Abstract

Germ granules harbor processes that maintain germline integrity and germline stem cell capacity. Depleting core germ granule components in C. elegans leads to the reprogramming of germ cells, causing them to express markers of somatic differentiation in day-two adults. Somatic reprogramming is associated with complete sterility at this stage. The resulting germ cell atrophy and other pleiotropic defects complicate our understanding of the initiation of reprogramming and how processes within germ granules safeguard the totipotency and immortal potential of germline stem cells. To better understand the initial events of somatic reprogramming, we examined total mRNA (transcriptome) and polysome-associated mRNA (translatome) changes in a precision full-length deletion of glh-1, which encodes a homolog of the germline-specific Vasa/DDX4 DEAD-box RNA helicase. Fertile animals at a permissive temperature were analyzed as young adults, a stage that precedes by 24 h the previously determined onset of somatic reporter-gene expression in the germline. Two significant changes are observed at this early stage. First, the majority of neuropeptide-encoding transcripts increase in both the total and polysomal mRNA fractions, suggesting that GLH-1 or its effectors suppress this expression. Second, there is a significant decrease in Major Sperm Protein (MSP)-domain mRNAs when glh-1 is deleted. We find that the presence of GLH-1 helps repress spermatogenic expression during oogenesis, but boosts MSP expression to drive spermiogenesis and sperm motility. These insights define an early role for GLH-1 in repressing somatic reprogramming to maintain germline integrity.

Keywords: GLH-1, Vasa, DDX4, Germ granules, P granules, C. elegans, Germline, Sperm, Spermiogenesis, Major sperm protein, MSP, Neuropeptides, Polysomes

1. Introduction

Cytoplasmic, germline-specific ribonucleoproteins called germ granules are hubs of small RNA biogenesis and amplification (Phillips and Updike, 2022). In C. elegans, processes within germ granules confer a transgenerational memory of gene expression and ensure robust fertility and cellular potency through environmental challenges. Coincident depletion of four core germ-granule components (pgl-1, pgl-3, glh-1, glh-4) by RNAi feeding (germ-granule RNAi) prevents germ-granule assembly in the progeny, and consequently, germ cells lose potency and express markers of somatic differentiation (Updike et al., 2014). Early events that trigger somatic reprogramming following germ granule depletion are difficult to ascertain as somatic reporters are not expressed in germ-granule depleted animals until the second day of adulthood, coincident with atrophied germlines and other pleiotropic defects. Transcriptional profiling of dissected germlines during the early events of somatic reprogramming reveals a slight decrease in oogenic mRNAs, higher levels of spermatogenic mRNAs, and evidence of an incomplete sperm-to-oocyte switch, but no overall increase in soma-enriched transcripts (Campbell and Updike, 2015). A follow-up study profiled mRNAs from the fourth larval stage to the second day of adulthood following germ-granule RNAi depletion (Knutson et al., 2017). Here, evidence was found for increased somatic mRNA accumulation in the germline, but again, not until the second day of adulthood. None of these three studies completely uncoupled the accumulation of somatic mRNAs from germ-line atrophy and sterility. These approaches were unable to delineate the early events of somatic reprogramming or fully resolve whether processes within intact germ granules antagonize somatic expression through mRNA accumulation, mRNA translation, or a combination of both.

Importantly, Knutson et al. demonstrated that the germline expression of GFP-tagged somatic transgenes could be recapitulated in strains carrying a glh-1 loss-of-function allele. At 24 °C, the efficiency of somatic reprogramming in this glh-1 mutant was nearly three times higher than with germ-granule RNAi or in pgl-1 or pgl-1; pgl-3 mutant strains at the same temperature (Knutson et al., 2017). At restrictive temperatures of 26 °C, this loss-of-function allele is sterile, with spermatheca nearly devoid of sperm (Spike et al., 2008). This finding suggested that early and initial somatic reprogramming events can be uncoupled from sterility and other germline defects if profiled in healthy glh-1 loss-of-function mutants prior to somatic reporter expression. Here we have taken that approach, profiling both the transcriptome and translatome of a precise glh-1 full coding region deletion strain in synchronized one-day-old adults grown at the permissive temperature of 20 °C – conditions optimized to preserve germline development and minimize the occurrence of pleiotropic defects.

GLH-1 is a homolog of Vasa/DDX4, a non-sequence-specific DEAD-box RNA helicase expressed in the germ cells of animals. In C. elegans, there are four GLH proteins, GLH-1, GLH-2, GLH-3, and GLH-4 (Kuznicki et al., 2000). Both GLH-1 and GLH-4 are found in other nematode species, while GLH-1 gave rise to GLH-2 and GLH-3 through a more recent duplication in C. elegans (Bezares-Calderon et al., 2010; Spike et al., 2008). Of the four GLH proteins, only GLH-1 and GLH-2 contain all the signature domains that distinguish Vasa from other DEAD-box helicases (Marnik et al., 2019). GLH-1 is the most prominent of the four GLHs in expression, germ-granule dispersion, and germline phenotypes, but null alleles retain fertility at the permissive temperature of 20 °C due to partial redundancy with GLH-2 and GLH-4 (Kuznicki et al., 2000; Spike et al., 2008). This redundancy provides the opportunity to survey subtleties in germline development caused by the loss of GLH-1.

Models for Vasa/DDX4 function emphasize its association with Argonaute proteins to stimulate piRNA amplification in the germline (Dai et al., 2022; Dehghani and Lasko, 2016; Kuramochi-Miyagawa et al., 2010; Malone et al., 2009; Megosh et al., 2006; Wenda et al., 2017; Xiol et al., 2014). While C. elegans glh-1 mutants do not show exogenous RNAi defects (Spike et al., 2008), germline RNAi inheritance is compromised (Spracklin et al., 2017). GLH-1 has also been shown to bind specific microRNAs to facilitate translational silencing (Dallaire et al., 2018). Multiple studies have demonstrated an affinity between GLH-1 and the Argonautes PRG-1 and WAGO-1 (Chen et al., 2020, 2022; Dai et al., 2022; Marnik et al., 2019; Price et al., 2021). In addition, the depletion of germ-granule components phenocopies prg-1 mutant sterility and increased spermatogenic transcripts. (Campbell and Updike, 2015; Cornes et al., 2022; Spichal et al., 2021). Currently, evidence directly implicating small RNA regulation to somatic reprogramming in glh-1 mutants is sparse and may point to functions of GLH-1 that are piRNA-independent.

One likely function for Vasa/DDX4 homologs like GLH-1 during germ cell development is translational regulation (Mercer et al., 2021) or, more specifically, the hand-off from germ-granule-mediated mRNA surveillance prior to translation initiation. As such, the impact of GLH-1 on expression would be better assessed by profiling the translation efficiency of individual mRNAs along with changes in their abundance. Vasa/DDX4 resembles eukaryotic initiation factor-4A (eIF4A) (Lasko and Ashburner, 1988). In Drosophila, Vasa activates the translation of nanos in the pole plasm of the embryo in conjunction with the translation initiation factor eIF5B (Carrera et al., 2000; Gavis and Lehmann, 1994; Johnstone and Lasko, 2004). Vasa also mediates translational repression through interactions with RNA-binding proteins Bruno and the eIF4E interacting protein, Cup (Ottone et al., 2012). GLH-1 exhibits an affinity for the eIF3 complex in C. elegans (Marnik et al., 2019). In Drosophila, piRNA regulation via the PIWI protein Aubergine recruits eIF3 to activate translation in the germplasm (Ramat et al., 2020). In mammals, a MIWI/piRNA/eIF3 complex binds a subset of spermiogenic mRNAs to activate their translation (Dai et al., 2019). Therefore, Vasa/DDX-4/GLH proteins likely play dynamic roles in transitioning from RBP-, micro-RNA-, or piRNA-mediated translational repression to initiation complex assembly and mRNA translational activation. C. elegans germ granules are known assembly sites of eIF4E:4EIP complexes that have been shown to exert translational repression as messenger ribonucleoproteins (mRNPs) (Huggins et al., 2020; Huggins and Keiper, 2020); however, the extent to which germ-granule components interface with translation initiation complexes has not thoroughly been explored.

Here an alternative approach is used to decipher the impact of GLH-1 on germline development. Rather than evaluating mRNA regulation in severe terminal phenotypes, we examine more subtle impacts on the transcriptome and translatome when germ-granule assembly, in other-wise healthy one-day-old adults, is compromised by glh-1 loss. We find that most changes in mRNA accumulation correlate with its fraction being translated; however, increases of spermatogenic mRNAs are largely offset to wild-type levels in their translation. Two smaller gene classes stand out in their regulation by GLH-1. First, the abundance of MSP-domain-encoding mRNAs decreases in both total and translated fractions in the absence of GLH-1, in contrast to most other spermatogenic mRNAs that accumulate when germ granules are compromised. This decrease in MSP expression impacts spermiogenesis, specifically pseudopod extension, and suggests that GLH-1 drives MSP expression and spermiogenesis under wild-type conditions. Second, mRNAs encoding neuropeptides accumulate and become translated upon germ-granule depletion or glh-1 loss. These increases suggest that processes within germ granules initially antagonize neuronal reprogramming, not by blocking the expression of neuronal transcription factors but by quelling the expression of neuropeptides. A critical next step will be determining the GLH-1-dependent processes through which MSP and neuropeptide mRNAs are recognized and regulated.

2. Material and methods

2.1. C. elegans strains and maintenance

Strains were maintained at 20 °C on nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with Escherichia coli OP50 as previously described (Brenner, 1974). The strain designated as wild type (WT) - DUP64: glh-1(sam24[glh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I, and the strain designated as (Δglh-1) - DUP144: glh-1(sam65[Δglh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I, were previously described (Marnik et al., 2019). A CRISPR/Cas9 protocol adapted from (Ghanta and Mello, 2020) was used on WT DUP64 and Δglh-1 DUP144 to create DUP206: glh-1(sam24[glh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I; msp-142(sam116 [msp-142::mCherry::V5]) II, DUP210: glh-1(sam65 [Δglh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I; msp-142(sam116[msp-142::mCherry::V5]) II, DUP211: glh-1(sam24 [glh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I; ssq-1(sam120[V5::mCherry::ssq-1]) IV, and DUP216: glh-1(sam65[Δglh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I; ssq-1(sam120[V5::mCherry::ssq-1]) IV. The him-5(e1490) allele was crossed into WT DUP64, Δglh-1 DUP144, DUP206, and DUP211 to generate KX199: glh-1(sam24 [glh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I; him-5 (e1490) V, KX200: glh-1(sam65 [Δglh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I; him-5 (e1490) V, KX197: glh-1(sam24 [glh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I; ssq-1(sam120[V5::mCherry::ssq-1]) IV; him-5 (e1490) V, and KX198: glh-1(sam24[glh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I; msp-142(sam116[msp-142::mCherry::V5]) II; him-5 (e1490) V. KX199, KX200, KX197, and KX198 strains demonstrated an increased male population by about 20–25%. The strain carrying fog-2(q71) V used in the mating assay was derived from JK574.

2.2. Polysome profiling and mRNA-seq

C. elegans strains DUP64 glh-1(sam24[glh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) and DUP144 glh-1(sam65[Δglh-1::gfp::3xFlag]) I (Marnik et al., 2019) were used in the polysome profiling experiments. For each of three replicates from each strain, 25 recently starved plates (Fig. 1A and ) of either DUP64 (WT) or DUP144 (Δglh-1) were added to 1L of S Media with 5 g of freeze-dried OP50 (LabTie, Leiden, The Netherlands). These cultures were separated into four 250 ml aliquots in 1L beveled flasks to improve aeration (Figs. 1A and 2) and incubated in shakers at 20 °C. Once worms were gravid, they were precipitated and washed. 40 ml of bleach solution (3 parts water, 1 part Clorox bleach, 0.1 parts 10M NaOH) was prepared (Figs. 1A and 3) and added to the worms for 3 min, followed by three washes, to harvest embryos (Figs. 1A and 4) which were then allowed to hatch overnight on unseeded plates. Synchronized L1-staged worms were used to inoculate 1L of S Media with OP50, separated into four flasks (Figs. 1A and 5), and grown for approximately 40 h until the majority reached the young adult stage. Young adults were precipitated with a pear funnel (Figs. 1A and 6), washed, pelleted, and flash frozen in 1-ml aliquots.

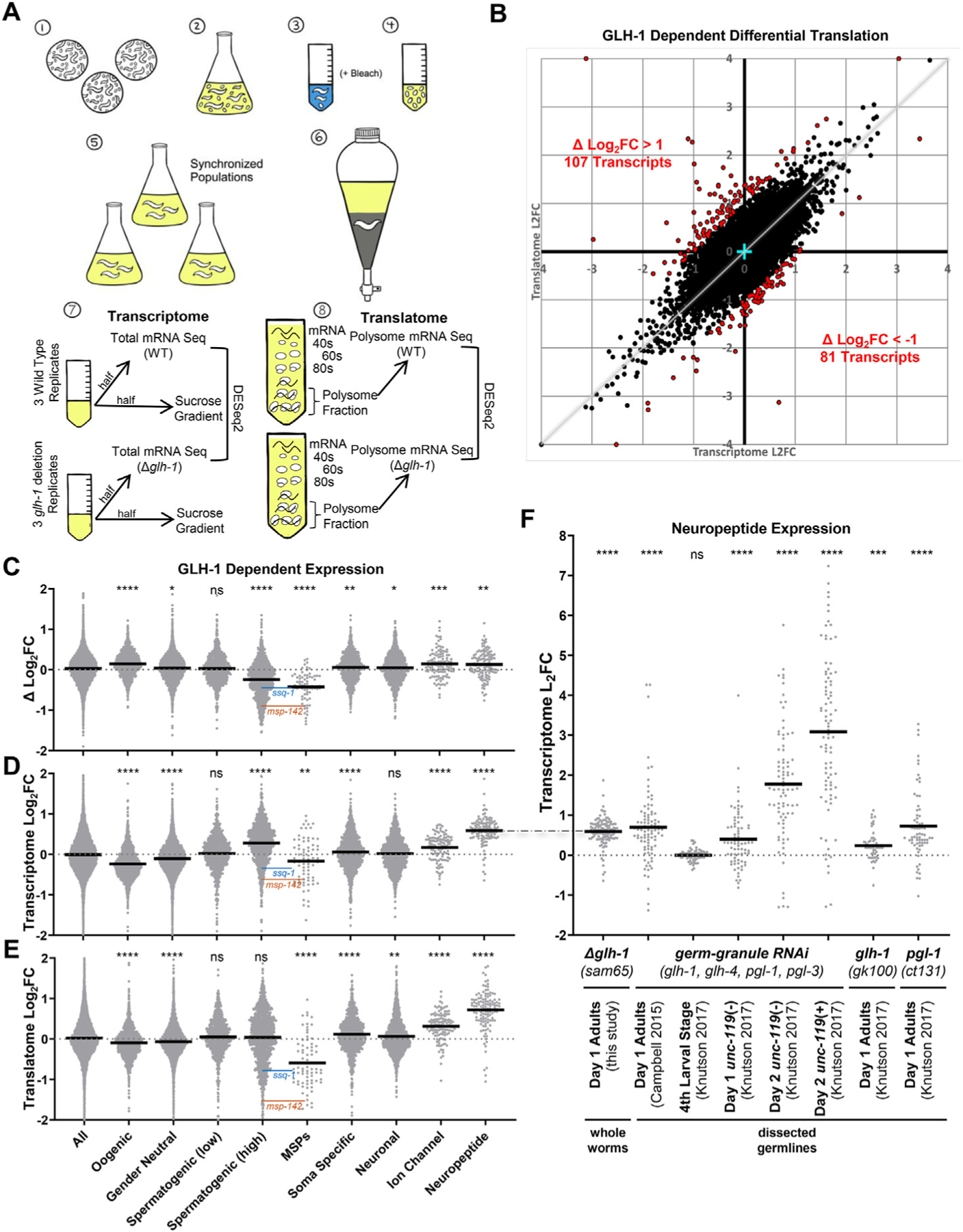

Fig. 1.

GLH-1 impact on the transcriptome and translatome. A) Schematic of expression profiling experiments. Starved plates (1) were used to inoculate S-media cultures containing freeze-dried OP50 (2). Following incubation at 20 °C, gravid adults were beach treated (3) to harvest embryos (4). Embryos were hatched overnight on unseeded plates to obtain a synchronized population and used to inoculate new S-media cultures containing freeze-dried OP50 (5). Following incubation at 20 °C, young adults were precipitated, washed, and flash-frozen (6). Lysates were prepared from the synchronized WT and Δglh-1 mutants. Half of the lysate was used for total mRNA isolation (7), while the other half was placed in a sucrose gradient for polysome fractionation (8). B) Log2(Fold Change) from total mRNA-seq (transcriptome, X-axis) plotted against the Log2(Fold Change) from polysome mRNA-seq (translatome, Y-axis). Red points indicate differentially translated transcripts where the ΔLog2FC (difference between transcriptome and translatome) was >1 (107 transcripts) or < −1 (81 transcripts). Four data points fell outside the boundaries of the graph and are shown on edge. Cyan cross marks 0,0. Grey diagonal indicates a 1 to 1 correlation between the transcriptome and translatome. Violin plots showing Log2(Fold Change) in C) translation efficiency (difference between transcriptome and translatome), D) transcriptome, and E) translatome in Δglh-1 mutants compared to WT. F) Violin plots showing Log2(Fold Change) of neuropeptide mRNA accumulation in this and other datasets. For C–F, bold horizontal line = mean, and significance from “all” shown as ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, ns p > 0.05. ssq-1 (blue) and msp-142 (orange) levels are indicated in the Spermatogenic (high) and MSP datasets. The dash-dot line connecting D to F indicates a duplication of the same Day 1 Adult data in both panels.

For each strain and replicate, pelleted worms were lysed by grinding in solubilization buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCL pH 8, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 200 μg ml−1 heparin, 400 U mL−1 RNAsin, 1 mM PMSF, 0.2 mg ml−1 cycloheximide, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate). Half of the sample was used for total RNA isolation (Figs. 1A and 7). The other half of the lysate was loaded onto a 10–50% sucrose gradient in high salt resolving buffer (140 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris–HCL pH 8, 10 mM MgCl2). Gradients were resolved by ultracentrifugation in a Beckman SW41Ti rotor at 38 000 × g at 4 °C for 2 h. Fractions of the gradients were continuously monitored at an absorbance of 254 nm using a Teledyne density gradient fractionator collecting the polysome fraction.

mRNA was isolated from both total and polysome associated halves of the lysate using a TruSeq RNAv2 kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality was assessed on an Allegiant 2100 Bio-analyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA), requiring an A260/A208 > 1.7 and RIN >8.0. All 12 samples were sent to the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) for sequencing using a KAPA stranded mRNA sequencing kit (Roche), followed by 75 cycles on the NextSeq HO Illumina sequencer.

2.3. Sequence analysis and data deposits

Final FASTQ data files were sent to the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratories Bioinformatics Core. Sequences were preprocessed with TrimGalore version 0.67, using default options (https://github.com/FeliXKrueger/TrimGalore). Quantification was performed with kallisto version 0.45.1 (Bray et al., 2016), using a custom target transcriptome that was based on the Ensembl release 105 (based on Wormbase Release 235), using the combined “cdna” and “ncrna” assigned transcript, and which also had two additional transcripts that correspond to the GLH-1-GFP fusion construct, and the associated GLH-1 deletion transcript. The resulting sample-specific expression files were joined into transcript- and gene-level expression matrixes using the R package tximport (Soneson et al., 2015), with a custom transcript-to-gene map that assigned the two GLH-1 constructs to the same gene as the endogenous GLH-1 (WBGene00001598). Differential expression analysis was carried out in R version 4.1.0 with the DESeq2 version 1.24.0. DESeq2 was also used to generate a rlog-matrix which was Z-transformed to normalize each gene across all samples. mRNA-seq datasets have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database under accession number GSE148737 (BioProject ID PRJNA625528).

For comparative visualization of read coverage on specific genes, the trimmed fastq files were aligned to the previously mentioned C. elegans Ensembl genome using the STAR aligner version 2.6.1b (Dobin et al., 2013), with a splice junction overhang of 100 nt. The resulting BAM files were converted to bigwig with bamCoverage version 3.6 from the DeepTools2 suite (Ramírez et al., 2016) for visualization in IGV version 2.11.2 (Robinson et al., 2011).

The STRING database (v11) (string-db.org) was used to visualize clustered protein-protein networks and perform the gene ontology analysis in Supplemental Table 1 (Szklarczyk et al., 2019, 2021).

Gene categories were defined using published datasets. Soma-specific genes include the dataset described and used in (Knutson et al., 2016, 2017; Rechtsteiner et al., 2010). Oogenic, gender neutral, and spermatogenic categories were described in (Ortiz et al., 2014). Neuronal genes and neuronal subclasses that include ion channels and neuropeptides were extrapolated from neuronal “threshold level 2” genes as defined in the CeNGEN (complete gene expression map of the C. elegans nervous system) (Taylor et al., 2021) Violin plots and unpaired t-test analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.4.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com.

2.4. Msp-142 and ssq-1 qRT-PCR

RNA extraction - Worms were grown on chicken egg plates at 20 °C and floated on 35% sucrose before flash freezing as pellets in liquid nitrogen with 14 mM E64 protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich), 4 mM Vanadyl-RNC RNase inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.2% Tween 20 detergent (Sigma Aldrich). Four worm pellets were ground using mortar and pestle. Powdered worms were melted on ice, and the lysate was extracted with Trizol (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. This was followed by 0.7 vol isopropanol precipitation. The resuspended precipitate was further extracted with phenol-chloroform-iso-amyl alcohol (25:24:1), and twice with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1), then ethanol precipitated. GlycoBlue (Invitrogen) was used as a co-precipitate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality and quantity were determined using NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer.

qRT-PCR - Reverse transcription was performed on 0.5 μg of total RNA in a 20 μl reaction with the iScript Adv cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate on an OPUS CFX-96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using Sso Fast Evagreen Super mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of msp-142 and ssq-1 mRNA (Supplemental Fig. 1E) was normalized to gpd-3 mRNA using ΔΔCT analysis.

2.5. Sperm counts

Synchronized young adults were fixed in M9 with 8% PFA for 1 h, washed 3x with PBS, 1X with 95% ethanol for 1 min, 3x with PBS, then mounted on a charged slide with mounting media containing DAPI. Sperm nuclei were imaged and counted in each spermatheca, 10 worms/strain as previously described (Rochester et al., 2017).

2.6. Fixation and immunostaining

Two fixation methods were used as previously described (Huggins et al., 2020; Min et al., 2016) with minor modifications. Briefly, to observe the expression of fluorescently labeled whole worms, they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min and further fixed with 70% ethanol. The specimens were stained with DAPI (Thermo Scientific, Germany, 62248) to stain DNA, and observed on a Leica Thunder Imager Live Cell microscope with an HC PL APO 63x/1.47 Oil CORR TIRF objective and DAPI, GFP, and TXR filter sets. Images were acquired with a Leica DFC9000 GT deep-cooled sCMOS camera and Leica LAS X imaging software. To observe the mitotic germ cells and progression of spermatogenesis in males, worms were dissected and fixed with 100% methanol at −20 °C for 10 min, followed by 100% acetone fixation at −20 °C for 10 min. The specimens were further counter-stained with DAPI to stain DNA. The following primary and secondary antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (1:500; Sigma, T9026), rabbit anti-phospho-histone H3 (Ser10) (1:500; EMD Millipore, 06–570), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500, Invitrogen, A32723), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500, Invitrogen, A32740).

2.7. Live imaging of fluorescently labeled worms

Transgenic male worms were placed into SM buffer (50 mM HEPES, 25 mM KCl, 45 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 5 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM Dextrose; pH 7.8) containing 0.2 mM levamisole on a GCP (0.2% w/v gelatin, 0.02% w/v chrome alum, 0.05% w/v poly-L-lysine)-coated glass slide. To extrude spermatids, 5–6 worms were dissected from each strain and covered with a coverslip for live imaging with the Leica Thunder Imager, objectives, and camera described above. Fixed exposure conditions were used on all strains. Using ImageJ, a fixed circular ROI was applied to each spermatid, and the measure tool was applied to obtain the integrated density. Mean pixel intensity was subtracted from the adjacent background to calculate the corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF = Integrated Density – (area of cell * mean background fluorescence).

2.8. Membranous organelle (MO) fusion assay

To visualize the fusion of sperm-specific MO with the plasma membrane, worms were dissected to release sperm and were placed into SM buffer (50 mM HEPES, 25 mM KCl, 45 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 5 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM Dextrose; pH 7.8) containing 20 μg/mL of FM 1–43 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), a lipophilic fluorescent dye that stains MO. FM 1–43 partitioned into the cell outer membranes and enabled MO fusion monitoring during sperm activation (Liau et al., 2013). Linear 0.55 μm profiles of MSP-142:mCherry expression across sperm were measured with ImageJ.

2.9. In vitro sperm activation

In vitro sperm activation was performed as previously described (Tajima et al., 2019) with minor modifications. L4 males were isolated on OP50-seeded NGM plates and cultured on the plates at 20 °C for 48 h in the absence of hermaphrodites. Then, 10 of the virgin males were transferred to 10 μl of SM buffer (50 mM HEPES, 25 mM KCl, 45 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 5 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM Dextrose; pH 7.8) with or without 200 μg/ml of proteinase K or 6 mM ZnCl2 on a glass slide. Spermatids were released by cutting the tails. After incubating at RT for 5 min, a coverslip was gently overlaid and sealed with Vaseline. Activation of spermatids to spermatozoa was observed at 63X magnification under Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy on the Leica Thunder Imager described above.

2.10. Sperm migration assay

To assay sperm migration, synchronized MSP:mCherry-tagged transgenic males were used for mating as previously described (Hoang and Miller, 2017) with minor modifications. Males mated with fog-2 females in a 10:1 ratio for 3 h. Mated fog-2 animals were subsequently transferred to new NGM plates and examined for the presence of fluorescence under a fluorescence microscope described above (n = 30 mated with WT males, n = 26 mated with Δglh-1 males). Fluorescence and DIC images of the uterus were divided into three equal zones to analyze MSP-142:mCherry distribution.

3. Results

To examine the impact of GLH-1 on translational efficiency in C. elegans, mRNA-seq was performed on polysome and total mRNA fractions from three biological replicates of synchronized young adult populations from wild-type (WT) and glh-1 deletion (Δglh-1) strains (Fig. 1A). Our traditional approach of profiling gene expression in dissected germlines yields insufficient starting material for polysome gradients, so lysates for these studies were prepared from whole worms, which are half-comprised of germ cells. The WT and Δglh-1 strains have been previously described (Marnik et al., 2019). Briefly, the WT-designated strain was generated using CRISPR/Cas9 to place a GFP:3xFLAG tag just before the stop codon of the endogenous glh-1 gene. The Δglh-1 strain was generated from this WT-designated strain using CRISPR/Cas9 to make a precision deletion of glh-1, leaving GFP:3xFLAG expressed from the endogenous glh-1 promoter and 3ʹ end sequences. Libraries were created by placing unique adapters on the three replicates of WT and Δglh-1 from total and polysome fractions (12 samples) and sequenced together. Differential expression between WT and Δglh-1 replicates was determined using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) for both total mRNA (transcriptome) and polysomal mRNA (translatome), and the Log2(Fold Change) plotted on the x and y axis, respectively (Fig. 1B, Supplemental Table 1). mRNAs deviating from the correlation between transcriptome and translatome are identified by the difference in the fold change (Δ Log2FC). Transcripts with a Δ Log2FC greater than 1 or less than −1 are shown in red (Fig. 1B). In principle, a high Δ Log2FC would indicate mRNAs whose translation efficiency decreases with GLH-1 (107 transcripts >1), whereas a low Δ Log2FC would indicate mRNAs whose translation efficiency increases with GLH-1 (81 transcripts < −1).

The 107 mRNAs whose translation efficiency is decreased by the presence of GLH-1 were run through the STRING database (v11.5) to look for network clustering (Supplemental Table 1, (Szklarczyk et al., 2021). Patterns were not observed for most of these mRNAs. Enrichment of a subset of replication-dependent histones was observed (false discovery rate = 3.07e-08), which could point to proliferative defects in Δglh-1 mutants (see Fig. 3D). Four out of six hsp-16 mRNAs were also observed in these 107 mRNAs (false discovery rate = 2.81e-05), which point to Δglh-1 mutants exhibiting increased cellular stress. On the other end of the spectrum, most mRNAs whose translation efficiency is increased by GLH-1 are co-expressed and form one large network cluster (Supplemental Table 1). Components of this cluster contain major sperm protein (MSP) domains and protein kinases that are primarily co-expressed during spermatogenesis.

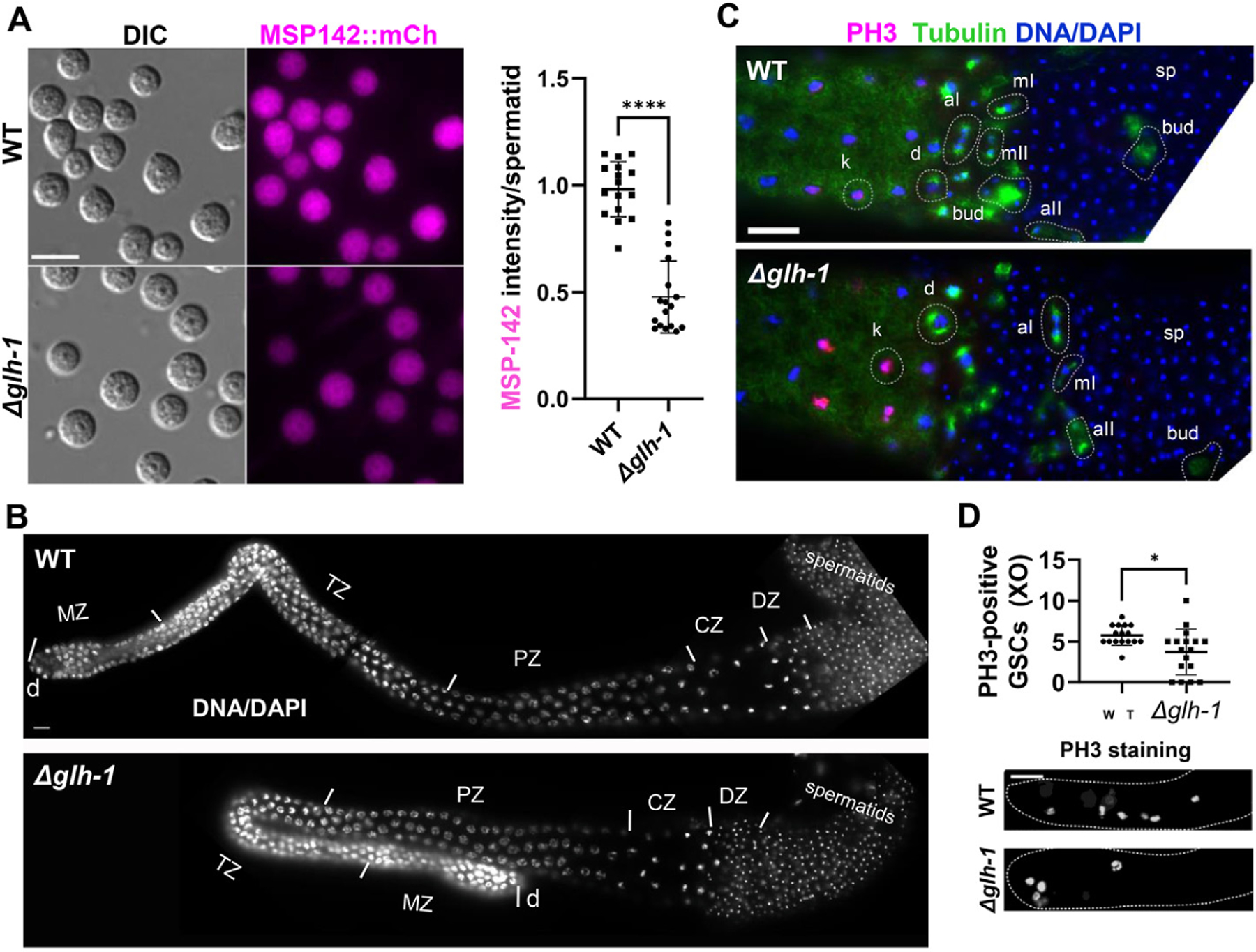

Fig. 3.

Male germline dependence on GLH-1. A) Fluorescence live images of spermatids dissected from MSP-142:mCherry males in WT and Δglh-1 mutants: scale bar, 8 μm. The plot shows the MSP-142:mCh fluorescence intensity in spermatids from WT and Δglh-1 mutant males. n = 16 for WT, n = 17 for Δglh-1. Error bars indicate s.d. ****, p < 0.0001. B) DAPI-stained YA male dissected gonads labeled by the following developmental stages: d, distal end. MZ, mitotic zone. TZ, transition zone. PZ, pachytene zone. CZ, condensation zone. DZ, division zone: scale bar, 10 μm. C) Spermatogenesis stages are similar in WT and Δglh-1 mutant males. Meiosis I and II were observed in dissected WT (n = 20) and Δglh-1 mutant (n = 20) male gonads after co-immunostaining with anti-PH3 (magenta), anti-α-tubulin (green), and DAPI (blue). k, karyosome. d, diakinesis. mI, metaphase I. aI, anaphase I. mII, metaphase II. aII, anaphase II. bud, budding spermatid. sp, spermatid: scale bar, 10 μm. D) Quantification of PH3-positive germ cells in distal gonadal ends in WT (n = 16) and Δglh-1 mutant (n = 17) male gonads. Error bars indicate s.d. *, p < 0.05. Representative images are shown. Dashed lines indicate the shape of gonad arms: scale bar, 20 μm.

Spermatogenic genes in C. elegans are not thoroughly annotated in current gene ontology databases. One available dataset (Ortiz et al., 2014) uses the ratio of fem-3(q96gf) (male) to fog-2(q71) (female) expression in dissected germlines to define oogenic, gender-neutral, and spermatogenic subsets. We further separated the defined spermatogenic mRNAs in this dataset into those with high (>5) and low (<5) fem-3::- fog-2 ratios based on a natural, bimodal distribution (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Compared to all genes in our analysis, a significant increase in the translational efficiency (positive Δ Log2FC) of oogenic genes is observed in Δglh-1 mutants, which partially compensates for the decreased accumulation of oogenic mRNAs (Fig. 1C–E). While there was little change in the Δ Log2FC of gender-neutral or spermatogenic (low) mRNAs, the translational efficiency of spermatogenic (high) genes drops in Δglh-1 mutants, partially compensating for the increased accumulation of spermatogenic (high) mRNAs (Fig. 1C–E). It was previously demonstrated that simultaneous depletion of four core germ-granule components (PGL-1, PGL-3, GLH-1, and GLH-4) by RNAi induces spermatogenic gene expression in one-day-old adult germlines, and then soma-specific and neuronal genes in two-day-old adult germlines (Campbell and Updike, 2015; Knutson et al., 2017; Updike et al., 2014). Therefore, we also looked at transcriptional and translational changes in soma-specific and neuronal subsets in our one-day-old adult Δglh-1 mutants, again observing only subtle changes at this early stage (Fig. 1C–E, Supplemental Fig. 1B). Taken together, GLH-1 loss leads to an average decrease in oogenic mRNAs and an average increase in spermatogenic (high) mRNAs in one-day-old adults, reflecting our previous observations with germ-granule RNAi. But here, we find that these changes in mRNA accumulation are compensated by altered translational efficiency, thereby reducing their impact on the germline.

mRNAs encoding MSP-domain proteins are one exception to compensatory feedback we see with the expression of oogenic and spermatogenic (high) gene sets. Because MSP-domain proteins were enriched in the 81 mRNAs with a Δ Log2FC < −1, we profiled the expression of all 72 annotated MSP-domain-containing proteins in our sequencing analysis. Unlike the increased accumulation of spermatogenic (high) mRNAs in Δglh-1 mutants, MSP mRNA abundance is decreased (Fig. 1D), and this was accompanied by a further reduction in MSP mRNA translation (Fig. 1E) and translation efficiency (Fig. 1C, Supplemental Fig. 1B). The genome browser expression profile of msp-142 from total mRNA and polysome-associated fractions is an example showing a more substantial decrease in polysome-associated mRNAs in Δglh-1 mutants (Supplemental Fig. 1C). This pattern is reflected with another spermatogenic (high) mRNA, ssq-1, which does not encode an MSP domain (Supplemental Fig. 1D). As expected, both msp-142 and ssq-1 transcripts are increased in a male-enriched him-5 background, but to a lesser extent in Δglh-1; him-5 nematodes, showing the presence of GLH-1 further increases the accumulation of these mRNAs (Supplemental Fig. 1E).

Another exception to compensatory feedback models can be observed in subsets of neuronal genes in Δglh-1 mutants. Modest increases in soma-specific and neuronal genes were observed in the transcriptome and translatome of these animals. But, neuropeptides were the most significantly enriched (false discovery rate = 1.05e-10) in the translatome of Δglh-1 mutants. Therefore, we profiled the expression of other neuronal subsets as defined by the CeNGEN gene expression map of the C. elegans nervous system (Taylor et al., 2021). Δglh-1 mutants increased the accumulation of mRNAs encoding ion-channels and neuropeptides, and this was accompanied by enrichment of these mRNAs in the translated polysome fraction (Fig. 1C–E, Supplemental Fig. 1B). To see if the enrichment was evident but missed in previous expression profiling experiments of dissected germlines following germ-granule RNAi, we re-examined neuropeptide mRNA accumulation in these published datasets (Fig. 1F). In each case, the accumulation of neuropeptide mRNAs was significantly higher in dissected germlines from day one adults following germ-granule RNAi (Campbell and Updike, 2015; Knutson et al., 2017). Moreover, the neuropeptide mRNAs progressively increased in dissected germlines from the fourth larval stage (no change) to two-day-old adults, and further increased when germ cells expressed a pan-neuronal unc-119:GFP reporter (Knutson et al., 2017 dataset). Significant increases were also observed when the neuropeptide subset was plotted against expression profiles of dissected germlines from glh-1 and pgl-1 mutants (Fig. 1F) (Knutson et al., 2017). These findings are consistent and show, for the first time, that neuropeptides become ectopically expressed during the early phase of somatic reprogramming that ensues after germ granules are compromised. The mechanisms behind the reduced accumulation and translation of MSP-domain encoding mRNAs or the increased accumulation and translation of the specified neuronal subsets in Δglh-1 mutants are currently unknown.

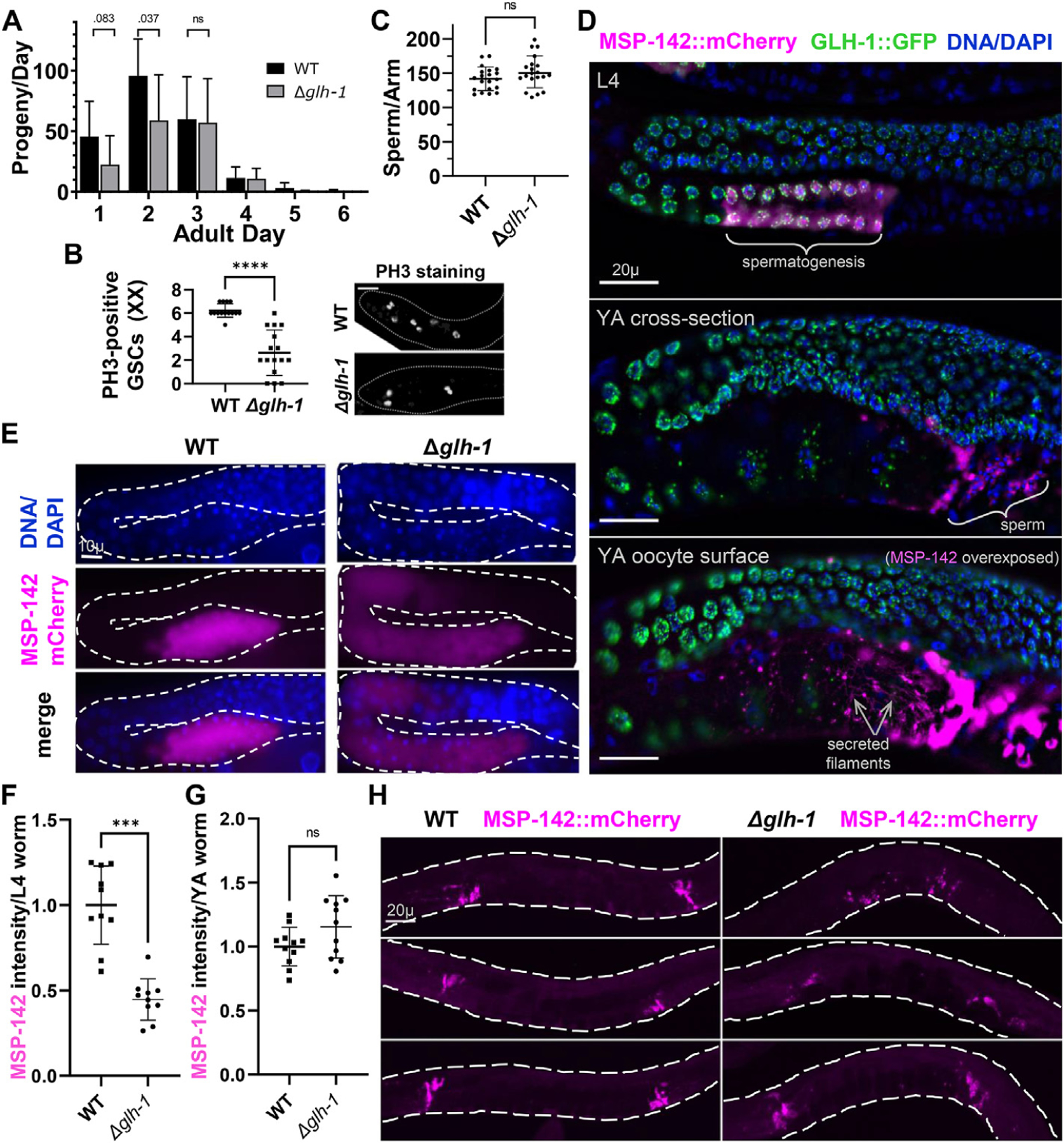

The redundancy of GLH-1 with its paralogs (GLH-2 and GLH-4) makes the analysis of Δglh-1 advantageous because the germline remains healthy, minimizing the opportunity for secondary effects to cause expression changes. Given the observed impact of GLH-1 on MSP-domain encoding mRNAs, we performed an in-depth analysis of germline phenotypes in Δglh-1 animals. We previously reported a 14% reduction (p < 0.0001) in the fertility of Δglh-1 compared to WT at permissive temperature (Marnik et al., 2019). Further analysis revealed that brood differences occur within the first two days of egg-laying (Fig. 2A). Part of the reduction can be accounted for by a 2.3-fold decrease in PH3-positive (proliferating) germ cells in Δglh-1 mutants (Fig. 2B). Differences in total and polysome-associated mRNA profiles suggested that reduced broods may also reflect defects in spermatogenesis. In fact, glh-1 loss-of-function mutants grown at the restrictive temperature of 26 °C often do not have sperm (Spike et al., 2008). To investigate this at the permissive temperature of 20 °C, we counted the number of sperm in the spermatheca of young adult worms and found no difference between WT and Δglh-1 mutants. These results suggest that at 20 °C, the absence of GLH-1 does not impact spermatogenesis (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

GLH-1 impact on fertility and MSP-142 expression. A) Self-fertility of hermaphrodites in WT and Δglh-1 mutants during adulthood. B) Quantification of PH3-positive germ cells in distal gonadal ends in WT (n = 14) and Δglh-1 mutant (n = 16) hermaphrodite gonads. Fluorescence images of distal gonadal ends in WT and Δglh-1 mutant gonads immunostained with the anti-PH3 antibody. Representative images are shown. The dashed lines indicate the shape of gonad arms: scale bar, 20 μm. C) Quantification of the number of DAPI-stained sperm in WT Δglh-1 mutant hermaphrodites. D) GLH-1:GFP and MSP-142:mCherry expression in L4-stage and young adult (YA) stage animals. Expression of MSP-142 at the YA stage. Gonads were fixed and counter-stained with DAPI (blue): scale bars, 20 μm. E) MSP-142:mCherry expression in L4 stage WT and Δglh-1 mutant animals. Gonads were fixed and counter-stained with DAPI (blue): scale bar, 10 μm. F and G) Quantification of MSP-142:mCherry intensity in WT (n = 10 for F, n = 11 for G) and Δglh-1 mutant (n = 10 for F, n = 11 for G) L4 and YA stage animals. H) Representative images of MSP-142:mCherry in WT and Δglh-1 mutant young adults: scale bar, 20 μm. Error bars indicate s.d., ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, ns p > 0.05.

An mCherry:V5 tag was placed on endogenous MSP-142 in WT and Δglh-1 worms to visualize differences in MSP expression. This translational reporter begins expressing during spermatogenesis in L4-staged hermaphrodites (Fig. 2D). It is later observed in the cytoplasm of spermatids, in the pseudopod ends of activated sperm, and in secreted filaments surrounding the most proximal oocytes, reflecting MSP expression patterns previously reported (Roberts et al., 1986). In L4-staged animals, MSP-142:mCherry germline expression expands more distally into developing oocytes (Fig. 2E). This reflects the expansion of MSP transcripts into oocytes previously detected by in situ hybridization following germ-granule RNAi (Campbell and Updike, 2015). However, the expression intensity of MSP-142:mCherry is lower in Δglh-1 worms, reflecting the decrease of msp-142 mRNA observed in the polysome fraction (Fig. 2E and F). This difference in MSP-142:mCherry expression between WT and Δglh-1 mutants is no longer evident in young adult hermaphrodites (Fig. 2G and H), where individual spermatids are condensed in the spermatheca and harder to visualize individually.

To better visualize expression differences at the cellular level, spermatids were dissected from WT and Δglh-1 males, and MSP-142:mCherry expression intensity was quantified. While sperm from both WT and Δglh-1 males express MSP-142:mCherry, expression is lower when glh-1 is deleted (Fig. 3A). All developmental zones of mitosis and meiosis were comparable between WT and Δglh-1 mutant males, as visualized in DAPI-stained morphologies in each germline (Fig. 3B). Moreover, co-immunostaining with anti-pH3 and anti-α-tubulin antibodies revealed the presence of karyosomes, diakinesis, metaphase, anaphase, spermatid budding, and mature spermatids in both WT and Δglh-1 mutant males (Fig. 3C)(Shakes et al., 2009). Anti-pH3 staining was also examined in the distal end of male germlines to estimate the rate of mitosis in germline stem cells. As observed in hermaphrodites, a significant but variable mitotic decrease was confirmed in Δglh-1 males (Fig. 3D). While all developmental zones of male and hermaphrodite germlines are present in the absence of GLH-1, germline stem cell proliferation and MSP-142:mCherry expression are reduced, the latter reflecting the decreased expression of MSPs in the transcriptome and translatome of Δglh-1 mutants.

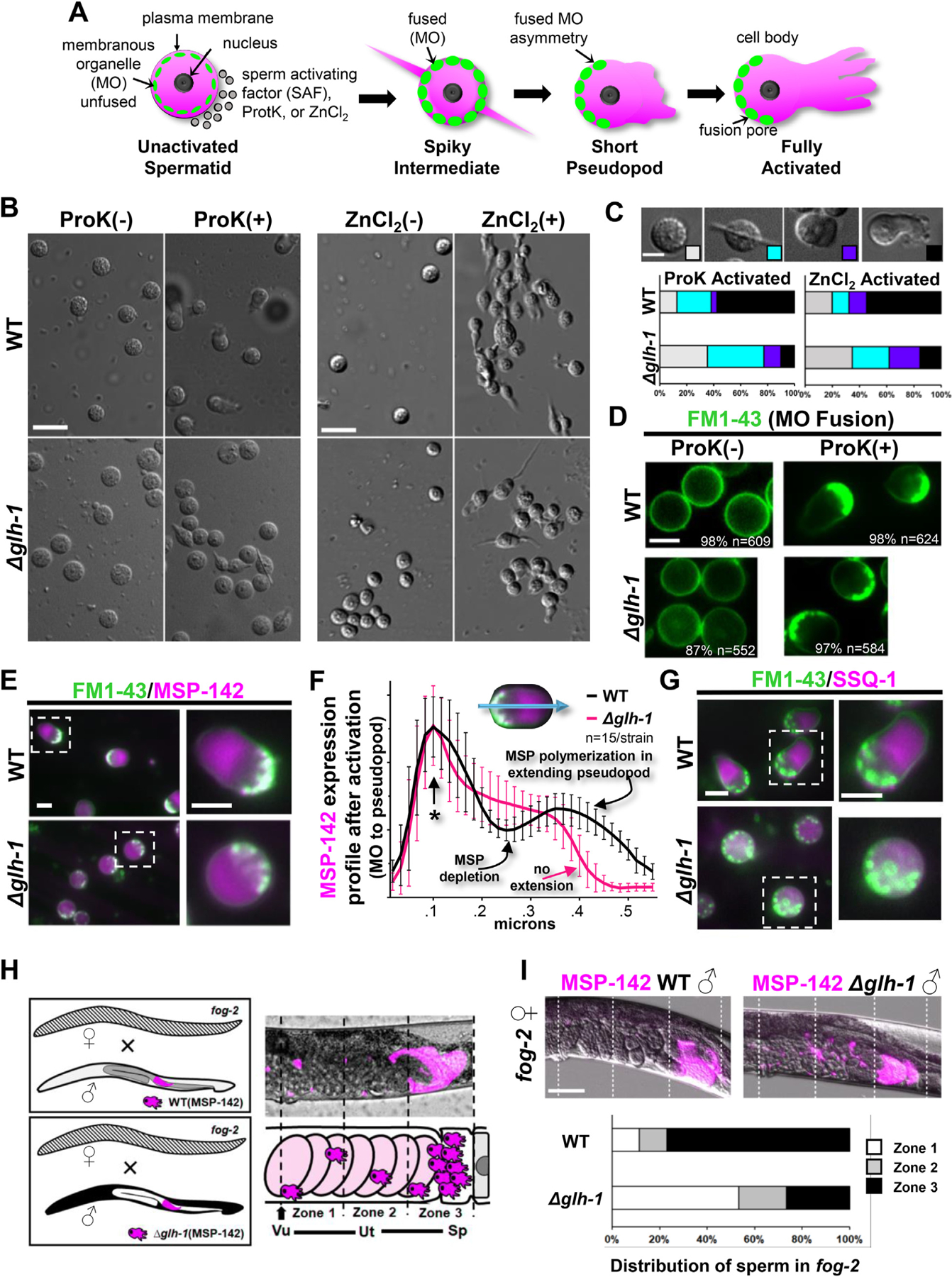

We next asked how the decrease in MSP expression in Δglh-1 mutants impacts membranous organelle (MO) fusion and sperm activation. Sperm activating factors, such as Proteinase K (ProK) and ZnCl2, transition the morphology of round spermatids to adopt a spikey and irregular shape as an intermediate phase before spermatozoa extend pseudopods and become motile (Fig. 4A)(Singaravelu and Singson, 2011). Upon exposure to ProK and ZnCl2, fewer spermatids were fully activated in Δglh-1 mutants, and many failed to progress through the spikey and irregular-shaped intermediate phases (Fig. 4B and C). The membrane probe FM1–43 fluoresces when MOs fuse to the plasma membrane during spermiogenesis (Washington and Ward, 2006). Staining shows that MO fusion is normal in both WT and Δglh-1 animals. Although activation does initiate in Δglh-1 spermatids, there is a defect that coincides with pseudopod extension (Fig. 4D). It is known that MSPs migrate asymmetrically to polymerize and drive pseudopod extension, so we examined the distribution of MSP-142:mCherry in WT and Δglh-1 sperm following activation (Fig. 4E). MSP-142 is distributed into the pseudopod but to a lesser extent in Δglh-1 sperm (Fig. 4F). To determine if this redistribution defect was observed in a spermatogenic (high) non-MSP reporter, an N-terminal V5:mCherry tag was placed in-frame and upstream of endogenous ssq-1 in both WT and Δglh-1 backgrounds. The distribution of mCherry:SSQ-1 also showed that asymmetric distribution was impacted (Fig. 4G). These results suggest that sperm initiate activation, but pseudopod functionality in Δglh-1 animals is compromised.

Fig. 4.

GLH-1 impact on sperm activation. A) Activation of spermatozoa during C. elegans spermiogenesis. Treatment of C. elegans spermatids with spermatid-activating factors (SAFs) stimulates the round spermatids to extend pseudopods, transforming them into motile spermatozoa. Membranous organelles (MOs) fuse with the plasma membrane to release contents into the extracellular space. B) Live images of sperm after in vitro activation by Proteinase K (ProK) or ZnCl2 treatment from WT and Δglh-1 mutant males. Representative images are shown: scale bar, 8 μm. C) Categorized morphologies of sperm after in vitro activation by ProK or ZnCl2. Stages were defined by the morphology of sperm and its pseudopod extension observed by DIC microscope: scale bar, 4 μm. Quantification of sperm of WT (n = 118 for ProK activation, n = 146 for ZnCl2 activation) and Δglh-1 mutant (n = 198 for ProK activation, n = 199 for ZnCl2 activation). D) Live fluorescent images of sperm from WT and Δglh-1 mutant males stained with FM1–43 to observe MOs after in vitro activation by ProK. Representative images are shown, with the percent and number of sperm with the pictured FM1–43 distribution: scale bar, 4 μm. E) Live fluorescent images of sperm from WT and Δglh-1 mutant males stained with FM1–43 after in vitro activation by ProK treatment: scale bar, 4 μm. F) Average expression intensity profiles (ImageJ) of MSP-142:mCherry in sperm stained with FM1–43 following in vitro activation by ProK. Error bars indicate s.d. An asterisk marks the FM1–43 stained end of activated sperm, where plot profiles were aligned: scale bar, 4 μm. G) Live fluorescent images of sperm stained with FM1–43 after in vitro activation by ProK treatment on SSQ-1:mCherry from WT and Δglh-1 mutant males: scale bar, 4 μm. H) Scheme of sperm migration assay. WT and Δglh-1 mutant MSP-142:mCherry expressing males were crossed to fog-2 females. The uterus was divided into 3 zones from the vulva (zone 1, arrow) to the spermatheca (zone 3). Vu, vulva. Ut, uterus. Sp, spermatheca. I) Quantification of WT and Δglh-1 mutant male sperm migration in fog-2 females (n = 26 for WT male, n = 30 for Δglh-1 mutant male). The fluorescent intensity of each zone was measured and calculated proportionally against the total fluorescent intensity of all three zones: scale bar, 50 μm.

Spermatozoa are swept into the uterus during ovulation and use their pseudopods to crawl to the spermatheca for further opportunity to fertilize eggs (Ellis and Stanfield, 2014). In male/hermaphrodite matings, pseudopods also allow male sperm to crawl from the vulva through the uterus into the spermatheca. To test whether pseudopod functionality is compromised in Δglh-1 animals, fog-2 females were crossed with MSP-142:mCh expressing males from WT and Δglh-1 worms (Fig. 4H). MSP-142:mCh expression was examined in three equal-sized zones from the vulva to the distal end of the spermatheca. Sperm expressing wild-type GLH-1 crawl to the spermatheca, while a greater proportion of Δglh-1 mutants have sperm near the vulva (Fig. 4I). These results suggest that increased accumulation of MSP-encoding transcripts in the presence of GLH-1 ensures the mobility of activated sperm and may explain the absence of sperm in glh-1 mutants grown at 26 °C if non-motile sperm purged during ovulation and unable to crawl back.

4. Discussion & conclusions

The somatic reprogramming previously reported with germ-granule RNAi most consistently induced pan-neuronal reporter expression and neurite-like extensions in germ cells (Knutson et al., 2017; Updike et al., 2014). Nearly one-third of somatic cells in C. elegans are neurons, which may make neuronal differentiation a logical default. A default model for neural induction has been well established for stem cells and animal development (reviewed in Cao, 2022). Moreover, unsolicited induction of neuronal fates in the C. elegans germline can be observed in mex-3 glh-1 (Ciosk et al., 2006), spr-5 let-418 (Käser-Pébernard et al., 2014), and wdr-5.1 (Robert et al., 2014) backgrounds (reviewed in Marchal and Tursun, 2021) Our data suggest that an initial step in somatic reprogramming when core germ-granule components are compromised includes a global increase in neuropeptide expression. The increase is modest but nearly universal among neuropeptide mRNAs in the total and polysome fractions of Δglh-1 mutants (Fig. 1C–E) and also consistent when examined in previously published datasets from isolated germlines following germ-granule depletion (Fig. 1F) (Campbell and Updike, 2015; Knutson et al., 2017). It is unclear how neuropeptides might drive somatic reprogramming in Δglh-1 mutants, as they are markers of terminal neuron specification. One model is that neuropeptide expression introduces noise, or stochastic variations in gene expression, to prime germ cells for somatic reprogramming. Transcriptional noise may increase responsiveness to fate-determining stimuli and has been shown to potentiate cell fate transitions in stem cells (Desai et al., 2021). Given the low and basal levels of neuropeptide transcripts in wild-type germlines, an alternative model is that the change in neuropeptide expression is simply the easiest readout to detect when default neuronal differentiation is induced and does not necessarily represent a functional step in somatic reprogramming. Unfortunately, the observed increase following germ-granule depletion is not likely sufficient to detect with fluorescent reporters of neuropeptide expression – unless it represents stochastic expression in individual germ cells. It will be interesting to see whether that is the case and if the increase in neuropeptide expression is specific to the loss of core germ granule proteins like GLH-1 or shared in other genetic perturbations that induce somatic reprogramming of the C. elegans germline.

Loss of GLH-1 had a very different effect on the expression of MSPs. Decreased expression of MSP-142:mCherry in Δglh-1 mutants is uniformly observed in developing germ cells and in spermatids. While the presence of GLH-1 suppresses the accumulation of spermatogenic transcripts during oocyte differentiation, it selectively promotes the accumulation and translation of MSP-domain-encoding mRNAs during spermatogenesis. The mechanisms behind the selectivity of GLH-1 for these transcripts merit further investigation. The helicase activity of GLH-1 could linearize conserved structural motifs in MSP-domain-encoding transcripts, making them accessible to translation machinery or small RNA processing. Vasa helicases are thought to exhibit non-sequence-specific RNA binding, but GLH CLIP assays suggest mRNA target specificity is conferred, at least in part, through GLH-associated Argonaute pathways (Dai et al., 2022). The selective silencing of spermatogenic genes is known to be mediated through piRNA pathways that interact with GLH-1 (Cornes et al., 2022). Translational silencing by GLH-1-bound microRNAs has also been demonstrated and could be a mechanism for selectivity (Dallaire et al., 2018). Precursory attempts to identify moieties (correlative small RNA and microRNA binding sites, sequence conservation, structural features) capable of distinguishing MSP-domain encoding mRNAs from other germline-expressed or spermatogenic mRNAs showed no strong correlations, but do not exclude the possibility that these moieties exist. Here, we show that lower levels of MSP expression impact pseudopod extension following sperm activation in Δglh-1 mutants, leading to subtle reductions in fertility even at the permissive temperature. Therefore, one of the primary impacts of loss or depletion of GLH-1 can be observed on sperm motility and function.

Our approach aimed to identify early events during somatic reprogramming of the germline that could be separated from other pleiotropic defects, such as atrophied germlines and germ cell loss. By looking for changes in polysomal-associated mRNAs, we also sought to uncover defects in Δglh-1 mutants that were masked (or caused) by changes in translational efficiency. We found that early reprogramming events include enhanced expression of neuropeptides and a decrease in MSP expression. The bulk of these changes are correlative at the level of transcription and translation. In fact, Δglh-1 mutants showed surprisingly little evidence to support a general role for GLH-1 in the selective activation or repression of translation that was independent of mRNA accumulation. Therefore, the functional relevance of GLH-1’s association with translation initiation components requires further exploration. What we did observe is that changes in oogenic and spermatogenic (high) mRNA levels from total mRNA sequencing are dampened in the polysome fraction, showing the capacity of systems to reduce or compensate for fluctuations in mRNA abundance of some gene subsets at the level of their translation. This compensation was not observed for changes in MSP- and neuropeptide-encoding transcripts. The reason for discrimination among mRNA types remains unclear but may depend on how GLH-1 interfaces with translation initiation components as mRNAs pass from germ granules and into the cytoplasm for translation.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| Reagent or resource | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin | Sigma | T19026 |

| rabbit anti-phospho-histone H3 (Ser10) | EMD Millipore | 06-570 |

| Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG | Invitrogen | A32723 |

| Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG | Invitrogen | A32740 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli OP50 (freeze dried) | LabTIE | OP50 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| FM 1–43 | Invitrogen/Thermo | T3163 |

| Levamisole | Sigma-Aldrich | L9756 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| TruSeq RNA Library Prep Kit v2 | Illumina | RS-122-2001 |

| KAPA Stranded mRNA-seq Kit | Roche | 07962193001 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| NCBI GEO GSE148737 (BioProject ID PRJNA625528) | ||

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| C. elegans strain DUP64 | Updike Lab | |

| C. elegans strain DUP144 | Updike Lab | |

| C. elegans strain DUP206 | Updike Lab | |

| C. elegans strain DUP210 | Updike Lab | |

| C. elegans strain DUP211 | Updike Lab | |

| C. elegans strain DUP216 | Updike Lab | |

| C. elegans strain KX197 | Keiper Lab | |

| C. elegans strain KX198 | Keiper Lab | |

| C. elegans strain KX199 | Keiper Lab | |

| C. elegans strain KX200 | Keiper Lab | |

| C. elegans strain JK574 | CGC | |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| msp-142 crRNA (ATTTATTTAGAAGTTCTCAT …) | IDT | |

| ssq-1 crRNA (TCCGAAATAGGCAGATGTCA …) | IDT | |

|

msp-142::mCherry::V5 HR repair template (ATTGGATACGGTATCAAGACCACCAACATGAAGAGACTTGGAGTTGATCCACCATGTGGAGTTCTCG ACCCAAAGGAAGCAGTGCTTCTGGCAGTTTCCTGCGATGCATTTGCTTTTGGACAAGAAGACACCAACAACGACCGTATCACCGTCGAAT GGACCAACACCCCGGATGGAGCTGCCAAGCAGTTCCGCCGCGAGTGGTTCCAGGGAGATGGTATGGTCCGTCGCAAGAATCTGCCGA TCGAATATAACCCAGGAGCATCGGGAGCCTCAGGAGCATCGGTCTCAAAGGGTGAAGAAGATAACATGGCAATTATCAAGGAGTTCATGCG TTTCAAGGTCCACATGGAGGGATCCGTCAACGGACACGAGTTCGAGATCGAGGGAGAGGGAGAGGGACGTCCATACGAGGGAACCCAAACCGCC AAGCTCAAGGTAAGTTTAAACATATATATACTAACTAACCCTGATTATTTAAATTTTCAGGTCACCAAGGGAGGACCACTCCCATTCGCCTGGGACAT CCTCTCCCCACAATTCATGTACGGATCCAAGGCCTACGTCAAGCACCCAGCCGACATCCCAGACTACCTCAAGCTCTCCTTCCCAGAGGGATTCAAGTG GGAGCGTGTCATGAACTTCGAGGACGGAGGAGTCGTCACCGTCACCCAAGACTCCTCCCTCCAAGACGGAGAGTTCATCTACAAGGTCAAGCTCCGTGGA ACCAACTTCCCATCCGACGGACCAGTCATGCAAAAGAAGACCATGGGATGGGAGGCCTCCTCCGAGCGTATGTACCCAGAGGACGGAGCCCTCAAGGGAGA GATCAAGCAACGTCTCAAGCTCAAGGACGGAGGACACTACGACGCCGAGGTCAAGACCACCTACAAGGCCAAGAAGCCAGTCCAACTCCCAGGAG CCTACAACGTCAACATCAAGCTCGACATCACCTCCCACAACGAGGACTACACCATCGTCGAGCAATACGAGCGTGCCGAGGGACGTCACTCCACCGGA GGAATGGACGAGCTCTACAAGGGAGCCTCAGGAAAGCCAATCCCAAACCCACTTCTTGGACTCGACTCCACCTGAGAACTTCTAAATAAATATTGTTTTA CCTCATTGTTTGTTAATTTTTAGGATTAAAATACATTATCTGACTAGTAGCCCATTCTCCCAATATGGAGTTGAAAGGTGCCGCCAAATTTGGCGGTTT CTGAGACCTTGCTATTTCTCAGTGA) |

||

| V5::mCherry::ssq-1 HR repair template (ATATTCGAACTTTTCTTCGAACCGTGAGATCAGCCATGGGAAAGCCAATCCCAAACCCACTTCTTGGACTCGACTCCACCG GAGCCTCAGTCTCAAAGGGTGAAGAAGATAACATGGCAATTATCAAGGAGTTCATGCGTTTCAAGGTCCACATGGAGGGATCCGTCAACGGACACGAGTTCGAGA TCGAGGGAGAGGGAGAGGGACGTCCATACGAGGGAACCCAAACCGCCAAGCTCAAGGTAAGTTTAAACATATATATACTAACTAACCCTGATTATTTAAATTTTCAGGTCACC AAGGGAGGACCACTCCCATTCGCCTGGGACATCCTCTCCCCACAATTCATGTACGGATCCAAGGCCTACGTCAAGCACCCAGCCGACATCCCAGACTACCTCAAGCTCTCCTT |

IDT | |

| CCCAGAGGGATTCAAGTGGGAGCGTGTCATGAACTTCGAGGACGGAGGAGTCGTCACCGTCACCCAAGACTCCTCCCTCCAAGACGGAGAGTTCATCTACAAGGTCAA GCTCCGTGGAACCAACTTCCCATCCGACGGACCAGTCATGCAAAAGAAGACCATGGGATGGGAGGCCTCCTCCGAGCGTATGTACCCAGAGGACGGAGCCCTCAAG GGAGAGATCAAGCAACGTCTCAAGCTCAAGGACGGAGGACACTACGACGCCGAGGTCAAGACCACCTACAAGGCCAAGAAGCCAGTCCAACTCCCAGGAGC CTACAACGTCAACATCAAGCTCGACATCACCTCCCACAACGAGGACTACACCATCGTCGAGCAATACGAGCGTGCCGAGGGACGTCACTCCACCGGAGGAAT GGACGAGCTCTACAAGGGAGCATCGGGAGCCTCAGGAGCATCGACATCTGCCTATTTCGGAGTTGCCGGCGGGAGTAA) |

IDT | |

| gpd-3 Forward (for qRT-PCR): | ||

| GATCTCAGCTGGGTCTCTT | IDT | |

| gpd-3 Reverse (for qRT-PCR): | ||

| TCCAGTACGATTCCACTCAC | IDT | |

| msp-142 Forward (for qRT-PCR): | ||

| CCTGCGATGCATTTGCTTTT | IDT | |

| msp-142 Reverse (for qRT-PCR): | ||

| ACAATATTTATTTAGAAGTTCTCATGG | IDT | |

| ssq-1 Forward (for qRT-PCR): | ||

| TTTTCTTCGAACCGTGAGATCAG | IDT | |

| ssq-1 Forward (for qRT-PCR): | ||

| CTGGGGGTGGTGCACCGG | IDT | |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Fiji/ImageJ | NIH | |

| IGV | Broad Institute | |

| STRING DB | String-DB.org | |

| GraphPad Prism 9.4.0 for Windows | GraphPad Software | |

| TrimGalore version 0.67 | https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore | |

| Other |

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lisa Petrella at Marquette University and Dr. Emily Spaulding at MDIBL for their critical manuscript readings. We also thank Heidi Munger at the JAX Genome Technologies Laboratory for providing sample preparation and mRNAseq services. Some of the strains for this study were provided by the CGC, funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Funding

J.D.R was supported by NIH T32 fellowship [GM132006]. D.L.U. is supported by NIH R01 [GM113933]. J.H.G. and the Bioinformatics Core at the MDI Biological Laboratory are supported through NIH P20 [GM103423] and P20 [GM104318]. J.A.R. is supported by NIH P20 [GM104318]. B.D.K. is supported by NSF grants [MCB 213973] and [MCB 217104].

Footnotes

Data statement

Raw sequence files have been deposited at NCBI GEO GSE148737 (BioProject ID PRJNA625528). C. elegans strains generated for this study and their accompanying sequence files are available by request.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2022.10.003.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Bezares-Calderon LA, Becerra A, Salinas LS, Maldonado E, Navarro RE, 2010. Bioinformatic analysis of P granule-related proteins: insights into germ granule evolution in nematodes. Dev. Gene. Evol 220, 41–52. 10.1007/s00427-010-0327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray Nicolas L., et al. , 2016. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nature Biotech 34 (5), 525–527. 10.1038/nbt.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S, 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AC, Updike DL, 2015. CSR-1 and P granules suppress sperm-specific transcription in the C. elegans germline. Development 142, 1745–1755. 10.1242/dev.121434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, 2022. Neural is fundamental: neural stemness as the ground state of cell tumorigenicity and differentiation potential. Stem Cell Rev Rep 18 (1), 37–55. 10.1007/s12015-021-10275-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera P, Johnstone O, Nakamura A, Casanova J, Jäckle H, Lasko P, 2000. VASA mediates translation through interaction with a Drosophila yIF2 homolog. Mol. Cell 5, 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Hu Y, Lang CF, Brown JS, Schwabach S, Song X, Zhang Y, Munro E, Bennett K, Zhang D, Lee H-C, 2020. The dynamics of P granule liquid droplets are regulated by the Caenorhabditis elegans germline RNA helicase GLH-1 via its ATP hydrolysis cycle. Genetics 215, 421–434. 10.1534/genetics.120.303052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Brown JS, He T, Wu W, Tu S, Weng Z, Zhang D, Lee H-C, 2022. GLH/Vasa helicases promote germ granule formation to ensure the fidelity of piRNA-mediated transcriptome surveillance. Nat. Commun 13, 5306. 10.1038/s41467-022-32880-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciosk R, DePalma M, Priess JR, 2006. Translational regulators maintain totipotency in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Science 311 (5762), 851–853 10.1126/science.1122491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornes E, Bourdon L, Singh M, Mueller F, Quarato P, Wernersson E, Bienko M, Li B, Cecere G, 2022. piRNAs initiate transcriptional silencing of spermatogenic genes during C. elegans germline development. Dev. Cell 57, 180–196. 10.1016/j.devcel.2021.11.025 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai P, Wang X, Gou L-T, Li Z-T, Wen Z, Chen Z-G, Hua M-M, Zhong A, Wang L, Su H, Wan H, Qian K, Liao L, Li J, Tian B, Li D, Fu X-D, Shi H-J, Zhou Y, Liu M-F, 2019. A translation-activating function of MIWI/piRNA during mouse spermiogenesis. Cell 179, 1566–1581. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.022 e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S, Tang X, Ishidate T, Ozturk AR, Chen H, Yan Y-H, Dong M-Q, Shen E, Mello CC, 2022. A family of C. elegans VASA homologs control Argonaute pathway specificity and promote transgenerational silencing. Cell Rep 40 (10), 111265. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire A, Frédérick P-M, Simard MJ, 2018. Somatic and germline MicroRNAs form distinct silencing complexes to regulate their target mRNAs differently. Dev. Cell 47, 239–247. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.08.022 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani M, Lasko P, 2016. C-terminal residues specific to Vasa among DEAD-box helicases are required for its functions in piRNA biogenesis and embryonic patterning. Dev. Gene. Evol 226, 401–412. 10.1007/s00427-016-0560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RV, Chen X, Martin B, Chaturvedi S, Hwang DW, Li W, Yu C, Ding S, Thomson M, Singer RH, Coleman RA, Hansen MMK, Weinberger LS, 2021. A DNA repair pathway can regulate transcriptional noise to promote cell fate transitions. Science 373. 10.1126/science.abc6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin Alexander, et al. , 2013. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 29 (1), 15–21. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Ronald, Stanfield Gillian, 2014. The regulation of spermatogenesis and sperm function in nematodes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 29, 17–30. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavis ER, Lehmann R, 1994. Translational regulation of nanos by RNA localization. Nature 369 (6478), 315–318. 10.10388/369315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanta KS, Mello CC, 2020. Melting dsDNA donor molecules greatly improves precision genome editing in caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 216, 643–650. 10.1534/genetics.120.303564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang HD, Miller MA, 2017. Chemosensory and hyperoxia circuits in C. elegans males influence sperm navigational capacity. PLoS Biol 15, e2002047. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins HP, Keiper BD, 2020. Regulation of germ cell mRNPs by eIF4E:4EIP complexes: multiple mechanisms, one goal. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 8, 562. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins HP, Subash JS, Stoffel H, Henderson MA, Hoffman JL, Buckner DS, Sengupta MS, Boag PR, Lee M-H, Keiper BD, 2020. Distinct roles of two eIF4E isoforms in the germline of Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Sci 133, jcs237990. 10.1242/jcs.237990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone O, Lasko P, 2004. Interaction with eIF5B is essential for Vasa function during development. Development 131 (17), 4167–4178. 10.1242/dev.01286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käser-Pébernard S, Müller F, Wicky C, 2014. LET-418/Mi2 and SPR-5/LSD1 cooperatively prevent somatic reprogramming of C. elegans germline stem cells. Stem Cell Rep 2 (4), 547–549. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson AK, Egelhofer T, Rechtsteiner A, Strome S, 2017. Germ granules prevent accumulation of somatic transcripts in the adult Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Genetics 206, 163–178. 10.1534/genetics.116.198549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson AK, Rechtsteiner A, Strome S, 2016. Reevaluation of whether a soma–to–germ-line transformation extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 10.1073/pnas.1523402113, 201523402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Watanabe T, Gotoh K, Takamatsu K, Chuma S, Kojima-Kita K, Shiromoto Y, Asada N, Toyoda A, Fujiyama A, Totoki Y, Shibata T, Kimura T, Nakatsuji N, Noce T, Sasaki H, Nakano T, 2010. MVH in piRNA processing and gene silencing of retrotransposons. Genes Dev 24, 887–892. 10.1101/gad.1902110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznicki KA, Smith PA, Leung-Chiu WM, Estevez AO, Scott HC, Bennett KL, 2000. Combinatorial RNA interference indicates GLH-4 can compensate for GLH-1; these two P granule components are critical for fertility in C. elegans. Development 127, 2907–2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasko PF, Ashburner M, 1988. The product of the Drosophila gene vasa is very similar to eukaryotic initiation factor-4A. Nature 335, 611–617. 10.1038/335611a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liau W-S, Nasri U, Elmatari D, Rothman J, LaMunyon CW, 2013. Premature sperm activation and defective spermatogenesis caused by loss of spe-46 function in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One 8, e57266. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CD, Brennecke J, Dus M, Stark A, McCombie WR, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, 2009. Specialized piRNA pathways act in germline and somatic tissues of the Drosophila ovary. Cell 137, 522–535. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchal I, Tursun B, 2021. Induced neurons from germ cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Front. Neurosci 15, 771687. 10.3389/fnins.2021.771687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marnik EA, Fuqua JH, Sharp CS, Rochester JD, Xu EL, Holbrook SE, Updike DL, 2019. Germline maintenance through the multifaceted activities of GLH/vasa in Caenorhabditis elegans P granules. Genetics 213, 923–939. 10.1534/genetics.119.302670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megosh HB, Cox DN, Campbell C, Lin H, 2006. The role of PIWI and the miRNA machinery in Drosophila germline determination. Curr. Biol 16, 1884–1894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.051 https://doi.org/S0960-9822(06)02063-X [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer M, Jang S, Ni C, Buszczak M, 2021. The dynamic regulation of mRNA translation and ribosome biogenesis during germ cell development and reproductive aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 9, 710186. 10.3389/fcell.2021.710186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min H, Shim Y, Kawasaki I, 2016. Loss of PGL-1 and PGL-3, members of a family of constitutive germ-granule components, promotes germline apoptosis in C. elegans. J. Cell Sci 129, 341–353. 10.1242/jcs.174201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz M a, Noble, D., Sorokin, E.P., Kimble, J., 2014. A new dataset of spermatogenic vs. Oogenic transcriptomes in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 4, 1765–1772. 10.1534/g3.114.012351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottone C, Gigliotti S, Giangrande A, Graziani F, Verrotti di Pianella A, 2012. The translational repressor Cup is required for germ cell development in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci 125, 3114–3123. 10.1242/jcs.095208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CM, Updike DL, 2022. Germ granules and gene regulation in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Genetics 220. 10.1093/genetics/iyab195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price IF, Hertz HL, Pastore B, Wagner J, Tang W, 2021. Proximity labeling identifies LOTUS domain proteins that promote the formation of perinuclear germ granules in C. elegans. Elife 10. 10.7554/eLife.72276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramat A, Garcia-Silva M-R, Jahan C, Naït-Saïdi R, Dufourt J, Garret C, Chartier A, Cremaschi J, Patel V, Decourcelle M, Bastide A, Juge F, Simonelig M, 2020. The PIWI protein Aubergine recruits eIF3 to activate translation in the germ plasm. Cell Res 30, 421–435. 10.1038/s41422-020-0294-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez Fidel, et al. , 2016. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 44 (W1), W160–W165. 10.1093/nar/gkw257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechtsteiner A, Ercan S, Takasaki T, Phippen TM, Egelhofer TA, Wang W, Kimura H, Lieb JD, Strome S, 2010. The histone H3K36 methyltransferase MES-4 acts epigenetically to transmit the memory of germline gene expression to progeny. PLoS Genet 6, e1001091. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert VJ, Mercier MG, Bedet C, Janczarski S, Merlet J, Garvis S, Ciosk R, Palladino F, 2014. The SET-2/SET1 histone H3K4 methyltransferase maintains pluripotency in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Cell Rep 9 (2), 443–450. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TM, Pavalko FM, Ward S, 1986. Membrane and cytoplasmic proteins are transported in the same organelle complex during nematode spermatogenesis. J. Cell Biol 102, 1787–1796. 10.1083/jcb.102.5.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson James T, et al. , 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nature biotechnology 29 (1), 24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochester JD, Tanner PC, Sharp CS, Andralojc KM, Updike DL, 2017. PQN-75 is expressed in the pharyngeal gland cells of Caenorhabditiselegans and is dispensable for germline development. Biol Open 6, 1355–1363. 10.1242/bio.027987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakes Diane, et al. , 2009. Spermatogenesis-specific features of the meiotic program in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genetics 5 (8), e1000611. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singaravelu G, Singson A, 2011. New insights into the mechanism of fertilization in nematodes. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 289, 211–238. 10.1016/B978-0-12-386039-2.00006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soneson Charlotte, et al. , 2015. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research 4, 1521. 10.12688/f1000research.7563.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spichal M, Heestand B, Billmyre KK, Frenk S, Mello CC, Ahmed S, 2021. Germ granule dysfunction is a hallmark and mirror of Piwi mutant sterility. Nat. Commun 12, 1420. 10.1038/s41467-021-21635-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spike C, Meyer N, Racen E, Orsborn A, Kirchner J, Kuznicki K, Yee C, Bennett K, Strome S, 2008. Genetic analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans GLH family of P-granule proteins. Genetics 178. 10.1534/genetics.107.083469, 1973–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spracklin G, Fields B, Wan G, Becker D, Wallig A, Shukla A, Kennedy S, 2017. The RNAi inheritance machinery of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 206, 1403–1416. 10.1534/genetics.116.198812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork P, Jensen LJ, Mering C von, 2019. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D607–D613. 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, Lyon D, Kirsch R, Pyysalo S, Doncheva NT, Legeay M, Fang T, Bork P, Jensen LJ, von Mering C, 2021. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res 49, D605–D612. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima Tatsuva, et al. , 2019. Proteinase K is an activator for the male-dependent spermiogenesis pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans: Its application to pharmacological dissection of spermiogenesis. Gene Cell 24 (3), 244–258. 10.1111/gtc.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SR, Santpere G, Weinreb A, Barrett A, Reilly MB, Xu C, Varol E, Oikonomou P, Glenwinkel L, McWhirter R, Poff A, Basavaraju M, Rafi I, Yemini E, Cook SJ, Abrams A, Vidal B, Cros C, Tavazoie S, Sestan N, Hammarlund M, Hobert O, Miller DM, 2021. Molecular topography of an entire nervous system. Cell 184, 4329–4347. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.023 e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updike DL, Knutson AK, Egelhofer TA, Campbell AC, Strome S, 2014. Germ-granule components prevent somatic development in the C. elegans germline. Curr. Biol 24, 970–975. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington NL, Ward S, 2006. FER-1 regulates Ca2+ -mediated membrane fusion during C. elegans spermatogenesis. J. Cell Sci 119, 2552–2562. 10.1242/jcs.02980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenda JM, Homolka D, Yang Z, Spinelli P, Sachidanandam R, Pandey RR, Pillai RS, 2017. Distinct roles of RNA helicases MVH and TDRD9 in PIWI slicing-triggered mammalian piRNA biogenesis and function. Dev. Cell 41, 623–637. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.05.021 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiol J, Spinelli P, Laussmann M.a., Homolka D, Yang Z, Cora E, Couté Y, Conn S, Kadlec J, Sachidanandam R, Kaksonen M, Cusack S, Ephrussi A, Pillai RS, 2014. RNA clamping by Vasa assembles a piRNA amplifier complex on transposon transcripts. Cell 157, 1698–1711. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.