Abstract

A Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadhesin P1 gene with novel nucleotide sequence variation has been identified. Four clinical strains of M. pneumoniae were found to carry this type of P1 gene. This new P1 gene is similar to the known group II P1 genes but possesses novel sequence variation of approximately 300 bp in the RepMP2/3 region. The position of the new variable region is distant from the previously reported variable regions known to differ between group I and II P1 genes. Two sequences closely homologous to this new variable region were found within the repetitive sequences outside the P1 gene of the M. pneumoniae M129 genome. This suggests that the new P1 gene was generated by DNA recombination between repetitive sequences and the P1 gene locus. The finding of this new type of P1 gene supports the hypothesis that the repetitive sequences of the M. pneumoniae genome serve as a reservoir to generate antigenic variation of the cytadhesin P1 gene.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a causative agent of tracheobronchitis and primary atypical pneumonia in humans. Adherence to host respiratory epithelium (cytadherence) is a crucial step in M. pneumoniae infection and successful colonization (10, 23). Cytadherence is mediated by the specialized attachment organelle, a tip-like structure found in M. pneumoniae cells. A number of different mycoplasmal proteins take part in the formation of the attachment organelle and the cytadherence process (17, 18). A 170-kDa protein, P1, is densely clustered at the attachment organelle (6, 9) and is a major adhesion protein that directly binds to the receptor molecule of the host cells (23). A mutant strain of M. pneumoniae that lacks P1 protein fails to attach to host cells and is avirulent (1, 20). It has been reported that specific anti-P1 monoclonal antibodies can block cytadherence (15, 19). Through use of these monoclonal antibodies, the cytadherence-mediating domains of P1 protein have also been identified (5, 7). The P1 protein is a major M. pneumoniae immunogen and induces a strong immunological response in pneumonia patients (11, 21). However, only a small fraction of all of the anti-P1 antibodies present in patients’ sera can mediate cytadherence-inhibiting activity. This is because the cytadherence-mediating domains of the P1 protein are different from the immunodominant epitopes which trigger humoral responses (14, 16, 23).

The gene encoding the P1 protein forms an operon together with two open reading frames, ORF4 and ORF6 (13). It is known that only one copy of functional full-length P1 gene is to be found in the M. pneumoniae genome, although two-thirds of the P1 gene sequence exist as multiple copies (27, 34). Two repetitive regions exist in the P1 gene. One region is designated RepMP4 and is located at the 5′ end of the coding region, whereas the other, designated RepMP2/3, is located at the 3′ end (25). According to complete genome sequencing data for strain M129 of M. pneumoniae (8), a total of 8 copies, including the copies contained in the P1 gene, of the RepMP4 sequence and 10 copies of the RepMP2/3 sequence are dispersed throughout the genome. These RepMP sequences are closely related but not identical to one another, so it is conceivable that recombination between the P1 gene and RepMP sequences could generate a large sequence diversity of P1 genetic and antigenic variants. Herein may reside one of the mechanisms that enables M. pneumoniae to escape from host immune responses. Consistent with this hypothesis, sequence polymorphism was observed within P1 genes of clinical isolates of M. pneumoniae (4), and two types of P1 gene sequences have been reported (group I and group II) (28).

However, analyses of P1 genes from a number of clinical isolates of M. pneumoniae by Southern blotting (4, 29, 30), DNA fingerprinting (33), and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (26) techniques revealed only two types of P1 genes. Since there are only two types of P1 genes, the function of the RepMP sequence for generating P1 gene diversity is still obscure. Therefore, to clarify the role of the RepMP sequences, it is essential to find new types of P1 gene sequences and to analyze the mechanisms that generate P1 gene diversity.

In this study, we determined the precise RFLP patterns of P1 gene sequences from clinical isolates of M. pneumoniae and found certain strains which possess a new type of P1 gene sequence. The origin of this sequence variation is discussed below.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

M. pneumoniae strains and culture.

Two hundred eighteen clinical strains of M. pneumoniae were isolated from pneumonia patients in Japan during the period of 1979 to 1998. Of these clinical strains, 1 was isolated in Nagasaki Prefecture, 11 were isolated in Hokkaido Prefecture, and the others were collected in Kanagawa Prefecture. M. pneumoniae strains were cultured in PPLO medium (2.1% PPLO broth [Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.], 0.25% glucose, 0.002% phenol red, 10% horse serum [Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.], 200 units of penicillin G per ml) at 37°C. The strains were also cloned on PPLO agar plates (PPLO medium, 1.2% agar) to prevent mixed cultures before experiments were performed.

Isolation of genomic DNA from M. pneumoniae cells.

Genomic DNAs from M. pneumoniae strains were isolated as follows: M. pneumoniae cells were collected from 1 ml of culture medium by centrifugation. The pellets were suspended in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM sodium citrate, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mg of proteinase K per ml, 20 μg of RNase A per ml, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and incubated at 55°C for 30 min. Lysates were kept at 37°C overnight and then treated twice with 0.5 ml of phenol-chloroform. Genomic DNAs were precipitated with 1 ml of isopropanol and then washed with 70% ethanol and dried.

PCR-RFLP analysis of M. pneumoniae strains.

The PCR-RFLP typing method was based on a previous report (26). PCR primers ADH1 (CTGCCTTGTCCAAGTCCACT) and ADH2 (AACCTTGTCGGGAAGAGCTG) were used to amplify P1 gene DNA containing RepMP4 sequences. Primers ADH3 (CGAGTTTGCTGCTAACGAGT) and ADH4 (CTTGACTGATACCTGTGCGG) were used to amplify the RepMP2/3 region (see Fig. 1A). Amplified DNA fragments were digested with the HaeIII restriction enzyme and analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

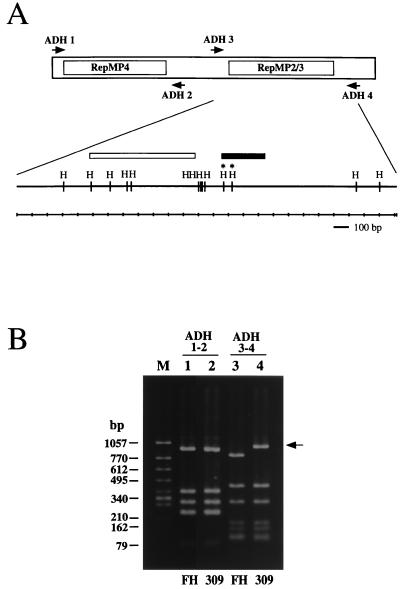

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of the group II P1 gene. The regions of two repetitive sequence groups (RepMP4 and RepMP2/3) are indicated. Arrows indicate the binding sites of the PCR primers employed for RFLP analysis. The inside region between the ADH3 and ADH4 primer sites is shown magnified below, and the positions of HaeIII restriction sites (H) are indicated. Two HaeIII sites which were missing in the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene are marked with asterisks. The solid bar indicates the region of variable sequence found in the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene (see Fig. 2 and text). The open bar indicates the variable region between the group I and group II P1 genes. (B) PCR-RFLP analysis of M. pneumoniae P1 genes. P1 gene DNA fragments amplified by PCR were digested with the HaeIII restriction enzyme and analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR primers used for the analysis are shown at the top. Lanes: M, DNA size marker (φX174 HincII digest); 1 and 3, M. pneumoniae FH; 2 and 4, M. pneumoniae 309. The difference in the RFLP pattern of M. pneumoniae 309 is indicated by an arrow.

DNA sequencing analysis.

The RepMP2/3 region of the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotide primers ADH3-EC (AAGGAATTCGAGTTTGCTGCTAACGAGT) and ADH4-PS (GTTCTGCAGCTTGACTGATACCTGTGCGG). ADH3-EC and ADH4-PS are ADH 3 and ADH4 primers with a restriction enzyme site (EcoRI or PstI) (underlined) at the 5′ end. The RepMP2/3-5 region of strain 309 was cloned by PCR with the oligonucleotide primers 5F (TAAGAATTCCAATAACACCTTTAAAG) and 5R (AGCTGCAGTTAGCAACGCTGCAAAGGCG). The RepMP2/3-6 region of strain 309 was also cloned by PCR with, primers 6F (AAGGAATTCTGACCCTAGTGTGGCGAAAA) and 6R (TTCCTGCAGGGAGAGATCCACGCCAGATT). These primers also contain either an EcoRI or a PstI restriction site (underlined). Amplified fragments were digested with EcoRI and PstI and ligated into the EcoRI and PstI sites of the Bluescript II SK+ plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Sequencing of cloned PCR fragments was performed by a primer walking strategy with the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit and the DNA sequencer ABI PRISM 310 (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper will appear in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AB024618.

RESULTS

Identification of new variable sequences in functional P1 genes from clinical strains of M. pneumoniae.

To seek new nucleotide sequences in the functional P1 gene, we analyzed 218 clinical strains of M. pneumoniae by a PCR-RFLP typing method (26). In this approach, oligonucleotide PCR primers ADH1, ADH2, ADH3, and ADH4, which are derived from single-copy regions flanking the RepMP regions of the P1 gene (Fig. 1A), were employed. This means that only functional P1 gene sequences were able to be amplified. These amplified P1 gene fragments were then typed with the restriction enzyme HaeIII to generate characteristic RFLP patterns.

In the analysis of the RepMP2/3 region with primers ADH3 and ADH4, we found four strains that show RFLP patterns that are different from those of M. pneumoniae M129 (group I) and FH (group II) strains. As shown in Fig. 1B, the RFLP pattern of one of these, strain 309, was similar to that of strain FH. However, the size of one restriction fragment was about 150 bp larger than that of the FH strain, suggesting a loss of HaeIII sites (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 4). The RFLP patterns of the other three strains (165, 170, and 199) were identical to the pattern of strain 309 (data not shown). On the other hand, analysis of the RepMP4 region with primers ADH1 and ADH2 revealed that the RFLP patterns of all tested strains were identical to the RFLP patterns of either M. pneumoniae M129 or strain FH. Therefore, all tested strains were classified into group I or II by this method (data not shown). In this analysis of the RepMP4 region, M. pneumoniae 309 was classified into group II (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2), as were the other three strains (data not shown).

These results suggested that at least four M. pneumoniae strains (165, 170, 199, and 309) have sequence changes in the RepMP2/3 region of the functional P1 gene.

DNA sequence analysis of the RepMP2/3 region of the functional P1 gene from M. pneumoniae 309.

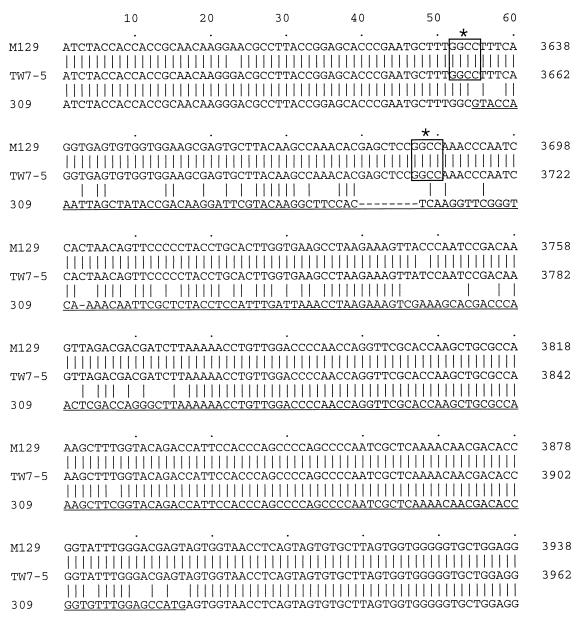

The nucleotide sequence of the RepMP2/3 region from the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene was then analyzed. The gene was cloned by PCR and ligated into the Bluescript II SK+ plasmid. To avoid the confounding factor of mutations generated in the course of the PCRs, three independent plasmid clones were sequenced. Their sequences were compared to P1 gene sequences previously reported for the group I strain M129 (13) and for the group II strain TW7-5 (28) of M. pneumoniae. Although we used M. pneumoniae FH in the PCR-RFLP analysis as a representative group II strain, we utilized the P1 gene sequence of strain TW7-5 here for comparison. This is because the complete nucleotide sequence of the M. pneumoniae FH P1 gene has not been reported. However, the theoretical RFLP patterns of the M. pneumoniae TW7-5 P1 gene indicate that the P1 genes of strains FH and TW7-5 are well conserved. It was apparent that the major difference between the P1 gene sequences was between nucleotides 3633 and 3894 of the group I P1 gene. This corresponds to positions 3657 through 3918 of the group II P1 gene (Fig. 2). In this region, the nucleotide sequence of the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene was 9 bp shorter than in either the M129 or TW7-5 strain of M. pneumoniae. Loss of two HaeIII sites was also found in the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene. This was the reason for the generation of an HaeIII restriction fragment from strain 309 which was 155 bp larger in the PCR-RFLP analysis (Fig. 1B). The position of this new variable region of M. pneumoniae 309 is distant from the previously reported variable regions known to differ between group I and II P1 genes (Fig. 1A). This therefore implies that the variation found in the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene represents a genuine new variable sequence not reported previously in the group I and group II P1 genes. We also sequenced the same region from strains 165, 170, and 199 of M. pneumoniae and found that these three strains possess sequences identical to those of strain 309 (data not shown). As expected from the RFLP analysis, the other region of the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene sequence was almost identical to that of strain TW7-5. However, the following three point mutations were identified: 2539 A→G, 2872 G→A, and 2886 A→T. These point mutations affect neither the HaeIII restriction sites nor the deduced amino acid sequences.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the P1 gene nucleotide sequences between strains M129 (group I), TW7-5 (group II), and 309. Partial P1 gene sequences that contain newly identified variable regions are shown. The positions of two HaeIII recognition sites of the M. pneumoniae M129 and TW7-5 P1 genes that were missing in the 309 P1 gene are marked with asterisks and boxed. The stretch of variable region is underlined. Nucleotides were counted from the start codon (AUG) of the M129 and TW7-5 P1 genes (12, 28, 31).

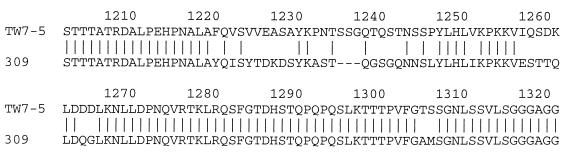

The deduced amino acid sequence of the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene was compared with that of the M. pneumoniae TW7-5 P1 gene. As shown in Fig. 3, differences between the two sequences were found in amino acid positions 1220 to 1306 (a region which corresponds to amino acids 1212 through 1298 of the M. pneumoniae M129 P1 protein). In this region, the sequence of the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 protein was 3 amino acids shorter than that of the M. pneumoniae TW7-5 P1 protein.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of deduced amino acid sequences of P1 proteins from strains 309 and TW7-5. The region shown in this figure corresponds to the region of nucleotide sequence shown in Fig. 2.

In the area we sequenced, no nonsense mutations were observed in the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene. To validate this sequencing result, Western blot analysis with mouse anti-P1 antiserum was carried out with whole-cell lysates from M. pneumoniae 309. The results were consistent with those of the sequence analysis, in that production of a full-size 170-kDa P1 protein was observed in the M. pneumoniae 309 cells (data not shown).

Identification of RepMP sequences involved in generation of P1 gene sequences of M. pneumoniae 309.

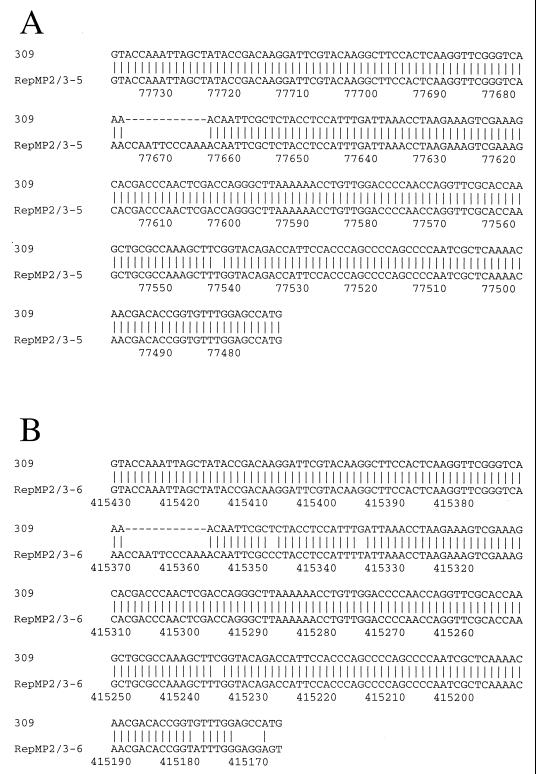

To confirm that the sequence variation of the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene originated from recombination between a functional P1 gene and RepMP2/3 copies outside of the P1 gene locus, we searched the entire genomic sequence of M. pneumoniae M129. Two RepMP2/3 copies that contain sequences highly homologous to the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 variation were found as a result. These homologous sequences are located at nucleotide positions 77474 to 77738 and 415175 to 415432 of the M. pneumoniae M129 genome sequence (GenBank accession no. U00089) (8). Figure 4 shows a comparison of the variable region of the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene with these homologous sequences found in the M. pneumoniae M129 genome. In comparison with the two homologous sequences, a 12-bp deletion was observed in the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene. Except for this 12-bp deletion, the homologous sequence that exists in nucleotides 77474 through 77738 of M. pneumoniae M129 showed only one nucleotide mismatch with the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene sequence (nucleotide 77543), as illustrated in Fig. 4A. This sequence is henceforth designated RepMP2/3-5. On the other hand, the RepMP2/3 sequence that exists within nucleotides 415175 through 415432 of the M. pneumoniae M129 genome showed four single mismatches, and a region upstream from nucleotide 415174 did not match the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 sequence. This is illustrated in Fig. 4B. This sequence is henceforth designated RepMP2/3-6.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the variable region of the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene and the RepMP2/3 sequences of M. pneumoniae M129. Numbering of nucleotides was derived from the GenBank file of the complete genome sequence (accession no. U00089) of M. pneumoniae M129 (8). RepMP2/3 sequences are shown in an inverted direction.

The existence of these two homologous sequences in RepMP2/3 copies outside the P1 locus indicated that the sequence variation found in the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene could have been generated by homologous recombination between the RepMP2/3 copies and the P1 gene. RepMP2/3-5 is more homologous to the sequence variation of the 309 P1 gene than is RepMP2/3-6. Thus, it is probable that RepMP2/3-5 is the sequence most likely to be involved in the recombination event. The 12-bp deletion and the point mutation found in the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene might be explained by their having occurred subsequent to recombination.

Sequence analysis of the RepMP2/3-5 and RepMP2/3-6 regions from M. pneumoniae 309.

In homologous recombination events, DNA sequence exchange by crossover is frequently observed between recombinant DNA strands. Thus, the generation of new P1 gene sequences by homologous recombination may cause shuffling of the RepMP sequences in the M. pneumoniae genome. If the RepMP2/3-5 or RepMP2/3-6 sequence was involved in the homologous recombination that generated the new P1 gene, it is possible that some sequence change would have been made in the RepMP2/3-5 or RepMP2/3-6 region of M. pneumoniae 309 relative to that of M129. Therefore, to investigate this we analyzed the nucleotide sequences of the RepMP2/3-5 and RepMP2/3-6 regions of M. pneumoniae 309. Oligonucleotide PCR primers were designed based on the nonrepetitive sequences flanking the RepMP2/3-5 and RepMP2/3-6 regions of M. pneumoniae M129 and were used to amplify the genomic DNA of strain 309. DNA fragments with the expected sizes, namely, a 2.2-kb fragment containing the RepMP2/3-5 region and a 1.75-kb fragment containing the RepMP2/3-6 region, were specifically amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of M. pneumoniae 309. These fragments were then cloned into Bluescript II SK+ plasmids. Unexpectedly, as a result of this sequencing, we established that the nucleotide sequences of the RepMP2/3-5 and RepMP2/3-6 regions from M. pneumoniae 309 are identical to those from M. pneumoniae M129.

DISCUSSION

It has been reported that the gene coding for the cytadhesin protein P1 of M. pneumoniae contains sequences that exist as multiple copies in the genome. It was suggested that recombination between the P1 gene and repetitive sequences outside the P1 gene could generate a large number of antigenic variations that enable M. pneumoniae to escape from host immune responses (2, 27, 30). A similar feature has also been reported for P1-like cytadhesin genes of Mycoplasma genitalium (3) and Mycoplasma pirum (32). In the case of M. genitalium, the function of repetitive sequences for generating antigenic variants is relatively clear because the polymorphism of the P1-like MgPa gene is observed frequently in clinical isolates. Analysis of the polymorphic sequences of the MgPa genes revealed recombination events between the MgPa gene and such repetitive sequences (22). However, in M. pneumoniae, only two types of P1 gene polymorphism have been identified (groups I and II). There is no direct evidence that clearly explains the role of repetitive sequences in the generation of antigenic variants.

In this study, we precisely analyzed the P1 genes from clinical isolates of M. pneumoniae by using PCR-RFLP methodology and found a new type of P1 gene. Four clinical strains of M. pneumoniae, designated 165, 170, 199, and 309, were found to possess the new type of P1 gene. The novel P1 genes from these four strains were well conserved, although they had been independently isolated from different locations and at different times: strains 165 and 170 were isolated in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1991, strain 199 was also isolated in Kanagawa but in 1993, and strain 309 was isolated in Hokkaido Prefecture in 1998. The different isolation times and locations indicate that the new type of P1 gene sequence is maintained stably in M. pneumoniae cells through generations.

The nucleotide sequence of the new P1 gene is similar to that of the group II P1 gene, but it possesses a sequence variation of approximately 300 bp at the 3′ end of the RepMP2/3 region. The location of this variable region does not overlap the previously reported variable region between group I and II P1 genes (Fig. 1A).

Two sequences closely homologous to the variable region of the new P1 gene were found in the M. pneumoniae M129 genome. These two sequences (RepMP2/3-5 and RepMP2/3-6) are part of the RepMP2/3 copies outside the P1 operon. Although when compared with RepMp2/3-5 and RepMP2/3-6 sequences a 12-bp deletion was found in the new P1 gene sequence, these homologous RepMP2/3 copies seem to be the most probable origins of the sequence variation of the M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene. The M. pneumoniae 309 P1 gene might be created by a homologous recombination event between these RepMP sequences and the P1 gene locus. The gene coding for the RecA-like protein that is required for this homologous recombination has already been reported in the M. pneumoniae genome (8). To investigate this homologous recombination event more clearly, we attempted to analyze the RepMP2/3-5 and RepMP2/-6 regions of M. pneumoniae 309, expecting to find the sequence change made by the recombination. However, this revealed that the nucleotide sequences of the RepMP2/3-5 and RepMP2/-6 regions from M. pneumoniae 309 were identical to those from M. pneumoniae M129. In this attempt, we did not obtain simple evidence for homologous recombination between the P1 gene locus and the RepMp2/3-5 or RepMP2/3-6 sequence of M. pneumoniae 309. One possible explanation of this result is the involvement of gene conversion events. It was reported that the ORF6 gene of the P1 operon also contains a repetitive region (RepMP5) (34) and manifests sequence polymorphism between strains M129 and FH of M. pneumoniae. Ruland et al. analyzed these polymorphic sequences by comparing them with RepMP5 sequences and concluded that the polymorphism of the ORF6 gene might be generated by a gene conversion event (24). This observation on the ORF6 gene is consistent with our findings on the P1 genes and RepMP2/3 sequences of M. pneumoniae M129 and 309 (i.e., unidirectional sequence exchange). Thus, at this point, a gene conversion event is thought to be the most probable mechanism for DNA recombination between the P1 gene locus and the RepMP2/3 copies. This gene conversion would occur through the formation of heteroduplex DNA, which is mediated by RecA-like enzymes and Ruv-like proteins. The genes coding for the RuvA- and RuvB-like proteins have been identified in the M. pneumoniae M129 genome (8).

However, in our sequence comparison analysis, we have no data on the precise number and organization of RepMP copies in the M. pneumoniae 309 genome. M. pneumoniae M129 was identified as a group I P1 gene strain. On the other hand, M. pneumoniae 309 is closely related to group II strains. It is possible that the numbers and organizations of RepMP sequences of both strains may be altered evolutionarily. Therefore, the possibility still remains that other, thus-far-undiscovered RepMP2/3 copies exist in the M. pneumoniae 309 genome and may be involved in homologous recombination with reciprocal sequence exchange. Further investigation will clarify these DNA recombination mechanisms.

The variable region of the predicted amino acid sequence of the new P1 protein corresponds to amino acid positions 1212 to 1298 of the M. pneumoniae M129 P1 protein. This region is relatively close to previously reported epitopes recognized by cytadherence-inhibiting anti-P1 monoclonal antibodies (5, 7). Although the biological effects of such amino acid sequence changes on the function of P1 protein have not yet been examined, it may be that these alterations modulate the interaction of M. pneumoniae with the host immune system.

In this study, we have identified a new type of P1 gene and proposed a possible mechanism for its generation. The existence of a novel type of P1 gene strongly supports the idea that RepMP sequences serve as a reservoir for generation of antigenic variation of P1 cytadhesin genes in M. pneumoniae. Isolation of additional examples of these types of P1 genes and analysis of the organizations of their RepMP sequences will provide a more detailed understanding of the mechanism involved in generation of the P1 gene variation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baseman J B, Cole R M, Krause D C, Leith D K. Molecular basis for cytadsorption of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:1514–1522. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.3.1514-1522.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baseman J B, Tully J G. Mycoplasmas: sophisticated, reemerging, and burdened by their notoriety. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:21–32. doi: 10.3201/eid0301.970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dallo S F, Baseman J B. Adhesin gene of Mycoplasma genitalium exists as multiple copies. Microb Pathog. 1991;10:475–480. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90113-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dallo S F, Horton J R, Su C J, Baseman J B. Restriction fragment length polymorphism in the cytadhesin P1 gene of human clinical isolates of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2017–2020. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.2017-2020.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dallo S F, Su C J, Horton J R, Baseman J B. Identification of P1 gene domain containing epitope(s) mediating Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytoadherence. J Exp Med. 1988;167:718–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldner J, Gobel U, Bredt W. Mycoplasma pneumoniae adhesin localized to tip structure by monoclonal antibody. Nature. 1982;298:765–767. doi: 10.1038/298765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GersteneckeR B, Jacobs E. Topological mapping of the P1-adhesin of Mycoplasma pneumoniae with adherence-inhibiting monoclonal antibodies. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:471–476. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-3-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li B C, Herrmann R. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4420–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu P C, Cole R M, Huang Y S, Graham J A, Gardner D E, Collier A M, Clyde W A., Jr Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: role of a surface protein in the attachment organelle. Science. 1982;216:313–315. doi: 10.1126/science.6801766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu P C, Collier A M, Baseman J B. Surface parasitism by Mycoplasma pneumoniae of respiratory epithelium. J Exp Med. 1977;145:1328–1343. doi: 10.1084/jem.145.5.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu P C, Huang C H, Collier A M, Clyde W A., Jr Demonstration of antibodies to Mycoplasma pneumoniae attachment protein in human sera and respiratory secretions. Infect Immun. 1983;41:437–439. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.1.437-439.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inamine J M, Denny T P, Loechel S, Schaper U, Huang C H, Bott K F, Hu P C. Nucleotide sequence of the P1 attachment-protein gene of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Gene. 1988;64:217–229. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inamine J M, Loechel S, Hu P C. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the P1 operon of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Gene. 1988;73:175–183. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs E. Mycoplasma pneumoniae virulence factors and the immune response. Rev Med Microbiol. 1991;2:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs E, Gerstenecker B, Mader B, Huang C H, Hu P C, Halter R, Bredt W. Binding sites of attachment-inhibiting monoclonal antibodies and antibodies from patients on peptide fragments of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae adhesin. Infect Immun. 1989;57:685–688. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.685-688.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs E, Pilatschek A, Gerstenecker B, Oberle K, Bredt W. Immunodominant epitopes of the adhesin of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1194–1197. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1194-1197.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krause D C. Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadherence: organization and assembly of the attachment organelle. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:15–18. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krause D C. Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadherence: unravelling the tie that binds. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause D C, Baseman J B. Inhibition of Mycoplasma pneumoniae hemadsorption and adherence to respiratory epithelium by antibodies to a membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1983;39:1180–1186. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1180-1186.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krause D C, Leith D K, Baseman J B. Reacquisition of specific proteins confers virulence in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1983;39:830–836. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.2.830-836.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leith D K, Trevino L B, Tully J G, Senterfit L B, Baseman J B. Host discrimination of Mycoplasma pneumoniae proteinaceous immunogens. J Exp Med. 1983;157:502–514. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.2.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson S N, Bailey C C, Jensen J S, Borre M B, King E S, Bott K F, Hutchison C A., III Characterization of repetitive DNA in the Mycoplasma genitalium genome: possible role in the generation of antigenic variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11829–11833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Razin S, Jacobs E. Mycoplasma adhesion. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:407–422. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-3-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruland K, Himmelreich R, Herrmann R. Sequence divergence in the ORF6 gene of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5202–5209. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5202-5209.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruland K, Wenzel R, Herrmann R. Analysis of three different repeated DNA elements present in the P1 operon of Mycoplasma pneumoniae: size, number and distribution on the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6311–6317. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sasaki T, Kenri T, Okazaki N, Iseki M, Yamashita R, Shintani M, Sasaki Y, Yayoshi M. Epidemiological study of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in Japan based on PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the P1 cytadhesin gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:447–449. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.447-449.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su C J, Chavoya A, Baseman J B. Regions of Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadhesin P1 structural gene exist as multiple copies. Infect Immun. 1988;56:3157–3161. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3157-3161.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su C J, Chavoya A, Dallo S F, Baseman J B. Sequence divergency of the cytadhesin gene of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2669–2674. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2669-2674.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su C J, Dallo S F, Baseman J B. Molecular distinctions among clinical isolates of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1538–1540. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.7.1538-1540.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su C J, Dallo S F, Chavoya A, Baseman J B. Possible origin of sequence divergence in the P1 cytadhesin gene of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1993;61:816–822. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.816-822.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su C J, Tryon V V, Baseman J B. Cloning and sequence analysis of cytadhesin P1 gene from Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3023–3029. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3023-3029.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tham T N, Ferris S, Bahraoui E, Canarelli S, Montagnier L, Blanchard A. Molecular characterization of the P1-like adhesin gene from Mycoplasma pirum. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:781–788. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.781-788.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ursi D, Ieven M, van Bever H, Quint W, Niesters H G, Goossens H. Typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae by PCR-mediated DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2873–2875. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2873-2875.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenzel R, Herrmann R. Repetitive DNA sequences in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:8337–8350. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.17.8337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]