Abstract

Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.), is a widely cultivated crop across North Africa, with about 300 thousand tons of fruits produced per year, in Tunisia. A wide range of fungal pathogens has been associated with leaf spots of date palm, Alternaria species being the most frequently reported. Symptomatic leaves of Deglet Nour variety were randomly collected in six localities in Tunisia. We used a polyphasic approach to identify 45 Alternaria and five Curvularia strains isolated from date palm, confirming their pathogenicity. Sequencing of allergen Alt-a1, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gpd) and calmodulin genes allowed us to group 35 strains in Alternaria Section, and 10 strains in Ulocladioides section. Based on sequencing analyses of Internal Transcribed Spacer, gpd and elongation factor genomic regions, all Curvularia strains were identified as Curvularia spicifera. All Alternaria and Curvularia species tested on date palm plantlets proved to be pathogenic, fulfilling Koch’s postulates. Although no significant differences were observed among the species, the highest mean disease severity index was observed in A. arborescens, while the lowest corresponded to C. spicifera. The capability of these strains to produce mycotoxins in vitro was evaluated. None of the A. consortialis strains produced any known Alternaria mycotoxin, whereas more than 80% of the strains included in Alternaria section Alternaria produced variable amounts of multiple mycotoxins such as alternariol, alternariol monomethyl ether, altenuene, tenuazonic acid and tentoxin. Curvularia spicifera strains produced detectable traces of fumonisins B. This work reports a first comprehensive multidisciplinary study of mycotoxigenic Alternaria species and C. spicifera associated with leaf spot disease on date palm.

Keywords: Curvularia spicifera, Alternaria section, Ulocladioides section, fumonisins, Deglet Nour

Introduction

Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) is a crop widely cultivated across North Africa, from Morocco to Egypt. With about 300 thousand tons of fruits produced per year, half of which is exported (FAOSTAT, 2020), date palm occupies a strategic place in the socio-economic stability of the oasis agro-system in semiarid and arid regions in Tunisia, with about 10% of the population depending on this crop (Ben-Amor et al., 2015). Although Tunisian traditional oases play a crucial role in the maintenance of several ancient date palm cultivars, human selection, for increasing productivity and fruit size and to improve organoleptic characteristics, has led to monoculture plantation in modern oases. Indeed, nowadays, Deglet Nour is the most popular and most commonly cultivated variety in Tunisia (Hamza et al., 2015). Several abiotic and biotic factors, such as fungal pathogens, can compromise monoculture date palm cultivation (Hamza et al., 2015).

Wilt, leaf spots, apical dry leaf, black scorch, root rots and fruit rots are diseases commonly found in date palms. Fungal pathogens belonging to the genera Graphiola, Pestalotia, Microsphaerella, Nigrospora and Phoma have been isolated from date palms with symptoms of leaf spot or apical dry leaf (Abass et al., 2007; El-Deeb et al., 2007; Al-Sheikh, 2009; Abass, 2013; Khairi, 2015). In addition, Alternaria species are reported as the most important common foliar pathogens (Al-Nadabi et al., 2018, 2020) and several studies worldwide also reported the occurrence of a wide range of Curvularia species on palms showing leaf spot symptoms (Abass et al., 2007; Al-Nadabi et al., 2020; Arafat et al., 2021).

In particular, Alternaria alternata is the most important Alternaria species detected in all date palm cultivated areas. However, other Alternaria species also have been reported from symptomatic date palm leaves, such as A. burnsii and A. arborescens, in Oman (Al-Nadabi et al., 2018); A. chlamydospora and A. radicina in Iraq (Abass et al., 2007; Khudhair et al., 2015); A. bokurai, A. arborescens and A. mali in Tunisia (Ben Chobba et al., 2013; Namsi et al., 2021). Most of these reports were based only on morphological identification. The uncertain species boundaries based on morpho-taxonomy, the environmental factors influencing the morphological traits, the high similarity between some species and the presence of several strains with intermediary traits, are all aspects that could cause many errors in Alternaria identification. Therefore, a different approach is needed (Andrew et al., 2009; Somma et al., 2019).

Based primarily on morphological characters, Simmons organized the genus complexity of Alternaria by launching a species-group concept and identified more than 270 Alternaria morpho-species.

Important taxonomic revision within the genus Alternaria have been carried out through molecular studies, by using a multi-locus gene sequence approach. Alternaria morpho-species were phylogenetically analyzed and defined first as species-groups, then elevated to the status of sections (Lawrence et al., 2013, 2014; Woudenberg et al., 2015). According to this taxonomic revision, several morpho-species have been synonymized, and A. alternata has been divided into more than 35 species, including species previously belonging to closely related genera (Woudenberg et al., 2015; Somma et al., 2019).

For a correct identification of Alternaria species, a polyphasic approach, based on morphological characterization, genetic analyses and production of secondary metabolites, has been proposed. Indeed, some Alternaria species are known for the production of a wide range of secondary metabolites, including mycotoxins and host/non host specific toxins (Akimitsu et al., 2014; Meena and Samal, 2019).

The most important Alternaria mycotoxins are alternariol (AOH), alternariol monomethyl ether (AME), altenuene (ALT), and tenuazonic acid (TA; Logrieco et al., 2009; Da Cruz Cabrala et al., 2016). Based on several in vitro and in vivo assays, toxicity, mutagenicity and genotoxicity of these metabolites have been demonstrated (Lehmann et al., 2006; Ostry, 2008; Zhou and Qiang, 2008), and the risks for human and animal health have been studied (Ostry, 2008; Alexander et al., 2011).

In addition, several phytotoxins, among which some are considered host specific toxins, are known to be produced by species in the genus Alternaria (Alexander et al., 2011; Escrivá et al., 2017). Some of them can play a crucial role in pathogenicity processes, acting as virulence and colonization factors, such as AAL toxin, which plays a key role in pathogenesis of stem canker in tomato, caused by A. arborescens (Prasad and Upadhyay, 2010).

Indeed, it must be underlined that AAL toxin is chemically considered as part of the fumonisin family, a group of mycotoxins commonly produced by several Fusarium species (Desjardins, 2006). Fumonisins are classified by the International Agency of Research on Cancer, as group 2B, possible carcinogen to humans, since they have been related to esophageal cancer (International Agency for Research on Cancer - IARC, 2002). In addition, fumonisins have been associated with several animal diseases, such as porcine pulmonary edema, and equine leucoencephalomalacia (Desjardins, 2006).

The aims of this study were: (i) to identify a set of Alternaria and Curvularia strains isolated from leaves showing symptoms of leaf spot disease, by using a polyphasic approach; (ii) to assess their pathogenicity on date palm plantlets of the most common Tunisian variety Deglet Nour; (iii) to define the mycotoxin profiles of representative strains belonging to Alternaria and Ulocladioides sections; (iv) to assess the capability of C. spicifera strains to produce mycotoxins.

Materials and methods

Origin of the samples and fungal isolation

During the years 2017–2019, an in-depth survey was carried out in the modern and ancient oases of the Djérid, in south-western Tunisia: IBN Chabbat, Mides, Dgeuch, Tozeur, Nafta, El-Hamma, Hezoua. For each area, 20 samples of date palm leaflets showing characteristic symptoms of Leaf Spot Disease were randomly collected from six different plantations.

After a surface-disinfection with 2% sodium hypochlorite solution for 2 min, 70% ethanol for 30 s, and washing twice with distilled sterilized water for 1 min, portions of leaflet tissues were dried on sterile filter paper in a laminar flow cabinet. Small pieces of about 2×2 mm, taken from the margin of the symptomatic tissues, were placed on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) amended with 100 mg L−1 of streptomycin sulphate salt and 50 mg L−1 of neomycin. Petri dishes were incubated at 25 ± 1°C for 7 days under an alternating light/darkness cycle of 12 h photoperiod. After incubation, fungal colonies originated from plant tissues were transferred to new PDA plates and then purified by using the single spore isolation technique.

A set of 45 representative Alternaria strains and 5 Curvularia strains (Table 1), were selected and stored at-80°C in 10% glycerol, as suspensions of conidia and mycelium, for further molecular and chemical analyses.

Table 1.

Alternaria and Curvularia strains isolated from date palm, in Tunisia, during 2017–2019.

| Strain | Fungal species | Geographical origin | Year of isolation | Accession number | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt-a1 | CaM | gpd | ||||

| A3 | Alternaria consortialis | IBN Chabbat | 2017 | ON688353 | ON688398 | ON688443 |

| A6 | IBN Chabbat | 2017 | ON688346 | ON688391 | ON688436 | |

| A36 | IBN Chabbat | 2018 | ON688347 | ON688392 | ON688437 | |

| A38 | IBN Chabbat | 2018 | ON688345 | ON688390 | ON688435 | |

| Alt1553 | Mides | 2018 | ON688348 | ON688393 | ON688438 | |

| Alt1559 | Mides | 2019 | ON688350 | ON688395 | ON688440 | |

| Alt1565 | Mides | 2019 | ON688349 | ON688394 | ON688439 | |

| Alt1568 | Dgeuch | 2017 | ON688352 | ON688397 | ON688442 | |

| A33 | Dgeuch | 2017 | ON688354 | ON688399 | ON688444 | |

| Alt1571 | Tozeur | 2018 | ON688361 | ON688396 | ON688441 | |

| Alt1569 | Alternaria arborescens A1 | IBN Chabbat | 2017 | ON688315 | ON688360 | ON688405 |

| IBN Chabbat | 2017 | ON688310 | ON688355 | ON688390 | ||

| A16 | ||||||

| A8 | Mides | 2017 | ON688311 | ON688356 | ON688401 | |

| A37 | Mides | 2017 | ON688321 | ON688366 | ON688411 | |

| Alt1555 | Dgeuch | 2017 | ON688318 | ON688363 | ON688408 | |

| Alt1550 | Dgeuch | 2018 | ON688316 | ON688361 | ON688406 | |

| Alt1552 | ||||||

| Dgeuch | 2018 | ON688319 | ON688364 | ON688409 | ||

| Alt1558 | Tozeur | 2017 | ON688313 | ON688358 | ON688403 | |

| Alt1561 | Tozeur | 2017 | ON688320 | ON688365 | ON688410 | |

| A14 | Nafta | 2017 | ON688312 | ON688357 | ON688402 | |

| Alt1575 | El-Hamma | 2018 | ON688314 | ON688359 | ON688404 | |

| Alt1570 | Hezoua | 2018 | ON688317 | ON688362 | ON688407 | |

| Alt1551 | Alternaria tenuissima A2 | IBN Chabbat | 2017 | ON688338 | ON688383 | ON688428 |

| A4alt | IBN Chabbat | 2018 | ON688328 | ON688373 | ON688418 | |

| Alt1557 | IBN Chabbat | 2018 | ON688330 | ON688375 | ON688420 | |

| Alt1576 | IBN Chabbat | 2018 | ON688331 | ON688376 | ON688421 | |

| Alt1580 | IBN Chabbat | 2019 | ON688326 | ON688371 | ON688416 | |

| Alt1567 | Mides | 2017 | ON688333 | ON688378 | ON688423 | |

| Alt1577 | Mides | 2017 | ON688322 | ON688367 | ON688412 | |

| A23 Alt1560 | Mides | 2019 | ON688327 | ON688372 | ON688417 | |

| Alt1579 | Mides | 2019 | ON688323 | ON688368 | ON688413 | |

| Mides | 2019 | ON688324 | ON688369 | ON688414 | ||

| A26 | Tozeur | 2017 | ON688329 | ON688374 | ON688419 | |

| A30 | Tozeur | 2017 | ON688334 | ON688379 | ON688424 | |

| Alt1554 | Hezoua | 2017 | ON688332 | ON688377 | ON688422 | |

| A13 | Nafta | 2017 | ON688325 | ON688370 | ON688415 | |

| Alt1556 | Nafta | 2017 | ON688335 | ON688380 | ON688425 | |

| Alt1564 | Dgeuch | 2017 | ON688337 | ON688382 | ON688427 | |

| Alt1574 | El-Hamma | 2017 | ON688336 | ON688381 | ON688426 | |

| Alt1562 | Alternaria alternata A3 | Mides | 2017 | ON688343 | ON688388 | ON688433 |

| A12 | Mides | 2018 | ON688340 | ON688385 | ON688430 | |

| A19 | IBN Chabbat | 2018 | ON688341 | ON688386 | ON688431 | |

| IBN Chabbat | 2018 | ON688344 | ON688389 | ON688434 | ||

| Alt1563 | ||||||

| Alt1566 | Dgeuch | 2017 | ON688342 | ON688387 | ON688423 | |

| Alt1578 | Dgeuch | 2018 | ON688336 | ON688384 | ON688429 | |

| ITEM18913 | Curvularia spicifera | Nafta | 2017 | ON673959 | ON688453 | ON688448 |

| ITEM18910 | IBN Chabbat | 2018 | ON688957 | ON688451 | ON688446 | |

| ITEM18911 | IBN Chabbat | 2018 | ON688960 | ON688454 | ON688449 | |

| ITEM18912 | Tozeur | 2018 | ON688956 | ON688450 | ON688447 | |

| ITEM18909 | Tozeur | 2019 | ON688958 | ON688452 | ON688445 | |

A1, Alternaria section sub-clade A1; A2, Alternaria section sub-clade A2; A3, Alternaria section sub-clade A3.

DNA extraction and molecular analyses

Forty-five Alternaria and 5 Curvularia monoconidial strains were first cultured on PDA medium, and after 2–3 days of incubation, 5 mycelial plugs from the margins of actively growing colonies were transferred on cellophane disks overlaid on PDA plates. After 3 days of incubation at 25°C, mycelium of each strain was collected by scraping and was lyophilized. For each strain, DNA was extracted and purified from powdered lyophilized mycelium (10–15 mg) by using the “Wizard Magnetic DNA Purification System for Food” kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, United States), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Integrity of DNA was checked by electrophoretic analysis on 0.8% agarose gel and by comparison with a standard DNA (1 kb DNA Ladder, Fermentas GmbH, St. Leon-Rot, Germany); quantity was evaluated by Thermo-Scientific Nanodrop (LabX, Midland, ON, Canada).

The informative genes Allergen Alt-a1 (Alt-a1), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gpd), and calmodulin (CaM) were selected for the molecular characterization and for building a reliable phylogenetic relationship among Alternaria strains, using a multi-locus sequence approach.

For each gene, PCR mixture (15 μl) containing approximately 15–20 ng of DNA template, 1.5 μl (10X) PCR solution buffer, 0.45 μl of each primer (10 mM), 1.2 μl dNTPs (2.5 mM), and 0.125 μl of Hot Start Taq DNA Polymerase (1 U/μL; Fisher Molecular Biology, Trevose, Pennsylvania, US) was amplified. Amplification of Alt-a1 and gpd genes was performed with the primer pairs alt-for/alt-rev (Hong et al., 2005), gpd1/gpd2 (Berbee et al., 1999) using PCR reaction parameters as reported by Masiello et al. (2019), CaM gene was amplified using the PCR conditions reported by Habib et al. (2021).

Elongation factor (tef), Internal Trascribed Spacer (ITS), gpd and CaM genes were amplified for the molecular characterization of the five Curvularia strains. In particular, gpd and CaM genes were amplified using the same primers and PCR conditions used for Alternaria strains. Internal transcribed spacer was amplified with ITS4/ITS5 primers pair (White et al., 1990) setting up the termocycler at 95°C for 3 min, 40 cycles at 95°C per 30 s, 52°C for 30s and 72°C for 50 s, a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Elongation factor-1a gene was amplified using PCR conditions reported by Somma et al. (2019).

For each reaction, a no-template control was included to ascertain the absence of contamination. The PCR products, stained with GelRed® (GelRed® Nucleic Acid Gel Stain, 10000X, Biotium Inc., Fremont, California, United States) were visualized with UV after electrophoretic separation in 1X TAE buffer, on 1.5% agarose gel and sized by comparison with 100 bp DNA Ladder (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, California, United States).

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

Each PCR product was purified with the enzymatic mixture Exo/FastAP (Exonuclease I, FastAP thermosensitive alkaline phosphatase, Thermo Scientific, Lithuania, Europe) and then sequenced with Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States), according to the manufacture’s recommendations for both strands of each gene. The fragments were purified by filtration through Sephadex G-50 (5%; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, United States) and sequenced in “ABI PRISM 3730 Genetic Analyzer” (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). Partial sequences were assembled using the BioNumerics v. 5.1 software (Applied Maths, Inc., Austin, Texas, United States). Phylogenetic trees of concatenated gene sequences were generated by using maximum likelihood statistical method and bootstrap analysis (1,000 replicates, removing gaps) with MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016).

The bootstrap analysis (Felsenstein, 1985) was conducted to determine the confidence of internal nodes using a heuristic search with 1000 replicates, removing gaps. Gene sequences of the reference strains A. alternata strain EV-MIL-31, A. alternata strain ATCC 34957, A. alternata strain MOD1-FUNGI5, A. arborescens strain FERA 675, A. mali strain EGS38.029, A. tenuissima strain FERA 1166, A. atra strain MOD1-FUNGI7, A. consortialis strain JCM 1940 were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and included in the phylogenetic analysis.

Sequences of Curvularia strains were analysed together with reference sequences of C. spicifera CBS 274.52, C. hawaiiensis BRIP 10971, C. australiensis CBS 172.57, C. lunata CBS 730-96, C. perotidis CBS 350.90 as reported by Manamgoda et al. (2012).

Mycotoxin analyses

Thirty-two Alternaria strains and the five Curvularia strains were analysed for their capability to produce mycotoxins in vitro. Was inoculated, Three small plugs from 1-week-old colonies of each fungal strain were used to inoculate 30 g autoclaved rice with 40% moisture in 250 ml of flasks. Flasks were incubated for 21 days at 25°C in darkness and then the samples were finely ground with an Oster Classic grinder (220–240 V, 50/60 Hz, 600 W; Madrid, Spain).

For mycotoxin analyses, samples were prepared according to Malachová et al. (2014) procedure. Briefly, 0.5 g of ground cereal was stirred for 90 min at 200 strokes/min on a shaker with 2 ml of acetonitrile/water (80/20, v/v) mixture acidified with 0.2% of formic acid and then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 rpm. 1 μl of supernatant was injected into LC–MS.

Mycotoxin standards of AOH, AME, ALT, ATX-I, TA, TEN, and fumonisins were obtained from Romer Labs (Tulln, Austria).

LC–MS grade methanol, and acetonitrile were purchased from Scharlab Italia srl (Milan, Italy); bidistilled water was obtained using Milli-Q System (Millipore, Bedford, MA, United States). MS-grade ammonium acetate, acetic acid and formic acid were purchased from Fisher Chemical (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., San Jose, CA, United States).

UHPLC-TWIMS-QTOF screening of mycotoxins

ACQUITY I-Class UPLC separation system coupled to a VION IMS QTOF mass spectrometer (Waters, Wilmslow, United Kingdom) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) interface was employed for mycotoxin screening. Samples were injected (1 μl) and chromatographically separated using a reversed-phase C18 BEH ACQUITY column 2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size (Waters, Milford, MA, United States). A gradient profile was applied using water 1 mM ammonium acetate (eluent A) and methanol (eluent B) both acidified with 0.5% acetic acid as mobile phases. Initial conditions were set at 5% B, after 0.7 min of isocratic step, a linear change to 50% B in 5.8 min. 100% B was achieved in 3 min and holding for 3 min to allow for column washing before returning to initial conditions. Column recondition was achieved over 1.5 min, providing a total run time of 14 min. The column was maintained at 40°C and a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min used.

Mass spectrometry data were collected in positive electrospray mode over the mass range of m/z 50–1,000. Source settings were maintained using a capillary voltage, 1.0 kV; source temperature, 150°C; desolvation temperature, 600°C and desolvation gas flow, 1,000 l/h. The TOF analyzer was operated in sensitivity mode and data acquired using HDMSE, which is a data independent approach (DIA) coupled with ion mobility. The optimized ion mobility settings included: nitrogen flow rate, 90 ml/min (3.2 mbar); wave velocity 650 m/s and wave height, 40 V. Device within the Vion was calibrated using the Major Mix IMS calibration kit (Waters, Wilmslow, United Kingdom) to allow for CCS values to be determined in nitrogen. The calibration covered the CCS range from 130 to 306 Å2. The TOF was also calibrated prior to data acquisition and covered the mass range from 151 Da to 1,013 Da. TOF and CCS calibrations were performed for both positive and negative ion mode. Data acquisition was conducted using UNIFI 1.8 (Waters, Wilmslow, United Kingdom).

Mycotoxin identification was performed by comparison of retention time, fragmentation pattern and collision cross sections with the standard collect in our UNIFI library, created by running a mix of standards with the same analytical method. Quantification of target analytes was performed using calibration standards in the range 0.1–2 mg kg−1.

Pathogenicity assay

Pathogenicity assays were carried out by using 39 fungal strains, selected among all Alternaria phylogenetic clades, and 3 out of the 5 Curvularia strains (Table 1). The strains were grown for 7–10 days at 25°C on PDA, under a 12 h light/darkness photoperiod, to favor fungal sporulation. For each strain, the inoculum was prepared by flooding the agar plate surface with 10 ml of sterile distilled water (SDW) and scraping with a spatula. Conidial suspensions were filtered through four layers of cheese cloth and adjusted at a final concentration of 106 conidia mL−1.

The pathogenicity tests were performed on healthy date palm plantlets (cv. Deglet Nour), regenerated from direct somatic embryogenesis, derived from shoot-tip explants. Before pathogenicity test, the plantlets were acclimatized in greenhouse under suitable controlled conditions, for 6-months.

The plantlets were of 25–30 cm length, having 4–5 leaves, and grown in large pots (12 cm diameter and 18 cm height filled with planting medium peat/perlite 2:1 (v/v)). Crown area of each plantlet was sprayed with 4 ml of conidial suspension by using hand operated compressed air sprayer. Pathogenicity of each fungal strain was assessed in triplicates and plantlets sprayed only with SDW were used as control. To favor fungal development, all plantlets were watered and enclosed in plastic bags for 3 days in a greenhouse set at 25 ± 2°C, 80% RH, 12 h light/darkness photoperiod. After inoculation, the first visual assessment was carried out after 10 days and then weekly for 3 months.

The severity of disease symptoms was calculated according to Bhat et al. (2013), with 6 disease severity classes from 0 (healthy plantlets) to 5 (disease symptoms on the 75–100% of the plantlet area). Intermediate disease symptoms were assigned to 4 classes (1 = 0–1 spot and yellowing of about 0.1–10% of the plantlet area; 2 = 1–3 spots, with yellowing of 11.1–25% of the plantlet area; 3 = 4–6 spots, with yellowing of 26–50% of the plantlet area; 4 = 7–9 spots, with yellowing up to 75% of the plantlet area). The Disease Severity Index was calculated for each plantlet by McKinney’s formula

Where n is number of palm plantlets per class, v is the numerical value of each class, N is the total number of plantlets and V is the highest class value.

Differences in the disease severity incidence between isolates were tested for statistical significance with Kruskal–Wallis tests using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v. 27.0 software, with significance level (P) of 0.05. To confirm Koch’s postulates, pieces of leaves, where symptoms of the disease appeared, were sterilized on the surface and the fungi were re-isolated.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses

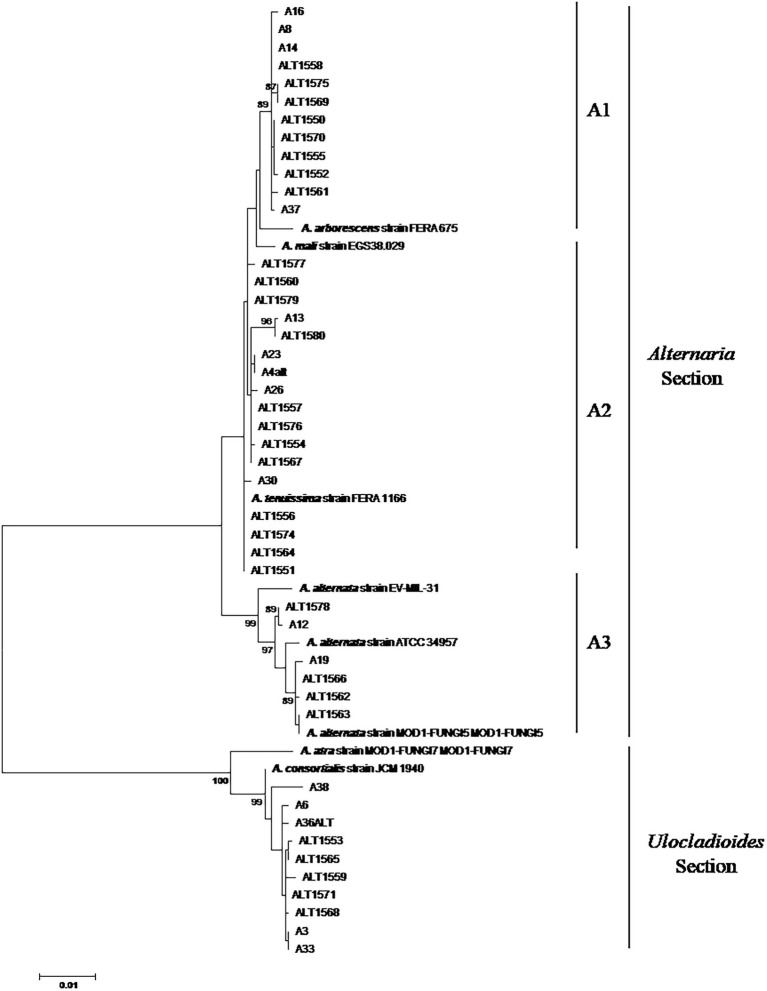

Phylogenetic relationships among 45 Alternaria strains were studied at the genetic level by amplifying fragments of three different genes: CaM, Alt-a1, and gpd. To further resolve the identity of the Alternaria strains, the sequences of each gene were aligned and cut at the ends to analyse a common fragment for all the strains. In particular, 675, 485, and 590 nucleotide sites were used for CaM, Alt-a1, and gpd genes, respectively. For each strain, the three gene sequences were concatenated and analysed simultaneously with species reference strains (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree generated by using the Maximum Likelihood method of combined CaM, alt-a1, and gpd gene sequences of 45 Alternaria strains isolated from date palm, in Tunisia. Numbers on branches are bootstrap values (>70) based on 1,000 replicates.

The phylogenetic analysis of the concatenated sequences of 1750 positions resulted in a phylogenetic combining dataset comprising 53 taxa, including 45 Alternaria field strains and 8 Alternaria reference sequences. The phylogenetic tree was resolved in two well-separated clades corresponding to Alternaria and Ulocladioides sections, supported by high bootstrap values (Figure 1).

Thirty-five strains (77.7%) were assigned to the Alternaria Section Alternaria. In particular, 12 strains shared a very high similarity among them and clustered with A. arborescens FERA 675 reference strain (Figure 1; sub-clade A1). A well-supported group clustered together the three A. alternata reference strains (EV-MIL-31, ATCC 34957 and MOD1-FUNGI5) and six field strains (Figure 1; sub-clade A3). The other 17 strains clustered together with A. tenuissima FERA1166 in a not well-supported group (sub-clade A3).

A well-supported clade (clade B), defined as Ulocladioides section, grouped together A. consortialis JCM 1940 reference strain, A. atra MOD1-FUNGI7 and 10 field strains (Figure 1). In particular, with the exception of A38 strain, they showed high homology among them (Figure 1).

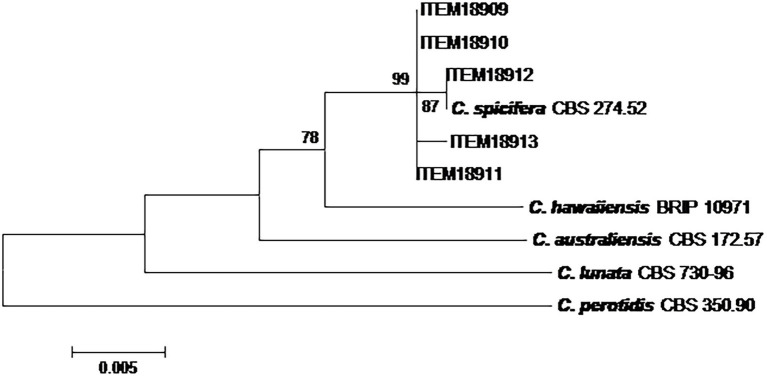

The phylogenetic analysis on five Curvularia strains was carried out considering a concatenated sequence of 1,318 sites, including the 5 field strains, 4 Curvularia reference strains and A. alternata EGS 34.016 considered as the outgroup taxon (Figure 2). The phylogenetic tree showed that all field strains clustered together, showing high homology with C. spicifera CBS 274.52. They formed a well-separated group (bootstrap 99) from the other Curvularia species included in the analyses, genetically closely related to C. spicifera (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree generated by maximum likelihood analysis (bootstrap 1,000 replicates) of combined ITS, gpd and EF-1α loci of 5 Curvularia strains isolated from date palm, in Tunisia. Numbers on branches are bootstrap values (>70) based on 1,000 replicates.

Sequences derived in this study were deposited in the GenBank database (Table 1).

Mycotoxin production

Thirty-two Alternaria strains were selected among the phylogenetic sub-clades (Figure 1) to evaluate their capacity to produce the mycotoxins considered so far the most common ones produced by the species of Alternaria. The mycotoxin production of each strain and the mean values of each Alternaria phylogenetic sub-clade are reported in Table 2. The five C. spicifera strains were also analysed to investigate their capability to produce the selected mycotoxins. In detail, chemical analyses were carried out on eight Alternaria strains which clustered with A. arborescens reference strain, 11 strains that clustered with A. tenuissima reference strain, three strains genetically identified as A. alternata, 10 A. consortialis strains and five C. spicifera strains. None of the A. consortialis and Curvularia strains synthesized any of the Alternaria mycotoxins selected in the study. Among the strains included in the three sub-clades of Alternaria section, the majority of the strains were able to produce the selected mycotoxins. In particular, 41% of the strains were able to co-produce simultaneously all five mycotoxins investigated, whereas 32% of strains produced 4 mycotoxins (Table 2). In A. arborescens group (sub-clade A1), all strains produced AOH with values ranging between 68.6 and 974.2 μg g−1 (mean value 428 μg g−1), AME with values ranging between 31 and 372.5 μg g−1 (mean value 221.7 μg g−1), and TA with values ranging between 5.7 μg g−1 and 22.2 μg g−1 (mean value 13.5 μg g−1). Only 4 out of 8 strains (A8, A14, ALT1575, and A37) produced ALT with values ranging between 35.7 and 115.2 μg g−1 (mean value 71 μg g−1). TEN was produced by all strains, with the exception of the strains ALT1558 and ALT1570, with values that never exceeded 15.1 μg g−1 (mean value of 6.2 μg g−1).

Table 2.

Mycotoxin production by Alternaria and Curvularia strains isolated from date palm in Tunisia.

| Strain | Mycotoxin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT | AOH | AME | TEN | TA | |

| Alternaria Section sub-clade A1 (A. arborescens) | |||||

| A16 | n.d. | 421.1 | 174.0 | 1.2 | 11.6 |

| A8 | 35.7 | 519.5 | 321.3 | 1.5 | 20.5 |

| A14 | 115.2 | 974.2 | 372.5 | 9.6 | 22.1 |

| ALT1575 | 85.7 | 814.9 | 332.4 | 15.1 | 14.0 |

| ALT1558 | n.d. | 68.6 | 31.0 | n.d. | 5.7 |

| ALT1550 | n.d. | 203.5 | 132.1 | 6.8 | 11.3 |

| ALT1570 | n.d. | 163.6 | 103.5 | n.d. | 5.7 |

| A37 | 47.2 | 258.5 | 306.8 | 3.2 | 16.8 |

| N. of positive/total strains | 4/8 | 8/8 | 8/8 | 6/8 | 8/8 |

| Frequency (%) | 50 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 100 |

| MIN | 35.7 | 68.6 | 31 | 1.2 | 5.7 |

| MAX | 115.2 | 974.2 | 372.5 | 15.1 | 22.2 |

| Mean value | 71 | 428 | 221.7 | 6.2 | 13.5 |

| Alternaria Section sub-clade A2 (A. tenuissima) | |||||

| A4ALT | 14.9 | 16.2 | 30.7 | 13.1 | 3.5 |

| A23 | 31.4 | 35.9 | 65.1 | 14.6 | 4.7 |

| A26 | 19.2 | 27.8 | 61.6 | 10.7 | 5.5 |

| A30 | n.d. | 18.8 | 12.3 | 1.0 | n.d. |

| ALT1554 | n.d. | 60.4 | 27.2 | 0.3 | 1.4 |

| ALT1557 | n.d. | 6.3 | 3.0 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| ALT1576 | 23.3 | 58.5 | 99.8 | 3.9 | 9.8 |

| ALT1579 | n.d. | 45.8 | 4.7 | 6.2 | n.d. |

| A13 | n.d. | 38.8 | 18.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| ALT1574 | n.d. | 56.3 | 21.5 | 0.5 | n.d. |

| ALT1551 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.4 | n.d. |

| N. of positive/total strains | 4/11 | 10/11 | 10/11 | 11/11 | 7/11 |

| Frequency (%) | 36.4 | 91 | 91 | 100 | 63.6 |

| MIN | 14.9 | 6.3 | 3 | 0.3 | n.d. |

| MAX | 31.4 | 60.4 | 99.8 | 14.6 | 9.8 |

| Mean value | 22.2 | 36.5 | 34.4 | 4.7 | 2.4 |

| Alternaria Section sub-clade A3 (A. alternata) | |||||

| A12 | n.d. | 352.7 | 183 | 3.2 | 56.5 |

| A19 | 45 | 35.6 | 91.4 | 0.6 | 6.0 |

| ALT1563 | n.d. | 12 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| N. of positive/total strains | 1/3 | 3/3 | 2/3 | 2/3 | 2/3 |

| Frequency (%) | 33.3 | 100 | 66.6 | 66.6 | 66.6 |

| MIN | - | 12 | 91.4 | 0.6 | n.d. |

| MAX | - | 352.7 | 183 | 3.2 | 56.5 |

| Mean value | - | 133.4 | 137.2 | 1.9 | 20.8 |

| Ulocladioides section (A. consortialis) | |||||

| N. of positive/total strains | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 |

| Curvularia spicifera | |||||

| N. of positive/total strains | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

Data are expressed as μg/g of dried rice kernels. ALT, altenuene; AOH, alternariol; AME, alternariol monomethyl ether; TEN, tentoxin; TA, tenuazonic acid. N. of positive strains, frequency, minimum, maximum and mean values for each phylogenetic group are reported in bold.

The strains included in the A. tenuissima sub-clade showed a slightly lower capability to produce mycotoxins (Table 2). With the exception of Alt11551, which produced only trace amounts of TEN, all strains produced AOH with values ranging between 6.3 and 60.4 μg g−1 (mean value 36.5 μg g−1) and AME with values ranging between 3 and 99.8 μg g−1 (mean value 34.4 μg g−1). All strains produced TEN (mean values 4.7 μg g−1), although 8 out of 11 strains produced less than 1 μg g−1. Altenuene was produced by 4 out of 11 strains with values ranging between 14.9 and 31.4 μg g−1 (mean value of 22.2 μg g−1). With the exception of the strains A26, Alt1579, Alt1574 and Alt1551, TA was produced with values ranging between less than LOQ and 9.4 μg g−1 (mean values of 2.4 μg g−1).

Among A. alternata strains, Alt1563 produced only AOH (12 μg g−1), whereas the other two strains produced AOH, AME, TEN, and TA (Table 2). Only A19 strain produced ALT (45 μg g−1).

The mycotoxin analysis was performed using a HR-IMS instrument, taking advantage of the ion mobility CCS values library developed in house and validated over an inter laboratory and inter platform study (Righetti et al., 2018, 2020). The CCS value represents a univocal chemical feature of an analyte, offering an additional and independent point of identification with respect to the MS spectra and the retention time. The database collects the consistent CCS values for 53 mycotoxins, and it is therefore extremely useful for the retrospective qualitative analysis of samples.

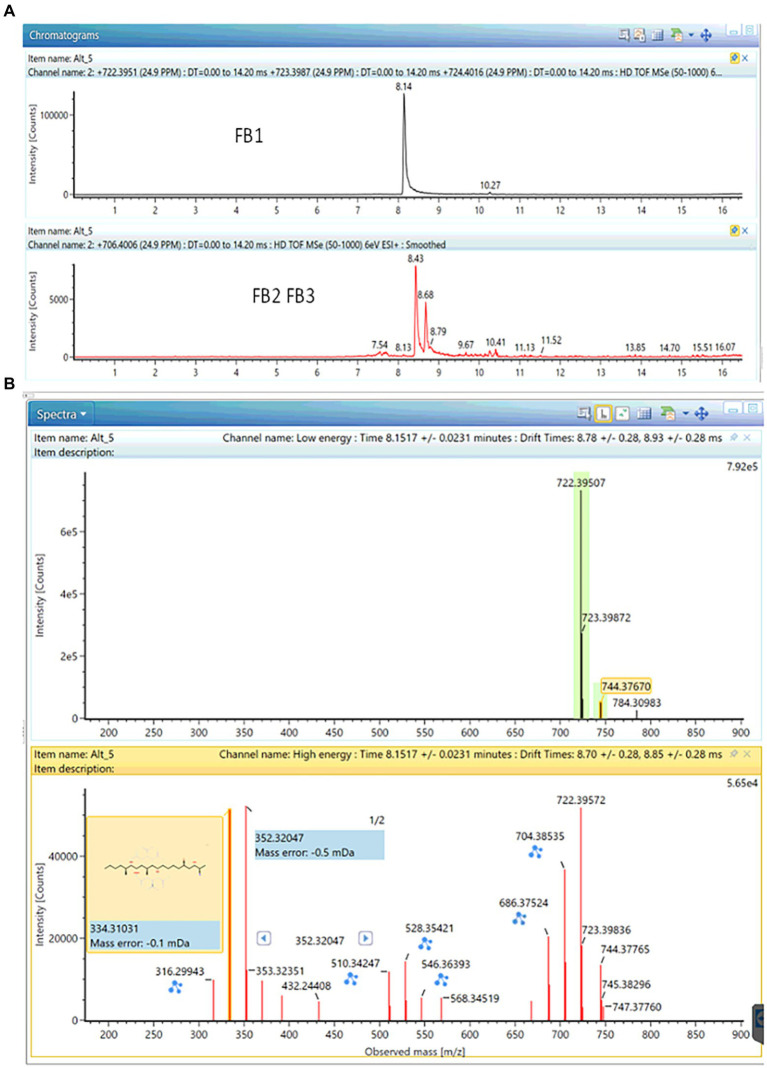

Based on the aforementioned approach, the production of small amounts of fumonisin B1 by four out of five Curvularia strains (ITEM18909, ITEM18910, ITEM18912, ITEM18913) was detected (see Figure 3). The annotation was further confirmed through comparison with the analytical standard, returning a mass error of-0.9 ppm; a shift in retention time of 0.12% as well as a ΔCCS% of-0.30. All these parameters fall well within the quality criteria for annotation.

Figure 3.

Production of FB1 together with small traces of FB2 and FB3 in ITEM18910 strain. (A) Chromatogram; (B) MS and fragmentation spectra (mass error: −0.9 ppm; ΔrT: 0.01 min; ΔCCS: −0.30).

Small amounts of FB2 and FB3 have been found in cultures of ITEM18910 as well (see Figure 3; mass error: −1.3 ppm for both FB2 and FB3; ΔrT%: 2.7 and 0.1% for FB2 and FB3 respectively; ΔCCS%: −1.48% and-0.84% for FB2 and FB3 respectively).

A preliminary comparison of the production capability was performed based on the amount detected in the five strains after the same extraction, ITEM18910 being the highest producer. The absence of FB1 in ITEM18911 could be due to a lower production, falling below the instrumental sensitivity. Further studies should be carried out to further confirm and better understand the capability to synthesize FB1 in C spicifera strains.

Pathogenicity test

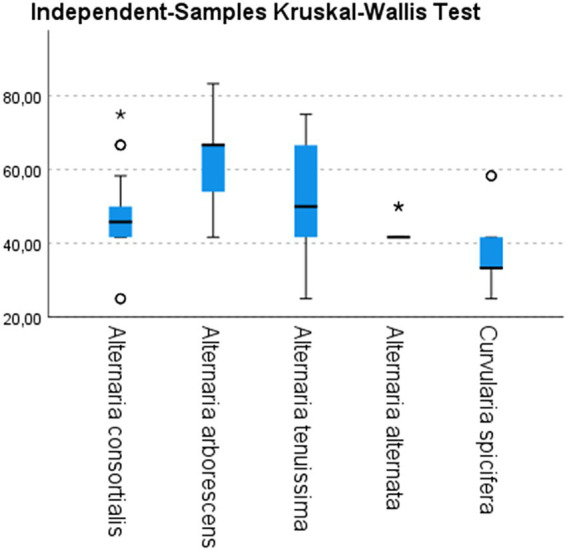

All inoculated plantlets showed the typical symptoms of leaf spot disease whereas the control plantlets did not show any symptoms up to 3 months after inoculation. However, symptomatic plantlets showed different degrees of disease severity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Disease severity index (vertical axes) calculated on inoculated date palm plantlets with strains belonging to different species of Alternaria (10 A. consortialis strains, 9 A. arborescens strains, 17 A. tenuissima strains, 3 A. alternata strains) and to Curvularia spicifera (3 strains). Differences among species have been statistically evaluated through independent-samples Kruskal–Wallis test: χ2 (df = 4, N = 126) = 28.575; p < 0.05. Box plots are displayed, where the bold line indicates the median per group, the box represents 50% of the values, and horizontal lines show minimum and maximum values of the calculated nonoutlier values; asterixes and open circles indicate outlier values.

The typical leaf spot symptoms developed 10 days after inoculation. In particular, necrotic spots appeared on the inoculated plants 5–7 days after inoculation, and spread along the entire leaves and stems within 15 days. Among the fungal species tested, A. arborescens showed a higher DSI than other species, ranging from 52.7 to 72.2 (mean value 62) followed by A. tenuissima (mean value 52) and A. consortialis (mean value 47.8), as showed in Figure 4. The A. alternata and C. spicifera stains showed a lower degree of severity with DSI ranging between 41.6 and 48, or 33.3 and 47.2, respectively (Figure 4).

Discussion

Species identification

In this study, we report for the first time an extensive study on the Alternaria species occurring on date palm leaves showing leaf spot symptoms, in Tunisia. In recent years, a high incidence of leaf spot disease was recorded on date palm (Namsi et al., 2021). In the period 2017–2019, we inspected palm date plantations located in Djerib, the most intense area of date production in Tunisia. Leaf spot disease was detected in all localities investigated, with incidence values up to 22% in Mides area (data not shown). Although traditional varieties such as Beser Hlou, Kentikhi, and Alig are cultivated in this region, Deglet Nour is the most popular and widely cultivated variety in Tunisia. However, this variety is highly susceptibile to fungal pathogens including Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis and a range of fungal species associated with foliar disease (Matheron and Benbadis, 1990; Hamza et al., 2015). The most important pathogens associated to leaf spot disease are Alternaria species. Based on multi-locus sequence analyses, all Alternaria strains considered in this study were assigned to two main Sections: Ulocladioides that included only A. consortialis species, and Alternaria section, that included 3 well-separated sub-clades corresponding to the formerly described A. alternata, A. arborescens and A. tenuissima morpho-species. Several studies report Alternaria species among the most important phytopathogenic fungi associated with date palm leaf spot disease. However, in almost all studies Alternaria strains were identified only based on morphological traits. In Oman, sequence analyses of ITS region showed that A. arborescens and A. alternata were the most common Alternaria species associated with leaf spots of date palms (Al-Sadi et al., 2012). However, ITS region alone is not very informative to identify Alternaria species (Woudenberg et al., 2013). Indeed, in the same country, two subsequent extensive studies, based on the sequence analyses of the ITS, gpd, tef and RNA polymerase II subunit informative genes, confirmed A. alternata and A. arborescens as the most frequent species isolated from symptomatic date palm leaves, but also revealed the presence of two other species included in the Alternaria section: A. burnsii and A. tomato species (Al-Nadabi et al., 2018, 2020). In addition to the above mentioned species, other species have been associated with leaf blight in Tunisia. Ben Chobba et al. (2013) identified also A. gaisen (included in Alternaria Section) by using ITS1 and ITS4 genes, whereas Namsi et al. (2021) identified A. mali, by using ITS, gpd, CaM, and Alt-a1 genes. However, in other studies, A. mali was proposed as synonymous to A. alternata species (Woudenberg et al., 2015), whereas, according to Somma et al. (2019), A. mali was phylogenetically more similar to A. gaisen, both species being distinguishable from A. alternata. These incongruences could be likely due to the different genomic regions considered for phylogenetic analysis, which suggests that it would be beneficial to establish a common pool of genes and procedures to be unanimously adopted by the scientific community dealing with Alternaria genus taxonomy, to better define the phylogenetic relationships among species. On the other hand, the previously described morpho-species A. alternata and A. tenuissima were compared according to their whole genomes and transcriptomes (Woudenberg et al., 2015), and for multi-gene sequences (Somma et al., 2019). From such comparisons, the two species were both included in Alternaria section by Woudenberg et al. (2015) and Somma et al. (2019) who merged them in the same species, namely A. alternata. Furthermore, in both papers, A. arborescens formed a distinct clade from A. alternata, confirming the data here reported. In our study, we report for the first time the occurrence of A. consortialis (Section Ulocladoidies) as a cause of disease symptoms on date palm leaves. Also, we report here for the first time, the pathogenicity of C. spicifera on date palm leaves in Tunisia. This species has been never reported on date palm, although many other species of the genus Curvularia have been reported to occur on date palm symptomatic leaves, such as C. subpapendrofii in Iraq and Oman (Abass et al., 2007; Al-Nadabi et al., 2020), C. verruculosa and C. hawaiiensis in Oman (Al-Nadabi et al., 2020), and C. palmivora in Egypt (Arafat et al., 2021).

Pathogenicity test

The 3 strains of C. spicifera tested for pathogenicity showed to be all moderately aggressive in our bioassay, carried out on the Deglet Nour variety. They were the least aggressive in our tests compared the species of Alternaria tested. These data are in contrast with Arafat et al. (2021) that showed C. spicifera and C. palmivora were highly aggressive on date palm in Egypt. In addition, another species of the genus Curvularia, C. verruculosa, proved to be highly aggressive on date palm leaves (Al-Nadabi et al., 2020). Among the Alternaria strains tested, those belonging to A. consortialis showed to be pathogenic at a moderate level compared the other Alternaria species tested, where the most pathogenic strains were those belonging to A. arborescens, followed by A. tenuissima, while the less pathogenic were the strains belonging to A. alternata. These data agree with Al-Nadabi et al. (2020) who reported that A. alternata, isolated in Oman from date palm, was weakly pathogenic on date palm leaves assay. On the other hand, they reported that strains of A. burnsii and A. tomato were highly pathogenic, but we did not detect these species in our study (Al-Nadabi et al., 2020).

Mycotoxin profile

In addition to their pathogenicity, which can lead to a reduced productivity, all Alternaria species identified in this survey are also of concern since they can produce a wide range of mycotoxins (Logrieco et al., 2009). Their occurrence on date palm plants indicates that a contamination of fruit at the harvest in the field and its by-products in postharvest can occur. Since we showed a high occurrence of toxigenic Alternaria species in plants, monitoring environmental conditions in the field suitable for mycotoxin production in planta by the Alternaria species is important in order to manage and avoid an eventual, although unlikely, contamination of fruits. Many date-based products such as pickles, chutney, jam, jelly, date-in-syrup, date butter, candy, date bars and confectionary products are consumed in different parts of the world, including Tunisia. Some evidence of contamination by Alternaria in date palm fruits are available (Palou et al., 2016; Piombo et al., 2020). Therefore, as a consequence, this contamination could cause risk for consumers, but could also interfere with date fruits industrial processing. Our chemical and phylogenetic results showed that most of the identified Alternaria strains belong to toxigenic species and could produce all mycotoxin tested, ALT, AOH, AME, TEN, and TA, with the exception of A. consortialis strains, which did not produce any mycotoxin tested. Studies have shown that TA was responsible for some changes in the esophageal mucosa of mice (Yekeler et al., 2001) and was reported as cytotoxic, phytotoxic, antitumoral, antiviral, antibiotic and antibacterial compound (Asam et al., 2013). Solhaug et al. (2015) reported AOH and AME as the most detected mycotoxins in food and feed products, both identified as genotoxic and mutagenic with immune modulating effects. Recently, Huybrechts et al. (2018) associated Alternaria mycotoxins also with colon rectal cancer in humans. Due to this wide range of toxic effects of Alternaria mycotoxins, the need for correct identification of Alternaria species is a key aspect, since many species have a specific mycotoxin profile. Therefore, accurate risk assessment is strongly linked to the use of reliable and advanced diagnostic tools. The extended production of the Alternaria mycotoxins by several Alternaria strains tested in this work, that were able to produce all mycotoxins analyzed, shows that a co-occurrence of Alternaria mycotoxins on date palm plants would be likely, indicating an increased risk for the contamination of final products. In addition, some of the Alternaria mycotoxins can play a crucial role in pathogenicity processes, acting as virulence and colonization factors. For instance, Wenderoth et al. (2019) demonstrated that the AOH biosynthesis pathway was responsible for the production of at least five different secondary metabolites and that AOH facilitates growth of A. alternata on various fruits and leaves during infection. In addition, TA is the essential requirement for successful colonization and disease development in host leaves of Ageratina adenophora (Shi et al., 2021). The fact that many strains analyzed in this work can produce both AOH and TA triggers further investigations on the role that these secondary metabolites can play in Alternaria aggressiveness against date palm plants. Finally, the strains of C. spicifera proved to be able to produce FBs. How widely distributed this pathogen is on date palm and how extended is the ability of C. spicifera to produce FBs need to be further investigated by testing more strains. Specific investigations are in progress, in order to evaluate the genetic structure of the biosynthetic gene pathway responsible of FBs production in this species. Curvularia spicifera species have been detected also on strawberry in Iran (Ayoubi et al., 2017), on citrus fruits in south Italy (Garganese et al., 2015), on date palm fruit in Saudi Arabia (Al-Sheikh, 2009). Although in these studies, the authors did not evaluate the capability of these strains to produce mycotoxins, our results should trigger further studies aimed to evaluate the toxigenic risk occurring on the final products of these important crops. Controversial reports exist on the ability of the FBs to be phytotoxic toward plants. In particular, the AAL toxin, structurally identical to FBs, was proved to be a specific toxin required to cause pathogenicity in tomato colonized by A. alternata forma specialis lycopersici (sinonym. A. arborescens). On the other hand, Arias et al. (2012) proved that FBs play a role in virulence but also that FB production is not necessary or sufficient for virulence on maize seedlings. Therefore, further experiments are required to test FB phytotoxicity on date palm plants and better understand their role in the pathogenesis process, related to C. spicifera.

In conclusion, our studies have provided new insights on the identification of new pathogenic Alternaria and Curvularia species affecting date palm, in Tunisia. The phylogeny of the Alternaria species here performed has confirmed that A. arborescens formed a distinct clade from A. alternata, and that the previously described morpho-species A. alternata and A. tenuissima should be merged in the same species, namely A. alternata. A high mycotoxin concern in date palm is due to wide ability of many of the Alternaria strains tested to produce all mycotoxins analyzed, and in-depth investigation on the role of Alternaria toxins in colonization of date palm is required. Finally, the ability of the Curvularia strains to produce the highly harmful FBs triggers further studies to better investigate their possible role in date palm colonization and eventual risk for consumers.

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the GenBank repository, accession numbers ON688310 - ON688454.

Author contributions

AR: investigation, formal analysis, data curation, writing-original draft. MM: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing. SS: methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing-original draft. FC: investigation, formal analysis. CD: conceptualization and methodology. LR: methodology, validation and writing-original draft. AS: methodology and data curation. AL: funding acquisition. AN: investigation, methodology. RG: investigation. SW: supervisor. AM: project administration, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Marinella Cavallo and Mrs Simonetta Martena from ISPA-CNR for the excellent technical and administrative assistance.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1034658/full#supplementary-material

Extracted ions chromatogram (XIC) showing the absence of FB1 in blank rice medium.

References

- Abass M. (2013). Microbial contaminants of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera l.) in Iraqi tissue culture laboratories. Emir. J. Food Agric. 25, 875–882. doi: 10.9755/ejfa.v25i11.15351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abass M. H., Hameed M. A., Alsadoon A. H. (2007). Survey of fungal leaf spot diseases of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera l.) in Shaat-Alarab orchards/Basrah and evaluation of some fungicides. Basrah J. Date Palm Res. 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Akimitsu K., Tsuge T., Kodama M., Yamamoto M., Otani H. (2014). Alternaria host-selective toxins: determinant factors of plant disease. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 80, 109–122. doi: 10.1007/s10327-013-0498-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J., Benford D., Boobis A., Ceccatelli S., Cottrill B., Cravedi J., et al. (2011). Scientific opinion on the risks for animal and public health related to the presence of Alternaria toxins in feed and food. EFSA J. 9, 2407–2504. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nadabi H., Maharachchikumbura S. S. N., Agrama H., Al-Azri M., Nasehi A., Al-Sad A. M. (2018). Molecular characterization and pathogenicity of Alternaria species on wheat and date palms in Oman. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 152, 577–588. doi: 10.1007/s10658-018-1550-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nadabi H., Maharachchikumbura S. S. N., AlGahaffi Z. S., Al-Hasani A. S., Velazhahan R., Al-Sadi A. M. (2020). Molecular identification of fungal pathogens associated with leaf spot disease of date palms (Phoenix dactylifera). All Life 13, 587–597. doi: 10.1080/26895293.2020.1835740 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sadi A. M., Al-Jabri A. H., Al-Mazroui S. S., Al-Mahmooli I. H. (2012). Characterization and pathogenicity of fungi and oomycetes associated with root diseases of date palms in Oman. Crop Prot. 37, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2012.02.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sheikh H. (2009). Date-palm fruit spoilage and seed-borne fungi of Saudi Arabia. Res. J. Microbiol. 4, 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew M., Peever T. L., Pryor B. M. (2009). An expanded multilocus phylogeny does not resolve morphological species within the small-spored Alternaria species complex. Mycologia 10, 1–95. doi: 10.3852/08-135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arafat K. H., Hassan M., Hussein E. A. (2021). Detection, disease severity and chlorophyll prediction of date palm leaf spot fungal diseases. NVJAS 1, 98–110. doi: 10.21608/nvjas.2022.110022.1027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arias S. L., Theumer M. G., Mary V. S., Rubinstein H. R. (2012). Fumonisins: probable role as effectors in the complex interaction of susceptible and resistant maize hybrids and Fusarium verticillioides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 5667–5675. doi: 10.1021/jf3016333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asam S., Habler K., Rychlik M. (2013). Determination of tenuazonic acid in human urine by means of a stable isotope dilution assay. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 4149–4158. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-6793-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoubi N., Soleimani M. J., Zare R., Zafari D. (2017). First report of Curvularia inaequalis and C. spicifera causing leaf blight and fruit rot of strawberry in Iran. Nova Hedwigia 105, 75–85. doi: 10.1127/nova_hedwigia/2017/0402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Chobba I., Elleuch A., Ayadi I., Khannous L., Namsi A., Cerqueira F., et al. (2013). Fungal diversity in adult date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 14, 1084–1099. doi: 10.1631/jzus.b1200300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Amor R., Aguayo E., de Miguel-Gomez M. D. (2015). The competitive advantage of the Tunisian palm date sector in the Mediterranean region. Span. J. Agric. Res. 13:2. doi: 10.5424/sjar/2015132-6390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berbee M. L., Pirseyedi M., Hubbard S. (1999). Cochliobolus phylogenetics and the origin of known, highly virulent pathogens, inferred from ITS and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene sequences. Mycologia 91, 964–977. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-01-21-0025-PDN [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat H. A., Ahmad K., Ahanger R. A., Qazi N. A., Dar N. A., Ganie S. A. (2013). Status and symptomatology of Alternaria leaf blight (Alternaria alternata) of gerbera (gerbera jamisonii) in Kashmir valley. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 8, 819–823. doi: 10.5897/AJAR12.1766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Da Cruz Cabrala L., Terminiello L., Pinto V. F., Fog K., Patriarca N. A. (2016). Natural occurrence of mycotoxins and toxigenic capacity of Alternaria strains from mouldy peppers. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 7, 155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins A. E. (2006). Fusarium Mycotoxins: Chemistry, Genetics, and Biology. Vol. 531. St. Paul, MN: APS Press [Google Scholar]

- El-Deeb H. M., Lashin S. M., Arab Y. A. (2007). Distribution and pathogenesis of date palm fungi in Egypt. Acta. Hort. 736, 421–429. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2007.736.39 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Escrivá L., Oueslati S., Font G., Manyes L. (2017). Alternaria mycotoxins in food and feed: an overview. J. Food Qual. 2017:1569748. doi: 10.1155/2017/1569748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT - (2020). Available at: https://www.fao.org/faostat (Accessed May 03, 2021).

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garganese F., Sanzani S. M., Mincuzzi A., Ippolito A. (2015). First report of Curvularia spicifera causing brown rot of citrus in southern Italy. J. Plant Pathol. 97:3. doi: 10.4454/JPP.V97I3.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Habib W., Masiello M., El Ghorayeb R., Gerges E., Susca A., Meca G., et al. (2021). Mycotoxin profile and phylogeny of pathogenic Alternaria species isolated from symptomatic tomato plants in Lebanon. Toxins 13:513. doi: 10.3390/toxins13080513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza H., Jemni M., Benabderrahim M. A., Mrabet A., Touil S., Othmani A., et al. (2015). “Date palm status and perspective in Tunisia” in Date Palm Genetic Resources and Utilization. eds. Al-Khayri J., Jain S., Johnson D. (Dordrecht: Springer; ) [Google Scholar]

- Hong S. G., Cramer R. A., Lawrence C. B., Pryor B. M. (2005). Alt a 1 allergen homologs from Alternaria and related taxa: analysis of phylogenetic content and secondary structure. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42, 119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huybrechts I., De Ruyck K., De Saeger S., De Boevre M. (2018). Uniting Large-Scale Databeses to Unravel the Impact of Chronic Multi-Mycotoxins Exposures on Colorectal Cancer Incidence in Europe. In: Proceedings of the 2nd MycoKey International Conference, Wuhan, China, 16-18 September 2018. China Agricultural Science and Technology Press, Beijing, China, 181–183.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer - IARC (2002). Some Traditional Herbal Medicines, some Mycotoxins, Naphthalene and Styrene. IARC Monograms on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, vol. 82. IARC, Lyon. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairi M. M. A. (2015). “Date palm status and perspective in Sudan” in Date Palm Genetic Resources and Utilization. eds. Al-Khayri J., Jain S., Johnson D. (Dordrecht: Springer; ) [Google Scholar]

- Khudhair M. W., Jabbar R. A., Dheyab N. S., Hamad B. S., Aboud H. M., Khalaf H. S., et al. (2015). Alternaria radicina causing leaf spot disease of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) in Wasit (middle of Iraq) and its susceptibility to bioassay test of two fungicides. Int. J. Phytopathol. 4, 81–86. doi: 10.33687/phytopath.004.02.1225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for Bimgger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D. P., Gannibal P. B., Dugan F. M., Pryor B. M. (2014). Characterization of Alternaria isolates from the infectoria species-group and a new taxon from Arrhenatherum, Pseudoalternaria arrhenatheria sp. nov. Mycol. Progress 13, 257–276. doi: 10.1007/s11557-013-0910-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D. P., Gannibal P. B., Peever T. L., Pryor B. M. (2013). The sections of Alternaria: formalizing species-group concepts. Mycologia 105, 530–546. doi: 10.3852/12-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann L., Wagner J., Metzler M. (2006). Estrogenic and clastogenic potential of the mycotoxin alternariol in cultured mammalian cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 44, 398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logrieco A., Moretti A., Solfrizzo M. (2009). Alternaria toxins and plant diseases: an overview of origin and occurrence. World Mycotoxin J. 2, 129–140. doi: 10.3920/WMJ2009.1145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malachová A., Sulyok M., Beltrán E., Berthiller F., Krska R. (2014). Optimization and validation of a quantitative liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometric method covering 295 bacterial and fungal metabolites including all regulated mycotoxins in four model food matrices. J. Chromatogr. A 1362, 145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manamgoda D. S., Cai L., McKenzie E. H. C., Crous P. W., Madrid H., Cukeatirote E., et al. (2012). A phylogenetic and taxonomic re-evaluation of the Bipolaris - Cochliobolus - Curvularia complex. Fungal Divers. 56, 131–144. doi: 10.1007/s13225-012-0189-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masiello M., Somma S., Ghionna V., Logrieco A. F., Moretti A. (2019). In vitro and in field response of different fungicides against aspergillus flavus and fusarium species causing ear rot disease of maize. Toxins 11:11. doi: 10.3390/toxins11010011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheron B., Benbadis A. (1990). Contribution to the study of bayoud, fusariosis of the date palm: I. study of the sensitive Deglet-nour cultivar. Can. J. Bot. 68, 2054–2058. [Google Scholar]

- Meena M., Samal S. (2019). Alternaria host-specific (HSTs) toxins: an overview of chemical characterization, target sites, regulation and their toxic effects. Toxicology 6, 745–758. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2019.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namsi A., Rabaoui A., Masiello M., Moretti A., Othmani A., Gargouri S., et al. (2021). First report of leaf wilt caused by Fusarium proliferatum and F. brachygibbosum on date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) in Tunisia. Plant Dis. 105:1217. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-08-20-1791-PDN [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostry V. (2008). Alternaria mycotoxins: an overview of chemical characterization, producers, toxicity, analysis and occurrence in foodstuffs. World Mycotoxin J. 1, 175–188. doi: 10.3920/WMJ2008.x013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palou L., Rosales R., Taberner V., Vilella-Esplá J. (2016). Incidence and etiology of postharvest diseases of fresh fruit of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) in the grove of Elx (Spain). Phytopathol. Mediterr. 55, 391–400. doi: 10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-17819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piombo E., Abdelfattah A., Danino Y., Salim S., Feygenberg O., Spadaro D., et al. (2020). Characterizing the fungal microbiome in date (Phoenix dactylifera) fruit pulp and Peel from early development to harvest. Microorganisms 8:641. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8050641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad V., Upadhyay R. S. (2010). Alternaria alternata f.sp. lycopersici and its toxin trigger production of h₂o₂ and ethylene in tomato. J. Plant Pathol. 92, 103–108. doi: 10.4454/jpp.v92i1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Righetti L., Bergmann A., Galaverna G., Rolfsson O., Paglia G., Dall’Asta C. (2018). Ion mobility derived collision cross section database: application to mycotoxin analysis. Anal. Chim. Acta 1014, 50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2018.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righetti L., Dreolin N., Celma A., McCullagh M., Barknowitz G., Sancho J. V., et al. (2020). Travelling wave ion mobility-derived collision cross section for mycotoxins: investigating interlaboratory and interplatform reproducibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 10937–10943. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Zhang M., Gao L., Yang Q., Kalaji H. M., Qiang S., et al. (2021). Tenuazonic acid-triggered cell death is the essential prerequisite for Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler to infect successfully host Ageratina adenophora. Cells 10:1010. doi: 10.3390/cells10051010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solhaug A., Wisbech C., Christoffersen T. E., Hult L. O., Lea T., Eriksen G. S., et al. (2015). The mycotoxin alternariol induces DNA damage and modify macrophage phenotype and inflammatory responses. Toxicol. Lett. 239, 9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.08.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somma S., Amatulli M. T., Masiello M., Moretti A., Logrieco A. F. (2019). Alternaria species associated to wheat black point identified through a multilocus sequence approach. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 293, 34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenderoth M., Garganese F., Schmidt-Heydt M., Soukup S. T., Ippolito A., Sanzani S. M., et al. (2019). Alternariol as virulence and colonization factor of Alternaria alternata during plant infection. Mol. Microbiol. 112, 131–146. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T. J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor Y. (1990). “Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics” in PCR protocols: A guide to methods and applications. eds. Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H., Sninsky J. J., White T. J. (San Diego, California: Academic Press; ), 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Woudenberg J. H. C., Groenewald J. Z., Binder M., Crous P. W. (2013). Alternaria redefined. Stud. Mycol. 75, 171–212. doi: 10.3114/sim0015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woudenberg J. H. C., Seidl M. F., Groenewald J. Z., de Vries M., Stielow J. B., Thomma B. P. H. J., et al. (2015). Alternaria section Alternaria: species, formae speciales or pathotypes? Stud. Mycol. 82, 1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yekeler H., Bitmis K., Ozcelik N., Doymaz M. Z., Calta M. (2001). Analysis of toxic effects of Alternaria toxins on oesophagus of mice by light and electron microscopy. Toxicol. Pathol. 29, 492–497. doi: 10.1080/01926230152499980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B., Qiang S. (2008). Environmental, genetic and cellular toxicity of tenuazonic acid isolated from Alternaria alternata. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 7, 1151–1156. doi: 10.5897/AJB07.719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Extracted ions chromatogram (XIC) showing the absence of FB1 in blank rice medium.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the GenBank repository, accession numbers ON688310 - ON688454.