Abstract

Background

Monitoring the use of psychoactive substances and substance-related problems in the population allows for the assessment of prevalence and associated health and social consequences.

Methods

The data are derived from the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (ESA) 2021 (n = 9046, 18–64 years). We estimated prevalence rates of the use of tobacco, alcohol, illegal drugs, and psychoactive medications, as well as the prevalence rates of their problematic use (indicating dependence) using screening instruments, and extrapolated the results to the resident population (N = 51 139 451).

Results

Alcohol was the most frequently used substance, with a 30-day prevalence of 70.5% (36.1 million people), followed by non-opioid analgesic drugs (47.4%; 24.2 million) and conventional tobacco products (22.7%; 11.6 million). E-cigarettes were used by 4.3% (2.2 million) and heat-not-burn products by 1.3% (665 000). Among illegal drugs (12-month prevalence), cannabis was the most frequently used (8.8%; 4.5 million), followed by cocaine/crack (1.6%; 818 000) and amphetamine (1.4%; 716 000). Rates of problematic use among the study participants were 17.6% for alcohol (9.0 million), 7.8% for tobacco (4.0 million), 5.7% for psychoactive medications (2.9 million), and 2.5% for cannabis (1.3 million).

Conclusion

The consumption of psychoactive substances continues to be widespread in Germany. In view of the imminent legal changes, the high prevalence of cannabis use and its problematic use need to be taken into consideration.

The use of psychoactive substances is one of the main risk factors for the global burden of disease and premature mortality (1). In 2019, worldwide tobacco use was responsible for approximately 229 million disability-adjusted life years (DALY) and 8.71 million deaths. A total of 2.44 million deaths were attributable to the consumption of alcohol and 494,000 to the use of illegal drugs (2, 3). Thus, based on the total number of annual deaths (56.53 million), a fifth (11.64 million) are accounted for by the use of psychoactive substances (3). Despite an observed decline in the consumption of alcohol since the 1990s, Germany is among the 10 countries worldwide with the highest per capita consumption rates (4, 5). The proportion of smokers in 2019 was also above the West European average (6).

In addition to the high burden of morbidity and mortality, the use of psychoactive substances is associated with significant economic costs, which cannot be compensated for through tax revenue from the sale of legal substances (alcohol, tobacco). According to estimates, the consumption of alcohol in Germany generates annual costs to the economy of approximately 57.04 billion euros (7). The total direct and indirect costs to the economy of tobacco use in 2018 were estimated at 97.42 billion euro (7). The annual expenditure for illicit drug use in Germany in 2010 was put at 5.2–6.1 billion euros (8), while the costs resulting from the harmful use of cannabis were estimated in 2016 to be approximately 975 million euros per year (9).

Monitoring the use of psychoactive substances is an indispensable precondition of health policy decision-making and enables, among other things, an estimation of future costs and the evidence-based development of effective prevention and intervention measures. As a population-representative study, the German Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (ESA) provides data on the use of both legal and illegal substances as well as on hazardous forms of use in the German adult population. The aim of this paper is to provide prevalence estimates of the use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, and psychoactive medications and of negative consequences of substance use in the German adult population.

Methods

Study design and sample

The target group of the ESA 2021 comprises German-speaking individuals aged 18–64 years and living in private households. Sampling was performed using a two-stage selection process. In a first step, 217 municipalities were randomly selected. A random selection of addresses was then made from the respective population registers. In order to make up for the low proportion of young adults in the total population, disproportionate sampling according to age cohorts was carried out. The survey was conducted in writing, via the internet, or by telephone. The adjusted sample comprised 9046 individuals, the response rate was 35.0%. The survey period ran from May to September 2021 in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. For further information on the methodology used for the ESA 2021, the procedure of the survey, the response rate by study arm, as well as prevalence rates according to survey mode, see eMethods, eFigure, and eTables 1– 3.

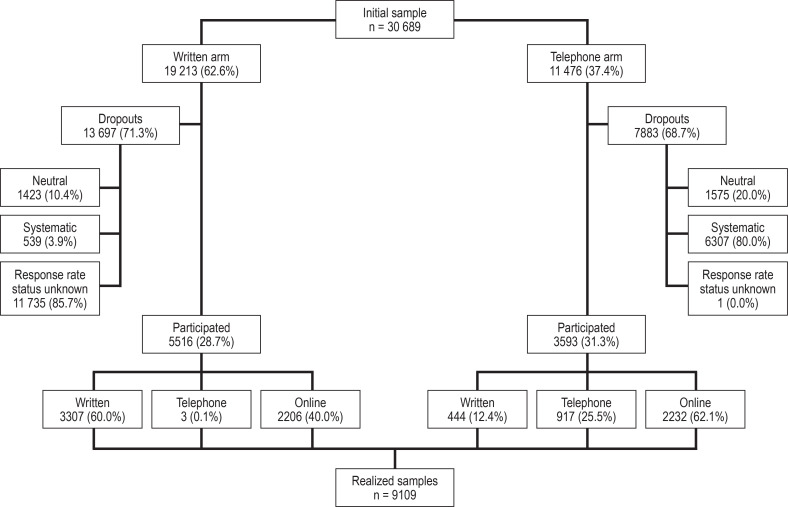

eFigure.

Flowchart of the study design and response rates

eTable 1. Type of response by study arm, n (%).

| Written | Telephone | Total | |

| Initial sample | 19,213 (100) | 11,476 (100) | 30,689 (100) |

| Evaluable questionnaires following data validation | 5467 (28.5) | 3579 (31.2) | 9046 (29.5) |

| Non-evaluable questionnaires following data validation | 49 (0.3) | 14 (0.1) | 63 (0.2) |

| Response status unknown | 11,735 (61.1) | 1 (0.0) | 11,736 (38.2) |

| Neutral dropouts | 1423 (7.4) | 1575 (13.7) | 2998 (9.8) |

| – Target person unknown | 1402 (7.3) | 256 (2.2) | 1658 (5.4) |

| – Telephone number invalid | – | 1193 (10.4) | 1193 (3.9) |

| – Target person does not speak sufficient German | 9 (0.1) | 70 (0.6) | 79 (0.3) |

| – Target person not in target group | 7 (0.0) | 45 (0.4) | 52 (0.2) |

| – Target person deceased | 5 (0.0) | 11 (0.1) | 16 (0.1) |

| Systematic dropouts | 539 (2.8) | 6307 (55.0) | 6846 (22.3) |

| – Refusal | 235 (1.2) | 2934 (25.6) | 3169 (10.3) |

| – Not contactable | 281 (1.5) | 3094 (27.0) | 3375 (11.0) |

| – Health problems | 13 (0.1) | 50 (0.4) | 63 (0.2) |

| – Target person wanted to respond* | 10 (0.1) | 229 (2.0) | 239 (0.8) |

*Target person wished to complete the questionnaire in writing, or complete it online or in a telephone interview, but eventually did not

eTable 3. Substance use prevalence estimates by willingness to participate, n (%)*1.

| Participants (n = 9064) | Non-participants*2 (n = 1231) | |

| Alcohol use | ||

| 30-Day prevalence | 6557 (72.8) | 765 (62.7)*4 |

| Episodic heavy drinking, preceding 30 days*3 | 2247 (25.1) | 384 (52.0)*4 |

| Tobacco use | ||

| 30-Day prevalence | 1716 (19.1) | 264 (21.7) |

| Average number of cigarettes per day, M (SD)*3 | 9.0 (9.1) | 9.5 (8.2) |

| Cannabis use | ||

| Lifetime prevalence | 3358 (37.3) | 332 (27.0)*4 |

| 12-Month prevalence | 1004 (11.2) | 75 (6.1)*4 |

| Medication use, preceding 12 months | ||

| Analgesics | 6636 (73.4) | 831 (67.7)*4 |

| Hypnotics | 498 (5.6) | 74 (6.0) |

*1 Logistic and linear regression model adjusted according to age, sex, federal state, and type of interview

*2 Individuals that completed the “non-response” questionnaire (5.7% of all non-responders)

*3 In relation to 30-day users

*4 Statistically significant difference to “participants” with p < 0.01

M, mean; SD, standard deviation

Instruments

Conventional tobacco products, e-products, and heat-not-burn products

The use of conventional tobacco products (cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, and pipes), waterpipes (hookahs), e-cigarettes, e-waterpipes, e-pipes, e-cigars, and heat-not-burn products was surveyed for the preceding 30 days (10). Daily cigarette consumption was defined as the use of at least one cigarette per day, while heavy cigarette consumption was defined as the use of at least 20 cigarettes per day. To survey dependence on conventional tobacco products and heat-not-burn products over the preceding 12 months, the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (FTND) (e1) was used, while the Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index (PS-ECDI) was used for e-products (e2).

Alcohol

Alcohol consumption was measured for the preceding 30-day time period using a beverage-specific frequency–quantity index separately for beer, wine/sparkling wine, spirits, and mixed alcoholic beverages. Episodic heavy drinking was defined as the consumption of five or more glasses of alcohol (approximately 70 g pure alcohol) on at least one day in the preceding 30 days. The daily consumption of more than 12 g (women) and 24 g (men) of pure alcohol was defined as the threshold for hazardous alcohol consumption (11, 12). The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) was used as an indicator for problematic alcohol consumption (indicating dependence) in the preceding 12 months (e3).

Illegal drugs

The use of cannabis (hashish, marijuana), amphetamine and methamphetamine, ecstasy, LSD, heroin, other opiates (for example, codeine, methadone, opium, and morphine), cocaine/crack cocaine, hallucinogenic mushrooms, and new psychoactive substances (NPS) was recorded for the preceding 12-month period. Problematic use of cannabis, cocaine, and amphetamine/methamphetamine within the preceding 12 months was measured using the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) (e4).

Medications

The use of analgesics, hypnotics and sedatives, analeptics, anorectics, antidepressants, and neuroleptic drugs was surveyed for the preceding 30-day period. Medications taken on a daily basis were also recorded. Problematic use within the preceding 12 months was recorded using the Short Questionnaire on Medication Use (Kurzfragebogen zum Medikamentengebrauch, KFM) (e5).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data on substance use and problematic use are reported as prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals separately for men and women as well as for the total population. Statistically significant differences in prevalence estimates were measured using confidence intervals. Projections to the total resident population in Germany aged 18–64 years were performed based on a population of 51 139 451 individuals (25 940 597 men; 25 198 854 women) as of 31 December 2020 (e6). Post-stratification weights were used to adjust the data to the distribution of the target population in the German adult population in terms of the characteristics age, sex, school education, federal state, and community size class. Due to the complex sample design, the Taylor series linearization method was used to estimate standard errors (e7).

Results

Conventional tobacco products, e-products, heat-not-burn products

The 30-day prevalence of conventional tobacco product use was 22.7% (11.6 million individuals) and, for daily tobacco use, 13.7% (7.0 million individuals) (table 1). Of the tobacco users, 21.0% (2.4 million) reported smoking at least 20 cigarettes a day. Waterpipe use was reported by 4.1 % (2.1 million individuals), e-cigarette use by 4.3% (2.2 million individuals), and heat-not-burn product use by 1.3% (665 000 individuals) (in the preceding 30 days). Men showed higher prevalence rates across all product categories compared to women. Evidence of dependence on tobacco products was seen in 7.8% (4.0 million individuals), on heat-not-burn products in 0.2% (102 000 individuals), and on e-cigarettes in 2.0% (1.0 million individuals) (table 2).

Table 1. 30-Day prevalence of the use of conventional tobacco products, electronic inhalation products, and tobacco heaters, as well as the use of waterpipes (hookahs); extrapolation to the 18- to 64-year-old population.

| Tobacco | Men | Women | Total *4 | Extrapolation *5 | |||||||

| n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | N | [95% CI] | |

| Cigarette, cigar, cigarillo, pipe | 861 | 25.7 | [23.9; 27.6] | 853 | 19.5 | [18.1; 21.1] | 1716 | 22.7 | [21.4; 24.0] | 11.6 M | [10.9; 12.3] |

| Daily use *1 | 414 | 14.3 | [12.8; 16.0] | 505 | 13.2 | [11.9; 14.6] | 919 | 13.7 | [12.6; 14.9] | 7.0 M | [6.4; 7.6] |

| Heavy use *2 (among users) | 139 | 24.8 | [20.6; 29.5] | 104 | 16.2 | [12.6; 20.5] | 243 | 21.0 | [18.2; 24.1] | 2.4 M | [2.0; 3.0] |

| Waterpipe (hookah) | 252 | 5.3 | [4.4; 6.3] | 227 | 3.0 | [2.5; 3.5] | 479 | 4.1 | [3.6; 4.7] | 2.1 M | [1.8; 2.4] |

| E-cigarette, e-waterpipe, e-pipe, e-cigar | 182 | 4.9 | [4.1; 5.9] | 179 | 3.6 | [2.9; 4.6] | 362 | 4.3 | [3.7; 5.0] | 2.2 M | [1.9; 2.6] |

| Heat-not-burn products | 43 | 1.3 | [0.8; 2.1] | 61 | 1.2 | [0.9; 1.7] | 104 | 1.3 | [0.9; 1.7] | 665 | [460; 869] |

| At least one of these products *3 | 1070 | 31.0 | [29.2; 32.9] | 1071 | 23.4 | [21.7; 25.1] | 2144 | 27.2 | [26.0; 28.6] | 13.9 M | [13.3; 14.6] |

*1 Daily use of at least one cigarette

*2 Daily use of at least 20 cigarettes among cigarette users

*3 At least one-time use of cigarettes, cigarillos, pipes, waterpipes, e-cigarettes, e-waterpipes, e-pipes, e-cigars, or heat-not-burn products in the preceding 30 days

*4 Includes men, women, and diverse

*5 Mean based on 51 139 451 individuals aged 18–64 years (as of 31.12.2020, German Federal Statistical Office)

n = Unweighted number; % = weighted prevalence; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; N = projection in thousands except where millions indicated; M, million

Table 2. The 12-month prevalence of substance-related problems based on screening instruments: extrapolation to the 18- to 64-year-old population.

| Problematic use | Men | Women | Total *6 | Extrapolation *7 | |||||||

| n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | N | [95% CI] | |

| Tobacco *1 | 214 | 8.8 | [7.5; 10.2] | 225 | 6.8 | [5.7; 8.1] | 439 | 7.8 | [6.9; 8.8] | 4.0 M | [3.5; 4.5] |

| E-cigarettes *2 | 66 | 2.6 | [1.9; 3.6] | 40 | 1.2 | [0.8; 2.0] | 107 | 2.0 | [1.5; 2.6] | 1.0 M | [767; 1.3] |

| Heat-not-burn products *1 | 6 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.7] | 12 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.5] | 18 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.5] | 102 | [51; 256] |

| Alcohol *3 | 1 049 | 25.0 | [23.1; 26.9] | 655 | 10.1 | [9.1; 11.2] | 1 706 | 17.6 | [16.5; 18.8] | 9.0 M | [8.4; 9.6] |

| Cannabis *4 | 153 | 3.4 | [2.8; 4.2] | 111 | 1.6 | [1.2; 2.2] | 264 | 2.5 | [2.1; 3.0] | 1.3 M | [1.1; 1.5] |

| Cocaine *4 | 20 | 0.5 | [0.3; 1.0] | 14 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.4] | 34 | 0.4 | [0.2; 0.6] | 205 | [102; 307] |

| Amphetamine/methamphetamine *4 | 17 | 0.4 | [0.2; 0.7] | 14 | 0.4 | [0.2; 0.8] | 31 | 0.4 | [0.2; 0.6] | 205 | [102; 307] |

| At least one drug *4 | 170 | 3.7 | [3.0; 4.6] | 27 | 2.0 | [1.5; 2.5] | 297 | 2.9 | [2.4; 3.4] | 1.5 M | [1.2. 1.7] |

| Medications *5 | 139 | 4.8 | [3.8; 6.1] | 272 | 6.5 | [5.7; 7.4] | 412 | 5.7 | [5.0; 6.4] | 2.9 M | [2.6; 3.3] |

*1 Based on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence

*2 Based on the Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index

*3 Based on the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test

*4 Based on the Severity of Dependence Scale

*5 Based on the Short Questionnaire on Medication Use

*6 Includes men, women, and diverse

*7 Mean based on 51,139,451 individuals aged 18–64 years (as of 31 December 2020, German Federal Statistical Office)

n = Unweighted number; % = weighted prevalence; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; N = extrapolation in thousands except where millions indicated; M, million

Alcohol

A total of 70.5% of respondents (36.1 million individuals) reported having consumed alcohol in the preceding 30 days (table 3). Of these, 33.3% reported at least one episode of heavy drinking—with a higher prevalence seen among men (41.9%) compared to women (23.3%). Among alcohol consumers, 21.9% (7.9 million individuals) reported consuming hazardous quantities of alcohol. Differences between prevalence rates among men (21.1%) and women (22.9%) were not statistically significant. Overall, 17.6% of respondents (9 million individuals) exhibited problematic alcohol use (table 2).

Table 3. 30-Day prevalence of alcohol use; extrapolation to the 18- to 64-year-old population.

| Alcohol | Men | Women | Total *3 | Extrapolation *4 | |||||||

| n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | N | [95% CI] | |

| Prevalence of use | 2987 | 74.8 | [72.6; 76.8] | 3561 | 66.0 | [64.0; 68.0] | 6557 | 70.5 | [68.9; 72.0] | 36.1 M | [35.2; 36.8] |

| Episodic heavy drinking *1 (among consumers) | 1319 | 41.9 | [39.5; 44.3] | 919 | 23.3 | [21.5; 25.3] | 2239 | 33.3 | [31.6; 35.0] | 12.0 M | [11.1; 12.9] |

| Consumption of hazardous quantities *2 (among consumers) | 595 | 21.1 | [19.3; 23.1] | 815 | 22.9 | [20.8; 25.0] | 1410 | 21.9 | [20.5; 23.4] | 7.9 M | [7.2; 8.6] |

*1 Episodic heavy drinking: consumption of five or more alcoholic beverages on at least one of the preceding 30 days

*2 Hazardous consumption: average consumption of more than 12 g (women) and 24 g (men) pure alcohol per day

*3 Includes men, women, and diverse

*4 Mean based on 51,139,451 individuals aged 18–64 years (as of 31.12.2020, German Federal Statistical Office)

n = Unweighted number; % = weighted prevalence; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; N = extrapolation in thousands except where millions indicated; M, million

Illegal drugs

With a 12-month prevalence of 8.8% (4.5 million individuals), cannabis was the most frequently used illegal drug, followed by cocaine/crack cocaine with 1.6% (818 000 individuals; Table 4). In total, 1.4% of participants (716 000 individuals) reported having used amphetamine, while 1.3% (665 000 individuals) reported NPS use. At 0.2% (102 000 individuals), the 12-month prevalence for the use of methamphetamine was the lowest. A statistically significantly higher prevalence was seen among men compared to women for cannabis, cocaine/crack cocaine, and the use of at least one illegal drug. With a prevalence of 2.5% (1.3 million individuals), problematic drug use according to SDS criteria can be seen particularly in relation to cannabis (table 2). In this group, men were more frequently affected (with a prevalence of 3.4%) compared to women (1.6%). Prevalence rates for problematic use of cocaine and amphetamine/methamphetamine according to SDS criteria were both 0.4% (205,000 individuals). Sex differences in the 12-month prevalence of these substances were not statistically significant.

Table 4. 12-Month prevalence of illegal drug use; extrapolation to the 18- to 64-year-old population.

| Illegal drugs | Men | Women | Total *1 | Extrapolation *2 | |||||||

| n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | N | [95% CI] | |

| Cannabis | 523 | 10.7 | [9.3; 12.3] | 477 | 6.8 | [5.8; 8.0] | 1004 | 8.8 | [7.7; 10.0] | 4.5 M | [3.9; 5.1] |

| Amphetamine/methamphetamine | 72 | 1.5 | [1.1; 1.9] | 62 | 1.3 | [0.9; 1.8] | 134 | 1.4 | [1.1; 1.8] | 716 | [563; 921] |

| Amphetamine | 71 | 1.5 | [1.1; 1.9] | 62 | 1.3 | [0.9; 1.8] | 133 | 1.4 | [1.1; 1.7] | 716 | [563; 869] |

| Methamphetamine | 8 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.5] | 4 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.8[ | 12 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.5] | 102 | [51; 256] |

| Ecstasy | 77 | 1.4 | [1.0; 1.9] | 45 | 0.7 | [0.5; 1.0] | 122 | 1.0 | [0.8; 1.3] | 511 | [409; 665] |

| LSD | 52 | 0.8 | [0.6; 1.2] | 25 | 0.4 | [0.3; 0.8] | 77 | 0.6 | [0.5; 0.9] | 307 | [256; 460] |

| Heroin/other opiates | 27 | 0.6 | [0.4; 1.0] | 18 | 0.5 | [0.2; 0.9] | 45 | 0.5 | [0.4; 0.8] | 256 | [205; 409] |

| Cocaine/crack cocaine | 90 | 2.1 | [1.5; 2.8] | 60 | 1.1 | [0.7; 1.6] | 150 | 1.6 | [1.2; 2.1] | 818 | [614; 1.1] |

| Hallucinogenic mushrooms | 42 | 0.7 | [0.5; 1.0] | 17 | 0.4 | [0.2; 0.7] | 59 | 0.5 | [0.4; 0.8] | 256 | [205; 409] |

| New psychoactive substances | 56 | 1.5 | [1.0; 2.1] | 66 | 1.2 | [0.8; 1.6] | 122 | 1.3 | [1.0; 1.7] | 665 | [511; 869] |

| At least one of these drugs | 558 | 11.6 | [10.0; 13.4] | 518 | 7.6 | [6.4; 8.9] | 1080 | 9.6 | [8.4; 11.0] | 4.9 M | [4.3; 5.6] |

*1 Includes men, women, and diverse

*2 Mean based on 51,139,451 individuals aged 18–64 years (as of 31.12.2020, German Federal Statistical Office)

n = Unweighted number; % = weighted prevalence; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; N = extrapolation in thousands except where millions indicated; M, million

Medications

Non-opioid analgesics were the medications most commonly used, with a 30-day prevalence of 47.7% (24.2 million individuals) (table 5). The second most commonly used medications were reported to be hypnotics or sedatives (5.4%; 2.8 million individuals), followed by antidepressants (5.3%; 2.7 million individuals) and opioid analgesics (2.1%; 1.1 million individuals). In total, 51.4% (26.2 million individuals) reported having used at least one medication in the preceding 30 days, with the percentage for women (60.6%) being statistically significantly higher than that for men (42.5%). Among the users of the respective medication group, antidepressants (90.4%; 2.5 million individuals) were those most frequently used daily, followed by neuroleptics (83.9%; 601,000 individuals) and anorectics (57.2%; 117,000 individuals). Non-opioid analgesics were the medications most rarely used daily (6.9%; 1.7 million individuals), with the percentage for men (9.8%) being statistically significantly higher than that for women (5.0%). In total, 18.9% of medication users (5.0 million individuals) reported using at least one of the abovementioned medications daily. Finally, 17.6% of respondents (2.9 million individuals) exhibited problematic alcohol use (table 2).

Table 5. 30-Day prevalence of medication use and daily use; extrapolations to the 18- to 64-year-old population.

| Medications | Men | Women | Total *1 | Extrapolation *2 | |||||||

| n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | n | % | [95% CI] | N | [95% CI] | |

| Prevalence of use | |||||||||||

| Non-opioid analgesics | 1417 | 38.0 | [35.9; 40.2] | 2872 | 57.1 | [55.4; 58.8] | 4293 | 47.4 | [46.0; 48.8] | 24.2 M | [23.5; 25.0] |

| Opioid analgesics | 58 | 2.0 | [1.5; 2.6] | 84 | 2.3 | [1.7; 2.9] | 142 | 2.1 | [1.7; 2.5] | 1.1 M | [869; 1.3] |

| Hypnotics or sedatives | 152 | 4.3 | [3.5; 5.3] | 297 | 6.5 | [5.6; 7.4] | 450 | 5.4 | [4.8; 6.0] | 2.8 M | [2.5; 3.1] |

| Analeptics | 44 | 1.0 | [0.6; 1.4] | 38 | 0.6 | [0.4; 0.8] | 82 | 0.8 | [0.6; 1.0] | 409 | [307; 511] |

| Anoretics | 6 | 0.2 | [0.1; 0.6] | 16 | 0.7 | [0.4; 1.2] | 22 | 0.4 | [0.2; 0.7] | 205 | [102; 358] |

| Antidepressants | 140 | 4.7 | [3.8; 5.8] | 269 | 6.0 | [5.2; 6.8] | 410 | 5.3 | [4.7; 6.0] | 2.7 M | [2.4; 3.1] |

| Neuroleptics | 41 | 1.4 | [1.0; 2.1] | 57 | 1.3 | [1.0; 1.8] | 99 | 1.4 | [1.1; 1.8] | 716 | [563; 921] |

| At least one of these medications | 1558 | 42.5 | [40.3; 44.7] | 3023 | 60.6 | [58.8; 62.3] | 4586 | 51.4 | [50.0; 52.8] | 26.2 M | [25.6; 27.0] |

| Daily use | |||||||||||

| Non-opioid analgesics | 105 | 9.8 | [7.7; 12.5] | 92 | 5.0 | [3.6; 6.8] | 197 | 6.9 | [5.6; 8.5] | 1.7 M | [1.3; 2.1] |

| Opioid analgesics | 22 | 32.1 | [20.3; 46.7] | 30 | 46.3 | [32.8; 60.3] | 52 | 39.6 | [30.3; 49.8] | 425 | [263; 636] |

| Hypnotics or sedatives | 43 | 33.1 | [24.3; 43.3] | 56 | 24.0 | [18.2; 30.9] | 99 | 27.7 | [22.7; 33.2] | 764 | [557; 1.0] |

| Analeptics | 11 | 21.4 | [11.2; 37.1] | 15 | 42.2 | [26.4; 59.7] | 26 | 28.8 | [19.1; 41.0] | 118 | [58; 209] |

| Anorectics | 2 | 63.4 | [16.2; 94.0] | 9 | 55.2 | [26.6; 80.8] | 11 | 57.2 | [32.4; 78.8] | 117 | [33; 281] |

| Antidepressants | 123 | 89.7 | [82.5; 94.1] | 241 | 91.0 | [86.3; 94.3] | 365 | 90.4 | [86.8; 93.2] | 2.5 M | [2.1; 2.9] |

| Neuroleptics | 36 | 90.2 | [77.9; 96.0] | 39 | 76.6 | [61.6; 87.0] | 76 | 83.9 | [74.8; 90.2] | 601 | [420; 830] |

| At least one of these medications | 268 | 22.3 | [19.3; 25.5] | 399 | 16.5 | [14.7; 18.5] | 668 | 18.9 | [17.2; 20.8] | 5.0 M | [4.4; 5.6] |

*1 Includes men, women, and diverse

*2 Mean based on 51,139,451 individuals aged 18–64 years (as of 31.12.2020, German Federal Statistical Office)

n = Unweighted number; % = weighted prevalence; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; N = extrapolation in thousands except where millions indicated; M, millions

Discussion

Conventional tobacco products, e-products, and heat-not-burn products

With the proportion of smokers exceeding a fifth (22.7%; 11.6 million individuals), the use of conventional tobacco products among 18- to 64-year-olds is widespread in Germany. Thus in 2020, of the 27 EU Member States (plus Great Britain), Germany ranked 16th on a list in descending order of smoking prevalence (13). According to results of the German Study on Tobacco Use (DEBRA), a nationally representative survey, the prevalence of tobacco use in 2021, including adolescents and older individuals (≥ 14 years), was approximately 30% (14). Smoking is one of the largest preventable risk factors for a multitude of physiological diseases (including, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases as well as cancer) and is considered to be the cause of around 125 000 deaths each year in Germany (15). Studies show that only total abstinence from smoking can be considered as harmless to health (e8). In view of this, it is even more concerning that only one in five German smokers reports attempts to quit (16). The same study shows that e-cigarettes (both with and without nicotine) as an alternative to smoking are the most commonly used single form of aid during any attempt to quit smoking. According to recent evidence, e-cigarette vaporization is less harmful to health than smoking tobacco cigarettes (17), but it is not considered safe (18). In particular adolescents and young adults are at increased risk for taking up e-cigarette use—and thus also for the associated health risks—due to the multitude of flavors on offer (19). Overall, the percentage of e-cigarette users among the adult population is relatively low at 4.3%; the same applies to the percentage of heat-not-burn product users, which at 1.3%, is significantly lower than that of e-cigarette users. However, the prevalence rates among young adults of exclusive use of alternative products, such as heat-not-burn products, waterpipes (hookah), or e-cigarettes, are markedly higher compared to those among older age groups (20).

Alcohol

With a 30-day prevalence of 70.5%, alcohol is the most frequently used psychotropic substance in Germany. The consumption of large quantities of alcohol has been shown to be associated with an increased risk for a wide range of non-communicable diseases (e9). While the consumption of high-risk amounts of alcohol over a prolonged period of time is associated in particular with chronic diseases (for example, cardiovascular disease or cancer), episodic heavy drinking predominantly leads to acute diseases and injuries, including harm to others as a result of traffic accidents or alcohol use during pregnancy (21, 22). Studies also suggest that blackouts caused by binge drinking, particularly in adolescents, can increase the risk of an alcohol use disorder, in addition to massive brain and nervous system damage (23, 24). The available results show that 17.6% of alcohol consumers surveyed exhibit problematic alcohol consumption. Results of the DEBRA study point to a comparable prevalence (19.4%) (25).

Illegal drugs

With a 12-month prevalence of 8.8%, cannabis is the most frequently used illegal substance. A rise in the prevalence of use in recent years has been reported both throughout Europe (26) and in Germany (5).

A comparison of the last ESA survey in 2018 also shows a further increase in the 12-month prevalence of cannabis use by 1.7 percentage points (27). Since 2017, medical cannabis has been available on prescription in Germany for certain indications. With approximately 30 000 to 40 000 users of medical cannabis in Germany (28), the majority of the estimated 4.5 million users obtain cannabis from illicit sources. In particular the regular use of cannabis has been shown to be associated with an increased risk for mental health disorders (for example, anxiety disorders, psychoses, depression) (29, 30). In view of the current political debate on legalization in Germany, one should not underestimate the risks and hazards of cannabis use especially to adolescents and young adults (31, 32). The results of the present study show that one in four cannabis users exhibits problematic use.

With the exception of cannabis, the use of other illegal drugs in Germany is much less widespread. Cocaine is the second most commonly used illegal substance; with a prevalence of 1.6%, the consumption of cocaine/crack cocaine exceeds the overall prevalence for Europe (1.2%) (33). At 1.4%, the prevalence of amphetamine use in Germany is twice that of Europe as a whole (0.7%). The use of NPS (1.3%) is far more widespread in Germany than the use of methamphetamine (0.2%) and, compared to results from 15 countries with available data, is significantly higher than the average value of 0.6% (33).

Medications

With around 24.2 million users, non-opioid analgesics are the most frequently used group of medications in Germany. These pain medications that are available over the counter from pharmacies are used primarily to treat mild to moderate pain, but can cause serious side effects if used improperly (34, 35).

The prevalence of non-opioid analgesic abuse among self-medicated users is estimated to be 6.4% (3.2 million individuals) in Germany (36). In contrast, the percentage of people using prescription opioid analgesics is, as expected, lower at 2.1%. Analyses of prescription data show a constant rise in the total number of opioid analgesic prescriptions over the last decade (37). An increase in long-term prescribing (≥ 3 months) for chronic non-cancer-related pain is also evident, despite the fact that there is little evidence of efficacy in this patient group (38, 39).

According to the results of this study, approximately 2.9 million individuals show problematic medication use. One can assume that—in addition to opioid analgesics— hypnotics and sedatives are particularly associated with problematic use, since these drugs have a high dependence potential by virtue of their pharmacological properties (39).

Limitations

Survey data on prevalence rates of use are subject to a number of limitations. For example, one can expect biases due to systematic non-participation by certain user groups (see eMethods Section for non-response analyses). Since all information on substance use is based on self-reporting, the full picture may be underestimated as a result of socially desirable response behavior. With regard to the representativeness of the present study, it is important to note that due to the study design, certain population groups are difficult or impossible to reach. This applies in particular to individuals aged over 64 years, homeless people, as well as people receiving inpatient treatment.

Conclusions

The use of illegal and legal psychoactive substances remains widespread in Germany. Alcohol is the most frequently used psychotropic substance, followed by non-opioid analgesics and tobacco. Cannabis is the most commonly used illegal substance. Against the backdrop of the planned legislative changes (40), the high prevalence rates of cannabis use as well as its problematic use are likely to spark discussion.

Supplementary Material

eMethods

The Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse 2021: Study Design and Methodology

Study design and sampling

The target population of the 2021 Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (ESA) was made up of German-speaking people aged between 18 and 64 years (born between 1957 and 2003) living in private households, and covers approximately 51.1 million individuals (German Federal Statistical Office, as of 31.12.2020). The sample of persons was drawn in two stages. In the first stage, municipalities (or sample points) were randomly drawn based on municipal statistical data from the German Federal Statistical Office and the statistical offices of the German federal states. Sample points represent equally sized clusters of people drawn directly from the civil registers of the municipalities in the second stage. Municipalities were drawn within stratification cells from the combination of ten municipality size classes while controlling for the distribution of government districts and states. The number of sample points was converted proportionally to the resident population in the age cohorts. Therefore, cities can be represented by several sample points in the sample. A total of 250 sample points were drawn from 217 communities, whereby 25 communities were unable or unwilling to provide addresses. The missing municipalities were made up for with additional draws from the other municipalities. Overall, 192 municipalities (225 sample points) submitted addresses.

Personal addresses were drawn from the population registers by systematic random selection. The number of target subjects in the sample points was chosen in such a way that an initial sample of n = 8000 would be achievable. It was assumed that 50% of the selected individuals would not take part in the survey and 20% would not belong to the target population since they did not fall within the relevant age group, were not German-speaking, or their address was unknown. The uneven distribution of age cohorts in the population required a disproportionate approach, meaning that younger age cohorts were more likely to be selected given that they were not as strongly represented as were older age cohorts. Taking into consideration the disproportionate sample design and the anticipated sample-neutral dropouts per municipality, 900 addresses per sample point were selected. This equated to a gross sample of 30 689 individuals.

Fieldwork implementation

Fieldwork was carried out by the infas Institute for Applied Social Sciences (infas Institut für angewandte Sozialwissenschaften GmbH) between May and September 2021. In order to increase the response rate and minimize the selectivity of the sample, the survey used a mixture of methods comprising written postal surveys, online surveys, and telephone surveys. Depending on whether a telephone number (landline or mobile) could be found, the sample was divided into “telephone” and “written” study arms. All target persons received written correspondence comprising study information, a data privacy statement, an online access code, and an accompanying letter from the German Federal Ministry of Health.

Target persons in the telephone study arm were notified by a trained interviewer that they would be contacted. In the case of an unsuccessful attempt at telephone contact, a written questionnaire was sent in addition to a reminder letter. Individuals in the written study arm received the questionnaire with a postage-prepaid return envelope. If the target persons failed to respond, two reminders were sent at four-week intervals. At any time, respondents were able to switch between survey modes or request an additional written questionnaire. The online questionnaire could be answered on a variety of mobile devices, such as smartphones or tablets.

Instruments

The aim of the survey was to record the use of legal and illegal substances and related problems. In addition to information on the use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, and psychoactive medications, information was also gathered on physical and mental health status, chronic diseases, mental health disorders, and sociodemographics.

Both the online survey and the telephone survey were based on the written questionnaire. It was sometimes necessary in the online survey to optimize the layout and presentation of certain question batteries for mobile devices. In an additional module in the online survey, cannabis users were asked in-depth questions about their use of cannabis. The full questionnaire can be found at www.esa-survey.de/studie/instrumente.html.

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographic characteristics were recorded in line with the demographic standards of the German Federal Statistical Office (e10). Information on the following was gathered: sex and year of birth, migrant background (country of birth and citizenship) of the respondent and their parents, family situation (marital status, children, household size), education (schooling, vocational training), employment (employment status, occupational position) and net household income.

Health and health-related behavior

Physical and mental health were recorded by means of two five-point ratings (response categories 1 = “very good” to 5 = “very poor”). Chronic diseases were defined as diseases of at least 4 weeks‘ duration and requiring continuous monitoring and treatment. Applicable diseases could be specified from a list. This included the categories “cancer,” “osteoarthritis,” “arthritis,” “complaints in the neck region,” “knee complaints,” “headache (migraine),” “nervous system damage,” “muscle pain,” “neurological disease,” and “other.”

Screening for mental disorders was carried out using 11 questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, e11). These related to the preceding 12 months and included the presence of psychosomatic complaints, anxiety disorders (panic, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, fear of public places), depression, mania, and post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as psychiatric, psychological, or psychotherapeutic treatment or a finding of mental or psychosomatic illness.

Substance use

Both 30-day and 12-month prevalence rates were collected for all substances. The lifetime prevalence was recorded for the use of all substances except medications.

Use of tobacco and smoking alternatives

The survey included conventional tobacco products such as cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, and pipes, as well as smoking and tobacco alternatives such as e-cigarettes (these include e-cigars, e-waterpipes, and e-pipes), tobacco heaters, and waterpipes (hookahs). With the exception of waterpipes, the number of days of use in the preceding 30 days as well as the average amount used per day of use were recorded for these products alongside prevalence.

Alcohol use

The average amount of alcohol consumed was recorded using a quantity–frequency index separately for beer, wine/sparkling wine, spirits, and alcoholic mixed drinks. This was derived from data on the number of days on which the respective beverages were consumed and the number of units consumed on a typical day of consumption. To calculate the amount of pure alcohol in grams, the per-liter data for the beverages were used based on the beverage-specific alcohol contents and the number of units consumed. The beverage-specific alcohol contents (beer: 4.8 vol. %; wine/sparkling wine: 11.0 vol. %; spirits: 33.0 vol. %) respectively correspond to an amount of alcohol of 38.1 g, 87.3 g, and 262.0 g pure alcohol per liter (e12). For alcoholic mixed beverages, the average alcohol content of a glass (0.3–0.4 l) was assumed to be 0.04 l of spirits. An individual average daily amount was derived from the calculated pure alcohol in grams. Five categories were formed on the basis of recommended daily limits for low-risk alcohol consumption:

Episodic heavy drinking was recorded using an open-response format regarding the number of days on which five or more glasses of alcohol were consumed, irrespective of whether these were beer, wine/sparkling wine, spirits, or mixed alcoholic beverages (approximately 14 g of pure alcohol per glass, that is to say, at least 70 g of pure alcohol).

Use of (illegal) drugs

Prevalence and frequency were recorded for the use of cannabis (hashish, marijuana), stimulants (amphetamine, speed), methamphetamine (crystal meth), ecstasy (MDMA), LSD, heroin, other opiates (for example, codeine, methadone, opium, morphine), cocaine/crack cocaine, inhalants (glue, poppers), mushrooms (hallucinogenic substances), or new psychoactive substances (NPS). NPS are substances that imitate the effects of illegal drugs, such as cannabis, ecstasy, cocaine, etc. These are sometimes also referred to as “legal highs,” “research chemicals,” “bath salts,” or “herbal blends.” They are available in different forms, for example, as herbal mixtures, powders, tablets, or liquids.

Medication use

Prior to the questions, each drug group was presented using a list of the most common preparations in order to help respondents classify the drugs they use. In addition to use, the frequency of hypnotics, sedatives, analeptics, anorectics, antidepressants, neuroleptics, and anabolics was also recorded with the following answer categories:

In relation to the preceding 30 days, respondents were asked whether or not the medication had been prescribed by a physician. The prevalence and frequency of analgesic use were recorded in the same way, but separately for opioid and non-opioid analgesics. In relation to the preceding 12 months, respondents were asked whether these drugs had been prescribed exclusively, partially, or not at all by a physician.

Problematic substance use

Problematic substance use (indicating dependence) in the 12 months prior to the interview was recorded using substance-specific screening scales. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT, e3) was used for alcohol, the Fagerström Test (FTND, e1) for nicotine dependence in the context of conventional tobacco products and tobacco heaters, the Penn State Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index (PS-ECDI, e2) for e-cigarettes, the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS, e4) for cannabis, cocaine, and amphetamine/methamphetamine, as well as a Short Questionnaire on Medication Use (Kurzfragebogen zum Medikamentengebrauch, KFM) for medications (e5). Problematic use was assumed on the basis of the following threshold values: AUDIT (at least 8 of 40 possible points) (e13, e14), FTND (at least 4 of 10 possible points) (e1, e15), PS-ECDI (at least 4 of 20 possible points) (e16), SDS (out of 15 possible points in each case for: cannabis, at least 2 points, cocaine: at least 3 points, amphetamine/methamphetamine: at least 4 points) (e4), KFM (at least 4 of 11 possible points) (e5).

The items in the substance-specific screening scales were only given to those respondents that had reported use of the respective substance or relevant medication in the preceding 12 months.

The realized sample

Of the initial sample (n = 30 689), 19 213 (62.6 %) were in the written study arm and 11 476 (37.4%) in the telephone study arm. The number of dropouts in the written study arm was n = 13 697 (71.3%) and in the telephone arm n = 7883 (68.7%). Most of the participants in the telephone arm answered the questionnaire online (62.1%). In this arm, 25.5% responded via telephone interviews and 12.4% answered the questionnaire using the written postal mode. Participants in the written study arm were those most likely to use the written postal questionnaire (60.0%), followed by the online questionnaire (40.0%). Only 0.1% in this arm took part in a telephone interview. In total, n = 9109 individuals (realized sample) took part in the survey (efigure).

Response rate

The response rate was calculated as the proportion of realized cases in the initial sample, with the latter being adjusted for neutral dropouts with no systematic influence on sample selection. The following response statuses were defined as neutral dropouts: “person unknown,” “invalid telephone number,” “person does not speak German,” “person does not fulfill the selection criteria,” or “person deceased.” The total rate of neutral dropouts was 9.8%, whereby it was higher in the telephone study arm (13.7%) compared to the written study arm (7.4%). The shares of response statuses shown in eTable 1 for both study arms form the basis for the calculation of response rate. These include evaluable questionnaires (29.5%), response status unknown (38.2%), and systematic non-response (22.3%). The latter relates to individuals that were in principle available for the study, but did not participate, i.e., they explicitly declined to participate, could not be contacted during the fieldwork period, could not be questioned due to health problems, failed to return the questionnaire or complete it online despite notification, or failed to keep a telephone appointment. These systematic dropouts were significantly higher in the telephone study arm than in the written arm (55.0% versus 2.8%). In both arms, most dropouts were due to refusal to participate or non-contactable status. In the course of the data review, a further 63 cases needed to be excluded from the 9109 cases realized. Thus the number of valid and evaluable cases came to 9046 individuals.

The percentage of neutral dropouts (n = 2998) among people with known response status (n = 18 953) comes to 15.8%. The percentage of neutral dropouts among persons with no response status (n = 11 736) is unknown and is estimated to be the same share, n = 1856 (15.8% of n = 11 736). There were 4854 neutral dropouts in total, and the sample adjusted for neutral dropouts was n = 25 835. Thus, with n = 9046 analyzable cases, the response rate was 35.0%.

Weighting

In order to be able to make representative statements for the German population aged between 18 and 64 years using the ESA 2021, three weights were calculated: one design weight and one redressement weight each for cross-sectional analyses and trend analyses.

The design weight is intended to offset the disproportionate sampling according to age cohorts and is inversely proportional to the selection probability. This weighting factor takes a minimum value of 0.42 and a maximum of 1.70. The effect of weighting is evaluated using the effectiveness measure E and the resulting effective sample size. E = 86.4% was calculated and this reduces the effective sample size from n = 9046 to n = 7816. The effective sample size tells us how large a simple random sample without weighting could have been in order to yield results of comparable precision to the complex sample (e17– e19). This means that, due to the complex sample design required for Germany-wide representativeness, the effectiveness of the realized sample fell to 86.4%. This level of effectiveness is comparable to similar studies (e20).

The redressement weights are intended to adjust the marginal distributions of certain external characteristics to the population; this minimizes bias due to non-response. An iterative proportional fitting algorithm is used to this end (e21). The design weights are contained in the redressement weights. The redressement weight of the cross-sectional analyses adjusts the marginal distributions of the characteristics federal state, district size, sex, and highest school-leaving qualification in the 18- to 64-year-old population to the 2019 microcensus (e21). The inclusion of further characteristics increases the variance of the weighting factors, which range in value from 0.86 to 10.25. This yields an E of 57.4% and an effective sample size of n = 5192. Again, this level of effectiveness is comparable to that in similar studies (e20).

Mode effects

The survey mode in the ESA 2021 could be freely chosen, meaning that mode effects need to be taken into consideration. Almost half (49.0%) of participants completed the questionnaire online, while 40.9% preferred the written postal route and 10.1% took part in a telephone interview. Participants differed on the basis of sociodemographic variables. Whereas in the telephone interview the weighted percentages of men and women were largely balanced (51.4% versus 48.6%), these were higher for women in the written (56.1%) and for men in the online survey (56.5%). The average age of participants was 47 years for telephone interviews, 42 years for the written survey, and 40 years for the online survey. The weighted percentage of individuals with a general qualification for university entrance was higher in the online (46.2%) and written postal surveys (39.6 %) compared to the telephone interview (29.3%).

eTable 2 shows statistically significant differences in substance use data. Here, individual characteristics that influence the choice of survey mode were controlled for. It becomes apparent that in particular internet-based responses significantly differ from responses made in the written survey. Only in the prevalence of alcohol use in the preceding 30 days and hypnotics in the preceding 12 months are there no significant differences across survey methods. Participants in the written postal survey show higher prevalence rates in all substances compared to those in the online survey. In particular, one sees a higher 30-day prevalence of smoking (24.3% versus 20.7%) and use of analgesics in the preceding 12 months (73.4% versus 69.6%).

Non-response effects

In order to better assess non-response bias, non-participants were asked to respond to a short one-page questionnaire. In all, 1231 individuals expressed their willingness to do so. eTable 3 shows a comparison of selected prevalence rates with the study population. With the exception of the prevalence of tobacco use, statistically significant differences between the two populations can be seen. For example, the prevalence of episodic heavy drinking in the preceding 30 days is higher among non-participants (52.0% versus 25.1%). On the other hand, the lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates of cannabis use are lower among non-participants compared to participants (27.0% versus 37.3% and 6.1% versus 11.2%, respectively).

Representativity

The aim of the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse is to enable population-representative statements on substance use and problematic patterns of use in the general population aged 18–64 in Germany. Using weightings, the distribution of the characteristics federal state, municipality size class (according to the German system for classifying municipalities), sex, birth cohort, and schooling is adjusted to the distribution in the population. Biases in the analyses due to non-response were minimized by these weightings as well as by making a variety of survey methods available.

The number of participants in the ESA 2021 of 9046 corresponds to the desired sample size. At 35.0%, the response rate has fallen further compared to previous surveys (ESA 2015: 52.2%; ESA 2018: 41.6%). A comparable population-representative study (General Population Survey of the Social Sciences [Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften, ALLBUS]) conducted in 2018 shows a similar response rate of 32.4% (e23).

A higher initial sample was needed in the 2021 ESA compared to the 2018 ESA (30 689 versus 25 158). This can be attributed to a higher proportion of target persons compared to 2018 (2021: 62.6% 2018: 40.4%) in the written study arm, among which there is a high proportion (85.7% or n = 11 735) of target subjects with unknown response status. Overall, there has been a significant decline in the number of telephone interviews conducted, which currently make up 10% of the surveys conducted. In 2018, the share was 29%. The analysis of mode effects on the prevalence of the various substances points to differences between survey modes also when controlling for sociodemographic variables. The lower prevalence of cannabis use in the telephone interviews compared to the other interview modes could indicate bias arising from respondents’ tendency to give socially desirable responses. In contrast to self-completed questionnaires, either in writing or online, telephone surveys are conducted by interviewers.

In addition, the non-response analysis showed statistically significant differences between participants and non-participants. The differences point in a similar direction to those in the ESA 2018. However, the results of the comparison need to be interpreted with caution, since only 5.7% of all non-participants filled out the non-response questionnaire. One can assume that individuals with an interest in the topic participated in the survey. In the case of substances that are largely socially normalized, such as alcohol, tobacco, as well as cannabis, one can assume fairly low biases in general prevalence estimates. It is important to note that highly marginalized groups of people (homeless individuals or prison inmates) are not part of the target population, since they do not live in private homes. However, in these and other subgroups, it is safe to assume that consumption behavior is high and excessive in some cases. Thus, one can assume a possible underestimation of prevalence rates for substance use as well as consumption patterns with higher distribution in these groups of people.

Lifelong abstinence

Abstinent in the preceding 12 months

Abstinent in the preceding 30 days

Low-risk consumption (men: ≤ 24 g, women: ≤ 12 g)

High-risk consumption (men: >24 g, women: > 12 g).

Not used

Less than once a week

Once a week

Several times a week

Daily.

eTable 2. Substance use prevalence estimates by survey mode, n (weighted %) *1.

| Written (n = 3696) | Telephone (n = 916) | Online(n = 4434) | |

| Alcohol use | |||

| 30-Day prevalence | 2636 (69.0) | 673 (70.6) | 3248 (71.7) |

| Episodic heavy drinking, preceding 30 days*2 | 913 (35.6) | 188 (26.9)*3 | 1138 (32.8)*4 |

| Tobacco use | |||

| 30-Day Prevalence | 761 (24.3) | 188 (24.7) | 767 (20.7)*4 |

| Average number of cigarettes per day, M (SD)*2 | 11.9 (11.2) | 11.4 (8.8) | 9.8 (8.3)*3 |

| Cannabis use | |||

| Lifetime prevalence | 1462 (37.3) | 221 (21.5)*4 | 1675 (35.4)*4 |

| 12-Month prevalence | 416 (9.4) | 56 (4.2)*3 | 532 (9.3)*3 |

| Medication use, preceding 12 months | |||

| Analgesics | 2777 (73.4) | 687 (73.1) | 3172 (69.6)*3 |

| Hypnotics | 233 (6.3) | 46 (4.9) | 219 (5.0) |

*1 Adjusted for age, sex, federal state, school education, and household income (control variables) with logistic or linear regression models

*2 In relation to 30-day users

*3 Statistically significant difference to “written” with p < 0.05

*4 Statistically significant difference to “written” with p < 0.01

M, mean; SD, standard deviation

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Christine Rye.

Footnotes

Funding

The 2021 German Epidemiological Addiction Survey (ESA) was funded by the Federal Ministry of Health (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit, BMG) (Ref: ZMVI1–2520DSM203). Funding is not subject to conditions.

Conflict of interests statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interests exists.

References

- 1.Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S, et al. Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction. 2018;113:1905–1926. doi: 10.1111/add.14234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223–1249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange GHDx, GBD Results Tool Permalink. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/a1edd84cef44a2d98889bb6e5774c5d3 (last accessed on 10 February 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manthey J, Shield KD, Rylett M, Hasan OSM, Probst C, Rehm J. Global alcohol exposure between 1990 and 2017 and forecasts until 2030: a modelling study. Lancet. 2019;393:2493–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seitz NN, Lochbühler K, Atzendorf J, Rauschert C, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T, Kraus L. Trends in substance use and related disorders—analysis of the Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse 1995 to 2018. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:585–591. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reitsma MB, Kendrick PJ, Ababneh E, et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397:2337–2360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01169-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Effertz T. Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen, editor. Die volkswirtschaftlichen Kosten von Alkohol-und Tabakkonsum in Deutschland. Jahrbuch Sucht. Lengerich: Pabst. 2020:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mostardt S, Flöter S, Neumann A, Wasem J, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T. Schätzung der Ausgaben der öffentlichen Hand durch den Konsum illegaler Drogen in Deutschland. Das Gesundheitswesen. 2010;72:886–894. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Effertz T, Verheyen F, Linder R. Ökonomische und intangible Kosten des Cannabiskonsums in Deutschland. Sucht. 2016;62:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. WHO. Geneva: 1998. Guidelines for controlling and monitoring the tobacco epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burger M, Brönstrup A, Pietrzik K. Derivation of tolerable upper alcohol intake levels in Germany: a systematic review of risks and benefits of moderate alcohol consumption. Prev Med. 2004;39:111–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seitz H, Bühringer G, Mann K. Grenzwerte für den Konsum alkoholischer Getränke. Jahrbuch Sucht. 2008;7:205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Commission. Special Eurobarometer 506: Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes. Europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2240 (last accessed on 21 June 2022) 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 14.DEBRA. Deutsche Befragung zum Rauchverhalten. www.debra-study.info/ (last accessed on 15 March 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mons U, Brenner H. Demographic ageing and the evolution of smoking-attributable mortality: the example of Germany. Tob Control. 2017;26 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotz D, Batra A, Kastaun S. Smoking cessation attempts and common strategies employed—a Germany-wide representative survey conducted in 19 waves from 2016 to 2019 (The DEBRA Study) and analyzed by socioeconomic status. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117:7–13. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC. The National Academies Press. 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keith R, Bhatnagar A. Cardiorespiratory and immunologic effects of electronic cigarettes. Curr Addict Rep. 2021;8:336–346. doi: 10.1007/s40429-021-00359-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sapru S, Vardhan M, Li Q, Guo Y, Li X, Saxena D. E-cigarettes use in the United States: reasons for use, perceptions, and effects on health. BMC Public Health. 2020;20 doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09572-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraus L, Möckl J, Rauschert C, Seitz NN, Lochbühler K, Olderbak S. Changes in the use of tobacco, alternative tobacco products, and tobacco alternatives in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;117:535–541. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2022.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smyth A, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease, cancer, injury, admission to hospital, and mortality: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386:1945–1954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraus L, Seitz NN, Shield KD, Gmel G, Rehm J. Quantifying harms to others due to alcohol consumption in Germany: a register-based study. BMC Med. 2019;17 doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1290-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermens DF, Lagopoulos J. Binge drinking and the young brain: a mini review of the neurobiological underpinnings of alcohol-induced blackout. Front Psychol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuen WS, Chan G, Bruno R, et al. Trajectories of alcohol-induced blackouts in adolescence: early risk factors and alcohol use disorder outcomes in early adulthood. Addiction. 2021;116:2039–2048. doi: 10.1111/add.15415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garnett C, Kastaun S, Brown J, Kotz D. Alcohol consumption and associations with sociodemographic and health-related characteristics in Germany: a population survey. Addict Behav. 2022;125 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107159. 107159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manthey J, Freeman TP, Kilian C, López-Pelayo H, Rehm J. Public health monitoring of cannabis use in Europe: prevalence of use, cannabis potency, and treatment rates. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;10 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100227. 100227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atzendorf J, Rauschert C, Seitz NN, Lochbühler K, Kraus L. The use of alcohol, tobacco, illegal drugs and medicines—an estimate of consumption and substance-related disorders in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:577–584. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitteilungen des BDE. Der Diabetologe. 2022;18:90–92. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gahr M, Ziller J, Keller F, Muche R, Preuss UW, Schönfeldt-Lecuona C. Incidence of inpatient cases with mental disorders due to use of cannabinoids in Germany: a nationwide evaluation. Eur J Public Health. 2022;32:239–245. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckab207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobbs M, Kalk NJ, Morrison PD, Stone JM. Spicing it up-synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists and psychosis— a systematic review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:1289–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorenzetti V, Hoch E, Hall W. Adolescent cannabis use, cognition, brain health and educational outcomes: a review of the evidence. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;36:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cyrus E, Coudray MS, Kiplagat S, et al. A review investigating the relationship between cannabis use and adolescent cognitive functioning. Curr Opin Psychol. 2021;38:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Europäische Beobachtungsstelle für Drogen und Drogensucht (EMCDDA) Europäischer Drogenbericht 2021: Trends und Entwicklungen. Luxemburg: Amt für Veröffentlichungen der Europäischen Union. www.pvtweb.de/fileadmin/user_upload-/Dateien_zum_Download/Europ_Drogenbericht_2021_2021.2256_DE0906.pdf (last accessed on 21 June 2022) 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fendrick AM, Pan DE, Johnson GE. OTC analgesics and drug interactions: clinical implications. Osteopath Med Prim Care. 2008;2 doi: 10.1186/1750-4732-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bindu S, Mazumder S, Bandyopadhyay U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: a current perspective. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;180 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rauschert C, Seitz N-N, Olderbak S, Pogarell O, Dreischulte T, Kraus L. Abuse of non-opioid analgesics in Germany: prevalence and associations among self-medicated users. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.864389. 864389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.BAH - Bundesverband der Arzneimittel-Hersteller. Der Arzneimittelmarkt in Deutschland. Zahlen und Fakten aus. www.bah-bonn.de/publikationen/zahlen-fakten/ (last accessed on 21 June 2022) 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinecke H, Weber C, Lange K, Simon M, Stein C, Sorgatz H. Analgesic efficacy of opioids in chronic pain: recent meta-analyses. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:324–333. doi: 10.1111/bph.12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buth S, Holzbach R, Martens MS, Neumann-Runde E, Meiners O, Verthein U. Problematic medication with benzodiazepines, “Z-drugs”, and opioid analgesics—an analysis of national health insurance prescription data from 2006-2016. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:607–614. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD), BÜNDNIS 90 / DIE GRÜNEN, Freie Demokraten (FDP) Mehr Fortschritt wagen. Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit. Koalitionsvertrag 2021 - 2025 zwischen der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands (SPD), BÜNDNIS 90 / DIE GRÜNEN und den Freien Demokraten (FDP) www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/974430/1990812/ 04221173eef9a6720059cc353d759a2b/2021-12-10-koav2021-data. pdf?download=1 (last accessed on 18 March 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E1.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Foulds J, Veldheer S, Yingst J, et al. Development of a questionnaire for assessing dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large sample of ex-smoking E-cigarette users. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17:186–192. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Guidelines for use in primary care. Geneva. World Health Organization. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- E4.Gossop M, Darke S, Griffiths P, et al. The Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS): psychometric properties of the SDS in English and Australian samples of heroin, cocaine and amphetamine users. Addiction. 1995;90:607–614. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9056072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Watzl H, Rist F, Höcker W, Miehle K. Entwicklung eines Fragebogens zur Erfassung von Medikamentenmißbrauch bei Suchtpatienten Sucht und Psychosomatik. Beiträge des 3 Heidelberger Kongresses. In: Heide M, Lieb H, editors. Nagel. Bonn: 1991. pp. 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- E6.Statistisches Bundesamt. Tabelle 12411-0013: Bevölkerung: Bundesländer, Stichtag, Geschlecht, Altersjahre. Verfügbarer Zeitraum: 31.12.1967 - 31.12.2020. www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=12411-0013&bypass=true&levelindex=1&levelid=1647608392301#abreadcrumb (last accessed on 31 December 2020) [Google Scholar]

- E7.Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied survey data analysis. NewYork: Chapman and Hall/CRC. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- E8.Hackshaw A, Morris JK, Boniface S, Tang JL, Milenković D. Low cigarette consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: meta-analysis of 141 cohort studies in 55 study reports. BMJ. 2018;360 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Schaller K, Kahnert S. Alkoholatlas Deutschland 2017. Pabst Science Publishers. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- E10.Beckmann K, Glemser A, Heckel C, et al. Demographische Standards: eine gemeinsame Empfehlung des ADM, Arbeitskreis Deutscher Markt- und Sozialforschungsinstitute eV., der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Sozialwissenschaftlicher Institute e.V. (ASI) und des Statistischen Bundesamtes. Wiesbaden. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- E11.Wittchen HU, Beloch E, Garczynski E, et al. Max-Planck-Institut für Psychiatrie, Klinisches Institut. München: 1995. Münchener Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI), Paper-pencil 22, 2/95. [Google Scholar]

- E12.Bühringer G, Augustin R, Bergmann E, et al. Alkoholkonsum und alkoholbezogene Störungen in Deutschland. Baden-Baden: Nomos. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- E13.Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction. 1995;90:1349–1356. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901013496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Rist F, Scheuren B, Demmel R, Hagen J, Aulhorn I. Glöckner-Rist A, Rist F, Küfner H, editors. Der Münsteraner Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-G-M) Elektronisches Handbuch zu Erhebungsinstrumenten im Suchtbereich (EHES) Version 3. Mannheim. Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden und Analysen. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- E15.Breslau N, Johnson EO. Predicting smoking cessation and major depression in nicotine-dependent smokers. Am J Public Health. 2000;90 doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Morean ME, Krishnan-Sarin S, Sussman S, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the E-cigarette dependence scale. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21:1556–1564. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Gabler S, Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik J, Krebs D. Gewichtung in der Umfragepraxis. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- E18.Lohr SL. Sampling Design and analysis. 3rd edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- E19.Little RJ, Lewitzky S, Heeringa S, Lepkowski J, Kessler RC. Assessment of weighting methodology for the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:439–449. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Robert Koch-Institut. Berlin: 2014. Daten und Fakten: Ergebnisse der Studie „Gesundheit in Deutschland aktuell 2012“. [Google Scholar]

- E21.Gelman A, Carlin J. Poststratification and weighting adjustments Survey nonresponse. In: Groves RM, Eltinge JL, Little RJA, editors. John Wiley and Sons. New York: 2002. pp. 289–303. [Google Scholar]

- E22.Statistisches Bundesamt. Bevölkerungsfortschreibung auf Grundlage des Zensus 2011 - Fachserie 1 Reihe 1.3 - 2020. www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Publikationen/Downloads-Bevoelkerungsstand/bevoelkerungsfortschreibung-2010130207005.html (last accessed on 21 June 2022) [Google Scholar]

- E23.Baumann H, Schulz S, Thiesen S. ALLBUS 2018 - Variable Report [Studien-Nr 5270. Diese Dokumentation bezieht sich auf den Datensatz in Version 2.0.0. doi: 10.4232/1.13250] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

The Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse 2021: Study Design and Methodology

Study design and sampling

The target population of the 2021 Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse (ESA) was made up of German-speaking people aged between 18 and 64 years (born between 1957 and 2003) living in private households, and covers approximately 51.1 million individuals (German Federal Statistical Office, as of 31.12.2020). The sample of persons was drawn in two stages. In the first stage, municipalities (or sample points) were randomly drawn based on municipal statistical data from the German Federal Statistical Office and the statistical offices of the German federal states. Sample points represent equally sized clusters of people drawn directly from the civil registers of the municipalities in the second stage. Municipalities were drawn within stratification cells from the combination of ten municipality size classes while controlling for the distribution of government districts and states. The number of sample points was converted proportionally to the resident population in the age cohorts. Therefore, cities can be represented by several sample points in the sample. A total of 250 sample points were drawn from 217 communities, whereby 25 communities were unable or unwilling to provide addresses. The missing municipalities were made up for with additional draws from the other municipalities. Overall, 192 municipalities (225 sample points) submitted addresses.

Personal addresses were drawn from the population registers by systematic random selection. The number of target subjects in the sample points was chosen in such a way that an initial sample of n = 8000 would be achievable. It was assumed that 50% of the selected individuals would not take part in the survey and 20% would not belong to the target population since they did not fall within the relevant age group, were not German-speaking, or their address was unknown. The uneven distribution of age cohorts in the population required a disproportionate approach, meaning that younger age cohorts were more likely to be selected given that they were not as strongly represented as were older age cohorts. Taking into consideration the disproportionate sample design and the anticipated sample-neutral dropouts per municipality, 900 addresses per sample point were selected. This equated to a gross sample of 30 689 individuals.

Fieldwork implementation

Fieldwork was carried out by the infas Institute for Applied Social Sciences (infas Institut für angewandte Sozialwissenschaften GmbH) between May and September 2021. In order to increase the response rate and minimize the selectivity of the sample, the survey used a mixture of methods comprising written postal surveys, online surveys, and telephone surveys. Depending on whether a telephone number (landline or mobile) could be found, the sample was divided into “telephone” and “written” study arms. All target persons received written correspondence comprising study information, a data privacy statement, an online access code, and an accompanying letter from the German Federal Ministry of Health.

Target persons in the telephone study arm were notified by a trained interviewer that they would be contacted. In the case of an unsuccessful attempt at telephone contact, a written questionnaire was sent in addition to a reminder letter. Individuals in the written study arm received the questionnaire with a postage-prepaid return envelope. If the target persons failed to respond, two reminders were sent at four-week intervals. At any time, respondents were able to switch between survey modes or request an additional written questionnaire. The online questionnaire could be answered on a variety of mobile devices, such as smartphones or tablets.

Instruments

The aim of the survey was to record the use of legal and illegal substances and related problems. In addition to information on the use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, and psychoactive medications, information was also gathered on physical and mental health status, chronic diseases, mental health disorders, and sociodemographics.

Both the online survey and the telephone survey were based on the written questionnaire. It was sometimes necessary in the online survey to optimize the layout and presentation of certain question batteries for mobile devices. In an additional module in the online survey, cannabis users were asked in-depth questions about their use of cannabis. The full questionnaire can be found at www.esa-survey.de/studie/instrumente.html.

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographic characteristics were recorded in line with the demographic standards of the German Federal Statistical Office (e10). Information on the following was gathered: sex and year of birth, migrant background (country of birth and citizenship) of the respondent and their parents, family situation (marital status, children, household size), education (schooling, vocational training), employment (employment status, occupational position) and net household income.

Health and health-related behavior

Physical and mental health were recorded by means of two five-point ratings (response categories 1 = “very good” to 5 = “very poor”). Chronic diseases were defined as diseases of at least 4 weeks‘ duration and requiring continuous monitoring and treatment. Applicable diseases could be specified from a list. This included the categories “cancer,” “osteoarthritis,” “arthritis,” “complaints in the neck region,” “knee complaints,” “headache (migraine),” “nervous system damage,” “muscle pain,” “neurological disease,” and “other.”

Screening for mental disorders was carried out using 11 questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, e11). These related to the preceding 12 months and included the presence of psychosomatic complaints, anxiety disorders (panic, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, fear of public places), depression, mania, and post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as psychiatric, psychological, or psychotherapeutic treatment or a finding of mental or psychosomatic illness.

Substance use

Both 30-day and 12-month prevalence rates were collected for all substances. The lifetime prevalence was recorded for the use of all substances except medications.

Use of tobacco and smoking alternatives

The survey included conventional tobacco products such as cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, and pipes, as well as smoking and tobacco alternatives such as e-cigarettes (these include e-cigars, e-waterpipes, and e-pipes), tobacco heaters, and waterpipes (hookahs). With the exception of waterpipes, the number of days of use in the preceding 30 days as well as the average amount used per day of use were recorded for these products alongside prevalence.

Alcohol use

The average amount of alcohol consumed was recorded using a quantity–frequency index separately for beer, wine/sparkling wine, spirits, and alcoholic mixed drinks. This was derived from data on the number of days on which the respective beverages were consumed and the number of units consumed on a typical day of consumption. To calculate the amount of pure alcohol in grams, the per-liter data for the beverages were used based on the beverage-specific alcohol contents and the number of units consumed. The beverage-specific alcohol contents (beer: 4.8 vol. %; wine/sparkling wine: 11.0 vol. %; spirits: 33.0 vol. %) respectively correspond to an amount of alcohol of 38.1 g, 87.3 g, and 262.0 g pure alcohol per liter (e12). For alcoholic mixed beverages, the average alcohol content of a glass (0.3–0.4 l) was assumed to be 0.04 l of spirits. An individual average daily amount was derived from the calculated pure alcohol in grams. Five categories were formed on the basis of recommended daily limits for low-risk alcohol consumption:

Episodic heavy drinking was recorded using an open-response format regarding the number of days on which five or more glasses of alcohol were consumed, irrespective of whether these were beer, wine/sparkling wine, spirits, or mixed alcoholic beverages (approximately 14 g of pure alcohol per glass, that is to say, at least 70 g of pure alcohol).

Use of (illegal) drugs