appropriate debriefing following the incident [59]. Mock scenarios could help demonstrate the effectiveness of a BIRT [12].

Conclusions

The implementation of a national burns response plan is a necessary step forward for effective management of these continuing mass casualty events. The available literature supports the need for preparation and organized response with a centralized control. Increased awareness and understanding of the role of Burns Incidence Response Teams is important and highlights the need for specialist input in the long and short term. Factors which may affect the implementation of BIRT’s need to be explored in further detail.

Appendix 1.

| Author | Journal | Study Type | Year | Country | Event | National/Local Leading Management | Burn plan | Burn Clinical Team | Outcome/Key Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lancet et al | Disaster medicine & public health preparedness | Mixed Method | 2020 | New York, USA | MCI training exercise | Local (State) | American Burn Association (ABA) | Burn Surgeon | ● Clear triage guidelines to ensure efficient primary and secondary triage |

| Trauma Surgeon | |||||||||

| ED Physician | |||||||||

| Lin et al | Prehospital Emergency Care | Mixed Method | 2018 | Taiwan | Formosa Fun Coast Theme Park Explosion | Regional | n/r | Burn Specialists consultants | ● Rapid prioritization of patients for coordinated secondary transfers |

| Craigie et al | BMJ | Event Report | 2018 | Manchester, UK | Manchester Bombing | Local | n/r | Major Trauma Consultant in each centre | ● Key factors are prehospital triage, transport and transfer protocol |

| Wang et al | Burns | Retrospective case series | 2016 | Taiwan | Formosa Fun Coast Theme Park Explosion | National Central control Emergency Medical Operation Centre | n/r | n/r | ● Consider military input |

| ● Patient identification is needed for patient safety | |||||||||

| ● Key factors include transport and communication | |||||||||

| Cheng et al | PRS Journal | Retrospective case series | 2016 | Taiwan | Formosa Fun Coast Theme Park Explosion | National EOC & MOHW | Critical event preparedness code | n/r | ● Educate staff to ensure accurate onsite triage |

| Wang et al | Formosan medical association journal | Event Report | 2015 | Taiwan | Formosa Fun Coast Theme Park Explosion | National EOC & MOHW | n/r | n/r | ● Clear central command |

| ● Triage guidelines | |||||||||

| ● Education | |||||||||

| ● Resource Management | |||||||||

| Koning et al | European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery | Event Report | 2014 | Netherlands | Nursing Home Fire | National Major Incident Hospital/Ministry of Defence & Military | n/r | n/t | ● Surge capacity |

| Dal Ponte et al | Prehospital and disaster medicine | Event report | 2014 | Brazil | Nightclub fire | Regional centre of command set up in local hospital | n/r | n/r | ● Automated warning system |

| ● Central communication | |||||||||

| Cameron et al | MJA | Retrospective report | 2009 | Australia | Black Saturday Bushfires | National Regional (state) | AUSBURNPLAN national | Burns unit director | ● Difficult to manage volunteers and many parties who were involved at the scene |

| Victorian state trauma system | 2 Burn Surgeons | ||||||||

| Burns liaison nurse | |||||||||

| Burns care coordinator | |||||||||

| Chim et al | Critical Care | Retrospective report | 2007 | Indonesia | Burns victims of suicide bomb attacks | Local | n/r | n/r | ● Prehospital triage is essential |

| Aylwin et al | The Lancet | Retrospective report | 2006 | London, UK | London Bombings | Regional - London Emergency Services liaison panel | n/r | n/r | ● 1 burn centre - would benefit from a burn plan |

| Yurt et al | Journal of Burn care and research | retrospective report | 2006 | New York, USA | September 11th | National & Regional (state) | ABA | Emergency preparedness coordinator | ● Safe evacuation and strong triage protocol to reduce casualty surge |

| NY State trauma system | 2x burn nurses | ||||||||

| 2x ED directors | |||||||||

| 3x specialist physicians | |||||||||

| Welling et al | Journal of health and organisational management | Mixed Method | 2006 | Netherlands | Volendam Fire | n/r | n/r | n/r | ● Resource planning in non-specialised hospitals |

| Welling et al | Burns | Retrospective report | 2005 | Netherlands | Volendam fire | National Major Incident Hospital | n/r | Burns specialist | ● International collaboration education |

| Kennedy et al | Journal of burn care and rehabilitation | Retrospective report | 2006 | Australia | Bali Bombing | International Communication National plan | National Disaster Plan | n/r | ● Utilise non-specialised resources |

Appendix 2.

Summary of Term Search: Articles which describe national/local burn plans and burn clinical teams (n/r = not recorded) [10,27-37]

| Author | Journal | Study Type | Year | Country | National/Regional/Local | Burn plan | Burn Clinical Team | Burn Team Role | Key Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Shamsi et al | Disaster medicine and Public health Preparedness | Retrospective cross sectional | 2019 | Belgium | National Central Coordination Office | Belgian Association of burn injury (BABI) plan | n/r | Direct Transport | ● Central control of burns mass casualties |

| Patient distribution between burn centres | |||||||||

| Al Shamsi et al | Journal of Burn Care and Research | Mixed Method | 2019 | Belgium | National Burn Teams | BABI Plan | Burn Surgeon | Deployed to scene or non-specialised hospitals in first 12-24 hours | ● Paediatric management has yet to be defined |

| Burn Anaesthetist | ● Consider communication, transportation, triage, transfer guidance, and cost | ||||||||

| Burn Specialised Nurse | |||||||||

| Dell’era et al | Disaster Medicine and Public health Preparedness | Mixed Method | 2018 | Switzerland | Local (State) | n/r | Voluntary Burn Specialists | Onsite triage | ● Communication between a fragmented healthcare system is paramount |

| Conlon et al | Journal of Burn Care and Research | Review | 2014 | New Jersey, USA | Regional | ABA | n/r | n/r | ● triage facilities “tier facility” preparation and planning |

| Kearns et al | South Med Journal | Review | 2013 | southern US | Regional | southern burn plan | n/r | n/r | ● interstate communication |

| ● triage tools | |||||||||

| ● institutional, interfacility, interstate communication | |||||||||

| Leahy et al | Journal of Burn Care and Research | Review | 2012 | New York, USA | State Burn Logistic Coordination Centre | New York State Burn Plan | n/r | n/r | ● Virtual Burn Consultation centre to track beds, transport and resources |

| Wood et al | Emergency Health Threats Journal | Review | 2008 | Australia | National | AUSBURNPLAN | n/r | n/r | ● Single channel of communication |

| ● National Burn database | |||||||||

| Greenwood et al | Prehospital and disaster Medicine | review | 2006 | Australia | International | AUSBURNPLAN State disaster plans | National Burn Assessment Team | Burn Management Advice | ● BAT collaboration with retrieval service for optimal outcomes |

| Senior burn consultant | |||||||||

| Burns nurse | |||||||||

| Burns registrar | |||||||||

| Jordan et al | Journal of burn care and rehabilitation | Guidelines | 2005 | USA | National & State plans | ABA Regional Burn Teams | 6 Burn Nurses | Triage, Patient Management Advice | ● Deployed with salary, expenses and housing provided for minimum 2 weeks |

| 4 Technicians | |||||||||

| 2 Burn surgeons | |||||||||

| 1 Anaesthetist | |||||||||

| Sheridan et al | Journal of burn care and rehabilitation | Review | 2005 | USA | National & State plans | ABA Burn Speciality Teams (BST) | 4 national BSTs | Triage, Resuscitation, Stabilization | ● voluntary basis mobile equipment package |

| ABA | Journal of burn care and rehabilitation | Guidelines | 2005 | USA | National Military | BSTs | 15 Personnel: | local/state/federal support secondary triage/transfer | ● primary and secondary triage protol |

| 1 burn surgeon | |||||||||

| 6 burn nurses | |||||||||

| anaesthetist | |||||||||

| respiratory therapist | |||||||||

| Administrator | |||||||||

| 5 support staff | ● advises BST’s should help with secondary triage and transfer away from epicentre | ||||||||

| Potin et al | Burns | Review | 2010 | Switzerland | National central coordination of resources | n/r | n/r | n/r | ● burn triage by specialist staff is effective |

| Local triage is managed my emergency departments |

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Camacho NA, Hughes A, Burkle F, Ingrassia PL, Ragazzoni L, Redmond A, Norton I, von Schreeb J. Education and training of emergency medical teams: recommendations for a global operational learning framework. PLoS Curr. 2016:8. doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.292033689209611ad5e4a7a3e61520d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS England. NHS England emergency preparedness, resilience and response framework. 2015 doi: 10.1136/jramc-2018-000925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NHS England, NHS Operations, National EPRR Team. Concept of Operations for the management of Mass Casualties. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 4.NNBC. National Burn Care Referral Guidance. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.PRISMA Guidelines. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henry S, Brasel K, Stewart R. Advanced Trauma Life Support. 10th ed. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS England. Burn Incident Response Teams (BIRTs) Person Specifications. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Burn Association. EBA Guidelines for National Preparedness Plans. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Burn Association. Verification Burn Centres [Google Scholar]

- 10.Association AB. Burn Care Resource Directory. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Global Terrorism Database. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lancet EA, Zhang WW, Roblin P, Arquilla B, Zeig-Owens R, Asaeda G, Kaufman B, Alexandrou NA, Gallagher JJ, Cooper ML, Styles T, Prezant DJ, Quinn C. Factors influencing the prioritization of injured patients for transfer to a burn or trauma center following a mass casualty event. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021;15:78–85. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2019.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin CH, Lin CH, Tai CY, Lin YY, Shih FFY. Challenges of burn mass casualty incidents in the prehospital setting: lessons from the Formosa fun coast park color party. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23:44–48. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2018.1479473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craigie RJ, Farrelly PJ, Santos R, Smith SR, Pollard JS, Jones DJ. Manchester Arena bombing: lessons learnt from a mass casualty incident. BMJ Mil Health. 2020;166:72–75. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2018-000930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang TH, Lin TY. Responding to mass burn casualties caused by corn powder at the Formosa water park in 2015. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114:1151–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang TH, Jhao WS, Yeh YH, Pu C. Experience of distributing 499 burn casualties of the June 28, 2015 Formosa color dust explosion in Taiwan. Burns. 2017;43:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng MH, Mathews AL, Chuang SS, Lark ME, Hsiao YC, Ng CJ, Chung KC. Management of the Formosa color dust explosion: lessons learned from the treatment of 49 mass burn casualty patients at chang gung memorial hospital. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:1900–1908. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koning SW, Ellerbroek PM, Leenen LP. Indoor fire in a nursing home: evaluation of the medical response to a mass casualty incident based on a standardized protocol. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2015;41:167–178. doi: 10.1007/s00068-014-0446-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dal Ponte ST, Dornelles CF, Arquilla B, Bloem C, Roblin P. Mass-casualty response to the kiss nightclub in Santa Maria, Brazil. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2015;30:93–96. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X14001368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron PA, Mitra B, Fitzgerald M, Scheinkestel CD, Stripp A, Batey C, Niggemeyer L, Truesdale M, Holman P, Mehra R, Wasiak J, Cleland H. Black Saturday: the immediate impact of the February 2009 bushfires in Victoria, Australia. Med J Aust. 2009;191:11–16. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chim H, Yew WS, Song C. Managing burn victims of suicide bombing attacks: outcomes, lessons learnt, and changes made from three attacks in Indonesia. Crit Care. 2007;11:R15. doi: 10.1186/cc5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aylwin CJ, König TC, Brennan NW, Shirley PJ, Davies G, Walsh MS, Brohi K. Reduction in critical mortality in urban mass casualty incidents: analysis of triage, surge, and resource use after the London bombings on July 7, 2005. Lancet. 2006;368:2219–2225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69896-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yurt RW, Bessey PQ, Alden NE, Meisels D, Delaney JJ, Rabbitts A, Greene WT. Burn-injured patients in a disaster: September 11th revisited. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:635–641. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000236836.46410.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welling L, Boers M, Mackie DP, Patka P, Bierens JJ, Luitse JS, Kreis RW. A consensus process on management of major burns accidents: lessons learned from the café fire in Volendam, The Netherlands. J Health Organ Manag. 2006;20:243–252. doi: 10.1108/14777260610662762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welling L, Van Harten SM, Patka P, Bierens JJLM, Boers M, Luitse JS, Mackie DP, Trouwborst A, Gouma DJ, Kreis RW. The café fire on New Year’s Eve in Volendam, the Netherlands: description of events. Burns. 2005;31:548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennedy PJ, Haertsch PA, Maitz PK. The Bali burn disaster: implications and lessons learned. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26:125–131. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000155532.31639.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Shamsi M, de Almeida MM, Nyanchoka L, Guha-Sapir D, Jennes S. Assessment of the capacity and capability of burn centers to respond to burn disasters in Belgium: a mixed-method study. J Burn Care Res. 2019;40:869–877. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irz105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Shamsi M, Jennes S. Implication of burn disaster planning and management: coverage and accessibility of burn centers in Belgium. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;14:694–704. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2019.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conlon KM, Ruhren C, Johansen S, Dimler M, Frischman B, Gehringer E, Houng A, Marano M, Petrone SJ, Mansour EH. Developing and implementing a plan for large-scale burn disaster response in New Jersey. J Burn Care Res. 2014;35:e14–20. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182779b59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dell’Era S, Hugli O, Dami F. Hospital disaster preparedness in Switzerland over a decade: a national survey. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2019;13:433–439. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2018.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kearns R, Holmes J, Cairns B. Burn disaster preparedness and the southern region of the United States. South Med J. 2013;106:69–73. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31827c4d94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leahy NE, Yurt RW, Lazar EJ, Villacara AA, Rabbitts AC, Berger L, Chan C, Chertoff L, Conlon KM, Cooper A, Green LV, Greenstein B, Lu Y, Miller S, Mineo FP, Pruitt D, Ribaudo DS, Ruhren C, Silber SH, Soloff L. Burn disaster response planning in New York City: updated recommendations for best practices. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:587–594. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318241b2cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ABA Board of Trustees and Committee on Organization and Delivery of Burn Care. Disaster management and the ABA plan. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26:102–106. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000158926.52783.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheridan R, Barillo D, Herndon D, Solem L, Mohr W, Kadilack P, Whalen B, Morton S, Nall J, Massman N, Buffalo M, Briggs S. Burn specialty teams. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26:170–173. doi: 10.1097/01.bcr.0000155544.38709.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood F, Edgar D, Robertson A. Development of a national burn network: providing a co-ordinated response to a burn mass casualty disaster within the Australian health system. Emerg Health Threats J. 2008;1:e4. doi: 10.3134/ehtj.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenwood JE, Pearce AP. Burns assessment team as part of burn disaster response. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2006;21:45–52. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00003319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potin M, Senechaud C, Carsin H, Fauville JP, Fortin JL, Kuenzi W, Lupi G, Raffoul W, Shiestl C, Zuercher M, Yersin B, Berger MM. Mass casualty incidents with multiple burn victims: rationale for a Swiss burn plan. Burns. 2010;36:741–50. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atiyeh B, Gunn SW, Dibo S. Primary triage of mass burn casualties with associated severe traumatic injuries. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2013;26:48–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barillo DJ, Wolf S. Planning for burn disasters: lessons learned from one hundred years of history. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:622–634. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000236823.08124.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cancio LC, Pruitt BA. Management of mass casualty burn disasters. International Journal of Disaster Medicine. 2004;2:114–129. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dai A, Carrougher GJ, Mandell SP, Fudem G, Gibran NS, Pham TN. Review of recent large-scale burn disasters worldwide in comparison to preparedness guidelines. J Burn Care Res. 2017;38:36–44. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenwood JE, MacKie IP. Factors for consideration in developing a plan to cope with mass burn casualties. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79:581–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2009.05007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haberal M. Guidelines for dealing with disasters involving large numbers of extensive burns. Burns. 2006;32:933–939. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horner CW, Crighton E, Dziewulski P. 30 Years of burn disasters within the UK: guidance for UK emergency preparedness. Burns. 2012;38:578–584. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kearns RD, Conlon KM, Valenta AL, Lord GC, Cairns CB, Holmes JH, Johnson DD, Matherly AF, Sawyer D, Skarote MB, Siler SM, Helminiak RC, Cairns BA. Disaster planning: the basics of creating a burn mass casualty disaster plan for a burn center. J Burn Care Res. 2014;35:1–13. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31829afe25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kearns RD, Conlon KM, Valenta AL, Matherly AF, Jeng JC. Fostering disaster preparedness through the “Grass Roots Efforts” of an American burn association special interest group. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:e394. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kearns RD, Holmes JH, Alson RL, Cairns BA. Disaster planning: the past, present, and future concepts and principles of managing a surge of burn injured patients for those involved in hospital facility planning and preparedness. J Burn Care Res. 2014;35:e33–42. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318283b7d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kearns RD, Hubble MW, Holmes JH, Cairns BA. Disaster planning: transportation resources and considerations for managing a burn disaster. J Burn Care Res. 2014;35:e21–32. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182853cf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kearns RD, Marcozzi DE, Barry N, Rubinson L, Hultman CS, Rich PB. Disaster preparedness and response for the burn mass casualty incident in the twenty-first century. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGregor JC. Major burn disasters: lessons to be learned from previous incidents and a need for a national plan. Surgeon. 2004;2:249–250. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(04)80092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mackie DP. Mass burn casualties: a rational approach to planning. Burns. 2002;28:403–404. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yurt RW, Lazar EJ, Leahy NE, Cagliuso NV, Rabbitts AC, Akkapeddi V, Cooper A, Dajer A, Delaney J, Mineo FP, Silber SH, Soloff L, Magbitang K, Mozingo DW. Burn disaster response planning: an urban region’s approach. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:158–165. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31815f2b8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hughes A, Almeland SK, Leclerc T, Ogura T, Hayashi M, Mills JA, Norton I, Potokar T. Recommendations for burns care in mass casualty incidents: WHO emergency medical teams technical working group on burns (WHO TWGB) 2017-2020. Burns. 2021;47:349–370. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American Burn Association. Disaster management and the ABA plan. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. Trauma and Critical Care Teams [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nilsson H, Jonson CO, Vikström T, Bengtsson E, Thorfinn J, Huss F, Kildal M, Sjöberg F. Simulation-assisted burn disaster planning. Burns. 2013;39:1122–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Relvas LM, de Oliveira AP. The medical response to burns disasters in europe: a scoping review. Am J Disaster Med. 2018;13:169–179. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2018.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheridan RL, Friedstat J, Votta K. Lessons learned from burn disasters in the post-9/11 Era. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brooks S, Dunn R, Amlot R, Ruben GJ, Greenberg N. Protecting the psychological wellbeing of staff exposed to disaster or emergency at work: a qualitative study. BMC Psychol. 2019;7:78. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0360-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kearns RD, Hubble MW, Lord GC, Holmes JH, Cairns BA, Helminiak C. Disaster planning: financing a burn disaster, where do you turn and what are your options when your hospital has been impacted by a burn disaster in the United States? J Burn Care Res. 2016;37:197–206. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]